Abstract

Exposure to arsenic in drinking water is associated with increased respiratory disease. Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) protects the lung against tissue destruction. The objective of this study was to determine whether arsenic exposure is associated with changes in airway AAT concentration and whether this relationship is modified by selenium. A total of 55 subjects were evaluated in Ajo and Tucson, Arizona. Tap water and first morning void urine were analyzed for arsenic species, induced sputum for AAT and toenails for selenium and arsenic. Household tap-water arsenic, toenail arsenic and urinary inorganic arsenic and metabolites were significantly higher in Ajo (20.6 ± 3.5 µg/l, 0.54 ± 0.77 µg/g and 27.7 ± 21.2 µg/l, respectively) than in Tucson (3.9 ± 2.5 µg/l, 0.16 ± 0.20 µg/g and 13.0 ± 13.8 µg/l, respectively). In multivariable models, urinary monomethylarsonic acid (MMA) was negatively, and toenail selenium positively associated with sputum AAT (P = 0.004 and P = 0.002, respectively). In analyses stratified by town, these relationships remained significant only in Ajo, with the higher arsenic exposure. Reduction in AAT may be a means by which arsenic induces respiratory disease, and selenium may protect against this adverse effect.

Keywords: arsenic, MMA, selenium, alpha-1 antitrypsin, sputum

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to arsenic at concentrations exceeding 100 µg/l in drinking water has been associated with respiratory disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchitis, bronchiectasis, reduced lung function and lung cancer.1–7 However, the extent of clinical effects from lower levels of arsenic exposure and the associated molecular mechanisms of toxicity are poorly understood.

We have previously demonstrated that with tap-water arsenic exposure up to 20 µg/l, urinary arsenic concentration was negatively associated with sputum concentrations of the antiprotease tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1).8 Another important antiprotease in the airway is alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT). AAT helps to defend the lung against neutrophil elastase,9,10 among other proteases. AAT deficiency is a known risk factor for early onset and increased severity of COPD, especially in conjunction with cigarette smoking.11 Our previous proteomic analysis of lung lavage fluid from arsenic-exposed mice compared with non-exposed controls using 2D-gel techniques demonstrated a disappearance of the protein spot consistent with AAT.12 On the basis of the association of airway AAT with arsenic exposure in this in vivo model and the known association of AAT deficiency with lung disease in humans, we chose to analyze for AAT in sputum samples from our previously described arsenic-exposed population.8

Selenium may modulate the carcinogenic potential of arsenic.13–15 However, the mechanism by which this action may occur is unknown. One cross-sectional study in the United States reported that selenium status is associated with measures of lung function.16 Selenium status is also related to the level of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase.17 As arsenic has effects on lung function and is known to upregulate reactive oxygen species in a variety of cell types,18–20 it is reasonable to consider that selenium might modulate the relationship between arsenic exposure and lung disease.

In humans, inorganic arsenic is heavily methylated prior to its excretion in the urine. Ingested inorganic arsenic is methylated to monomethylarsonic acid (MMA) and dimethylarsenic acid (DMA). MMA has greater cytotoxicity than inorganic arsenic,21 and methylation to MMA may increase the carcinogenic potential of arsenic.22 Toenail arsenic concentration provides a longer-term exposure measure than urinary arsenic concentration and is also correlated with levels of arsenic in tap water.23

Given these previous findings, we hypothesized that arsenic exposure would decrease sputum AAT in our study population, and that selenium and the extent of arsenic methylation to MMA would modify this relationship. The objectives of this pilot investigation were to evaluate these relationships in the setting of low-level (~ 20 µg/l) arsenic exposure through tap water.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The study protocol has been described previously.24 This study was part of a larger study that evaluated the effects of a bottled-water intervention on arsenic exposure through drinking water in two Arizona (AZ) communities. Ajo, AZ was selected on the basis of relatively elevated arsenic concentration (~ 20 µg/l) in the tap water drawn from a single well for the entire community, and Tucson, AZ was selected as a control population with lower tap-water arsenic concentrations. Household recruitment took place in 2002 and 2003, and inclusion criteria required at least 3 years of continuous residence in the house, exclusive use of tap water for drinking and food preparation, a minimum age of 18 years and no current smoking. The original design used a probability proportional to size-sampling protocol, based on census blocks that were selected at random. The recruitment goal was five households per census block; however, this goal could not be attained. In Ajo, the recruitment rate was < 12%, and a census of the entire community was performed. In Tucson, two of the five census tracts that most closely resembled the Ajo population in the proportion of Hispanic residents and median age (in 2000 US census) were randomly selected, households were randomized and recruitment of five households per block was attempted. The recruitment rate in Tucson was < 10%, given that the majority of people contacted regularly consumed bottled water, an exclusion criteria. The first two adults in each household were offered participation, although in many cases only one subject consented. A questionnaire was administered by research study team members in either English or Spanish, depending on the preference of the subject. Information on subject demographics, current and past medical problems, and household, occupational and environmental exposures was obtained.

