Abstract

A fundamental role of the taste system is to discriminate between nutritive and toxic foods. However, it is unknown whether bacterial pathogens that might contaminate food and water modulate the transmission of taste input to the brain. We hypothesized that exogenous, bacterially-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS), modulates neural responses to taste stimuli. Neurophysiological responses from the chorda tympani nerve, which innervates taste cells on the anterior tongue, were unchanged by acute exposure to LPS. Instead, neural responses to sucrose were selectively inhibited in mice that drank LPS during a single overnight period. Decreased sucrose sensitivity appeared 7 days after LPS ingestion, in parallel with decreased lingual expression of Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 transcripts, which are translated to T1R2+T1R3 subunits forming the sweet taste receptor. Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 mRNA expression levels and neural responses to sucrose were restored by 14 days after LPS consumption. Ingestion of LPS, rather than contact with taste receptor cells, appears to be necessary to suppress sucrose responses. Furthermore, mice lacking the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 for LPS were resistant to neurophysiological changes following LPS consumption. These findings demonstrate that ingestion of LPS during a single period specifically and transiently inhibits neural responses to sucrose. We suggest that LPS drinking initiates TLR4-dependent hormonal signals that downregulate sweet taste receptor genes in taste buds. Delayed inhibition of sweet taste signaling may influence food selection and the complex interplay between gastrointestinal bacteria and obesity.

Keywords: neuro-immune interactions, chorda tympani nerve, taste receptor cell, neurophysiology, Tas1r1, Tas1r2, Tas1r3

Recent studies demonstrate the detection of bacterial pathogens by mammalian chemosensory systems. Solitary chemosensory cells (SCCs), scattered throughout the respiratory epithelium, respond to bacterial quorum sensing molecules as well as bitter irritants such as denatonium (Finger et al., 2003, Tizzano et al., 2010). Ligand binding to SCCs rapidly decreases respiration, and presumably triggers a local inflammatory response (Tizzano et al., 2010). Sensory neurons in the vomeronasal organ also respond to bacterial pathogens via formyl peptide receptors, and may sense contaminated food or sick conspecifics (Liberles et al., 2009, Riviere et al., 2009). Whether taste receptor cells contribute to the recognition of external bacterial pathogens is currently unknown.

Chemical stimuli representing sweet, bitter, salty, sour, and umami bind protein receptors and channels on the taste cell apical membrane to initiate transduction. Sensory information from taste cells on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is transmitted to the brain by the chorda tympani (CT) nerves, which are particularly responsive to sweet and salty stimuli in many species, including C57BL/6 (B6) mice (Pfaffman, 1955, Ferrell et al., 1981, Mistretta and Bradley, 1983, Iwasaki and Sato, 1984, Shingai and Beidler, 1985, Gannon and Contreras, 1995, Danilova and Hellekant, 2003). Taste receptor cells face constant environmental and pathogenic challenges, but are replaced every 10 days or so. In keeping with this plasticity, taste cells can regenerate morphologically and functionally after denervation (Olmstead, 1921, Guth, 1971, Cheal and Oakley, 1977, Hill and Phillips, 1994). The peripheral taste system has been a useful model to study nerve and sensory target cell plasticity, and more recently, the impact of the immune system on sensory function.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), also known as endotoxin, is derived from the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria (Abbas and Lichtman, 2003). LPS signals through the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 complex, resulting in the production of proinflammatory cytokines (Raetz and Whitfield, 2002). Multiple factors (i.e. delivery method, dose) influence the effects of LPS on the taste system. Intraperitoneal LPS enhances macrophage responses to CT nerve sectioning (Cavallin and McCluskey, 2005) and promotes normal taste function in the neighboring, intact CT (Phillips and Hill, 1996). In the absence of neural injury, LPS inhibits taste receptor cell proliferation and stimulates the expression of proinflammatory genes in taste buds (Wang et al., 2007, Wang et al., 2009, Cohn et al., 2010). Subcutaneous, lingual injections of LPS impair sodium taste function by stimulatng neutrophil infiltration of the sensory field (Steen et al., 2010).

Here, we determine whether taste input to the CNS is modulated by orally delivered LPS used to mimic exposure to bacterially-contaminated food or water. Taste function is unchanged by acute, lingual exposure to LPS. However, neural responses to sucrose are inhibited in mice that ingest the endotoxin. We report the TLR4-dependence of these effects and resulting changes in Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 transcripts that form subunits which mediate sweet taste transduction (Nelson et al., 2001, Li et al., 2002). These studies suggest a novel link between ingested LPS and gustatory input to the brain.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

The Animal Care and Use Committee at Georgia Regents University approved all protocols, which follow guidelines set by the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23). Female, specified pathogen-free (SPF) B6 mice (Stock No.000664, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and female SPF C57BL/10ScNJ mutant mice (Stock No.003752, Jackson Laboratory) were 6–8 weeks old during experiments. B6 mice were chosen because of their widespread use in immunology and neurobiology, and more specifically because they are responsive to sweet taste stimuli (Lush, 1989, Capeless and Whitney, 1995, Bachmanov et al ., 1996). The toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 is absent in C57BL/10SCNJ mice, which are unresponsive to LPS. Moreover, this strain is derived from a “sweet taster” strain. Pilot studies revealed no consistent differences in CT responses from male vs. female B6 control mice. Thus, we chose to use females to be consistent with previous work in our laboratory (McCluskey, 2004, Steen et al., 2010). Mice were group-housed in polyurethane shoebox cages for at least one week before experiments began, when they were moved to single housing. Humidity, temperature, and light (12:12 hr light: dark with lights on at 6:00 am) were automatically controlled in a barrier environment. Cages were bedded with autoclaved 1/8” cut corncob (Harlan Laboratories, Dublin, VA). Mice had free access to irradiated Teklad rodent chow (#2918; Harlan) and autoclaved distilled water, other than a 39 hr period when mice were water-deprived (described below) but provided with LPS or vehicle alone.

Neurophysiology

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (0.5 mg/g, i.p.) and sodium pentobarbital (0.5 mg/g, i.p.). Supplemental doses of these drugs were administered as needed to maintain a surgical level of anesthesia. Body temperature was maintained with a water-circulating heating pad (Gaymar T pump, Kent Scientific Corporation, Torrington, CT) throughout the surgical and recording period. Hypoglossal nerves were sectioned to stop tongue movement, and mice tracheotomized and secured in an atraumatic head holder (Erickson, 1966). The left CT nerve was dissected using a mandibular approach, as previously described in rat (Hill and Phillips, 1994, Wall and McCluskey, 2008). After removing overlying bone and tissue, the CT nerve was dissected near the tympanic bulla, cut centrally, and placed on a platinum electrode. In mice, neural activity could be recorded without desheathing the nerve. Another platinum electrode was grounded in adjacent muscle, and the surgical cavity filled with warm mineral oil.

Whole nerve activity was amplified with a P511 AC Preamplifier (bandpass 1–3000 Hz , Grass Instruments, Warwick, RI) and noise subtracted (Humbug 50/60 Hz Noise Eliminator, Quest Scientific, North Vancouver, BC, Canada). Amplified activity was summated with a time constant of 1.5–2.0 sec using an integrator built specifically for whole-nerve recordings (Harper and Knight, 1987). Integrated responses were recorded and analyzed off-line with Power Lab 4S/P (AD Instruments). Tastants were mixed in distilled water and ∼3 ml applied to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue with a syringe. The following stimuli were presented (in this order) at room temperature with an inter-stimulus interval of ≥1 min: 0.1 M and 0.5 M NaCl; 0.1 M and 0.5 M L-glutamic acid monopotassium salt (MPG); 0.1 M, 0.5 M and 1.0 M sucrose; 16% polycose (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL); 1.0 M D-(+)-glucose; 0.01 N hydrochloric acid (HCl; Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA); 0.01 M quinine hydrochloride dehydrate (QHCl); and 0.01 M denatonium benzoate. A more limited stimulus panel [i.e. in order, 1 M sucrose, polycose, glucose, HCl, 0.05 M and 0.10 M sodium saccharin; and 0.025 M and 0.05 M potassium acesulfame (aceK)] was used to test additional non-caloric sweeteners in a subset of mice at day 7 after drinking LPS (n=6) or sucrose vehicle (n=6). Stimuli remained on the tongue for 30 sec before rinsing for at least 1 min with dH2O. Chemicals used in taste solutions were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless noted above. The magnitude of integrated responses was measured 20 seconds after onset. Taste responses were normalized to 0.5 M ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) responses at the beginning and end of each concentration series as in previous work (Hill and Phillips, 1994, Wall and McCluskey, 2008). Bracketing NH4Cl responses were averaged, and taste responses were expressed as a ratio of this mean. We analyzed stable series bracketed by NH4Cl responses within 10% of each other. At the end of the recording, mice were euthanized with sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg, i.p.) followed by thoracotomy.

Acute LPS treatment

Phenol-extracted LPS from E. coli 026:B6 (#L8274, Sigma) was made daily from lyophilized powder in all experiments. We first tested the effects of LPS applied to the anterior tongue to determine acute effects on neural responses. Baseline CT responses to all tastants were recorded before applying LPS (10 µg/ml in sterile, pyrogen-free dH2O) to the tongue for 10 min. A second complete set of tastants diluted in LPS (5 µg /ml) were then applied to the tongue to test acute modulation of CT neural responses. Control mice received lingual treatment with dH2O alone, followed by a complete set of tastants diluted in dH2O. This group was included to control for the effects of recording time on CT responses, since extended periods of anesthesia can affect neural activity (Beidler and Smallman, 1965, Hellekant et al., 1979). Two-way repeated measure analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to determine the effects of lingual treatment (i.e. LPS or dH2O) and time (i.e. before and after lingual treatment) on CT responses.

