Abstract

Purpose

The effect of hospital pharmacists’ enhanced communication with patients and community providers on the underutilization of key cardiovascular medications was studied.

Methods

Patients enrolled in the Iowa Continuity of Care study were eligible for inclusion in this study if they had a diagnosis of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, coronary artery disease, or a combination of these diagnoses. Eligible patients also had to be admitted to the internal medicine, family medicine, cardiology, or orthopedics services and receive their usual medical care in the community and their prescriptions from a community pharmacy. Patients were randomized to receive minimal intervention, enhanced intervention, or usual care. For the minimal- and enhanced-intervention groups, pharmacy case managers (PCMs) performed comprehensive medication reconciliations and identified drug-related problems within 24 hours of admission. The PCMs made recommendations to the inpatient care team and to patients’ community physicians. For patients in the enhanced-intervention group, the PCM developed a discharge care plan containing the patient’s discharge medication list. PCMs made specific recommendations to optimize regimens that did not meet current guidelines or medications that were underutilized. Medication underutilization was assessed at admission, discharge, 30 days after discharge, and 90 days after discharge.

Results

A total of 732 patients were enrolled in this study. There were no significant differences among the three study groups. Overall, the rate of underutilization remained constant among all three groups, despite enhanced pharmacist involvement in both intervention groups.

Conclusion

Enhanced interventions by PCMs had no effect on the underutilization of key cardiovascular drugs during hospitalization or after hospital discharge.

Cardiovascular disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Despite the existence of effective medications to help modify disease progression and symptoms, key therapies are often underutilized.1 For example, more than 40% of patients with hypertension do not receive appropriate treatment, and over two thirds of Americans (approximately 39 million patients) with hypertension are not treated within guideline goals.2,3 Evidence-based practice guidelines are frequently implemented incompletely, resulting in suboptimal drug regimens for many patients.

Prospective payment for inpatient admissions may promote a focus on the primary admission issue, leaving other chronic medical problems unresolved. Patients are frequently discharged from the hospital without fully addressing some of their ongoing conditions.4 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act provides incentives for health care systems to create new care models that improve outcomes and minimize readmissions.5 The Joint Commission, the National Quality Forum, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have launched quality-improvement initiatives to promote multidisciplinary care models focused on reducing readmissions.6 A systematic review of 36 studies involving pharmacist-provided care to hospital inpatients found a positive impact on a number of process and outcome measures.7 However, of the 6 studies that examined readmissions, only 1 associated reduced readmissions with pharmacist interventions. The results of a recent study indicated that a pharmacy intervention did not significantly reduce medication errors or adverse drug events (ADEs).8

Although including pharmacists on inpatient care teams is now common, their role in reducing readmissions remains unclear.9,10 Many factors are beyond the control of hospital physicians or pharmacists once a patient is discharged, including suboptimal treatment by the primary care provider in the community and patient nonadherence. The recent Pharmacy Forecast 2013-2017 identified several practice model and work-force issues that directly affect the underutilization of medications.11 Two key forecasts were that health-system pharmacists would interact with providers outside the hospital and that these pharmacists would be responsible for directly managing drug therapy.

The Iowa Continuity of Care (ICOC) study was a randomized trial to determine the effects of hospital pharmacists’ enhanced communication with patients and community providers.12 A main goal of the study was to determine if better communication with community physicians and community pharmacists can reduce the underutilization of needed cardiovascular medications. Patients were enrolled in the trial through June 2012. In the ICOC study, medical records were obtained from private physicians, followed by an extensive evaluation of case abstracts and adjudication of events. The main results of the ICOC study will not be available until 2014.

During the first planned interim analyses provided to the external data and safety monitoring board meeting required by the National Institutes of Health, it was revealed that enhanced interventions by pharmacy case managers (PCMs) had no apparent effect on the primary outcome for the study, including readmissions.13 Furthermore, fewer than half of the PCMs’ recommendations were being accepted by inpatient physicians.13 These findings led us to explore whether community physicians were making changes to optimize cardiovascular therapies based on recommendations made by the PCMs. Because health systems will increasingly be financially penalized for readmissions, we felt that these findings deserved more-rapid dissemination, rather than waiting until all of the study results are known.

The objective of the current substudy was to evaluate the underutilization of cardiovascular medications during hospitalization and after discharge. We theorized that underutilization at 30 and 90 days would be reduced in the enhanced-intervention group compared with the minimal-intervention and control groups.

