Abstract

Great strides have been made in understanding the epidemiology of EoE over the past two decades. Initial research focused on case description and characterization of the burden of disease. Research is now shifting to risk factor ascertainment, resulting in new and intriguing etiologic hypotheses. This paper will review the current knowledge related to the epidemiology of EoE. Demographic features and natural history will be described, data summarizing the prevalence and incidence of EoE throughout the world will be highlighted, and risk factors for EoE will be discussed. EoE can occur at any age, there is a male predominance, it is more common in Whites, and there is a strong association with atopic diseases. EoE is chronic, relapses are frequent, and persistent inflammation increases the risk of fibrostenotic complications. The prevalence is currently estimated at 0.5–1 in 1000, and EoE is now the most common cause of food impaction. EoE can be seen in 2–7% of patients undergoing endoscopy for any reason, and 12–23% undergoing endoscopy for dysphagia. The incidence of EoE is approximately 1/10,000 new cases per year, and the rise in incidence is outpacing increases in recognition and endoscopy volume. The reasons for this evolving epidemiology are not yet fully delineated, but possibilities include changes in food allergens, increasing aeroallergens and other environmental factors, the decrease of H. pyloriand early life exposures.

Keywords: Eosinophilic esophagitis, epidemiology, incidence, prevalence, risk factors, natural history

Introduction

Epidemiology is the study of patterns and causes of diseases in defined populations. It uses observational study designs, such as case-control or cohort studies, to make inferences about etiologies and risk factors for diseases. These results generate hypotheses that can subsequently be tested in experimental study designs, such as clinic trials. Over the past two decades, there have been great strides made in understanding the epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Case reports and case series provided initial descriptions of clinical characteristics of patients with EoE,1–4 and then as larger cohorts were reported and natural history data accumulated,5–11 formal disease definitions and guidelines were put forth.12–14 Epidemiologic techniques have been used to estimate the incidence and prevalence of EoE at the single center, regional, and national levels to provide an understanding of trends in the number of cases as well as the burden of disease attributable to EoE.15–22 The clear result of these studies is that EoE is rapidly increasing both in incidence and in prevalence. Investigations have also begun to determine potential etiologic factors that might explain this evolving epidemiology. This paper will review the current knowledge base related to the epidemiology of EoE. In particular, demographic features and natural history will be described, data summarizing the prevalence and incidence of EoE throughout the world will be highlighted, and risk factors for EoE will be discussed.

Demographic features

EoE has been reported throughout the lifespan, from infancy to almost 100 years of age.10,13,23 However, the majority of cases are in children, adolescents, and adults under the age of 50.10,13,22–24 There is a consistent gender discrepancy, with males affected three to four times more commonly than females, and EoE is also more frequently reported in Whites compared with other races/ethnicities.11,13,19,22,24–27 The reason for the male predominance is not known, and as more data accrues from larger centers with more diverse patient populations, increasing numbers of racial minorities have been identified with EoE.28–31 While the majority of clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features are shared by EoE patients of different races, some data suggest that African-Americans with EoE may be diagnosed at earlier ages and are less likely to have typical endoscopic findings of EoE.28,31 EoE is also strongly associated with atopic disease and can run in families; both of these topics, as well as the clinical features and differences in the presentation between adults and children, are addressed in detail in other articles in this issue.

Natural History

EoE is considered a chronic disease.12–14 Data from the placebo arms of randomized clinical trials32–38 and prospective and retrospective cohort studies5–7,10,11,39–41 show that EoE does not tend to spontaneously resolve or “burn-out”. Specifically, the endoscopic signs and esophageal eosinophilia persist in the absence of treatment. Moreover, if treatment is stopped, symptoms, endoscopic signs, and esophageal eosinophilia recur in the vast majority of patients over a period of several months.8,41–45 There are as of yet no published reports of EoE transforming into hypereosinophilic syndrome, extending to involve other areas of the GI tract, or causing a malignancy.6,7,10,11,40

Recent data have supported the concept that EoE may progress from an inflammatory-predominant phenotype (primarily seen in children) to a fibrosis-predominant one (seen in adults).13,46–48 These data help to explain the clinical differences between adults and children,11,39,49,50 and are consistent with basic science work showing that esophageal remodelling and deposition of fibrosis are key pathogenic features of EoE.51,52 The hypothesis is that in children, eosinophilic inflammation in the esophagus manifests with white plaques or exudates, decreased vascularity or mucosa edema, and linear furrows, but without esophageal rings or strictures, and causes symptoms such as pain, heartburn, and failure to thrive. With ongoing inflammation, however, subepithelial collagen is deposited, esophageal rings, narrowing, and strictures develop, and symptoms become dysphagia predominant.

A retrospective cohort study of patients in Switzerland explored this issue by assessing diagnostic delay – how long patients experienced symptoms prior to the EoE diagnosis and before any treatment – as a proxy for ongoing inflammation.53 There was a very strong association between increasing diagnostic delay and the prevalence of strictures at diagnosis. For example, only 17% of those with less than 2 years of symptoms prior to diagnosis had strictures compared with 71% with more than 20 years of symptoms. They calculated that for every increased decade of untreated EoE, there was a doubling of odds of having an esophageal stricture. Another study assessed the same issue by examining endoscopically-defined phenotypes of EoE and noted nearly identical results, with the odds of having a fibrostenotic EoE phenotype doubling with each increasing decade of age.48 These natural history data provide important information for patients, show long term consequences of EoE, and support the need for treatment of this condition.