Urine Arsenic

Detailed methods for analysis of urinary arsenic in this study have been reported elsewhere24 and are summarized here. First morning void urine samples were collected in sterile, arsenic-free containers and processed within 2 h of collection. After centrifugation, supernatant was stored at −20 °C for transport, then transferred to the University of Arizona where it was frozen at −70 °C for subsequent analysis. A modified HPLC-ICP-MS speciation method was used for measurement of arsenic. The HPLC system consisted of an Agilent 1100 HPLC (Agilent Technologies) with a reverse-phase C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The sensitivity limits for arsenic species were predetermined to range between 0.04 and 0.08 µg/l. Inorganic arsenic (As) sum of species was calculated as the sum of As+3, As+5, MMA and DMA.

Toenail Selenium and Arsenic

Toenails were sent to Dartmouth College as part of a cooperative project with the University of Arizona. Each toenail sample was washed with acetone, Triton X-100 and water to remove external contaminants. The complete sample was then weighed into a Teflon vial and digested in 1 ml of concentrated HNO3 under pressure at 30 °C in a microwave oven. Four microlitres of water were added to the resulting solution that was stored at 5 °C. For arsenic analysis, the solution was diluted an additional four times with water and analyzed using an Agilent 7500c ICPMS instrument with an Octapole reaction cell that was pressurized with hydrogen gas. For analysis of selenium, the same procedures were followed except for the use of hydrogen as a reaction gas, and then selenium was monitored using three isotopes m/z = 76, 77 and 78, as previously described.25 The final result was the average of the results for all individual selenium isotopes. The detection limit for both arsenic and selenium was 0.005 µg/g.

Sputum Induction and AAT Analysis

Sputum induction was performed by using a sterile 3% saline aerosol (Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA) generated by using DeVilbiss Ultra-Neb 99HD ultrasonic nebulizers (Somerset, PA, USA) set on maximum output. Subjects were encouraged to cough up every 2 min for a period of 30 min and the sputum was collected. Prior to each cough, subjects were asked to discard any saliva to minimize salivary contamination of the sputum sample. Sputum samples were treated with 10% Sputolysin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) containing penicillin–streptomycin to inhibit bacterial growth. Samples were then centrifuged to separate cells from the supernatant, which was stored at −20 °C for transport before being transferred to the University of Arizona for storage at −70 °C.

Sputum supernatant samples were analyzed in duplicate for levels of AAT using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH, USA). A uniform initial sample dilution was performed on all samples to maximize the number of samples with concentrations within the standard range for the AAT ELISA. Total protein concentration was estimated using the biocinchoninic acid (BCA) assay in a microplate (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). The limit of detection (LOD) for the assay was 825 ng/ml.

Statistical Methods

Stata 11.2 (College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analyses. To account for variation in sputum sample dilution during induction, analyses were carried out using the ratio of sputum AAT over sputum total protein (AAT/total protein). Sputum AAT/total protein, toenail arsenic and selenium, tap-water arsenic and urinary arsenic biomarkers were normalized using natural log (log(e)) transformations, and values below the LOD were assigned a value equal to half of the LOD. Pearson’s χ2 tests were used to compare sex, ethnic group (Hispanic white/non-Hispanic white), self-reported diabetes (ever/never), kidney disease (ever/never), asthma (ever/never) and smoking status (ever/never) by town (Ajo/Tucson). A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was run to compare age distribution in Ajo and Tucson, and independent sample t-tests were used to compare log(e)-transformed biomarker concentrations between towns. We evaluated the relation of each urinary arsenic species independently in addition to the sum of the species and toenail total arsenic in pairwise Pearson correlations using log(e)-transformed values. Simple linear regression was used to evaluate the marginal associations between log(e)-transformed sputum AAT/total protein, toenail arsenic and urinary MMA, and potential confounders including sex, age, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, kidney disease, seafood consumption during the previous 3 days (yes/no) and smoking status. Variables associated with the dependent outcome and predictor variables at P < 0.20 in crude analyses were then entered into the multivariable model and tested for confounding (P < 0.10) using the likelihood ratio test. Separate analyses, stratified by town, were also run. Post hoc diagnostics were performed to assess whether assumption parameters for multiple linear regression modeling were met.

RESULTS

A total of 73 individuals participated in the original study of drinking water intervention, 40 from Ajo and 33 from Tucson. Owing to subjects’ refusal, inability to schedule a session or failure to produce sputum, sputum samples were available for only 57 subjects, 53 of whom also provided urine samples, 31 from Ajo and 22 from Tucson (Table 1). Participants ranged in age from 30–92 years, but most of the population was over 60 years of age. The majority of the population was female (60%) and non-Hispanic white (61% in Ajo and 77% in Tucson). A total of 11 individuals reported seafood consumption (21%) within 3 days of completing the questionnaires. There were no statistically significant differences between the Tucson and Ajo populations in age distribution, sex, ethnicity, asthma, kidney disease, diabetes status or past smoking history.

Table 1.

