Abstract

Enhanced gap junctional communication (GJC) between neurons is considered a major factor underlying the neuronal synchrony driving seizure activity. In addition, the hippocampal sharp wave ripple complexes, associated with learning and seizures, are diminished by GJC blocking agents. Although gap junctional blocking drugs inhibit experimental seizures, they all have other non-specific actions. Besides interneuronal GJC between dendrites, inter-axonal and inter-glial GJC is also considered important for seizure generation. Interestingly, in most studies of cerebral tissue from animal seizure models and from human patients with epilepsy, there is up-regulation of glial, but not neuronal gap junctional mRNA and protein. Significant changes in the expression and post-translational modification of the astrocytic connexin Cx43, and Panx1 were observed in an in vitro Co++ seizure model, further supporting a role for glia in seizure-genesis, although the reasons for this remain unclear. Further suggesting an involvement of astrocytic GJC in epilepsy, is the fact that the expression of astrocytic Cx mRNAs (Cxs 30 and 43) is several fold higher than that of neuronal Cx mRNAs (Cxs 36 and 45), and the number of glial cells outnumber neuronal cells in mammalian hippocampal and cortical tissue. Pannexin expression is also increased in both animal and human epileptic tissues. Specific Cx43 mimetic peptides, Gap 27 and SLS, inhibit the docking of astrocytic connexin Cx43 proteins from forming intercellular gap junctions (GJs), diminishing spontaneous seizures. Besides GJs, Cx membrane hemichannels in glia and Panx membrane channels in neurons and glia are also inhibited by traditional gap junctional pharmacological blockers. Although there is no doubt that connexin-based GJs and hemichannels, and pannexin-based membrane channels are related to epilepsy, the specific details of how they are involved and how we can modulate their function for therapeutic purposes remain to be elucidated.

Keywords: gap junctions, connexins, pannexins, epilepsy, neurons, glia, animal models, human cerebral tissue

Introduction

When one thinks of the “connections” between epilepsy and gap junctions (GJs), the usual interpretation is that the GJs form direct intercellular cytoplasmic connections between neurons, promoting the hypersynchronous neuronal activity associated with seizures. However, as this review discusses, that concept is rather naïve and greatly complicated by much new data concerning the potential roles of gap junctional communication (GJC) and membrane Cx hemichannels and pannexin channels. (Giaume et al., 2013). Although there are many other relevant reviews of GJs and epilepsy (Dudek et al., 1998; Carlen et al., 2000; Perez Velazquez and Carlen, 2000; Traub et al., 2004; Nemani and Binder, 2005; Salameh and Dhein, 2005; Jin and Chen, 2011; Carlen, 2012; Steinhauser et al., 2012), the roles of pannexins and Cx hemichannels are mainly ignored.

Strategic locations of electrotonic communication and seizure activity

It is commonly assumed that the key location for GJC and seizure generation is between neurons, usually between dendrites (Vazquez et al., 2009). For example our group demonstrated GJC between stratum oriens interneurons in the more electrotonically remote distal dendrites based on the relatively low coupling coefficients and the available anatomical evidence (Zhang et al., 2004). However, other locations for GJC critical for seizure generation have now been proposed. Using a double knockout (dKO) of the glial connexins 30 and 43 (Wallraff et al., 2006; Rouach et al., 2008) demonstrated that GJC between astrocytes for the delivery of glucose or lactate to astrocytes was necessary to sustain excitatory synaptic transmission and epileptiform activity. GJC also can spread apoptotic signals (Lin et al., 1998; Andrade-Rozental et al., 2000), a process which could be quite relevant in severe seizure activity (Belousov and Fontes, 2013).

An in vivo and ex-vivo study of adult rats treated with 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), a K+ channel blocker which induces seizures, have shown that dephosphorylation of connexin 43 associated with astrocytic swelling, resulted in reduction of astrocytic gap junction permeability (Zador et al., 2008). These results suggest that, during acute seizures, a prolonged inhibition of intercellular coupling develops in the astrocytic network. Long-lasting (weeks) astrocyte swelling was observed following seizures in the kindling seizure model (Khurgel and Ivy, 1996). It is well-known that glial swelling decreases the cerebral extracellular space (Dietzel and Heinemann, 1986; Sykova, 2004; Badaut et al., 2011). This enhances ephaptic transmission which promotes seizure activity (Jefferys, 1995; Dudek et al., 1998; Shahar et al., 2009). Since astrocytes play an important functional role in extracellular K+ and pH homeostasis, pathological brain states that result in K+ and pH dysregulation may also cause astrocyte swelling (Florence et al., 2012). The presence of gliotic scars in chronic focal epilepsy patients has led to the suggestion that glia can play an important pathophysiological role in chronic epilepsy (De Lanerolle et al., 2010). The astrocytes in sclerotic hippocampi differ from those in non-sclerotic hippocampi in their membrane physiology and related microvasculature (De Lanerolle et al., 2010). In addition, within these sclerotic hippocampal tissues, there is increased expression of many molecules normally associated with immune and inflammatory functions.

Traub and colleagues have introduced the concept of inter-axonal GJC playing a significant role in seizure-genesis and in the generation of sharp wave ripple complexes (Traub et al., 2002, 2005; Simon et al., 2013). Another underexplored feature of GJC in the CNS is the role of combined electrochemical synapses (Pereda, 2014) well-established in the invertebrate CNS, and recently demonstrated in mossy fiber terminals of the hippocampus by several groups (Hamzei-Sichani et al., 2007; Nagy, 2012; Vivar et al., 2012). What role these synapses play in epilepsy is presently unknown.

Gap junctions, sharp wave-ripple complexes and seizures

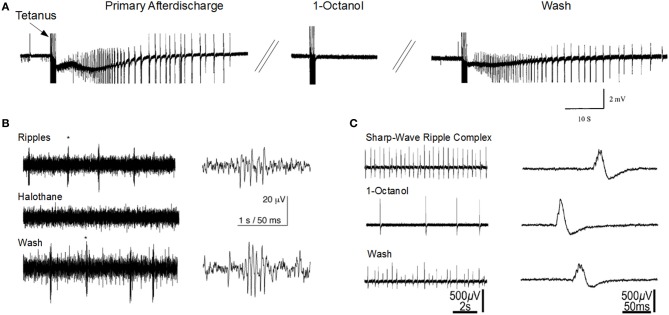

The sharp-wave ripple complex (SPW-ripple) (Figures 1B,C) is highly synchronous physiological activity that is generated in the hippocampus. Emerging evidence suggests that under pathological conditions the neuronal assemblies generating SPW-ripples may also be responsible for generating epileptiform activity (Staba et al., 2004; Khosravani et al., 2005; Behrens et al., 2007; Bragin et al., 2007; Beenhakker and Huguenard, 2009; Liotta et al., 2011; Simeone et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Gap junction blockers inhibit seizure-like activity and sharp-wave ripple activity in the CA1 hippocampal slice. (A) 1-Octanol abolishes primary afterdischarge induced after repeated tetanic stimulation for 2 s at 100 Hz (Modified with permission from Jahromi et al., 2002). (B) Halothane abolishes high-frequency ripple oscillations that are independent of sharp-wave activity (Modified with permission from Draguhn et al., 1998). (C) 1-Octanol reduces sharp-wave ripple activity (Modified with permission from Maier et al., 2003). Asterisks (*) indicate the ripples corresponding to the right traces.

The mechanisms responsible for ripple generation are not fully understood, however a prominent theory suggests that gap junction proteins play a critical role (Figures 1B,C). Traub and colleagues modeled hippocampal ripple activity through axo-axonal electronic coupling of pyramidal neurons (Traub et al., 2002). According to this model, spontaneously generated action potentials in CA1 axons depolarize electronically coupled neurons, resulting in a wave of spike generation that travels along the axonal plexus, and is detected in the LFP as a high frequency oscillation (Traub et al., 1999; Simon et al., 2014). The first experimental evidence implicating a role for GJs in high-frequency ripple oscillations in the hippocampus, came from utilizing multisite single unit recordings in the awake rat (Ylinen et al., 1995). They inhibited ripple oscillations in the CA1 by application of the anesthetic drug halothane, which, along with other effects, also blocks GJs. Subsequently, ripple oscillations were observed in extracellular field recordings in rat hippocampal brain slice preparations (Draguhn et al., 1998; Traub et al., 2002). The ripple oscillations were enhanced following bath application of a calcium-free solution, which enhances GJC and membrane excitability (Perez-Velazquez et al., 1994). Similar to ripples recorded in vivo, their occurrence was completely inhibited by pharmacological agents known to block GJs, such as octanol, carbenoxolone, halothane, and low pH.

