On November 12, 2013 a joint task force for the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) released new guidelines for the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults. This document arrives after several years of intense deliberation and 12 years after the previous well known Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) guidelines and 8 years after an ATPIII update recommending aggressive LDL-C lowering (<70 mg/dL) in high risk individuals (1,2). It represents a major shift in the approach and management of blood cholesterol and has sparked considerable controversy.

The following commentary serves to summarize the new guidelines and the philosophical approach employed by the task force in generating them. Also provided is a critical examination of some advantages, as well as what we believe to be several shortcomings, of the proposed guidelines. These latter points are illustrated through discussions surrounding some applicable case examples.

Summary of New Guidelines

In collaboration with the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health, the ACC and the AHA, formed an expert panel task force in 2008. The task force elected to use strict adherence to randomized control trial (RCT) studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs to formulate all recommendations with the goal of providing the strongest possible evidence for the treatment of cholesterol for primary and secondary reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). According to the authors, the rational for this strict ideological adherence exclusively to RCT data (only pre-defined outcomes of the trials, no post hoc analyses) is that: “By using RCT data to identify those most likely to benefit from cholesterol-lowering statin therapy, the recommendations will be of value to primary care clinicians as well as specialists concerned with ASCVD prevention. Importantly, the recommendations were designed to be easy to use in the clinical setting, facilitating the implementation of a strategy of risk assessment and treatment focused on the prevention of ASCVD (3).”

In addition, the task force also states the guidelines are meant to `inform clinical judgment, not replace it' and that clinician judgment in addition to discussion with patients remains vital. It is worthy to note that during deliberations, the NHLBI removed themselves from participating, stating it was no longer their mission to draft new guidelines. Additionally, other initial members of the task force removed themselves from the panel due to disagreement and concerns regarding the direction of the new guidelines. The guidelines, and an accompanying new cardiovascular risk calculator that the guidelines employ, were released without a preliminary period to allow for open discussion and comment/critique by physicians outside the panel. No attempt to harmonize the guidelines with either prior versions (e.g. ATP III), or current international guidelines was made.

The following represent the major recommended changes in the approach to treating blood cholesterol:

“Treat to target” goals for LDL-C and non-HDL-C are no longer recommended

Treatment is focused on intensity of statin, (high and moderate intensity), virtually eliminating low dose statin therapy

ASCVD definition now includes stroke in addition to coronary heart disease and peripheral arterial disease

4 major treatment groups were identified (see below)

Marked reduced emphasis on non-statin therapies

No guidelines are provided for treatment of triglycerides

The updated guidelines repeatedly emphasize the importance of lifestyle management and modification as the foundation for reduction of ASCVD events regardless of cholesterol therapy choice. Patients with NYHA class II–IV heart failure and hemodialysis patients were excluded due to the lack of RCT data to support recommendations. Guidelines only are applicable to individuals between the ages of 40 – 79 because it was believed that current RCT data does not allow development of guidelines outside of this age range.

The 4 specified treatment groups and recommended statin intensity represent the major focus of the new guidelines (Table 1). A new risk score employed to calculate 10 year and life-time risk were also presented to help determine which category a primary prevention, non-diabetic subject resides within (4). We will address each of the four treatment groups, providing relevant case examples for the readership to consider. In general, we believe the first and fourth categories are where our major issues of disagreement with the recommendations arise, and are best illustrated through cases.

Table 1.

Intensity of Statin Therapy and 4 Major Recommended Indications

| High-Intensity Statin Therapy (Lowers LDL–C ~≥50%) | Moderate-Intensity Statin Therapy (Lowers LDL-C by ~ 30% to 49%) |

|---|---|

Indicated for:

|

Indicated for:

|

The following are considered high-intensity statins:

|

The following are considered mod-intensity statins:

|

Adaptation from new cholesterol guidelines (3). ASCVD = Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Clinician decision to use moderate or high dose statin for this group

4 MAJOR STATIN TREATMENT GROUPS

1. Individuals with Clinical ASCVD

Advantages

Appropriately urges statins as first line treatment and focus on highest possible tolerated dose.

Designates all ASCVD including coronary, peripheral and cerebrovascular disease as a high risk group

Perception of simplified treatment strategy (high and mod dose) by removing target LDL-C level and thus less monitoring of lipid levels. This can also be seen as a large disadvantage as outlined below.

Limitations

Makes follow up LDL-C level irrelevant, assuming there is no gradation in residual risk and hence no tailoring of therapy to the individual.

Patients no longer have a goal to strive for or monitor their progress.