Population characteristics with respect to town (Ajo and Tucson)

| Ajo (N) (%) | Tucson (N) (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total subjectsa | 31 (58) | 22 (42) | |

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 63.25 ± 16.03 | 65.86 ± 14.59 | 0.652b |

| Under 60 years | 11 (35) | 8 (36) | |

| 61–80 Years | 14 (45) | 10 (46) | |

| Over 80 years | 6 (19) | 4 (18) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 19 (61) | 13 (59) | 0.872c |

| Male | 12 (39) | 9 (41) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 12 (39) | 5 (23) | 0.219c |

| White, non-Hispanic | 19 (61) | 17 (77) | |

| Pre-existing illness | |||

| Ever asthma | 11 (35) | 13 (59) | 0.089c |

| Ever diabetes | 6 (19) | 2 (9) | 0.304c |

| Ever kidney disease | 6 (19) | 3 (14) | 0.585c |

| Ever smoked | |||

| Yes | 15 (48) | 10 (50) | 0.910c |

| No | 16 (52) | 10 (50) |

Includes subjects with sputum AAT, toenail selenium and urinary arsenic data.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Pearson’s χ2 test.

Missing data on smoking in two subjects in Tucson.

A comparison by town of mean concentrations of sputum AAT and protein, total tap-water arsenic, urinary arsenic species, and toenail arsenic and selenium is shown in Table 2. Two (3.8%) of the sputum AAT concentrations were below the LOD, whereas all of the sputum total protein, urinary MMA, and toenail arsenic and selenium concentrations were above the LOD. The mean concentration of sputum AAT was 10.1 µg/ml and there was no difference in sputum AAT or in the ratio of sputum AAT to total protein by town, although the standard deviations were large relative to their respective means. Tap-water arsenic, urinary arsenic species (except As+3) and toenail arsenic were all significantly higher in Ajo than in Tucson (all P ≤ 0.003).

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation concentration of tap-water arsenic, urinary arsenic, sputum alpha-1 antitrypsin and protein, and toenail arsenic and selenium in Ajo and Tucson

| Variable | Combined population (mean ± SD) | Ajo (mean ± SD) | Tucson (mean ± SD) | P-value (t-test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tap water, n | 46 | 26 | 20 | |

| Total As (µg/l) | 13.36 ± 8.90 | 20.60 ± 3.51 | 3.94 ± 2.50 | <0.001 |

| Urine, n | 53 | 31 | 22 | |

| As+3 (µg/l) | 5.45 ± 8.23 | 5.23 ± 6.78 | 5.77 ± 10.10 | 0.170 |

| As+5 (µg/l) | 1.29 ± 2.36 | 2.02 ± 2.84 | 0.26 ± 0.55 | <0.001 |

| MMA (µg/l) | 2.27 ± 3.30 | 3.06 ± 4.03 | 1.14 ± 1.22 | 0.003 |

| DMA (µg/l) | 12.54 ± 11.26 | 17.33 ± 12.11 | 5.79 ± 4.77 | <0.001 |

| Inorganic As sum of speciesa (µg/l) | 21.55 ± 19.74 | 27.65 ± 21.22 | 12.96 ± 13.75 | <0.001 |

| % MMAb | 0.11 ± 0.07 | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 0.11 ± 0.08 | 0.987 |

| Toenail (n) | 53 | 31 | 22 | |

| Baseline As (µg/g) | 0.38 ± 0.63 | 0.54 ± 0.77 | 0.16 ± 0.20 | 0.003 |

| Baseline Se (µg/g) | 1.47 ± 1.56 | 1.50 ± 1.93 | 1.43 ± 0.82 | 0.094 |

| Sputum, n | 53 | 31 | 22 | |

| AAT (µg/ml) | 10.52 ± 12.86 | 9.27 ± 10.71 | 12.27 ± 15.51 | 0.502 |

| Total protein (mg/ml) | 8.42 ± 4.49 | 8.03 ± 3.75 | 8.95 ± 5.442 | 0.485 |

| AAT/total protein (µg/mg) | 1.75 ± 3.40 | 1.91 ± 4.22 | 1.52 ± 1.76 | 0.731 |

Abbreviations: AAT, alpha-1 antitrypsin; As, arsenic; DMA dimethylarsinic acid; MMA, monomethylarsonic acid; Se, selenium.

Inorganic as sum of species = (As+3+As+5+MMA+DMA).

% MMA = MMA/(As+3+As+5+MMA+DMA).

Seafood consumption (during the previous 3 days) was not associated with AAT/protein. It was negatively correlated with log(e) MMA, but not with any other biomarkers of arsenic exposure (not shown). Water, toenail and urinary arsenic measures in the combined population were mostly significantly correlated: toenail arsenic was correlated with urinary As+5, urinary inorganic arsenic sum of species and water arsenic; and water arsenic with all arsenic measures except urinary As+3 (Table 3). Toenail selenium was highly negatively correlated with toenail arsenic (P < 0.001) and urinary As+5 (P = 0.026), but not with other arsenic-exposure measures.

Table 3.

