Abstract

Aims/Introduction: Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus often require treatment with more than one oral antihyperglycemic agent to achieve their glycemic goal. The present study was carried out to assess the efficacy and safety of sitagliptin as add‐on therapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled (HbA1c ≥ 6.9% and <10.4%) on pioglitazone monotherapy (15–45 mg/day).

Materials and Methods: In the initial 12‐week, double‐blind treatment period, patients were randomized (1:1) to sitagliptin 50 mg/day (n = 66) or placebo (n = 68), followed by a 40‐week open‐label treatment period in which all patients received sitagliptin 50 mg/day that could have been increased to 100 mg/day for patients meeting predefined glycemic parameters.

Results: After 12 weeks, mean changes from baseline in HbA1c (the primary end‐point), fasting plasma glucose and 2‐h post‐meal glucose were −0.8%, −0.9 mmol/L and −2.7 mmol/L, respectively, in the sitagliptin group compared with placebo (all P < 0.001). The incidence of adverse experiences during the double‐blind treatment period was similar in both treatment groups, and the incidences of hypoglycemia and gastrointestinal adverse experiences were low. In the open‐label period, improvements in glycemic parameters with sitagliptin treatment were maintained and sitagliptin was generally well tolerated.

Conclusions: Sitagliptin as add‐on therapy provided significant improvements in glycemic parameters and was well tolerated in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on pioglitazone monotherapy. This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (no. NCT00372060). (J Diabetes Invest, doi: 10.1111/j.2040‐1124.2011.00120.x, 2011)

Keywords: Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor, Incretins, Sitagliptin

Introduction

Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitors, a new therapeutic class of agents, target the incretin axis for the treatment of type 2 diabetes1,2. Incretins are released by the intestine at basal levels throughout the day, and secretion significantly increases in response to a meal; however, incretins are rapidly degraded by the peptidase enzyme, DPP‐4. DPP‐4 inhibitors stabilize the intact forms of the incretin hormones glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) and glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)3,4. Intact GLP‐1 and GIP play an important role in glycemic homeostasis5 through multiple physiological actions including stimulation of insulin secretion (GLP‐1 and GIP) and suppression of glucagon secretion (GLP‐1), both in a glucose‐dependent fashion.

Sitagliptin is a highly selective DPP‐4 inhibitor dosed once daily. Several large, randomized, placebo‐controlled trials have shown that sitagliptin in monotherapy or in combination with other oral antihyperglycemic agents (AHA)6–12 provides significant improvements in key glycemic parameters, including fasting and postprandial glucose and HbA1c, relative to placebo, and is generally well tolerated.

Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ (PPARγ) agonists act primarily by decreasing insulin resistance in the liver and peripheral tissues. Pioglitazone is a PPARγ agonist widely used to treat type 2 diabetes13 that has been shown to be effective as an AHA in large, randomized, placebo‐controlled trials14,15.

A previous study, carried out outside of Japan, showed that the addition of sitagliptin to ongoing pioglitazone therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes improves glycemic control compared with placebo and is well tolerated12. Because the pathological mechanisms underlying type 2 diabetes might be different in Japanese patients compared with patients from other ethnic and genetic backgrounds16–19, the present study assessed the efficacy and safety of sitagliptin as an add‐on to pioglitazone therapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were men and women ≥20 years of age with type 2 diabetes being treated with pioglitazone (15–45 mg/day) as monotherapy or in combination with other oral AHA. Major exclusion criteria included: history of type 1 diabetes, recent treatment with insulin, the presence of progressive diabetes complications, unstable cardiovascular disease or uncontrolled severe hypertension, increased serum creatinine (>132.6 μmol/L in men or >114.9 μmol/L in women), increased alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase >2‐fold the upper limit of normal, hemoglobin <110 g/L in men or <100 g/L in women, or body mass index (BMI) <18 or >40 kg/m2.

Study Design and Procedures

This was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial carried out at 32 sites in Japan. The study included an initial 12‐week, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind treatment period that assessed the primary efficacy hypothesis, followed by a 40‐week, open‐label treatment period during which all patients received sitagliptin.

At screening, patients on a stable regimen of diet/exercise for at least 6 weeks and a stable dose of pioglitazone for at least 14 weeks (with the final 8 or more weeks as monotherapy only) and who met all eligibility criteria, including having a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) value ≥6.9% and <10.4% (HbA1c [%] value is calculated by the formula HbA1c [%] = HbA1c [Japan Diabetes Society (JDS)] [%] + 0.4%, considering the relational expression of HbA1c [JDS] [%] measured by the previous Japanese standard substance and measurement methods and HbA1c [National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program])20 could directly enter a 2‐week, single‐blind, placebo run‐in period. Otherwise, patients on combination therapy with pioglitazone and other oral AHA who met all eligibility criteria, with HbA1c values ≥6.4% and ≤9.4%, entered a 6‐week wash‐off period of non‐pioglitazone AHA after which they could enter the placebo run‐in period. This design ensured that all patients received at least 8 weeks of diet/exercise therapy and at least 16 weeks of pioglitazone therapy at a stable dose (with the final 8 or more weeks as monotherapy only) before randomization. All patients were instructed to follow a stable program of diet and exercise for the duration of the study.