Prevalence

The prevalence of a condition is defined by how many total cases exist during a given time frame in a specified location, and is a useful measure of the burden of that disease. EoE has been described in many places throughout the world including North America, Europe, South America, Australia, Asia, and the Middle East, but the prevalence appears to be highest in the U.S., Western Europe, and Australia as compared with Japan or China.17–22,54–62 As of yet, there are no reported EoE cohorts in sub-Saharan Africa or India.

The prevalence of EoE depends on the population that is studied, the definition of EoE that was used (and whether the study was conducted before the recognition of proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia [PPI-REE]),13,14 and the study methodology (prospective vs retrospective), and this contributes to variation in the range of prevalence estimates (Tables 1 and 2). While the majority of prevalence estimates are derived from single-centers with defined catchment areas,15,16,18,20,58,59,63,64 there are some studies that have used either population-based techniques or national databases to attempt to generate more accurate or generalizable estimates.17,21,22,65–67 Because EoE is chronic and non-fatal, studies universally report an increasing prevalence of EoE regardless of the geographic location.54,68

Table 1.

Population-based estimates of the prevalence of EoE

| Author | Location | Population | Time frame | Prevalence (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noel; Buckmeier | Hamilton County, OH | Pediatric | 2000–2003; 2000–2006 | 43.0; 90.7 |

| Cherian | Perth, Australia | Pediatric | 1995, 1999, 2004 | 89.0 |

| Straumann; Hruz | Olten County, Switzerland | Adult | 1989–2004; 1989–2009 | 23.0 42.8 |

| Ronkainen | Northern Sweden | Adult | 1998–2001 | 400 |

| Prasad | Olmstead County, MN | Adult and pediatric | 1976–2005 | 55.0 |

| Gill | Huntington region, WV | Pediatric | 1995–2004 | 73.0 |

| Dalby | Southern Denmark | Pediatric | 2005–2007 | 2.3 |

| Spergel | United States | Adult and pediatric | 2010 | 52.2 |

| Ally | United States (military) | Adult and pediatric | 2009 | 9.7 |

| van Rhijn | Netherlands | Adult and pediatric | 1996–2010 | 4.1 |

| Syed | Calgary, Canada | Adult and pediatric | 2004–2008 | 33.7 |

| Arias | Castilla-La Manch region, Spain | Adult and pediatric | 2005–2011 | 44.6 |

| Dellon | United States | Adult and pediatric | 2009–2011 | 56.7 |

Table 2.

Prevalence of EoE in selected patient populations undergoing endoscopy

| Author | Population | Time frame | Prevalence (per 100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients undergoing endoscopy for any reason | |||

| Veerappan | Adults | 2007 | 6.5 |

| Joo | Adults | 2009 | 6.6 |

| Sealock | Adults (VA population) | n/a | 2.4 |

| Patients undergoing endoscopy for dysphagia | |||

| Prasad | Adults | 2005–2006 | 15 |

| Mackenzie | Adults | 2005–2007 | 12 |

| Ricker | Adults (non-obstructive dysphagia only) | 2007–2009 | 22 |

| Dellon | Adults | 2009–2011 | 23 |

| Patients undergoing endoscopy for food bolus impaction | |||

| Desai | Adults | 2000–2003 | 55 |

| Kerlin | Adults | n/a | 50 |

| Sperry | Adults and pediatric | 2002–2009 | 46 |

| Hurtado | Pediatric | 2005–2009 | 63 |

| Patients undergoing endoscopy for refractory reflux | |||

| Liacouras | Pediatric | 1993–1995 | 3 |

| Rodrigro | Adult | 2002–2005 | 0.2 |

| Veerappan | Adult | 2007 | 8 |

| Sa | Adult | 2006–2008 | 1 |

| Poh | Adult | n/a | 1 |

| Foroutan | Adult | 2006 | 8 |

| Garcia-Campean | Adult | 2007–2009 | 4 |

| Dellon | Adult | 2009–2011 | 2 |

| Patients undergoing endoscopy for non-cardiac chest pain | |||

| Achem | Adult | 2006–2007 | 6 |

| Patients undergoing endoscopy for abdominal pain | |||

| Thakkar | Pediatric | 2007–2010 | 4 |

| Patients with refractory aerodigestive symptoms | |||

| Hill | Pediatric | 2003–2013 | 4 |

Prevalence of EoE in the general population

How common is EoE? In reviewing data assessing the prevalence of EoE in general populations (Table 1), a reasonable answer is 0.5–1 cases/1000 persons. The majority of estimates in the U.S. range from 40–90 cases/100,000 persons.15,18,19,22,63,65 The largest study in the U.S. examined administrative health claims data and found the prevalence to be 57/100,000, or approximately 152,000 cases, with a range from 39–153/100,000 (106,000–411,000 cases), based on the case definition that was used.22,69 These are consistent with the most recent estimates from Australia (89/100,000),58 Switzerland (43/100,000),20 Spain (45/100,000),59 and Canada (34/100,000).67 Additionally, these prevalence estimates are of the same order of magnitude of pediatric Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and are beginning to approach the prevalence of IBD overall,70 a remarkable observation given that EoE was essentially unknown two decades ago.

Several studies, however, provide estimates that are outside of this range. In Northern Sweden, data from a population-based study assessing the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus was reanalyzed and found a prevalence of 400/100,000 for EoE.17 These patients were largely asymptomatic and while they had esophageal eosinophilia, may not have met current diagnostic criteria for EoE.13,14 A study in the U.S. military found a prevalence of 10/100,000, but this might have been an underestimate due to the specialized population assessed or to low sensitivity of the administrative code for EoE.66,69 Studies from the Netherlands and the southern region of Denmark have also reported lower prevalences of EoE.21,64 It is unknown if these results are due to practice patterns in those countries or a true difference in the prevalence of disease.