LPS ingestion

We noted during pilot studies that mice avoided drinking water containing LPS. Thereafter, we provided mice with either LPS (10 µg / ml) diluted in 0.15 M sucrose, or sucrose alone, for 15 hr starting at lights out (6:00 pm) to promote consumption. Similar concentrations of sucrose are voluntarily consumed by non-water-deprived mice (Bachmanov et al., 1996). In separate experiments, we tested the vehicle-dependency of the effects of LPS by providing water-deprived mice with LPS in 0.15M NaCl or NaCl alone. Solutions were given in plastic 13 ml volumetric drinking tubes fitted with lixit valves designed for mice mounted in rubber stoppers (Med Associates, Inc., Georgia, VT). Treated mice were housed in cages adjacent to each other on the same rack. Solution volumes were recorded before and after treatment to determine intake and confirm that mice consumed LPS. We did not correct for spillage. Water had been removed at 6:00 pm during the previous dark period and was replaced on the morning following LPS access.

Systemic LPS provokes inflammatory responses that lead to fever, anhedonia, and (at high doses) even death by well-studied mechanisms (Dantzer et al., 1998, Alexander and Rietschel, 2001, Salomao et al., 2012). In contrast, oral administration of LPS is less common, perhaps because it is non-toxic to healthy mice even at doses 16.5X greater than that used here (Harper et al., 2011). Consistent with this report, we did not observe obvious signs of sickness, including changes in body position (hunched back, lying on side, or prone), sustained eye closure, piloerection, dragging or elevated tail position, or failure to respond to finger stroke of the back (Brown et al., 2005, Hines et al., 2013). We recorded these observations, rectal temperature, and body weight between 9:00–10:00 am on day −1 to day 7 post-ingestion in a subset of mice (n=12). Changes in body temperature and body weight were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVAs with time post-ingestion and oral treatment (i.e. LPS or sucrose alone) as main factors.

CT recordings were performed at day 1, 7, or 14 days after LPS ingestion. We compared nerve responses between groups with repeated-measures two-way ANOVAs using stimulus concentration and oral treatment (i.e. LPS in sucrose or sucrose alone) as factors. Bonferonni posttests were performed when there were significant effects of either factor or their interaction. When a single stimulus concentration was tested, we used Student’s t tests to compare CT responses from groups given LPS with those given vehicle. CT responses to LPS diluted in 0.15 M NaCl, or NaCl vehicle alone, were analyzed in the same way.

In separate experiments, we limited LPS exposure to the anterior tongue. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (0.5 mg/g, i.p.) and sodium pentobarbital (0.5 mg/g, i.p.). The anterior tongue was gently extended from the oral cavity and a micro serrefine clip with atraumatic serrations (15 mm; Fine Science Tools; Foster City, CA) placed on the ventral side of the tongue to maintain its position. A piece of sterile cotton soaked with LPS mixed in sucrose or sucrose alone was placed on the fungiform region of the anterior tongue and saturated every 10 min for 2 hr. The posterior tongue and oral cavity were not exposed to solution. The tongue was rinsed with dH2O for ≥1 min. Mice recovered from anesthesia and were maintained on control chow and water before CT recordings 7 days later. The timing was a compromise between approximating taste bud exposure to LPS during ingestion studies (above) and maintaining appropriate levels of anesthesia without anesthetic overdose. The effects of stimulus concentration and lingual treatment (i.e. LPS or vehicle) on CT responses were compared with repeated measures two-way ANOVAs and Bonferonni posttests as described above for LPS ingestion studies. We used Student’s t tests to determine the effect of lingual treatment on neural responses to single stimulus concentrations.

Lingual epithelial preparation and quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Mice were overdosed with sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg, i.p.) and anterior tongues dissected at 7 days after LPS (n=6) or vehicle (n=6) ingestion. Additional mice were euthanized at day 14 after LPS (n=3) or vehicle (n=3) ingestion. Approximately 0.3 ml of buffer containing 2.44 mg/ml dispase, 0.96 mg/ml collagenase A, and 1.1 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor in Tyrode's solution base was injected under the epithelium of the excised tongue then incubated in O2-bubbled Tyrode’s solution at room temperature. The lingual epithelium was carefully separated from the underlying muscle, and rinsed thoroughly in Tyrode’s solution.

Total RNA from the anterior lingual epithelium was isolated with the Rneasy Mini kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA), and then reverse transcribed using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We used the following primer pairs: (1) Tas1r2 forward primer GCACCAAGCAAATCGTCTATCC and reverse primer ATTGCTAATGTAGGTCAGCCTCGTC (custom designed by Primer Premier 5.0); (2) Tas1r3 forward primer TGCTGCTATGACTGCGTGGAC and reverse primer AAGAAGCACATAGCACTTGGG (Shigemura et al., 2008); (3) Tas1r1 forward primer TGGCAGCTATGGTGACTACG and reverse primer CAGCACCACAGACCTGAAGA (custom designed by Primer 3, Version 0.4.0); and (4) β-actin forward primer GGTCAGAAGGACTCCTATGTGG and reverse primer TGTCGTCCCAGTTGGTAACA (Intregrated DNA Technologies; Coralville, IA). qRT-PCR was performed using the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems; Carlsbad, CA). Signal was detected by Chromo 4 Continuous Fluorescence Detector (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; Hercules, CA) and analyzed by an Opticon Monitor (MJ Geneworks, Inc.; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). 30 cycles were accomplished with qRT-PCR conditions at 94 °C for 20 seconds, 57 °C for 30 seconds, and 72° C for 35 seconds for each cycle. Expression levels of Tas1r transcripts were normalized to β-actin by using the 2 (-Delta Delta C(T)) method, to quantify the signal in the LPS treatment group relative to a sample from the vehicle control group (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Expression levels were compared with one-way ANOVAs followed by Dunnett’s posttests.

