Abstract

The synthesis, structural, and spectral characterization as well as a theoretical study of a family of alkaline-earth-metal acetylides provides insights into synthetic access and the structural and bonding characteristics of this group of highly reactive compounds. Based on our earlier communication that reported unusual geometry for a family of triphenylsilyl-substituted alkaline-earth-metal acetylides, we herein present our studies on an expanded family of target derivatives, providing experimental and theoretical data to offer new insights into the intensively debated theme of structural chemistry in heavy alkaline-earth-metal chemistry.

Keywords: acetylides, alkaline earth metals, secondary interactions, structure-determining factors, structure elucidation

Introduction

One of the intriguing topics in the molecular chemistry of the alkaline earth metals has been a pattern of unusual structural variations, the most prominent examples consisting of fluorides and cyclopentadienides in which gas-phase electron diffraction studies revealed considerable ligand-metal-ligand bending upon descending Group 2.[1,2] Analogous trends were observed in the solid state in which crystallographic studies on [MCp*2] (M = Mg, Ca, Ba; Cp* = C5Me5) revealed linear geometry for the magnesium derivative, whereas bent geometry (148°) was observed for the barium analogue [BaCp*2].[2,3] Further studies have confirmed these trends for an extended group of ligands, indicating that the capacity for bending is dependent on ligand bulk, because very bulky cyclopentadienides such as [M-C5iPr5)2] exhibit linear geometry.[4] Experimental data were confirmed by theoretical studies in which the structures of alkaline-earth-metal halides, hydrides, and other ligands such as -CH3, -OH, and -BH2 were predicted to deviate from ideal, linear geometry.[5–12]

Extensive work to rationalize the bending resulted in the development of 1) a simple electrostatic model, based on the idea that the negatively charged ligands polarize the electron cloud of the metal center, and thus induce a dipole on the metal that may be reduced by bending. Bending is most prominent for the heavier metals because their electron cloud is most easily distorted.[1,2,5] Other rationales include 2) the involvement of d orbitals, which is made possible by the decreasing orbital separation between (n−1)d and ns orbitals for the heavier elements as a result of relativistic effects. The d orbital involvement would result in a (n−1)d ns rehybridization involving bent geometry.[1,2,6,7] Alternatively, 3) van der Waals attractions between the ligands have been suggested based on force-field calculations. Bent geometry facilitates these (weak) interactions owing to closer ligand contacts.[1–3] A more recent contribution focuses on the development of a model to predict linear or bent geometry. In this model, covalency, polarization and hybridization contribute to a parameter called chemical softness. If the difference in softness between metal and ligand exceeds 0.29 eV, bending will be observed.[6] Alternatively, a pseudo-Jahn–Teller effect may be used to explain the bending.[8] By putting these models in perspective, MO calculations have shown the distortion from linear geometry to be facile, with a linearization energy for the metallocenes from 4–12 kJmol−1.[2,9–12]

Experimental and theoretical studies on halides and related compounds have demonstrated that bent geometry is not limited to metallocenes, and more recently, the organometallic two-coordinate [Ca{C(SiMe3)3}2] showed an unexpected C-Ca-C angle of 149.7(6)°.[13] However, the absence of the corresponding strontium and barium compounds does not allow for the evaluation of metal influence.

A family of alkaline-earth-metal acetylides, [M([18]crown-6)(C≡ CSiPh3)2] (M = Ca (1a), Sr (2a), and Ba (3a)), provided a more extensive insight into the influence of the metal center.[14] Upon descending Group 2, an increasing degree of deviation from ideal geometry involving the trans-C-M-C, as well as the M-C≡C angle was observed. Although the C-M-C bent angle was modest (162.7(3)° for barium), a significant distortion from ideal linear geometry was observed for the M-C≡C angle with values as low as 126.6(3)° for the barium derivative. These compounds also represented the first examples of strontium and barium organometallics displaying σ bonding. We herein provide an extension to these studies by introducing two additional ligands, HC≡C-4-t BuC6H4 and HC≡CtBu. These have different electronic and steric requirements than the triphenylsilyl acetylide ligand, and thus allow the evaluation of these variables on the structural chemistry. Our experimental work is complimented by theoretical studies to rationalize the origin of the geometrical pattern further.

We herein report THF- and [18]crown-6-stabilized compounds, which result in the families [M(CCR)2(donor)n] (R = 4-tBuC6H4, donor = [18]crown-6, M = Ca (1b), Sr (2b), Ba (3b); R=tBu, donor=thf, M=Ca (1c); donor= [18]crown-6, M=Sr (2c), M=Ba (3c)).[15,16] These are compared with 1a, 2a, and 3a,[14–16] as well as a series of magnesium derivatives.[17] Aside from answering important questions about the influence of metal, ligand, and donor on compound geometry, the target compounds provide an extension to the rapidly growing family of heavy alkaline earth organometallics.[18]

Results and Discussion

One of the most facile methodologies for the synthesis of organoalkaline-earth-metal compounds is transamination, which utilizes the readily available amides [M{N(SiMe3)2}2-(thf)2] (M = Ca, Sr, Ba).[19–21] By using this methodology, the acetylides 1a–c, 2a–c, and 3a–c were synthesized (Scheme 1).[14–16]

Scheme 1.

Transamination reactions to afford the acetylides 1a–c, 2a–c, and 3a–c.

Alternatively, the highly reactive dibenzyl reagents [M-(CH2Ph)2(thf)n] (M = Ca, Sr, Ba) have been shown to metallate organic substrates under liberation of toluene.[15,16,22,23] This route allowed the preparation of 1b–3b and 1c–3c in excellent yields and purity (Scheme 2).[16]

Scheme 2.

The use of highly reactive dibenzyl reagents in the synthesis of 1b–3b and 1c–3c.

Both methodologies are based on the pKa difference between the acidic alkyne (pKa ~ 29) and the liberated HN-(SiMe3)2 (pKa = 30) or toluene (pKa = 41). The larger difference in pKa for the latter allows a swifter reaction. However, the reaction conditions are more restricted because the benzyl reagents display low solubility in hydrocarbon solvents, and thus require the use of a polar solvent such as THF to achieve homogeneous reaction conditions. The highly reactive benzyl reagents cleave THF at ambient conditions under enolate formation, and so low-temperature reaction conditions (−40°C) are required.[18] Despite these limitations, toluene elimination is a powerful methodology for the preparation of a wide array of alkaline-earth organometallics, especially for less acidic ligand systems.

All target compounds are highly reactive, and great care is required in their preparation and isolation. Characterization of the target compounds is difficult because the isolated compounds cannot be stored in a freshly regenerated glove box for more than a few hours. Several of the compounds decompose upon removal of the mother liquor, and therefore, some of the crystals were stored in a small amount of the mother liquor. As a result, we were unable to obtain elemental analyses, and the NMR spectra always contained signals from the solvent.

