Abstract

Nanomaterials are highly dynamic in biological and environmental media. A critical need for advancing environmental health and safety research for nanomaterials is to identify commonly occurring physical and chemical transformations affecting nanomaterial properties and toxicity. Silver nanoparticles, one of the most ecotoxic and well-studied nanomaterials, readily sulfidize in the environment. Here, we show that very low degrees of sulfidation (0.019 S/Ag mass ratio) universally and significantly decreases the toxicity of silver nanoparticles to four diverse types of aquatic and terrestrial eukaryotic organisms. Toxicity reduction is primarily associated with a decrease in Ag+ availability after sulfidation due to the lower solubility of Ag2S relative to elemental Ag (Ag(0)). We also show that chloride in exposure media determines silver nanoparticle toxicity by controlling the speciation of Ag. These results highlight the need to consider environmental transformation of NPs in assessing their toxicity to accurately portray their potential environmental risks.

Keywords: Nanotoxicity, Aquatic toxicity, Silver nanoparticles, nanomaterial transformations, sulfidation, chloride, risk assessment, risk reduction

The need to assess the risks of “real” nanomaterials, i.e. those present in products and with modified or “aged” forms of the materials that are expected in the environment has recently been stressed.1, 2 This is because physical, chemical, and biological transformations of many nanomaterials (e.g. dissolution to release toxic metal ions,3, 4 oxidation and reduction,5, 6 adsorption of biomacromolecules7 or natural organic matter8, 9 can affect the properties and toxicity of the materials.10 For example, carbon nanomaterials can be partially oxidized in vivo11 or by exposure to sunlight.12 Carbon nanotubes that have been partially oxidized by peroxidases induce much less pulmonary inflammation than pristine nanotubes.13 Despite this growing body of knowledge about nanomaterial transformations in environmental and biological media, a great majority of toxicity testing still utilizes as manufactured or pristine nanomaterials.3, 14, 15

Similar trends are observed for assessment of silver nanoparticle (AgNP) toxicity. Most recent studies,16–31 have used pristine AgNPs which these organisms are not likely to encounter. Pristine particles are used in order to carefully assess the effect of intrinsic particle properties on toxicity (particle size32, shape21 and the nature of the surfactant30). However little has been done to assess the effect of environmental constituents on particle properties even though such interactions will tend to decrease surface energy, potentially affecting particle behavior and toxicity.

AgNPs were found to readily transform to Ag2S or AgCl, depending on the environment.33–37 Elemental silver in the AgNPs is oxidized to Ag+, which then can readily react with inorganic sulfide to form Ag2S NPs or core shell Ag:Ag2S particles.34, 35, 38 Such nanoparticles are commonly found in wastewater treatment biosolids and in samples taken from pilot studies using simulated treatment.39, 40 In another study, AgNPs were shown to be partly sulfidized in freshwater mesocosms simulating an emergent wetland type of environment after 18 months of aging.37 Unfortunately, little has been done to understand the toxicity of the resulting sulfidized nanoparticles. Two studies demonstrated that toxicity of AgNPs towards nitrifying bacteria41, 42 and E. coli43 is reduced by sulfidation. The ability of sulfidation to decrease the toxicity of pristine AgNPs on more complex organisms has yet to be evaluated. Also not well tested is the effect of AgNP sulfidation on particle aggregation state and the effect of aggregation state on dissolution, and ultimately on toxicity.

We address these issues in the present study by synthesizing pristine and sulfidized AgNPs, carefully characterizing them, and then testing these transformed AgNPs in toxicological assays while simultaneously testing their behavior under media conditions identical to those found in the toxicology experiments. Our main objective was to test the hypothesis that sulfidation of AgNPs reduces their toxicity to a diverse range of organisms (i.e. vertebrates, invertebrates, plants). We found that even partial sulfidation of AgNPs dramatically reduces their toxicity and that interaction between the AgNPs and chloride in the exposure medium strongly affected the speciation of Ag in solution and therefore its toxicity. It is possible that discrepancies in reported toxicity (e.g., silver ENMs cause greater toxicity than silver ions in some studies but not in others) are due to differences24, 44 in Ag-medium specific interactions that are unfortunately usually poorly characterized. These results highlight the importance of considering both the environmental transformation of nanoparticles and chemical interactions with media in assessing their toxicity in order to accurately portray their potential toxicity risks.

