Abstract

Purpose

Most medical schools and residency programs offer international medical electives [IMEs], but there is little guidance on educational objectives for these rotations. We reviewed the literature to compile and categorize a comprehensive set of educational objectives for IMEs.

Methods

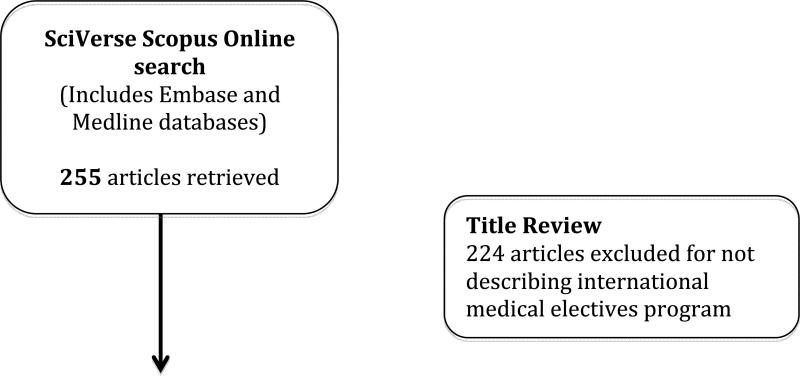

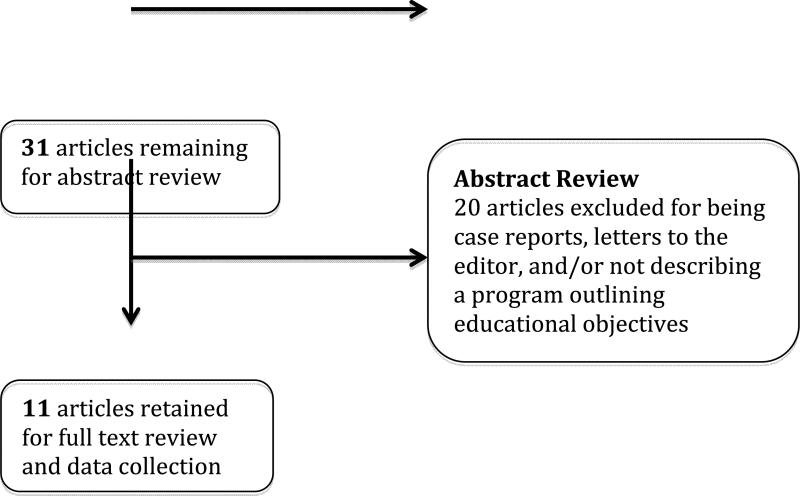

We conducted a narrative literature review with specified search criteria using SciVerse Scopus online, which includes Embase and Medline databases. From manuscripts that met inclusion criteria, we extracted data on educational objectives and sorted them into pre-elective, intra-elective, and post-elective categories.

Results

We identified and reviewed 255 articles, of which 11 (4%) manuscripts described 22 unique educational objectives. Among those, 5 (23%), 15 (68%), and 2 (9%) objectives were categorized in the pre-elective, intra-elective, and post-elective periods, respectively. Among pre-elective objectives, only cultural awareness was listed by more than two articles (3/11, 27%). Among intra-elective objectives, the most commonly defined objectives for students were enhancing clinical skills and understanding different health care systems (9/11, 82%). Learning to manage diseases rarely seen at home and increasing cultural awareness were described by nearly half (5/11, 46%) of all papers. Among post-elective objectives, reflecting on experiences through a written project was most common (9/11, 82%).

Conclusions

We identified 22 unique educational objectives for IMEs in the published literature, some of which were consistent. These consistencies can be used as a framework upon which institutions can build their own IME curriculums, ultimately helping to ensure that their students have a meaningful learning experience while abroad.