Results

Effects of acute, lingual LPS on taste function

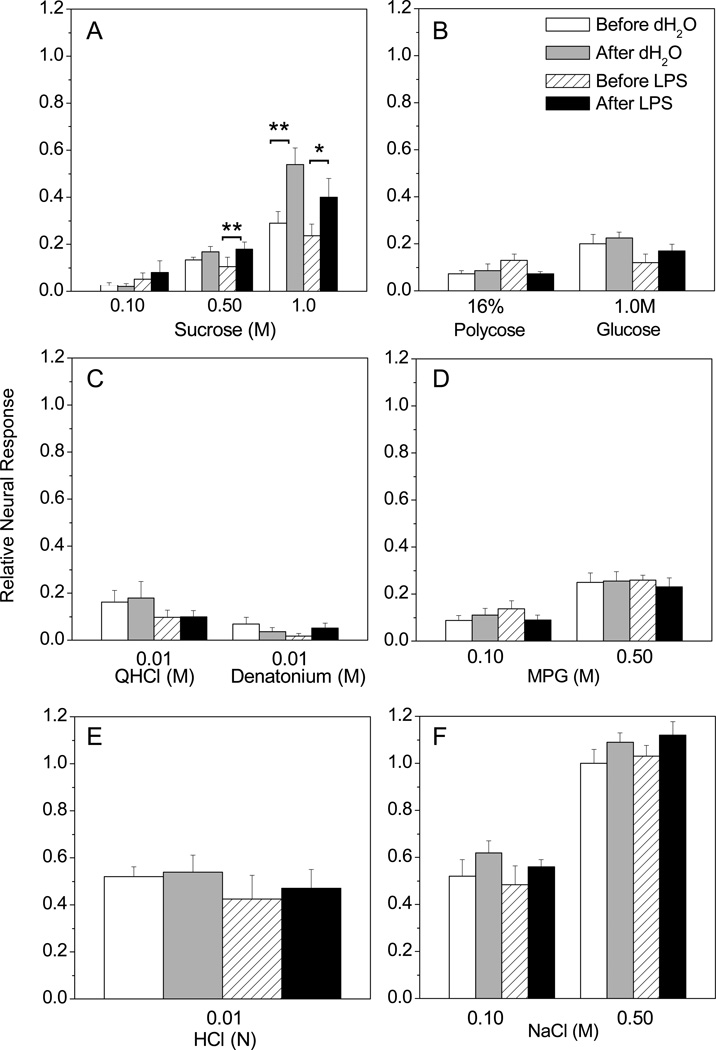

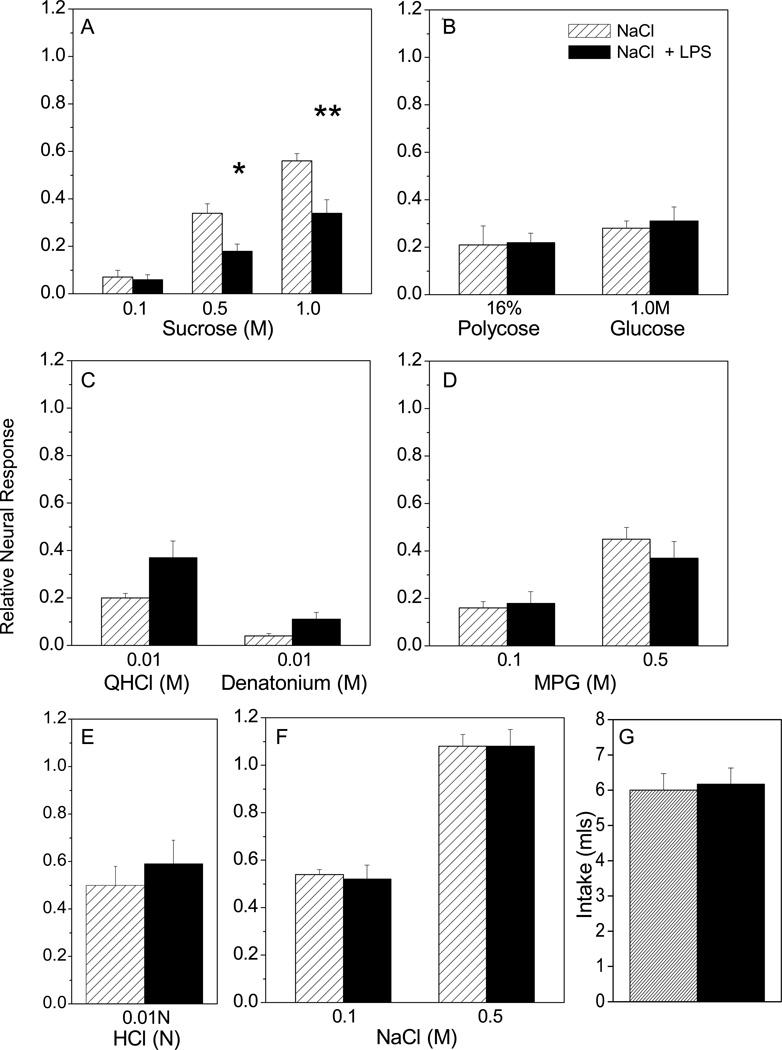

We applied LPS to the anterior tongue to mimic oral exposure to bacteria and test whether this treatment has immediate effects on taste function. Baseline CT nerve responses to a series of tastants were recorded before and after applying LPS (10 µg/ml for 10 min) or dH2O vehicle to the anterior tongue. Stimulus series that followed acute LPS treatment were also diluted in LPS (5 µg/ml). Mean relative CT responses after LPS or vehicle are shown in Fig. 1. There were no significant main effects for most tastants, including polycose, glucose, QHCl, denatonium, MPG, HCl, NaCl, and the lowest concentration of sucrose tested. CT responses to 0.5 M sucrose increased slightly with time after either vehicle or LPS were applied to the tongue (Fig. 1 A). In other words, there was a significant effect of time, but not lingual treatment or their interaction [F (1, 12) = 17.16, p = 0.0014], in the LPS-treated group. This effect was more pronounced when 1.0 M sucrose was the stimulus. Time had a significant effect on CT responses [F (1, 12) = 25.06] for groups treated either with water (p < 0.01) or LPS (p < 0.05). These results indicate that taste receptor cell function is not acutely modulated by lingual LPS. Rather, CT responses to sucrose unexpectedly increased between the first and second presentations, separated by approximately 1 hr.

Figure 1.

Acute effects of lingual LPS on CT nerve responses. Mean, normalized CT nerve responses (±SEM) to multiple tastants are shown before and after lingual application of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; n=6) (10 µg /ml) or dH2O alone (n=6) for 10 minutes. Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to determine the effects of time (i.e. before vs. after LPS) and oral treatment (i.e. LPS or dH20) on neural responses to multiple tastants. (A) There was a significant effect of time on CT responses to 0.50 M [F (1, 12) = 17.16, p = 0.0014] and 1.0M [F (1, 12) = 25.06] sucrose in mice treated with either lingual LPS (p < 0.05) or dH2O (p < 0.01). However, there were no main effects of lingual treatment or interaction on sucrose responses. There were no significant main effects (i.e. time, lingual treatment or interaction) on responses to (B) polycose, glucose, (C) QHCl, denatonium, (D) MPG, (E) HCl, or (F) NaCl. Thus, acute application of LPS to the sensory field did not elicit specific changes in CT responses. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 from Bonferonni posttests.

Ingested LPS has sucrose-specific, delayed effects on taste function

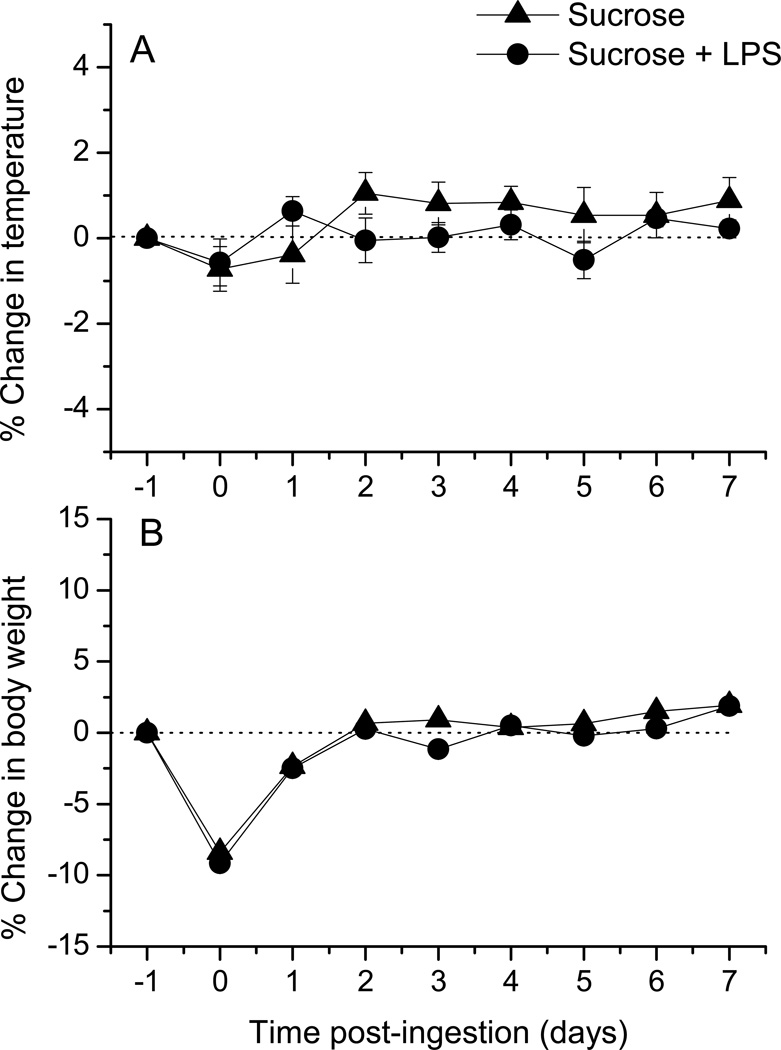

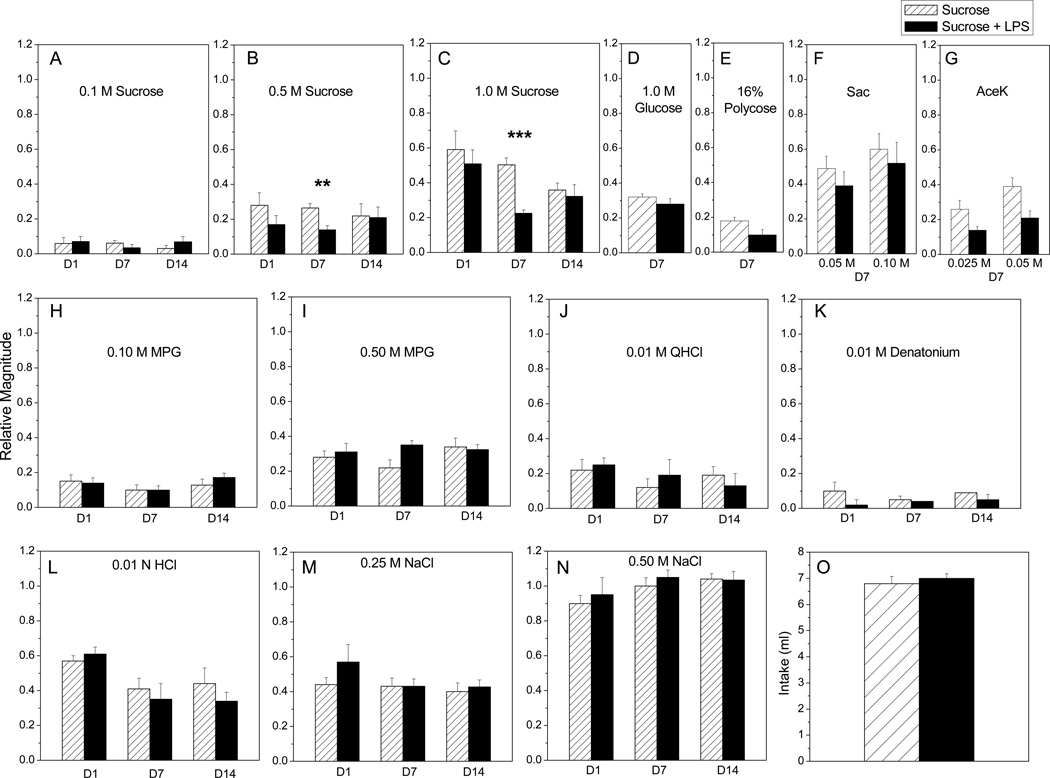

We next tested whether the ingestion of LPS, rather than just contact with fungiform taste buds on the anterior tongue, can modulate peripheral taste function. In these experiments we provided mice with overnight access to LPS in 0.15 M sucrose to mimic ingestion of bacterially-contaminated water or food. Control groups were given access to sucrose alone. CT nerve responses to taste stimuli were then recorded at 1, 7, and 14 days following LPS ingestion. We also recorded body temperature and weight to assess the general health status in a subset of mice. There was a significant main effect of time on the change in body temperature (Fig. 2A) [F (7, 40) =2.72, p = 0.02]. However, there were no significant effects of oral treatment or interaction, and Bonferonni posttests revealed no significant differences between groups ingesting LPS or sucrose alone. Likewise, body weight was significantly affected by time post-ingestion in both groups [F (7, 40) = 9.10; p < 0.0001), but there were no significant main effects of oral treatment or interaction effects (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that LPS ingestion did not differentially affect temperature or body weight. Instead, groups drinking either LPS or vehicle exhibited a decrease in weight on the day after water deprivation but recovered quickly. Mice drank similar amounts of LPS in sucrose or sucrose alone during the overnight exposure period (Fig. 3O).

Figure 2.

LPS ingestion did not alter temperature or body weight. The percent change in (A) rectal temperature and (B) body weight relative to pretreatment values at day −1 is shown through day 7 after mice drank LPS in sucrose or sucrose alone (day 0)(n=6 / group). Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs showed a main effect of time on temperature [F (7, 40) = 2.719; p = 0.02], but neither oral treatment nor interaction effects were significant. The effect of time on body weight was also significant [F (7, 40 = 9.099; p <0.0001], since both groups exhibited weight loss on the day after overnight water deprivation. Note that pre-deprivation body weights were restored within 2 days in both groups. Oral treatment (i.e. ingestion of LPS in sucrose or sucrose alone) or interaction effects on body weight were not significant.

