Abstract

Background

Neurological dysfunction causes fecal incontinence, but current techniques for its assessment are limited and controversial.

Objective

To investigate spino-rectal and spino-anal motor evoked potentials simultaneously using lumbar and sacral magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence and healthy subjects, and to compare motor evoked potentials and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency in fecal incontinence subjects.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Settings

Two Tertiary Care Centers.

Patients

Adult fecal incontinence and healthy subjects.

Interventions

Translumbar and transsacral magnetic stimulations performed bilaterally by applying a magnetic coil to the lumbar and sacral regions in 50 fecal incontinence (≥ 1 episode/week) and 20 healthy subjects. Both motor evoked potentials and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency were assessed in 30 fecal incontinence patients. Stimulation-induced motor evoked potentials were recorded simultaneously from rectum and anus with two pairs of bipolar ring electrodes.

Main Outcome Measurements

Latency and amplitude of motor evoked potentials after lumbosacral magnetic stimulation and agreement with pudendal nerve terminal motor latency.

Results

When compared to controls, one or more lumbo-anal, lumbo-rectal, sacro-anal, or sacro-rectal motor evoked potentials were significantly prolonged (p<0.01) and were abnormal in 44/50 (88%) fecal incontinence subjects. Positive agreement between abnormal motor evoked potentials and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency was 63% whereas negative agreement was 13%. motor evoked potentials were abnormal in more (p <0.05) fecal incontinence patients than pudendal nerve terminal motor latency, 26/30 (87%) versus 19/30 (63%) respectively, and in 24% of patients with normal pudendal nerve terminal motor latency. No adverse events.

Limitations

Anal electromyography was not performed.

Conclusions

Translumbar and transsacral magnetic stimulation–induced motor evoked potentials provide objective evidence for rectal or anal neuropathy in fecal incontinence patients and could be useful. Test was superior to pudendal nerve terminal motor latency and appears to be safe and well tolerated.

Keywords: fecal incontinence, spino-anorectal pathway, neurophysiologic test, motor evoked potentials

INTRODUCTION

Fecal incontinence (FI) affects 2.2–15 %1 of the western population with a higher prevalence in older subjects.1,2 Its pathophysiology involves multiple and often overlapping mechanisms such as anorectal neuropathy, and weak or damaged anal sphincters.3

Obstetric, pelvic floor and spinal cord injury may each cause fecal incontinence either due to muscle or neurological injury or both in a majority of FI patients.1,4,5 Currently, anorectal neurological injury is assessed by performing anal electromyography or the pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML),6,7 and only in specialized centers.

Electromyography (EMG) quantifies the electrical activity of anal sphincter and is performed with either single fiber or concentric needle or surface plug EMG.8,9 Needle EMG although superior to surface EMG10 is painful, may require multiple insertions and not well tolerated. PNTML provides a compound muscle action potential and assessment of nerve conduction through the terminal portion of the pudendal nerve. It has several limitations including the fact that a normal latency time does not exclude neuropathy and its clinical utility remains controversial 5, 11–14. Furthermore, neither EMG nor PNTML evaluates the entire spino-anorectal neuronal pathways. Consequently, a standardized and objective test for a comprehensive evaluation of neuropathy is lacking.

Recently, magnetic stimulation based on Faraday’s principle of electro-magnetic induction 15,16 has been proposed.17,18 Transcranial magnetic stimulation can reliably evoke motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) in the rectum and esophagus. Recently, we showed that MEPs provide a useful assessment of anorectal neuropathy in patients with spinal cord injury19. Although previous investigators have used translumbar magnetic stimulation to study cauda equina and pudendal nerve lesions in subjects with FI, 20,21 simultaneous evaluation of anal and rectal MEPs, and at lumbar and sacral regions has not been performed. Such a comprehensive assessment is needed because the anorectum has complex and diverse neurological innervation and neuropathy may affect only some of the neuronal tracts.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that magnetic stimulation-induced anal and rectal MEPs are prolonged in subjects with FI compared to healthy controls. Our aims were; (i) to prospectively evaluate and compare anal and rectal MEPs following bilateral translumbar and transsacral magnetic stimulation in patients with FI, and healthy controls and (ii) to assess the diagnostic yield of translumbar and transsacral MEPs in subjects with FI and when compared to PNTML.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subjects with FI (≥1/week, formed or liquid stool) and no previous history of back injury, spinal surgery or neurological disease were recruited at two centers. All subjects filled out the Vaizey FI severity score22 that assesses incontinence of solid, liquid and gas and how the FI alters quality of life. Also it includes the need to wear a pad, use of constipation medicine and inability to defer defecation for more than 15 min. Possible score ranges from 0 to 24. Healthy subjects were screened and those without previous surgery or medication use, except multivitamins, oral contraceptives or aspirin, and normal physical examination were recruited. Study was approved by IRBs, at University of Iowa and Georgia Regents University.