Patients were eligible for randomization if they had a HbA1c ≥ 6.9% and <10.4%, and a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≤ 15.0 mmol/L just before initiating the placebo run‐in and ≥75% treatment compliance (based on pill counts) during the placebo run‐in. Eligible patients were randomized (1:1) to either sitagliptin 50 mg/day or matching placebo for 12 weeks in a double‐blind fashion, using a computer‐generated allocation schedule.

On completion of the double‐blind period, patients entered a 40‐week, open‐label treatment period. Patients who received sitagliptin during the double‐blind period continued to do so in the open‐label period (S/S group). Patients who received the placebo in the double‐blind period were started on sitagliptin 50 mg/day at entry to the open‐label period (P/S group). Regardless of group, patients had their sitagliptin dose increased to 100 mg/day at the next study visit if FPG was ≥7.8 mmol/L on or after week 16, or if HbA1c was ≥7.4% on or after week 24; after week 40, the sitagliptin dose remained stable until study end. Investigators could decrease the sitagliptin dose to 50 mg/day if treatment with 100 mg/day was not considered to be well tolerated. Patients were required to be discontinued from the study if FPG was consistently (on two consecutive determinations) >15.0 mmol/L at any time during the study or if HbA1c was consistently >8.4% at or after week 40.

Meal tolerance tests were carried out at weeks 0, 12 and 52, beginning 30 min after administration of the study drug (at week 0 patients received a dose of the matching placebo). The test meal contained approximately 500 kcal (60% carbohydrate, 15% protein and 25% fat), and was to be consumed within 15 min. Blood samples were drawn before beginning the test meal and 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 h after beginning the meal.

The present study was designed and carried out in accordance with the guidelines on good clinical practice and ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each study site. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study End‐points

The primary efficacy end‐point was change from baseline in HbA1c at week 12. Secondary end‐points were change from baseline in FPG and 2‐h post‐meal glucose (2‐h PMG) at week 12. In the open‐label period, HbA1c, FPG and 2‐h PMG were assessed as exploratory end‐points. Additional exploratory end‐points included fasting 1,5‐anhydroglucitol (1,5‐AG), insulin, homeostasis model assessment of β‐cell function (HOMA‐β), homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA‐IR)21, 2‐h post‐meal insulin, post‐meal glucose area under the concentration‐versus‐time curve (AUC), insulin AUC, C‐peptide AUC and insulinogenic index22 assessed at both weeks 12 and 52. The proportions of patients with HbA1c values meeting the therapeutic goals of <7.4% and <6.9%, (corresponding to 7.0 and 6.5% in HbA1c [JDS], respectively) were also assessed at weeks 12 and 52.

Adverse experiences (AE) were monitored throughout the study up to 2 weeks post‐treatment, and investigators rated their intensity and relationship to the study drug. Hypoglycemia and selected gastrointestinal AE (nausea, vomiting and diarrhea) were predefined for additional analyses. Hypoglycemia was diagnosed by the investigators based on their assessment of patients’ reports. Patients were instructed to notify the investigator immediately if they had symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia (e.g. sweating, anxiety, palpitations, blurred vision, loss of consciousness) that required assistance or if they had self‐monitoring blood glucose values <3.3 or >15.0 mmol/L. Safety and tolerability were also assessed during the study by physical examination, monitoring of vital signs, and safety laboratory tests, including hematology, serum chemistry and urinalysis.

Laboratory assays were carried out at one central laboratory (Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Methods

Efficacy

The efficacy analysis was carried out on the full analysis set (FAS) population composed of all randomized patients who had taken at least one dose of the study drug and had both the baseline and at least one post‐randomization measurement. An analysis of covariance (ancova) model was used to compare treatment groups for continuous efficacy parameters, focusing on change from baseline at week 12, with treatment group, baseline values and prior oral AHA status other than pioglitazone (on or not on) as covariates. Missing values of HbA1c and FPG were imputed by the last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF) method; missing values for 2‐h PMG were not imputed. The between‐group difference in least squares (LS) mean and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated with an alpha level of <0.05 (two‐sided) considered statistically significant. The proportions of patients with HbA1c values meeting the predefined HbA1c goals were analyzed using a logistic regression model that included treatment group, prior oral AHA status and baseline HbA1c as covariates.

To assess the consistency of the HbA1c‐lowering effect of sitagliptin across subgroups, between‐group differences in LS mean changes from baseline and 95% CI were estimated using the ancova model described earlier for each subgroup defined by prior oral AHA status other than pioglitazone (on or not on), baseline HbA1c (≤8.4 or >8.4%), age (<65 or ≥65 years), sex, BMI (<25 or ≥25 kg/m2), duration of type 2 diabetes (<median or ≥median), fasting insulin (<median or ≥median), HOMA‐IR (<median or ≥median) and HOMA‐β (<median or ≥median). For these analyses, the ancova model did not include the covariates of baseline HbA1c value and prior oral AHA status for each subgroup variable.

