Significance

A single clone, pulsed-field gel type USA300, has driven an unprecedented community-associated epidemic of Staphylococcus aureus infections, often affecting young, otherwise healthy individuals. Here we reconstruct the recent evolution and phylogeographic spread of USA300, using whole-genome sequencing of a large collection of infection and colonization isolates from a Manhattan community. We find that households serve as major reservoirs of persistence and transmission. By defining isolate variability within and between households, we localized putative transmission networks in the community. We further identified clonal spread of fluoroquinolone-resistant USA300, suggesting a critical role for antibiotic exposure in the recent evolution of this epidemic strain. Our study provides an important framework for molecular epidemiological investigations into the transmission of opportunistic pathogens that colonize and infect communities.

Keywords: phylogeny, genomics, CC8, drug resistance

Abstract

During the last 2 decades, community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) strains have dramatically increased the global burden of S. aureus infections. The pandemic sequence type (ST)8/pulsed-field gel type USA300 is the dominant CA-MRSA clone in the United States, but its evolutionary history and basis for biological success are incompletely understood. Here, we use whole-genome sequencing of 387 ST8 isolates drawn from an epidemiological network of CA-MRSA infections and colonizations in northern Manhattan to explore short-term evolution and transmission patterns. Phylogenetic analysis predicted that USA300 diverged from a most common recent ancestor around 1993. We found evidence for multiple introductions of USA300 and reconstructed the phylogeographic spread of isolates across neighborhoods. Using pair-wise single-nucleotide polymorphism distances as a measure of genetic relatedness between isolates, we observed that most USA300 isolates had become endemic in households, indicating their critical role as reservoirs for transmission and diversification. Using the maximum single-nucleotide polymorphism variability of isolates from within households as a threshold, we identified several possible transmission networks beyond households. Our study also revealed the evolution of a fluoroquinolone-resistant subpopulation in the mid-1990s and its subsequent expansion at a time of high-frequency outpatient antibiotic use. This high-resolution phylogenetic analysis of ST8 has documented the genomic changes associated with USA300 evolution and how some of its recent evolution has been shaped by antibiotic use. By integrating whole-genome sequencing with detailed epidemiological analyses, our study provides an important framework for delineating the full diversity and spread of USA300 and other emerging pathogens in large urban community populations.

The emergence and worldwide spread of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) since the late 1980s has led to an unprecedented epidemic of skin and soft tissue infections (1). An estimated 5–10% of these community-based infections are invasive and potentially life-threatening, often affecting young and healthy individuals (2). The high burden of CA-MRSA infections has been particularly apparent in the United States, where a single clone, designated USA300 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis (3) or sequence type ST8 by multilocus sequencing typing, has been responsible for this epidemic (4, 5).

The increased expression of virulence genes and the step-wise acquisition of unique mobile genetic elements (MGEs) are thought to have contributed to the well-documented virulence of USA300 in animal models of infection (6–9). This includes S. aureus Pathogenicity Island 5 (SaPI5), the Sa2int prophage encoding Panton-Valentine leucocidin (PVL), and the horizontally acquired arginine catabolic mobile genetic element (ACME). ACME is almost exclusively restricted to the USA300 lineage and has been implicated in resistance to host antimicrobial peptides and in promoting skin infections (8, 9). Earlier studies on the evolution of USA300, using a limited number of isolates, have suggested a recent clonal expansion and diversification of USA300 and have provided evidence that discrete changes in the core genome can significantly alter the virulence, proliferation, and persistence of selected USA300 isolates (10–13). Our understanding of how this clone became established as an endemic pathogen within communities remains limited. Its success, nevertheless, is likely dependent on a combination of microbial, host, and environmental factors.

USA300 has disseminated at different rates across the United States. For example, the emergence of USA300 in New York City lagged behind other regions of the country (4, 5), but by 2009, this clone had become firmly established as the predominant cause of CA-MRSA infections (∼75%) in northern Manhattan (14, 15). Our recent assessment of risk factors for CA-MRSA infections revealed a higher burden of USA300 colonization of household members and contamination of environmental surfaces in households with an infected index compared with noninfected control households. Environmental contamination with USA300 in particular was associated with an increased frequency of recurrent S. aureus infections (14) and transmission between household members (15). These observations suggest a crucial role for community households as reservoirs for the maintenance and spread of USA300. Alternatively, the predominance of USA300 as a cause of CA-MRSA infections potentially suggests centralized sources within the wider community, such as shops or schools that could result in community-wide outbreaks. In either scenario, unique genomic factors are likely to accelerate the expansion of USA300 compared with other clones.

Conventional genotyping techniques have failed to characterize the genetic ancestry of USA300, precluding a detailed molecular epidemiological understanding of how USA300 has spread and evolved within and between community households. Whole-genome sequencing and novel comparative genomics tools have recently been used to reconstruct the evolutionary history and global spread of mainly hospital-associated MRSA lineages such as ST22, ST30, and ST239, or to resolve outbreaks in hospital units (16–20). The power of genome sequencing to identify missing epidemiological links in small community outbreaks of Mycobacterium tuberculosis has also recently been demonstrated (21, 22). Here, we have sequenced and compared a large collection of epidemiologically well-characterized ST8 S. aureus isolates drawn from a CA-MRSA transmission study as a means of determining their population structure and short-term evolution in an urban community. Our integration of genomic and epidemiological data illustrates the dynamic evolution of USA300 within households. These results provide important insights into the genomic basis of the recent successful USA300 expansion and spread.

