Abstract

This paper describes the initial evaluation of the Therapist-Parent Interaction Coding System (TPICS), a measure of in vivo therapist coaching for the evidence-based behavioral parent training intervention, parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT). Sixty-one video-recorded treatment sessions were coded with the TPICS to investigate (1) the variety of coaching techniques PCIT therapists use in the early stage of treatment, (2) whether parent skill-level guides a therapist’s coaching style and frequency, and (3) whether coaching mediates changes in parents’ skill levels from one session to the next. Results found that the TPICS captured a range of coaching techniques, and that parent skill-level prior to coaching did relate to therapists’ use of in vivo feedback. Therapists’ responsive coaching (e.g., praise to parents) was a partial mediator of change in parenting behavior from one session to the next for specific child-centered parenting skills; whereas directive coaching (e.g., modeling) did not relate to change. The TPICS demonstrates promise as a measure of coaching during PCIT with good reliability scores and initial evidence of construct validity.

Keywords: parent-child interaction therapy, PCIT, behavioral parent training, child conduct problems, mediators of change, in vivo coaching, assessment-guided treatment

Behavioral parent training (BPT) has been identified as the best practice for the treatment of young children with conduct problems (Brestan & Eyberg, 1998; Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008). BPT teaches parents effective strategies to change children’s behaviors, such as positive reinforcement, selective attention, and consistent discipline. However, limited knowledge exists about which mechanisms most effectively change parents’ behaviors to maximize the improvement in children’s behavior (Weersing & Weisz, 2002). Simply teaching parenting skills via lecture or didactic has not proved adequate to promote behavior changes in parents (Eddy, Dishion, & Stoolmiller, 1998; Nix, Bierman, & McMahon, 2009). In fact, directive teaching (e.g., teaching new skills or confronting parents) can lead to resistance in treatment (Patterson & Forgatch, 1985). More complex strategies appear to be related to parents’ behavior change. Understanding these mechanisms of change may be the most important investment in research to improve clinical training and treatment implementation in the future (Kazdin & Nock, 2003;Weersing & Weisz, 2002).

One proposed mechanism of change in BPT is therapist in vivo feedback to parents during parent-child interactions, often referred to as “coaching” (Shanley & Niec, 2010). Coaching is specific, immediate feedback that a therapist provides while a parent practices new skills with his/her child. This type of feedback allows the therapist to quickly respond to a parent’s behaviors while they are happening, which reinforces positive parenting behaviors or immediately corrects mistakes (Herschell, Calzada, Eyberg, & McNeil, 2002). For example, if a parent gives their child a specific and labeled praise for sharing, then a coach would reinforce this parent by saying, “That was a great labeled praise.” Whereas, if a parent gave a vague, unlabeled praise the interaction might look as follows:

Parent: “Thank you.”

Therapist: “Thank you for…”

Parent: “Thank you for sharing with me.”

Therapist: “Great labeled praise. Now he knows what it is you like.”

A recent meta-analysis of BPT programs revealed that programs that include coaching have a greater effect size than programs without it (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle, 2008). Although coaching can lead to important parent outcomes, limited research explains what types of coaching are effective (Herschell, Capage, Bahl, & McNeil, 2008; Shanley & Niec, 2010). A valid and reliable behavioral observation measure of the therapist-parent interactions that occur during coaching is necessary to begin to address this goal (Snyder et al., 2006).

PCIT is a BPT with a robust evidence-base, which uses coaching as a primary mechanism to change parent behaviors (Herschell et al., 2002). PCIT is similar to some other effective BPT programs in that it is based on a two-stage model of treatment (e.g., Barkley, 1987; Forehand & McMahon, 1981), where the first stage, Child-Directed Interaction (CDI), teaches parents child-centered interaction skills and non-confrontational behavior management skills, while the second stage, Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI), teaches parents to implement effective and consistent discipline strategies (Kaminski et al., 2008). However, PCIT includes innovative features that distinguish it from many BPT programs: It is an assessment-driven intervention that uses coaching to shape parents’ acquisition of skills in session (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011; Niec, Gering, & Abbenante, 2011).

During the first phase of PCIT, parents are taught to increase their positive interactions with their children, using skills such as reflections, child-focused descriptions, and genuine, specific praises. These skills are sometimes referred to as the “Do” skills (i.e., reflections, behavior descriptions, and labeled praises), because they are behaviors parents are encouraged to increase. During the CDI phase, parents are also taught to decrease their use of questions, commands, and criticisms in order to avoid negative interactions and to keep their child in the lead of the play situation. These behaviors are sometimes referred to as “Don’t” behaviors (Bell & Eyberg, 2002; Niec et al., 2011). When parents enter the second phase of PCIT, they learn consistent discipline techniques for noncompliance and misbehavior (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011). Coaching during the first and second phases of PCIT differs markedly. Because the first phase, CDI coaching, is the focus of this study, we do not describe the PDI phase in depth. For more extensive descriptions of the two phases of PCIT, please see McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010 or Niec et al., 2011.

Both phases of PCIT have a similar structure. Parents are initially taught the targeted parenting skills in a didactic session during which therapists teach parents through interactive techniques such as modeling and role-playing. Subsequent to the didactic session, parents and children attend coaching sessions together. Coaching sessions are structured to include (1) a brief discussion with the therapist about progress and goals, (2) a standardized, five-minute behavior observation of the parent-child interaction, and (3) coaching, during which parents practice the child-centered skills in a play situation with their children while the therapist provides feedback from an observation room through a microphone and bug-in-the-ear receiver.

During the parent-child behavior observation prior to coaching, the therapist assesses the parent’s use of the “Do” and “Don’t” skills (see Table 1 for examples). The assessment is meant to guide the therapist’s coaching, allowing more focus to be given to a parent’s weaker skills (Bahl, Spaulding, & McNeil, 1999). After the assessment, therapists spend the majority of the treatment session coaching the parent. The immediate feedback and social reinforcement provided through coaching is meant to facilitate skill development with general parenting skills (e.g., selective attention) along with the specific “Do” skills (Borrego & Urquiza, 1998; Eyberg & Matarazzo, 1980).

Table 1.

