Abstract

Extracellular matrix fibronectin fibrils serve as passive structural supports for the organization of cells into tissues, yet can also actively stimulate a variety of cell and tissue functions, including cell proliferation. Factors that control and coordinate the functional activities of fibronectin fibrils are not known. Here, we compared effects of cell adhesion to vitronectin versus type I collagen on the assembly of and response to, extracellular matrix fibronectin fibrils. The amount of insoluble fibronectin matrix fibrils assembled by fibronectin-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts adherent to collagen- or vitronectin-coated substrates was not significantly different 20 h after fibronectin addition. However, the fibronectin matrix produced by vitronectin-adherent cells was ~10-fold less effective at enhancing cell proliferation than that of collagen-adherent cells. Increasing insoluble fibronectin levels with the fibronectin fragment, anastellin did not increase cell proliferation. Rather, native fibronectin fibrils polymerized by collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells exhibited conformational differences in the growth-promoting, III-1 region of fibronectin, with collagen-adherent cells producing fibronectin fibrils in a more extended conformation. Fibronectin matrix assembly on either substrate was mediated by α5β1 integrins. However, on vitronectin-adherent cells, α5β1 integrins functioned in a lower activation state, characterized by reduced 9EG7 binding and decreased talin association. The inhibitory effect of vitronectin on fibronectin-mediated cell proliferation was localized to the cell-binding domain, but was not a general property of αvβ3 integrin-binding substrates. These data suggest that adhesion to vitronectin allows for the uncoupling of fibronectin fibril formation from downstream signaling events by reducing α5β1 integrin activation and fibronectin fibril extension.

Keywords: Extracellular matrix, fibronectin, collagen, vitronectin, cell proliferation, integrin

1. Introduction

Extracellular matrices (ECM) are intricate networks of collagens, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans that maintain tissue cohesion, provide physical support to tissues and organs, and determine the mechanical properties of tissues (Hynes, 2009). In addition to these structural functions, ligation of ECM proteins by various cell surface receptors can initiate biochemical signaling pathways that control cell behaviors important for tissue formation and function (Kleinman et al., 2003). In order to maintain tissue homeostasis, yet allow for changes in tissue function, ECM proteins must shift between these two functional states. Mechanisms that permit ECMs to locally transition from ‘inert’ structural elements to ‘active’ signaling complexes are largely unknown but may include changes in protein composition, organization, degradation, turnover, and/or conformation (Beacham and Cukierman, 2005; Clause and Barker, 2013; Nelson and Bissell, 2006; Sottile et al., 2007). Imbalances in the relative expression of the passive structural and active signaling states of ECM proteins within the tissue microenvironment may underlie a variety of pathological conditions, including atherosclerosis, tumor progression, chronic wounds, and fibrosis.

The glycoprotein fibronectin is a principal component of interstitial ECMs. Fibronectin is ubiquitously expressed in a variety of tissues in the body, and is abundant in regions surrounding blood vessels, in lymphatic tissue stroma, and in loose connective tissue (Stenman and Vaheri, 1978). Fibronectin circulates in the plasma and other body fluids in a soluble form, and is continually assembled into insoluble ECM fibrils by a cell-dependent process (Singh et al., 2010). During the matrix assembly process, soluble cell-bound fibronectin molecules undergo a series of conformational changes that result in exposure of self-interactive sites and the subsequent formation of fibronectin fibrils (Singh et al., 2010). Tractional forces produced by cell or tissue movement can induce further conformational changes to expose neoepitopes, or “matricryptic sites” (Baneyx et al., 2001; Hocking et al., 2008; Ohashi et al., 1999) that mediate effects of ECM fibronectin on cell and tissue function (Davis et al., 2000; Gui et al., 2006; Hocking et al., 2008). ECM fibronectin fibrils have the capacity to stimulate a variety of cellular activities, including cell spreading, growth, migration, and contractility (Hocking and Chang, 2003; Hocking et al., 2000; Mercurius and Morla, 1998; Morla et al., 1994; Sottile et al., 2000; Sottile et al., 1998). In vivo, matricryptic sites in interstitial fibronectin fibrils contribute to resting vascular tone, and mediate transient, local vascular responses to skeletal muscle contraction via a nitric oxide-dependent pathway (Hocking et al., 2008). The formation of fibronectin fibrils in the body is a continuous process, with as much as 50% of ECM fibronectin turnover occurring every 24 h (Rebres et al., 1995). Thus, fibronectin fibril structure must be tightly regulated in order to prevent inappropriate or unregulated expression of the signaling activity of ECM fibronectin fibrils.

Vitronectin is another multifunctional glycoprotein that is present in various body fluids, including plasma and amniotic fluid, and is also found in limited quantities in the ECM (Dahlback et al., 1986; Hayman et al., 1983). In normal tissue, vitronectin is predominately associated with loose connective tissue (Reilly and Nash, 1988). Similar to fibronectin, increased tissue deposition of vitronectin has been observed in a number of disease states, including tissue fibrosis (Reilly and Nash, 1988), atherosclerosis (Dufourcq et al., 1998; Stenman et al., 1980), tumor progression (Kaplan et al., 2005; Loridon-Rosa et al., 1988) and sepsis (Brien et al., 1998; Singh et al., 2005). Similar tissue distribution patterns of vitronectin and fibronectin have been observed in fibrotic tissues, within the reactive stroma of tumors, and in the provisional matrix during wound repair (Reilly and Nash, 1988; Singer and Clark, 1999). In vitro, vitronectin can inhibit the deposition of fibronectin into the ECM (Bae et al., 2004; Hocking et al., 1999; Vial and McKeown-Longo, 2008; Vial et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 1999b), suggesting that vitronectin can regulate ECM fibronectin function by reducing the extent of fibronectin matrix deposition. Other studies indicate that vitronectin can enhance fibronectin fibrillogenesis, as ligation of the vitronectin integrin receptor plays a key role in mediating the centripetal movement of fibronectin into fibrillar adhesions (Pankov et al., 2000).

In the present study, we examined how adhesion of cells to either vitronectin or collagen I affects fibronectin fibril assembly, structure, and function. Fibronectin-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (FN-null MEFs), cultured in defined serum- and fibronectin-free growth media, were used to directly compare the mechanisms and cellular effects of vitronectin-mediated fibronectin matrix assembly with that of collagen-mediated assembly. FN-null MEFs polymerize exogenously-added fibronectin into ECM fibrils via a process indistinguishable from that of fibronectin-expressing cells (Sottile et al., 1998), and do not express detectable levels of vitronectin (Wojciechowski et al., 2004). Thus, this model permits tight control over the composition of the adhesive substrate, the amount of fibronectin to which the cells are exposed, and the initiation and timing of the matrix assembly process. We identify similarities and differences in the assembly process utilized to produce these two fibronectin matrices and show that fibronectin fibrils produced by vitronectin-adherent cells are significantly less effective at supporting integrin activation and stimulating cell proliferation than those produced by collagen-adherent cells. These studies suggest opposing roles for vitronectin and collagen in regulating the structural and functional properties of ECM fibronectin.

2. Results

2.1. Effects of vitronectin and collagen on fibronectin-induced cell proliferation

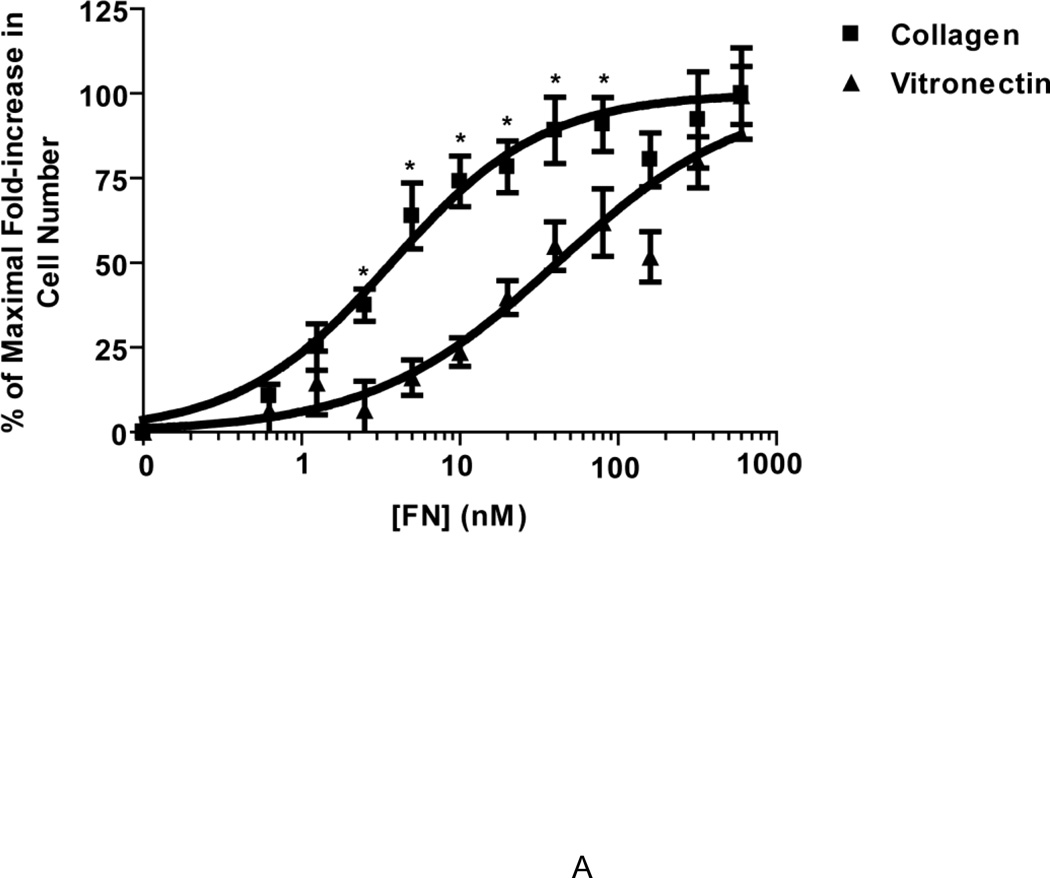

Several previous studies have established that the active assembly of a fibronectin matrix can enhance cell proliferation (Mercurius and Morla, 1998; Sechler and Schwarzbauer, 1998; Sottile et al., 1998). Thus, cell proliferation assays were used in the present study to assess the functional state of fibronectin fibrils. To examine the effect of substrate adhesion on the proliferative response to ECM fibronectin, FN-null MEFs were seeded onto wells pre-coated with saturating concentrations of either collagen or vitronectin (Sottile et al., 1998; Wojciechowski et al., 2004), in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of fibronectin. Cell number was determined after 4 days (Sottile et al., 1998). Addition of high concentrations of fibronectin (600 nM; ~ plasma concentration (Mosher, 1984)) to either collagen- or vitronectin-adherent cells resulted in a similar 2-fold increase in cell number on day 4, compared to cells cultured in the absence of fibronectin (not shown). The growth response of collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells to various fibronectin concentrations was then calculated as a percentage of the growth response to 600 nM fibronectin and sigmoidal curves were generated for both substrates (Fig. 1A). Adhesion of cells to vitronectin resulted in a rightward shift of the fibronectin dose response curve compared to that of collagen-adherent cells (Fig. 1A), indicating that vitronectin-adherent cells required more fibronectin to achieve a similar increase in cell number as collagen-adherent cells. The concentration of fibronectin required to produce 50% of the maximal fibronectin-induced growth was 41.1 ± 1.17 nM for vitronectin-adherent cells and 3.7 ± 1.2 nM for collagen-adherent cells. In parallel studies, the amount of fibronectin bound to collagen- or vitronectin-adherent cells was quantified 20 h after fibronectin addition, prior to changes in cell number (Sottile et al., 1998). At this time point, the amount of fibronectin bound by vitronectin-adherent cells was not significantly different from that of collagen-adherent cells for all fibronectin concentrations tested (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Cell adhesion to vitronectin reduces the proliferative response to fibronectin.

FN-null MEFs were seeded (A, 2.6 × 103 cells/cm2; B, 3 × 104 cells/cm2) onto collagen- or vitronectin-coated wells and allowed to adhere for 4 h. (A) Fibronectin (0.625 – 600 nM) or an equal volume of the vehicle control, PBS (‘0’ FN), was added to wells. Cell number was determined 4 days after seeding. Data are presented as a percentage of the maximal-fold increase in cell number relative to PBS-treated controls. Graph Pad Prism was used to fit a sigmoidal curve to the data. *Significantly different from vitronectin-adherent cells at the given fibronectin concentration by Student’s t-test, n > 3 for all time points. The average absorbance values for control (PBS)-treated groups were 0.28 ± 0.02 (collagen) and 0.34 ± 0.02 (vitronectin). (B) Alexa488-labeled fibronectin (FN488, 2.50 – 600 nM) was added to wells and cells were incubated for an additional 20 h. FN488 accumulation was determined as described in “Experimental Methods”. Data are presented as mean fluorescence ± SEM and are compiled from 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate.