Prevalence of EoE in patients undergoing endoscopy

While these prior studies assessed the overall prevalence of EoE, depending on the specific patient population seen in health care settings the prevalence may be orders of magnitude higher (Table 2). For example, a prospective study which collected esophageal biopsies on consecutive patients undergoing upper endoscopy for any indication found that 6.5% of patients were diagnosed with EoE.26 Other studies with a similar design found comparable rates, from 2.4% to 6.6%.71,72 Given that there are approximately 6.9 million upper endoscopies performed annually in the U.S.,73 endoscopists should expect to commonly encounter EoE in the procedure suite.

EoE is even more common in patients undergoing upper endoscopy for symptoms of dysphagia. In three prospectively studies conducted in this focused patient population, the prevalence of EoE ranged from 12–22%.25,74,75 Not every patient in these studies with a finding of esophageal eosinophilia, however, would meet current diagnostic guidelines with exclusion of PPI-REE, because patients were enrolled prior to the recognition of this phenomenon. A recent study conducted in an esophageal referral center reported an EoE prevalence of 23% for patients undergoing endoscopy for dysphagia, after excluding those patients with PPI-REE.76 In that study, esophageal eosinophilia itself was seen in 40% of those undergoing upper endoscopy for dysphagia, before a PPI trial was conducted. Given that approximately 20% of all upper endoscopies performed are for an indication of dysphagia,73 EoE must be highly suspected in this population.

In the most extreme form of dysphagia, esophageal food bolus impaction requiring a visit to an emergency department and urgent endoscopy, EoE is now the most frequent condition identified. In this setting, between 46–63% of patients with food impaction will have EoE.77–80 These data, however, are somewhat limited because less than half of patients with food or foreign body impactions will have esophageal biopsies to evaluate for esophageal eosinophilia,78,80 so EoE in this setting may still be underdiagnosed. If patients have a bolus impaction and no biopsies are obtained, it is reasonable to perform a follow-up procedure to identify the underlying etiology.

The prevalence of EoE in patients undergoing endoscopy for other upper GI symptoms has also been described. For patients with heartburn-predominant symptom who don’t respond clinically to PPI therapy (PPI-refractory reflux), EoE has been identified as the cause 1%-8% of the time.26,42,61,76,81–84 In adults with non-cardiac chest pain, one study found that EoE was the etiology in 6%.85 In children undergoing upper endoscopy for abdominal pain, the frequency of EoE was 4%,86 and in children undergoing multispecialty evaluation for refractory aerodigestive symptoms, it was also 4%.87

While these epidemiologic data have utility for understanding how common EoE is, building a differential diagnosis for patients undergoing endoscopy, and measuring the burden of disease attributable to EoE, they also imply a practical point. Because EoE is common in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures, practitioners should strongly consider the diagnosis and obtain esophageal biopsies to evaluate for it. Currently guidelines recommend obtaining biopsies for all patients presenting with dysphagia, regardless of the endoscopic appearance.12–14 There is also a recent analysis that suggests if the clinical probability of EoE is at least 8–10%, obtaining biopsies in patients with PPI-refractory reflux is also cost-effective.88

Incidence

The incidence of a condition is how many new cases occur during a given time frame in a specified location, and is a measure of the number of people newly affected by a disease. The incidence of a condition can be low (a small number of new cases), but the prevalence can be relatively high if the condition is chronic and does not impact longevity. Additionally, the incidence of a condition can be roughly equivalent to the prevalence for a condition that is either short-lived or highly morbid.

In order to study the incidence of a condition, it is necessary not only to detect all new (incident) cases, but to ensure that existing (prevalent) cases are not falsely counted as new cases. In EoE, this has been accomplished primarily at referral centers in regions where the patient population and catchment area is well defined,15,19,20,59,64 but there are some emerging regional and national data as well.21,67 The majority of the reports estimate the incidence of EoE from 6–13 cases/100,000 persons (Table 3). The two studies that report lower incidence rates, from the Netherlands and the southern Denmark, were the same ones that reported lower prevalences rates.21,64

Table 3.

Population-based estimates of the incidence of EoE*

| Author | Location | Population | Time frame | Incidence (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noel | Hamilton County, OH | Pediatric | 2003 | 12.8 |

| Hruz | Olten County, Switzerland | Adult | 2007–2009 | 7.4 |

| Prasad | Olmstead County, MN | Adult and pediatric | 2001–2005 | 9.5 |

| Dalby | Southern Denmark | Pediatric | 2005–2007 | 1.6 |

| van Rhijn | Netherlands | Adult and pediatric | 2010 | 1.3 |

| Syed | Calgary, Canada | Adult and pediatric | 2004–2008 | 11 |

| Arias | Castilla-La Manch region, Spain | Adult and pediatric | 2005–2011 | 6.4 |

Increasing incidence and risk factors

Studies are consistent in showing that the incidence of EoE has been rising rapidly. In a report from Hamilton County, Ohio, the incidence of EoE was noted to increase from 9 to 12.8/100,000 over a three year period.15 In a report from Olmstead County, Minnesota, no EoE cases were seen before 1990, but in the incidence rose from 0.35 to 9.5/100,000 over a 15 year period.19 Similar increases have been reported in Switzerland (1.2 to 7.4/100,000 over a 20 year period)20 and in the Netherlands (0.01 to 1.3/100,000 over 14 years).21 This increasing incidence has also been reflected in temporal trends in the relative prevalence of dysphagia etiologies, with EoE becoming a more frequent cause of dysphagia over time.89

Why is eosinophilic esophagitis increasing?

