Abstract

Background

Over 240,000 women die in the U.S. from coronary heart disease (CHD) annually. Identifying women’s symptoms that predict a CHD event such as myocardial infarction (MI) could decrease mortality.

Objective

For this longitudinal observational study, we recruited 1097 women, who were either clinician or self-referred to a cardiologist and undergoing initial evaluation by a cardiologist, to assess the utility of the prodromal symptoms (PS) section of the McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey (MAPMISS) in predicting the occurrence of cardiac events in women.

Methods and Results

Seventy-seven women experienced events (angioplasty, stent placement, coronary artery bypass, MI, death) during the two-year follow up. The most common events were stents alone (38.9%) or in combination with angioplasty (18.2%). Ten women had MIs; 4 experienced cardiac death. Cox proportional hazards was used to model time to event. The prodromal score was significantly associated with risk of an event (HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.06–1.13), as was the number of PS endorsed by each woman per visit. After covariate adjustment, five symptoms were significantly associated with increased risk: discomfort in jaws/teeth, unusual fatigue, arm discomfort, shortness of breath and general chest discomfort (HR = 3.97, 95% CI = 2.32–6.78). Women reporting >1of these symptoms were 4 times as likely to suffer a cardiac event as women with none.

Conclusions

Both the MAPMISS PS scores and number of PS were significantly associated with cardiac events, independent of risk factors, suggesting there are specific PS that can be easily assessed using the MAPMISS. This instrument could be an important component of a predictive screen to assist clinicians in deciding the course of management for women.

Keywords: Women, Coronary disease, Myocardial Infarction, Cardiovascular disease

Although cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rates are declining for women, as they are for men, women’s CVD mortality rates continue to exceed those of men.1 Coronary heart disease (CHD), a subset of CVD, is responsible for over 240,000 deaths among women in the United States each year.2 For many years, there has been a consensus that under-recognition of women’s symptoms and difficulty in diagnosing CHD in women contribute to their greater disability and mortality following a CHD event. In response to the challenges in diagnosing CHD in women, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality commissioned a review of the accuracy of noninvasive technologies for diagnosis of CHD in women.3 Although this is a seminal review, only studies of women with chest pain syndrome were included. Yet, numerous studies have reported that chest pain is not present in a significant number of women with CHD and many women report little or no chest pain prior to or with myocardial infarction (MI).4–7

Thus, it is vital to identify symptoms other than chest pain that are associated with risk of progressing to a CHD event such as MI, so that women experiencing non-chest pain symptoms may undergo appropriate diagnostic testing. Several risk score calculators, such as the Framingham and Reynolds scores, are useful in predicting long-term risk for CVD.8,9 However, these instruments do not assess the prodromal symptoms, other than angina, that women frequently experience prior to MI.10,11 The McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey (MAPMISS) assesses the presence of a broad range of prodromal symptoms (PS) among women. However, although the MAPMISS has been used in several studies10,12,13 all have been retrospective. As a result, we know little about the predictive utility of symptoms in the PS section of the MAPMISS.

The aim of this longitudinal observational study therefore was to assess the utility of the MAPMISS PS scores and PS counts in predicting the occurrence of cardiac events in women over a 2-year period. Our goal was to identify the most parsimonious subset of PS data predictive of angioplasty, stent placement, coronary artery bypass, MI or death attributed to CHD.

METHODS

Setting and Sample

We recruited women who were either clinician- (n=903, 82.32%) or self-referred (n=194, 17.68%) to cardiology practices for initial cardiology evaluation. We recruited women from three sites in Arkansas and one in Kentucky. The sites were either associated with academic centers or large state-wide private practices with multiple satellite clinics in urban, suburban, and rural areas. To be eligible for the study, women had to a) have been referred or self-referred to a cardiologist for initial CHD evaluation and have no current or previous CHD diagnosis, b) identify themselves as African American/Black or Caucasian/White, c) be at least 21 years old, d) be cognitively intact, e) have access to a telephone, and f) be able to read or spell out medication information from their prescriptions or designate a family member to perform this task.

Measures

The McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey (MAPMISS) has three sections: (1) the Acute Symptom section which is administered following a cardiac event (e.g., MI, angioplasty), (2) the 30 question Prodromal Symptom (PS) section administered in the absence of a known cardiac event, and (3) a Background section that addresses demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, other risk factors, and current medications.10,14 The analyses reported here are based on data from the PS and Background sections. In the PS section, women are asked about the occurrence of each of 30 PS in the preceding 3 months. For each of the symptoms reported, they are then asked to specify the intensity and frequency with which it occurred.Categorical response options for intensity are mild, medium or severe, scored 1–3, respectively. Categorical response options for frequency are daily, several times/week, > 1/week, >2/month, monthly and <monthly, scored 7, 3.5, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.167 days per week, respectively. A PS not reported for the period is scored 0 for intensity and 0 for frequency. Individual PS scores are calculated as the product of intensity and frequency (range 0–21, where 0 indicates the absence of the symptom).14 A cumulative PS score is calculated as the sum of individual symptom scores (range 0–630). The MAPMISS has been shown to have content validity and solid test/re-test reliability with both African American/Black and Caucasian women (r=0.91).14,15

The Short Blessed Test (SBT) assesses for cognitive impairment and was administered at baseline and again at 12 months to assure that participants were sufficiently cognitively intact to provide meaningful information. The SBT includes six weighted items that evaluate orientation and memory and has established reliability and validity.16–18 Each item is scored 0–5, and lower scores indicate better cognitive function.17 Women who scored 16 or higher at baseline were not eligible to participate in the study.