Effect of sulfidation on toxicity

Four organisms (Zebra Fish Embryos, Killifish Embryos, C. elegans and Duckweed) from different trophic levels were exposed to pristine Ag NPs and to Ag NPs that had been sulfidized to three different levels to determine if Ag NP sulfidation that will occur in the environment would affect their toxicity. Sulfidation of the AgNPs reduced their toxicity to all organisms tested (Figure 1). The effect of sulfidation on toxicity was most pronounced in the low ionic strength exposure media (e.g. DI water, see Table 1 in Methods). There were species-specific differences in the magnitude of the effect of sulfidation. For example, sulfidation increased the EC50 and LC50 of the AgNPs for duckweed and killifish embryos, respectively, by up to an order of magnitude, whereas it increased the LC50 for C. elegans by a factor of 5, and only by 14% for zebrafish (Figure 1). These differences are likely due to the different sensitivities of the organisms to Ag ion, and potentially to differences in the exposure route that the assay exploits. In lethality tests with L1 C. elegans larvae in the low ionic strength medium (EPA medium) sulfidation of particles also resulted in increasing protection against mortality (Figure 2). This considerable reduction in toxicity was observed in most species at very low levels of sulfidation of the AgNPs (S/Ag=0.019) even though ~97% of the Ag in the AgNPs remains unsulfidized.35 Higher levels of sulfidation (S/Ag ratio of 0.432) further decreased the toxicity of the particles (Figure 1). Because AgNPs in many environments will be largely sulfidized39 or will rapidly become sulfidized,35, 38 these results highlight the need to understand how such a transformation affects NP behavior and toxicity.1, 34

Figure 1.

LC50 and EC50 responses of zebrafish embryos, killifish embryos, C. elegans, and Duckweed to the presence of pristine and sulfidized silver nanoparticles. As sulfidation of the silver particles (S/Ag mass ratio) increases along the y-axis all organisms are less sensitive to the particles. Values indicated with > in front exceeded those tested concentrations in these experiments. Exposures at relatively higher ionic strengths are shown in red whereas blue indicates relatively lower values.

Table 1.

Organisms and properties of the medium types used in this study

| Medium Type |

Organism(s) | Monovalent ion [mM] |

Divalention [mM] |

Ionic Strength [mM] |

pH | Conductivity [mS] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DI water | Zebrafish embryo Killifish embryo | - | - | - | - | - |

| EPA medium | C. elegans | 1.2 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 7.7 | 3.6 |

| Hutner’s medium | Duckweed | 6.0 | 3.0 | 27.0 | 5.0 | 1.9 |

| Hutner’s + 1.75‰ ASW | Duckweed | 34.7 | 9.1 | 66.0 | 5.1 | 2.4 |

| K+ medium | C. elegans | 104.0 | 6.0 | 83.0 | 5.7 | 83.0 |

| Embryo medium | Zebrafish embryo | 16.5 | 2.1 | 23.5 | 7.3 | 23.5 |

| 10 ‰ IO45 | Killifish embryo | 159.0 | 20.7 | 224.3 | 8.1 | 10.0 |

Complete information on media ion compositions is available in the supplemental information (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2.

Percent lethality measured for C. elegans in EPA water (low ionic strength and low Cl−). Mortality is defined as the number of unresponsive organisms over the total number of organisms. Note that there were no dead organisms observed for any concentration of Ag NPs (up to 30 ppm) in K+ medium (higher ionic strength and high Cl−). The chloride concentration in K+ medium decreases available Ag ion and therefore effects on the organisms.

Effect of media components on toxicity

The toxicity of AgNPs was also greatly impacted by the presence of various salts in the media used. In all cases, the toxicity of unsulfidized AgNPs in the higher ionic strength media was lower than in the lower ionic strength media. At the higher ionic strength, no toxicity was observed for exposure of killifish, zebrafish, or duckweed to either pristine or the sulfidized AgNPs at doses (e.g., >50 mg/kg), which are significantly higher than the concentrations expected in most environments.45 Only the C. elegans assay showed toxicity in the higher ionic strength media.

In this case, trends for the effect of sulfidation on toxicity were the same as those observed at low ionic strength, i.e. decreased toxicity upon sulfidation, but the measured LC50 was slightly higher in the higher ionic strength media (Figure 1). In lethality tests C. elegans L1 larvae were also far less susceptible to the lethal effects of the AgNPs in the higher ionic strength medium (K+ medium) compared to the lower ionic strength medium (EPA medium (Figure 2). This effect of ionic strength on observed toxicity to C. elegans is consistent with previous results using AgNPs ranging in size from 5 nm to 75 nm in diameter (measured by TEM) and with various coatings including gum arabic, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and citrate.30

Overall, sulfidation greatly decreased the toxicity of AgNPs to four different organisms, especially for lower ionic strength exposure media. Additionally, the presence of salts in the various media further decreased the observed toxicity for all of the organisms tested. Specific interactions between the AgNPs and released Ag+ and components of the media, and aggregation induced by increasing ionic strength can also impact the release of soluble Ag species and the observed toxicity, so each was explored further to determine the primary reasons for the decrease in toxicity due to sulfidation and salts in the exposure media.

Effect of dissolved Ag ions on toxicity

The toxicity of silver ions to bacteria and to aquatic organisms is well documented,34 however there is conflicting data in the literature regarding the mechanisms of toxicity from exposure to AgNPs. Some evidence indicates that there is a nanoparticle-specific effect,24, 44 whereas other evidence suggests that toxicity is derived primarily from the release of Ag+ ions.4, 24 Nanoparticle-specific effects may result from exogenous or endogenous production of ROS (e.g., superoxide or hydroxyl radicals) which induces oxidative stress32, 44–46 or they may result from locally high concentrations of dissolved Ag species in the vicinity of the AgNPs compared to the average concentration in solution.43 However, the observed toxicity may also correlate with the bulk concentration of soluble Ag species formed, i.e. no particle effect. These dissolved Ag species can react with sulfur and phosphorus groups in cellular components (e.g., proteins) leading to the observed toxicity.47, 48 Here, we carefully evaluate the correlation between release of soluble Ag species and the observed toxicity to determine the presence or absence of a nanoparticle-specific effect on toxicity across the organisms tested here.