The significant impact of ligand bulk on the thermal stability of the compounds is demonstrated by our inability to prepare the closely related trimethylsilyl-substituted acetylides. Multiple attempts resulted in decomposition, which was recognizable by a color change from colorless to yellow upon warming the samples above −40°C.[24] Likewise, kinetic stabilization, which was achieved through the presence of multidentate donors, appears to be critical because replacement of [18]crown-6 by multidentate ethers such as 1,2-dimethoxyethane and/or di- or triglyme resulted in decomposition upon warming the reaction mixture above −78°C.[24]

Several important trends can be noted by analyzing the reactivity of the family of target compounds. Unsurprisingly, reactivity increases as the ligand size decreases, making species 1a–3a the most robust, whereas 1b–3b and 1c–3c are significantly more reactive. Even so, compounds 1a–3a are highly sensitive towards hydrolysis, and exposure to minute quantities of water results in immediate hydrolysis and formation of siloxide, as represented by the spectroscopically and structurally characterized [M([18]crown-6){OSi-(C6H5)3}2] (M = Ca or Sr, Scheme 3).[14,25]

Scheme 3.

The synthesis of [M([18]crown-6){OSiC6H5)3}2] (M = Ca or Sr).

The 1H NMR spectral analysis revealed the presence of the ligands and crown ether in the expected stoichiometry, however, it proved difficult to detect the acetylenic carbon atoms in the 13C NMR spectra despite the increase of relaxation times combined with extended run times. Because the 13C NMR shift of Cipso provides information on the ion association of the compound in solution (recently shown for a phenylacetylide anion in conjunction with a very bulky phosphazene base)[26] we are unable to speculate about the solution structure of the target compounds.

IR spectroscopy provides a glimpse at the C≡C bond characteristics, with stretching frequencies for the acetylides ranging from 2035–1955 cm−1 (Table 1). Noticeably, a decrease in the IR frequencies for all three ligand systems upon descending Group 2 is observed, namely, from 1980–1955 cm−1 for 1a–3a, 2032–1997 cm−1 for 1b–3b and 2035–1998 cm−1 for 1c–3c. Also of note, the values for the metal complexes are consistently lower than for the corresponding free alkynes (2034, 2109, and 2108 cm−1). Furthermore, the C≡C stretching frequencies for the silyl-substituted ligands in 1a, 2a, and 3a are lower than those for the carbon-based ligands, 4-tBuC6H4 (in 1b, 2b, and 3b) and tBu (in 1c, 2c, and 3c), which is likely to be a consequence of the electronic influence of the more electropositive silyl substituent.

Table 1.

IR spectroscopic data of the alkaline-earth-metal acetylides.[a]

| HC≡ CR |

ν̄(C≡C) [cm−1] M(C≡CR)n |

Δν̄ [cm−1] | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R=Si(C6H5)3 | 2034–2035 | [Ca{(iPr)4C5H}(CCR)]p | 1985[b] | 50 | [27] |

| 1at | 1980[c] | 54 | [14] | ||

| 2at | 1969[c] | 65 | [14] | ||

| 3at | 1955[c] | 79 | [14]] | ||

| R=4-tBuC6H4 | 2109 | 1bt | 2032[c] | 77 | [16] |

| 2bt | 2004[c] | 105 | [16] | ||

| 3bt | 1997[c] | 112 | [16] | ||

| R=tBu | 2106–2108 | [Ca{(NDippCMe)2CH}(CCR)]2br | 2029[c] | 79 | [28] |

| 1c | 2035[c] | 73 | [16] | ||

| 2c | 2002[c] | 106 | [16] | ||

| 3ct | 1998[c] | 110 | [16] | ||

| R=C6H5 | 2110–2111 | [Ca{(iPr)4C5H}(CCR)(thf)]br | 2043[b] | 67 | [27] |

| [Ca{(NDippCMe)2CH}(CCR)]2br | 2040[c] | 71 | [28] | ||

| [Ca(CCR)] | 2036[d] | 74–75 | [29] | ||

| [Sr(CCR)] | 2023[d] | 87–88 | [29] | ||

| [Ba(CCR)] | 2017[d] | 93–94 | [29] | ||

| R=SiMe3 | 2037 | [Ca{(iPr)4C5H}(CCR)] | 1991[b] | 46 | [27] |

| R=nBu | 2118 | [Ca{(NDippCMe)2CH}(CCR)]2br | 2048[c] | 70 | [28] |

| R=C6H4Me | 2110 | [Ca{(NDippCMe)2CH}(CCR)]2br | 2034[c] | 76 | [28] |

| R=ferrocenyl | 2105 | [Ca{(iPr)4C5H}(CCR)] | 2042[b] | 63 | [27] |

| R=Si(iPr3) | 2032 | [Ca{(iPr)4C5H}(CCR)] | 1968[b] | 64 | [27] |

Dipp=2,6-iPr2(C6H3); p = polymeric, br = bridging, t = terminal.

IR spectra were obtained from KBr pellets.

IR spectra were obtained from KBr plates/disks.

IR spectra were obtained from Nujol mulls.

The decrease in the acetylinic stretching frequency may be explained by the increased atomic weight of the metal center, which makes the stretching frequency largely independent of the C≡C bond order. In this case, the C≡C bond length, as determined by X-ray crystallography, should not lengthen for the heavier metals.

A further rationale for the change in C≡C stretching frequency focuses on a possible side-on overlap between the ligand π system and the metal center, as made possible by the significant Cipso bent angle with values as low as 119° for 3b, and 127° for 3a.[14] IR spectroscopy would provide significant insight into this bonding mode, because the side-on overlap would result in a reduced C≡C bond order, an observation that could be verified further by X-ray crystallography.

Careful analysis of crystallographic data (vide supra) does not indicate a correlation between the M-C≡C bent angle and C≡C bond length (see Table 3), suggesting that side-on overlap is weak at best.

Table 3.

Selected bond lengths and angles of compounds 1a–3a, 1b–3b, 3c, and related literature data.[a]

| HC≡CR | M(C≡ CR)n | CN | M–C [Å] | C-M-C [°] | M-C≡C [°] | C≡C [Å] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R=SiPh3 | [MgR2(thf)4] | 6 | 2.237(5)t | 180.0 | 173.2(8) | 1.226(2) | [17] |

| R=SiPh3 | [MgR2(tmeda)2] | 6 | 2.214(4)t | 180.0 | 173.9(4) | 1.221(5) | [17] |

| R=SiPh3 | 1a | 8 | 2.523(7)t | 168.7(2) | 162.4(5) | 1.229(8) | [14] |

| 2.558(7)t | 164.0(5) | 1.234(8) | |||||

| R=SiPh3 | 2a | 8 | 2.692(4)t | 166.0(1) | 158.9(9) | 1.201(5) | [14] |

| 2.723(4)t | 159.7(3) | ||||||

| R=SiPh3 | 3a | 8 | 2.785(2)t | 162.7(3) | 126.6(3) | 1.223(4) | [14] |

| 2.789(2)t | 141.3(3) | 1.236(5) | |||||

| R=4-t BuC6H4 | [MgR2([15]crown-5)] | 7 | 2.222(4)avt | 174.1(7) | 172.6(9) | 1.220(1) | [17] |

