Abstract

BACKGROUND

Previously, we demonstrated that 12 months of group based resistance training intervention delivered once or twice weekly provided significantly lower healthcare resource utilization costs and health benefits including improvement in health related quality of life than balance and tone exercises.

OBJECTIVE

We conducted a 12-month follow-up study to determine whether these health and cost benefits of resistance training were sustained 12 months after formal cessation of the intervention.

DESIGN

Cost-utility analysis conducted alongside a randomized controlled trial.

SETTING

Community-dwelling women aged 65 to 75 years living in Vancouver, British Columbia.

PARTICIPANTS

123 of the 155 community-dwelling women aged 65 to 75 years who originally were randomly allocated to once-weekly resistance training (n=54), twice-weekly resistance training (n=52), or to twice-weekly balance and tone exercises (i.e., control group) (n=49) participated in the 12-month follow-up study. Of these, 98 took part in the economic evaluation (twice-weekly balance and tone exercises, n=28, once-weekly resistance training, n=35; twice-weekly resistance training, n=35).

MEASUREMENTS

Our primary outcome measure was incremental cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained. Healthcare resource utilization was assessed over 21 months (2009 prices); health status was assessed using the EQ-5D to calculate QALYs using a 21 month time horizon.

RESULTS

Once- and twice-weekly resistance training were less costly than balance and tone classes with incremental mean healthcare costs of Canadian dollars (CAD$) -$1857 and -$1077, respectively. The incremental QALYs for once- and twice weekly resistance training were -0.051 and -0.081, respectively, compared with balance and tone exercises.

CONCLUSION

The cost benefits of participating in a 12-month resistance training intervention were sustained for both the once- and twice-weekly resistance training group while the health benefits were not.

Keywords: quality adjusted life year, executive functions, cognition, older adults, cost-utility analysis

INTRODUCTION

Adults over 65 years are at increasing risk for cognitive decline with implications for future costs related to their care. There would be tremendous benefit in identifying effective intervention strategies that prevented or delayed the onset of cognitive decline. Indeed, it has been estimated that if the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease could be delayed by even one year, there would be nearly 9.2 million fewer cases of disease in 2050.1

While emerging evidence from randomized controlled trials strongly suggests that exercise training may be an effective strategy against cognitive decline 2–5 – even among those with existing mild cognitive impairment 6, 7 – no study to date has examined whether such benefit persists after formal cessation of the trials. Furthermore, despite the growing interest in targeted exercise training as an alternative approach to the prevention and treatment of cognitive decline,8 no randomized controlled trial in this area of research has estimated the health and economic benefits of such interventions. Our limited health care resources emphasize the need for economic evaluations to enable decision makers to better establish health care priorities.9, 10 However, a key challenge to quantifying health and economic benefits within a trial aimed to examine the cognitive benefits of exercise is what outcome the economic evaluation should be based on. We propose that one relevant outcome for economic evaluations of randomized controlled trials of exercise and cognitive function is quality adjusted life years (QALYs).11 Using QALYs as a measure of health benefit is advantageous because they are a universal measure that captures multiple health benefits.12

Recently, we reported that 12 months of once- or twice-weekly resistance training provided better value for money compared with balance and tone (BAT) exercises (control) among community-dwelling senior women (i.e., Brain Power study).3, 13 The BAT program consisted of stretching exercises, range-of-motion exercises and basic core-strength and balance exercises. Other than body weight, no additional loading was applied to any of the exercises. There is no evidence that these exercises improve cognitive function.4 The resistance training program used a progressive, high intensity protocol performed either once- (1x RT) or twice- (2x RT) weekly depending on group allocation. The leg press machine–based exercises consisted of biceps curls, triceps extension, seated rowing, latissimus dorsi pull-down exercises, leg presses, hamstring curls, and calf raises. Other key strength exercises included minisquats, minilunges, and lunge walks. From the Brain Power study, we found that 12 months of progressive resistance training once- or twice-weekly improved selective attention and conflict resolution relative to the BAT program.3 In this present study, we conducted a 12-month follow-up study to determine whether the cost and health benefits of resistance training were sustained 12 months after formal cessation of the Brain Power study.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a 12-month follow-up study from May 2008 to April 2009 of participants who completed the 52-week Brain Power randomized controlled trial of resistance training from May 2007 to April 2008. Reassessment occurred during April and May of 2009. The assessors were blind to the participants’ original group allocation.