Ignores pathophysiology of CAD, and evidence of residual risk in subjects on both moderate and high intensity statin therapy. Ignores potential benefits of treating to lower LDL-C goals or non-HDL-C. Thus, eliminates multidrug therapy consideration.

Does not address patients with recurrent CV events already on max tolerated statin.

Undermines potential development and use of new therapeutics for treatment of dysplipidemia in patients with ASCVD.

Case example 1

A 52 year old African American male is presenting with newly discovered moderate coronary artery disease that was not severe enough to warrant stenting. He has no history of HTN, DM or smoking and a SBP of 130 mmHg. He has BMI 26 kg/m2, exercises regularly and follows a low cholesterol diet. He has the following labs: TC 280, HDL-C 50, TG 250 and calculated LDL-C 190 mg/dL.

After beginning atorvastatin 80 mg daily, meeting with the nutritionist and redoubling his dietary efforts, repeat fasting lipids were examined 2 months later revealing: TC 180, HDL 45, TG 75 and calculated LDL-C 110 mg/dL.

According to the new guidelines, this patient with known ASCVD should be placed on intensive statin therapy. Statins as the primary therapy and intensive treatment in these high-risk individuals is quite appropriate. However, once on therapy, the new guidelines do not encourage repeat measures of the patient's lipid panel other than to assess compliance. Patient to patient differences in response to medications are common and without repeat testing it would be difficult to know if the intensive therapy goal of a 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol is achieved.

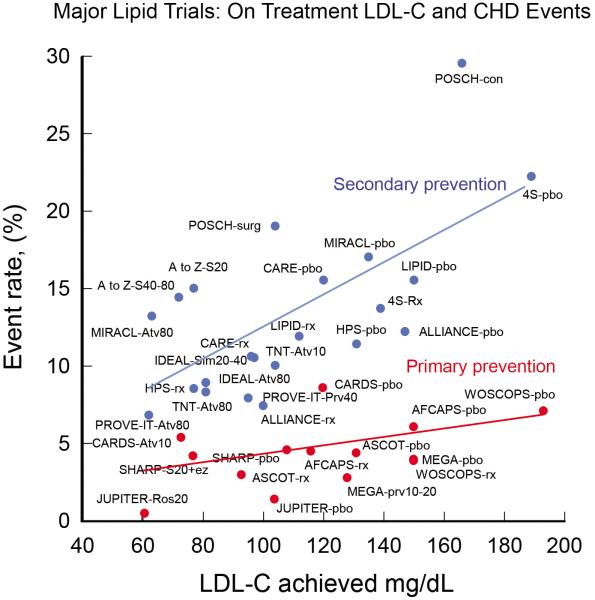

The new guidelines further do not support combination therapy along with statins although they do indicate that one may consider adding additional therapies. Would you be comfortable with this high-risk patient's LDL cholesterol on maximum statin therapy? Would you consider the addition of non-statin therapies? A preponderance of data shows that LDL-C plays a fundamental and causal role in ASCVD development and risks for adverse events. Genetic data demonstrates that LDL and the LDL receptor pathway are mechanistically linked to ASCVD pathogenesis, with lifetime exposure as the critical determinant of risk (5,6). Moreover, review of RCT for statins, as well as additional studies of cholesterol lowering, shows a reproducible relationship between LDL-C achieved and absolute risk (Figure 1). We believe this data serves as rationale for targeting LDL-C and establishing of goals to help guide physician and patient approaches toward the treatment of LDL-C.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot with best fit line of major lipid trials (statin and nonstatin trials) for both primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease events. Even though the trials were not designed to show differences based on a target LDL-C level, there is a clear relationship of lower events with lower LDL-C levels.

For these reasons we believe that the removal of LDL-C goals is a fundamental flaw in the new guidelines. The absence of RCT trial data demonstrating benefits of additional therapies added to statins or treating to specific goals is largley because these trials have not been designed or performed. Even non-pharmacological means of lowering LDL-C, such as the Program on the Surgical Control of the Hyperlipidemia (POSCH trial), which achieved LDL-C reduction by ileal bypass, provides independent evidence of LDL-C reduction leading to reduction in ASCVD risks (Figure 1). In addition, non-statin trials such as niacin in the coronary drug project also demonstrated outcome benefits. It is not surprising that studies such as AIM-HIGH and HPS2-THRIVE did not show additional ASCVD risk reduction when niacin was added to statin therapy since the study design required aggressive LDL lowering with statins +/− ezetimibe with LDL-C levels below 70–80 mg/dL before randomization (7,8). The completed trials with add on therapies such as these also do not address the question raised by this patient: what to do with the patient on maximal intensive therapy with recurrent ASCVD events or with LDL-C above prior target levels?