To determine if the observed toxicity correlated with release of soluble Ag species the concentration of soluble Ag species was measured in each exposure medium that had been amended with AgNPs or the sulfidized AgNPs (0.019 S/Ag ratio) (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). In all cases the partly sulfidized materials released less soluble silver species over 48 and 120 hr in the exposure media. The Ag2S formed on the AgNP surfaces, representing only about 3 mol% of the total silver added, prevents silver from being oxidized and released from the nanoparticles.35

Figure 3.

Effects of sulfidation and media composition on availability of Ag+ and aggregation of the Ag-NPs. The dissolution of initial and 0.019 S:Ag particles was measured in six media types and DI water over 120 hr. In all cases sulfidation decreased the amount of silver ion in solution. Increases in chloride concentration (blue bars) increased aggregation (green bars; calculated from data in Figure S1) and affected the amount of Ag+ in solution (red bars). The same trends were observed after 48 hr in all media types (Supplementary Figure 1).

Significant differences in soluble Ag species concentration were observed between low ionic strength media (e.g., DI water and Hutner’s medium) and higher ionic strength media (IO and Hutner’s medium + ASW). Among the salts present in the different media (Table 1), chloride is known to strongly react with Ag+ ions potentially forming quite insoluble AgCl(s) (Ksp=1.77 ×10−10)34 or soluble silver chloride species (AgClaq, AgCl2−, AgCl32− and AgCl43−), depending on the amount of chloride in solution. The measured concentrations of soluble Ag species are consistent with those calculated assuming that the Ag+ ion in solution is in equilibrium with the chloride ion present in the media (horizontal red bars in Figure 3). Therefore, the decrease in soluble Ag species concentration in media containing chloride compared with those without chloride (DI water and Hutner’s medium) is attributed to the formation of AgCl(s) precipitates.49

Decreases in silver ion concentrations, caused by the formation of a relatively insoluble Ag2S layer (Ksp=10−51) on the surface of the AgNPs and/or by the formation of AgCl(s), universally decreased the observed toxicity of the AgNPs to the organisms used in this study. The sulfidized AgNPs had lower dissolved Ag species and lower toxicity. The lowest toxicity was observed in the higher ionic strength media having the lowest dissolved Ag species concentrations (Embryo and Hutner’s + ASW). Conversely, the highest toxicity was observed for media with the highest dissolved Ag species (DI water, EPA medium, and Hutner’s medium). These data strongly suggest that, for the organisms tested here, toxicity resulting from exposure to AgNPs is largely due to the availability of dissolved Ag species. This suggestion is consistent with a recent report indicating that the toxicity of AgNPs to bacteria was attributed to the release of Ag+ ions.4 However, the presence of ions in the media can also cause aggregation of the AgNPs. This in turn can affect route of exposure and biouptake50 Therefore, the impact of Ag NP aggregation on the observed toxicity was assessed.

Effect of AgNP aggregation on toxicity

The cations present in the different exposure media can cause the Ag NPs to aggregate so the rate of aggregation of pristine PVP-coated Ag NPs and sulfidized PVP-coated AgNPs was measured in each exposure medium using dynamic light scattering. Measurements performed on the pristine AgNPs indicate that they had very low rates of aggregation for all media except the K+ medium and the IO medium (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). This finding is consistent with the fact that the K+ and IO media have chloride concentrations above the reported critical coagulation concentration (112 mM) for PVP coated Ag-NPs,51 whereas the other media do not. In contrast, the sulfidized AgNPs are aggregated to begin with (Supplementary Figure 3) and the degree of initial aggregation is dependent on the medium in which they are dispersed. Measured hydrodynamic diameters ranged from 60 nm to 250 nm. Several lines of evidence suggest that aggregation state had little effect on the observed toxicity, regardless of the organism or assay media tested. First, there was a reduction in toxicity of the pristine AgNPs in the embryo medium compared to DI water for the zebrafish assay even though there was no aggregation of the AgNPs in either medium. Thus, the reduction in zebrafish toxicity can be attributed solely to the decrease in the concentration of dissolved silver. Similarly, in the case of the duckweed, there was no aggregation of the particles in Hutner’s medium or Hutner’s plus 1.75‰ ASW; however there was a decrease in the observed toxicity and a decrease in dissolved Ag due to formation of AgCl(s). A second line of evidence suggesting the negligible effect of AgNP aggregation on toxicity is seen in the C. elegans data. Even though there was significant aggregation in the K+ medium compared to the EPA medium, there was relatively little difference in the measured LC50 values for the pristine AgNPs in these different media. Additionally, both the measured and thermodynamically expected dissolved silver concentration in solution are of the same order of magnitude for both media, suggesting again the important role of dissolved silver species rather than aggregation on toxicity.

