Abstract

In the randomized phase III trial N0147 for resected colon cancer, the early trial versions included treatment arms of FOLFIRI (irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin) with and without cetuximab, in addition to FOLFOX (oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin) with and without cetuximab. In the small group receiving FOLFIRI plus cetuximab evidence of possible benefit was noted. However, pending results of a randomized trial, FOLFIRI plus cetuximab should not be considered as an option for adjuvant therapy.

Background

Two arms with FOLFIRI, with or without cetuximab, were initially included in the randomized phase III intergroup clinical trial NCCTG (North Central Cancer Treatment Group) N0147. When other contemporary trials demonstrated no benefit to using irinotecan as adjuvant therapy, the FOLFIRI-containing arms were discontinued. We report the clinical outcomes for patients randomized to FOLFIRI with or without cetuximab.

Patients and Methods

After resection, patients were randomized to 12 biweekly cycles of FOLFIRI, with or without cetuximab. KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) mutation status was retrospectively determined in a central lab. The primary end point was disease-free survival (DFS). Secondary end points included overall survival (OS) and toxicity.

Results

One hundred and six patients received FOLFIRI and 40 received FOLFIRI plus cetuximab. Median follow-up was 5.95 years (range, 0.1–7.0 years). The addition of cetuximab showed a trend toward improved DFS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.53; 95% CI, 0.26–1.1; P = .09) and OS (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.17–1.16; P = .10) in the overall group, regardless of KRAS status, and in patients with wild type KRAS. Grade ≥ 3 nonhematologic adverse effects were significantly increased in the cetuximab versus FOLFIRI-alone arm (68% vs. 46%; P = .02). Adjuvant FOLFIRI resulted in a 3-year DFS less than that expected for FOLFOX.

Conclusion

In this small randomized subset of patients with resected stage III colon cancer, the addition of cetuximab to FOLFIRI was associated with a nonsignificant trend toward improved DFS and OS. Nevertheless, considering the limitations of this analysis, FOLFOX without the addition of a biologic agent remains the standard of care for adjuvant therapy in resected stage III colon cancer.

Keywords: Adjuvant therapy, Disease free survival, Overall survival, Response rate

Introduction

The addition of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted monoclonal antibody cetuximab has been shown to improve outcomes of standard chemotherapy regimens in metastatic colorectal cancer.1 Past studies demonstrated the added benefit of cetuximab to FOLFOX (oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin) for wild type Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (wtKRAS) patients with metastatic colon cancer.2,3 The CRYSTAL (Cetuximab Combined with Irinotecan in First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer) trial demonstrated improvement in tumor response rate and reduced risk of progression, but not overall survival (OS).1 In contrast, the benefit of cetuximab added to FOLFOX has not been observed in the adjuvant setting for patients with resected stage III colon cancer.4

The initial design of the phase III trial N0147 included randomization to FOLFOX, FOLFIRI (irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin), or a sequential regimen of FOLFOX followed by FOLFIRI. Shortly after opening for enrollment, the trial was modified to also include a randomization to one of the chemotherapy arms with or without cetuximab. However, in August 2008, randomization was restricted to treatment with FOLFOX with or without cetuximab after CALGB (Cancer and Leukemia Group B) 89803, PETACC-3 (Pan European Trial Adjuvant Colon Cancer), and Accord02 trials showed no significant benefit to the use of irinotecan in adjuvant therapy.5–7 We report the outcomes for patients given FOLFIRI with or without cetuximab before this protocol change.

Patients and Methods

This trial was designed by the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the NCI-sponsored cooperative groups. Additionally, Bristol Myers Squibb, ImClone, Sanofi-Aventis, and Pfizer participated in the development of the trial and provided unrestricted research support. Data were collected and managed by the Clinical Trials Support Unit of the NCI in collaboration with the NCCTG. All data analyses were performed by NCCTG. NCCTG maintains full unrestricted rights to publication of the trial data. Confidentiality of all data and prepublication results are maintained by the NCCTG.

Patients

Eligible patients were age 18 years or older with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0, 1, or 2, and histologically proven stage III (any T, N1 or N2, M0) adenocarcinoma of the colon, at least 12 cm from the anal verge. For patients with locally advanced tumors, an en bloc resection was required. Other eligibility criteria included at least 1 pathologically confirmed involved lymph node and adequate blood counts, liver, and kidney function. No previous chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiotherapy for colon cancer was allowed. The study protocol was approved by the investigational review boards of participating centers before patient enrollment. All participants provided written informed consent before study enrollment and were required to submit blood and tumor tissue before randomization.

Treatment

N0147 initially opened to accrual with 3 treatment arms: mFOLFOX6 (12 cycles), FOLFIRI (12 cycles), and a hybrid regimen of mFOLFOX6 (6 cycles) followed sequentially with FOLFIRI (6 cycles). Cetuximab was added to the study in the fall of 2004, modifying the trial design to a total of 6 treatment arms.4 Patients were accrued to the FOLFIRI-containing arms between February 2004 and May 2005. All patients who were concurrently randomized after the addition of cetuximab were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to 1 of the 6 chemotherapy arms. The FOLFIRI-containing treatment arms were discontinued from N0147 as of May 2005. Patients who had not yet completed the planned therapy were allowed to remain on-study and receive mFOLFOX6 with or without cetuximab. Patients continued to be treated and followed per protocol, irrespective of the discontinuation of treatment arms. The results for the 2 FOLFIRI arms are presented in this report.

FOLFIRI consisted of 12 biweekly cycles of irinotecan 180 mg/m2 on day 1 with leucovorin 400 mg/m2 and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 400 mg/m2 bolus, all given intravenously (I.V.), then 46-hour I.V. 5-FU 2400 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2. Cetuximab was administered as 400 mg/m2 over 2 hours on day 1 of cycle 1, then 250 mg/m2 over 1 hour on day 8 and day 1 and 8 of each successive cycle. Patients received standard supportive care including an antihistamine before cetuximab and antiemetic therapy, as needed. In addition, all patients received written instructions on the management of diarrhea. Protocol-directed guidelines were provided for dose modifications of treatment-related toxicities.

