Abstract

We report the synthesis and anticancer photodynamic properties of two new decacationic fullerene (LC14) and red light-harvesting antenna-fullerene conjugated monoadduct (LC15) derivatives. The antenna of LC15 was attached covalently to C60> with distance of only <3.0 Ǻ to facilitate ultrafast intramolecular photoinduced-electron-transfer (for type-I photochemistry) and photon absorption at longer wavelengths. Because LC15 was hydrophobic we compared formulation in CremophorEL micelles with direct dilution from dimethylacetamide. LC14 produced more 1O2 than LC15, while LC15 produced much more HO· than LC14 as measured by specific fluorescent probes. When delivered by DMA, LC14 killed more HeLa cells than LC15 when excited by UVA light, while LC15 killed more cells when excited by white light consistent with the antenna effect. However LC15 was more effective than LC14 when delivered by micelles regardless of the excitation light. Micellar delivery produced earlier apoptosis and damage to the endoplasmic reticulum as well as to lysosomes and mitochondria.

Keywords: photodynamic therapy, decacationic fullerene monoadducts, nanomedicine, structure-function relationship, reactive oxygen species, light absorbing antenna, apoptosis, micelles

Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a rapidly developing approach for cancer treatment that utilizes the combination of a nontoxic dye, termed a photosensitizer (PS), and harmless visible or near-infrared (NIR) light to kill cancer cells and destroy tumors by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen, superoxide and hydroxyl radical1. PDT has the advantage of dual selectivity such that the PS can be targeted to its destination cells or tissues and the illumination can be spatially directed to the lesion. The ROS produced during PDT are effective in killing both the malignant and the normal cells via necrosis, apoptosis or autophagy, depending on the cell type, structure of the PS, and the light parameters chosen2, 3.

[60]Fullerene (C60)4 is composed of 60 carbon atoms arranged in a soccer ball-shaped structure with condensed aromatic rings giving an extended π-conjugation of degenerated molecular orbitals and unique low-laying excited triplet energy state. Generation efficiency of the excited triplet energy state (3C60*) was found to be nearly quantitative via intersystem crossing from its photoexcited singlet state (1C60*)5. Alternation of this photophysical property is possible upon molecular functionalization to various fullerenyl derivatives. However, synthesis of C60 monoadducts (C60>) involves change of the molecular cage structure by only one olefin bond that leads to the retention of a half -cage sphere identical to that of C60. Accordingly, the generation efficiency of triplet 3(C60>)* is nearly identical to that of 3C60*6, 7. By a similar mechanism to the tetrapyrrole PS used for photodynamic therapy (PDT), illumination of solubilized C60 and its monoadduct derivatives in the presence of oxygen leads to the generation of singlet oxygen (1O2) via energy-transfer from the excited triplet state of C60 or C60> to O2, giving the photocytotoxic effect8. In the presence of electron-rich small molecules or electron-donating chromophores, an additional electron-transfer mechanism can be involved in the photoexcited state that leads to the formation of anionic radical (C60>)− · and superoxide radical (O2− ·), as the product of subsequent electron-transfer from (C60>)− · intermediate to O2. This photophysical process is solvent-dependent. It is favorable in polar solvents over the competitive energy-transfer process under the same conditions. For example, it was demonstrated9 that illumination on fullerenes in a hydrophilic medium containing reducing agents (such as NADH, found in cells) generated the reduced oxygen species, O2− · and hydroxyl radical (HO·), while in nonpolar solvents; singlet oxygen was the main product. These different pathways are analogous to the type-II and type-I photochemical mechanisms frequently discussed in PDT with tetrapyrroles8. In recent years, there has been much interest in studying the possible biological activities of fullerenes (and other nanostructures produced in the nanotechnology revolution) with the aim of using them in the field of medicine10, 11. Fullerene derivatives have been used to carry out in vitro PDT, leading to cleavage of DNA strands12, photoinactivation of pathogens such as gram-positive, gram-negative bacteria and yeast13, 14, mutagenicity in Salmonella species15, and photo-induced killing of mammalian cells in tissue culture16.

A disadvantage when dealing with unmodified fullerenes is their insolubility in biologically compatible solvents, limiting their use in biological applications. Therefore, fullerenes have to be chemically modified or functionalized by the introduction of addends in order to achieve aqueous solubility [6–8]. The molecular characteristics of the PS such as charge, lipophilicity and asymmetry govern the localization and uptake of the compounds by various cell types, and also determine the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and localization of the PS at the target site17. This route has been used to prepare functionalized fullerenes containing a variety of positively charged substituents, groups to impart water solubility, and groups that generally vary in hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity. Fullerenes have been employed as PS to test PDT activity in vitro against hepatoma cells18, HeLa (human cervical cancer cells)19 and in vivo against a mouse model of abdominal dissemination of colon adenocarcinoma20. There has also been a report of fullerene-mediated PDT resulting in cures in a murine subcutaneous tumor model21.

A number of functionalized fullerenes have shown high PDT efficacy against the targeted cell lines. The reasons for the high PDT efficacy of fullerenes include the following: 1) the balance of physicochemical characteristics, such as lipophilicity and cationic charge, ensure that these compounds are efficiently taken up by the target cells and subsequently localize in sensitive intracellular compartments, such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER); 2) the tendency to generate hydroxyl radicals may be more efficient than tetrapyrrole PS that typically generate singlet oxygen22; 3) the exceptional photostability of fullerenes demonstrate that they are resistant to photobleaching – a disadvantage that limits the activity of other PS23.

Many hydrophobic molecules, such as the fullerenes described herein, are poorly soluble in biological media. Cell uptake will be optimum if the chemical/solubility properties of the PS can be optimized by choice of an appropriate delivery vehicle. The formation of molecular aggregates can diminish uptake, reduce ROS generation (due to rapid nonradiative deactivation of the photoexcited PS), and hence lower the PDT activity24. For these reasons, a Cremophor EL (CrEL; polyoxyethylene glycerol triricinoleate) micellar preparation was also studied as a delivery vehicle for the compounds.

In this study, we synthesized two novel analogue functionalized decacationic fullerene derivatives with a well-defined number of cationic charges per C60 with and without a light absorbing electron-donating antenna to shift the absorption spectrum further into the red region of the spectrum. A major challenge in PDT is the limited tissue penetration due to the light absorption and scattering by biological tissues25, 26. PS molecules which can only be excited by short wavelength light (UV and blue light) are usually unfavorable in cancer therapy, especially for solid tumor treatment due to their extremely low tissue penetration depth. We tried to overcome this challenge, through creating a red shift in the spectrum, where an increase in the tissue penetration depth can be achieved. We compared the anti-cancer PDT activity of these fullerenes and their encapsulated CrEL micellar forms.

