Abstract

Neisseria meningitidis utilizes capsular polysaccharide, lipooligosaccharide (LOS) sialic acid, factor H binding protein (fHbp), and neisserial surface protein A (NspA) to regulate the alternative pathway (AP) of complement. Using meningococcal mutants that lacked all four of the above-mentioned molecules (quadruple mutants), we recently identified a role for PorB2 in attenuating the human AP; inhibition was mediated by human fH, a key downregulatory protein of the AP. Previous studies showed that fH downregulation of the AP via fHbp or NspA is specific for human fH. Here, we report that PorB2-expressing quadruple mutants also regulate the AP of baby rabbit and infant rat complement. Blocking a human fH binding region on PorB2 of the quadruple mutant of strain 4243 with a chimeric protein that comprised human fH domains 6 and 7 fused to murine IgG Fc enhanced AP-mediated baby rabbit C3 deposition, which provided evidence for an fH-dependent mechanism of nonhuman AP regulation by PorB2. Using isogenic mutants of strain H44/76 that differed only in their PorB molecules, we confirmed a role for PorB2 in resistance to killing by infant rat serum. The PorB2-expressing strain also caused higher levels of bacteremia in infant rats than its isogenic PorB3-expressing counterpart, thus providing a molecular basis for increased survival of PorB2 isolates in this model. These studies link PorB2 expression with infection of infant rats, which could inform the choice of meningococcal strains for use in animal models, and reveals, for the first time, that PorB2-expressing strains of N. meningitidis regulate the AP of baby rabbits and rats.

INTRODUCTION

Neisseria meningitidis is an important cause of bacterial meningitis worldwide (1, 2). The complement system contributes to innate immune defenses against this pathogen, and individuals with defects in the terminal complement components (C5 through C9) or in components of the alternative pathway (AP) are at an increased risk of meningococcal disease (3, 4). The AP is characterized by a positive-feedback loop that amplifies C3b deposition on microbial surfaces (5, 6). The AP works in concert with the classical pathway and plays an important role in maximizing the killing activity of select antibodies, including those directed against the vaccine antigen, factor H binding protein (fHbp) (7). Factor H (fH), a host complement control protein, plays a key role in limiting unwanted activation of the AP (8, 9) by assisting with factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b to iC3b (10, 11) and by irreversibly dissociating the AP C3 convertase (C3bBb) (12, 13).

N. meningitidis employs several distinct mechanisms to limit AP activation. Capsular polysaccharides elaborated by meningococci are important determinants of meningococcal serum resistance; group B and C capsules serve to inhibit the AP and limit C3 deposition on the bacterial surface (14, 15). Sialylation of lacto-N-neotetraose (LNT) lipooligosaccharide (LOS) inhibits the AP by enhancing the interactions of fH with C3 fragments bound to the bacterial surface (16). Meningococci also directly bind human fH through two surface-expressed molecules, fHbp (17) and neisserial surface protein A (NspA) (18), which both serve to limit C3 deposition and enhance resistance of the organism to complement-dependent killing. Recently, we identified a role for meningococcal PorB2 in fH-dependent regulation of the human AP (19). Thus, redundancy in mechanisms of protection against the AP appears to be a characteristic of virulent meningococci.

N. meningitidis causes natural infection only in humans, and there are no known animal reservoirs for this organism. Under experimental conditions, only certain strains can multiply in the bloodstream of wild-type (WT) infant rats after intraperitoneal (i.p.) challenge (20, 21). As an example, strain 4243, which belongs to the “hypervirulent” sequence type 11 (ST-11) lineage (22), causes bacteremia after i.p. challenge with ∼103 CFU (23), while strain H44/76, which belongs to the ST-32 complex, produces only transient bacteremia after challenge with 106 CFU (21, 24). The reasons for this discrepancy are not fully understood, but studies of meningococcal pathogenesis in vivo in WT infant rats have been biased toward selection of relatively few strains, such as 4243, that cause bacteremia.

Based on observations that the ability of N. meningitidis to evade the AP relied on binding of human fH to meningococcal ligands such as fHbp and NspA (25), we developed a human fH transgenic (Tg) rat (21). Introducing human fH into rats enhanced the ability of strain H44/76 to cause bacteremia (bacteremia observed after challenge doses with as few as 5 × 102 CFU) (21). Why strains such as 4243, but not H44/76, readily caused bacteremia in WT rats remained unclear. The aim of the present study was to characterize the interactions between diverse strains of N. meningitidis and nonhuman complement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Experiments with infant rats were performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute approved all protocols. Blood collection was performed under anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Characteristics of the WT strains that were used to derive the mutant strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Except where noted, N. meningitidis strains were grown on chocolate agar plates supplemented with IsoVitaleX equivalent at 37°C in an atmosphere enriched with 5% CO2. GC plates supplemented with IsoVitaleX equivalent were used for antibiotic selection. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations when indicated: 100 μg/ml kanamycin, 7 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 5 μg/ml erythromycin, 50 μg/ml spectinomycin, and 2 μg/ml tetracycline. Escherichia coli strains (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were cultured in Luria Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar. Antibiotics were used as needed at the following concentrations: 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 125 μg/ml ampicillin, and 7 μg/ml tetracycline.

TABLE 1.

Wild-type strains used in this study and their relevant characteristics

| N. meningitidis strain | Capsular serotype | PorB serotype (class) | PorA VR sequence typea | MLSTb | Country of origin (yr) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2594 (WUE2594) | A | 4 (PorB3) | 1-9 | ST-5 | Germany (1991) | 17, 26 |

| H44/76 | B | 15 (PorB3) | 1.7,16 | ST-32 | Norway (1976) | 27 |

| NZ98/254 | B | 4 (PorB3) | 1.4 | ST-41/44 | New Zealand (1990) | 28, 29 |

| C2120 | C | NT (PorB2) | 1.5,2 | ST-11 | Not known | 30 |

| W171 | W | NT (PorB2) | 1.10 | ST-11/CC-11 | USA | 31 |

| 4243 | C | 2a (PorB2) | 1.5,2 | ST-11 | USA | 32 |

| 2996 | B | 2b (PorB2) | 1.5-1,2-2 | Not known | UK (1980s) | 33 |

VR, variable region.

MLST, multilocus sequence typing; ST, sequence type; CC, clonal complex.

All mutant strains used in this study have been described previously (19). In brief, strains were rendered unencapsulated by interruption of mynB (group A capsule) or siaD (groups B, C, or W135 capsule) (18, 34). Insertional inactivation of lst (lst::kan) abrogated LOS sialylation of group B, C, and W135 isolates as previously described (18, 34). Group A strains do not sialylate their LOS unless CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-NANA) is added to the growth medium. fHbp and NspA expression was abrogated as previously described (fHbp::erm [17] and nspA::spc [18] strains, respectively). Mutants that lacked capsule, LOS sialic acid, fHbp, and NspA simultaneously are referred to as quadruple mutants. PorB allelic replacements in H44/76 fHbp nspA were made by replacing the entire H44/76 porB3 with either the porB3 of strain H44/76 or with the porB2 of strain 4243 as described previously (19). The PorB allelic exchanges contain complete gene replacements and uniformly express PorB at the high levels seen in WT strains (19).

Sera.

Baby rabbit complement was purchased from Cedarlane Laboratories. According to the manufacturer, baby rabbit complement was obtained from 3- to 4-week-old rabbits and was pooled into large lots. Pregnant Wistar rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Portage, MI), and infant rat pups were sacrificed at 8 to 9 days of age by cardiac puncture to prepare pooled complement as described for mice. To inactivate selectively the classical and lectin complement pathways and isolate the AP as the only active pathway, MgCl2 and EGTA (Mg-EGTA), both to a final concentration of 10 mM, were added to sera or complement sources as specified in the text.

Recombinant human fH/Fc fusion proteins.

fH domains 6 and 7 fused in-frame to the Fc fragment of murine IgG2a (fH67/Fc) and fH domains 18 to 20 fused to the Fc fragment of murine IgG2a (fH18–20/Fc) have both been described previously (19, 35). Chinese hamster ovary cells were transfected with the fH/Fc construct using Lipofectin (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and fH/Fc constructs were purified from culture supernatants after 48 h using a protein A-Sepharose column. The concentration of purified protein was determined by absorbance at 280 nm and with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce).

Flow cytometry.

Rabbit and rat C3 deposition on the bacterial surface was measured using flow cytometry, performed as described previously (36). For detection of C3, we used fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-guinea pig C3 and anti-mouse C3 (Cappel/MP Biomedical), respectively. In fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) and Western blotting experiments, we confirmed specificity and cross-reactivity of these antibodies with rabbit and rat C3, respectively (data not shown). These antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200 in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS)–0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 7.2.5; Tree Star, Inc.). Binding is shown as histogram tracings and quantified as a percentage of positive events (relative to a negative control that was gated to yield 5% of positive events).

In vitro survival of bacteria in rat serum.

