Abstract

Vibrio cholerae is the causative agent of the acute diarrheal disease of cholera. Innate immune responses to V. cholerae are not a major cause of cholera pathology, which is characterized by severe, watery diarrhea induced by the action of cholera toxin. Innate responses may, however, contribute to resolution of infection and must be required to initiate adaptive responses after natural infection and oral vaccination. Here we investigated whether a well-established infant mouse model of cholera can be used to observe an innate immune response. We also used a vaccination model in which immunized dams protect their pups from infection through breast milk antibodies to investigate innate immune responses after V. cholerae infection for pups suckled by an immune dam. At the peak of infection, we observed neutrophil recruitment accompanied by induction of KC, macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), NOS-2, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-17a. Pups suckled by an immunized dam did not mount this response. Accessory toxins RtxA and HlyA played no discernible role in neutrophil recruitment in a wild-type background. The innate response to V. cholerae deleted for cholera toxin-encoding phage (CTXϕ) and part of rtxA was significantly reduced, suggesting a role for CTXϕ-carried genes or for RtxA in the absence of cholera toxin (CTX). Two extracellular V. cholerae DNases were not required for neutrophil recruitment, but DNase-deficient V. cholerae caused more clouds of DNA in the intestinal lumen, which appeared to be neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), suggesting that V. cholerae DNases combat NETs. Thus, the infant mouse model has hitherto unrecognized utility for interrogating innate responses to V. cholerae infection.

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio cholerae is the causative agent of cholera, which remains endemic in many regions of Africa and Asia (1). Sporadic outbreaks can devastate immunologically naïve populations, such as occurred in Haiti in 2010 (2). The O1 serogroup and, to a lesser degree, O139 are the major causes of cholera, and El Tor is currently the circulating O1 biotype (1). Cholera toxin (CTX), encoded by a lysogenic phage (3), is the major cause of the severe secretory diarrhea that is typical of cholera. Without rehydration therapy, cholera results in 25 to 50% mortality, but if treated, cholera will resolve in most patients (4). Unlike diseases such as shigellosis and Salmonella-induced gastroenteritis (5, 6), the pathology of cholera is not immune driven. However, innate immune responses have been observed in cholera patients during the acute phase of infection (7) and likely play a direct and/or indirect role in the resolution of disease. The majority of individuals who survive a bout of cholera will become immune to subsequent infection for at least 3 years (8–10), and some aspects of the observed innate immune response must be required to initiate this protective immunity.

Many live attenuated vaccine candidate strains of V. cholerae have been developed in which ctxA, the gene encoding the catalytic subunit of cholera toxin, is deleted (11). In volunteers, removal of ctxA did not completely alleviate V. cholerae-induced diarrhea, although it was mild, and signs of inflammation were still observed (12). Bacterial factors responsible for this residual diarrhea and inflammation include flagellin, which was a major V. cholerae proinflammatory stimulus in vitro (13–15), in the infant rabbit model of infection (16), and in a small-scale human volunteer study (17). In the infant rabbit model, flagellin-independent inflammation was still observed, suggesting that V. cholerae encodes other minor proinflammatory factors (16). In tissue culture models, purified V. cholerae O1 lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB (18), and hemolysin A (HlyA) contributes to inflammation induced by non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae supernatants (19). Repeats toxin, encoded by rtxA and elaborated by the El Tor V. cholerae O1 biotype, but not the extinct classical biotype (20), was implicated in El Tor-induced inflammation in an adult mouse pulmonary infection model (21), and both HlyA and RtxA are required for virulence in a mouse model of prolonged colonization (22).

On the host side of the equation, the molecular interactions that initiate innate immune responses to the noninvasive pathogen V. cholerae, or to oral vaccines derived from the bacterium, are not yet well described. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) can be activated by V. cholerae LPS in vitro (18). Also, after nasal infection with V. cholerae lacking proinflammatory toxins CTX, RtxA, and HlyA, morbidity was greater for mice lacking TLR4 expression, suggesting a role for TLR4-mediated inflammation in bacterial containment in the absence of other sources of inflammation (23). Using human epithelial cell lines, TLR5 was implicated in V. cholerae flagellin-induced inflammation (14, 15), although the sheath covering the V. cholerae flagellum reduces the potency of TLR5 signaling (24). A candidate gene association study found an interesting link between innate immunity and host susceptibility: a locus in the promoter of the long palate, lung, and nasal epithelium clone 1 (LPLUNC1) gene is associated with acute cholera (25), LPLUNC1 was also the most highly enriched gene transcript in duodenal biopsy samples during acute cholera (26), and the product of LPLUNC1 can inhibit LPS-induced, TLR4-mediated NF-κB activation (18). The authors suggested that too much of this anti-inflammatory activity may prevent cholera resolution.

Animal models have proven useful for interrogating V. cholerae mechanisms of pathogenesis, but less so for examining host immune responses. Inflammation due to V. cholerae has been studied with an adult mouse pulmonary infection model, but this is neither the natural route nor the site of infection (21). Adult mice are difficult to colonize orally with V. cholerae, but prolonged chronic colonization can be achieved either by antibiotic treatment or by neutralization of stomach acid combined with ketamine-xylazine treatment (22, 27). An acute lethal oral infection can be induced in adult mice, but this requires a large inoculum of V. cholerae and death is associated with systemic spread, which is not a normal cholera phenotype (28, 29). For 4 to 6 days, neonatal mice are permissive for V. cholerae colonization after oral inoculation, leading to an acute and potentially lethal infection of the small intestine without systemic spread, much like severe cholera in humans (30). Key bacterial virulence factors that are required for acute disease in humans, most notably CTX and toxin-coregulated pilus (Tcp) (31), are also induced in the neonatal mouse model, suggesting that it is a good model for acute cholera (32). Being a neonatal model could be considered an advantage, as a functional adaptive immune system has not yet developed, leaving the innate response to study in isolation. However, lack of a mature adaptive immune system means that neonates do not respond well to vaccination, thus limiting the use of mice for developing vaccines. To circumvent this, we used a mouse model in which immunized mothers protect their young through antibodies in their milk in order to study V. cholerae outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) as a potential cholera vaccine (33).

Here we show that neonatal mice can be used as a model to investigate innate immune responses to V. cholerae infection. At the peak of infection, we observed increased transcription of a subset of proinflammatory factors, accompanied by neutrophil recruitment and the appearance of what appeared to be neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). We investigated bacterial factors that may contribute to this inflammation and found possible roles for CTX, or for RtxA in the absence of CTX, and for secreted DNases, but not for HlyA or RtxA, in a wild-type (WT) background. Finally, we determined that intestinal inflammation is abrogated when neonates challenged with V. cholerae are suckled by OMV-immunization dams.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

V. cholerae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. V. cholerae was cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth with aeration or on LB agar plates supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin (Sm) at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E7946 | V. cholerae El Tor O1 Ogawa, spontaneous Smr mutant of E7946, a 1978 clinical isolate from Bahrain | 75 |

| Bah-2 | E7946 ΔattRS1 (a deletion of the two copies of the cholera toxin bacteriophage and its attachment sites, plus 1.9 kbp from the 3′ end of rtxA); here we term this the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain | 17 |

| AC2915 | E7946 ΔhlyA (a deletion of the gene encoding hemolysin A) | 53 |

| AC2912 | E7946 Δxds Δdns (ΔDNase) (deletions of genes encoding two extracellular DNases); the strain was constructed as described previously (50), but in a different strain background | This study |

| AC3671 | E7946 ΔrtxA (a deletion of the gene encoding repeats toxin) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCVD442 | oriR6K mobRP4 sacB Apr | 76 |

| pCVD442-ΔrtxA | pCVD442::ΔrtxA Apr | This study |

A mutant of O1 El Tor strain E7946 was generated in which almost all of rtxA (VC1451) was deleted. The deletion begins at the first base after the stop codon of the overlapping upstream gene VC1450, leaving five codons and one base of rtxA intact, followed by the rtxA stop codon. A PCR product containing the deletion was generated using strand overlap extension (34). Overlapping PCR products were generated using the following primers: rtxAF1b (5′-GCGTCTAGACGTTCAGACAGTCTCAAGTGTTAAC-3′) and rtxAR1 (5′-TACGCGATTATTAAATAGAAAACCACTGCACCT-3′) for the upstream product and rtxAF2 (5′-TTCTATTTAATAATCGCGTAGCCCAAATTTAAG-3′) and rtxAR2b (5′-GCGTCTAGACATCACGCAACCTCGTGATTG-3′) for the downstream product. A full-length deletion PCR product, which contained XbaI sites at each end, was amplified with rtxAF1b and rtxAR2b, digested with XbaI, and ligated into XbaI-digested pCVD442 to generate pCVD442-ΔrtxA. pCVD442-ΔrtxA was transformed into Sm10λpir, and exconjugants with V. cholerae E7946 were selected for single-crossover events (resistant to 50 μg ml−1 ampicillin), followed by counterselection for double-crossover deletion mutants in which the plasmid had been excised and was lost (10% sucrose resistant due to loss of the plasmid-carried sacB gene). The mutation was confirmed by PCR with primers rtxAF0 (5′-ATGGGGAAATTTATGATGGAG-3′) and rtxAR0 (5′-GCCAGGTTGGTAAGACTTTG-3′) and sequencing of the amplified product.

Mice.

Wild-type C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice were acquired from Charles River Laboratories. All mice were housed with food and water ad libitum and monitored in accordance with the rules of the Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine.