Adverse Events, Disease Assessments, and Follow-Up

After initiation of therapy, patients were seen every 2 weeks for assessment of toxicity and consideration of additional protocol-directed therapy. Adverse events were graded according to the NCI Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.8 At each assessment a complete blood count and chemistries were obtained together with a physical examination. Assessments for the follow-up visits included physical examination, laboratory tests, and radiologic imaging (abdominal computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasound and chest x-ray or computed tomography) to evaluate for recurrence. Recurrence was evaluated every 6 months until 5 years after randomization. A follow-up colonoscopy was done at 1 year and then 4 years after resection. The diagnosis of a recurrence was centrally reviewed and required radiologic imaging and, if necessary, cytology or biopsy results were obtained.

KRAS and BRAF Mutation Status

The KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) mutation status was assessed retrospectively for all patients in this cohort. KRAS mutation status was determined using DNA from macrodissected, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue with the DxS mutation test kit KR-03/04 (DxS, Manchester, UK), together with the LightCycler 480 (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN), assessing for 7 different potential mutations in codons 12 and 13.9 The level of detection was set at 5%. Assessment for the BRAF (v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1) V600E mutation was performed using a Mayo Clinic-developed assay using a fluorescent allele-specific polymerase chain reaction as described elsewhere.4

Statistical Methods

This analysis of the FOLFIRI with or without cetuximab treatment arms of N0147, should be considered as hypothesis-generating. Considering the sequential additions and subtractions of treatment arms, patients enrolled to FOLFIRI-containing arms were not all enrolled in the same time period. In addition, with only 45 patients enrolled to receive FOLFIRI plus cetuximab and 111 enrolled to receive FOLFIRI alone, the ability to confidently interpret outcomes is limited, because only 65% of these patients had wtKRAS-expressing tumors.

The primary end point was disease-free survival (DFS), defined as the first documented event of recurrence of colon cancer or death from any cause. Secondary end points included time to recurrence (TTR), OS, and toxicity. Using the randomization date as the start of the interval, patients were classified as having an event for TTR at the date of recurrence; otherwise, they were classified as event-free at their date of last disease assessment. The DFS end point classified an event at the earliest date of recurrence or death; otherwise, patients were classified as event-free at their date of last disease assessment. For the calculation of each patient’s disease-free interval, patients were censored for recurrence and survival at 5 years after randomization. The interval from randomization to death, date of last contact, or date lost to follow-up was used for OS, with patients censored for survival at the earliest of the date of the last contact or date lost to follow-up.

Patients were randomized using a dynamic allocation procedure.10 Stratification factors at the randomization were T-stage (T1-2 vs. T3 vs. T4), number of positive nodes (1–3 vs. ≥ 4), and high histology (poorly differentiated [Grade 3], undifferentiated [Grade 4]) versus low histology (well differentiated [Grade 1], moderately differentiated [Grade 2–3]). The original analysis plan used intent-to-treat principles. However, in recognition that this subanalysis lends itself more to a large randomized pilot study, select cases were excluded.

Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to estimate the distributions of TTR, DFS, and OS.11 The log-rank test was used to test for differences in the distributions of TTR, DFS, and OS, whereas the score and χ2 statistics were used to test for the significance of models and individual covariates in the Cox proportional hazards models reviewed.12 In a sensitivity analysis, a time-varying Cox regression adjusted for initiation of oxaliplatin in patients who crossed over from FOLFIRI to FOLFOX was also performed. All programming was performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc) and R version 2.14.13

Results

Patient Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 outlines patient characteristics, and the CONSORT diagram shows the flow of patients throughout the course of the study. Five patients not receiving any protocol-specified treatment and 5 patients classified as ineligible because of positive surgical margins or improper histology were excluded from this analysis. Two patients, who started treatment later than required or underwent pretreatment blood draws outside of the time boundaries specified in the test schedule, remained in this analysis. Therefore, a total of 146 patients (106 FOLFIRI; 40 FOLFIRI with cetuximab) are included. Patient and disease characteristics did not differ significantly according to treatment group.

Table 1.

Patient and Disease Characteristics at Study Entry

| Characteristic | FOLFIRI (n = 106) | FOLFIRI With Cetuximab (n = 40) |

Total (n = 146) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age (Range), Years | 57.0 (25.0–82.0) | 59.0 (30.0–82.0) | 58.0 (25.0–82.0) | .45a |

| Sex | .81b | |||

| Female | 50 (47.2) | 18 (45) | 68 (46.6) | |

| Male | 56 (52.8) | 22 (55) | 78 (53.4) | |

| Race | .67c | |||

| White | 95 (89.6) | 34 (85) | 129 (88.4) | |

| Black or African American | 6 (5.7) | 3 (7.5) | 9 (6.2) | |

| Asian | 4 (3.8) | 3 (7.5) | 7 (4.8) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Adherence | .83b | |||

| Present | 17 (16) | 7 (17.5) | 24 (16.4) | |

| Bowel Obstruction | .59c | |||

| Present | 15 (14.2) | 4 (10) | 19 (13) | |

| Bowel Perforation | .73c | |||

| Present | 9 (8.5) | 2 (5) | 11 (7.5) | |

| Histology | .76b | |||

| High (Grade 3–4) | 24 (22.6) | 10 (25) | 34 (23.3) | |

| Low (Grade 1–2) | 82 (77.4) | 30 (75) | 112 (76.7) | |

| Lymph Node Involvement | .99b | |||

| 1–3 | 69 (65.1) | 26 (65) | 95 (65.1) | |

| ≥4 | 37 (34.9) | 14 (35) | 51 (34.9) | |

| Stage | .73c | |||

| T1 or T2 | 17 (16) | 5 (12.5) | 22 (15.1) | |

| T3 | 74 (69.8) | 31 (77.5) | 105 (71.9) | |

| T4 | 15 (14.2) | 4 (10) | 19 (13) | |

| Site of Diseased | .88b | |||

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Proximal (right) | 61 (58.7) | 24 (60) | 85 (59) | |

| Distal (left) | 43 (41.3) | 16 (40) | 59 (41) | |

| KRAS | .91b | |||

| Missing | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Mutant | 33 (32.4) | 13 (33.3) | 46 (32.6) | |