For longer‐term assessment of efficacy, summary statistics for efficacy end‐points were provided, by treatment group (P/S or S/S), at each time‐point in which the end‐point was measured up to week 52; missing values were not imputed. At week 52, the within‐group mean change from baseline for all efficacy end‐points was assessed using a paired t‐test.

The effect of uptitrating the sitagliptin dose to 100 mg/day was assessed (post‐hoc). Among patients whose sitagliptin dose was increased and whose HbA1c value at the time of uptitration was ≥7.4%, the proportion of patients with HbA1c values <7.4% 12 weeks after uptitration was tabulated. Additionally, for patients whose sitagliptin dose was increased and who completed the study, the proportion of patients with HbA1c values <7.4% at week 52 was also assessed. For these analyses, missing values were not imputed.

Safety

Safety and tolerability analyses were carried out on the all‐patients‐as‐treated (APaT) population, which included randomized patients who received at least one dose of the double‐blind study drug. In the double‐blind period, between‐group comparisons using Fisher’s exact test were carried out for incidences of overall (one or more) AE, drug‐related clinical AE, hypoglycemia and prespecified gastrointestinal AE. The analysis of change from baseline in bodyweight was carried out (post‐hoc) using an ancova model similar to that used for the efficacy end‐points.

For longer‐term safety assessment, the patient population included all patients who received at least one dose of sitagliptin after week 12. The incidences of overall AE, drug‐related AE, hypoglycemia and selected gastrointestinal AE were summarized. Within‐group mean change from baseline in bodyweight was assessed using a paired t‐test at week 52.

Results

Of the 165 patients screened, 134 were randomized to treatment (66 to sitagliptin and 68 to placebo; Figure 1). Demographic, anthropometric and disease characteristics were generally similar in both treatment groups, except for a greater proportion of females in the sitagliptin group (42%) compared with the placebo group (28%; Table S1). Patients had a baseline mean HbA1c of 8.1%, the average duration of known diabetes was 7.9 years and the mean BMI was 26.4 kg/m2.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. Patients in the P/S group received placebo during the double‐blind period and sitagliptin 50 or 100 mg in the open‐label period. Patients in the S/S group received sitagliptin in both periods. *One patient who discontinued for lack of efficacy at week 50 was included in the efficacy analyses at week 52, thus increasing the group size to 50 patients.

A total of 130 patients completed the double‐blind period and entered the open‐label period; of those, 108 patients subsequently completed the open‐label period (Figure 1). All randomized patients were included in the FAS and in the APaT populations for analysis.

Efficacy

Double‐blind period (weeks 0 through 12)

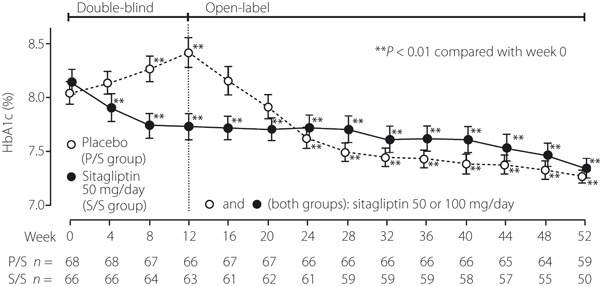

In Japanese patients receiving pioglitazone therapy, the addition of sitagliptin resulted in a significant (P < 0.001) reduction from baseline in HbA1c compared with the placebo at week 12 (Table 1, Figure 2). Additionally, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the sitagliptin group relative to the placebo group had HbA1c values <7.4% (43% vs 12%, respectively; P < 0.001), and <6.9% (17% vs 3%, respectively; P < 0.01). The effect of sitagliptin was generally consistent in all patient subgroups examined.

Table 1. Results for fasting and post‐meal glycemic end‐points at week 12 (double‐blind period).

| n | Week 0 mean (SD) | Week 12 mean (SD) | Change from week 0 to 12 (LS mean [95% CI]) | Between‐group difference (LS mean [95% CI]) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c† (%) | |||||

| Placebo | 68 | 8.0 (0.8) | 8.4 (1.2) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.5)*** | −0.8 (−1.0 to −0.6)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 66 | 8.1 (0.9) | 7.7 (1.0) | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.3)*** | |

| Fasting plasma glucose† (mmol/L) | |||||

| Placebo | 68 | 8.54 (1.9) | 8.6 (2.1) | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.5) | −0.9 (−1.3 to −0.6)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 66 | 8.2 (1.8) | 7.5 (1.5) | −0.7 (−0.9 to −0.4)*** | |

| 1,5‐anhydroglucitol† (μg/mL) | |||||

| Placebo | 68 | 6.5 (5.3) | 6.2 (5.5) | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.3) | 3.7 (2.8 to 4.5)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 66 | 6.0 (4.2) | 9.4 (5.9) | 3.4 (2.8 to 4.0)*** | |