Participants

Of the original 155 participants in the 52-week randomized controlled trial, 123 consented to the follow-up study. We have previously reported the recruitment process for the randomized controlled trial.3 Of these, 98 took part in the economic evaluation (twice-weekly balance and tone, n=28, once-weekly resistance training, n=35; twice-weekly resistance training, n=35). We recruited women who lived in Vancouver, Canada, and: 1) were aged 65 to 75 years; 2) were living independently in their own home; 3) scored ≥ 24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); and 4) had a visual acuity of at least 20/40 with or without corrective lenses. We excluded those who: 1) had a current medical condition for which exercise is contraindicated; 2) had participated in resistance training in the last six months; 3) had a neurodegenerative disease and/or stroke; 4) had depression; 5) did not speak and understand English fluently; 6) were taking cholinesterase inhibitors; 7) were on estrogen replacement therapy; or 8) were on testosterone therapy. The number of participants in each of the treatment arms at each the stage of the 52-week trial have been previously reported.3

Ethical approval was obtained from the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute and the University of British Columbia’s Clinical Research Ethics Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Exercise Interventions

These exercise programs have been detailed elsewhere.3 Briefly, all classes were led by certified fitness instructors who received additional training and education from the study investigators. The classes were 60 minutes in duration, with a 10-minute warm-up, 40 minutes of core content, and a 10-minute cool-down. We modeled the BAT program (i.e., control) on a provincial-wide exercise program currently available to seniors in British Columbia designed to reduce falls risk among seniors with low bone mass (i.e., Osteofit). We used a progressive high intensity resistance training protocol.3 The intensity of the training stimulus was at a work range of 6 to 8 repetitions (2 sets). The training stimulus was subsequently increased using the 7-RM method, when 2 sets of 6 to 8 repetitions were completed with proper form and without discomfort.

Primary Outcome for Economic Evaluation

We used a Canadian health care system perspective for the economic evaluation. The main outcome was the incremental cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained (i.e., cost-utility).

Health Care Costs

We used a questionnaire to track health care resource utilization over 21 months. We previously reported health resource utilization details for the intervention period using a 9-month time horizon.14 Briefly, we used a questionnaire to track healthcare resource utilization prospectively for each participant for 9 months of the 12-month study period. The major resource categories were: visits to healthcare professionals, admissions or procedures carried out in a hospital, and laboratory and diagnostic tests. We also calculated the costs of delivering the 1x RT, 2x RT and BAT (comparator group) exercises for 9 months. Our base case analysis considered the costs of all healthcare resource use. We excluded research protocol driven costs from our analysis.

For the intervention and the follow-up study, we collected health care resource utilization over 12 months. The major resource categories included were: 1) appointments with health care professionals, including general practitioners, specialists, physiotherapists, etc; 2) visits, admissions or procedures carried out in a hospital; and 3) laboratory and diagnostic tests. For the 21-month economic evaluation, our base case analysis considered total healthcare resource use costs.

For each component of health resource utilization, we assigned a unit cost. All hospital admission related costs were based on a fully allocated cost model of a tertiary care hospital, Vancouver General Hospital. For health care professional unit service costs, we based costs on fee for service rates from the British Columbia Medical Services Plan 2009 price list. For specialized services such as physiotherapy, chiropractic or naturopathic medicine, we used unit costs from the British Columbia Medical Services Plan 2009 price list for each specialty. We inflated (where appropriate) costs to 2009 Canadian dollars using the consumer price index reported by Statistics Canada. Discounting was not applied.

Effectiveness Outcome

We used the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) to calculate the total QALYs for the three experimental groups. During the Brain Power intervention period, the EQ-5D was administered at three time points using a 9-month time horizon. Participants completed and returned the EQ-5D monthly during the 12-month follow-up period.

Handling Missing Data

For the follow-up to the Brain Power study, 80% (n=98) of participants had complete follow-up data for health care resource utilization, 42% (n=41) of participants had complete follow-up data for the EQ-5D at all 12 time points, and 84% (n=82) of participants had complete follow-up data for the EQ-5D for at least 8 of the 12 time points during the 1 year follow-up study. Given that missing cost data in particular introduces substantive bias into the cost estimation,15–18 we calculated the cost and effectiveness estimates using an imputed data set, and a complete case set.