Results and Discussion

Phylogenetic Reconstruction of ST8 Lineage Isolates from an Urban Community.

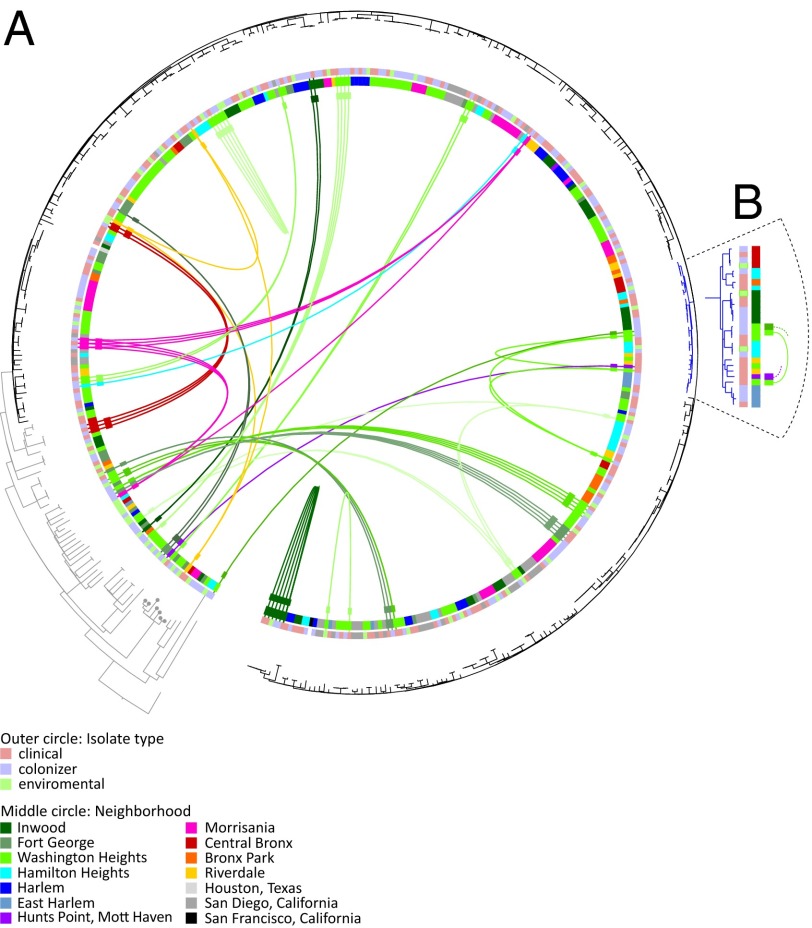

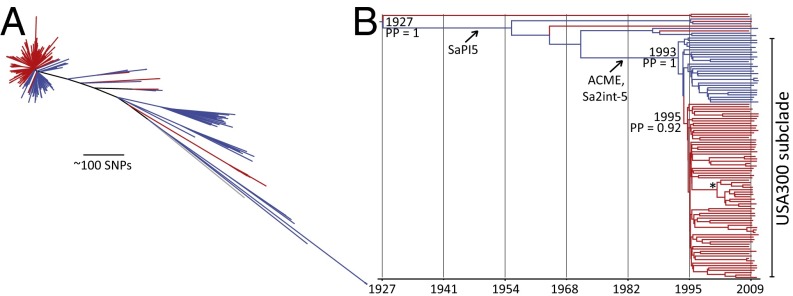

We determined full-genome sequences of 387 spa-clonal complex t008/ST8 isolates (Fig. S1 and Table S1). These were selected from a community-based case-control study of MRSA transmission in northern Manhattan and the Bronx (14, 15), which enrolled 161 individuals with CA-MRSA infections between January 2009 and May 2011. These individuals were age-matched to noninfected controls. To enhance the temporal and geographic signal in the sample set for comparative sequence analyses, we also included previously published ST8 sequences from the same New York City neighborhood (12) and from San Diego, California, as a separate regional comparator (11). These samples were collected between 2004 and 2009. After excluding MGEs, we identified a total of 12,472 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in this collection in comparison with the USA300 reference sequence named FPR3757 (8). These “core” genome SNPs were used to construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1A). Around 85% of isolates clustered within a closely related clade, which also contained the USA300 genome reference isolate (FPR3757), and another published USA300 genome reference (named TCH1516) (23). The remaining isolates were more diverse and formed several clades. Within these clades, we found an isolate belonging to USA500, the proposed progenitor of USA300, and a number of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus ST8 isolates (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny of ST8 and the emergence of USA300. (A) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of ST8 isolates, rooted by using the distantly related S. aureus isolate named COL as an out-group. The USA300 clade is shaded in black, and the non-USA300 ST8 clades are in gray. Dots indicate the USA500 clade. Colors in the outer ring show the isolate type, and colors in the middle circle indicate the neighborhoods. Lines connect distantly related isolates with >23 SNPs from the same household (colored by neighborhood). (B) A unique subclade, defined by a nonsense mutation in wrbA, is shown in blue. Colors on the left indicate isolate type, and on the right they indicate neighborhood. Lines connect distantly related isolates from the same household.