DPICS-III Categories of Parent Behaviors (Eyberg, Nelson, Duke, & Boggs, 2005)

| Behavioral Code | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior Descriptions | A declarative sentence where a parent states what a child is doing or recently did. | “You’re building a tower.” |

| Unlabeled Praises | A nonspecific verbal statement of approval of an attribute, behavior, or product of the child. | “Thank you” “Good work” |

| Labeled Praises | A specific verbal statement of approval of an attribute, behavior, or product of the child. | “Thank you for cleaning up.” |

| Reflection | A statement where a parent repeats or reflects back what the child said. | Child: “It’s fast.” Parent: “It’s fast.” |

| Negative Talk | A statement that criticizes a child’s activity, behavior, or verbalizations. | “That’s the wrong way.” |

| Question | A descriptive or reflective comment expressed in the form of a question. | “What does a cow say?” |

| Direct Commands | A declarative sentence that requests that a child perform a specific activity or behavior. | “Please hand me that red block.” |

| Indirect Commands | A sentence which requests a child do a behavior stated in a question form. | “Can you hand me that block?” |

Therapists use a variety of different techniques during coaching; including directive and responsive techniques (Borrego & Urquiza, 1998; see Table 2 for examples). Directive techniques explicitly tell the parent what to do or say (e.g., “Tell Johnny, ‘Great job building that tower.’ ”); whereas responsive techniques reinforce the parent’s use of a skill (e.g., “You just used an excellent praise”). Directive techniques, such as modeling a skill for a parent, are considered valuable when a parent is first learning the skills and rarely uses them spontaneously; whereas, responsive techniques may be used at any time to reinforce a parent’s existing skills. PCIT researchers and clinicians recommend that responsive techniques should be used frequently as a way to shape behavior when parents approximate a correct skill, because the social reinforcement (i.e., therapist’s praise) will lead to efficient behavior change (Borrego & Urqiuza, 1998; McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010). However, these recommendations are based on theory and have limited empirical support. To date, only one study has examined the impact of coaching style on parents’ skill acquisition. Findings suggest that parents acquire skills at a higher rate when coaching includes more constructive advice (e.g., “Be careful with those commands”) than positive feedback (e.g., “Great job praising him;” Herschell et al., 2008).

Table 2.

TPICS Categories

| Behavioral Code | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Directive Coaching | ||

| Model | A therapist delivered statement that the parent is intended to repeat. | “Thank you for sharing.” |

| Prompt | A stem line that ends with the therapist trailing off so the parent completes the skill. | “ Thank you for…” |

| Command | A statement that tells or suggests to the parent what to say or do. | “Tell her what you like about her behavior.” |

| Drills | An exercise that sets a specific skill goal or time to focus on a skill. | “Let’s see how many praises you can do in one minute.” |

| Responsive Coaching | ||

| Labeled Praises | A specific positive statement about a parent’s behavior. | “That was a great behavior description!” |

| Process Comments | A statement that ties the child’s behaviors to the parent’s behaviors | “She smiled when you praised her!” |

| Reflective Descriptions | A statement that informs a parent what skill they used. | “That was a behavior description.” |

| Corrective Criticism | A correction of a parent’s behavior. | “Whoops, that was a question.” |

| Unlabeled Praises | A nonspecific praise of the parent. | “Great!” |

Because there is a dearth of literature investigating PCIT coaching specifically, we examined the literature on behavior change in therapy more generally to determine which coaching techniques might be most likely to influence parents’ skill acquisition. The findings in the broader literature remain mixed. For example, in a study that examined counselors’ acquisition of therapy skills rather than parents’ skill acquisition, modeling was the only effective feedback strategy to change behaviors when compared with criticism and praise (Gulanick & Schmeck, 1977). Alternatively, research examining how therapist behaviors impact client outcomes, suggests that supportive and reinforcing therapist behaviors facilitate behavior change in clients, whereas directive behaviors lead to resistance (Hill et al., 1988; Patterson & Forgatch, 1985). During parent training sessions, parents were more likely to respond with resistance after a therapist made efforts to teach or confront them, whereas there was reduced parent noncompliance after the therapist provided support (Patterson & Forgatch, 1985). Furthermore, clients receiving cognitive-behavioral treatment were more likely to respond with resistance after directive, teaching statements by the therapist (Watson & McMullen, 2005). Finally, it has been suggested that a combination of modeling and social reinforcement is necessary to shift client behaviors (Traux, 1968). More extensive research is needed to understand how these different therapeutic styles impact client behaviors for efficient and effective behavior change during PCIT.

In PCIT, it is intended that therapists (1) base their coaching techniques on their assessment of parents’ skills (e.g., Bahl et al., 1999), (2) use behavior principles to guide their interventions (e.g., Borrego & Urquiza, 1998), and (3) implement a wide variety of techniques to change parent behaviors (McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010). However, little research has evaluated the extent to which therapists actually do these things or the types of coaching techniques that are most efficacious (Herschell et al., 2008; Shanley & Niec, 2010). Further, an established measure does not yet exist to evaluate what happens between therapists and parents during coaching. In other words, not only do we not yet know exactly what efficacious coaching should look like, we do not have a way to measure it.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

The present study took the first step to address the pressing question—How do we assess therapist-to-parent coaching in PCIT? We developed a psychometric tool, the Therapist-Parent Interaction Coding System (TPICS), which measures both the coaching techniques used and the parent skills targeted by PCIT therapists. The primary aim of the study was to investigate the construct validity of the TPICS as a measure of coaching in PCIT. To do so, we used the TPICS to investigate coaching during families’ early treatment sessions (CDI coaching sessions 2 and 3). Our decision to focus on coaching early in treatment was based in part on the finding that coaching can significantly change parent behaviors in as few as two sessions (Shanley & Niec, 2010). Further, a PCIT treatment study with physically abusive parents found that 70% of parents demonstrated a change trajectory in the way they reinforced their children’s positive behaviors within the first three sessions of treatment (Hakman, Chaffin, Funderburk, & Silovsky, 2009). Given that coaching has the potential to lead to such swift, significant changes in parent behaviors, and given that families often drop out of treatment early in the process (Fernandez & Eyberg, 2009), it is valuable to examine what happens in those early sessions to facilitate (or impede) parents’ skill acquisition. To address our primary aim we explored three questions.

What techniques do PCIT coaches use in the early stage of coaching? This question was intended to assess whether the TPICS is capable of capturing the various techniques used by PCIT therapists during coaching. We expected that therapists would implement a wide range of techniques, tapping all the TPICS codes, and that every therapist statement would be coded, suggesting that all therapist verbalizations could be defined by the TPICS. Finally, this question was intended to provide previously unknown information regarding the frequency of different types of coaching techniques in early coaching sessions.