Using the ice procedure in STATA, we followed recommendations for multiple imputation of missing cost and effectiveness data.15–18 For all discrete time points, we used a combination of multiple imputation and bootstrapping to estimate uncertainty caused by missing values. We determined the amount of missing data for the 1 year study follow-up period at each time point and for each participant separately for both cost and effectiveness outcomes. For each time point, we imputed missing EQ-5D and healthcare resource use values. As reported for our economic evaluation of the Brain Power study, for each missing value, we generated five possible values using multiple linear regression.16 Covariates included group, MMSE, functional comorbidity index, fall risk profile, baseline utility score, and the weight and value of the missing variable in the preceding period. The final imputed value was the mean of the five data sets created.

Cost Utility Analysis

We expressed the differences in mean costs and health outcomes in each group by reporting the incremental cost per QALY. Given that the health benefit (i.e., QALY) difference was close to zero, we used 5000 bootstrapped replications of mean cost and QALY differences.19 We used these to generate a cost utility acceptability curve to estimate the probability that once-weekly resistance training or twice-weekly resistance training is considered cost effective compared with balance and tone classes over a range of willingness to pay values.20

Sensitivity Analysis

We applied multiple imputation, bootstrapped confidence interval estimation, adjustment for imbalances in baseline utility and bootstrapped estimates of the incremental cost effectiveness and cost utility ratios. Included in our sensitivity analyses were both deterministic and probabilistic assumptions. For example, we restricted our data to a complete case analysis, thus including only participants for whom we had complete cost and effectiveness data to eliminate uncertainty caused by missing data.

RESULTS

Participants

Of the 123 who consented to the follow-up study (Table 1), 109 completed the assessment at the end of the 12-month follow-up; 37 from the once-weekly resistance training group, 41 from the twice-weekly resistance training group, and 31 from the BAT group. Of these, 35 from the once-weekly resistance training group, 35 from the twice-weekly resistance training group, and 28 from the BAT group completed the economic evaluation. The mean (SD) age of the cohort was 71.6 (3.0) years. Characteristics of the 155 participants who were randomized at baseline, the 135 who completed the 12-month intervention study, and the 123 who consented to the 12-month follow-up study have been reported previously.3 There were no differences in the baseline characteristics for the 123 participants who took part in the follow-up study compared with the 32 of the original 155 participants who declined to participate in the follow-up study.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Trial Participants Who Consented to Follow-up Study (n=123)

| Variable | BAT (n=36) | 1x RT (n=42) | 2x RT (n=45) | Total (n=123) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (yr) | 69.5 (2.8) | 69.4 (2.5) | 69.3 (3.0) | 69.4 (2.8) |

| Height (cm) | 161.3 (7.2) | 161.0 (6.9) | 162.3 (6.3) | 161.5 (6.8) |

| Weight (kg) | 68.1 (10.8) | 70.0 (15.7) | 70.1 (14.8) | 69.5 (14.0) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than Grade 9 | 0.0 (0) | 1.0 (2.4) | 0.0 (0) | 1.0 (0.8) |

| Grade 9 to 12 without certificate or diploma | 2.0 (5.6) | 2.0 (4.8) | 3.0 (6.7) | 7.0 (5.7) |

| High school certificate or diploma | 5.0 (13.9) | 7.0 (16.7) | 9.0 (20.0) | 21.0 (17.1) |

| Trades or professional certificate or diploma | 12.0 (33.3) | 10.0 (23.8) | 3.0 (6.7) | 25.0 (20.3) |

| University certificate or diploma | 3.0 (8.3) | 8.0 (19.0) | 9.0 (20.0) | 20.0 (16.3) |

| University degree | 14.0 (38.9) | 14.0 (33.3) | 21.0 (46.6) | 49.0 (39.8) |

| MMSE score (maximum 30) | 28.8 (1.2) | 28.5 (1.3) | 28.5 (1.5) | 28.6 (1.4) |

| Falls in the last 12 months (yes/no) | 12 (34.3) | 10 (23.8) | 15 (33.3) | 37 (30.3) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (maximum 15) | 0.2 (1.3) | 0.3 (1.1) | 0.9 (2.4) | 0.5 (1.8) |

| Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly | 128.7 (52.9) | 121.7 (64.6) | 122.6 (62.3) | 124.1 (60.1) |

| Timed up and go test (sec) | 6.8 (1.5) | 6.6 (1.5) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.6 (1.4) |

| Edge contrast sensitivity (dB) | 22.6 (1.4) | 22.4 (2.0) | 22.1 (1.4) | 22.3 (1.6) |

BAT = balance and tone classes; 1x RT = once-weekly resistance training; 2x RT = twice-weekly resistance training; MMSE = Mini-mental State Examination.

