Abstract

Hypothalamic obesity syndrome can affect brain tumor patients following surgical intervention and irradiation. This syndrome is rare at diagnosis in childhood cancer, but has been reported with relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Here we present a case of hypothalamic obesity syndrome as the primary presentation of a toddler found to have CNS+ B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Cytogenetic studies on diagnostic cerebrospinal fluid revealed MLL gene rearrangement (11q23). Hyperphagia and obesity dramatically improved following induction and consolidation chemotherapy. We describe a novel presentation of hypothalamic obesity syndrome in CNS B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, responsive to chemotherapy.

Keywords: hyperphagia, hypothalamic obesity syndrome, precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Hypothalamic obesity syndrome manifests with hyperphagia and intractable weight gain, most commonly following hypothalamic injury from cranial irradiation or central nervous system (CNS) tumor resection [1–4]. Survivors of childhood brain tumors may suffer from obesity as a consequence of hypothalamic damage [5]. Long-term hypothalamic obesity commonly occurs in patients with craniopharyngiomas following surgical resection despite pituitary hormone replacement [6].

Obesity is a reported complication of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), but rarely presents at diagnosis [7]. The incidence of obesity in childhood ALL patients who have received cranial irradiation is 40% [8]. Although cranial irradiation-induced obesity is likely a consequence of damage to the satiety center [3], hypothalamic obesity syndrome is rare in ALL survivors. Despite reports of hypothalamic obesity as a manifestation of CNS relapse in ALL [9–14], there remains little medical literature reporting this syndrome at primary diagnosis [15].

We report an unusual diagnostic presentation of hypothalamic obesity syndrome in a toddler found to have CNS+ precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (B-cell LL). We describe the child’s response to intensive chemotherapy and resolution of his hypothalamic obesity.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 36 month-old Caucasian male was referred to our Neuro-Oncology clinic following a brain MRI which was concerning for “leptomeningeal carcinomatosis.” The toddler presented with hyperphagia, insatiable appetite, and 32 pound (14.5 kg) weight gain over the preceding 6 months. Evaluation by his pediatrician included normal free T4, TSH, morning cortisol level, random growth hormone level, and fasting insulin level followed by brain MRI to evaluate for primary brain pathology.

The patient’s weight was 28.3 kg (> > 95th percentile) and height 99 cm (75–90th percentile). Past medical history was un-remarkable. Family history was remarkable for glioblastoma multiform in the paternal grandfather. Developmental milestones were normal with advanced cognition and speech. Physical examination was normal except severe obesity.

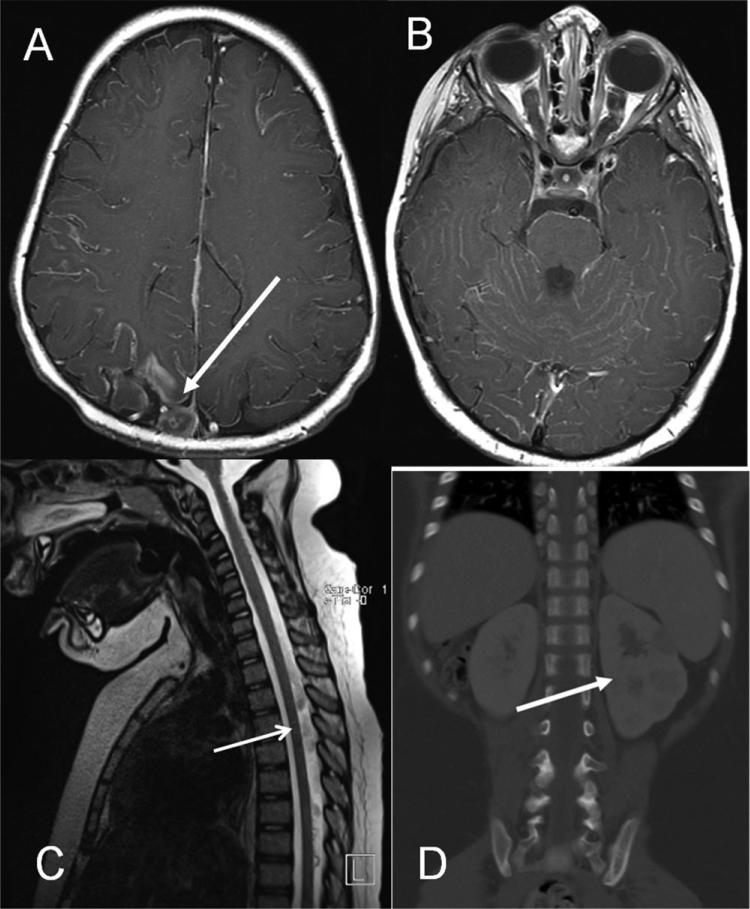

Brain MRI (Fig. 1A and B) showed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement of supratentorial and infratentorial compartments. A heterogeneous enhancing lesion was noted along right superior posterior sagittal sinus (Fig. 1A). Bilateral posterior portions of the optic nerves were thickened with enhancement (Fig. 1B). Spine MRI (Fig. 1C) demonstrated intraspinal leptomeningeal enhancement and clumping of the cauda equina.