2.2. Kinetics of fibronectin matrix deposition by collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells

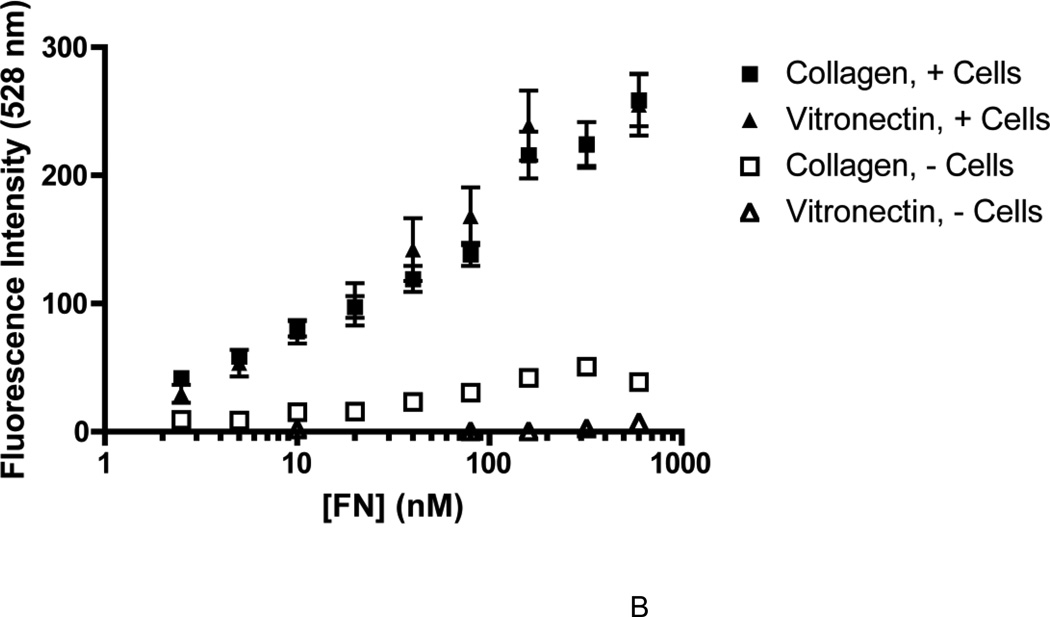

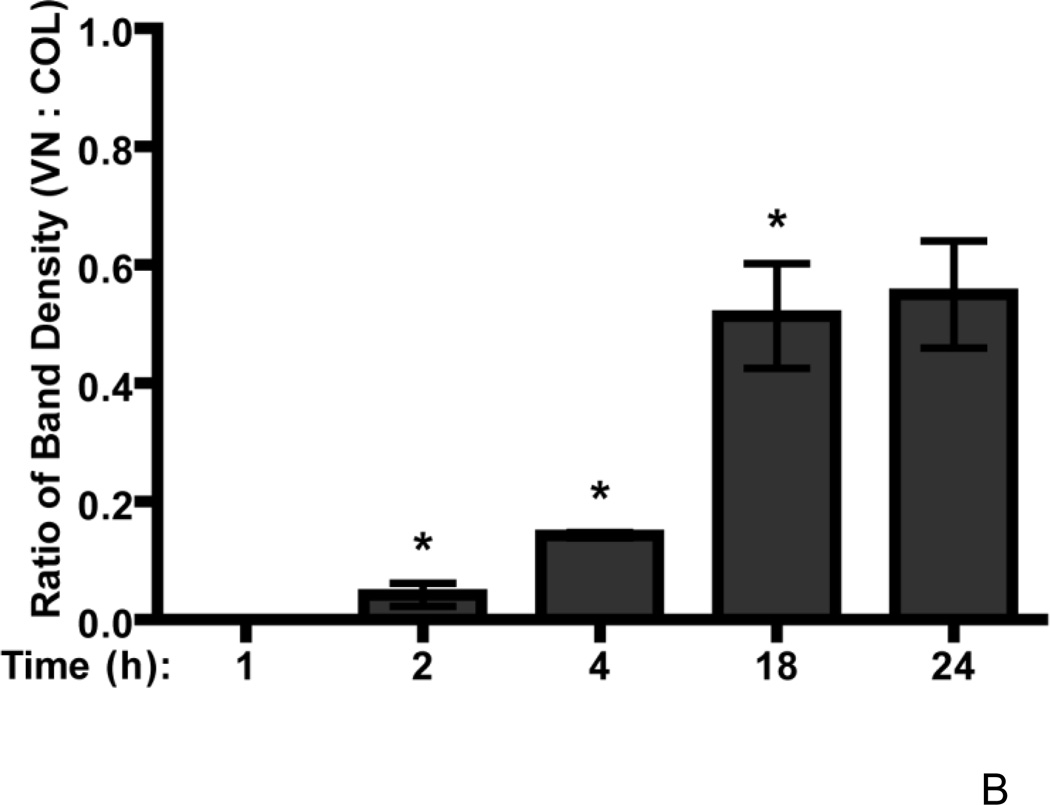

The effect of substrate adhesion on fibronectin matrix assembly was next assessed at several other time points after fibronectin addition. FN-null MEFs were seeded onto collagen- or vitronectin-coated substrates and incubated with 20 nM fibronectin. The dose of fibronectin chosen for these and subsequent studies corresponds to the mid-point of the fibronectin dose response curves where significant differences in the growth response of vitronectin- and collagen-adherent cells were observed (Fig. 1A). Time course immunofluorescence microscopy studies showed that fibrillar fibronectin matrices were present on both collagen- and vitronectin-adherent FN-null MEFs at 1, 4, and 24 h after fibronectin addition (Fig. 2A). To quantify ECM fibronectin levels, soluble, cell-bound fibronectin was separated from ECM fibronectin by DOC extraction, and the relative amount of fibronectin associated with each fraction was determined. The amount of ECM fibronectin increased during the first 18 h of incubation for both substrates, although the kinetics of fibronectin deposition differed (Fig. 2B). Four h after fibronectin addition, the net amount of ECM fibronectin deposited by collagen-adherent cells was 86 ± 5% more than that of vitronectin-adherent cells (Fig. 2B). After 18 h of fibronectin treatment, collagen-adherent cells had deposited 45 ± 9% more fibronectin than vitronectin-adherent cells (Fig. 2B). By 24 h, the amount of DOC-insoluble fibronectin deposited by collagen-adherent cells was not significantly different from that of vitronectin-adherent cells (Fig. 2B), in agreement with the data derived using Alexa488-labeled fibronectin (Fig. 1B). Fibronectin fibril staining was also similar for vitronectin- and collagen-adherent cells on day 4 (Fig. 2C; 96 h). Thus, collagen-adherent cells deposited more ECM fibronectin at earlier time points than vitronectin-adherent cells. By 24 h, the amount of ECM fibronectin deposited by vitronectin- and collagen-adherent cells was similar.

Figure 2. Time course of fibronectin matrix assembly.

FN-null MEFs (3 × 103 cells/cm2) were seeded onto substrates precoated with either collagen or vitronectin, allowed to adhere for 4 h, and then treated with fibronectin (20 nM). (A) At 1, 4, 24, and (C) 96 h after fibronectin addition, cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy. Fibronectin was detected using a polyclonal anti-fibronectin antibody. Bar = 10 µm. Image shown represents of 1 of 3 independent experiments performed. (B) At indicated times, DOC-extractions were performed. Aliquots of the DOC-insoluble fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting and quantified by densitometry. The ratio of the average net intensity of fibronectin bands for vitronectin-adherent cells to the average net intensity of fibronectin bands for collagen-adherent cells was determined for each time point. Data are presented as the average ratio of 3 experiments performed in duplicate. *Significantly different from collagen-adherent cells at given time point by paired Student’s t-test.

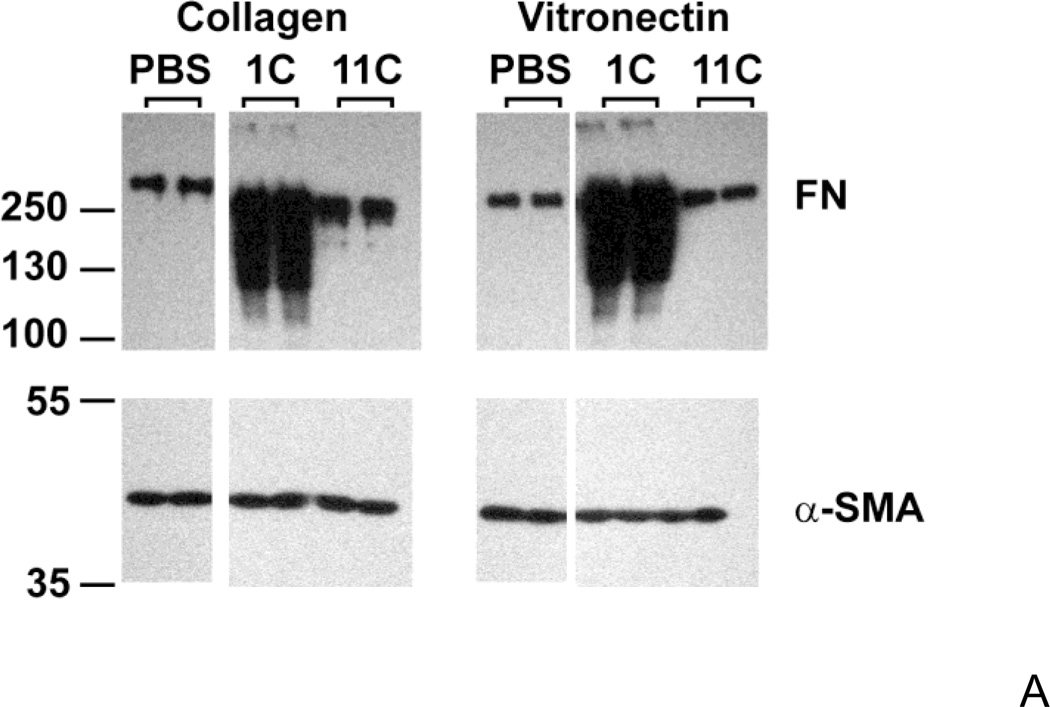

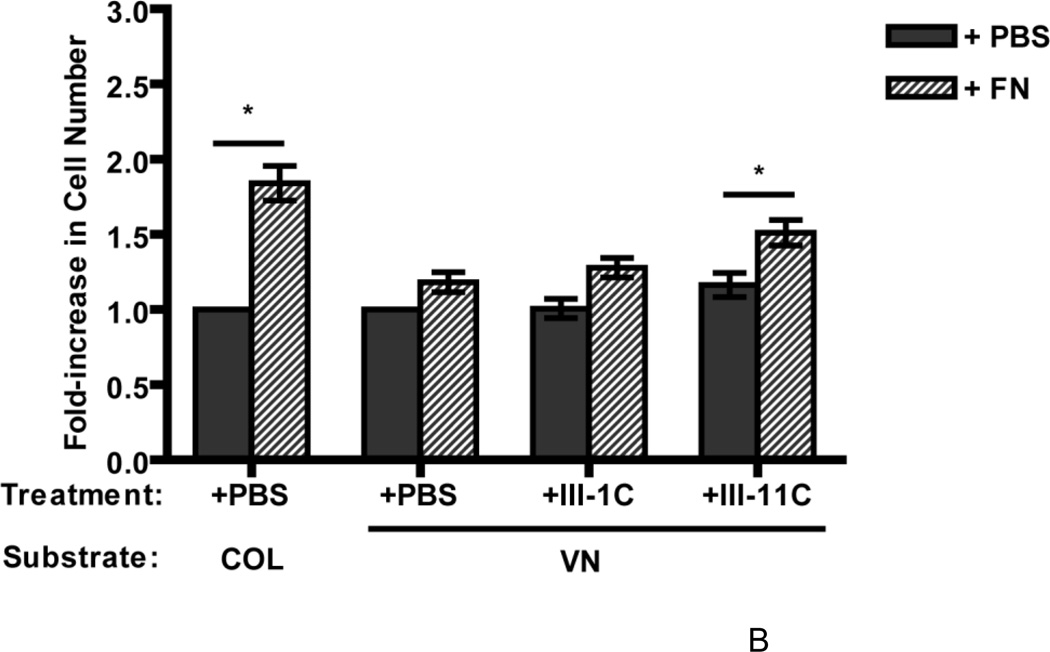

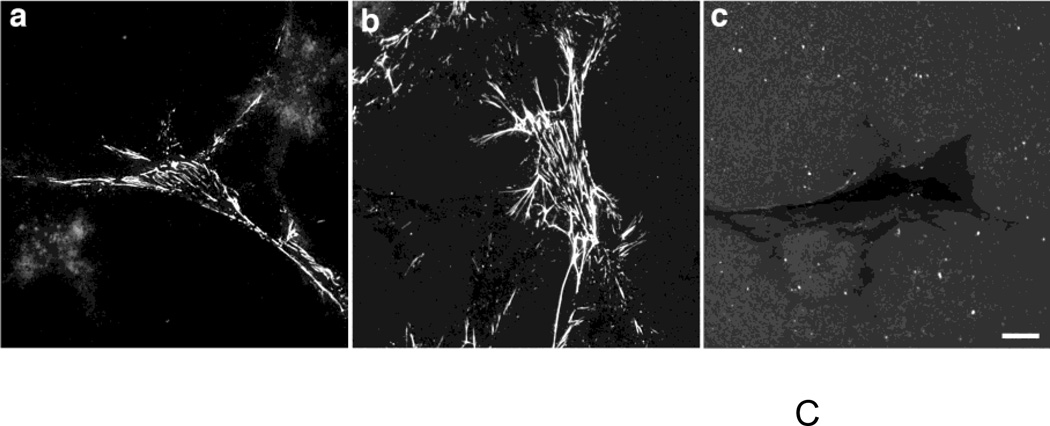

Given the early differences in ECM fibronectin deposition observed between collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells, we next asked whether increasing fibronectin matrix deposition by vitronectin-adherent cells would increase the proliferative response to fibronectin. Fibronectin levels were increased by adding the fibronectin fragment, III1C (“anastellin”), to fibronectin-treated wells to form “superfibronectin” (Morla et al., 1994). Fibronectin matrix deposition was increased with III1C, rather than through the use of pharmacological agonists (Somers and Mosher, 1993; Zhang et al., 1999a) in order to reduce the possibility of triggering parallel proliferation pathways unrelated to fibronectin matrix deposition. Addition of III1C dramatically increased the amount of DOC-insoluble fibronectin associated with both vitronectin- and collagen-adherent cells (Fig. 3A), but did not induce an increase in cell number on day 4 compared to cells treated with fibronectin alone for either vitronectin- (Fig. 3B) or collagen-adherent cells (2.08 ± 0.21 versus 1.84 ± 0.11 fold-increase, respectively; P > 0.05 by ANOVA, n=3). Addition of the control peptide, III11C, to fibronectin-treated wells did not increase the levels of insoluble fibronectin (Fig. 3A), and did not increase cell number versus fibronectin treatment alone (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that increasing insoluble fibronectin levels alone is not sufficient to promote fibronectin-mediated growth of vitronectin-adherent cells. The structure of DOC-insoluble fibronectin formed by III1C addition was next assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy and compared to native fibrils. Fibronectin fibrils were readily observed on vitronectin-adherent cells treated with fibronectin at concentrations of either 20 nM (Fig. 3C,a) or 300 nM (Fig. 3C,b). In contrast, addition of III1C to 20 nM fibronectin resulted in the formation of numerous, punctate aggregates of fibronectin, with few fibrillar structures present (Fig. 3C,c).