V. cholerae infection of infant mice.

Five- to 6-day-old C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice were orally infected with ca. 105 wild-type or mutant V. cholerae cells, taken from an LB agar plate into LB broth, or sham infected with LB broth carrier. Five microliters of food coloring per milliliter of infection mix was added to each infection mix in order to visually verify that the inoculum entered the stomachs of the mice. Each inoculum was serial diluted and plated for viable counts to check the infection dose. At 7 h, 24 h, or 30 h postinfection, small intestines were harvested for histology or RNA.

Immunization and challenge.

V. cholerae OMVs were prepared from strain E7946 and used to immunize 6-week-old BALB/c mice intranasally with 25-μg doses on days 0, 14, and 28, followed by mating (day 40) and challenge of infants born to and suckled by immunized mice, as described previously (35). V. cholerae challenge was carried out as described above, except where hyperinfectious mouse-passaged challenge was used, which was carried out as described previously (36), with details as follows. For hyperinfectious challenge, naïve infant mice were first infected with in vitro-grown V. cholerae as described above. At 24 h postinfection, small intestines were harvested and homogenized in 1 ml saline, and 2 or 3 homogenates were pooled, roughly filtered (100-μm pore size), and diluted 10-fold to give a ca. 1,000-CFU input dose in 50 μl. This infection mix was used to challenge neonates born to OMV-immunized or unimmunized control mice.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR).

Small intestines were snap-frozen and stored at −80°C until ready for RNA preparation. Frozen intestines were placed into 1 ml of TRIzol (Invitrogen) per 100 mg of tissue, 250 μl of 0.1-mm zirconia beads was added, and samples were homogenized by bead beating twice for 1 min, with 1 min on ice between beatings. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 2 min, the supernatant was removed from the beads. An equal volume of chloroform was added, mixed, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 2 min. The upper aqueous phase was decanted into a fresh tube, and 100% ethanol was added to give a final concentration of 35%. This solution was place onto an RNeasy column, centrifuged, washed, and eluted in 50 μl of RNase-free water, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). DNA was removed from the RNA by use of a DNAfree kit (Ambion), using the stringent protocol according to the manufacturer's instructions.

cDNA was prepared using 1 μg of RNA and random primers with iSCRIPT Select (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For each RNA sample, RT-negative controls containing RNase-free distilled water (dH2O) and 1 μg of RNA were prepared. For qRT-PCR, 1 μl of cDNA (or RT-negative control mix) was used in a 20-μl reaction volume with 300 nM (each) forward and reverse primers and 1× iQ SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad). PCRs were run on an MX3000P machine (Stratagene) under the following cycle conditions: 1 cycle of 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55 to 63°C (see Table 2 for the annealing temperature for each primer set) for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s; and 1 dissociation curve cycle of 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 55 to 63°C (as for amplification cycles) at 30 s, and 95°C for 30 s. Primers used are listed in Table 2. Each reaction was run in duplicate, plus an RT-negative control to determine background amplification. For each new primer set, standard curves created using a 2-fold dilution series of template (cDNA from infected mouse intestine for murine genes and genomic DNA for V. cholerae genes) were run, and PCR samples were separated in 2% agarose gels containing 1× GelGreen dye (Biotium) to determine whether the amplicon sizes (listed in Table 2) were correct. All primer sets had efficiencies of amplification of at least 93%. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) murine control gene was used to normalize qRT-PCR data for the test genes, and cycle threshold (CT) values were converted to relative transcript levels by using the 2−ΔΔCT method (37) and expressed relative to a calibrator sample.

TABLE 2.

Quantitative RT-PCR primers used in this study

| Gene | qRT-PCR primer sequence (5′ to 3′) |

cDNA amplicon size (bp) | Annealing temp (°C) | Reference or PrimerBank IDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||||

| Murine genes | |||||

| GAPDH | ACTCCCACTCTTCCACCTTC | TCTTGCTCAGTGTCCTTGC | 185 | 55 | 77 |

| KC | CTGGGATTCACCTCAAGAACATC | CAGGGTCAAGGCAAGCCTC | 117 | 55 | 6680109a1 |

| MIP-2 | CCACTCTCAAGGGCGGTCAAA | TACGATCCAGGCTTCCCGGGT | 189 | 55 | 78 |

| NOS-2 | ACATCGACCCGTCCACAGTAT | CAGAGGGGTAGGCTTGTCTC | 177 | 55 | 6754872a2 |

| IL-6 | GTTCTCTGGGAAATCGTGGAAA | AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATACA | 78 | 55 | 79 |

| IL-17a | CTCCAGAAGGCCCTCAGACTAC | GGGTCTTCATTGCGGTGG | 69 | 63 | 79 |

| TNF-α | ATGAGCACAGAAAGCATGATC | TACAGGCTTGTCACTCGAATT | 276 | 55 | 59 |

| IL-1β | TGCTTGTGAGGTGCTGATGTACCA | TGGAGAGTGTGGATCCCAAGCAAT | 137 | 60 | 80 |

| CCL20 | GCCTCTCGTACATACAGACGC | CCAGTTCTGCTTTGGATCAGC | 146 | 55 | 8394248a1 |

| Muc1 | GGCATTCGGGCTCCTTTCTT | TGGAGTGGTAGTCGATGCTAAG | 132 | 60 | 7305293a1 |

| IFN-γ | ATGAACGCTACACACTGCATC | CCATCCTTTTGCCAGTTCCTC | 182 | 63 | 33468859a1 |

| IL-10 | GCTCTTACTGACTGGCATGAG | CGCAGCTCTAGGAGCATGTG | 105 | 60 | 6754318a1 |

| V. cholerae genes | |||||

| 16S rRNA gene | CGTAAAGCGCATGCAGGTG | CTTCGCCACCGGTATTCCTT | 162 | 55 | 81 |

| ctxA | TTGTTAGGCACGATGATGGA | TGGGTGCAGTGGCTATAACA | 124 | 55 | 82 |

PrimerBank ID numbers are from the database at http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/.

IHC and IF staining of intestinal tissue.

Small intestines for immunohistochemistry (IHC) or immunofluorescence (IF) staining were dissected just below the stomach and included the cecum (not included for RNA analysis) for easy identification of the distal end of the small intestine. They were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde (BDH) in a jelly roll configuration between two histology sponges in a histology cassette for at least 24 h. Tissue was paraffin embedded, and 4-μm lateral sections were cut through the middle of the tissue. Samples were deparaffinized in xylene (twice for 5 min each) and then rehydrated by serial 5-min incubations in 100% (2 times), 90%, and 70% ethanol and, finally, in distilled water. All staining steps were carried out at room temperature. Tissue sections were surrounded by a hydrophobic pen, treated with 20 μg ml−1 proteinase K (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min for the purposes of antigen retrieval, and washed twice for 5 min each in PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). For IHC, samples were treated with peroxidase blocking solution (LSAB2 system-HRP; DakoCytomation) for 10 min and then rinsed with dH2O and placed into PBS. In all cases, samples were blocked with 5% goat serum plus 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS (block) for 1 h at room temperature.

For IF, samples were stained for 1 h with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-V. cholerae O1 mouse IgG1 antibody (250-fold dilution; ca. 10 μg ml−1) (New Horizons) plus a DNA stain (2 μg ml−1 Hoechst 33342; Molecular Probes) to reveal bacteria and tissue morphology and with a lectin that highlights mucus (2 μg ml−1 tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate [TRITC]-wheat germ agglutinin; Sigma-Aldrich). Alternatively, bacterial and DNA staining was combined with neutrophil staining, using anti-neutrophil rat IgG2a antibody 7/4 (Abcam) for 1 h and anti-rat IgG–TRITC (Jackson) secondary antibody for 30 min.

For IHC staining of neutrophils, anti-neutrophil rat IgG2a antibody 7/4 (Abcam) was used for C57BL/6 mice, and anti-neutrophil rat IgG2b antibody NIMP-R14 (Abcam) for BALB/c mice, with goat anti-rat IgG–biotin secondary antibody (DakoCytomation). Primary and secondary antibody incubations were done for 1 h and for 30 min, respectively, followed by streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 10 min and 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) plus HRP substrate for 5 min (LSAB2 system-HRP; DakoCytomation).

Washing after DAB-HRP incubation was carried out with dH2O in a squeeze bottle. Other washes were carried out 3 times for 5 min each in PBST. Finally, for IHC, samples were counterstained with Gill's hematoxylin (Polysciences, Inc.) for 2 min and washed in dH2O to remove excess dye and then in 1× automation reagent (Fisher Scientific) until blue. All antibodies were diluted in blocking solution for staining. Negative-control FITC-mouse IgG1 (Sigma) and rat IgG2a or IgG2b (Abcam), as appropriate, were used to stain consecutive sections in order to confirm the specificity of the staining.

IF-stained samples were mounted under a coverslip in mounting medium (2.4 g of Mowiol 488 [Calbiochem], 6 g of glycerol, 6 ml water), mixed, buffered with 12 ml of 0.2 M Tris, pH 8.5, heated to 50°C to mix, and clarified by centrifugation before addition of DABCO (1,4,-diazobicycli-[2.2.2]-octane; Aldrich) to 2.5% (wt/vol) to reduce fading of fluorophores. For IHC, samples were dehydrated in a reverse of the ethanol and xylene steps described above and then mounted under a coverslip in Poly-Mount xylene (Polysciences Inc.). Samples were viewed using a Nikon 80i microscope, and images were captured with NIS Elements software and processed with ImageJ software. Counting of stained cells or numbers of DNA clouds was carried out by individuals blinded to the identities of the samples, for the entire length of the small intestine for one jelly-rolled section for each mouse.