Materials and Methods

Design and Synthesis of Functionalized Fullerenes

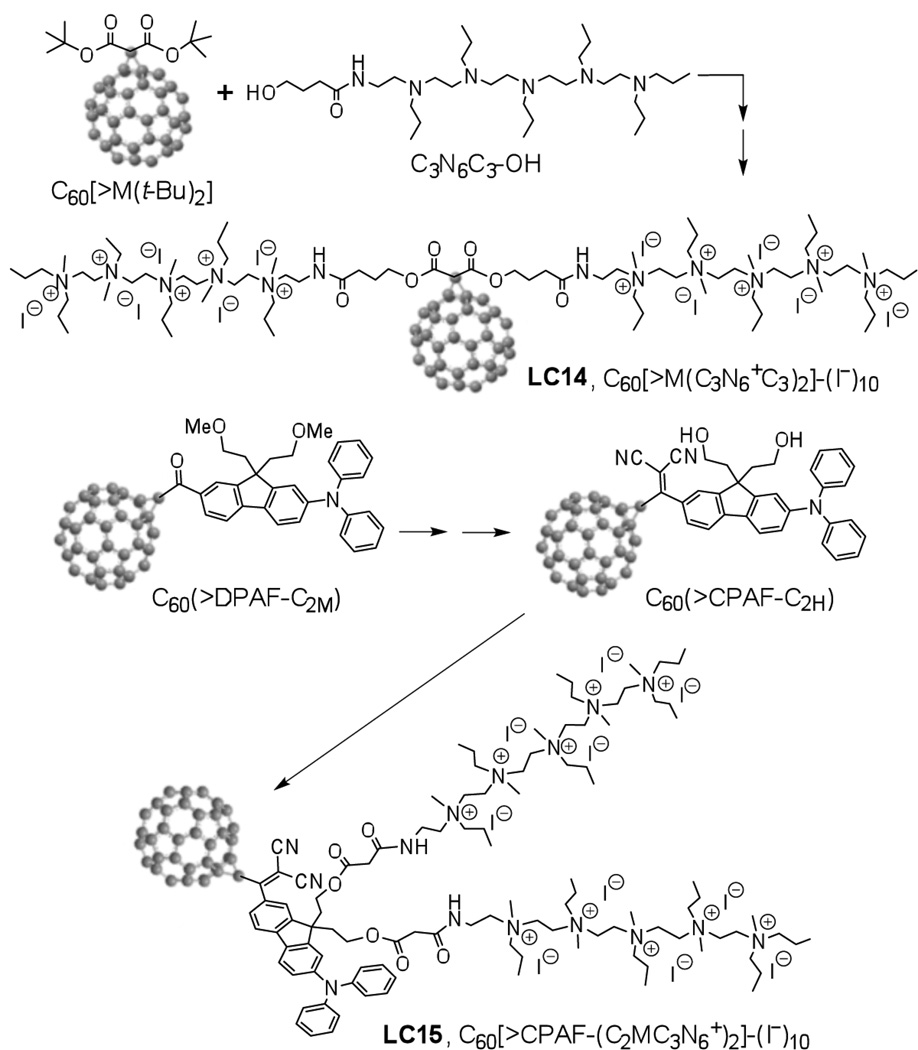

There are two unique structural features incorporated in the design of new decacationic diphenylaminofluorenyl methano[60]fullerene C60[>CPAF-(C2MC3N6+)2]-(I−)10 (LC15, Scheme 1): (1) a well-defined water-soluble pentacationic N,N’,N,N,N,N-hexapropyl-hexa(aminoethyl)amine arm moiety C3N6+ in a form of quaternary methyl ammonium iodide salts for enhancing the targeting ability of the PS to human cervical HeLa cancer cells and providing a source of multiple (ten) electrons, via photoinduced oxidation of iodide (I−), to type-I photochemistry; (2) a red-light harvesting chromophore antenna for increasing photo-absorption at long visible wavelengths during 1γ-PDT and enabling photoinduced electron-transfer mechanism to C60> acceptor. The possibility to achieve a type-I photomechanism in the solution of C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2]-(I−)10 (LC14) will require photoinduced electron-transfer from iodide anions to the fullerene cage moiety in quasi-intramolecular processes to be carried out at either 1(C60>)* or 3(C60>)* excited states, leading to the formation of anionic methanofullerenyl radical (C60>)− · as a precursor to the generation of O2− ·. In the presence of covalently bound e− -donor antenna, such as highly fluorescent CPAF chromophore of LC15, either intramolecular energy- or electron-transfer from photoexcited 1(CPAF)* to C60> occurs in an ultrafast time scale of few hundred femtoseconds27. Therefore, attachment of water-soluble pentacationic C3N6+ arm moieties to C60-CPAF conjugates leading to the formation of LC15 could lead to a novel class of tunable photosensitizers (TPS) to switch between type-I (the production of O2− ·/HO·) and type-II (the production of 1O2) photomechanism using a single nano-PDT agent. Type-I photochemistry is especially desirable in hypoxic tissues such as tumor microenvironment or when PDT consumes most of the tissue O228, 29.

Preparation of Micelles

The reversed-phase evaporation method was used to encapsulate fullerenes into micelles23. A CrEL micellar suspension (100 mg/ml) was prepared by mixing 200 µg of fullerene with 500 µl of CrEL solution in dry tetrahydrofuran (THF). An additional 2.0 ml of THF was added, and the mixture was stirred until an isotropic single-phase solution was obtained. The final CrEL/fullerene ratio was 250:1. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation at room temperature for 60 min. The resulting dry film was completely dissolved in 1.0 ml of sterile PBS in a sonication bath for 20 min. The micellar suspension was filtered through a 0.22 µm mixed-cellulose-ester (MCE) filter under sterile conditions to remove unloaded fullerene, since the PS that is not entrapped within the micelles undergoes aggregation and does not pass through these filters. Then the encapsulation efficiency and the concentration were determined by UV–vis spectroscopy. Stock concentrations of micellar PS were approximately 500 µM. LC14 and LC15 were diluted directly from DMA into the medium, and the same compounds encapsulated into micelles were called LC14 M and LC15 M, respectively.

Characterization of Micelles

The shape and form of micelles were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) recorded on a Philips EM400 transmission electron microscope. In the TEM preparation, the sample (20 µg) was dissolved in dry DMA under ultrasonication for a period of ~5.0 min, giving a master solution in a concentration of 2.0 mM. A portion of this solution was then diluted by H2O to pre-determined concentrations of 1.0, 10, and 100 µM for measurements. The sample solutions of LC-14 and LC-15 without or with CrEL (in a weight ratio of 1:1, 1:10, or 1:250) were deposited and coated on carbon-copper film grids in a 200-mesh size. It was followed by the freeze-dry technique under vacuum to retain to the micelle vesicle shape on the grid for the subsequent topography investigation of molecularly assembled structures as TEM images.

The particle size, size distribution and long-term stability (up to 30 days) of micelles in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were measured using Zetasizer (Nano ZS, Malvern). The short-term longitudinal stability of micelles in serum-containing PBS was evaluated by monitoring the photosensitizer absorbance. Briefly, micelles were suspended in 10% fetal bovine serum at equimolar concentrations. At specific time points, samples were collected and subjected to centrifugation at 2000 rcf for 2 min (Micro7, Fisher Scientific). The absorbance spectra of the supernatants were monitored using UV-vis spectrophotometer (Evolution 300, Thermo Scientific). Each longitudinal micellar absorbance value (λ = 323 nm) was normalized with its initial absorbance (λ = 323 nm) at t = 0. Free form LC14 and LC15 were used as controls in serum stability study.

Light Sources

Two different light sources were used for illumination of cells. One was a white light source (Lumicare, Newport Beach, CA) fitted with a light guide containing a bandpass filter (400–700 nm) adjusted to give a uniform spot of 4 cm in diameter with an irradiance of 150 mW/cm2 as measured with a power meter (Model DMM 199 with 201 Standard head, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA). The second source was an ultraviolet (Woods) exam lamp, which was used for delivering UVA radiation (Model UV 501, Burton Medical, Chatsworth, CA). Emission spectrum measurement of this lamp by a spectroradiometer (SPR-01; Luzchem Research, Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada) showed a peak emission at 365 nm. The irradiance was adjusted by changing the distance between the UVA lamp and the irradiated target and measured using a model IL-1700 research radiometer-photometer (International Light, Inc., Newburyport, MA).

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

A human cervical cancer line HeLa was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured in RPMI medium with L-glutamine and NaHCO3 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere in 75 cm2 flasks (Falcon, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation Assay

Cell-free experiments were performed in 96-well plates. PS solutions were diluted to a final concentration of 5.0 µM per well in PBS, and 3’-(4-hydroxyphenyl) fluorescein (HPF) or singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG) (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Bedford, MA) was added to each well at a final concentration of 5.0 µM. Each experimental group contained four wells. All groups were illuminated simultaneously, and light was delivered in sequential doses of 1.0–15 J/cm2. A microplate reader (Spectra Max M5) was used for acquisition of fluorescence signals in the “slow kinetic” mode. When HPF was employed, fluorescence emission at 525 nm was measured upon excitation at 492 nm using a 2.0 nm monochromator band pass for both excitation and emission. In case of SOSG, the corresponding values were 505 nm (excitation) and 525 nm (emission). Increasing fluences (J/cm2) were delivered using white light at 150 mW/cm2 or UVA at an irradiance of 7.0 mW/cm2. Each time after an incremental fluence was delivered, the fluorescence was measured.

Intracellular ROS production following UVA was detected using CM-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen Corporation, USA). ROS production with white light was not detected because white light activated the probe. CM-H2DCFDA was deacetylated by intracellular esterases when crossing the membrane, producing a nonfluorescent dye CM-H2DCF, which quantitatively reacted with ROS inside the cell to produce another highly fluorescent dye CM-DCF. After incubation in culture medium with 5.0 µM PS for 3 h in darkness, HeLa cells were washed once with PBS and then treated with 5.0 µM of CM-H2DCFDA and 4 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen Corporation) in culture medium for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed with PBS once to remove residue dye and then medium was replaced medium L15 (Invitrogen Corporation) before irradiation by UV for 11 min (10 J/cm2). Production of ROS was recorded immediately after irradiation, visualized by confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan). Fluorescence quantification was carried out on fields selected at random throughout the well. Digital images were recorded and the quantification of fluorescence intensity was performed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Sarasota, FL). The fluorescence intensity was calculated by dividing the total integrated optical density by the total number of cells in each field and expressed as relative fluorescence intensity.

Phototoxicity Assay

When HeLa cells reached 80% confluence, they were washed with PBS and harvested with 2.0 ml of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma). Cells were then centrifuged and counted in trypan blue to ensure viability and plated at a density of 5000/well in flat-bottom 96-well plates (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Cells were allowed to attach overnight. On the following day dilutions of the fullerenes were prepared in complete RPMI medium and added to the cells at 5.0 µM final concentration for 3 h incubation. Prior to illumination, the fullerene solution was replaced with a fresh complete medium and subsequently the cells were illuminated by white light (150 mW/cm2, 50–200 J/cm2, 17– 68 min) and UVA radiation (7.0 mW/cm2, 10– 40 J/cm2, 11– 44 min). The white light spot covered 9 wells which were considered as one experimental group. Four groups, the micellar suspension without fullerene (empty micelles), directly diluted fullerene solution, micellar suspension of fullerene were assessed for dark toxicity and for phototoxicity studies. Following PDT treatment the cells were returned to the incubator for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and the cellular viability was determined by Prestoblue assay (PrestoBlue®Cell viability Reagent, Invitrogen). Briefly, 10 µl Prestoblue solution was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Then the fluorescence was determined at 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission by a microplate spectrophotometer (Spectra Max 340 PC). For each sample, the cellular viability was calculated from the data of 4 wells (n = 4) and expressed as a percentage, compared with the untreated cells (100%). Comparison of the mean optical density between the untreated (100%) and treated cells 24 h after illumination allowed the evaluation of the phototoxicity. Each experiment was repeated 3 times.

