Abstract

Little is known about the process by which children disclose adult wrongdoing, a topic of considerable debate and controversy. In the present study, we investigated children’s evaluations of disclosing adult wrongdoing by focusing on children’s preferences for particular disclosure recipients and perceptions of the consequences of disclosure in hypothetical vignettes. We tested whether children thought disclosure recipients would believe a story child as a truth-teller and what actions the recipients would take against the “instigator” who committed the transgression. Maltreated and non-maltreated 4- to 9-year-olds (N = 235) responded to questions about vignettes that described a parent’s or stranger’s transgression. Older children preferred caregiver over police officer recipients when disclosing a parent’s, but not a stranger’s, transgression. Maltreated children’s preference for caregiver over police recipients developed more gradually than that of non-maltreated children. Older children expected disclosure recipients to be more skeptical of the story child’s account, and older children and maltreated children expected disclosure recipients to intervene formally less often when a parent rather than stranger was the instigator. Results contribute to understanding vulnerable children’s development and highlight the developmental, experiential, and socio-contextual factors underlying children’s disclosure patterns.

Keywords: disclosure, adult transgression, child maltreatment

In recent years, increased attention has focused on understanding the process by which children disclose negative prior experiences, particularly maltreatment perpetrated by adults to whom children are closely related (London, Bruck, Wright, & Ceci, 2008; Lyon, Ahern, Malloy, & Quas, 2010; Pipe, Lamb, Orbach, & Cederborg, 2007). Much of this attention stems from evidence indicating that children often delay disclosing maltreatment, fail to provide complete details about their maltreatment experiences, and sometimes retract prior allegations, all of which can profoundly affect the believability of children’s claims and the outcome of legal proceedings. In order to intervene effectively and protect child victims, it is imperative to determine why children decide to disclose and what influences their decisions. More generally, it is important to understand how children reveal negative acts and the transgressions of others, including developmental changes and experiential and socio-contextual influences on that understanding.

The overarching purpose of the current study was to investigate the factors underlying children’s decisions to disclose adult wrongdoing. We were specifically interested in children’s perceptions of how disclosure recipients (individuals to whom disclosure may occur) would react to a story child’s disclosure of an adult’s wrongdoing, whether children’s perceptions vary depending on a story child’s relationship to the instigator (individual who committed the wrongdoing), and whether children’s attitudes are related to their age and history of substantiated maltreatment. Surprisingly few studies have examined children’s expectations concerning disclosure of adult wrongdoing directly, and even fewer have focused on maltreated children, a group of great interest for theoretical reasons and generalizability purposes. The current study helps to fill an important gap by focusing on to whom children prefer to disclose and their expectations concerning the consequences of disclosure.

As we review next, a sizeable body of work has examined secrecy and nondisclosure in children, using both naturalistic designs and experimental procedures. Findings reveal that children are often reluctant to disclose wrongdoing; that reluctance is related both to children’s relationship to the instigator and expectations concerning how disclosure recipients will react to disclosure; and that children’s developmental level may influence their expectations. Finally, findings suggest that having a history of maltreatment may be related to children’s expectations that recipients will react negatively to disclosure.

First, evidence indicates that children are often reluctant to disclose wrongdoing that they have witnessed or experienced. As mentioned, naturalistic studies indicate that many children delay reporting abuse for substantial periods of time, months or even years (Goodman-Brown, Edelstein, Goodman, Jones, & Gordon, 2003; London et al., 2008; Malloy, Brubacher, & Lamb, 2011), and that children sometimes recant former disclosures (Elliott & Briere, 1994; Malloy, Lyon, & Quas, 2007). Nondisclosure also appears in laboratory analogue studies, with children commonly failing to disclose their own transgressions (Bussey, Lee, & Grimbeek, 1993; Lewis, Stanger, & Sullivan, 1989; Polak & Harris, 1999; Talwar, Gordon, & Lee, 2007; Talwar & Lee, 2002; Talwar, Lee, Bala, & Lindsay, 2002), the transgressions of others (Bottoms, Goodman, Schwartz-Kenney, & Thomas, 2002; Bussey & Grimbeek, 1995; Ceci & Leichtman, 1992; Pipe & Wilson, 1994; Talwar, Lee, Bala, & Lindsay, 2004), and transgressions in which they are jointly implicated (Lyon & Dorado, 2008; Lyon, Malloy, Quas, & Talwar, 2008).

Second, consistent with principles of classic social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), a primary motivation for secrecy among children is to avoid punishment (Last & Aharoni-Etzioni, 1995). As such, whether children disclose an adult’s wrongdoing is likely related to the outcomes they expect for disclosing (Bussey & Greembeek, 1995). Wagland and Bussey (2005) tested this possibility by asking 5- to 10-year-olds about disclosure likelihood in relation to vignettes describing minor transgressions. Children, not surprisingly, predicted less disclosure when there were warnings not to tell and expectations that disclosure would lead to punishment. These findings are consistent with retrospective surveys of disclosure in adults victimized as children. Adults often report that their decisions regarding whether to disclose were affected by fears or expectations about others’ reactions (e.g., disbelief, blame) and the effects of disclosure on themselves and others (Anderson, et al., 1993; Fleming, 1997). These surveys are limited by the dangers of reappraisal or forgetting, but similar reasons for delays in disclosure have been given by child victims across a wide age range (Goodman-Brown et al., 2003; Hershkowitz, Lanes, & Lamb, 2007; Malloy et al., 2011; Sas & Cunningham, 1995). Surveys (of adults or children) are necessarily limited to those who ultimately disclosed. Without questioning children who were never abused, the extent to which the former’s attitudes are shaped by their maltreatment experiences remains unknown. It is imperative that field work examining victims’ perceptions of the consequences of disclosure be complemented with experimental investigations.

One other important issue regarding children’s motivation to disclose concerns their relationship to the individual who committed the wrongdoing. Because of children’s attachment to and dependency on known and trusted adults, children may be particularly disinclined to disclose parental wrongdoing. Numerous studies have demonstrated that children are less likely to disclose and more likely to delay disclosing abuse by family members (see reviews in London et al., 2008; Lyon, 2002, 2007, 2009; Paine & Hansen, 2002), and more likely to recant when they have claimed abuse against a parent figure and their non-offending caregiver reacts in an unsupportive manner to disclosure (Elliott & Briere, 1994; Malloy et al., 2007). According to one laboratory study, 6- to 10-year-old children were less likely to disclose the transgressions of parents than other adults (Tye, Amato, Honts, Devitt, & Peters, 1999).

Third, deciding whether to disclose an act of wrongdoing requires recognition of the socio-motivational reasons why one might desire to conceal an event; such recognition likely varies developmentally. According to the social cognitive model of disclosure (Bussey & Grimbeek, 1995), children reason about the consequences of disclosure and are influenced by their cognitive capabilities and social experience, both of which increase with age and situational factors (e.g., instigator identity). For instance, relative to older children, younger children are less aware of the potential consequences of revealing secrets and transgressions (Bottoms et al., 2002; Bussey & Grimbeek, 1995; Polak & Harris, 1999; Talwar & Lee, 2002). Also, with age, children increasingly value secrecy as a component of friendship (Rotenberg, 1991; Rotenberg et al., 2004) and develop a more complex understanding of family loyalty, the latter of which includes the reciprocal nature of familial obligations (e.g., “owing” parents for care provided; Leibig & Green, 1999). Accordingly, older children may be more likely to recognize or predict negative consequences of disclosure than younger children, particularly when compared to those in the preschool-age years (e.g., Malloy et al., 2011).

