Abstract

Numerous studies have demonstrated that females have a higher risk of experiencing several pain disorders with either greater frequency or severity than males. Although the mechanisms that underlie this sex disparity remain unclear, several studies have shown an important role for sex steroids, such as estrogen, in the modulation of nociception. Receptors for estrogen are present in primary afferent neurons in the trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia, and brief exposure to estrogen increases responses to the inflammatory mediator bradykinin (BK). However, the mechanism for estrogen-mediated enhancement of BK signaling is not fully understood. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the relative contributions of estrogen receptor α (ERα), ERβ, and G protein–coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER) to the enhanced signaling of the inflammatory mediator BK by 17β-estradiol (17β-E2) in primary sensory neurons from female rats in culture (ex vivo) and in behavioral assays of nociception in vivo. The effects of 17β-E2 on BK responses were mimicked by ERα-selective agonists and blocked by ERα-selective antagonists and by small interfering RNA knockdown of ERα. The data indicate that ERα is required for 17β-E2–mediated enhancement of BK signaling in peripheral sensory neurons in female rats.

Introduction

Many epidemiologic studies have shown that women are at an increased risk for several clinical pain disorders, and are often more sensitive to experimentally induced pain than men (for reviews, see Craft, 2007; Fillingim et al., 2009). Among the many possible reasons for the disparity in pain responsiveness between men and women, which include cognitive and sociocultural differences, several studies have shown the importance of the sex hormone estrogen in regulating nociception (Craft, 2007; Fillingim et al., 2009; Gintzler and Liu, 2012).

Estrogen effects on nociception are complex and often contradictory. In studies of experimental pain in humans, increases, decreases, and no change in pain responsiveness during the menstrual cycle or during hormone replacement therapy have been reported (Fillingim et al., 2009). The complexity in these human studies may reflect differences in the way in which the phases of the menstrual cycle were defined, differences in pain models (electrical, thermal, mechanical, etc.), the age of the women studied (pre- versus postmenopausal), and the area of the body tested. However, even in animal studies, there are many contradictory reports on the effects of estrogen on nociception (for reviews, see Craft, 2007; Gintzler and Liu, 2012). For example, when estrogen is administered to ovariectomized (OVX) rats, nocifensive behavior in response to formalin injection into the rat hind paw is reduced (Hunter et al., 2011). However, when administered to the intrathecal space of intact or OVX female rats, estrogen produced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia (Zhang et al., 2012). The nociceptive behavioral response to intra-articular injection of Freund’s complete adjuvant to the temporomandibular joint can be enhanced (Kramer and Bellinger, 2009) or reduced (Kou et al., 2011) by estrogen. It is likely that such complex and contradictory actions of estrogen on pain responsiveness reflect differential actions of estrogen on different receptor subtypes and cell populations in the pain transmission/perception pathways within the central and peripheral nervous systems, along with time-dependent effects (including genomic versus nongenomic signaling) and differences in the type of pain studied.

Of the many possible targets for estrogen within the pain neurotransmission system, studies have suggested that estrogen can alter the function of the primary sensory neurons that respond to noxious stimuli (nociceptors). Receptors for estrogen are expressed by primary sensory neurons (Papka et al., 2001; Bereiter et al., 2005; Chaban and Micevych, 2005; Dun et al., 2009; Liverman et al., 2009b), and treatment of dorsal root ganglia neurons in culture with estrogen enhances capsaicin-induced currents (Chen et al., 2004), reduces translocation of protein kinase C subtype ε (Hucho et al., 2006), and attenuates ATP-induced calcium currents (Chaban and Micevych, 2005). We have shown that estrogen treatment of sensory neurons in culture from the adult rat trigeminal ganglion enhances signaling by the inflammatory mediator bradykinin (BK) (Rowan et al., 2010). Interestingly, each of these estrogen effects in sensory neurons occurs rapidly, within minutes, suggesting a rapid-onset, nongenomic mechanism mediated by membrane-associated estrogen receptors.

The two primary receptors for estrogen, termed estrogen receptor (ER) α and ERβ, share greater than 60% sequence homology and are best known for their roles as nuclear receptors that regulate gene transcription and protein synthesis (Gibson and Saunders, 2012). ERα and ERβ are differentially expressed throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems (Perez et al., 2003) and are differentially activated by ligands in a tissue-specific manner, a characteristic exploited therapeutically by the selective estrogen receptor modulators (Hall et al., 2001; Nilsson and Koehler, 2005; Nelson et al., 2013). In addition to regulating gene transcription, both ERα and ERβ are found to be associated with the plasma membrane where they can rapidly regulate neuronal excitability (Woolley, 2007; Roepke et al., 2011; Srivastava et al., 2011) and can mediate rapid-onset, nongenomic signaling to many second messenger systems involved in nociceptive transmission, such as cAMP, calcium, and various kinases (Hammes and Levin, 2007; Levin, 2009). In addition, an estrogen-sensitive, G protein–coupled receptor, GPR30 or G protein–coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER), has recently been identified that is also capable of rapid-onset, nongenomic signaling (Barton, 2012).

We have recently found that 17β-estradiol (17β-E2) rapidly (within minutes) enhances signaling by the inflammatory mediator BK in primary sensory neurons in culture and in an animal model of nociception (Rowan et al., 2010). The effect of 17β-E2 was mimicked by a membrane-impermeable estrogen [17β-E2 conjugated with bovine serum albumin (BSA)] and not blocked by the protein translation inhibitor anisomycin, indicating mediation by a membrane-associated ER. In the present work, we evaluated the relative contributions of ERα, ERβ, and GPER to the enhanced signaling of the inflammatory mediator BK by 17β-E2 in adult female rats.

Materials and Methods

Fetal bovine serum was purchased from Gemini Bioproducts (Calabasas, CA). All other tissue culture reagents were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). (±)-1-[(3aR*,4S*,9bS*)-4-(6-Bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinolin-8-yl]-ethanone (G-1) and (3aS*,4R*,9bR*)-4-(6-bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinoline (G-15) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). 17β-E2, 1,3,5-tris(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-propyl-1H-pyrazole (PPT), 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionitrile (DPN), 1,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-[4-(2-piperidinylethoxy)phenol]-1H-pyrazole dihydrochloride (MPP), 4-(cyclohexylidenemethylene)-bis-phenol-1,1′-diacetate (cyclofenil), 17β-estradiol-6-(O-carboxymethyl)oxime–BSA (E2–BSA), and all other drugs and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Animals.

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and conformed to International Association for the Study of Pain and federal guidelines. OVX, adult female Sprague-Dawley rats, 200–250 g, were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Experiments with OVX rats were performed at least 2 weeks following surgery. Animals were housed with food and water available ad libitum before experiments.

Rat Trigeminal Ganglion Culture.