Does a parent’s assessed skill-level at the beginning of session guide a therapist’s coaching of that skill? Based on recommendations by PCIT researchers and clinicians that a parent’s observed parenting skills should inform the therapist’s coaching (e.g., Bahl et al., 1999; Borrego & Urquiza, 1998; Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011), we hypothesized that parenting skills assessed at the beginning of the session would be related to therapists’ type and frequency of coaching; specifically, that the frequency of parenting skills (behavior descriptions, praises, reflections) assessed at the beginning of session would be negatively correlated with directive coaching, such that lower levels of a skill would lead to more directive coaching statements focusing on the skill. Conversely, we predicted that the initial frequency of parenting skills (behavior descriptions, praises, reflections) would be positively correlated with responsive coaching, such that higher levels of a skill would lead to more responsive coaching statements focusing on the skill.

Does coaching mediate parents’ skill acquisition from one session to another? The research regarding the most effective types of therapist feedback (e.g., direct, critical, supportive) is mixed and remains to be clarified (Gulanick & Shmeck, 1977; Patterson & Forgatch, 1985; Traux, 1968). Although little empirical literature has examined PCIT coaching, evidence from the broader parenting literature suggests that a wide range of therapist feedback techniques may influence change in parenting behaviors. Thus, we hypothesized that both directive and responsive coaching of positive parenting skills (behavior descriptions, reflections, labeled praises) would mediate the relationship between parenting skills from one session to the next.

Methods

Participants

Parent-child dyads

The data used in the present study were archival, provided by a pilot randomized control trial (RCT) evaluating the efficacy of group versus individual PCIT in the treatment of young children’s conduct problems (Niec, Barnett, Prewett, Triemstra, & Shanley, 2013). Participants included families that presented to a university mental health clinic for treatment of their two- to seven-year-old children’s disruptive behaviors. In order to qualify for participation, the following requirements were met: (1) the child met DSM-IV criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder (APA, 2000) and had conduct-disordered behaviors rated by a caregiver in the clinical range of severity on a standardized measure of child behavior (e.g., Behavior Assessment System for Children-II Externalizing Composite cutoff score of T > 70); (2) at least one caregiver participated; (3) the family was not involved in Child Protective Services; and (4) children taking psychotropic medications had a period of stabilization before they entered the study.

We evaluated parent skills and therapist coaching in the second or third coaching session of the CDI phase of treatment and the subsequent coaching session for 61 parent-child dyads. These 61 dyads consisted of 47 families including 33 families with only one caregiver and 14 families (28 caregivers total) with two caregivers. Of the caregivers included in this study, 60.7% were biological mothers, 16.4% were biological fathers, 16.4% were other female caregivers (e.g., grandmothers, step-mothers), 6.5% were other male caregivers (e.g., grandfathers). When more than one caregiver participated in treatment, both caregivers received individual coaching time, and coaching sessions were coded for both caregivers.

Families in this study were randomly assigned to the individual or group treatment conditions. Families from both treatment conditions were represented, including 26 parents who received individual PCIT and 35 parents who received group PCIT. Treatment sessions were conducted once a week for approximately one hour each for families in individual PCIT and two hours for parents in group PCIT to allow time for all of the parents in the group to receive equal amounts of coaching. Both treatment conditions included the same number of sessions, the same PCIT treatment components, the same amount of coaching per dyad, and the same therapists. Differences included the presence of other families during group sessions, which allowed for group discussions before and after coaching. However, the RCT (Niec et al., 2013) revealed no differences across treatment conditions for primary outcome variables. In both treatment conditions, parents were first taught the targeted skills in a didactic session and coaching sessions followed. The RCT used a standardized protocol that included four CDI coaching sessions.

Therapists

The therapists in this study were 13 advanced doctoral students in clinical psychology. All the therapists had completed core clinical work and at least a year of PCIT training. Treatment was conducted with co-therapy teams, and all junior therapists (less than two years of experience with PCIT) were matched with advanced therapists. Therapist experience in PCIT ranged from one to five years. A licensed clinical psychologist with over 10 years of experience with PCIT supervision provided training and weekly supervision to all therapists. Dr. Sheila Eyberg, the developer of PCIT, provided case consultation when questions arose that could not be resolved by the study team.

Measures

Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System-III (DPICS-III)

The DPICS-III (Eyberg, Nelson, Duke, & Boggs, 2005) is a behavioral observation coding system that was designed to measure the quality of the interaction between parent-child dyads and parents’ use of effective parenting skills. We assessed parents’ interactions with their children during the five-minute Child-Led Play portion of the measure administered during each CDI treatment session. The DPICS categories coded in this study include Unlabeled and Labeled Praises, Reflections, Behavior Descriptions, Negative Talk, Questions, and Indirect and Direct Commands (see Table 1). The DPICS-III has been standardized for use with children ages 3 through 6. Interrater reliability on parent verbalizations has ranged from correlations of 0.69 (Behavioral Description) to 0.99 (Direct Command) for the parent codes (Eyberg et al., 2005). DPICS accurately discriminates between families with and without a child with behavioral concerns (Robinson & Eyberg, 1981) and treatment sensitivity of the DPICS has been shown in PCIT and other treatment outcome studies (e.g., Schuhmann et al., 1998; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1990).

Therapist-Parent Interaction Coding System

The TPICS is a behavioral observational coding system developed to assess the interactions between the therapist and the parent during in vivo coaching. The TPICS manual was developed by a doctoral-level graduate student in clinical psychology and a PCIT Master Trainer, a clinical psychologist with extensive experience in PCIT who was vetted by Dr. Sheila Eyberg to disseminate the protocol with fidelity. As part of the manual development, the graduate student and PCIT Master Trainer reviewed numerous video recordings and transcripts of PCIT coaching sessions and discussed different types of verbalizations used by therapists. They then classified these verbalizations into categories, with the primary goal that the TPICS would be able to capture all verbalizations made by the therapist with good reliability. In order to remain consistent with existing research and theory related to PCIT, the TPICS followed similar coding rules as the DPICS-III (Eyberg et al., 2005), and classified different coaching codes as being either in the category of being directive or responsive as delineated in a previous article on the subject (Borrego & Urquiza, 1998). Similarly to the DPICS-III, the TPICS is intended to code every verbalization and includes a hierarchical ranking of codes so that each verbalization can only be coded into one code if the verbalization could be classified as more than one code. The manual includes a definition of each code, illustrative examples, specific guidelines to aid discrimination between codes, and decision rules to help the coder when there is uncertainty of which code is appropriate. For research purposes, the TPICS is best used with video-recorded sessions so that reliability of coding can be evaluated.