Methods

This study was conducted at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC), a large, tertiary care, academic medical center. The background and methods of this study have been published elsewhere.12 Other data on the acceptance of inpatient recommendations have also been published.13 The study was approved by the University of Iowa’s institutional review board for human subjects, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Briefly, the primary purpose of the ICOC study was to improve communication among the UIHC physicians and pharmacists, community physicians, and community pharmacists. A population-based approach was used so that the PCMs could oversee a large number of key inpatient services dispersed within UIHC. Therefore, the PCMs were centrally located within the cardiovascular risk service, which is within the research offices of the principal investigator in the College of Pharmacy and next door to the university hospital. One or two PCMs participated in the study at any given time, and four PCMs participated over the course of the current study. All PCMs had graduated from a doctor of pharmacy program and had completed at least one year of postgraduate pharmacy residency training accredited by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible patients spoke English or Spanish, were 18 years of age or older, and were admitted to UIHC with a diagnosis of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or diabetes or were receiving oral anticoagulation. However, when the underutilization of cardiovascular medications was analyzed, eligible patients had to have a diagnosis of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, coronary artery disease, or a combination of these diagnoses. Eligible patients also had to be admitted to the internal medicine, family medicine, cardiology, or orthopedics service and receive their usual medical care in the community and their prescriptions from a community pharmacy.

Patients were excluded from the study if they received their primary medical care from any UIHC facility with electronic medical records connected to the hospital or if they received long-term prescription medications from the UIHC outpatient pharmacies. Patients were also excluded if they did not have a working telephone, had a hearing impairment that did not allow them to use a telephone, had an estimated life expectancy of less than six months, had dementia or cognitive impairment, or had severe psychiatric or psychosocial disorders, including substance abuse, that could impair their desire or ability to complete all aspects of the study. Patients admitted to the psychiatric, surgery, or hematology/oncology service were also excluded from the study.

Patient selection and randomization

Electronic medical records were reviewed daily by the research assistant for all new patients admitted to each of the four medical services included in the study (internal medicine, family medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics). The research assistant then approached patients in their hospital room to explain the study. Once patients provided informed consent, baseline data (i.e., demographic information, their main primary care provider, and all community pharmacies used for prescriptions) were collected in a blinded fashion. Patients were then asked if they used alcohol or smoked, who managed their medications, and to rate their own health status. Medication management skills were evaluated, including the ability to read a prescription label, remove two tablets from a 7-dr prescription vial, interpret directions, and differentiate tablet colors.14

The study biostatistician created a blinded randomization scheme to stratify the medical services and minority versus nonminority patients. The randomization was developed using pseudorandom number generation via SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to ensure that the probabilities of assignment to each treatment group were equal. Patients were randomized equally to the enhanced-intervention group, minimal-intervention group, or control group.

Patients in the control group received usual care. Patients in this group did not receive medication education from the PCM but did receive a discharge medication list and oral information from a hospital unit nurse as per usual care in UIHC.

PCMs were not told whether the patient was in the minimal- or enhanced-intervention group in order to maintain blinding. PCMs performed comprehensive medication reconciliations and identified drug-related problems within 24 hours of admission by collecting information from study patients, caregivers, the electronic medical record, and community pharmacy records. The PCMs evaluated the patient’s problem list, laboratory test values, and progress notes to identify medication indications and contraindications for each medical problem. From these assessments, the PCMs made recommendations to the inpatient care team and, after discharge, to outpatient primary care physicians. These recommendations were designed to optimize therapy including addressing underutilized medications. An assessment of the pharmacotherapy regimen was prepared, and recommendations were made to inpatient physicians to promote compliance with current U.S. clinical practice guidelines and best practices. The process and outcomes of these inpatient recommendations were the subject of another substudy and are reported elsewhere.13 The PCMs met with patients every one or two days (Monday through Friday) throughout the course of the admission to provide education on medication indications, therapy goals, adverse drug effects, adherence mechanisms, and self-monitoring measures.

On the day of discharge, the PCM provided education on the patient’s discharge medications for both the minimal- and enhanced-intervention groups. The care plan addressed medication adherence issues, cost issues, anxiety about a new diagnosis, goals of therapy, plans for adjustment of the medication after discharge, and follow-up with the primary care physician. Patients in both groups also received a discharge medication list and a wallet card containing a list of all discharge medications. Next, the PCM contacted the project manager to determine the intervention group to which each patient had been assigned. Those randomized to the minimal-intervention group received no further contact or intervention from the PCM.