Statistics.

The majority of data were not normally distributed, so nonparametric tests were utilized: Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare two groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis test and post hoc Dunn's multiple-comparison test were used for more than two groups. GraphPad Prism 5.0a was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Inflammatory markers observed by qRT-PCR in the infant mouse small intestine after V. cholerae infection.

We sought to determine whether the infant mouse model of acute V. cholerae colonization could be used to interrogate innate immune responses to V. cholerae in this genetically tractable host. We used C57BL/6 mice because many transgenic mice are available in this background for any subsequent studies of genetic susceptibility to inflammation in response to V. cholerae infection. We used qRT-PCR to screen for increased transcription of proinflammatory markers that are induced in response to V. cholerae infection in other infection models and/or in cholera patient samples upon wild-type V. cholerae infection. Transcription of chosen inflammatory markers was monitored in the small intestines of infant mice 7, 24, and 30 h after infection with wild-type V. cholerae strain E7946 (O1 Ogawa El Tor) and in sham vehicle-infected controls.

We looked for the Muc-1 transcript, as it is a cell-associated mucin whose expression is induced during acute cholera in patient biopsy specimens (26). We tested for induction of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β because their transcript and protein levels were increased in epithelial cell lines in response to V. cholerae or pure V. cholerae flagellin (IL-1β) (15, 38) and in infant rabbits in response to oral V. cholerae infection (IL-1β and TNF-α were flagellin dependent) (16). IL-6 is also induced in adult mouse V. cholerae infection models (39, 40), and TNF-α is increased in sera of mice infected with V. cholerae via the pulmonary route (21). Importantly, IL-1β and TNF-α were also elevated in acute cholera patient biopsy specimens (26, 41). We looked at the chemokine CCL20 (also known as MIP-3α), which signals to recruit dendritic cells in response to proinflammatory mediators, including flagellin (42), as CCL20 was increased in sera of adult mice after pulmonary V. cholerae infection (21).

We also tested for the following murine IL-8 family chemokines, which signal for recruitment of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs; also known as neutrophils) to sites of infection: KC (also known as mCXCL1) and macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2; also known as mCXCL2). The MIP-2 level was increased in sera of mice infected with V. cholerae via the pulmonary route (21) and in adult mouse oral infection models (39, 40). Human IL-8 and the related chemokines Groα and Groβ were induced in epithelial cell lines in response to V. cholerae (38, 43), and IL-8 was induced in infant rabbits in response to oral V. cholerae, in a flagellin-dependent manner (16). We monitored transcription of the antibacterial factor NOS-2 (also known as inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS]), as increased NO metabolites were detected in sera of V. cholerae-infected volunteers (44) and cholera patients (7, 45). The cytokine IL-17a, which in adults would lead to a Th17 T-cell response, was monitored. Although IL-17a is produced by Th17 T cells, which are not yet fully developed in neonates, it is also produced by innate immune cells, which are likely to be present in neonates (46). In addition to the above, we looked at gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and IL-10, as examples of classic Th1-inducing and anti-inflammatory cytokines, respectively, and because IL-10 was seen to be modestly induced in an adult mouse model of infection (39).

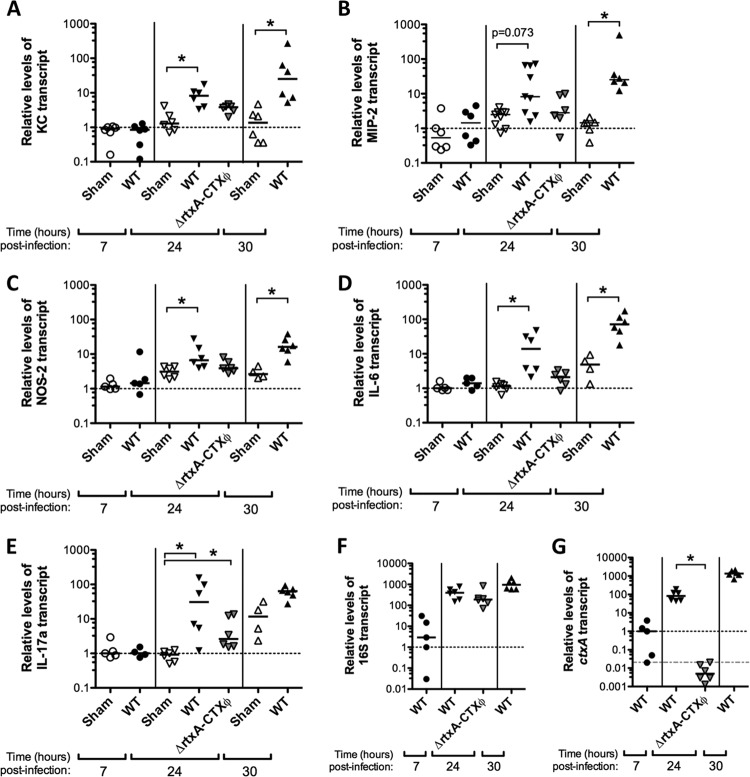

At 24 and 30 h postinfection, we observed higher transcription levels after V. cholerae infection than in sham-infected controls for five proinflammatory markers: KC, MIP-2 (statistically significant only at 30 h), NOS-2, IL-6, and IL-17a (statistically significant only at 24 h) (Fig. 1A to E). At 7 h postinfection, there was no significant difference in transcription of any of the proinflammatory markers tested compared to that in sham-infected controls (Fig. 1A to E; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Transcription of TNF-α, IL-1β, CCL20, Muc1, IFN-γ, and IL-10 was not significantly higher in V. cholerae-infected samples than in sham-infected controls at any time point tested (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Colonization was monitored by qRT-PCR analysis of the V. cholerae 16S rRNA gene (Fig. 1F) and ctxA (Fig. 1G). All V. cholerae-infected samples were similarly colonized at 24 to 30 h postinfection (Fig. 1F). At 7 h postinfection, the V. cholerae burden was not yet maximal, and the 16S rRNA gene signal was much lower and more variable than that at 24 h (Fig. 1F), consistent with intestinal CFU data obtained in separate experiments (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Inflammatory markers induced in infant mice after infection with wild-type V. cholerae and comparison with ΔrtxA-CTXϕ infection. qRT-PCR was carried out with cDNA from infant C57BL/6 mouse whole small intestine tissue 7, 24, or 30 h after oral sham infection with buffer (sham) or after infection with ca. 105 wild-type V. cholerae E7946 (WT) or E7946 ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain Bah-2 (ΔrtxA-CTXϕ) organisms, as indicated. KC (A), MIP-2 (B), NOS-2 (C), IL-6 (D), and IL-17a (E) were significantly induced by wild-type V. cholerae at 24 and/or 30 h postinfection, but not at the 7-h time point. Relative levels of infection were monitored by qRT-PCR analysis of the 16S rRNA gene (F), and the presence or absence of cholera toxin expression was determined by qRT-PCR analysis of ctxA (G). All data were normalized to expression of the GAPDH murine housekeeping gene and expressed relative to a 7-h sham-infected (A to E) or WT-infected (F and G) calibrator sample, indicated by the dotted lines. In panel G, the gray dashed line shows the highest nonspecific ctxA amplification signal observed for ΔctxA strain-infected samples. Each symbol represents one mouse, and horizontal bars indicate medians. *, P < 0.05 for comparisons made within each time point (two groups compared by Mann-Whitney U test or three groups compared with Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's multiple-comparison tests). Data for two IL-17a samples (one WT 7-h sample and one sham 30-h sample) with unusually low GAPDH control gene amplification and IL-17a levels below the limit of detection (below RT-negative control levels) were excluded from the data presentation and analysis.

Neutrophil recruitment in the infant mouse small intestine after V. cholerae infection.

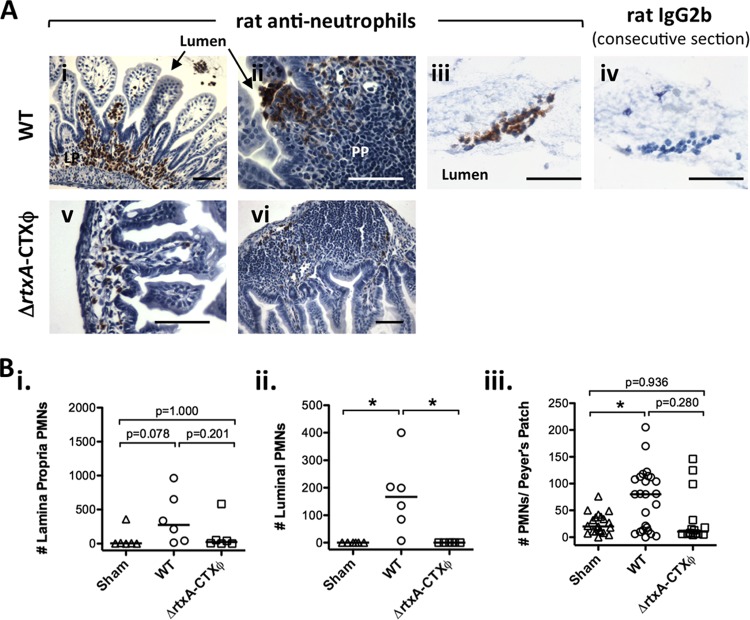

Consistent with transcriptional activation of the MIP-2 and KC chemokines, which attract PMNs (Fig. 1A and B), a higher median level of PMNs was seen by immunohistochemical staining 24 h, but not 2 h or 7 h, after infection with V. cholerae (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Numbers of PMNs were counted in Peyer's patches, the lamina propria, and the lumen of the small intestine. We never detected luminal PMNs in sham controls, whereas there were a significant number of PMNs in the lumen 24 h after infection (Fig. 2B, panel ii). There was also an increase in PMNs in Peyer's patches and the lamina propria (Fig. 2B, panels i and iii). Recruitment of PMNs to the lamina propria did not reach statistical significance in this particular experiment (Fig. 2B, panel i) but was statistically significant in subsequent experiments (compare sham and WT data in Table 3). There was wide variation in PMN numbers between Peyer's patches within an individual, with larger PMN numbers toward the distal (ileum) end of the intestine than toward the proximal (duodenum) end (Fig. 2B, panel iii, and data not shown). At the apical edge of the epithelium, overlying Peyer's patches and some regions of the lamina propria, PMNs were caught in the process of exiting the tissue and entering the lumen (for example, see Fig. 2A, panel ii). On a mouse-by-mouse basis, there was a significant positive correlation between the number of PMNs in the lamina propria and the number in the lumen (Spearman rank correlation P < 0.0001; r = 0.8807; 95% confidence interval, 0.7543 to 0.9441).