Apoptosis Assay

The induction of apoptosis by fullerene-mediated PDT was measured by a fluorescence assay using Caspase 3/7 (Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay, Promega, USA). Briefly cells were counted in trypan blue to ensure viability and plated at a density of 5000/well in flat-bottom 96-well plates in 100 µl complete RPMI medium per well. After overnight incubation of cells for attachment, the dilutions of the fullerenes were prepared and added to the wells at 5.0 µM final concentration for 3 h incubation. Prior to illumination the fullerene solution was removed and replaced with fresh medium. Cells were irradiated with white light (150 mW/cm2, 100 J/cm2) or UVA radiation (7.0 mW/cm2, 20 J/cm2), respectively. PDT samples were collected at several time points (1.5, 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, 5.5, 10, 15 and 25 h). 100 µl of Caspase-Glo® 3/7 reagent was added to each well of a white-walled 96-well plate containing both treated and untreated cells in 100 µl of medium. The contents of the wells were gently mixed using a plate shaker at 300–500 rpm for 30 sec and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The fluorescence of each sample was measured (SpectraMax M5). Each experiment was repeated 3 times.

Detection of Subcellular Photodamage by Fluorescent Probe Assay

LC14 and LC15 did not have sufficient fluorescence to be detectable by microscopy, so we could not determine their intracellular localization. However, in order to confirm that LC14, LC15 and their micellar forms were actually taken into cells and produced photodamage to the cells, the fluorescent probes MitoTracker® probes (λex/λem: 490/516 nm) for mitochondria, LysoTracker® Red DND-99 (λex/λem: 577/590 nm) for lysosome, ER-tracker™ dye (λex/λem: 374/430– 640 nm) for endoplasmic reticulum labeling, and NucRed™ live 647 ready probes™ reagent (λex/λem: 638/686 nm) for nuclear labeling (Invitrogen) were used to detect the location of PDT-associated intracellular damage. Cells (5 × 105 per dish) were plated in 35 mm dishes and allowed to attach overnight. The next day 5.0 µM LC14, LC15 and their micellar forms in complete medium were added and incubated for 3 h, respectively. Cells were washed in PBS gently and added fresh RPMI 1640 medium, then illuminated by 100 J/cm2 white light (150 mW/cm2) or 20 J/cm2 UVA radiation (7.0 mW/cm2). 2 hours after illumination, the cells were washed by PBS, and each separate sample was added the aforementioned four fluorescent probes and were incubated for 30 min in complete medium without phenol red at 37 °C. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS, and the intracellular localization of the dye was observed by confocal microscopy (Olympus FV1000). HeLa cells incubated with the four fluorescent probes without receiving PDT (i.e., no test compound or illumination) were used as controls. Images were acquired using FV10-ASW 2.0 viewer (Olympus) software.

Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between two means were assessed for significance by the two-tailed Student’s t-test and a value of P <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Optical Properties and Electron Micrographic Characterization of LC14 and LC15 in Solvent or Micelle

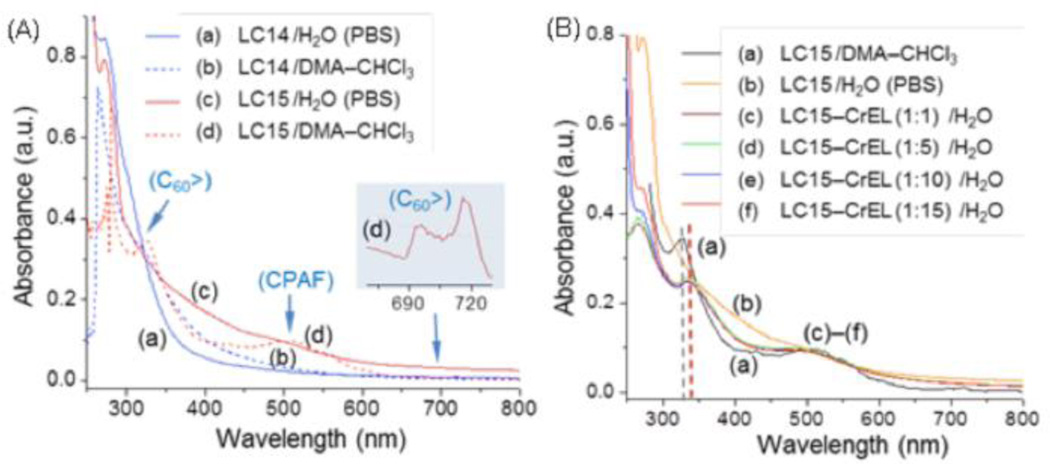

The chemical structure of LC14 and LC15 shown in Fig 1. The LC14 and LC15 are relatively insoluble in water, which prompted use of two approaches toward solubilization in serum containing culture medium to enable cell uptake. The procedures were as follows: 1) direct dilution (dd) of LC14 and LC15 from organic solvent (5.0 mM solutions in N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMA) into complete culture media containing supplemental 10% fetal bovine serum ; 2) encapsulation into CrEL micelles and dilution of this micellar suspension at fullerene concentration of approximately 500 µM into complete medium, named LC14M and LC15M. Fig 2A shows the absorption spectra of LC14 and LC15 at the concentration of 1.0 × 10−5 M in either organic solvent or H2O to reveal the molecular packing effect of these two PSs in the micelle nano-droplet to the shift of optical absorption. In DMA– CHCl3 (3:1, v/v), both LC14 and LC15 are molecularly soluble to show their characteristic optical absorption bands that can be used for the comparison with those measured in aqueous solution. As a result, LC14 displayed a monotonically decreasing curve in extinction coefficient over 280– 550 nm with a weak shoulder band centered at ~320 nm corresponding to the high-energy absorption of C60> cage (Fig 2Ab). This band centered at 328 nm (ε = 5.2 × 107 cm2 /mol) is much more visible in the spectrum of LC15 (Fig 2Ad) along with characteristic CPAF and low-energy C60> cage absorption bands at 510 (ε = 1.4 × 107 cm2 /mol) and 690– 720 nm (weak, Fig 2Ad as the inset), respectively.

Figure 1. Synthesis and the structure of C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2]-(I−)10 (LC14) and C60[>CPAF-(C2MC3N6+)2]-(I−)10 (LC15).

Figure 2. UV-visible absorption spectra.

LC14 and LC15 in either aqueous PBS or DMA– CHCl3 (3:1, v/v) (A) and LC15/LC15M in either aqueous PBS or H2O with a weight ratio of CrEL indicated (B), all at the concentration of 1.0 × 10−5 M.

High water-solubility of two bulky pentacationic arms with many propyl groups of LC14 has tendency to limit the hydrophobic C60> cage moiety to only very small clusters in H2O showing the bathochromic shift of 280 nm band. In the case of LC15 in H2O (PBS), due to a larger hydrophobic size of C60-CPAF conjugate, the formation of self-assembled fullerosomes led to broad band absorptions with red-shifts at wavelengths over 350 nm (Fig 2Ac).