However, as noted below, gap junction modulators are non-specific, and may mediate their effects through gap junctional-independent mechanisms (Nakahiro et al., 1991; Rouach et al., 2003). Recently, (Behrens et al., 2011) utilized a more specific gap junction blocker, mefloquine, which blocks Cx36, Cx43, and Cx50, and observed no effect on SPW or associated ripples. In Cx36 knockout mice, in vivo ripple oscillations were unaltered in terms of power, frequency, or probability of occurrence (Buhl et al., 2003). In contrast, in vitro studies on Cx36 knockout mice, demonstrated a reduced frequency of SPW and associated ripples (Pais et al., 2003). However, other in vitro studies in Cx36 knockout mice have reported no significant differences in ripple oscillations when chemical synaptic transmission was absent (Hormuzdi et al., 2001) or during application of the glutamate receptor agonist, kainate (Pais et al., 2003). It has to be recognized also that upregulation of other Cxs could significantly alter/blunt the effects of eliminating Cx36. Future studies should investigate the possibility that alternative connexins, connexin hemichannels, or pannexins are involved in the generation of SPW and ripple rythmogenesis.

Cx hemichannel and PanX channel involvement in seizure activity

GJ channels provide the basis for direct cell-to-cell communication, whereas Cx hemichannels and Panx channels allow the exchange of ions and signaling molecules such as ATP, NAD+, glutamate and other molecules less than 1000 Daltons between the cytoplasm and the extracellular milieu (Willecke et al., 2002). Recent papers have discussed the different properties of Cx hemichannels and Panx channels from the perspective of ATP release (Lohman and Isakson, 2014) and electrophysiological characteristics (Patel et al., 2014). These hemichannels and channels support autocrine and paracrine communication through a process called “gliotransmission,” which involves the uptake and release of metabolites such as glucose and glutathione and also the release of autocrine/paracrine molecules such as ATP, glutamate, NADP+ and adenosine into the extracellular medium (Sohl and Willecke, 2004; Bruzzone et al., 2005; Cherian et al., 2005; Retamal et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2008; Stridh et al., 2008). Studies have shown that the opening of Cx43 hemichannels is promoted by positive transmembrane voltages and reduced concentrations of extracellular divalent cations such as Ca2+. High intracellular H+, and phosphorylation of Cx43 promotes the closure of the hemichannels (Chang et al., 1996; Bennett et al., 2003; Saez et al., 2005; Verselis and Srinivas, 2008). The release of ATP and glutamate from astrocytic Cx hemichannels induces neuronal death through activation of Panx1 hemichannels (Orellana et al., 2011), a process which may contribute to the increased apoptosis observed in epileptic tissue. Furthermore, astrocytes release ATP in response to raised intracellular Ca2+, which subsequently is broken down to adenosine. Adenosine, a neuromodulator, can inhibit presynaptic neurotransmitter release via the activation of P2X receptors (Pascual et al., 2005; Montana et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007; Pankratov et al., 2009).

Effects of GJ channel blockers on seizure activity

The strongest evidence linking GJs and seizures is the seizure-blocking actions of agents that disrupt connexon-based GJ intercellular communication in in vitro and in vivo epilepsy models (e.g., Figure 1A). Although there are several GJC blockers available which possess anticonvulsive actions, they are not specific and do not usually discriminate between Cx isoforms or cell types (Perez-Velazquez et al., 1994; Ross et al., 2000; Kohling et al., 2001; Rozental et al., 2001; Jahromi et al., 2002; Steinhauser and Seifert, 2002; Szente et al., 2002; Gajda et al., 2003; Samoilova et al., 2003; Bostanci et al., 2006; Gigout et al., 2006; Nilsen et al., 2006; Bostanci and Bagirici, 2007; Medina-Ceja et al., 2008; Giaume and Theis, 2010). Carbenoxolone is one of the drugs widely used a GJ blocker, although one report showed a proconvulsive effect (Voss et al., 2009). Intracellular alkalinization, such as caused by trimethylamine and ammonium chloride, increases GJC, and also enhances epileptiform activity (Perez-Velazquez et al., 1994; Kohling et al., 2001). An antimalarial drug, quinine strongly blocks neuronal GJCs formed by Cx36 and to a lesser degree, Cx45 (Srinivas et al., 2001), but paradoxically enhances in vitro neocortical seizure activity caused by low magnesium perfusion, possible by blocking inhibitory interneuronal synchrony (Voss et al., 2009). Compounds of the fenamates family have also been reported to inhibit GJs composed of Cx43 with the following order of efficacy; meclofenamic acid > niflumic acid > flufenamic acid (Harks et al., 2001). Flufenamic acid was also shown to inhibit GJs composed of Cx26 and Cx32, but the selectivity was reported to be low (Srinivas and Spray, 2003). Most of the gap junctional blockers were also shown to affect Cx hemichannels and Panx channels (Giaume and Theis, 2010). Gap junctional blocking agents also affect the conductance of Panx membrane channels (Thompson and Macvicar, 2008; Giaume et al., 2013). Compared to Cx channels, Panx1 channels and Cx hemichannels are even more sensitive to most GJ channel blockers including carbenoxolone (CBX), flufenamic acid, mefloquin (MFQ) (Bruzzone et al., 2005; Iglesias et al., 2008) and Cx mimetic peptides (Dahl, 2007).

Several of the compounds from the fenemate family of blockers block Panx1 hemichannels in the following order: mefloquine > carbenoxolone > flufenamic acid (Iglesias et al., 2009). Studies have also shown that Panx1 hemichannels are 1000- to 10,000-fold more sensitive to mefloquine than Cx43 GJCs (Cruikshank et al., 2004; Iglesias et al., 2008). Although substances such as gadolinium (Gd3+) and lanthanum (La3+) block hemichannels without inhibiting gap junction or Panx1 channels, these ions are not specific to GJ proteins since they also block other channels such as Ca2+ channels (Mlinar and Enyeart, 1993; Liu et al., 2008). Long-chain alcohols are known to block Cx hemichannels but have only a very small effect on Panx channels. In contrast, low concentrations (5–10 μ M) of carbenoxolone block Panx1 channels and only have a minor inhibitory effect on Cx hemichannels (Schalper et al., 2008).

Effect of mimetic peptides on seizure activity

Connexin mimetic peptides, which correspond to the extracellular loops of connexins, are a class of specific and reversible inhibitors of GJC (Evans and Boitano, 2001; Herve and Dhein, 2010). In rat organotypic cultures, which show spontaneous epileptiform activity, prolonged (>10 h) application of Cx43 mimetic peptides, reduced the spontaneous seizure activity (Samoilova et al., 2008). This long period of incubation was required presumably to block the docking of homologous Cx43 hemichannels, a process which forms GJs, thereby diminishing inter-astrocytic GJC. These data suggest that enhanced inter-astrocytic gap junctional based coupling promotes seizure activity. Under normal physiological conditions, the probability of hemichannels opening is low because of the blocking effects of divalent extracellular ions such as magnesium and calcium (Ebihara, 2003; Ebihara et al., 2003). But when extracellular magnesium and/or calcium levels are reduced, for example, in the case of low Mg2+ or low Ca2+ seizure models, or the reduced extracellular Ca2+, which is seen during seizures in several seizure models (Lux and Heinemann, 1978; Somjen, 2002) the role of hemichannels and the effects of mimetic peptides must also be considered. In this case, higher concentrations of mimetic peptides are presumed to be required in order to block both GJ channels as well as hemichannels (Ebihara, 2003; Ebihara et al., 2003). In a slice culture model wherein added bicuculline caused epileptiform activity, low concentrations of a Cx43 mimetic peptide (amino acid sequence VDCFLSRPTEKT) targeting the extracellular loop two of Cx43, mainly blocked Cx43 hemichannels and prevented seizure-induced neuronal death (Yoon et al., 2010). Higher doses of the peptide, which inhibited GJs in addition to the hemichannels, increased the severity of the seizure-induced lesion. These data suggest that in this model, the neuronal damage from epileptiform neuronal hyperactivity is prevented by Cx43 gap junctional blockade and exacerbated by Cx43 hemichannel opening.