| Wild type | 69 (67.6) | 26 (66.4) | 95 (67.4) | |

| KRAS Mutant Subtypes | .50b | |||

| Gly12Asp (GGT>GAT) | 13 (12.3) | 4 (10.0) | 17 (11.7) | |

| Gly12Val (GGT>GTT) | 5 (4.7) | 2 (5.0) | 7 (4.8) | |

| Gly13Asp (GGC>GAC) | 6 (5.6) | 5 (12.5) | 11 (7.5) | |

| Other KRAS mutant | 9 (8.5) | 2 (5.0) | 11 (7.5) | |

| BRAF | .87b | |||

| Missing | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| Mutant | 20 (19.8) | 8 (21.1) | 28 (21.1) | |

| Wild type | 81 (80.2) | 30 (78.9) | 111 (79.9) | |

| BRAF Wild and KRAS Wild | .99b | |||

| Missing | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| No | 53 (52.5) | 20 (52.6) | 73 (52.5) | |

| Yes | 48 (47.5) | 18 (47.4) | 66 (47.5) | |

| dMMR or pMMR | .71b | |||

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| pMMR | 85 (80.2) | 30 (78.9) | 115 (81) | |

| dMMR | 19 (17.9) | 8 (21.1) | 27 (19) |

Data are presented as n (%), except where otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: BRAF = v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1; dMMR = deficient mismatch repair; FOLFIRI = Irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin; KRAS = Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; pMMR = proficient mismatch repair.

Kruskal Wallis test.

χ2 test.

Fisher exact test.

Site of primary was defined as: proximal (right)—cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, and transverse colon; and distal (left)—splenic flexure, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. Patients having tumors in both the left and right colon were classified as missing (2 patients) for analyses.

Chemotherapy

Patients receiving FOLFIRI with cetuximab were able to complete a similar number of cycles of therapy as those receiving FOLFIRI (9.7 vs. 10.6 cycles; P = .19). However, 10% fewer patients receiving FOLFIRI with cetuximab completed all 12 cycles (67.5% vs. 77.4%; P = .29). The rate of patients discontinuing treatment with the cetuximab regimen due to adverse events or patient refusal was nearly twice the rate of those treated with FOLFIRI alone (30% vs. 16%; P = .054).

When analyzed according to planned dose levels, median 5-FU dose intensity was consistent over time for both treatment arms (Table 2). By the 12th cycle, the median irinotecan dose administered for patients not treated with cetuximab was 87% (25th percentile = 73%; 75th percentile = 100%) and 98% (25th percentile = 81%; 75th percentile = 100%) for cetuximab-treated patients. Sixteen (15%) of the patients initially randomized to FOLFIRI and 17 (43%) of those initially randomized to FOLFIRI with cetuximab received oxaliplatin at some point of their adjuvant treatment, because of study modifications described previously.

Table 2.

Chemotherapy Dose Intensity, According to Treatment Arm

| Irinotecan | 5-FU Push | 5-FU Infusion | Cetuximab | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | n | Median % Planned Dose (25%–75%) |

n | Median % Planned Dose (25% –75%) |

n | Median % Planned Dose (25% –75%) |

n | Median % Planned Dose (25% –75%) |

| FOLFIRI | ||||||||

| 1 | 105 | 100.0 (99.3–100.6) | 106 | 100.0 (99.8–100.5) | 106 | 100.0 (99.9–100.5) | NA | NA |

| 2 | 99 | 99.9 (98.7–100.8) | 103 | 100.0 (99.5–100.9) | 102 | 100.0 (99.0–100.9) | NA | NA |

| 3 | 94 | 99.7 (84.8–100.6) | 99 | 100.0 (99.4–100.9) | 98 | 100.0 (98.8–100.9) | NA | NA |

| 4 | 91 | 99.3 (83.5–100.8) | 98 | 100.1 (99.5–101.2) | 97 | 100.0 (98.6–101.3) | NA | NA |

| 5 | 87 | 99.1 (83.3–100.9) | 97 | 100.4 (99.5–101.3) | 97 | 100.0 (97.4–101.2) | NA | NA |

| 6 | 86 | 99.2 (83.3–101.1) | 95 | 100.5 (99.8–102.1) | 95 | 100.0 (96.0–101.6) | NA | NA |

| 7 | 83 | 99.2 (83.3–100.8) | 93 | 100.5 (100.0–102.2) | 93 | 100.0 (89.5–101.4) | NA | NA |

| 8 | 81 | 99.2 (83.3–101.0) | 92 | 100.6 (100.0–102.8) | 92 | 100.2 (93.0–101.9) | NA | NA |

| 9 | 75 | 99.1 (81.6–101.4) | 88 | 100.7 (100.0–103.7) | 88 | 100.3 (86.8–102.3) | NA | NA |

| 10 | 73 | 92.1 (81.4–100.4) | 86 | 100.9 (100.0–103.7) | 86 | 100.1 (83.8–102.3) | NA | NA |

| 11 | 70 | 88.2 (75.2–100.2) | 84 | 100.8 (100.0–103.7) | 84 | 100.0 (82.0–101.8) | NA | NA |

| 12 | 68 | 87.2 (73.2–100.3) | 82 | 101.2 (100.0–103.8) | 81 | 100.0 (80.9–102.3) | NA | NA |

| FOLFIRI With Cetuximab | ||||||||

| 1 | 39 | 99.9 (98.4–100.1) | 40 | 100.0 (99.2–100.6) | 40 | 100.0 (97.4–100.0) | 40 | 99.2 (83.9–100.4) |

| 2 | 36 | 99.6 (97.6–100.3) | 38 | 99.9 (98.7–100.5) | 38 | 99.5 (97.4–100.0) | 29 | 99.1 (97.8–100.0) |

| 3 | 29 | 99.5 (96.7–99.9) | 34 | 99.7 (98.4–100.0) | 34 | 99.5 (97.3–100.0) | 29 | 98.9 (71.9–100.0) |

| 4 | 29 | 99.5 (97.6–100.0) | 32 | 99.7 (98.5–100.5) | 32 | 99.6 (97.8–100.1) | 27 | 99.1 (80.4–100.0) |