In total, 374 isolates were contained within the USA300 clade, and using the 6,014 SNP sites in this population, we investigated their microevolutionary history. Subsequent analyses revealed a mutation rate of 1.22 × 10−6 (95% confidence interval, 6.04 × 10−7–1.86 × 10−6) substitutions per nucleotide site per year (Fig. S2), which corresponds with ∼3 SNPs per year. This rate estimate is comparable to estimates from the mainly hospital-associated lineages ST22 and clonal complex 30, whereas the mutation rate of ST239 is ∼twofold higher (Fig. S2B) (17, 19). This suggests that the mutation rate is relatively preserved across multiple S. aureus lineages. On the basis of this substitution rate, we estimate the date of divergence of the USA300 clade from its most recent progenitor to be around 1993. The level of homoplasy in the USA300 clade was very low (homoplasy index of 0.007), indicating that recombination likely only contributed at very low levels to the observed genetic changes and suggests clonal propagation of the core genome.

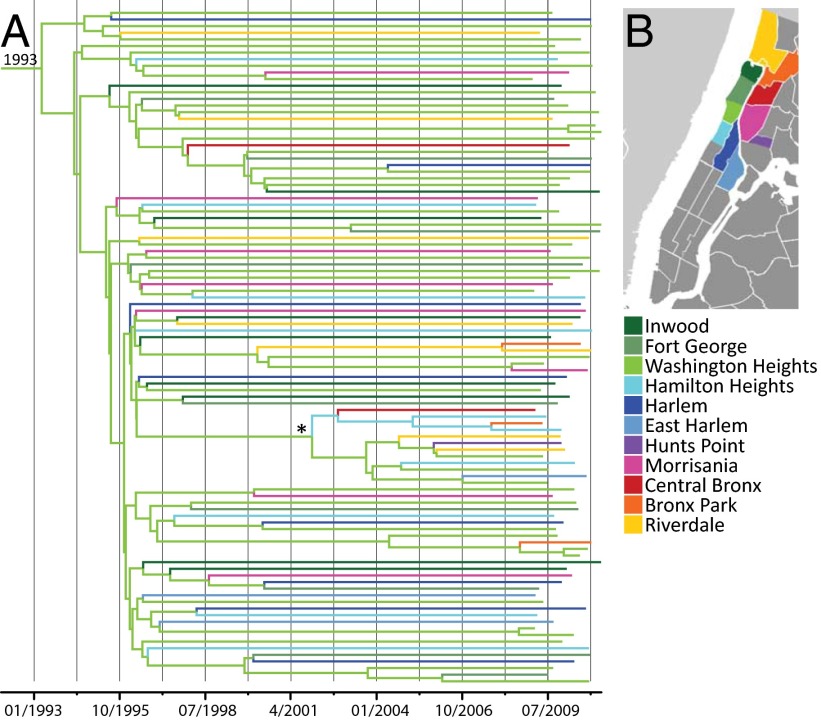

Using this high-resolution data set, we then investigated the phylogeographic relationships and temporal dynamics of the USA300 population. Examination of the geographic origin of the isolates within the USA300 clade (Fig. 1) revealed that the isolates from California and Texas were interspersed with isolates from northern Manhattan. Moreover, the Zip codes of the northern Manhattan isolates were widely distributed across the tree. This suggests that the USA300 population was likely to have been introduced multiple times into northern Manhattan, rather than having expanded rapidly from one local ancestor. A Bayesian phylogeographic reconstruction of ancestral nodes in the phylogenetic tree of the infectious USA300 isolates supports a root of the USA300 clade within the Washington Heights neighborhood and suggests subsequent spread to adjacent areas (Fig. 2). We note that the hospital in which patients presented is located in the Washington Heights neighborhood, as was the residence of the majority of recruited patients. Further studies are needed to evaluate the potential role of hospitals, where USA300 now also predominates, in the spread of USA300 back into the community.

Fig. 2.

Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction of northern Manhattan USA300 isolates. The phylogeny is a maximum clade consensus tree, estimated from core genome SNPs. (A) Colors of internal and terminal branches indicate neighborhoods. Branches are scaled with time (months/years). (B) Map of New York City indicating the sampled neighborhoods (adapted from Wikimedia Commons M. Minderhound).

Transmission of USA300 Within Households and the Community.

To further explore how USA300 spreads in the community, we investigated the possibility of direct transmission between households sampled in this study. Comparative whole-genome sequencing has been shown to be an effective tool in identifying bacterial outbreaks in hospitals (20). These nosocomial investigations frequently benefit from a high incidence of symptomatic disease and the ability to rapidly sample and identify asymptomatic carriers in a geographically and temporally restricted setting. Little precedence exists on how to approach outbreak analyses of opportunistic pathogens such as S. aureus in the community setting, where asymptomatic colonization may have existed for an extended time and where people are less likely to identify their personal contacts.

