Significance

Given the mismatch between the nervous system's limited computational capability and the immense information content of the sensory environment, the brain must selectively focus attention on relevant stimulus aspects. “Sensory gating” describes the filtering of relevant sensory cues from irrelevant or redundant stimuli. One such filter may involve cortical control of sensory relay through the thalamus. Using optogenetics to turn on specific cortical input to the thalamus, we investigated how the brain actively controls and gates the information that reaches higher stages of processing in the cortex. We found that this pathway, conserved across most mammalian sensory systems, serves as an effective top-down controller of thalamic gating of dynamic patterns of sensory input.

Keywords: sensory systems, firing mode, Ntsr1, top-down modulation, low threshold calcium spike

Abstract

A major synaptic input to the thalamus originates from neurons in cortical layer 6 (L6); however, the function of this cortico–thalamic pathway during sensory processing is not well understood. In the mouse whisker system, we found that optogenetic stimulation of L6 in vivo results in a mixture of hyperpolarization and depolarization in the thalamic target neurons. The hyperpolarization was transient, and for longer L6 activation (>200 ms), thalamic neurons reached a depolarized resting membrane potential which affected key features of thalamic sensory processing. Most importantly, L6 stimulation reduced the adaptation of thalamic responses to repetitive whisker stimulation, thereby allowing thalamic neurons to relay higher frequencies of sensory input. Furthermore, L6 controlled the thalamic response mode by shifting thalamo–cortical transmission from bursting to single spiking. Analysis of intracellular sensory responses suggests that L6 impacts these thalamic properties by controlling the resting membrane potential and the availability of the transient calcium current IT, a hallmark of thalamic excitability. In summary, L6 input to the thalamus can shape both the overall gain and the temporal dynamics of sensory responses that reach the cortex.

Sensory signals en route to the cortex undergo profound signal transformations in the thalamus. One important thalamic transformation is sensory adaptation. Adaptation is a common characteristic of sensory systems in which neural output adjusts to the statistics and dynamics of past stimuli, thereby better encoding small stimulus changes across a wide range of scales despite the limited range of possible neural outputs (1–3). Thalamic sensory adaptation is characterized by a steep decrease in action potential (AP) activity during sustained sensory stimulation (4–7), decreasing the efficacy at which subsequent sensory stimuli are transmitted to the cortex.

The widely reported duality of thalamic response mode is another key property of thalamic information processing which further affects how sensory input reaches the cortex. In burst mode, sensory inputs are relayed as short, rapid clusters of APs; in contrast, in tonic mode the same inputs are translated into single APs. Both tonic and burst modes have been described during anesthesia/sleep and wakefulness/behavior, with a pronounced shift toward the tonic mode during alertness (8–12).

Although the exact information content of thalamic bursts is not yet clear, it has been suggested that bursting may signal novel stimuli to the cortex, whereas the tonic mode enables linear encoding of fine stimulus details, e.g., when an object is examined (13, 14). One issue hampering the interpretation of burst/tonic responses is that currently it is unknown if the cortex itself is involved in the rapid changes in firing modes seen in the awake and anesthetized animal (15, 16) and which mechanisms initiate these shifts in vivo.

On the biophysical level, the response mode depends on the resting membrane potential (RMP), which controls the availability of the transient low-threshold calcium current (IT) (17). Depolarization decreases the size of the IT-mediated low-threshold calcium spike (LTS), and fewer burst spikes are fired (18). Similarly, RMP influences adaptation in that depolarization reduces the voltage distance to the AP threshold, thereby increasing the probability that smaller, depressed inputs will trigger APs (6). Thus, the dynamics of the RMP may govern several key properties of signal transformation in the thalamus, thereby providing a common mechanism for controlling thalamic adaptation and response mode.

Although subcortical inputs have been shown to influence thalamic firing modes (7, 9), we investigated the impact of cortical activity on thalamic sensory processing. Cortico–thalamic projections from cortical layer 6 (L6) are a likely candidate for regulating thalamic sensory processing with high spatial and temporal precision, because these projections provide a major input to the thalamus and, as shown by McCormick et al. (19), depolarize and modulate firing of thalamic cells in vitro.