| 5 | 26 | 99.7 (96.7–100.5) | 31 | 100.0 (98.4–100.6) | 31 | 99.6 (97.5–100.5) | 26 | 98.5 (71.9–100.1) |

| 6 | 24 | 99.4 (90.2–100.1) | 31 | 99.8 (98.4–100.5) | 31 | 99.5 (97.5–100.1) | 25 | 98.5 (50.3–100.0) |

| 7 | 23 | 99.5 (84.7–100.1) | 31 | 100.0 (98.3–100.6) | 31 | 99.0 (96.4–100.1) | 24 | 99.0 (77.0–100.3) |

| 8 | 23 | 99.5 (81.2–100.1) | 31 | 100.0 (98.3–100.6) | 31 | 98.7 (95.1–100.5) | 24 | 99.6 (87.2–101.1) |

| 9 | 20 | 98.6 (75.0–100.0) | 30 | 100.0 (98.3–101.6) | 30 | 99.1 (95.1–100.5) | 23 | 99.1 (79.6–100.5) |

| 10 | 18 | 98.6 (81.2–100.1) | 28 | 100.0 (98.4–101.2) | 28 | 99.3 (95.7–101.1) | 21 | 99.1 (96.2–100.0) |

| 11 | 15 | 98.4 (80.6–100.1) | 29 | 100.0 (98.3–101.1) | 29 | 98.7 (95.1–101.0) | 22 | 99.3 (79.6–100.5) |

| 12 | 12 | 98.0 (80.9–100.1) | 27 | 100.0 (97.9–101.6) | 27 | 98.7 (95.1–101.2) | 20 | 99.5 (96.4–100.6) |

n represents the number of patients receiving the agent for a given cycle.

Abbreviations: FOLFIRI = irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin; 5-FU = 5-fluorouracil.

Adverse Effects

Grade 3, 4, and 5 adverse events regardless of attribution were recorded for this study (Table 3). Adverse events from all cycles of treatment are included, irrespective of oxaliplatin administration replacing irinotecan and to accurately reflect reasons for ending active treatment (ie, patient refusal, adverse events). Compared with patients receiving chemotherapy alone, Grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported more frequently among patients treated with cetuximab (53% vs. 68%; P = .11). Cetuximab-treated patients reported significantly more nonhematologic events (46% vs. 68%; P = .02). Grade ≥ 3 paresthesia, rash/acne, and infarctions were more common with FOLFIRI and cetuximab. One death occurred during treatment in the FOLFIRI arm. A 72-year-old Caucasian man died suddenly 10 days after starting his 8th cycle due to a suspected pulmonary embolism.

Table 3.

Adverse Events, According to Treatment Arm

| Adverse Eventa | FOLFIRI (n = 106) |

FOLFIRI With Cetuximab (n = 40) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Grade ≥3 | 56 (52.8%) | 27 (67.5%) | .11b |

| Grade ≥4 | 22 (20.8%) | 6 (15.0%) | .43b |

| Grade ≥3 hematologic | 15 (14.2%) | 3 (7.5%) | .40c |

| Grade ≥4 hematologic | 15 (14.2%) | 3 (7.5%) | .40c |

| Grade ≥3 nonhematologic | 49 (46.2%) | 27 (67.5%) | .02b |

| Grade ≥4 nonhematologic | 8 (7.5%) | 4 (10.0%) | .74c |

| Allergy/Immunology | |||

| Hypersensitivity | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.5%) | .27c |

| Cardiovascular | |||

| Thrombosis | 5 (4.7%) | 2 (5.0%) | >.99c |

| Infarction | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (7.5%) | .02c |

| Constitutional Symptoms | |||

| Fatigue | 3 (2.8%) | 1 (2.5%) | >.99c |

| Dermatology/Skin | |||

| Acne/rash | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (27.5%) | <.01c |

| Gastrointestinal | |||

| Diarrhea | 15 (14.2%) | 6 (15.0%) | .90b |

| Nausea | 10 (9.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | .06c |

| Vomiting | 8 (7.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | .11c |

| Stomatitis/mucositis | 3 (2.8%) | 3 (7.5%) | .35c |

| Anorexia | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (2.5%) | .47c |

| Hematologic | |||

| Neutropenia | 15 (14.2%) | 3 (7.5%) | .40c |

| Infection | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (2.5%) | >.99c |

| Infection | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (5.0%) | .18c |

| Metabolic/Laboratory | |||

| Hyperglycemia | 8 (7.5%) | 1 (2.5%) | .44c |

| Neurology | |||

| Paresthesias | 2 (1.9%) | 5 (12.5%) | .02c |

| Pulmonary | |||

| Dyspnea | 3 (2.8%) | 3 (7.5%) | .35c |

| Pneumonitis | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (2.5%) | .47c |

Adverse events are Grade ≥3 unless otherwise specified. Infection includes all infections except pneumonia and febrile neutropenia. Peripheral neuropathy is included in paresthesias. Stomatitis/mucositis includes oral cavity, small bowel, and pharynx. Acne/rash includes acne NOS, rash/desquamation, rash, skin irritation, and rash acneiform.

Abbreviations: FOLFIRI = irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin; mFOLFOX6 = modified regimen 6 of oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin; NOS = not otherwise specified.

National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3. Calculated as the maximum severity over all cycles of treatment and includes mFOLFOX6 treatment cycles.

χ2 test.

Fisher exact test (2-sided).