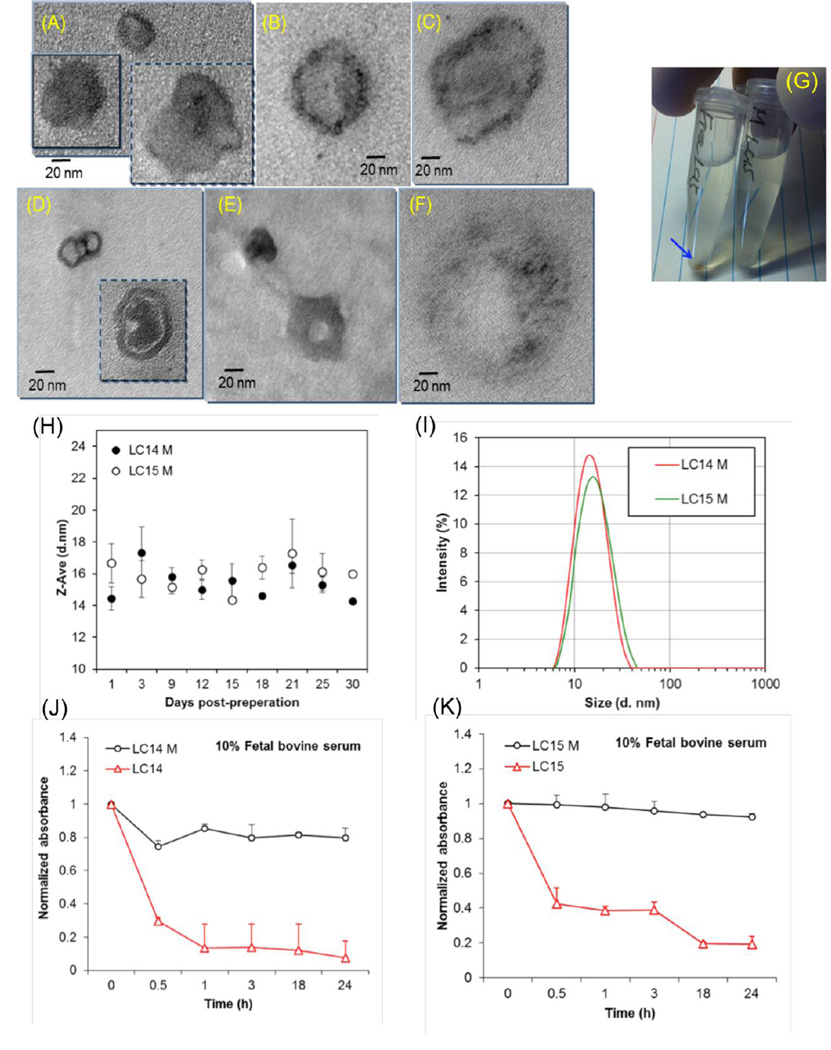

Unformulated LC14 tends to form only small clusters in H2O, giving only cluster aggregates with no sphere-type micrographic images. Upon association with one weight equivalent of CrEL, the mixture forms micelle images (Fig 3A) with, in principle, the LC14 molecules being located homogeneously or inhomogeneously at the interfacial area to H2O. As the CrEL quantity being increased to a ratio of 1:10 (Fig 3B) and 1:250 (Fig 3C, the same ratio in LC14M), the size of micelle increased to nano-droplets of ~120 nm in diameter (Fig 2C) with inhomogeneous distribution of LC14 at the edge area or the interfacial area. In the case of LC15, nearly proportional hydrophobic (C60-CPAF) and hydrophilic (C2MC3N6+ moieties) segments in an amphiphilic nanostructure makes LC15 readily to form molecularly self-assembled, bilayered fullerosome or double fullerosome (inset) vesicles, as shown in Fig 3D, with the darker ring-layer thickness matching with twice the molecular length of C60> and CPAF (~5 nm). By the addition of one weight equivalent of CrEL, the mixture self-assembled to vesicles (Fig 3E) in H2O with homogeneous distribution of LC15. As the quantity of CrEL being increased to ten times by weight, many large micellar nano-droplets (Fig 3F) of CrEL were found containing inhomogeneously distributed LC15 nano-clusters (darker spots or areas) at the interfacial area. Similar results were found for the LC15/CrEL ratio of 1:250 (similar to LC15M), except, these nano-clusters were dispersed in excessive CrEL. As the micrographic images of Fig 3D and 3F were compared, it is clear to realize that the average separation distance between each LC15 nano-cluster in the latter case is much greater than that in the tight packing fullerosome. This should significantly reduce the possibility of photoinduced self-quenching effect among excited- and ground-state LC15 molecules that could enhance the PDT efficacy. The TEM micrograph analysis was also verified by the UV-vis spectra of LC15– CrEL in a composition ratio of 1:1 to 1:15 (Fig 2B), showing clear re-appearance of C60> cage and CPAF absorption at 340 and 510 nm, respectively. The former band (Fig 2Bc–2Bf) is slightly shift (15 nm, dash lines of Fig 2B) to a longer wavelength from that of molecularly dissolved C60> cage (Fig 2Ba), indicating a small cluster formation. Well-defined absorption bands of Fig 2Bc– 2Bf, unlike the monotonic curve profile of LC15 in H2O (PBS, Fig 2Bb), are also indicative of a sufficient separation distance among each cluster within the CrEL-formulated micelle without an extended cluster aggregation consistent with the observation of TEM micrograph images.

Figure 3. Characterization of micellar formulation.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of micellar fullerenes (A– F). LC14M in a weight ratio (LC14:CrEL) of 1:1 (A),1:10 (B), and 1:250 (C). Similar micrographs of LC15 were taken in a weight ratio of none (D), 1:1 (E), and 1:10 (F). (G) Photograph of LC15 and LC15M in serum-containing medium showing precipitation of LC15. (H) Stability of LC14M and LC15M over 30 days in serum containing medium. (I) Particle size (diameter in nm) of LC14M and LC15M in serum containing medium. Stability over 24 h in serum containing medium of LC14 and LC14M (J) and LC15 and LC15M (K).

Figure 3G is a digital photograph of LC15 (free form) and LC15M (micelles) in serum-containing medium. In absence of micellar formulation, precipitation of LC15 was observed at the bottom of the centrifuge tube. Both micelles were found to be stable in PBS for at least 30 days of storage at 25 °C (Fig 3H). The particle sizes (diameter) of the micellar preparations, LC14M and LC15M were 14.5 ± 0.74 nm and 16.67 ± 1.23 nm, respectively (Fig 3I). The micellar formulation increased the stability of LC14 and LC15 in serum-containing medium. Minimal loss (<20%) of absorbance (λ = 323 nm) in LC14M and LC15M, indicated that the majority of the micelles remained well dispersed in 10% serum for up to 24 h (Figs 3J and 3K). In contrast for the free form of fullerenes LC14 and LC15, 30 min after incubation in 10% serum, more than 50% of absorbance (λ = 323 nm) loss was observed.

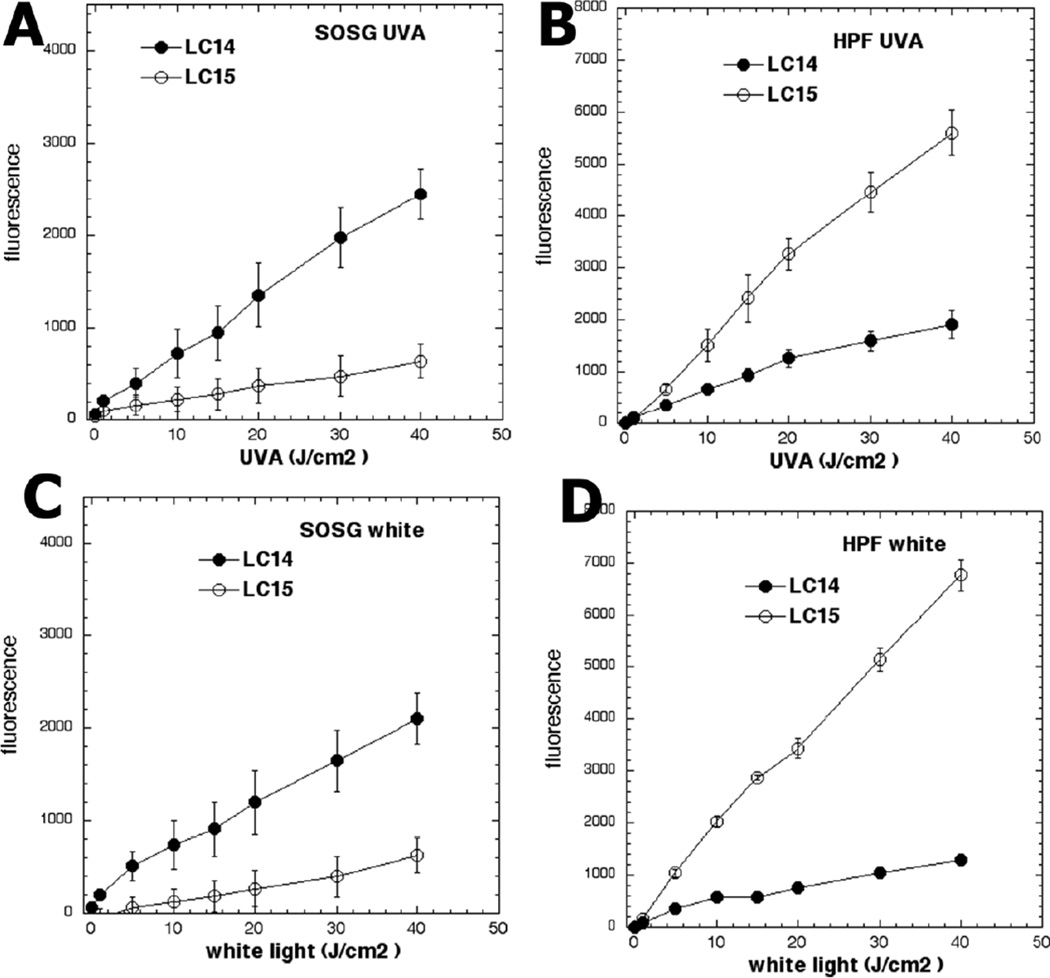

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation

Both LC14 and LC15 studied here activated singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG), thereby indicating singlet oxygen production as shown in Fig 4. LC14 produced more singlet oxygen than LC15 whether illuminated by UVA (Fig 4A) or by white light (Fig 4C). However, LC15 produced significantly higher activation of 3’-(4-hydroxyphenyl) fluorescein (HPF) when excited by UVA light (Fig 4B) and even more when excited by white light (Fig 4D), thus indicating production of hydroxyl radicals. Therefore we can conclude that, LC15 activated more HPF than SOG, while LC14 activated more SOG than HPF. The CrEL micellar preparations were not tested for the solution ROS probe experiments because the micelles prevent the water-soluble probes from coming into close contact with the source of the ROS, the encapsulated PS.

Figure 4. Photoactivation of fluorescence probes that are specific for different ROS by fullerenes.

LC14 and LC15 (5.0 µM in each well) were incubated with (A, C) SOSG (5.0 µM), or (B, D) HPF (5.0 µM); followed by delivery of the stated incremental fluence of UVA (A, B) or white light (C, D).