Survival of N. meningitidis in a serum pool derived from 8- to 9-day-old WT Wistar rats (Charles River) was measured as described previously (21). Briefly, N. meningitidis was grown (37°C in 5% CO2) to early log phase in Mueller-Hinton broth (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) supplemented with 0.02 mM CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-NANA; Sigma) and 0.25% glucose. The bacteria were pelleted, washed, suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-BSA and added (∼400 CFU) to pooled infant rat serum (final concentration of 20 and 40%) in a 40-μl reaction mixture (total volume) in microtiter plates (Nunclon Δ Surface; ThermoFisher Scientific, Rochester, NY) with agitation. At time zero (T0) and at 60 min (T60), 10-μl aliquots from each well were dripped onto chocolate agar plates; the plates were tilted such that the inoculum spread in a line the width of the plates. Colony counts were ascertained using a ProtoCOL3 colony counter (Synbiosis, Frederick, MD) after incubation overnight. This method results in sufficient separation of individual CFU to count up to a density of approximately 250 CFU per aliquot. Percent survival was determined by comparing the CFU count at T60 to that at T0. We reported the mean and range of three independent replicates for each concentration of rat serum tested.

Infant rat bacteremia model.

N. meningitidis was grown to early log phase and prepared as described above for measurement of survival of bacteria in rat serum. Infant rats (Wistar or Wistar human fH Tg) aged 5 to 7 days were challenged i.p. with 100 μl of a suspension containing either 103 or 104 CFU of bacteria. Quantitative blood cultures were obtained at 6 h as previously described (21).

Statistical analyses.

Comparisons across multiple groups were carried out using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's posttest. All probability values reported, with the exception of the one-way ANOVA, are two-tailed. Comparisons of the proportions of rats that developed bacteremia at different time points or after infection with different mutant strains were performed using Fisher's exact test. Comparisons of the geometric mean CFU count of bacteria per ml of blood between two groups used a t test. The lower limit of detection for bacteremia in blood cultures was 5 CFU/ml; for calculations of geometric means, sterile blood cultures were assigned a value of half of the lower limit (i.e., <5 CFU/ml was assigned a value of 2.5 CFU/ml).

RESULTS

Meningococcal strains that express PorB2 regulate baby rabbit complement.

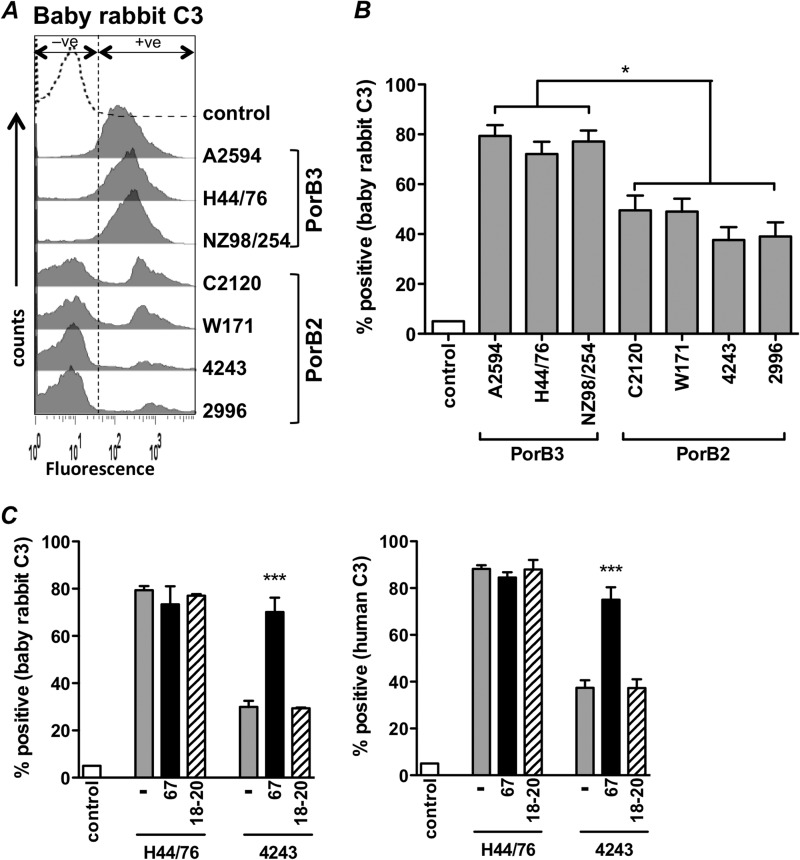

We recently reported that meningococcal strains expressing PorB2 regulate the human AP more effectively than strains expressing PorB3. Neither PorB2- nor PorB3-bearing strains were able to regulate the AP of adult rabbits or adult mice (19). Passive protection against bacteremia in infant rats (see, for example, references 23, 29, and 37 to 39) and bactericidal activity in serum complement from baby rabbits (see, for example, references 40 to 42) are often used to assess functional activity of naturally induced and vaccine-induced meningococcal antibodies. We next asked whether PorB2-expressing isolates also regulated the AP from infant nonhuman complement sources. As described previously (19), we used mutants that lacked capsule, LOS sialic acid, fHbp, and NspA (quadruple mutants) to eliminate any effect that these molecules may have in modulating C3 deposition. Quadruple mutants of seven diverse meningococcal strains were examined by FACS for deposition of baby rabbit C3 following incubation (30 min) with Mg-EGTA-treated baby rabbit complement. Treatment of complement with Mg-EGTA blocks activation by the classical and lectin pathways and thereby permits selective assessment of the AP. We noted a lower level of baby rabbit C3 deposition on the PorB2-expressing mutants than on PorB3-expressing mutants that were incubated with Mg-EGTA-treated baby rabbit complement (Fig. 1A and B). C3 deposition on PorB2-expressing strains displayed a bimodal distribution (Fig. 1A) indicative of two populations that may differentially regulate the AP. A similar bimodal pattern of C3 deposition was also observed in previous studies of these PorB2-expressing mutants with human complement (19). In that study, expression of PorB2 and C3 deposition were measured in parallel on the quadruple mutants of strains 4243 and 2996; C3 deposition showed a bimodal peak while expression of PorB2 was normally distributed and indicative of high-level expression on all strains (19). We concluded that bimodal deposition of human C3 on the PorB2-expressing strains was not a result of subpopulations of bacteria that express large and small amounts of PorB2. Similarly, here we measured expression of PorB2 on the quadruple mutants of strains 4243 and 2996 (we were not able to obtain antibodies that recognize PorB2 of C2120 or W71) grown as described for the C3 deposition assay and found that PorB2 was normally distributed and expressed in large amounts on both strains (data not shown). Thus, the variation in deposition of baby rabbit C3 on the PorB2-expressing strains, seen in the present study, was not likely a result of subpopulations of bacteria that express large and small amounts of PorB2. N. meningitidis contains >100 phase-variable/variably expressed genes, and we hypothesize that one or more of these could contribute to the observed C3 heterogeneity. The present data reveal for the first time that PorB2-expressing strains are specifically able to regulate the AP of baby rabbits.

FIG 1.

fH-dependent regulation of the AP of baby rabbit complement by PorB2-expressing N. meningitidis. (A and B) Decreased baby rabbit C3 fragment deposition on PorB2-expressing meningococci. Seven strains of N. meningitidis bacteria that lacked capsular polysaccharide, LOS sialic acid, fHbp, and NspA expression (quadruple mutants) were screened for surface C3 deposition when incubated with baby rabbit complement (20% [vol/vol]) containing 10 mM Mg-EGTA to block classical and lectin pathway activity and permit only AP activation. Histograms from a representative experiment are shown in panel A. The percentage of positive events for baby rabbit C3 fragment deposition relative to control organisms incubated with heat-inactivated serum (y axis) is shown in panel B (gated to include 5% of events as positive [+ve] in the control histogram). Each bar represents the mean (standard error of the mean) of seven independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's posttest for pairwise comparisons). −ve, negative. (C) Blocking the human fH binding site on PorB2 with human fH67/Fc enhances baby rabbit C3 deposition and provides evidence for function of rabbit fH on PorB2-expressing meningococci. Quadruple mutants of strain 4243 (PorB2) and H44/76 (PorB3; control) were incubated with either buffer alone (−), human fH67/Fc (67), or human fH18–20/Fc (18–20; negative-control protein) at concentrations of 10 μg/ml, followed by the addition of Mg-EGTA-treated baby rabbit complement (20% [vol/vol]) (left graph). C3 deposited on bacteria was detected by FACS. Similar experiments, performed with Mg-EGTA-treated human serum (right graph), demonstrate the functional interaction of human fH with PorB2 on the quadruple mutant of 4243. The y axis shows the percentage of positive events relative to controls treated with heat-inactivated complement. Bars show the means (standard error of the mean) of at least three separate experiments. ***, P < 0.001, compared to reaction mixtures containing buffer alone or fH18–20/Fc.

fH-PorB2 interactions regulate baby rabbit complement.