Disease-Free Survival and Secondary Outcomes

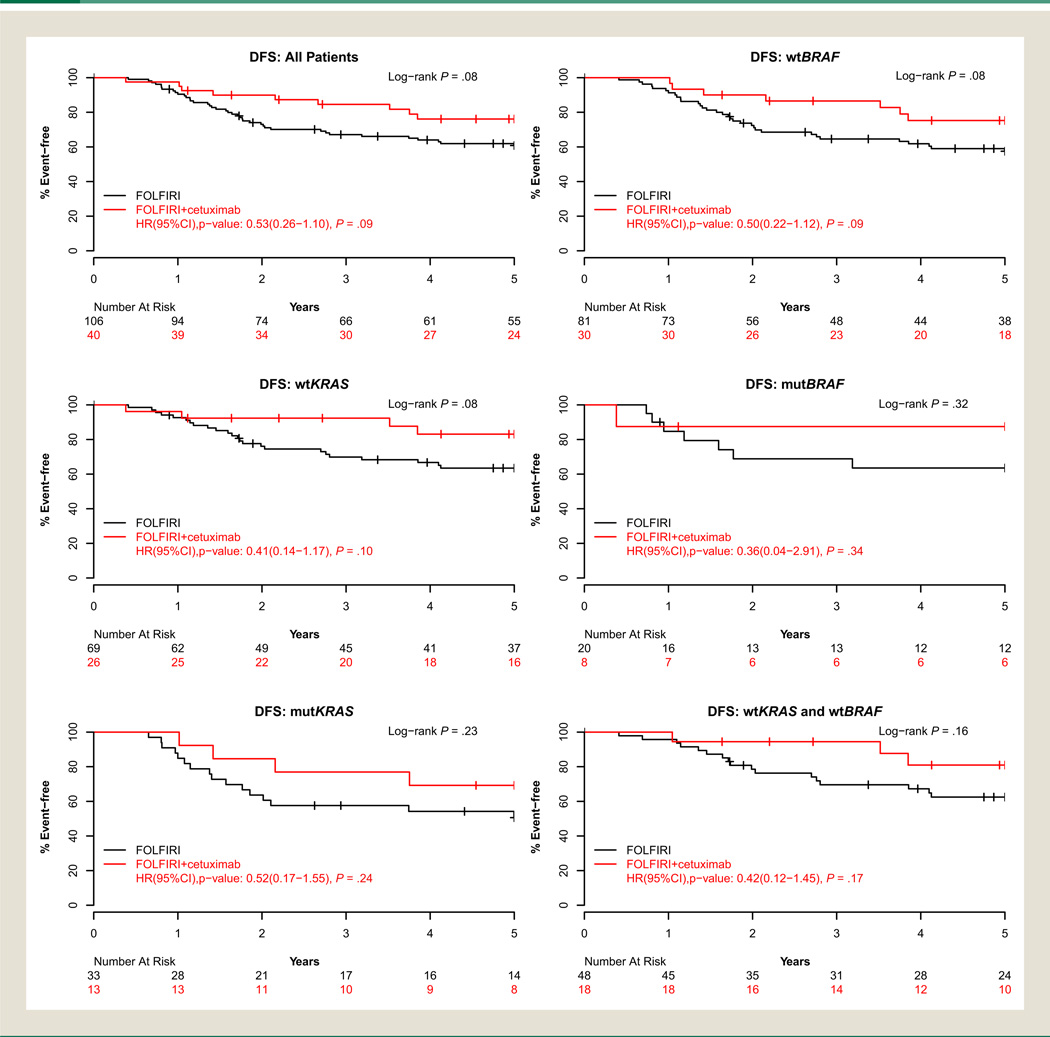

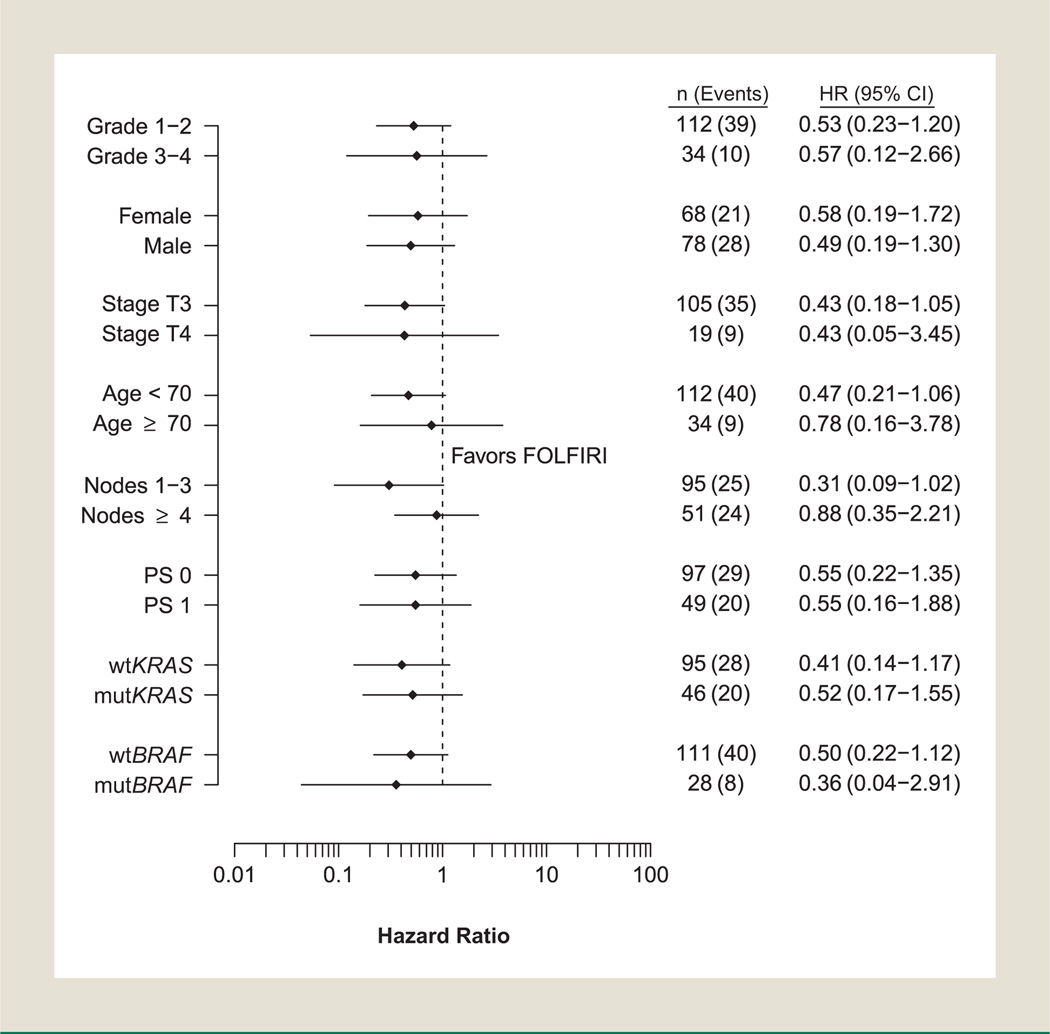

At the time of this analysis, 25% of patients had died with a median follow-up of 5.95 years (range, 0.1–7.0 years) for living patients. Overall, 49 of the 146 patients (34%) had developed recurrent disease. Consistent trends were observed for disease outcomes, favoring the cetuximab-containing arm (Fig. 1). Cetuximab improved TTR with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.3–1.2; P = .12) and 3-year TTR estimates of 87% (95% CI, 77%–98%) versus 69% (95% CI, 60%–78%) for FOL-FIRI alone. Similar findings were observed in the time-varying Cox model sensitivity analysis for receipt of crossover oxaliplatin (TTR HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.28–1.34; P = .22). Improved DFS and OS were also observed with cetuximab, (DFS HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.3–1.1; P = .09) and 3-year event-free estimates of 85% (95% CI, 74%–97%) versus 67% (95% CI, 59%–77%) for FOLFIRI alone (Fig. 1). Treatment with cetuximab showed a trend toward improved OS (OS HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.2–1.2; P = .10) with 3-year survival estimates of 90% (95% CI, 81%–100%) versus 85% (95% CI, 78%–92%) for FOLFIRI alone (Table 4). The DFS and OS findings were similar in the time-varying Cox model sensitivity analysis. A nonsignificant trend toward improved TTR, DFS, and OS (.05 < P < .10) was observed among patients younger than 70 years treated with cetuximab, and similar trends were observed in DFS and TTR within wtKRAS patients. Cetuximab-treated wtBRAF patients experienced a nonsignificant trend toward improved DFS (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.2–1.1; P = .09). Sample size limitations precluded meaningful results from multivariate analysis. Figure 2 shows a Forest plot of the univariate associations of each subgroup for DFS. Cetuximab showed favorable DFS compared with patients treated with FOLFIRI alone with no significant interaction observed between of any baseline characteristic and treatment, and in particular, regardless of KRAS status.

Figure 1. Disease-Free Survival, According to Biomarker-Defined Patient Grouping and Treatment Group.

Abbreviations: DFS = disease-free survival; FOLFIRI = irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin; HR = hazard ratio; mutBRAF = mutated v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1; mutKRAS = mutated Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; wtBRAF = wild type v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1; wtKRAS = wild type Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog.