Fourth, there are several reasons to suspect that a history of maltreatment may influence children’s expectations concerning how others, especially those who are closely related, will react to disclosure. Compared to non-maltreated children, maltreated children are less likely to trust that an adult will not cause them harm (Shields, Ryan, & Cicchetti, 2001), are more likely to expect others to behave antisocially (e.g., Dodge, Pettit, Bates, & Valente, 1995; Toth, Cicchetti, Macfie, Rogosch, & Maughan, 2000), and have more negative representations of caregivers (Toth, Cicchetti, Macfie, & Emde, 1997). Maltreated children also tend to interpret ambiguous situations as hostile and demonstrate hypersensitivity to negative emotions (Dodge et al., 1995; Pollak, Cicchetti, Hornung, & Reed, 2000). Therefore, maltreated children may be less protective of caregiver instigators and less trusting of caregiver disclosure recipients.

In what appears to be the first study of maltreated children’s evaluations of disclosing adult wrongdoing, Lyon et al. (2010) asked maltreated and non-maltreated 4- to 9-year-olds whether a child character in a series of brief vignettes would or should disclose a wrongdoing committed by an adult, with the vignettes varying the identities of the instigator and disclosure recipient. When asked what children would do, even the 4- to 5-year-olds predicted less disclosure against parent instigators than against stranger instigators, and when asked what children should do, children endorsed less disclosure of parents than strangers by age 6 to 7 years. Finally, when asked specifically about disclosing to police officers, with age, non-maltreated children grew increasingly protective of parent instigators, whereas the maltreated children showed no preference for protecting parent instigators from the police. Overall, the maltreated and non-maltreated children exhibited reverse age trends: the maltreated children endorsed more disclosure with age, and the non-maltreated children endorsed less.

Although the Lyon et al. (2010) study revealed the importance of considering both age and maltreatment history in assessing children’s attitudes about disclosing wrongdoing, several critical questions were left unanswered, most noteworthy those concerning the reasons underlying children’s disclosure patterns. In the current study, we expanded the Lyon et al. investigation by testing potential factors that underlie children’s disclosure patterns, focusing on children’s preferences regarding disclosure recipients and expectations concerning the consequences of disclosure, including whether children expected the disclosure recipient would believe a child as a truth-teller and how a recipient would react to disclosure (i.e., what actions the disclosure recipient would take against the instigator). To the extent that children consider the consequences of disclosure when deciding whether to disclose, asking them about their expectations of consequences can help us understand their decision making. Insight into children’s perceptions can provide novel information about when and to whom children elect to disclose transgressions. Such insight may also reveal why maltreated and non-maltreated children’s perceptions differ, and how children’s perceptions change across age.

The Present Study

In the study, 4- to 9-year-old maltreated and non-maltreated children answered questions about three types of vignettes that described a child character (story child) disclosing or potentially disclosing wrongdoing committed by an adult instigator to another adult recipient. In Recipient Preference vignettes, we assessed children’s perceptions of to whom the story child would choose to reveal a wrongdoing, given evidence from naturalistic studies that children typically first disclose maltreatment to caregivers (Arata, 1998; Sauzier, 1989). Second, because caregivers’ reactions have considerable implications for children’s subsequent disclosure patterns and adjustment (Elliott & Carnes, 2001; Lawson & Chaffin, 1992; Malloy et al., 2007), we asked about children’s expectations of belief and perceptions of the consequences of disclosing to caregiver disclosure recipients in Belief and Consequences vignettes. Across the vignettes, the instigator who committed the wrongdoing (parent v. stranger) and the recipient to whom the child would disclose (caregiver vs. police officer) were systematically varied to investigate how the story character’s relationship to these individuals influenced children’s perceptions. In addition, because children often fear being blamed by others for abuse, particularly when they believe they participated in, were complicit in, or deserved abuse (e.g., Feiring, Taska, & Lewis, 1998; Quas, Goodman, & Jones, 2003), the instigator was described in the vignettes as having made the child do “something really bad.”

Several hypotheses were advanced. First, with respect to the Recipient Preference vignettes, we hypothesized that when the instigator was a parent, children would prefer caregivers over police officers as disclosure recipients. (No such differences in recipient preferences were anticipated with stranger instigators). Older children were expected to be particularly likely to exhibit this bias because of their greater ability to reason about the consequences of disclosing to authority figures. We also anticipated that non-maltreated children would be more protective than maltreated children of a parent instigator and thus be less willing to select a police officer as a disclosure recipient than a caregiver as a disclosure recipient. Second, with respect to the Belief vignettes, we hypothesized that children would anticipate the recipient would tend to believe the story child as a truth-teller more when the instigator was described as a stranger than a parent, and that this difference would increase with age and be larger among the maltreated children. And third, with respect to the Consequences vignettes, we predicted that children would anticipate recipients’ reluctance to initiate formal intervention (i.e., involve legal authorities) when the instigator was a parent versus a stranger. Older children and maltreated children were expected to be particularly likely to distinguish between parent and stranger instigators in terms of predicting recipients’ reluctance to report to authorities - older children because of their greater awareness of the potentially negative consequences of disclosing transgressions, and maltreated children because of their beliefs that caregivers would be unsupportive.

Method

Participants

235 4- to 9-year-olds (M = 6 years, 7 months, SD = 1.65; 129 girls and 106 boys); 75 4–5 year olds, 78 6–7 year olds, and 82 8–9 year olds, approximately half maltreated (n = 107), served as participants. An additional 27 children (15 non-maltreated, 12 maltreated) failed to complete the task due to expressing desire to stop after the procedure began (n=4), uncommunicativeness (n=11), or interruption by school or court officials (n=6). For 6 children, the reason for termination was missing. Children were primarily from ethnic/racial minority backgrounds: 60% Latino, 28% African-American, 8% Caucasian, and 4% other. Neither ethnicity nor gender varied across age or between the maltreated and non-maltreated samples.

The maltreated sample consisted of children substantiated as having experienced neglect, emotional abuse, and/or physical or sexual abuse who had been removed from the custody of their parents or guardians. They were drawn from the Los Angeles County dependency court population, a court population which tends to be of disproportionately low socioeconomic status (Lyon & Saywitz, 1999). Because children had been removed from parental care, the Presiding Judge of Juvenile Court and the Los Angeles County Children’s Law Center granted consent for all children in the maltreated sample. Maltreated children were ineligible if they were awaiting an adjudication or contested disposition hearing on the date of testing (because they might be asked to testify), or if interpreter services were provided to their family and they were incapable of communicating with the researchers in English.

The non-maltreated sample consisted of children recruited from schools in nearby predominantly low-income ethnic minority neighborhoods, which were comparable to those from which a large majority of the maltreated children were removed (see similar approach in Pollak, Vardi, Putzer-Bechner, & Curtin, 2005). The non-maltreated children were drawn from schools in which 65% to 100% of children were considered economically disadvantaged, according to school records. Children not in the custody of one or both parents were excluded from the non-maltreated sample, because of the potential that they had been removed from their parents’ care due to maltreatment (see similar approach in Carrick, Quas, & Lyon, 2010; Lyon et al., 2010).