Enhanced intervention

For patients in the enhanced intervention group, the PCM developed a discharge care plan containing the patient’s discharge medication list including the purpose of all medications, plans for drug dosage adjustment, duration of therapy, monitoring plan, recommendations for preventing ADEs, and anticipated timing of refills, where applicable. The care plan included important points from the education provided at discharge (e.g., medication adherence issues, cost issues, anxiety about new diagnosis, goals of therapy). If the PCM identified regimens that did not meet current guidelines or medications that were underutilized, specific recommendations for optimization of treatment were noted in the care plan. The discharge care plan was then faxed to the patient’s community physician and community pharmacist.

Patients in the enhanced-intervention group also received a follow-up telephone call from the PCM three to five days after hospital discharge. The purposes of the call were to identify if the patient did not fill prescriptions for any of the discharge medications and the reasons for not filling them; evaluate any administration difficulties or problems taking discharge medications; assess the patient’s understanding of each medication; inquire about specific ADEs since discharge; reinforce patient education on each medication’s purpose, administration, and monitoring; encourage the patient to follow up with his or her community physician; and encourage communication of ADEs or poor treatment response to the patient’s community physician and community pharmacist. Any problems identified during the follow-up telephone call were communicated to the patient’s community physician.

At 90 days after discharge, the research assistant obtained detailed medical records from community physicians and all community pharmacies used by the patient to evaluate changes in cardiovascular drug utilization for patients in all three groups. Two blinded clinical pharmacists assessed medication underutilization at admission, discharge, 30 days after discharge, and 90 days after discharge. Possible medication omissions were assessed. The presence of a valid contraindication was not counted as underutilization.

Utilization of evidence-based therapies was assessed for four cardiac diagnoses: coronary artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. The definitions of standard care were determined using widely accepted practice guidelines for each condition.2,3,15,16 Standard care included aspirin, β-blockers, and statins for coronary artery disease; angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers and β-blockers for heart failure; thiazide diuretics and appropriate combination therapy if blood pressure was not controlled for hypertension; and a statin and appropriate combination therapy as needed if lipids were not controlled in hyperlipidemia.2,3,15,16

Chi-square analysis was performed to compare the three study groups for each indication of interest. The number of patients with underutilized medications was analyzed at each time point. The absence or presence of underutilization was numerically coded as 0 and 1–3 (irrespective of severity). Categorical variables were compared with chi-square test results across the three study groups to identify differences in baseline characteristics. Ordinal variables were evaluated using analysis of variance. Bonferroni corrections were made for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY). The a priori level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