Table 4.

Time to Recurrence, DFS, and OS, for Treatment Arms Within Patient Groups Defined According to Biomarkers and Age Group

| Event | FOLFIRI | FOLFIRI With Cetuximab | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (Events) | 3-Year % (95% CI) | 5-Year % (95% CI) | n (Events) | 3-Year % (95% CI) | 5-Year % (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a | P (Wald) | |

| All | ||||||||

| Disease-free survival | 106 (40) | 67.1 (58.6–76.8) | 60.8 (52.0–71.1) | 40 (9) | 84.6 (73.9–96.7) | 76.1 (63.6–91.1) | 0.53 (0.26–1.10) | .09 |

| Overall survival | 106 (31) | 84.6 (78.0–91.8) | 73.7 (65.6–82.7) | 40 (5) | 89.7 (80.6–99.8) | 86.9 (76.8–98.3) | 0.45 (0.17–1.16) | .10 |

| Time to recurrence | 106 (35) | 68.6 (60.2–78.3) | 65.3 (56.6–75.4) | 40 (8) | 86.7 (76.5–98.3) | 78.1 (65.7–92.8) | 0.54 (0.25–1.17) | .12 |

| wtKRAS | ||||||||

| Disease-free survival | 69 (24) | 69.9 (59.6–81.9) | 63.5 (52.8–76.3) | 26 (4) | 92.3 (82.6–100) | 83.1 (69.2–99.8) | 0.41 (0.14–1.17) | .10 |

| Overall survival | 69 (20) | 85.2 (77.1–94.1) | 76.0 (66.4–87.0) | 26 (3) | 92.0 (82.0–100) | 87.4 (75.0–100) | 0.46 (0.13–1.56) | .21 |

| Time to recurrence | 69 (21) | 72.4 (62.2–84.1) | 67.3 (56.7–79.9) | 26 (3) | 96.0 (88.6–100) | 86.4 (73.1–100) | 0.35 (0.10–1.16) | .09 |

| mutKRAS | ||||||||

| Disease-free survival | 33 (16) | 57.6 (43.0–77.2) | 50.6 (35.9–71.3) | 13 (4) | 76.9 (57.1–100) | 69.2 (48.2–99.5) | 0.52 (0.17–1.55) | .24 |

| Overall survival | 33 (11) | 81.4 (69.0–96.0) | 64.9 (50.2–84.1) | 13 (2) | 84.6 (67.1–100) | 84.6 (67.1–100) | 0.42 (0.09–1.90) | .26 |

| Time to recurrence | 33 (14) | 57.6 (43.0–77.2) | 57.6 (43.0–77.2) | 13 (4) | 76.9 (57.1–100) | 69.2 (48.2–99.5) | 0.60 (0.20–1.82) | .37 |

| wtBRAF | ||||||||

| Disease-free survival | 81 (33) | 64.6 (54.8–76.1) | 57.5 (47.4–69.7) | 30 (7) | 86.5 (75.1–99.7) | 75.3 (60.8–93.1) | 0.50 (0.22–1.12) | .09 |

| Overall survival | 81 (26) | 84.8 (77.2–93.1) | 71.6 (62.2–82.4) | 30 (4) | 89.9 (79.6–100) | 86.1 (74.4–99.8) | 0.43 (0.15–1.24) | .12 |

| Time to recurrence | 81 (28) | 66.5 (56.8–77.9) | 63.4 (53.5–75.3) | 30 (7) | 86.5 (75.1–99.7) | 75.3 (60.8–93.1) | 0.58 (0.25–1.33) | .20 |

| mutBRAF | ||||||||

| Disease-free survival | 20 (7) | 68.8 (50.9–93.0) | 63.5 (45.2–89.2) | 8 (1) | 87.5 (67.3–100) | 87.5 (67.3–100) | 0.36 (0.04–2.91) | .34 |

