Abstract

Background:

Patients’ compliance to treatment is an important indicator for evaluating the successful management in chronic illnesses. Despite the fact an applicable definition of compliance is required to suitable intervention and research, this concept is not clear and there is no consensus concerning its meaning, definition, and measurement. The aim of this study was to explore the concept of compliance and to formulate a working definition.

Materials and Methods:

Theoretical phase of Schwartz-Barcott and Kim's Hybrid Model of concept analysis was used to analyze the concept of compliance. Data were collected by using literature reviews. Medline, CINAHL, Ovid, Elsevier, Pro Quest and Blackwell databases were searched from 1975 to 2010 using the keywords “Compliance,” “Non-compliance,” “Adherence,” and “Concordance.” Articles published in English were selected if they included adult patients with chronic illnesses and reported attributes of compliance; 23 such relevant articles were chosen.

Results:

The attributes of compliance included patient obedience, ability to implement medical advice, flexibility, responsibility, collaboration, participation, and persistence in implementing the advices. Antecedents are organized into two interacting categories: Internal factors refer to the patient, disease, and treatment characteristics and external factors refer to the healthcare professionals, healthcare system, and socioeconomic factors. Compliance may lead to desirable and undesirable consequences. A working definition of compliance was formulated by comparing and contrasting the existing definitions with regard to its attributes which are useful in clinical practice and research.

Conclusions:

This finding will be useful in clinical practice and research. But this working definition has to be tested in a clinical context and a broad view of its applicability has to be obtained.

Keywords: Adherence, chronic illness, compliance, concept analysis, hybrid model

INTRODUCTION

Chronic illness is a condition that requires compliance to treatment for the illness to be under control. When a chronic illness is inadequately managed, the condition may worsen.[1] Chronic illnesses are the first significant cause of mortality in the world, accounting for 60% of all deaths worldwide and 70% of all deaths in Iran.[2,3] Non-compliance can lead to unmet treatment expectations. In developed countries, approximately 50% of the patients with chronic illnesses follow treatment. In developing countries, poor compliance threatens to render any efforts to manage chronic conditions ineffective.[4] Average rates of compliance in patients with chronic illnesses are from 0 to 100%.[5,6,7,8,9] In Iran, the rate of compliance has been reported to be between 12.7 and 86.3%.[10,11,12,13] Promotion of compliance is one way to prevent worrisome consequences to enhance patients’ quality of life and concurrently to reduce costs on medical treatment.[14]

To improve compliance, it is essential to understand the meaning of compliance.[15] However, this term is not clearly defined in the literature, and therefore, there is no completely reliable and valid method for measuring compliance.[16]

Research on compliance has been performed from 1950, but it is still an important issue in patients with chronic illness. Marston (1970) remarked that it was deceiving to compare the rate of compliance from disparate research finding because of its multifarious working definitions.[17,18] Furthermore, there is an increased criticism of studies that measure compliance without a consensual definition.[6,19,20,21,22]

Besides, there are many terms referring to “compliance” as “adherence” and “concordance,” but no consensus on a unified definition for each term to differentiate between these terms.[14,22,23]

To improve the compliance of patients, it is fundamental to facilitate the measurement and comprehensive understanding of compliance. Appraising the literature surrounding compliance is required to ensure that the existing definition represents all attributes of compliance, considering patients’ and healthcare professionals’ consolidation perception on treatment.[24] A better design to present unambiguous and comprehensive working definitions of compliance is the Hybrid Model concept analysis. The aim of this study was to explore and define the concept of compliance and to formulate a working definition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Hybrid Model concept analysis was used as presented by Schwartz-Barcott and Kim (1993), which amalgamates theoretical and empirical analysis and is specifically beneficial when exploring a known concept in a new context or when trying to find out new distinctive attribute of it.[25] The model includes three phases: First, in the theoretical phase, data are collected by using literature reviews to develop a foundation for the second phase. Second, in the fieldwork phase, qualitative data are obtained through semi-structured interviews to refine a concept of compliance. Third, in the analytical phase, the concept application and its importance is justified after integration of the data gained during this phase.[25,26] In this study, the theoretical phase is presented which involves selecting a concept, searching the literature, dealing with meaning and measurement, and identifying a working definition for the fieldwork phase.[25]