Pairwise correlations among log(e)-transformed tap-water arsenic, urinary arsenic, toenail arsenic and selenium, and sputum alpha-1 antitrypsin/total protein in the combined populations

| Toenail Se |

Toenail As |

Urinary As+3 |

Urinary As+5 |

Urinary MMA |

Urinary DMA |

Urinary Inorganic As sum of species |

Water As | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputum AAT/total protein | 0.392a | −0.406a | 0.037 | −0.214 | −0.319b | −0.158 | −0.180 | 0.011 |

| Toenail Se | — | −0.547c | −0.066 | −0.306b | −0.046 | −0.122 | −0.155 | −0.036 |

| Toenail total As | — | 0.161 | 0.410a | 0.203 | 0.233 | 0.289b | 0.324b | |

| Urinary As+3 | — | 0.280b | 0.308b | 0.508c | 0.764c | 0.262 | ||

| Urinary As+5 | — | 0.453c | 0.507c | 0.503c | 0.533c | |||

| Urinary MMA | — | 0.762c | 0.677c | 0.676c | ||||

| Urinary DMA | — | 0.907c | 0.762c | |||||

| Urinary inorganic As sum of species | — | 0.644c |

Abbreviations: AAT, alpha-1 antitrypsin; As, arsenic; DMA dimethylarsinic acid; MMA, monomethylarsonic acid; Se, selenium.

Note: Urinary inorganic As sum of species = (As3+ + As5+ + MMA + DMA).

P<0.01.

P<0.05.

P<0.001.