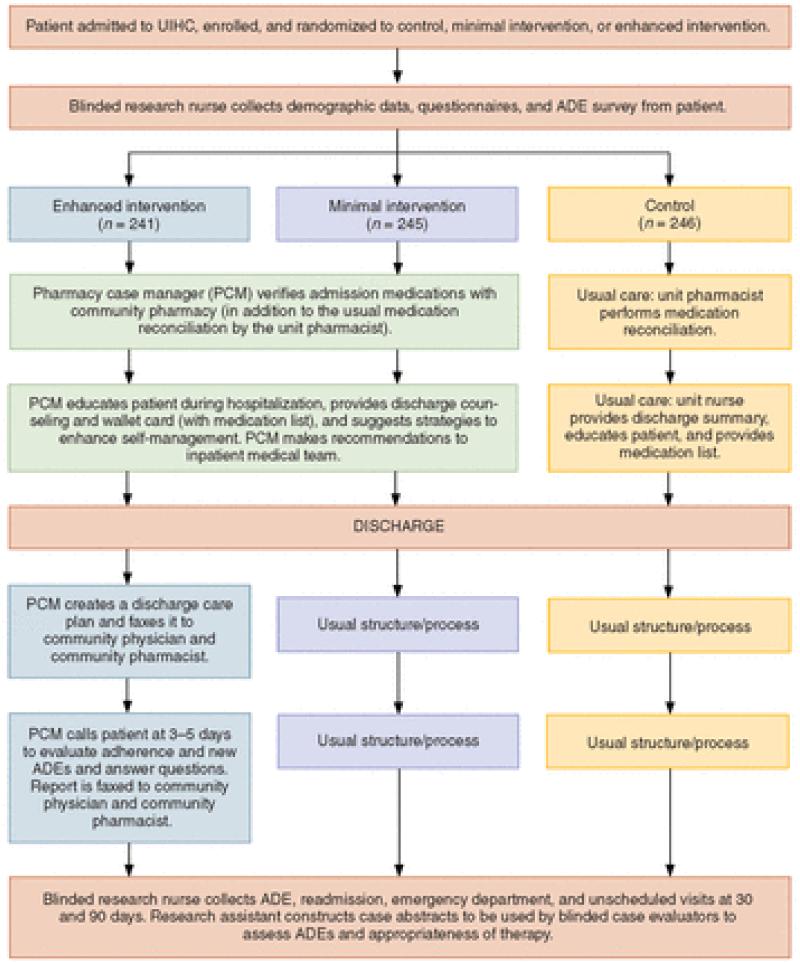

The study population for this sub-analysis included 732 patients (Figure 1). The majority were white and female and had some type of insurance coverage (Table 1). The patients had multiple chronic conditions, including hypertension (75.4%), hyperlipidemia (61.4%), coronary artery disease (33.6%), heart failure (28.3%), myocardial infarction (22.3%), and transient ischemic attack (9.9%). The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients did not significantly differ among the three study groups.

Figure 1.

Study design and patients. UIHC = University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, ADE = adverse drug event. (Adapted from Carter et al.12)

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Patientsa

| Characteristic | No. (%) Patients in Groupb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Intervention (n = 241) |

Minimal Intervention (n = 245) |

Control (n = 246) |

|

| Female | 128 (53.1) | 133 (54.3) | 113 (45.9) |

| Married/partnered | 149 (62.3)c | 165 (67.6)d | 159 (64.6) |

| Prescription coverage | 227 (99.1)c | 230 (94.7)c | 236 (96.7)c |

| Annual income | |||

| <$24,999 | 77 (33.9) | 84 (38.5) | 86 (38.6) |

| $25,000–$54,999 | 93 (41.0) | 74 (33.9) | 69 (30.9) |

| $55,000–$99,999 | 42 (18.5) | 43 (19.7) | 48 (21.5) |

| ≥$100,000 | 15 (6.6) | 17 (7.8) | 20 (9.0) |

| Missing/refused | 14 | 27 | 23 |

| Race | |||

| White | 220 (92.1) | 223 (91.0) | 224 (91.4) |

| Black | 9 (3.8) | 13 (5.3) | 12 (4.9) |

| Hispanic | 5 (2.1) | 5 (2.0) | 5 (2.0) |

| Other | 4 (1.7) | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.2) |

| Missing/refused | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Education level | |||

| Grade 8 or less | 12 (5.0) | 14 (5.7) | 19 (7.8) |

| High school diploma | 107 (44.8) | 124 (50.6) | 119 (48.6) |

| College degree (2–4 yr) |

91 (38.1) | 85 (34.7) | 86 (35.1) |

| Graduate degree | 29 (12.1) | 22 (9.0) | 21 (8.6) |

| Missing/refused | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoked | 102 (42.7) | 111 (45.5) | 94 (38.4) |

| Ex-smoker | 115 (48.1) | 107 (43.9) | 126 (51.4) |

| Current smoker | 22 (9.2) | 26 (10.7) | 25 (10.2) |

| Missing/refused | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Self-rated health status | |||

| Excellent | 9 (3.8) | 10 (4.1) | 14 (5.7) |

| Very good | 43 (18.0) | 34 (13.9) | 33 (13.5) |

| Good | 80 (33.5) | 84 (34.3) | 100 (41.0) |

| Fair | 76 (31.8) | 78 (31.8) | 63 (25.8) |

| Poor | 31 (13.0) | 39 (15.9) | 34 (13.9) |

| Missing/refused | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Prescription management | |||

| Patient only | 208 (88.5) | 210 (86.1) | 219 (91.3) |

| Patient and caregiver | 23 (9.8) | 29 (11.9) | 18 (7.5) |

| Caregiver only | 4 (1.7) | 5 (2.0) | 3 (1.3) |

| Missing/refused | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| Patient able to | |||