While these marked changes in EoE incidence account for its increasing prevalence, they also beg the question of why is the incidence itself increasing? While the answer is not known, there are a number of hypothesis.90 One explanation is simply that EoE is increasing because of increasing recognition; the condition was always there but given the research and clinical interest in the condition, practitioners are more aware of EoE, have a higher degree of suspicion when performing endoscopy, take more esophageal biopsies, and are therefore more likely to make the diagnosis. The exponential increase in the number of publications related to EoE is a testament to the increased interest in EoE (from 0–1 publication per year prior to 2000, to >200 publications in 2013). Some data that support this theory show that the increase in incidence rates relatively closely matches the increase in endoscopy volume or biopsy rates.67,91 However, there are other studies where biopsy rates do increase 2–3 times over the study period, but the incidence of EoE outpaces that increase by several fold, indicating that increased recognition is not the only explanation.11,19,89,92 Additionally, in studies where archived pathology samples have been retrieved and reanalyzed, cases of probable EoE identified in the early 1980s and 1990s occur at lower rates that what is currently being observed.93,94

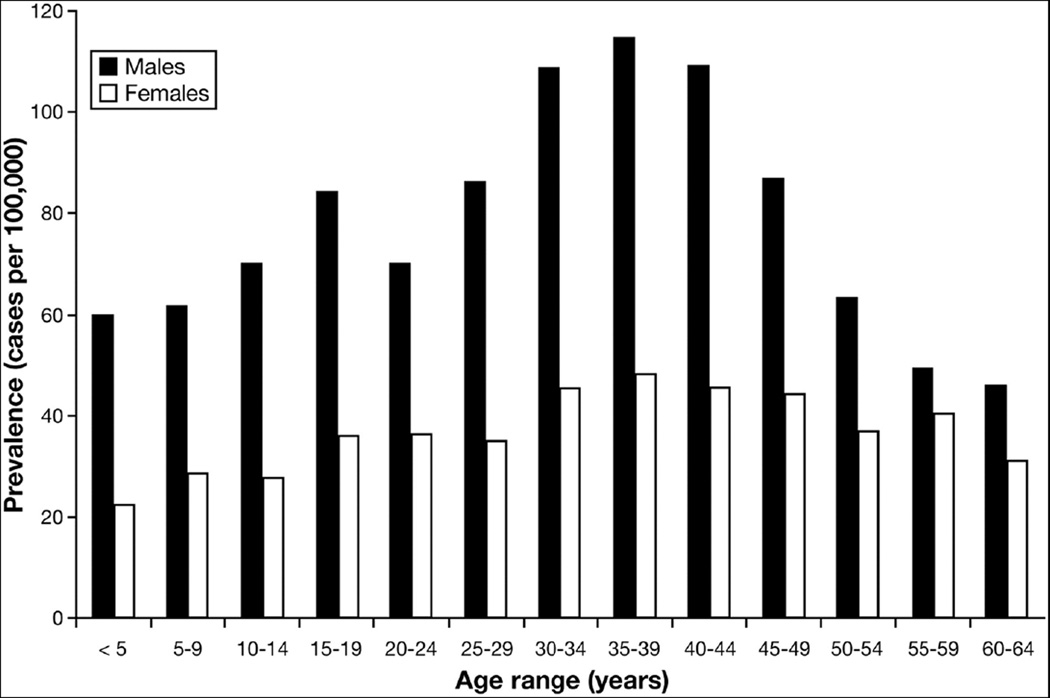

There are other epidemiologic clues that provide insight. Recent data suggest that the prevalence of EoE steadily increases as age increases, peaks in the 35–45 age range, and then decreases (Figure 1).22 This is a counterintuitive observation for a chronic and non-fatal disease (where prevalence would be expected to continue to increase as age increases), and suggests a possible cohort effect. It is interesting to speculate whether something might have changed in the environment 40–50 years ago that began to affect children born after that time, but did not affect older individuals. In contrast, genetic changes would not be expected to impact a new disease over a relatively short time frame. This time frame is also consistent with decades-long symptom duration prior to EoE diagnosis in some older patients with EoE.23,48,90,95

Figure 1.

Prevalence of EoE (cases per 100,000) in the United States as stratified by sex and by 5 year increments of age, in a study of an administrative health claims data. From Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; with permission.

Allergen and hygiene hypotheses

There are a number of etiologic risk factors that have either been identified or hypothesized to contribute to the increase of EoE (Box 1). One possibility relates to EoE as an allergic disease (see also the article on allergic mechanisms in this issue of Clinics). All allergic diseases, including asthma, atopic dermatis, allergic rhinitis, and food allergies, have been increasing in recent decades.96 One global explanation for this is the hygiene hypothesis, which holds that because the environment in developed counties has become much more sterile, human immune systems are exposed to smaller variety of antigens, and tolerance is less likely to develop.96 Thus, EoE as an allergen/immune-mediated disease would be rising in parallel with other allergic diseases.

Box 1.