Figure 3. Increasing fibronectin matrix deposition alone does not increase cell growth.

FN-null MEFs (A and C, 3 × 104 cells/cm2; B, 2.6 × 103 cells/cm2) were allowed to adhere to either collagen- or vitronectin-coated substrates for 4 h. (A, B) Cells were then incubated with fibronectin (20 nM) in the absence or presence of 6 µM III1C or III11C, or an equal volume of PBS. (A) DOC-extractions were performed 20 h after fibronectin addition and equal volumes of DOC-insoluble material were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-fibronectin (FN) polyclonal and anti-αSMA monoclonal antibodies. Molecular mass markers are shown at left. (B) Cell number was determined 96 h after seeding. Data are presented as a fold-increase in cell number relative to the PBS control group for each substrate. *Significantly different from corresponding ‘PBS’ group by one-way ANOVA, n = 3. (C) Vitronectin-adherent cells were incubated with 20 nM FN (a), 300 nM FN (b), or 20 nM FN + 6 µM III1C (c) for 4 h. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy and fibronectin was detected using a polyclonal anti-fibronectin antibody. Bar = 10 µm. Image shown represents of 1 of 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

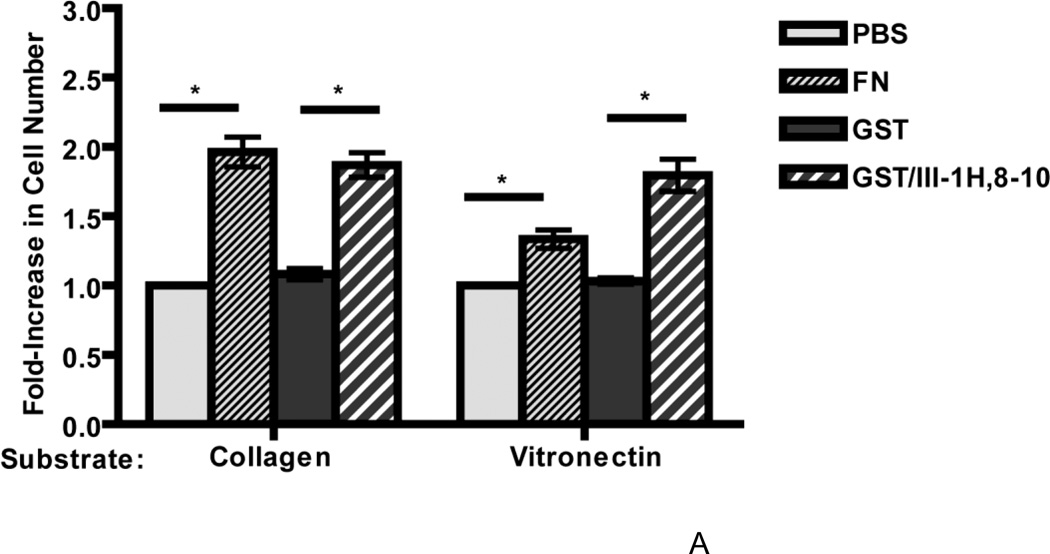

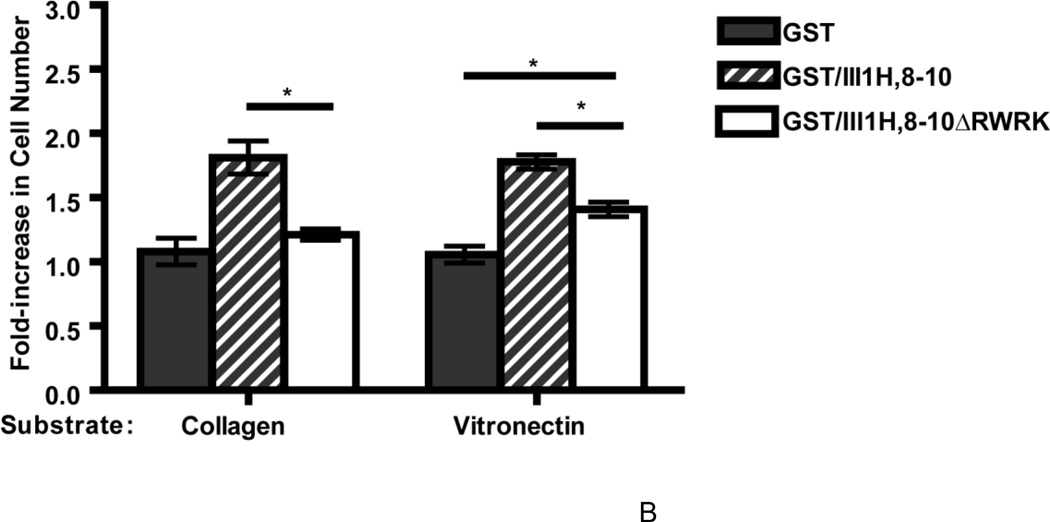

2.3. Growth response to a fibronectin matrix analog

A recombinant fibronectin fusion protein that mimics the stimulatory effects of ECM fibronectin on cell proliferation (Gui et al., 2006; Hocking and Kowalski, 2002) was used next to assess whether adhesion to vitronectin reduces the ability of cells to respond to the ECM form of fibronectin. This glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-tagged protein contains the matricryptic fragment of the first type III repeat of fibronectin (FNIII1H) coupled to the integrin-binding modules, FNIII8-10 (Hocking and Kowalski, 2002). FN-null MEFs were seeded on vitronectin- or collagen-coated substrates, treated with either plasma fibronectin or the fibronectin matrix analog (GST/III1H,8-10), and cell number was determined on day 4. Similar to results shown in Fig. 3B, addition of 20 nM fibronectin to collagen- or vitronectin-adherent cells resulted in a 1.96 ± 0.11 versus 1.34 ± 0.07-fold increase in cell number, respectively, versus vehicle (PBS)-treated controls (Fig. 4A). In contrast, addition of GST/III1H,8-10 to either collagen- or vitronectin-adherent cells led to a similar, significant fold-increase in cell number (1.87 ± 0.09 on collagen and 1.80 ± 0.12 on vitronectin) versus control (GST-treated) cells (Fig. 4A). Mutating the matricryptic, growth-promoting site in FNIII1H (Gui et al., 2006) caused a significant reduction in the cell growth response to GST/III1H,8-10 for both collagen- and vitronectin- adherent cells (GST/III1H,8-10 versus GST/III1H,8-10ΔRWRK; Fig. 4B), indicating that the same, RWRPK-mediated mechanism stimulated cell growth for both collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells. These data indicate that cell adhesion to vitronectin does not reduce the ability of cells to respond to the growth-promoting, matricryptic FNIII1 site of ECM fibronectin.

Figure 4. Collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells respond similarly to a fibronectin matrix analog.

FN-null MEFs (2.6 × 103 cells/cm2) were seeded onto collagen- or vitronectin-coated substrates and allowed to adhere for 4 h. Cells were then incubated with fibronectin (20 nM; FN) or an equal volume of PBS, or with GST, GST/III1H,8-10, or GST/III1H,8-10ΔRWRK (250 nM). Cell number was determined 96 h after seeding. Data are presented as average fold-increase in cell number versus PBS-treated cells for each substrate ± SEM. The average absorbance values for PBS-treated groups were 0.23 ± 0.02 (collagen) and 0.33 ± 0.02 (vitronectin). *Significantly different, by one-way ANOVA, n = 14 (A) and n = 3 (B).

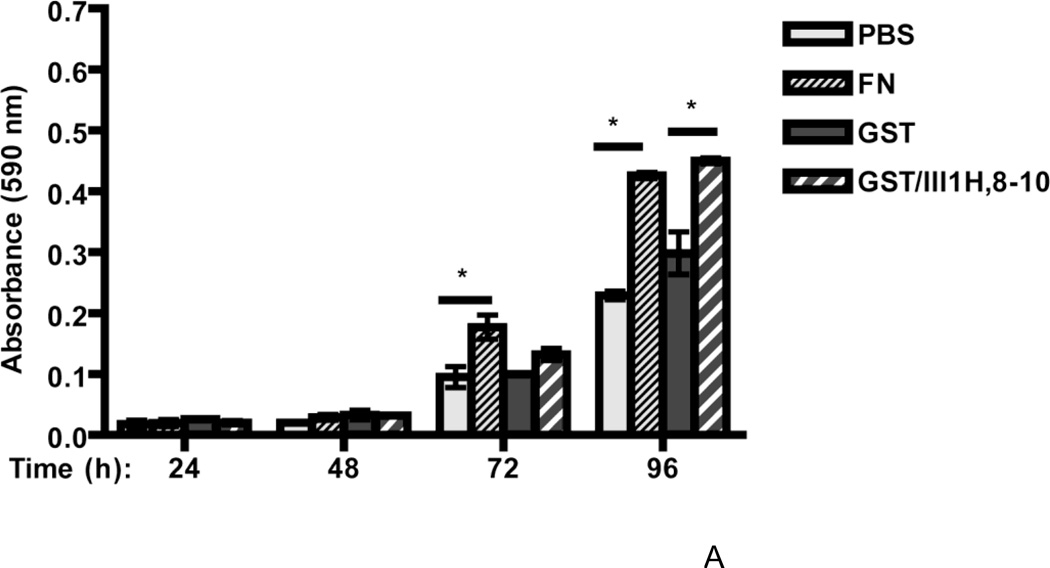

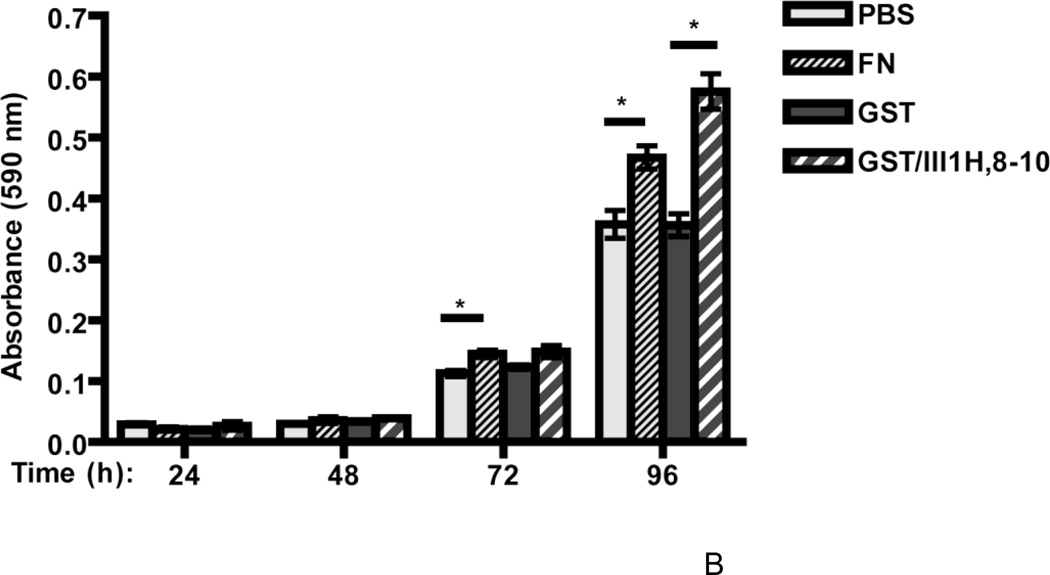

Time course studies were also conducted to assess cell growth responses to fibronectin and the fibronectin matrix analog at earlier time points. Both collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells incubated in the absence of fibronectin exhibited a steady increase in cell number every 24 h, demonstrating that collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells remained viable and proliferated in the absence of fibronectin (PBS or GST; Fig. 5A and B). Beginning at 72 h (day 3) and persisting to 96 h (day 4) after fibronectin addition, the increases in cell number for collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells were ~1.9-fold and ~1.3-fold, respectively, versus PBS-treated controls (Fig. 5A and B). At these same time points, addition of the fibronectin matrix analog to cells on either substrate resulted in a ~1.8-fold increase in cell number versus GST-treated controls (GST/III1H,8-10; Fig. 5A and B). Thus, the reduced growth response of vitronectin-adherent cells to fibronectin is not due to a decrease in the overall proliferative capacity of vitronectin-adherent cells.

Figure 5. Time course of cell growth for collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells.

FN-null MEFs (2.6 × 103 cells/cm2) were seeded onto wells precoated with either collagen (A) or vitronectin (B). After 4 h, cells were treated with fibronectin (FN; 20 nM), GST (250 nM), GST/III1H,8-10 (250 nM) or an equal volume of PBS. Cell number was determined at various times after seeding. Data are presented as average absorbance ± SEM and represent 1 of 3 experiments performed in quadruplicate. *Significantly different from corresponding control at given time point, by one-way ANOVA.