| Fasting insulin† (pmol/L) | |||||

| Placebo | 68 | 48.7 (26.6) | 45.4 (26.3) | −2.9 (−6.5 to 0.7) | 6.8 (1.6 to 11.9)* |

| Sitagliptin | 66 | 44.4 (24.0) | 48.6 (25.6) | 3.9 (0.2 to 7.5)* | |

| HOMA‐IR† | |||||

| Placebo | 68 | 2.7 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.5) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.1) | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.4) |

| Sitagliptin | 66 | 2.4 (1.5) | 2.4 (1.4) | 0.0 (−0.2 to 0.2) | |

| HOMA‐β† | |||||

| Placebo | 68 | 31.5 (17.8) | 29.3 (19.1) | −2.2 (−5.1 to 0.7) | 9.8 (5.7 to 14.0)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 66 | 29.8 (17.2) | 37.6 (21.0) | 7.6 (4.7 to 10.6)*** | |

| 2‐h Post‐meal glucose‡ (mmol/L) | |||||

| Placebo | 67 | 13.2 (3.7) | 13.5 (3.8) | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.9) | −2.7 (−3.6 to −1.9)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 63 | 12.8 (3.2) | 10.5 (2.9) | −2.4 (−3.0 to −1.8)*** | |

| 2‐h Post‐meal insulin‡ (pmol/L) | |||||

| Placebo | 67 | 302.4 (178.2) | 271.5 (159.4) | −27.4 (−54.4 to −0.5)* | 55.4 (16.6 to 94.2)** |

| Sitagliptin | 63 | 271.7 (135.0) | 303.2 (170.6) | 28.0 (0.2 to 55.8)* | |

| Glucose AUC‡ (mmol h/L) | |||||

| Placebo | 67 | 25.2 (5.6) | 25.6 (5.5) | 0.5 (−0.2 to 1.3) | −4.2 (−5.3 to −3.0)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 63 | 24.6 (4.4) | 21.0 (4.0) | −3.6 (−4.4 to −2.8)*** | |

| Insulin AUC‡ (pmol h/L) | |||||

| Placebo | 67 | 460.5 (254.2) | 416.7 (212.1) | −41.7 (−69.8 to −13.6)** | 84.8 (44.4 to 125.2)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 63 | 434.5 (207.9) | 479.9 (239.9) | 43.1 (14.1 to 72.1)** | |

| C‐peptide AUC‡ (nmol h/L) | |||||

| Placebo | 67 | 3.0 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.9) | −0.2 (−0.4 to −0.1)*** | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.5)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 63 | 3.0 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.0) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3)* | |

| Insulinogenic index‡ | |||||

| Placebo | 66 | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.0) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3)*** |

| Sitagliptin | 63 | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2)*** | |

†Missing data were imputed using the last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF) method. ‡Missing data were not imputed (i.e. LOCF method was not used). ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. AUC, total area under the concentration‐versus‐time curve; CI, confidence interval; HOMA‐β, homeostasis model assessment of β‐cell function; HOMA‐IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; LS, least squares; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Time course of HbA1c in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Patients in the P/S group received placebo during the 12‐week double‐blind period and open‐label sitagliptin in the 40‐week open‐label period. Patients in the S/S group received sitagliptin (50 or 100 mg/day) for the subsequent 40 weeks. The data are shown as mean ± SE. In the double‐blind period, the method of last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF) was used to impute values for HbA1c. In the open‐label period, statistics for HbA1c were calculated without LOCF, using at each time‐point the data available for that specific time‐point. The sample sizes at each time‐point are shown beneath the plots. **P < 0.01 compared with week 0.

Both FPG and 2‐h PMG were also significantly (P < 0.001) improved by sitagliptin treatment at week 12 (Table 1).

Results from the analysis of changes from baseline in other efficacy parameters between the treatment groups at week 12 were supportive of the primary and secondary findings, including a significant improvement in 1,5‐AG with sitagliptin treatment (Table 1).

Open‐label period (weeks 12 through 52)

Consistent with the double‐blind period, HbA1c, FPG and 2‐h PMG showed improvements from baseline through week 52 in the S/S and P/S groups (all P < 0.001, Table 2, Figures S1–S3). Significant changes (P < 0.05) in other efficacy parameters including 1,5‐AG, HOMA‐β, post‐meal AUC of glucose, insulin, C‐peptide and the insulinogenic index were also observed in both the S/S and P/S group at week 52.