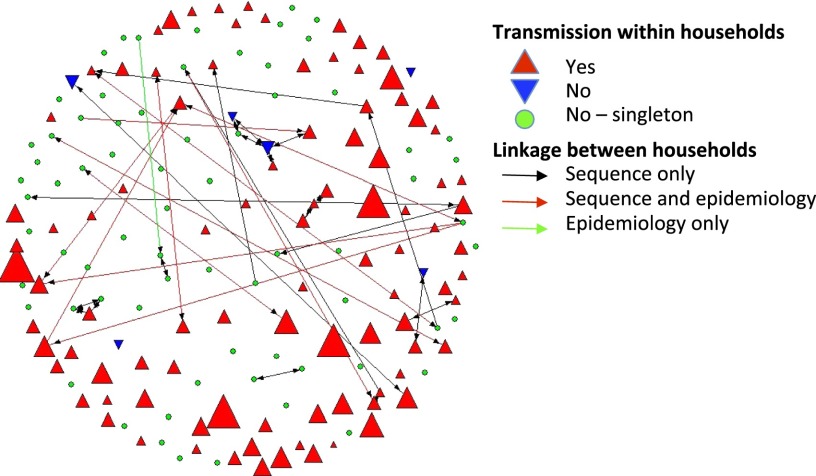

To overcome these limitations, we explored how individual and household-level sequence data could inform a cutoff for strain similarity in the community setting by measuring the SNP distance between pairs of isolates. This method takes advantage of the above-noted features of a consistent mutation rate across the population, very low levels of possible recombination, and no evidence of hypermutators. To estimate the genome variability during asymptomatic colonization, we first analyzed individuals who were colonized with ST8 isolates at multiple body sites (24). Multiple positive swabs were available for 21 individuals, ranging from two to five sites (throat, axilla, groin), yielding 55 isolates. The overall number of pair-wise SNPs ranged from 0 to 470 (median, 2) for a given individual.

Two individuals were colonized with two distinct USA300 clones that clustered in different parts of the tree and that harbored 70 and 470 pair-wise SNPs, respectively (Fig. 3A). Excluding these distinct isolates, paired samples collected from one individual differed by 1.4 SNPs (range, 0–9). Furthermore, all but one of 22 serial infectious episodes (defined as an infection of an individual at a new body site and occurring >1 month apart) were closely related (median pair-wise SNPs, 8; range, 0–37). Longitudinal isolates separated by larger time intervals (up to 43 months) harbored higher pair-wise SNP differences. However, two isolate pairs collected 6 months apart differed by none or only two SNPs, respectively. This lack of variability might in part be attributed to sequencing of single colonies from a potential cloud of diversity. Nevertheless, the close genetic relationship of these serial infectious isolates suggests that either the infected individual or their immediate contacts and environment may have served as the source of their reinfection. Isolates collected from individuals living in the same household were also closely related, with a median pair-wise SNP distance of 3 (range, 0–772; Fig. 3B). In contrast, the median SNP difference of all isolates collected from different households in this community was considerably higher, at 104 (range, 0–1,008; Fig. 3B). Taken together with the observation from the phylogenetic reconstruction that geographically unrelated isolates are interspersed, these findings argue against a community-wide outbreak of USA300 infections. This suggests that USA300 isolates have become endemic in households, which serve as important reservoirs for colonization, transmission, and infection. Despite the close relationship of isolates from the same household, the increased resolution provided by whole-genome sequencing also revealed that up to 17% of possible transmission events, as determined by conventional genotyping (spa-typing and, in select cases, multilocus sequencing typing or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis) overestimated strain similarity and transmission within the 82 households with multiple ST8 isolates (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 3.

Pairwise SNP comparisons between (A) multiple body sites from one person (nose, throat, and skin sites axilla or groin) or (B) within households (red) or between isolates from different community households (blue).

We determined that 23 SNPs was the maximum pair-wise distance of isolates with a clearly established epidemiological link (i.e., collected from a single household). When applying this maximum threshold of 23 SNPs, isolates from 47 of the 170 households were similar to at least one isolate from another household, yielding 35 household pairs. The median SNP difference of these household pairs was four SNPs (range, 0–23). Interview data confirmed an epidemiologic connection for 10 of the 35 household pairs (Fig. 4). Isolates from eight of these 47 linked households belonged to a larger subclade with a deep basal branch (Fig. 1B). Unlike the majority of the population originating from a more distant ancestor, this geographically dispersed group of isolates shared a relatively recent common ancestor around 2002 (Fig. 2). This raised the hypothesis that this clade represents a successful clone relative to the wider USA300 population of the study sample (Fig. 1B). We first explored whether the 29 isolates from this subclade were linked by a unique epidemiology. These isolates were collected from 14 different households during a 20-month period. Their median pair-wise SNP distance was 38 (range, 0–55), exceeding our previously defined threshold for transmission between households. The isolates defining this clade were mostly collected from low-income households of Hispanic ethnicity. However, these households did not differ significantly from the overall study population, and no hidden epidemiological links, such as sports participation, age categories, pet ownership, or recent travel, were identified (Table S2).

Fig. 4.

Putative transmission of isolates within and between community households. Upright red triangles indicate transmission within households, which corresponds with the number of similar isolates. Downward blue triangles indicate multiple unrelated ST8 isolates, and green highlights single ST8 isolate households. Linkages between households are shown as black lines (identical sequences), red lines (sequence and epidemiological connection), or green lines (epidemiological but no sequence link).

Next, we defined the genetic events that distinguish this subclade from the remainder of the USA300 clade and perhaps contribute to its persistence or transmissibility. All isolates shared 26 SNPs, including seven intergenic, three synonymous, and 16 nonsynonymous. One of these was a nonsense mutation in the putative wrbA gene (25). In comparison, nonsense mutations were only sporadically present in the overall data set and involved 212 positions. In Escherichia coli, the WrbA protein was identified as the founding member of a novel class of flavoproteins (25). Despite its conservation from bacteria to plants, its exact function still remains incompletely understood, but it is thought to play a role in the oxidative stress defense or cell signaling (26, 27). In addition to the wrbA pseudogene, these isolates harbored 15 additional nonsynonymous SNPs (Table S3). Of note, ACME was absent in eight (28%) and a prophage belonging to the integrase type Sa5int was present in 15 (52%) of these isolates. Taken together, this subclade perhaps represents a successful clone within USA300. However, the genetic basis for this requires further investigations.