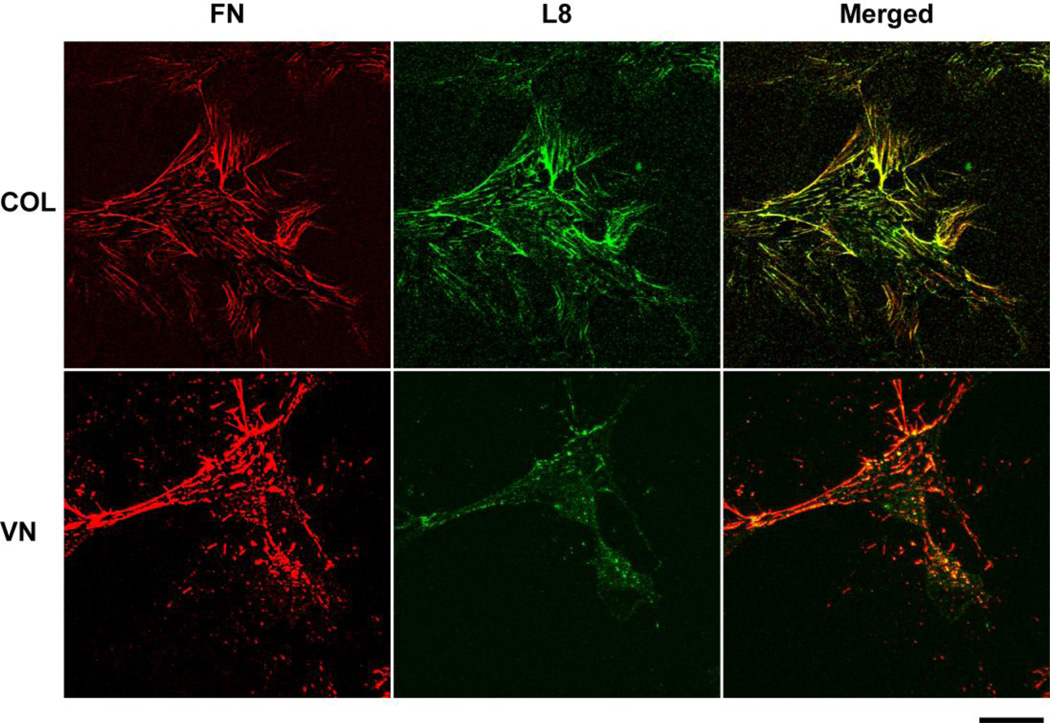

2.4. Fibronectin fibril conformation

Thus far, our data indicate that collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells respond similarly to the fibronectin matrix analog. However, when soluble fibronectin molecules are polymerized by vitronectin-adherent cells into ECM fibrils, these fibrils are significantly less effective at stimulating cell growth than those polymerized by collagen-adherent cells. The growth-promoting site in FNIII1 is not exposed in soluble fibronectin, but becomes unmasked when cells exert force on polymerized fibronectin fibrils (Gui et al., 2006; Hocking et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 1998). Cell-mediated extension of fibronectin fibrils has recently been correlated with induction of osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (Li et al.) and cell proliferation in response to ECM fibronectin (Sevilla et al., 2013). Hence, exposure of the FNIII1 site in ECM fibronectin may be reduced on vitronectin-adherent cells compared to collagen-adherent cells. To evaluate potential conformational differences in the FNIII1 region of fibronectin fibrils produced by vitronectin- or collagen-adherent FN-null MEFs, immunofluorescence images were obtained 20 h after fibronectin addition, when similar levels of ECM fibronectin had accumulated on collagen and vitronectin-adherent cells (Figs. 1B and 2). Fibronectin fibrils were visualized using polyclonal anti-fibronectin antibodies and co-stained with a conformation-dependent monoclonal antibody, clone L8. The L8 epitope has been localized to the I9-III1 modules of fibronectin (Chernousov et al., 1991) and is expressed on fibronectin fibrils in an extended conformation (Zhong et al., 1998). Collagen-adherent FN-null MEFs assembled L8-positive fibronectin fibrils, as demonstrated by the merged image in Fig. 6. In contrast, vitronectin-adherent cells produced fibronectin fibrils that were only weakly recognized by the L8 antibody (Fig. 6). These studies strongly suggest the presence of structural differences in the I9-III1 region of fibronectin fibrils formed by collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells and provide evidence that fibronectin fibrils formed by collagen-adherent cells are in a more extended conformational state.

Figure 6. Substrate-dependent differences in fibronectin fibril conformation.

FN-null MEFs (3 × 103 cells/cm2) were seeded onto substrates precoated with collagen (COL) or vitronectin (VN) and allowed to adhere for 4 h. Cells were incubated with fibronectin (20 nM) for an additional 4 h and then fixed, stained with conformation-dependent anti-fibronectin monoclonal antibodies L8, and co-stained with polyclonal anti-fibronectin antibodies (FN). Images are the compiled z-stacks from two-photon microscopy and represent 1 of 3 experiments performed in duplicate. Bar = 20 µm.

2.5. Role of α5β1 integrins in fibronectin assembly by collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells

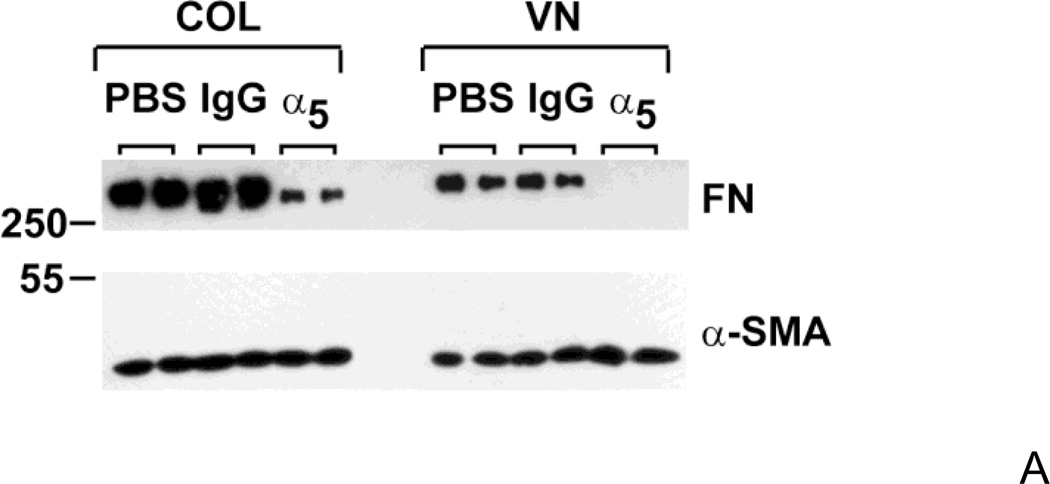

Fibronectin matrix assembly is typically mediated by α5β1 integrins (Singh et al., 2010). To compare the role of α5β1 integrins in fibronectin matrix assembly by vitronectin- or collagen-adherent FN-null MEFs, cells were incubated overnight with 20 nM fibronectin, in the absence and presence of function-blocking antibodies directed against the α5 integrin subunit. DOC-extractions were performed and levels of ECM fibronectin were assessed by immunoblotting. Addition of anti-α5 integrin antibodies to fibronectin-treated cells decreased fibronectin matrix deposition by both collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells compared to non-immune IgG-treated controls (Fig. 7A), indicating that fibronectin matrix assembly by both collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells is mediated by α5β1 integrins.

Figure 7. Role of α5β1 integrins in fibronectin matrix assembly.

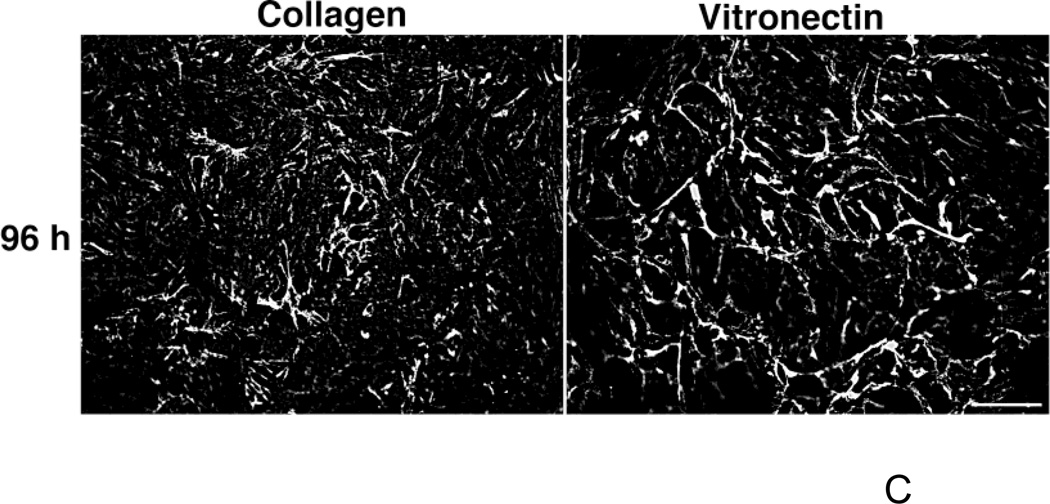

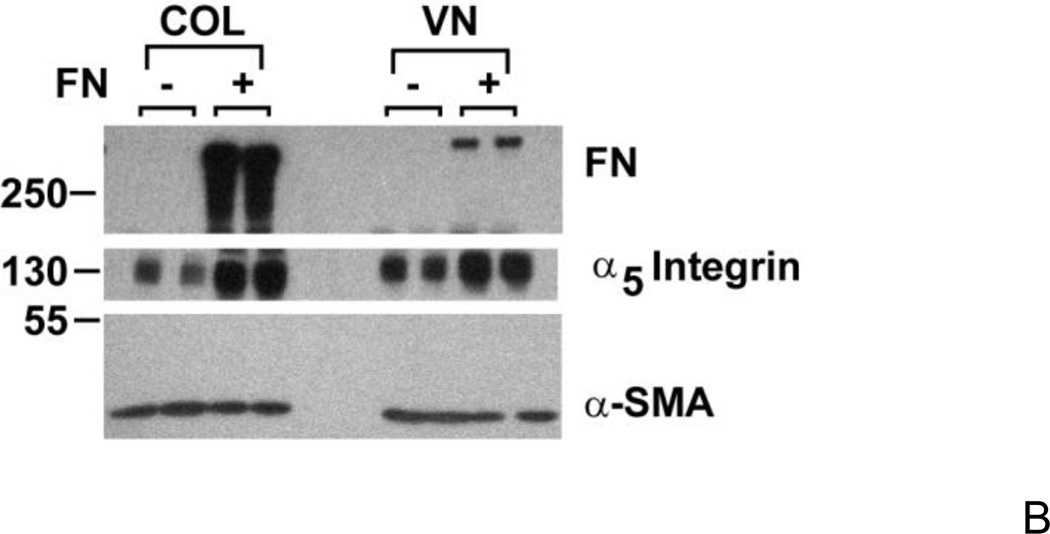

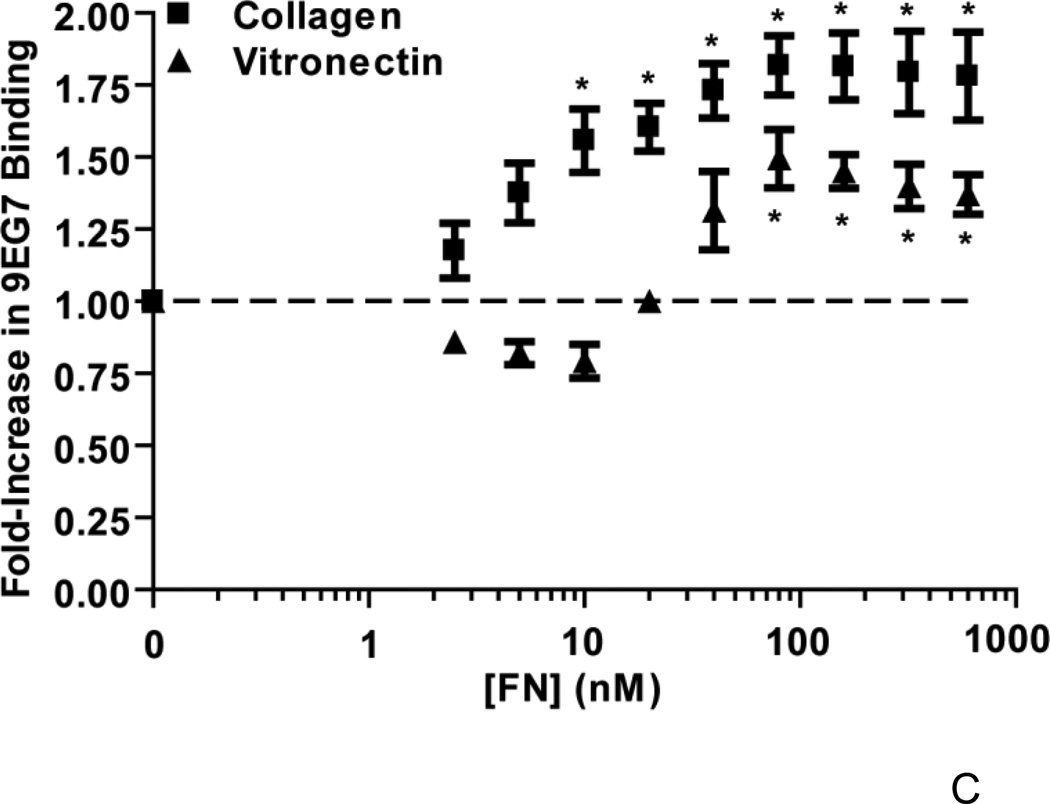

FN-null MEFs were seeded onto substrates precoated with collagen or vitronectin and allowed to adhere for 4 h. (A) Cells (3 × 104 cells/cm2) were treated with fibronectin in the presence of anti-α5 integrin monoclonal antibodies (α5) or non-immune mouse IgG (IgG; 10 µg/mL), or an equal volume of PBS. After a 20 h incubation, DOC extractions were performed. In (B), collagen- or vitronectin-adherent cells (3 × 104 cells/cm2) were treated with 20 nM fibronectin (FN; +) or an equal volume of PBS (−). After 2 h, DOC-extractions were performed. Equal volumes of DOC-insoluble material were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-fibronectin polyclonal (A,B), anti-α5 integrin polyclonal (B) and anti-αSMA monoclonal (A,B) antibodies. Immunoblots shown represent 1 of 3 experiments performed in duplicate. (C) Cells (1.4 × 105 cells/cm2) were incubated for 20 h with increasing concentrations of fibronectin (FN; 0 – 600 nM) or an equal volume of PBS (‘0 nM FN’). Cell ELISAs were performed as described in “Experimental Procedures”. Data are presented as average fold-increase in absorbance relative to the absorbance of PBS-treated cells (‘0 nM FN’) for each substrate ± SEM *Significantly different from PBS-treated cells by one-way ANOVA, n = 4.