Each subject underwent two tests in a random order at thirty minute intervals. Randomization was computer generated and was only available at the time the patient was ready for examination. The tests comprised of bilateral spino-anal and spino-rectal MEP assessment, using translumbar and transsacral magnetic stimulation and anorectal manometry23. Additionally, a cohort of subjects both healthy controls and FI patients underwent the PNTML test. All subjects did not undergo the PNTML test because we encountered technical problems with the PNTML equipment and some subjects refused to participate.

Translumbar/Transsacral Magnetic Stimulation

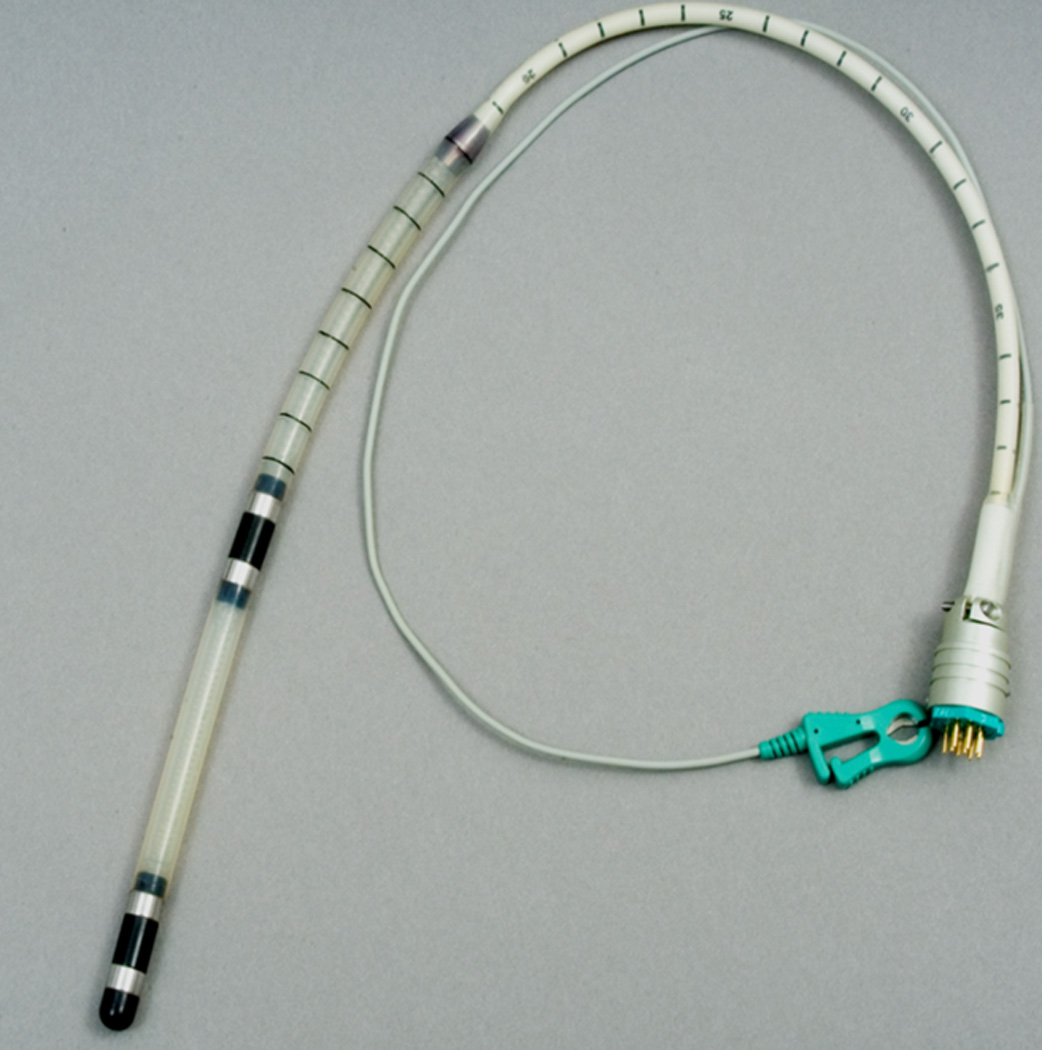

With the subject lying in left lateral position, a probe (Konigsberg Instruments, Pasadena, CA) containing 2 pairs of bipolar steel ring electrodes (Figure 1) was placed such that one pair was located in the rectum at 7–9 cm, and second pair in the anal canal at 2–3 cm from anal verge. Probe was kept in place using 3M tegaderm film that was located over the probe close to the anal verge. The spinal magnetic stimulations were performed either by using a Cadwell Focalpoint Coil (9 cm; Cadwell, San Diego, CA) or a figure of 8 magnetic coil (9 cm Digistim (Magstim Ltd, Boston, MA) in prone position (Figure 1). These two coils were of similar size and provided focal stimulation. Although 2 different coils and devices were used, stimulations were performed using identical stimulation frequency and intensity. Variability if any with these devices is estimated to be negligible.