USA300 Genome.

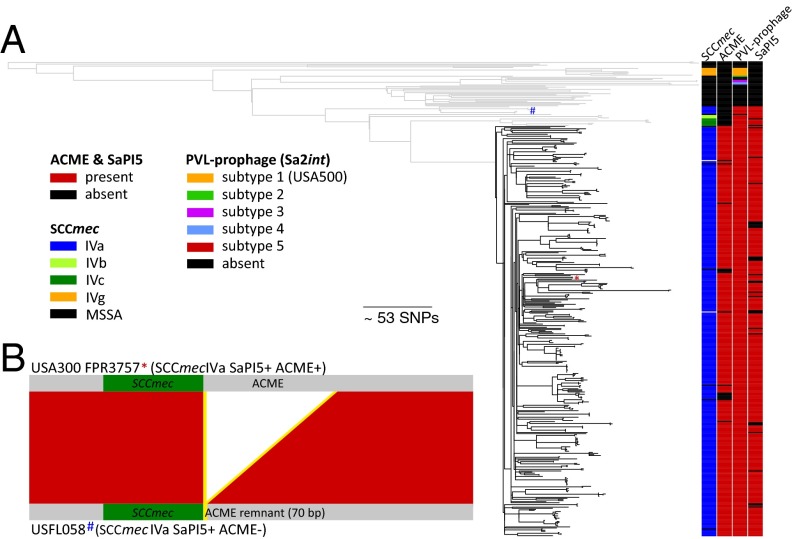

A repertoire of MGEs contribute to the biological success of USA300 (8, 9, 28), so we defined the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) element subtype and presence of prophages, SaPI5, and ACME for each isolate. Their distribution closely mirrored the phylogeny of the core genome (Fig. 5 and Fig. S3). The presence of ACME was restricted to USA300 (Fig. 5), although it was not present in 23 isolates (6%) in this lineage (n = 23; 6%), and its sequence exhibited very limited genetic variability, with only 70 SNPs (Fig. S4A). These data are most consistent with a single acquisition of ACME into the progenitor of the USA300 clade, followed by recent clonal dissemination and occasional loss of the element. All but four ACME-negative isolates in the USA300 clade were also SCCmec type IVa-negative, and similar to the ACME element, there appears to have been a single acquisition event of SCCmec type IVa that defined the emergence of USA300. Notably, methicillin resistance has evolved in the ST8 ancestral population on several occasions via the acquisition of different subtypes of SCCmec type IV elements (IVb, IVc, IVe, and IVg; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Accessory genome diversity in ST8. (A) The presence of MGEs closely mirrors the phylogeny of the core genome. ACME is restricted to the USA300 clade (shaded in black). (B) Evidence for ACME remnants in isolates carrying SAPI5 and SCCmec IVa. Visualization of a BlastN pairwise comparison in ACT (48) of the ACME regions of FPR3757 reference sequence (*) and isolate USFL058 (#).

Prophage Sa4int was absent from the entire ST8 lineage, and Sa7int was detected only in non-USA300 samples (n = 8), whereas Sa6int (2%), Sa1int (11%), and Sa5int (16%) were present relatively infrequently in the USA300 clade (Fig. S3). Some of the observed variability of MGEs was found among isolates with a closely related core genome, including from the same individual or households, suggesting that isolates can rapidly acquire or lose prophages during colonization. Sa2int and Sa3int were detected in almost all isolates. We found evidence for at least five different acquisitions of the lukSF-carrying Sa2int prophage into ST8, with considerable sequence variability among the non-USA300 isolates (Fig. 5 and Fig. S4B). Our data further suggest only a single uptake of Sa2int into USA300. This coincided with the acquisition of ACME (between 1970–1993), resulting in the emergence of USA300 (Fig. 6B). In contrast, SaPI5, also thought to be unique to USA300, was detected in several non-USA300 isolates with a most common recent ancestor around 1957 (Figs. 5 and 6B). SaPI5 sequences differed by a limited number of SNPs, consistent with a single acquisition event (Fig. S4C). SaPI5-positive and ACME-negative non-USA300 isolates carried SCCmec IVa, IVb, or IVc. Interestingly, some of these SCCmec-IVa isolates contained ACME remnants adjacent to the SCCmec element (Fig. 5B), suggesting ACME was acquired, and subsequently lost, by a precursor clone. This raises the possibility that additional genomic adaptations in the core genome were necessary to enable the successful clonal expansion of the SCCmec IVa/ACME/SaPI5-positive USA300 clone. The USA300 clade was separated from these ACME-remnant carrying isolates by 62 SNPs (12 intergenic, 14 synonymous, 36 nonsynonymous SNPs; Table S4).

Fig. 6.

Clonal emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance-conferring mutations in gyrA and grlA. (A) Maximum likelihood tree of all isolates. (B) Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction based on 112 clinical isolates. The phylogeny is a maximum clade consensus tree estimated from core genome SNPs. Branches are colored according to the fluoroquinolone genotype as susceptible (blue) and resistant (red). The tips of the tree are constrained by isolation date. PP, posterior probability. Gains of MGEs SAPI5, ACME, Sa2int, and the nonsense mutation in wrbA (*) have been mapped on the tree.