To determine whether adhesion to vitronectin- or collagen-substrates altered recruitment of α5β1 integrins to the cytoskeleton in response to fibronectin, DOC-extractions were next performed on collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells treated with fibronectin for 2 h. Levels of α5β1 integrins associated with the cytoskeletal fraction were assessed by immunoblotting. In the complete absence of fibronectin, some α5β1 integrins were detected in the cytoskeletal fractions of both vitronectin- and collagen-adherent cells (Fig. 7B; FN−). Addition of fibronectin to collagen- or vitronectin-adherent cells increased the amount of α5β1 integrins associated with the cytoskeletal fraction to a similar extent (Fig. 7B; FN+). Together, these data indicate that both collagen and vitronectin substrates support fibronectin binding to α5β1 integrins, along with the subsequent coupling of α5β1 integrins to the actin cytoskeleton within 2 h of fibronectin addition.

To evaluate the activation state of β1 integrins on the surface of fibronectin-treated collagen- or vitronectin-adherent cells, ELISAs were performed using the monoclonal antibody, 9EG7, which recognizes β1 integrin subunits in a high affinity, extended conformation (Askari et al., 2010; Bazzoni et al., 1995). In the absence of fibronectin, similar low levels of 9EG7 binding were observed on collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells (Fig. 7C). Addition of fibronectin to collagen-adherent cells resulted in a dose-dependent increase in 9EG7 antibody binding to cells (Fig. 7C). Similar to results obtained in the proliferation assays (Fig. 1A), vitronectin-adherent cells exhibited a rightward shift of the fibronectin dose response curve compared to that of collagen-adherent cells (Fig. 7C). Significant increases in 9EG7 binding to collagen- and vitronectin-adherent cells over baseline levels occurred at fibronectin concentrations of 10 nM and 80 nM, respectively (Fig. 7C).

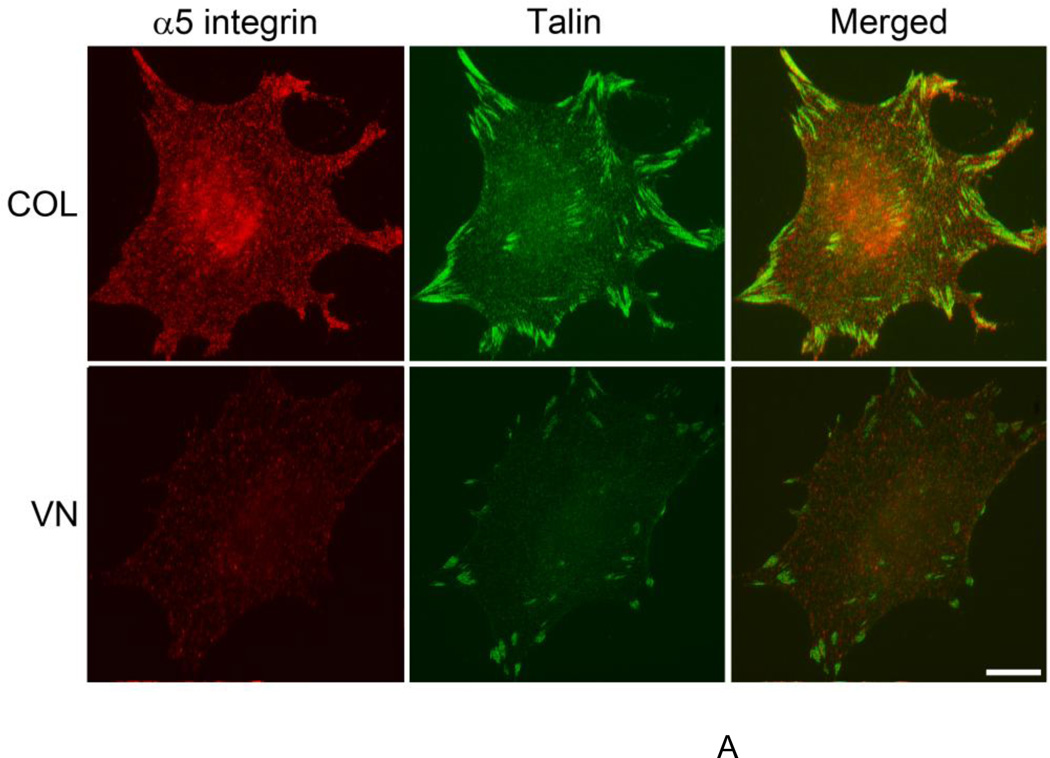

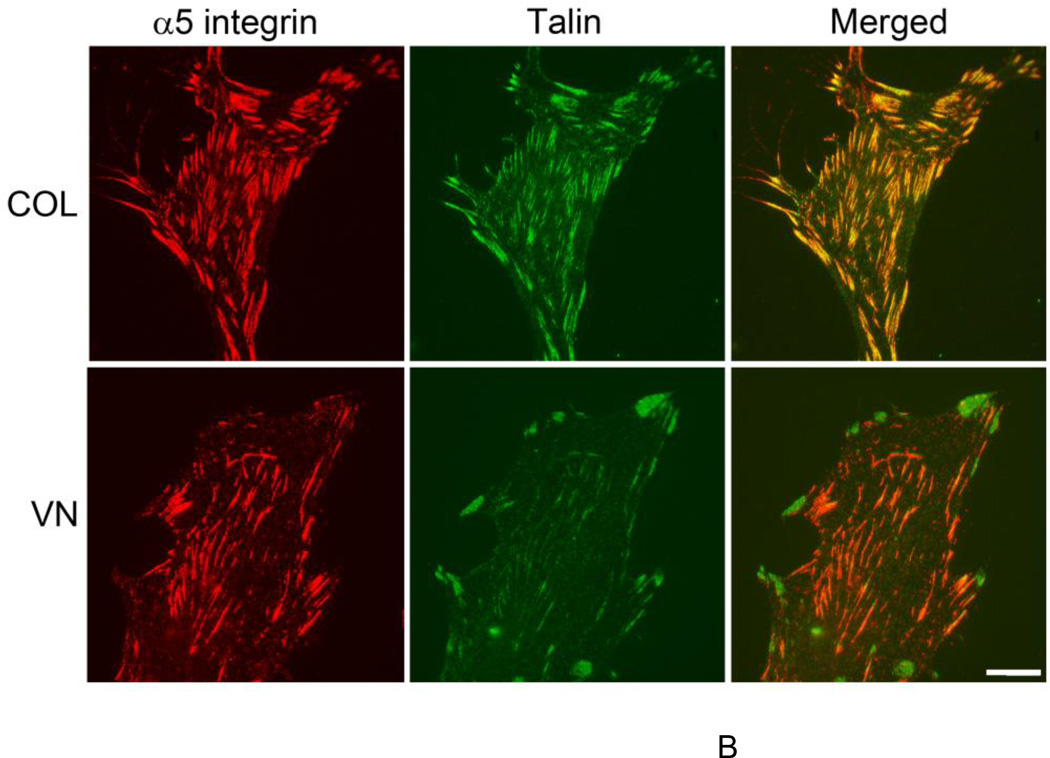

Binding of talin to the intracellular domain of β1 integrins is a final common step in integrin activation (Tadokoro et al., 2003). Thus, the presence of talin in α5β1-containing fibrillar adhesions was used as an additional marker of the activation state of α5β1 integrins following fibronectin addition. In the complete absence of fibronectin, sparse, punctate α5β1 integrin staining was visible over the entire surface of collagen-adherent cells (Fig. 8A); talin staining was pronounced at sites of focal adhesions located primarily at the cell periphery (Fig. 8A). As expected (Singer et al., 1988), limited α5β1 integrin clustering was observed in the absence of fibronectin on vitronectin-adherent cells, and talin staining was similarly confined to peripheral focal adhesions (Fig. 8A). Four h after fibronectin addition, dense α5β1 integrin staining that strongly co-localized with talin was visible in both focal adhesions and central fibrillar adhesions on collagen-adherent cells (Fig. 8B), demonstrating α5β1 integrin activation and translocation in response to fibronectin. Addition of fibronectin to vitronectin-adherent cells also led to α5β1 integrin clustering within central fibrillar adhesions, but with little talin co-localization (Fig. 8B). Moreover, α5β1 integrins were largely absent from talin-containing focal adhesions (Fig. 8B; merged image). These data provide key supporting evidence that fibronectin matrix assembly by vitronectin-adherent cells is mediated by α5β1 integrins functioning in a low affinity state.

Figure 8. Reduced talin translocation into fibrillar adhesions of vitronectin-adherent cells.

FN-null MEFs were seeded (3 × 104 cells/cm2) on tissue culture plates precoated with collagen (COL) or vitronectin (VN). Four hours after seeding, cells were either (A) fixed for immunofluorescence microscopy or (B) treated with soluble fibronectin (20 nM) and incubated an additional 4 h. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy and stained using antibodies directed against α5 integrin subunits and talin. Images represent 1 of 3 experiments. Bar = 10 µm.