Gene expression, genetics, and the GJ proteome

Developmental age plays a role in gap junctional expression and seizure susceptibility. It is well-known that immature humans and animal models are more susceptible to undergoing seizures than mature adults (Rakhade and Jensen, 2009). Also expression of glial and neuronal connexins is developmentally regulated (Rozental et al., 2000; Montoro and Yuste, 2004). Within the developing neocortex, significant GJC was measured in four compartments (Sutor and Hagerty, 2005); (1) gap junction-coupled neuroblasts of the ventricular zone and GJs in migrating cells and radial glia, a compartment which disappears with maturity; (2) gap junction-coupled glial cells (astrocytes and oligodendrocytes); (3) gap junction-coupled pyramidal cells (which exists primarily during the first two post-natal weeks in rodents); and (4) gap junction-coupled inhibitory interneurons. It is hypothesized that the increased GJC between pyramidal cells plays a major role in lowering the seizure threshold in immature animals, but the roles played by the age-dependent differential expression of the various gap junctional and pannexin proteins remain unclear. Among the 21 known members of Cxs and three Panxs, it has been determined that there are at least 10 Cxs and 2 Panxs expressed in the brain (Willecke et al., 2002; Baranova et al., 2004). Their expression patterns are not uniform and the distribution of different gap junction subtypes is dependent upon location and developmental maturity (Willecke et al., 2002; Baranova et al., 2004).

Analysis of the mRNA expressions of different Cxs and Panxs in the hippocampal tissues from 15 day mice, showed the highest expression of astrocytic Cxs 43 and 30, followed by Panxs, and the lowest expression was observed in the neuronal Cxs 36, 40, and 45, a few orders of magnitude lower than the pannexins and astrocytic connexons (Mylvaganam et al., 2010). Since the half-lives of most Cxs are short, between 1 and 5 h (Herve et al., 2007), changes in Cx expression can rapidly alter Cx levels in cells (Laird, 2010). Recent studies have demonstrated that several mechanisms are involved in the control of Cx expression. In addition, the GJ proteome which includes complex translational and post-translational mechanisms (e.g., phosphorylation) that can introduce changes in protein conformation, activity, charge, stability and localization, can alter downstream signaling pathways that may contribute to the pathophysiology of several neurological diseases (Laird, 2010; Gehi et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013). Recently, Cx43 phosphorylation and Panx1 glycosylation were shown to occur following in vitro Co2+-induced seizures (Mylvaganam et al., 2010). Although Panx regulation has not been explored to the level studied for Cxs, from the functional point of view, Panxs might also show in seizure models, compensatory, overlapping, or unique physiological roles compared to those of Cxs.

Altered expression in animal models of epilepsy

Studies have shown changes in the expression of GJ mRNAs and proteins or changes in the post-translational modification form of the Cx43 and Panx protein in epileptic animal models (Table 1). Seizure-induced alterations in the expression of astrocytic Cx43 and Cx30, oligodendrocytic Cx32, and neuronal Cx36 have been measured, although there are some contradictory or inconsistent results. These variations may be due to differences in species, age, animal models, and methods of seizure induction, incubation/treatment time points, duration of seizure activity, and the brain regions examined in each study (Jin and Chen, 2011; Steinhauser et al., 2012). In addition, formation and degradation of GJs play an essential role in regulating the level of intercellular communication. With reported half-lives of Cxs being 1–5 h in tissues, the regulation of gap junction assembly and turnover is likely to be critical in the control of GJC. It has also become increasingly clear that Cxs have profound effects on gene expression (Kardami et al., 2007) and the presence of a Cx subtype can also influence the channel formation of other Cx subtypes (Chang et al., 1996).

Table 1.

Connexin and pannexin expression changes associated with experimentally-induced seizures in different rodent models.

| Gene | Brain region | Seizure model and age | Expression change | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Protein | ||||

| Cx43 | Hippocampus | In vitro Co2+-induced seizure in mouse model PD (post-natal days) 15 | 2-fold Increase | Increased non-phosphorylated form | Mylvaganam et al., 2010 |

| Li+-pilocarpine induced SE model–PD 30–45 SD rats | Increased in CA1, CA3 and the dentate gyrus | Su and Tong, 2010 | |||

| Kainic acid (KA) model using PD 1–14 and adult wistar rats | Decreased in CA3-CA4 pyramidal layers and increased in other regions | Condorelli et al., 2003 | |||

| Slight decrease after 4 weeks | Same as mRNA | Sohl et al., 2000 | |||

| Bicuculline-Hippocampal organotypic slice cultures from PD 7 wistar rats | Increased | Increased | Samoilova et al., 2003 | ||

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced adult rat model | Decreased | Sayyah et al., 2012 | |||

| Amygdala and cerebral cortex | In vivo-tetanus toxin induced seizure model using adult rats | Decreased | Elisevich et al., 1998 | ||

| Primary focus and mirror focus | In-vivo 4-Amino pyridine(4-AP) model (4-AP) using PD 40–50 wistar rats | Increased | Increased | Szente et al., 2002 | |

| Neocortex and hippocampus | Mouse model of tuberous sclerosis complex using PD 14–35 Tsc1GFAPCKO mice | Decreased | Xu et al., 2009 | ||

| Cx30 | Cortex, thalamus and amygdaloid nucleus | Kainaic acid (KA)-induced epilepsy in P1, PD7 and 14, and adult wistar rats | Increased within 6 h and decreased after 12 and 24 h | Increased within 6 h | Condorelli et al., 2003 |

| Hippocampus | KA induced epilepsy in 7–8 weeks old SD rat model | Slightly reduced | Takahashi et al., 2010 | ||

| Unchanged | Sohl et al., 2000 | ||||

| Increased from 6 to 24 h in CA3-CA4 pyramidal layers | Decreased within 12–24 h | Condorelli et al., 2002 | |||

| Cx 32 | Hippocampus | Bicuculline—treated organotypic slice cultures using 7 days old Wistar rats | Increased | Increased | Li et al., 2001; Samoilova et al., 2003 |

| In vivo kindling model using adult rats | Decreased | No change | Sayyah et al., 2012 | ||

| Cx 36 | Amygdala | Adult Wistar Kindling rat model | Increased during focal seizures, then back to basal levels after onset of generalized seizures | Increased during focal seizures, then back to basal levels after onset of generalized seizures | Beheshti et al., 2010 |

| Hippocampus | Kindling model in PD 26–33 CD rats | Decreased | Decreased | Sohl et al., 2000 | |

| Panx1 | Hippocampus | Co++ mouse model using PD 15 mice | 1.5-fold Increase | Increased glycosylated ~48 kDa | Mylvaganam et al., 2010 |

| Decreased glycosylated ~46 kDa | |||||

| Increased native form ~43 kDa | |||||

| Panx2 | Hippocampus | Co++ mouse model using PD 15 mice | 1.4-fold Increase | No change | Mylvaganam et al., 2010 |