We would recommend adding a second medication in this case to further reduce LDL-C. An honest discussion with the patient regarding the absence of proven benefit in clinical trials and and potential risks of side effects is necessary. At present, in the absence of stated LDL-C goals in the newest guidelines, we are keeping with the ATPIII goals to help guide therapeutic choices and individualize patient management.

2. Individuals with LDL-C≥190 mg/dL

Advantages

Universally accepted that these patients should be treated with the highest tolerated statin dose.

Limitations

Guidelines only mention one `may consider' adding a second agent if LDL remains above 190 mg/dL after maximum dose therapy. Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia, or other severe forms of hypercholesterolemia, typically end up on multi-drug therapy to further reduce LDL-C for the above stated reasons. The absence of RCT data in this setting to demonstrate additive value of second and/or third lipid lowering agents does not mean these agents are not providing benefit.

3. Individuals with diabetes aged 40–75, LDL-C 70–189 mg/dL without clinical ASCVD

Advantages

More aggressively treat diabetics, which RCTs adequately show are at increased risk and a group that derives significant benefit from statin therapy.

Limitations

While high potency statin therapy is indicated for this group, we believe there is also potential with the current risk calculator for overly aggressive treatment than may be needed in some, thus increasing the possibility of statin side effects.

Does not address patients <40 years old, or >75

Diabetic patients have a high residual risk of ASCVD events even on statin therapy, ignoring potential benefits of more aggressive LDL cholesterol lowering or non-LDL secondary targets for therapy.

Case example 2

A 63 year old white female, nonsmoker with recently diagnosed diabetes is seen by her PCP. She has a history of HTN and is on lisinopril 5 mg. Fasting Lipids: TC 160, HDL-C 54, TG 80, and calculated LDL-C 70 mg/dL. Additional information includes systolic BP is 129 mmHg, and based on new risk calculator her 10 yr CVD risk is 10.2%. Per new guidelines she should be started on high potency statin (Table 1).

Starting this patient with such a high potency statin dose is an acceptable initial course of action, but necessitates close vigilance since it is conceivable that this subject may respond with actually a LDL-C that is too low. RCT have typically used LDL-C ≤ 25mg/dL as the safety cutoff. With a typical LDL-C reduction of 55% on this dose of atorvastatin, the expected LDL-C of the subject will likely be in the low 30s. We believe this is a good outcome provided the subject tolerates the medication without adverse side effects. However, responses to statins show subject to subject variations, and close monitoring to ensure LDL-C does not dip too low in this individual would be warranted.

Intensive statin therapy may not be necessary to achieve adequate risk reduction in diabetics without previous vascular disease. If we base recommendations on RCTs, the CARDS (Collaborative AtoRvastatin Diabetes Study) trial was a primary prevention study that specifically examined the role of 10 mg atorvastatin vs placebo in Type II diabetics aged 40–75 years with one or more cardiovascular risk factor but no signs or symptoms of pre-existing ASCVD and who had only average or below average cholesterol levels (9) – precisely as in Case 2. The trial was terminated early because of the clear benefit (37% reduction in composite of major adverse cardiovascular events) demonstrated for the intervention group. For this case we believe an alternative and acceptable approach would have been to begin a low to moderate dose statin (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Low-Intensity Statins

| Low-Intensity Statin Therapy (Lowers LDL-C by <30%) |

|---|

|

|

|

Indicated for: None.

|

Adaptation from new guidelines. No recommendations are provided for Low-Intensity statin use

Alternatively, in a diabetic with previous atherosclerotic vascular disease or with a high ten-year risk, limiting treatment to high intensity statin therapy only may deny potential benefits of combination therapies and targeting to lower LDL-C levels or non-LDL -C secondary targets. Other current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists continue to recommend LDL-C goal assessment less than 70 mg/dL in high-risk patients, non-HDL-C cholesterol less than 100 mg/dL, ApoB less than 80 mg/dL and LDL particle number less than 1000 mmol/L (10,11).

4. Individuals aged 40–75, LDL-C 70–189 mg/dL, without ASCVD but estimated 10 yr CVD risk of ≥7.5%

Advantages

Potential to reduce ASCVD events for higher risk patients. This is dependent on the physician's belief in the risk calculator.

Risk calculator is easy to use, and focuses on global risk

Promote risk/benefit discussion between patients and providers.

Limitations

Controversial risk calculator (see below)

Potential for over-treatment, particularly with older patients

Potential for under-treatment, particularly those with elevated LDL-C yet ≤7.5% 10 year risk because they are too young.