FIG 2.

Neutrophil infiltrates in the small intestines of infant mice after infection with wild-type or ΔrtxA-CTXϕ V. cholerae. C57BL/6 infant mice were orally infected with ca. 105 V. cholerae E7946 (WT) or E7946 ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain Bah-2 (ΔrtxA-CTXϕ) organisms or sham infected (sham), as indicated. Small intestines were harvested at 24 h postinfection and stained for PMNs. (A) Examples of staining for PMNs (i to iii, v, and vi) or with negative-control rat IgG2b (iv) after infection with WT (i to iv) or ΔrtxA-CTXϕ (v and vi) V. cholerae. LP, lamina propria; PP, Peyer's patch. Bars = 25 μm. (B) Blinded counts of PMNs in the lamina propria (i) and the lumen of the small intestine (ii) and the number of PMNs per Peyer's patch (iii) for a 4-μm section of the entire small intestine for each mouse. Each symbol represents one mouse (i and ii) or one Peyer's patch (iii); horizontal bars show medians. *, P < 0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's multiple-comparison tests).

TABLE 3.

Viable counts and quantification of PMNs for C57BL/6 infant mice infected with wild-type V. cholerae or one of three deletion mutants

| Time point and infection type | Median value (interquartile range)h |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of CFU/small intestine | No. of PMNs/Peyer's patch | No. of lamina propria PMNs | No. of luminal PMNs | |

| 24 h postinfection | ||||

| Sham | NA | 4 (0.5–9) | 11 (6–13) | 0 (0–0) |

| WT | 3.4 × 107 (1.4 × 107–1.6 × 108) | 98 (40–121)* | 134 (99–760)* | 872 (418–1,823)* |

| ΔrtxAa,e | 1.1 × 108 (4.9 × 107–3.4 × 108)ns | 50 (32–110)*,ns | 547 (196–690)*,ns | 916 (233–2,444)*,ns |

| Sham | NA | 21 (12–29) | 16 (13–82) | 0 (0–0) |

| WT | 7.6 × 107 (4.0 × 107–1.0 × 108) | 134 (60–184)* | 586 (424–1,800)* | 438 (70–1,348)* |

| ΔhlyAb,f | 1.3 × 107 (7.0 × 106–4.7 × 107)† | 103 (30–163)*,ns | 431 (64–1,048)*,ns | 58 (0–260)*,ns |

| Sham | NA | ND | ND | ND |

| WT | 7.7 × 107 (2.7 × 107–1.1 × 108) | ND | ND | ND |

| ΔDNasec | 2.3 × 107 (6.5 × 106–5.8 × 107)† | ND | ND | ND |

| 30 h postinfection | ||||

| Sham | NA | 34 (20–49) | ND | 0 (0–0) |

| WT | 2.9 × 108 (2.3 × 108–4.3 × 108) | 112 (81–118)* | ND | 637 (207–1,644)* |

| ΔDNased,g | 1.5 × 108 (1.4 × 108–3.2 × 108)† | 81 (54–106)*,ns | ND | 432 (8.5–1,050)nsig, ns |

n = 6 mice for CFU data, from one experiment only.

n = 12 mice for CFU data, from two experiments.

n = 28 mice for CFU data, from three experiments.

n = 6 mice for CFU data, from one experiment only.

n = 5 mice for PMN counts, from one experiment only.

n = 9 mice for PMN counts, from two experiments.

n = 5 mice for PMN counts, from two experiments.

†, P < 0.05 compared to the WT, using the Mann-Whitney U test (CFU data); ns, no significant difference compared to the WT (Mann-Whitney U test for two groups [CFU data] or Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's multiple-comparisons tests for three groups [PMN counts]); *, P < 0.05 compared to sham-infected controls (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's multiple-comparison tests); nsig, no significant difference compared to sham-infected controls (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's multiple-comparison tests); NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

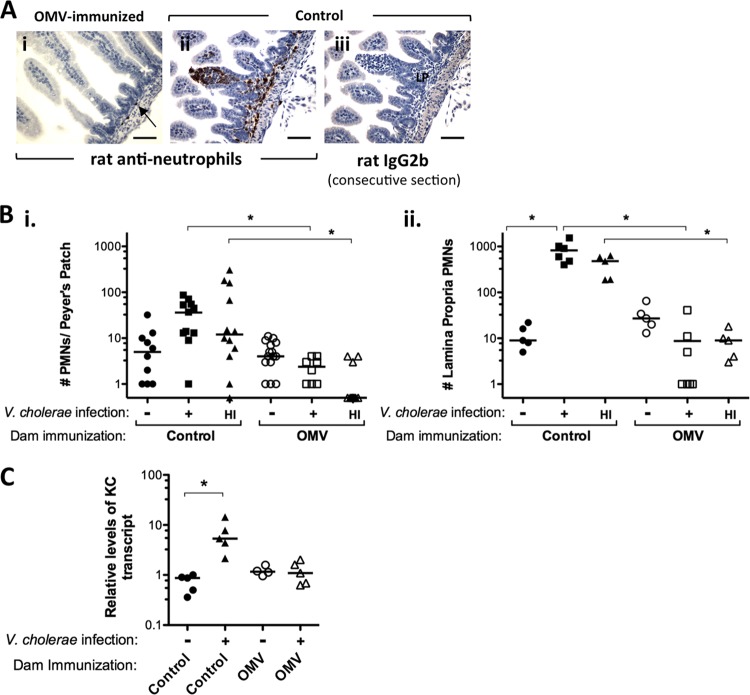

In addition to C57BL/6 mice, two other mouse strains (CD-1 and BALB/c) were tested for a PMN recruitment phenotype at 24 h postinfection. We note that in some experiments BALB/c pups were returned to their dams postinfection, as part of a dam vaccination and neonatal protection study, whereas C57BL/6 and CD-1 mice were not. Returning or not returning pups to their dams postinfection had no significant effect on colonization of CD-1 or BALB/c mice (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). An increase in Peyer's patch PMNs was seen for both CD-1 and BALB/c mice in response to V. cholerae infection, but this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3B, panel i, pups born to control dams, and data not shown). For BALB/c mice, a significant increase in recruitment of PMNs to the lamina propria was observed (Fig. 3A, panel ii, and B, panel ii, pups born to control dams, and data not shown). Unlike our observations in C57BL/6 mice, 24 h after infection with V. cholerae, PMNs were not observed in the small intestinal lumen in significant numbers for CD-1 or BALB/c mice (data not shown). We concluded that the most dramatic inflammatory response was observed in the inbred C57BL/6 strain of mice, which is also the background for many transgenic mouse strains, making them the model of choice for these studies.

FIG 3.

OMV immunization protects mice from inflammation upon V. cholerae challenge. Images of PMN staining (A), PMN counts in Peyer's patches (i) and lamina propria (ii) (B), and levels of KC transcript determined by qRT-PCR (C) are shown for the small intestines of BALB/c pups 24 h after infection with LB-grown V. cholerae or fecal hyperinfectious V. cholerae from infected naïve mice (HI). Data are shown for pups born to either sham (control) or OMV-immunized (OMV) dams. Panels A and C show data only for LB-grown V. cholerae infections. The LB-grown infection dose was ca. 105 CFU, and the HI infection dose range was 2,640 to 9,350 CFU, which are both at least 500 times the 50% infectious dose (ID50). (A) PMN (neutrophil) staining (i and ii) or staining with control rat IgG2b for a consecutive section (iii) for infected pups suckled by OMV-immunized (i) or control (ii and iii) dams. The arrow shows a rare PMN in the lamina propria of an infected pup suckled by an OMV-immunized dam. LP, lamina propria. Bars = 25 μm. In panel Bi, PMN numbers below the detection limit are shown with a value of 0.5. Each symbol represents one mouse (Bii and C) or one Peyer's patch (Bi). The horizontal bars in panels B and C indicate the medians. *, P < 0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's multiple-comparison tests).

A different wild-type V. cholerae strain (O1 Inaba El Tor strain A1552) was compared with E7946 and was found to induce comparable levels of PMN recruitment to Peyer's patches, the lamina propria, and the lumen of the small intestine in infected C57BL/6 infant mice (data not shown).

In contrast to the observed recruitment of PMNs, a macrophage marker (F4/80) revealed similar numbers of stained cells in sham- and V. cholerae-infected small intestinal samples at 24 h postinfection (data not shown). These macrophages were almost exclusively in the lamina propria (data not shown).