| Read prescription label | 229 (98.2) | 240 (98.7) | 234 (98.3) |

| Open prescription vial | 227 (99.1) | 234 (98.3) | 231 (97.9) |

| Remove 2 tablets | 205 (89.5) | 218 (92.4) | 211 (89.8) |

| Interpret instructions | 207 (88.5) | 217 (88.9) | 215 (89.6) |

| Differentiate colors | 170 (72.6) | 186 (76.5) | 181 (75.4) |

| Alcohol use | |||

| None | 153 (64.0) | 148 (60.7) | 147 (60.2) |

| <1 drink/day | 66 (27.6) | 75 (30.7) | 75 (30.7) |

| 1–2 drinks/day | 16 (6.7) | 16 (6.6) | 19 (7.8) |

| ≥3 drinks/day | 4 (1.7) | 5 (2.0) | 3 (1.2) |

| Missing/refused | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Hypertension | 192 (80.0) | 178 (72.7) | 184 (75.4) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 149 (62.1) | 154 (62.9) | 148 (60.7) |

| Coronary artery disease |

90 (37.5) | 81 (33.1) | 76 (31.1) |

| Heart failure | 65 (27.1) | 77 (31.4) | 66 (27.0) |

| Myocardial infarction | 58 (24.2) | 55 (22.4) | 51 (20.9) |

| Transient ischemic attack |

24 (10.0) | 26 (10.6) | 23 (9.5) |

Mean ± S.D. age of patients was 61.3 ± 12.7 years in the enhanced-intervention group, 59.4 ± 12.7 years in the minimal-intervention group, and 60.6 ± 12.4 years in the control group.

There were no statistically significant differences between the three groups.

Data missing for 2 patients.

Data missing for 1 patient.

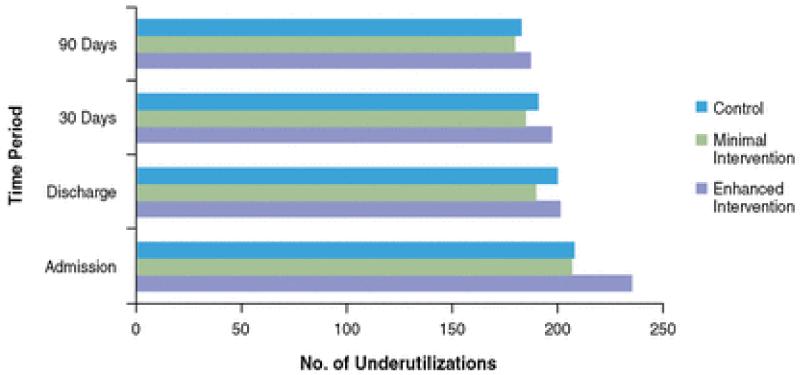

Figure 2 displays the overall number of underutilized therapies for all patients in the three study groups. There were no significant differences among the three groups despite modest reductions in underutilization in all three groups over time (Table 2). Since there were no significant differences between the study groups, the data were combined to display the rates of underutilization for each drug class (Table 3). Overall, the rate of underutilization remained constant among all three groups despite enhanced pharmacist involvement in both intervention groups.

Figure 2.

Overall number of underutilizations within each study group at each time point.

Table 2.

Characterization of Cardiovascular Drug Underutilization in Study Groupsa

| Enhanced Intervention | Minimal Intervention | Control | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period |

No. Pts | %b | No Underutilized Drugs per Pt |

No. Pts | %b | No Underutilized Drugs per Pt |

No. Pts | %b | No Underutilized Drugs per Pt |

| Admission | 70 | 66.7 | 1.49 | 61 | 55.5 | 1.22 | 64 | 58.2 | 1.18 |

| Discharge | 67 | 65.7 | 1.25 | 60 | 55.0 | 1.06 | 62 | 56.4 | 0.99 |

| 30 days | 66 | 65.3 | 1.19 | 56 | 52.8 | 1.05 | 60 | 56.1 | 1.02 |

| 90 days | 61 | 62.2 | 1.11 | 53 | 50.5 | 1.00 | 56 | 54.4 | 1.02 |

None of the differences between groups were statistically significant.