As the world has become increasingly interconnected, developing an understanding of global health has become an essential component in training a competent 21st century physician.1 As recognition of the importance of global health has expanded, medical students and residents have increasingly chosen to participate in international medical electives [IMEs].1,2,3 In recent surveys, 30.8% of US and Canadian medical students, and 40% of UK medical students, had engaged in IMEs during medical school.4,5 By 2010, every Canadian medical school had a program that allowed their students to engage in IMEs.6

Despite the growing number of participants, there has been no clear consensus on appropriate educational objectives of IMEs. Consequently, students are often underprepared for their electives3,7,8 and can readily denigrate into “medical tourism”.3 Over the past decade, student-led initiatives and faculty collaborations have been developing a standardized global health curriculum with core competancies.2,3,6,9,10,11,12,13 In the development of core competencies for global health there has been some discussion of international medical electives [IMEs], but little attention given towards their overall structure and educational objectives. Therefore, we conducted a narrative literature review to identify educational objectives of IMEs.

Methods

Data sources and search strategies

We conducted a narrative review for articles related to educational goals in IMEs using SciVerse Scopus online [SVSo]. We used SVSo due to its incorporation of both Embase and Medline databases, as well as indexing multiple journals in various fields. We searched for articles containing “medicine” OR “health” OR “medical, elective”, “international” OR “global”, “curriculum” OR “education” combined simultaneously with the Boolean operation AND. The search was conducted between the dates of February 6 to 20, 2012 and July 27 to 29, 2012. The search was limited to English language publications. We defined and agreed upon the search terms before accessing SVSo.

Study Selection

We retrieved titles and abstracts for all manuscripts. We eliminated articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria of describing an institutional experience with developing or assessing one or more IMEs. We excluded case reports, opinion pieces, and articles that did not specifically describe educational objectives. We reviewed references from retrieved articles to identify additional applicable publications.

Data Collection and Synthesis

The first author extracted all data, and categorized educational objectives as either pre-elective, intra-elective, or post-elective. We determined the frequency that each educational objective was identified in the literature.

Results

Articles Identified in Search Strategy

In total, we identified 255 articles, of which we excluded 224 (88%) for not describing an IME (Figure 1). Of the 31 articles reviewed in detail, we excluded 25 (81%) for not describing educational objectives or for being opinion pieces. The final 11 articles contained data on 22 unique educational objectives for IMEs (Table 1). These articles were developed by authors from across the globe, were evenly distributed between medical student and resident electives, but varied widely in their years of experience and IME destination (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Search strategy for identifying articles describing a curriculum for an institutional experience with an IME.

Table 1.

Programs describing educational objectives for international medical electives.

| Papers | Medical student [MS] or resident [R] elective | Institution | Years of IME experience | Major IME destination(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miranda et al 2005 | MS | University College London [UCL] | 4 | Bangladesh, Brazil, Cuba, Ecuador, India, Nepal, Peru, Tanzania and Zambia |

| Valani et al 2011 | MS | McMaster University [MMU] | 8 | Toronto* |

| Nishigori et al 2009 | MS | University of Tokyo [UT] | 4 | Japan and the UK |

| Frederico 2006 | R | University of Colorado [UCol] | 6 | Peru and Guatemala |

| Vora et al 2010 | MS | Chicago Medical School and Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science [CMS] | 1 | India, Nepal, China, South Korea, Vietnam, Ecuador, Czech Republic, Armenia and Ghana |

| Silverberg et al 2007 | R | Mount Sinai School of Medicine [MSSM] | 1 | The Dominican Republic |

| Imperato et al 1996 | MS | State University of New York, Downstate Medical Center [SNYMC] | 25 | India, Kenya, Thailand (most prevalent) |

| Diston et al 2009 | R | The University of California at San Fransisco [UCSF] | 8 | South Africa |

| Holmes et al 2012 | MS | University of Buffalo [UB] | ~30 | Costa Rica, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, India, England, Ireland, Switzerland, Congo, Lesotho, Mozambique |

| McIntosh et al 2012 | R | University of Florida College of Medicine [UFCM] | 1 | Paraguay |

| Sawatsky et al 2010 | R | The Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education [MSGME] | 7 | Kenya, Haiti, Nepal, Tanzania, India, Jamaica, Mexico |

Elective includes students from Jordan and Israel

Educational Objectives

We identified 5 unique educational objectives for IMEs for the pre-elective time period (Table 2). Of those, only “increasing cultural awareness” was cited by more than two articles. McIntosh et al. at UFCM described all pre-elective educational objectives. Only 3/11 (27%) articles described a pre-elective educational objective in their institutional experience.

Table 2.