Figure 3.

LPS ingestion has delayed inhibitory effects on CT nerve responses to sucrose. CT responses were recorded at day 1, 7, or 14 after overnight access to LPS or vehicle (n=6–8 / group at each time point). When multiple concentrations of a stimulus were tested, two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to determine the effect of stimulus and oral treatment. When single concentrations of a stimulus were tested, Student’s t tests were used to compare LPS and vehicle treated groups. (A-C) At day 7, there were significant main effects of oral treatment [F (1, 21) = 50.73, p < 0.0001], stimulus concentration [F (2, 21) = 62.51, p < 0.0001] and interaction [F (2, 21) = 62.51, p < 0.0001] on neural responses. Posttests indicate that CT responses to 0.5 M (p < 0.01) and 1.0 M (p < 0.001) sucrose were inhibited at day 7 after LPS ingestion. (D-G) Responses to additional saccharides and non-caloric sweeteners were measured at day 7 post-ingestion. Responses to (D) glucose, (E) polycose; and (F) saccharin (sac) did not significantly differ between treatment groups. Main effects of oral treatment [F (1, 12) = 5.78; p = 0.03] and stimulus concentration [F (1, 12) = 21.61; p = 0.0006] on responses to (G) acesulfame K (AceK) were significant, but posttests did not indicate a significant difference between groups. There was a predictable main effect of stimulus concentration, but not oral treatment, on CT responses to (H, I) MPG as reported in the text for day 1, 7, and 14. LPS ingestion did not significantly alter CT responses to (J) QHCl, (K) denatonium or (L) HCl at any time point. (M, N) CT responses were affected by NaCl concentration but not LPS ingestion (see text for statistical results). (O) Mice drank similar amounts of LPS in sucrose and sucrose alone during the overnight access period. *Significant value of **P < 0.01, and ***P<0.001 from Bonferonni posttests.

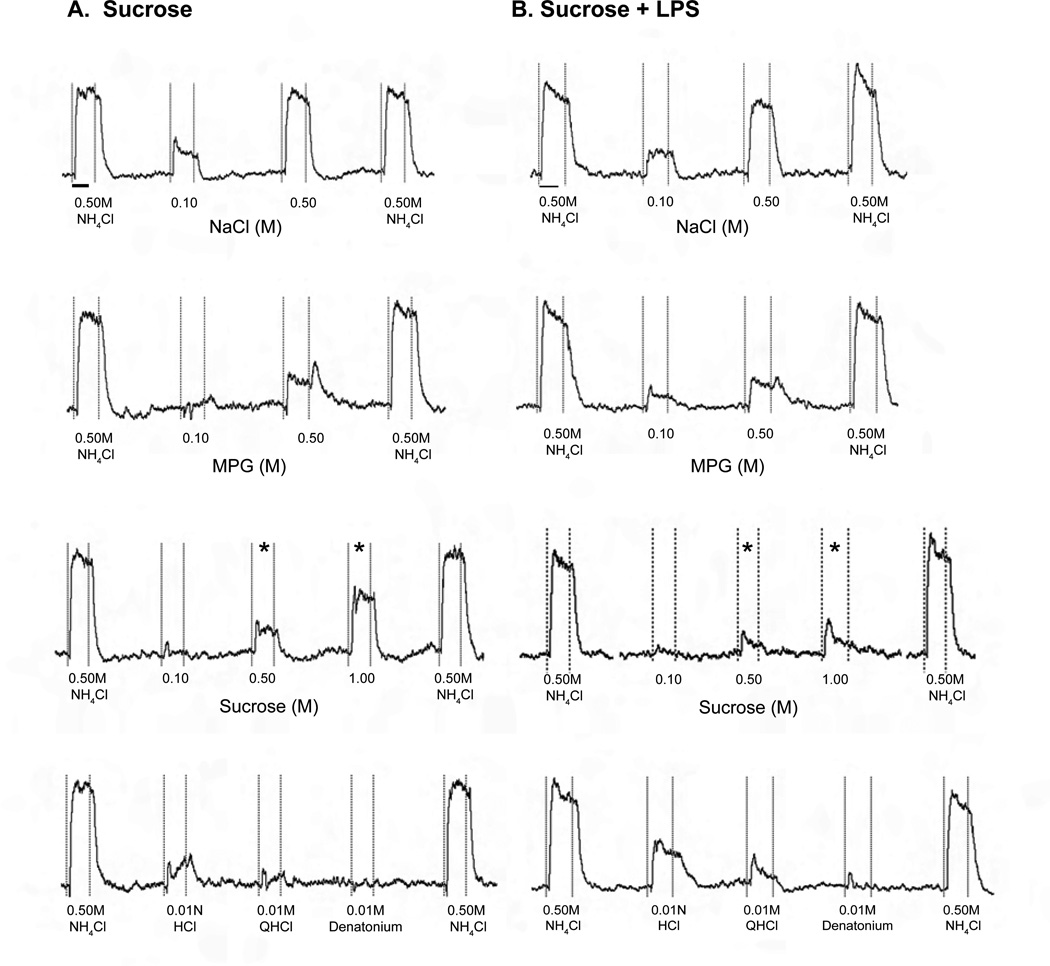

Mean CT response magnitudes recorded from mice drinking LPS or vehicle alone are shown in Fig. 3. At day 1 post-ingestion, there were no main effects of LPS treatment or interaction. As anticipated, stimulus concentration had a significant effect on CT responses to sucrose [F (2, 15) = 27.92, p < 0.0001] (Fig. 3A, B, C), MPG [F (1, 10) = 23.46; p=0.0007] (Fig. 3H, I), and NaCl [F (1, 10) = 132.64, p < 0.0001] (Fig. 3M). At day 7, however, LPS treatment caused specific deficits in CT nerve function. Treatment with LPS [F (1, 21) = 50.73, p < 0.0001], stimulus [F (2, 21) = 62.51, p < 0.0001], and their interaction [F (2, 21) = 10.17, p = 0.0008] had significant effects on neural responses. Posttests indicated significant decreases in responses to 0.5M sucrose (p < 0.01) and 1 .0M (p < 0.001) sucrose in mice that drank LPS (Fig. 3B, C). Selective inhibition of CT responses to 0.50M and 1 .0M sucrose can also been seen in representative response traces recorded at day 7 (Fig. 4). Given the effects of ingested LPS on sucrose at day 7, we tested whether responses to additional saccharides and sweeteners were similarly inhibited. Surprisingly, responses to glucose, polycose, and saccharin were not significantly affected by LPS treatment (Fig. 3D, E, F). There were significant effects of stimulus [F (1, 12) = 21.61; p =0.0006] and oral treatment with LPS [F (1, 12) = 5.78; p = 0.03] but not interaction on CT responses to the sweetener, aceK (Fig. 3G). However, Bonferonni posttests did not show significant differences in aceK responses among oral treatment groups. Responses to the umami stimulus, MPG, recorded at day 7 post-treatment showed significant main effects of stimulus concentration [F (1, 14) = 66.78, p < 0.0001] and interaction [F (1, 14) = 8.08, p = 0.01], but not LPS treatment (Fig. 3H, I). There was also a significant main effect of NaCl concentration at this time [F (1, 14) = 910.89, p < 0.0001], though oral treatment and interaction were not significant (Fig. 3M, N). CT responses to single concentrations of bitter and acid stimuli were similar in mice ingesting LPS compared to vehicle (Fig. 3J, K, L). Thus, LPS ingestion significantly and selectively inhibited CT responses to higher concentrations of sucrose at day 7.

Figure 4.

Representative CT nerve response traces at day 7 after ingestion of (A) sucrose vehicle or (B) LPS ingestion (one mouse each). Responses are bracketed by responses to the standard stilus (0.5 M NH4Cl). The bar under the first response to NH4Cl in each column indicates 20 sec, when response magnitudes were measured. Vertical dotted lines indicate stimulus delivery and rinse. Responses to 0.5 M and 1.0 M sucrose (*) were reduced relative to NH4Cl responses in the mouse that drank LPS (B) compared to the control (A). Responses to stimuli representing other taste modalities, including NaCl, monopotassium glutamate (MPG), HCl, quinine (QHCl) and denatonium, are comparable in the LPS-treated and control mice.

By day 14 after LPS treatment (Fig. 3A–C; H-N), main effects were limited to stimulus concentration for sucrose [F (2, 15) = 23.11, p < 0.0001] (Fig. 3A, B, C), MPG [F (1, 10) = 21.70, p = 0.0009] (Fig. 3H, I), and NaCl [F (1, 10) = 184.54, p < 0.0001] (Fig. 3N). Likewise, responses to single concentrations of bitter and acid stimuli were not significantly different between LPS and vehicle-drinking groups.

Ingestion of LPS diluted in 0.15 M sucrose specifically inhibited neural responses to sucrose (Fig. 3A, B, C; Fig. 4). We tested the vehicle-dependency of this effect by providing mice with LPS diluted in 0.15M NaCl or NaCl alone. Water-deprived mice readily drank this concentration of saline, as shown in Fig. 5G. CT responses recorded 7 days after drinking LPS in saline confirmed results obtained with sucrose vehicle. There were significant main effects of both stimulus concentration [F (2, 15) = 48.67, P < 0.0001] and treatment [F (1, 15) = 19.83, P = 0.0005], though not their interaction, on sucrose responses. Posttests demonstrated that LPS ingestion inhibited responses to 0.5M (P < 0.05) and 1.0M sucrose (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5A). There were main effects of stimulus concentration of NaCl [F (1, 10) = 228.03, p < 0.0001], and MPG [F (1, 10) = 35.05, p =0.0001], but not treatment or interaction (Fig. 5D, F). CT responses to single concentrations of polycose, glucose, HCl, and QHCl were not significantly different in mice that drank LPS compared to vehicle (Fig. 5B–F). These findings demonstrate that LPS ingestion inhibits sucrose responses independently of the vehicle.

Figure 5.