Materials

Vignettes

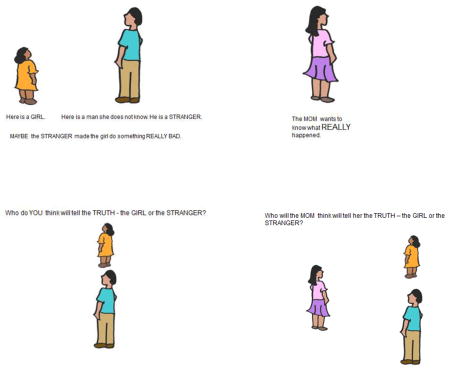

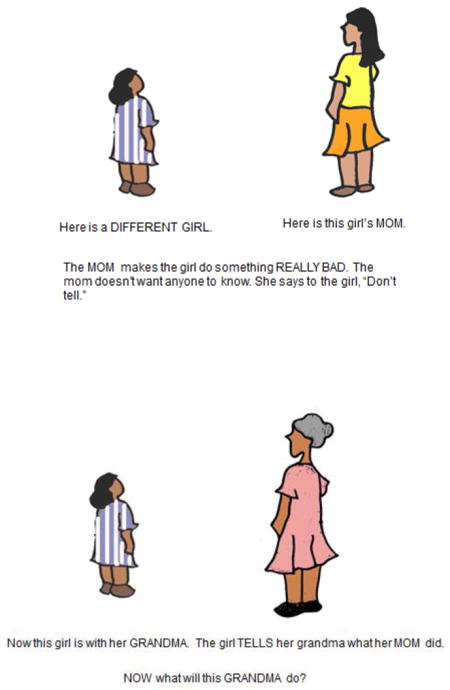

Three types of vignettes were included: Recipient Preference, Belief, and Consequences. All followed a similar format and included three characters, presented without facial expressions: an instigator, a disclosure recipient, and a story child who matched the participant’s sex. The instigators were the story child’s father, mother, or a stranger (the stranger was described as “a man [the story child] does not know”). The recipients were the story child’s mother, grandmother, or a policeman/woman. We did not test father recipients because they are rarely disclosure recipients (Anderson et al., 1993; Kogan, 2004), and because prior experimental work did not find different attitudes regarding mother and father recipients (Lyon et al., 2010). The characters had lightly shaded skin tones and were drawn without facial or hair features that would suggest a specific ethnicity. Physical positioning of the characters was counterbalanced. Sample vignettes are presented in Appendix A.

Five Recipient Preference vignettes assessed to whom children preferred to disclose wrongdoing. Children were told that the instigator made the story child do something really bad. The instigators were the father, the mother, or a stranger. Then, children were asked to choose which of two disclosure recipients the story child would tell about the wrongdoing. The recipient choices were mother/police officer or grandmother/police officer. Therefore, the five vignettes asked about a) a father instigator/mother or police officer recipient; b) father instigator/grandmother or police officer recipient; c) mother instigator/grandmother or police officer recipient; d) stranger instigator/mother or police officer recipient, and e) stranger instigator/grandmother or police officer recipient. An example of a vignette is: “Here is a girl. Here is her dad. The girl’s dad made the girl do something really bad. Who will this girl tell–her mom or a policeman?”

Five Belief vignettes tested children’s perceptions of whether a story child or an instigator would tell the truth about a possible wrongdoing and whether these perceptions varied depending on the story child’s relationship to the instigator. Children listened to vignettes in which an instigator may have done something “really bad,” and a potential disclosure recipient wants to know what happened. The instigator could be the father, the mother, or a stranger, and the recipient was either the mother or the grandmother. Therefore, the five vignettes asked about a) a father instigator/mother recipient; b) father instigator/grandmother recipient; c) mother instigator/grandmother recipient; d) stranger instigator/mother recipient, and e) stranger instigator/grandmother recipient. Children then answered questions about who the disclosure recipient would believe and who they themselves would believe, the story child or the instigator. An example of a vignette is: “Here is a girl. Here is her dad. Maybe the dad made the girl do something really bad. The mom wants to know what really happened.” Questions about who the disclosure recipient would believe and who the child believed (e.g., “Who does the mom think will tell the truth–the girl or the dad?” and “Who do you think will tell the truth–the girl or the dad?”) were counterbalanced.

Five Consequence vignettes assessed children’s perceptions of the consequences of disclosing an adult’s wrongdoing after being warned not to tell. In these vignettes, children were told that the story child disclosed, and were then asked what the disclosure recipient would do as a result. The vignettes systematically varied the instigator (father, mother, or stranger) and disclosure recipient (mother or grandmother). Therefore, as in the Belief vignettes, the five vignettes asked about a) a father instigator/mother recipient; b) father instigator/grandmother recipient; c) mother instigator/grandmother recipient; d) stranger instigator/mother recipient, and e) stranger instigator/grandmother recipient. An example of a vignette is: “Here is a girl. Here is her dad. The dad makes the girl do something really bad. The dad doesn’t want anyone to know. He says to the girl, “Don’t tell.” Now this girl is with her mom. The girl tells her mom what her dad did. Now what will the mom do?”

In addition to being asked about how the disclosure recipient would behave following disclosure, children were asked how the recipient would react emotionally toward the story child (e.g., “How does the mom feel about the girl–happy or mad?”). However, because the question’s phrasing did not allow us to determine whether the disclosure recipient was upset with the child for disclosing the wrongdoing or for being involved in the wrongdoing, children’s responses to this question were not analyzed.

Vocabulary subsection of the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement (WJ-R; Woodcock & Johnson, 1989)

To determine if there was a need to control for differences in verbal skills, children completed the Woodcock Johnson vocabulary subtest, a widely used, standardized measure of verbal performance.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by relevant Institutional Review Boards. Interviews were videotaped and began with children providing assent. After a brief rapport building phase, the vignettes were presented, either via paper (33%) or computer (67%). The vignettes took approximately 15 minutes to administer. The order of the vignettes was standardized across children. Because the Belief vignettes were worded to make it unclear whether a transgression occurred, they were always presented first. The Recipient Preference vignettes were presented second because they specified that a transgression occurred, but the story child had not yet disclosed. The Consequences vignettes were always presented last, because a transgression had occurred and the story child had disclosed. Within each vignette type, the instigator-recipient combinations and the order of response options were counterbalanced, and the police officer alternated being presented as policeman versus policewoman. After the first vignette, the story child was introduced as “a different girl/boy.” After the vignettes were complete, the WJ-R was administered. Finally, children were thanked, debriefed, and given a prize.

Results

Preliminary Analyses and Analytic Approach

Preliminary analyses tested for response differences based on presentation type (paper or computer), child gender, ethnicity, and verbal skills. Then, differences between mother versus father instigators; male versus female police officer recipients; and mother versus grandmother recipients were tested.

There were no effects of presentation type on children’s responses, and no age X presentation type interaction. In the Recipient Preference vignettes, girls were more likely than boys to indicate that the story child would choose to disclose to a caregiver rather than a police officer [Ms = .47 and .39 (SDs = .36 and .39), respectively], with higher scores reflecting preference for a caregiver recipient), F (1, 232) = 4.13, p = .043, η2 = .02. In the Consequences vignettes, girls (M = .23, SD = .26) were also more likely than boys (M = .16, SD = .22) to predict that disclosure recipients would respond with formal intervention when the story child disclosed, F (1, 232) = 6.89, p = .009, η2 = .03. Including gender in the primary analyses did not affect the results, and gender is not further discussed.