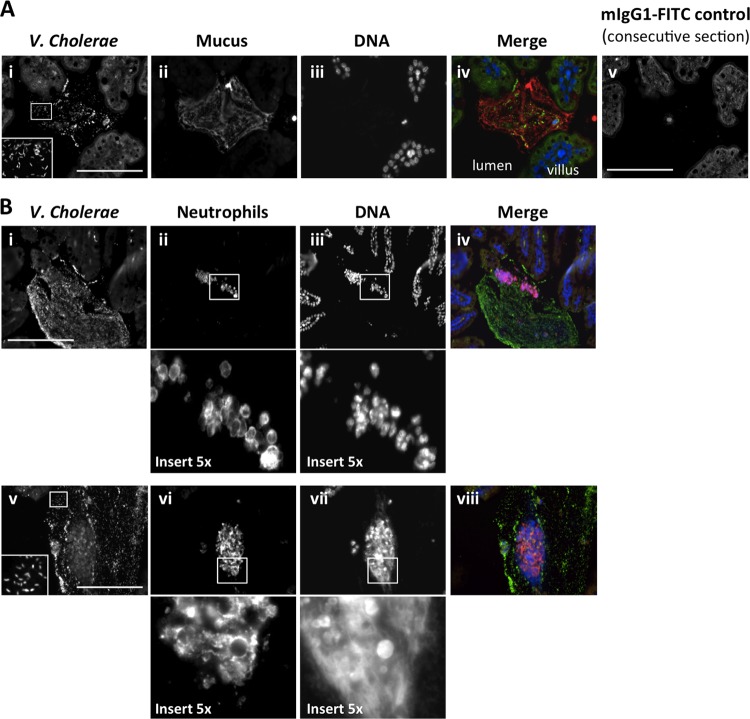

We were interested in the spatial relationship between luminal PMNs, V. cholerae, and mucous blobs where we previously found V. cholerae in BALB/c mice (36). Staining for V. cholerae, DNA, and mucus (using the lectin wheat germ agglutinin, which recognizes GlcNAc sugars that are prevalent in mucus) at 24 h postinfection showed many V. cholerae organisms within the lumen, often closely association with large blobs of mucus, in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4A), outbred CD-1 mice (data not shown), and BALB/c mice (36; data not shown). We then costained for V. cholerae, DNA, and Ly6G, which is on the cell membrane of PMNs. In C57BL/6 mouse intestines at 24 h postinfection, when luminal PMNs were abundant, we observed that PMNs in the lumen were also associated with large blobs covered in V. cholerae (Fig. 4B). In many cases, the multilobed nuclei of the PMNs were intact, suggesting that these cells had been alive and in close association with V. cholerae in the small intestinal lumen when the tissue was fixed (for instance, see Fig. 4B, panels i to iv). Interestingly, we also observed more diffuse anti-PMN antigen staining and clouds of stringy DNA in some of the blobs covered in V. cholerae, which may have been derived from dead neutrophils (for instance, see Fig. 4B, panels v to viii). These look very much like NETs, which were recently shown to be induced by V. cholerae combined with neutrophils in vitro (40) but could not be visualized in vivo with the adult mouse model used in that study. Therefore, we have uncovered a plausible model in which to visualize NETs induced by V. cholerae in vivo.

FIG 4.

V. cholerae in the intestinal lumen is associated with clouds of mucus that also contain neutrophils and, in some cases, extracellular DNA. C57BL/6 infant mice were orally infected with ca. 105 V. cholerae E7946 organisms. (A) Small intestines were harvested at 24 h postinfection and stained for localization of V. cholerae with respect to tissue and mucus, using anti-V. cholerae mouse IgG1–FITC (i), wheat germ agglutinin-TRITC to highlight GlcNAc sugars that are prominent in mucus (ii), and Hoechst stain for DNA (iii). (B) Alternatively, tissue was stained to investigate the juxtaposition of bacteria, DNA, and PMNs in the intestinal lumen by staining for V. cholerae (i and iv), PMNs by use of rat anti-mouse neutrophil 7/4 antibody and anti-rat IgG–TRITC (ii and vi), and DNA (iii and vii). A merge of all three images is also shown in each case (A, panel iv, and B, panels iv and viii). An example of a consecutive section stained with an mIgG1-FITC negative control is presented to show the level of nonspecific background obtained in the FITC (V. cholerae) channel. Bars = 25 μm.

In a ΔCTX background, either CTXϕ itself or rtxA contributes to inflammation, but in a wild-type background, rtxA and hlyA do not.

Having found that V. cholerae induces neutrophil recruitment and a subset of proinflammatory factors in infant C57BL/6 mice at 24 to 30 h postinfection, we investigated bacterial factors that could contribute to the induction of inflammation. The toxins HlyA and RtxA are encoded within the genomes of all V. cholerae strains, regardless of whether they have acquired CTXϕ, and have been implicated in inflammation with epithelial cells in vitro and in adult mouse models of V. cholerae infection (19, 21, 22, 28). Mutants deleted for genes encoding RtxA or HlyA were investigated for PMN recruitment in infant mice. Intestinal viable counts revealed similar (ΔrtxA) or slightly but statistically significantly less (ΔhlyA) colonization than that of wild-type V. cholerae (Table 3). Both the ΔrtxA and ΔhlyA strains induced recruitment of PMNs to Peyer's patches, the lamina propria, and the intestinal lumen, to levels significantly above those in sham-infected controls and not significantly different from those in WT infections (Table 3). Therefore, we concluded that neither RtxA nor HlyA, despite a slight reduction in colonization for the ΔhlyA strain, contributes to the initiation of an inflammatory response leading to the recruitment of PMNs in a wild-type background in this model.

We also interrogated a strain of E7946 called Bah-2, which is deleted for both tandem copies of CTXϕ present in wild-type E7946 and for 1.9 kbp from the 3′ end of rtxA, which we refer to as the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain (17, 20, 47). We note that the CtxAB, Zot, and Ace toxins and the Cep colonization factor are all encoded within CTXϕ (48). Colonization, determined by V. cholerae 16S rRNA gene levels, was not significantly different for the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain compared with WT E7946, suggesting that cep does not strongly influence colonization (Fig. 1F). High levels of the ctxA transcript were seen for WT V. cholerae at 24 to 30 h postinfection, with a low level at 7 h postinfection (Fig. 1G). A low level of nonspecific background amplification was detected with ctxA primers for samples after ΔrtxA-CTXϕ infection (shown as a gray dotted line in Fig. 1G), which was also detected in sham infection samples (data not shown).

Unlike WT V. cholerae infection, ΔrtxA-CTXϕ infection did not induce KC, IL-6, and NOS-2 significantly above those in the sham-infected controls, although differences between WT and ΔrtxA-CTXϕ infections did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1A, C, and D). ΔrtxA-CTXϕ infection induced IL-17a transcription significantly above that in sham-infected controls, but less than that with WT V. cholerae, although the difference between ΔrtxA-CTXϕ and WT infections, again, was not statistically significant (Fig. 1E). These data suggest that innate cells responsible for making IL-17a in infant mice responding to V. cholerae infection are less influenced by rtxA or CTXϕ-encoded factors than are the cells producing MIP-2, IL-6, and NOS-2, but in all cases, inflammatory signals induced by WT V. cholerae are less strongly induced by the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain.

Consistent with lower KC and MIP-2 levels induced by infection with V. cholerae ΔrtxA-CTXϕ (Fig. 1A and B), fewer PMNs were observed with this strain than with WT V. cholerae infection (Fig. 2). This trend was seen in the lamina propria (Fig. 2B, panel i) and Peyer's patches (Fig. 2B, panel iii), but the difference between WT and ΔrtxA-CTXϕ infections was statistically significant only for numbers of luminal PMNs, as zero luminal PMNs were found after ΔrtxA-CTXϕ infection, just like in the sham infection controls (Fig. 2B, panel ii). We concluded that either a gene carried by CTXϕ contributes to PMN recruitment in infant mice infected with V. cholerae or RtxA has a much greater influence on inflammation in the absence of CTX than in a wild-type background, with the most profound effect being upon translocation of PMNs into the intestinal lumen.

Extracellular V. cholerae DNases do not influence recruitment of PMNs but reduce what appear to be NETs in the lumen.

Another mutant tested in these studies was deleted for two genes encoding extracellular DNases (xds/VC2621 and dns/VC0470) that are secreted by V. cholerae and work together to contribute to biofilm structure, nutrition in biofilms, and dissolution of biofilms to aid infection (49, 50). Dns also contributes to natural transformation (51). We chose to use a double mutant because in most phenotypes the two appear to work together, despite somewhat different expression profiles and enzymatic activities (50). This mutant was interesting to us regarding PMN recruitment, firstly because xds is induced during infection in infant mice at time points that coincide with the appearance of PMNs (>7 h and <24 h) (52). Secondly, we observe the appearance of what could be NET-like DNA clouds in response to wild-type V. cholerae infection (Fig. 4B, panel vii), and it was recently shown that V. cholerae can induce NETs in vitro that are disrupted by the DNases and that, in an adult mouse model, the DNases are required to maintain V. cholerae colonization in the presence of neutrophils, but not when neutrophils are depleted (40).