Every TPICS code includes two components (1) the specific technique used to coach the skill (e.g., Modeling, Prompting, Constructive Correction), and (2) the skill the therapist coaches (e.g., Labeled Praise, Reflection, Behavior Description, Other). For example, if the therapist said, “That was an excellent reflection,” then that statement would be coded as giving a labeled praise about a reflection. The TPICS includes codes for ten separate coaching techniques that have been categorized as being either directive or responsive (see Table 2). The directive category includes only the coaching techniques that occur prior to a parent’s behavior. These codes include modeling the correct use of a skill (e.g., Therapist says, “I like how you are staying at the table,” with the intention of the parent repeating this statement); prompting a skill with a stem phrase, (e.g., “Thank you for…”); giving parents clear and direct commands (e.g., “Describe what he is doing”); suggesting a parent behavior with an indirect command (e.g., “Can you think of something to praise her for?”); and using specified exercises called drills (e.g., “ Let’s see how many behavior descriptions you can use in a minute”).

Responsive coaching techniques follow a parent’s behavior and include providing labeled praise for what the parent is doing (e.g., “Nice reflection”); a non-specific unlabeled praise (e.g., “Good!”), constructive corrections (e.g., “Oops, a question”); reflective descriptions (e.g., “You used a behavior description”); and making process comments about how a parent’s skills are affecting the child (e.g., “Your praise is really helping him stay calm and focused.”).

In order to code the behavior the therapist is targeting, the TPICS uses the established DPICS-III codes (e.g., labeled praise, reflection) for any of the specific parenting skills that are the focus in PCIT. Though PCIT therapists emphasize coaching specific parenting skills that are measured at the beginning of every session (e.g., behavior descriptions), they also focus on improving the overall parent-child relationship by coaching parenting behaviors such as demonstrating enjoyment of the child, and other specific selective attention strategies (e.g., ignoring). As these behaviors are important in PCIT, though they are not measured specifically, we included the category, “Other” to refer to any time a therapist coached a different parenting skill.

Procedure

DPICS coding

For the original RCT, the five-minute behavior observations of parents’ skills during treatment sessions were video-recorded and coded by a primary coder blind to the study hypotheses. Prior to coding, the primary coder was trained intensively over a year in the DPICS-III coding system and met criteria (k > .80 for all categories) with an expert-rated standard training tape. To test the reliability of the primary codes, interrater coders at an outside institution independently coded randomly selected segments. Interrater coders were blind to study hypotheses, participants’ treatment condition, and treatment session number. Of the 114 five-minute behavior observations of parents’ skills used for the present study (61 sessions that also had TPICs coding completed and 53 subsequent sessions) 37 (32%) of these sessions were coded for interrater reliability. Pearson Product Moment correlations were calculated on the child-centered interaction skills of interest for this study. Interrater reliability coefficients for Labeled Praise (r(37) =.73), Unlabeled Praise (r(37) =.79), Reflections (r(37) =.80), Behavior Descriptions (r(37) =.88), and a compilation of “Don’t” behaviors (r(37) =.83) were all found to be good.

TPICS coding

After creation of the TPICS categories, we selected and coded a segment of video-recorded CDI coding from a clinical session to serve as a criterion tape for TPICS trainees. The use of a criterion tape is consistent with the training procedure often used for research conducted on therapist behavior observation measures (e.g., Eames et al., 2009). The primary coder established initial reliability for the TPICS mastery-criteria videotape with an expert rating done by a PCIT Master Trainer. Reliability for both the coaching technique used (k = .90) and parent behavior targeted in coaching (k = .93) were high. After reliability was established, the primary coder and Master Trainer reached a consensus on the codes on which they had disagreed and established the mastery criteria for the training tape.

To evaluate the reliability of the TPICS for this study, an interrater coder was trained by the primary coder. Training included tutorial and discussion of the TPICS codes, coding transcripts, completing quizzes, and coding video-recorded sessions. The interrater coder exceeded the criterion of 80% with the expert-rated tape for both the coaching technique (k = .90) and the parent behavior that was targeted (k = .86).

Video-recorded session samples

All treatment sessions were recorded. Sessions of families who completed the CDI didactic and the first CDI coaching session were included if (1) the coaching portion of the session was 13.5 minutes or longer, (2) the segment was from the second or third CDI session, and (3) the recording was audible. Of the 80 possible recorded segments, 61 met these requirements. Of the 61 video segments in the study, 53 of the parent-child dyads attended the following week’s session. The five-minute behavior observations of parent behaviors from these 53 dyads were included as a measure of behavior change between sessions. See Table 3 for an explanation of the coded segments.

Table 3.

Portion of Treatment Session Coded

| Coding System Used | Time During Session | Behaviors Coded | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPICS-III | 5 mins. of coding prior to coaching | Parenting Behaviors | 61 |

| TPICS | First 5 mins. of coaching | Therapist Coaching | 61 |

| DPICS-III | Subsequent session 5 mins. of coding prior to coaching | Parenting Behaviors | 53 |

Note. DPICS-III = Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System-Third Edition; TPICS = Therapist-Parent Interaction Coding System.

Data Analysis

Twenty-eight caregivers included in the study had the same child, which violated the assumption of independence. A random-effects regression model (RRM) was used based on Hedeker, Gibbons, & Flay’s (1994) recommendations for clustered data. This model allows for inferences at the level of the individual parent while controlling for the degree of dependence at the family level (Hedeker et al., 1994).

The data were analyzed for outliers using standardized residuals. Based on recommendations on identifying and removing outliers, cases with standardized residuals greater than 2.5 were removed from the data set (Stevens, 1984). Outliers included therapists whose number of coaching statements was higher or lower than what would be predicted given the parent’s skills level. Two outliers were identified for labeled praises, three outliers were identified for reflections, and two outliers were identified for behavior descriptions. Analyses were run with and without outliers, and results were significantly influenced for labeled praises and behavior descriptions. Because the outliers did not appear to be related to error, and are instead representative of actual outliers from the population, results both with and without the outliers are reported when there was an influence on statistical significance (Stevens, 1984).