One ethnicity effect emerged. In the Recipient Preference vignettes, with verbal performance controlled, there was a main effect of ethnicity, which was subsumed by an ethnicity X instigator interaction, F (2, 199) = 3.31, p = .038, η2 = .03. Latino children more often chose the caregiver disclosure recipient when a parent (M = .47, SD = .35) rather than a stranger (M = .31, SD = .36) was the instigator. Caucasian children exhibited the same pattern [Ms = .59 and .42 (SDs = .31 and .39) for parent and stranger, respectively], but their numbers were small (8% of the sample), and the difference was non-significant. African American children did not distinguish between parent and stranger instigators [Ms = .51 and .49 (SDs = .36 and .34) for parent and stranger, respectively]. Because this was the only ethnicity effect, and because a similar examination of recipient preferences found no ethnic differences (Lyon et al., 2010), ethnicity was not included in the primary analyses.

Verbal performance (raw scores on the WJ-R vocabulary subtest) was comparable between maltreated (M = 23.73, SD = 4.28) and non-maltreated (M = 24.28, SD = 5.18) children, including within each age [Ms = 20.53, 23.06, and 27.17 (SDs = 2.80, 3.00, and 4.02) for the maltreated 4-to 5, 6- to 7, and 8- to 9-year-olds respectively, and Ms = 20.37, 24.44, and 27.69 (SDs = 4.54, 4.21, and 3.99) for the non-maltreated 4- to 5, 6- to 7, and 8- to 9-year-olds respectively). Within each age group, verbal performance was unrelated to children’s responses.

Next, instigator and recipient characteristics were examined. No significant differences in responses emerged between mother and father instigators for any of the three vignette types. They were thus averaged into “parent” scores. Nor were there significant differences in children’s disclosure recipient responses between the male and female police officers for the Recipient Preference types, which were then collapsed into “police” scores. Finally, when caregiver disclosure recipients were compared, results revealed that children perceived the mother and grandmother recipients similarly when responding to the Recipient Preference vignettes and the Consequence vignettes. For the Belief vignettes, when discussing their own beliefs, children thought that a mother recipient would believe the story child as a truth teller (M = .70, SD = .34) more often than they thought a grandmother would (M = .59, SD = .34), with higher scores reflecting belief in the child. However, children’s predictions of recipient belief of the story child did not differ based on recipient identity (Ms = .65, SDs = .32, .33), F = (1, 228) = 7.88, p = .005, η2 = .03. That is, children were equally likely to expect the mother recipient and the grandmother recipient to believe the story child. Therefore, scores were collapsed across mother and grandmother recipients into “caregiver” scores. The outcome measures for each vignette set represented mean scores across several vignettes (3 vignettes involving a parent instigator, 2 vignettes involving a stranger instigator). Thus, mixed model ANOVAs were conducted.

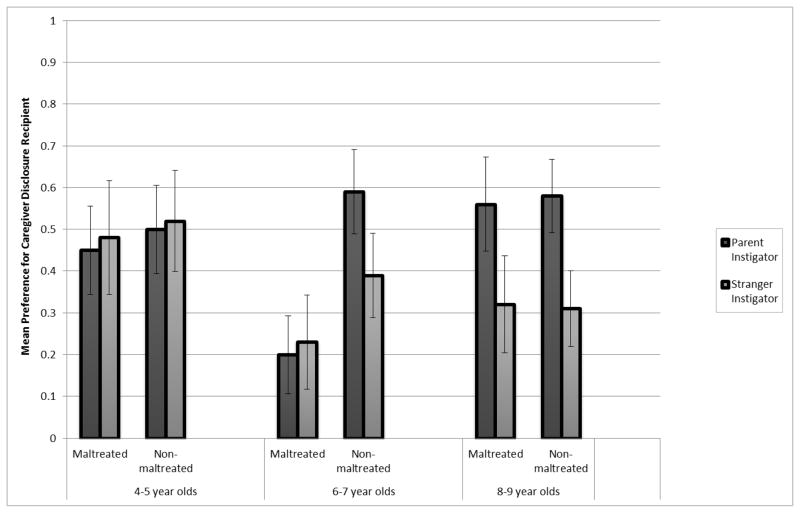

Recipient Preferences

In the Recipient Preference vignettes, children were asked to choose whether they would disclose a wrongdoing committed by a parent or a stranger to a caregiver (mother/grandmother) or a police officer. We expected children, especially those who were older, to prefer a caregiver over a police officer recipient when the instigator was a parent relative to a stranger, and that older non-maltreated children would be more likely than older maltreated children to exhibit this preference. Mean scores were calculated by averaging children’s responses across the vignettes concerning the parent instigator (mother and father, n = 3 vignettes) versus the stranger instigator (n = 2 vignettes), with higher scores reflecting choice of the caregiver recipient. Children’s mean responses are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Children’s preference for caregiver disclosure recipients by age, maltreatment status, and instigator identity. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval for the mean scores.

Children’s mean preference scores were entered into a 3 (age: 4–5 v. 6–7 v. 8–9) X 2 (maltreatment status: maltreated v. non-maltreated) X 2 (instigator: parent v. stranger) ANOVA, with the instigator factor varying within subjects. Significant main effects of age, maltreatment status, and instigator emerged, Fs (1 or 2, 228) 5.13, ps .007, η2 = .04 to .06, but were subsumed by two significant interactions. First, as expected, a significant age X instigator interaction, F (2, 228) = 9.11, p < .001, η2 = .07, emerged. The oldest age group was more likely to choose a caregiver disclosure recipient when disclosing wrongdoing committed by a parent than a stranger, F (1, 79) = 24.25, p < .001, η2 = .24. The 6- to 7-year-olds exhibited a similar trend in terms of selecting a caregiver disclosure recipient when the wrongdoing was committed by a parent as opposed to a stranger, F (1, 76) = 3.47, p = .067, η2 = .04, whereas the 4- to 5-year-olds did not differ in their preference for a caregiver based on who committed the wrongdoing. Second, an unexpected age X maltreatment status interaction, F (2, 228) = 6.08, p = .003, η2 = .05, revealed that, among the 6- to 7-year-olds, non-maltreated children were more likely to choose a caregiver disclosure recipient, while maltreated children were more likely to choose a police recipient, F (1, 76) = 23.8, p < .001, η2 = .24. In addition, as is suggested in Figure 1, the maltreated 6- to 7-year-olds failed to distinguish between parent and stranger instigators when choosing a recipient, while the 6- to 7-year-old non-maltreated children, as well as the older age group, appeared to make such a distinction.

Taken together, these findings suggest that, whereas both groups of 4- to 5-year-olds chose randomly between disclosing to a caregiver and disclosing to the police, the oldest age group clearly preferred disclosing caregivers’ transgressions to caregivers, and strangers’ transgressions to the police. However, the trend suggests that this pattern began to emerge among non-maltreated children at 6–7 years of age, whereas maltreated 6- to 7-year-olds exhibited a general preference to choose the police as the recipient.