Table 2. Results for fasting and post‐meal end‐points at week 52.

| n | Week 0 mean (SD) | Week 52 mean (SD) | Change from week 0 (baseline) to week 52 (mean [95% CI]) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 7.8 (0.6) | 7.2 (0.5) | −0.6 (−0.7 to −0.4)*** |

| S/S | 50 | 8.0 (0.7) | 7.3 (0.7) | −0.6 (−0.8 to −0.5)*** |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 8.0 (1.6) | 7.3 (1.3) | −0.7 (−1.0 to −0.4)*** |

| S/S | 50 | 7.8 (1.4) | 7.2 (1.1) | −0.7 (−1.0 to −0.4)*** |

| 1,5‐anhydroglucitol (ug/mL) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 7.2 (5.3) | 12.0 (7.4) | 4.8 (3.8 to 5.9)*** |

| S/S | 50 | 6.5 (4.2) | 11.4 (6.4) | 5.0 (3.8 to 6.2) *** |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 47.9 (26.0) | 52.3 (27.8) | 4.4 (−1.0 to 9.7) |

| S/S | 50 | 43.8 (20.3) | 47.9 (21.0) | 4.1 (−0.7 to 8.8) |

| HOMA‐IR | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.6) | 0.0 (−0.3 to 0.4) |

| S/S | 50 | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.1) | 0.0 (−0.3 to 0.2) |

| HOMA‐β | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 33.0 (17.9) | 42.5 (26.2) | 9.4 (4.6 to 14.3)*** |

| S/S | 50 | 30.8 (17.1) | 39.9 (19.4) | 9.0 (4.5 to 13.5)*** |

| 2‐h Post‐meal glucose (mmol/L) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 12.4 (3.2) | 9.8 (2.3) | −2.6 (−3.4 to −1.8)*** |

| S/S | 50 | 12.3 (3.0) | 9.6 (2.3) | −2.7 (−3.4 to −2.0)*** |

| 2‐h Post‐meal insulin (pmol/L) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 312.2 (183.6) | 316.3 (190.1) | 4.1 (−33.3 to 41.5) |

| S/S | 50 | 278.9 (132.8) | 307.1 (183.1) | 28.2 (−11.4 to 67.9) |

| Glucose AUC (mmol h/L) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 23.9 (4.7) | 20.1 (3.6) | −3.8 (−4.9 to −2.7)*** |

| S/S | 50 | 23.9 (4.2) | 20.3 (3.7) | −3.5 (−4.5 to −2.6)*** |

| Insulin AUC (pmol h/L) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 465.5 (242.7) | 498.0 (245.4) | 32.5 (−4.2 to 69.2) |

| S/S | 50 | 445.5 (213.5) | 490.9 (260.0) | 45.4 (1.9 to 88.8)* |

| C‐peptide AUC (nmol h/L) | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 3.1 (1.0) | 3.6 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7)*** |

| S/S | 50 | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6)*** |

| Insulinogenic index | ||||

| P/S | 59 | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2)*** |

| S/S | 50 | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2)*** |

***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. Missing data were not imputed. AUC, total area under the concentration‐versus‐time curve; CI, confidence interval; HOMA‐β: homeostasis model assessment of β‐cell function; HOMA‐IR: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; P/S, patients received placebo in double‐blind period and sitagliptin in open‐label period; SD, standard deviation; S/S, patients received sitagliptin in double‐blind and open‐label periods.

The sitagliptin dose was uptitrated in 42 (67%) patients in the S/S group and 41 (61%) patients in the P/S group. Among those who had a HbA1c ≥7.4% at the time of uptitration (69 patients), 17 patients (25%) had a HbA1c value of <7.4% 12 weeks after uptitration. A total of 64 (77%) patients who had their sitagliptin dose increased completed the 52 weeks of study; 30 (47%) of them had HbA1c <7.4% at study end.

Safety

Double‐blind period (weeks 0 through 12)

The incidences of clinical AE, laboratory AE, drug‐related AE and serious AE were similar in both treatment groups (Table 3). No laboratory AE were considered drug‐related by the investigator and none was reported as a serious AE. Two (3%) patients in the sitagliptin group (coronary artery stenosis and cerebral infarction, respectively) and none in the placebo group discontinued as a result of serious clinical AE, but neither of these AE was considered drug‐related by the investigator. Both of these patients were at increased risk for ischemic cardiovascular disease based on their medical history.

Table 3. Safety and tolerability results.

| Weeks 0–12† (double‐blind) | Weeks 12–52 (open‐label) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 68) | Sitagliptin (n = 66) | P/S (n = 67) | S/S (n = 63) | |

| No. patients (n [%]) who had one or more | ||||

| Clinical AE | 39 (57.4) | 38 (57.6) | 54 (80.6) | 52 (82.5) |

| Drug‐related clinical AE‡ | 5 (7.4) | 4 (6.1) | 3 (4.5) | 6 (9.5) |

| Serious clinical AE‡ | 1 (1.5) | 3 (4.5) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (1.6) |

| Drug‐related serious clinical AE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of patients (n [%]) who: | ||||

| Discontinued due to a clinical AE | 0 | 2 (3) | 0 | 3 (4.8) |

| Died | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of patients (n [%]) who had: | ||||

| Hypoglycemia | 2 (2.9) | 2 (3.0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.6) |

| Nausea, vomiting or diarrhea | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (3.2) |