In order to test the hypothesis that coaching mediated the relationship between parenting skills at the beginning of one treatment session and the subsequent session, Baron and Kenny’s (1986) conceptual and statistical recommendations for testing mediation were used. First, the parent skill level during the subsequent session was regressed on the skill level from the previous session to determine if there was an effect to mediate. Then the frequency of use of a coaching technique (e.g., responsive coaching) was regressed on initial parent skill level. In the third regression, the parent’s skill level in the subsequent session was regressed on the coaching technique.

Results

Interrater Reliability

One primary coder completed the TPICS coding. Of the 61 video-recorded sessions, 16 (≈ 25%) were randomly selected for reliability coding by a second, independent coder. Kappa tests were run for interrater reliability on the PCIT coaching technique used and the category of parenting skill coached. Interrater reliability was excellent for both coaching technique (k = .94) and parent behavior (k = .90). Pearson Product Moment correlations were used to analyze the interrater reliability of specific therapist and parent codes (Table 4). Reliability coefficients were very good to excellent (r = .87 to 1.0), with the exception of two coaching techniques (Reflective Description [r = .65], Corrective Criticism [r = .70]) and one category of parent behavior (Other [r = .63]), which demonstrated adequate reliability. The TPICS demonstrated the breadth and clarity of codes necessary to code every therapist verbalization during coaching with adequate to excellent reliability.

Table 4.

Interrater Reliability of the Therapist-Parent Interaction Coding System

| Coaching Techniques | r |

|---|---|

| Total Directive | .99 |

| Model | .99 |

| Prompt | .98 |

| Indirect/Direct Command | .88 |

| Drills | 1.0 |

| Total Responsive | .99 |

| Labeled Praises | .96 |

| Process Comments | .99 |

| Reflective Descriptions | .65 |

| Corrective Criticism | .70 |

| Unlabeled Praises | 1.0 |

|

| |

| Targeted Parent Behavior | |

|

| |

| Behavior Description | .95 |

| Labeled Praises | .90 |

| Reflections | .96 |

| Don’t Skills | .87 |

| Other | .63 |

Note. n = 16.

What Techniques Do Coaches Use?

As expected, coaches used a variety of techniques during the early coaching sessions (Table 5). Modeling (M = 11.72, SD =6.33) and Labeled Praises (M = 9.23, SD = 4.67) were the techniques coaches used most frequently, while the techniques that were used the least were Drills (M = .05, SD = .22), Corrective Criticisms (M = .46, SD = .81), and Process Comments (M = .23, SD = .53). Test of normality suggested that the majority of codes were used rarely and positively skewed, with the only exceptions being Modeling and Labeled Praises, which were normally distributed (Table 6). Composites of all directive and responsive coaching techniques revealed that, on average, therapists used significantly more directive coaching statements (M = 14.11, SD = 6.35) than responsive coaching statements (M = 10.33, SD = 5.15, t(60) = 3.23, p < .01). That is, coaches told parents what to say more often than they praised them for saying it or explained what they said.

Table 5.

Therapist Coaching Techniques during Five-Minute TPICS

| Minimum | Maximum | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Directive | 2 | 33 | 14.11 | 6.35 |

| Model | 1 | 28 | 11.72 | 6.33 |

| Prompt | 0 | 4 | 1.07 | 1.25 |

| Indirect/Direct Command | 0 | 6 | 1.95 | 1.74 |

| Drills | 0 | 1 | .05 | .22 |

| Total Responsive | 2 | 23 | 10.33 | 5.15 |

| Labeled Praises | 2 | 22 | 9.23 | 4.67 |

| Process Comments | 0 | 2 | .23 | .53 |

| Reflective Descriptions | 0 | 4 | .87 | 1.16 |

| Corrective Criticism | 0 | 4 | .46 | .81 |

| Unlabeled Praises | 0 | 23 | 4.26 | 4.88 |

Note. N = 61. M = Mean. SD = Standard Deviation.

Table 6.

Normality of Therapist Coaching Techniques

| Shapiro-Wilk Statistic | |

|---|---|

| Model | .95* |

| Prompt | .52 |

| Indirect/Direct Command | .86 |

| Drills | .23 |

| Labeled Praises | .96** |

| Process Comments | .67 |

| Reflective Descriptions | .76 |

| Corrective Criticism | .62 |

| Unlabeled Praises | .79 |

Note. N = 61.

= p > .01.

p > .05

In regards to the parenting behaviors therapists targeted during coaching, by far the most frequently targeted behaviors were the “Do” skills (i.e., parenting behaviors meant to be increased; M = 24.43, SD =7.08). Therapists also frequently coached “other” parent behaviors (M = 10.15, SD = 7.67). “Other” parent behaviors included different skills that are addressed in PCIT, but not systematically measured by the DPICS-III, such as ignoring negative child behavior, being enthusiastic, and following the child’s lead. Of the targeted parenting “Do” behaviors, therapists targeted labeled praises most frequently (M = 8.15, SD =4.25) and behavior descriptions least often (M = 5.93, SD =3.91). Therapists rarely targeted “Don’t” behaviors (i.e., parenting behaviors meant to be decreased; M = 1.07, SD = 1.25), suggesting the possibility they used other forms of behavior modification (e.g., selective attention and shaping) to address these behaviors instead (Table 7).

Table 7.

Parent Skills Coached during Five-Minute TPICS

| Minimum | Maximum | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total “Do” Skills | 12 | 44 | 24.43 | 7.08 |

| Labeled Praises | 1 | 23 | 8.15 | 4.25 |

| Behavior Descriptions | 0 | 22 | 5.93 | 3.91 |

| Reflections | 0 | 30 | 6.66 | 4.71 |

| Total “Don’t” Behaviors | 0 | 5 | 1.07 | 1.25 |

| Total Other Behaviors | 0 | 43 | 10.15 | 7.67 |

Note. N = 61. M = Mean. SD = Standard Deviation.

Does a parent’s skill-level guide a therapist’s coaching?