Potential etiologic risk factors for EoE

| • | Aeroallergens |

| • | Food allergens |

| • | Helicobacter pylori (protective) |

| • | Proton pump inhibitors |

| • | Cold or arid climates |

| • | Population density (urban vs rural locations) |

| • | Early life factors (antibiotic use; cesarian section) |

| • | Connective tissue disorders |

Environmental hypotheses

Related to the hygiene hypothesis are theories that changing environmental factors are contributing to the rise in EoE. One factor is aeroallergens. There have been clear links in humans between pollen and other aeroallergen exposure either triggering EoE or correlating with EoE disease activity.97–99 Additionally, many studies have shown a link between the season of the year and EoE diagnosis, with EoE more commonly being diagnosed in summer or fall, times of potentially higher aeroallergen activity.11,19,100,101 Other environmental exposures such as air pollution or industrial exposures, have yet to be formally assessed.

Geographic risk factors have also been reported. Several studies have utilized a large nationwide pathology database containing hundreds of thousands of patients undergoing endoscopy with esophageal biopsy, and representing more than 14,000 cases of esophageal eosinophilia and EoE.102,103 Prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia was noted to vary by climate zone, with cases more commonly noted in arid and cold weather climates.102 This was an interesting finding because the climate zone classification used is closely linked to types of vegetation, again raising the question of allergen exposure, and also because other autoimmune and allergic diseases have geographic variation with a north-south gradient. A related study showed that esophageal eosinophilia appeared to be more common in rural areas with low population density.103 While this may be counterintuitive (some allergic diseases such as asthma and atopic dermatitis are felt to be more common in urban areas), there are other studies on EoE that support this as well.65,104 This raises the question of whether vegetation or environmental exposures more likely to be found in rural areas are risk factors for EoE, but additional research is required to explore these possibilities.

Food allergens can also be considered environmental exposures. It is well-established that foods can trigger EoE and that allergen-free elemental formula or elimination of certain food allergens from the diet can result in clinical, endoscopic, and histologic remission (see also the article on dietary therapy of EoE in this issue of Clinics).4,5,45,105,106 However, it is less clear why foods that have been tolerated for much of human history are now allergic triggers in EoE. Whether this is because of recent changes in agricultural practices, decreased variety of foods, genetic modification of crops, pesticides, antibiotic or hormone use in livestock, or other factors such as packaging and transport of foods remains to be determined.

Helicobacter pylori hypothesis

When thinking about reasons that EoE may be increasing, it is possible that something being removed from the environment could also play a role. Helicobacter pylori is one such factor. Since its formal characterization in the early 1980s and subsequent association with peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer, the prevalence of H. pylori has markedly decreased in the U.S. with ongoing treatment of this pathogen.107 In a study examining more than 165,000 paired esophageal and gastric biopsy samples, there was a strong inverse relationship between H. pylori and esophageal eosinophilia; those who were more likely to have esophageal eosinophilia or EoE were less likely to have H. pylori.108 This relationship has also been noted in two smaller studies in EoE,17,109 and is consistent with the observation that H. pylori is inversely associated with other atopic disorders such as asthma and eczema.110 The mechanism by which H. pylori may be protective of EoE is not known, but it has been hypothesized that the infection polarizes the immune system towards a Th1 response, and the lack of infection might allow a Th2 response, less tolerance, and increased atopy.108

Proton pump inhibitor hypothesis

Another potential ecological association to explain the increase in EoE is the parallel increase in use of PPI medications over the past three decades. This increase in use has also been noted in infants as a treatment for reflux and colic, which represents a major change in practice during a time when the immune system is developing.111 While there is no direct evidence that PPI use has caused EoE in an individual patient, there are some intriguing mechanistic reasons that this could be a concern, especially given the multitude of effects that PPI have outside of their antisecretory action.112,113 Specifically, PPIs can increase upper GI tract permeability, potentially creating a new route of antigen exposure, and their use has also been associated with the development of new food-specific IgE antibodies.112,114–116 However, these data are balanced by two important points. First, many patients who are diagnosed with EoE have never taken a PPI previously. Second, convincing data show that PPIs have anti-inflammatory/anti-eosinophil effects both in vitro117 and in vivowhere at least 30–40% of subjects with esophageal eosinophilia have symptomatic and histologic resolution after a PPI trial.76,118,119 Because of this, a PPI trial is now a required part of the EoE diagnostic algorithm.12–14 Therefore, before PPIs can be considered to be a cause of EoE, direct evidence will be required.

Early life exposure hypotheses

A new area of investigation has started to examine early life exposures that might predispose to development of EoE. It has been noted that antibiotic exposure in early life increases the odds of developing other allergic diseases such as asthma or atopic dermatitis and inflammatory bowel disease, especially Crohn’s disease.120–122 There are recent pilot data suggesting the same may be true in EoE, where exposures during the first year of life were assessed and the subsequent odds of pediatric EoE determined.123 In this study, infants who received antibiotics were markedly more likely to have EoE than controls who did not, and there was also a trend for increased EoE in infants delivered by cesarian section, those who were born prematurely, and those who had non-exclusive breastfeeding. All of these factors could theoretically impact the early life microbiome, perturbations of which have been hypothesized to be a determinant of atopic disease.124 Novel research techniques in EoE have begun to characterize to esophageal microbiome, but this has yet to be fully explored as a risk factor for EoE.125

Other hypotheses

A final set of risk factors for EoE that have been recently identified are connective tissue and autoimmune disorders. A report in a large cohort of EoE patients found a subset with coexisting diseases such as Ehlers-Danlos, Marfan, and Loeys-Dietz syndromes, in which EoE was significantly elevated compared to expected rates in the general population.126 Moreover, this association suggested potential genetic links that could be used to learn more about the pathogenesis of EoE. In a preliminary study using administrative data, a similar relationship between EoE and connective tissue disorders were noted, and there was also a relationship with autoimmune diseases.127