Selecting a concept

The selection of a concept for study has been approached in various ways.[25,26] In this study, compliance was selected from the clinical experiences of a researcher who had encountered worsened medical outcomes of patients’ non-compliant behaviors such as suffering from disease side effects and disease complication, or increase in the rate of rehospitalization and readmission in the emergency department. Despite this, healthcare professionals made few efforts to understand the cause of the patients’ behaviors. In such situations, both professionals and patients blamed each other, which not only will fail to improve the situation, but may even intensify the problem. It is time to cease focusing on patient non-compliance behaviors and focus the issue as a whole by exploring the meaning of compliance. These reasons encouraged us to select “compliance” in this concept development.

Searching the literature

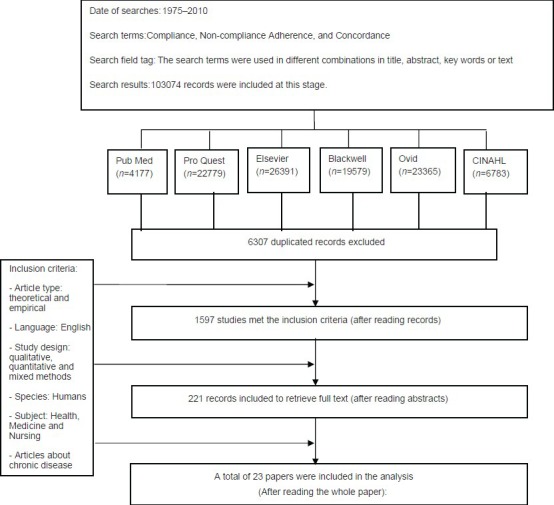

Schwartz-Barcott and Kim (1993) emphasized the extensive need to review the literature. However, it is important to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the comparable definitions to generate a tentative definition which is extracted from the literature. A broad systematic search of the literature was conducted. The literature was reviewed by focusing on the central questions of definition and measurement. The questions posed by Schwartz-Barcott and Kim (1995) guided the inquiry into the literature for providing an initial direction of this search.[25] The source of the data was all types of published articles. A literature search was undertaken through the available resources including Medline, CINAHL, Ovid, Elsevier, Pro Quest, and Blackwell databases. The databases were searched between 1975 and 2010 using the keywords of “Compliance,” “Non-compliance,” “Adherence,” and “Concordance,” and taking into consideration the inclusion criteria and availability of abstract [Figure 1]. The search results were imported into the EndNote software for storage and organization.

Figure 1.

The retrieval and selection process of articles in the literature review process

The literature was reviewed through the following steps:

The search results were evaluated to discard duplicated records

The remaining records (96,767) were assessed to choose the relevant abstracts

The abstracts (1597) were selected for entry to retrieve the pertinent full texts

The selected full texts (221) were appraised.

The relevant full texts were chosen one by one, and all references of retrieved articles were manually reviewed. Articles were retrieved if the title included compliance as a key component within the article. Finally, 23 relevant retrieved articles were reviewed [Table 1]. The analysis began with reading the articles carefully several times. The process of data extraction continued until there were no new data in the articles.