| 164.4(1) | |||||||

| R=4-t BuC6H4 | 1b[b] | 8 | molecule 1 | [16] | |||

| 2.512(1)t | 173.1(7) | 164.2(3) | 1.219(2) | ||||

| 2.512(1)t | 169.3(3) | 167.9(3) | 1.219(2) | ||||

| molecule 2 | |||||||

| 2.478(3)t | 154.4(7) | 160.2(3) | 1.219(2) | ||||

| 2.534(3)t | 161.8(7) | 174.4(3) | 1.219(2) | ||||

| molecule 3 | |||||||

| 2.536(3)t | 178.2(3) | 1.219(2) | |||||

| 2.561(3)t | 170.3(3) | 1.220(2) | |||||

| molecule 4 | |||||||

| 2.557(3)t | 165.8(3) | 1.219(2) | |||||

| 2.539(3)t | 173.5(3) | 1.219(2) | |||||

| R=4-tBuC6H4 | 2b | 8 | 2.693(4)t | 180.0 | 166.4(2) | 1.194(6) | [15,16] |

| 2.707(5)t | 180.0 | 167.0(4) | 1.196(6) | ||||

| R=4-tBuC6H4 | 3b[c] | 8 | molecule 1 | [15,16] | |||

| 2.95(3)t | 180.0 | 119(2) | 1.183(1) | ||||

| 2.80(3)t | 172.8(9) | 128(2) | 1.183(1) | ||||

| 2.72(4)t | 173.6(1) | 129(2) | 1.183(1) | ||||

| 174.1(1) | 134.0(2) | 1.183(1) | |||||

| molecule 2 | |||||||

| 2.78(4)t | 180.0 | 123(3) | 1.183(1) | ||||

| 2.77(3)t | 171.7(8) | 153(3) | 1.183(1) | ||||

| 3.01(2)t | 172.2(1) | ||||||

| 171.4(8) | |||||||

| R=tBu | [MgR2(tmeda)2] | 6 | 2.180(2)t | 180.0 | 176.0(2) | 1.216(3) | [17,35] |

| R=tBu | [Ca{(NDippCMe)2CH}(CCR)]2 | 4 | 2.496(2)br | – | 111.6(1) | 1.216(2) | [28] |

| 2.510(1)br | 157.9(9) | ||||||

| R=tBu | 3c | 8 | 2.847(1)t | 180.0 | 148.6(8) | 1.198(2) | [16] |

| R=C6H5 | [Mg(CCR)2(tmeda)2] | 6 | 2.176(6)t | 180.0 | – | 1.219(8) | [36] |

| 2.200(6)t | 1.213(8) | ||||||

| R=C6H5 | [Ca{(iPr)4C5H}(CCR)(thf)] | 7 | 2.551(8)br | – | 123.7(6) | 1.173(9) | [27] |

| 2.521(7)br | 141.7(6) | ||||||

| R=C6H5 | [Ca{(NDippCMe)2CH}(CCR)]2 | 4 | 2.505(2)br | – | 96.6(8) | 1.224(2) | [28] |

| 2.535(2)br | 172.8(5) | ||||||

| R=C6H4Me | [Ca{(NDippCMe)2CH}(CCR)]2 | 4 | 2.492(2)br | – | 94.5(3) | 1.221(2) | [28] |

| 2.530(2)br | 174.4(2) |

Dipp=2,6-iPr2(CH6H3); CN = coordination number; br = bridging, t = terminal, d = dimeric,

Four independent molecules.

Two independent molecules, both with disorder over three positions.

We performed theoretical studies on the acetylides [M([18]crown-6)(CCtBu)2] (M = Ca, 1c; Sr, 2c; Ba, 3c) by using the Gaussian 03 program package at the B3LYP/LANL2DZ level.[30] The theoretical values were then compared with the stretching frequencies for the heavy alkaline-earth acetylides (1a–c, 2a–c, and 3a–c) as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative theoretical and experimental asym C≡C frequencies [cm−1].[a]

| M | Theory (R=tBu) | Exptl (R=SiPh3) | Exptl (R= | 4-tBuC6H4) | Exptl (R=tBu) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a, 2a, 3a | 1b, 2b, 3b | 1c, 2c, 3c | ||||||

| asym | Diff | asym | Diff | asym | Diff | asym | Diff | |

| Ca | 2099 | 0 | 1980 | 0 | 2032 | 0 | 2035 | 0 |

| Sr | 2085 | 14 | 1969 | 11 | 2004 | 28 | 2002 | 33 |

| Ba | 2075 | 24 | 1955 | 25 | 1997 | 35 | 1998 | 37 |

Diff=CaasymC≡C−Sr or BaasymC≡C.

Although the calculated values are consistently higher than the experimental data, the overall trend in the calculated values closely follows the experimental data, with a significant decrease in the asymmetric C≡C stretching frequencies upon descending Group 2, correlating with the increased atomic weight of the metal centers. Thus, the trend of stretching frequencies appears not to be indicative of any changes in metal–ligand or C≡C bond characteristics.

The crystallographic characterization of the target compounds proved to be challenging owing to the sensitivity of the compounds, the frequently observed poor crystal quality, small crystal size, large number of symmetry-independent molecules in some of the compounds, and/or severe disorder. This is illustrated in 1b in which the weakly diffracting crystals required a data collection at the Cornell High Energy Synchroton (CHESS) facility. The synchroton dataset revealed a rare scenario of four symmetry-independent molecules. Compound 3b displays ligand disorder over three positions, rendering a higher degree of uncertainty for bond lengths and angles. Despite numerous attempts to collect crystallographic data for compounds 1c and 2c, we were not successful.

Our initial work on heavy alkaline-earth-metal acetylides showed a significant decrease for the trans angle for the SiPh3-substituted acetylides 1a, 2a, and 3a. However, more striking than the decrease in the trans angle from 168.7(2) to 162.0(1)° (for 2a and 3a, respectively) is the decrease in the M-C≡C angle from 163(1)° to 133.9(6)° (average values for 1a and 3a, respectively). Figure 1 graphically depicts the progression of increased deviation from linear geometry upon descending Group 2 (1a, 2a, and 3a). Because our earlier work did not provide a rationale into the origins of the unexpected structural chemistry,[14] we herein introduce differently substituted acetylides to obtain a more detailed insight.

Figure 1.

Comparison of deviations from ideal geometry in 1a, 2a, and 3a. For clarity, only the metal–carbon framework is shown.