Among the many Cxs present in the brain, studies have reported alterations only in Cx30, 32, 36, and 43 (Table 1). Interestingly, recent studies using dKO mice (Magnotti et al., 2011) observed that animals lacking oligodendrocytic Cx32 and astrocytic Cx43 displayed seizures, motor impairment, and early mortality. Although myelin ultrastructure was not affected, abrupt formation of vacuolation in the white matter and loss of astrocytes was observed in these animals. These observations indicate an unexpected role for specific astrocytic/oligodendrocytic connexins in the survival of astrocytes. When compared to previous studies using Cx43-Cx30 dKO mice, the loss of astrocytic Cx43 and Cx30 (Lutz et al., 2009) was less deleterious than the loss of Cx43 and Cx32. This could mean that Cx32 and Cx43 together mediate signaling events that promote astrocyte survival. However, it is difficult to interpret these results without understanding the nature of the signals and mechanisms underlying the pathology of astrocytes in Cx32-Cx43 dKOs. The first report on seizure-associated Panx expression alterations in the mouse hippocampus, showed a 1.5 increase in Panx1 mRNA and a 1.4-fold increase in Panx2 mRNA (Mylvaganam et al., 2010). Also, a 2-fold increase in Cx43 mRNA and protein were observed in the same study. In addition, Panxs 1 and 2 and glial Cx mRNAs became highly correlated following the seizure activity. We suggested that this marked cross-correlation could be the basis of a transcriptomic network of coordinated gene expression, related to seizure induction or seizure activity (Mylvaganam et al., 2010). Here the highly correlated transcript abundance might also imply that the levels of expression are controlled relative to one another to provide proper functionality of the oligomeric proteins (Mylvaganam et al., 2010). The same study evaluated post-translational modifications and showed a significant increase in glycosylated Panx1 expression after seizures, leading to the notion that involvement of Panx1 hemichannels may contribute to seizures in this model (Mylvaganam et al., 2010). Previous studies have shown that the functional state and cellular distribution of mouse Panxs are regulated by their glycosylation status and interactions among Panx family members (Penuela et al., 2009). Glycosylation sites are located on the extracellular loop and high levels of glycosylated Panx proteins prevented interactions between pannexins (Boassa et al., 2007; Penuela et al., 2007), therefore supporting the formation of membrane channels. Unlike connexins, which are not glycosylated, Panx1 is glycosylated in the second extracellular loop (Boassa et al., 2007; Penuela et al., 2007). This modification adds considerable bulk to the extracellular domain of the protein. Insertion of glycosylation sites into the extracellular loop domains of connexins blocked formation of intercellular junctional channels upon glycosylation (Dahl et al., 1994). Panx1 channel properties are similar to Cx hemichannels. They are activated by depolarization, mechanical stress, raised extracellular potassium, and P2 receptor activation (Scemes et al., 2009; Santiago et al., 2011). Panxs mediate ATP release from astrocytes and neurons (Bao et al., 2004; Iglesias et al., 2008, 2009) suggesting that these channels may contribute to seizures by raising extracellular ATP and arachidonic acid (Thompson et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2009; Macvicar and Thompson, 2010). NMDA receptor activation opens Panx channels promoting epileptiform activity (Thompson et al., 2008). Blockade or deletion of Panx1 channels diminished ATP release and seizure activity. However, Kim and Kang showed that P2X7R-Panx1 complex may play an important role as a negative modulator of M1 receptor-mediated seizure activity in vivo, since they showed pilocarpine-induced seizures in mice were enhanced following administration of P2X7R antagonists or by gene silencing of P2X7R or Panx1 in WT in a process mediated by PKC via intracellular Ca2+ release (Kim and Kang, 2011).

Altered GJ expressions in human epilepsy

Gap junction expression studies in human epileptic tissue have demonstrated no change (Elisevich et al., 1997) or elevated (Naus et al., 1991; Collignon et al., 2006) levels of Cx mRNA and protein (Table 2). In addition, altered expression of several membrane channels, receptors, and transporters in astroglial membranes have been found in tissue from epileptic human brain. Although the significance of these alterations is poorly understood, modified astroglial functioning might have an important role in the generation and spread of seizure activity.

Table 2.

Gap junctional expression changes associated with human epilepsy.

| Gene | Epileptic condition | Brain region | Expression change | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Protein | ||||

| Cx32 | Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) | Neocortex | Increased | Naus et al., 1991; Jin and Chen, 2011 | |

| Hippocampus | Decreased | Collignon et al., 2006 | |||

| Cx36 | TLE | Hippocampus | Unchanged | ||

| Cx43 | Intractable seizure | Increased | Naus et al., 1991 | ||

| Complex partial seizure disorder | No significant change | Elisevich et al., 1997 | |||

| TLE | Hippocampus Cortex | Increased | Jin and Chen, 2011 | ||

| Epilepsy associated brain tumors | Perilesional Cortex | Low-grade gliomas showed Increased expression and different isoforms (like controls) but most high-grade gliomas had only one isoform (non-phosphorylated) | Aronica et al., 2001 | ||

| Generalized seizure in the progression of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy | Hippocampus | Increased | Fonseca et al., 2002 | ||

| Panx1 | TLE | Cortex | Increased | Jiang et al., 2013 | |

| Panx2 | No change | ||||

| Panx1+Panx2 | Only in layers II and III in the control but present in all layers in TLE patients | ||||

Whether these changes in gene expressions have any direct effect on seizure generation is unclear. These changes might be pro-epileptic responses contributing to the pathogenesis of the disease, or adaptive responses to cope with the pathologic condition. Confounding the interpretation of human data is the fact that epilepsy is not a single condition, but a large group of highly heterogeneous disorders, which have in common an abnormally increased predisposition to seizures (Fisher et al., 2005; Steinhauser et al., 2012). It is difficult to conduct proper GJ expression studies in humans, since tissues obtained from patients are usually at different stages of the condition and seizure duration. Furthermore, type of epilepsy, patient age, duration of seizure and antiepileptic treatment might also alter connexin expression. “Controls” used in most studies are from tumor or autopsy specimens. Hence apparent changes in connexin levels could be caused by altered expression in “control” tissues (Nemani and Binder, 2005). Also, changes in mRNA or protein levels do not necessarily translate into changes in functional coupling. Therefore, functional assays are required for the reliable investigation of the role of GJs in human epilepsy. Neurosurgical specimens from patients presenting with TLE are often accompanied by massive reactive gliosis (Hinterkeuser et al., 2000; De Lanerolle and Lee, 2005; Kim and Kang, 2011) and activated astrocytes (Hinterkeuser et al., 2000; Seifert et al., 2006). Also in human tissue and in animal models of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy there are alterations in expression, subcellular localization, and function of astroglial GJs which might impair K+ buffering and other homeostatic network functions (Heinemann et al., 2000; Kivi et al., 2000). Evidence also suggests that in TLE patients, changes in glia can alter the delivery of energetic substances to neurons and consequently lead to a short term functional alterations in neurons. Dysfunction of astrocytic K+ homeostasis and adenosine function has been shown to play a major role in epileptogenesis (Dityatev and Rusakov, 2011; Allen et al., 2012; Risher and Eroglu, 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Boison et al., 2013). In a recent study, quantitation of Panx1 and Panx2 expression in surgically removed human brain tissue of epileptic temporal lobes showed that Panx1 and Panx2 proteins were expressed in all layers of the epileptic cortex, but predominantly restricted to layers II and III of the control group (Jiang et al., 2013). Overall, Panx1 protein expression was significantly higher in the temporal lobe cortex of patients with TLE compared to controls. No significant differences were identified in Panx2 expression levels. This is the first study to show that Panx channels may also be involved in the pathogenesis of human epilepsy. These expression changes could be a cause or a response to the epileptic neuronal hyperactivity or an effect of chronic epileptic damage. Further studies are required.

Cx genetic mutations associated with epilepsy

At present, there are at least 10 distinct diseases known to be associated with gene mutations in connexins, some of which are associated with epilepsy. Connexin-linked diseases caused by gene mutations or altered connexin expression, protein assembly or localization, will ultimately impact the rest of the proteome, which can influence the manifestation of the pathology (Laird, 2010). In humans, the vast majority of epileptic cases are of idiopathic origin, thus a deeper understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms will lead to new insights into brain structure and function as well as improved therapies. Recent studies have indicated that Cx36 is a likely gene linked to Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME). A case control study performed on a sample of 29 JME patients with a mutationin15q14 loci, 140 randomly selected JME patients, and 123 controls, demonstrated a significant association between JME and Cx36 gene (Mas et al., 2004; Hempelmann et al., 2006).

Mutations of the tumor suppressor genes TSC1 and TSC2 are found in tuberous sclerosis, and epilepsy is one of its major manifestations. Deleting TSC1 in astrocytes caused seizures attributed to diminished astrocytic GJ intercellular communication and impaired potassium buffering (Xu et al., 2009). Patients with oculodentodigital dysplasia (ODDD), a rare genetic disease which is caused by mutations in the gene encoding Cx43, develop seizures in addition to other neurological symptoms (Loddenkemper et al., 2002). In cell culture, some of the ODDD-associated mutations of Cx43 cause loss of GJ coupling, but increased hemichannel activity (Dobrowolski et al., 2007).