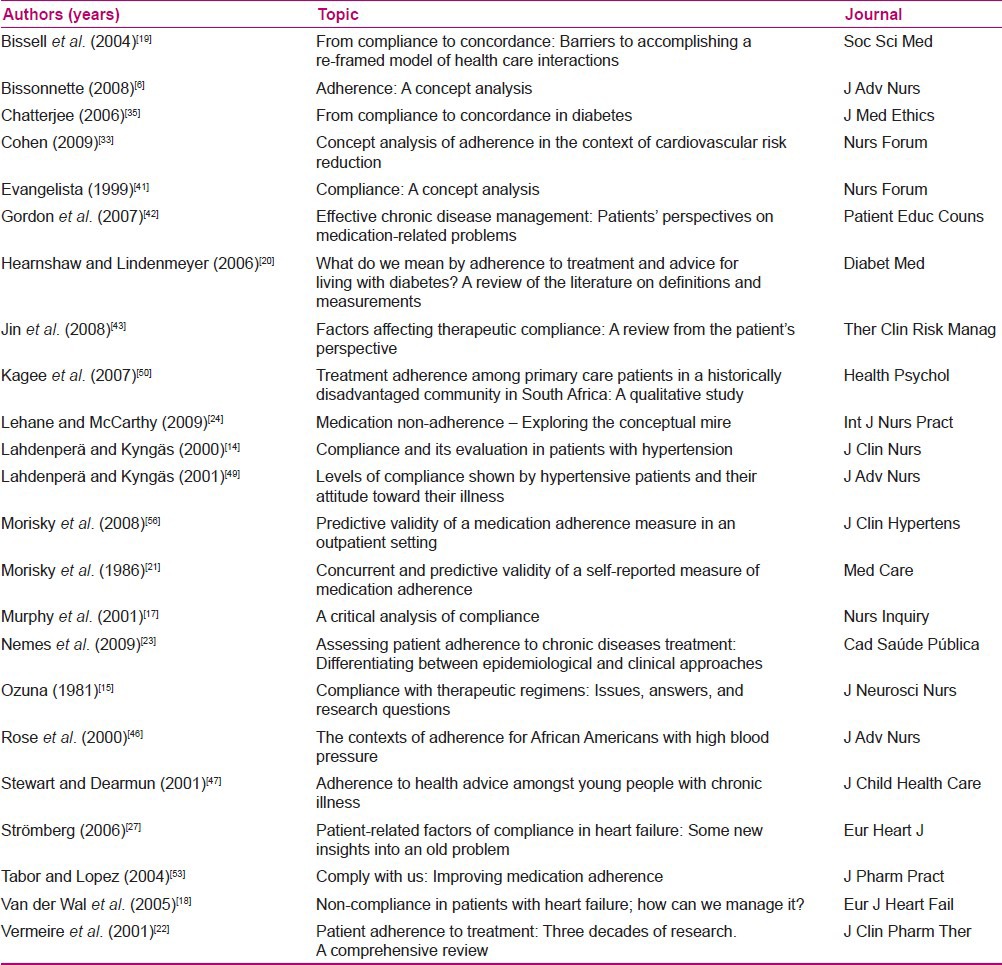

Table 1.

Studies reviewed for data extraction (N=23)

Dealing with meaning and measurement

Once the definitions are available, it is useful to search for main points of disparity and similarity, as this type of comparison provides the investigator with some ideas of the degree of consensus among users of a particular concept and leads to an understanding of the degree of inter-subjectivity of meaning.[25] In this step, retrieved articles were read carefully several times, and definition and measurement were extracted.

Choosing a working definition

Once the main points of similarity and dissimilarity among existing definitions and between these points and one's initial definition become obvious, a definition is chosen or created for more detailed investigation.[25] In this study, the analysis of articles was conducted in several steps. First, the extracted data were analyzed by organizing the content of the data with regard to the definitions, antecedents, attributes, consequences, and measurement of compliance. Second, these articles were examined to find implicit definitions and attributes. Subsequently, articles were searched for major points of contrasts and similarities between definitions. Finally, a working definition with further necessary or appropriate details was generated.

RESULTS

The results are presented under the headings of definition, measurement, and working definition.

Definition

Despite the abundance of research in this area, most authors used the term “compliance,” but did not define it. The researchers were urged to make this a priority in the 1970s. The fact that how people with chronic condition act in accordance with prescribed treatment was at first introduced as compliance.[27] Compliance was defined by Sackett and Haynes (1976) as “the extent to which a person's behavior in terms of taking medications, following diets or executing lifestyle changes coincides with medical or health advice.”[24,28,29] However, not all researchers agreed with this definition used in their research. McGann (1999) quoted the definition, but continues it with this expression, “this definition fails to notice the ways in which a recommended advice influences patients’ life and gives the healthcare professional the role of master.”