Directive coaching

We used a RRM to test the hypothesis that parents with fewer skills would receive more directive coaching statements (e.g., modeling, prompting, commands, and drills). Using the full sample, directive coaching techniques were significantly, negatively related to parents’ use of behavior descriptions (β(61) = −.39, t(59.97) = −3.35, p = .001). That is, when parents offered fewer behavior descriptions during the assessment of their interactions with their children, coaches were more likely to use directive techniques to increase parents’ skill acquisition. No significant relationship was found between directive techniques and parents’ use of labeled praises, (β(61) = −.16, t(53.17) = −1.34, p >.05, or reflections, β(61) = −.12, t(46.36) = −.93, p > .05) with the full sample. However, when the outliers were removed from the analyses, directive coaching techniques were also significantly and negatively related with a parent’s skill use of labeled praises, β(59) = −.33, t(44.88) = −2.85, p < .01. Significance levels were not impacted for behavior descriptions, β(59) = −.38, t(57.82) = −3.53, p = .001, or reflections, β(58) = −.08, t(51.31) = −.63, p > .05, when outliers were removed. Thus, as expected, therapists used more directive coaching techniques when parents demonstrated deficits in their use of the child-centered skills labeled praises and behavior descriptions.

Responsive coaching

A RRM was also used to test the hypothesis that therapists would provide more responsive coaching statements (e.g., praise) to parents when their use of a skill was already frequent. In other words, if parents spontaneously used a skill often, the therapist would have many opportunities to reinforce the parents’ demonstrations of that skill. As expected, when outliers were removed from the analyses, responsive coaching techniques were significantly, positively correlated with labeled praises, β(59) = .29, t(58.00) = 2.35, p < .05. A relationship was not found for behavior descriptions, β(59) = .12, t(58.99) = 1.04, p > .05, or reflections, β(58) = .12, t(53.62) = .24, p > .05. That is, parents who already gave their children many labeled praises received many responsive statements from coaches. With outliers included, no significant relationships existed between responsive coaching techniques and parents’ skill levels in the child-centered skills. For a summary of the relationships between parent’s skills and coaching styles see Table 8.

Table 8.

Relationships between Parenting Skills and Therapist Coaching

| Coaching Technique | Parenting Skill | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | BD | LP | |

| Directive Coaching | −.08 | −.38** | −.33** |

| Responsive Coaching | .12 | .12 | .29* |

Note. RF = DPICS-III assessment of reflections. BD = DPICS-III assessment of behavior descriptions. LP = DPICS-III assessment of labeled praises. Outliers removed. N = 58 for RF. N = 59 for BD. N = 59 for LP.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Does coaching mediate parents’ skill acquisition?

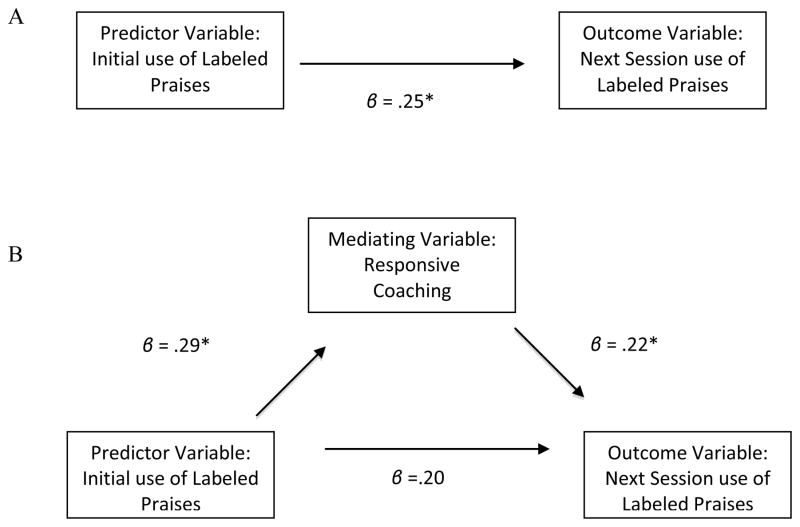

Baron & Kenny’s (1986) preconditions for mediation were tested for both directive and responsive coaching with the development of the three targeted parenting skills (i.e., behavior descriptions, labeled praises, and reflections) from one session to the next. Preconditions for mediation were met for labeled praises with responsive coaching (Figure 1). To test the mediational model, parent skill level from the subsequent session was regressed on both parent skill level during the initial session and the coaching technique targeting this skill. The significant relationship between the parents’ initial skill level and next-session skill level, β(52) = .25, t(47.72) = 1.85, p < .05, was no longer significant when responsive coaching was added to the regression equation β(52) = .20, t(49) = 1.44, p = .08. This suggests that responsive coaching had a partial mediation effect on a parent’s skill development for labeled praises.

Figure 1.

Mediational Model for Labeled Praises and Responsive Coaching

Note. N = 52. *p < .05.

Directive coaching did not meet the preconditions for mediation, as this technique was not related to a parent’s skill level in the subsequent session for any of the skills.

Discussion

Understanding the therapeutic techniques that lead to successful and efficient behavior changes in parents during PCIT is important to further both the effectiveness and the dissemination of the treatment model. In order to accomplish these goals, however, a behavioral observation measure is necessary (Snyder et al., 2006). This study took the first step to address that need by developing a new behavioral observation measure, the TPICS, which allows for the direct coding of therapists’ in vivo coaching during PCIT. We explored (1) the types of coaching techniques therapists used, (2) whether the assessment of parenting skills guided that coaching, and (3) whether coaching, as measured by the TPICS, mediated parents’ skill acquisition from one session to another. As predicted, the TPICS was capable of capturing a variety of coaching techniques implemented by therapists during the early stage of coaching. Coaching related to the assessment of parenting skills such as behavior descriptions and labeled praises, but not to parents’ reflections. Also as expected, responsive coaching techniques mediated the acquisition of parenting skills from one session to another.

Therapists Use a Range of Coaching Techniques

The TPICS tapped variations in therapist coaching styles during the early PCIT coaching sessions. As predicted, therapists implemented a range of both directive and responsive techniques, with modeling (e.g., Therapist says, for parent to repeat, “You’re building a blue tower.”) and labeled praises to parents (“Great job describing his behavior!”) being the most frequently used techniques. Overall, therapists targeted the “Do” skills (i.e., labeled praises, reflections, behavior descriptions) approximately five times for every minute of coaching; whereas they coached the “Don’t” skills (i.e., questions, commands, criticisms) once in five minutes of coaching. This is consistent with recommendations that during the first phase of treatment, PCIT coaches should selectively ignore parent behaviors that are targeted for reduction and attend enthusiastically to parent behaviors that are targeted to increase (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011).