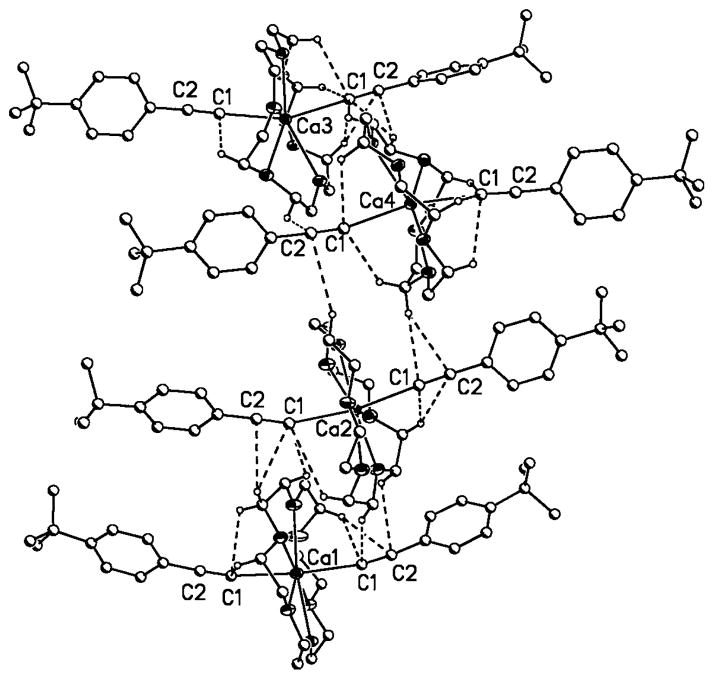

The initial analysis of the molecular geometries of the target compounds reveals a nontrivial picture, as demonstrated in 1b (Figure 2) in which each of the four symmetry-independent molecules displays a distinctly different molecular geometry. Table 3 provides a summary of the geometrical parameters for all compounds presented in addition to some pertinent literature data.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of 1b showing the four independent molecules. All hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

A common structural feature in 1a–3a, 1b–3b and 3c is the presence of eight-coordinate metal centers, achieved through coordination of [18]crown-6 and two acetylide ligands in the trans positions. Despite similar coordination numbers, the geometrical parameters for the target compounds are quite varied. The four independent molecules in 1b display a range of C-Ca-C angles (154.47(1)–173.17(1)°). The variation in the trans-angle geometry does not extend to all heavier metal analogues, for example, the strontium species 2b displays linear geometry. Furthermore, the two symmetry-independent molecules in 3b (Figure 3, showing disorder) are each disordered over three positions, but all display trans angles close to 180°. Likewise, the C-Ba-C angle for the tBu analogue 3c (Figure 4) is linear, as dictated by the presence of a center of symmetry. Overall, the trans angle trends in 1b, 2b, 3b, and 3c do not provide a consistent picture, as initially suggested by the SiPh3 species 1a, 2a, and 3a.

Figure 3.

Solid-state structure of 3b illustrating the three-position disorder. All hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Figure 4.

Solid-state structure of 3c. All hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Although the divergence from linear trans geometry is clear for some of the acetylides, a more severe deviation from ideal geometry is observed for the sp-hybridized Cipso atoms, which have M-C≡C angles as low as 119(2)° (3b). The four independent molecules in 1b display Cipso angles in the range of 160.2(2) to 178.2(3)°: values that are in good agreement with those in 1a (162.4(5)–164.0(5)°, Table 3). Likewise, structural data for 2b and 3b emphasize structural flexibility, with close-to-linear Sr-C≡C angles of 166.4(2)–167.0(4)° for 2b. In contrast, the two independent molecules in 3b, with their triple disorder, display a wide range of Ba-C≡C angles (119(2)–153(3)°) that are in good agreement with those in 3a (126.6(3) and 141.3(3)°). The corresponding values in 3c are observed at 148.6(8)° (Table 3).

In analogy with the variation in C-M-C and M-C≡C angles, a range of M–C bond lengths are observed. The Ca–C lengths in the four independent molecules in 1b (Figure 2) lie between 2.478(3)–2.561(3) Å with the corresponding values in 1a being slightly longer (2.523(7) and 2.558(7) Å). A similar trend is observed in 2b (2.693(4) and 2.707(5) Å) and 2a (2.692(4) and 2.723(4) Å), although the differences are less prominent. The trend is less smooth in the barium analogue with Ba–C lengths of 2.785(2) and 2.789(2) Å in 3a.[14] The two independent triply disordered molecules in 3b display a significant range of Ba–C lengths, some of which are shorter than in 3a, and some are longer (2.72(4)–3.01(2) Å). This range of bond lengths is likely the result of a challenging structure refinement. Surprisingly, the Ba–C bond lengths are shortest for 3a (Table 3).

The Ca–C bond lengths in compounds 1a (2.523(7)–2.558(7) Å) and 1b (2.478(3)–2.561(3 Å) compare favorably to the dimeric acetylide [Ca(N{(2,6-iPr2C6H3)CMe}2CH)(CC–MeC6H4)]2, which has bond lengths in the range 2.492(2)–51(8) Å (Table 3),[28] as well as the two-coordinate complex [Ca{CH(SiMe3)2}2] (with bond lengths of 2.459(9) Å).[13,32] Comparison of the acetylides [Sr{(Me3Si)2(MeOMe2Si)C}2-(MeOCH2CH2OMe)] (2.786(3) and 2.843(3) Å) indicate short Sr–C bonds for 2a (2.692(4) and 2.723(4) Å) and 2b (2.693(4) and 2.707(5) Å),[32] which are likely to be a consequence of the low carbon coordination number in the acetylides. This trend continues for barium, which has short Ba–C bond lengths in 3a (2.785(2) and 2.789(2) Å), 3b (2.72(4)–3.01(2) Å), and 3c (2.847(1) Å), as compared with [Ba([18]-crown-6)(CHPh2)2] (3.065(3) and 3.096(3) Å),[33] and [Ba-{(Me3Si)2(MeOMe2Si)C}2-(MeOCH2CH2OMe)] (3.036(2) and 3.049(2) Å).[32]

The C≡C bond lengths in the target compounds lie in a relatively narrow range for the SiPh3-substituted compounds 1a, 2a, and 3a (1.201(5)–36(5) Å). The values for the 4-tBuC6H4 compounds are found to be rather short at 1.219(2) and 1.220(2) Å for 1b, 1.194(6) and 1.196(6) Å for 2b, and 1.183(1) Å for 3b. The tBu analogue 3c follows the trend with a C≡C bond length of 1.198(2) Å.

As discussed above, a potential rationale for the M-C≡C bending was a metal–ligand side-on π interaction with the acetylinic system. This interaction would be favored for the heavier metal, and indeed, the largest degree of distortion was observed for the heavier metals. However, side-on overlap would coincide with a decrease in bond order, and should therefore result in elongated C≡C bond lengths. Notably, the shortest C≡C bonds are observed for the heaviest metals, which is an opposite trend to that expected if side-on overlap was a contributing factor.