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI T1 axial image demonstrating diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement and right nodular occipital lesion (arrow) prompting initial referral (A). T1 axial image highlighting enhancement of cranial nerves (B). Spine MRI sagittal section (C) demonstrating leptomeningeal enhancement along spinal cord (arrow). CT abdomen coronal image (D) of left kidney hypodense lesions (arrow).

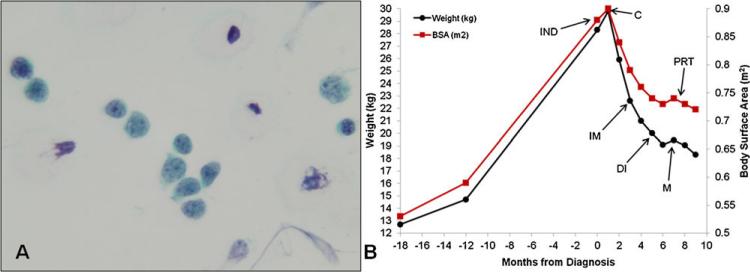

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Fig. 2A) evaluation revealed 788 total nucleated cells (TNC)/mm3, 92% blasts, 0 red blood cells, 8% lymphocytes, glucose 14 mg/dl, and protein 151 mg/dl. Cytology and flow cytometry revealed cells with high nuclear to chromatin ratios and CD10, CD19, and TdT positivity. Immunohistochemical stains were PAX-5+ and TdT+. These findings were consistent with precursor B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoma.

Fig. 2.

Malignant lymphoblasts on initial diagnostic lumbar puncture cytology (A). Change in weight and BSA between 18 months prior to diagnosis and through 9 months of A5971-B1 therapy (B). Rapid resolution of hypothalamic obesity noted following induction therapy. Start of each phase of therapy is indicated by arrowheads (IND, induction; C, consolidation; IM, interim maintenance; DI, delayed intensification; M, maintenance; PRT, proton radiation therapy).

CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed several hypodense lesions of the left kidney suggestive of lymphomatous involvement (Fig. 1D). Complete blood count and chemistries were unremarkable. Diagnostic bone marrow and cytogenetics were normal. Evaluations for underlying HIV or immune disorder were negative. Cytogenetics performed on CSF revealed 11q23 MLL gene rearrangement (MLL-R) and one copy of 12p13 ETV6. Therefore, the patient was given a final diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) Murphy Stage IV, precursor B-cell LL.

Our patient was treated with a modified COG A5971 protocol (Regimen B1), based on NHL-BFM-95 [16]. His lymphoma responded well to chemotherapy. CSF TNC/mm3 (blast %) on days 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 of induction were 810 (97%), 8 (18%), 17 (11%), 3 (0%), and 2 (0%), respectively. Hypodense lesions in his kidneys had radiographically resolved by the end of consolidation therapy and he had near-complete resolution of CNS leptomeningeal enhancement, with only a small residual focus of right occipital leptomeningeal enhancement. Given spinal MRI findings at presentation, the patient underwent 12 Gy supine craniospinal proton therapy during maintenance cycle 1 to the entire axis, with the cranial portion reflecting a classic leukemic helmet. The cranial field was given a 6 Gy boost for a total cranial dose of 18 Gy. We elected to administer craniospinal irradiation due to extensive intraspinal leptomeningeal disease at presentation. Because of potential decreased risk of toxicity to surrounding vital tissues, the family chose proton radiotherapy over conventional external beam craniospinal therapy.

The hypothalamic obesity syndrome showed dramatic improvement following initiation of chemotherapy. As seen in Figure 2B, our patient showed a rapid decrease in weight and body surface area (BSA) following consolidation therapy and has maintained his weight during maintenance consistent with resolution of his hyperphagia obesity syndrome. Currently, he remains in remission in maintenance therapy and exhibits age-appropriate eating habits and linear growth, with weight 18.75 kg (90th percentile) and height 104 cm (75th percentile).

DISCUSSION

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma represent 15% of all childhood cancers, of which 35% are lymphoblastic lymphomas (5% B-cell LL) [17]. CNS involvement occurs in about 5% of children with B-cell LL [18]. Although there is considerable overlap between precursor B-cell ALL and B-cell LL, diagnostic presentation in B-cell LL is more heterogeneous. Here we report a novel case of hypothalamic obesity syndrome as the diagnostic presentation for CNS+ B-cell LL.

Hypothalamic obesity syndrome occurs as a consequence of damage to the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) which serves to process information about diet, nutrients, and adiposity from peripheral hormones insulin, leptin, and ghrelin [3–4,19–20]. The VMH promotes feeding through efferent neuropeptide Y and agouti-related peptide signaling and satiety via a-melanocyte stimulating hormone and cocaine-amphetamine regulated transcript [3–4,19]. VMH dysregulation of feeding and satiety results in hyperphagia with caloric intake significantly greater the caloric expenditure and subsequent intractable weight gain. Given hypothalamic obesity syndrome is most commonly the result of cranial irradiation or surgical intervention, very few therapeutic interventions are successful. However, a previous randomized trial of octreotide demonstrated decreased weight gain with improved glucose tolerance and self-reported activity over 6 months [19].