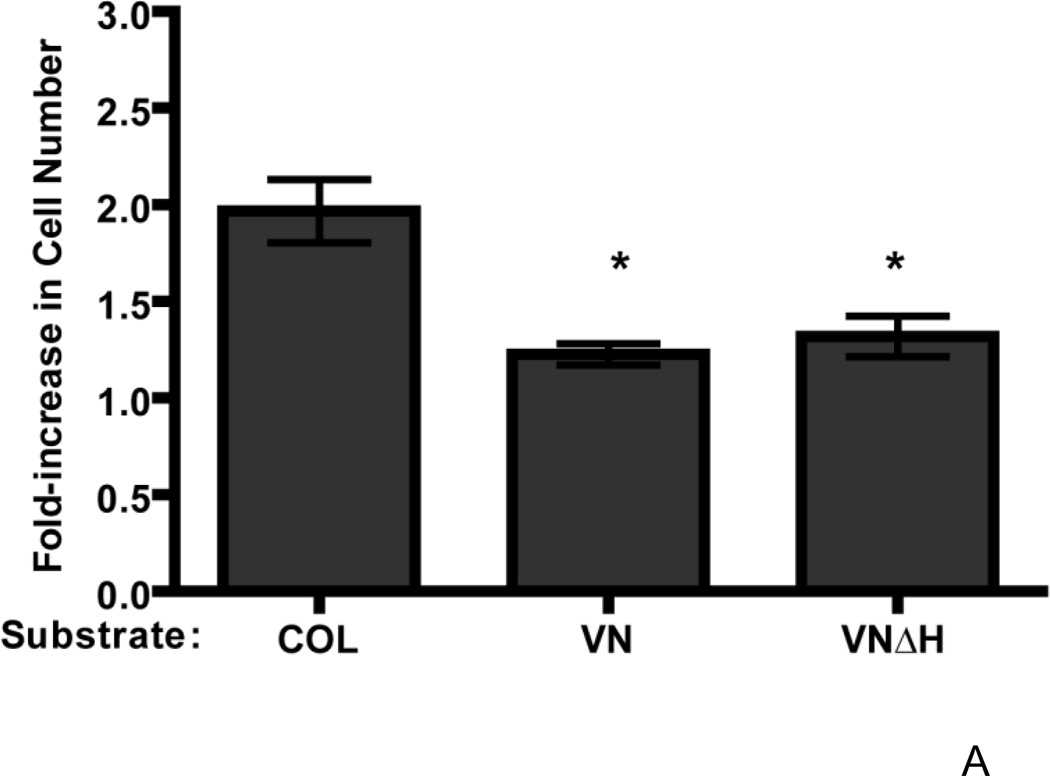

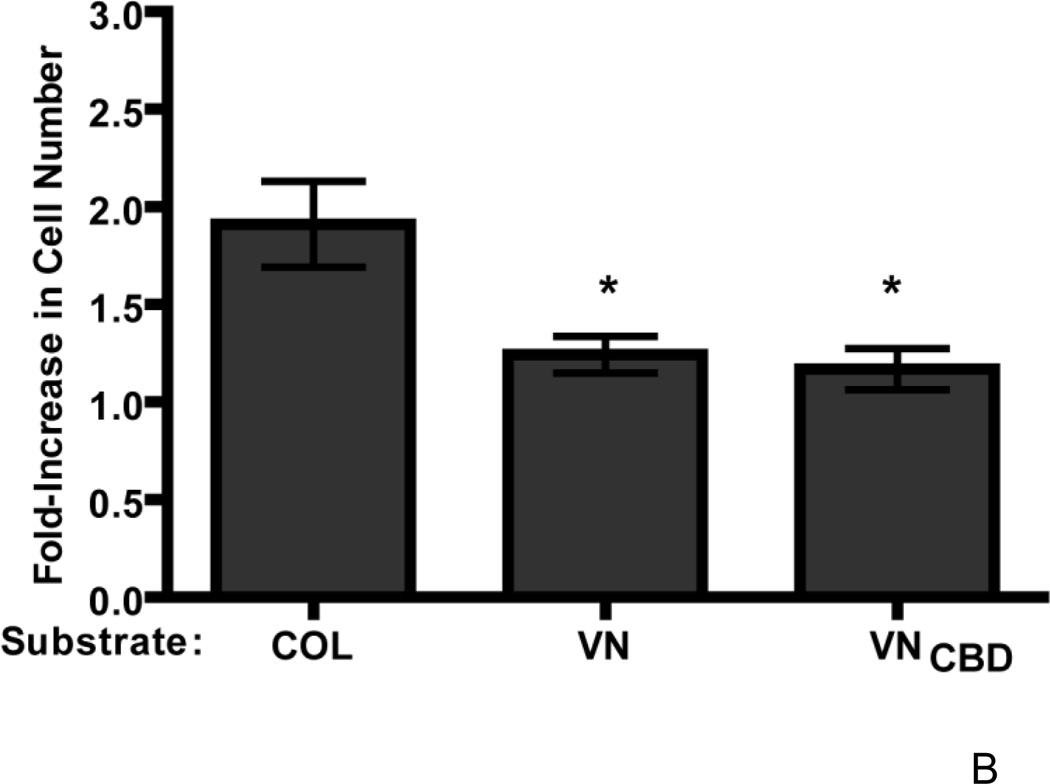

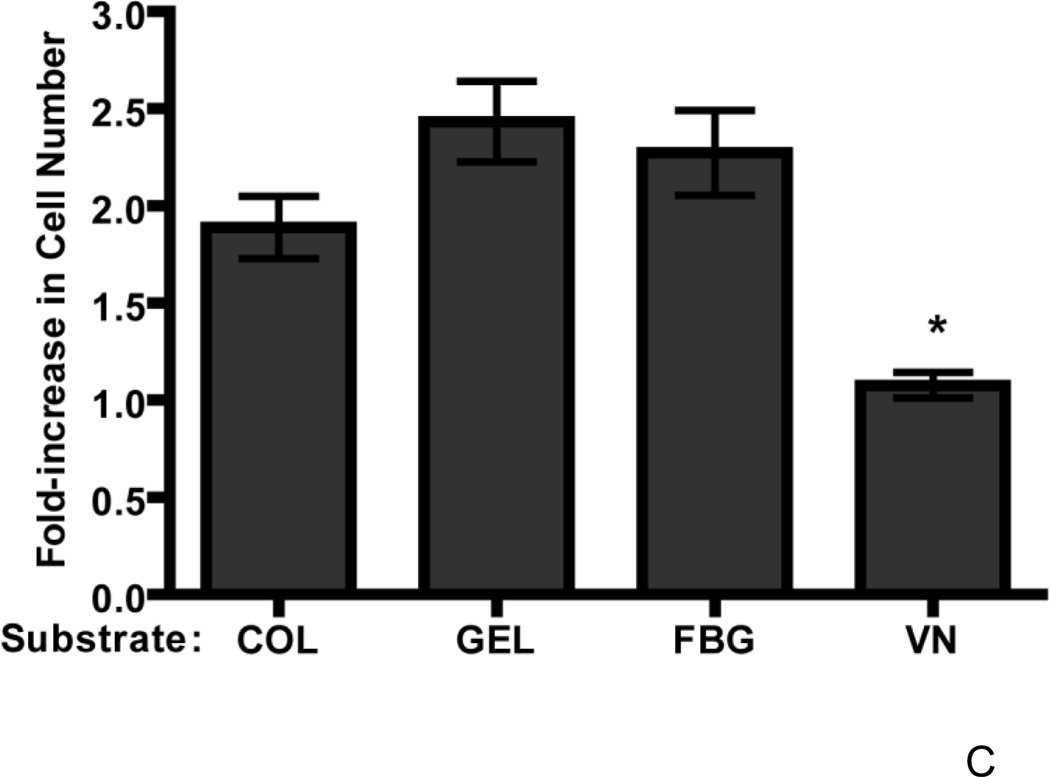

2.6. Role of vitronectin’s cell-binding domain

To identify the region of vitronectin responsible for the reduced growth response to fibronectin, we first evaluated the role of the heparin-binding domain of vitronectin, as this region has been shown previously to affect fibronectin matrix assembly (Hocking et al., 1999). FN-null MEFs were seeded onto either vitronectin or a recombinant full-length vitronectin lacking the carboxyl-terminal heparin-binding domain (vitronectinΔH). Addition of fibronectin to collagen-adherent cells led to the expected, ~2-fold increase in cell number on day 4 versus untreated controls (Fig. 9A). However, addition of fibronectin to cells adherent to either vitronectin- or vitronectinΔH-coated substrates induced a similar, ~1.25-fold increase in cell number compared to non-treated (PBS) controls (Fig. 9A), indicating that the heparin-binding domain of vitronectin does not play a role in the reduced functional response to fibronectin. Furthermore, addition of fibronectin to FN-null MEFs adherent to a cell-binding fragment of vitronectin, which does not contain the heparin-binding region, led to only a ~1.2-fold-increase in cell number relative to PBS-treated controls (Fig. 9B). This difference in cell number in response to fibronectin was significantly less than the ~2-fold increase in cell number exhibited by collagen-adherent cells in response to fibronectin (Fig. 9B), and indicates that adhesion to the cell-binding domain of vitronectin is sufficient to reduce the growth response to fibronectin.

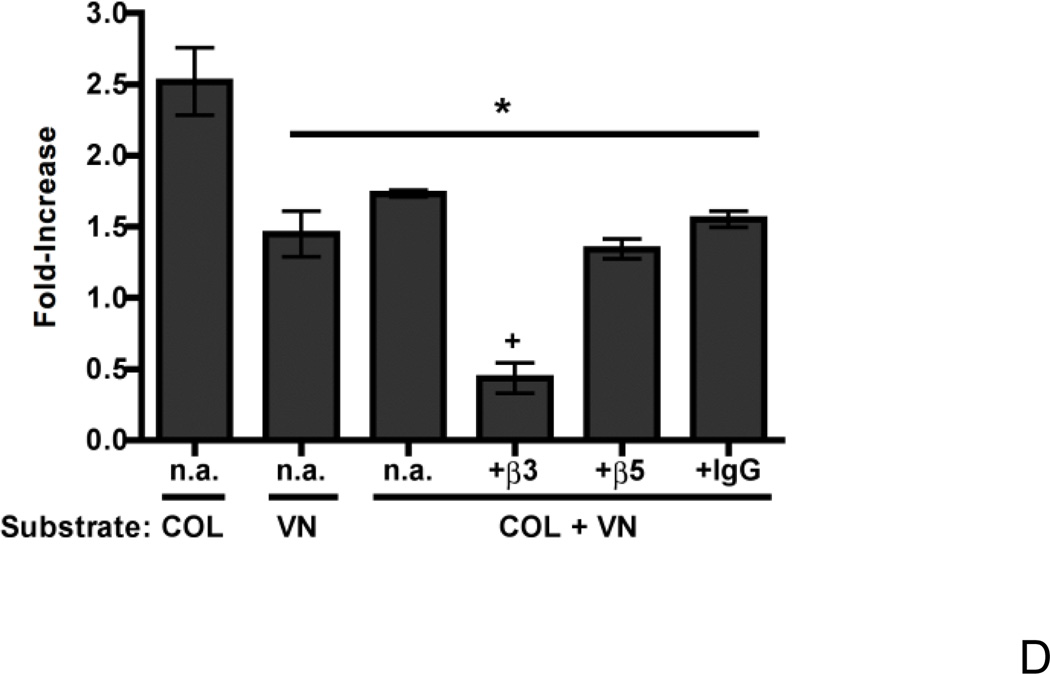

Figure 9. The reduced cell growth response to fibronectin is mediated by vitronectin’s cell-binding domain.

FN-null MEFs (2.6 × 103 cells/cm2) were seeded onto wells precoated with collagen (COL), vitronectin (VN), a full-length vitronectin construct lacking the heparin-binding domain (VNΔH), a cell-binding fragment of vitronectin (VNCBD), gelatin (GEL), fibrinogen (FBG), or both vitronectin and collagen (COL+VN). After 4 h, cells were treated with fibronectin (20 nM) or an equal volume of PBS. Cell number was determined 96 h after seeding. Data are presented as average fold-increase in cell number over control (PBS-treated) wells for each substrate ± SEM. Average absorbance values ± SEM for control (PBS) wells on day 4: (A–C) COL (0.33 ± 0.04), VN (0.47 ± 0.05), VNΔH (0.40 +0.07), VNCBD (0.27 + 0.02), gelatin (0.35 ± 0.02), and fibrinogen (0.25 ± 0.03); (D) COL (0.25 ± 0.04), VN (0.27 ± 0.07), and COL+VN (0.39 ± 0.0.07). *Significantly different versus collagen-adherent cells; #Significantly different from all other treatment groups by one-way ANOVA, n = 7 (A), n = 5 (B), n = 3 (C and D).

To determine whether cell adhesion to other αvβ3 integrin-binding substrates leads to a similar reduction in the growth response to fibronectin, the effect of cell adhesion to gelatin (Davis, 1992)- or fibrinogen (Felding-Habermann et al., 1992)-coated substrates on fibronectin-stimulated growth was compared to that of vitronectin- or collagen-coated substrates. Addition of fibronectin to collagen-adherent FN-null cells induced the expected ~1.9-fold increase in cell number versus vehicle (PBS)-treated controls (Fig. 9C). Similarly, addition of fibronectin to cells adherent to saturating concentrations of either gelatin or fibrinogen resulted in a ~2.4- and 2.3-fold increase in cell number versus vehicle controls, respectively (Fig. 9C). In contrast, addition of fibronectin to vitronectin-adherent cells induced a significantly smaller ~1.2-fold increase in cell number (Fig. 9C). Thus, the reduced cell growth response to fibronectin is not a general property of αvβ3 integrin-binding adhesive substrates.

Finally, to determine whether adhesion to vitronectin reduces the fibronectin-mediated growth response of collagen-adherent cells, FN-null MEFs were seeded onto wells co-coated with both collagen and vitronectin. The increase in cell number in response to fibronectin was compared to that observed with cells adherent to substrates coated with vitronectin or collagen alone. The relative increase in cell number triggered in response to fibronectin for cells adherent to the vitronectin-collagen co-substrate was significantly less than that observed for cells adherent to collagen only, and was not different from that of cells adherent to vitronectin only (Fig. 9D), indicating that addition of vitronectin to a collagen substrate can reduce the otherwise growth-promoting effects of fibronectin fibrils. This inhibitory effect of vitronectin on the collagen-vitronectin co-substrate was not reversed by addition of either anti-β3 or anti-β5 integrin blocking antibodies (Fig. 9D). Rather, addition of anti-β3 integrin antibodies to fibronectin-treated, collagen/vitronectin-adherent cells reduced proliferation to levels not significantly different from that observed for collagen-adherent cells cultured in the absence of fibronectin (average absorbance values: 0.18 ± 0.08 and 0.27 ± 0.07, respectively; P = 0.47; n=3).

3. Discussion

In this study, we show that cell-substrate interactions affect the assembly, conformation and function of ECM fibronectin fibrils. Both vitronectin- and collagen-adherent FN-null MEFs assembled similar levels of fibronectin fibrils via α5β1 integrin-dependent mechanisms, yet ECM fibronectin was 10-fold less effective at enhancing the proliferation of vitronectin-adherent cells versus collagen-adherent cells. Fibronectin fibrils were assembled by vitronectin-adherent cells using α5β1 integrins in a lower affinity state, demonstrating a new role for the cell-binding domain of vitronectin in modulating α5β1 integrin activity and function. Fibronectin fibrils assembled by collagen-adherent cells showed increased expression of a conformation-dependent epitope within the I9/III1 region of fibronectin that is associated with fibril extension (Zhong et al., 1998) and enhanced cell proliferation (Gui et al., 2006), compared to fibrils assembled by vitronectin-adherent cells. Fibronectin matrix assembly by α5β1 integrins in the lower activation state proceeded at a slower rate over the initial 24 h compared to α5β1 integrins functioning in the fully activated state. These data indicate that cell-substrate interactions govern the kinetics of ECM fibronectin deposition, the conformation of ECM fibronectin fibrils, and the functional response to ECM fibronectin, and may do so, in part, by modulating the activation state of α5β1 integrins.

Consistent with our previous work (Gui et al., 2006), the recombinant fibronectin matrix analog, GST/III1H,8-10, stimulated the proliferation of vitronectin- or collagen-adherent cells via the cryptic, heparin-binding sequence, RWRPK, located in FNIII1. Peptides containing the RWRPK sequence block the stimulatory effects of fibronectin on the proliferation of collagen-adherent cells (Gui et al., 2006) and rapidly decrease arteriolar diameter when applied in situ (Hocking et al., 2008). This matricryptic sequence in FNIII1 is not exposed in soluble fibronectin (Litvinovich et al., 1992), but may be exposed by cell- or tissue-derived tension (Hocking et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 1998). In the present study, the conformation-dependent monoclonal antibody, L8, recognized fibronectin fibrils formed by collagen-adherent cells to a greater extent than fibrils deposited by vitronectin-adherent cells (Fig. 6), indicating that fibronectin fibrils formed by vitronectin- and collagen-adherent cells exhibit conformational differences in the growth-promoting FNI9-III1 region. Binding of L8 antibodies to fibronectin is enhanced when fibronectin is strained mechanically (Zhong et al., 1998), indicating that L8 antibodies can recognize an extended conformation of the FNI9-III1 region. Thus, fibronectin fibrils assembled by vitronectin-adherent cells appear to be in a less-extended state than fibrils produced by collagen-adherent cells. These data support the hypothesis that exposure of the matricryptic, growth-promoting site in FNIII1 is reduced in the less-extended fibronectin fibrils produced by vitronectin-adherent cells and enhanced with collagen-adherent cells. Addition of the fibronectin matrix analog, GST/III1H,8-10, to either collagen- or vitronectin-adherent cells triggered similar increases in cell number, indicating that vitronectin-adherent cells are capable of responding to the ECM form of fibronectin. Thus, acute exposure to vitronectin would not be expected to reduce the cellular response to a previously established, growth-promoting fibronectin matrix. Rather, our data suggest that vitronectin must be present during the formation of the fibronectin matrix to affect the conformation and downstream functional properties of fibronectin fibrils.

Many of the effects of vitronectin on fibronectin matrix assembly appear to be integrated at the level of β1 integrin activity. As such, the presence or absence of environmental factors that modify β1 integrin activity impact the degree to which, and likely the mechanism by which, vitronectin inhibits fibronectin matrix deposition. Previous studies using either cycloheximide-treated fibroblasts or FN-null MEFs have demonstrated that vitronectin inhibits fibronectin matrix deposition when cells are cultured in serum-free, basal media (Bae et al., 2004; Christopher et al., 1997; Hocking et al., 1999). Under similar cell culture conditions, the inhibition of fibronectin matrix assembly by vitronectin was relieved by factors that increase β1 integrin activity, including lysophosphatidic acid (Hocking et al., 1999), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (Vial et al., 2006), or β5 integrin blocking antibodies (Vial and McKeown-Longo, 2008). Similarly, expression of active β1 integrins in β1-null cells overrides the otherwise suppressive effects of vitronectin on fibronectin matrix assembly (Zhang et al., 1999b). In the present (Fig. 2) and other (Sottile et al., 2000) studies, vitronectin-adherent FN-null MEFs cultured in defined growth media assembled a fibronectin matrix, albeit at a slower initial rate versus collagen-adherent cells (Fig. 2C). As expected (Bae et al., 2004), replacing the cell culture growth media with basal media in our experiments markedly reduced the amount of fibronectin matrix deposited by vitronectin-adherent FN-null MEFs (not shown), indicating that factors in the cell culture media can also override some of the inhibitory effects of vitronectin on fibronectin matrix deposition. These media effects may also be integrated through α5β1 integrins, as even in the complete absence of fibronectin, we still observed some α5β1 integrin clustering (Fig. 8) and cytoskeletal association (Fig. 7B) on FN-null MEFs adherent to recombinant vitronectin.