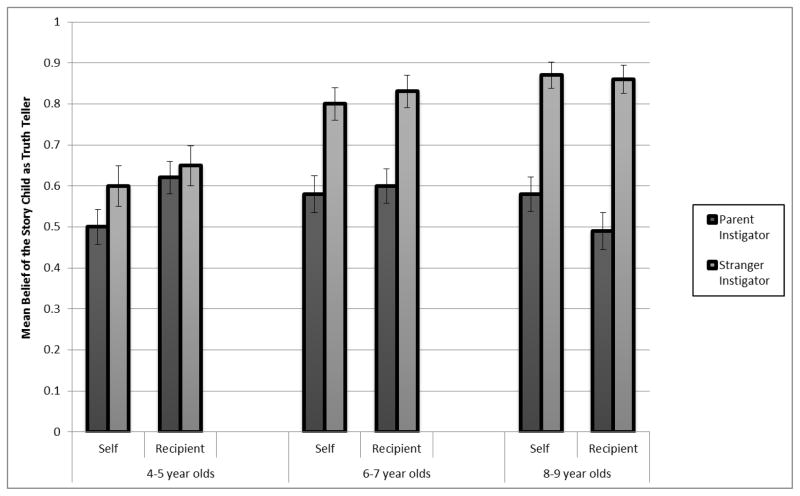

Belief

In the Belief vignettes, children were asked (1) who the disclosure recipient expected to tell the truth and (2) who they expected to tell the truth about a potential wrongdoing, the story child or the instigator. We hypothesized that children would be more likely to expect the disclosure recipient to believe the story child when a stranger rather than a parent was the instigator, and that this difference would increase with age and be larger among the maltreated children. Mean scores were calculated separately for children’s responses about the disclosure recipient’s beliefs and their own beliefs by first averaging responses for the parent instigator (father and mother), and second, collapsing across mother and grandmother disclosure recipients. This resulted in two mean scores for disclosure recipients’ beliefs (parent instigator and stranger instigator) and two mean scores for children’s own beliefs (parent instigator and stranger instigator), with higher scores reflecting belief of the story child as the truth-teller. Children’s responses are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Children’s own belief and predictions of recipients’ belief of the story child as truth-teller by age and instigator identity. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval for the mean scores.

Children’s mean scores were entered into a 3 (age) X 2 (maltreatment status) X 2 (instigator) X 2 (self/recipient belief: child participant v. disclosure recipient) mixed model ANOVA. Significant main effects of age, F (2, 228) = 7.28, p = .001, η2=.06, and instigator, F (1, 228) = 92.87, p < .001, η2=.29, emerged, but were subsumed by significant age X instigator, F (2, 228) = 13.11, p < .001, η2 = .10, and age X self/recipient belief interactions, F (2, 225) = 3.39, p = .036, η2=.03. Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no effects of maltreatment status. Follow-up analyses on the age X instigator interaction revealed that the two older age groups distinguished between the parent and stranger instigator when predicting who would tell the truth (both with regard to who they thought the recipient would believe and their own perceptions). Specifically, 6- to 7-year-olds and 8- to 9-year-olds expected recipients to believe the child more often when the instigator was a stranger rather than a parent, F (1, 76) = 30.04, p < .001, η2 = .28 and F (1, 79) = 84.48, p < .001, η2 = .52. The youngest children (4- to 5-year-olds), however, only exhibited a trend to distinguish between instigators, F (1, 73) = 3.71, p = .058, η2 = .05 (Figure 2).

Regarding the age X self/recipient belief interaction, follow-up analyses revealed that the 4- to 5-year-olds predicted disclosure recipients would more often believe the story child as the truth-teller (M = .64, SD = .34) than they would (M = .55, SD = .36), F (1, 73) = 4.25, p = .043, η2 = .06. The two older age groups did not differ in their ratings of disclosure recipients’ belief and their own belief, although the 8- to 9-year-olds exhibited a non-significant tendency to predict that disclosure recipients would less often believe the story child (M = .49, SD = .25) than they would when the instigator was a parent (M = .58, SD = .33).

In sum, the two older groups of children anticipated that disclosure recipients would be more likely to believe the child when accusing a stranger than when accusing a parent, and they were also more likely to believe that the child accusing a stranger would be telling the truth. The youngest children anticipated that recipients would believe children more than they should. Unexpectedly, maltreatment status did not influence children’s responses to the Belief vignettes.

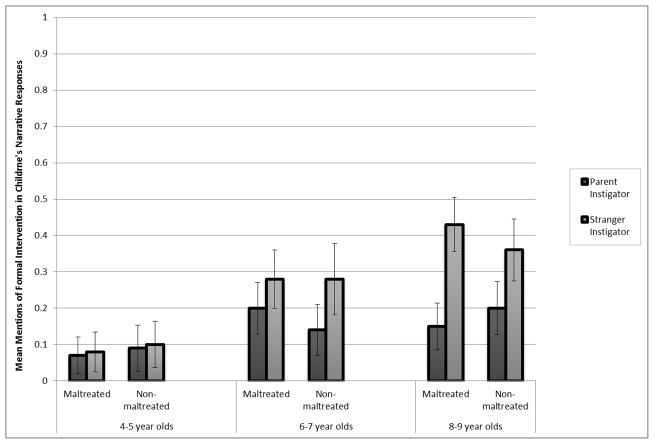

Consequences

In the Consequences vignettes, children were asked what the disclosure recipient would do after the story child disclosed. We expected children, especially older and maltreated children, to predict that disclosure recipients would react by initiating formal intervention (i.e., involving legal authorities) more often when the instigator was a stranger than a parent. Children’s narrative responses were coded for the mention of formal intervention, defined as reference to the police, jail, or other formal punishment. Three raters coded 20% of children’s responses, agreement Kappas .78. Children rarely said “I don’t know” [Ms = .05, .03, .01 (SDs = .16, .09, .05) for 4–5, 6–7, and 8–9 year olds, respectively] or failed to provide a response [Ms= .01, .002, .002 (SDs = .06, .02, .02) for 4–5, 6–7, and 8–9 year olds, respectively], and there were no differences in their tendency to do either based on age or maltreatment status. Mean responses were calculated by averaging across vignettes involving the parent instigator and stranger instigator. Children’s responses are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Children’s responses predicting formal intervention based on age, maltreatment status, and instigator identity. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval for the mean scores.

We entered children’s mean scores reflecting how often they mentioned formal intervention as a consequence of disclosure into a 3 (age) X 2 (maltreatment status) X 2 (instigator) mixed model ANOVA. Analyses revealed significant main effects of age, F (2, 228) = 19.55, p < .001, η2 = .15, and instigator, F (1, 228) = 58.89, p < .001, η2 = .21, as well as age X instigator, F (2, 228) = 16.95, p < .001, η2 = .13, and age X maltreatment status X instigator, F (2, 228) = 3.45, p = .033, η2 = .03, interactions. Follow-up analyses of the age X maltreatment status X instigator interaction revealed that the oldest children (8- to 9-year-olds) expected disclosure recipients to respond with formal intervention less often when a parent than a stranger was the instigator, and that this difference was most robust among the oldest maltreated children, Fs (1, 36 or 43) 14.16, ps .001, η2 = .25 to .57 (Figure 3).

Discussion

Naturalistic studies of child maltreatment allegations and experimental work have found that when a parent is implicated in wrongdoing, children are less forthcoming than when strangers are implicated (Hershkowitz, Horowitz, & Lamb, 2005; London et al., 2008; Tye et al., 1999). The overarching purpose of the present study was to advance understanding of the factors underlying children’s decisions to disclose adult wrongdoing. We were especially interested in children’s disclosure recipient preferences and expectations concerning the consequences of disclosing an adult’s wrongdoing, the effects of a child’s relationship to the person who committed the wrongdoing (i.e., the instigator) on children’s perceptions, and whether children’s perceptions vary depending on their age and history of substantiated maltreatment. This is the first experimental study to examine children’s expectations of recipient’s beliefs and recipient’s help-seeking following disclosure. The results complement non-vignette studies in which alleged victims describe their expectations concerning abuse disclosure (e.g. Hershkowitz et al., 2007) and, with respect to recipient preferences, are consistent with findings of a previous vignette study (Lyon et al., 2010).