Primary cultures of rat primary sensory neurons were derived from adult OVX female rat trigeminal ganglion and prepared as described previously (Patwardhan et al., 2006; Berg et al., 2007a,b; Rowan et al., 2010). In brief, rats were killed by decapitation, and ganglia were rapidly removed and chilled in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; Ca2+, Mg2+ free) on ice. Ganglia were washed with HBSS, digested with 3 mg/ml collagenase for 30 minute at 37°C, and centrifuged. The pellet was further digested with 0.1% trypsin for 15 minutes at 37°C, pelleted by centrifugation (5000g for 5 minutes), and resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (high glucose) containing 100 ng/ml nerve growth factor (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), 10% fetal bovine serum, 1× penicillin/streptomycin, 1× l-glutamine, and the mitotic inhibitors uridine (7.5 μg/ml) and 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (17.5 mg/ml). After trituration to disrupt tissue clumps, the cell suspension was seeded on polylysine-coated 6- (mRNA), 24-, or 48-well [inositol phosphate (IP) accumulation] plates. The medium was changed 24 and 48 hours after plating and every 48 hours thereafter. Nerve growth factor and serum were removed 24 hours prior to experiments. Cells were used on the 5th or 6th day of culture.

Measurement of Inositol Phosphate Accumulation.

BK-stimulated IP accumulation in primary sensory neuronal cultures was measured as described previously (Patwardhan et al., 2006; Berg et al., 2007a; Rowan et al., 2010). Cells grown in 24- or 48-well plates were labeled with 2 μCi/ml [3H]myoinositol for 24 hours before experiments. After labeling, cells were rinsed three times with 1 ml of HBSS that contained 20 mM HEPES, and were preincubated in HBSS containing 20 mM HEPES and 20 mM LiCl for 15 minutes at 37°C in room air. Where indicated, antagonists were added 15 minutes before agonists, which were added 15 minutes before BK stimulation (1 nM, 25 minutes, 37°C). The final volume was 250 μl (48 wells) or 500 μl (24 wells). The incubation was terminated by the addition of 500 μl (48 wells) or 1 ml (24 wells) of ice-cold formic acid, and total [3H]IPs were separated with ion-exchange chromatography and measured with liquid scintillation spectrometry. Data are expressed as accumulation of total IPs (disintegrations per minute) or as a percentage of basal IP accumulation.

Small Interfering RNA.

ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool small interfering RNA (siRNA) for ERα and ERβ, siGLO Transfection Indicator, and DharmaFECT 3 transfection reagent were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). siRNA sequences for rat ERα were as follows: 5′-GAAUCAAGGUAAAUGUGUA, 5′-UCAAGUCGAUUCCGCAUGA-3′, AACCAAUGCACCAUCGAUA-3′, and 5′-GCACAAGCGUCAGAGAGAU-3′. siRNA sequences for rat ERβ were as follows: 5′-UCGCAAGUGUUAUGAAGUA-3′, 5′-GUAAACAGAGAGACACUGA-3′, 5′-AAUCAUCGCUCCUCUAUGC-3′, and 5′-GCACAAGGAGUAUCUCUGU-3′. Forty-eight hours prior to experiments, cultures were transfected with 50 nM siRNA using 1:200 DharmaFECT. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was removed and replaced with serum-free medium as in other experiments.

Behavioral Testing.

Paw withdrawal latency (PWL) to a radiant thermal stimulus was measured with a plantar test apparatus (Hargreaves et al., 1988; Rowan et al., 2009, 2010) by observers blinded to the treatment allocation. In brief, rats were placed in plastic boxes with a glass floor maintained at 30°C. After a 30-minute habituation period, the plantar surface of the hind paw was exposed to a beam of radiant heat through the glass floor. The rate of increase in temperature was adjusted so that baseline PWL values were 10 ± 2 seconds; cut-off time was 25 seconds. PWL measurements were taken in duplicate (separated by 30 seconds) at 5-minute intervals. The average of the duplicate measurements was used for statistical analysis. 17β-E2 stock solution was diluted in peanut oil. Stock solutions of all other drugs were diluted in saline with or without 2% Tween-20 as indicated. All drugs were administered via intraplantar (i.pl.) injection at a final volume of 50 µl. Where indicated, antagonists were administered 15 minutes before agonists, which were administered 15 minutes before BK injection. Doses of agonists and antagonists were chosen to produce maximal receptor occupancy based upon maximal concentrations (100 × Ki) reported in the literature (Stauffer et al., 2000; Meyers et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2002; Muthyala et al., 2003; Bologa et al., 2006; Zhao and Brinton, 2007; Dennis et al., 2009) and resulting concentrations following intraplantar injection into the paw assuming a volume of distribution of 1 ml (Rowan et al., 2010).

Data Analysis.

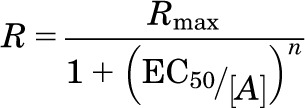

For cell culture experiments, concentration-response data were fit to a logistic equation (eq. 1) using nonlinear regression analysis to provide estimates of maximal response (Rmax), potency (EC50) and slope factor (n):

|

(1) |

where R = the measured response at a given agonist concentration (A), Rmax = maximal response, EC50 = the concentration of agonist that produces half-maximal response, and n = slope index. Statistical differences in concentration-response curve parameters between groups were analyzed with Student’s paired t test. For behavioral experiments, when only a single concentration was used, statistical significance was assessed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc or Student’s t test (paired) using Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). P values less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For behavioral experiments, time-course data were analyzed with two-way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M., and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

17β-E2 Dose-Dependently Enhanced BK Responses.