The crown ether arrangement displays the familiar structural pattern upon descending Group 2.[16] Although perfectly planar for barium owing to a very tight crown–metal fit and a small range of Ba–Ocrown bond lengths (2.769(8)– 2.826(2) Å), the lighter metal derivatives display significantly increased crown flexibility, as reflected by the larger range of M–Ocrown lengths (2a, 2b: 2.671(3)–2.742(3) Å and 2.605(4)–2.713(4) Å; 1a, 1b: 2.605(4)–13(4) Å). The position of the crown in the equatorial plane is made possible by the narrow O-M-O angles (with average angles of 60.50(1)° for 1a, 60.32(8)° for 2a and 2b, and 60.31(5)° for 3a and 3c) as dictated by the ethylene linkages between the crown oxygen atoms.[14,25] Considering the larger deviation from strictly equatorial geometry, steric repulsion between the crown ether in the lighter metal compounds and the ligand should be more extensive than in the barium species. Interestingly, some of the largest deviations are observed for the heaviest metal species, and as such, crown ether geometry seems to be an unlikely structure-determining component in the target species.

VSEPR theory predicts a linear trans angle, as well as a linear arrangement for the M-C≡C moieties to reduce steric repulsion. The recently published magnesium analogues contribute to a more detailed analysis of structural trends. As expected, based on studies of cyclopentadienides,[2,3] magnesium acetylides display the least degree of deviation (Table 3)[17] with more significant deviations for the heavier metals, although the trend is much less smooth as initially suggested (see above). For example, a symmetry-imposed 180° trans angle is observed in [Mg(donor)n(CCSi(C6H5)3)2] (donor=THF, n=4; donor=TMEDA, n=2; TMEDA= N′,N′,N″,N″-tetramethylethane-1,2-diamine).[17] This angle decreases to 168.7(2) and 162.7(3)° for 1a and 3a, respectively. Likewise, a significant decrease in the M-C≡C angle is observed for the SiPh3 series, with angles in the range 173.2(8)–173.9(4)° for [Mg(donor){CCSi(C6H5)3}2], 162.4(5)–164.0(5)° for 1a, 158.9(9)–159.7(3)° for the calcium species 2a, and finally 126.6(3)–141.3(3)° for 3a.[14] The 4-tBuC6H4 series does not display a smooth trans-angle trend, but it does display a similar M-C≡C angle depression upon descending Group 2 with a bent angle as low as 119° for the barium species 3b. For the tBu-substituted compounds, structural data only exist for the magnesium and barium species, and both display C-M-C linear geometry, but again display a more pronounced M-C≡C angle depression for the heavier metal (176.0(2)° for [Mg(tmeda)2(CCtBu)2] compared with 148.6(8)° for 3c). Arguments about the origin of the structural deviations may be based on structural flexibility because ligand/crown steric repulsions may be less severe for the heavier metal species in which long metal–ligand bonds effectively decrease the ligand bulk. Comparison of ligand bulk and compound geometry should indicate the validity of this reasoning. Accordingly, the larger SiPh3-substi-tuted acetylides 1a–3a should exhibit a lesser degree of bending than the smaller C≡C–4-tBuC6H4- (1b–3b) or C≡CtBu-substituted compounds (3c). As outlined above, comparison of structural data does not reveal such a trend, in fact bending is most severe for the sterically more demanding ligand.

Because the argument of potential metal–ligand side-on overlap has been discredited (see above), the unexpected structural pattern may be based on the high s character of the sp-hybridized C atoms in the acetylide moiety, which results in facile distortion from ideal geometry. This argument, however, is only valid if a significant covalent-bonding contribution to the metal–ligand bond is considered. Although no data exist that allow an exact prediction of covalency, the high polar character of the alkaline-earth-metal bond is without doubt. Therefore, simple geometric arguments may be predominant.

To shed light onto the origins of the bending, DFT calculations performed on [Ba([18]crown-6)(CCSiPh3)2], 3a, indicate only a small energy difference between the D3d-symmetry-optimized structure (Ba-C≡C 180°) and the fully optimized structure (Ba-C≡C 157.7°) of Ci-symmetry 5.9 kcalmol−1 (Figure 5).[30] Natural bond order (NBO) calculations (B3LYP/LANL2DZ) were used to analyze the source of distortion and indicated that the degree of donor–acceptor interactions between a C≡CSi(C6H5)3 unit and an [18]crown-6 is larger in the Ci compared with the D3d structure. The Ci/D3d energy difference (6.4 kcalmol−1, B3LYP/SDD//B3LYP/LANL2DZ)[31] is sufficiently large that it could account for the favorable D3d→Ci stabilization (B3LYP/SDD//B3LYP/LANL2DZ, 5.7 kcalmol−1; B3LYP/LANL2DZ 5.9 kcalmol−1), suggesting that the distortions observed in 3a can be attributed to attractive interactions between the ethynyl moiety in the ligand and the H–C (σ*) orbitals of [18]crown-6 (Table 4 and Figure 5).[31] Similar observations were made by Winter and co-workers on barium–[18]crown-6-stabilized triazolato, tetrazolato, and pentazolato complexes in which intra- and intermolecular C–H···N contacts in the range 2.422–2.991 Å were used to explain the unexpected geometries.[32]

Figure 5.

Optimized structures of [M([18]crown-6)(CCtBu)2] in D3d and Ci point-group symmetry.

Table 4.

NBO second-order perturbation theory analysis of the Fock matrix at the B3LYP/SDD//B3LYP/LANL2DZ level.

| Donor–Acceptor | Energy [kcalmol−1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Ci | D3d | δ | |

| C≡CSiPh3–[18]crown-6 | 33.2 | 30.0 | 3.2 |

| [18]crown-6–C≡CSiPh3 | 14.7 | 11.5 | 3.2 |

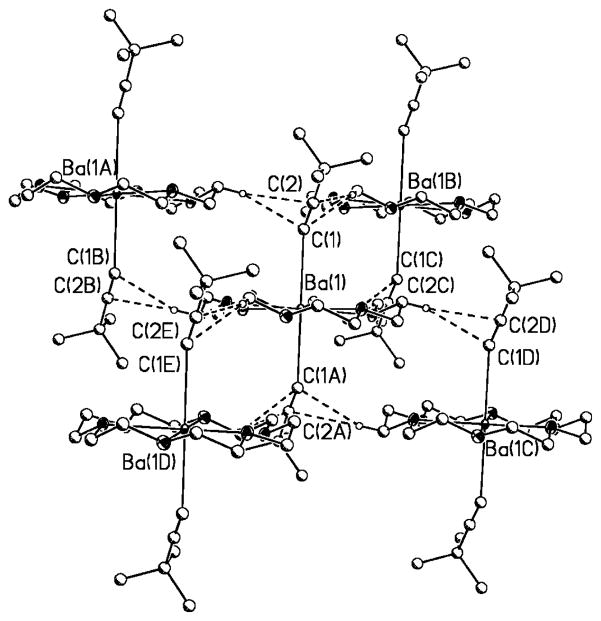

Indeed, close examination of the solid-state structures of 1a–3a confirmed the presence of weak intermolecular Ccrown–H···C≡C interactions in the range 2.624–2.927 Å (H atoms on calculated positions with no influence on C≡C bond lengths). Figures 6–8 illustrate these interactions. Values for all inter- and intramolecular interactions have been summarized in Table S1 in the Supporting Information.

Figure 6.