This study demonstrates that even a low degree of sulfidation of the AgNPs dramatically decreases their toxicity to the four different organisms tested here, and in a wide range of exposure media. In all media examined in this study this decrease in toxicity is related to decreases in silver ions released from the AgNPs. AgNP aggregation state did not correlate with the toxicity results. Many engineered nanomaterials aside from Ag are made using soft metal cations (e.g. Zn, Cu, Cd). These metals all have a high affinity for inorganic sulfide and therefore will also readily sulfidize to form metal sulfide solids with relatively low aqueous solubilities.52 An initial release of unsulfidized nanomaterials made from these metal cations would likely have a deleterious effect in natural systems, but the long-term effects would be lessened through sulfidation of the nanoparticles. Based on this work, efforts should focus on determining the types, rates, and extents of transformation of nanoparticles in the environment. Testing protocols for assessing the toxicity of NPs made from soft metal cations that react with inorganic sulfide should include use of sulfidized (transformed) nanoparticles as this transformation can affect the measured LC50 or EC50 by orders of magnitude in some cases. For any nanomaterial that readily transforms in the environment or in vitro/vivo, the transformed material should be used or at least included in toxicity assessment. Assessments must also be conducted in media representative of the environment under consideration (e.g., brackish waters vs. freshwater) as the compositions of different media can impact the measured LC50 and EC50 through interaction with the nanoparticles or by determining the availability of toxic metal cations.

Methods

Particle Synthesis and Characterization

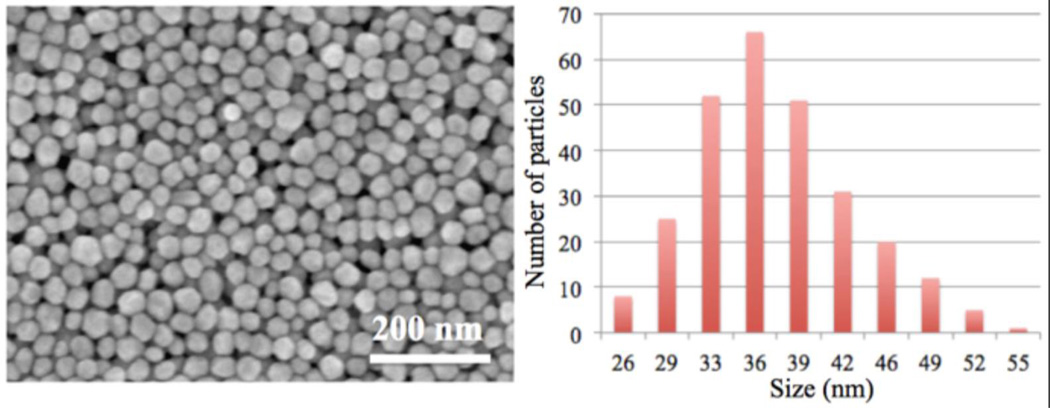

A batch of 37.3 ± 5.8 nm polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-coated AgNPs (Figure 4) along with partly sulfidized PVP-coated AgNPs (S:Ag=0.019, 0.073 and 0.432 by mass) were synthesized and characterized then distributed for immediate use. Details of the synthesis and complete characterization of these particles are given in Levard et al.35 Briefly, the relative abundances of Ag0/Ag2S were determined by X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. The Ag2S fraction represents 3, 10 and 64 mol% of total silver for the S/Ag ratios of 0.019, 0.073 and 0.432, respectively. The pristine and the sulfidized AgNPs were negatively charged at pH 7.5 (~15mV in 10 mM NaNO3).35 Before exposure to the different organisms, the particles were maintained in suspension to avoid irreversible aggregation that typically occurs upon drying. Particle suspensions were stored for as short a time as possible and in sealed bottled in the dark prior to characterization or toxicity testing.

Figure 4.

Non-sulfidized silver nanoparticles analyzed by SEM. Image analysis revealed that particles had an average size of 37.3 nm with a standard deviation of 5.8 nm. The size distribution determined from counting 260 particles on 2 separate SEM images.

The hydrodynamic diameter and aggregation rates of the particles were determined in each type of exposure medium by dynamic light scattering (ALV/CGS-3, Langen Germany). For all aggregation experiments, a 50 mg/L AgNP stock suspension was added to DI water and diluted to a concentration of 25 mg/L using double strength media to provide the same solution conditions as in the exposure study. The dynamic light scattering measurements were started immediately after dilution. Initial hydrodynamic diameters ranged from 40nm to 360nm depending on the composition of the medium (Supplementary Figure 2). Aggregation rates were approximated from the initial slopes of hydrodynamic diameter vs. time measurements.

The concentration of dissolved Ag was measured in each type of medium for the pristine AgNPs and for those sulfidized at a S/Ag ratio of 0.019 (the lowest used). Even though toxicity testing used AgNPs that had been sulfidized to varying degrees, the greatest effect of sulfidation on toxicity was observed for the pristine AgNPs compared to those sulfidized at the lowest S/Ag ratio. Given the limited amount of AgNPs only these particles could be used to assess the effect of sulfidation and composition of each medium on dissolved Ag species. Either pristine AgNPs or sulfidized AgNPs were added to media to a concentration between 144 to 221 ppm. These concentrations were similar to or higher than the doses used in the toxicity testing, but they were needed to be able to measure the dissolved Ag released from the samples in each media. The particles were separated from the supernatant after 48 hr and 120 hr by filtering using Amicon Ultra 3kDa MWCO centrifuge tubes. Supernatant silver ion concentrations were measured using an Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometer (ICP; TJA IRIS Advantage/ 1000 Radial ICAP Spectrometer) after acid digestion with concentrated HNO3. Duplicates of each sample were measured, with ion concentrations normalized by initial particle concentrations.