Procedures

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each site prior to recruitment. At all sites, new female patients received a flyer describing the study as part of the packet of forms completed by new patients at the site. Interested women returned the flyer to office staff along with their names and telephone numbers and completed a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization permitting the clinic to disclose their names and medical history (reason for clinic visit) to the research team. A research assistant (RA) collected the forms, telephoned interested women, explained the study, answered questions, and for interested women, obtained verbal consent and authorization to review their medical records. The RA then administered the SBT; if the woman scored <16, the RA scheduled a telephone interview to administer the MAPMISS. Participants completed follow-up telephone interviews at 3-month intervals that asked about symptoms experienced during the previous 3-month period, for 2 years or until a CHD event occurred.

If a woman reported a CHD event (angioplasty, stent placement, coronary artery bypass surgery, or MI) during the previous 3 months, the woman completed the acute section of the MAPMISS questions, and an RA audited the woman’s medical records from the cardiology clinic, emergency department, and/or hospital where she received treatment to verify occurrence of the event. Once an event occurred, a woman’s participation in the study was complete and no further follow-up assessments were conducted. If a woman died, family members were asked about her hospitalization and cause of death. We also obtained a death certificate to confirm cause of death. The first author and other team members evaluated whether a CHD event had occurred and whether the death was cardiac-related. A cardiologist adjudicated all disagreements and made the final determination.

All interviews were administered by RAs located at the site using a computer-assisted telephone interview system that allowed them to enter data directly into a computer program while conducting the interviews. The baseline assessment covered PS in the previous 3 months, demographic characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors including comorbidities and CHD family history, and currently prescribed medications. It took approximately 60 minutes to complete. Follow-up assessments included only the MAPMISS PS section with respect to the previous 3-month period. Follow-up interviews took approximately 20–30 minutes. Women received a $40 gift certificate for completing the baseline interview, $15 for each subsequent 3-month follow-up interview, and $30 for the final interview.

Statistical Methods

MAPMISS data were analyzed to generate PS symptom counts (present/absent; 0–30), individual PS symptom scores (0–21) and cumulative PS symptom scores (0–630). As described earlier, individual scores for each of the 30 PSs were calculated for each woman at each visit based on the frequency (0–7 days/week) and intensity (0–3) she reported for each symptom in the preceding 3 months. A cumulative PS score was also computed for each woman at each visit as the sum of her 30 individual PS scores.

We had two main analytic goals: (1) to assess the utility of PS scores in predicting study outcomes (angioplasty, stent placement, coronary artery bypass, MI or death attributed to CHD), and (2) to identify the most parsimonious subset of PS data predictive of cardiac events. We used the cumulative PS score to address the first goal because it is the most information-rich MAPMISS measure, incorporating symptom count, intensity and frequency. To this end, we estimated hazard ratios (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for experiencing an adverse cardiac event using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression modeling, including cumulative PS scores as a time-dependent covariate. The model was first adjusted for age and race only. To determine whether cumulative PS scores contributed independently to prediction after accounting for the variables included in existing risk measures, we repeated the analysis adjusting the model for BMI, education, income, marital status, physical activity, family history of CHD, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, in addition to age and race.

Because assessing intensity and frequency is clinically time-consuming and perception of symptom-intensity may vary by individual, we next looked at the predictive utility of the PS count, following the same two-step procedure used for cumulative PS scores. Lastly, we explored whether predictive utility might be retained if data (scores or counts) were collected on a specific subset of symptoms. In identifying the most parsimonious predictive models, we first fit separate score and count models for each PS individually. In each case (scores and counts), we then evaluated all PS together and the simplest models with the smallest number of PS and the greatest explanatory power were selected using a strategy which combined stepwise regression, Akaike information criteria, and the best subset selection method, as suggested by Shtatland et al.19,20 This strategy was designed to retain the best qualities of each of these three model building methods.

The predictive ability of the final models was assessed by computing Harrell’s concordance or C-statistic and the corresponding bootstrapped 95% confidence interval.21,22 Harrell’s C-statistic is analogous to the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for survival data and it is an estimate of the probability that for 2 randomly selected individuals, the risk of failure predicted from the model will be higher for the individual that fails first. Thus the C-statistic is interpreted the same way that the area under the ROC is interpreted. Specifically, if C=1, then the model has perfect prediction, whereas if C=0.5, the model’s predictive ability is no better than a coin flip. Data analysis was performed using Stata® version 1223 and SAS 9.3.24

RESULTS

A total of 1114 women were enrolled in the study who were either clinician or self-referred to cardiology practices for initial evaluation. Referrals occurred for a variety of reasons including initial evaluation of symptom(s) (n=469, 42.75%), to establish a relationship with a cardiologist (n=286, 26.07%), or other reasons such as for clearance prior to surgery. Of the 1114 women, 3 of these were found ineligible and 14 did not complete the study (missed a total of 3 interviews or could not be located). Among the remaining 1097 (98.5%) women, a total of 77 women (7%) experienced cardiac events during the 2 years of follow up (see Table 1). The majority (57.1%) of cardiac events were stent placements, either alone (38.9%) or in combination with angioplasty (18.2%). Ten of the 77 women had MIs, and 4 women suffered cardiac-related death.

Table 1.

Type and distribution of cardiac events/interventions in 77 women

| Cardiac event | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Non-fatal events | ||

| Angioplasty | 4 | 5.2 |

| Stent placement | 30 | 38.9 |

| Stent placement with angioplasty | 14 | 18.2 |

| Bypass surgery | 15 | 19.5 |

| MI | ||

| Alone | 4 | 5.2 |

| With angioplasty | 2 | 2.6 |

| With angioplasty and stent placement | 4 | 5.2 |

| Cardiac deaths | 4 | 5.2 |

| Total | 77 |

Characteristics of the 1097 women who completed the study are summarized in Table 2, stratified by the occurrence of a cardiac event. Briefly, the majority of women were White (86.5%), more than 50 years of age (61.1%), with more than a high school education (64%) and married (60.8%). Most of the women were overweight or obese (74.3%) and nearly all reported a family history of CHD (98.1%). The 77 women (7%) who experienced events during the 2-year follow-up were generally older, had less education, lower incomes, and more chronic conditions than those who did not experience a cardiac event.

Table 2.