However, because of the inability to study sensory signals in brain slices, the role of L6 on thalamic input/output properties during sensory processing is not clear. Here, in the ventro posteromedial nucleus (VPM) of the mouse whisker thalamus, we investigate how L6 impacts the transmission of whisker inputs to the cortex. Recent advances in cell-type–specific approaches to dissect specific circuits in vivo (20–22) allowed us to activate the L6–thalamic pathway specifically and determine its impact on thalamic sensory processing.

We found that cortical L6 can change key properties of thalamic sensory processing by controlling the interaction of intrinsic membrane properties and sensory inputs. This mechanism enables the cortex to control the frequency-dependent adaptation and the gain of its own input.

Results

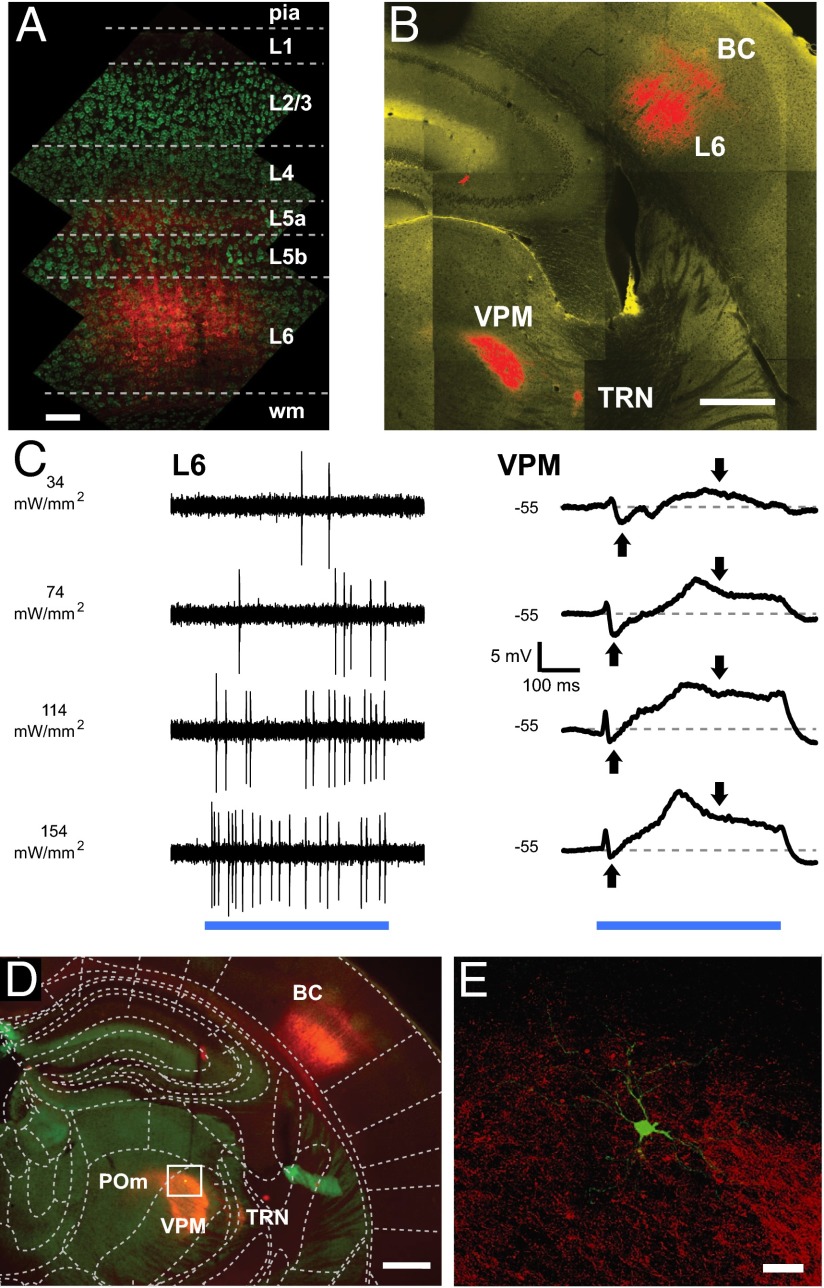

To examine the role of L6 feedback on sensory transmission in the VPM, we used an in vivo cell-type–specific stimulation approach in a mouse line with cre expression restricted to neurotensin receptor 1 (Ntsr1) expressing neurons in L6 (22, 23). Virus-mediated expression of ChR2-mCherry in the barrel cortex (BC) showed bright fluorescence from L6 somata and neuropil (Fig. 1A and Figs. S1 and S2). Neuronal somata expressing ChR2 were restricted to L6 (23, 24), ensuring that optical stimulation of cortex specifically activated the L6 cortico–thalamic pathway. Thalamic projections of these neurons could be seen readily in the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN), posterior medial nucleus (POm), and VPM, corresponding to L6 inputs to the thalamus (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Cell-type–specific optogenetic stimulation of L6 evokes synaptic responses in the VPM. (A) ChR2-mCherry expression in the BC. Fluorescence (red) in respect to cortical layers shows labeled somata in L6 and dendritic tufts and/or terminals in L5a and L4. Cortical layer estimates are based on soma sizes and densities, visualized with a fluorescent Nissl stain (green; Neurotrace). (Scale bar: 100 µm.) (B) L6 (Ntsr1) neurons expressing ChR2-mCherry (red) in the BC project to the VPM and the TRN in the somatosensory thalamus. (Scale bar: 500 µm). (C, Left) Juxtacellular recording of L6 spikes in response to light stimulation (500 ms; blue bar) at varying laser intensities. (Right) Biphasic mean intracellular VPM responses to the same stimuli. Downward/upward arrows indicate depolarization/hyperpolarization; dashed lines show control RMP. (D) Low-magnification fluorescence micrograph of a VPM neuron (green dot) labeled after the recording. Red fluorescence in the thalamus indicates labeled L6 boutons. The boxed region is shown in E. (Scale bar: 500 µm.) (E) Confocal fluorescence image of the VPM neuron (green) in D with labeled L6 axons and boutons (red). (Scale bar: 50 µm.)