Organisms and Media

Four model organisms were selected for this study: two species of fish, Danio rerio (zebrafish) and Fundulus heteroclitus (killifish); the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans; and the aquatic plant Lemna minuta (least duckweed). These organisms were selected to provide a diverse set of organisms and routes of uptake for NPs and Ag ions. Six common exposure media and DI water were used. All media were prepared using high purity chemicals and deionized water, with the exception of the salt blend, Instant Ocean (IO, Foster & Smith, Rhinelander, WI, USA) which was diluted to ten parts per thousand (10 ‰ on a mass per mass basis) with deionized water. Table 1 lists the organisms and six exposure media types used, and compares their monovalent ion concentration, divalent ion concentration, and ionic strength. The exact composition of 10 ‰ IO was estimated from an elemental composition analysis performed by ICP.53 Artificial seawater (ASW) was prepared according to Kester et al.54

Toxicology

In all assays PVP-only controls that ranged between 20 and 200 mg/L, depending on the organism and particle concentrations used, consistently showed no adverse effect. These PVP concentrations are much higher than the concentration of PVP that would result if all of the PVP adsorbed to the particle surfaces were to desorb in the experiment. However, adsorption of PVP to the particles is essentially irreversible over the time scales used in these studies.55

Zebra Fish Embryos (Danio rerio)

Adult Tropical 5D zebrafish were housed and reared at Oregon State University Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory. Adult zebrafish were group-spawned and embryos were collected and staged according to Kimmel et al.56 A working AgNP (both unsulfidized and sulfidized) stock solution of 100 µg/mL (ppm) was made by diluting the AgNPs in reverse osmosis (RO) water or embryo medium for each sample. Samples were then placed into a water bath sonicator for 3 minutes. To increase bioavailability, the embryonic chorion was removed at four hr post fertilization (hpf).57 Embryos were rested for 30 minutes prior to exposures in individual wells of a 96-well plate with 100 µl of prepared AgNP suspension. Exposure plates were sealed and wrapped with aluminum foil to prevent evaporation and minimize light exposure. Embryos were exposed to five concentrations of silver nanoparticles with the highest concentration at 50 ppm and the lowest concentration at 0.08 ppm. An equivalent amount of DI water or embryo medium without AgNPs was added as a negative control (n=16, two replicates). Trimethyltin chloride (5 µM) was used as a positive control to confirm the embryonic responsiveness. The static nanoparticle exposure continued until 120 hpf. At 120 hpf, embryos were assessed for mortality.57

Killifish Embryos (Fundulus heteroclitus)

Adult killifish were collected from King’s Creek, VA, USA (37° 18’16.2”N, 76° 24’58.9”W). Killifish were kept in 30 or 40 L tanks in a flow-through system. Water was maintained at 25°C and 15‰ IO (made from diluted Instant Ocean, Foster & Smith, Rhinelander, WI, USA) on a 14:10 hr light:dark cycle. Fish were fed pelleted food (Aquamax© Fingerling Starter 300, PMI Nutritional International, LLC, Brentwood, MO, USA) ad libidum. Embryos were obtained for experiments by manual spawning and fertilization. At least one hr following fertilization, embryos were rinsed in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide followed by 3 washes in 20‰ ASW.

Embryos were screened for normal development at the 4–8 cell stage and immediately dosed in 0.2 mL dosing solution/embryo in 96-well plates with an n=24 for each concentration. 1000 ppm stock AgNP suspensions were sonicated for 15 seconds in a bath sonicator. Embryos were exposed to four concentrations ranging from 1 to 200 ppm Ag for each of the four AgNP solutions in DI water and in 10 ‰ ASW. Experiments were screened for mortality, which is defined as cessation of heartbeat at 24 hr and 48 hr post dosing.

C. elegans (Caenorhabditis elegans)

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans was tested for acute lethality and growth inhibitory effects of the pristine AgNPs and sulfidized AgNPs in high- and low-ionic strength C. elegans liquid media (K+ medium and EPA water, respectively). One lethality and three growth assays were performed. Exposure concentrations were based on previous AgNP toxicity studies.23, 30 Age-synchronized L1 larval stage C. elegans of the wild-type N2 (Bristol) strain were obtained by overnight hatch of purified egg preparations as previously described.23 To test lethality, L1 cultures were exposed in 96-well plates, without food, to pristine AgNPs and sulfidized AgNPs. After 24 h, nematodes were probed for movement after prodding with a worm pick for 15 s, and scored as alive (responsive) or dead (unresponsive).