Selected characteristics of the 1097 women at baseline interview

| No. (%) of women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All (N = 1097) |

Event (N=77) |

No Event (N = 1020) |

p-value* |

| Race | 0.1290 | |||

| African American | 148 (13.5) | 6 (7.8) | 142 (13.9) | |

| Caucasian | 949 (86.5) | 71 (92.2) | 878 (86.1) | |

| Age | <0.0001 | |||

| Age <= 50yrs | 427(38.9) | 8 (10.4) | 419 (41.1) | |

| Age > 50yrs | 670 (61.1) | 69 (89.6) | 601 (58.9) | |

| Education | 0.0007 | |||

| High school or less | 394 (35.9) | 43 (55.8) | 351 (34.4) | |

| College/vocational school | 571 (52.1) | 29 (37.7) | 542 (53.1) | |

| Post graduate studies | 132 (12.0) | 5 (6.5) | 127 (12.5) | |

| Income | 0.0012 | |||

| Less than or equal to $30,000 | 637 (58.1) | 55 (71.4) | 582 (57.1) | |

| More than $30,000 | 431 (39.3) | 17 (22.1) | 414 (40.6) | |

| Don’t know/Refused | 29 (2.6) | 5 (6.5) | 24 (2.3) | |

| Marital status | 0.0315 | |||

| Never Married | 83. (7.6) | 3 (3.9) | 70 (7.8) | |

| Currently Married | 667 (60.8) | 41 (53.2) | 626 (61.4) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 232 (21.1) | 18 (23.4) | 214 (21.0) | |

| Widowed | 115 (10.5) | 15 (19.5) | 100 (9.8) | |

| BMI | 0.2247 | |||

| Under weight | 8 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.8) | |

| Normal weight | 274 (25.0) | 14 (18.2) | 260 (25.5) | |

| Over weight | 317 (28.9) | 29 (37.7) | 288 (28.2) | |

| Obese | 498 (45.4) | 34 (44.1) | 464 (45.5) | |

| Diabetes | 0.0057 | |||

| No | 753 (68.6) | 42 (54.5) | 711 (69.7) | |

| Yes | 344 (31.4) | 35 (45.5) | 309 (30.3) | |

| High blood pressure | 0.7839 | |||

| No | 343 (31.3)) | 23 (29.9) | 320 (31.4) | |

| Yes | 754 (68.7) | 54 (70.1) | 700 (68.6) | |

| High cholesterol | 0.0476 | |||

| No | 415 (37.8) | 21 (27.3) | 394 (38.6) | |

| Yes | 682 (62.2) | 56 (72.7) | 626 (61.4) | |

| Smoker | 0.8197 | |||

| No | 880 (80.2) | 61 (79.2) | 819 (80.3) | |

| Yes | 217 (19.8) | 16 (20.8) | 201 (19.7) | |

| Exposed to second hand smoke | 0.4743 | |||

| No | 276 (25.2) | 22 (28.6) | 254 (24.9) | |

| Yes | 821 (74.8) | 55 (71.4) | 766 (75.1) | |

| Physical activity | 0.0312 | |||

| No | 554 (50.5) | 48 (62.34) | 506 (49.6) | |

| Yes | 543 (49.5) | 29 (37.7) | 514 (50.4) | |

| Menopause | 0.0212 | |||

| No | 622 (56.7) | 34 (44.2) | 588 (57.7) | |

| Yes | 475 (43.3) | 43 (55.8) | 432 (42.3) | |

| Family History | ||||

| No | 19 (1.7) | 1 (1.3) | 18 (1.8) | |

| Yes | 1076 (98.1) | 75 (97.4) | 1001 (98.1) | |

| Don’t know | 2 (0.2) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0.0563 |

Comparison of characteristics of women who experienced a cardiac event and of those who did not.

Predictive utility of cumulative MAPMISS PS scores and PS counts

To determine whether cumulative MAPMISS PS scores and total PS counts were significantly associated with the occurrence of cardiac events, controlling for known clinical and sociodemographic risk factors, we first entered the cumulative PS score, computed as the sum of individual PS scores (range: 0–630), as a predictor. Results were similar whether we adjusted for race and age only or for all the covariates listed in Table 2. After adjusting for all covariates, the HR for subsequent occurrence of a cardiac event increased by 10% for every 10-unit increase in the cumulative prodromal score (HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.06–1.13). The total PS count, that is, the number of PS endorsed by each woman at each visit (range: 0–30), was also significantly associated with risk of a subsequent cardiac event. After adjusting for all covariates, the HR increased by approximately 17% for every additional PS reported (HR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.13–1.21).

The most predictive PS subsets

Since both the MAPMISS cumulative PS scores and total PS counts were predictive of subsequent cardiac events, we explored individual PS data to identify the most parsimonious models for predicting cardiac events. We again began by examining PS scores incorporating symptom intensity and frequency, and then looked at the simpler measures of symptom presence/absence.