Photodynamic Effects on HeLa Cells of LC14, LC15, LC14M and LC15M in Vitro

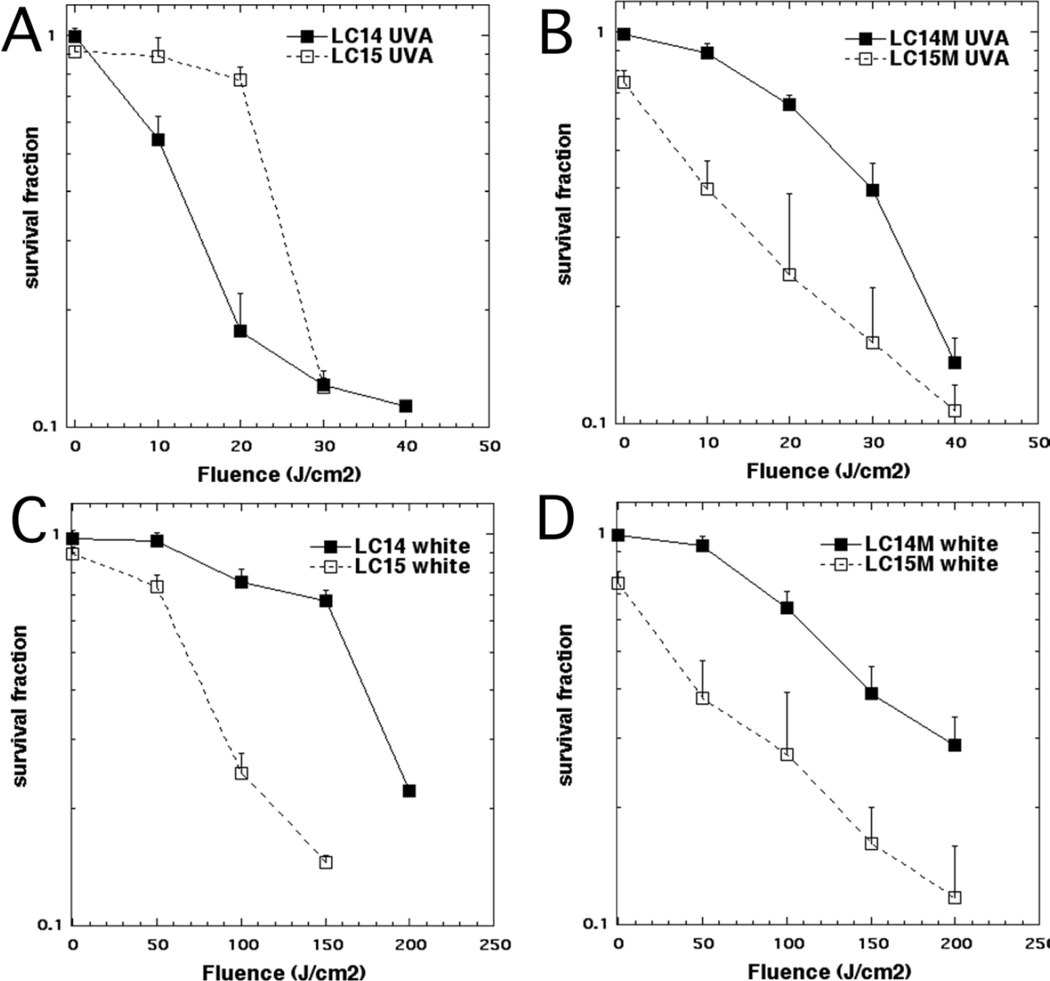

In order to compare the phototoxicity of LC14 and LC15 we varied the delivered light fluence at a constant concentration of 5.0 µM. The results are shown in Fig 5. LC14 was more effective than LC15 when excited by UVA radiation (Fig 5A). On the other hand, LC15 was more effective than LC14 when excited by white light (Fig 5B). It is worthwhile to note that dark toxicity (0 J/cm2) was very minor for both compounds at 5.0 µM.

Figure 5. PDT killing of human cancer cells.

HeLa cells were incubated with 5.0 µM LC14 and LC15 (A, B) or LC14M and LC15M (C, D) for 3 h, followed by delivery of stated fluence of UVA (A,C) or white light (B,D). The cells were then returned to incubator for 24 h and a Prestoblue viability assay was then carried out.

The data with CrEL-formulated micellar fullerenes are shown in Figs 5C and 5D. Note that dark toxicity (0 J/cm2) is still minor for both compounds at 5.0 µM and is probably due to CrEL dark toxicity. The UVA-light mediated PDT effectiveness of LC14 was decreased by CrEL encapsulation compared to DMA delivery (compare Fig 5C with Fig 5A). On the other hand, the UVA-mediated photodynamic efficacy of LC15 was markedly improved by CrEL encapsulation (compare Fig 5C to Fig 5A). However when excited by white light both LC14 and LC15 showed modest increases in PDT efficacy when delivered by micelles compared to DMA (compare Fig 5D to Fig 5B).

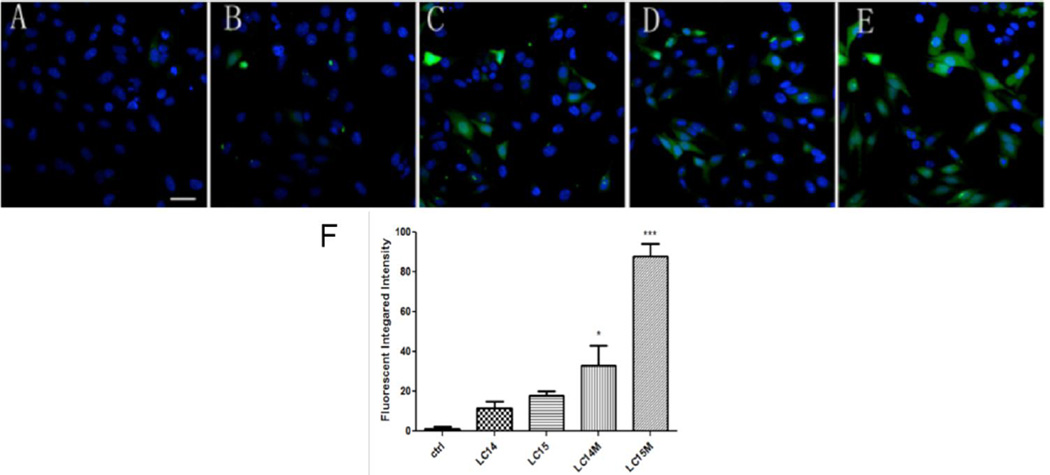

Detection of Intracellular ROS

Intracellular ROS production was demonstrated with representative images in Fig 6A– E and the quantification of the fluorescence measurements is shown in Fig 6F. When irradiated by 10 J/cm2 UVA light, we found a significant increase in intracellular ROS induced by LC14M and LC15M compared with LC14 and LC15 (*p <0.05, ***p <0.01). LC15M generated the highest amount of ROS than the other three compounds with UVA light irradiation in cells.

Figure 6. Confocal imaging for intracellular ROS generation upon UVA light irradiation.

CM-H2DCFDA (green) fluorescence for general intracellular ROS and Hoechst 33342 (blue) fluorescence for nuclei in Hela cells. A) Control; B) LC14; C) LC15; D) LC14M; E) LC15M. F) Quantification of green fluorescence of mean CMH2DCFDA fluorescence values. N = 4 fields per group. Error bars are SEM and * = p <0.05 and *** = p <0.01. Scale bar = 20 µm.

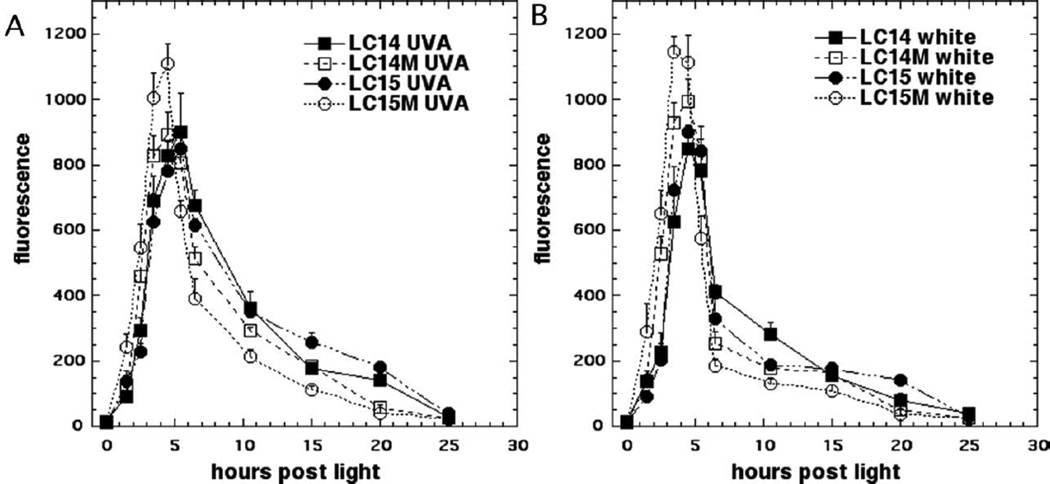

Apoptosis Induced by PDT

Many PS that have been used in PDT killing of cancer cells in vitro have been demonstrated to induce apoptosis. In the present study we employed a fluorescent substrate of effector caspase-3/7 to determine the time of maximum apoptosis. This is important because apoptosis is a dynamic process and assays performed at one or two time points only can miss the majority of apoptosis if it has occurred earlier or later than the time points chosen. Fig 7 shows the time course of apoptosis in HeLa cells after incubation with 5.0 µM LC14, LC15, LC14M and LC15M respectively and illumination with 20 J/cm2 UVA or 100 J/cm2 white light. The parameters used were set such that UVA would kill approximately 80% and for white light would kill approximately 60% of the cells as judged by the viability assay after 24 h. The results demonstrate that, for all fullerenes, there was an increase in caspase activity as early as 1.5 h after illumination that reached a maximum at 3.5– 5.5 h post-PDT, and subsequently declined after 15 h. LC14M and LC15M showed the peak point of apoptosis at about 4.5 h after excitation by UVA; while LC14 and LC15 reached the peak-point at 5.5 h (Fig 7A). Following illumination with white light, LC15M reached the peak at 3.5 h while LC14, LC15 and LC14M needed 4.5 h (Fig 7B). The relative amounts of caspase-3/7 activation correlated with the relative efficiencies of these fullerenes in terms of cell killing. The results showed that fullerenes encapsulated into micelles induced apoptosis earlier and to a higher degree than free form fullerenes.