Summary

The epidemiology of EoE has become increasingly well understood over the past decade. The disease is well characterized clinically, and those features have informed diagnostic guidelines. EoE can affect patients of any age, but there is a male predominance, it is more common in Whites, and there is a strong association with atopic diseases. EoE is chronic, relapses are frequent with cessation of treatment, and new data suggest that unopposed inflammation and persistent symptoms with diagnostic delay increases the risk of fibrostenotic complications. The prevalence of EoE is rising substantially, and it is now the most common cause of food impaction in patients presenting to the emergency department, and is frequently encountered in the endoscopy suite. Approximately 0.5–1 in 1000 people are estimated to have EoE, a prevalence that is beginning to approach that of inflammatory bowel disease. Incidence estimates suggest that there are 1/10,000 new cases per year, and the rise in incidence is outpacing the increasing in recognition and endoscopy volume. The reasons for this evolving epidemiology are not yet fully delineated, but possibilities include changes in food allergens, increasing aeroallergens and other environmental factors, the decrease of H. pyloriand early life exposures that may affect the microbiome. The study of the epidemiology of EoE has now shifted from case description to risk factor ascertainment, and new etiologic hypotheses have been raised that present exciting avenues for future epidemiologic and pathogenic research in this condition, with the ultimate goal of preventing the occurrence of EoE.

Key points.

EoE affects patients of all ages, is more commonly seen in males and Whites, and is strongly associated with atopy.

EoE is chronic, relapses are frequent after treatment is stopped, and diagnostic delay with persistent inflammation increases the risk of esophageal strictures and fibrostenotic complications.

The prevalence of EoE is 0.5–1 cases/1000 persons.

The incidence of EoE is approximately 10 cases/10,000 persons per year.

Elucidating the reasons for the rapid rise in incidence and prevalence of EoE is an active area of research, and possibilities include changes food allergens and aeroallergens, other environmental factors, the decrease of H. pyloriand early life exposures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH award number K23 DK090073.