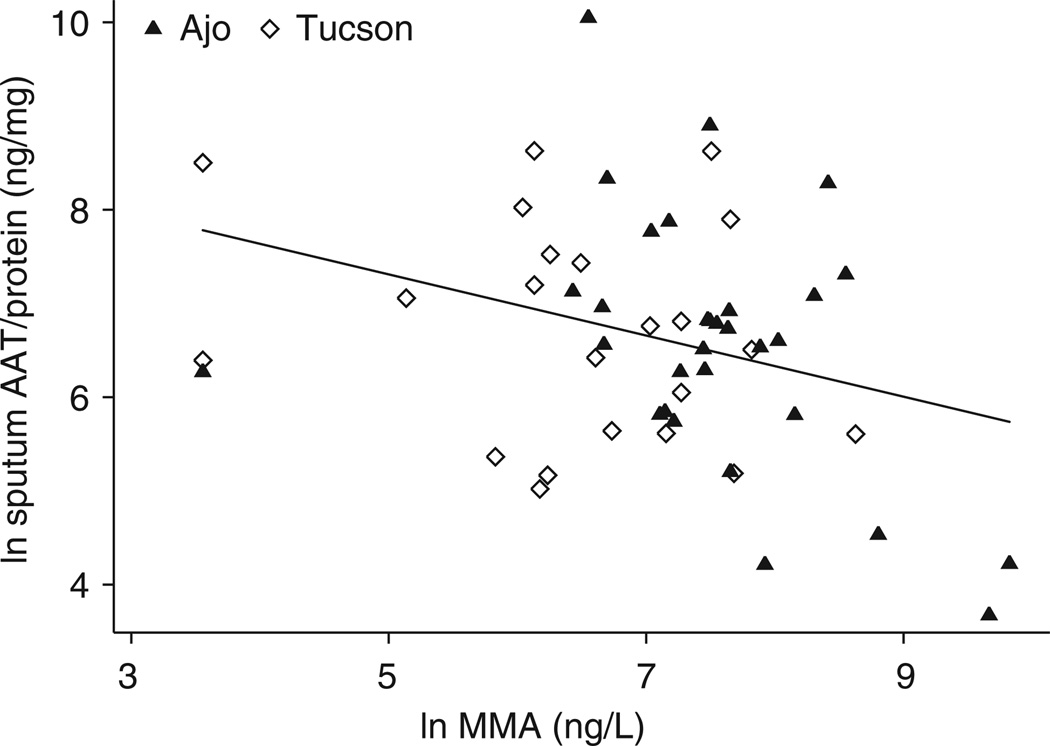

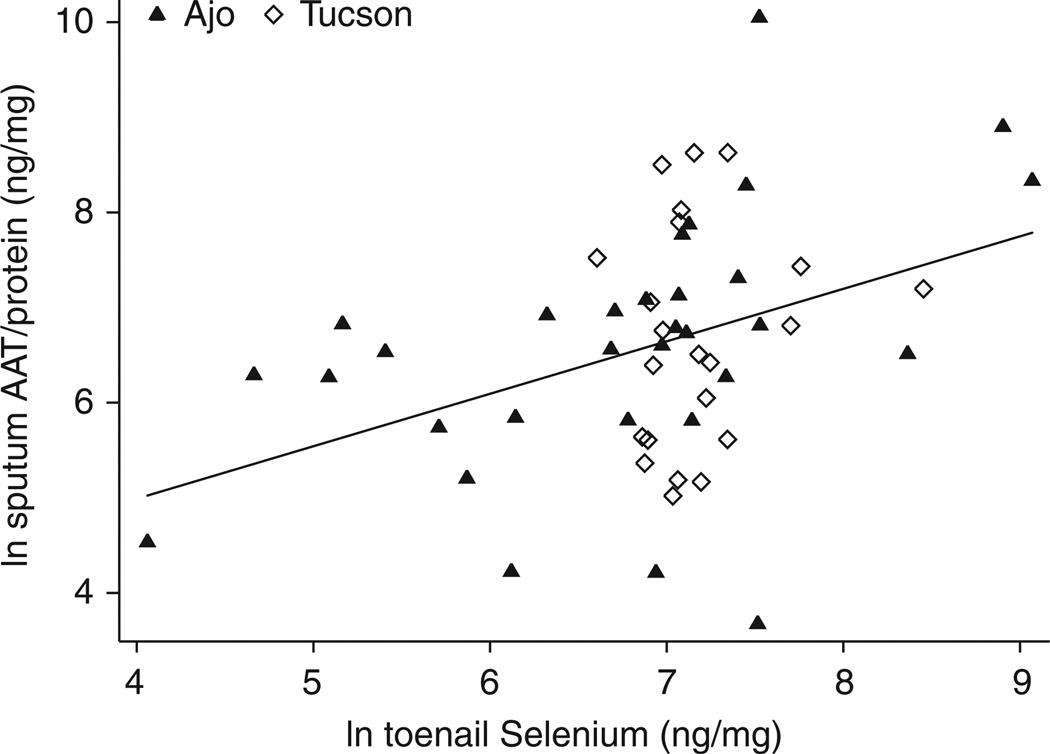

In simple linear regression analyses, log(e) urinary MMA (P = 0.020) (Figure 1) and log(e) toenail arsenic (P < 0.003) (not shown) were significant negative predictors of log(e) sputum AAT/total protein, whereas toenail selenium was a significant positive predictor (P = 0.004) (Figure 2). Tap-water arsenic, urinary As+3, As+5, DMA and inorganic arsenic sum of species were not significantly associated with sputum AAT/total protein. Measures of correlation among these markers are presented in Table 3. Several variables were marginally associated with sputum AAT/protein, including sex, smoking status, kidney disease and diabetes, but none of these reached statistical significance. There was no relation between seafood consumption and sputum AAT.

Figure 1.

Correlation of log(e) sputum alpha-1 antitrypsin/total protein and log(e) urinary MMA (r = −0.3187, P = 0.020).

Figure 2.

Correlation of log(e) sputum alpha-1 antitrypsin/total protein and log(e) toenail selenium (r = 0.3918, P = 0.0036).

In multiple regression models of the total population using log(e)-transformed measures, urinary MMA was negatively associated (P = 0.004), whereas toenail selenium was positively associated (P = 0.002) with sputum AAT/total protein (Table 4). The other covariates in the model (sex and town) did not reach statistical significance, although female subjects had marginally lower AAT/protein ratios than male subjects (P = 0.052). There was no significant interaction between urinary MMA and toenail selenium in the model (P = 0.475). When toenail arsenic was included in the multivariable model in place of urinary MMA, the results (not shown) demonstrated a significant negative effect of arsenic exposure (P = 0.041) on sputum AAT/total protein, but the effect of toenail selenium was not significant (P = 0.138). In models using household tap-water arsenic concentration or urinary inorganic arsenic sum of species as a measure of arsenic exposure, there was no relation between arsenic exposure and sputum AAT/protein. In both of these models, however, toenail selenium was a significant positive predictor of sputum AAT/protein (P = 0.001 and P = 0.006, respectively).

Table 4.

Multiple regression of log(e) sputum AAT/total protein in combined population (n = 53)

| Predictor variables | β-coefficient | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

| Ajo | Ref | — |

| Tucson | −0.542 | 0.120 |

| Log(e) urinary MMA | −0.406 | 0.004 |

| Log(e) toenail selenium | 0.560 | 0.002 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | ref | — |

| Female | −0.614 | 0.052 |

| Constant | 4.576 | 0.001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.2766 | |

Ajo = 1, Tucson = 2.

Although seafood consumption was not associated with AAT/protein in univariate models, we tested it in the multivariate regression models because of its relation to MMA. The effect of adding seafood consumption to the model of the combined population was negligible; it was not a significant variable in the model, and the relation between AAT/protein and urinary MMA and toenail selenium did not change. Furthermore, mean (ln) urinary MMA concentrations were not significantly different comparing 11 subjects who had seafood in the previous 3 days with all other subjects.

In analyses stratified by town (Table 5), urinary MMA and toenail selenium were significantly associated with sputum AAT/total protein in Ajo only, the town with higher tap-water arsenic concentrations, and female sex was associated with decreased AAT/protein. There was no significant relationship between urinary MMA, toenail selenium or female sex and sputum levels of AAT/protein in the Tucson population alone.

Table 5.

Multiple regression of log(e) sputum AAT/total protein, stratified by town (Ajo versus Tucson) using the same model as that used for the combined population

| Predictor variables |

Ajo (n = 31) | Tucson (n = 22) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-coefficient | P-value | β-coefficient | P-value | |

| Log(e) urinary MMA | −0.552 | 0.004 | −0.241 | 0.267 |

| Log(e) toenail selenium | 0.591 | 0.002 | 0.293 | 0.702 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Female | −0.815 | 0.043 | −0.438 | 0.459 |

| Constant | 4.235 | 0.003 | 5.199 | 0.389 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.4240 | −0.0311 | ||

Abbreviation: MMA, monomethylarsonic acid.