In the present study, the kinetics of fibronectin matrix assembly by vitronectin- and collagen-adherent cells cultured in the same growth media still differed over the first 24 h. Soluble fibronectin molecules exist in a tightly packed, globular configuration that involves self-interactions between the amino-termini and several type III repeats (Vakonakis et al., 2007). Substrate collagen may enhance the rate of conversion of fibronectin into DOC-insoluble fibrils through its ability to interact with the I6-9 region of fibronectin (Katagiri et al., 2003). These collagen-fibronectin interactions may disrupt interactions between FNI4-5 and FNIII3 (Vakonakis et al., 2009) to allow fibronectin molecules to unfold (Williams et al., 1982) in a manner that facilitates additional fibronectin-fibronectin interactions, resulting in the more rapid formation of DOC-insoluble fibronectin multimers. Alternatively, collagen-adherent cells may exhibit a faster rate of fibronectin matrix deposition due to higher levels of β1 integrin activity at a given fibronectin concentration versus vitronectin-adherent cells (Fig. 7C). Importantly, III1C-enhanced conversion of soluble fibronectin into DOC-insoluble aggregates did not increase cell growth (Fig. 3), providing additional evidence that the conformation of fibronectin fibrils, and not the absolute amount of insoluble fibronectin, determines the cell growth response.

Our studies also reveal a novel ‘outside-in’ mechanism that controls α5β1 integrin affinity and function during fibronectin matrix assembly. Both vitronectin- and collagen-adherent cells utilized α5β1 integrins to polymerize fibronectin fibrils (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, addition of fibronectin to vitronectin- or collagen-adherent cells triggered the association of similar amounts of α5β1 integrins with the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 7B) and the accumulation of α5β1 integrins into central fibrillar adhesions (Fig. 8), providing clear evidence that α5β1 integrins of cells adherent to either substrate bind fibronectin and function in fibronectin matrix assembly. In contrast, cells adherent to vitronectin showed reduced levels of talin associated with α5β1 integrins in central adhesions (Fig. 8B). Further, 9EG7 antibody binding to vitronectin-adherent cells was significantly reduced compared to collagen-adherent cells (Fig. 7C). A large body of evidence indicates that integrin receptors transition from a bent, low-affinity conformation to an extended, high affinity conformation during activation (Askari et al., 2009). This ‘switchblade’ model of integrin activation proposes the existence of 3 distinct integrin conformations, with the bent conformation corresponding to the unbound state (Askari et al., 2009). Evidence now indicates that both αvβ3 and α5β1 integrins can also bind ligand in a non-extended, bent conformation (Adair et al., 2005; Askari et al., 2010). The 9EG7 epitope is exposed only upon extension of the β1 integrin subunit to the high affinity state (Askari et al., 2010). As such, our data demonstrate that α5β1 integrins can bind fibronectin and function in matrix assembly in a low affinity state, which is consistent with recent work showing that α5β1 integrins restrained in a 9EG7-negative conformation can mediate cell adhesion to fibronectin (Askari et al., 2010). The low activity state of α5β1 integrins on vitronectin-adherent cells, coupled with the assembly of less-extended fibronectin fibrils is also consistent with recent data correlating reduced β1 integrin activity (as assessed by 9EG7 binding) with reduced central tractional forces and decreased fibronectin fibril linearity (Faurobert et al., 2013). The inhibitory effect of vitronectin on integrin activation was dependent on fibronectin concentration, with fibronectin concentrations ≥ 80 nM capable of inducing the high affinity state (Fig. 7C). These data underscore the importance of ECM protein balance in tissue homeostasis.

The mechanism by which cell adhesion to vitronectin reduces α5β1 integrin affinity is not yet known. The effect of vitronectin on reducing the proliferative response to ECM fibronectin was localized to the cell-binding region, but was not a general property of αvβ3 integrin-binding proteins (Fig. 9). Similarly, a recombinant fibronectin fragment engineered to specifically ligate αvβ3 integrins supports fibronectin-stimulated cell proliferation (Roy and Hocking, 2012), confirming that ligation of αvβ3 integrins alone is not sufficient to reduce the functional response to ECM fibronectin. Furthermore, neither β3 nor β5 integrin blocking antibodies relieved the inhibitory effects of vitronectin for cells adherent to the vitronectin-collagen co-substrate. The cell-binding fragment of vitronectin used in the present study (Fig. 9B) encompasses residues 42–126, and includes the integrin-binding Arg-Gly-Asp sequence (RGD, residues 45–47), but does not contain either the N-terminal somatomedin B domain or the C-terminal heparin-binding domain (Tomasini and Mosher, 1991). Furthermore, this vitronectin fragment does not contain binding sites for either plasminogen activator inhibitor (Seiffert et al., 1994) or the urokinase receptor (Okumura et al., 2002), both of which have been implicated previously in the control of fibronectin matrix assembly (Vial et al., 2006). The region between residues 48 and 130 is unique to vitronectin and contains a highly acidic segment (residues 53–64) (Preissner, 1991) that could potentially contribute to the unique activity of vitronectin either by modifying the shape of the RGD loop (Marcinkiewicz et al., 1997) or by serving as a polyanionic binding site for αvβ3 integrins or other cationic co-factors (Chiodelli et al., 2012). In summary, the current study reveals a novel extracellular mechanism by which adhesion to the cell-binding domain of vitronectin reduces β1 integrin activity to allow for fibronectin matrix assembly, while limiting downstream signaling responses to ECM fibronectin fibrils.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Reagents

Fibronectin was isolated from Cohn’s Fraction I and II (Miekka et al., 1982). Collagen I was extracted from rat tail tendons with acetic acid and precipitated with NaCl, as described previously (Roy and Hocking, 2012). Fibrinogen (plasminogen-, von Willebrand factor-, and fibronectin-depleted) was purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Alexa Fluor488-labeled fibronectin was produced by incubating plasma fibronectin with Alexa Fluor488 tetrafluorophenyl ester, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Carlsbad CA), and unreacted dye was removed by size exclusion chromatography. Antibodies and their sources are as follows: anti-fibronectin monoclonal, clone L8 (Chernousov et al., 1991), was a gift from Dr. Michael Chernousov (Geisinger Clinic, Danville, PA); anti-α5 integrin monoclonal (5H10-27), rat IgG2a, and anti-β1 integrin monoclonal (9EG7) and anti-β3 monoclonal (2C9.G2) were from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA); anti-α5 integrin (AB1921) was from Chemicon (Temecula, CA); anti-β5 integrin monoclonal (clone KN52) was from eBioscience; anti-fibronectin polyclonal, anti-alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) monoclonal, anti-talin monoclonal (8d4), and non-immune mouse IgG were from Sigma; Alexa Fluor594 goat anti-mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor594 goat anti-rat IgG, and Alexa Fluor488 goat anti-rabbit IgG were from Invitrogen; HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG were from Biorad (Hercules, CA).

4.2. Cell culture

Fibronectin-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (FN-null MEFs) were from Dr. Jane Sottile (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY) (Sottile et al., 1998). FN-null MEFs were cultured under serum- and fibronectin-free conditions on collagen I-coated tissue culture plates in a 1:1 mixture of Aim V (Invitrogen) and Cellgro Complete (Mediatech, Manassas, VA).

4.3. Recombinant proteins

The following fusion proteins were produced in bacteria and isolated by affinity chromatography as described previously: GST-tagged vitronectin (Wojciechowski et al., 2004), GST/III1H,8-10 (Hocking and Kowalski, 2002), GST/III1H,8-10ΔRWRK (Roy et al., 2010), polyhistidine (His)-tagged III1C (Morla et al., 1994), His-III11C (Morla et al., 1994). The molecular mass of III1C is similar to that of the control, III11C (Morla et al., 1994). The cell-binding fragment of vitronectin (GST/VNcell) was made through PCR amplification of human vitronectin cDNA encoding bases 242–496 (Q42 to G126). The sense primer 5’-CCCGGATCCCAAGTGACTCGCGGGGATG-3’ contains a BamHI site shown in bold. The antisense primer 5’-CCCGAATTCCTACCCTGGATGAAGGGTCTCAG-3’ contains an EcoRI site (in bold). The underlined bases encode a stop codon after the last base to be amplified. After digestion with EcoRI and BamHI, the PCR product was cloned into pGEX-2T, transfected into DH-5α, and protein was isolated on glutathione-Sepharose.

A full-length GST-tagged vitronectin lacking 12 amino acids in the heparin-binding domain (bases 1160–1195, K347- G359; GST/vitronectinΔH) (Tomasini and Mosher, 1991) was constructed as follows. Overlap extension PCR was used to introduce a HindIII site (bases 1148–1153, P344 and S345) into the plasmid encoding GST/vitronectin (Wojciechowski et al., 2004). In the sense round, the first primer pair was 5’-GCGGGTCTACTTCTTCAAGG-3’ (sense) with an AccI site in bold, and 5-TCTTGGTCAAGCTTGGGCGGGGTGC-3’ (antisense) with the HindIII site in bold. The second primer pair was 5’-GCACCCCGCCCAAGCTTGACCAAGA-3’ (sense) with the HindIII site in bold, and 5’-CCCGAATTCCTACAGATGGCCAGGAGCTGGG-3’ (antisense) with an EcoRI site in bold. In the second round, the first-round products were mixed with the italicized primers above, and the resulting construct was moved into the GST/vitronectin plasmid on an AccI-EcoRI fragment. PCR amplification was used to delete bases 1160-1195 (K347- G359). A sense primer 5’-GCACCCCGCCCAAGCTTGACCTATCGATCACAACGAGGCCACAGC-3’ contains an upstream HindIII site and a downstream ClaI site shown in bold. The anti-sense primer 5’ – CCCGAATTCCTACAGATGGCCAGGAGCTGGG-3’ contains an EcoRI site. Underlined bases encode a stop codon after the last base to be amplified. After digestion with HindIII and EcoRI, the PCR product was cloned into the modified pGEX-2T and transfected into E. coli, clone DH-5α. GST/vitronectinΔH was solublized from inclusion bodies using guanidine and isolated using glutathione-Sepharose as described previously (Wojciechowski et al., 2004). All proteins were dialyzed extensively against PBS. Purified proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and frozen in aliquots at −80°C until use.

4.4. Immunofluorescence microscopy

Tissue culture plates (35 mm) were coated overnight at 4°C with collagen (50 µg/mL in 0.02 N acetic acid) or GST/vitronectin (5 µg/mL in PBS), then washed with PBS, and blocked with 2% BSA (Probumin Media Grade, Celliance, Kankakee, IL). FN-null MEFs were seeded at indicated densities, allowed to adhere for 4 h, and then incubated with fibronectin for 1, 4 or 24 h at 37°C. In some experiments, III1C (6 µm) and fibronectin (20 nM) were added to vitronectin-adherent cells. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, processed for immunofluorescence microscopy (Roy and Hocking, 2012), and incubated with primary antibodies followed by secondary fluorophore-labeled antibodies diluted in PBS with 1% BSA. Cells were examined using an Olympus microscope equipped with epifluorescence and photographed with a digital camera (SPOT, Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Alternatively, cells were examined using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 AOM-MPM Dual Photon microscope equipped with a 100X oil immersion lens (Olympus). Alexa594 was excited at 780 nm using a femtosecond Mai Tai HP Deep See Ti:Sa laser (Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA, USA). The emitted fluorescence was filtered with a 609 nm-bandpass filter (#FF01-609/54-25, Semrock) and detected using two bi-alkaline photomultiplier tubes. Alexa488 was excited at 900 nm and filtered with a 519 nm-bandpass filter (#BA495-546, Olympus) using the same apparatus.

4.5. Quantification of fibronectin deposition

Deoxycholate (DOC) extractions were performed essentially as described (Xu et al., 2009). Tissue culture plates (12-well) were precoated with collagen or GST/vitronectin. FN-null MEFs were seeded at indicated densities, allowed to adhere for 4 h, and then treated with 20 nM fibronectin or an equal volume of the vehicle control, PBS. In some experiments, III1C or III11C (6 µM), or an equal volume of PBS was added. At indicated times, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and then incubated for 5 min on ice with 1% DOC extraction buffer (1% DOC, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.8, 2 mM PMSF, 2 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 2 mM iodoacetic acid, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.8 mg/mL Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) (McKeown-Longo and Mosher, 1983)). Upon careful removal of the DOC-soluble material, the remaining DOC-insoluble material was scraped into Laemmli sample buffer containing 2% β-mercaptoethanol. Protein concentrations of the DOC-soluble fractions were determined using a BCA assay (Pierce). DOC-soluble and DOC-insoluble samples (25% of total extracted volume per lane) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using anti-fibronectin polyclonal and anti-αSMA monoclonal antibodies. The average net band intensities for duplicate samples were determined by densitometry using Carestream Molecular Imaging Software (Rochester, NY).

Fibronectin deposition was also quantified using fluorimetry, as described previously (Roy and Hocking, 2012). Briefly, FN-null MEFs were seeded (3.0 × 104 cells/cm2) on black-walled 96-well tissue culture plates precoated with collagen or GST/vitronectin. Cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and then treated with Alexa488-labeled fibronectin at indicated concentrations. After 20 h, cells were washed with PBS to remove unbound protein. Methanol was added to wells and fluorescence intensity was quantified by exciting wells at 485 nm and detecting sample emission at 528 nm using a Synergy H4 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

4.6. Growth assays

Cell number was determined as described (Sottile et al., 1998). Briefly, 48-well tissue culture plates were coated with saturating concentrations of collagen (150 nM in 0.02 N acetic acid), GST/vitronectin (64 nM), GST/vitronectinΔH (64 nM), GST/VNCBD (200 nM), or gelatin (64 nM), in PBS overnight at 4°C. Wells were coated with fibrinogen (64 nM in PBS) at 37°C for 2 h. For co-substrate experiments, wells were co-coated with collagen (3 nM in PBS) and GST/vitronectin (64 nM in PBS) overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed with PBS and cells were seeded in AimV/Cellgro at 2.6 × 103 cells/cm2. Cells were allowed to adhere for 4 h prior to the addition of protein. Cells were incubated for 4 days, then fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. Crystal violet was solubilized with 1% SDS and the absorbance at 590 nm was determined (Sottile et al., 1998). The absorbance obtained on protein-coated wells in the absence of cells (A540 = 0.07–0.09) was subtracted from all data points.