Several key findings emerged, including those with important developmental and practical implications. First, in the Recipient Preference vignettes, with age, children increasingly preferred a caregiver over a police officer as a disclosure recipient when the instigator was a parent, with no similar age-related changes in preferences when the instigator was a stranger. This preference for a caregiver disclosure recipient, though, appeared to emerge more gradually in maltreated than non-maltreated children. Second, in the Belief vignettes, older children (6- to 9-year-olds) recognized that disclosure recipients would be more skeptical of the story child’s account when the child accused a parent rather than a stranger of wrongdoing. Third, in the Consequences vignettes, the oldest children expected the caregiver disclosure recipient to seek formal intervention less often when a parent than stranger was the instigator, and the oldest maltreated children were particularly attuned to this differential treatment of parent versus stranger instigators by caregiver recipients. Each of these findings is discussed in turn.

Recipient Preferences

The results support the proposition that as children mature, they understand the significance of the disclosure recipient when they decide whether to disclose wrongdoing, and that they prefer keeping information about wrongdoing within the family. When children disclose abuse, they most often disclose to mothers (Anderson et al., 1993; Fleming, 1997) and abuse by parents is less likely than abuse by strangers to be reported to the police (Hanson, Resnick, Saunders, Kilpatrick, & Best, 1999). As children mature, they better understand family loyalties and obligations (Leibig & Green, 1999), develop a faith in secret-keeping as an important aspect of friendship (Rotenberg, 1991), and become less likely to endorse disclosure of wrongdoing by peers (Piaget, 1932; Watson & Valtin, 1997). By 6 to 7 years of age, our non-maltreated children exhibited a trend for choosing caregivers over the police as preferred recipients for wrongdoing implicating the parent. The results for non-maltreated children are consistent with Lyon and colleagues (2010), who asked children whether a story child would or should disclose transgressions by parents or strangers to the police: By 6 to 7 years of age, non-maltreated children preferred parent recipients to police recipients when deciding whether to disclose parental wrongdoing.

With respect to maltreated children, we found similar attitudes emerging among the oldest children (8–9 years of age), whereas Lyon and colleagues (2010) found no preference. The studies used somewhat different approaches. In this study, the wrongdoing also implicated the story child, and the story child always disclosed; the question was to whom. In Lyon et al. (2010), the wrongdoing only involved the instigator, and the children were asked whether the story child would or should disclose. We suspect that the need to keep wrongdoing within the family was more salient in this study, because disclosing the wrongdoing would implicate both the story child and the instigator. Therefore, the oldest maltreated children in our study exhibited some awareness of this dynamic.

Nevertheless, there were still signs of distrust in caregivers among the maltreated children, a phenomenon found in prior research (Toth et al., 1997). The younger maltreated children showed an interesting pattern. Once they exhibited any kind of recipient preference, by 6–7 years of age, they showed a strong preference for police recipients regardless of the instigator’s identity. By 8 to 9-years of age, however, they resembled their non-maltreated counterparts, distinguishing between parent and stranger instigators when choosing disclosure recipients.

Belief

The results show that as children mature they also acquire the understanding that caregivers will be more skeptical of their disclosures if they accuse a parent. Among the children six and older, children assumed that a caregiver would believe the child over the stranger over 80% of the time, whereas they anticipated similar faith in the child’s report no more than 60% of the time. Former abuse victims often refer to the fear that they would not be believed as a deterrent to disclosure (e.g., Anderson et al., 1993), and children disclosing abuse anticipated less support from their parents if they were accusing someone known to the family (Hershkowitz et al., 2007; Malloy et al., 2011).

Surprisingly, no differences emerged between maltreated and non-maltreated children in terms of anticipated belief. We expected that maltreated children would assume greater skepticism by caretakers, given their expectations of adult unsupportiveness. Perhaps maltreated children do not doubt that caregivers will believe their disclosures but doubt that caregivers will respond in a protective manner, supporting Elliott and Carnes’ (2001) view that caregiver supportiveness in situations where child maltreatment is suspected should encompass more than a simple belief of the allegations.

Consequences

The oldest children recognized that caregiver recipients are less likely to notify the authorities when a child accuses a parent, and the oldest maltreated children were especially attuned to this difference. This complements both experimental and observational research showing how children exhibit greater understanding of the potential consequences of disclosure as they mature (Malloy et al., 2011; Wagland & Bussey, 2005). The maltreatment effect supports the proposition that what makes maltreated children different is not whether they expect to be believed, but what they expect to happen when they disclose to a caregiver.

An unanswered question is how expectations that authorities will be contacted affects children’s attitudes about disclosure. Formal intervention can be either a deterrent to or an incentive for disclosure. Therefore, when children choose a parent recipient over a police recipient, they may do so precisely because they anticipate that the parent will never contact the police. Future research can explore how different attitudes and expectations work together in influencing children’s ultimate decisions regarding whether and to whom to disclose.

A few tentative findings are promising avenues for future work. We found that Latino children uniquely exhibited a preference for caregiver recipients when the instigator was a parent compared to Caucasian and African-American children. In contrast, Lyon et al. (2010) did not find any ethnic differences in children’s willingness to endorse disclosure parental wrongdoing in a vignette-based study that included maltreated and non-maltreated children, with similar proportions of Latino children. Similarly, observational research has not consistently found ethnic differences in abuse disclosure patterns (London et al, 2008; Malloy et al., 2007). Nevertheless, some commentators have noted that strong familial ties may deter disclosure of abuse among Latinos (e.g., Fontes, 1993; Shaw et al., 2001), and this is worthy of future work.

Two issues are important to consider regarding our investigation. One is whether differences between maltreated and non-maltreated children could be attributable to different assumptions between the groups in what the “really bad” transgressions committed by the adults could have been. At the end of the testing session, we asked children what each adult instigator did that was “really bad.” Responses were reliably coded for transgression type, (Kappas ≥ .78). No differences emerged in the types of transgressions children mentioned based on maltreatment status or instigator identity. Children most often mentioned theft (Ms = .14 and .12 for maltreated and non-maltreated children, respectively), minor infractions or rule breaking (Ms = .16 and .19 for maltreated and non-maltreated children, respectively), property damage (Ms = .07 and .09 for maltreated and non-maltreated children, respectively), or physical harm (Ms = .21 and .13 for maltreated and non-maltreated children, respectively). Children said “I don’t know” (Ms = .12 and .08 for maltreated and non-maltreated children, respectively) or failed to provide a response (Ms = .03 and .02 for maltreated and non-maltreated children, respectively) relatively infrequently. Although “other” responses (i.e., responses which did not fit our coding categories) were relatively common, maltreated and non-maltreated children did not differ in their tendency to respond in this manner (Ms = .24 and .26, respectively).

Despite the novel findings that emerged in our study, limitations also need to be mentioned. One is that we relied on hypothetical vignettes, which were highly useful in allowing us to ask children directly about their perceptions and identify the factors that influence their judgments (Lagattuta, Wellman, & Flavell, 1997; Wagland & Bussey, 2005). Vignettes, however, are imperfect guides to actual behavior. It will be important to assess the relation of children’s perceptions of disclosure to their disclosure behaviors, both in the field and in the laboratory. Also, the vignettes primarily required forced choice responses which limited potential responses (e.g., there was no “nondisclosure” option): The elicitation of narrative responses may reveal subtle differences in children’s perceptions. Furthermore, because the nature of the vignettes required that children receive the sets in the same order, we were unable to test for fatigue effects. However, children’s productive narrative responses to the open-ended questions in the Consequences vignettes and final questions asking what the instigators did wrong suggests that fatigue was not a major issue.