Drug Resistance in ST8.

One of the original features of USA300 was its overall susceptibility to non-β-lactam antibiotics in comparison with other epidemic MRSA (3), although more recently, increasing drug resistance has been reported (29). We analyzed the whole-genome sequences of the ST8 isolates to elucidate the antibiotic resistance genotype and examine the evolutionary dynamics of the development of resistance. Drug resistance differed substantially between USA300 isolates and the remainder of the sample, with methicillin resistance being the most marked difference. In the USA300 clade, resistance to gentamicin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was infrequent and was consistent with a low prevalence of plasmid pUSA02 (8, 30) (Fig. S5). Plasmid pUSA03-encoded ileS, conferring high-level mupirocin resistance and previously suggested as a major driver in the USA300 epidemic (31), was only present in 24 isolates (7%). The majority of USA300 isolates harbored a large plasmid closely resembling p18805-p03 (30) and encoding for resistance to kanamycin (aphA-3), erythromycin (msrA), beta-lactams (blaZ), and heavy metals (cadD-cadX operon; Fig. S5B).

Of the ST8 isolates, 118 (31.6%) of 374 were fully susceptible to fluoroquinolones. Remarkably, isolates harboring fluoroquinolone-resistance conferring mutations gyrA and S80F/S80Y grlA clustered together in the USA300 clade (Fig. 6 and Fig. S5), consistent with a clonal propagation of this genotype after its emergence on a single occasion, rather than multiple acquisitions. Further analyses suggested this resistant clade emerged around 1995 from an already successful USA300 population (Fig. 6B). SNPs associated with fluoroquinolone-resistance have previously been invoked in the success of hospital-associated EMRSA-15 in the United Kingdom. Here, the timing of the increasing and widespread use of fluoroquinolones (in particular, ciprofloxacin in the United Kingdom) and the acquisition of resistance-conferring mutations in ST22 coincided with the expansion of this clone (17). Furthermore, a decrease in prescriptions of ciprofloxacin was temporarily correlated with a reduced incidence of MRSA infections in a UK hospital (32). Similarly, we note a time-dependent correlation of national outpatient prescriptions for fluoroquinolones and CA-MRSA incidence in the United States (Fig. S6). Fluoroquinolone use increased in the United States by 49% between 1999 and 2008 (www.cddep.org/resistancemap/use/quinolones; Fig. S6) but has since declined by 24%. This raises the possibility that the recently reported decline in CA-MRSA infections (33) may in part be attributed to decreased fluoroquinolone use in the United States. Fluoroquinolones are excreted onto the skin and impair the growth of the normal flora, providing a selective pressure that enables the spread of resistant organisms. In our community, about half the control patients reported the use of nondescript antibiotics during a 6-month period, suggesting substantial antibiotic pressure (14, 15). Alternatively, the recent emergence of USA300 as a nosocomial pathogen (34) may have contributed to the evolution and expansion of a fluoroquinolone-resistant USA300 clone in the hospital setting, which was then transferred back into the community. Last, not all S. aureus clones resistant to fluoroquinolones have become widespread, underscoring that the mechanisms conferring a fitness advantage are likely confounded by underlying additional genomic features.

Concluding Remarks.

USA300 has produced an unprecedented epidemic of CA-MRSA infections in the United States and, increasingly, elsewhere. Its dominance has been attributed to a combination of MGEs (8, 28), virulence genes (7), and host and epidemiologic risk factors (2, 14). Few studies, however, have been able to link these components. Applying whole-genome sequencing to a large collection of epidemiologically well-characterized ST8 isolates, we reconstructed the evolution of USA300 in an urban community. Comparative genome analyses strongly suggest that community households serve as a critical reservoir for CA-MRSA diversification, transmission, and infection. The emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistance-conferring SNPs in gyrA and grlA may have further promoted the expansion of USA300 as a major S. aureus clone. This observation highlights the potential effect of widespread antibiotic use on a population level. Further studies are warranted to determine the effect of fluoroquinolone resistance on the global evolution and spread of successful MRSA lineages.

Our sample collection of community isolates provides a unique perspective on the evolution of S. aureus during colonization and transmission within households. Despite the relatively recent expansion of USA300, our data suggest that this clone was introduced multiple times into northern Manhattan and that several different clades have become endemic and account for the majority of infection and colonization in this urban community. Although isolates collected from an individual were most closely related, their paired SNP numbers were comparable with isolates from other household members but differed substantially from those from the community. This strongly suggests that individuals within one household frequently exchange colonizing S. aureus strains, which in turn may serve as the source for the increased frequency of infections among household members (14). These results support a “search and destroy” approach targeting not only infected patients but also their household members and home environment, which previously was applied successfully to control a large ST22 outbreak in Denmark (35). The identification of larger USA300-harboring networks beyond the household suggests further spread of USA300 in the community by mechanisms that have yet to be identified.

Through the use of whole-genome sequencing, we detected far greater genomic diversity than we originally anticipated in this large sample of nearly 400 ST8 isolates from the northern Manhattan community. This may in part be attributed to the challenges to capture S. aureus-infected patients in the community who may seek treatment at multiple different healthcare institutions, not be cultured at the time of diagnosis, or self-medicate. Despite these limitations, we were able to identify several putative transmission events between households according to the sequence similarity of isolates. Our results provide an important context for designing novel analytical tools to fully reconstruct the spread of a highly dynamic and evolving clone such as USA300 in an endemic community setting.