To test if single-unit spikes could be evoked by photostimulation, we made juxtacellular recordings from single ChR2-expressing L6 neurons (n = 10) while applying laser pulses to the surface of the BC via an optical fiber (125 µm in diameter). L6 spike output scaled linearly with the stimulation intensity up to ∼7 Hz (Fig. 1C and Fig. S3, n = 6); for the experiments stimulating the L6–VPM pathway, we chose a moderate activation level of 74 mW/mm2, which drove sustained L6 spiking (∼4 Hz) during 500-ms stimulation epochs (Fig. 1C and Fig. S2). This rate is in the intermediate range of whisker touch evoked spiking reported for L6 in BC (25).

L6 Activation Evokes Biphasic Responses in Thalamic Neurons.

We made intracellular and juxtacellular recordings in the VPM to characterize the corresponding thalamic responses to this L6 stimulation paradigm. VPM neurons were identified by location (Fig. 1 D and E) and robust whisker responses (probability of whisker-evoked spiking: 0.84 ± 0.17, juxtacellular, n = 38) consisting of single spikes or bursts of spikes after single-whisker deflections (for stimulation, see SI Methods).

Intracellular photostimulation responses in the VPM typically consisted of a mixture of excitation and inhibition, with an initial fast excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) followed by a transient inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) and eventually a stable depolarization that persisted for the duration of the stimulus (Fig. 1C, Right).

While L6 excites VPM neurons monosynaptically, the inhibition most likely results from the coactivation of the GABAergic TRN (26). The resulting IPSPs were transient during longer L6 activation (>200 ms, Fig. 1C and Figs. S4 and S5A), consistent with the strong depression of this inhibitory pathway (Fig. S5B and refs. 7 and 27). Responses to L6 activation were variable (Fig. S4, n = 9) during the first 200 ms and across VPM neurons, resulting in mixed effects on spontaneous firing rates which could increase (12/27), decrease (3/27), or remain unchanged (12/27) during L6 activation. In the group with increased firing, APs were not tightly time locked to L6 activation and occurred after a slow ramp-up depolarization at 100–200 ms after the onset of L6 activation (Fig. S4B). Owing to this variability, we focus here on the effects of the L6-induced depolarization of the VPM, which we found to be more stable 200 ms after the onset of L6 activation.