First, we tested colonization of the ΔDNase mutant. With C57BL/6 mice, we observed slightly less but statistically significant colonization of the ΔDNase mutant compared to WT V. cholerae at 24 h postinfection (Table 3). We had a high n value (n = 28) for this experiment, due in part to unusually large litters and to a third independent experiment carried out because of a lack of consistency between the first two experiments. At 30 h postinfection, a smaller experiment did not show any difference between WT and ΔDNase mutant small intestinal CFU and gave much more consistent CFU values (Table 3). Previous reports did not show a difference for WT V. cholerae (using different strains from that used here) compared to double DNase mutants in the infant mouse, using survival as a readout (49), or in viable counts for planktonic cells from within competition assays of biofilm versus planktonic cells (see Fig. S10 in reference 50). In a competition assay of our own with planktonic cells (using a lacZ-negative WT strain), we did not observe any significant difference in colonization between the WT and ΔDNase strains (median competition index, 0.88; interquartile range, 0.84 to 1.05; not significantly different from 1 by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

We decided to use the 30-h time point to look at PMN numbers for the ΔDNase strain, as this had given the highest and most consistent CFU values for the ΔDNase strain. We found that numbers of PMNs recruited to Peyer's patches by the ΔDNase strain were similar to those recruited after WT infection and, like the case with the WT, were significantly greater than those in sham-infected controls (Table 3). In the lumen, after infection with the ΔDNase strain, detectable intact neutrophil numbers showed a wide spread from mouse to mouse, such that they were neither statistically significantly above those in sham controls, unlike those with WT infection, nor significantly different from those in WT infection (Table 3), suggesting a possible subtle phenotype at the visual limit of detection.

When we viewed triple staining of V. cholerae with PMNs and DNA, we again observed similar numbers of intact PMNs for the WT and ΔDNase infections. However, for the ΔDNase strain, we more often observed large clouds of DNA around the intact PMNs, similar to what we saw with WT infection (Fig. 4B, panel vii). For a small number of mice (n = 5) from two separate infections, we counted intact neutrophils and clouds of DNA and found the median number of clouds/intact PMN (interquartile range) to be 0.0034 (0.00035 to 0.011) for the WT and 1.00 (0.00 to 9.00) for the ΔDNase strain. This suggests a trend toward more DNA clouds in ΔDNase infections, consistent with in vitro studies (40), but with this small data set this difference did not reach statistical significance (Mann-Whitney U test).

Immunization protects mice from inflammation upon V. cholerae challenge.

Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) released by V. cholerae can be used as a mucosal vaccine given to adult mice that, through antibodies in milk, will protect suckling neonates from infection upon V. cholerae challenge (33). We investigated whether the lack of small intestinal colonization in neonates suckled by OMV-immunized mice correlates with a lack of inflammatory infiltrate upon challenge with V. cholerae. BALB/c mice were used for this study, as the OMV vaccine has been studied extensively with this strain of mice (33, 35, 36, 53). At 2 to 7 h postinfection, as with C57BL/6 mice, neither pups from control sham-immunized dams nor those from OMV-immunized dams showed any PMN infiltrate (data not shown). At 24 h postinfection, PMNs were recruited to Peyer's patches (although this did not reach statistical significance compared to sham-infected controls) and the lamina propria. Pups suckled by OMV-immunized mice were protected from inflammatory PMN infiltrate upon challenge compared to those suckled by control mice (Fig. 3A, panel i, and B), even if the challenge was with hyperinfectious mouse-passaged V. cholerae (Fig. 3B, HI data), which is highly infectious, to a degree similar to that of V. cholerae in rice-water stool from cholera patients (54). A significant increase in the KC chemokine at 24 h postinfection was seen in V. cholerae-infected BALB/c mice suckled by control dams compared to uninfected littermates, which was not detected in infected pups suckled by OMV-immunized dams (Fig. 3C). Lack of KC induction is consistent with the visible lack of PMN recruitment in challenged pups born to OMV-immunized dams. Thus, it appears that suckling from immunized dams not only protects infant mice from colonization by V. cholerae (35, 53), even upon challenge with hyperinfectious host-passaged bacteria (36), but also protects them from infection-associated inflammation in an infant mouse model (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Although cholera is not a disease whose pathology is driven by inflammation, an innate immune response is induced in the small bowel in both infected patients (7, 26, 41) and volunteers colonized by CTX-negative strains (12). Here we observed, for the first time, an innate immune response to V. cholerae infection in the infant mouse model of acute infection. We detected the induction of KC and MIP-2, chemokines that attract PMNs, and the resultant recruitment of PMNs to the gut at the peak of V. cholerae infection (24 to 30 h postinfection). This is consistent with the detection of neutrophil markers in the stools of experimentally V. cholerae-infected volunteers (12) and cholera patients (7) and an increase in both neutrophils themselves and neutrophil markers in acute cholera patient biopsy samples (41, 55).

Neutrophils act as a first line of innate immune defense. When they are activated, PMNs produce chemokines that in turn recruit other innate immune cells, such as macrophages (56). In the infant mouse model, we did not see any change in macrophage numbers in response to V. cholerae infection. The activation state of macrophages that were present may have changed in response to infection, but we did not specifically interrogate this issue.

The localization and number of neutrophils in infected infant mice varied depending upon the mouse strain and were relatively patchy in all strains. Because of the patchiness of the phenotype, we looked at the histology of lateral sections of the entire length of the infant mouse small intestine and took RNAs from whole small intestines. Outbred CD-1 mice gave the least dramatic phenotype, with only a small increase in Peyer's patch PMNs, which was not statistically significant above the level in uninfected controls. Historically, CD-1 is the most commonly used infant mouse strain for V. cholerae infections, as these mice give large litters and have a calm temperament (30), but it would not be a good model for studying PMN recruitment in response to V. cholerae. CD-1 and BALB/c mice had significantly lower bacterial burdens at 24 h postinfection than C57BL/6 mice, even with a higher bacterial dose for CD-1 and BALB/c infections (see Fig. S2B and C in the supplemental material). It is possible that this higher intestinal burden is what leads to greater PMN recruitment in C57BL/6 mice. In an adult mouse model of V. cholerae infection, C57BL/6 mice were found to be more susceptible to colonization than CD-1 mice, which the authors hypothesized could be due to the larger size of the CD-1 mice (22). We observed that CD-1 pups are significantly larger than C57BL/6 pups at the same age, but they are also larger than BALB/c pups, suggesting a lack of correlation between size and V. cholerae intestinal burdens (data not shown). We tested the size variable with smaller CD-1 pups (1 day younger than usual) and larger C57BL/6 pups (day 6, as usual for infection, but stratified by size) and did not find any difference in susceptibility to colonization with size, only with strain (data not shown). C57BL/6 was the only mouse strain that we tested in which a large number of PMNs were observed in the intestinal lumen. C57BL/6 mice also gave the most robust responses in the lamina propria and Peyer's patches, although significant responses were also seen in BALB/c mice. In the infant rabbit model of infection, heterophils (the equivalent of neutrophils) were observed in ileal tissue for only about half of the rabbits infected with WT V. cholerae (actual numbers of heterophils were not reported) (57), suggesting that the C57BL/6 infant mouse model has a more reproducible PMN recruitment phenotype than that of the rabbit model.

We observed significant increases in a subset of innate immune factors, i.e., KC, MIP-2, NOS-2, IL-6, and IL-17a, in the neonatal mouse in response to V. cholerae infection compared to uninfected controls. This is rather surprising, as many neonatal innate immune responses have been shown to be lower than those in adult mice, including IL-6, IL-17a, and KC levels (58–60). However, this deficit does not apply to all situations, as one report showed elevated innate immune responses to high levels of LPS or to viral infection in neonates compared to adult mice (61). V. cholerae infection of antibiotic-treated adult mice induced modest increases (<10 times) in IL-6, MIP-2, and KC compared to the levels in uninfected controls (40). In the ketamine-dependent adult mouse model, induction of IL-6 and MIP-2 was observed after wild-type infection (39), but there was no increase in NOS-2 or IL-17a. While many cytokines are reportedly reduced in neonates compared to adult mice, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was increased (58, 60). We did not see a detectable change in IL-10 in response to V. cholerae infection in neonatal mice, whereas a small but significant increase was observed in an adult mouse model (39). We did not detect any increase in TNF-α, IL-1β, or IFN-γ in response to V. cholerae in neonatal mice, which is consistent with a lack of induction of IL-1β and TNF-α in an adult mouse V. cholerae infection model (39).

The role of PMNs in controlling V. cholerae infection has been interrogated using antibody-mediated depletion in adult mouse models of V. cholerae colonization. First, with ketamine treatment to facilitate prolonged small intestinal colonization, a model that is thought to mimic nonacute or asymptomatic infections or possibly the very early stages of infection prior to the onset of symptoms, and a nontoxigenic (no CTX) strain, as inflammation in this model does not require CTX (22, 28), increased systemic spread of V. cholerae was found in neutropenic mice with high doses (29). Also, neutropenia negated the essential role of the accessory toxins to maintain colonization, suggesting a role for PMNs in containment of bacteria to the intestine and that accessory toxins attempt to combat the PMNs (29). In contrast, with a toxigenic strain in adult mice, using two different models, there was little difference in colonization and/or survival rates between immunocompetent and neutropenic mice (39, 40). With high infection doses, neutropenic mice actually did better than immunocompetent mice, and it was suggested that “CT may modulate the host response to promote colonization, thereby enhancing virulence, in a process that is dependent upon the influx of neutrophils” (39). Depletion of PMNs from infant mice before infection could address their role in controlling V. cholerae numbers in an acute model of infection, but we have not determined the technical feasibility of such a study (there is only a 4- to 6-day window after birth during which infant mice are fully susceptible to colonization).