Materials and Methods

Sample Selection.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center. We selected 387 isolates (Fig. S1 and Table S1) from a community-based case-control study on CA-MRSA infection in Northern Manhattan and the Bronx (14, 15), which enrolled 161 individuals with CA-MRSA infections and noninfected age-matched controls between January 2009 and May 2011. Case and control indexes, participating household members, and social contacts were assessed for S. aureus colonization, household surfaces were surveyed for S. aureus contamination, and clinical infection isolates were collected. In total, 1,344 S. aureus isolates were identified and 478 were genotyped as spa-t008 or a related spa-type by BURP clustering (14, 15). Of these, all infectious isolates (n = 130), all available serial infectious isolates (occurring at least 1 month apart; n = 22), all nasal and skin colonization isolates, and one environmental isolate per household were selected for sequencing, resulting in 387 isolates (Fig. S1). Additional comparative sequence analyses also included previously published ST8 sequences from the same geographic region (n = 8); Houston, Texas (n = 1); and Californian settings in both San Francisco (n = 1) and San Diego (n = 36) (11, 12, 23).

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Detection of SNPs in the Core Genome.

S. aureus genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), and unique index-tagged libraries were generated. Whole-genome sequencing was carried out using the Illumina HiSeq2000 with 100-base paired-end reads. Paired-end reads were mapped against the core chromosome of the ST8 USA300 reference genome sequence FPR3757 (accession NC_002952) (8). SNPs and indels were identified as described previously (16, 36, 37). Unmapped reads and sequences that were not present in all genomes and MGEs were not considered as part of the core genome; therefore, SNPs from these regions were not included in the phylogenetic analysis. SNPs falling within high-density SNP regions, which could have arisen by recombination, were identified using RepeatScout (38) and excluded from the core genome. The latter was curated manually to ensure a high-quality data set for subsequent phylogenetic analysis and was composed of 2,493,408 bp. The presence or absence of acquired genes and SNPs conferring resistance against 16 antimicrobial detergents was determined as described previously (39), and for SNPs causing resistance in housekeeping genes the standard mapping and SNP calling approach was used as described earlier. Sequence data are deposited in the European Nucleotide archive (accession PRJEB2870; see Table S1).

Phylogenetic Analyses.

A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree with 100 Bootstrap replications was drawn for USA300, using RAxML v0.7.4 (40). These analyses included the entire data set (434 isolates and 12,472 SNPs), infectious isolates only (142 isolates and 4,348 SNPs), or core-clade isolates only (374 isolates and 6,014 SNPs). A subset of 112 clinical isolates was used to infer the substitution rate, time of emergence, divergence dates, and phylogeographic spread, applying Bayesian methods as implemented in the BEAST v1.7.5 package (41). BEAST was run for 100 million generations, sampling every 10,000 states using the HKY substitution model. The age for each tip of the tree was defined as in day, month, and year of isolation. A strict, exponential-relaxed and lognormal-relaxed molecular clock with constant size coalescent and Bayesian skyline coalescent was used, respectively. Each model was run three times, and good converging of chains and effective sample size values were inspected using Tracer v1.5. A marginal likelihood estimation using path sampling and stepping stone sampling for each run was carried out to compare the different combinations of clock and tree models (42, 43). The marginal likelihood estimation was then used to assess the best-fitting model for the data set by calculating the Bayes Factor. For the used data set, the strict skyline model provided the best fit. LogCombiner v1.7.5 was used to remove states before the burn-in and then to combine the trees from the multiple runs. A maximum clade credibility tree from the combined trees was obtained using treeAnnotator v1.7.5. The geographic origin of isolation (as longitude, latitude, and neighborhood) was analyzed as a continuous and discrete trait, and BEAST was used to infer geographic origin and resistance of internal nodes.

In silico Detection of MGEs.

Sequence reads were assembled de novo into contigs, using velvet v1.0.12 (44) and velvet optimizer, and were used to determine the presence, absence, and diversity of MGEs. All isolates had been assigned as SCCmec IV, using a previously described multiplex PCR (14, 15). The subtype was determined using an in silico PCR approach (45, 46). Prophages were classified according to their defined integrase type (47). To investigate the diversity of the PVL-containing prophage, ACME, and SaPI5, corresponding sequences were extracted from the mapping alignment. Plasmids were identified by mapping fastq reads against a subset of 22 plasmids commonly found in USA300 isolates (30).

Statistical Analysis.