| No. patients (n [%]) who had one or more: | ||||

| Laboratory AE | 5 (7.4) | 5 (7.6) | 16 (23.9) | 17 (27.0) |

| Drug‐related laboratory AE‡ | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.5) | 1 (1.6) |

| Serious laboratory AE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No. patients (n [%]) who | ||||

| Discontinued due to a laboratory AE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No. patients (n [%]) who had: | ||||

| Clinical AE§ | ||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 17 (25.0) | 11 (16.7) | 26 (38.8) | 16 (25.4) |

| Upper respiratory tract inflammation | 3 (4.4) | 9 (13.6) | 4 (6.0) | 12 (19.0) |

| Periodontitis | 0 | 0 | 5 (7.5) | 2 (3.2) |

| Weight increase | 0 | 2 (3.0) | 3 (4.5) | 6 (9.5) |

| Osteoarthritis | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 3 (4.5) | 4 (6.3) |

| Hypoesthesia | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 4 (6.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| Gastritis | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 5 (7.5) | 1 (1.6) |

| Joint sprain | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 4 (6.3) |

| Laboratory AE§ | ||||

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.5) | 9 (13.4) | 7 (11.1) |

| Blood triglycerides increased | 0 | 0 | 5 (7.5) | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 4 (6.3) |

| Blood lactate dehydrogenase increased | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 4 (6.3) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (7.9) |

†Fisher’s exact test was used to test the significance of differences in weeks 0–12 between numbers of patients in the sitagliptin and placebo groups reported to have one or more clinical adverse experience (AE) overall, drug‐related clinical AE, incidence of hypoglycemia, or prespecified gastrointestinal AE (nausea, vomiting and diarrhea). All between‐group differences were non‐significant. ‡Considered to be possibly, probably or definitely treatment‐related by the study investigators. §Specific AE for which there was a ≥5% incidence in either the sitagliptin or placebo group in the double‐blind period (from week 0 to 12), P/S or S/S group in the open‐label period (from week 12 to 52) were shown. P/S, patients received placebo in double‐blind period and sitagliptin in open‐label period; S/S, patients received sitagliptin in double‐blind and open‐label periods.

Hypoglycemia was reported at low and similar rates in both treatment groups; no patient required assistance to manage an episode of hypoglycemia, and no episode of marked severity was reported. Predefined gastrointestinal AE were also reported at low and similar incidences in both groups.

Nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract inflammation were the only specific AE reported, with a frequency ≥5% in either treatment group (Table 3), regardless of causality. Although AE of upper respiratory tract inflammation were reported more frequently in the sitagliptin group relative to the placebo group, no event was considered drug‐related by the investigator and none resulted in discontinuation.

The addition of sitagliptin or placebo to ongoing therapy with pioglitazone resulted in mean changes from baseline in bodyweight of 0.40 and −0.44 kg (both P < 0.001), respectively. No meaningful changes in other safety parameters were observed in either treatment group.

Open‐label period (weeks 12 through 52)

During the open‐label period, consistent with the longer period of observation in a patient population with type 2 diabetes, one or more clinical AE were reported for most patients in both the S/S and P/S groups (Table 3). Clinical AE reported with an incidence ≥5% in either group are shown in Table 3. Drug‐related clinical AE were reported in 10 and 5% of patients in the S/S and P/S groups, respectively; with the exception of constipation (two patients [2%]; both mild) in the S/S group, none of these events were reported to occur in more than one patient.

Serious AE were reported for one patient in the S/S group and three patients in the P/S group, all were considered not drug‐related by the investigator, and none was reported to occur in more than one patient. The incidence of hypoglycemia and gastrointestinal AE remained low and no episodes of severe hypoglycemia or events requiring assistance were reported through 52 weeks.

Laboratory AE were reported similarly in the S/S and P/S groups; none were serious, none led to discontinuation and few were reported as drug‐related (Table 3). The laboratory AE of increased blood creatine phosphokinase (CPK) was reported in 7 (11%) patients in the S/S group and 9 (13%) patients in the P/S group. Except for two patients in the S/S group with a slight elevation at the last study visit, all events of increased CPK were based on single elevations that resolved while the patients continued taking the study drug. No AE of increased CPK was considered drug‐related by the investigator. During the double‐blind period, laboratory AE of increased CPK were reported for 2 and 3% of patients in the sitagliptin and placebo groups, respectively. No significant mean changes from baseline in CPK levels were observed in either treatment group and there were no meaningful between‐group differences.

The incidences of clinical and laboratory AE did not change with uptitration of sitagliptin. The overall incidence of clinical AE was similar (67 patients [81%] and 114 patients [86%], respectively) between patients whose sitagliptin dose was uptitrated to 100 mg/day (n = 83) and the total patients (n = 130). The incidences of laboratory AE were similar as well (22 patients [27%] and 34 patients [26%], respectively). In no case was a patient’s sitagliptin dose downtitrated from 100 to 50 mg/day.