Figure 7. Time course of apoptosis after PDT.

HeLa cells were incubated with LC14, LC15, LC14M and LC15M at 5.0 µM for 3 h, then illuminated by UVA 20 J/cm2 (A), or white light 100 J/cm2 (B). Apoptotic cells were detected by luminescence caspase-3/7 assay at different time points.

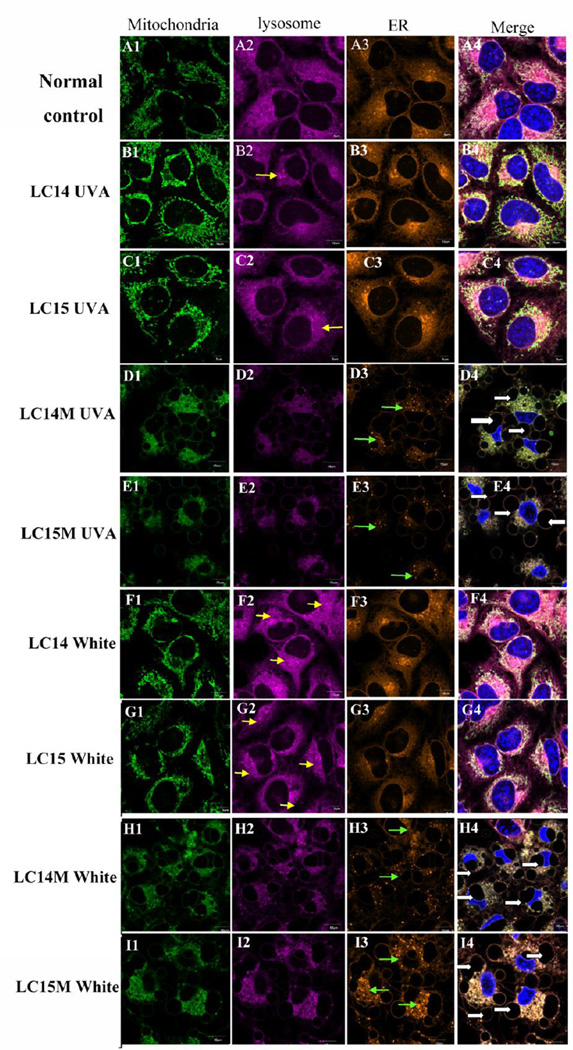

Subcellular Photodamage Localization

As previously mentioned, these fullerenes had insufficient fluorescence to allow their intracellular localization to be directly visualized by confocal microscopy. However, we used intracellular fluorescent probes to detect damage to sub-cellular organelles, such as mitochondria, lysosomes, ER and nucleus to determine their intracellular localization after PDT. We demonstrated this damage to organelles by two different methods; organelle specific probes (Fig 8), or by the use of acridine orange and rhodamine 123 (Fig S3, supporting information).

Figure 8. Confocal microscopy for subcellular damage to organelles.

LC14 (B1– B4; F1– F4) and LC15 C1– C4; G1– G4) delivered via direct dilution or as CrEL micelles, LC14M (D1– D4; H1– H4) and LC15M E1– E4; I1– I4). HeLa cells were incubated for 3 h with or without fullerenes (control, A1– A4), followed by illumination with 20 J/cm2 UVA (B1– E4) or 100 J/cm2 white light (F1– I4). Immediately thereafter mitotracker probe (green, column 1), lysotracker probe (violet; column 2), endoplasmic reticulum tracker probe (orange; column 3) and nuclear Hoechst (blue) (merged images column 4) was added, respectively, and incubated 30 min at 37 °C, then confocal microscopy was performed.

As shown in Fig 8, after illumination with 20 J/cm2 of UVA or 100 J/cm2 white light, we observed significant changes in the pattern of fluorescent probes compared with the normal control cells. Normal control cells had fluorescence typical of lysosomal, mitochondria and ER localization (Figs 8A1– 8A4). PDT treated cells with LC14 (Fig 8B1– 3; 8F1– 3) and LC15 (Fig 8C1– 3; 8G1– 3) however showed increased fluorescence including aggregated fluorescent structures (see yellow arrows) and disperse small fluorescent spots possible representing fragmentation of organelles as a result of stress30. LC14M (Figs 8D1– 3; 8H1– 3) and LC15M (Figs 8E1– 3; 8I1– 3)-induced PDT whether illuminated by UVA or white light, gave reduced fluorescence in organelles. The characteristic morphologies of ER, mitochondria and lysosomes were dramatically altered. We observed membrane blebbing (representing severe cell damage)31, 32 and faint, blurry fluorescence of the three organelle probes after PDT treatment with LC14M and LC15M. The nucleus showed deformation and karyopyknosis. ER showed disperse small fluorescent spots (see green arrows in Figs 8D3; 8E3) and many blebs around the nucleus (see white arrows in Figs 8D4; 8E4, 8H4; 8I4) were observed. When LC14M and LC15M were compared in terms of their UVA-induced PDT effects on mitochondria, lysosome and ER, there did not appear to be an obvious difference, except that in case of LC14M we observed more disperse small fluorescent spots in ER compared to LC15M (see green arrows in Fig 8H3, 8I3). On the contrary, LC15M-induced PDT using white light, caused more punctate aggregated fluorescent distribution in the cytoplasm than LC14M.

Discussion

Fullerenes have played a major role in the search for applications of nanotechnology in biology and medicine33. The extended electron-conjugation system found in C60 and homologues allows the molecules to absorb visible light, and the first excited singlet state can readily undergo intersystem crossing (ISC) to the excited triplet state. The photochemical pathway subsequently followed by the fullerene triplet depends heavily on peripheral substituents, the solvent if soluble34, and the supramolecular composition of any fullerene particles or aggregates35. Therefore, fullerenes have certain particular advantages over more traditional PS based on tetrapyrrole and phenothiazinium backbones36. They have high absorption coefficients, possess a high degree of photostabilty and little photobleaching compared to other classes of PS, and exhibit a photochemical mechanism with a significant contribution of Type-I reactive oxygen species especially hydroxyl radicals33. Their disadvantages include an absorption spectrum biased towards UVA and blue wavelengths, which do not possess the ability to penetrate deeply into tissue. Furthermore, fullerenes tend to have difficulties in being rendered water-soluble and have a pronounced tendency to aggregate37. Here we sought to overcome two of these above-mentioned disadvantages by (1) covalently attaching a light-harvesting antenna that would red-shift the absorption spectrum, thus allowing deeper tissue penetration and (2) formulating the fullerenes in CrEL micelles to improve solubility, increase cell uptake and possibly alter the intracellular localization.

It has been reported that cancer cells carry a much higher negative electrical charge than their homologous normal cells. Such changes in surface properties may allow more selective tumor targeting and this can be achieved by employing molecules carrying positive cationic charges as potential targeting agents38–40. Therefore, we employed a high number of cationic charges per C60> in both structure of LC14 and LC15 to enhance their targeting ability and provide molecularly a source of ten iodide counter anions to the same number of quaternary ammonium cations. In our recent study of photoinduced e− -transfer chemistry by LC14-(I−)10 involving I− using water-soluble O2− ·-reactive fluorescent probe, bis(2,4-dinitrobenzenesulfonyl)tetrafluorofluorescein carboxylate DNBs-TFFC, as the detecting agent41, we have confirmed directly their high efficacy in O2− ·-production upon irradiation by either UVA or white light. In the case of LC14 without a light-harvesting antenna, continuous irradiation on the fullerene cage moiety should stimulate its photoexcitation from the ground to singlet excited state, giving 1C60*[>M(C3N6+C3)2] and subsequent long-lived triplet excited state 3C60*[>M(C3N6+ C3)2] after ISC occurring in a time scale of 1.3 ns5, 41. This duration is long enough to allow intermolecular triplet energy transfer from the 3(C60>)* moiety to O2 yielding a reactive 1O2. However, in the presence of electron-rich iodide anions, photoinduced electron-transfer from I−, via oxidation, to the 3(C60>)* cage moiety of photoexcited LC14 was found to be plausible, leading to the formation of fullerenyl anion radical intermediate C60− ·[>M(C3N6+C3)2]. Photoinduced oxidation of iodide (I−) can be expressed by the equation: 3(I−) → I3− + 2e−. Following further electron-transfer from the (C60>)− · moiety to O2 producing O2− · was considered to be the plausible pathway and approach to enhance type-I photophysical mechanism.