Regulation of the human AP by PorB2 required direct interaction of PorB2 with human fH (19); the interaction was weak, and binding of full-length human fH to PorB2 in the context of intact bacteria was detected by flow cytometry only in the presence of a cross-linker (19). In contrast, human FHL-1, an alternatively spliced variant of fH that contains fH domains 1 through 7 and that can inhibit the AP (43), and fH67/Fc, a recombinant chimeric protein that comprises human fH domains 6 and 7 (fH6–7) fused to mouse IgG Fc (Fc), both readily bound to PorB2 of strain 4243 (19). Therefore, we utilized recombinant fH67/Fc to block the proposed interaction between serum fH and/or FHL-1 (both molecules contain fH6–7) and PorB2 on the quadruple mutant of strain 4243 and to determine if an interaction between rabbit fH or FHL-1 and PorB2 accounted for regulation of the AP by serum from baby rabbits. We hypothesized that if fH67/Fc could out-compete fH and/or FHL-1 in infant rabbit serum for binding to PorB2 of 4243, then fH-dependent regulation of the AP would be lost, and C3 deposition would be enhanced. As shown in Fig. 1C, adding human fH67/Fc to Mg-EGTA-treated baby rabbit serum (Fig. 1C, left panel) augmented C3 deposition on the quadruple mutant of 4243, which demonstrated that blocking the human fH domain 6 and 7 binding region of PorB2 inhibits regulation of the rabbit AP by rabbit fH and/or FHL-1. Similarly, the addition of human fH67/Fc to Mg-EGTA-treated human complement (Fig. 1C, right panel) enhanced deposition of human C3 on the quadruple mutant of 4243 and validated the specificity of fH67/Fc in this assay. Neither baby rabbit nor human C3 deposition was affected by the presence of a control recombinant protein, fH18–20/Fc, that does not bind to meningococci (Fig. 1C, bars with oblique lines). The quadruple mutant of strain H44/76 (expresses PorB3) showed maximal rabbit and human C3 deposition when incubated with AP-specific serum alone, and, as expected, neither fH/Fc fragment further augmented C3 deposition on this mutant (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these data provide evidence that blocking the region of PorB2 that interacts with human fH domains 6 and 7 inhibits regulation of the baby rabbit AP and provides evidence for a role for rabbit fH and/or FHL-1 in PorB2-mediated regulation of the baby rabbit AP.

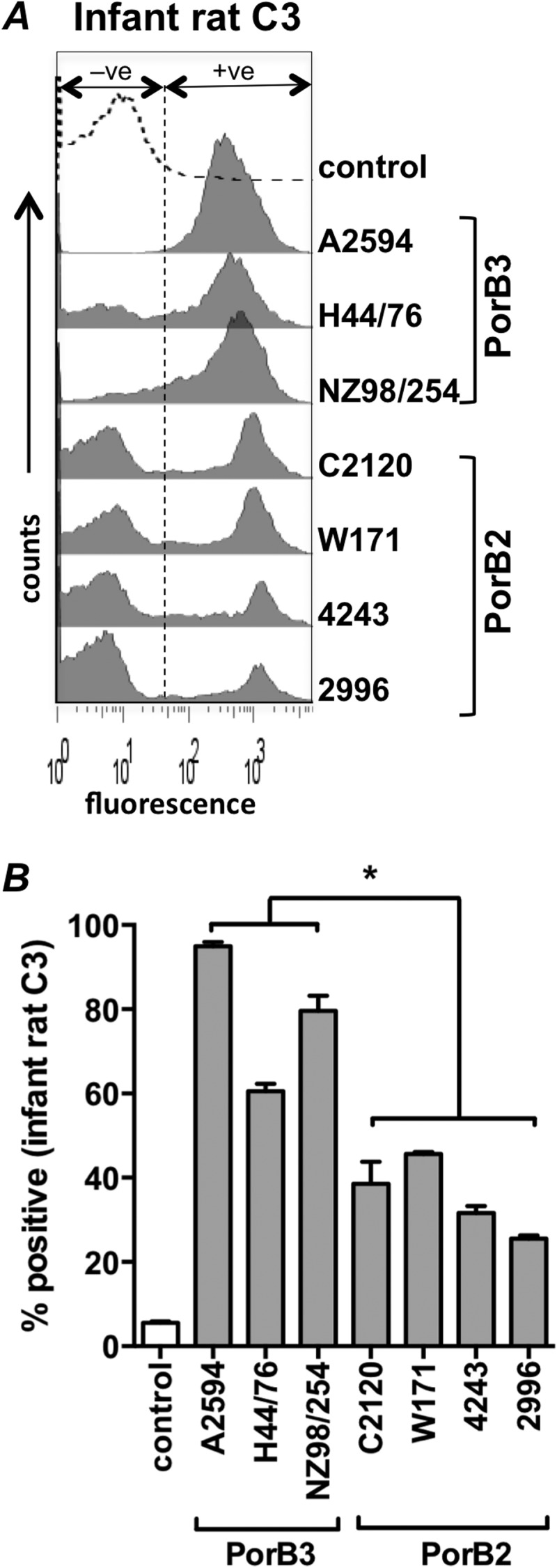

PorB2-expressing isolates regulate the AP of infant rats.

In WT infant rats, a relatively low inoculum (∼103 CFU) of N. meningitidis strain 4243 (PorB2) readily causes bacteremia (44), while strain H44/76 (PorB3) causes only transient bacteremia when given in high numbers (∼ 105 to 108 CFU) (20, 45, 46). To determine if PorB2-expressing strains can also regulate the AP of infant rats more efficiently than PorB3-expressing isolates, we measured rat C3 deposition by FACS. Consistent with the data above with baby rabbit serum, we observed significantly lower deposition of rat C3 on all the PorB2 strains tested than on the PorB3 strains following incubation with Mg-EGTA-treated infant rat serum (Fig. 2A and B).

FIG 2.

PorB2-expressing quadruple mutants inhibit the AP of infant rat complement. (A) Seven N. meningitidis quadruple mutants were incubated with 10% (vol/vol) Mg-EGTA-treated pooled serum from 8- or 9-day-old infant rats, and rat C3 fragments deposited on bacteria were measured by FACS. Representative histogram tracings (one of three reproducible repeats) are shown. (B) Data are from three separate experiments with infant rat serum, expressed as a percentage of positive events relative to heat-inactivated serum controls (gated to yield 5% of positive events [+ve] in the negative-control sample as shown). Each bar shows the mean (standard error of the mean). *, P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's posttest for pairwise comparisons).

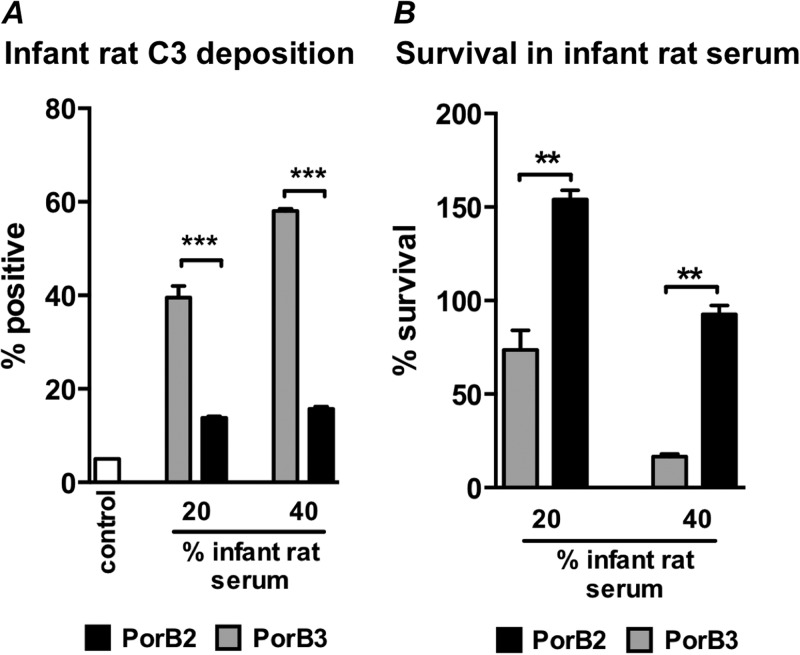

Encapsulated PorB2-expressing isogenic mutants regulate the rat AP and resist rat complement-mediated killing.

In order to specifically isolate the role of PorB2 in regulation of infant rat complement and to determine the role of PorB2 in survival in infant rat serum, we used isogenic strains of H44/76 fHbp nspA (encapsulated; LOS sialylated) that express either the native H44/76 PorB3 molecule (H44/76 fHbp nspA-PorB3) or the PorB2 molecule from 4243 (H44/76 fHbp nspA-PorB2) (19). H44/76 fHbp nspA-PorB2 showed less C3 deposition in Mg-EGTA-treated infant rat complement than H44/76 fHbp nspA that expressed its own PorB3 molecule (Fig. 3A). These data demonstrate PorB2-mediated regulation of the infant rat AP in an isogenic background and also demonstrate PorB2-associated AP regulation in the presence of capsule and LOS sialylation.

FIG 3.