Effects of LPS ingestion on sucrose responses are not vehicle-specific. Mice were provided overnight access to LPS in 0.15M NaCl (n=6), or NaCl alone (n=6). CT responses were recorded at day 7 post-ingestion. When multiple concentrations of (A) sucrose, (D) MPG, or (F) NaCl were applied, two-way repeated measures ANOVAs revealed a significant main effect of stimulus concentration as detailed in the text, but interaction effects were not significant. There was a significant main effect of oral treatment [F (1, 15) = 19.83, P = 0.0005] on sucrose responses. Nerve responses to 0.5M (p < 0.05) and 1.0M (p < 0.01) were significantly reduced by ingestion of LPS vs. NaCl alone. Neural responses to single concentrations of (B) polycose, glucose, (C) QHCl, denatonium, and (E) HCl were not significantly different in mice ingesting LPS vs. NaCl alone, as determined by Student’s t tests. There were no significant main effects of oral treatment or interaction when CT responses to multiple concentrations of (D) MPG or (F) NaCl were tested. (G) Intake (ml) of LPS in NaCl vehicle or vehicle alone (lower right) was similar. *Significant value of P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 from Bonferonni posttests.

LPS ingestion vs. contact with sensory field

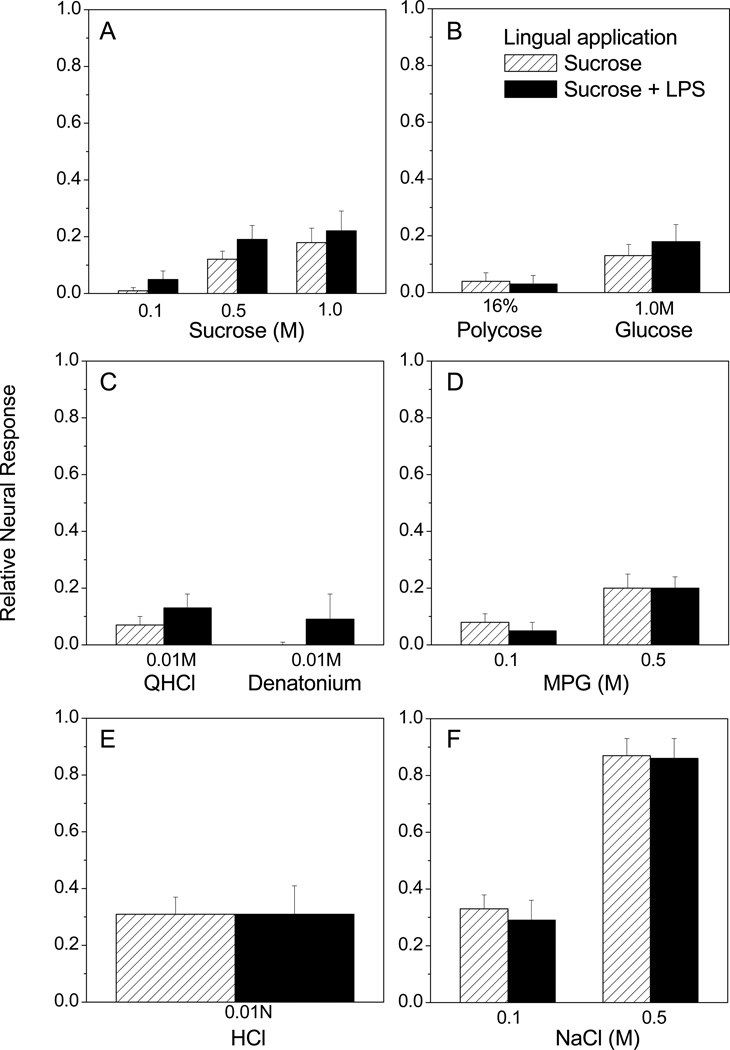

We next determined whether inhibition of sucrose responses depends upon direct interaction between LPS and taste receptor cells or post-ingestional effects. In these experiments we bathed the anterior tongue of anesthetized mice in LPS solution before performing CT recordings 7 days later. As shown in Fig. 6, CT responses were similar whether mice received lingual exposure to LPS or sucrose vehicle alone. There were significant main effects of stimulus concentration for sucrose [F (2, 12) = 11.11, p = 0.0019], MPG [F (1, 8) = 9.79, p = 0.01], and NaCl [F (1, 8) = 99.17, p < 0.0001]. However, neither lingual treatment nor interaction effects were significant. CT responses to polycose, glucose, QHCl, denatonium, and HCl were also similar between groups given lingual LPS or vehicle (Fig. 6B, C, and E). Thus, LPS is only effective in inhibiting sucrose responses when mice consume the solution.

Figure 6.

Lingual exposure to LPS without ingestion does not inhibit CT responses to sucrose. LPS (n=5) or distilled water (n=5) was applied to the anterior tongue of anesthetized mice, rinsed, and mice recovered from anesthesia. CT responses recorded 7 days later. When multiple concentrations of (A) sucrose, (D) MPG, or (F) NaCl were tested, two-way repeated measures ANOVAs showed a significant main effect of stimulus as detailed in the text. However, the effects of lingual treatment (or interaction) were not significant. These results suggest that LPS must be ingested to inhibit sucrose responses.

Normal taste function maintained in TLR4-deficient mice after LPS consumption

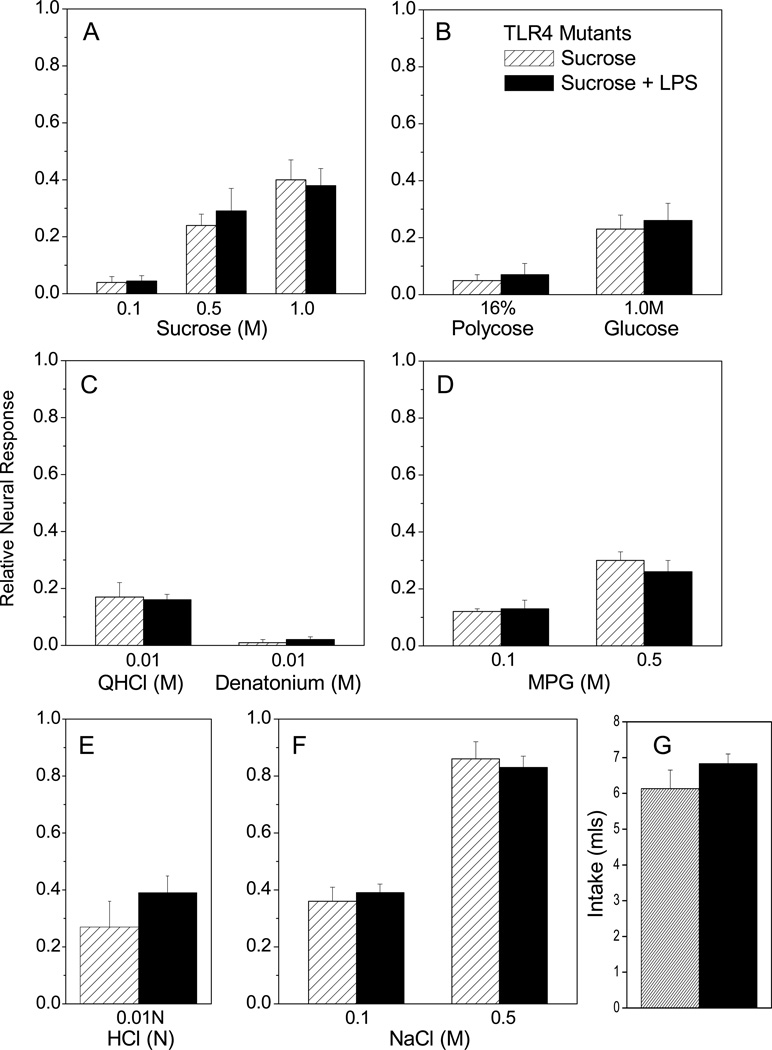

Bacterial LPS signals through the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 pathway. C57BL/10ScN mice have a deletion of the Tlr4 gene that results in absence of both mRNA and protein and thus in defective responses to LPS (Poltorak et al., 2001). We used these mutant mice to determine whether LPS inhibits sucrose responses via TLR4. We chose this mutant strain because it is derived from a sucrose-tasting background strain (B6) rather than a strain (e.g. C3H) with subsensitive CT responses to sucrose (Lush, 1989, Capeless and Whitney, 1995, Bachmanov et al., 1996). C57BL/10ScNJ mutant mice were given access to either LPS in sucrose or sucrose alone. Mutants drank similar amounts of LPS and vehicle (Fig. 7G) as observed in B6 mice (Fig. 3G). There were no main effects of treatment or interaction, though we observed the expected effects of stimulus concentration on CT responses to sucrose [F (2, 15) = 33.36, p < 0.0001], MPG [F (1, 10) = 48.29; p < 0.0001], and NaCl [F (1, 10) = 108.25, p < 0.0001]. Likewise, LPS did not significantly affect responses to single concentrations of polycose, glucose, acid, and bitter stimuli (Fig. 7B, C, E). These results indicate that TLR4 is necessary for LPS inhibition of sucrose responses.

Figure 7.

TLR4 deletion prevents the inhibition of sucrose responses after LPS ingestion. TLR4-deficient mice drank LPS in sucrose (n=6) or sucrose vehicle alone (n=6). CT responses were recorded 7 days later. Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs indicated significant effects of stimulus on nerve responses when multiple concentrations were tested (A, D, F), as described in the text. There were no significant main effects of oral ingestion, or interaction, on CT responses to (A) sucrose, (D) MPG, or (F) NaCl. Responses to single concentrations of (B) polycose, glucose, (C) QHCl, denatonium, and (E) HCl were also similar in TLR4 mutants that drank LPS or vehicle (Student’s t tests). (G) TLR4-deficient mice consumed similar amounts of LPS in sucrose and sucrose vehicle overnight.