Second, caution is warranted with respect to interpreting differences (or the lack of differences) between maltreated and non-maltreated children. We did not formally screen for maltreatment in our non-maltreated sample, and therefore some of the children may have been misclassified. However, by excluding children from the non-maltreated sample whose consent forms were signed by non-parents, we excluded children who had been recognized as maltreated by the state and who had been removed from their parents’ custody (Carrick et al., 2010; Lyon et al., 2010). If maltreated children were among the children classified as non-maltreated, this would mask differences between maltreated and non-maltreated children, making our study a more conservative test of our hypotheses. Related, maltreatment experiences vary considerably (Cicchetti, 2004; Cicchetti & Toth, 1995), and the different forms of maltreatment may differentially affect children’s evaluations of disclosure. Although researchers have long noted the difficulties associated with making meaningful comparisons based on maltreatment subtype and the accuracy of agency records on specific subtypes (e.g., McGee, Wolfe, Yuen, Wilson, & Carnochan, 1995), such will be important to consider in future research.

To the extent that we found maltreatment effects, we are unable to determine whether they were due to maltreatment per se or to some related variable (e.g., state intervention). For example, violation of parental trust or disruption of the attachment relationship may be the mechanisms underlying observed differences. The present study involved children who were involved in dependency proceedings and removed from parental care due to substantiated maltreatment (i.e., the perpetrator had a custodial interest in the child and/or the non-offending caregiver was unable or unwilling to protect the child). Most cases thus involved allegations of intra-familial abuse or neglect, and therefore victims who raise the most concern due to their greater reluctance to disclose and risk of recantation (Hershkowitz et al., 2005, 2007; Malloy et al., 2007; see Pipe et al., 2007, for a review). Also, for ethical reasons, we did not ask children about disclosing acts of child maltreatment specifically. Thus, caution should be exercised in applying the findings directly to maltreatment disclosure. Future research should ask victims of child maltreatment prospectively about their own disclosures. That is, longitudinal studies could examine children’s fears and expectations about maltreatment disclosure at the start of an investigation (e.g., Goodman-Brown et al., 2003; Malloy et al., 2011), which would help to tease apart the sources of their attitudes and understand how children’s perceptions affect their disclosures over time. Third, because children most often disclose first to caregivers, we were interested in children’s perceptions of disclosing adult transgressions to adult caregivers in particular. It will be important in the future to investigate children’s attitudes about peers, both as instigators and as disclosure recipients, given the increasing significance of peer relationships as children approach adolescence (Buhrmester & Prager, 1995; Hunter & Youniss, 1982), and the likelihood that older children disclose abuse to peers rather than parents (Fleming, 1997; Malloy, Brubacher, & Lamb, 2013). It will also be important to evaluate, in a more systematic manner, the conditions under which children meaningfully distinguish between a parent recipient and another trusted adult recipient, such as a grandmother, in terms of the consequences expected for disclosing.

In closing, the current study sheds light on children’s expectations and preferences concerning disclosure, and the potential impediments to disclosing adult wrongdoing. The results have practical implications for those who investigate child maltreatment allegations. In current practice, investigative interviewers fail to systematically ask children about their fears, expected responses, or pressures to remain silent or recant, even though children are particularly vulnerable to such pressures (e.g., Goodman-Brown et al., 2003; Malloy et al., 2007). Although further research is certainly needed before specific recommendations can be made to legal and social service professionals, it may be useful for interviewers to address children’s fear of disbelief and the appropriateness of talking to formal authorities about an adult’s, even a parent’s, act of wrongdoing. The results also have implications for intervention programs for maltreated children and their caregivers. Information concerning children’s expectations and preferences about disclosure highlight the conditions under which children expect unsupportive reactions from caregivers. Interventions aimed at enhancing caregiver supportiveness and maintaining children’s allegations may be targeted more appropriately toward children who are at greatest risk for failing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were presented at the American Psychology-Law Society annual meeting, Jacksonville, FL, 2008. Preparation of this article was supported in part by National Institute of Child and Human Development Grant HD047290 and a Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant from the National Science Foundation (SES-0720421). Vera Chelyapov, Megan Donahue, Hilary Feybush, Laura Hinojosa, Ektha Aggarwal, Deanna Cano, Yesenia Flores, Robyn Fredericksen, Jennie King, Kathryne Krueger, Irma Escobar, Bruce John, Emily Kerr, Crystal Lara, Leah Manchester, Sandra Marquez, Cindy Mekari, Deborah Ogbonna, Shadie Parivar, Megan Sim, LeighAnn Smith, and Aditi Wahi assisted in data collection and coding. We are grateful for the support of the Presiding Judge of the Los Angeles County Juvenile Court, the Los Angeles County Department of Children’s and Family Services, Los Angeles County Children’s Law Center, the Children’s Services Division of Los Angeles County Counsel, and the Los Angeles County Child Advocate’s Office.

Appendix A

Example of Recipient Preference vignette (Father instigator–Mother vs. Police Officer disclosure recipient)

Example of Belief vignette (Stranger instigator–Mother disclosure recipient)

Example of Consequence vignette (Mother instigator–Grandmother disclosure recipient)