Intermolecular Ccrown–H···CC≡C in 3a. Hydrogen atoms not involved in the short contacts are omitted for clarity.

Figure 8.

Intermolecular Ccrown–H···CC≡C in 3c. Hydrogen atoms not in- volved in the short contacts are omitted for clarity.

Solid-state data on compounds 1b, 2b, 3b, and 3c also confirm Ccrown–H···C≡C interactions in the range 2.570–3.075 Å (Table S1 in the Supporting Information), and [Mg([15]crown-5)(CC-4-tBuC6H4)2], the only magnesium acetylide with a significant degree of trans bending, also supports this interpretation. In agreement with the heavier metal congeners, several significant intra- and intermolecular interactions were identified, providing a rationale similar to that proposed for 1a, 2a, and 3a to explain the deviation from linear geometry.[17]

Conclusion

Detailed analysis of a family of alkaline-earth-metal acetylides is providing a unique insight into factors governing the overall bending trends in this family of compounds. Whereas initial data based on the SiPh3-substituted acetylides 1a, 2a, and 3a suggested a smooth trend, analysis of the tertiary butyl, and 4-tertiary butylphenyl acetylides suggest that donor–acceptor interactions between the acetylinic moiety and the crown ether are responsible for the deviations from ideal geometry.

Experimental Section

General

Owing to the high reactivity of the target compounds, complete characterization of the acetylides proved to be challenging. Elemental analysis, even when air-sensitive sample handling was requested, provided inconsistent results. Several of the samples immediately decomposed after removal of the mother liquor in a freshly regenerated dry box, and thus we were unable to ship them to an external laboratory.

All compounds were spectroscopically characterized by using 1H, 13C NMR, and IR spectroscopy. Difficulties were encountered in the observation of the acetylenic carbon atoms in the 13C NMR spectra despite increased relaxation delays and extensive run times.

All manipulations were carried out under inert-gas conditions with the use of a Schlenk line and standard dry-box techniques. All solvents including THF, n-hexane, and 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME) were purified prior to use from Vacuum Atmospheres dri-solv solvent purifier system, followed by degassing by two freeze–pump–thaw cycles. The alkynes were commercially obtained and dried over calcium hydride before use. [18]crown-6 was commercially obtained and recrystallized in hexane after heating at reflux overnight over finely cut sodium metal. The alkaline-earth-metal amides and dibenzyl derivatives were prepared according to literature procedures.[15,20,23] 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were collected on a Bruker DPX-300 spectrometer. The chemical shifts were referenced to the residual solvent signals ([D6]benzene: δH = 7.16, δC = 128.38 ppm; [D8]THF: δH = 1.73, 3.58, δC = 25.37, 67.57 ppm). Infrared spectra were obtained on a Perkin–Elmer Paragon 1000 FT-IR by using KBr plates. The melting points were acquired on a MelTemp apparatus in capillaries sealed under nitrogen and were uncalibrated. Likewise, melting point detection provided inconsistent results, even in sealed capillary tubes and when taken consecutively from the sample. The reported yields are not optimized and relate to the crystals grown and isolated for crystallographic studies.

All compounds reported herein were prepared by transamination and toluene elimination. The spectral and crystallographic analysis of the sample batches prepared by the two routes was identical.

General procedure for transamination

The alkyne ligands HCC-4- tBuC6H5 or HCCtBu (2 mmol) were slowly added by syringe to a solution of [M{N(SiMe3)2}2(thf)2] (1 mmol; M = Ca, Sr, Ba) in THF or DME (10–15 mL) at −78°C. A solution of [18]crown-6 (1 mmol) in THF or DME (10–15 mL) was slowly added to the resulting colorless reaction mixture. The reaction mixtures were stirred for 2–3 h at −78°C. The resulting light-yellow-to-colorless solutions were filtered and stored in a freezer at −23°C. Clear, colorless crystalline plates of the target compounds formed within a few days.

General procedure for toluene elimination

The alkyne ligands HCC-4-tBuC6H5 or HCCtBu (2 mmol) were slowly added by syringe to a solution of [M(CH2Ph)2] (1 mmol; M = Ca, Sr, Ba) in THF or DME (10–15 mL) at −78°C. A solution of [18]crown-6 (1 mmol) in THF or DME (10–15 mL) was slowly added to the resulting colorless reaction mixture. The resulting light-yellow-to-colorless solution was stirred for 2–3 h at −78°C, then filtered and stored in a freezer at −23°C. Clear, colorless crystalline plates formed within a few days.

[Ca(18-crown-6)(CC-4-tBuC6H4)2] (1b)

HCC-4-tBuC6H5 (0.40 mL, 2.0 mmol), [Ca{N(SiMe3)2}2(thf)2] (0.50 g, 1.0 mmol) or [Ca(CH2Ph2)2] (0.22 g, 1.0 mmol), and [18]crown-6 (0.26 g, 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in THF (15–20 mL). Compound 1b was obtained as thin, clear colorless crystalline plates from THF after storage at −23°C for one to two days (yield: 0.30 g, 55%). M.p. 165°C (the crystals darken at 120°C); 1H NMR (300 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ= 1.19 (s, 18H; tBu), 3.47 (s, 24H; crown), 7.21 (d, 4H; phenyl), 7.70 ppm (d, 4H; phenyl); 13C NMR (75 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ=30.30 (CMe3), 32.59 (CMe3), 68.06 (crown), 107.25 (MCCR), 145.25 (MCCR), 122.51, 126.88, 129.17, 143.69 ppm (phenyl); IR (KBr plates): ν̄=2904.5, 2723.0, 2287.7, 2031.5, 1894.2, 1601.1, 1461.1, 1376.7, 1285.0, 1249.3, 1201.6, 1177.2, 1102.8, 972.4, 887.9, 831.6, 779.1, 722.4, 560.3 cm−1.

[Sr([18]crown-6)(CC-4-tBuC6H4)2] (2b)

HCC-4-tBuC6H5 (0.40 mL, 2.0 mmol), [Sr{N(SiMe3)2}2(thf)2] (0.55 g, 1.0 mmol) or [Sr(CH2Ph2)2] (0.27 g, 1.0 mmol), and [18]crown-6 (0.26 g, 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in THF (15–20 mL). Thin, clear colorless plates are formed from the THF solution at −23°C within 48 h (yield: 0.40 g, 54%). M.p. 220°C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ=1.20 (s, 18H; tBu) 3.37 (s, 24H; crown), 7.21 (d, 4H; phenyl), 7.69 ppm (d; phenyl); 13C NMR (75 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ=31.23 (CMe3), 33.95 (CMe3), 69.07 (crown), 109.37 (MCCR), 145.43 (MCCR), 119.57, 124.54, 131.02, 152.97 ppm (phenyl); IR (KBr plates): ν̄=2921.7, 2725.5, 2284.4, 2004.0, 1600.8, 1462.0, 1376.7, 1348.8, 1284.0, 1261.5, 1244.0, 1174.0, 1098.4, 971.8, 829.3, 722.0 cm−1.