Economic Evaluation

Of the 123 who consented to participate in the follow-up study, 80% (n=98) of participants had complete data for health care resource utilization. These 98 participants were comparable on all baseline characteristics with the 123 individuals who consented to be part of the follow-up study (Table 2). That is, there were no differences in baseline characteristics for the 98 participants who were included in the follow-up economic evaluation compared with the 25 with no economic data. For the EQ-5D, 33% (n=41) of participants had complete follow-up data at all 12 time points and 67% (n=82) had complete follow-up data for at least 8 of the 12 time points. There were no significant differences in drop outs or response rates between the three experimental groups. Unit costs for health care cost items detailed by treatment group are provided in Table 3. Overall, admission to hospital was the main driver of total health resource utilization.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants Who Consented to Follow-up Economic Evaluation (n=98)

| Variable | BAT (n=28) | 1x RT (n=35) | 2x RT (n=35) | Total (n=98) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (yr) | 69.6 (2.9) | 69.7 (2.8) | 69.2 (3.1) | 69.5 (2.9) |

| Height (cm) | 160.7 (7.4) | 161.9 (7.3) | 162.4 (6.3) | 161.7 (7.0) |

| Weight (kg) | 68.4 (10.5) | 71.9 (16.8) | 71.4 (15.6) | 70.7 (14.9) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than Grade 9 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Grade 9 to 12 without certificate or diploma | 1 (3.6) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (8.6) | 6 (6.1) |

| High school certificate or diploma | 5 (17.9) | 6 (17.1) | 7 (20.0) | 18 (18.4) |

| Trades or professional certificate or diploma | 8 (28.6) | 7 (20.0) | 2 (5.7) | 17 (17.3) |

| University certificate or diploma | 2 (7.1) | 8 (22.9) | 6 (17.1) | 16 (16.3) |

| University degree | 12 (42.9) | 11 (31.4) | 7 (20.0) | 30 (30.6) |

| MMSE score (max. 30 pts) | 29.0 (1.2) | 28.3 (1.3) | 28.5 (1.7) | 28.5 (1.4) |

| Falls in the Last 12 Months (yes) | 9 (32.1) | 9 (25.7) | 10 (28.6) | 28 (28.6) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (max. 15 pts) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (1.2) | 0.8 (2.5) | 0.4 (1.7) |

| Edge Contrast Sensitivity (dB) | 22.6 (1.4) | 22.1 (2.1) | 22.2 (1.8) | 22.3 (1.7) |

BAT = balance and tone classes; 1x RT = once-weekly resistance training; 2x RT = twice-weekly resistance training; MMSE = Mini-mental State Examination.

Table 3.

Unit Costs for Each Component of Health Resource Utilization and Base Case Analysis

| Item | Value 2009 CAD$ | Unit | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| BAT (n=28) | 1x RT (n=35) | 2x RT (n=35) | |||

| Health care professional visit, mean (standard deviation) | 783 (430) | 622 (506) | 729 (684) | Cost per visit | 2009 Medical services plan |

| Admission to hospital, mean (standard deviation) | 1526 (5059) | 683 (2202) | 588 (3257) | Cost per day | 2005 Vancouver General Hospital fully allocated cost model* |

| Laboratory procedures, mean (standard deviation) | 122 (134) | 254 (612) | 132 (207) | Cost per procedure | 2009 Medical services plan |

| Total health resource utilization, mean (standard deviation) | 2580 (4998) | 1126 (2005) | 1591 (3179) | Cost per 21- months | 2009 Medical services plan |

| Base Case Analysis | |||||

| Incremental cost (total health resource utilization) | reference | -$1857 | -$1077 | ||

| QALY mean (SD) based on: | |||||

| EQ-5D | 5.45 (0.73) | 5.40 (1.07) | 5.49 (0.78) | ||

| Adjusted incremental QALY based on: | |||||

| EQ-5D† | 0 (reference) | -0.051 | -0.081 | ||

BAT = balance and tone classes; 1x RT = once-weekly resistance training; 2x RT = twice-weekly resistance training; QALY = quality adjusted life years; EQ-5D = EuroQol-5D.

Taken from the fully allocated cost model at Vancouver General Hospital.

Incremental QALYs were adjusted for the baseline utility using a linear regression model.

After controlling for baseline EQ-5D levels, the incremental QALY after 12 months calculated using the EQ-5D was -0.051 for the once-weekly resistance training group and -0.081 for the twice-weekly resistance training group compared with balance and tone classes (Table 3).