LPS decreases sweet taste receptor expression in lingual epithelium

LPS ingestion inhibits responses to sucrose recorded from the CT nerve. Thus, the effects of LPS may ultimately affect transduction genes and proteins in taste receptor cells. We performed qRT-PCR analysis to measure the expression of Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 transcripts, whose products form the T1R2+3 receptor that transduces sweet stimuli (Nelson et al., 2001, Sainz et al., 2001). For comparison, we also analyzed the expression of Tas1r1, whose protein product forms a heterodimer with T1R3, since CT responses to umami stimuli were not significantly affected by treatment (Damak et al., 2003). At day 7, the relative expression of both Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 was significantly reduced in mice that drank LPS compared to controls (Fig. 8A) [F (3, 17) = 23.53; p < 0.001 ]. In contrast, expression levels of Tas1r1 were maintained in LPS-treated mice. By day 14 (Fig. 8B), Tas1 mRNA expression was similar in groups that ingested LPS compared to those drinking vehicle. Thus, transcripts whose proteins mediate sweet transduction in taste receptor cells are transiently downregulated at day 7 after LPS ingestion.

Figure 8.

LPS ingestion reduces the expression of Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 at day 7. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was used to analyze the expression of Tas1r1, Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 mRNA in the anterior lingual epithelium 7 or 14 days after mice drank LPS or sucrose alone. Products of these genes form the T1R1 + T1R3 heterodimer that transduces umami tastants and the T1R2 + T1R3 sweet taste receptor. Expression of Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 (relative to β-actin) was significantly decreased 7 days after mice drank LPS in sucrose (n=6) vs. sucrose alone (n=6; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s posttests [F (3, 8) = 17.12; p = 0.008]). Tas1r1 levels were not significantly changed by LPS ingestion (n=3). Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 mRNA expression was restored to control levels at day 14 (n=3). Mean values from three independent experiments are shown. **p<0.001 Zhu, He and McCluskey

Discussion

We demonstrate that LPS consumption alters taste function via the pattern recognition receptor, TLR4, culminating in the suppression of the sweet taste receptor transcripts Tas1r2 and Tas1r3. Responses to sucrose were specifically inhibited by 50–60% in mice that drank LPS, while responses to other taste modalities were maintained. The effects of LPS were independent of the vehicle used to prompt consumption during a single 15 hour period, and appeared 7 days after exposure. Normal sucrose responses were restored by day 14 after LPS ingestion. Acute experiments demonstrate that LPS applied to the dorsal tongue did not modulate neurophysiological responses to taste stimuli. Instead, endotoxin may initiate changes in the gut-taste axis to alter taste information sent to the CNS.

Post-ingestional effects of LPS on gustatory function

Initial steps linking LPS to changes in sucrose signaling in taste buds likely occur in the gut. First, LPS must be ingested to alter taste function. Mice whose tongues were immersed in LPS solution for 2 hours exhibited normal taste responses 7 days later. Second, pure LPS does not cross the healthy, rat intestinal barrier (Benoit et al., 1998). The intestine is likely healthy in SPF, barrier-housed mice on a standard lab diet, as we used here (Kelly et al., 2012). Ingested LPS is non-toxic even at doses 50X higher than fatal doses of systemic endotoxin (Inagawa et al., 2011), and several mechanisms inactivate or detoxify LPS at the gut mucosa (Kelly et al., 2012). Mice that ingested LPS in the current work also appear to be in good general health, indicated by the absence of sickness behavior and the maintenance of control-like body temperature and weight, though we cannot rule out more subtle effects on systemic immune responses. Third, the inhibition of sweet taste responses are TLR4-dependent, and the LPS-binding complex (i.e. TLR4, MD-2, and CD14) is constitutively expressed in crypt epithelial cells in the stomach, small intestine, and enriched in distal colon (Ortega-Cava et al., 2006, Bogunovic et al., 2007). Though anterior (Shi and McCluskey, 2009) and posterior (Wang et al., 2009) taste buds also express TLR4, experiments limiting LPS exposure to the anterior tongue support a gastrointestinal or post-ingestional component.

Sucrose sensitivity increases during acute CT recordings independently o f lingual LPS treatment

CT responses to sucrose increased over time irrespective of lingual treatment (i.e. LPS or dH2O) in acute experiments. During lengthy recordings, others also report a 10–20% increase in sucrose responses as well as an increased spontaneous activity in rat CT recordings (Beidler and Smallman, 1965). In the current work, approximately one hour separated the first and second presentation of sucrose stimuli. We note that the stability of the recording preparations was monitored with bracketing responses to NH4Cl, and we did not observe consistent signs of deteriorating experimental preparations (e.g. increased noise, decreased signal, or declining baseline). Moreover, classic work demonstrates that CT responses are maintained for 10–12 hours, followed by a decline in responses to all tastants in parallel (Kitada et al., 1984). While the mechanism responsible for increased sucrose responses over time is currently unknown, it is unlikely to result from deterioration or the length of time under anesthesia.

We applied LPS to the anterior tongue to simulate taste bud exposure to bacterially-contaminated water. Though lingual LPS did not acutely alter CT responses, exposure to other TLR4 ligands such as live bacteria or different species of LPS might yield different results. Alternatively, the effects of lingually-applied LPS may occur over several hours or days, rather than minutes (up to ≤ 1 hour) as tested here. For example, proinflammatory cytokine expression is upregulated in circumvallate and foliate epithelia at 6 hours after intraperitoneal LPS (Wang et al., 2007, Cohn et al., 2010). By 1–3 days after LPS injection, fewer newly-born taste receptor cells are present in the taste bud compared to controls (Cohn et al., 2010). Thus, LPS activation of TLR4 can stimulate biological responses in taste buds, though the timing and delivery (i.e. lingual, systemic, or via ingestion) appears to be critical. Downstream responses to lingual (i.e. apical) TLR4 ligands may even be downregulated in taste buds, to avoid hyperactivation by commensal bacteria as suggested in other epithelia (Backhed and Hornef, 2003).

Ingested LPS specifically modulates CT responses to sucrose

Neural responses to sucrose were consistently and selectively vulnerable to LPS consumption through a Tas1r2/3-dependent mechanism. Responses to other modalities, or even to other saccharides and sweeteners, were not significantly altered by LPS ingestion. The maintenance of normal CT responses to polycose after LPS ingestion is anticipated. Aversion to sucrose in rats is not generalized to polycose, which is transduced independently of Tas1r2/3 (Zukerman et al., 2009, Treesukosol and Spector, 2012). The maintenance of normal glucose, saccharin and aceK responses were more surprising given the significant decrease—though not elimination—in Tas1r2/3 expression. One explanation for this selectivity is that CT responses to glucose and sweeteners are maintained by Tas1r2/3-independent pathways. Several lines of evidence support the existence of multiple pathways for sweet stimuli. Though neurophysiological and behavioral responses to sweet stimuli are eliminated in T1R2/3 double knockout mice, T1R2 and T1R3 single knockouts retain residual responses to natural sugars (Damak et al., 2003, Zhao et al., 2003). Indeed, CT responses to glucose are not significantly reduced in T1R3 knockout mice (Damak et al., 2003). Recent work indicates that glucose transporters (e.g. GLUT4) and KATP channels support T1R2 and 3-independent glucose transduction, though this has not been confirmed in vivo (Yee et al., 2011). The existence of multiple, T1 R3-independent sweet pathways is also supported by the differential sensitivity of murine CT sweet responses to temperature and the sweet inhibitor, gurmarin (Ohkuri et al., 2009). We observed a non-significant reduction in CT responses to non-caloric sweeteners after LPS ingestion. Residual responses to sweeteners may have been sustained by bitter or metallic pathways transduced by T2R or TRPV1 receptors, respectively, in addition to T1R2/3 (Kuhn et al., 2004, Riera et al., 2007, Ohkuri et al., 2009, Roudnitzky et al., 2011). Neural responses to umami stimuli are also mediated by multiple receptors, which may account for the normal responses to MPG observed here despite downregulation of Tas1r3 (Damak et al., 2003, Delay et al., 2007, Yasumatsu et al.).

The proximal targets for LPS-induced changes in sweet taste are the Tas1r2/3. These genes were downregulated at 7 days after LPS ingestion in parallel with functional inhibition. Normal taste function and Tas1r2/3 levels were restored by day 14. The maintenance of normal taste responses to glucose and sweeteners suggests that LPS consumption downregulates Tas1r transcripts without killing sweet-sensing taste receptor cells. Indeed, even relatively high doses of systemic LPS have moderate effects on the proliferation and renewal of taste cells (Cohn et al., 2010). Taste receptor cells live for an average of 10–12 days, with lifespans ranging from 2 days to more than 21 days (Beidler and Smallman, 1965, Hendricks et al., 2004, Hamamichi et al., 2006, Cohn et al., 2010, Perea-Martinez et al., 2013). Since normal responses to sucrose were recorded at day 14 post-ingestion, Tas1r2/3 expression may be altered in a single generation of taste receptor cells. Alternatively, LPS may affect a population of long-lived Tas1r2/3-expressing taste receptor cells (or progenitors destined to become sweet-sensing cells) without changing whole nerve responses at day 14. Repeated exposure to LPS may also have more sustained effects on taste function.

Potential mechanisms of communication between gut and peripheral taste system

Endotoxin exposure might be communicated to taste cells by a number of factors, though the downregulation of Tas1r2/3 narrows the list of attractive candidates. Appetite-modulating hormones cholecystokinin (CCK) (Gosnell and Hsiao, 1984, Herness et al., 2002, Simon et al., 2003, Shen et al., 2005), vasoactive intestinal peptide (Shen et al., 2005), neuropeptide Y (Zhao et al., 2005), oxytocin (Sinclair et al., 2010), leptin (Kawai et al., 2000, Shigemura et al., 2004), endocannabinoids (Yoshida et al., 2010), glucagon (Elson et al., 2010), and glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 (Shin et al., 2008) can affect peripheral taste function. Among this group, endocannabinoids, glucagon, and GLP-1 specifically enhance sensitivity to sweet stimuli, contrary to the inhibitory effects on sucrose responses that we observed. Leptin inhibits neural and behavioral responses to sugars and sweeteners in mice in some studies (Kawai et al., 2000, Shigemura et al., 2004). More recently, however, leptin was reported to increase CT responses to sweet stimuli, perhaps due to a warmer stimulus temperature that likely activated transient receptor potential (TRP)M5 temperature-sensitive pathways (Lu et al., 2012). Each of the hormones listed above modulate appetite by acting on distant receptors, including those on subsets of type II sweet-sensitive taste cells or intragemmal afferent fibers (Kawai et al., 2000, Shigemura et al., 2004, Shin et al., 2008, Elson et al., 2010, Yoshida et al., 2010). As such, they offer a putative link between LPS consumption and Tas1r2/3-mediated suppression of sweet taste function. At the same time, we recognize the complexity of potential hormonal and cytokine signaling upstream from Tas1r2/3 mRNA. For example, LPS acutely increases circulating leptin levels in mice and rats via IL-1β (Fantuzzi and Faggioni, 2000), which is constitutively expressed in fungiform taste buds along with the IL-1 receptor (Shi et al., 2012).