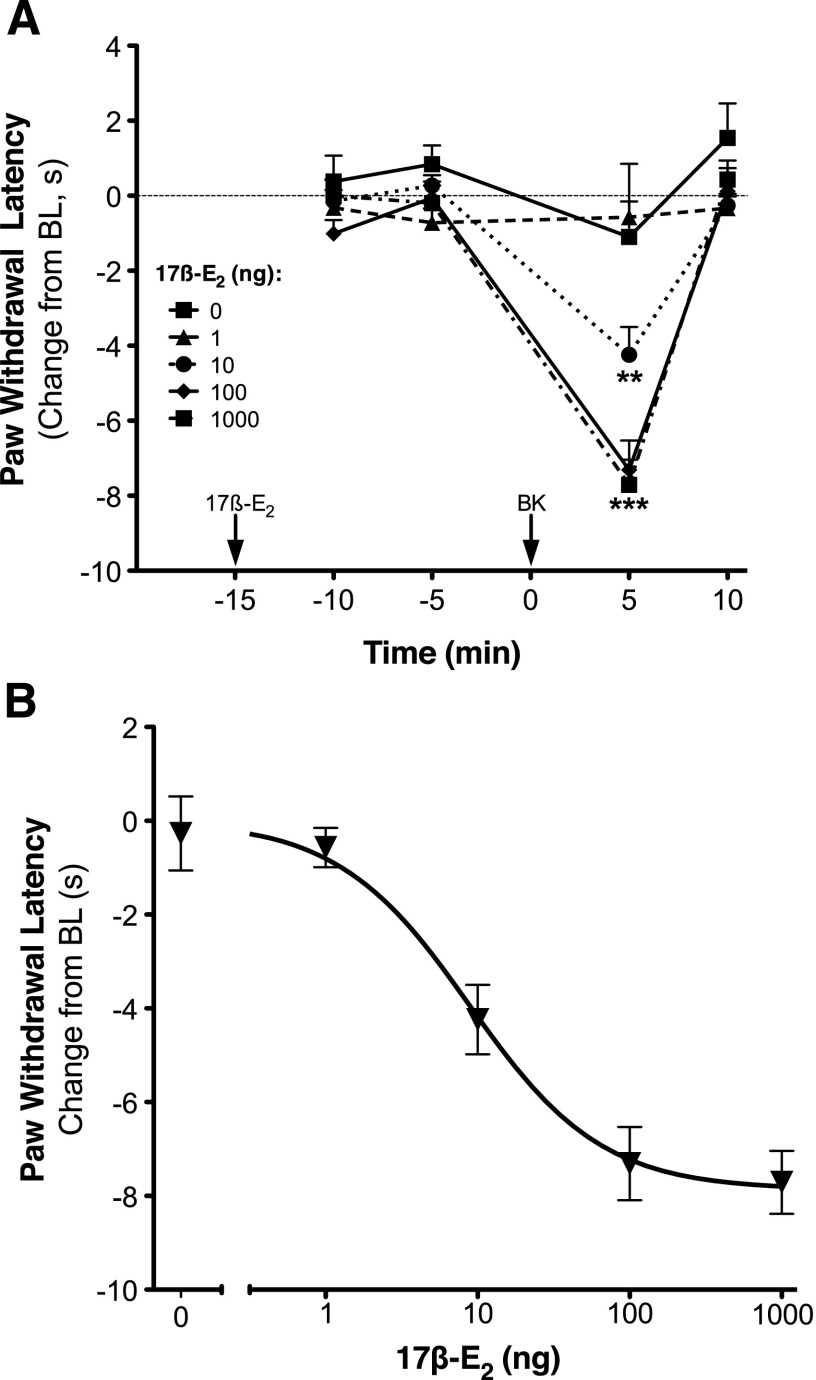

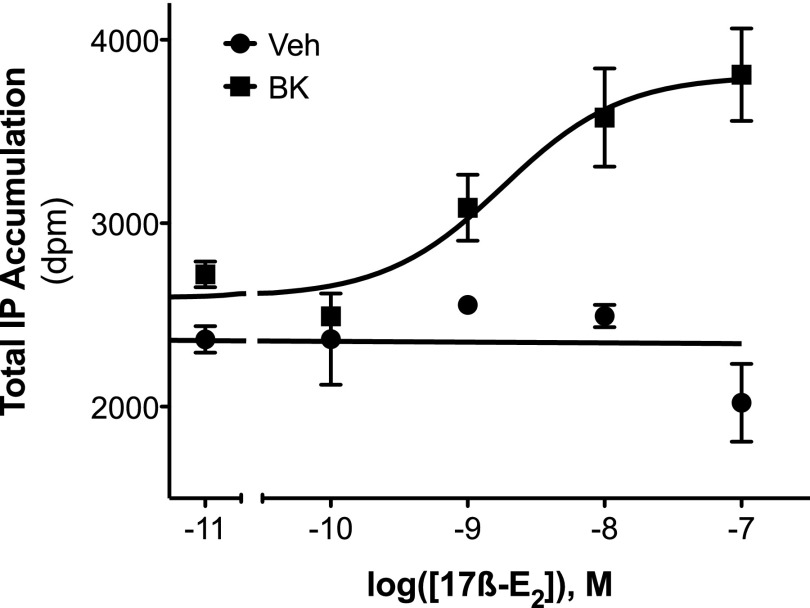

Intraplantar injection of 17β-E2 to OVX rats at doses up to 1 μg had no effect on basal PWL but dose-dependently enhanced the response of a subthreshold dose of BK (1 µg; Fig. 1, A and B). As we have shown before (Rowan et al., 2010), BK-induced thermal allodynia was rapid and transient, with peak responses occurring 5 minutes after BK injection. Peak responses were analyzed to yield an ED50 for 17β-E2 of 8.85 ng (Fig. 1B). In sensory neuronal cultures, a threshold concentration of BK (1 nM) increased IP accumulation by approximately 15% (Fig. 2). Although 17β-E2 by itself, at concentrations up to 100 nM, did not alter basal IP accumulation, pretreatment (15 minutes) of cells with 17β-E2 produced a concentration-dependent enhancement of BK-stimulated IP accumulation (Fig. 2; EC50 = 4.07 nM; Emax = 60% above basal).

Fig. 1.

Local application of 17β-E2 rapidly and dose-dependently enhances bradykinin-induced thermal allodynia in OVX rats. (A) OVX rats received intraplantar injections (50 µl) of 17β-E2 (doses indicated) or vehicle 15 minutes before injection with a subthreshold dose of BK (1 µg). PWL in response to a radiant heat stimulus applied to the ventral surface of the hind paw was measured in duplicate at 5-minute intervals before (baseline) and following each injection. Data are expressed as the change (seconds) from individual preinjection baselines (10 ± 2 seconds) and represent the mean ± S.E.M. of four to six animals per group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus vehicle by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. (B) Dose-response curve for 17β-E2 enhancement of BK-induced thermal allodynia. Data points are from (A) at the time of peak BK response (5 minutes post injection) as a function of 17β-E2 dose. ED50 = 8.85 ng. BL, baseline.

Fig. 2.

Local application of 17β-estradiol rapidly and dose-dependently enhances BK-stimulated PLC activity in cultures of peripheral sensory neurons from female rats. Peripheral sensory neuron cultures, prepared from OVX rats, were treated with vehicle [Veh; 0.1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)] or 17β-E2 (concentrations indicated) for 15 minutes (37°C) before addition of BK (1 nM) or vehicle (HBSS). Total IP accumulation after 25 minutes was measured as described under Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as the total counts (dpm) and represent the mean ± S.E.M. of three experiments.