In the field of nursing, some researchers stated that compliance is realized as more than following behavior or just compliance with healthcare professionals’ recommendations.[30] They emphasized on patients’ activity and responsibility in the process of treatment, in which the patients act in close cooperation with the healthcare professionals for maintaining their health.[17] Later, some researchers criticized “compliance” for indicating paternalism. The care plan is dictated by healthcare professionals and the patients as obedience should follow them. Adherence and concordance were then suggested to replace compliance as surrogate terms.

Adherence emphasizes on the relationship between patients and healthcare professionals with respect and mutual cooperation. The old definitions have been revised to give the current definition for “adherence” by the World Health Organization.[9] However, researchers used “compliance” broadly, but often with the identical underlying definition as “adherence,” and they used these terms interchangeably with identical definitions in some cases.[27] In spite of consistency across health disciplines in regard to the importance of the phenomenon of adherence, the definition of this concept is still vague and arguable.[1,9,17,19,22,31] Adherence is also described as the extent to which the patients comply with the agreed prescribed regimen. But compliance points to the extent to which the patient complies with the recommendations of the healthcare professionals, which are not invariably agreed upon by the patient.[20]

Recently, another term “concordance” is being used. It is defined as “the process of enlightened communication, which leads to an agreed treatment.” The compatible relationship between healthcare professionals and patients leads to a partnership in treatment that is in keeping with the patients’ desires and ability.[32,33] While compliance and adherence both comply with specific behaviors, concordance complies with the process of consultation resulting in healthcare professionals–patient agreement.[20]

Although compliance research is varied based on how the term has been defined and measured, there is argument over the application of all these terms: Compliance, adherence, and concordance, which are used interchangeably.[20,22,34]

In order to explore and gain a broader understanding of compliance, the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of compliance were identified and are described below.

Attributes

Some attributes of compliance were recognized in the literature reports which provided adequate and sufficient information on the subject.

The word compliance suggests that patients obey or acquiesce the recommendations of healthcare professionals; it just indicates alignment to the specific medical goals[28] and patients should endure to healthcare professionals’ authority and obey orders passively as powerless recipients of care, by virtue of enforcing the determination and intention of another.[32,35,36] Evangelista (1999) assigned the attributes of compliance and labeled them as the following categories: “Ability to carry out medical advice, flexibility, adaptability, and subordinate behaviors.” However, some authors focused on “an active responsible act of care” in which patients act to improve health in close cooperation with the healthcare professionals, as a substitute for obeying orders passively.[17,33]

The term adherence captures the increasing complexity of medical care by characterizing the extent to which patients follow set goals for their medical treatment.[28]

Despite the fact that both adherence and compliance have implicit meaning of power imbalance and medical paternalism, most of the researchers prefer “adherence” in contrast to “compliance.” The researchers considered patients’ behavior as adherent if they did what the healthcare professionals suggested.[37] In addition, adherence indicates an active participation to follow a prescribed regimen, cooperation, and perseverance in practice, and retain healthier behavior.[32,35,38,39]

Antecedents

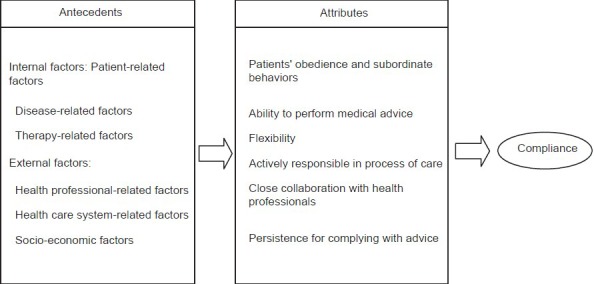

In this study, antecedents are those events that should have occurred before compliance, which is divided into two categories [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Antecedents and defining attributes of compliance

Internal factors describe how the patients’ characteristics, the disease, and treatments affected their compliance to treatment.