Based on the point estimates for total healthcare resource use and QALYs calculated from the EQ-5D for our base case analysis, we found that the incremental cost-utility ratio for once-weekly resistance training per QALY gained was less costly and equally effective compared with BAT. The incremental cost-utility ratio for twice-weekly resistance training per QALY gained was less costly and less effective compared with BAT.

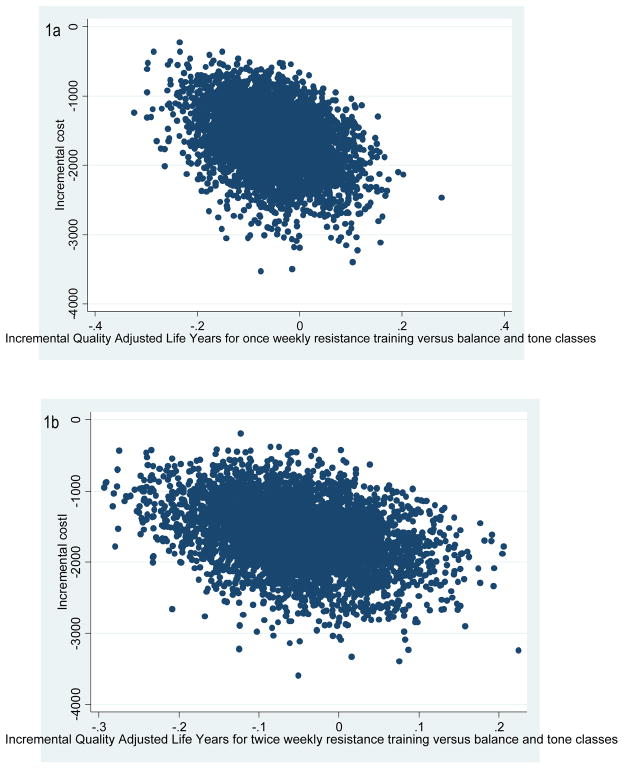

The origin of the cost-effectiveness plane indicated no difference in costs or health benefits between the intervention and the comparator. We found that for once-weekly resistance training compared with BAT, half of the bootstrapped cycles (51% of the 5000 cycles in southeast quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane) were represented in the southeast quadrant and half in the southwest quadrant. Thus, for once-weekly resistance training compared with BAT, ~50% of the bootstrapped cycles were also represented in the southwest and southeast quadrant, indicating lower costs and no net health benefits when compared with BAT. We found that for twice-weekly resistance training compared with BAT, 70% of the bootstrapped cycles were also represented in the southwest quadrant, indicating lower costs and lower health benefits when compared with BAT.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that in 65 to 75 year old community-dwelling women, 12 months of progressive resistance training once- or twice-weekly resulted in lower health resource utilization costs and improved health outcomes, compared with twice-weekly balance and toning exercises. Based on the point estimates from our base case analysis during the intervention, we found that both once- and twice-weekly resistance training groups incurred significantly lower health resource utilization costs (p<0.05) and both were more effective than twice-weekly balance and tone classes. Follow-up 12 months after formal cessation of the Brain Power study intervention indicated that health benefits obtained during the trial were not sustained; however, economic benefits for both groups were sustained. Two potential reasons for these findings include: 1) the once-weekly resistance training group consistently had the greatest level of leisure time physical activity during the intervention and follow-up period, indicating they were able to sustain a once-weekly intensive program beyond the intervention period, and 2) the twice-weekly resistance training group did not sustain as frequent physical activity levels post intervention compared with the once-weekly resistance training group, thus potentially experiencing a greater decline in health benefits.

Decision makers have threshold amounts of money that they are willing to pay when choosing between existing community programs and alternative effective interventions. Given that both resistance training interventions in our study resulted in lower healthcare resource utilization costs, these two resistance training options may be considered economically attractive alternatives to balance and tone classes.

Uncertainty in Findings

To quantify uncertainty, we used multiple imputation for missing values of the EQ-5D and healthcare resource utilization and nonparametric bootstrapping to estimate the uncertainty around the incremental cost effectiveness/utility ratios. From both our probabilistic and selective one way sensitivity analyses, we found that there were few differences between our imputed data analysis, complete and available case analyses.

Limitations

Our comparator used was based on classes commonly available to seniors in the community (ie, Osteofit). This provides an extremely conservative estimate of effectiveness.

Strengths

A unique aspect of our study is that we followed individuals beyond the duration of the clinical trial. This is the first long-term follow-up of a resistance training intervention in older adults. Further, we collected health state utility value information monthly for our 1-year follow-up study, using the EQ-5D, to provide a more accurate estimation of QALYs and to minimize recall bias.