PS scores

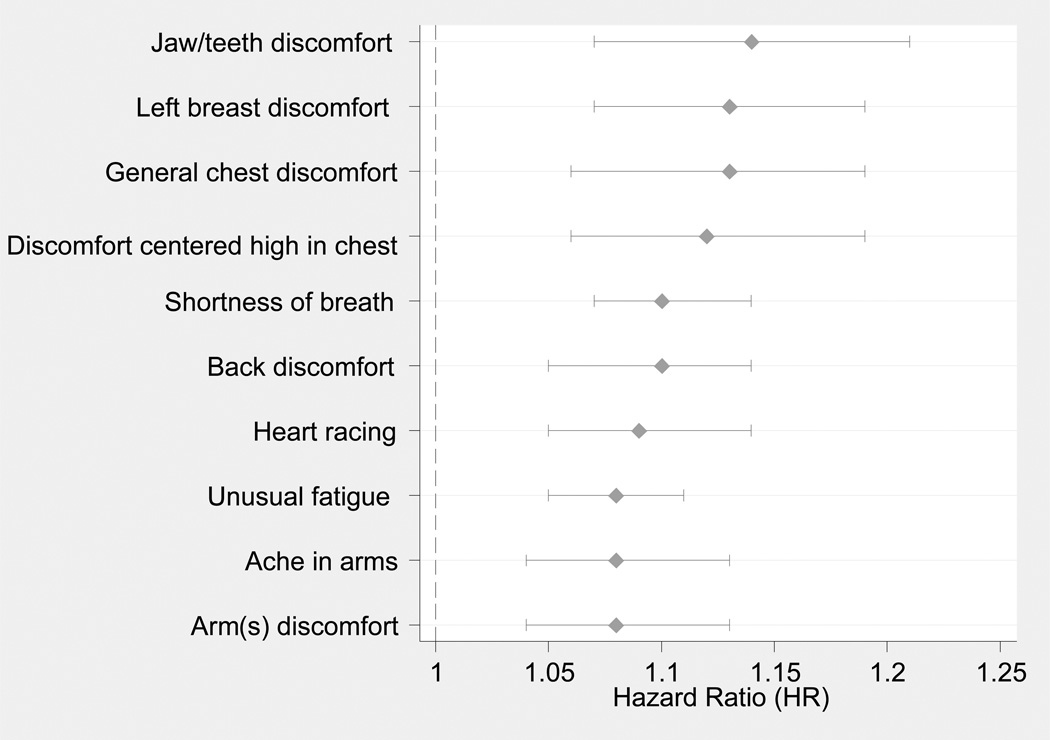

We looked at the relationships between each of the 30 individual PS scores and the risk of a cardiac event, first adjusted for age and race only, and then for all covariates. The HRs and 95% CIs from these analyses are shown in Table 3. Estimates obtained after adjusting for all covariates were similar to those obtained after adjusting for age and race only. Figure 1 illustrates the adjusted HRs and CIs for the 10 PS with the highest HRs based on individual PS scores.

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for individual prodromal symptom scores modeled independently

| Symptom | HR (95% CI)* | HR (95% CI)† | p value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shortness of breath | 1.12 (1.08, 1.15) | 1.10 (1.07, 1.14) | <.0001 |

| Unusual fatigue | 1.09 (1.06, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.05, 1.11) | <.0001 |

| Left breast discomfort | 1.13 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | <.0001 |

| Back discomfort | 1.10 (1.06, 1.14) | 1.10 (1.05, 1.14) | <.0001 |

| Jaw/teeth discomfort | 1.14 (1.08, 1.21) | 1.14 (1.07, 1.21) | <.0001 |

| Heart racing | 1.09 (1.05, 1.14) | 1.09 (1.05, 1.14) | <.0001 |

| General chest discomfort | 1.11 (1.05, 1.18) | 1.13 (1.06, 1.19) | <.0001 |

| Centered high in chest discomfort |

1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.19) | <.0001 |

| Ache in arms | 1.10 (1.05, 1.14) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | <.0001 |

| Arm(s) discomfort | 1.09 (1.05, 1.14) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 0.0003 |

| Arms tingling | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) | 0.0063 |

| Cough | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.11) | 0.0067 |

| Neck/throat discomfort | 1.07 (1.01, 1.12) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.13) | 0.0083 |

| Hands tingling | 1.07 (1.02, 1.11) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.10) | 0.0090 |

| Arms weak/heavy | 1.07 (1.03, 1.12) | 1.06 (1.02, 1.12) | 0.0094 |

| Headaches frequency change | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) | 0.0252 |

| Top of shoulder discomfort | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) | 0.0402 |

| Sleep disturbance | 1.05 (1.01, 1.08) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 0.0541 |

| Legs aching | 1.05 (1.01, 1.09) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | 0.0578 |

| Difficulty breathing at night | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) | 0.0586 |

| Vision blurry, changes | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) | 0.0639 |

| Change in thinking | 1.06 (1.02, 1.11) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09) | 0.0643 |

| Arms numb | 1.06 (1.01, 1.12) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) | 0.0690 |

| Frequent indigestion | 1.06 (1.02, 1.10) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.08) | 0.1032 |

| Headaches intensity change | 1.06 (1.01, 1.12) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 0.1222 |

| Dizziness | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) | 0.1844 |

| Anxious | 1.12 (1.08, 1.15) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 0.2093 |

| Abdominal discomfort/pain | 1.09 (1.06, 1.12) | 1.02 (0.95, 1.09) | 0.5990 |

| Loss of appetite | 1.13 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) | 0.7134 |

| Right side chest discomfort | 1.10 (1.06, 1.14) | 0.95 (0.68, 1.32) | 0.7491 |

Adjusted for age and race only

Adjusted for all variables listed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the 10 prodromal symptoms with the highest HRs based on individual prodromal symptom scores. Hazard ratios adjusted for all covariates in Table 2

We then constructed a parsimonious model taking the individual PS scores for all symptoms into consideration and retaining all covariates listed in Table 2. The adjusted HRs and the corresponding 95% CIs estimated from this Cox proportional hazards model are shown in Table 4. Three symptoms were significantly associated with increased risk of a cardiac event whether we adjusted for all covariates or for age and race only: general chest discomfort, shortness of breath and unusual fatigue. The C-statistics and thus the predictive ability of these models were high (0.78 when adjusted for age and race only and 0.82 when adjusted for all covariates).