There are some factors may affect on patients compliance such as demographic (e.g. age and gender) psychological, disease and treatment related factors. Psychological factors refer to health beliefs about meaning of illness, lack of knowledge or misconceptions about treatment, religious beliefs that deem that disease is God's will, concerns about developing dependence on drugs, negative attitude toward treatment (e.g. anger about illness or feeling of stigmatization), patients’ expectancies of health and treatment, patients’ motivation and satisfaction to the treatment, and patients’ communication and coping method.[6,35,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]

The features of disease that are discerned as the effective factors on compliance are length of illness, disease intensity, the number of complications, the degree of disability, and the symptoms (symptomless, lack of symptoms, or temporary absence of symptoms, and the rate of undesirable symptoms).[6,22,43,44,49]

Furthermore, treatment-related factors can exert an effect on compliance, including the nature of treatment; convenience and practical way of administration (oral, inhalation, or injection medication); duration (long- or short-term therapy); the number, dose, and frequency of medication; the cost of dealing with therapy (purchase of medication, special diet, medical equipment, and transportation to attend appointments); complexity of treatment (rigid, inflexible, unachievable, and unattractive advice); ineffective treatment; length and quantity of change imposed by the treatment; and an unspecified time span of treatment.[22,42,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,50]

External factors describe how compliance is affected by healthcare professionals’ behavior, healthcare system, and socioeconomic factors.

To date, researchers have determined healthcare professionals’ characteristics as the important factors that influence compliance, such as communication approaches (quality, duration, and frequency of communication, and giving reassurance, respect, and empathy), emotional support, cooperative behavior, clinical competency (e.g. monitoring and providing feedback, providing definite and understandable instructions, giving reason for behavioral change required, creating a connection between treatment and patients’ attitudes and beliefs, enhancement of patient-centered therapy), and incongruence of advice from other healthcare professionals.[6,22,35,40,41,42,43,44,45,47,50,51]

Furthermore, there is an abundance of research that explores some factors related to healthcare system that have an impact on compliance, such as access to available health facility and organization of services, convenience of healthcare settings, administrative errors, design and delivery of programs, lack of institutional support, patient satisfaction with care, lack of programs to resolve the challenges of self-care, access to appropriate resources, the quality of the referral process, the available systems for information transfer between different parts of the health service, and the available appropriate systems to inform patients about their medicines.[22,42,46,47,50,51]

In addition, socioeconomic factors such as income, insurance coverage, and social, emotional, and financial support are very important to patients for applying and maintaining the prescribed treatment.[6,40,44,41,42,43,44,45,46,52]

Consequences

In this study, consequences are those events that occur as a result of the occurrence of compliance. The desired consequences of compliance include reducing symptoms, complications of disease, complexity of the treatment, mortality, hospitalization and emergency room visit rates, and wasted medication. Compliance may lead to increased life expectancy and improved morbidity, empowerment, a sense of mastery, self-confidence, ability to cope, satisfaction, and improvement in quality of life, and in turn, shorten costs to the healthcare service and, as a result, to national economies,[6,9,17,18,20,45,51,53,54] even though some undesirable consequences such as dependence and lack of control or powerlessness can be expected. If patients feel incapable to control their own life, helplessness and patients’ dependency may occur which can have an effect on patient satisfaction and, hence, quality of life.[41]

Measurement

Since research on compliance has diversified according to how it has been defined and measured, there are discussions about the usage of these mentioned terms: Compliance, adherence, and concordance.[20,22,34] Valid definition and methods for measuring the efficacy of such interventions on compliance are necessary and crucial.[20]

Historically, the concept compliance has been referred to the behaviors of patients. Sackett and Haynes (1979) presented the construction of compliance that facilitated the measurement of patients’ behavior based on healthcare recommendations.[55] Some researchers measured health professionals’ competence to distinguish non-compliant patients and found that they were precise in determining compliance in just 10% of the patients.[6]

Researchers became more interested in developing objective measures of compliance, including patient self-report questionnaires, pill counts, electronic monitoring devices, prescription record reviews, measurement of medicine metabolites in the blood, and outcome measures of specific disease-related symptoms. The most commonly used method, pill counts, did not prove to be a reliable indicator because of multiple pharmacies in which each patient obtained prescription refills and, also, other prescribed treatments such as diet and lifestyle changes were ignored. Chemical tests were neither reasonable nor affordable or convenient for all the medications.[6,18,21,31]