For growth assays, age-synchronized L1 larvae were obtained as described above. Stock solutions were sonicated for 15 s in a bath sonicator and then diluted to target exposure concentrations in EPA and K+ medium, with the volume of stock solution balanced by the same volume of double ionic strength medium to preserve medium composition. Nematodes were fed UVC-inactivated uvrA (DNA damage repair-deficient) bacteria23 daily during the exposure, as described previously.30 Nematode size (EXT, extinction coefficient) was measured using a COPAS Biosort at 24, 48, and 96 hr after the exposure began, as previously described;30 control nematodes progress from the L1 to the young adult stage during this time. Extinction (EXT) values obtained from the Biosort for each aspiration time were graphed, generating an approximately linear relationship. Graphical interpolations from dose-response relationships were used to calculate EC50 values for each treatment.

Duckweed (Lemna minuta)

Samples of the floating aquatic plants, Lemna minuta were collected from the coastal plain of North Carolina, and were grown in pure-culture using half-strength Hutner’s medium58 under cool fluorescent lights at 100 µEinsteins m−2 s−1. For experimental treatments, L. minuta were grown in 10 mL of either Hutner’s medium (a lower ionic strength medium), or a modified Hutner’s medium made in 1.75‰ ASW.54 Experiments were conducted in 6 cm × 1.5 cm petri dishes (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, USA). Plants were exposed to 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 mg Ag L−1 for each particle type for 7 days. Each treatment consisted of 4 replicates, each starting with 5 fronds of L. minuta, where one frond is one individual leaf. Growth suppression was measured by dry weight relative to controls. At low concentrations of added AgNPs, a slight stimulation of growth was seen (i.e., hormesis), and so data were fit by using a linear logistic regression approach29 which accounts for subtoxic stimulus when calculating effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under NSF Cooperative Agreement EF- 0830093, Center for the Environmental Implications of NanoTechnology (CEINT), and EPA’s Science to Achieve Results (STAR) program (RD834574), Transatlantic Initiative for Nanotechnology and the Environment (TINE). Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or the EPA. This work has not been subjected to EPA review and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supporting Information Available: Detailed composition of each medium, ion release, aggregation rate in each medium at t=48h, aggregation of APVP-coated Ag NPs in each medium as measured by DLS. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Lowry GV, Gregory KB, Apte SC, Lead JR. Transformations of Nanomaterials in the Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(13):6893–6899. doi: 10.1021/es300839e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCall MJ. Environmental, health and safety issues: nanoparticles in the real world. Nature Nanotechnology. 2011;6(10):613–614. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puzyn T, Rasulev B, Gajewicz A, Hu XK, Dasari TP, Michalkova A, Hwang HM, Toropov A, Leszczynska D, Leszczynski J. Using nano-QSAR to predict the cytotoxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles. Nature Nanotechnology. 2011;6(3):175–178. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiu Z-m, Zhang Q-b, Puppala HL, Colvin VL, Alvarez PJJ. Negligible Particle-Specific Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles. Nano Letters. 2012;12(8):4271–4275. doi: 10.1021/nl301934w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phenrat T, Long TC, Lowry GV, Veronesi B. Partial oxidation ("aging") and surface modification decrease the toxicity of nanosized zerovalent iron. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43(1):195–200. doi: 10.1021/es801955n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metz KM, Mangham AN, Bierman MJ, Jin S, Hamers RJ, Pedersen JA. Engineered Nanomaterial Transformation under Oxidative Environmental Conditions: Development of an in vitro Biomimetic Assay. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43(5):1598–1604. doi: 10.1021/es802217y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walczyk D, Bombelli FB, Monopoli MP, Lynch I, Dawson KA. What the cell "sees" in bionanoscience. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132(16):5761–5768. doi: 10.1021/ja910675v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabrega J, Luoma SN, Tyler CR, Galloway TS, Lead JR. Silver nanoparticles: Behaviour and effects in the aquatic environment. Environ. Int. 2011;37(2):517–531. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang S, Bar-Ilan O, Peterson R, Heideman W, Hamers R, Pedersen JA. Influence of Humic Acid on Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticle Toxicity to Developing Zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013 doi: 10.1021/es3047334. ASAP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A Research Strategy for Environmental, Health, and Safety Aspects of Engineered Nanomaterials. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. Committee to Develop a Research Strategy for Environmental, H.; Nanomaterials, a. S.A.o.E. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen BL, Kichambare PD, Gou P, Vlasova, Kapralov AA, Konduru N, Kagan VE, Star A. Biodegradation of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes through Enzymatic Catalysis. Nano Letters. 2008;8(11):3899–3903. doi: 10.1021/nl802315h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou WC, Jafvert CT. Photochemical Transformation of Aqueous C-60 Clusters in Sunlight. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43(2):362–367. doi: 10.1021/es802465z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kagan VE, Konduru NV, Feng WH, Allen BL, Conroy J, Volkov Y, Vlasova, Belikova NA, Yanamala N, Kapralov A, Tyurina YY, Shi JW, Kisin ER, Murray AR, Franks J, Stolz D, Gou PP, Klein-Seetharaman J, Fadeel B, Star A, Shvedova AA. Carbon nanotubes degraded by neutrophil myeloperoxidase induce less pulmonary inflammation. Nature Nanotechnology. 