Does not address patients <40 years old, or >75

Does not account for some traditional risk factors (family history) and nontraditional risk factors (usCRP, Lp(a), apo-B).

Risk calculator controversy

Interpretation of the new ASCVD risk calculator has caused strong opinions on either side of the aisle. Shortly after the new guidelines were released, cardiologists Dr. Paul Ridker and Dr. Nancy Cook from Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston published data showing the new risk calculator, which was based upon older data from the several large cohorts like the ARIC study, Cardiovascular Health Study, CARDIA study and Framingham study, inaccurately calculated risks in alternative cohorts (12–16). Specifically, when compared to more recent health cohorts (Women's Health Study, Physicians' Health Study and Women's Health initiative) the risk calculator overestimates 10 yr ASCVD risk by 75–150% (17). Utilizing the new calculator would lead to approximately 30 million new Americans eligible for statin treatment. The concern is that lower risk patients would be treated and exposed to potential side effects of statin therapy. Besides being based largely upon older prospective studies, the risk calculator places a high emphasis on age, gender and does not include other factors such as triglycerides, family history, ultra-sensitive CRP or Lp(a) as utilized in other scoring systems. Importantly, and somewhat ironically given the otherwise absolute adherence to RCT data for guideline development, the risk calculator has never been verified in prospective studies to adequately show, if implemented, it will reduce ASCVD events.

Case Example 3 – Primary Prevention patient and over-treatment

Using the risk calculator, essentially any African American male, in his early 60s with no other risk factors has a 10 yr ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5% and per new guidelines, should be on at least moderate dose statin therapy. For example, a 64 year old AA male presents with SBP 120 mmHg, non-smoker, no DM, no HTN, TC 180, HDL 70, TG 130 and calculated LDL 84 mg/dL. The calculated 10yr risk for this patient, surprisingly is 7.5%.

Alternatively, his twin brother is a 2 pack-per-day smoker, has HTN and SBP of 140 mmHg, with fasting lipids revealing TC 130, HDL 70, TG 60 and LDL-C 48 mg/dL. His calculated 10 yr ASCVD risk is a remarkable 24%, leading again to high potency statin recommendation. Yet this individual clearly warrants improved BP control and most importantly, smoking cessation as the primary preventive risk reduction efforts, not addition of a statin in the setting of an LDL in the 40s (we recognize these lipids are unusually low, but provide them as an example of how erroneous the risk calculator could be).

Because of the errors inherent in the risk calculator, many experts have been calling for a temporary halt on implementing the guidelines until further verification of the risk calculator can be performed. During the AHA annual convention in November 2013, the AHA and ACC responded during a press conference in support of the new guidelines and recommended they be implemented as planned. As of the time this manuscript went to the printers, there currently are no plans to halt the guidelines.

Case Example 4 – Primary Prevention patient and under-treatment

A 25 year old white male with no prior medical history has a TC of 310, HDL 50, TG 400 with a calculated LDL of 180 mg/dL. He does not smoke, have HTN or DM, but has a strong family history of premature coronary disease (father died of MI at age 42). BMI is 25 kg/m2. Because he is under 40 years old, the risk calculator is not applicable.

If we assume he remained untreated and now returns at age 40 with the same clinical and laboratory parameters, his calculated 10 yr ASCVD event risk with the new risk calculator is only 3.1%. Assuming his medical history remained unchanged, as he continued to age, his 10 yr ASCVD risk would not be ≥7.5% until he is 58. Would you feel comfortable waiting 33 years before starting statin therapy in this subject?

Waiting until middle age for dyslipidemic subjects before recommending initiation of LDL-C lowering therapy, is a failure of prevention. The strict adherence to RCT data, which is for practical reasons devoid of hard outcome data in younger individuals, results in ignoring the major tenets of preventive cardiovascular medicine, which is that genetic and epidemiologic data supports it's the cumulative exposure that accelerates the “vascular age” ahead of chronological age. This is why individualized tailored preventive risk reduction recommendations guided by LDL-C goals as a target for therapy are needed. For the 25 year old we would recommend starting an intermediate or high potency statin.