Nevertheless, patients’ self-reports are considered a reliable method; most researchers use the 4-item Morisky scale frequently, which has failed to determine a valid measurement. This is due to the fact that each item assesses a single behavior for taking medication and it cannot determine the compliance behavior overall.[37,56]

As a result, there is no suitable standardized self-reporting instrument, and researchers have measured a special aspect of compliance or specific medications, which are deliberated based on their research purpose. This issue is affecting the reported rate of compliance. Compliance measurement should be according to a clear, valid, and acceptable definition, and it is essential to determine the extent of the patient's behavior that coincides with the prescribed treatment. In addition, the ponderous aspect in assessing compliance is the identification of patients with non-compliant or compliant behavior or the classification of patients in arbitrary categories such as “recalcitrant,” “careless,” or “irresponsible.” Without regard for the method that researchers applied to measure compliance, they should provide the definition of compliance clearly, develop a valid method of measurement, and subsequently allocate patients into varied classification.[14,22,23]

This means that compliance and its related concept will be evaluated in a continuous sequence in which adjacent elements are not perceptibly different from each other, but the extremes are quite distinctly based on the extent of the patients’ participation in their treatment. Compliance will be located at one end of a continuum of participation in a treatment program on the basis of the degree to which the patient is involved in treatment regimen planning for therapeutic goal attainment. The opposite end point is occupied by the concept of concordance and the approximate midpoint by the concept of adherence, but there is no exact border to differentiate between them.

The working definition

As a result, a working definition of compliance was formulated by comparing and contrasting the existing definitions with the researcher's tentative definition: “Compliance is an intentional and responsible process of care in dyad level, in which patients and healthcare professionals make efforts to achieve mutually derived health goals collaboratively.” It means that compliance leads to changes and maintenance of desired health behavior and incorporates these factors as part of the patients’ daily life. These changed behaviors are congruent with professional advice, which are consultative, capable of achieving, and context based.

DISCUSSION

This concept analysis process was a difficult work for which there is not enough data for entry in the analysis. Despite numerous published articles, most of the researchers used the term “compliance,” but did not define it. Murphy and Canales (2001) critiqued 60 nursing articles and reported that less than half of the articles (25 vs. 60) which they included in their analysis defined “compliance.” Besides, the literature lacks a definition of compliance as a distinct concept from surrogates. In addition, most authors refer to the same definition provided by Sackett and Haynes (1976), even in some cases where this definition was used for both compliance and adherence. Moreover, the term “adherence” was used interchangeably with the same underlying definition; attributes of both compliance and adherence were considered as results of the current study.

The results of this study provide insights into compliance of patients with chronic illnesses. Although previous studies have suggested some components of compliance, the concept of compliance is wider than compliance solely with medication, while many of the most prevalent chronic illnesses entail a significant “treatment compliance” component, often including medication, diet, clinic attendance, and changes in lifestyle with specific illness-related behaviors.[5,6,8,14,18,22,35,43,44,49,57]

The results of our concept analysis revealed that patients with chronic illnesses who do not follow the prescribed treatment are not a homogenous group, and many different and interacting external and internal factors can affect compliance behaviors, because this phenomenon is multi-dimensional and reciprocal action of dimensions can exert significant effect on patients’ compliance behaviors. That means it is not the patients’ responsibility alone to act in accordance with healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals should be aware that different suitable approaches should be developed to ensure that all patients with chronic illnesses are able to accept their advice that may be required to promote patient compliance.

According to the results, we suggest that the phenomenon could be described as attention focused on actual, practical, or anticipated compliance. This study has also clarified some of the misunderstood issues in relation to the patient's rights. It revealed that some opposite implicit meaning in the attributes of compliance, such as patient activity and responsibility in care, can refer to freedom of choice, in contrast to subordinate and passive obedience, which demonstrates an imbalance of power and healthcare dominance. On the other hand, ethical dilemmas ensue when patients are incompetent to make a goal-directed option and may have to be delayed in treatment.[35]

The imbalance of power between patients and healthcare professionals is another questionable issue and can be resolved by focusing on “intentional, collaborative and responsible process of care in dyad level” as described in the purposed working definition.