Educational objectives and the institutions reporting them.

| Pre-elective educational objectives | N (%) | Institutions |

|---|---|---|

| Building knowledge of tropical medicine | 18 | UCol, UFCM |

| Increasing cultural awareness | 27 | UCol, SNYMC, UFCM |

| Understanding culture shock | 9 | UFCM |

| Language training | 9 | UFCM |

| Learning about resource availability | 18 | SNYMC, UFCM |

|

Intra-elective educational objectives | ||

| Attending lectures | 18 | MMU, UCol |

| Enhancing clinical skills | 82 | UCL, UCol, CMS, MSSM, SNYMC,UCSF, UB, UFCM, MSGME |

| Learning research methodology | 9 | MMU |

| Engaging in research projects | 18 | UCL, MMU |

| Learning a foreign language | 27 | UCol, UB, UFCM |

| Maintaining and reviewing data entry logs (diseases, procedures, patient demographics) | 36 | UCol, CMS, UFCM, MSGME |

| Understanding different health care systems | 82 | UCL, MMU, UT, UCol, CMS, SNYMC, UB, UFCM, MSGME |

| Learning about common health concerns in developing world | 36 | UCol, MSSM, SNYMC, UFCM |

| Understanding clinical ethics | 27 | UT, MSSM, UFCM |

| Increasing cultural awareness | 46 | MSSM, SNYMC, UCSF, UB, UFCM |

| Learning to manage diseases rarely seen at home | 46 | MMU, UT, MSSM, UB, UFCM |

| Understanding differences in medical education | 36 | UCL, UT, UCol, SNYMC |

| Gaining surgical experience | 27 | MSSM, UCSF, UB |

| Functioning in low resource settings | 27 | CMS, UCSF, UFCM |

| Understanding cultural differences in treating patients | 64 | UCL, MMU, UT, UCol, CMS, UCSF, UFCM |

|

Post elective educational objective | ||

| Understanding culture shock | 9 | UCol |

| Reflecting on experiences | 82 | UCL, MMU, UT, UCol, MSSM, SNYMC, UFCM, MSGME |

Table 2 also outlines the 15 educational objectives that were identified for the elective period itself. The most common objectives were “enhancing clinical skills” and “understanding different health care systems” (both were 9/11, 82%). Sixty-four percent (7/11) and 46% (5/11) also mentioned, “understanding cultural differences in treating patients” and “increasing cultural awareness”/” Learning to manage diseases rarely seen at home”, respectively. Four of 11 (36%) described “maintaining and reviewing data entry logs”, “Learning about common health concerns in the developing world” and “understanding differences in medical education”. McIntosh et al. at UFCM described the most intra-elective educational objectives (10/15, 67%)

We identified only two educational objectives for the post-elective period (Table 2). The two educational objective identified were “composing a reflection of experiences” (9/11,82%) and “Understanding culture shock” (add numbers).

Discussion

In this comprehensive review, we identified 22 educational objectives for the pre-elective, intra-elective and post-elective periods of an IME, as described by different institutions.

In general, when discussing the pre-elective period the literature focused primarily on logistic factors and did not emphasize educational objectives. The most common pre-elective educational objective was “increasing cultural awareness” (3/11, 27%). The lack of emphasis on pre-departure training was a surprising discovery given the increased consideration towards the importance of preparing students before they embark on an IME.6 Ideally, future publications of institutional experiences with IMEs will focus more on educational objectives for the pre-elective period, sharing their educational designs with other institutions, and ultimately better preparing students for their experiences abroad.

We found that the majority of educational objectives (15/22, 68%) were related to the intra-elective period. They were developed by institutional faculty members in advance, or listed by medical students and residents in written pre-departure questionnaires. The most common intra-elective educational objectives were “enhancing clinical skills” and “understanding different healthcare systems” (9/11, 82%). It has repeatedly been shown that when students engage in IMEs they improve clinical skills, often due to limited access to expensive investigations and an increased focus on history and physical examination. Setting an educational objective for students to enhance their clinical skills is simply an extension of an already defined benefit of IMEs. Moreover, as a result of building clinical skills students will gain confidence becoming better able to work with foreign medical professionals, achieving the educational objectives of “understanding different healthcare systems” and “understanding cultural differences in treating patients” (9/11, 82% and 7/11, 64% respectively).