Very few articles have been published in the English medical literature on hypothalamic obesity syndrome as a presentation of ALL [9,11,13]. Previous reported literature has been in CNS ALL relapse [9–13]. Similar to the presentation of our 36-month boy, a case of hyperphagia and obesity has been reported in the foreign literature as a new diagnostic presentation of young girl with ALL [15].

Similar to ALL, CNS+ disease portends a poor prognosis in B-cell LL. Previous literature from the BFM Group reports 5-year EFS of 64% in CNS+ NHL compared to 86% in CNS- patients [18]. The additional finding of 11q23 MLL-R on CSF lympho-blasts heightened concern for risk of future disease relapse. However, prognostic impact of MLL-R in B-cell LL is poorly understood in comparison to ALL. Our 36 month-old patient with B-cell LL achieved CNS remission on day 21 of induction with marked improvement of his hyperphagia and weight-stabilization by the end of induction therapy, despite 28 days of prednisone (Fig. 2B). His growth parameters have continued to normalize while on maintenance therapy.

In summary, we extend the medical literature by reporting the first case of primary CNS+ B-cell LL presenting with hypothalamic obesity syndrome. Primary intensive chemotherapy resolved hypothalamic obesity syndrome in our patient. Despite response to therapy, the prognosis remains guarded due to MLL-R and primary CNS disease. This case highlights the need for CSF evaluation in patients presenting with hypothalamic obesity to evaluate for underlying CNS leukemia or lymphoma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

T. C. Q. is supported by the T32 Postdoctoral Research Training in Pediatric Clinical and Developmental Pharmacology (T32HD069047).

Grant sponsor: T32 Postdoctoral Research Training in Pediatric Clinical and Developmental Pharmacology; Grant number: T32HD069047.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Nothing to declare

REFERENCES

- 1.Bray GA. Syndromes of hypothalamic obesity in man. Pediatr Ann. 1984;13:525–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray GA, Inoue S, Nishizawa Y. Hypothalamic obesity. The autonomic hypothesis and the lateral hypothalamus. Diabetologia. 1981;20:366–377. doi: 10.1007/BF00254505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lustig RH. Hypothalamic obesity: Causes, consequences, treatment. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008;6:220–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee M, Korner J. Review of physiology, clinical manifestations, and management of hypothalamic obesity in humans. Pituitary. 2009;12:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s11102-008-0096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lustig RH, Post SR, Srivannaboon K, et al. Risk factors for the development of obesity in children surviving brain tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:611–616. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivasan S, Ogle GD, Garnett SP, et al. Features of the metabolic syndrome after childhood craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:81–86. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard SC, Pui CH. Endocrine complications in pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Rev. 2002;16:225–243. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(02)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sklar CA, Mertens AC, Walter A, et al. Changes in body mass index and prevalence of overweight in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Role of cranial irradiation. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35:91–95. doi: 10.1002/1096-911x(200008)35:2<91::aid-mpo1>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.al-Rashid RA. Hypothalamic syndrome in acute childhood leukemia. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1971;10:53–54. doi: 10.1177/000992287101000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhawan BC, Choudhry VP. Hypothalmic syndrome in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Indian Pediatr. 1985;22:859–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greydanus DE, Burgert EO, Jr, Gilchrist GS. Hypothalamic syndrome in children with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 1978;53:217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurmashov VI, Koshel IV, Lebedev BV, et al. Hypothalamic syndrome in children with acute leukemia. Pediatriia. 1978:23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tilley E, Ryalls MR, Williams MP. Ct demonstration of pituitary stalk relapse in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Clin Radiol. 1989;40:634–635. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(89)80330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomaszewska R, Wieczorek M, Hicke A, et al. Obesity as the first manifestation of central nervous system involvement in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Pol. 1996;71:701–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiliro G, Russo A, Sciotto A, et al. Insulin and growth hormone secretion in a leukaemic girl with hypothalamic syndrome. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1977;66:261–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1977.tb07846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woessmann W, Seidemann K, Mann G, et al. The impact of the methotrexate administration schedule and dose in the treatment of children and adolescents with b-cell neoplasms: A report of the bfm group study nhl-bfm95. Blood. 2005;105:948–958. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health; Philadelphia: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salzburg J, Burkhardt B, Zimmermann M, et al. Prevalence, clinical pattern, and outcome of cns involvement in childhood and adolescent non-hodgkin's lymphoma differ by non-hodgkin's lymphoma subtype: A Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster group report. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3915–3922. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lustig RH, Hinds PS, Ringwald-Smith K, et al. Octreotide therapy of pediatric hypothalamic obesity: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2586–2592. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-030003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bray GA, Gallagher TF., Jr. Manifestations of hypothalamic obesity in man: A comprehensive investigation of eight patients and a reveiw of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1975;54:301–330. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]