Figure 1.

This picture shows the anorectal probe that contains 2 pairs of ring electrodes, when correctly positioned, the rectal rings were located 7–9 cms from the anal verge and anal rings located 2–3 cms from the anal verge.

The translumbar MEPs were evoked on each side at the L3 – L4 level, approximately 3 cm lateral to the midline and the transsacral MEP at the S3–S4 level, 3 cm lateral to the midline and on each side (Figure 2). These sites were chosen based on our pilot studies and previous studies.24, 25 We used between 50 – 100 % intensity (2 T) of magnetic stimulation to evoke MEPs, usually starting at 50 % intensity and in 5–10% increments until an optimal and reproducible MEP response (>10 µv) was obtained. At least five optimal responses were obtained at each site, and the three best responses were averaged to calculate the MEP responses. After magnetic stimulation, the MEP responses were recorded simultaneously from the rectum and the anal canal, and were displayed on a monitor (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

This cartoon displays the equipment and sites used for the bilateral translumbar and transsacral magnetic stimulation. The magnetic stimulation induces signals within the targeted nerve roots, which then passes onto the nerves innervating the rectum and anus where the motor evoked potentials can be registered by the probe. The computer is used to display the record and analyze the data.

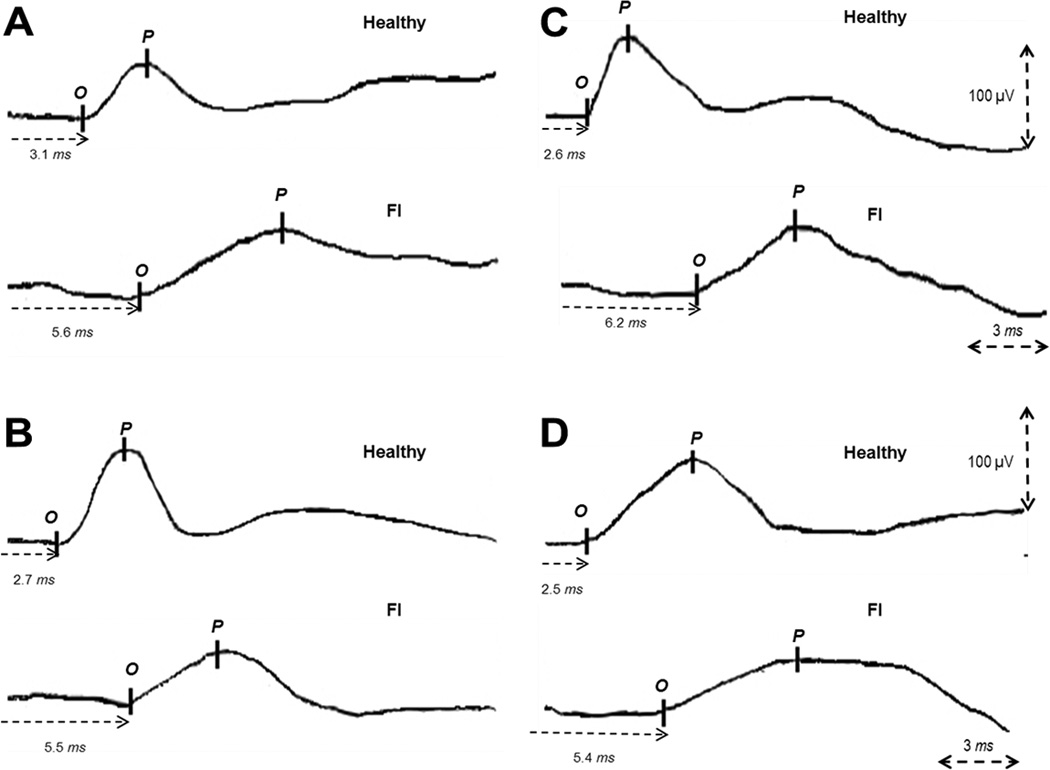

The lumbar and sacral MEPs were designated as follows: translumbar-rectal MEP, translumbar-anal MEP, transsacral-rectal MEP, and transsacral-anal MEP, respectively. Because responses were obtained bilaterally, a total of eight MEP responses (four from each side) were recorded. Each MEP response was analyzed to determine onset time (O) in milliseconds (latency) and the peak (P). (Figure 2) The amplitude of MEP response was measured as the voltage difference (µV) between O and P. Additionally, to detect any differences between the lumbar and sacral site, peripheral motor latency (PML) were calculated as the mean difference (delta Δ, ms) between the lumbar and sacral MEP responses.