Conclusions and questions

In brief, the roles of GJs, connexins, and pannexins in epilepsy remain unclear. The lack of specificity of pharmacological agents now used to block or enhance GJC is a challenge if one wants to understand the role of a particular type of connexin-based GJ, and if wants to develop a specific therapeutic tool. The fact that most of these agents affect the Cx hemichannels and the Panx membrane channels further confuses the interpretation of experimental data. The ongoing development of peptides targeting specific Cxs and Panxs will permit a more precise dissection of the functions of the different Cx and Panx species. Although the gap junctional blocking drugs are almost always anticonvulsant, there is not as of yet an anticonvulsant drug on the market that is reputed to have gap junctional blocking properties, although both acetazolamide and topiramate inhibit carbonic anhydrase activity which should cause an intracellular acidosis thereby blocking GJC. Another problem is the overwhelming evidence that tissue from animal models and human epileptics show increases in Cxs expression in glia but not in neurons. This begs the question as to what are the roles of glia in seizure generation. If applying a gap junctional blocking agent to epileptic tissue is blocking interglial GJC, then what is the underlying anticonvulsant mechanism? Or could these agents have their major anticonvulsant action by blocking the conductance of Cx hemichannels and/or Panx channels? The scientific community is just now starting to consider the possible role of these membrane channels in the pathophysiology of epilepsy. In summary, although there is no doubt that GJs, connexins and pannexins are intimately related to epilepsy and seizure generation, the specific details of exactly how they are involved and how we can modulate their function for therapeutic purposes remain to be elucidated.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Supported by CIHR and NSERC.