Bacterial modulation of the gut-taste axis

Newly-appreciated relationships between gut microbiota and obesity may shed light on mechanisms of communication between ingested LPS and sweet-sensing taste cells. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that endotoxin promotes obesity, particularly when paired with a high-fat diet (Tilg et al., 2009, Cani et al., 2012). Striking new work demonstrates that diet-dependent fecal microbiota can induce obesity, while fecal bacteria from lean mice confer protection against metabolic changes (Ridaura et al., 2013). A particular endotoxin-producing bacterium isolated from an obese patient induced weight gain and insulin resistance in germ-free mice fed a high-fat diet (Fei and Zhao, 2013). Rats maintained on E. coli-supplemented drinking water also have elevated body fat and plasma leptin levels (Karlsson et al., 2011). Intake of exogenous LPS is not limited to experimental models; even “uncontaminated” food typically has 1 ng to 1 µg LPS / gram (Inagawa et al., 2011).

The overlap between sweet signaling mechanisms in the gut and taste system is intriguing, particularly in the context of bacterial exposure (Fernstrom et al., 2012). Germ-free mice, presumably lacking gut bacteria, are resistant to obesity even when fed a high-fat, high-sugar, Western diet (Backhed et al., 2007). Germ-free mice also consume more sucrose in 48 hour two- bottle tests compared to conventionally-raised B6 mice (though preference for sucrose and saccharin remains unchanged) and have elevated levels of intestinal T1R3 and SGLT-1 mRNA and protein (Swartz et al., 2011). Thus, the bacterial load in gut inversely predicts T1R3 expression, similar to our results in the peripheral taste system following LPS consumption. We note, however, that T1R2 and T1R3 expression in circumvallate taste buds was similar in germ-free and conventional mice in that study; T1R2/3 was not examined in anterior taste buds innervated by the chorda tympani nerve (Swartz et al., 2011). Future work must explore chronic vs. acute effects of ingested endotoxin in modulating sweet taste function as well as the role of LPS derived from endogenous vs. exogenous sources.

Gastrointestinal modulation of sweet taste is of significant interest, given the societal impact of obesity and potential for novel regulatory influences on feeding (Sprous and Palmer, 2010, Swithers et al., 2010, Ventura and Mennella, 2011). Systemic LPS induces the well-studied phenomena of sickness behavior (Asarian and Langhans, 2010), which includes anorexia, anhedonia, and taste aversion to sucrose (Cross-Mellor et al., 2004). Little is known about the behavioral consequences of ingested LPS, which is significantly less toxic than systemic LPS (Harper et al., 2011, Inagawa et al., 2011). Inhibiting sweet taste input to the CNS can alter preference for sweet taste stimuli, and ingestion of LPS-tainted solutions may have the same effect (Treesukosol et al., 2011). Regardless of the behavioral outcome, we introduce a new way of modulating the gut-taste axis with ingested endotoxin.

Highlights.

We tested the effect of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on peripheral taste responses

Ingested LPS selectively and transiently inhibited neural responses to sucrose

Neural effects were TLR4 dependent and accompanied by reduced T1R2+3 expression

Limited exposure to a bacterial component alters taste input to the CNS

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Devaki Kumarhia for providing editorial comments on an. earlier version of this manuscript. Supported by National Institutes of Health grant DC005811 to L.P.M.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

References

- Abbas AK, Lichtman AH. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. Saunders; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, Rietschel ET. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides and innate immunity. J Endotoxin Res. 2001;7:167–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarian L, Langhans W. A new look on brain mechanisms of acute illness anorexia. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmanov AA, Reed DR, Tordoff MG, Price RA, Beauchamp GK. Intake of ethanol, sodium chloride, sucrose, citric acid, and quinine hydrochloride solutions by mice: a genetic analysis. Behav Genet. 1996;26:563–573. doi: 10.1007/BF02361229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F, Hornef M. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated signaling by epithelial surfaces: necessity or threat. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:951–959. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:979–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidler LM, Smallman RL. Renewal of cells within taste buds. J Cell Biol. 1965;27:263–272. doi: 10.1083/jcb.27.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit R, Rowe S, Watkins SC, Boyle P, Garrett M, Alber S, Wiener J, Rowe MI, Ford HR. Pure endotoxin does not pass across the intestinal epithelium in vitro. Shock. 1998;10:43–48. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199807000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogunovic M, Dave SH, Tilstra JS, Chang DT, Harpaz N, Xiong H, Mayer LF, Plevy SE. Enteroendocrine cells express functional Toll-like receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1770–G1783. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00249.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Chambon P, de Angelis MH. EMPReSS: standardized phenotype screens for functional annotation of the mouse genome. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1155. doi: 10.1038/ng1105-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani PD, Osto M, Geurts L, Everard A. Involvement of gut microbiota in the development of low-grade inflammation and type 2 diabetes associated with obesity. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:279–288. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capeless CG, Whitney G. The genetic basis of preference for sweet substances among inbred strains of mice: preference ratio phenotypes and the alleles of the Sac and dpa loci. Chem Senses. 1995;20:291–298. doi: 10.1093/chemse/20.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallin MA, McCluskey LP. Lipopolysaccharide-induced up-regulation of activated macrophages in the degenerating taste system. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:75–84. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheal M, Oakley B. Regeneration of fungiform taste buds: temporal and spatial characteristics. J Comp Neurol. 1977;172:609–626. doi: 10.1002/cne.901720405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn ZJ, Kim A, Huang L, Brand J, Wang H. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation attenuates taste progenitor cell proliferation and shortens the life span of taste bud cells. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-Mellor SK, Hoshooley JS, Kavaliers M, Ossenkopp KP. Immune activation paired with intraoral sucrose conditions oral rejection. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2287–2291. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200410050-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damak S, Rong M, Yasumatsu K, Kokrashvili Z, Varadarajan V, Zou S, Jiang P, Ninomiya Y, Margolskee RF. Detection of sweet and umami taste in the absence of taste receptor T1 r3. Science. 2003;301:850–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1087155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilova V, Hellekant G. Comparison of the responses of the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerves to taste stimuli in C57BL/6J mice. BMC Neurosci. 2003;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Bluthe RM, Gheusi G, Cremona S, Laye S, Parnet P, Kelley KW. Molecular basis of sickness behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:132–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delay ER, Mitzelfelt JD, Westburg AM, Gross N, Duran BL, Eschle BK. Comparison of L-monosodium glutamate and L-amino acid taste in rats. Neuroscience. 2007;148:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson AE, Dotson CD, Egan JM, Munger SD. Glucagon signaling modulates sweet taste responsiveness. Faseb J. 2010;24:3960–3969. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-158105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson R. Nontraumatic headholder for mammals. Physiol Beh. 1966;1:97–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzi G, Faggioni R. Leptin in the regulation of immunity, inflammation, and hematopoiesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:437–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei N, Zhao L. An opportunistic pathogen isolated from the gut of an obese human causes obesity in germfree mice. Isme J. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernstrom JD, Munger SD, Sclafani A, de Araujo IE, Roberts A, Molinary S. Mechanisms for sweetness. J Nutr. 2012;142:1134S–1141S. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.149567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell MF, Mistretta CM, Bradley RM. Development of chorda tympani taste responses in rat. J Comp Neurol. 1981;198:37–44. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger TE, Bottger B, Hansen A, Anderson KT, Alimohammadi H, Silver WL. Solitary chemoreceptor cells in the nasal cavity serve as sentinels of respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8981–8986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531172100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon KS, Contreras RJ. Sodium intake linked to amiloride-sensitive gustatory transduction in C57BL/6J and 129/J mice. Physiol Behav. 1995;57:231–239. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00279-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosnell BA, Hsiao S. Effects of cholecystokinin on taste preference and sensitivity in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1984;98:452–460. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.98.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth L. Degeneration and regeneration of taste buds. In: Beidler L, editor. Handbook of sensory physiology. IV. New York: Springer; 1971. pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hamamichi R, Asano-Miyoshi M, Emori Y. Taste bud contains both short-lived and long-lived cell populations. Neuroscience. 2006;141:2129–2138. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper HW, Knight BW. The correct method of signal processing for whole-nerve recordings. Chem Senses. 1987;12:664. [Google Scholar]