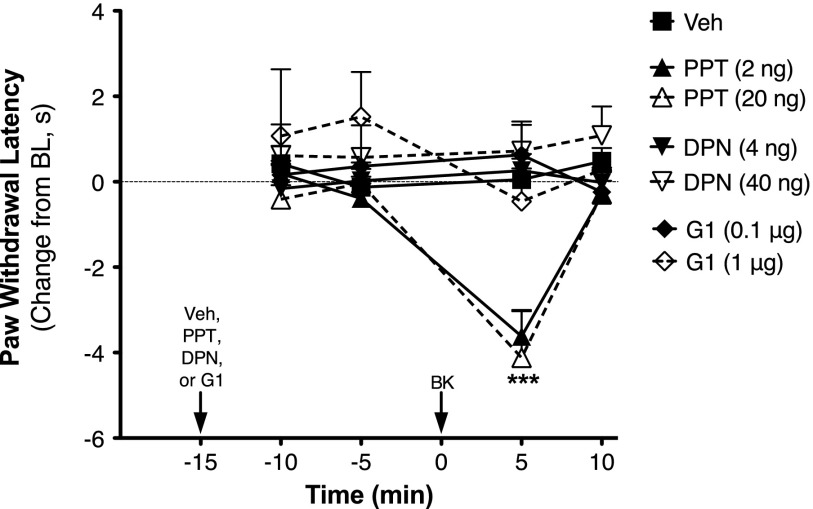

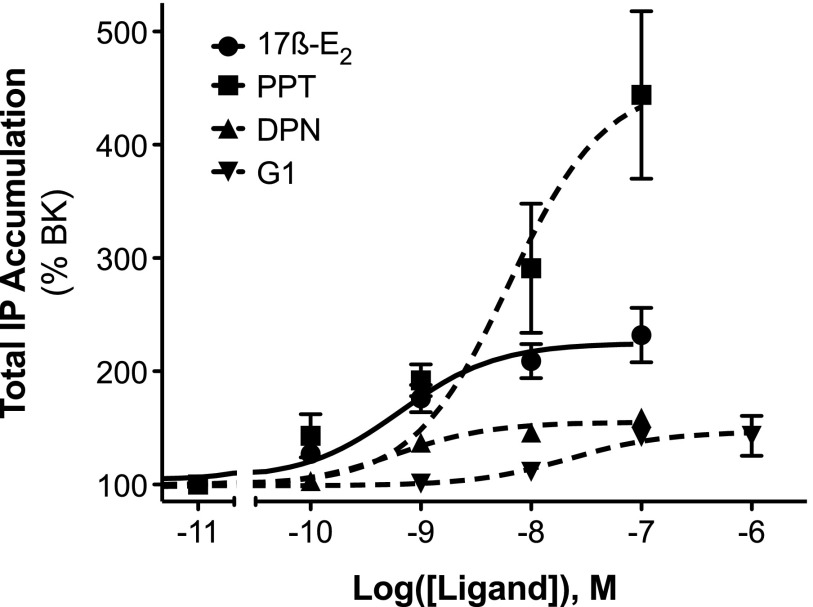

ERα Agonists Mimicked the Effect of 17β-E2 to Enhance BK Responses.

OVX rats were injected (intraplantarly) with the ER subtype-selective agonists PPT (ERα; Stauffer et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2002), DPN (ERβ; Meyers et al., 2001; Muthyala et al., 2003; Zhao and Brinton, 2007), G-1 (GPER; Bologa et al., 2006), or vehicle 15 minutes prior to injection with a subthreshold dose of BK (1 µg i.pl.). None of the agonists alone affected basal PWL; however, PPT, but not DPN or G-1, significantly enhanced the allodynic response to BK (Fig. 3). Likewise, 17β-E2, PPT, DPN, or G-1 did not alter basal phospholipase C (PLC) responses in sensory neuron cultures from OVX rats (not shown). However, 15-minute pretreatment with 17β-E2 or PPT significantly enhanced BK (1 µM)-stimulated IP accumulation by 2-fold versus 4.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

BK-induced thermal allodynia is enhanced by the ERα-selective agonist PPT but not by the ERβ-selective agonist DPN or the GPER-selective agonist G-1, in OVX rats. Separate groups of OVX animals received intraplantar injections of PPT (2 or 20 ng), DPN (4 or 40 ng), G-1 (0.1 or 1 µg), or vehicle (Veh; 0.1% DMSO, 2% Tween-20) 15 minutes before injection with a subthreshold dose of BK (1 µg). PWL was measured in duplicate at 5-minute intervals before (baseline) and after each injection. Data are expressed as the change (seconds) from individual preinjection baseline (10 ± 2 seconds) and represent the mean ± S.E.M. of four to six animals per group. ***P < 0.001 versus Veh by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. BL, baseline.

Fig. 4.

Activation of ERα enhances BK-stimulated PLC activity in female peripheral sensory neuron cultures. Peripheral sensory neuron cultures from OVX rats were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), 17β-E2, PPT, DPN, or G-1 (concentrations indicated) for 15 minutes (37°C) before addition of BK (1 nM) and further incubation for 25 minutes (37°C). Total IP accumulation was determined as described under Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as the percentage of the BK response and represent the mean ± S.E.M. of six to eight experiments. Basal IP accumulation = 310 ± 19 dpm; BK-stimulated IP accumulation = 408 ± 25 dpm (31% over basal).

ERα Antagonists Blocked the Effects of 17β-E2, PPT, and 17β-E2–BSA to Enhance BK Responses.

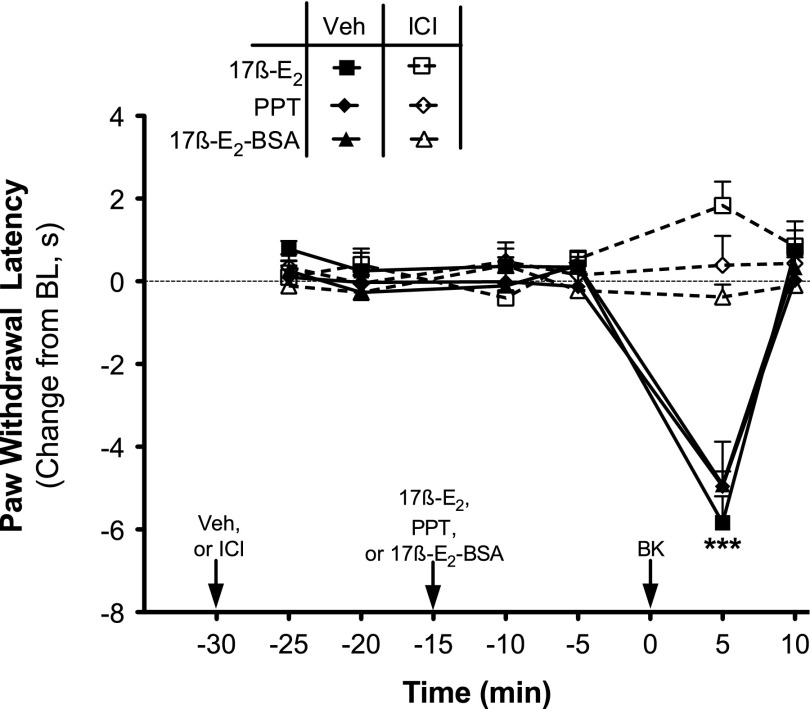

The nonselective ER antagonist ICI 182780 [(7R,8R,9S,13S,14S,17S)-13-methyl-7-[9-(4,4,5,5,5-pentafluoropentylsulfinyl)nonyl]-6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-decahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,17-diol] (1 µg i.pl.) did not affect basal PWL in OVX rats, but when injected 15 minutes prior to 17β-E2 (100 ng), PPT (2 ng), or 17β-E2–BSA (30 µg), ICI 182780 completely blocked the enhancement of BK-induced (1 µg) thermal allodynia (Fig. 5). Likewise, the ERα-selective antagonist MPP (1 µg) also blocked the 17β-E2– and 17β-E2–BSA-mediated enhancement of BK-induced thermal allodynia, without altering PWL on its own (Fig. 6). By contrast, the 17β-E2–mediated enhancement of BK-induced thermal allodynia was unaffected by the ERβ antagonist cyclofenil or the GPER antagonist G-15 at doses chosen to produce maximal receptor occupancy (100 × Ki).