The educational objective of “maintaining and reviewing data entry logs” was cited by 4/11 (36%) of articles. By reflectively thinking about patient presentations and reviewing what they have seen, students would know where to focus their attention and what cases they should try to see before completing their IME. Additionally, educators at their home institution, as well as the host institution, would be able to quantitatively assess the experiences gained ensuring that students obtain maximal exposure. Once home, students could then review their logbooks to assist in compiling reflective pieces.

Out of the 22 educational objectives found in the literature only 2 (9%) were related to the post-elective period. Of these, the educational objective of “reflecting on experiences” was most common (9/11, 82%). Reflecting on experiences has been shown to be an important part of learning in medicine.22,23 Through reflection students are able to critically think about their experiences and put their thoughts into an organized fashion. Given the dramatic differences in health care and clinical practice abroad, composing a reflective piece is an important objective for students to continue learning once they have arrived back in their home environment.

Upon reviewing the literature, there appears to be a need for consensus on IMEs, yet little has been written specifically addressing educational objectives. In 1999 the American Academy of Pediatrics did develop a consensus set of guidelines for international child health electives [ICHEs].7 These describe some logistic factors such as how much experience a resident should have before engaging in an elective (18 months), how long the rotation should last (4 weeks) and how to provide appropriate supervision. 7 They address pre-departure training stating that, “orientation prior to the elective should address cross-cultural awareness, health, and personal safety”. 7 As well, they mention that, “the resident should prepare written objectives prior to the elective” but do not provide specific examples of appropriate objectives. 7 In the AAP guidelines there were some points that suggested an emphasis on “hands-on” clinical experiences (similar to our objective of “increasing clinical skills”), and that post-elective the resident should summarize their experiences in a written or oral presentation and engage in a debriefing session (similar to “reflecting on experiences”).7

While we included all applicable data, there were some limitations. Our search terms could have missed some articles describing educational objectives, and we did not attempt to identify non-English language articles.. Finally, we searched two widely used databases for manuscripts, which should have encompassed the most relevant articles.

Conclusions

We identified that some institutions are providing students with defined educational objectives for IMEs, and that these educational objectives predominantly focus on the intra-elective period (15/22, 68%). We found it surprising that little attention was dedicated to the pre-elective period (5/22 or 23% of educational objectives and only 3/11 or 36% of institutions), and that relative to the interest in Global Health and IMEs, so few institutional experiences were published in the literature at all (11 in total). Through the American Academy of Pediatrics there has been a push to define ICHEs core competency guidelines, but this work requires generalization to additional subspecialties as well as to medical students and residents as a whole.

It is important to note that no medical trainee would be sent into a North American hospital without appropriate guidance and structure for their learning experience, and IMEs and their host institutions should be held in the same regard. Institutions should focus on developing and implementing educational objectives to better prepare their students for IMEs. Through developing and refining educational objectives and publishing experiences with IMEs a framework will be created for institutions to develop their own IMEs curriculum best suited for their own medical students and residents. There is much work to be done with respect to evolving these programs, and future research is needed to address the logistic objectives of an IME and the impact that it has on host communities if undertaken to the developing world. Through these efforts it will be possible to decrease medical tourism, increase educational benefits of rotations, and perhaps ultimately lead to the development of partnerships and mutual exchanges of knowledge and resources.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Drain was supported by the Harvard Global Health Institute, the Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988), and a Program for AIDS Clinical Research Training grant (T32 AI007433).

Contributor Information

William A. Cherniak, Family Medicine resident at The Scarborough Hospital, The University of Toronto, Faculty of Medicine, Toronto, Cananda..

Paul K. Drain, Infectious Disease Physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA..

Timothy F. Brewer, Director of Global Health Programs at McGill University, Faculty of Medicine, Montreal, Canada.

References

- 1.Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. J Academic Medicine. 2007;82(3):226–30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Izadnegahdar R, Correia S, Ohata B, Kittler A, Kuile ST, Vaillancourt S, Saba N, Brewer TF. Global Health in Canadian Medical Education: Current Practices and Opportunities. J Academic Medicine. 2008:83. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816095cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowell J, Merrylees N. Electives: Isn't it time for a change?. J. Medical Education. 2009;43:121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges [Feb 5, 2011];GQ Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: All Schools Summary Report: Final. 2010 https://www.aamc.org/download/140716/data/2010_gq_all_schools.pdf.