In summary, L6 responses in the VPM combined inhibition and excitation, which were variable across the population, as also demonstrated in vitro (26). The balance between excitation and inhibition changed in a time-sensitive manner to favor excitation. Responses were more uniform toward the end of the stimulus and consisted of a depolarization. The average net depolarization 200 ms after the onset of L6 stimulation with the standard pulse (74 mW/mm2 for 500 ms) was 3.9 ± 3.2 mV (n = 9). Here we describe how this L6-induced depolarization impacts sensory responses in the VPM.

L6 Shifts the Thalamic Sensory Response Mode to Tonic Firing.

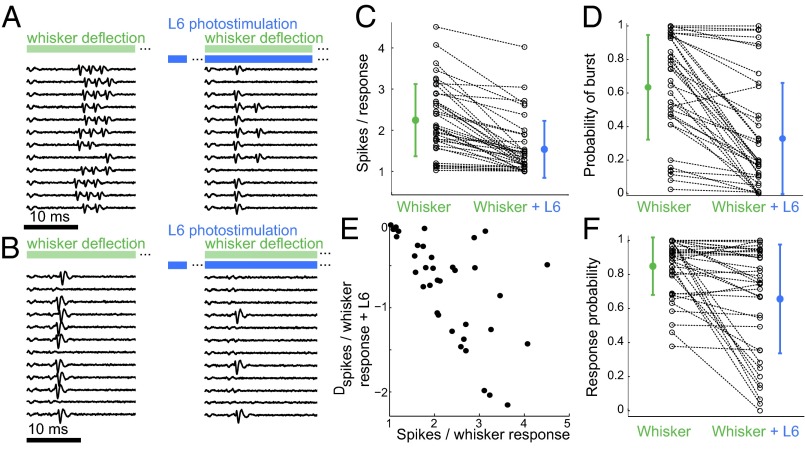

To examine the effect of L6 input on isolated sensory responses in the VPM, we first measured spike responses to single-whisker deflections while controlling the L6 to VPM pathway. As measures of burstiness, we examined both the total number of spikes per successful response and the burst probability (the proportion of bursts in all successful responses) (see SI Methods for details).

In control conditions, we found a continuum of response types across the recorded VPM neurons, ranging from highly bursty neurons with up to six spikes per response to predominantly tonic single-spike responders. An example of a bursty neuron is shown in Fig. 2A, and a purely tonic neuron is shown in Fig. 2B.

Fig. 2.

L6 activation influences the sensory response mode and the probability of response in the VPM. (A) Juxtacellular recording of a VPM neuron in response to whisker stimulation (Left, green) and whisker stimulation paired with L6 photostimulation (Right, blue). L6 stimulation started 200 ms before whisker stimulation as indicated by the gap in the blue bar. (B) As in A, but for a neuron in tonic mode. (C and D) Population summaries (n = 38) for number of spikes per whisker response (C) and the probability of burst per whisker response (D). Only successful responses were considered; dotted lines indicate pairings for individual neurons. Colored markers show mean values for whisker stimulation alone (green) or whisker stimulation combined with L6 input (blue). Error bars show SD. L6 activation decreased both the number of spikes per whisker response (2.3 ± 0.9–1.6 ± 0.7 spikes per response) (C) and the probability of a burst per whisker response (0.64 ± 0.3–0.33 ± 0.33) (D). (E) Data from C replotted to show how the L6-induced reduction in the number of spikes per whisker response (Dspikes, y-axis) depends on the initial burstiness (x-axis). (F) Summary of the probability of response per whisker deflection alone and per whisker deflection combined with L6 input, Plotting conventions are as in C and D. The average probabilities of response across the populations were 0.84 ± 0.17 for the control condition and 0.66 ±0.32 with L6 activation (P = 2.6*10−4, paired t test, n = 38).

We next examined the influence of L6 on the firing mode in the VPM by stimulating L6 and then costimulating the whisker after 200 ms. L6 activation typically decreased the number of spikes evoked by a single-whisker stimulation (Fig. 2A, Right). However, neurons that already were in tonic mode (Fig. 2B, Left) did not change response mode after L6 activation (Fig. 2B, Right). The majority (32/38) of VPM neurons showed a reduction in the number of spikes per successful stimulus (χ2 test, P < 0.01; Fig. 2C). The number of spikes per whisker deflection decreased on average from 2.3 ± 0.9 in the control condition to 1.6 ± 0.7 with L6 activation (P = 8.8*10−9, paired t test). Similarly, the probability of bursting in response to whisker deflection was significantly reduced by L6 activation (Fig. 2D). On average, burst probability was 0.64 ± 0.3 without L6 activation and was 0.33 ± 0.33 with L6 activation (P = 1.8*10−8, paired t test).