Table 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for retained symptoms and significant covariates in the parsimonious model based on individual prodromal symptom scores

| HR (95% CI)* | HR (95% CI)† | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | |||

| General chest | 1.08 (1.01, 1.14) | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | 0.0058 |

| Shortness of breath | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) | 0.0015 |

| Unusual fatigue | 1.06 (1.02, 1.09) | 1.05 (1.01, 1.08) | 0.0091 |

| Significant covariates | |||

| Age | 1.05 (1.04, 1.07) | 1.07 (1.05, 1.10) | <0.0001 |

| BMI | |||

| 18.5−24.9 | Reference | ||

| 25 −29.9 | 2.05 (1.04, 4.03) | 0.0374 | |

| ≥ 30 | 2.01 (1.01, 3.98) | 0.0469 | |

| Hypertension | 0.52 (0.31, 0.90) | 0.0190 | |

| Diabetes | 1.78 (1.10, 2.89) | 0.0193 | |

| Harrell’s C (95% C.I) | 0.78 (0.73, 0.83) | 0.82 (0.77, 0.86) |

Adjusted for age and race only

Adjusted for all variables listed in Table 2

PS presence/absence

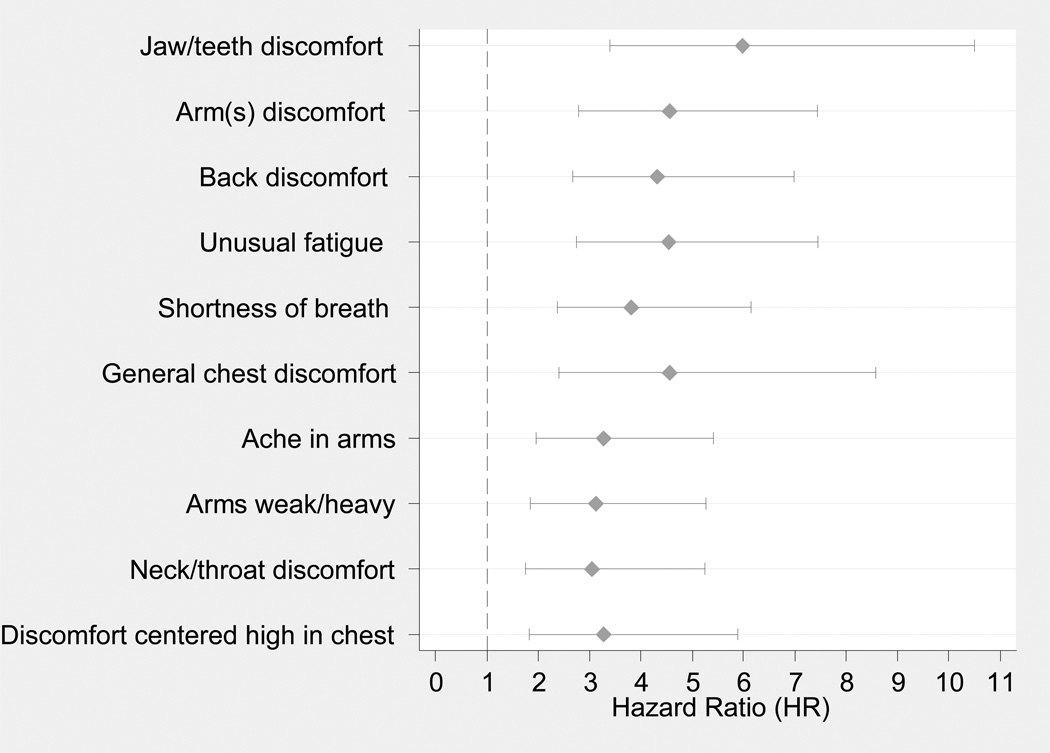

Again, we first modeled each of the 30 PS individually, adjusting for age and race only and then for all covariates. The HRs and 95% CIs from these analyses are shown in Table 5. Estimates adjusted for all covariates were similar to estimates adjusted for age and race only. Figure 2 shows the HRs and CIs for the 10 PS with the highest HRs based on individual symptom occurrence (presence/absence).

Table 5.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for presence/absence of each prodromal symptom modeled independently

| Symptom | HR (95% CI)* | HR (95% CI)† | p value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jaw/teeth discomfort | 6.07 (3.52, 10.45) | 5.98 (3.4, 10.51) | <.0001 |

| Arm(s) discomfort | 5.15 (3.20, 8.28) | 4.55 (2.78, 7.44) | <.0001 |

| Back discomfort | 4.32 (2.70, 6.90) | 4.32 (2.67, 6.99) | <.0001 |

| Unusual fatigue | 4.90 (3.02, 7.94) | 4.53 (2.75, 7.45) | <.0001 |

| Shortness of breath | 4.22 (2.68, 6.67) | 3.81 (2.37, 6.15) | <.0001 |

| General chest discomfort | 4.22 (2.27, 7.83) | 4.55 (2.41, 8.57) | <.0001 |

| Ache in arms | 3.54 (2.16, 5.78) | 3.26 (1.96, 5.41) | <.0001 |

| Arms weak/heavy | 3.52 (2.15, 5.76) | 3.12 (1.85, 5.26) | <.0001 |

| Neck/throat discomfort | 2.88 (1.69, 4.90) | 3.04 (1.76, 5.24) | <.0001 |

| Centered high in chest discomfort | 3.45 (1.93, 6.16) | 3.27 (1.82, 5.88) | <.0001 |

| Left breast discomfort | 3.23 (1.93, 5.42) | 2.91 (1.70, 4.97) | <.0001 |

| Hands tingling | 2.82 (1.73, 4.60) | 2.66 (1.61, 4.40) | 0.0001 |

| Cough | 3.06 (1.79, 5.22) | 2.84 (1.64, 4.93) | 0.0002 |

| Arms tingling | 2.97 (1.70, 5.17) | 2.71 (1.53, 4.80) | 0.0006 |

| Anxious | 2.35 (1.44, 3.81) | 2.23 (1.36, 3.66) | 0.0016 |

| Change in thinking | 2.60 (1.56, 4.32) | 2.32 (1.37, 3.92) | 0.0017 |

| Arms numb | 3.00 (1.66, 5.42) | 2.56 (1.39, 4.71) | 0.0024 |

| Sleep disturbance | 2.12 (1.33, 3.39) | 2.09 (1.30, 3.38) | 0.0025 |

| Top of shoulder discomfort/pain | 2.79 (1.55, 5.01) | 2.53 (1.37, 4.67) | 0.0029 |