Anorectal Manometry and rectal sensory assessment

Anorectal manometry was performed by placing a 6 sensor solid-state probe (Koningsberg laboratories, Pasadena, CA) with a balloon into the anorectum. Our methods have been described previously23. We measured anal sphincter pressures during rest, squeeze, and when bearing down. Rectal sensation was assessed by performing intermittent balloon distension with air starting with 10 cc and up to 320 cc. Each inflation was maintained for 1 minute. The sensory thresholds for first sensation, desire to defecate, and urge to defecate and the maximum tolerable volume were recorded23.

Pudendal Nerve Terminal Motor Latency (PNTML)

PNTML was measured by using the St. Mark’s disposable electrode (Dantec Electronics, Bristol, UK). The pudendal nerve was stimulated on each side, transanally at the ischial spine23. The mean onset time of the three best responses was taken as the motor latency on each side23.

Statistical Analyses

The MEPs and PNTML data are presented as median (5th–95th percentile) values. The anal sphincter pressures and manometric data are presented as mean ± SD. The presence of anal or rectal neuropathy was defined as prolonged onset of MEP latency using the following cutoff s that were > 2 s.d. of the mean values obtained in healthy controls: >4.0 ms for translumbar-rectal MEP, > 4.2 for translumbar-anal MEP, > 4.1 for transsacral-rectal MEP, and > 4.5 for transsacral-anal MEP; and for PNTML, an onset time of > 2.2 ms26. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The primary comparisons between the FI patients and healthy controls were the MEP data. Additional comparisons were made between the MEP responses and the PNTML responses in FI patients and in healthy subjects by using Mann-Whitney U-test. Differences in the prevalence of abnormal test between MEP or PNTML test were compared by using X2. The mean differences for the anal sphincter pressures, and for the rectal sensory thresholds and for the balloon expulsion tests between the two groups were compared using Student’s t-test. Incontinent subjects were considered to have rectal hypersensitivity when two or more of the three rectal sensory threshold volumes (first sensation, desire to defecate, urgency to defecate) were lower than 2 S.D. of the normal mean value, and rectal hyposensitivity when rectal sensory thresholds were higher than 2 s.d. of the normal mean values23, 27.

RESULTS

Subjects

Fifty patients with FI, F/M = 42/8, mean age 61(31–87) years, and 20 healthy subjects (F/M = 10/10, mean age 40 (21–59) years (p= 0.001) were enrolled. Also, 34/50 FI patients (F/M = 31/3, mean age 62±12 years) and 15/20 (F/M = 9/6) healthy controls underwent the PNTML test. Four out of 34 patients were excluded from the comparative analysis because of technical failure to obtain PNTML in (3 patients), and MEPs (1 patient).

Demographics/Baseline Anorectal function tests

Seven patients (14 %) had diabetes mellitus and 8 (16%) had previous anorectal or transperineal surgery, and 4/42 were nulliparous. The median number of pregnancies in the multiparous women was 3 (range 2–10) while the median number of pregnancies in HC was 1 (range 1–4) (p= 0.0001). All FI patients had vaginal delivery, and twelve reported a history of difficult labor (large baby, instrumentation, or breech). All HC had vaginal deliveries, and 2 also had C-section. There were 5 HC that reported vaginal tears and 2 had difficult labor that required using forceps. Thirty six patients had urge incontinence, 9 had passive incontinence and 5 had fecal seepage. The mean Vaizey score (0–24) was 15 (range 4–22). There were 28 patients with leakage of solid stools, 36 liquid stools and 34 with gas incontinence. Majority of patients had a mixed pattern of incontinence with significant overlap. The median number of FI episodes/week was 1. Ten (20%) had coexisting urinary incontinence.

The results of anorectal manometry and rectal sensation are shown in table 3. Resting and squeeze sphincter pressures and squeeze duration were significantly decreased (p <0.05) in FI patients compared to healthy controls. Thresholds for first sensation, desire to defecate and urge to defecate and maximal tolerable volume were significantly lower (p<0.05) in FI patients compared to controls. Nineteen patients (38%) had normal rectal sensation, 10 (20%) had rectal hyposensitivity and 21 (42%) had rectal hypersensitivity. A dyssynergic pattern was seen in 34 (68%) patients during attempted defecation.

Table 3.

Anorectal manometric profiles in subjects with fecal incontinence and healthy controls

| Subjects with fecal incontinence |

Normative data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Males (mean, 95% CI) |

Female (mean, 95% CI) |

||

| Resting sphincter pressure (mmHg) | 36 (13–80) | 72 (64–80) | 65 (56–74) |

| Maximal squeeze pressure (mmHg) | 90 (24–194) | 193 (175–211) | 143 (124–162) |

| Sustained squeeze pressure (mmHg) | 56 (15–127) | 176 (156–196) | 120 (104–136) |

| Duration of squeeze (sec) | 21 (0–60) | 32 (26–38) | 24 (20–38) |

| Sphincter length (cm) | 2.5 (1.0–3.5) | 4 (3.8–4.2) | 3.6 (3.4–3.8) |

| Volume infused at onset of first leak (ml) | 100 (15–400) | 772 (736–806) | 5.1 (414–648) |

| Total volume retained (ml) | 182 (0–500) | 788 (768–808) | 688 (623–753) |

| First sensation (ml) | 20 (10–60) | 20 (15–25) | 19 (15–23) |

| Desire to defecate (ml) | 73 (20–150) | 109 (85–134) | 103 (83–123) |

| Urge to defecate (ml) | 108 (40–300) | 185 (152–218) | 173 (150–196) |

| Maximal tolerable volume (ml) | 160 (40 – 290) | 249 (223–275) | 230 (205–255) |