Shifts in firing mode were not observed in all neurons (Fig. 2 A–D). Instead the transition to tonic mode was graded so that the extent of the effect depended on the initial response mode of the neuron, with very bursty neurons being affected more strongly. Plotting the L6-induced change in the number of spikes per response vs. the initial number of spikes per response (Fig. 2E) summarizes how the L6-induced reduction in spikes per sensory response depends on the initial state of the neuron. Thus, for an ensemble of VPM neurons with heterogeneous initial response modes, L6 input homogenized the population output toward single-spike responses.

In addition to the firing mode, response probabilities (Fig. 2F) were affected by L6 stimulation, as is consistent with the effects of L6 stimulation on visual responses in the visual thalamus (23). Spike probabilities after a single-whisker stimulation were significantly reduced in approximately half of the neurons (17/38), were increased in a minority of neurons (3/38), and were unchanged in the remainder (18/38). There was no correlation between the reduction of spike probability and the initial burstiness (Fig. S6A).

Cellular Mechanism of L6-Induced Firing Mode Transition.

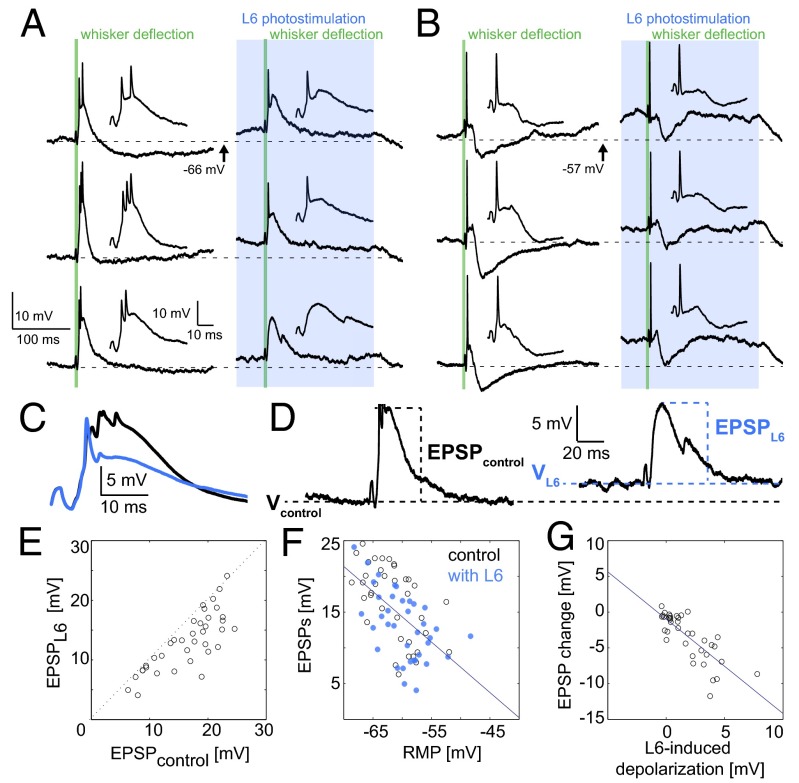

The L6-induced depolarization shown above and in previous in vitro studies (19, 26) provides a cellular mechanism for changes in firing mode. Thalamic depolarization via the L6 cortico–thalamic pathway may serve to inactivate the T-type Ca2+ channels and thereby weaken intrinsic bursting (17, 28). To explore this possibility in the context of thalamic sensory signaling in the intact brain, we repeated the sensory stimulation protocol from Fig. 2 in the whole-cell intracellular configuration and characterized the intracellular whisker responses with L6 activation.