In the infant mouse model, we observed PMNs caught in the act of exiting the intestinal tissue from the apical side of Peyer's patches and the lamina propria in order to enter the lumen. In C57BL/6 mice, we also observed many PMNs in the lumen itself and a positive correlation between lamina propria and luminal PMN numbers. The reason that luminal PMNs are observed more commonly in C57BL/6 mice than in the other two strains tested is unknown. During infant rabbit V. cholerae infection, it was also observed that heterophils were present in both the colonic digesta and the lamina propria (16), consistent with heterophils having crossed into the intestinal lumen in order to make their attack upon the noninvasive pathogen V. cholerae. Increased markers of PMNs have been detected in stools of infected individuals (7), but intact PMNs have not been observed directly in the intestinal lumen in patients. Technical and ethical limitations would make this difficult, as the only readily accessible human samples for analysis are intestinal biopsy specimens or rice-water stool after it has exited the patient. Studies where rice-water stool was interrogated microscopically did not detect intact PMNs, but the cells may simply not survive exit from the host (62, 63). We note that Gangarosa et al. did not see PMNs in centrifuged rice-water stool components, but in this particular study, they did not observe PMNs in intestinal biopsy samples either (62).

With the infant mouse model, we can interrogate bacterial factors responsible for PMN recruitment. We did not detect any influence of the HlyA or RtxA accessory toxin on PMN numbers in a CTX-positive strain background. With an adult mouse model, these accessory toxins are essential for persistence of a CTX-negative strain (22, 29) and also play a role in virulence upon infection with a CTX-positive strain (39). With the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain, we observed reduced inflammation. This could be due to the lack of CTX itself, or the lack of RtxA in a CTX-negative environment may be responsible. Adult mouse models suggest that RtxA is more likely to contribute to inflammation than CTX, as RtxA can contribute to inflammation in the absence of CTX in the pulmonary model (21), and inflammatory markers appear to be induced similarly with and without CTX during gut infection (note that CTX-positive and -negative results were reported in separate publications) (29, 39). HlyA and RtxA can act independently in an adult mouse model (22). It is possible that hlyA influences inflammation in the absence of CTX, but we have not yet compared a triple rtxA CTXϕ hlyA deletion strain with the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain in order to investigated this. In human volunteers, colonization by CTX-negative strains still induces inflammation (12); if reduced inflammation in response to ΔrtxA-CTXϕ infection compared to wild-type infection were proven to be due to a lack of CTX, rather than RtxA deletion in a CTX-negative background, this would suggest that the infant mouse is not an ideal model for the study of some aspects of innate immune responses to V. cholerae. Additional studies with a CTXϕ mutant with intact rtxA will be needed to determine the individual role of CTX in the system.

Deletion of the two V. cholerae genes encoding extracellular DNases did not have a strong influence on V. cholerae colonization in the infant mouse or on recruitment of PMNs to the site of infection. These two DNases together have been shown to contribute to the aquatic side of the V. cholerae life cycle and to transmission to new hosts by aiding in biofilm structure, using DNA as a nutrient in biofilms and dissociation of biofilms in order to aid colonization (50). More recently, a further role for these DNases inside the host, in the form of NET disruption, was detected in vitro and in an antibiotic-treated adult mouse model (40). NETs are composed of chromatin, with specific proteins from neutrophilic granules attached to the DNA, are produced by a novel form of programmed cell death, and can trap and/or kill both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (64). In an immunocompetent mouse model, Seper et al. found that the DNases are required for maintenance of colonization, whereas this is not the case in neutropenic mice, suggesting that the DNases combat the activity of neutrophils in this adult mouse model (40). Extracellular DNases have also been shown to combat NETs for group A streptococcus (65) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (66). We observed an intriguing increase in numbers of NET-like DNA clouds after infection with the double DNase mutant compared to WT infection, although this did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that the DNases may reduce the stability of NETs in the intestinal lumen in infected infant mice. Seper et al. were unable to directly view NETs in the adult mouse. With infant mice, because they are physically small, we are able to extract the entire small intestine with minimal disruption to the luminal contents. By taking lateral sections from the center of the tissue, we can view the entire length of the intestine and preserve structures in the lumen, such as blobs of mucus associated with V. cholerae bacteria and neutrophils, including diffuse and stringy DNA staining that resembles NETs. Thus, infant mice may serve as a model in which V. cholerae-induced NETs can be visualized in vivo.

We observed fewer PMNs in response to infection by the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain than with WT infection, with the most dramatic difference in the lumen of the intestine, where there were barely any PMNs after infection with the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain. We concluded that either the product of a gene(s) carried by CTXϕ is important for maximal PMN recruitment in infant C57BL/6 mice in response to V. cholerae infection or RtxA is more important in the absence of CTX (see above). In the small intestinal tissue of infant rabbits after infection with a V. cholerae ctxAB mutant, only a few heterophils were observed, but how this compared to wild-type V. cholerae infections was not reported (16). In infant mice in response to V. cholerae, in the absence of RtxA and CTXϕ, there is less induction of the KC and MIP-2 chemokines, resulting in slightly reduced PMN recruitment into the lamina propria and Peyer's patches compared to that with WT infection and in a more dramatic deficit in neutrophil exit into the lumen. More detailed genetic analysis will be required to dissect whether rtxA or a specific component of CTXϕ is responsible for these innate immune phenotypes. Cholera toxin itself is a possible contender, as CTXB has been shown to be proinflammatory by carrying LPS to the cytoplasm of cells, leading to intracellular caspase 11-dependent inflammasome activation (67). However, IL-1β induction would be indicative of inflammasome activation, and we did not see significant IL-1β induced by V. cholerae in infant mice. In contrast, in vitro CTX pretreatment can actually have an anti-inflammatory effect upon macrophages stimulated with LPS (68). The product of the neighboring gene, zot, could also be imagined to contribute to the dynamics of neutrophil exit into the lumen in response to infection, as it disrupts epithelial cell tight junctions in vitro (69). Interestingly, transmigration of PMNs into the lumen was found to induce IL-6 secretion by epithelial cells, which in turn enhances PMN granule release (70), and here we found that IL-6 was more strongly induced by WT V. cholerae than by the ΔrtxA-CTXϕ strain that induced less PMN migration into the gut lumen. Cholera toxin on its own delivered intranasally to adult mice induces a Th17-dominant response to coadministered antigen (71), but we did not find CTXϕ to be essential for IL-17a production by innate cells in infant mice in response to V. cholerae infection.

Although the presence of CTX is critical for V. cholerae to cause severe diarrhea, additional reactogenic components can cause mild diarrhea and inflammation after infection with CTX-negative strains (12). This additional reactogenicity has hampered the development of safe live attenuated vaccine strains, making the study of non-CTX proinflammatory factors important to cholera vaccine research. In adult mouse models of prolonged small intestinal colonization or the intranasal infection model, RtxA and HlyA are critical for colonization and inflammation. We did not see a contribution of these toxins to PMN recruitment in the infant mouse model of acute infection in the presence of CTX, but the role of RtxA in phenotypes observed in the CTX- and rtxA-negative background remains to be determined. It is possible that TLR4- and TLR5-induced signaling pathways play a role in PMN recruitment and cytokine signaling in the infant mouse model, although this was not investigated in this study.

OMV immunization of dams was found to provide passive protection from colonization to their neonates, and here we found that it also prevents inflammation upon V. cholerae challenge, as determined with the measures of PMN recruitment and associated KC induction. This suggests that the immune system of the neonate does not “see” antibody-bound V. cholerae. This is despite the presence of the FcRn (neonatal Fc receptor) IgG receptor, expressed in the gut in neonatal mice (72), and possibly IgA receptors on M cells, which are present in adult mice but whose presence in neonates is not known (73), that could potentially deliver antibody-bound bacteria to the gut-associated immune system. We note that the polymeric Ig receptor (pIgR), which binds to both IgA and IgM to be delivered into the gut lumen in adults (74), is not yet expressed in the neonatal gut, so it would not contribute to this system. The lack of an innate response to antibody-bound V. cholerae in the gut in neonates could have implications for the ability to colonize infants with live attenuated oral or killed oral V. cholerae vaccines. It is possible that oral immunization of infants breastfed by immunized or previously infected mothers may be ineffective, as antigen may never be “seen” by the infant's innate immune system when that antigen is antibody bound.

We envisage that our observation of PMN recruitment and innate cytokine responses in the infant mouse V. cholerae infection model will broaden the utility of this model for interrogating cholera host-pathogen interactions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by NIH grant AI055058, awarded to A.C., and A.C. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