Number of patients in whom underutilization was reported in at least one of nine evaluated condition-drug combinations/total patients evaluated with drug indication.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Patients With Underutilized Drugs in All Groups Combineda

| No. (%) Pts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Admission | Discharge | 30 Days | 90 Days |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||

| Aspirin | 32 (23.7) | 21 (15.6) | 25 (19.2) | 20 (15.9) |

| Beta-blocker | 33 (24.6) | 24 (17.9) | 22 (16.9) | 21 (16.7) |

| Statin | 32 (24.2) | 21 (16.1) | 20 (15.8) | 17 (13.8) |

| Heart failure | ||||

| ACEI or ARB | 35 (29.4) | 34 (29.1) | 27 (23.9) | 28 (25.9) |

| Beta-blocker | 32 (27.4) | 22 (18.8) | 24 (21.2) | 22 (20.4) |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Thiazide diuretic | 95 (36.2) | 99 (37.6) | 98 (38.4) | 92 (36.8) |

| Combination therapy | 65 (28.4) | 48 (20.3) | 44 (19.1) | 45 (17.6) |

| Hyperlipidemia | ||||

| Statin | 54 (26.1) | 42 (20.4) | 38 (18.9) | 34 (17.4) |

| Combination therapy | 44 (27.7) | 41 (25.6) | 42 (25.9) | 40 (25.2) |

No statistically significant differences between groups.

ACEIs = angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, ARBs = angiotensin-receptor blockers.

Discussion

The results of this study revealed a high rate of underutilization of cardiovascular drugs among inpatients at UIHC and that a pharmacist-based intervention had no significant influence on reducing this problem. This study was unique in that we collected data from external hospitals, private physicians, and community pharmacies. A strength of this study was the use of blinded pharmacist evaluators who determined if a given patient should have received the medications prescribed.

We previously demonstrated that inpatient physicians often did not change therapy for chronic conditions after receiving recommendations to do so from PCMs.13 However, our enhanced intervention did not appear to reduce suboptimal therapy after discharge. It is not known why these community physicians did not change therapy, since we previously found that community physicians accepted about 50% of the recommendations faxed by community pharmacists.17,18

Hospitalization provides an opportunity to evaluate and optimize therapy for patients with chronic diseases. However, we did not find a reduction in underutilization before discharge. Once discharged, it should not be assumed that the underutilization of medications will be appropriately addressed. One study found that inpatient physicians at a large, academic teaching hospital recommended only 28% of discharged patients for outpatient follow-up; over one third of the recommended follow-up visits were not completed.4 If adjustments are not made during the inpatient stay, the primary care physician might interpret this as approval by specialists at the hospital of his or her patient care plan. This may partially explain the findings of our current study, even though the PCM faxed an updated care plan for patients in the enhanced-intervention group. We believe that these issues should ideally be addressed during hospitalization because they represent missed opportunities to intervene and improve chronic disease management.

A recent study evaluated medication errors and ADEs following a pharmacist intervention for 30 days after hospital discharge in 851 patients.8 In that study, 432 (50.8%) had one or more clinically important medication errors; 22.9% of such errors were judged to be serious and 1.8% life-threatening. Actual and potential ADEs occurred in 30.3% and 29.7%, respectively. The pharmacist intervention did not significantly reduce medication errors (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77–1.10) or ADEs (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.86–1.39), but there was a trend for fewer potential ADEs (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.61–1.04).

Pharmacists practicing in intensive care have been shown to reduce ADEs.19 Preventable ADEs were decreased in one study by 66% (p < 0.001) when a pharmacist was added to the care team.19 Physicians accepted 362 (99%) of the 366 recommendations made by the pharmacist.

Curry et al.20 evaluated Medicare data from 11 U.S. hospitals ranking in the top or bottom 5% for mortality rates after acute myocardial infarction. Pharmacists in high-performing hospitals were described as being “closely integrated into care processes” and having “influenced clinical decisions.” In low-performing hospitals, pharmacist roles were described as being “narrowly circumscribed” and having “limited participation in clinical decisions.”

Our study had several limitations. The study was not preplanned, and an a priori power analysis and sample-size calculation were not performed. However, the means and percentages among groups were so similar that it is unlikely that differences would have been detected, even if there were several thousand patients in each group. The study was purposefully designed to add PCMs to usual pharmacy services in this hospital, in part because there were only two decentralized pharmacists on all nine medical services. In addition, at any given time, only one or two PCMs were involved with this study, so it was not possible for PCMs to assess patients in all of the critical services. Because this study deployed them across nine inpatient services, PCMs did not function as part of the inpatient medical team. Instead, they centrally covered these services and made therapy recommendations based on a comprehensive review of each study patient’s medical case. The inpatient physicians may have been reluctant to accept recommendations from a pharmacist working outside of the medical team without previously established trust and rapport. However, the PCMs were frequently in the hospital, visiting study patients usually every one to two days. Data were collected by reviewing medical records and from self-report. Events may have been missed if they were not documented in the records reviewed or the patient did not report them during follow-up telephone calls. Another limitation is that the community physicians did not know the PCMs personally and may have been reluctant to accept recommendations in the care plans. Based on the recent experience of one of the study investigators in a private hospital working with private physicians, physicians’ staff often screen information such as faxes to minimize workload. It might be possible that many of the care plans were not seen by the physician. Even so, a 50% acceptance rate has been observed in other studies in which recommendations were faxed to physicians.17,18 Finally, we used specific guidelines from the United States for each condition. Guidelines from other countries and other organizations may recommend different therapies than the guidelines we used.