| Overall survival | 20 (5) | 80.0 (64.3–99.6) | 75.0 (58.2–96.6) | 8 (1) | 85.7 (63.3–100) | 85.7 (63.3–100) | 0.59 (0.07–5.08) | .63 |

| Time to recurrence | 20 (7) | 68.8 (50.9–93.0) | 63.5 (45.2–89.2) | 8 (0) | 100 (100-100) | 100 (100-100) | NA | NA |

| wtBRAF and wtKRAS | ||||||||

| Disease-free survival | 48 (17) | 69.6 (57.4–84.3) | 62.5 (49.8–78.4) | 18 (3) | 94.4 (84.4–100) | 81.0 (63.6–100) | 0.42 (0.12–1.45) | .17 |

| Overall survival | 48 (15) | 87.1 (78.0–97.3) | 75.9 (64.4–89.4) | 18 (2) | 94.4 (84.4–100) | 87.7 (73.0–100) | 0.41 (0.09–1.82) | .24 |

| Time to recurrence | 48 (14) | 73.1 (61.2–87.4) | 68.0 (55.4–83.5) | 18 (3) | 94.4 (84.4–100) | 81.0 (63.6–100) | 0.51 (0.15–1.78) | .29 |

| Age <70 Years | ||||||||

| Disease-free survival | 82 (33) | 63.8 (54.1–75.3) | 58.3 (48.4–70.4) | 30 (7) | 86.5 (75.1–99.7) | 76.2 (62.2–93.3) | 0.47 (0.21–1.06) | .07 |

| Overall survival | 82 (23) | 85.0 (77.6–93.2) | 73.3 (64.2–83.8) | 30 (3) | 93.2 (84.6–100) | 89.6 (79.2–100) | 0.35 (0.10–1.17) | .09 |

| Time to recurrence | 82 (31) | 65.0 (55.3–76.3) | 60.7 (50.8–72.6) | 30 (7) | 86.5 (75.1–99.7) | 76.2 (62.2–93.3) | 0.50 (0.22–1.14) | .10 |

| Age ≥70 Years | ||||||||

| Disease-free survival | 24 (7) | 78.8 (63.8–97.2) | 69.7 (53.2–91.3) | 10 (2) | 80.0 (58.7–100) | 80.0 (58.7–100) | 0.78 (0.16–3.78) | .76 |

| Overall survival | 24 (8) | 83.3 (69.7–99.7) | 74.8 (59.2–94.5) | 10 (2) | 77.8 (54.9–100) | 77.8 (54.9–100) | 0.82 (0.17–3.96) | .81 |

| Time to recurrence | 24 (4) | 82.2 (67.8–99.7) | 82.2 (67.8–99.7) | 10 (1) | 88.9 (70.6–100) | 88.9 (70.6–100) | 0.65 (0.07–5.87) | .70 |

Abbreviations: DFS = disease-free survival; FOLFIRI = irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin.

From an unadjusted Cox model.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of the Univariate Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for DFS. For the Effects of Treatment Within Each Subgroup Values > 1 Favor FOLFIRI Alone. Hazard Ratios are not Adjusted for Other Covariates.

Abbreviations: FOLFIRI = irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin; HR = hazard ratio; mutBRAF = mutated v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1; mutKRAS = mutated Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; OS = overall survival; PS = performance status; wtBRAF = wild type v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1; wtKRAS = wild type Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog.

Discussion

In this small randomized subset of patients with resected stage III colon cancer from clinical trial N0147, the addition of cetuximab to FOLFIRI showed a trend toward improved DFS and OS in all patients irrespective of KRAS or BRAF mutation status (Fig. 2). Our results, although not statistically robust, are similar to previously published data on improved OS with anti-EGFR therapy added to FOLFIRI in wtKRAS tumors from patients with advanced colorectal cancer, but are inconsistent with the lack of benefit seen in mutated (mut) KRAS patients in advanced disease studies.14 It should also be emphasized that treatment was directed at micrometastatic disease, which biology is distinct from established metastatic disease.

In the previous trial PETACC-3, assessing adjuvant FOLFIRI compared with the 2-day infusion of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (LV5FU2) in patients with resected stage III colon cancer, FOLFIRI provided no improvement in DFS.6 In N0147, the 3-year DFS with FOLFIRI was 67.1% (Table 4), greater than that reported in PETACC-3 (56.7%). When restricted to wtKRAS patients, the 3-year DFS was 69.9% for FOLFIRI alone, less than that obtained with FOLFOX (74.6%) in the primary analysis population.4 As such, FOLFIRI continues to be an inferior form of adjuvant therapy for patients with resected stage III colon cancer.

Varying levels of benefit have been reported in randomized trials for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer that compared a chemotherapy regimen of a fluouropyrimidine combined with either irinotecan or oxaliplatin, with or without an EGFR inhibitor. The variation in outcomes has led to speculation that EGFR inhibitors might provide differing levels of benefit depending on whether they are combined with irinotecan or oxaliplatin. It is conceivable that a difference of this type could have led to the observed results in N0147. However, a published metaanalysis concluded that no such difference exists, at least in trials for metastatic colorectal cancer.14 If any difference exists it is more likely to be related to the fluouropyrimidine used (ie, 5-FU vs. capecitabine).

The mutation status of KRAS has more directly been associated with the potential for benefit from an EGFR inhibitor. Updated analysis from the CRYSTAL trial demonstrated that adding cetuximab to FOLFIRI improved OS in wtKRAS metastatic colorectal patients, whereas mutKRAS patients experienced no benefit in progression-free survival (PFS) or OS.15 Previous studies had suggested that varying clinical efficacy depends on the specific mutation in the KRAS gene. In a pooled data set of 579 patients with chemotherapy-refractory colorectal cancer from multiple clinical trials, a favorable interaction between Gly13Asp (G13D) mutKRAS status and cetuximab treatment for OS (HR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.14–0.67; P = .003) was observed.16 In addition, they found sensitivity of G13D mutants, versus insensitivity of G12V, to cetuximab in vitro and in mouse models. More recently, Tejpar and others observed sensitivity to cetuximab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors had a G13D mutation, with a trend in improvement in PFS from 6 to 7.4 months (P = .039), tumor response from 22.0% to 40.5% (P = .042), and OS from 14.7 to 15.4 months (P = .68).17 More recent studies appear to discredit this observation. In our study, it is unclear whether a subset of patients with mutKRAS tumors treated with cetuximab and FOLFIRI showed an improvement in DFS due to the presence of a G13D mutation, though it is unlikely that this is the case.