Isogenic mutants of N. meningitidis that express PorB2 inhibit the rat AP and resist killing by infant serum. Isogenic mutant strains that differed only in their PorB molecule were created in the background of strain H44/76 fHbp nspA. Both mutants lacked fHbp and NspA but expressed capsular polysaccharide and LOS sialic acid. (A) PorB2 expression regulates infant rat AP. Bacteria were incubated with Mg-EGTA-treated infant rat serum (final concentration, either 20% or 40%), and deposited rat C3 was measured by FACS. Gray bars, H44/76 fHbp nspA expressing PorB3; black bars, H44/76 fHbp nspA expressing PorB2; open bars, control (no serum added). Each bar shows the percentage of positive events relative to the controls (set at 5%), and data represent the means (standard error of the mean) of three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (B) PorB2 expression increases resistance to bacteriolysis in infant rat serum. Serum bactericidal assays with the isogenic PorB mutants (described in panel A) were performed with infant rat serum. Each bar represents the mean (standard error of the mean) of three independent experiments. **, P ≤ 0.002.

The AP acting in isolation is insufficient to kill meningococci (15, 19); however, the AP is required for maximal classical pathway-initiated killing (7, 19, 47). We investigated the role of PorB2 in mediating resistance to infant rat serum (all complement pathways functional) by comparing the isogenic strain pair in a bactericidal assay. Concordant with the ability to better inhibit the rat AP, the H44/76 fHbp nspA-PorB2-expressing strain was able to resist killing by intact infant rat serum better than the corresponding strain bearing PorB3 (Fig. 3B). Thus, expression of PorB2 enhanced evasion of immune killing by infant rat sera.

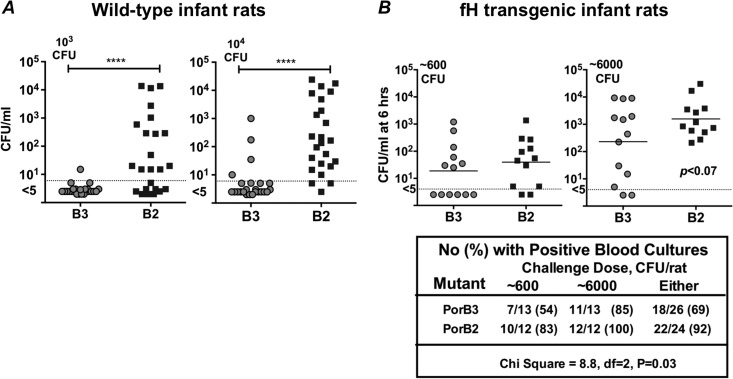

PorB2 expression enhances meningococcal invasiveness in the infant rat model.

To determine if PorB2 plays a role in invasion by meningococci in infant rats, we compared levels of bacteremia caused by encapsulated isogenic mutants of H44/76 fHbp nspA-PorB3 and H44/76 fHbp nspA-PorB2 in WT and human fH Tg infant rats. We first challenged WT infant rats with either 103 or 104 CFU of each of the mutant strains (Fig. 4A). At 6 h postinoculation, the PorB2-expressing mutant had achieved significantly higher levels of bacteremia than the isogenic PorB3-expressing strain (P < 0.0001 at both challenge doses). These data provide strong evidence that expression of PorB2 (alone) altered the ability of H44/76 fHbp nspA to cause bacteremia in WT infant rats.

FIG 4.

Expression of PorB2 enhances bacteremia in the infant rat model. Six- to 8-day-old WT infant Wistar rats (A) or human fH transgenic Wistar rats (B) were challenged intraperitoneally with either H44/76 fHbp nspA-PorB3 (B3) or its isogenic mutant, H44/76 fHbp nspA-PorB2 (B2). Both mutants expressed capsule and LOS sialic acid. Bacterial inocula used for each experiment are indicated alongside each graph (upper left). Colony-forming units (CFU)/ml in blood of individual animals at 6 h are indicated on the y axis. ****, P < 0.0001. When the data from both challenge doses were analyzed together, the proportion of positive blood cultures in the animals challenged with the PorB3 mutant was lower than that of animals challenged with the PorB2 mutant.

In a separate experiment, human fH Tg infant rats were challenged with either 6 × 102 or 6 × 103 CFU of the same two strains. As previously reported (21), the presence of human fH enhanced the ability of the PorB3-expressing H44/76 strain that lacked fHbp and NspA to cause bacteremia (Fig. 4B). When the data from both challenge doses were analyzed together, the proportion of positive blood cultures in animals challenged with the PorB3-expressing strain (18/26, 69%) was lower than that of animals challenged with the PorB2-expressing strain (22/24, 92%; chi-square, 8.8; df = 2; P = 0.03). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that when only rat fH was present, there was a nearly absolute requirement for PorB2 expression for survival of strain H44/76 fHbp nspA in the bloodstream, whereas when both rat and human fH were present, either PorB2 or PorB3 could support infection. These data provide a mechanistic explanation for the greater survival of PorB2 isolates in the infant rat model.

DISCUSSION

Neisseria PorB is an integral membrane protein organized as a β barrel with 16 transmembrane domains and eight predicted surface-exposed loops (48, 49) that allow for passage of small molecules across the outer membrane. Meningococcal PorB is divided into two classes; PorB2 and PorB3 are mutually exclusive and expressed from alternate alleles (porB2 and porB3) at the porB locus. We showed recently that meningococcal PorB2 regulates the human AP in an fH-dependent manner (19) and that PorB2 confers increased survival in human serum compared to PorB3. Strains that belong to the hypervirulent ST-11 clonal complex all express PorB2, and the ability of PorB2 to regulate complement may, in part, explain their preponderance among invasive strains that lack fHbp expression (50, 51).

Humans are the only natural hosts for N. meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Several factors may account for the human-specific nature of neisserial infections. These include the ability to scavenge iron selectively from human transferrin and lactoferrin (52, 53), binding to human-specific cellular receptors such as human carcino-embryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAMs) (54, 55), and human-specific complement evasion (25, 35, 56). Binding of fH to fHbp and NspA is generally accepted to be human specific (18, 25) although preliminary data suggest that fH from some, but not all, rhesus macaques can also bind to fHbp (57).

Despite species-specific barriers, animal models of neisserial infection are used to assess virulence attributes in an in vivo environment. Meningococcal bacteremia in infant rats following i.p. inoculation is one commonly used model. It is noteworthy that many of the meningococcal strains routinely used in the infant rat model expressed PorB2. A summary of these studies is provided in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of inocula used in meningococcal rat studiesa

| PorB type and N. meningitidis strainb | Rat strain and age (days) | Inoculumc | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PorB2 | |||

| 2996 | Wistar, infant (4–6) | 102-106 | 20 |

| 2996 | Wistar, infantd | 6 × 104, 5 × 103 | 58 |

| 2996 | Wistar, infant (5–6) | 103, 105 | 59 |

| 2996 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 4.2 × 103 | 39 |

| 2996 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 5.6 × 103 | 60 |

| 2996 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 5.7 × 103 | 61 |

| 2996 | Wistar, infant (5) | 105 | 62 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (4–7) | 5 × 102–5 × 103 | 44 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 8 × 102–1.4 × 103 | 23 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 103 | 63 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 103 | 37 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 103 | 39 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (4–7) | 1.3 × 103 | 64 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (5) | 1.9 × 103 | 65 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 2.2 × 103–5.2 × 103 | 66 |

| 4243 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 2.2 × 103–5.2 × 103 | 67 |

| 4335 | Wistar, infant (4–7) | 5 × 102–5 × 103 | 44 |

| 8047 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 2.3 × 103 | 38 |

| 8047 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 4 × 103–7 × 103 | 68 |

| 8047 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 5 × 103 | 61 |

| 8047 | Wistar, infant (5) | 5 × 103 | 69 |

| 8047 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 5.8 × 103 | 70 |

| 8047 | Wistar, infant (6–7) | 6.3 × 103 | 71 |

| 8047 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 7 × 103 | 60 |

| BZ232 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 2.5 × 102, 2.5 × 105 | 72 |

| BZ232 | Wistar, infant (7) | 4.4 × 103 | 73 |

| BZ232 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | ∼5 × 103 | 74 |

| BZ232 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 7.1 × 103 | 70 |

| BZ232 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 1.5 × 104 | 38 |

| C2120 | Wistar, infantd | 106–107 | 75 |

| M986 | Wistar, infant (4–6) | 102–106 | 20 |

| M986 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 2 × 103 | 38 |

| M986 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 3.5 × 103–6.5 × 103 | 70 |