[Ba([18]crown-6)(CC-4-tBuC6H4)2] (3b)

HCC-4-tBuC6H5 (0.40 mL, 2.0 mmol), [Ba{N(SiMe3)2}2(thf)2] (0.60 g, 1.0 mmol) or [Ba(CH2Ph2)2] (0.32 g, 1.0 mmol), [18]crown-6 (0.26 g, 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in THF (15–20 mL). Thin, clear colorless plates are formed from the THF solution at −23°C within 48 h (yield: 0.61 g, 70%). M.p. 210°C (the clear colorless crystals turned white at 120°C and then blacken upon melting); 1H NMR (300 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ= 1.20 (s, 18H; tBu) 3.38 (s, 24H; crown), 7.06 (d, 4H; phenyl), 7.47 ppm (d; phenyl); 13C NMR (75 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ=32.05 (CMe3), 34.72 (CMe3), 71.02 (crown), 125.15, 132.24, 147.05, 157.77 ppm (phenyl); IR (KBr plates): ν̄=2925.3, 2847.7, 2108.1, 1997.7, 1956.9, 1891.5, 1654.5, 1605.5, 1458.3, 1376.6, 1282.6, 1111.0, 959.8 cm−1.

[Ca(CCtBu)2(thf)n] (1c)

HCCtBu (0.25 mL, 2.0 mmol) and [Ca{N-(SiMe3)2}2(thf)2] (0.50 g, 1.0 mmol) or [Ca(CH2Ph2)2] (0.22 g, 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in THF (15–20 mL). Clear colorless plates formed within two days after layering the mixture with hexane (yield: 0.30 g, 55%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ= 1.09 (s, 18H; tBu), 1.49 (t, 16H; THF), 3.59 ppm (t, 16H; THF); 13C NMR (75 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ= 26.40 (THF), 28.70 (CMe3), 31.30 (CMe3), 67.77 ppm (MCCR); IR (KBr plates,): ν̄=2909.0, 2218.4, 2177.5, 2148.9, 2034.5, 1932.4, 1589.1, 1458.3, 1280.7, 1360.3, 1254.0, 1200.9, 1180.5, 1045.6, 927.1 cm−1.

[Sr([18]crown-6)(CCtBu)2] (2c)

HCCtBu (0.25 mL, 2.0 mmol), [Sr{N-(SiMe3)2}2(thf)2] (0.55 g, 1.0 mmol) or [Sr(CH2Ph2)2], and [18]crown-6 (0.26 g, 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in DME (15–20 mL). Clear colorless plates formed within two days after layering the mixture with hexane (yield: 0.29 g, 51%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ= 1.16 (s, 18H; tBu), 3.51 ppm (s, 24H; crown); 13C NMR (75 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ= 28.13 (CMe3), 31.25 (CMe3), 68.80 (MCCR), 71.48 ppm (crown); IR (KBr plates): ν̄=2949.8, 2921.2, 2851.8, 2157.1, 2022.3, 1997.73, 1458.3, 1384.8, 1249.9, 1192.7, 1106.9, 1033.4, 963.9 cm−1.

[Ba([18]crown-6)(CCtBu)2] (3c)

HCCtBu (0.25 mL, 2.0 mmol), [Ba{N-(SiMe3)2}2(thf)2] (0.60 g, 1.0 mmol) or [Sr(CH2Ph2)2] (0.32 g, 1.0 mmol), and [18]crown-6 (0.26 g, 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in DME (15–20 mL). Clear colorless plates formed within two days after layering the mixture with hexane (yield: 0.19 g, 40%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ= 1.13 (s, 18H; tBu), 3.53 ppm (s, 24H; crown); 13C NMR (75 MHz, 25°C, [D6]benzene): δ= 31.32 (CMe3), 32.07 (CMe3), 72.74 ppm (crown); IR (KBr plates): ν̄=3060.2, 3027.5, 2815.0, 2721.0, 2602.5, 2394.1, 2238.8, 2177.53, 2132.6, 2054.9, 2001.8, 1948.7, 1871.1, 1797.5, 1740.3, 1601.4, 1495.1, 1450.2, 1372.5, 1372.5, 1307.2, 1029.3, 984.3 cm−1.

X-ray crystallographic studies

Data collection and refinement

All crystal data (except for compound 1b) were collected by using a Bruker SMART system with a three-circle goniometer and a SMART APEX-CCD detector. Data were collected by using MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) and narrow (0.3° in Θ) frame exposures. A hemisphere of data was collected for each sample at low temperatures by using a low-temperature device build by H. Hope (University of California, Davis).

X-ray-quality crystals for all compounds were grown as described in the experimental section. Crystal mounting and data collection procedures for all compounds except 1b have been previously described.[33] Absorption corrections were applied by using SADABS and the crystal structures were solved by using direct and/or Patterson methods, and subsequent refinement was performed by using full-matrix least-squares methods on F2 utilizing SHELXS-97 and SHELXL-97.[34] All nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically.

Generally, the crystals were submerged under inert gas in highly viscous hydrocarbon oil (Infineum), mounted on a glass fiber, and placed in the low-temperature stream on the diffractometer.

Crystallographic data for compound 1b was acquired at the F1 beamline at CHESS by using an ADSC Q-270 detector that was offset to allow higher resolution.[35] The wavelength used was λ=0.91756 Å. The cell parameters and absorption correction were refined and applied through HKL2000.[36] The crystal structure was solved by using direct methods (SHELXS-97) and refined by using full-matrix least-squares methods on F2 utilizing SHELXL-97.[33] All nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically.

In compound 2b, the solvent of crystallization (THF) displayed unresolvable disorder. It was removed from the refinement by using “squeeze” option available in the Platon program suite.[37,38]

Crystallographic data for 3b indicated complex disorder, including three independent ligand positions. Furthermore, two independent molecules are present, the metal centers of which reside on centers of symmetry. Intensity data for 3c are weak (I/σ=5.64) despite long exposure time (40 sframe−1).

Further details about the refinements and how disorder was handled are outlined in the Supporting Information. CCDC-727576 (1b), CCDC-727577 (2b), CCDC-727575 (3b), and CCDC-727574 (3c) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Crystallographic data

1b: C42H56O7.50Ca; Mr = 720.95; colorless thin plates; 0.035×0.015×0.006 mm; triclinic; space group P1̄; a=15.450(3), b=21.590(4), c= 26.270(5) Å; α=75.99(3), β=77.98(3), γ=88.85(3)°; V=8311(3) Å3, T= 293(2) K; Z=8; λ=0.91750 Å; 16502 independent reflections (3.66≤ 2θ≤64.08°); R1 = 0.0645 for data [I > 2σ(I)]; wR2 = 0.1803 for all data.

2b: C44H66O8Sr; Mr = 810.59; colorless plates; 0.50×0.50×0.06 mm; triclinic; space group P1̄; a=10.691(3), b=11.702(3), c=17.892(5) Å; α= 89.739(4), β=81.084(4), γ=89.601(4); V=2211.39(9) Å3; T=98(2) K; Z=1; μ (MoKα) = 1.259 mm−1; 18229 independent reflections (3.48≤2θ≤ 57.28°); R1 = 0.0670 for data [I > 2σ(I)]; wR2 = 0.1778 for all data.