Dr. Dellon has received research support from AstraZeneca, Meritage Pharma, Olympus, NIH, ACG, AGA, and CURED Foundation. Dr. Dellon is been a consultant for Aptalis, Novartis, Receptos, and Regeneron.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interested pertaining to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Landres RT, Kuster GG, Strum WB. Eosinophilic esophagitis in a patient with vigorous achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:1298–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attwood SE, Smyrk TC, Demeester TR, Jones JB. Esophageal eosinophilia with dysphagia. A distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF01296781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Bernoulli R, Loosli J, Vogtlin J. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis: a frequently overlooked disease with typical clinical aspects and discrete endoscopic findings. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1994;124:1419–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1503–1512. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–1206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assa'ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, Bucher KA, Beglinger C, Simon HU. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1660–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, Rao MS, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Schwimmer J, Bastian JF. Distinguishing eosinophilic esophagitis in pediatric patients: clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of an emerging disorder. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:252–256. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000212639.52359.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:30–36. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181788282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras C, Katzka DA. ACG Clinical Guideline: Evidence based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679–692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:940–941. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408263510924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straumann A, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:418–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Aro P, et al. Prevalence of oesophageal eosinophils and eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: The population-based Kalixanda study. Gut. 2007;56:615–620. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckmeier BK, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH. The incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(Suppl 2):S71. (AB 271). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, et al. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, et al. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: A 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1349–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.013. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Rhijn BD, Verheij J, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Rapidly increasing incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis in a large cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:47–52. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12009. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapel RC, Miller JK, Torres C, Aksoy S, Lash R, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a prevalent disease in the United States that affects all age groups. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1316–1321. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellon ES, Aderoju A, Woosley JT, Sandler RS, Shaheen NJ. Variability in diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2300–2313. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackenzie SH, Go M, Chadwick B, et al. Clinical trial: eosinophilic esophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia: a prospective analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1140–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veerappan GR, Perry JL, Duncan TJ, et al. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in an Adult Population Undergoing Upper Endoscopy: A Prospective Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franciosi JP, Tam V, Liacouras CA, Spergel JM. A case-control study of sociodemographic and geographic characteristics of 335 children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sperry SLW, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Influence of race and gender on the presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:215–221. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohm M, Malik Z, Sebastiano C, et al. Mucosal Eosinophilia: Prevalence and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Symptoms and Endoscopic Findings in Adults Over 10 Years in an Urban Hospital. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:567–574. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31823d3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma HP, Mansoor DK, Sprunger AC, et al. Racial disparities in the presentation of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:AB110. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Dias JA, Maydonovitch CL, Wong R. Race may play a role in the clinical presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1263. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, Bastian J, Aceves S. Oral Viscous Budesonide Is Effective in Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. 37 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, et al. Swallowed Fluticasone Improves Histologic but Not Symptomatic Responses of Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.018. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Assa'ad AH, Gupta SK, Collins MH, et al. An antibody against IL-5 reduces numbers of esophageal intraepithelial eosinophils in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1593–1604. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta SK, Collins MH, Lewis JD, Farber RH. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Budesonide Suspension (OBS) in Pediatric Subjects With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): Results From the Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled PEER Study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(Suppl 1):S179. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, et al. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129::456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.044. 63.e1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Clinical and immunopathologic effects of swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:568–575. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeBrosse CW, Franciosi JP, King EC, et al. Long-term outcomes in pediatric-onset esophageal eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menard-Katcher P, Marks KL, Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Yang YX, Falk GW. The natural history of eosinophilic oesophagitis in the transition from childhood to adulthood. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:114–121. doi: 10.1111/apt.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liacouras CA, Wenner WJ, Brown K, Ruchelli E. Primary eosinophilic esophagitis in children: successful treatment with oral corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26:380–385. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helou EF, Simonson J, Arora AS. 3-Yr-Follow-Up of Topical Corticosteroid Treatment for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2194–2199. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.017. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Liacouras CA. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:777–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prieto R, Richter JE. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: an update on medical management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:324. doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirano I. Therapeutic End Points in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Is Elimination of Esophageal Eosinophils Enough? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:750–752. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, Rybnicek DA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Straumann A. The natural history and complications of eosinophilic esophagitis. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim HP, Vance RB, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. The Prevalence and Diagnostic Utility of Endoscopic Features of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.019. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chehade M, Sampson HA, Morotti RA, Magid MS. Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:319–328. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31806ab384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1230–1236. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sealock RJ, Rendon G, El-Serag HB. Systematic review: the epidemiology of eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:712–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fujishiro H, Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Eosinophilic esophagitis investigated by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1142–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kinoshita Y, Furuta K, Ishimaura N, et al. Clinical characteristics of Japanese patients with eosinophilic esophagitis and eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J Gastroenterol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0640-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shi YN, Sun SJ, Xiong LS, Cao QH, Cui Y, Chen MH. Prevalence, clinical manifestations and endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis: a pathological review in China. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:304–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cherian S, Smith NM, Forbes DA. Rapidly increasing prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in Western Australia. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:1000–1004. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.100974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arias A, Lucendo AJ. Prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in adult patients in a central region of Spain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:208–212. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835a4c95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hasosah MY, Sukkar GA, Alsahafi AF, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in Saudi children: symptoms, histology and endoscopy results. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:119–123. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.77242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Foroutan M, Norouzi A, Molaei M, et al. Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients with Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:28–31. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0706-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujiwara Y, Sugawa T, Tanaka F, et al. A multicenter study on the prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis and PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilic infiltration. Intern Med. 2012;51:3235–3239. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gill R, Durst P, Rewalt M, Elitsur Y. Eosinophilic Esophagitis Disease in Children from West Virginia: A Review of the Last Decade (1995–2004) Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2281–2285. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dalby K, Nielsen RG, Kruse-Andersen S, et al. Eosinophilic Oesophagitis in Infants and Children in the Region of Southern Denmark: A Prospective Study of Prevalence and Clinical Presentation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:280–282. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d1b107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, et al. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300–306. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181eb5a9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ally M, Maydonovitch C, McAllister D, Betteridge J, Moawad F, Veerappan G. The prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States military healthcare population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(Suppl 1):S1. (AB 2). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Syed AA, Andrews CN, Shaffer E, Urbanski SJ, Beck P, Storr M. The rising incidence of eosinophilic oesophagitis is associated with increasing biopsy rates: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:950–958. doi: 10.1111/apt.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soon IS, Butzner JD, Kaplan GG, Debruyn JC. Incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:72–80. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318291fee2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rybnicek DA, Hathorn KE, Pfaff ER, Bulsiewicz WJ, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Administrative coding is specific, but not sensitive, for identifying eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esoph. 2013 Nov 12; doi: 10.1111/dote.12141. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sealock RJ, Kramer JR, Verstovsek G, et al. The prevalence of oesophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic oesophagitis: a prospective study in unselected patients presenting to endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:825–832. doi: 10.1111/apt.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joo MK, Park JJ, Kim SH, et al. Prevalence and endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with esophageal or upper gastrointestinal symptoms. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:296–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–1187. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prasad GA, Talley NJ, Romero Y, et al. Prevalence and Predictive Factors of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients Presenting With Dysphagia: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2627–2632. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ricker J, McNear S, Cassidy T, et al. Routine screening for eosinophilic esophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4:27–35. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10384172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristics do Not Reliably Differentiate PPI-Responsive Esophageal Eosinophilia and Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients Undergoing Upper Endoscopy: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1854–1860. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, Goldstein NS, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hurtado CW, Furuta GT, Kramer RE. Etiology of esophageal food impactions in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:43–46. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181e67072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kerlin P, Jones D, Remedios M, Campbell C. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults with food bolus obstruction of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:356–361. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225590.08825.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sperry SL, Crockett SD, Miller CB, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Esophageal foreign-body impactions: epidemiology, time trends, and the impact of the increasing prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:985–991. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodrigo S, Abboud G, Oh D, et al. High intraepithelial eosinophil counts in esophageal squamous epithelium are not specific for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:435–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sa CC, Kishi HS, Silva-Werneck AL, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with typical gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms refractory to proton pump inhibitor. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:557–561. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000400006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Poh CH, Gasiorowska A, Navarro-Rodriguez T, et al. Upper GI tract findings in patients with heartburn in whom proton pump inhibitor treatment failed versus those not receiving antireflux treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garcia-Compean D, Gonzalez Gonzalez JA, Marrufo Garcia CA, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: A prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Achem SR, Almansa C, Krishna M, et al. Oesophageal eosinophilic infiltration in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1194–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thakkar K, Chen L, Tatevian N, et al. Diagnostic yield of oesophagogastroduodenoscopy in children with abdominal pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:662–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04084.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hill CA, Ramakrishna J, Fracchia MS, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in children with refractory aerodigestive symptoms. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:903–906. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miller SM, Goldstein JL, Gerson LB. Cost-effectiveness model of endoscopic biopsy for eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with refractory GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1439–1445. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kidambi T, Toto E, Ho N, Taft T, Hirano I. Temporal trends in the relative prevalence of dysphagia etiologies from 1999–2009. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335–4341. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bonis PA. Putting the puzzle together: epidemiological and clinical clues in the etiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vanderheyden AD, Petras RE, DeYoung BR, Mitros FA. Emerging eosinophilic (allergic) esophagitis: increased incidence or increased recognition? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:777–779. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-777-EEAEII. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Woosley JT, Rubinas TC, Shaheen NJ. Increasing incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: A persistent trend after accounting for procedure indication and biopsy rate. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(Suppl 1):S1972. (A289) [Google Scholar]