| Dizziness | 2.55 (1.55, 4.21) | 2.16 (1.28, 3.63) | 0.0038 |

| Difficulty breathing at night | 3.34 (1.76, 6.35) | 2.73 (1.38, 5.39) | 0.0040 |

| Legs aching | 2.56 (1.51, 4.34) | 2.26 (1.29, 3.95) | 0.0042 |

| Vision blurring, changes | 2.31 (1.22, 4.40) | 2.56 (1.32, 4.94) | 0.0053 |

| Frequent indigestion | 2.42 (1.45, 4.04) | 2.02 (1.18, 3.45) | 0.0098 |

| Headaches frequency change | 2.40 (1.40, 4.13) | 2.09 (1.18, 3.70) | 0.0116 |

| Heart racing | 1.93 (1.19, 3.11) | 1.75 (1.07, 2.86) | 0.0267 |

| Headaches intensity change | 2.35 (1.24, 4.47) | 2.05 (1.04, 4.03) | 0.0372 |

| Right side chest discomfort | 2.27 (0.83, 6.22) | 1.76 (0.63, 4.95) | 0.2811 |

| Loss of appetite | 1.59 (0.81, 3.09) | 1.36 (0.69, 2.72) | 0.3755 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 1.51 (0.72, 3.14) | 1.40 (0.66, 2.95) | 0.3786 |

Adjusted for age and race only

Adjusted for all variables listed in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the 10 prodromal symptoms with the highest HRs estimated from data on presence/absence of symptom. Hazard ratios adjusted for all covariates in Table 2.

We then constructed a parsimonious model taking all symptoms into consideration and retaining all covariates listed in Table 2. The adjusted HRs and corresponding 95% CIs for the retained PSs estimated from this parsimonious Cox proportional hazards model are presented in Table 6. When we adjusted for race and age only, four symptoms were significantly associated with increased risk of a cardiac event: discomfort in jaws/teeth, unusual fatigue, discomfort in arms, and shortness of breath. Women reporting one or more of these symptoms were over 4 times as likely to suffer an adverse cardiac event as women with none of these four symptoms (HR = 4.19, 95% CI = 2.63–7.44). When we added the other Table 2 covariates to the model, general chest discomfort was significantly associated with increased risk, along with the other four symptoms. Women reporting one or more of these symptoms were almost 4 times as likely to suffer an adverse cardiac event as women with none of these five symptoms (HR = 3.97, 95% CI = 2.32–6.78). The C-statistics and thus the predictive ability for these models was also high (0.81 when adjusted for age and race only and 0.84 when adjusted for all covariates).

Table 6.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for retained symptoms and significant covariates in the parsimonious model based on presence/absence of symptom

| HR (95% CI)* | HR (95% CI)† | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | |||

| Jaw/teeth discomfort | 2.52 (1.40, 4.55) | 2.76 (1.49, 5.11) | 0.0012 |

| Unusual fatigue | 2.57 (1.47, 4.47) | 2.34 (1.33, 4.14) | 0.0033 |

| Arm(s) discomfort | 2.44 (1.44, 4.12) | 2.15 (1.25, 3.70) | 0.0057 |

| Shortness of breath | 2.00 (1.19, 3.36) | 1.87 (1.11, 3.16) | 0.0185 |

| General chest discomfort | 2.26 (1.15, 4.45) | 0.0180 | |

| Significant covariates | |||

| Age | 1.06 (1.04, 1.08) | 1.07 (1.05, 1.10) | <0.0001 |

| BMI | |||

| 18.5−24.9 | Reference | ||

| 25 −29.9 | 2.13 (1.08, 4.19) | 0.0291 | |

| ≥ 30 | 2.02 (1.02, 4.01) | 0.0443 | |

| Hypertension | 0.50 (0.29, 0.88) | 0.0151 | |

| Diabetes | 1.70 (1.04, 2.76) | 0.0335 | |

| Physical activity | 0.61 (0.38, 0.99) | 0.0447 | |

| Second hand smoke | 0.57 (0.34, 0.97) | 0.0388 | |

| Harrell’s C (95% C.I) | 0.81 (0.77, 0.86) | 0.84 (0.80, 0.89) |

Adjusted for age and race only

Adjusted for all variables listed in Table 2

In order to better understand the nature of the chest discomfort reported by some of the women, we examined the sensations/descriptors associated with this discomfort (Table 7). Of the 1097 women in the study, 620 (57%) endorsed having chest discomfort in any one of the four chest symptom locations at any time during follow-up. The four chest locations were left chest, general chest, right chest, and centered high in the chest. Interestingly, although the difference was not statistically significant, women with subsequent events endorsed having chest discomfort less frequently (49%) than women without subsequent events (57%) (p=0.19). Among women who did not experience an event but who endorsed chest discomfort as a symptom, the majority described the discomfort as pressure (45%), tightness (29%) or sharpness (28%). In contrast, the women who experienced an event and reported chest discomfort described it primarily as either pressure (47%) or tightness (26%). We also examined discomfort in the back, between the shoulder blades. Back discomfort at any time during follow-up was endorsed by 526 of the 1097 women in the study (48%). Women without subsequent events endorsed back discomfort more often (49%) than women with subsequent events (39%) (p=0.10).

Table 7.