Values are expressed as mean (95% CI)

Translumbar/ transsacral motor evoked potentials (TL-MEP, TS-MEP)

Eight individual MEP responses were obtained. Figure 2 shows typical profiles of the MEP response in a healthy control and a patient with FI.

The mean latencies for the MEP responses are shown in table 1. Overall, subjects with FI had significantly prolonged MEP latencies when compared to healthy subjects (p<0.01). Only 6 FI subjects had normal MEP responses at all sites. Patients with normal MEPs reported a Vaizey incontinence score of 15.8 (range 4–22) and there were no differences in this scope when compared to those with prolonged MEPs.

Table 1.

Latencies of motor evoked potentials after translumbar/transsacral magnetic stimulation and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency test.

| Left Latencies (ms) | Right Latencies (ms) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incontinence n= 48 |

Controls n=20 |

p | Incontinence n=48 |

Controls n=20 |

p | |

| TL-rMEP (msec) | 3.9 (3.5–4.2) | 2.8(2.6–3.1) | 0.001 | 4.5(3.9–5) | 2.6 (2.3–3.5) | 0.0001 |

| TS-rMEP (msec) | 4.4(4–4.8) | 2.7(2.3–3.1) | 0.0001 | 3.8(3.5–4.2) | 2.5 (2.1–2.9) | 0.009 |

| TL-aMEP (msec) | 5.7 (3–6.4) | 3.1(2.5–3.6) | 0.0001 | 5.6 (4.9–6.2) | 3 (2.6–3.5) | 0.0001 |

| TS-aMEP (msec) | 4.9(2.6–8.5) | 2.9(2.5–3.4) | 0.0001 | 4.9 (4.5–5.4) | 2.9 (2.5–3.3) | 0.0001 |

| PNTML (msec) | 2.4(1.7–8.3) | 1.7(1.5–2.8) | 0.001 | 2.1(1.5–3.6) | 1.8 (1.2–2.7) | 0.01 |

TL-rMEP: trans-lumbar rectal motor evoked potential, TL-aMEP: trans-lumbar anal motor evoked potential, TS-rMEP: trans-sacral rectal motor evoked potential, TS-aMEP; trans-sacral anal motor evoked potential; (PNTML) pudendal nerve terminal motor latency. Test Values are expressed as mean (95% CI); significance p<0.05

Abnormal MEP responses were seen at all sites, and on both sides in FI patients (table 2). The prevalence of abnormal MEPs for the left side ranged between 46–68%, and for the right side between 32–62%. The peripheral motor latencies were slightly shorter for the transsacral MEPs when compared to the translumbar MEPs at both the rectal (0.11 ms ± 0.03 SEM for translumbar and 0.13 ms ± 0.05 SEM for transsacral) and anal (0.19 ms ± 0.03 SEM for translumbar and 0.16 ms ± 0.06 SEM for transsacral) sites (table 1), but not significant (p>0.05). There were not differences in MEPs after comparing patients according with history of anal surgery, parity, diagnosis of diabetes and severity of FI according to Vaizey score.

Table 2.

Number (percentage) of abnormal MEPs after translumbar/transsacral magnetic stimulation per stimulation site

| Left n=50 (%) | Right n=50 (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Abnormal | Normal | Abnormal | |

| TL-rMEP | 27 (54) | 23 (46) | 20 (40) | 30 (60) |

| TL-aMEP | 17 (34) | 33 (66) | 29 (38) | 31 (62) |

| TS-rMEP | 25 (50) | 25 (50) | 34 (68) | 16 (32) |

| TS-aMEP | 16 (32) | 34 (68) | 30 (60) | 20 (40) |

Abnormal MEPs were partially associated with the type of incontinence. They were significantly shorter in urge type of incontinence when compared to passive incontinence and seepage types, but only at 2 of the 8 recording sites (TL anal right p=0.048 and TS rectal left, p=0.035). All the other sites showed no significant differences.

Pudendal Nerve Terminal Latency

Patients with fecal incontinence had significantly prolonged PNTML, when compared to healthy subjects (p<0.05). (Table 1) Eleven patients had normal PNTML on both sides, and 19 had abnormal PNTML of whom 12 were abnormal on one side, and 7 on both sides.