We felt that health-system pharmacists should be made aware of these findings before the completion of the ICOC study in order to plan interventions that may be more likely to improve care and reduce suboptimal therapy. Such approaches will be critical in order to minimize rehospitalizations, which will financially penalize hospitals.

The Pharmacy Forecast 2013-2017 surveyed 150 panel members, and several questions they addressed have direct relevance to suboptimal use of medications.11 Seventy-two percent of respondents believed that it was very likely or somewhat likely that health-system pharmacists will interact with health professionals outside the hospital to ensure continuity of care, and 62% believed that inpatients would be managed by pharmacists who would initiate and modify drug therapy.

Similar interventions should be structured with consideration given to the many challenges and limitations faced by physicians in tertiary care. Perhaps recommendations for long-term drug therapy should be made to the community physician. However, this intervention will need to be structured so that more-intense recommendations and follow-through can be achieved to minimize underutilized medications. Communication to the community physicians should come from a PCM who is easily identified as a member of the team of providers caring for the patient during the hospitalization. The type of communication needs to be structured so that the urgency of the recommendation is clear and addressed by the physician.

Future studies and health-system reorganization should identify efficient strategies to improve the long-term care of hospitalized patients with chronic diseases after discharge. These interventions should include the development of a care structure. The role of pharmacists in hospital settings and to improve continuity of care with community providers should be addressed to reduce the cases of underutilization of important medications.

Conclusion

Enhanced interventions by PCMs had no effect on the underutilization of key cardiovascular drugs during hospitalization or after hospital discharge.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by grant 1RO1 HL082711 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Funding also provided to Dr. Carter by grant REA 09-220 from the Center for Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors have declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Emily N. Israel, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor.

T. Michael Farley, Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science, College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Karen B. Farris, Social and Administrative Sciences (Pharmacy) Graduate Program, College of Pharmacy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Barry L. Carter, Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science, College of Pharmacy, and Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa.

References

- 1.Stafford RS, Radley DC. The underutilization of cardiac medications of proven benefit, 1990 to 2002. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:56–61. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong KL, Cheung BM, Man YB, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999-2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosecoff J, Kahn KL, Rogers WH, et al. Prospective payment system and impairment at discharge. The ‘quicker-and-sicker’ story revisited. JAMA. 1990;264:1980–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond CA, Raehl CL. Clinical pharmacy services, pharmacy staffing, and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:481–93. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, et al. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:955–64. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kripalani S, Roumie CL, Dalal AK, et al. Effect of a pharmacist intervention on clinically important medication errors after hospital discharge: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:1–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565–71. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lisby M, Thomsen A, Nielsen LP, et al. The effect of systematic medication review in elderly patients admitted to an acute ward of internal medicine. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;106:422–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zellmer WA, Walling RS. Pharmacy Forecast 2013-2017: strategic planning advice for pharmacy departments in hospitals and health systems. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2012;69:2083–7. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter BL, Farris KB, Abramowitz PW, et al. The Iowa Continuity of Care study: background and methods. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65:1631–42. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderegg SV, Demik DE, Carter BL, et al. Acceptance of recommendations by inpatient pharmacy case managers: unintended consequences of hospitalist and specialist care. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33:11–21. doi: 10.1002/phar.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruscin JM, Semla TP. Assessment of medication management skills in older outpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30:1083–8. doi: 10.1177/106002809603001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith SC, Jr., Allen J, Blair SN, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006;113:2363–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JJ, Kelly P, Carter BL, et al. Comprehensive pharmaceutical care in the chain (pharmacy) setting. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1996;36:443–51. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chrischilles EA, Carter BL, Lund BC, et al. Evaluation of the Iowa Medicaid pharmaceutical case management program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:337–49. doi: 10.1331/154434504323063977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 1999;282:267–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]