Counts and percentages of women experiencing specific sensations among 620 women endorsing chest discomfort during the study

| Sensation | No Events (n= 582) |

Events (n= 38) |

Total (n=620) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ache | 170 (29.2%) | 7 (18.4%) | 177 (28.5%) |

| Burning | 60 (10.3%) | 5 (13.2%) | 65 (10.5%) |

| Crushing | 51 (8.8%) | 4 (10.5%) | 55 (8.9%) |

| Fullness | 86 (14.8%) | 5 (13.2%) | 91 (14.7%) |

| Heat | 9 (1.5%) | - | 9 (1.5%) |

| Pressure | 260 (44.7%) | 18 (47.4%) | 278 (44.8%) |

| Sharpness | 164 (28.2%) | 8 (21.1%) | 172 (27.7%) |

| Soreness | 47 (8.1%) | 3 (7.9%) | 50 (8.1%) |

| Spasm | 49 (8.4%) | 4 (10.5%) | 53 (8.5%) |

| Tightness | 169 (29.0%) | 10 (26.3%) | 179 (28.9%) |

| Tingling | 41 (7.0%) | 4 (10.5%) | 45 (7.3%) |

DISCUSSION

Models for prediction of heart disease have been in use for many decades, but they lack specificity and sensitivity for women, making it difficult for clinicians to know which risk model to use for routine screening. A recent article examined the accuracy of the most commonly used prediction models in women in the United States and concluded that many questions remain and it is unclear how to use these models to make treatment decisions.25 Models such as Framingham9,26 and the Reynolds Risk score have been useful in calculating long-term risk, and current efforts are underway to add additional biomarkers to improve cardiovascular risk prediction.9,26–31 However, the 10 Q Report: Advancing Women’s Heart Health through Improved Research, Diagnosis and Treatment, and others, concluded that lack of sufficient numbers of women and gender-specific analysis in clinical trials make it difficult for clinicians to know how to adequately assess a woman’s risk of CHD or to modify this risk.32,33 This report also emphasized the need to identify symptoms other than chest pain that may be suggestive of CHD in women. Our study identified specific symptoms that were predictive of progression to a cardiac event in a sample of women followed over a 2-year period who did not have a CHD diagnosis at the time of enrollment into the study.

This study demonstrated the predictive utility of the PS section of the MAPMISS instrument. Both MAPMISS cumulative PS scores and total PS counts were significantly associated with subsequent development of a cardiac event among women, independent of traditional risk factors. After adjustment for clinical and socio-demographic characteristics, the risk of a cardiac event increased approximately 10% for every 10-unit increase in the cumulative MAPMISS PS score and approximately 17% for every additional PS reported. The latter finding may be especially useful in the clinical setting because it is quicker and easier to count symptoms endorsed than to score and sum PS intensity and frequency. Further, presence/absence reports are also likely to be less vulnerable than estimates of symptom intensity to individual differences, including symptom tolerance. This is important since it is unlikely that additional assessments will be incorporated into a clinical practice or prediction rule unless they minimally increase workload and do not bring additional expense.34 Assessment of individual symptoms included in the MAPMISS is easy to administer (yes/no) and adds minimal time and expense during a clinical encounter.

In the present study, we also looked at which symptoms and symptom scores were most predictive of a subsequent cardiac event. Even after adjusting for known clinical and socio-demographic risk factors, women who reported one or more of the following symptoms were approximately 4 times as likely to suffer an adverse cardiac event as women reporting none of the symptoms (HR = 3.97, 95%CI = 2.32–6.78): discomfort in jaws/teeth, unusual fatigue, discomfort in arms, general chest discomfort, and shortness of breath. This suggests that a subset of MAPMISS PS items may provide a useful screen for primary care clinicians considering whether to refer women for additional cardiac work-up and provide key information to inform clinical management decisions. However, it is essential that this subset undergo further testing in primary-care samples to confirm its usefulness in identifying women with early symptoms most indicative of CHD in need of further evaluation. The literature highlights the importance of identifying symptoms predictive of CHD in women.32,33 Only future research in primary-care populations can determine whether the subset of MAPMISS symptoms identified in this study can meet this need.

Historically, chest pain has been considered the signature indicator of CHD. Interestingly, in our study, women who did not experience a cardiac event were more likely to report chest discomfort or pain in one or more sites (right, left, high, general) than women who had such an event. This highlights the need for clinicians to consider a wider spectrum of symptoms than just chest pain or discomfort, especially unusual fatigue, discomfort in jaws/teeth and shortness of breath, when evaluating women for risk of progressing to a CHD event. Although, there is increasing awareness that women commonly experience symptoms other than or in addition to chest pain or discomfort, this study is the first to identify specific PS that are predictive of subsequent cardiac events. The results indicate these symptoms might precede an acute MI by weeks or months and should be useful to both clinicians and women. Earlier recognition of symptoms should contribute to decreasing MI-associated mortality rates in women.

Limitations

In addition to its many strengths (sample size, sample diversity, two-year longitudinal design), the study had several limitations. Data were based on self-report, making them vulnerable to recall bias. To minimize the risk of recall bias, we employed a short (3-month) follow-up interval, worded questions simply, and, if the RA noted any hesitation in the participant’s response(s), re-phrased the question. Also, throughout the interview, the RAs frequently verified participants’ understanding of MAPMISS items. Additionally, the SBT cognitive screen was administered at baseline and again at 12 months in order to decrease the influence of change in cognitive status. None of the participants scored >16 (i.e., positive for cognitive impairment) on the SBT at 12 months. Individuals may also differ in their perceptions of symptom severity and, consciously or unconsciously, could exaggerate or minimize their reports of symptom severity or frequency. Therefore, with the participants’ informed consent, we audited their medical records over the 2-year period, to verify the information they provided. No discrepancies were noted. Finally, although we had sufficient overall power, subgroup analysis was limited by the relatively small number of events observed. Future studies with a greater number of events would enable additional subgroup analyses.

Conclusions

The devastating impact of CHD is largely preventable if the condition is diagnosed early in the disease process. Instruments to facilitate early identification of high-risk individuals are vitally important. This need is especially great for women who often present with a variety of symptoms. This study demonstrated that a valid and reliable symptom instrument, the MAPMISS, can be used by clinicians in assessing women’s CHD risk. Using the MAPMISS, this study identified specific PS that are predictive of future cardiac events. We observed that women who reported one or more of five of the MAPMISS PS items: 1) discomfort in jaws/teeth, 2) unusual fatigue, 3) discomfort in arms, 4) general chest discomfort, or 5) shortness of breath, were four times as likely to suffer an adverse cardiac event as women reporting none of those symptoms. Informing clinicians and women of the implications of these symptoms could contribute to early detection and initiation of treatment to prevent or delay progression to a cardiac event. This in turn could assist in reducing the high disability and mortality rates in women associated with acute MI.