Diagnostic yield and agreement of spino-anorectal MEPs and PNTML

An abnormal MEP response was seen at one or more of the eight stimulation sites in 44/50 (88%) patients; 6 had normal MEPs.

Thirty FI patients underwent both MEP and PNTML tests. MEPs were prolonged at one or more sites in 26 (87%) FI patients whereas PNTML was prolonged at one or both sides in 19 (63%) FI patients (p<0.01). A positive device agreement for the detection of neuropathy between MEP and PNTML was seen in 19/30 (63%) FI patients. In 4/30 FI patients (13%) both MEP and PNTML were normal indicating negative device agreement (neuropathy excluded). In the remaining 7/30 (24%) FI patients, PNTMLs were normal on both sides whereas the MEPs were abnormal and prolonged indicating neuropathy. Overall, device agreement between MEP and PNTML was seen in 23/30 (77%) patients. These data suggest that the MEP test could provide a higher diagnostic yield for detection of neuropathy when compared to PNTML. Overall, 72% of patients had concordance in TL and TS MEPs at both rectal and anal sites. These results suggest that an abnormal TL rectal MEP is most likely accredited with abnormal TS rectal MEP. Although some of concordance was present for both TL and TS sites, 88% of patient had at least one or more abnormal MEPs and only 44% had concordance for abnormal MEPs at all sites of stimulation.

Tolerance/Adverse events

Almost all patients reported mild to moderate anorectal discomfort during PNTML, largely related to digital-rectal examination and 2 subjects reported severe discomfort. 4/50 patients reported mild transient anorectal discomfort during MEP probe placement and 3/50 patients reported mild, transient lumbar discomfort from magnetic stimulation that resolved immediately.

DISCUSSION

Neuropathic injury to the pelvic floor can cause FI.1,2,4,19 Also, women with sphincter defects are more likely to develop incontinence if they have neuropathy.28 However, since the development of single fiber needle, surface or concentric needle EMG and PNTML, nearly three decades ago there has been little progress in our ability to investigate possible neuropathy of the pelvic floor.29,30

EMG and PNTML have significant limitations that have prevented widespread acceptance or usage. Needle EMG is painful. Likewise, PNTML involves digital rectal examination that is uncomfortable to the patient and operator and has other limitations.31 Neither test provides an assessment of all the peripheral nerves that innervate anorectum. Finally, a lack of objective and comprehensive evaluation of the peripheral spino-rectal and spino-anal pathways has stifled our understanding of the neurogenic basis of FI.

In this study, we found that the translumbar and the transsacral MEPs were significantly prolonged in patients with moderately-severe FI when compared to healthy controls. This finding suggests that the spino-anal and spino-rectal nerve conduction is abnormal, and indicative of a neuropathy that affects the rectum and anal sphincters, and would play an important role in the pathogenesis of FI. The presence of an underlying neuropathy in a significant proportion of these FI patients is not surprising because they were evaluated in a specialist clinic with long-standing FI. Our findings explain one pathophysiological component but not the complete etiology for FI.

The sacral magnetic stimulation most likely stimulates the sacral nerve roots that supply the pelvic floor muscles including the pudendal nerve (S2, S3, S4) whose branches innervate external anal sphincter.7 The lumbar stimulation at the L3–L4 level, was chosen based on previous work by Swash and Snooks32, as it represented the origin of cauda equina and conduction through the S3 and S4 motor roots. Because they used a technique of wire-guided electrical stimulation, they could not stimulate at a more caudal level32 whereas with the magnetic coil we could evoke MEPs both at the lumbar and sacral levels. The ability to analyze four different MEP pathways not only provides a more accurate assessment of the spino-anorectal pathway, but could also help to grade the severity of neuropathy.

However, the magnetic field that is created by our coil may not only stimulate the sacral nerve roots but also the nerves in the lumbar plexus. Furthermore, we observed small but distinct differences in the peripheral motor latencies which represent the conduction velocity between the nerves emanating from the translumbar region and those from the transsacral region. Although these differences were not significant (possibly due to a type II error), they offer some evidence that stimulation at different locations along the nerve-roots provides additional information regarding the overall integrity of neuronal innervation. This is particularly important because we found that 44/50 FI subjects (88%) had abnormal MEPs from some but not all of the eight spino-anorectal sites that were assessed whereas at any one level or site it ranged from 32–68%. Furthermore, because neural innervation can be asymmetric, it is important to study the multiple pathways so as to provide comprehensive assessment.

Interestingly, there were some differences between the degree of neuropathy and type of FI. We found that patients with urge type FI had values that were prolonged when compared to healthy controls, but were shorter when compared to the passive and seepage types of FI at two out of the 8 recording sites (TL anal and TS rectal MEPs). These results suggest that the degree of neurological injury may be higher in passive and seepage subtypes but merits further study.