Conclusions

Despite the fact that the direct health benefits from 12 months of resistance training were not sustained, a significant reduction in healthcare resource utilization costs persisted after completion of both once-and twice-weekly resistance training compared with balance and tone classes. The reduction in health care resource utilization was due in part to lower fall related costs. These novel findings should remain guarded, as further studies are needed to explore methods of assessing health outcomes and defining economic cost items that are the key components driving the results of economic evaluations.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Cost effective plane depicting the 95% confidence ellipses of incremental cost and effectiveness for comparison between once-weekly resistance training and balance and tone (comparator) with Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) estimated from the EuroQol (EQ-5D);

1b. Cost effective plane depicting the 95% confidence ellipses of incremental cost and effectiveness for comparison between twice-weekly resistance training and balance and tone (comparator) with QALYs estimated from the EQ-5D.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vancouver South Slope YMCA management and members who enthusiastically supported the study by allowing access to participants for the training intervention. Drs. Liu-Ambrose and Marra are Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholars. Dr. Marra is a Canada Research Chair in Pharmaceutical Outcomes. Dr. Davis is funded by a Canadian Institute for Health Research Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Checklist: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | JCD | CAM | MCR | MN | TLA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Grants/Funds | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Honoraria | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Speaker Forum | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Consultant | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Stocks | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Royalties | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Expert Testimony | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Board Member | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Patents | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Personal Relationship | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

Author Contributions: TLA, JCD, CAM, MCR, MN: Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript, and critical review of manuscript.

JCD had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Sponsor’s Role: None.

TRIAL REGISTRATION

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00426881

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi H. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu-Ambrose T, Donaldson MG, Ahamed Y, et al. Otago home-based strength and balance retraining improves executive functioning in older fallers: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1821–1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu-Ambrose T, Nagamatsu LS, Graf P, Beattie BL, Ashe MC, Handy TC. Resistance training and executive functions: a 12-month randomized controlled trial. Archives of internal medicine. 2010;170:170–178. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colcombe SJ, Kramer AF, Erickson KI, et al. Cardiovascular fitness, cortical plasticity, and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3316–3321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400266101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassilhas RC, Viana VA, Grassmann V, et al. The impact of resistance exercise on the cognitive function of the elderly. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2007;39:1401–1407. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318060111f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Archives of neurology. 2010;67:71–79. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al. Effect of Physical Activity on Cognitive Function in Older Adults at Risk for Alzheimer Disease: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2008;300:1027–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang YK, Etnier JL. Exploring the dose-response relationship between resistance exercise intensity and cognitive function. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;31:640–656. doi: 10.1123/jsep.31.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mooney G, Wiseman V. Burden of disease and priority setting. Health Econ. 2000;9:369–372. doi: 10.1002/1099-1050(200007)9:5<369::aid-hec536>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiseman V, Mooney G. Burden of illness estimates for priority setting: a debate revisited. Health Policy. 1998;43:243–251. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(98)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis JC, Hsiung GYR, Liu-Ambrose T. Challenges moving forward with economic evaluations of exercise intervention strategies aimed at combating cognitive impairment and dementia. British Journal of Sport Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.077990. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation for health care programmes. 3. New York. United States of America: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis JC, Marra CA, Robertson MC, et al. Economic evaluation of dose-response resistance training in older women: a cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis JC, Marra CA, Ashe MC, Khan KM, Robertson MC, TL-A Economic Evaluation of Dose-Response Resistance Training Among Older Women: A Cost Effectiveness and Cost Utility Analysis Analysis. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; Halifax, Nova Scotia. April 18–20, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briggs A, Clark T, Wolstenholme J, Clarke P. Missing.. presumed at random: cost- analysis of incomplete data. Health Econ. 2003;12:377–392. doi: 10.1002/hec.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manca A, Palmer S. Handling missing data in patient-level cost-effectiveness analysis alongside randomised clinical trials. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2005;4:65–75. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200504020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oostenbrink JB, Al MJ. The analysis of incomplete cost data due to dropout. Health Econ. 2005;14:763–776. doi: 10.1002/hec.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oostenbrink JB, Al MJ, Rutten-van Molken MP. Methods to analyse cost data of patients who withdraw in a clinical trial setting. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:1103–1112. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200321150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briggs AH, Gray AM. Handling uncertainty when performing economic evaluation of healthcare interventions. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3:1–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fenwick E, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Representing uncertainty: the role of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Health Econ. 2001;10:779–787. doi: 10.1002/hec.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]