DISCUSSION

The association of increased arsenic exposure, measured as urinary MMA, with decreased sputum AAT provides a potential mechanism for arsenic-induced respiratory disease. Building on our previous study demonstrating increased matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9)/TIMP-1 with arsenic exposure,8 the current study continues to support an alteration in protease/antiprotease balance due to arsenic that could lead to lung tissue destruction. The current study results also suggest that selenium exposure may have a protective effect on sputum AAT. Urinary MMA, as compared with urinary arsenic sum of species, toenail arsenic and tap-water arsenic concentrations, provided the most consistent predictor of sputum AAT, potentially due to the reportedly high toxicity of MMA.21,22

Alteration of protease/antiprotease balance has been linked to lung disease. AAT deficiency is a known risk factor for development of COPD even in non-smokers.11 AAT deficiency also has other deleterious effects, including increasing susceptibility to pulmonary infection.26 Increased levels of AAT greatly reduce damage from inhaled toxicants such as cigarette smoke.27,28 The previously described imbalance in MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio can also skew lung remodeling towards tissue breakdown, a process that could lead to airway disease and emphysema.29–35

The rationale for investigating AAT came from proteomic analysis of lung lavage fluid in arsenic-exposed mice.12 Given similarities in protein (AAT and RAGE) changes and increased MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio identified in both arsenic-exposed mice and humans, it seems reasonable to postulate that the effect of low-level (<50 µg/l) arsenic exposure on airway protein expression may be relatively consistent across these species. However, studies of alterations in pulmonary function with levels of arsenic exposure below 50 µg/l have not been carried out in either species, therefore the functional or clinical effects of this relatively low-level arsenic exposure are not yet known.

The mechanisms by which arsenic reduces sputum AAT and selenium modifies the effect of arsenic on AAT have not been elucidated. As MMP-9 cleaves AAT,31 and MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio in human sputum is increased in response to low-level arsenic exposure,8 it is possible that arsenic decreases AAT through increased MMP-9 activity. However, in our previous study, we did not specifically test for MMP-9 activity. Selenium appears to have a protective effect on lung function in a general population selected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), although the potentially confounding effects of concurrent exposure to arsenic or other environmental contaminants were not assessed.16 The association between selenium and sputum AAT levels may be due to selenium-increasing AAT production in the liver, suggested by increased growth of human hepatoma cells with selenium supplementation.36 Other potential mechanisms by which selenium could modulate the toxic effects of arsenic include increased expression of glutathione peroxidase,17 alterations in DNA methylation14 and cell cycle effects.37 In contrast to our current study, toenail selenium did not predict sputum MMP-9/TIMP-1 and RAGE in previous studies.8,12

The arsenic-exposure concentrations evaluated in this study are well below those evaluated in most other studies of arsenic toxicity. The Tucson and Ajo populations were exposed, respectively, to mean levels of ~4 and ~20 µg/l arsenic in drinking water. Although there were significant differences between Tucson and Ajo in total urinary inorganic arsenic, there was a marked overlap in total urinary inorganic arsenic between the towns.24 Differences in quantities of tap water ingested through drinking and cooking may have contributed to this overlap, along with consumption of water outside the household and diet.

Arsenic methylation may increase toxicity.38–41 As previously mentioned, MMA has greater in vitro cytotoxicity than inorganic arsenic, and methylation to MMA may increase the carcinogenic potential of arsenic.21,22 However, further methylation of MMA to DMA is considered a detoxification reaction.42 In our study, urinary MMA was more consistently associated with decreased sputum AAT/total protein than urinary arsenic sum of species, toenail arsenic or tap-water arsenic concentrations, supporting a deleterious effect of methylation, although, in the models stratified by town, this association was only significant in Ajo, likely due to the higher levels of arsenic exposure in Ajo as compared with Tucson.

The effects of arsenic at low doses appear to include multiple system changes. In addition to our current and past studies demonstrating effects of arsenic at tap-water concentrations of 20 µg/l and below on sputum proteins, other studies have suggested associations with altered DNA repair, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and kidney disease.43,44 Decreased DNA repair has been reported in subjects with mean drinking water arsenic exposure of 32 µg/l as compared with a control group with mean exposure of 0.7 µg/l.43 Increased standardized mortality ratios for cerebrovascular disease, diabetes and kidney disease were reported in a study of Michigan residents with well-water arsenic concentrations of 10–100 µg/l.44 Our current study findings support the growing evidence that arsenic exposure below 50 µg/l has deleterious effects, and also bring into question whether the current 10 µg/l Maximum Contaminant Level established by the EPA is suitably protective.