Magnetic stimulation studies have been performed previously to assess neuropathy at different locations in the spine, including the cervical33 and lumbosacral regions and can detect neuropathy associated with spinal abnormalities (cauda equina, lumbar stenosis). However, these studies were mostly exploratory, not hypothesis driven and were performed in either healthy subjects only23,29,30,34,35 or females only35 or males only,29 or after stimulation at iliac crest.29,30 There are limited and only anecdotal studies of MEPs in subjects with FI17,21 and the data are contradictory; possibly hampered by technical issues, including the use of anal surface EMG (a technique that is prone to artifacts), lack of simultaneous assessment of rectal and anal MEPs or isolated evaluations from only the lumbar or sacral regions. These shortcomings were overcome by performing MEP recordings using a specially designed probe that provided better contact and minimized artifact. Our technique has been validated, shows good reproducibility, and has facilitated the detection of neuropathy in patients with spinal cord injury.19

We found that the PNTML was abnormally prolonged in 63% while the MEPs were abnormal in 87% of FI subjects. This finding further reaffirms the limitation of PNTML that it does not detect neuropathy in all FI subjects, in part because the neuropathy may involve and extend beyond the terminal portion of the pudendal nerve and that PNTML currently measures conduction of fastest conducting and intact nerves only but not the entire innervation of the anorectum. These factors may explain the detection of neuropathy with MEPs in 24% of subjects with a normal PNTML. Although PNTML has been used for several decades, results have been contradictory and are not endorsed by many experts including AGA5.

The MEP test was generally well-tolerated with no adverse events. Based on our experience with the PNTML for over 20 years and the MEPs for over 5 years, we believe that the MEPs are technically less demanding, easier to perform and better tolerated than PNTML. Also the probe is flexible, causes minimal discomfort and stays in place, unlike digital manipulations. Furthermore, it is an objective assessment and, removes any bias or room for misinterpretation of a shorter latency time and minimizes the interobserver error.

The detection of neuropathy provides mechanistic information regarding the pathophysiology of incontinence but its clinical significance particularly with regards to therapeutic interventions is unclear. Recently, contradictory reports have been published regarding the usefulness and outcome of sacral nerve stimulation for FI.36,37 This in part could be due to the heterogeneity of the FI population, or device-related issues or the presence or absence of pelvic neuropathy. For example, it is possible that patients with significant anorectal neuropathy are less likely to respond to sacral nerve stimulation and this hypothesis needs further testing.

The limitations of our study include the inability to perform MEPs in subjects with metal implants or multiple spinal surgeries. Also EMG studies were not performed to independently verify neuropathy. There were significant age differences between FI patients and controls, and whether aging has an independent effect on pelvic floor nerve conduction is not known and merits further study. Also, in females, the number of vaginal deliveries differed significantly between controls and FI patients. Whether more number of deliveries cause greater neurological injury is not known, and also deserves further study. Finally, because we examined patients who were referred to a tertiary care center, our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with FI.

In conclusion, translumbar and transsacral magnetic neuro-stimulation appears to be a useful technique for the detection of neuropathy, and provides a new dimension towards our understanding of the mechanisms of FI. The test is safe and well-tolerated and provides both objective and comprehensive information regarding the presence or absence of anal or rectal neuropathy in patients with fecal incontinence.

Figure 3.

The left panel shows, typical examples of translumbar-rectal (A) and translumbar-anal (B) MEP responses in a healthy subject and in a patient with fecal incontinence (FI). The right panel shows, typical examples of transsacral-rectal (C) and transsacral-anal (D) MEP responses in a healthy subject and in a patient with fecal incontinence.

Acknowledgement

Dr. SSC Rao was supported by NIH grant No. 2R01 KD57100-05A2. Dr. Kasaya Tantiphlachiva was supported by research fellowship grant from Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. Dr Remes-Troche was supported by Jon Isenberg AGA Research award. We sincerely thank Dr. Thoru Yamada for his advice and support with this project and Jessica Valestin, Carrie Phillips and Annie Dewitt for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the ACG annual meeting, in Philadelphia and published as an abstract, Am J Gastro 2007;102(s2):S426-58.

Conflict of Interest: None

Guarantor: Satish SC Rao, MD, PhD, FRCP, FACG – Study design, study performance and interpretation, study recruitment, data analysis, manuscript writing and overall preparation, critical revision, important intellectual content and final approval.

Contributing authors:

Jose Remes-Troche: study design and studies in normal subjects.

Enrique Coss-Adame, MD: data entry, data analysis, manuscript writing and statistical analysis.

Ashok Attaluri, MD: Statistical analysis, data analysis and study recruitment and assistance with studies

Kasaya Tantiphlachiva: study performance, data entry and analysis, manuscript writing.