The CPAF antenna chromophore of LC15 is in an assembly of electronic push– pull configuration with a highly electron-withdrawing 1,1-dicyanoethylenyl (DCE) group adjacent to the electron-accepting C60> cage and an electron-donating diphenylamine group located at the opposite end of antenna moiety. Molecular orbital calculation of C60-CPAF conjugate has revealed a high degree of molecular polarization with negative charges being localized at the bridging DCE region next to the fullerene cage42. Therefore, other than the enhanced red-absorption of LC15 to 600 nm, photoinduced intramolecular e− -transfer from CPAF to C60> can occur readily to form the charge-separated (CS) state of C60− ·[>(CPAF)+·-(C2MC3N6+)2]-(I−)10 in polar solvents, including PhCN, DMF, and H2O, as confirmed by the ns transient absorption band of (C60>)− · radical-ion pairs centered at 1020 nm42. In general, we should consider the generation of this CS state (for type-I) and the alternative energy-transfer process (for type-II) from C60[>1(CPAF)*-(C2MC3N6+)2] to the C60> moiety yielding the triplet state of 3C60*[>CPAF-(C2MC3N6+)2]-(I−)10 in a competitive manner, however, with the former being favorable in H2O. In the presence of electron-donating iodide counter anions (I−), the electron-accepting capability of 3C60*[>CPAF-(C2MC3N6+)2] cage moiety may induce electron-transfer from the iodide anion leading to the formation of C60− ·[>CPAF-(C2MC3N6+)2] prior to the further transfer of this electron to O2 that yields O2− ·. Likewise, photoinduced oxidation of I− may neutralize the cationic (CPAF)+ · moiety of the CS state that affords the same C60− ·[>CPAF-(C2MC3N6+)2]-(I3−)x(I−)y. Therefore, interplay of energy- and electron-transfer processes between C60>, CPAF antenna, and I− anions all facilitate the type-I photochemistry without the consideration of transferring kinetic rate.

We found that singlet oxygen (1O2) was produced from type-II energy transfer reactions by exciting LC14 with either UVA or white light, while highly reactive HO· formed from electron transfer type-I was the only ROS observed from LC15 regardless of excitation light. The HPF probe is selective for detection of HO· and peroxynitrite, via quinone formation with the detection sensitivity reported to be roughly 145- and 90-fold higher for HO· than for 1O2 and O2− ·, respectively43. The reason for the switch from type-II to type-I photochemical mechanisms when the triphenylamine antenna was attached must be associated with the greater supply of electrons in the tertiary amine group predisposing the mechanisms towards electron transfer rather than energy transfer. We did not see large changes in the relative distribution of type-I and type-II ROS when we compared UVA and white light excitation, although there was a tendency for UVA to produce more HO· and white light to produce more 1O2. This was in agreement with a previous finding where UVA excitation of C84 fullerenes showed progressively more HO· with progressively shorter excitation wavelengths44. The explanation for this observation was attributed to more electron transfer reactions after higher energy photonic excitation.

Most PS easily form aggregates in aqueous media, and such aggregate formation severely decreases ROS generation, thus reduce the PDT efficacy45, 46. For PDT of neoplastic lesions, PS encapsulated in liposomes have been developed and proven to yield a more pronounced and selective targeting to tumor tissues47. However, the cost of lipids and the preparation processes might pose barriers to the development of such products for clinical applications. Polymeric micelles have emerged as a alternative carrier system to deliver PS for anti-tumor treatment48. In this study, we hypothesized that CrEL micelles would enhance solubility of the relatively hydrophobic fullerenes studied here (especially LC15) and minimize aggregation to improve partitioning into the intracellular space and facilitate better arrival at the target sites. This hypothesis was partially confirmed by enhanced PDT activity upon using micellar formulations of LC15 and LC14. The significantly higher ROS generation observed with PDT using LC15M can be attributed to less aggregation and better delivery of the PS which both correlate with better cytotoxicity. Moreover, earlier apoptosis observed with LC14M and LC15M was most likely due to earlier uptake provided by the micellar delivery. CrEL is a commercially available polyoxyethylene glycerol triricinoleate—a nonionic amphipathic agent widely used as a formulation or drug delivery vehicle for various poorly water-soluble drugs49. However, it is worth noting that CrEL use has been associated with severe anaphylactoid hypersensitivity reactions, hyperlipidaemia, abnormal lipoprotein patterns, aggregation of erythrocytes and peripheral neuropathy50, 51. Similarly, there is some concern about the in vivo toxicity of C60 and other fullerenes. For example, some C60 derivatives were reported to be highly toxic52, 53. Encapsulating these fullerenes may be a good alternative to reduce their in vivo toxicity.

It is known that fullerenes tend to form so-called nano-aggregates in aqueous solution. In fact, there are several reported studies with pristine C60 in this nano-aggregated form54, 55. The solutions formed are apparently clear showing the particles have sizes below 20 nm. The fact that LC14 and LC15 precipitated after centrifugation, suggests that some of these compounds (LC15) were present in aqueous medium as nano-aggregates with the majority of compound as either in a molecularly dispersed form or in a form of nano-clusters (~3– 5 molecules only) within CrEL nano-droplets (see Fig 3F). However, based on our findings, we assume that the fullerenes were still able to enter the cells by endocytosis and mediate PDT by initiating apoptosis in the cancer cells after lysosomal damage56, 57. This finding also suggested that intracellular delivery of LC14 and LC15 occurred by endocytosis rather than diffusion across the membrane. On the contrary, LC14M and LC15M delivered by micelles caused photodamage in all of the three organelles mentioned above, including the nucleus as might be expected if the micelles fused with the membrane and delivered their cargo across it. Following PDT, alterations in morphology of the organelles were distinguishable between the free and the micellar forms of the fullerenes. PS that localize in mitochondria are known to be much more phototoxic than PS that localize in endosomes or lysosomes58, 59. Micellar compounds were already reported to induce both mitochondria-associated and ER-associated cell damage60. Higher amounts of ROS detected with the micellar formulations (especially LC15M) further confirmed the direct photodamage to the mitochondria (see Fig 6). Organelle blebbing was a characteristic change observed in LC14M and LC15M, and this process is similar to the characteristics of oncosis that has been reported to be induced by inhibition of ATP production, hypoxia and increased permeability of plasma membrane61. Our data demonstrated the induction of apoptosis by LC14M and LC15M- PDT at 3.5– 5.5h. Similar results also have been showed by fullerene-PDT in CT26 cells at 4–6 h after illumination33. The relatively more rapid induction of apoptosis after illumination with LC14M and LC15M is probably due to enhanced uptake.

In conclusion we have shown that attachment of an additional light-harvesting antenna to the decacationic fullerene LC14 to form LC15 increases the PDT activity when excited with longer wavelength white light (compared to UVA). Furthermore, micellar formulation increases the rate of uptake, gives more widespread damage to organelles, hastens apoptosis and increases overall killing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by US NIH grants R01CA137108 to LYC and R01AI050875 to MRH. Rui Yin was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81172495) in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A. Supplementary Material Available