3b: C44H60BaO7; Mr = 836.26; colorless plates; 0.20×0.20×0.02 mm; triclinic; space group P1̄; a=7.6200(13); b=14.711(3); c=20.125(4) Å; α= 77.082(3), β=84.500(3), γ=89.654(4)°; V=2188.5(7) Å3; T=100(2) K; Z=2, μ (MoKα) = 0.952 mm−1; 7701 independent reflections (2.84≤2θ≤ 50.42°); R1 = 0.0818 for data [I > 2σ (I)]; wR2 = 0.2229 for all data.

3c: C24H42O6Ba; Mr = 563.91; colorless plates 0.20×0.12×0.12 mm; triclinic; space group P1̄; a=7.5126(2), b=7.7275(2), c=12.079(2) Å; α= 89.40(3), β=87.54(3), γ=81.40(3); V=692.7(2) Å3; T=94(2) K; Z=1, μ (MoKα) = 1.352 mm−1; 6203 independent reflections (3.38≤2θ≤56.7°); R1 = 0.0956 for data [I > 2σ(I)]; wR2 = 0.2601 for all data.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7.

Intra- and intermolecular Ccrown–H···CC≡C in 1b. Hydrogen atoms not involved in the short contacts are omitted for clarity.

Acknowledgments

Support from the National Science Foundation (grants CHE-0505863 and 0753807) is gratefully acknowledged. Purchase of the X-ray diffractometer was made possible with grants from NSF (CHE-95-27898), the W.M. Keck Foundation, and Syracuse University. Part of the crystallographic work is based upon research conducted at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS), which is supported by the National Science Foundation under award DMR 0225180, and by using the Macromolecular Diffraction at CHESS (MacCHESS) facility, which is supported by award RR-01646 from the National Institutes of Health, through its National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Professor Werner Massa on the occasion of his 65th birthday

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.200901538.

References

- 1.Hargittai M. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2233–2301. doi: 10.1021/cr970115u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elschenbroich C. Organometallics. 3. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollis TK, Burdett JK, Bosnich B. Organometallics. 1993;12:3385–3386. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sitzmann H, Dezember T, Ruck M. Angew Chem. 1998;110:3293–3296. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981204)37:22<3113::AID-ANIE3113>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:3113–3116. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981204)37:22<3113::AID-ANIE3113>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guido M, Gigli G. J Chem Phys. 1976;65:1397–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von Szentpály L, Schwerdtfeger P. Chem Phys Lett. 1990;170:555–560. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeKock RL, Peterson MA, Timmer LK, Baerends EJ, Vernooijs P. Polyhedron. 1990;9:1919–1934. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Fernandez P, Bersuker IB, Boggs JE. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:10409–10415. doi: 10.1021/jp073207o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaupp M, von P, Schleyer R, Stoll H, Preuss H. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6012–6020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaupp M, von P, Schleyer R, Stoll H, Preuss H. J Chem Phys. 1991;94:1360–1366. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaupp M, von P, Schleyer R. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:491–497. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaupp M, von P, Schleyer R, Dolg M, Stoll H. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:8202–8208. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaborn C, Hawkes SA, Hitchcock PB, Smith JD. Chem Commun. 1997:1961–1962. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green DC, Englich U, Ruhlandt-Senge K. Angew Chem. 1999;111:365–367. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<354::AID-ANIE354>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 1999;38:354–357. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<354::AID-ANIE354>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander JS. PhD Thesis. Syracuse University (Syracuse); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guino-o MA. PhD Thesis. Syracuse University (Syracuse); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guino-o MA, Baker E, Ruhlandt-Senge K. J Coord Chem. 2008;61:125–136. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander JS, Zuniga MF, Guino-o MA, Hahn R, Ruhland-Senge K. In: Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. 2. Atwood DA, editor. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 116–147. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander JS, Ruhlandt-Senge K. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2002:2761–2774. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westerhausen M. Coord Chem Rev. 1998;176:157–210. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillett-Kunnath MM, MacLellan JG, Forsyth CM, Andrews PC, Deacon GB, Ruhlandt-Senge K. Chem Commun. 2008:4490–4492. doi: 10.1039/b806948d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weeber A, Harder S, Brintzinger HH, Knoll K. Organometallics. 2000;19:1325–1332. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harder S, Müller S, Hübner E. Organometallics. 2004;23:178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruhland-Senge K. unpublished results [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green DC. MS Thesis. Syracuse University (Syracuse); 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka Y, Arakawa M, Yamaguchi Y, Hori C, Ueno M, Tanaka T, Imahori T, Kondo Y. Chem Asian J. 2006;1:581–585. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burkey DJ, Hanusa TP. Organometallics. 1996;15:4971–4976. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avent AG, Crimmin MR, Hill MS, Hitchcock PB. Organometallics. 2005;24:1184–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coles MA, Hart FA. J Organomet Chem. 1971;32:279–284. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Notes and References for B3LYP/LAND2DZ. Geometries have been optimized with the hybrid density functional method, B3LYP, and the LANL2DZ basis set level which replaces the core electrons with a pseudopotential. Analysis of the wave function was made with the NBO analysis. All calculations were carried out with the G03 program system. B3LYP: Becke AD. Phys Rev A. 1988;38:3098–3107. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098.Becke AD. J Chem Soc. 1998;98:1372–1380.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785.LANL2DZ: Hay PJ, Wadt WR. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:299–310.Hay PJ, Wadt WR. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:270–283.Wadt WR, Hay PJ. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:284–298.NBO: Reed AE, Curtiss LA, Weinhold F. Chem Rev. 1988;88:899.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe MW, Gill PM, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03, Revision D.01. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford CT: 2004.

- 31.Kaupp M, von P, Schleyer R, Stoll H, Preuss H. J Chem Phys. 1991;94:1360–1366. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobrsi I, Knox JE, Heeg MJ, Schlegel HB, Winter CH. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:4894–4896. doi: 10.1021/ic048171i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chadwick S, Ruhlandt-Senge K. Chem Eur J. 1998;4:1768–1780. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheldrick GM. SHELX-97, Program for Crystal Structure Refinement. Universität Göttingen; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.For the ADSC CCD: Szebenyi DME, Arvai A, Ealick S, LaIuppa JM, Nielsen C. J Synchrotron Rad. 1997;4:128–135. doi: 10.1107/S0909049597000204.

- 36.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. In: Carter CW Jr, Sweet RM, editors. Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 276: Macromolecular Crystallography, Part A. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 307–326. HKL2000 notes. The development of HKL2000 is supported by NIH grant GM-53163 to Z. Otwinowski and W. Minor. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van der Sluis P, Spek AL. Acta Crystallogr Sect A. 1990;46:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- 38.PLATON Revision 1.07. A. L. Spek; Utrecht: 1990. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.