Therapist Coaching is Guided by Parent Skills

PCIT is an assessment-driven intervention that emphasizes actual behavior observation of parent skills to guide therapists’ in vivo feedback (Bahl et al., 1999). Previous to this study, however, no empirical evidence supported this link. Our findings support the assumption that therapists use the behavior observations at the beginning of a session to guide their coaching during a session. Specifically, parents who were low in behavior descriptions as assessed by the DPICS-III received more directive forms of coaching from the therapist. When outliers were removed from analyses for labeled praises, parent-skill level was negatively related to directive coaching (i.e., parents with low skill levels received a high amount of directive coaching), but positively related to responsive coaching (i.e., parents who were strong with labeled praises at the beginning of session received a high level of responsive coaching throughout session). Parents’ use of reflections did not relate to therapist coaching. This suggests that while therapists often use assessment-guided treatment, they may not always do so. The finding has implications for therapist training, as the link between parent skill and therapist coaching is a key concept in PCIT. It is promising that the TPICS could reveal differences in the associations, for in the future, such a measure may be used by trainers to assess whether therapists-in-training are using the assessments of parents’ skills effectively.

Responsive Coaching Mediates Parents’ Skill Acquisition

Mediational models between parents’ skill levels and coaching techniques were evaluated to test whether responsive and directive coaching techniques would mediate the relationship between parent skills from one session to another. The mediational model was supported, with responsive coaching techniques mediating a parent’s acquisition of labeled praises. Directive coaching did not mediate parents’ session-to-session acquisition of skills.

Although older research demonstrates the value of such directive feedback as modeling in the context of therapists’ skill acquisition (Gulanick & Schmeck, 1977), research on parent resistance offers a possible explanation for the current finding. That is, in a non-coaching-based BPT intervention, parents who received directive techniques were more resistant to implementing the skills (Forgatch & Patterson, 1985). This study was potentially not able to fully capture the influence of directive coaching because it only looked at behavior changes from one session to another. Further, the limitations of a small sample require that interpretations be made with caution. Additional research is necessary to better understand the utility of directive statements, and the immediate and distal outcomes related to these coaching techniques.

Responsive coaching includes therapist statements that occur after a parent’s behavior. Such coaching may be explicitly supportive (e.g,. “Great labeled praise!”), neutral (e.g., “That was a behavior description.”), or gently corrective (“Oops, that was question.”). Key to responsive coaching is that it always follows a parents’ verbalization. Our findings provide preliminary evidence that responsive coaching accounts for a significant portion of the variance in parents’ acquisition of labeled praises during PCIT. The importance of responsive coaching in this study is consistent with past research that suggests parent compliance with therapist suggestions increases when parents feel supported by the therapist (Patterson & Forgatch, 1985). Given the numerous factors that may influence skill development (e.g., parents’ practice at home, severity of child conduct problems), it is notable that responsive coaching could mediate parents’ skill acquisition during a single coaching session. However, a need remains to look beyond skill acquisition within a session to look at skill acquisition over the length of treatment. One direction for further research would be to evaluate how coaching styles impact more distal outcomes in PCIT, such as the speed of a parent’s skill acquisition, attrition, and adherence to treatment.

The Therapist-Parent Interaction Coding System

Although research within the realm of behavioral parent training supports the relationship between a therapist’s competence and treatment outcomes for parents (Eames et al., 2009; Forgatch et al., 2005) and despite the fact that coaching is generally considered a critical mechanism of change in PCIT, prior to this study, no measure of therapists’ in vivo coaching of parent-child interaction has been reported. Our preliminary findings suggest that the TPICS has promise as a measure of therapist-parent interaction during PCIT coaching. The instrument provides a direct measure of therapist behaviors rather than general impressions of the treatment session, which is valuable because coded behavior has been associated with dropout in treatment, whereas general ratings have not (Harwood & Eyberg, 2004). Further, the TPICS assesses core components of PCIT, such as how well therapists use behavior observations of parent-child interactions to guide their coaching (Bahl et al., 1999). Initial explorations of reliability reveal that the TPICS demonstrates good interrater reliability, with most coefficients above .85. Another strength of the TPICS is that its codes are capable of measuring a breadth of different coaching styles, while these different codes can be collapsed into the responsive and directive composites in order to investigate how broad styles impact parental behavior change. Overall, the flexibility of the TPICS to reliably capture specific or broader coaching styles increases its research and clinical utility. For example, when training new PCIT therapists, it is valuable to be able to capture common and infrequent techniques in order to provide accurate feedback to the trainee and shape their skills. Finally, the use of the TPICS in this study identified a potential mediator of change in PCIT—responsive coaching. This finding and the relationships between therapist coaching and parent skills as assessed by the TPICS provide initial support for the construct validity of the measure.

Previous research on therapist coaching in PCIT has used analogue methodology with nonclinical samples (e.g., Herschell et al., 2008; Shanley & Niec, 2010). This study furthered existing literature by (1) evaluating a clinical sample of families and (2) assessing actual therapist and parent behaviors during treatment sessions. Further, this study addressed issues of non-independence by using the random-effects regression model (RRM), which controlled for the degree of dependence on a family level, allowing for inferences to be made at an individual level. The majority of research on dyads and families ignores the violations of independence, which can increase Type I and Type II errors and compromise the validity of the results (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Though it is a potential limitation of this study that the RRM did not fully control for the degree of dependence between two caregivers (e.g., mother and father)in treatment together, it was considered to be a better alternative to leaving one of the caregivers out of the study. Frequently, due to difficulties with recruitment and issues of dependence in data analysis, fathers are not included in research on child psychopathology and treatment, which has led to a bias towards mothers in the field (Phares, 1992). This study’s use of the RRM sought to address this limitation.

In order to craft future investigations of therapist coaching in behavioral parent training interventions, it is important to consider the limitations of this study. Therapists in this study were all graduate students in the same training clinic, which may limit the ability to generalize findings to therapists in community settings or to more experienced therapists. Future studies on the TPICS should use a wider variety of clinicians to improve understanding of the utility of all the different codes, especially given that many of the codes were rarely used in this population. Our sample of parents and children came from a relatively homogenous population within a rural area. Furthermore, our sample size was relatively small, and it is possible that this limited the number of significant results. Finally, this study investigated coaching only during the first phase of PCIT (i.e., child-directed interaction) and only examined behavior change from one session to the next. It is likely that different coaching styles are effective in the second phase of treatment, and it is possible that we were not able to capture the effectiveness of different coaching techniques on more distal outcomes. Given the limitations, the findings should be considered a first step in the investigations of PCIT coaching and more research is warranted. However, despite these cautions, the step taken here is important and provides a direction for further study of the question: What makes an effective PCIT coach?