At week 52, mean changes from baseline in bodyweight of 0.76 kg (P < 0.01) and 0.82 kg (P < 0.01) were observed for the S/S group and P/S group, respectively (both P < 0.01). AE of increased bodyweight were reported for nine (7% of 130) patients overall, in whom the mean weight change from baseline was 5.3 kg. Overall, there were no meaningful changes from baseline in vital signs in the long‐term safety assessment of either group.

Discussion

In the present study, the addition of sitagliptin for 12 weeks provided a significant reduction in HbA1c relative to the placebo in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes who had inadequate glycemic control with pioglitazone monotherapy. The proportions of patients achieving the goals of HbA1c < 7.4 and <6.9% with sitagliptin treatment were four and sixfold larger, respectively, than with the placebo. Significant changes were also observed in FPG, 2‐h PMG and other efficacy parameters supporting the primary efficacy results. Although changes in 1,5‐AG might not reflect changes in glycemic control as accurately as glucose itself, especially in those patients with higher HbA1c at baseline, in the present study, 1,5‐AG results were consistent with those of the other more specific glycemic parameters.

Consistent with the literature, the results of the present study show a weaker association between type 2 diabetes and increased bodyweight for Japanese patients compared with non‐Japanese patients16–19. In the present study, the mean baseline BMI of 26.4 kg/m2 was lower than that seen in previous sitagliptin studies outside of Japan (>30 kg/m2)8,11,12,23. However, despite these differences, the improvement in glycemic parameters with sitagliptin in the present study is consistent with those from earlier studies of sitagliptin in monotherapy6,10 and as an add‐on to metformin7,11, pioglitazone12 and glimepiride8 in non‐Japanese patients. This is likely to be a result of the effect of sitagliptin on insulin secretion and hepatic glucose overproduction, two defects common in both Japanese and non‐Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes.

In the current study, the efficacy of sitagliptin, as reflected by changes in HbA1c, FPG and 2‐h PMG, remained stable for up to 52 weeks. Additionally, improvements in insulin secretion were reflected by changes in HOMA‐β, insulin AUC and insulinogenic index. These findings are clinically meaningful, but should be interpreted in the context of the current study design, in which the dose regimen of sitagliptin (50 mg/day) was uptitrated to 100 mg/day if patients met predefined glycemic parameters. This therapeutic approach provided clinically meaningful glucose‐lowering effects for up to 52 weeks in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with pioglitazone monotherapy.

The addition of sitagliptin to pioglitazone monotherapy was generally well tolerated over 12 weeks of treatment, with a safety profile similar to that of the placebo. As with efficacy, the assessment of safety data from the open‐label, uncontrolled period must be interpreted in the context of the current study design. Over 52 weeks, sitagliptin was well tolerated, with a safety profile consistent with that observed in a previous long‐term study of pioglitazone monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes24. In the present study, the incidence of hypoglycemia was low and similar in both treatment groups, and remained low throughout 52 weeks, consistent with the glucose‐dependant action of incretins5. The incidence of gastrointestinal AE was also low throughout the study period, with rates consistent with data from a previous study23. Continuous weight gain is a well‐known, dose‐related effect of treatment with PPARγ agonists14,25–29. In previous studies, it has generally been observed that treatment with sitagliptin is neutral with respect to bodyweight30. In the double‐blind period of the present study, a slight increase in bodyweight, that was statistically significant, was observed with sitagliptin treatment, compared with a small decrease with the placebo. This finding is not unexpected, as it is well known that poor glycemic control is associated with weight loss, as was observed in the placebo group, and the significant improvement in glycemic parameters observed with sitagliptin treatment might explain the small increase in bodyweight. Over the full 1 year of the study, both groups gained approximately 0.8 kg, which is consistent with the weight gain observed in other studies with pioglitazone14.

In conclusion, after 12 weeks of treatment, the addition of sitagliptin 50 mg/day to Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled by diet and exercise and ongoing pioglitazone therapy resulted in significant reductions from baseline in HbA1c and other efficacy parameters relative to the placebo. Furthermore, the improvements in HbA1c and other glycemic parameters observed early in the double‐blind treatment period of the present study appeared to remain stable throughout the 52 weeks. In addition, the findings in the present study suggest that sitagliptin uptitration to 100 mg provides further opportunity for patients to meet glycemic goals. The addition of sitagliptin to pioglitazone was generally well tolerated, with a low incidence of hypoglycemia and gastrointestinal AE, and a small increase in bodyweight.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 Time course of fasting plasma glucose (FPG).

Figure S2 Time course of meal tolerance results in P/S group.

Figure S3 Time course of meal tolerance results in S/S group.

Table S1 Baseline patient characteristics of randomized patients.