| M986 | Wistar, infant (5–8) | 4.6 × 103 | 61 |

| M986 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | ∼5 × 103 | 74 |

| M986 | Wistar, infant (6–7) | 5.4 × 103 | 71 |

| M986 | Wistar, infant (4–6) | 1.04 × 104 | 76 |

| 8013 | Lewis, infant (5) | 1 × 106–2 × 106 | 77 |

| 8013 | Lewis, infant (5) | 2 × 106 | 78 |

| PorB3 | |||

| H44/76 | Wistar human fH Tg, infant (5–7) | 5 × 102–5 × 103 | 21 |

| H44/76 | Wistar human fH Tg, infant (8–10) | 5 × 102–5 × 103 | 21 |

| H44/76 | Wistar, infant (4–6) | 102–106 | 20 |

| H44/76 | Wistar, infant (4–6) | 105 | 46 |

| H44/76 | Wistar, infant (5) | 105 | 79 |

| H44/76 | Wistar, infant (5) | 105 | 62 |

| H44/76 | Wistar, infantd | 106 | 45 |

| H44/76 | Wistar, infant (5) | 106 | 80 |

| H44/76 | Wistar, infant (5) | 106 | 81 |

| H44/76 | Sprague-Dawle, infant (3) | 0.5 × 107–1.0× 107 | 82 |

| H44/76 | Sprague-Dawle, infant (3–4) | 2.1 × 105 | 83 |

| H44/76 | PVG, C6 deficient (5–7)e | 105–106 | 84 |

| H44/76 | PVG, C6 deficient (5–7) | 106 | 85 |

| H44/76 | PVG/OlaHsd (5–7)e | 106 | 85 |

| H44/76 | HsdCpd:WU (5–7)f | 105–106 | 84 |

| H44/76 | HsdBrlHan:WIST (5–7)f | 106 | 85 |

| CU385 | Wistar, infantd | 106 | 24 |

| CU385 | Wistar, infantd | 107 | 86 |

| CU385 | Wistar, infantd | 107 | 87 |

| CU385 | Wistar, infant (5–6) | 107 | 88 |

| CU385 | Wistar, infant (5–6) | 107 | 89 |

| CU385 | Wistar, infant (5–6)g | 107 | 90 |

| IH 5341 | Wistar, infant (4–6) | 104–106 | 91 |

| MC58 | Wistar, infant (6) | 105, 106, 107 | 92 |

| MC58 | Wistar, infantd | 106–107 | 75 |

| MC58 | Wistar, infant (5) | 107 | 93 |

| MC58 | Wistar, infant (5) | 107 | 94 |

| MC58 | Wistar, infant (7) | 4.9 × 107 | 73 |

| MC58-lpt3 | Wistar, infantd | 1.32 × 108 | 95 |

| MC58-icsB-lpt3 | Wistar, infantd | 5.66 ×108 | 95 |

| MC58 | Lewis, infant (4) | 7.7 × 105 | 96 |

| MC58 | Lewis, infant (4–5) | ∼106–107h | 97 |

| H355 | Sprague-Dawle, infant (3) | 0.5 × 107–1.0 × 107 | 82 |

| N.44/89 | Sprague-Dawle, infant (5) | 106 | 98 |

| NZ98/254 | Wistar, infant (5–7) | 104 | 23 |

| NZ98/254 | Wistar, unknown | 6 × 104 | 99 |

PubMed search terms were “rat” and “meningitidis.” Studies using N. meningitidis strains with unknown PorB types and studies with unspecified inocula were omitted.

Only wild-type bacterial strains were indicated in publications that included both wild-type and mutant strains.

Unless specified, the route of inoculation was intraperitoneal.

Exact age not specified.

Inbred.

Outbred.

With iron dextran.

One hundred microliters of MC58 at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.06.

Although methodological differences exist across studies, including the age and strain of animal used and the buffer or medium used to suspend the inocula, it is worth noting that, in general, larger inocula have been used with PorB3-expressing isolates, such as MC58 and H44/76, than with PorB2-expressing isolates, such as 4243. As noted above, PorB2-expressing meningococci readily cause bacteremia with inocula as low as 103 CFU.

Meningococcal challenge models also have been performed in adult mice (typically aged 6 to 8 weeks). In mice, inocula greater than 106 CFU are required to cause bacteremia, and again investigators have tended to disproportionally use PorB2 isolates such as FAM20 (100, 101), NMB (102), LNP24198 (103), LNP8013, or 4243. The bias toward the use of PorB2-expressing meningococcal strains in animal models may reflect the propensity for these strains to evade rodent complement better and to more easily cause disease than PorB3-expressing isolates.

In the present study, replacement of the endogenous PorB3 of H44/76 fHbp nspA with PorB2 from strain 4243 enhanced bacteremia in WT rats (Fig. 4A). These data indicate a role for PorB2 for invasive infection of WT infant rats challenged with low inocula. This finding is in accordance with the ability of PorB2 to inhibit infant rat complement. The results provide an explanation, at least in part, of why certain isolates, such as 4243 (PorB2), readily cause bacteremia in WT infant rats, while others, such as H44/76 (PorB3), do not.

In addition to the human pathogens N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, the genus Neisseria also includes several human commensal species (e.g., N. lactamica, N. cinerea, N. polysaccharea, N. mucosa, N. flavescens, N. sicca, and N. subflava) and several animal species (N. animalis, N. canis, N. weaveri, N. denitrificans, N. macacae, N. dentiae, and N. iguanae). Derrick et al. studied the phylogenetic relationships of the porin genes from a broad range of Neisseria species and found that the meningococcal PorB3 was most related to gonococcal PorB.1A and that these porins formed a clade with other PorB proteins from N. gonorrhoeae (PorB.1B), N. lactamica, and N. polysaccharea (104). Interestingly, although PorB2 shares similarity with members of this clade, it was not a part of the clade. PorB2 was positioned between the PorB3-containing clade and a clade of PorB proteins from other commensal and animal Neisseria species. The phylogenetic data suggest that PorB2 may have arisen from intragenic recombination between ancestral porins from species pathogenic in humans and commensal/animal species (104). The unique ability of PorB2 to regulate the AP of both human and nonhuman animals extends the diverse nature of the PorB2 molecule among PorB molecules.

Tg animals that express human-specific molecules are being developed to surmount barriers associated with species-specific virulence properties and to improve animal models for neisserial infection. One such example is the human fH Tg rat, which was created to investigate the virulence of meningococcal strains that inhibit complement in a nonhuman model. While the WT strain of H44/76 and H44/76 fHbp nspA that expressed PorB3 were minimally virulent in WT infant rats, their virulence was enhanced in fH Tg animals (21). In the present study, we observed smaller differences in the levels of bacteremia caused by PorB2- and PorB3-expressing mutants in fH Tg rats than in WT rats. The Tg model permits the use of a wider repertoire of meningococcal strains in infant rats for pathogenesis studies.

Another interesting finding in this study was selective regulation of baby rabbit and infant rat complement by PorB2-expressing strains. Regulation of nonhuman complement by PorB2 strains was restricted to sera of young animals and was not seen in our previous studies with sera from adult animals (19). Although beyond the scope of the current study, we hypothesize that immaturity of the complement system, as has been reported in humans, and, in particular, decreased activity of the AP (105–107) may have permitted selective regulation of infant rat/baby rabbit nonhuman complement by PorB2 isolates.

While preferential binding of human fH may at least in part explain differences across species in AP activation on meningococci, additional factors may tip the balance on microbial surfaces toward activation in some animals and toward inhibition in others. The pioneering work by Pillemer and colleagues showed wide variations in properdin titers (a reflection of AP activity) of sera from various animal species, with rats exhibiting the highest titers (108). As noted above, the interactions of rat or rabbit fH with PorB2 may not be sufficient to overcome a mature (adult animal) AP, and exogenous human fH may be needed in these instances. The ability of PorB2 isolates to better downregulate baby rabbit complement than PorB3 isolates adds yet another variable in interpretation of serum bactericidal assay results with baby rabbit complement and further emphasizes the need to use human complement in these assays.

In conclusion, this report sheds light on an important immune evasion function mediated by meningococcal PorB and serves to explain, at least in part, the variations in strain virulence in the infant rat model. These findings could guide the choice of strains for future studies of meningococcal virulence and measurement of vaccine efficacy in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants AI054544 (principal investigator [PI], S.R.), AI084048 (PIs, Peter A. Rice and Douglas Golenbock), AI32725 (PI, Peter A. Rice), AI046464 (PI, D.M.G.), and AI082263 (PI, D.M.G.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. The work at Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute was performed in a facility funded by Research Facilities Improvement Program grant number C06 RR 016226 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH.