4.7. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)

Cell-based ELISAs were performed as described (Vial and McKeown-Longo, 2008). Briefly, 48-well plates were coated with collagen or vitronectin, as described above. FN-null MEFs were seeded at 1.4 × 105 cells/cm2, allowed to adhere for 4 h, and then treated with fibronectin at indicated concentrations. After a 20 h incubation, 9EG7 mAb (1 µg per 1×106 cells) was added to wells for an additional 1 h. Cells were then washed with PBS, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and incubated with anti-rat HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Antibodies were detected with o-phenylenediamine (0.4 mg/mL in 50 mM citrate-phosphate buffer, pH 5 with 0.4 µl/mL 30% H2O2). Absorbance values at 450 nm were obtained using a spectrophotometer. Measurements were corrected for light scattering by subtracting the absorbance values obtained at 630 nm.

4.8. Statistical analyses

Data are presented as either mean values ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) or fold increase ± SEM over vehicle controls. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate (growth assays, ELISAs, and fibronectin fluorimetry) or duplicate (DOC extractions and immunofluorescence microscopy) a minimum of 3 times. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism, Version 4 (LaJolla, CA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s post-test or Student’s t-test was used to determine significance. Results were considered significant if P values were less than 0.05.

Highlights.

We ask how adhesive substrate affects the functional response to fibronectin.

Fibronectin is less effective at enhancing growth of vitronectin-adherent cells.

The cell-binding domain of vitronectin mediates the reduced functional response.

Vitronectin adhesion allows α5β1 integrins to function in a low affinity state.

Fibronectin fibrils of vitronectin-adherent cells are less extended.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants GM081513 and EB008368 from the National Institutes of Health. CG was a trainee in the Medical Scientist Training Program (NIH T32 GM07356) and was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the NIH (F30 HL095299). The authors acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Katherine Wojciechowski and Susan J. Wilke-Mounts.

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FNIII

fibronectin type III repeat

- αSMA

alpha smooth muscle actin

- FN-null MEFs

fibronectin-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- DOC

deoxycholate

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adair BD, Xiong JP, Maddock C, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA, Yeager M. Three-dimensional EM structure of the ectodomain of integrin {alpha}V{beta}3 in a complex with fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:1109–1118. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askari JA, Buckley PA, Mould AP, Humphries MJ. Linking integrin conformation to function. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:165–170. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askari JA, Tynan CJ, Webb SE, Martin-Fernandez ML, Ballestrem C, Humphries MJ. Focal adhesions are sites of integrin extension. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:891–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae E, Sakai T, Mosher DF. Assembly of exogenous fibronectin by fibronectin-null cells is dependent on the adhesive substrate. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35749–35759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baneyx G, Baugh L, Vogel V. Coexisting conformations of fibronectin in cell culture imaged using fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14464–14468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251422998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoni G, Shih DT, Buck CA, Hemler ME. Monoclonal antibody 9EG7 defines a novel beta 1 integrin epitope induced by soluble ligand and manganese, but inhibited by calcium. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25570–25577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beacham DA, Cukierman E. Stromagenesis: the changing face of fibroblastic microenvironments during tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brien TP, Reddy PP, Vincent PA, Lewis EP, Ross JS, Saba TM. Lung matrix deposition of normal and alkylated plasma fibronectin: response to postsurgical sepsis. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L432–L443. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.3.L432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernousov MA, Fogerty FJ, Koteliansky VE, Mosher DF. Role of the I-9 and III-1 modules of fibronectin in formation of an extracellular fibronectin matrix. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10851–10858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodelli P, Urbinati C, Mitola S, Tanghetti E, Rusnati M. Sialic acid associated with alphavbeta3 integrin mediates HIV-1 Tat protein interaction and endothelial cell proangiogenic activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20456–20466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.337139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher RA, Kowalczyk AP, McKeown-Longo PJ. Localization of fibronectin matrix assembly sites on fibroblasts and endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:569–581. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clause KC, Barker TH. Extracellular matrix signaling in morphogenesis and repair. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:830–833. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlback K, Lofberg H, Dahlback B. Localization of vitronectin (S-protein of complement) in normal human skin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE. Affinity of integrins for damaged extracellular matrix: alpha v beta 3 binds to denatured collagen type I through RGD sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;182:1025–1031. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91834-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Bayless KJ, Davis MJ, Meininger GA. Regulation of tissue injury responses by the exposure of matricryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1489–1498. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65020-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufourcq P, Louis H, Moreau C, Daret D, Boisseau MR, Lamaziere JM, Bonnet J. Vitronectin expression and interaction with receptors in smooth muscle cells from human atheromatous plaque. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:168–176. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faurobert E, Rome C, Lisowska J, Manet-Dupe S, Boulday G, Malbouyres M, Balland M, Bouin AP, Keramidas M, Bouvard D, Coll JL, Ruggiero F, Tournier-Lasserve E, Albiges-Rizo C. CCM1-ICAP-1 complex controls beta1 integrin-dependent endothelial contractility and fibronectin remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:545–561. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201303044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felding-Habermann B, Ruggeri ZM, Cheresh DA. Distinct biological consequences of integrin alpha v beta 3-mediated melanoma cell adhesion to fibrinogen and its plasmic fragments. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5070–5077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui L, Wojciechowski K, Gildner CD, Nedelkovska H, Hocking DC. Identification of the heparin-binding determinants within fibronectin repeat III1: role in cell spreading and growth. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34816–34825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman EG, Pierschbacher MD, Ohgren Y, Ruoslahti E. Serum spreading factor (vitronectin) is present at the cell surface and in tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4003–4007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.13.4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Chang CH. Fibronectin matrix polymerization regulates small airway epithelial cell migration. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L169–L179. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00371.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Kowalski K. A cryptic fragment from fibronectin's III1 module localizes to lipid rafts and stimulates cell growth and contractility. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:175–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Sottile J, Langenbach KJ. Stimulation of integrin-mediated cell contractility by fibronectin polymerization. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10673–10682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Sottile J, Reho T, Fassler R, McKeown-Longo PJ. Inhibition of fibronectin matrix assembly by the heparin-binding domain of vitronectin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27257–27264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Titus PA, Sumagin R, Sarelius IH. Extracellular matrix fibronectin mechanically couples skeletal muscle contraction with local vasodilation. Circ Res. 2008;102:372–379. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science. 2009;326:1216–1219. doi: 10.1126/science.1176009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, Zhu Z, Hicklin D, Wu Y, Port JL, Altorki N, Port ER, Ruggero D, Shmelkov SV, Jensen KK, Rafii S, Lyden D. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri Y, Brew SA, Ingham KC. All six modules of the gelatin-binding domain of fibronectin are required for full affinity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11897–11902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman HK, Philp D, Hoffman MP. Role of the extracellular matrix in morphogenesis. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14:526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Moshfegh C, Lin Z, Albuschies J, Vogel V. Mesenchymal stem cells exploit extracellular matrix as mechanotransducer. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2425. doi: 10.1038/srep02425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvinovich SV, Novokhatny VV, Brew SA, Ingham KC. Reversible unfolding of an isolated heparin and DNA binding fragment, the first type III module from fibronectin. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1992;1119:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loridon-Rosa B, Vielh P, Cuadrado C, Burtin P. Comparative distribution of fibronectin and vitronectin in human breast and colon carcinomas. An immunofluorescence study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;90:7–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/90.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkiewicz C, Vijay-Kumar S, McLane MA, Niewiarowski S. Significance of RGD loop and C-terminal domain of echistatin for recognition of alphaIIb beta3 and alpha(v) beta3 integrins and expression of ligand-induced binding site. Blood. 1997;90:1565–1575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown-Longo PJ, Mosher DF. Binding of plasma fibronectin to cell layers of human skin fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:466–472. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercurius KO, Morla AO. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell growth by inhibition of fibronectin matrix assembly. Circ Res. 1998;82:548–556. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.5.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miekka SI, Ingham KC, Menache D. Rapid methods for isolation of human plasma fibronectin. Thromb Res. 1982;27:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(82)90272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morla A, Zhang Z, Ruoslahti E. Superfibronectin is a functionally distinct form of fibronectin. Nature. 1994;367:193–196. doi: 10.1038/367193a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher DF. Physiology of fibronectin. Annu Rev Med. 1984;35:561–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.35.020184.003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CM, Bissell MJ. Of extracellular matrix, scaffolds, and signaling: tissue architecture regulates development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:287–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi T, Kiehart DP, Erickson HP. Dynamics and elasticity of the fibronectin matrix in living cell culture visualized by fibronectin-green fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2153–2158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura Y, Kamikubo Y, Curriden SA, Wang J, Kiwada T, Futaki S, Kitagawa K, Loskutoff DJ. Kinetic analysis of the interaction between vitronectin and the urokinase receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9395–9404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankov R, Cukierman E, Katz BZ, Matsumoto K, Lin DC, Lin S, Hahn C, Yamada KM. Integrin dynamics and matrix assembly: tensin-dependent translocation of alpha(5)beta(1) integrins promotes early fibronectin fibrillogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1075–1090. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preissner KT. Structure and biological role of vitronectin. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1991;7:275–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.001423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebres RA, McKeown-Longo PJ, Vincent PA, Cho E, Saba TM. Extracellular matrix incorporation of normal and NEM-alkylated fibronectin: liver and spleen deposition. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G902–G912. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.6.G902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JT, Nash JR. Vitronectin (serum spreading factor): its localisation in normal and fibrotic tissue. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:1269–1272. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.12.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy DC, Hocking DC. Recombinant fibronectin matrix mimetics specify integrin adhesion and extracellular matrix assembly. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;19:558–570. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy DC, Wilke-Mounts SJ, Hocking DC. Chimeric fibronectin matrix mimetic as a functional growth- and migration-promoting adhesive substrate. Biomaterials. 2010;32:2077–2087. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechler JL, Schwarzbauer JE. Control of cell cycle progression by fibronectin matrix architecture. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25533–25536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffert D, Ciambrone G, Wagner NV, Binder BR, Loskutoff DJ. The somatomedin B domain of vitronectin. Structural requirements for the binding and stabilization of active type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2659–2666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla CA, Dalecki D, Hocking DC. Regional fibronectin and collagen fibril co-assembly directs cell proliferation and microtissue morphology. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer II, Scott S, Kawka DW, Kazazis DM, Gailit J, Ruoslahti E. Cell surface distribution of fibronectin and vitronectin receptors depends on substrate composition and extracellular matrix accumulation. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:2171–2182. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.6.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B, Janardhan KS, Kanthan R. Expression of angiostatin, integrin alphavbeta3, and vitronectin in human lungs in sepsis. Exp Lung Res. 2005;31:771–782. doi: 10.1080/01902140500324901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Carraher C, Schwarzbauer JE. Assembly of Fibronectin Extracellular Matrix. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:397–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers CE, Mosher DF. Protein kinase C modulation of fibronectin matrix assembly. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22277–22280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottile J, Hocking DC, Langenbach KJ. Fibronectin polymerization stimulates cell growth by RGD-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 23):4287–4299. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.23.4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottile J, Hocking DC, Swiatek PJ. Fibronectin matrix assembly enhances adhesion-dependent cell growth. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 19):2933–2943. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottile J, Shi F, Rublyevska I, Chiang HY, Lust J, Chandler J. Fibronectin-dependent collagen I deposition modulates the cell response to fibronectin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1934–C1946. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00130.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenman S, Vaheri A. Distribution of a major connective tissue protein, fibronectin, in normal human tissues. J Exp Med. 1978;147:1054–1064. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.4.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenman S, von Smitten K, Vaheri A. Fibronectin and atherosclerosis. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1980;642:165–170. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1980.tb10949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro S, Shattil SJ, Eto K, Tai V, Liddington RC, de Pereda JM, Ginsberg MH, Calderwood DA. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science. 2003;302:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini BR, Mosher DF. Vitronectin. Prog Hemost Thromb. 1991;10:269–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakonakis I, Staunton D, Ellis IR, Sarkies P, Flanagan A, Schor AM, Schor SL, Campbell ID. Motogenic sites in human fibronectin are masked by long range interactions. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15668–15675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakonakis I, Staunton D, Rooney LM, Campbell ID. Interdomain association in fibronectin: insight into cryptic sites and fibrillogenesis. Embo J. 2007;26:2575–2583. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vial D, McKeown-Longo PJ. PAI1 stimulates assembly of the fibronectin matrix in osteosarcoma cells through crosstalk between the alphavbeta5 and alpha5beta1 integrins. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1661–1670. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vial D, Monaghan-Benson E, McKeown-Longo PJ. Coordinate regulation of fibronectin matrix assembly by the plasminogen activator system and vitronectin in human osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2006;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EC, Janmey PA, Ferry JD, Mosher DF. Conformational states of fibronectin. Effects of pH, ionic strength, and collagen binding. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14973–14978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski K, Chang CH, Hocking DC. Expression, production, and characterization of full-length vitronectin in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;36:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Bae E, Zhang Q, Annis DS, Erickson HP, Mosher DF. Display of cell surface sites for fibronectin assembly is modulated by cell adherence to (1)F3 and C-terminal modules of fibronectin. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Peyruchaud O, French KJ, Magnusson MK, Mosher DF. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates fibronectin matrix assembly through a Rho-dependent signal pathway. Blood. 1999a;93:2984–2990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Sakai T, Nowlen J, Hayashi I, Fassler R, Mosher DF. Functional beta1-integrins release the suppression of fibronectin matrix assembly by vitronectin. J Biol Chem. 1999b;274:368–375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Brown J, Shaub A, Belkin AM, Burridge K. Rho-mediated contractility exposes a cryptic site in fibronectin and induces fibronectin matrix assembly. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:539–551. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]