References

- 1.Bharucha AE. Fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1672–1685. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson RL. Epidemiology of fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:S3–S7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao SS. Pathophysiology of adult fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:S14–S22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao SSC. Diagnosis and management of fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1585–1604. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamant NE, Kamm MA, Wald A, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:735–760. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen AL, Rao SS. Clinical neurophysiology and electrodiagnostic testing of the pelvic floor. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:33–54. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Percy JP, Swash M, Neill ME, Parks AG. Electrophysiological study of motor nerve supply of pelvic floor. Lancet. 1980;3:16–17. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remes-Troche JM, Rao SS. Neurophysiological testing in anorectal disorders. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;2:323–335. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daube JR, Traue J, Litchy W, et al. Anal sphincter motor unit potential (MUP) differences between sides, between rest and voluntary contraction, and between MUP analysis programs in normal subjects. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;60:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s1567-424x(08)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisner A, Jost WH. EMG of the external anal sphincter: needle is superior to surface electrode. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:116–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02237259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao SS, Ozturk R, Stessman M. Investigation of the pathophysiology of fecal seepage. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2204–2209. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilliland R, Altomare DR, Moreira H, Jr, Oliveira L, Gillilan JE, Wexner SD. Pudendal neuropathy is predictive of failure following anterior overlapping sphincteroplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1516–1522. doi: 10.1007/BF02237299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bharucha AE. Outcome measures for fecal incontinence: anorectal structure and function. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:S90–S98. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasgow SC, Birnbaum EH, Kodner IJ, Fleshman JW, Dietz DW. Preoperative anal manometry predicts continence after perineal proctectomy for rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1052–1058. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0538-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polsson MJR, Barker AT. Stimulation of nerve trunks with time-varying magnetic fields. Med & Biol Eng & Comput. 1982;20:243–244. doi: 10.1007/BF02441362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker AT, Jalinous R. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex. Lancet. 1985;11:1106–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herdmann J, Bielefeldt K, Enck P. Quantification of motor pathways to the pelvic floor in humans. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:G720–G723. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.5.G720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamdy H, Enck P, Aziz Q, et al. Spinal and pudendal nerve modulation of human corticoanal motor pathways. Am J Physiol. 1998;74:G419–G423. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.2.G419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tantiphlachiva K, Attaluri A, Valestin J, et al. Translumbar and Transsacral motor-evoked potentials: A novel test for spino-anorectal neuropathy in spinal cord injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:907–914-914. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shafik A. Magnetic pudendal neurostimulation: a novel method for measuring pudendal nerve terminal motor latency. Clinical Neurophyiology. 2001;112:1049–1052. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morren GL, Walter S, Lindehammar H, Hallbook O, Sjodahl R. Evaluation of the sacroanal motor pathway by magnetic and electric stimulation in patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:167–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02234288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaizey C, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao SSC, Hatfield R, Soffer E, Rao S, Beaty J, Conklin JL. Manometric tests of anorectal function in healthy adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:773–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelliccioni G, Scarpino O, Piloni V. Motor evoked potentials recorded from external anal sphincter by cortical and lumbo-sacral magnetic stimulation: normative data. J Neurol Sci. 1997;149:69–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)05388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morren GL, Walter S, Lindehammar H, et al. Evaluation of the sacroanal motor pathway by magnetic and electric stimulation in patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:167–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02234288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remes-Troche JM, Paulson J, Yamada T, et al. Combined transcranial, translumbar & transsacral magnetic stimulation: novel technique of assessing brain-gut axis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:436 (A52). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gladman MA, Dvorkin LS, Lunniss PJ, et al. Rectal hyposensitivity: a disorder of the rectal wall or the afferent pathway? An assessment using the barostat. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:106–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tetzschner T, Sorensen M, Lose G, Christiansen J. Anal and urinary incontinence in women with obstetric anal sphincter rupture. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:1034–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opsomer RJ, Caramia MD, Zarola F, Rossini PM. Neurophysiological evaluation of central-peripheral sensory and motor pudendal fibers. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1989;74:260–270. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(89)90056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loening-Baucke V, Read NW, Yamada T, Barker AT. Evaluation of the motor and sensory components of the pudendal nerve. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;93:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(94)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lefaucheur JP. Neurophysiological testing in anorectal disorders. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:324–333. doi: 10.1002/mus.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swash M, Snooks SJ. Slowed motor conduction in lumbosacral nerve root in cauda equina lesions: a new diagnostic technique. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:808–816. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto H, Octaviana F, Teraa Y, et al. Magnetic stimulation of the cauda equine in the spinal cord with a flat large round coil. J Neurol Sci. 2009;284:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jost WH, Schimrigk K. Magnetic stimulation of the pudendal nerve. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:697–699. doi: 10.1007/BF02054414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snooks SJ, Swash M, Henry MM. Abnormalities in central and peripheral nerve conduction in patients with anorectal incontinence. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:294–300. doi: 10.1177/014107688507800405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mellgren A, Wexner SD, Coller JA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1065–1075. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822155e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyle DJ, Murphy J, Gooneratne ML, et al. Efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1271–1278. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182270af1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]