References

- Allen N. J., Bennett M. L., Foo L. C., Wang G. X., Chakraborty C., Smith S. J., et al. (2012). Astrocyte glypicans 4 and 6 promote formation of excitatory synapses via GluA1 AMPA receptors. Nature 486, 410–414 10.1038/nature11059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade-Rozental A. F., Rozental R., Hopperstad M. G., Wu J. K., Vrionis F. D., Spray D. C. (2000). Gap junctions: the “kiss of death” and the “kiss of life.” Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 32, 308–315 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00099-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica E., Gorter J. A., Jansen G. H., Leenstra S., Yankaya B., Troost D. (2001). Expression of connexin 43 and connexin 32 gap-junction proteins in epilepsy-associated brain tumors and in the perilesional epileptic cortex. Acta Neuropathol. 101, 449–459 10.1007/s004010000305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badaut J., Ashwal S., Adami A., Tone B., Recker R., Spagnoli D., et al. (2011). Brain water mobility decreases after astrocytic aquaporin-4 inhibition using RNA interference. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 819–831 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L., Locovei S., Dahl G. (2004). Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP. FEBS Lett. 572, 65–68 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranova A., Ivanov D., Petrash N., Pestova A., Skoblov M., Kelmanson I., et al. (2004). The mammalian pannexin family is homologous to the invertebrate innexin gap junction proteins. Genomics 83, 706–716 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenhakker M. P., Huguenard J. R. (2009). Neurons that fire together also conspire together: is normal sleep circuitry hijacked to generate epilepsy? Neuron 62, 612–632 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beheshti S., Sayyah M., Golkar M., Sepehri H., Babaie J., Vaziri B. (2010). Changes in hippocampal connexin 36 mRNA and protein levels during epileptogenesis in the kindling model of epilepsy. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 34, 510–515 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens C. J., Ul Haq R., Liotta A., Anderson M. L., Heinemann U. (2011). Nonspecific effects of the gap junction blocker mefloquine on fast hippocampal network oscillations in the adult rat in vitro. Neuroscience 192, 11–19 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens C. J., Van Den Boom L. P., Heinemann U. (2007). Effects of the GABA(A) receptor antagonists bicuculline and gabazine on stimulus-induced sharp wave-ripple complexes in adult rat hippocampus in vitro. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 2170–2181 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05462.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belousov A. B., Fontes J. D. (2013). Neuronal gap junction coupling as the primary determinant of the extent of glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity. J. Neural Transm. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s00702-013-1109-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. V., Contreras J. E., Bukauskas F. F., Saez J. C. (2003). New roles for astrocytes: gap junction hemichannels have something to communicate. Trends Neurosci. 26, 610–617 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boassa D., Ambrosi C., Qiu F., Dahl G., Gaietta G., Sosinsky G. (2007). Pannexin1 channels contain a glycosylation site that targets the hexamer to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31733–31743 10.1074/jbc.M702422200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D., Sandau U. S., Ruskin D. N., Kawamura M., Jr., Masino S. A. (2013). Homeostatic control of brain function - new approaches to understand epileptogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7:109 10.3389/fncel.2013.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostanci M. O., Bagirici F. (2007). Anticonvulsive effects of carbenoxolone on penicillin-induced epileptiform activity: an in vivo study. Neuropharmacology 52, 362–367 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostanci M. O., Bagirici F., Canan S. (2006). A calcium channel blocker flunarizine attenuates the neurotoxic effects of iron. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 22, 119–125 10.1007/s10565-006-0037-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A., Wilson C. L., Engel J., Jr. (2007). Voltage depth profiles of high-frequency oscillations after kainic acid-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsia 48(Suppl. 5), 35–40 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R., Barbe M. T., Jakob N. J., Monyer H. (2005). Pharmacological properties of homomeric and heteromeric pannexin hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Neurochem. 92, 1033–1043 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02947.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl D. L., Harris K. D., Hormuzdi S. G., Monyer H., Buzsaki G. (2003). Selective impairment of hippocampal gamma oscillations in connexin-36 knock-out mouse in vivo. J. Neurosci. 23, 1013–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlen P. L. (2012). Curious and contradictory roles of glial connexins and pannexins in epilepsy. Brain Res. 1487, 54–60 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.06.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlen P. L., Skinner F., Zhang L., Naus C., Kushnir M., Perez Velazquez J. L. (2000). The role of gap junctions in seizures. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 32, 235–241 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00084-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M., Werner R., Dahl G. (1996). A role for an inhibitory connexin in testis? Dev. Biol. 175, 50–56 10.1006/dbio.1996.0094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen V. C., Gouw J. W., Naus C. C., Foster L. J. (2013). Connexin multi-site phosphorylation: mass spectrometry-based proteomics fills the gap. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1828, 23–34 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian P. P., Siller-Jackson A. J., Gu S., Wang X., Bonewald L. F., Sprague E., et al. (2005). Mechanical strain opens connexin 43 hemichannels in osteocytes: a novel mechanism for the release of prostaglandin. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3100–3106 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon F., Wetjen N. M., Cohen-Gadol A. A., Cascino G. D., Parisi J., Meyer F. B., et al. (2006). Altered expression of connexin subtypes in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in humans. J. Neurosurg. 105, 77–87 10.3171/jns.2006.105.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli D. F., Mudo G., Trovato-Salinaro A., Mirone M. B., Amato G., Belluardo N. (2002). Connexin-30 mRNA is up-regulated in astrocytes and expressed in apoptotic neuronal cells of rat brain following kainate-induced seizures. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 21, 94–113 10.1006/mcne.2002.1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli D. F., Trovato-Salinaro A., Mudo G., Mirone M. B., Belluardo N. (2003). Cellular expression of connexins in the rat brain: neuronal localization, effects of kainate-induced seizures and expression in apoptotic neuronal cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 1807–1827 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02910.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank S. J., Hopperstad M., Younger M., Connors B. W., Spray D. C., Srinivas M. (2004). Potent block of Cx36 and Cx50 gap junction channels by mefloquine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12364–12369 10.1073/pnas.0402044101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G. (2007). Gap junction-mimetic peptides do work, but in unexpected ways. Cell Commun. Adhes. 14, 259–264 10.1080/15419060801891018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G., Nonner W., Werner R. (1994). Attempts to define functional domains of gap junction proteins with synthetic peptides. Biophys. J. 67, 1816–1822 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80663-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lanerolle N. C., Lee T. S. (2005). New facets of the neuropathology and molecular profile of human temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 7, 190–203 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lanerolle N. C., Lee T. S., Spencer D. D. (2010). Astrocytes and epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics 7, 424–438 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel I., Heinemann U. (1986). Dynamic variations of the brain cell microenvironment in relation to neuronal hyperactivity. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 481, 72–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev A., Rusakov D. A. (2011). Molecular signals of plasticity at the tetrapartite synapse. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21, 353–359 10.1016/j.conb.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolski R., Sommershof A., Willecke K. (2007). Some oculodentodigital dysplasia-associated Cx43 mutations cause increased hemichannel activity in addition to deficient gap junction channels. J. Membr. Biol. 219, 9–17 10.1007/s00232-007-9055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draguhn A., Traub R. D., Schmitz D., Jefferys J. G. (1998). Electrical coupling underlies high-frequency oscillations in the hippocampus in vitro. Nature 394, 189–192 10.1038/28184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek F. E., Yasumura T., Rash J. E. (1998). “Non-synaptic” mechanisms in seizures and epileptogenesis. Cell Biol. Int. 22, 793–805 10.1006/cbir.1999.0397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara L. (2003). Physiology and biophysics of hemi-gap-junctional channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Acta Physiol. Scand. 179, 5–8 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara L., Liu X., Pal J. D. (2003). Effect of external magnesium and calcium on human connexin46 hemichannels. Biophys. J. 84, 277–286 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74848-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisevich K., Rempel S. A., Smith B., Hirst K. (1998). Temporal profile of connexin 43 mRNA expression in a tetanus toxin-induced seizure disorder. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 35, 23–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisevich K., Rempel S. A., Smith B. J., Edvardsen K. (1997). Hippocampal connexin 43 expression in human complex partial seizure disorder. Exp. Neurol. 145, 154–164 10.1006/exnr.1997.6467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans W. H., Boitano S. (2001). Connexin mimetic peptides: specific inhibitors of gap-junctional intercellular communication. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 29, 606–612 10.1042/BST0290606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R. S., Van Emde Boas W., Blume W., Elger C., Genton P., Lee P., et al. (2005). Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia 46, 470–472 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florence C. M., Baillie L. D., Mulligan S. J. (2012). Dynamic volume changes in astrocytes are an intrinsic phenomenon mediated by bicarbonate ion flux. PLoS ONE 7:e51124 10.1371/journal.pone.0051124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca C. G., Green C. R., Nicholson L. F. (2002). Upregulation in astrocytic connexin 43 gap junction levels may exacerbate generalized seizures in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 929, 105–116 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)03289-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajda Z., Gyengesi E., Hermesz E., Ali K. S., Szente M. (2003). Involvement of gap junctions in the manifestation and control of the duration of seizures in rats in vivo. Epilepsia 44, 1596–1600 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.25803.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehi R., Shao Q., Laird D. W. (2011). Pathways regulating the trafficking and turnover of pannexin1 protein and the role of the C-terminal domain. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27639–27653 10.1074/jbc.M111.260711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaume C., Leybaert L., Naus C. C., Saez J. C. (2013). Connexin and pannexin hemichannels in brain glial cells: properties, pharmacology, and roles. Front. Pharmacol. 4:88 10.3389/fphar.2013.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaume C., Theis M. (2010). Pharmacological and genetic approaches to study connexin-mediated channels in glial cells of the central nervous system. Brain Res. Rev. 63, 160–176 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigout S., Louvel J., Kawasaki H., D'antuono M., Armand V., Kurcewicz I., et al. (2006). Effects of gap junction blockers on human neocortical synchronization. Neurobiol. Dis. 22, 496–508 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzei-Sichani F., Kamasawa N., Janssen W. G., Yasumura T., Davidson K. G., Hof P. R., et al. (2007). Gap junctions on hippocampal mossy fiber axons demonstrated by thin-section electron microscopy and freeze fracture replica immunogold labeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12548–12553 10.1073/pnas.0705281104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harks E. G., De Roos A. D., Peters P. H., De Haan L. H., Brouwer A., Ypey D. L., et al. (2001). Fenamates: a novel class of reversible gap junction blockers. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298, 1033–1041 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U., Gabriel S., Jauch R., Schulze K., Kivi A., Eilers A., et al. (2000). Alterations of glial cell function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 41(Suppl. 6), S185–S189 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempelmann A., Heils A., Sander T. (2006). Confirmatory evidence for an association of the connexin-36 gene with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 71, 223–228 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herve J. C., Derangeon M., Bahbouhi B., Mesnil M., Sarrouilhe D. (2007). The connexin turnover, an important modulating factor of the level of cell-to-cell junctional communication: comparison with other integral membrane proteins. J. Membr. Biol. 217, 21–33 10.1007/s00232-007-9054-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herve J. C., Dhein S. (2010). Peptides targeting gap junctional structures. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 3056–3070 10.2174/138161210793292528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinterkeuser S., Schroder W., Hager G., Seifert G., Blumcke I., Elger C. E., et al. (2000). Astrocytes in the hippocampus of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy display changes in potassium conductances. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 2087–2096 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormuzdi S. G., Pais I., Lebeau F. E., Towers S. K., Rozov A., Buhl E. H., et al. (2001). Impaired electrical signaling disrupts gamma frequency oscillations in connexin 36-deficient mice. Neuron 31, 487–495 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00387-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias R., Locovei S., Roque A., Alberto A. P., Dahl G., Spray D. C., et al. (2008). P2X7 receptor-Pannexin1 complex: pharmacology and signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C752–C760 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias R., Spray D. C., Scemes E. (2009). Mefloquine blockade of Pannexin1 currents: resolution of a conflict. Cell Commun. Adhes. 16, 131–137 10.3109/15419061003642618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi S. S., Wentlandt K., Piran S., Carlen P. L. (2002). Anticonvulsant actions of gap junctional blockers in an in vitro seizure model. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 1893–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferys J. G. (1995). Nonsynaptic modulation of neuronal activity in the brain: electric currents and extracellular ions. Physiol. Rev. 75, 689–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Long H., Ma Y., Long L., Li Y., Li F., et al. (2013). Altered expression of pannexin proteins in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Mol. Med. Rep. 8, 1801–1806 10.3892/mmr.2013.1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M. M., Chen Z. (2011). Role of gap junctions in epilepsy. Neurosci. Bull. 27, 389–406 10.1007/s12264-011-1944-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardami E., Dang X., Iacobas D. A., Nickel B. E., Jeyaraman M., Srisakuldee W., et al. (2007). The role of connexins in controlling cell growth and gene expression. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 94, 245–264 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravani H., Pinnegar C. R., Mitchell J. R., Bardakjian B. L., Federico P., Carlen P. L. (2005). Increased high-frequency oscillations precede in vitro low-Mg seizures. Epilepsia 46, 1188–1197 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.65604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurgel M., Ivy G. O. (1996). Astrocytes in kindling: relevance to epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Res. 26, 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. E., Kang T. C. (2011). The P2X7 receptor-pannexin-1 complex decreases muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated seizure susceptibility in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2037–2047 10.1172/JCI44818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivi A., Lehmann T. N., Kovacs R., Eilers A., Jauch R., Meencke H. J., et al. (2000). Effects of barium on stimulus-induced rises of [K+]o in human epileptic non-sclerotic and sclerotic hippocampal area CA1. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 2039–2048 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohling R., Gladwell S. J., Bracci E., Vreugdenhil M., Jefferys J. G. (2001). Prolonged epileptiform bursting induced by 0-Mg(2+) in rat hippocampal slices depends on gap junctional coupling. Neuroscience 105, 579–587 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00222-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird D. W. (2010). The gap junction proteome and its relationship to disease. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 92–101 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Shen H., Naus C. C., Zhang L., Carlen P. L. (2001). Upregulation of gap junction connexin 32 with epileptiform activity in the isolated mouse hippocampus. Neuroscience 105, 589–598 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00204-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. H., Weigel H., Cotrina M. L., Liu S., Bueno E., Hansen A. J., et al. (1998). Gap-junction-mediated propagation and amplification of cell injury. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 494–500 10.1038/2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. T., Wang Y., Xue Y., Feng D. C., Xu Y., Xu L. Y. (2008). Tetrandrine suppresses LPS-induced astrocyte activation via modulating IKKs-IkappaBalpha-NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 315, 41–49 10.1007/s11010-008-9787-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta A., Caliskan G., Ul Haq R., Hollnagel J. O., Rosler A., Heinemann U., et al. (2011). Partial disinhibition is required for transition of stimulus-induced sharp wave-ripple complexes into recurrent epileptiform discharges in rat hippocampal slices. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 172–187 10.1152/jn.00186.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. T., Toychiev A. H., Takahashi N., Sabirov R. Z., Okada Y. (2008). Maxi-anion channel as a candidate pathway for osmosensitive ATP release from mouse astrocytes in primary culture. Cell Res. 18, 558–565 10.1038/cr.2008.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loddenkemper T., Grote K., Evers S., Oelerich M., Stogbauer F. (2002). Neurological manifestations of the oculodentodigital dysplasia syndrome. J. Neurol. 249, 584–595 10.1007/s004150200068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman A. W., Isakson B. E. (2014). Differentiating connexin hemichannels and pannexin channels in cellular ATP release. FEBS Lett. 588, 1379–1388 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz S. E., Zhao Y., Gulinello M., Lee S. C., Raine C. S., Brosnan C. F. (2009). Deletion of astrocyte connexins 43 and 30 leads to a dysmyelinating phenotype and hippocampal CA1 vacuolation. J. Neurosci. 29, 7743–7752 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0341-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lux H. D., Heinemann U. (1978). Ionic changes during experimentally induced seizure activity. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Suppl. 34, 289–297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macvicar B. A., Thompson R. J. (2010). Non-junction functions of pannexin-1 channels. Trends Neurosci. 33, 93–102 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnotti L. M., Goodenough D. A., Paul D. L. (2011). Deletion of oligodendrocyte Cx32 and astrocyte Cx43 causes white matter vacuolation, astrocyte loss and early mortality. Glia 59, 1064–1074 10.1002/glia.21179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier N., Nimmrich V., Draguhn A. (2003). Cellular and network mechanisms underlying spontaneous sharp wave-ripple complexes in mouse hippocampal slices. J. Physiol. 550, 873–887 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.044602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas C., Taske N., Deutsch S., Guipponi M., Thomas P., Covanis A., et al. (2004). Association of the connexin36 gene with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. J. Med. Genet. 41, e93 10.1136/jmg.2003.017954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Ceja L., Cordero-Romero A., Morales-Villagran A. (2008). Antiepileptic effect of carbenoxolone on seizures induced by 4-aminopyridine: a study in the rat hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Brain Res. 1187, 74–81 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlinar B., Enyeart J. J. (1993). Block of current through T-type calcium channels by trivalent metal cations and nickel in neural rat and human cells. J. Physiol. 469, 639–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montana V., Malarkey E. B., Verderio C., Matteoli M., Parpura V. (2006). Vesicular transmitter release from astrocytes. Glia 54, 700–715 10.1002/glia.20367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro R. J., Yuste R. (2004). Gap junctions in developing neocortex: a review. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 47, 216–226 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mylvaganam S., Zhang L., Wu C., Zhang Z. J., Samoilova M., Eubanks J., et al. (2010). Hippocampal seizures alter the expression of the pannexin and connexin transcriptome. J. Neurochem. 112, 92–102 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy J. I. (2012). Evidence for connexin36 localization at hippocampal mossy fiber terminals suggesting mixed chemical/electrical transmission by granule cells. Brain Res. 1487, 107–122 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.05.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahiro M., Arakawa O., Narahashi T. (1991). Modulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor-channel complex by alcohols. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 259, 235–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naus C. C., Bechberger J. F., Paul D. L. (1991). Gap junction gene expression in human seizure disorder. Exp. Neurol. 111, 198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemani V. M., Binder D. K. (2005). Emerging role of gap junctions in epilepsy. Histol. Histopathol. 20, 253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen K. E., Kelso A. R., Cock H. R. (2006). Antiepileptic effect of gap-junction blockers in a rat model of refractory focal cortical epilepsy. Epilepsia 47, 1169–1175 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orellana J. A., Diaz E., Schalper K. A., Vargas A. A., Bennett M. V., Saez J. C. (2011). Cation permeation through connexin 43 hemichannels is cooperative, competitive and saturable with parameters depending on the permeant species. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 409, 603–609 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pais I., Hormuzdi S. G., Monyer H., Traub R. D., Wood I. C., Buhl E. H., et al. (2003). Sharp wave-like activity in the hippocampus in vitro in mice lacking the gap junction protein connexin 36. J. Neurophysiol. 89, 2046–2054 10.1152/jn.0549.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratov Y., Lalo U., Krishtal O. A., Verkhratsky A. (2009). P2X receptors and synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience 158, 137–148 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual O., Casper K. B., Kubera C., Zhang J., Revilla-Sanchez R., Sul J. Y., et al. (2005). Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science 310, 113–116 10.1126/science.1116916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D., Zhang X., Veenstra R. D. (2014). Connexin hemichannel and pannexin channel electrophysiology: How do they differ? FEBS Lett. 588, 1372–1378 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penuela S., Bhalla R., Gong X. Q., Cowan K. N., Celetti S. J., Cowan B. J., et al. (2007). Pannexin 1 and pannexin 3 are glycoproteins that exhibit many distinct characteristics from the connexin family of gap junction proteins. J. Cell Sci. 120, 3772–3783 10.1242/jcs.009514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penuela S., Bhalla R., Nag K., Laird D. W. (2009). Glycosylation regulates pannexin intermixing and cellular localization. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4313–4323 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereda A. E. (2014). Electrical synapses and their functional interactions with chemical synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 250–263 10.1038/nrn3708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Velazquez J. L., Carlen P. L. (2000). Gap junctions, synchrony and seizures. Trends Neurosci. 23, 68–74 10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01497-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Velazquez J. L., Valiante T. A., Carlen P. L. (1994). Modulation of gap junctional mechanisms during calcium-free induced field burst activity: a possible role for electrotonic coupling in epileptogenesis. J. Neurosci. 