2010;5(5):354–359. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priester JH, Ge Y, Mielke RE, Horst AM, Moritz SC, Espinosa K, Gelb J, Walker SL, Nisbet RM, An YJ, Schimel JP, Palmer RG, Hernandez-Viezcas JA, Zhao LJ, Gardea-Torresdey JL, Holden PA. Soybean susceptibility to manufactured nanomaterials with evidence for food quality and soil fertility interruption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(37):E2451–E2456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205431109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia XR, Monteiro-Riviere NA, Riviere JE. An index for characterization of nanomaterials in biological systems. Nature Nanotechnology. 2010;5(9):671–675. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asharani PV, Wu YL, Gong Z, Valiyaveettil S. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles in zebrafish models. Nanotechnology. 2008;19(25):255102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/25/255102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi O, Deng KK, Kim NJ, Ross L, Surampalli RY, Hu ZQ. The inhibitory effects of silver nanoparticles, silver ions, and silver chloride colloids on microbial growth. Water Research. 2008;42(12):3066–3074. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dror-Ehre A, Mamane H, Belenkova T, Markovich G, Adin A. Silver nanoparticle-E. coli colloidal interaction in water and effect on E-coli survival. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2009;339(2):521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabrega J, Fawcett SR, Renshaw JC, Lead JR. Silver nanoparticle impact on bacterial growth: effect of pH, Concentration, and organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43(19):7285–7290. doi: 10.1021/es803259g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabrega J, Renshaw JC, Lead JR. Interactions of Silver Nanoparticles with Pseudomonas putida Biofilms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43(23):9004–9009. doi: 10.1021/es901706j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George S, Lin SJ, Jo ZX, Thomas CR, Li LJ, Mecklenburg M, Meng H, Wang X, Zhang HY, Xia T, Hohman JN, Lin S, Zink JI, Weiss PS, Nel AE. Surface Defects on Plate-Shaped Silver Nanoparticles Contribute to Its Hazard Potential in a Fish Gill Cell Line and Zebrafish Embryos. Acs Nano. 2012;6(5):3745–3759. doi: 10.1021/nn204671v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gubbins EJ, Batty LC, Lead JR. Phytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles to Lemna minor L. Environmental Pollution. 2011;159(6):1551–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer JN, Lord CA, Yang XYY, Turner EA, Badireddy AR, Marinakos SM, Chilkoti A, Wiesner MR, Auffan M. Intracellular uptake and associated toxicity of silver nanoparticles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aquatic Toxicology. 2010;100(2):140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navarro E, Piccapietra F, Wagner B, Marconi F, Kaegi R, Odzak N, Sigg L, Behra R. Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42(23):8959–8964. doi: 10.1021/es801785m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peulen TO, Wilkinson KJ. Diffusion of Nanoparticles in a Biofilm. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45(8):3367–3373. doi: 10.1021/es103450g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roh J, Sim S, Yi J, Park K, Chung K, Ryu D, Choi J. Ecotoxicity of silver nanoparticles on the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans using functional ecotoxicogenomics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43(10):3933–3940. doi: 10.1021/es803477u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sondi I, Salopek-Sondi B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E-coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2004;275(1):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sotiriou GA, Pratsinis SE. Antibacterial Activity of Nanosilver Ions and Particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44(14):5649–5654. doi: 10.1021/es101072s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Zande M, Vandebriel RJ, Van Doren E, Kramer E, Rivera ZH, Serrano-Rojero CS, Gremmer ER, Mast J, Peters RJB, Hollman PCH, Hendriksen PJM, Marvin HJP, Peijnenburg A, Bouwmeester H. Distribution, Elimination, and Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles and Silver Ions in Rats after 28-Day Oral Exposure. Acs Nano. 2012;6(8):7427–7442. doi: 10.1021/nn302649p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang XY, Gondikas AP, Marinakos SM, Auffan M, Liu J, Hsu-Kim H, Meyer JN. Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticle Toxicity Is Dependent on Dissolved Silver and Surface Coating in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(2):1119–1127. doi: 10.1021/es202417t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yin LY, Cheng YW, Espinasse B, Colman BP, Auffan M, Wiesner M, Rose J, Liu J, Bernhardt ES. More than the Ions: The Effects of Silver Nanoparticles on Lolium multiflorum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45(6):2360–2367. doi: 10.1021/es103995x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi O, Hu ZQ. Size dependent and reactive oxygen species related nanosilver toxicity to nitrifying bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42(12):4583–4588. doi: 10.1021/es703238h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Badawy AM, Luxton TP, Silva RG, Scheckel KG, Suidan MT, Tolaymat TM. Impact of Environmental Conditions (pH, Ionic Strength, and Electrolyte Type) on the Surface Charge and Aggregation of Silver Nanoparticles Suspensions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44(4):1260–1266. doi: 10.1021/es902240k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levard C, Hotze EM, Lowry GV, Brown GE. Environmental Transformations of Silver Nanoparticles: Impact on Stability and Toxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(13):6900–6914. doi: 10.1021/es2037405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levard C, Reinsch BC, Michel FM, Oumahi C, Lowry GV, Brown GEJ. Sulfidation Processes of PVP-Coated Silver Nanoparticles in Aqueous Solution: Impact on Dissolution Rate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45(12):5260–5266. doi: 10.1021/es2007758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu JY, Sonshine DA, Shervani S, Hurt RH. Controlled Release of Biologically Active Silver from Nanosilver Surfaces. Acs Nano. 2010;4(11):6903–6913. doi: 10.1021/nn102272n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowry GV, Espinasse BP, Badireddy AR, Richardson CJ, Reinsch BC, Bryant LD, Bone AJ, Deonarine A, Chae S, Therezien M, Colman BP, Hsu-Kim H, Bernhardt ES, Matson CW, Wiesner MR. Long-Term Transformation and Fate of Manufactured Ag Nanoparticles in a Simulated Large Scale Freshwater Emergent Wetland. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(13):7027–7036. doi: 10.1021/es204608d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Pennell KG, Hurt RH. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Nanosilver Oxysulfidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45(17):7345–7353. doi: 10.1021/es201539s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaegi R, Voegelin A, Sinnet B, Zuleeg S, Hagendorfer H, Burkhardt M, Siegrist H. Behavior of Metallic Silver Nanoparticles in a Pilot Wastewater Treatment Plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45(9):3902–3908. doi: 10.1021/es1041892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim B, Park CS, Murayama M, Hochella MF., Jr Discovery and characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles in final sewage sludge products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44(19):7509–7514. doi: 10.1021/es101565j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi O, Cleuenger TE, Deng BL, Surampalli RY, Ross L, Hu ZQ. Role of sulfide and ligand strength in controlling nanosilver toxicity. Water Research. 2009;43(7):1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi OK, Hu ZQ. Nitrification inhibition by silver nanoparticles. Water Science and Technology. 2009;59(9):1699–1702. doi: 10.2166/wst.2009.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinsch BC, Levard C, Li Z, Ma R, Wise A, Gregory KB, Brown GE, Jr, Lowry GV. Sulfidation of Silver Nanoparticles Decreases Escherichia coli Growth Inhibition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(13):6992–7000. doi: 10.1021/es203732x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hwang ET, Lee JH, Chae YJ, Kim YS, Kim BC, Sang B-I, Gu MB. Analysis of the toxic mode of action of silver nanoparticles using stress-specific bioluminescent bacteria. Small. 2008;4(6):746–750. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akdim B, Hussain S, Pachter R. A density functional theory study of oxygen adsorption at silver surfaces: Implications for nanotoxicity. Computational Science - ICCS 2008 . Proceedings 8th International Conference. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim JS, Kuk E, Yu KN, Kim J-H, Park SJ, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Park YK, Park YH, Hwang C-Y, Kim Y-K, Lee Y-S, Jeong DH, Cho M-H. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine-Nanotechnology Biology and Medicine. 2007;3(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bottero J-Y, Auffan M, Rose J, Mouneyrac C, Botta C, Labille J, Masion A, Thill A, Chaneac C. Manufactured metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles: Properties and perturbing mechanisms of their biological activity in ecosystems. Comptes Rendus Geoscience. 2011;343(2–3):168–176. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ratte HT. Bioaccumulation and toxicity of silver compounds: A review. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 1999;18(1):89–108. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Lenhart JJ, Walker HW. Dissolution-Accompanied Aggregation Kinetics of Silver Nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2010;26(22):16690–16698. doi: 10.1021/la101768n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho EC, Zhang Q, Xia YN. The effect of sedimentation and diffusion on cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles. Nature Nanotechnology. 2011;6(6):385–391. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huynh KA, Chen KL. Aggregation Kinetics of Citrate and Polyvinylpyrrolidone Coated Silver Nanoparticles in Monovalent and Divalent Electrolyte Solutions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45(13):5564–5571. doi: 10.1021/es200157h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma R, Levard Cm, Michel FM, Brown GE, Lowry GV. Sulfidation Mechanism for Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and the Effect of Sulfidation on Their Solubility. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47(6):2527–2534. doi: 10.1021/es3035347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Atkinson MJ, Bingman C. Elemental composition of commercial seasalts. Journal of Aquariculture and Aquatic Sciences. 1997;8(2):39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kester DR, Duedall IW, Connors DN, Pytkowicz RM. Preparation of artificial seawater. Limnology and Oceanography. 1967;12:176–179. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma R, Levard C, Marinakos SM, Cheng Y, Liu J, Michel FM, Brown GE, Lowry GV. Size-Controlled Dissolution of Organic-Coated Silver Nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(2):752–759. doi: 10.1021/es201686j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic-development of the zebrafish. Developmental Dynamics. 1995;203(3):253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Truong L, Saili KS, Miller JM, Hutchison JE, Tanguay RL. Persistent adult zebrafish behavioral deficits results from acute embryonic exposure to gold nanoparticles. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C-Toxicology & Pharmacology. 2012;155(2):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brain RA, Solomon KR. A protocol for conducting 7-day daily renewal tests with Lemna gibba. Nature Protocols. 2007;2(4):979–987. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.