Case example 5

A 60 year old post-menopausal Caucasian female with severe rheumatoid arthritis presents for cholesterol evaluation. Her TC is 235, HDL 50, and LDL-C is 165 mg/dL. She does not smoke, have hypertension or diabetes. SBP is 110 mmHg. She has an elevated ultra-sensitive CRP and Lp(a). Her 10 yr ASCVD risk is 3.0%. Assuming her medical history remains the same she would not reach an ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% until age 70. We suggest starting high dose statin therapy in this case due to non-RCT data showing increased ASCVD event risk in patients with rheumatologic disease, increased Lp(a) and inflammatory markers like usCRP. However, the current guidelines do not address this scenario other than to suggest additional clinician consideration can be given to other risk markers like CRP, apo-B, Lp(a) and these findings should be discussed in detail with the patient. The JUPITER trial showed a dramatic ASCVD risk reduction in just such a patient (Figure 1).

FINAL THOUGHTS

The newest guidelines for treatment of blood cholesterol represent a monumental shift in the approach to lowering cholesterol from target levels of LDL-C and non-HDL-C to a focus on statin intensity for those individuals who fall in the 4 highest risk groups. We must applaud the expert panel for the idealistic approach to use only RCT data, placing increased emphasis on higher dose statins, including stroke in the new definition of ASCVD and drawing increased attention to more aggressively treating diabetics. The goal of simplifying the cholesterol guidelines with RCT data is noble. Emphasizing the importance of moderate to high intensity statin therapy in moderate to high-risk individuals should have substantial long-term public health benefits. However, as seen in the case examples there are some significant limitations with the potential to both over-treat and under-treat depending on the clinical scenario.

Guidelines need to be crafted by looking at the totality of data, not just RCT results, including the pathophysiology of the disease process. It is difficult to implement a guideline where RCT was used exclusively for recommendations on one hand, but on the other hand use an untested risk calculator to guide therapy. RCT studies are not available for every scenario. Further, the absence of RCT data for a given scenario should not be interpreted as evidence for lack of benefit. The prime example of this is the <40 year old primary prevention patient with elevated LDL-C below the 190 mg/dL cutoff who otherwise is healthy and without risk factors (Case example 4). By disregarding all non RCT evidence, the expert panel fails to account for the extensive pathophysiology of ASCVD that often begins at a young age and takes decades to develop (18). An entire generation of patients that have not reached RCT data age are excluded (unless LDL-C levels are very high), potentially setting back decades worth of progress made in the prevention field. Prevention only works if started. With childhood and young adult obesity sharply rising, we should not fail to address the <40 year old patient population in our guidelines.

Guidelines are designed to be expert opinion, not to dictate practice. Focusing on the individual patient instead of the general population at risk. The expert panel appropriately emphasizes the `importance of clinician judgment, weighing potential benefits, adverse effects, drug-drug interactions and patient preferences.' However, by excluding all non-RCT data, the panel neglects a very large base of knowledge and leaves many clinicians without as much expert opinion as we had hoped.

LDL-C goals are important. They provide a metric to the patient to help with lifestyle / dietary changes. They provide the health provider much needed guidance in treatment decisions and focusing on treatment of the patient, not the population. Moreover, if a patient has difficulty taking standard dosing of statins because of adverse side effects, the absence of LDL-C goals makes decision-making near impossible. We hope physicians will rely on LDL-C goals in such situations, falling back to ATPIII recommendations, though there of course exists the probability that many subjects will simply be under-treated, until they present with ASCVD or “age-in” to a higher risk category.

We suggest caution in strict adherence to the new guidelines and consider a more hybrid adoption of the old (LDL-C goals) and new (global risk assessment, and high intensity statins) guidelines.

References

- 1.National Cholesterol Education Panel Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–39. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone NJU, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. published online Nov 13. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Last accessed on December 5th, 2013];2013 Prevention Guidelines Tools: CV Risk Calculator. http://my.americanheart.org/professional/StatementsGuidelines/PreventionGuidelines/Prevention-Guidelines_UCM_457698_SubHomePage.jsp.

- 5.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. History of Discovery: The LDL Receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009 Apr;29(4):431–438. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. PCSK9: a convertase that coordinates LDL catabolism. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S172–177. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800091-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AIM-HIGH Investigators. Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, et al. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group Eur Heart J. 2013 May;34:1279–91. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, et al. on behalf of the CARDS Investigators Lancet. 2004;364:685–696. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(suppl 1):S11–S66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay Jl, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists'comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2013 consensus statement—executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2013;19:536–57. doi: 10.4158/EP13176.CS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawber TR, Kannel WB, Lyell LP. An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: the Framingham study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;107:539–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb13299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Annals of epidemiology. 1991;1:263–76. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1105–16. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Investigators TA. The Atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridker PM, Cook NR. Statins: new American guidelines for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62388-0. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62388-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strong JP, Malcom GT, Oalmann MC, et al. The PDAY study: Natural History, Risk Factors, and Pathobiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997 Apr 15;811:226–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]