Detailed epidemiological information was available on the case and control indexes, including demographic, health, and risk behavior variables. In addition, date and location data by longitude and latitude were analyzed to identify possible transmission events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Glenny Vasquez. The authors are indebted to her invaluable contributions in enthusiastically engaging community members in our study. The authors thank the core sequencing and informatics teams at the Sanger Institute for their invaluable assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI082536 and R21 AI103562 to F.D.L. and K08 AI090013 to A.-C.U.), the Paul A. Marks Scholarship (to A.-C.U.), a United Kingdom Clinical Research Collaboration Translational Infection Research Initiative award (Grant G1000803 to S.J.P.), and the Wellcome Trust (Grant 098051 to J.D., M.T.G.H., and J.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. A.G.B. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: Sequences have been deposited with the European Nucleotide Archive (accession no. PRJEB2870).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1401006111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(3):616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fridkin SK, et al. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Program of the Emerging Infections Program Network Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in three communities. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(14):1436–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDougal LK, et al. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: Establishing a national database. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(11):5113–5120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5113-5120.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran GJ, et al. EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):666–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talan DA, et al. EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus from skin and soft-tissue infections in US emergency department patients, 2004 and 2008. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(2):144–149. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M, et al. Comparative analysis of virulence and toxin expression of global community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(12):1866–1876. doi: 10.1086/657419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li M, et al. Evolution of virulence in epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(14):5883–5888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900743106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diep BA, et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367(9512):731–739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi GS, Spontak JS, Klapper DG, Richardson AR. Arginine catabolic mobile element encoded speG abrogates the unique hypersensitivity of Staphylococcus aureus to exogenous polyamines. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82(1):9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy AD, et al. Epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Recent clonal expansion and diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(4):1327–1332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710217105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tewhey R, et al. Genetic structure of community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1):508. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uhlemann AC, et al. Toward an understanding of the evolution of Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 during colonization in community households. Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4(12):1275–1285. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prosperi M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the genomic era: A cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1902. doi: 10.1038/srep01902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uhlemann AC, et al. The environment as an unrecognized reservoir for community-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300: A case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e22407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knox J, et al. Environmental contamination as a risk factor for intra-household Staphylococcus aureus transmission. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e49900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris SR, et al. Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science. 2010;327(5964):469–474. doi: 10.1126/science.1182395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holden MT, et al. A genomic portrait of the emergence, evolution, and global spread of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pandemic. Genome Res. 2013;23(4):653–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.147710.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLeo FR, et al. Molecular differentiation of historic phage-type 80/81 and contemporary epidemic Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(44):18091–18096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111084108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAdam PR, et al. Molecular tracing of the emergence, adaptation, and transmission of hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(23):9107–9112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202869109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris SR, et al. Whole-genome sequencing for analysis of an outbreak of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(2):130–136. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70268-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Török ME, et al. Rapid whole-genome sequencing for investigation of a suspected tuberculosis outbreak. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(2):611–614. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02279-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardy JL, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and social-network analysis of a tuberculosis outbreak. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):730–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Highlander SK, et al. Subtle genetic changes enhance virulence of methicillin resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golubchik T, et al. Within-host evolution of Staphylococcus aureus during asymptomatic carriage. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e61319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang W, Ni L, Somerville RL. A stationary-phase protein of Escherichia coli that affects the mode of association between the trp repressor protein and operator-bearing DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(12):5796–5800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carey J, et al. WrbA bridges bacterial flavodoxins and eukaryotic NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases. Protein Sci. 2007;16(10):2301–2305. doi: 10.1110/ps.073018907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishko I, et al. Biphasic kinetic behavior of E. coli WrbA, an FMN-dependent NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e43902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurlow LR, et al. Functional modularity of the arginine catabolic mobile element contributes to the success of USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13(1):100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDougal LK, et al. Emergence of resistance among USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing invasive disease in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(9):3804–3811. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00351-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy AD, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence analysis of plasmids in strains of Staphylococcus aureus clone USA300 reveals a high level of identity among isolates with closely related core genome sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(12):4504–4511. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01050-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diep BA, et al. Emergence of multidrug-resistant, community-associated, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone USA300 in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):249–257. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knight GM, et al. Shift in dominant hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (HA-MRSA) clones over time. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(10):2514–2522. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landrum ML, et al. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus blood and skin and soft tissue infections in the US military health system, 2005-2010. JAMA. 2012;308(1):50–59. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seybold U, et al. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(5):647–656. doi: 10.1086/499815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Böcher S, et al. The search and destroy strategy prevents spread and long-term carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Results from the follow-up screening of a large ST22 (E-MRSA 15) outbreak in Denmark. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(9):1427–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Croucher NJ, et al. Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science. 2011;331(6016):430–434. doi: 10.1126/science.1198545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albers CA, et al. Dindel: Accurate indel calls from short-read data. Genome Res. 2011;21(6):961–973. doi: 10.1101/gr.112326.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i351–i358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reuter S, et al. Rapid bacterial whole-genome sequencing to enhance diagnostic and public health microbiology. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(15):1397–1404. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamatakis A, Ludwig T, Meier H. RAxML-III: A fast program for maximum likelihood-based inference of large phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(4):456–463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(8):1969–1973. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baele G, et al. Improving the accuracy of demographic and molecular clock model comparison while accommodating phylogenetic uncertainty. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(9):2157–2167. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baele G, Li WL, Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Lemey P. Accurate model selection of relaxed molecular clocks in bayesian phylogenetics. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(2):239–243. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: Algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18(5):821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milheiriço C, Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. Multiplex PCR strategy for subtyping the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type IV in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: ‘SCCmec IV multiplex’. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(1):42–48. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Damborg P, Bartels MD, Boye K, Guardabassi L, Westh H. Structural variations of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type IVa in Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 8 and unrelated lineages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(8):3932–3935. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00012-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goerke C, et al. Diversity of prophages in dominant Staphylococcus aureus clonal lineages. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(11):3462–3468. doi: 10.1128/JB.01804-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carver TJ, et al. ACT: The Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(16):3422–3423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.