There were a number of limitations to our study. The number of subjects evaluated was relatively small, and the study should be replicated in larger populations with a greater range of arsenic exposure. The use of ELISA to measure sputum AAT does not permit evaluation of AAT activity, and neutrophil elastase should be measured in future studies to determine whether this protease/antiprotease balance has been altered. Although we were able to measure sputum AAT concentrations, sputum cell count and differential data were not available. Additional in vivo and in vitro studies are needed to establish toxicologic mechanisms for our observed findings. Another potential concern is the relation of seafood consumption and methylated arsenic compounds. Although there were significantly lower levels of log(e) MMA among seafood eaters in our population, this had no influence on the relation between MMA and toenail Se and AAT/protein and it is unclear why there should be a negative relation between seafood consumption and MMA. In a study of urinary arsenic metabolites in subjects before and 3 days after consumption of seafood, there were similar levels of the metabolites.45 Finally, our study evaluated biomarkers representing concurrent (drinking water arsenic and urinary MMA) and cumulative (toenail arsenic and selenium) measures of exposure. Although we believe that sputum AAT/total protein should vary more with concurrent exposure than cumulative exposure, the actual temporal relationship has not, to our knowledge, been elucidated.

In conclusion, sputum AAT/total protein level was negatively associated with urinary MMA in populations with tap-water arsenic exposures up to 20 µg/l. Toenail selenium concentration was protective, although this effect was only seen in Ajo, with higher arsenic exposures. Additional studies in other arsenic-exposed populations are necessary to confirm these results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by the NIEHS Superfund Basic Research Program grant P42 ES04940, the NIEHS Center for Toxicology Southwest Environmental Health Sciences Center grant P30 ES06694 and the US EPA grant R832095-010.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.von Ehrenstein OS, Mazumder DN, Yuan Y, Samanta S, Balmes J, Sil A, et al. Decrements in lung function related to arsenic in drinking water in West Bengal, India. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:533–541. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazumder DN, Haque R, Ghosh N, De BK, Santra A, Chakraborti D, et al. Arsenic in drinking water and the prevalence of respiratory effects in West Bengal, India. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:1047–1052. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AH, Goycolea M, Haque R, Biggs ML. Marked increase in bladder and lung cancer mortality in a region of Northern Chile due to arsenic in drinking water. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:660–669. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AH, Marshall G, Yuan Y, Ferreccio C, Liaw J, von Ehrenstein O, et al. Increased mortality from lung cancer and bronchiectasis in young adults after exposure to arsenic in utero and in early childhood. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1293–1296. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borgono JM, Vicent P, Venturino H, Infante A. Arsenic in the drinking water of the city of Antofagasta: epidemiological and clinical study before and after the installation of a treatment plant. Environ Health Perspect. 1977;19:103–105. doi: 10.1289/ehp.19-1637404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CJ, Wu MM, Lee SS, Wang JD, Cheng SH, Wu HY. Atherogenicity and carcinogenicity of high-arsenic artesian well water. Multiple risk factors and related malignant neoplasms of blackfoot disease. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:452–460. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.5.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen CJ, Chen CW, Wu MM, Kuo TL. Cancer potential in liver, lung, bladder and kidney due to ingested inorganic arsenic in drinking water. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:888–892. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josyula AB, Poplin GS, Kurzius-Spencer M, McClellen HE, Kopplin MJ, Sturup S, et al. Environmental arsenic exposure and sputum metalloproteinase concentrations. Environ Res. 2006;102:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadel JA. Role of neutrophil elastase in hypersecretion during COPD exacerbations, and proposed therapies. Chest. 2000;117(5) Suppl 2:386S–389S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_2.386s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeMeo DL, Silverman EK. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. 2: genetic aspects of alpha(1)-antitrypsin deficiency: phenotypes and genetic modifiers of emphysema risk. Thorax. 2004;59:259–264. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.006502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laurell CB, Eriksson S. The electrophoretic alpha-1-globulin pattern of serum in alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1963;15:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lantz RC, Lynch BJ, Boitano S, Poplin GS, Littau S, Tsaprailis G, et al. Pulmonary biomarkers based on alterations in protein expression after exposure to arsenic. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:586–591. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu GG. Investigation of protective effect of selenium on genetic materials among workers exposed to arsenic. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1989;23:286–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis CD, Uthus EO, Finley JW. Dietary selenium and arsenic affect DNA methylation in vitro in Caco-2 cells and in vivo in rat liver and colon. J Nutr. 2000;130:2903–2909. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.12.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kibriya MG, Jasmine F, Argos M, Verret WJ, Rakibuz-Zaman M, Ahmed A, et al. Changes in gene expression profiles in response to selenium supplementation among individuals with arsenic-induced pre-malignant skin lesions. Toxicol Lett. 2007;169:162–176. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu G, Cassano PA. Antioxidant nutrients and pulmonary function: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:975–981. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romanowska M, Kikawa KD, Fields JR, Maciag A, North SL, Shiao YH, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation on expression of glutathione peroxidase isoforms in cultured human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun X, Li B, Li X, Wang Y, Xu Y, Jin Y, et al. Effects of sodium arsenite on catalase activity, gene and protein expression in HaCaT cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:1139–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper KL, Liu KJ, Hudson LG. Contributions of reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in arsenite-stimulated hemeoxygenase-1 production. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;218:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eblin KE, Bredfeldt TG, Buffington S, Gandolfi AJ. Mitogenic signal transduction caused by monomethylarsonous acid in human bladder cells: role in arsenic-induced carcinogenesis. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:321–330. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Styblo M, Del Razo LM, Vega L, Germolec DR, LeCluyse EL, Hamilton GA, et al. Comparative toxicity of trivalent and pentavalent inorganic and methylated arsenicals in rat and human cells. Arch Toxicol. 2000;74:289–299. doi: 10.1007/s002040000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith AH, Steinmaus CM. Health effects of arsenic and chromium in drinking water: recent human findings. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:107–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karagas MR, Tosteson TD, Blum J, Klaue B, Weiss JE, Stannard V, et al. Measurement of low levels of arsenic exposure: a comparison of water and toenail concentrations. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:84–90. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Josyula AB, McClellen H, Hysong TA, Kurzius-Spencer M, Poplin GS, Sturup S, et al. Reduction in urinary arsenic with bottled-water intervention. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24:298–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturup S, Hayes RB, Peters U. Development and application of a simple routine method for the determination of selenium in serum by octopole reaction system ICPMS. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;381:686–694. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2946-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theegarten D, Anhenn O, Hotzel H, Wagner M, Marra A, Stamatis G, et al. A comparative ultrastructural and molecular biological study on Chlamydia psittaci infection in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and non-alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency emphysema versus lung tissue of patients with hamartochondroma. BMC Infect Dis. 2004;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhami R, Gilks B, Xie C, Zay K, Wright JL, Churg A. Acute cigarette smoke-induced connective tissue breakdown is mediated by neutrophils and prevented by alpha1-antitrypsin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:244–252. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.2.3809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pemberton PA, Kobayashi D, Wilk BJ, Henstrand JM, Shapiro SD, Barr PJ. Inhaled recombinant alpha 1-antitrypsin ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in the mouse. COPD. 2006;3:101–108. doi: 10.1080/15412550600651248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elias JA. Airway remodeling in asthma. Unanswered questions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(3 Pt 2):S168–S171. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_2.a1q4-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell RE, Culpitt SV, DeMatos C, Donnelly L, Smith M, Wiggins J, et al. Release and activity of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 by alveolar macrophages from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:602–609. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.5.4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkinson JJ, Senior RM. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in lung remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:12–24. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0166TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coraux C, Martinella-Catusse C, Nawrocki-Raby B, Hajj R, Burlet H, Escotte S, et al. Differential expression of matrix metalloproteinases and interleukin-8 during regeneration of human airway epithelium in vivo. J Pathol. 2005;206:160–169. doi: 10.1002/path.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies DE, Wicks J, Powell RM, Puddicombe SM, Holgate ST. Airway remodeling in asthma: new insights. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:215–225. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ten Hacken NH, Postma DS, Timens W. Airway remodeling and long-term decline in lung function in asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9:9–14. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pascual RM, Peters SP. Airway remodeling contributes to the progressive loss of lung function in asthma: an overview. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakabayashi H, Taketa K, Miyano K, Yamane T, Sato J. Growth of human hepatoma cells lines with differentiated functions in chemically defined medium. Cancer Res. 1982;42:3858–3863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narayanan BA. Chemopreventive agents alters global gene expression pattern: predicting their mode of action and targets. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:711–727. doi: 10.2174/156800906779010218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto S, Konishi Y, Matsuda T, Murai T, Shibata MA, Matsui-Yuasa I, et al. Cancer induction by an organic arsenic compound, dimethylarsinic acid (cacodylic acid), in F344/DuCrj rats after pretreatment with five carcinogens. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1271–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wanibuchi H, Yamamoto S, Chen H, Yoshida K, Endo G, Hori T, et al. Promoting effects of dimethylarsinic acid on N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine-induced urinary bladder carcinogenesis in rats. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2435–2439. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.11.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto S, Wanibuchi H, Hori T, Yano Y, Matsui-Yuasa I, Otani S, et al. Possible carcinogenic potential of dimethylarsinic acid as assessed in rat in vivo models: a review. Mutat Res. 1997;386:353–361. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(97)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gebel TW, Suchenwirth RH, Bolten C, Dunkelberg HH. Human biomonitoring of arsenic and antimony in case of an elevated geogenic exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:33–39. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9810633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrick JS, Ayala-Fierro F, Cullen WR, Carter DE, Vasken Aposhian H. Monomethylarsonous acid (MMA(III)) is more toxic than arsenite in Chang human hepatocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;163:203–207. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrew AS, Burgess JL, Meza MM, Demidenko E, Waugh MG, Hamilton JW, et al. Arsenic exposure is associated with decreased DNA repair in vitro and in individuals exposed to drinking water arsenic. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1193–1198. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meliker JR, Wahl RL, Cameron LL, Nriagu JO. Arsenic in drinking water and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and kidney disease in Michigan: a standardized mortality ratio analysis. Environ Health. 2007;6:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsueh YM, Hsu MK, Chiou HY, Yang MH, Huang CC, Chen CJ. Urinary arsenic speciation in subjects with or without restriction from seafood dietary intake. Toxicol Lett. 2002;133:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]