Based on a very small number of patients, a trend toward improved DFS in patients with tumors exhibiting mutBRAF treated with cetuximab plus FOLFIRI (HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.04–2.91; P = .34) was observed. The results of this study are in contrast with previous studies showing reduced sensitivity to cetuximab and shorter PFS in tumors carrying the BRAF V600E mutation compared with wild type.18 This observation might be strictly related to the insufficient sample size because the comparison group for our mutBRAF pool was a very small group (FOLFIRI, n = 20; FOLFIRI with cetuximab, n = 8). Therefore, meaningful conclusions cannot be made from this subgroup analysis, but do not exclude the possibility that some mutBRAF tumors might potentially benefit from the addition of cetuximab for reasons that are not clearly understood.

Several limitations are to be considered regarding this analysis. First, the sample size was small, with some patients not randomly assigned to receive 1 of the 2 treatments, because cetuximab was included as a modification after the trial had been open for 1 year. Second, the treatment arms were discontinued early and before generating any definitive conclusions. Nevertheless, the trends observed in this study were consistent across all time-to-event analyses, suggesting that adding cetuximab to FOLFIRI might benefit these patients, although in a nonsignificant manner. Although the cetuximab-containing arm experienced higher rates of cardiovascular infarctions, rash, neuropathy, and nausea and vomiting were not increased. The toxicities with the addition of cetuximab did not limit the dose administration of irinotecan and infusion of 5-FU. The results of this study might also have been affected by patients discontinuing early, after FOLFIRI was found to be inferior to FOLFOX. Other potential explanations include a more favorable mechanistic interaction between cetuximab and FOLFIRI compared with FOLFOX, or a subgroup effect.

In comparison with the 3-year DFS reported13 for mFOLFOX6 (72%; 95% CI, 69%–75%), 3-year DFS was less for the FOLFIRI-alone arm (67%; 95% CI, 59%–77%). When restricting the patient cohort used to assess the primary end point of the study11 (ie, mFOLFOX6 with or without cetuximab), yet enrolled during the same time period as those in the FOLFIRI with or without cetuximab arms, the 3-year DFS rate observed for the 132 patients treated with mFOLFOX6 and the 52 patients treated with mFOLFOX6 with cetuximab were 75% (95% CI, 68%–83%) and 74% (95% CI, 60%–86%), respectively. This is consistent with previous data showing reduced, if any, benefit from the addition of irinotecan to adjuvant therapy.6,7

Conclusion

In summary, nonsignificant trends for improved DFS and OS were found for the addition of cetuximab to FOLFIRI in stage III colon cancer patients irrespective of KRAS or BRAF status in this small randomized comparison study. Importantly, adjuvant FOLFIRI resulted in a 3-year DFS less than that expected for FOLFOX. Recognizing the limitations of this analysis, the results remain provocative and suggest that possibility that cetuximab might differentially interact with irinotecan compared with oxaliplatin. Nevertheless, FOLFOX without the addition of a biologic agent remains the standard of care at this time for adjuvant therapy in resected stage III colon cancer. Our results should be considered as hypothesis-generating and not in any manner practice-changing.

Clinical Practice Points.

A variety of approaches have been explored to improve on the current standards of adjuvant therapy for resected stage III colon cancer, consisting of a fluoropyrimidine (capecitabine, 5-FU) and oxaliplatin.

Recent trials have evaluated the possible benefit of adding targeted agent, such as cetuximab or bevacizumab.

The randomized phase III trial N0147 included FOLFIRI with and without cetuximab in early versions of the trial, in addition to FOLFOX with and without cetuximab.

The combination of FOLFIRI with cetuximab showed apparent benefit in a small number of patients receiving this combination.

However, considering the small number of patients these results should not be used as evidence to support the adjuvant use of FOLFIRI with cetuximab.

Additional research is needed to establish any possible benefit and to define specific patients who might benefit.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as a collaborative trial of the NCCTG, Mayo Clinic, and was supported in part by Public Health Service grants CA-25224, CA-37404, CA-35103, CA-35113, CA-35272, CA-114740, CA-32102, CA-14028, CA49957, CA21115, CA31946, CA12027, CA37377 from the NCI, Department of Health and Human Services. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group participation in this trial was supported by funding received from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (Grant #021039 and #015469) and the US NCI (Grant #CA077202). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NCI or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have stated that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, et al. Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2040–2048. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:663–671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Nair S, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1383–1393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saltz LB, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Irinotecan fluorouracil plus leucovorin is not superior to fluorouracil plus leucovorin alone as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer: results of CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3456–3461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Cutsem E, Labianca R, Bodoky G, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing biweekly infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin alone or with irinotecan in the adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer: PETACC-3. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3117–3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ychou M, Raoul JL, Douillard JY, et al. A phase III randomised trial of LV5FU2 + irinotecan versus LV5FU2 alone in adjuvant high-risk colon cancer (FNCLCC Accord02/FFCD9802) Ann Oncol. 2009;20:674–680. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [Accessed: March 1, 2012];National Cancer Institute: Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0, DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS. Available at: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf.

- 9.Cross J. DxS Ltd. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:463–467. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation for incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Roy Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. [Accessed: March 1, 2012]. R Development Core Team (2011) http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vale CL, Tierney JF, Fisher D, et al. Does anti-EGFR therapy improve outcome in advanced colorectal cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Lang I, et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2011–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Roock W, Jonker DJ, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. Association of KRAS p.G13D mutation with outcome in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. JAMA. 2010;304:1812–1820. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tejpar S, Celik I, Schlichting M, et al. Association of KRAS G13D tumor mutations with outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy with or without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3570–3577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5705–5712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]