We thank Lauren Richey and Derek Papalegis in the Animal Histology Core of the Research Animal Health and Pathology Support Laboratory, Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine, Tufts University, for their expert services of paraffin embedding and tissue sectioning.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 March 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00054-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. 2012. Cholera, 2011. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 87:289–304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. 2010. Cholera outbreak—Haiti, October 2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 59:1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910–1914. 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson E, Harris J, Morris JG, Calderwood SB, Camilli A. 2009. Cholera transmission: the host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:693–702. 10.1038/nrmicro2204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sansonetti PJ, Tran Van Nhieu G, Egile C. 1999. Rupture of the intestinal epithelial barrier and mucosal invasion by Shigella flexneri. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:466–475. 10.1086/515150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coburn B, Grassl GA, Finlay BB. 2007. Salmonella, the host and disease: a brief review. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:112–118. 10.1038/sj.icb.7100007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qadri F, Raqib R, Ahmed F, Rahman T, Wenneras C, Das SK, Alam NH, Mathan MM, Svennerholm A-M. 2002. Increased levels of inflammatory mediators in children and adults infected with Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 9:221–229. 10.1128/CDLI.9.2.221-229.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cash RA, Music SI, Libonati JP, Craig JP, Pierce NF, Hornick RB. 1974. Response of man to infection with Vibrio cholerae. II. Protection from illness afforded by previous disease and vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 130:325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine MM, Nalin DR, Craig JP, Hoover D, Bergquist EJ, Waterman D, Holley HP, Hornick RB, Pierce NP, Libonati JP. 1979. Immunity of cholera in man: relative role of antibacterial versus antitoxic immunity. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 73:3–9. 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90119-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine MM, Black RE, Clements ML, Cisneros L, Nalin DR, Young CR. 1981. Duration of infection-derived immunity to cholera. J. Infect. Dis. 143:818–820. 10.1093/infdis/143.6.818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan E, Calderwood SB, Qadri F. 2006. Live attenuated oral cholera vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 5:483–494. 10.1586/14760584.5.4.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva TM, Schleupner MA, Tacket CO, Steiner TS, Kaper JB, Edelman R, Guerrant R. 1996. New evidence for an inflammatory component in diarrhea caused by selected new, live attenuated cholera vaccines and by El Tor and O139 Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 64:2362–2364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xicohtencatl-Cortés J, Lyons S, Chaparro AP, Hernández DR, Saldaña Z, Ledesma MA, Rendón MA, Gewirtz AT, Klose KE, Girón JA. 2006. Identification of proinflammatory flagellin proteins in supernatants of Vibrio cholerae O1 by proteomics analysis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5:2374–2383. 10.1074/mcp.M600228-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison LM, Rallabhandi P, Michalski J, Zhou X, Steyert SR, Vogel SN, Kaper JB. 2008. Vibrio cholerae flagellins induce Toll-like receptor 5-mediated interleukin-8 production through mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-kappaB activation. Infect. Immun. 76:5524–5534. 10.1128/IAI.00843-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandyopadhaya A, Sarkar M, Chaudhuri K. 2008. IL-1beta expression in Int407 is induced by flagellin of Vibrio cholerae through TLR5 mediated pathway. Microb. Pathog. 44:524–536. 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rui H, Ritchie JM, Bronson RT, Mekalanos JJ, Zhang Y, Waldor MK. 2010. Reactogenicity of live-attenuated Vibrio cholerae vaccines is dependent on flagellins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:4359–4364. 10.1073/pnas.0915164107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor DN, Killeen KP, Hack DC, Kenner JR, Coster TS, Beattie DT, Ezzell J, Hyman T, Trofa A, Sjogren MH, Friedlander A, Mekalanos JJ, Sadoff JC. 1994. Development of a live, oral, attenuated vaccine against El Tor cholera. J. Infect. Dis. 170:1518–1523. 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin OS, Uddin T, Citorik R, Wang JP, Della Pelle P, Kradin RL, Bingle CD, Bingle L, Camilli A, Bhuiyan TR, Shirin T, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB, Finberg RW, Qadri F, Larocque RC, Harris JB. 2011. LPLUNC1 modulates innate immune responses to Vibrio cholerae. J. Infect. Dis. 204:1349–1357. 10.1093/infdis/jir544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ou G, Rompikuntal PK, Bitar A, Lindmark B, Vaitkevicius K, Wai SN, Hammarström M. 2009. Vibrio cholerae cytolysin causes an inflammatory response in human intestinal epithelial cells that is modulated by the PrtV protease. PLoS One 4:e7806. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin W, Fullner KJ, Clayton R, Sexton JA, Rogers MB, Calia KE, Calderwood SB, Fraser C, Mekalanos JJ. 1999. Identification of a Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin gene cluster that is tightly linked to the cholera toxin prophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:1071–1076. 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fullner K. 2002. The contribution of accessory toxins of Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor to the proinflammatory response in a murine pulmonary cholera model. J. Exp. Med. 195:1455–1462. 10.1084/jem.20020318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olivier V, Queen J, Satchell KJ. 2009. Successful small intestine colonization of adult mice by Vibrio cholerae requires ketamine anesthesia and accessory toxins. PLoS One 4:e7352. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haines GK, 3rd, Sayed BA, Rohrer MS, Olivier V, Satchell KJ. 2005. Role of Toll-like receptor 4 in the proinflammatory response to Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor strains deficient in production of cholera toxin and accessory toxins. Infect. Immun. 73:6157–6164. 10.1128/IAI.73.9.6157-6164.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon S, Mekalanos J. 2008. Decreased potency of the Vibrio cholerae sheathed flagellum to trigger host innate immunity. Infect. Immun. 76:1282–1288. 10.1128/IAI.00736-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larocque RC, Sabeti P, Duggal P, Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Lebrun LM, Harris JB, Ryan ET, Qadri F, Calderwood SB. 2009. A variant in long palate, lung and nasal epithelium clone 1 is associated with cholera in a Bangladeshi population. Genes Immun. 10:267–272. 10.1038/gene.2009.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flach C, Qadri F, Bhuiyan T, Alam N, Jennische E, Lonnroth I, Holmgren J. 2007. Broad up-regulation of innate defense factors during acute cholera. Infect. Immun. 75:2343–2350. 10.1128/IAI.01900-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nygren E, Li B, Holmgren J, Attridge SR. 2009. Establishment of an adult mouse model for direct evaluation of the efficacy of vaccines against Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 77:3475–3484. 10.1128/IAI.01197-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olivier V, Haines GK, 3rd, Tan Y, Satchell KJ. 2007. Hemolysin and the multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin are virulence factors during intestinal infection of mice with Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 strains. Infect. Immun. 75:5035–5042. 10.1128/IAI.00506-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Queen J, Satchell KJ. 2012. Neutrophils are essential for containment of Vibrio cholerae to the intestine during the proinflammatory phase of infection. Infect. Immun. 80:2905–2913. 10.1128/IAI.00356-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ujiiye A, Nakatomi M, Utsunomiya A, Mitsui K, Sogame S, Iwanaga M, Kobari K. 1968. Experimental cholera in mice. 1. First report on the oral infection. Trop. Med. 10:65–71 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrington DA, Hall RH, Losonsky G, Mekalanos JJ, Taylor RK, Levine MM. 1988. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili, and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J. Exp. Med. 168:1487–1492. 10.1084/jem.168.4.1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klose KE. 2000. The suckling mouse model of cholera. Trends Microbiol. 8:189–191. 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01721-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schild S, Nelson EJ, Bishop AL, Camilli A. 2009. Characterization of Vibrio cholerae outer membrane vesicles as a candidate vaccine for cholera. Infect. Immun. 77:472–484. 10.1128/IAI.01139-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61–68. 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schild S, Nelson EJ, Camilli A. 2008. Immunization with Vibrio cholerae outer membrane vesicles induces protective immunity in mice. Infect. Immun. 76:4554–4563. 10.1128/IAI.00532-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bishop AL, Tarique AA, Patimalla B, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Camilli A. 2012. Immunization of mice with Vibrio cholerae outer-membrane vesicles protects against hyperinfectious challenge and blocks transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 205:412–421. 10.1093/infdis/jir756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stokes NR, Zhou X, Meltzer SJ, Kaper JB. 2004. Transcriptional responses of intestinal epithelial cells to infection with Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 72:4240–4248. 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4240-4248.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Queen J, Satchell KJ. 2013. Promotion of colonization and virulence by cholera toxin is dependent on neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 81:3338–3345. 10.1128/IAI.00422-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seper A, Hosseinzadeh A, Gorkiewicz G, Lichtenegger S, Roier S, Leitner DR, Rohm M, Grutsch A, Reidl J, Urban CF, Schild S. 2013. Vibrio cholerae evades neutrophil extracellular traps by the activity of two extracellular nucleases. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003614. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qadri F, Bhuiyan TR, Dutta KK, Raqib R, Alam MS, Alam NH, Svennerholm AM, Mathan MM. 2004. Acute dehydrating disease caused by Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 induce increases in innate cells and inflammatory mediators at the mucosal surface of the gut. Gut 53:62–69. 10.1136/gut.53.1.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sierro F, Dubois B, Coste A, Kaiserlian D, Kraehenbuhl JP, Sirard JC. 2001. Flagellin stimulation of intestinal epithelial cells triggers CCL20-mediated migration of dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:13722–13727. 10.1073/pnas.241308598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodríguez BL, Rojas A, Campos J, Ledon T, Valle E, Toledo W, Fando R. 2001. Differential interleukin-8 response of intestinal epithelial cell line to reactogenic and nonreactogenic candidate vaccine strains of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 69:613–616. 10.1128/IAI.69.1.613-616.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janoff EN, Hayakawa H, Taylor DN, Fasching CE, Kenner JR, Jaimes E, Raij L. 1997. Nitric oxide production during Vibrio cholerae infection. Am. J. Physiol. 273:G1160–G1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rabbani GH, Islam S, Chowdhury AK, Mitra AK, Miller MJ, Fuchs G. 2001. Increased nitrite and nitrate concentrations in sera and urine of patients with cholera or shigellosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 96:467–472. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cua DJ, Tato CM. 2010. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:479. 10.1038/nri2800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mekalanos JJ. 1983. Duplication and amplification of toxin genes in Vibrio cholerae. Cell 35:253–263. 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90228-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearson GD, Woods A, Chiang SL, Mekalanos JJ. 1993. CTX genetic element encodes a site-specific recombination system and an intestinal colonization factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:3750–3754. 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Focareta T, Manning PA. 1991. Distinguishing between the extracellular DNases of Vibrio cholerae and development of a transformation system. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2547–2555. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seper A, Fengler VH, Roier S, Wolinski H, Kohlwein SD, Bishop AL, Camilli A, Reidl J, Schild S. 2011. Extracellular nucleases and extracellular DNA play important roles in Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 82:1015–1037. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07867.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]