- Harper MS, Carpenter C, Klocke DJ, Carlson G, Davis T, Delaney B. E. coli Lipopolysaccharide: acute oral toxicity study in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:1770–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellekant G, Gopal V, Ninomiya Y. Decline and disappearance of taste response after interruption of the chorda tympani proper nerve of the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1979;105:52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1979.tb06313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks SJ, Brunjes PC, Hill DL. Taste bud cell dynamics during normal and sodium-restricted development. J Comp Neurol. 2004;472:173–182. doi: 10.1002/cne.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herness S, Zhao FL, Lu SG, Kaya N, Shen T. Expression and physiological actions of cholecystokinin in rat taste receptor cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10018–10029. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-10018.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DL, Phillips LM. Functional plasticity of regenerated and intact taste receptors in adult rats unmasked by dietary sodium restriction. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2904–2910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02904.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DJ, Choi HB, Hines RM, Phillips AG, MacVicar BA. Prevention of LPS-induced microglia activation, cytokine production and sickness behavior with TLR4 receptor interfering peptides. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagawa H, Kohchi C, Soma G. Oral administration of lipopolysaccharides for the prevention of various diseases: benefit and usefulness. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:2431–2436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K, Sato M. Neural and behavioral responses to taste stimuli in the mouse. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:803–807. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson CL, Molin G, Fak F, Johansson Hagslatt ML, Jakesevic M, Hakansson A, Jeppsson B, Westrom B, Ahrne S. Effects on weight gain and gut microbiota in rats given bacterial supplements and a high-energy-dense diet from fetal life through to 6 months of age. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:887–895. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Sugimoto K, Nakashima K, Miura H, Ninomiya Y. Leptin as a modulator of sweet taste sensitivities in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11044–11049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190066697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CJ, Colgan SP, Frank DN. Of microbes and meals: the health consequences of dietary endotoxemia. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:215–225. doi: 10.1177/0884533611434934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada Y, Bradley RM, Mistretta CM. Maintenance of chorda tympani salt taste responses after nerve transection in rats. Brain Res. 1984;302:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn C, Bufe B, Winnig M, Hofmann T, Frank O, Behrens M, Lewtschenko T, Slack JP, Ward CD, Meyerhof W. Bitter taste receptors for saccharin and acesulfame K. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10260–10265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1225-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Staszewski L, Xu H, Durick K, Zoller M, Adler E. Human receptors for sweet and umami taste. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4692–4696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072090199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberles SD, Horowitz LF, Kuang D, Contos JJ, Wilson KL, Siltberg-Liberles J, Liberles DA, Buck LB. Formyl peptide receptors are candidate chemosensory receptors in the vomeronasal organ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9842–9847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904464106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Breza JM, Nikonov AA, Paedae AB, Contreras RJ. Leptin increases temperature-dependent chorda tympani nerve responses to sucrose in mice. Physiol Behav. 2012;107:533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lush IE. The genetics of tasting in mice. VI. Saccharin, acesulfame, dulcin and sucrose. Genet Res. 1989;53:95–99. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300027968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey LP. Up-regulation of activated macrophages in response to degeneration in the taste system: effects of dietary sodium restriction. J Comp Neurol. 2004;479:43–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistretta CM, Bradley RM. Neural basis of developing salt taste sensation: response changes in fetal, postnatal, and adult sheep. J Comp Neurol. 1983;215:199–210. doi: 10.1002/cne.902150207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Zhang Y, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell. 2001;106:381–390. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuri T, Yasumatsu K, Horio N, Jyotaki M, Margolskee RF, Ninomiya Y. Multiple sweet receptors and transduction pathways revealed in knockout mice by temperature dependence and gurmarin sensitivity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R960–R971. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91018.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead J. Effects of cutting the lingual nerve of the dog. J Comp Neurol. 1921;33:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Cava CF, Ishihara S, Rumi MA, Aziz MM, Kazumori H, Yuki T, Mishima Y, Moriyama I, Kadota C, Oshima N, Amano Y, Kadowaki Y, Ishimura N, Kinoshita Y. Epithelial toll-like receptor 5 is constitutively localized in the mouse cecum and exhibits distinctive down-regulation during experimental colitis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:132–138. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.1.132-138.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea-Martinez I, Nagai T, Chaudhari N. Functional cell types in taste buds have distinct longevities. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffman C. Gustatory nerve impulses in rat, cat and rabbit. J Neurophysiol. 1955;18:429–440. doi: 10.1152/jn.1955.18.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LM, Hill DL. Novel regulation of peripheral gustatory function by the immune system. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R857–R862. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.4.R857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raetz CR, Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Cheng J, Duncan AE, Kau AL, Griffin NW, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Ilkayeva O, Semenkovvich CF, Funai K, Hayashi DK, Lyle BJ, Martini MC, Ursell LK, Clemente JC, Van Treuren WV, Walters WA, Knight R, Newgard CB, Heath AC, Gordon JI. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341:1241214. doi: 10.1126/science.1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riera CE, Vogel H, Simon SA, le Coutre J. Artificial sweeteners and salts producing a metallic taste sensation activate TRPV1 receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R626–R634. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00286.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere S, Challet L, Fluegge D, Spehr M, Rodriguez I. Formyl peptide receptor-like proteins are a novel family of vomeronasal chemosensors. Nature. 2009;459:574–577. doi: 10.1038/nature08029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudnitzky N, Bufe B, Thalmann S, Kuhn C, Gunn HC, Xing C, Crider BP, Behrens M, Meyerhof W, Wooding SP. Genomic, genetic and functional dissection of bitter taste responses to artificial sweeteners. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3437–3449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainz E, Korley JN, Battey JF, Sullivan SL. Identification of a novel member of the T1R family of putative taste receptors. J Neurochem. 2001;77:896–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomao R, Brunialti MK, Rapozo MM, Baggio-Zappia GL, Galanos C, Freudenberg M. Bacterial sensing, cell signaling, and modulation of the immune response during sepsis. Shock. 2012;38:227–242. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318262c4b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen T, Kaya N, Zhao FL, Lu SG, Cao Y, Herness S. Co-expression patterns of the neuropeptides vasoactive intestinal peptide and cholecystokinin with the transduction molecules alpha-gustducin and T1R2 in rat taste receptor cells. Neuroscience. 2005;130:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, He L, Sarvepalli P, McCluskey LP. Functional role for interleukin-1 in the injured peripheral taste system. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:816–830. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, McCluskey L. Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 expression in taste receptor cells: A potential mechanism for pathogen recognition (Abstract) Society for Neuroscience. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Shigemura N, Nakao K, Yasuo T, Murata Y, Yasumatsu K, Nakashima A, Katsukawa H, Sako N, Ninomiya Y. Gurmarin sensitivity of sweet taste responses is associated with co-expression patterns of T1 r2, T1r3, and gustducin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemura N, Ohta R, Kusakabe Y, Miura H, Hino A, Koyano K, Nakashima K, Ninomiya Y. Leptin modulates behavioral responses to sweet substances by influencing peripheral taste structures. Endocrinology. 2004;145:839–847. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin YK, Martin B, Golden E, Dotson CD, Maudsley S, Kim W, Jang HJ, Mattson MP, Drucker DJ, Egan JM, Munger SD. Modulation of taste sensitivity by GLP-1 signaling. J Neurochem. 2008;106:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingai T, Beidler LM. Response characteristics of three taste nerves in mice. Brain Res. 1985;335:245–249. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90476-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SA, Liu L, Erickson RP. Neuropeptides modulate rat chorda tympani responses. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R1494–R1505. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00544.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair MS, Perea-Martinez I, Dvoryanchikov G, Yoshida M, Nishimori K, Roper SD, Chaudhari N. Oxytocin signaling in mouse taste buds. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprous D, Palmer KR. The T1R2/T1R3 sweet receptor and TRPM5 ion channel taste targets with therapeutic potential. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2010;91:151–208. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(10)91006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen PW, Shi L, He L, McCluskey LP. Neutrophil responses to injury or inflammation impair peripheral gustatory function. Neuroscience. 2010;167:894–908. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz TD, Duca FA, de Wouters T, Sakar Y, Covasa M. Up-regulation of intestinal type 1 taste receptor 3 and sodium glucose luminal transporter-1 expression and increased sucrose intake in mice lacking gut microbiota. Br J Nutr. 2011;107:621–630. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swithers SE, Martin AA, Davidson TL. High-intensity sweeteners and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilg H, Moschen AR, Kaser A. Obesity and the microbiota. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1476–1483. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizzano M, Gulbransen BD, Vandenbeuch A, Clapp TR, Herman JP, Sibhatu HM, Churchill ME, Silver WL, Kinnamon SC, Finger TE. Nasal chemosensory cells use bitter taste signaling to detect irritants and bacterial signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3210–3215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911934107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treesukosol Y, Smith KR, Spector AC. The functional role of the T1R family of receptors in sweet taste and feeding. Physiol Behav. 2011;105:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treesukosol Y, Spector AC. Orosensory detection of sucrose, maltose, and glucose is severely impaired in mice lacking T1R2 or T1R3, but Polycose sensitivity remains relatively normal. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R218–R235. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00089.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura AK, Mennella JA. Innate and learned preferences for sweet taste during childhood. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14:379–384. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328346df65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall PL, McCluskey LP. Rapid changes in gustatory function induced by contralateral nerve injury and sodium depletion. Chem Senses. 2008;33:125–135. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhou M, Brand J, Huang L. Inflammation activates the interferon signaling pathways in taste bud cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10703–10713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3102-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhou M, Brand J, Huang L. Inflammation and taste disorders: mechanisms in taste buds. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:596–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasumatsu K, Ogiwara Y, Takai S, Yoshida R, Iwatsuki K, Torii K, Margolskee RF, Ninomiya Y. Umami taste in mice uses multiple receptors and transduction pathways. J Physiol. 2012;590:1155–1170. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.211920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee KK, Sukumaran SK, Kotha R, Gilbertson TA, Margolskee RF. Glucose transporters and ATP-gated K+ (KATP) metabolic sensors are present in type 1 taste receptor 3 (T1r3)-expressing taste cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5431–5436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100495108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida R, Ohkuri T, Jyotaki M, Yasuo T, Horio N, Yasumatsu K, Sanematsu K, Shigemura N, Yamamoto T, Margolskee RF, Ninomiya Y. Endocannabinoids selectively enhance sweet taste. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:935–939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912048107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao FL, Shen T, Kaya N, Lu SG, Cao Y, Herness S. Expression, physiological action, and coexpression patterns of neuropeptide Y in rat taste-bud cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11100–11105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501988102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao GQ, Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Erlenbach I, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell. 2003;115:255–266. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zukerman S, Glendinning JI, Margolskee RF, Sclafani A. T1R3 taste receptor is critical for sucrose but not Polycose taste. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R866–R876. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90870.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]