We thank Ulrich Vogel (Universität Würzburg, Germany) for providing meningococcal strains A2594, H44/76, C2120, and W171 and their mutants lacking capsule and LOS sialic acid. We thank Jutamas Shaughnessy (University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA) for providing fH67/Fc.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosenstein NE, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, Popovic T, Hughes JM. 2001. Meningococcal disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1378–1388. 10.1056/NEJM200105033441807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan LK, Carlone GM, Borrow R. 2010. Advances in the development of vaccines against Neisseria meningitidis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362:1511–1520. 10.1056/NEJMra0906357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Figueroa J, Andreoni J, Densen P. 1993. Complement deficiency states and meningococcal disease. Immunol. Res. 12:295–311. 10.1007/BF02918259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ram S, Lewis LA, Rice PA. 2010. Infections of people with complement deficiencies and patients who have undergone splenectomy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:740–780. 10.1128/CMR.00048-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austen KF, Fearon DT. 1979. A molecular basis of activation of the alternative pathway of human complement. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 120B:3–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearon DT, Austen KF. 1975. Properdin: binding to C3b and stabilization of the C3b-dependent C3 convertase. J. Exp. Med. 142:856–863. 10.1084/jem.142.4.856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giuntini S, Reason DC, Granoff DM. 2012. Combined roles of human IgG subclass, alternative complement pathway activation, and epitope density in the bactericidal activity of antibodies to meningococcal factor H binding protein. Infect. Immun. 80:187–194. 10.1128/IAI.05956-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira VP, Pangburn MK, Cortes C. 2010. Complement control protein factor H: the good, the bad, and the inadequate. Mol. Immunol. 47:2187–2197. 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pangburn MK, Muller-Eberhard HJ. 1978. Complement C3 convertase: cell surface restriction of β1H control and generation of restriction on neuraminidase-treated cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75:2416–2420. 10.1073/pnas.75.5.2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pangburn MK, Schreiber RD, Muller-Eberhard HJ. 1977. Human complement C3b inactivator: isolation, characterization, and demonstration of an absolute requirement for the serum protein β1H for cleavage of C3b and C4b in solution. J. Exp. Med. 146:257–270. 10.1084/jem.146.1.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whaley K, Ruddy S. 1976. Modulation of the alternative complement pathways by beta 1 H globulin. J. Exp. Med. 144:1147–1163. 10.1084/jem.144.5.1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fearon DT, Austen KF. 1977. Activation of the alternative complement pathway due to resistance of zymosan-bound. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74:1683–1687. 10.1073/pnas.74.4.1683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiler JM, Daha MR, Austen KF, Fearon DT. 1976. Control of the amplification convertase of complement by the plasma protein beta1H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 73:3268–3272. 10.1073/pnas.73.9.3268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarvis GA, Vedros NA. 1987. Sialic acid of group B Neisseria meningitidis regulates alternative complement pathway activation. Infect. Immun. 55:174–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ram S, Lewis LA, Agarwal S. 2011. Meningococcal group W-135 and Y capsular polysaccharides paradoxically enhance activation of the alternative pathway of complement. J. Biol. Chem. 286:8297–8307. 10.1074/jbc.M110.184838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis LA, Carter M, Ram S. 2012. The relative roles of factor H binding protein, neisserial surface protein A, and lipooligosaccharide sialylation in regulation of the alternative pathway of complement on meningococci. J. Immunol. 188:5063–5072. 10.4049/jimmunol.1103748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madico G, Welsch JA, Lewis LA, McNaughton A, Perlman DH, Costello CE, Ngampasutadol J, Vogel U, Granoff DM, Ram S. 2006. The meningococcal vaccine candidate GNA1870 binds the complement regulatory protein factor H and enhances serum resistance. J. Immunol. 177:501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis LA, Ngampasutadol J, Wallace R, Reid JE, Vogel U, Ram S. 2010. The meningococcal vaccine candidate neisserial surface protein A (NspA) binds to factor H and enhances meningococcal resistance to complement. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001027. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis LA, Vu DM, Vasudhev S, Shaughnessy J, Granoff DM, Ram S. 2013. Factor H-Dependent Alternative Pathway Inhibition Mediated by Porin B Contributes to Virulence of Neisseria meningitidis. mBio 4(5):e00339–13. 10.1128/mBio.00339-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saukkonen K. 1988. Experimental meningococcal meningitis in the infant rat. Microb. Pathog. 4:203–211. 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90070-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vu DM, Shaughnessy J, Lewis LA, Ram S, Rice PA, Granoff DM. 2012. Enhanced bacteremia in human factor H transgenic rats infected by Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 80:643–650. 10.1128/IAI.05604-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claus H, Weinand H, Frosch M, Vogel U. 2003. Identification of the hypervirulent lineages of Neisseria meningitidis, the ST-8 and ST-11 complexes, by using monoclonal antibodies specific to NmeDI. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3873–3876. 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3873-3876.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welsch JA, Granoff D. 2004. Naturally acquired passive protective activity against Neisseria meningitidis group C in the absence of serum bactericidal activity. Infect. Immun. 72:5903–5909. 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5903-5909.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toropainen M, Saarinen L, Wedege E, Bolstad K, Makela PH, Kayhty H. 2005. Passive protection in the infant rat protection assay by sera taken before and after vaccination of teenagers with serogroup B meningococcal outer membrane vesicle vaccines. Vaccine 23:4821–4833. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granoff DM, Welsch JA, Ram S. 2009. Binding of complement factor H (fH) to Neisseria meningitidis is specific for human fH and inhibits complement activation by rat and rabbit sera. Infect. Immun. 77:764–769. 10.1128/IAI.01191-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoen C, Weber-Lehmann J, Blom J, Joseph B, Goesmann A, Strittmatter A, Frosch M. 2011. Whole-genome sequence of the transformable Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A strain WUE2594. J. Bacteriol. 193:2064–2065. 10.1128/JB.00084-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frasch C, Zollinger W, Poolman J. 1985. Proposed schema for identification of serotypes of Neisseria meningitidis, p 519–524 In Schoolnik G. (ed), The pathogenic Neisseria. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin DR, Walker SJ, Baker MG, Lennon DR. 1998. New Zealand epidemic of meningococcal disease identified by a strain with phenotype B:4:P1.4. J. Infect. Dis. 177:497–500. 10.1086/517385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welsch JA, Rossi R, Comanducci M, Granoff DM. 2004. Protective activity of monoclonal antibodies to genome-derived neisserial antigen 1870, a Neisseria meningitidis candidate vaccine. J. Immunol. 172:5606–5615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogel U, Morelli G, Zurth K, Claus H, Kriener E, Achtman M, Frosch M. 1998. Necessity of molecular techniques to distinguish between Neisseria meningitidis strains isolated from patients with meningococcal disease and from their healthy contacts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2465–2470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claus H, Borrow R, Achtman M, Morelli G, Kantelberg C, Longworth E, Frosch M, Vogel U. 2004. Genetics of capsule O-acetylation in serogroup C, W-135 and Y meningococci. Mol. Microbiol. 51:227–239. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03819.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pastor P, Medley FB, Murphy TV. 2000. Meningococcal disease in Dallas County, Texas: results of a six-year population-based study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:324–328. 10.1097/00006454-200004000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Ley P, Heckels JE, Virji M, Hoogerhout P, Poolman JT. 1991. Topology of outer membrane porins in pathogenic Neisseria spp. Infect. Immun. 59:2963–2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madico G, Ngampasutadol J, Gulati S, Vogel U, Rice PA, Ram S. 2007. Factor H binding and function in sialylated pathogenic neisseriae is influenced by gonococcal, but not meningococcal, porin. J. Immunol. 178:4489–4497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ngampasutadol J, Ram S, Gulati S, Agarwal S, Li C, Visintin A, Monks B, Madico G, Rice PA. 2008. Human factor H interacts selectively with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and results in species-specific complement evasion. J. Immunol. 180:3426–3435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaughnessy J, Lewis LA, Jarva H, Ram S. 2009. Functional comparison of the binding of factor H short consensus repeat 6 (SCR 6) to factor H binding protein from Neisseria meningitidis and the binding of factor H SCR 18 to 20 to Neisseria gonorrhoeae porin. Infect. Immun. 77:2094–2103. 10.1128/IAI.01561-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Granoff DM, Harris SL. 2004. Protective activity of group C anticapsular antibodies elicited in two-year-olds by an investigational quadrivalent Neisseria meningitidis-diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 23:490–497. 10.1097/01.inf.0000129686.12470.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moe GR, Zuno-Mitchell P, Lee SS, Lucas AH, Granoff DM. 2001. Functional activity of anti-neisserial surface protein A monoclonal antibodies against strains of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. Infect. Immun. 69:3762–3771. 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3762-3771.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welsch JA, Moe GR, Rossi R, Adu-Bobie J, Rappuoli R, Granoff DM. 2003. Antibody to genome-derived neisserial antigen 2132, a Neisseria meningitidis candidate vaccine, confers protection against bacteremia in the absence of complement-mediated bactericidal activity. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1730–1740. 10.1086/379375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borrow R, Andrews N, Goldblatt D, Miller E. 2001. Serological basis for use of meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccines in the United Kingdom: reevaluation of correlates of protection. Infect. Immun. 69:1568–1573. 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1568-1573.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borrow R, Carlone GM, Rosenstein N, Blake M, Feavers I, Martin D, Zollinger W, Robbins J, Aaberge I, Granoff DM, Miller E, Plikaytis B, van Alphen L, Poolman J, Rappuoli R, Danzig L, Hackell J, Danve B, Caulfield M, Lambert S, Stephens D. 2006. Neisseria meningitidis group B correlates of protection and assay standardization-international meeting report Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States, 16–17 March 2005. Vaccine 24:5093–5107. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishola DA, Jr, Borrow R, Findlow H, Findlow J, Trotter C, Ramsay ME. 2012. Prevalence of serum bactericidal antibody to serogroup C Neisseria meningitidis in England a decade after vaccine introduction. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 19:1126–1130. 10.1128/CVI.05655-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zipfel PF, Skerka C. 1999. FHL-1/reconectin: a human complement and immune regulator with cell-adhesive function. Immunol. Today 20:135–140. 10.1016/S0167-5699(98)01432-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris SL, King WJ, Ferris W, Granoff DM. 2003. Age-related disparity in functional activities of human group C serum anticapsular antibodies elicited by meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Infect. Immun. 71:275–286. 10.1128/IAI.71.1.275-286.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saukkonen K, Leinonen M, Kayhty H, Abdillahi H, Poolman JT. 1988. Monoclonal antibodies to the rough lipopolysaccharide of Neisseria meningitidis protect infant rats from meningococcal infection. J. Infect. Dis. 158:209–212. 10.1093/infdis/158.1.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toropainen M, Saarinen L, van der Ley P, Kuipers B, Kayhty H. 2001. Murine monoclonal antibodies to PorA of Neisseria meningitidis show reduced protective activity in vivo against B:15:P1.7,16 subtype variants in an infant rat infection model. Microb. Pathog. 30:139–148. 10.1006/mpat.2000.0419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis LA, Ram S. 2014. Meningococcal disease and the complement system. Virulence 5:98–126. 10.4161/viru.26515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Massari P, Ram S, Macleod H, Wetzler LM. 2003. The role of porins in neisserial pathogenesis and immunity. Trends Microbiol. 11:87–93. 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)00037-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanabe M, Nimigean CM, Iverson TM. 2010. Structural basis for solute transport, nucleotide regulation, and immunological recognition of Neisseria meningitidis PorB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:6811–6816. 10.1073/pnas.0912115107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lucidarme J, Tan L, Exley RM, Findlow J, Borrow R, Tang CM. 2011. Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis isolates that do not express the virulence factor and vaccine antigen factor H binding protein. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18:1002–1014. 10.1128/CVI.00055-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giuntini S, Vu DM, Granoff DM. 2013. fH-dependent complement evasion by disease-causing meningococcal strains with absent fHbp genes or frameshift mutations. Vaccine 31:4192–4199. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gray-Owen SD, Schryvers AB. 1993. The interaction of primate transferrins with receptors on bacteria pathogenic to humans. Microb. Pathog. 14:389–398. 10.1006/mpat.1993.1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee BC, Schryvers AB. 1988. Specificity of the lactoferrin and transferrin receptors in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 2:827–829. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray-Owen SD, Dehio C, Haude A, Grunert F, Meyer TF. 1997. CD66 carcinoembryonic antigens mediate interactions between Opa-expressing Neisseria gonorrhoeae and human polymorphonuclear phagocytes. EMBO J. 16:3435–3445. 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gu A, Zhang Z, Zhang N, Tsark W, Shively JE. 2010. Generation of human CEACAM1 transgenic mice and binding of Neisseria Opa protein to their neutrophils. PLoS One 5:e10067. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ngampasutadol J, Ram S, Blom AM, Jarva H, Jerse AE, Lien E, Goguen J, Gulati S, Rice PA. 2005. Human C4b-binding protein selectively interacts with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and results in species-specific infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:17142–17147. 10.1073/pnas.0506471102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Granoff D, Shaughnessy J, Beernink PT, Vasudhev S, Santos G, Ram S. 2012. Heterogeneity of binding of rhesus macaque factor H to meningococcal factor H binding protein, poster 287, p 438 Abstr. XVIIIth Int. Pathog. Neisseria Conf., Wurzburg, Germany, 9 to 14 September 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Giuliani MM, Adu-Bobie J, Comanducci M, Arico B, Savino S, Santini L, Brunelli B, Bambini S, Biolchi A, Capecchi B, Cartocci E, Ciucchi L, Di Marcello F, Ferlicca F, Galli B, Luzzi E, Masignani V, Serruto D, Veggi D, Contorni M, Morandi M, Bartalesi A, Cinotti V, Mannucci D, Titta F, Ovidi E, Welsch JA, Granoff D, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. 2006. A universal vaccine for serogroup B meningococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:10834–10839. 10.1073/pnas.0603940103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fantappie L, Metruccio MM, Seib KL, Oriente F, Cartocci E, Ferlicca F, Giuliani MM, Scarlato V, Delany I. 2009. The RNA chaperone Hfq is involved in stress response and virulence in Neisseria meningitidis and is a pleiotropic regulator of protein expression. Infect. Immun. 77:1842–1853. 10.1128/IAI.01216-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Comanducci M, Bambini S, Brunelli B, Adu-Bobie J, Arico B, Capecchi B, Giuliani MM, Masignani V, Santini L, Savino S, Granoff DM, Caugant DA, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Mora M. 2002. NadA, a novel vaccine candidate of Neisseria meningitidis. J. Exp. Med. 195:1445–1454. 10.1084/jem.20020407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Plested JS, Harris SL, Wright JC, Coull PA, Makepeace K, Gidney MA, Brisson JR, Richards JC, Granoff DM, Moxon ER. 2003. Highly conserved Neisseria meningitidis inner-core lipopolysaccharide epitope confers protection against experimental meningococcal bacteremia. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1223–1234. 10.1086/368360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saukkonen K, Abdillahi H, Poolman JT, Leinonen M. 1987. Protective efficacy of monoclonal antibodies to class 1 and class 3 outer membrane proteins of Neisseria meningitidis B:15:P1.16 in infant rat infection model: new prospects for vaccine development. Microb. Pathog. 3:261–267. 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Granoff DM, Morgan A, Welsch JA. 2005. Persistence of group C anticapsular antibodies two to three years after immunization with an investigational quadrivalent Neisseria meningitidis-diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 24:132–136. 10.1097/01.inf.0000151035.64356.f8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harris SL, Finn A, Granoff DM. 2003. Disparity in functional activity between serum anticapsular antibodies induced in adults by immunization with an investigational group A and C Neisseria meningitidis-diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine and by a polysaccharide vaccine. Infect. Immun. 71:3402–3408. 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3402-3408.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Masignani V, Comanducci M, Giuliani MM, Bambini S, Adu-Bobie J, Arico B, Brunelli B, Pieri A, Santini L, Savino S, Serruto D, Litt D, Kroll S, Welsch JA, Granoff DM, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. 2003. Vaccination against Neisseria meningitidis using three variants of the lipoprotein GNA1870. J. Exp. Med. 197:789–799. 10.1084/jem.20021911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vu DM, Kelly D, Heath PT, McCarthy ND, Pollard AJ, Granoff DM. 2006. Effectiveness analyses may underestimate protection of infants after group C meningococcal immunization. J. Infect. Dis. 194:231–237. 10.1086/505077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vu DM, Welsch JA, Zuno-Mitchell P, Dela Cruz JV, Granoff DM. 2006. Antibody persistence 3 years after immunization of adolescents with quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 193:821–828. 10.1086/500512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bayliss CD, Hoe JC, Makepeace K, Martin P, Hood DW, Moxon ER. 2008. Neisseria meningitidis escape from the bactericidal activity of a monoclonal antibody is mediated by phase variation of lgtG and enhanced by a mutator phenotype. Infect. Immun. 76:5038–5048. 10.1128/IAI.00395-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cox AD, Zou W, Gidney MA, Lacelle S, Plested JS, Makepeace K, Wright JC, Coull PA, Moxon ER, Richards JC. 2005. Candidacy of LPS-based glycoconjugates to prevent invasive meningococcal disease: developmental chemistry and investigation of immunological responses following immunization of mice and rabbits. Vaccine 23:5045–5054. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Granoff DM, Moe GR, Giuliani MM, Adu-Bobie J, Santini L, Brunelli B, Piccinetti F, Zuno-Mitchell P, Lee SS, Neri P, Bracci L, Lozzi L, Rappuoli R. 2001. A novel mimetic antigen eliciting protective antibody to Neisseria meningitidis. J. Immunol. 167:6487–6496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moe GR, Tan S, Granoff DM. 1999. Differences in surface expression of NspA among Neisseria meningitidis group B strains. Infect. Immun. 67:5664–5675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adu-Bobie J, Lupetti P, Brunelli B, Granoff D, Norais N, Ferrari G, Grandi G, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. 2004. GNA33 of Neisseria meningitidis is a lipoprotein required for cell separation, membrane architecture, and virulence. Infect. Immun. 72:1914–1919. 10.1128/IAI.72.4.1914-1919.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bartolini E, Frigimelica E, Giovinazzi S, Galli G, Shaik Y, Genco C, Welsch JA, Granoff DM, Grandi G, Grifantini R. 2006. Role of FNR and FNR-regulated, sugar fermentation genes in Neisseria meningitidis infection. Mol. Microbiol. 