Contributor Information

Lindsay C. Malloy, Florida International University

Jodi A. Quas, University of California, Irvine

Thomas D. Lyon, University of Southern California, Gould School of Law

Elizabeth C. Ahern, University of Southern California, Gould School of Law

References

- Anderson J, Martin J, Mullen P, Romans S, Herbison P. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse experiences in a community sample of women. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:911–919. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM. To tell or not to tell: Current functioning of child sexual abuse survivors who disclosed their victimization. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3:63–71. doi: 10.1177/1077559598003001006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms BL, Goodman GS, Schwartz-Kenney BM, Thomas SN. Understanding children’s use of secrecy in the context of eyewitness reports. Law and Human Behavior. 2002;26:285–314. doi: 10.1023/A:1015324304975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Prager K. Patterns and functions of self-disclosure during childhood and adolescence. In: Rotenberg KJ, editor. Disclosure processes in children and adolescents. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 10–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey K, Grimbeek EJ. Disclosure processes: Issues for child sexual abuse victims. In: Rotenberg KJ, editor. Disclosure processes in children and adolescents. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 166–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey K, Lee K, Grimbeek EJ. Lies and secrets: Implications for children’s reporting of sexual abuse. In: Goodman GS, Bottoms BL, editors. Child victims, child witnesses: Understanding and improving testimony. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Carrick N, Quas JA, Lyon TD. Maltreated and nonmaltreated children’s evaluations of emotional fantasy. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceci SJ, Leichtman M. “I know that you know that I know that you broke the toy”: A brief report of recursive awareness among 3-year-olds. In: Ceci SJ, Leichtman M, Putnick M, editors. Cognitive and social factors in early deception. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. An odyssey of discovery: Lessons learned through three decades of research on child maltreatment. American Psychologist. 2004;59:731–741. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:541–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Valente E. Social information-processing patterns partially mediate the effect of early physical abuse on later conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:632–643. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.104.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DM, Briere J. Forensic sexual abuse evaluations of older children disclosures and symptomatology. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 1994;12:261–277. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2370120306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott AN, Carnes CN. Reactions of nonoffending parents to the sexual abuse of their child: A review of the literature. Child Maltreatment. 2001;6:314–331. doi: 10.1177/1077559501006004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Taska L, Lewis M. The role of shame and attributional style in children’s and adolescents’ adaptation to sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3:129–142. doi: 10.1177/1077559598003002007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JM. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse in a community sample of Australian women. Medical Journal of Australia. 1997;166:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes LA. Disclosures of sexual abuse by Puerto Rican children: Oppression and cultural barriers. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 1993;2:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Brown TB, Edelstein RS, Goodman GS, Jones DPH, Gordon DS. Why children tell: A model of children’s disclosure of sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:525–540. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Best C. Factors related to the reporting of childhood rape. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:559–569. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkowitz I, Horowitz D, Lamb ME. Trends in children’s disclosure of abuse in Israel: A national study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:1203–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkowitz I, Lanes O, Lamb ME. Exploring the disclosure of child sexual abuse with alleged victims and their parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter FT, Youniss J. Changes in functions of three relations during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:306–311. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.18.6.806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM. Disclosing unwanted sexual experiences: Results from a national sample of adolescent women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:147–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagattuta KH, Wellman HM, Flavell JH. Preschoolers’ understanding of the link between thinking and feeling: Cognitive cuing and emotional change. Child Development. 1997;68:1081–1104. doi: 10.2307/1132293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last U, Aharoni-Etzioni A. Secrets and reasons for secrecy among school-aged children: Developmental trends and gender differences. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1995;156:191–203. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1995.9914816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson L, Chaffin M. False negatives in sexual abuse disclosure interviews: Incidence and influence of caretaker’s belief in abuse in cases of accidental abuse discovery by diagnosis of STD. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1992;7:532–542. doi: 10.1177/088626092007004008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leibig AL, Green K. The development of family loyalty and relational ethics in children. Contemporary Family Therapy. 1999;21:89–112. doi: 10.1023/A:1021966705566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Stanger C, Sullivan MW. Deception in 3-year-olds. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:439–443. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.3.439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- London KL, Bruck M, Wright DB, Ceci SJ. Review of the contemporary literature on how children report sexual abuse to others: Findings, methodological issues, and implications for forensic interviewers. Memory. 2008;16:29–47. doi: 10.1080/09658210701725732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD. Expert testimony on the suggestibility of children: Does it fit? In: Bottoms BL, Bull Kovera M, editors. Children, social science, and the law. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 378–411. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD. False denials: Overcoming methodological biases in abuse disclosure research. In: Pipe ME, Lamb ME, Orbach Y, Cederborg AC, editors. Disclosing abuse: Delays, denials, retractions and incomplete accounts. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD. Abuse disclosure: What adults can tell. In: Bottoms BL, Najdowski CJ, Goodman GS, editors. Children as victims, witnesses, and offenders: Psychological science and the law. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD, Ahern EA, Malloy LA, Quas JA. Children’s reasoning about disclosing adult transgressions: Effects of maltreatment, child age, and adult identity. Child Development. 2010;81:1714–1728. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD, Dorado JS. Truth induction in young maltreated children: The effects of oath-taking and reassurance on true and false disclosures. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:738–748. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD, Malloy LC, Quas JA, Talwar V. Coaching, truth induction, and young maltreated children’s false allegations and false denials. Child Development. 2008;79:914–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD, Saywitz KJ. Young maltreated children’s competence to take the oath. Applied Developmental Science. 1999;3:16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Malloy LC, Brubacher SP, Lamb ME. Expected consequences of disclosure revealed in investigative interviews with suspected victims of child sexual abuse. Applied Developmental Science. 2011;15:8–19. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.538616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy LC, Brubacher SP, Lamb ME. “Because she’s one who listens”: Children discuss disclosure recipients in forensic interviews. Child Maltreatment. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1077559513497250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy LC, Lyon TD, Quas JA. Filial dependency and recantation of child sexual abuse allegations. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:162–170. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246067.77953.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee RA, Wolfe DA, Yuen SA, Wilson SK. The measurement of maltreatment: A comparison of approaches. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19:233–249. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)00119-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine ML, Hansen DJ. Factors influencing children to self disclose sexual abuse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:271–295. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. The moral judgment of the child. Oxford, England: Harcourt, Brace; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Pipe ME, Lamb ME, Orbach Y, Cederborg A-C. Child sexual abuse: Disclosure, delay and denial. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pipe M, Wilson JC. Cues and secrets: Influences on children’s event reports. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:515–525. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.30.4.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polak A, Harris PL. Deception by young children following noncompliance. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:561–568. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.2.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Cicchetti D, Hornung K, Reed A. Recognizing emotion in faces: Developmental effects of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:679–688. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Vardi S, Putzer-Bechner AM, Curtin JJ. Physically abused children’s regulation of attention in response to hostility. Child Development. 2005;76:968–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quas JA, Goodman GS, Jones DPH. Predictors of attributions of self-blame and internalizing behavior problems in sexually abused children. Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:723–736. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg KJ. The trust-value basis of children’s friendship. In: Rotenberg KJ, editor. Children’s interpersonal trust: Sensitivity, lying, deception, and promise violations. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg KJ, McDougall P, Boulton MJ, Vaillancourt T, Fox C, Hymel S. Cross-sectional and longitudinal relations among peer-reported trustworthiness, social relationships, and psychological adjustment in children and early adolescents from the United Kingdom and Canada. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2004;88:46–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sas LD, Cunningham AH. Tipping the balance to tell the secret: The public discovery of child sexual abuse. London, Ontario: London Family Court Clinic; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sauzier M. Disclosure of child sexual abuse: For better or for worse. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1989;12:455–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JA, Lewis JE, Loeb A, Rosado J, Rodriguez RA. A comparison of Hispanic and African-American sexually abused girls and their families. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1363–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Ryan RM, Cicchetti D. Narrative representations of caregivers and emotion dysregulation as predictors of maltreated children’s rejection by peers. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:321–337. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar V, Gordon HM, Lee K. Lying in the elementary school years: Verbal deception and its relation to second-order belief understanding. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:804–810. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar V, Lee K. Development of lying to conceal a transgression: Children’s control of expressive behaviour during verbal deception. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26:436–444. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar V, Lee K, Bala N, Lindsay RCL. Children’s conceptual knowledge of lying and its relation to their actual behaviors: Implications for court competence examinations. Law & Human Behavior. 2002;26:395–415. doi: 10.1023/A:1016379104959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar V, Lee K, Bala N, Lindsay RCL. Children’s lie-telling to conceal a parent’s transgression: Legal implications. Law and Human Behavior. 2004;28:411–435. doi: 10.1023/B:LAHU.0000039333.51399.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Macfie J, Emde RN. Representations of self and other in the narratives of neglected, physically abused, and sexually abused preschoolers. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:781–796. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Macfie J, Rogosch FA, Maughan A. Narrative representations of moral-affiliative and conflictual themes and behavioral problems in maltreated preschoolers. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:307–318. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye MC, Amato SL, Honts CR, Devitt MK, Peters D. The willingness of children to lie and the assessment of credibility in an ecologically relevant laboratory setting. Applied Developmental Science. 1999;3:92–109. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads0302_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagland P, Bussey K. Factors that facilitate and undermine children’s beliefs about truth telling. Law & Human Behavior. 2005;29:639–655. doi: 10.1007/s10979-005-7371-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AJ, Valtin R. Secrecy in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;21:431–452. doi: 10.1080/016502597384730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, Johnson MB. Woodcock–Johnson Tests of Achievement (WJ-R) Allen, TX: DLM Teaching Resources; 1989. [Google Scholar]