- 5.Miranda JJ, Yudkin JS, Willott C. International Health Electives: Four years of experience. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2005;3:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Medicine. 2012;87(2) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson KC, Slatnik MA, Pereira I, Cheung E, Xu K, Brewer TF. Are We There Yet? Preparing Canadian Medical Students for Global Health Electives. J Academic. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823e23d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torjesen K, Mandalakas A, Kahn R, Duncan B. International child health electives for paediatric residents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1297–302. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.12.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niemantsverdriet S, van der Vleuten CPM, Majoor GD, Scherpbier AJJA. An explorative study into learning on international traineeships: experiential learning processes dominate. Med Educ. 2005;39:1236–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.A Report of the Global Health Resource Group of the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada. Towards a medical education relevant to all: the case for global health in medical education. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N, Chanda MY, Nehme J, Hulme J, Li A, Faridi N, Brewer TF. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Medical Education. 2010:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. Mar. 2009;84(3):320–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181970a37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staton DM. Proposal to Residency Review Committee for Pediatrics for Competencies in Global Health: American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on International Child Health. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chase JA, Evert J, editors. Global Health Training in Graduate Medical Education: A Guidebook. 2nd ed. Global Health Education Consortium; San Francisco: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suchdev PS, Shah A, Derby KS, Hall L, Shubert C, Pak-Gorstein S, Howard C, Wagner S, Anspacher M, Staton D, O'Callahan C, Herran M, Arnold L, Stewart CC, Kamat D, Batra M, Gutman J. A proposed model curriculum in global child health for pediatric residents. Acad Pediatr. May. 2012;12(3):229–37. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valani R, Sriharan A, Scolnik D. Integrating CanMEDS competencies into global health electives: an innovative elective program. CJEM. 2011;13(1):34–39. doi: 10.2310/8000.2011.100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishigori H, Otani T, Plint S, Uchino M, Ban N. I came, I saw, I reflected: A qualitative study into learning outcomes of international electives for Japanese and British medical students. Medical teacher. 2009;31:e196–e201. doi: 10.1080/01421590802516764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federico SG, Zachar PA, Oravec CM, Mandler T, Goldson E, Brown J. A Successful International Child Health Elective The University of Colorado Department of Pediatrics’ Experience. Arch Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:191–196. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vora N, Chang M, Pandya H, Hasham A, Lazarus C. A student-initiated and student- facilitated international health elective for preclinical medical students. Medical Education Online. 2010;15:4896. doi: 10.3402/meo.v15i0.4896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverberg D, Wellner R, Arora S, Newell P, Ozao J, Sarpel U, Torrina P, Wolfeld M, Divino C, Schwartz M, Silver L, Marin M. Establishing an International Training Program for Surgical Residents. Journal of Surgical Education. 2007;64(3):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imperato PJ. A third world international health elective for US medical students. The 25-year experience of the state university of New York, downstate medical center. J. of Community Health. 2004;29(5):337–73. doi: 10.1023/b:johe.0000038652.65641.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Disston AR, Martinez-Diaz GJ, Raju S, Rosales M, Berry WC, Coughlin RR. The International Orthopaedic Health Elective at the University of California at San Francisco: The Eight-Year Experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2999–3004. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunger E, Duke PS. The evolution of integration: Innovations in clinical skills and ethics in first year medicine. Med Teach. 2012;34(6):e452–8. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howe A, Barrett A, Leinster S. How medical students demonstrate their professionalism when reflecting on experience. J Med Education. 2009;43(10):942–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes D, Zayas LE, Koyfman A. Student Objectives and Learning Experiences in a Global Health Elective. Journal of community health. 2012:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9547-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McIntosh M, et al. The Curriculum Development Process for an International Emergency Medicine Rotation. Teaching and learning in medicine 24. 1(2012):71–80. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2012.641491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawatsky AP, et al. Eight Years of the Mayo International Health Program: What an International Elective Adds to Resident Education. Mayo Clinic proceedings 85. 8(2010):734–41. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]