- 93.DeBrosse CW, Collins MH, Buckmeier Butz BK, et al. Identification, epidemiology, and chronicity of pediatric esophageal eosinophilia, 1982–1999. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Whitney-Miller CL, Katzka D, Furth EE. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a retrospective review of esophageal biopsy specimens from 1992 to 2004 at an adult academic medical center. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:788–792. doi: 10.1309/AJCPOMPXJFP7EB4P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Garrean CP, Gonsalves N, Hirano I. Epidemiologic implications of symptom onset in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(Suppl 1):AB S1875. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The 'hygiene hypothesis' for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wolf WA, Jerath MR, Dellon ES. De-novo onset of eosinophilic esophagitis after large volume allergen exposures. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22:205–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fogg MI, Ruchelli E, Spergel JM. Pollen and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:796–797. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Lake JM, et al. Correlation between eosinophilic oesophagitis and aeroallergens. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Almansa C, Krishna M, Buchner AM, et al. Seasonal distribution in newly diagnosed cases of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:828–833. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang FY, Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF. Is there a seasonal variation in the incidence or intensity of allergic eosinophilic esophagitis in newly diagnosed children? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:451–453. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000248019.16139.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hurrell JM, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia varies by climate zone in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:698–706. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jensen ET, Hoffman K, Shaheen NJ, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis are increased in rural areas with low population density: Results from a national pathology database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(Suppl 1):S8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.47. (Ab 22) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Elitsur Y, Aswani R, Lund V, Dementieva Y. Seasonal distribution and eosinophilic esophagitis: the experience in children living in rural communities. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:287–288. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826df861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Peterson KA, Byrne KR, Vinson LA, et al. Elemental diet induces histologic response in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:759–766. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination Diet Effectively Treats Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults; Food Reintroduction Identifies Causative Factors. Gastroenterology. 2012;142 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal disease: wake-up call? Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1819–1822. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dellon ES, Peery AF, Shaheen NJ, et al. Inverse association of esophageal eosinophilia with Helicobacter pylori based on analysis of a US pathology database. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1586–1592. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Furuta K, Adachi K, Aimi M, et al. Case-control study of association of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders with Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2013;53:60–62. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.13-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Helicobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:821–827. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hassall E. Over-prescription of acid-suppressing medications in infants: how it came about, why it's wrong, and what to do about it. J Pediatr. 2012;160:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Merwat SN, Spechler SJ. Might the use of acid-suppressive medications predispose to the development of eosinophilic esophagitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1897–1902. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kedika RR, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Potential anti-inflammatory effects of proton pump inhibitors: a review and discussion of the clinical implications. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2312–2317. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0951-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mullin JM, Valenzano MC, Whitby M, et al. Esomeprazole induces upper gastrointestinal tract transmucosal permeability increase. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1317–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Untersmayr E, Bakos N, Scholl I, et al. Anti-ulcer drugs promote IgE formation toward dietary antigens in adult patients. FASEB J. 2005;19:656–658. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3170fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Untersmayr E, Scholl I, Swoboda I, et al. Antacid medication inhibits digestion of dietary proteins and causes food allergy: a fish allergy model in BALB/c mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:616–623. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01719-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cheng E, Zhang X, Huo X, et al. Omeprazole blocks eotaxin-3 expression by oesophageal squamous cells from patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis and GORD. Gut. 2013;62:824–832. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Molina-Infante J, Ferrando-Lamana L, Ripoll C, et al. Esophageal Eosinophilic Infiltration Responds to Proton Pump Inhibition in Most Adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Molina-Infante J, Katzka DA, Gisbert JP. Review article: proton pump inhibitor therapy for suspected eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:1157–1164. doi: 10.1111/apt.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hviid A, Svanstrom H, Frisch M. Antibiotic use and inflammatory bowel diseases in childhood. Gut. 2011;60:49–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.219683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Marra F, Lynd L, Coombes M, et al. Does antibiotic exposure during infancy lead to development of asthma?: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2006;129:610–618. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wang JY, Liu LF, Chen CY, Huang YW, Hsiung CA, Tsai HJ. Acetaminophen and/or antibiotic use in early life and the development of childhood allergic diseases. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1087–1099. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jensen ET, Kappelman MD, Kim HP, Ringel-Kulka T, Dellon ES. Early Life Exposures as Risk Factors Forpediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Pilot and Feasibility Study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:67–71. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318290d15a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Brown EM, Arrieta MC, Finlay BB. A fresh look at the hygiene hypothesis: How intestinal microbial exposure drives immune effector responses in atopic disease. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fillon SA, Harris JK, Wagner BD, et al. Novel device to sample the esophageal microbiome-the esophageal string test. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Abonia JP, Wen T, Stucke EM, et al. High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD, Dellon ES. High prevalence of coexisting autoimmune conditions among patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2013:S491. (Su1852). [Google Scholar]