Appendix S1 MK‐0431‐PN055 Primary Investigators listing.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

The present study was sponsored by MSD K.K.; Merck & Co., Inc. (the manufacturer of sitagliptin); and by Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. A Kashiwagi was a principal investigator in the present study, and T Kadowaki and N Tajima served as consultants. K Nonaka, T Taniguchi, M Nishii, JC Arjona Ferreira and JM Amatruda are current or former employees of MSD K.K., ONO Pharmaceutical Co., and Merck & Co., Inc., respectively, and may own stock or stock options in Merck & Co., Inc. Merck & Co., Inc. is the manufacturer of sitagliptin. The authors thank Taro Okamoto, Asako Sato, Yukako Fukao and Kotoba Okuyama (all employees of MSD K.K.) for their contributions to the execution of the present study, and Ronald B Langdon (employee of Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) for assistance in writing this manuscript.

References

- 1.Herman GA, Stein PP, Thornberry NA, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: focus on sitagliptin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 81: 761–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karasik A, Aschner P, Katzeff H, et al. Sitagliptin, a DPP‐4 inhibitor for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes: a review of recent clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 489–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herman GA, Bergman A, Liu F, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effects of the oral DPP‐4 inhibitor sitagliptin in middle‐aged obese subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 46: 876–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herman GA, Bergman A, Stevens C, et al. Effect of single oral doses of sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor, on incretin and plasma glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91: 4612–4619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP‐1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 2131–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aschner P, Kipnes MS, Lunceford JK, et al. Effect of the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 2632–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charbonnel B, Karasik A, Liu J, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin alone. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 2638–2643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermansen K, Kipnes M, Luo E, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on glimepiride alone or on glimepiride and metformin. Diabetes Obes Metab 2007; 9: 733–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nonaka K, Kakikawa T, Sato A, et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008; 79: 291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raz I, Hanefeld M, Xu L, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2006; 49: 2564–2571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raz I, Chen Y, Wu M, et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 537–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenstock J, Brazg R, Andryuk PJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor sitagliptin added to ongoing pioglitazone therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 24‐week, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group study. Clin Ther 2006; 28: 1556–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn CE, Hamilton PK, Lockhart CJ, et al. Thiazolidinediones: effects on insulin resistance and the cardiovascular system. Br J Pharmacol 2008; 153: 636–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan MA, St Peter JV, Xue JL. A prospective, randomized comparison of the metabolic effects of pioglitazone or rosiglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes who were previously treated with troglitazone. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 708–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kipnes MS, Krosnick A, Rendell MS, et al. Pioglitazone hydrochloride in combination with sulfonylurea therapy improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Am J Med 2001; 111: 10–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen KW, Boyko EJ, Bergstrom RW, et al. Earlier appearance of impaired insulin secretion than of visceral adiposity in the pathogenesis of NIDDM. 5‐Year follow‐up of initially nondiabetic Japanese‐American men. Diabetes Care 1995; 18: 747–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DJ, Lee MS, Kim KW, et al. Insulin secretory dysfunction and insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of korean type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 2001; 50: 590–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto K, Miyake S, Yano M, et al. Glucose tolerance, insulin secretion, and insulin sensitivity in nonobese and obese Japanese subjects. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 1562–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki H, Fukushima M, Usami M, et al. Factors responsible for development from normal glucose tolerance to isolated postchallenge hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1211–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Committee of Japan Diabetes Society on the Diagnostic Criteria of Diabetes Mellitus . Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Jpn Diabetes Soc 2010; 53: 450–467 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta‐cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985; 28: 412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosaka K, Hagura R, Kuzuya T, et al. Insulin secretory response of diabetics during the period of improvement of glucose tolerance to normal range. Diabetologia 1974; 10: 775–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nauck MA, Meininger G, Sheng D, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, compared with the sulfonylurea, glipizide, in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin alone: a randomized, double‐blind, non‐inferiority trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2007; 9: 194–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaneko T, Baba S, Toyota T, et al. Clinical usefulness of chronic administration of AD‐4833 for non‐insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Chronic administration test for later stage of II phase. Jpn J Clin Exp Med 1997; 74: 1557–1588 (Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajaj M, Suraamornkul S, Pratipanawatr T, et al. Pioglitazone reduces hepatic fat content and augments splanchnic glucose uptake in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2003; 52: 1364–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirose H, Kawai T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Effects of pioglitazone on metabolic parameters, body fat distribution, and serum adiponectin levels in Japanese male patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 2002; 51: 314–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2427–2443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyazaki Y, Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Dose‐response effect of pioglitazone on insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavo I, Jermendy G, Varkonyi TT, et al. Effect of pioglitazone compared with metformin on glycemic control and indicators of insulin sensitivity in recently diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 1637–1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnett A, Allsworth J, Jameson K, et al. A review of the effects of antihyperglycaemic agents on body weight: the potential of incretin targeted therapies. Curr Med Res Opin 2007; 23: 1493–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Time course of fasting plasma glucose (FPG).

Figure S2 Time course of meal tolerance results in P/S group.

Figure S3 Time course of meal tolerance results in S/S group.

Table S1 Baseline patient characteristics of randomized patients.

Appendix S1 MK‐0431‐PN055 Primary Investigators listing.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item