In summation, ambiguity in compliance definition occurred when the researcher tried to emphasize theoretical differences in definition and yet overlooked them in practice. We need to relinquish certain restrictions of the theoretical definition, rather than exerting it practically. The researchers and clinicians must agree upon the criteria that determine the complying behavior of patients, and for assessing the compliance, they have to consider both the patients’ behavior to follow the advices and the outcome of treatment.

CONCLUSION

The finding can give an insight to researchers to clarify the definition of compliance before designing the research. Hence, the finding may help healthcare professionals to understand the process of compliance which is important to improve patients’ compliance behaviors in all aspects of treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This manuscript is a part of PhD dissertation that was approved by Tehran University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: Nil

REFERENCES

- 1.Dunbar-Jacob J, Mortimer-Stephens MK. Treatment adherence in chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:S57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Chronic diseases and health promotion. [Last accessed on 2012 May 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en .

- 3.Solaymani M. Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2010. Participation of Patients with Chronic Illness in Nursing Care: Presentation of Model. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelsson M, Brink E, Lundgren J, Lötvall J. The influence of personality traits on reported adherence to medication in individuals with chronic disease: An epidemiological study in West Sweden. PloS One. 2011;6:e18241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andal E. Compliance: Helping patients help themselves. Clin Rev. 2006;116:23–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissonnette J. Adherence: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63:634–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haynes RB, Yoa X, Degani A, Kripalani S, Garg A, McDonald HP. Interventions to enhance medication adherence (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:1–77. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kärner A, Göransson A, Bergdahl B. Conceptions on treatment and lifestyle in patients with coronary heart disease-a phenomenographic analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:137–43. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabate E. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action 2003; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbasi M, Salem IS, Seyed Fatemi N, Hosseini F. Hypertensive patients, their compliance level and its relation to their health beliefs. IJN. 2005;18:61–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadi N, Rostami Gouran N, Jafari P. A Study on The Determining Factors for Compliance to Prescribed Medication by Patients with High Blood Pressure. Sci Med J. 2005;4:223–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashemdabaghian F, Karbakhsh M, Soheilikhah S, Sedaghat M. Drug Compliance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Shariati and Imam Khomeini Hospitals. PAYESH. 2005;4:103–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsa-Yekta Z, Zakeri Moghaddam M, Mehran A, Palizdar M. Study of medication compliance of patients with coronary heart diseases and associated factors. J Qazvin Univ Med Sci. 2003;9:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lahdenperä TS, Kyngäs HA. Compliance and its evaluation in patients with hypertension. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9:826–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozuna J. Compliance with Therapeutic Regimens: Issues, Answers, and Research Questions. J Neurosci Nurs. 1981;13:1–6. doi: 10.1097/01376517-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyngäs H, Duffy ME, Kroll T. Conceptual analysis of compliance. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9:5–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy N, Canales MA. critical analysis of compliance. Nurs Inquiry. 2001;8:173–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Wal MH, Jaarsma T, van Veldhuisen DJ. Non-compliance in patients with heart failure; how can we manage it? Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bissell P, May CR, Noyce PR. From compliance to concordance: Barriers to accomplishing a re-framed model of health care interactions. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:851–62. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hearnshaw H, Lindenmeyer A. What do we mean by adherence to treatment and advice for living with diabetes? A review of the literature on definitions and measurements. Diabet Med. 2006;23:720–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and Predictive Validity of a Self-reported Measure of Medication Adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: Three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26:331–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nemes MI, Helena ET, Caraciolo JM, Basso CR. Assessing patient adherence to chronic diseases treatment: Differentiating between epidemiological and clinical approaches. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009;25(Suppl 3):S392–400. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009001500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehane E, McCarthy G. Medication non-adherence-exploring the conceptual mire. Int J Nurs Pract. 2009;15:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2008.01722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodgers BL, Knafl KA. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000. Concept analysis in nursing: Foundation, techniques, and application. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz-Barcott D, Patterson BJ, Lusardi P. From practice to theory: Tightening the link via three fieldwork strategies. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39:281–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strömberg A. Patient-related factors of compliance in heart failure: Some new insights into an old problem. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:379–81. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lutfey KE, Wishner WJ. Beyond “compliance” is “adherence”. Improving the prospect of diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:635–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGann E, Sexton D, Chyun D. Denial and Compliance in Adults With Asthma. Clin Nurs Res. 2008;17:151. doi: 10.1177/1054773808320273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hentinen M, Kyngäs H. Diabetic adolescents’ compliance with health regimens and associated factors. Int J Nurs Stud. 1996;33:325–37. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(95)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther. 1999;21:1074–90. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treharne GJ, Lyons AC, Hale ED, Douglas KM, Kitas GD. ‘Compliance’ is futile but is ‘concordance’ between rheumatology patients and health professionals attainable? Rheumatology. 2006;45:1–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen SM. Concept Analysis of Adherence in the Context of Cardiovascular risk reduction. Nurs Forum. 2009;44:25–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Compliance and adherence are dysfunctional concepts in diabetes care. Diabetes Educ. 2000;26:597–604. doi: 10.1177/014572170002600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chatterjee JS. From compliance to concordance in diabetes. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:507–10. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.012138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullen PD. Compliance becomes concordance. BMJ. 1997;314:691. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7082.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiMatteo MR. Variations in Patients’ Adherence to Medical Recommendations: A Quantitative Review of 50 Years of Research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC, Avorn J. Long-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients. JAMA. 2002;288:455–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carpenter R. Perceived threat in compliance and adherence research. Nurs Inquiry. 2005;12:192–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bland RJ, Cottrell RR, Guyler LR. Medication compliance of hemodialysis patients and factors contributing to Non-Compliance. Dial Transpl. 2008;37:174–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evangelista LS. Compliance: A Concept Analysis. Nurs Forum. 1999;34:5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1999.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon K, Smith F, Dhillon S. Effective chronic disease management: Patients’ perspectives on medication-related problems. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65:407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin J, Sklar GE, Oh VMS, Li SC. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:269–86. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klauer T, Zettl UK. Compliance, adherence, and the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2008;255:87–92. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-6016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pamboukian SV, Nisar I, Patel S, Gu L, McLeod M, Costanzo MR, et al. Factors Associated with Non-adherence to Therapy with Warfarin in a Population of Chronic Heart Failure Patients. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:30–4. doi: 10.1002/clc.20175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose LE, Kim MT, Dennison CR, Hill MN. The contexts of adherence for African Americans with high blood pressure. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:587–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stewart KS, Dearmun AK. Adherence to health advice amongst young people with chronic illness. J Child Health Care. 2001;5:155–62. doi: 10.1177/136749350100500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hekmatpou D, Mohammadi E, Ahmadi F, Arefi SH. Non-compliance factors of congestive heart failure patients readmitted in cardiac care units. Iran J Crit Care Nurs. 2009;2:91–7. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lahdenperä TS, Kyngäs HA. Levels of compliance shown by hypertensive patients and their attitude toward their illness. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34:189–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kagee A, Le Roux M, Dick J. Treatment adherence among primary care patients in a historically disadvantaged community in South Africa: A qualitative study. Health Psychol. 2007;12:444–60. doi: 10.1177/1359105307076232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paterson BL, Charlton P, Richard S. Non-attendance in chronic disease clinics: A matter of non-compliance? J Nurs Healthc Chronic Illn. 2010;2:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kyngäs HA, Kroll T, Duffy ME. Compliance in adolescents with chronic diseases: A review. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26:379–88. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tabor PA, Lopez DA. Comply with us: Improving medication adherence. J Pharm Pract. 2004;17:167–81. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gallant MP. The Influence of Social Support on Chronic Illness Self-Management: A Review and Directions for Research. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:170–95. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duncan C, Cloutier JD, Bailey PH. Concept analysis: The importance of differentiating the ontological focus. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive Validity of a Medication Adherence Measure in an Outpatient Setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Stromberg A, Brostrom A, Dahlstrom U, Fridlund B. Factors influencing patient compliance with therapeutic regimens in chronic heart failure: A critical incident technique analysis. Heart Lung. 1999;28:334–41. doi: 10.1053/hl.1999.v28.a99538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]