Fig. 5.

17β-Estradiol, PPT, and 17β-E2–BSA enhancement of BK-induced thermal allodynia is blocked by the ER antagonist ICI 182780. Separate groups of OVX animals received intraplantar injections of the nonselective ER antagonist ICI 182780 (ICI; 1 µg) or vehicle (Veh; 0.1% EtOH) 15 minutes prior to injection with 17β-E2 (100 ng), PPT (2 ng), or 17β-E2–BSA (30 µg). Fifteen minutes later, animals received intraplantar injections of BK (1 µg). PWL was measured in duplicate at 5-minute intervals before (baseline) and after each injection. Data are expressed as the change from individual preinjection baselines and represent the mean ± S.E.M. of four to six animals per group. ***P < 0.001 respective Veh versus ICI by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. BL, baseline.

Fig. 6.

17β-E2 and 17β-E2–BSA-mediated enhancement of BK-induced thermal allodynia is blocked by the ERα antagonist MPP, but not by antagonists of ERβ, cyclofenil, or GPER, G-15. Separate groups of OVX animals received intraplantar injections of MPP (1 µg), cyclofenil (1 ng), G-15 (1 µg), or vehicle (Veh; 0.1% EtOH) 15 minutes prior to injection with 17β-E2 (100 ng) or 17β-E2–BSA (30 µg). Fifteen minutes later, animals were injected with BK (1 µg). PWL was measured in duplicate at 5-minute intervals before (baseline) and after each injection. Data are expressed as the change (seconds) from individual preinjection baselines and represent the mean ± S.E.M. of four to six animals per group. ***P < 0.001 versus all other groups by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. BL, baseline.

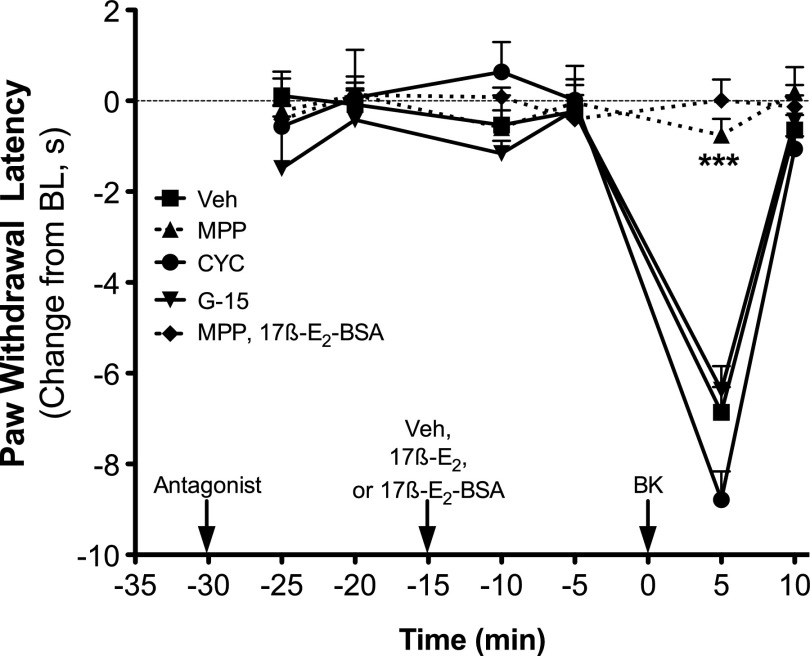

When tested in sensory neuron cultures from OVX female rats at concentrations (100 × Ki) chosen to produce maximal receptor occupancy (Stauffer et al., 2000; Meyers et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2002; Muthyala et al., 2003; Bologa et al., 2006; Zhao and Brinton, 2007; Dennis et al., 2009), only ICI 182780 (ERα and ERβ, 30 nM) and MPP (ERα, 300 nM) blocked 17β-E2 (50 nM)–mediated enhancement of BK (1 nM)-stimulated IP accumulation (Fig. 7). Cyclofenil (ERβ, 10 nM) and G-15 (GPER, 2 μM) were without effect. None of the antagonists alone altered basal IP accumulation.

Fig. 7.

17β-E2–mediated enhancement of BK-stimulated PLC signaling is blocked by the nonselective antagonist ICI 182780 and by the ERα-selective antagonist MPP but not by the ERβ- or the GPER-selective antagonists cyclofenil and G-15, respectively. Cultures of peripheral sensory neurons from OVX rats were treated with vehicle (Veh; 0.1% DMSO) or antagonist [ICI 182780 (ICI), 30 nM; MPP, 300 nM; cyclofenil (CYC), 10 nM; G-15, 2 µM] 15 minutes before treatment with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 17β-E2 (50 nM). Fifteen minutes after 17β-E2 addition, cells were treated with BK (1 nM) for 25 minutes, and total IP accumulation was determined as described under Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as a percentage of BK stimulation and represent the mean ± S.E.M. of five to six experiments. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. Basal dpm 470 ± 23.1, BK dpm 578 ± 34.4 (23% stimulation over basal).