What’s New?

Over 240,000 women die from coronary heart disease annually in the U.S.

Identifying symptoms that predict coronary heart disease events in women could decrease mortality

The McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey (MAPMISS) may be useful in predicting coronary events in women

Acknowledgements

None

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: J. McSweeney received a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (1 RO1 NR04908). C. Pettey received a fellowship award from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (1 F31 NR012347). For the remaining authors none were declared.

Contributor Information

Jean McSweeney, Professor and Associate Dean for Research, College of Nursing, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR.

Mario A. Cleves, Professor, College of Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR.

Ellen P. Fischer, Research Health Scientist, Center for Mental Healthcare and Outcomes Research, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System and Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Science, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR.

Debra K. Moser, Professor and Gill Endowed Chair, College of Nursing, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY.

Jeanne Wei, Professor, College of Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR.

Christina Pettey, Doctoral Candidate, Clinical Assistant Professor, College of Nursing, University of Arkansas Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR.

Martha O. Rojo, Doctoral Student and Research Assistant, College of Nursing, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR.

Narain Armbya, Statistician, College of Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR.

References

- 1.Wenger NK. Women and coronary heart disease: a century after herrick: understudied, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Circulation. 2012;126(5):604–611. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.086892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2012 Update. Circulation. 2012;125:e12–e230. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed June 23, 2012];Comparative Effectiveness Review Noninvasitve Technologies for the Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Disease in Women. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/202/1132/CER58_Diagnosis-CAD-in-Women_ExecutiveSummary_20120607.pdf Published June 7, 2012. [PubMed]

- 4.Romeo K. The female heart: physiological aspects of cardiovascular disease in women. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1995;14(4):170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain. JAMA. 2000;283(24):3223–3229. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.24.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Chandra NC. Differences in men and women in heart attack treatments and outcomes are not explained by insurance status [abstract] [Accessed July 7, 2003];AHRQ research activities. 2002 263:3–4. http://www.ahrq.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canto JG, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, et al. Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: myth vs reality. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2405–2413. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Agostino RB, Pencina MJ. Invited commentary: clinical usefulness of the Framingham cardiovascular risk profile beyond its statistical performance. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(3):187–189. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook NR, Paynter NP, Eaton CB, et al. Comparison of the Framingham and Reynolds Risk Scores for Global Cardiovascular Risk Prediction in the Multiethnic Women's Health Initiative. Circulation. 2012;125(14):1748–1756. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.075929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McSweeney JC, Cody M, O'Sullivan P, Elberson K, Moser DK, Garvin BJ. Women's early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108(21):2619–2623. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097116.29625.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham MM, Westerhout CM, Kaul P, Norris CM, Armstrong PW. Sex differences in patients seeking medical attention for prodromal symptoms before an acute coronary event. Am Heart J. 2008;156(6):1210–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McSweeney JC, Cleves MA, Zhao W, Lefler LL, Yang S. Cluster analysis of women's prodromal and acute myocardial infarction symptoms by race and other characteristics. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(4):311–322. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181cfba15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McSweeney JC, O'Sullivan P, Cleves MA, et al. Racial differences in women's prodromal and acute symptoms of myocardial infarction. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(1):63–73. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McSweeney JC, O'Sullivan P, Cody M, Crane PB. Development of the McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19(1):58–67. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McSweeney JCM, Fischer E, Rojo MAN, Moser D. Reliability of the McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey among Black and White Women [Published online ahead of print October 8, 2012]f. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1474515112459989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ball LJ, Bisher GB, Birge SJ. A simple test of central processing speed: an extension of the Short Blessed Test. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(11):1359–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(6):734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkins CH, Wilkins KL, Meisel M, Depke M, Williams J, Edwards DF. Dementia undiagnosed in poor older adults with functional impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1771–1776. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shtatland ES, Kleinman K, Cain EM. A new strategy of model building in PROC LOGISTIC with automatic variable selection, validation, shrinkage, and model averaging. 2004:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shtatland ES, Kleinman K, Cain EM. Model building in proc phreg with automatic variable selection and information criteria. 2005:206–230. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrell FE, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluation the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247(18):2543–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB. Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Stat Med. 2004;23(13):2109–2123. doi: 10.1002/sim.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.STATA [computer program]. Version 12.0. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAS [computer program]. Version 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Instuite Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michos ED, Blumenthal RS. How accurate are 3 risk prediction models in US women? Circulation. 2012;125(14):1723–1726. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.099929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Agostino RB, Ramachandran S, Vasan RS, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzoulaki I. Assessment of claims of improved prediction beyond the framingham risk score. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(21):2345–2352. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N, Cook NR. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA. 2007;297(6):611–619. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arant CB, Wessel TR, Ridker PM, et al. Multimarker approach predicts adverse cardiovascular events in women evaluated for suspected ischemia: results from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(5):244–250. doi: 10.1002/clc.20454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelter MM, Riegel B, McKinley S, et al. Are there symptom differences in patients with coronary artery disease presenting to the emergency department ultimately diagnosed with or without acute coronary syndrome? Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(9):1822–1828. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meisel ZF, Armstrong K, Mechem CC, et al. Influence of sex on the out-of-hospital management of chest pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(1):80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenger NK. Cardiovascular Disease: The Female Heart Is Vulnerable. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(3):134–135. doi: 10.1002/clc.21972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes SN, Wenger NK, Greenberger P. The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease. Washington DC: 10Q Report: advancing women’s heart health through improved research, diagnosis and treatment; [Accessed January 16, 2012]. http://www.womenheart.org/documents/upload/10Q–FINAL-REVISED-6-28-11.pdf. Published June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grady D. Why is a good clinical prediction rule so hard to find? Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(19):1701–1702. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]