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/

References

- 1.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2011;61:250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castano AP, Demidova TN, Hamblin MR. Mechanisms in photodynamic therapy: part one--photosensitizers, photochemistry and cellular localization. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2004;1:279–293. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(05)00007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castano AP, Demidova TN, Hamblin MR. Mechanisms in photodynamic therapy: part two -cellular signalling, cell metabolism and modes of cell death. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2005;2:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(05)00030-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satoh M, Takayanagi I. Pharmacological studies on fullerene (C60), a novel carbon allotrope, and its derivatives. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:513–518. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cpj06002x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guldi DM, Prato M. Excited-state properties of C(60) fullerene derivatives. Accounts of chemical research. 2000;33:695–703. doi: 10.1021/ar990144m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottari G, de la Torre G, Guldi DM, Torres T. Covalent and noncovalent phthalocyanine-carbon nanostructure systems: synthesis, photoinduced electron transfer, and application to molecular photovoltaics. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6768–6816. doi: 10.1021/cr900254z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujitsuka MO, Ito O. In: Encyclopedia of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. Nalwa HS, editor. Valencia, CA: American Scientific Publishers; 2004. pp. 593–615. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson CA, Evans DH, Abrahamse H. Photodynamic therapy (PDT): a short review on cellular mechanisms and cancer research applications for PDT. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology. B, Biology. 2009;96:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamakoshi Y, Umezawa N, Ryu A, Arakane K, Miyata N, Goda Y, et al. Active oxygen species generated from photoexcited fullerene (C60) as potential medicines: O2-• versus 1O2. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:12803–12809. doi: 10.1021/ja0355574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen AW, Wilson SR, Schuster DI. Biological applications of fullerenes. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 1996;4:767–779. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosi S, Da Ros T, Spalluto G, Prato M. Fullerene derivatives: an attractive tool for biological applications. European journal of medicinal chemistry. 2003;38:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao F, Saitoh Y, Miwa N. Anticancer effects of fullerene [C60] included in polyethylene glycol combined with visible light irradiation through ROS generation and DNA fragmentation on fibrosarcoma cells with scarce cytotoxicity to normal fibroblasts. Oncology research. 2011;19:203–216. doi: 10.3727/096504011x12970940207805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperandio FF, Huang YY, Hamblin MR. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy to kill Gram-negative bacteria. Recent patents on anti-infective drug discovery. 2013;8:108–120. doi: 10.2174/1574891x113089990012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasermann F, Kempf C. Photodynamic inactivation of enveloped viruses by buckminsterfullerene. Antiviral research. 1997;34:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(96)01207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sera N, Tokiwa H, Miyata N. Mutagenicity of the fullerene C60-generated singlet oxygen dependent formation of lipid peroxides. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2163–2169. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.10.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burlaka AP, Sidorik YP, Prylutska SV, Matyshevska OP, Golub OA, Prylutskyy YI, et al. Catalytic system of the reactive oxygen species on the C60 fullerene basis. Experimental oncology. 2004;26:326–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mroz P, Bhaumik J, Dogutan DK, Aly Z, Kamal Z, Khalid L, et al. Imidazole metalloporphyrins as photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy: role of molecular charge, central metal and hydroxyl radical production. Cancer letters. 2009;282:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Tabata Y. Photodynamic therapy of fullerene modified with pullulan on hepatoma cells. Journal of drug targeting. 2010;18:602–610. doi: 10.3109/10611861003599479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang M, Huang L, Sharma SK, Jeon S, Thota S, Sperandio FF, et al. Synthesis and photodynamic effect of new highly photostable decacationically armed [60]- and [70]fullerene decaiodide monoadducts to target pathogenic bacteria and cancer cells. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2012;55:4274–4285. doi: 10.1021/jm3000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mroz P, Xia Y, Asanuma D, Konopko A, Zhiyentayev T, Huang YY, et al. Intraperitoneal photodynamic therapy mediated by a fullerene in a mouse model of abdominal dissemination of colon adenocarcinoma. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabata Y, Murakami Y, Ikada Y. Photodynamic effect of polyethylene glycol-modified fullerene on tumor. Japanese journal of cancer research: Gann. 1997;88:1108–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma SK, Chiang LY, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy with fullerenes in vivo: reality or a dream? Nanomedicine (UK) 2011;6:1813–1825. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang YY, Balasubramanian T, Yang E, Luo D, Diers JR, Bocian DF, et al. Stable synthetic bacteriochlorins for photodynamic therapy: role of dicyano peripheral groups, central metal substitution (2H, Zn, Pd), and Cremophor EL delivery. Chem Med Chem. 2012;7:2155–2167. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redmond RW, Land EJ, Truscott TG. Aggregation effects on the photophysical properties of porphyrins in relation to mechanisms involved in photodynamic therapy. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1985;193:293–302. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-2165-1_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin S, Zhou L, Gu Z, Tian G, Yan L, Ren W, et al. A new near infrared photosensitizing nanoplatform containing blue-emitting up-conversion nanoparticles and hypocrellin A for photodynamic therapy of cancer cells. Nanoscale. 2013 doi: 10.1039/c3nr03515h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Z, Dai T, Huang L, Kurup DB, Tegos GP, Jahnke A, et al. Photodynamic therapy with a cationic functionalized fullerene rescues mice from fatal wound infections. Nanomedicine (UK) 2010;5:1525–1533. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiang LY, Padmawar PA, Rogers-Haley JE, So G, Canteenwala T, Thota S, et al. Synthesis and characterization of highly photoresponsive fullerenyl dyads with a close chromophore antenna-C(60) contact and effective photodynamic potential. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:5280–5293. doi: 10.1039/C0JM00037J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein OJ, Bhayana B, Park YJ, Evans CL. In vitro optimization of EtNBS-PDT against hypoxic tumor environments with a tiered, high-content, 3D model optical screening platform. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2012;9:3171–3182. doi: 10.1021/mp300262x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans CL, Abu-Yousif AO, Park YJ, Klein OJ, Celli JP, Rizvi I, et al. Killing hypoxic cell populations in a 3D tumor model with EtNBS-PDT. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wikstrom JD, Israeli T, Bachar-Wikstrom E, Swisa A, Ariav Y, Waiss M, et al. AMPK Regulates ER Morphology and Function in Stressed Pancreatic beta-Cells via Phosphorylation of DRP1. Molecular endocrinology. 2013;27:1706–1723. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lane JD, Allan VJ, Woodman PG. Active relocation of chromatin and endoplasmic reticulum into blebs in late apoptotic cells. Journal of cell science. 2005;118:4059–4071. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meesmann HM, Fehr EM, Kierschke S, Herrmann M, Bilyy R, Heyder P, et al. Decrease of sialic acid residues as an eat-me signal on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes. Journal of cell science. 2010;123:3347–3356. doi: 10.1242/jcs.066696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mroz P, Pawlak A, Satti M, Lee H, Wharton T, Gali H, et al. Functionalized fullerenes mediate photodynamic killing of cancer cells: Type I versus Type II photochemical mechanism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:711–719. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamakoshi Y, Umezawa N, Ryu A, Arakane K, Miyata N, Goda Y, et al. Active oxygen species generated from photoexcited fullerene (C60) as potential medicines: O2-* versus 1O2. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:12803–12809. doi: 10.1021/ja0355574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura E, Isobe H. Functionalized fullerenes in water. The first 10 years of their chemistry, biology, and nanoscience. Accounts of chemical research. 2003;36:807–815. doi: 10.1021/ar030027y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mroz P, Tegos GP, Gali H, Wharton T, Sarna T, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy with fullerenes. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2007;6:1139–1149. doi: 10.1039/b711141j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizuno K, Zhiyentayev T, Huang L, Khalil S, Nasim F, Tegos GP, et al. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy with Functionalized Fullerenes: Quantitative Structure-activity Relationships. Journal of nanomedicine & nanotechnology. 2011;2:1–9. doi: 10.4172/2157-7439.1000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornguth SE, Kalinke T, Robins HI, Cohen JD, Turski P. Preferential binding of radiolabeled poly-L-lysines to C6 and U87 MG glioblastomas compared with endothelial cells in vitro. Cancer research. 1989;49:6390–6395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ambrose EJ, Easty DM, Jones PC. Specific reactions of polyelectrolytes with the surfaces of normal and tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 1958;12:439–447. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1958.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim B, Han G, Toley BJ, Kim CK, Rotello VM, Forbes NS. Tuning payload delivery in tumour cylindroids using gold nanoparticles. Nature nanotechnology. 2010;5:465–472. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M, Maragani S, Huang L, Jeon S, Canteenwala T, Hamblin MR, et al. Synthesis of decacationic [60]fullerene decaiodides giving photoinduced production of superoxide radicals and effective PDT-mediation on antimicrobial photoinactivation. European journal of medicinal chemistry. 2013;63:170–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Khouly ME, Padmawar P, Araki Y, Verma S, Chiang LY, Ito O. Photoinduced processes in a tricomponent molecule consisting of diphenylaminofluorene-dicyanoethylene-methano[60]fullerene. The journal of physical chemistry. A. 2006;110:884–891. doi: 10.1021/jp055324u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Setsukinai K, Urano Y, Kakinuma K, Majima HJ, Nagano T. Development of novel fluorescence probes that can reliably detect reactive oxygen species and distinguish specific species. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:3170–3175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sperandio FF, Sharma SK, Wang M, Jeon S, Huang YY, Dai T, et al. Photoinduced electron-transfer mechanisms for radical-enhanced photodynamic therapy mediated by water-soluble decacationic C(7)(0) and C(8)(4)O(2) Fullerene Derivatives. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett LE, Ghiggino KP, Henderson RW. Singlet oxygen formation in monomeric and aggregated porphyrin c. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology. B, Biology. 1989;3:81–89. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(89)80022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith GJ. The effects of aggregation on the fluorescence and the triplet state yield of hematoporphyrin. Photochem Photobiol. 1985;41:123–126. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Derycke AS, de Witte PA. Liposomes for photodynamic therapy. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2004;56:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Nostrum CF. Polymeric micelles to deliver photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2004;56:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sparreboom A, Loos WJ, Verweij J, de Vos AI, van der Burg ME, Stoter G, et al. Quantitation of Cremophor EL in human plasma samples using a colorimetric dye-binding microassay. Analytical biochemistry. 1998;255:171–175. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A. Cremophor EL: the drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. European journal of cancer. 2001;37:1590–1598. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kiss L, Walter FR, Bocsik A, Veszelka S, Ozsvari B, Puskas LG, et al. Kinetic analysis of the toxicity of pharmaceutical excipients Cremophor EL and RH40 on endothelial and epithelial cells. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2013;102:1173–1181. doi: 10.1002/jps.23458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kolosnjaj J, Szwarc H, Moussa F. Toxicity studies of fullerenes and derivatives. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;620:168–180. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-76713-0_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dal Forno GO, Kist LW, de Azevedo MB, Fritsch RS, Pereira TC, Britto RS, et al. Intraperitoneal exposure to nano/microparticles of fullerene (C(6)(0)) increases acetylcholinesterase activity and lipid peroxidation in adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) brain. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:623789. doi: 10.1155/2013/623789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horie M, Nishio K, Kato H, Shinohara N, Nakamura A, Fujita K, et al. In vitro evaluation of cellular responses induced by stable fullerene C60 medium dispersion. J Biochem. 2010;148:289–298. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patnaik A. Structure and dynamics in self-organized C60 fullerenes. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2007;7:1111–1150. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2007.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kessel D. Subcellular targets for photodynamic therapy: implications for initiation of apoptosis and autophagy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10(Suppl 2):S56–S59. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishiyama N, Morimoto Y, Jang WD, Kataoka K. Design and development of dendrimer photosensitizer-incorporated polymeric micelles for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2009;61:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacDonald IJ, Morgan J, Bellnier DA, Paszkiewicz GM, Whitaker JE, Litchfield DJ, et al. Subcellular localization patterns and their relationship to photodynamic activity of pyropheophorbide-a derivatives. Photochemistry and photobiology. 1999;70:789–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishiyama N, Nakagishi Y, Morimoto Y, Lai PS, Miyazaki K, Urano K, et al. Enhanced photodynamic cancer treatment by supramolecular nanocarriers charged with dendrimer phthalocyanine. Journal of controlled release: official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2009;133:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shahzidi S, Cunderlikova B, Wiedlocha A, Zhen Y, Vasovic V, Nesland JM, et al. Simultaneously targeting mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum by photodynamic therapy induces apoptosis in human lymphoma cells. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;10:1773–1782. doi: 10.1039/c1pp05169e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Majno G, Joris I. Apoptosis, oncosis, and necrosis. An overview of cell death. The American journal of pathology. 1995;146:3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.