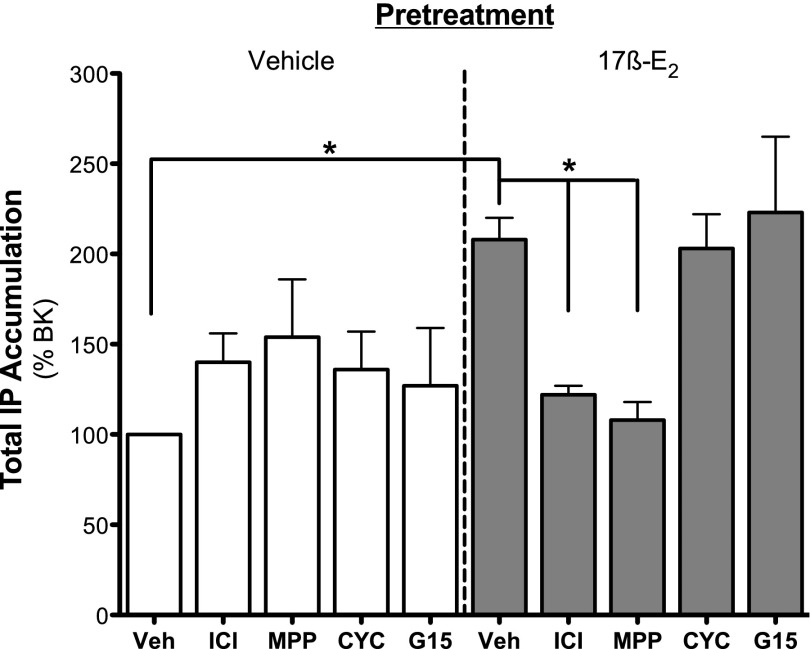

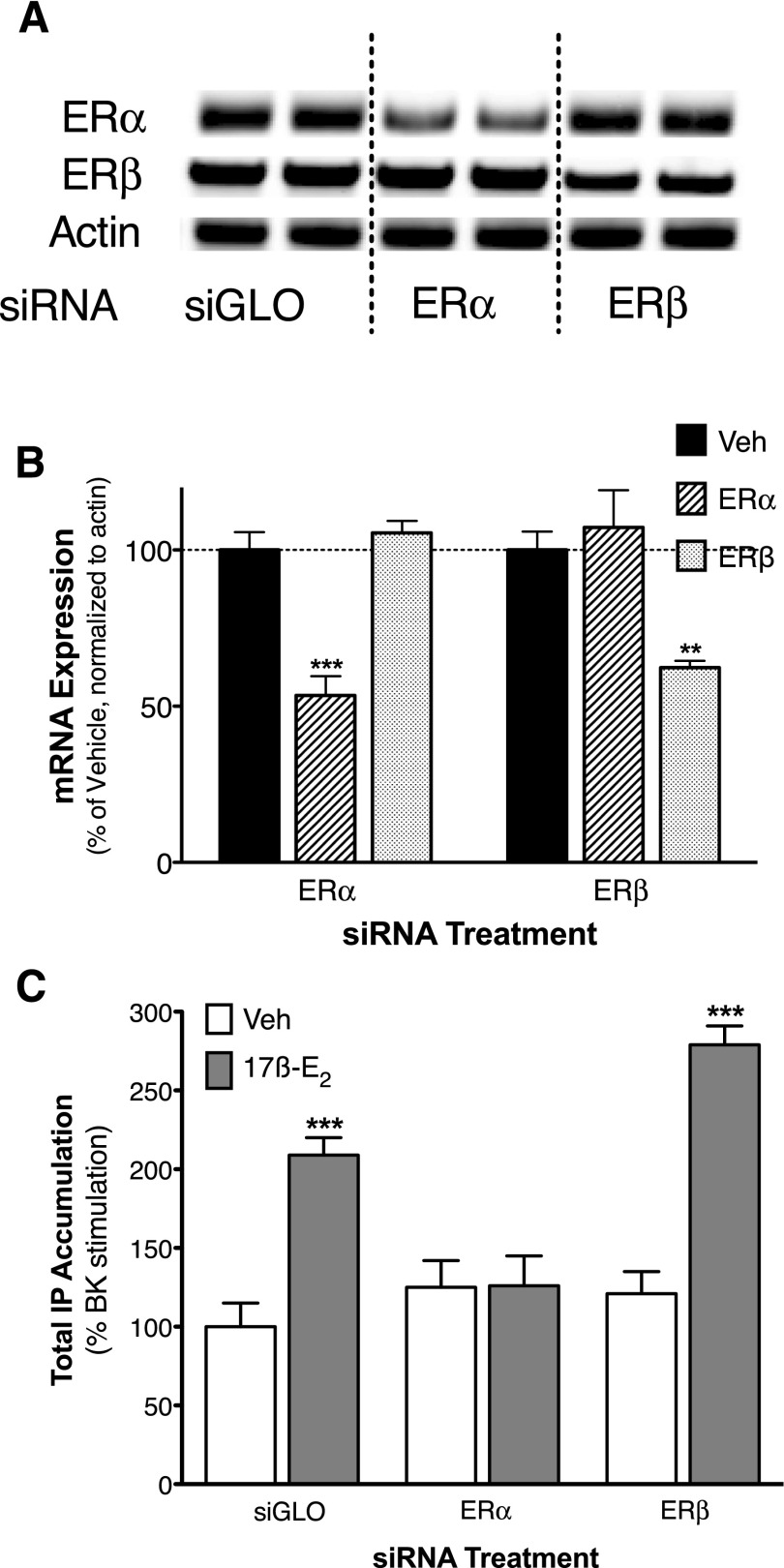

Expression of ERα Is Required for 17β-E2–Mediated Enhancement of BK Signaling.

Sensory neuron cultures were treated for 48 hours with siRNA (50 nM) selective for ERα, ERβ, or nontargeting control siRNA (siGLO). Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of total mRNA showed that treatment with siRNA for ERα or ERβ selectively reduced their respective mRNA by 47% and 38%, respectively (Fig. 8A). Treatment with ERα or ERβ siRNA did not alter threshold BK (1 nM)-stimulated IP accumulation (BK stimulation, percentage above basal: siGLO, 25 ± 4; ERα siRNA, 31 ± 5; ERβ siRNA, 30 ± 4). In cells transfected with control siRNA, 17β-E2 enhanced BK-stimulated IP accumulation as shown previously. Consistent with experiments using subtype-selective agonists and antagonists, the 17β-E2–mediated enhancement of BK-stimulated IP accumulation was blocked by siRNA directed toward ERα but not ERβ (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

ERα is required for 17β-E2–mediated enhancement of BK-stimulated PLC activity in female peripheral sensory neuron cultures. Peripheral sensory neuron cultures from OVX rats were incubated with 50 nM siRNA or siGLO control for 48 hours prior to experiments as described under Materials and Methods. Total mRNA was isolated, amplified by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction, and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis as described under Materials and Methods. (A) Representative agarose gel bands acquired using primers specific to ERα (top row), ERβ (middle row), or β-actin (bottom row) following treatment with siGLO (left two columns), ERα siRNA (middle two columns), or ERβ siRNA (right two columns). (B) Quantification of band densities normalized to β-actin. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. of three experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus vehicle (Veh) by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni. (C) Following siRNA treatment, peripheral sensory neuron cultures were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 17β-E2 (50 nM) for 15 minutes (37°C) before addition of BK (1 nM) and further incubation for 25 minutes. Total IP accumulation was determined as described under Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as a percentage of BK stimulation and represent the mean ± S.E.M. of eight experiments. ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis.

Discussion

Although ERα and ERβ share a significant amount of sequence homology, especially in the DNA-binding domain, their differential tissue expression and differential sensitivity to ligands creates an exciting area of potential therapeutic intervention for a variety of disease states. Although both ERα and ERβ have been strongly implicated in regulating nociception (Craft, 2007; Coulombe et al., 2011; Gintzler and Liu, 2012), such regulation of pain responsiveness by estrogen is complex and often contradictory. Such complexity is probably attributed to differential effects mediated by ERα and ERβ that are expressed at multiple levels of the pain neurotransmission system (Coulombe et al., 2011). Furthermore, effects of estrogen may differ depending upon the type of pain studied (Craft, 2007). Thus, to begin to clarify estrogen’s role in pain, it is important to study estrogen’s effects in defined regions of the pain-processing system.