14, 4308–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhade S. N., Jensen F. E. (2009). Epileptogenesis in the immature brain: emerging mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 5, 380–391 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retamal M. A., Schalper K. A., Shoji K. F., Bennett M. V., Saez J. C. (2007). Opening of connexin 43 hemichannels is increased by lowering intracellular redox potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8322–8327 10.1073/pnas.0702456104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risher W. C., Eroglu C. (2012). Thrombospondins as key regulators of synaptogenesis in the central nervous system. Matrix Biol. 31, 170–177 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross F. M., Gwyn P., Spanswick D., Davies S. N. (2000). Carbenoxolone depresses spontaneous epileptiform activity in the CA1 region of rat hippocampal slices. Neuroscience 100, 789–796 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00346-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N., Koulakoff A., Abudara V., Willecke K., Giaume C. (2008). Astroglial metabolic networks sustain hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science 322, 1551–1555 10.1126/science.1164022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N., Segal M., Koulakoff A., Giaume C., Avignone E. (2003). Carbenoxolone blockade of neuronal network activity in culture is not mediated by an action on gap junctions. J. Physiol. 553, 729–745 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental R., Andrade-Rozental A. F., Zheng X., Urban M., Spray D. C., Chiu F. C. (2001). Gap junction-mediated bidirectional signaling between human fetal hippocampal neurons and astrocytes. Dev. Neurosci. 23, 420–431 10.1159/000048729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental R., Srinivas M., Gokhan S., Urban M., Dermietzel R., Kessler J. A., et al. (2000). Temporal expression of neuronal connexins during hippocampal ontogeny. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 32, 57–71 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00096-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez J. C., Retamal M. A., Basilio D., Bukauskas F. F., Bennett M. V. (2005). Connexin-based gap junction hemichannels: gating mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1711, 215–224 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salameh A., Dhein S. (2005). Pharmacology of gap junctions. New pharmacological targets for treatment of arrhythmia, seizure and cancer? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1719, 36–58 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoilova M., Li J., Pelletier M. R., Wentlandt K., Adamchik Y., Naus C. C., et al. (2003). Epileptiform activity in hippocampal slice cultures exposed chronically to bicuculline: increased gap junctional function and expression. J. Neurochem. 86, 687–699 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01893.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoilova M., Wentlandt K., Adamchik Y., Velumian A. A., Carlen P. L. (2008). Connexin 43 mimetic peptides inhibit spontaneous epileptiform activity in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Exp. Neurol. 210, 762–775 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago M. F., Veliskova J., Patel N. K., Lutz S. E., Caille D., Charollais A., et al. (2011). Targeting pannexin1 improves seizure outcome. PLoS ONE 6:e25178 10.1371/journal.pone.0025178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayyah M., Kaviani B., Khoshkholgh-Sima B., Bagheri M., Olad M., Choopani S., et al. (2012). Effect of chronic intracerebroventricluar administration of lipopolysaccharide on connexin43 protein expression in rat hippocampus. Iran. Biomed. J. 16, 25–32 10.6091/IBJ.1030.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E., Spray D. C., Meda P. (2009). Connexins, pannexins, innexins: novel roles of “hemi-channels.” Pflugers Arch. 457, 1207–1226 10.1007/s00424-008-0591-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalper K. A., Palacios-Prado N., Retamal M. A., Shoji K. F., Martinez A. D., Saez J. C. (2008). Connexin hemichannel composition determines the FGF-1-induced membrane permeability and free [Ca2+]i responses. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3501–3513 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert G., Schilling K., Steinhauser C. (2006). Astrocyte dysfunction in neurological disorders: a molecular perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 194–206 10.1038/nrn1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar E., Derchansky M., Carlen P. L. (2009). The role of altered tissue osmolality on the characteristics and propagation of seizure activity in the intact isolated mouse hippocampus. Clin. Neurophysiol. 120, 673–678 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone T. A., Simeone K. A., Samson K. K., Kim Do Y., Rho J. M. (2013). Loss of the Kv1.1 potassium channel promotes pathologic sharp waves and high frequency oscillations in in vitro hippocampal slices. Neurobiol. Dis. 54, 68–81 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A., Traub R. D., Vladimirov N., Jenkins A., Nicholson C., Whittaker R. G., et al. (2013). Gap junction networks can generate both ripple-like and fast ripple-like oscillations. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 46–60 10.1111/ejn.12386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A., Traub R. D., Vladimirov N., Jenkins A., Nicholson C., Whittaker R. G., et al. (2014). Gap junction networks can generate both ripple-like and fast ripple-like oscillations. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 46–60 10.1111/ejn.12386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl G., Guldenagel M., Beck H., Teubner B., Traub O., Gutierrez R., et al. (2000). Expression of connexin genes in hippocampus of kainate-treated and kindled rats under conditions of experimental epilepsy. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 83, 44–51 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00195-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl G., Willecke K. (2004). Gap junctions and the connexin protein family. Cardiovasc. Res. 62, 228–232 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somjen G. G. (2002). Ion regulation in the brain: implications for pathophysiology. Neuroscientist 8, 254–267 10.1177/1073858402008003011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas M., Hopperstad M. G., Spray D. C. (2001). Quinine blocks specific gap junction channel subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10942–10947 10.1073/pnas.191206198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas M., Spray D. C. (2003). Closure of gap junction channels by arylaminobenzoates. Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 1389–1397 10.1124/mol.63.6.1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staba R. J., Wilson C. L., Bragin A., Jhung D., Fried I., Engel J., Jr. (2004). High-frequency oscillations recorded in human medial temporal lobe during sleep. Ann. Neurol. 56, 108–115 10.1002/ana.20164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser C., Seifert G. (2002). Glial membrane channels and receptors in epilepsy: impact for generation and spread of seizure activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 447, 227–237 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01846-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser C., Seifert G., Bedner P. (2012). Astrocyte dysfunction in temporal lobe epilepsy: K+ channels and gap junction coupling. Glia 60, 1192–1202 10.1002/glia.22313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stridh M. H., Tranberg M., Weber S. G., Blomstrand F., Sandberg M. (2008). Stimulated efflux of amino acids and glutathione from cultured hippocampal slices by omission of extracellular calcium: likely involvement of connexin hemichannels. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10347–10356 10.1074/jbc.M704153200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M., Tong X. X. (2010). [Astrocytic gap junction in the hippocampus of rats with lithium pilocarpine-induced epilepsy]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 30, 2738–2741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutor B., Hagerty T. (2005). Involvement of gap junctions in the development of the neocortex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1719, 59–68 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykova E. (2004). Diffusion properties of the brain in health and disease. Neurochem. Int. 45, 453–466 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szente M., Gajda Z., Said Ali K., Hermesz E. (2002). Involvement of electrical coupling in the in vivo ictal epileptiform activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the neocortex. Neuroscience 115, 1067–1078 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00533-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi D. K., Vargas J. R., Wilcox K. S. (2010). Increased coupling and altered glutamate transport currents in astrocytes following kainic-acid-induced status epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 40, 573–585 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. J., Jackson M. F., Olah M. E., Rungta R. L., Hines D. J., Beazely M. A., et al. (2008). Activation of pannexin-1 hemichannels augments aberrant bursting in the hippocampus. Science 322, 1555–1559 10.1126/science.1165209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. J., Macvicar B. A. (2008). Connexin and pannexin hemichannels of neurons and astrocytes. Channels 2, 81–86 10.4161/chan.2.2.6003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub R. D., Contreras D., Whittington M. A. (2005). Combined experimental/simulation studies of cellular and network mechanisms of epileptogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 22, 330–342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub R. D., Draguhn A., Whittington M. A., Baldeweg T., Bibbig A., Buhl E. H., et al. (2002). Axonal gap junctions between principal neurons: a novel source of network oscillations, and perhaps epileptogenesis. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 1–30 10.1515/REVNEURO.2002.13.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub R. D., Michelson-Law H., Bibbig A. E., Buhl E. H., Whittington M. A. (2004). Gap junctions, fast oscillations and the initiation of seizures. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 548, 110–122 10.1007/978-1-4757-6376-8_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub R. D., Schmitz D., Jefferys J. G., Draguhn A. (1999). High-frequency population oscillations are predicted to occur in hippocampal pyramidal neuronal networks interconnected by axoaxonal gap junctions. Neuroscience 92, 407–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez Y., Mendez B., Trueta C., De-Miguel F. F. (2009). Summation of excitatory postsynaptic potentials in electrically-coupled neurones. Neuroscience 163, 202–212 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verselis V. K., Srinivas M. (2008). Divalent cations regulate connexin hemichannels by modulating intrinsic voltage-dependent gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 132, 315–327 10.1085/jgp.200810029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivar C., Traub R. D., Gutierrez R. (2012). Mixed electrical-chemical transmission between hippocampal mossy fibers and pyramidal cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 35, 76–82 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07930.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss L. J., Jacobson G., Sleigh J. W., Steyn-Ross A., Steyn-Ross M. (2009). Excitatory effects of gap junction blockers on cerebral cortex seizure-like activity in rats and mice. Epilepsia 50, 1971–1978 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallraff A., Kohling R., Heinemann U., Theis M., Willecke K., Steinhauser C. (2006). The impact of astrocytic gap junctional coupling on potassium buffering in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 26, 5438–5447 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0037-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Yang J., Liu P., Bi X., Li C., Zhu K. (2012). NAD induces astrocyte calcium flux and cell death by ART2 and P2X7 pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 746–752 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willecke K., Eiberger J., Degen J., Eckardt D., Romualdi A., Guldenagel M., et al. (2002). Structural and functional diversity of connexin genes in the mouse and human genome. Biol. Chem. 383, 725–737 10.1515/BC.2002.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Zeng L. H., Wong M. (2009). Impaired astrocytic gap junction coupling and potassium buffering in a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurobiol. Dis. 34, 291–299 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylinen A., Bragin A., Nadasdy Z., Jando G., Szabo I., Sik A., et al. (1995). Sharp wave-associated high-frequency oscillation (200 Hz) in the intact hippocampus: network and intracellular mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 15, 30–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J. J., Green C. R., O'carroll S. J., Nicholson L. F. (2010). Dose-dependent protective effect of connexin43 mimetic peptide against neurodegeneration in an ex vivo model of epileptiform lesion. Epilepsy Res. 92, 153–162 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zador Z., Weiczner R., Mihaly A. (2008). Long-lasting dephosphorylation of connexin 43 in acute seizures is regulated by NMDA receptors in the rat cerebral cortex. Mol. Med. Rep. 1, 721–727 10.3892/mmr_00000019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. L., Zhang L., Carlen P. L. (2004). Electrotonic coupling between stratum oriens interneurones in the intact in vitro mouse juvenile hippocampus. J. Physiol. 558, 825–839 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Chen G., Zhou W., Song A., Xu T., Luo Q., et al. (2007). Regulated ATP release from astrocytes through lysosome exocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 945–953 10.1038/ncb1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]