60:963–972. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05163.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moe GR, Zuno-Mitchell P, Hammond SN, Granoff DM. 2002. Sequential immunization with vesicles prepared from heterologous Neisseria meningitidis strains elicits broadly protective serum antibodies to group B strains. Infect. Immun. 70:6021–6031. 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6021-6031.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vogel U, Claus H, Heinze G, Frosch M. 1999. Role of lipopolysaccharide sialylation in serum resistance of serogroup B and C meningococcal disease isolates. Infect. Immun. 67:954–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moe GR, Bhandari TS, Flitter BA. 2009. Vaccines containing de-N-acetyl sialic acid elicit antibodies protective against Neisseria meningitidis groups B and C. J. Immunol. 182:6610–6617. 10.4049/jimmunol.0803677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stojiljkovic I, Hwa V, Larson J, Lin L, So M, Nassif X. 1997. Cloning and characterization of the Neisseria meningitidis rfaC gene encoding alpha-1,5 heptosyltransferase I. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151:41–49. 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00135-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stojiljkovic I, Hwa V, de Saint Martin L, O'Gaora P, Nassif X, Heffron F, So M. 1995. The Neisseria meningitidis haemoglobin receptor: its role in iron utilization and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 15:531–541. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tarkka E, Muotiala A, Karvonen M, Saukkonen-Laitinen K, Sarvas M. 1989. Antibody production to a meningococcal outer membrane protein cloned into live Salmonella typhimurium aroA vaccine strain. Microb. Pathog. 6:327–335. 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90074-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nurminen M, Butcher S, Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Wahlstrom E, Muttilainen S, Runeberg-Nyman K, Sarvas M, Makela PH. 1992. The class 1 outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis produced in Bacillus subtilis can give rise to protective immunity. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2499–2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tala A, Monaco C, Nagorska K, Exley RM, Corbett A, Zychlinsky A, Alifano P, Tang CM. 2011. Glutamate utilization promotes meningococcal survival in vivo through avoidance of the neutrophil oxidative burst. Mol. Microbiol. 81:1330–1342. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07766.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schmidt S, Zhu D, Barniak V, Mason K, Zhang Y, Arumugham R, Metcalf T. 2001. Passive immunization with Neisseria meningitidis PorA specific immune sera reduces nasopharyngeal colonization of group B meningococcus in an infant rat nasal challenge model. Vaccine 19:4851–4858. 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00229-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu D, Zhang Y, Barniak V, Bernfield L, Howell A, Zlotnick G. 2005. Evaluation of recombinant lipidated P2086 protein as a vaccine candidate for group B Neisseria meningitidis in a murine nasal challenge model. Infect. Immun. 73:6838–6845. 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6838-6845.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Toropainen M, Saarinen L, Wedege E, Bolstad K, Michaelsen TE, Aase A, Kayhty H. 2005. Protection by natural human immunoglobulin M antibody to meningococcal serogroup B capsular polysaccharide in the infant rat protection assay is independent of complement-mediated bacterial lysis. Infect. Immun. 73:4694–4703. 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4694-4703.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Toropainen M, Saarinen L, Vidarsson G, Kayhty H. 2006. Protection by meningococcal outer membrane protein PorA-specific antibodies and a serogroup B capsular polysaccharide-specific antibody in complement-sufficient and C6-deficient infant rats. Infect. Immun. 74:2803–2808. 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2803-2808.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Delgado M, Yero D, Niebla O, Gonzalez S, Climent Y, Perez Y, Cobas K, Caballero E, Garcia D, Pajon R. 2007. Lipoprotein NMB0928 from Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B as a novel vaccine candidate. Vaccine 25:8420–8431. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.09.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sardinas G, Climent Y, Rodriguez Y, Gonzalez S, Garcia D, Cobas K, Caballero E, Perez Y, Brookes C, Taylor S, Gorringe A, Delgado M, Pajon R, Yero D. 2009. Assessment of vaccine potential of the Neisseria-specific protein NMB0938. Vaccine 27:6910–6917. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yero CD, Pajon FR, Caballero ME, Cobas AK, Lopez HY, Farinas MM, Gonzales BS, Acosta DA. 2005. Immunization of mice with Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B genomic expression libraries elicits functional antibodies and reduces the level of bacteremia in an infant rat infection model. Vaccine 23:932–939. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sardinas G, Yero D, Climent Y, Caballero E, Cobas K, Niebla O. 2009. Neisseria meningitidis antigen NMB0088: sequence variability, protein topology and vaccine potential. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:196–208. 10.1099/jmm.0.004820-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sardinas G, Reddin K, Pajon R, Gorringe A. 2006. Outer membrane vesicles of Neisseria lactamica as a potential mucosal adjuvant. Vaccine 24:206–214. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Toropainen M, Kayhty H, Saarinen L, Rosenqvist E, Hoiby EA, Wedege E, Michaelsen T, Makela PH. 1999. The infant rat model adapted to evaluate human sera for protective immunity to group B meningococci. Vaccine 17:2677–2689. 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00049-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Seib KL, Oriente F, Adu-Bobie J, Montanari P, Ferlicca F, Giuliani MM, Rappuoli R, Pizza M, Delany I. 2010. Influence of serogroup B meningococcal vaccine antigens on growth and survival of the meningococcus in vitro and in ex vivo and in vivo models of infection. Vaccine 28:2416–2427. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Exley RM, Shaw J, Mowe E, Sun YH, West NP, Williamson M, Botto M, Smith H, Tang CM. 2005. Available carbon source influences the resistance of Neisseria meningitidis against complement. J. Exp. Med. 201:1637–1645. 10.1084/jem.20041548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carpenter EP, Corbett A, Thomson H, Adacha J, Jensen K, Bergeron J, Kasampalidis I, Exley R, Winterbotham M, Tang C, Baldwin GS, Freemont P. 2007. AP endonuclease paralogues with distinct activities in DNA repair and bacterial pathogenesis. EMBO J. 26:1363–1372. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jakel A, Plested JS, Hoe JC, Makepeace K, Gidney MA, Lacelle S, St Michael F, Cox AD, Richards JC, Moxon ER. 2008. Naturally occurring human serum antibodies to inner core lipopolysaccharide epitopes of Neisseria meningitidis protect against invasive meningococcal disease caused by isolates displaying homologous inner core structures. Vaccine 26:6655–6663. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Forman S, Linhartova I, Osicka R, Nassif X, Sebo P, Pelicic V. 2003. Neisseria meningitidis RTX proteins are not required for virulence in infant rats. Infect. Immun. 71:2253–2257. 10.1128/IAI.71.4.2253-2257.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Klee SR, Nassif X, Kusecek B, Merker P, Beretti JL, Achtman M, Tinsley CR. 2000. Molecular and biological analysis of eight genetic islands that distinguish Neisseria meningitidis from the closely related pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 68:2082–2095. 10.1128/IAI.68.4.2082-2095.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sacchi CT, Gorla MC, de Lemos AP, Brandileone MC. 1995. Considerations on the use of class 5 proteins as meningococcal BC vaccine components. Vaccine 13:112–118. 10.1016/0264-410X(95)80021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hou VC, Koeberling O, Welsch JA, Granoff DM. 2005. Protective antibody responses elicited by a meningococcal outer membrane vesicle vaccine with overexpressed genome-derived neisserial antigen 1870. J. Infect. Dis. 192:580–590. 10.1086/432102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Eriksson J, Eriksson OS, Jonsson AB. 2012. Loss of meningococcal PilU delays microcolony formation and attenuates virulence in vivo. Infect. Immun. 80:2538–2547. 10.1128/IAI.06354-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Johansson L, Rytkonen A, Bergman P, Albiger B, Kallstrom H, Hokfelt T, Agerberth B, Cattaneo R, Jonsson AB. 2003. CD46 in meningococcal disease. Science 301:373–375. 10.1126/science.1086476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Plant L, Sundqvist J, Zughaier S, Lovkvist L, Stephens DS, Jonsson AB. 2006. Lipooligosaccharide structure contributes to multiple steps in the virulence of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 74:1360–1367. 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1360-1367.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Szatanik M, Hong E, Ruckly C, Ledroit M, Giorgini D, Jopek K, Nicola MA, Deghmane AE, Taha MK. 2011. Experimental meningococcal sepsis in congenic transgenic mice expressing human transferrin. PLoS One 6:e22210. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Derrick JP, Urwin R, Suker J, Feavers IM, Maiden MC. 1999. Structural and evolutionary inference from molecular variation in Neisseria porins. Infect. Immun. 67:2406–2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Davis CA, Vallota EH, Forristal J. 1979. Serum complement levels in infancy: age related changes. Pediatr. Res. 13:1043–1046. 10.1203/00006450-197909000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.de Paula PF, Barbosa JE, Junior PR, Ferriani VP, Latorre MR, Nudelman V, Isaac L. 2003. Ontogeny of complement regulatory proteins—concentrations of factor H, factor I, c4b-binding protein, properdin and vitronectin in healthy children of different ages and in adults. Scand. J. Immunol. 58:572–577. 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Feinstein PA, Kaplan SR. 1975. The alternative pathway of complement activation in the neonate. Pediatr. Res. 9:803–806. 10.1203/00006450-197510000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pillemer L, Blum L, Lepow IH, Ross OA, Todd EW, Wardlaw AC. 1954. The properdin system and immunity. I. Demonstration and isolation of a new serum protein, properdin, and its role in immune phenomena. Science 120:279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]