Nociceptors respond to intense, potentially tissue-damaging stimuli and send signals to the central nervous system that are interpreted as pain, and thus are generally the first stage in the pain-processing system. Nociceptors express three receptor subtypes that respond to estrogen—ERα, ERβ, and GPER (Papka et al., 2001; Bereiter et al., 2005; Chaban and Micevych, 2005; Dun et al., 2009; Liverman et al., 2009b)—and therefore, estrogen is in a position to regulate pain neurotransmission at this initial stage. We recently found that 17β-E2 rapidly (within 15 minutes) enhances the responsiveness of nociceptors to activation by BK in vitro and in vivo (Rowan et al., 2010). The rapid-onset effect of 17β-E2 is mediated by a nongenomic mechanism via a membrane-associated receptor (Rowan et al., 2010). Here, we provide evidence that the rapid-onset effect of 17β-E2 to enhance nociceptor sensitivity to BK is mediated by the ERα receptor subtype.

17β-E2 dose-dependently enhanced BK-induced thermal allodynia in the rat hind paw in vivo and PLC activity in sensory neurons in culture, consistent with our previous report (Rowan et al., 2010). Only the ERα-selective agonist PPT mimicked the enhancement of BK responses seen with 17β-E2. The effects of 17β-E2, PPT, and the membrane impermeable 17β-E2–BSA were blocked by the ERα-selective antagonist MPP but not by the ERβ-selective antagonist cyclofenil or the GPER antagonist G-15. Neither the ERβ-selective agonist DPN nor the GPER-selective agonist G-1 enhanced BK-stimulated thermal allodynia when injected into the hind paw at doses chosen to produce maximal receptor occupancy. Collectively, these data suggest that the estrogen receptor that mediates rapid-onset enhancement of BK responses by estrogen in peripheral sensory neurons is ERα.

The utility of selective agonists and antagonists to identify receptors that mediate a response is limited by the degree of ligand selectivity for the target receptor and the dose/concentration of the ligands used. Although the affinities of the drugs used in the present study provide the highest available level of selectivity for their respective targets, there is some concern because affinity/selectivity of ER ligands has generally been characterized with the nuclear ERs that regulate gene transcription responses. The affinity of ligands for a receptor can be influenced by the molecular partners of the receptor. For example, the influence of a G protein on the binding affinity of agonists for seven transmembrane–spanning receptors is well known. Thus, it is possible that the selectivity of ligands for ERs may differ depending upon the location (membrane versus nuclear) and molecular partners of the ERs. To address this issue, and to support the pharmacological results, we used SMARTpool siRNA to selectively reduce ERα or ERβ expression in sensory neurons in culture. Treatment with siRNA selectively reduced expression of ERα or ERβ mRNA. Whereas nontargeting, control siRNA, or treatment with siRNA directed at ERβ had no effect on either the baseline BK-stimulated IP accumulation or the 17β-E2–mediated enhancement of BK responses, treatment with siRNA directed at ERα completely abolished the enhancing effect of 17β-E2 on BK-stimulated PLC activity, without affecting the baseline BK response. These results support the conclusion that the ERα subtype mediates the enhancing effect of estrogen on BK responses in peripheral sensory neurons.

In addition to ERα, ERβ and GPER are expressed in sensory neurons, and both DPN and G-1 produced small enhancements of BK-stimulated PLC activity when applied to sensory neurons in culture. The lack of the ability of DPN and G-1 to enhance BK-stimulated thermal allodynia in vivo suggests that the magnitude of the effect on BK signaling may be below the threshold needed to produce behavioral effects on thermal allodynia. Alternatively, ERβ and GPER could be expressed by sensory neurons that are not responsive to thermal stimulation but could regulate responsiveness to noxious mechanical stimulation. In addition, differences in the responses to DPN and/or G-1 between the experiments with sensory neurons of the trigeminal ganglion and the behavioral assay could reflect differences between the trigeminal versus the dorsal root ganglia sensory neurons, which mediate the paw withdrawal response to drug administration in the hind paw.

The mechanism by which activation of membrane-associated ERα rapidly enhances BK signaling in peripheral sensory neurons is not known. A large number of signaling pathways have been shown to be regulated by membrane-associated ERs in a variety of tissues, including mitogen-activated protein kinases, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activation, cAMP production, and intracellular calcium mobilization (Hammes and Levin, 2007; Levin, 2009). However, little is known about the contribution of these signaling pathways in mediating rapid effects of estrogen on nociception. In one study, rapid enhancement of inflammation-induced mechanical allodynia of the masseter muscle by estrogen was shown to be mediated by activation of extracellular signal–regulated kinase in sensory neurons (Liverman et al., 2009a). Additional experiments are needed to delineate the signaling pathway(s) regulated by membrane-associated ERα activation that mediates effects of estrogen to enhance BK-stimulated signaling in peripheral sensory neurons.

Many studies have now shown that women experience a disproportionate amount of pain, and that estrogen may be a contributory factor. Estrogen has been implicated in a variety of pain-causing conditions, including arthritis, migraine, and temporomandibular disorder. However, the effect of estrogen on pain processing is multifaceted and complex, with reports of both pro- and antinociceptive actions. Adding to the complexity are the multiple ER subtypes, genomic (long-term) and nongenomic (rapid-onset), and developmental and activational effects of estrogen. Consequently, unraveling the complexity of estrogen’s role in pain, as with many other estrogen-regulated physiologic processes, requires careful dissection of effects at multiple levels of the pain-processing system. Our results indicate that acute activation of membrane-associated ERα in peripheral sensory neurons by estrogen rapidly enhances thermal allodynia elicited by the inflammatory mediator BK. It is possible that targeting membrane–associated ERα with selective antagonists could be effective analgesics for inflammatory pain in women.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Teresa Chavera, Michelle Silva, and Victoria Espensen-Sturges for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BK

bradykinin

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DPN

2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionitrile

- 17β-E2

17β-estradiol

- E2–BSA

17β-estradiol-6-(O-carboxymethyl)oxime–bovine serum albumin

- ER

estrogen receptor

- G-1

(±)-1-[(3aR*,4S*,9bS*)-4-(6-bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinolin-8-yl]-ethanone

- G-15

(3aS*,4R*,9bR*)-4-(6-bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinoline

- GPER

G protein–coupled estrogen receptor 1

- HBSS

Hanks’ balanced salt solution

- ICI 182780

(7R,8R,9S,13S,14S,17S)-13-methyl-7-[9-(4,4,5,5,5-pentafluoropentylsulfinyl)nonyl]-6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-decahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,17-diol

- IP

inositol phosphate

- i.pl.

intraplantar

- MPP

1,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-[4-(2-piperidinylethoxy)phenol]-1H-pyrazole dihydrochloride

- OVX

ovariectomized

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PPT

1,3,5-tris(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-propyl-1H-pyrazole

- PWL

paw withdrawal latency

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Berg, Clarke, Hargreaves, Roberts, Rowan.

Conducted experiments: Berg, Rowan.

Performed data analysis: Berg, Clarke, Rowan.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Berg, Clarke, Hargreaves, Roberts, Rowan.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grants R01-NS055835, R01-NS061884, and R01-NS058655]; the Texas Advanced Research Program [Grant 003659-0023; the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Foundation; and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [Training Grant T32-DE14318] (to M.P.R.).