Conclusions

The findings from this study have significant implications for clinical practice, research, and training issues related to PCIT. First, although evidence suggests that therapists used the behavior observations of parents’ skills to guide their coaching, it was also apparent parents’ skill did not always guide coaching. Furthermore, while directive coaching techniques (e.g., modeling) may be valuable to teach parents a skill when they do not display it spontaneously (Gulanick & Schmeck, 1977), only responsive coaching mediated the relationship between a parent’s skill level from one session to the next.

This study added to the growing body of evidence that in vivo feedback is related to behavior change in parents (Kaminski et al., 2008; Shanley & Niec, 2010) and that certain feedback styles relate to more behavior change than others (e.g., Herschell et al., 2008). The TPICS has the potential to improve the training and evaluation of PCIT therapists. With further development, the measure may allow researchers and clinical trainers to assess how effectively therapists use the parent-child behavior observations to guide their coaching and which types of coaching they favor. Research should continue to investigate whether the TPICS can measure coaching styles that predict short- and long-term behavior changes in parents in order to further develop our understanding of just what it is that makes a therapist’s coaching competent.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant to the second author from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH 070483). The authors acknowledge the research and clinical staff of the Center for Children, Families and Communities and Allyn E. Richards.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington DC: Author; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Bahl AB, Spaulding SA, McNeil CB. Treatment of noncompliance using parent child interaction therapy: A data-driven approach. Education & Treatment of Children. 1999;22(2):146–156. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R. Defiant children: A clinician’s manual for parent training. New York: Guilford Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SK, Eyberg SM. Parent-child interaction therapy: A dyadic intervention for the treatment of young children with conduct problems. Innovations in Clinical Practice: A Source Book. 2002;20:57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Borrego J, Urquiza AJ. Importance of therapist use of social reinforcement with parents as a model for parent–child relationships: An example with parent–child interaction therapy. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 1998;20(4):27–54. doi: 10.1300/J019v20n04_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27(2):180–189. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames C, Daley D, Hutchings J, Whitaker CJ, Jones K, Hughes JC, Bywater T. Treatment fidelity as a predictor of behaviour change in parents attending group-based parent training. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2009;35(5):603–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JM, Dishion TJ, Stoolmiller M. The analysis of intervention change in children and families: Methodological and conceptual issues embedded in intervention studies. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:53–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1022634807098. 0091-0627/98/02000053$15.00/0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Funderburk BW. Unpublished manuscript. University of Florida; Gainesville: 2011. Parent-child interaction therapy: Treatment manual. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Matarazzo RG. Training parents as therapists: A comparison between individual parent-child interaction training and parent group didactic training. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1980;36:492–499. doi: 10.1002/jclp.6120360218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Duke M, Boggs SR. Unpublished manuscript. 3. University of Florida; Gainesville: 2005. Manual for the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MA, Eyberg SM. Predicting treatment and follow-up attrition in parent-child interaction therapy. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:431–41. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon Model of Parent Management Training. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, McMahon R. Helping the noncompliant child: A clinician’s guide to parent training. New York: Guilford Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gulanick N, Schmeck RR. Modeling, praise, and criticism in teaching empathic responding. Counselor Education and Supervision. 1977;16:284–290. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6978.1977.tb01027.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hakman M, Chaffin M, Funderburk B, Silovsky J. Change trajectories for parent child interaction sequences during Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for child physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood MD, Eyberg SM. Therapist verbal behavior early in treatment: Relation to successful completion of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):601–612. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Flay BR. Random-effects regression models for clustered data with an example from smoking prevention research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(4):757–765. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.4.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Calzada EJ, Eyberg S, McNeil C. Clinical issues in parent-child interaction therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2002;9:16–27. doi:10777229/02/16-2751.00/0. [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Capage LC, Bahl AB, McNeil CB. The role of therapist communication style in parent-child interaction therapy. Child and Family Behavior Therapy. 2008;30:13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Helms JE, Tichenor V, Spiegel SB, O’Grady KE, Perry ES. Effects of therapist response modes in brief psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1988;35(3):222–233. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.35.3.222. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(4):567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. doi:0.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(8):1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CB, Hembree-Kigin T. Parent-child interaction therapy. 2. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Niec LN, Gering C, Abbenante . Parent-child interaction therapy: The role of play in the behavioral treatment of childhood conduct problems. In: Russ S, Niec L, editors. An evidence based approach to play in intervention and prevention: Integrating developmental and clinical science. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Niec LN, Barnett MB, Prewett M, Triemstra K, Shanley J. Central Michigan University; Mt Pleasant, MI: 2013. Group versus individual parent-child interaction therapy: A randomized control trial. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Nix RL, Bierman KL, McMahon How attendance and quality of participation affect treatment response to Parent Management Training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):429–438. doi: 10.1037/a0015028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. Therapist behavior as a determinant for client noncompliance: A paradox for the behavior modifier. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:846–851. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.6.846. doi:0022-006X/85/J00.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V. Where’s poppa? the relative lack of attention to the role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology. American Psychologist. 1992;47(5):656–664. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.47.5.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EA, Eyberg SM. The Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System: Standardization and validation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49:245–250. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.2.245. doi:0022-006X/81/4902-0245S00.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann EM, Foote RC, Eyberg SM, Boggs SR, Algina J. Efficacy of parent-child interaction therapy: Interim report of a randomized trial with short-term maintenance. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27(1):34–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley JR, Niec LN. Coaching parents to change: The impact of in vivo feedback on parent’s acquisition of skills. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(2):282–287. doi: 10.1080/15374410903532627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Reid J, Stoolmiller M, Howe G, Brown H, Dagne G, Cross W. The role of behavior observation in measurement systems for randomized prevention trials. Prevention Science. 2006;7(1):43–56. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JP. Outliers and influential data points in regression analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:334–344. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.2.334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Traux CB. Therapist interpersonal reinforcement of client self-exploration and therapeutic outcome in group psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1968;15(3):225–231. doi: 10.1037/h0025865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JC, McMullen EJ. An examination of therapist and client behavior in high- and low-alliance sessions in cognitive-behavioral therapy and process experiential therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2005;42(3):297–310. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.42.3.297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Predictors of treatment outcome in parent training for families with conduct problem children. Behavior Therapy. 1990;21(3):319–337. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80334-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Weisz JR. Mechanisms of action in youth psychotherapy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43(1):3–29. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]