References

- Barton M. (2012) Position paper: The membrane estrogen receptor GPER—Clues and questions. Steroids 77:935–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereiter DA, Cioffi JL, Bereiter DF. (2005) Oestrogen receptor-immunoreactive neurons in the trigeminal sensory system of male and cycling female rats. Arch Oral Biol 50:971–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Patwardhan AM, Sanchez TA, Silva YM, Hargreaves KM, Clarke WP. (2007a) Rapid modulation of micro-opioid receptor signaling in primary sensory neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321:839–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Zardeneta G, Hargreaves KM, Clarke WP, Milam SB. (2007b) Integrins regulate opioid receptor signaling in trigeminal ganglion neurons. Neuroscience 144:889–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologa CG, Revankar CM, Young SM, Edwards BS, Arterburn JB, Kiselyov AS, Parker MA, Tkachenko SE, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, et al. (2006) Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nat Chem Biol 2:207–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaban VV, Micevych PE. (2005) Estrogen receptor-alpha mediates estradiol attenuation of ATP-induced Ca2+ signaling in mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci Res 81:31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Chang TJ, Wu FS. (2004) Competitive inhibition of the capsaicin receptor-mediated current by dehydroepiandrosterone in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 311:529–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe MA, Spooner MF, Gaumond I, Carrier JC, Marchand S. (2011) Estrogen receptors beta and alpha have specific pro- and anti-nociceptive actions. Neuroscience 184:172–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM. (2007) Modulation of pain by estrogens. Pain 132 (Suppl 1):S3–S12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MK, Burai R, Ramesh C, Petrie WK, Alcon SN, Nayak TK, Bologa CG, Leitao A, Brailoiu E, Deliu E, et al. (2009) In vivo effects of a GPR30 antagonist. Nat Chem Biol 5:421–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Brailoiu E, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER, Oprea TI, Dun NJ. (2009) Expression of estrogen receptor GPR30 in the rat spinal cord and in autonomic and sensory ganglia. J Neurosci Res 87:1610–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL., 3rd (2009) Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain 10:447–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DA, Saunders PT. (2012) Estrogen dependent signaling in reproductive tissues—a role for estrogen receptors and estrogen related receptors. Mol Cell Endocrinol 348:361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gintzler AR, Liu NJ. (2012) Importance of sex to pain and its amelioration; relevance of spinal estrogens and its membrane receptors. Front Neuroendocrinol 33:412–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JM, Couse JF, Korach KS. (2001) The multifaceted mechanisms of estradiol and estrogen receptor signaling. J Biol Chem 276:36869–36872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes SR, Levin ER. (2007) Extranuclear steroid receptors: nature and actions. Endocr Rev 28:726–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. (1988) A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain 32:77–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucho TB, Dina OA, Kuhn J, Levine JD. (2006) Estrogen controls PKCepsilon-dependent mechanical hyperalgesia through direct action on nociceptive neurons. Eur J Neurosci 24:527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DA, Barr GA, Amador N, Shivers KY, Kemen L, Kreiter CM, Jenab S, Inturrisi CE, Quinones-Jenab V. (2011) Estradiol-induced antinociceptive responses on formalin-induced nociception are independent of COX and HPA activation. Synapse 65:643–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou XX, Wu YW, Ding Y, Hao T, Bi RY, Gan YH, Ma X. (2011) 17β-estradiol aggravates temporomandibular joint inflammation through the NF-κB pathway in ovariectomized rats. Arthritis Rheum 63:1888–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer PR, Bellinger LL. (2009) The effects of cycling levels of 17beta-estradiol and progesterone on the magnitude of temporomandibular joint-induced nociception. Endocrinology 150:3680–3689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER. (2009) Plasma membrane estrogen receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab 20:477–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liverman CS, Brown JW, Sandhir R, Klein RM, McCarson K, Berman NE. (2009a) Oestrogen increases nociception through ERK activation in the trigeminal ganglion: evidence for a peripheral mechanism of allodynia. Cephalalgia 29:520–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liverman CS, Brown JW, Sandhir R, McCarson KE, Berman NE. (2009b) Role of the oestrogen receptors GPR30 and ERalpha in peripheral sensitization: relevance to trigeminal pain disorders in women. Cephalalgia 29:729–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers MJ, Sun J, Carlson KE, Marriner GA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. (2001) Estrogen receptor-beta potency-selective ligands: structure-activity relationship studies of diarylpropionitriles and their acetylene and polar analogues. J Med Chem 44:4230–4251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthyala RS, Sheng S, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. (2003) Bridged bicyclic cores containing a 1,1-diarylethylene motif are high-affinity subtype-selective ligands for the estrogen receptor. J Med Chem 46:1589–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ER, Wardell SE, McDonnell DP. (2013) The molecular mechanisms underlying the pharmacological actions of estrogens, SERMs and oxysterols: implications for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. Bone 53:42–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S, Koehler KF. (2005) Oestrogen receptors and selective oestrogen receptor modulators: molecular and cellular pharmacology. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 96:15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papka RE, Storey-Workley M, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Collins JJ, Usip S, Saunders PT, Shupnik M. (2001) Estrogen receptor-alpha and beta- immunoreactivity and mRNA in neurons of sensory and autonomic ganglia and spinal cord. Cell Tissue Res 304:193–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan AM, Diogenes A, Berg KA, Fehrenbacher JC, Clarke WP, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. (2006) PAR-2 agonists activate trigeminal nociceptors and induce functional competence in the delta opioid receptor. Pain 125:114–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez SE, Chen EY, Mufson EJ. (2003) Distribution of estrogen receptor alpha and beta immunoreactive profiles in the postnatal rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 145:117–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepke TA, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. (2011) Physiological consequences of membrane-initiated estrogen signaling in the brain. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 16:1560–1573 Landmark Ed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan MP, Berg KA, Milam SB, Jeske NA, Roberts JL, Hargreaves KM, Clarke WP. (2010) 17beta-estradiol rapidly enhances bradykinin signaling in primary sensory neurons in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335:190–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan MP, Ruparel NB, Patwardhan AM, Berg KA, Clarke WP, Hargreaves KM. (2009) Peripheral delta opioid receptors require priming for functional competence in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol 602:283–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava DP, Waters EM, Mermelstein PG, Kramár EA, Shors TJ, Liu F. (2011) Rapid estrogen signaling in the brain: implications for the fine-tuning of neuronal circuitry. J Neurosci 31:16056–16063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer SR, Coletta CJ, Tedesco R, Nishiguchi G, Carlson K, Sun J, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. (2000) Pyrazole ligands: structure-affinity/activity relationships and estrogen receptor-alpha-selective agonists. J Med Chem 43:4934–4947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Huang YR, Harrington WR, Sheng S, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. (2002) Antagonists selective for estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrinology 143:941–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. (2007) Acute effects of estrogen on neuronal physiology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47:657–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lü N, Zhao ZQ, Zhang YQ. (2012) Involvement of estrogen in rapid pain modulation in the rat spinal cord. Neurochem Res 37:2697–2705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Brinton RD. (2007) Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res 1172:48–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]