Fig. 3 A and B shows representative repetitions of whisker responses with and without L6 activation from a bursty neuron and a tonic neuron. In both cases the APs are on top of a slow plateau LTS. The bursty neuron fires two- or three-burst APs, whereas the tonic neuron fires a single AP, and this tonic response also shows a smaller underlying LTS depolarization. In comparison with the bursty neuron, the tonic neuron had an elevated RMP in the control condition, which also emphasized the feedback IPSP. As with the juxtacellular recordings presented in Fig. 2, L6 activation reduced the number of APs in the bursty neuron, but the tonic neuron remained in tonic mode. With L6 stimulation, whisker responses were triggered from an elevated membrane potential, resulting in a smaller slow depolarization (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

L6 activation switches sensory responses in the VPM to tonic mode by depolarization. The L6 photostimulus (blue) started 200 ms before the 2-ms whisker stimulus (green). Two milliseconds (vs. 50 ms in the juxtacellular recordings) were used to minimize electrical piezo artifacts. (A) Whole-cell recording of (Left) a VPM neuron in response to whisker deflection (green) and (Right) whisker deflection paired with L6 photostimulation (blue box), showing three of 25 repetitions. The membrane potentials at the time of the whisker stimulus typically were higher with L6 stimulation and dropped back to baseline when the photostimulus ended. Insets show the first 50 ms of the whisker responses. (B) As in A, but for a neuron in tonic mode under control conditions (control RMP was ∼57 mV). Scale is as in A. (C) Intracellular whisker responses (mean from 25 repetitions from neuron in A) during control (black) and L6 activation (blue trace). (D) Intracellular whisker responses show measurements taken for the EPSP population analysis in E–G. Note base depolarization by L6: the dashed black lines indicate the control RMP (VControl), and the dashed blue lines indicate the membrane potential during L6 activation (VL6). LTS sizes were estimated from whisker EPSP magnitudes in control and L6 trials. (E) Population cell-by-cell (n = 13) comparison of median EPSPWhisker and EPSPL6 for single whisker deflections. (F) Comparison between EPSPcontrol (black circles) and EPSPL6 (blue circles) from the same recordings shown in E. EPSP magnitudes were correlated with membrane potential (Vcontrol or VL6); r = −0.57. The line shows the linear best fit. (G) L6-induced decrease in whisker response (EPSPL6 − EPSPWhisker) is correlated with underlying L6-induced depolarization (VL6 − Vcontrol); r = −0.79. The line shows the linear best fit. Small changes in RMP by L6-activation led to small changes in EPSP magnitude, whereas larger L6-induced depolarization led to more marked decreases in EPSP magnitude.

To investigate the effect of L6 on whisker EPSPs more systematically for all recordings, we measured the whisker-evoked EPSP peak amplitudes and baseline membrane potential (Fig. 3D) with and without L6 activation. L6 activation reliably decreased EPSP size (Fig. 3E), and, furthermore, EPSP size was dependent on the baseline membrane potential (Fig. 3F), as would be expected from both the decreased availability of IT and the decrease in driving force brought about by L6-induced depolarization. Taken together, these two observations show that the effect of L6 on sensory responses is correlated with the strength of L6-induced depolarization (Fig. 3G).

The IT-mediated LTS and its graded amplitude (17) determines the number of spikes per response; as a consequence, thalamic firing modes are not binary (see also Fig. 2 C–E), but rather reflect the variable size of the LTS. Even with L6 stimulation, a small LTS could still be observed, as is consistent with the presence of functionally relevant IT even at depolarized RMPs (29, 30). Thus, L6 affects the response mode to sensory stimuli by controlling the size of the thalamic LTS.

L6 activation induced tonic firing in response to current injection (Fig. S7A), and similarly, tonic firing could be promoted via direct current depolarization alone (Fig. S7B). These controls further support the finding that L6 activity leads to a smaller LTS and fewer burst APs by inducing a more positive RPM. In summary, L6 input to VPM neurons decreases burstiness by inactivating T-type Ca2+ channels via depolarization, in line with the dependence of burst firing on T-type Ca2+ channels and the biophysical properties of thalamic relay neurons (17, 28, 31).

These intracellular experiments also demonstrate the mechanisms underlying the observed reduction in the probability of a response (Fig. 1F). First, activation of L6 reduced the input resistance in VPM neurons (Fig. S6B), most likely as a consequence of increased conductance through the direct depolarization by L6 reported above and also by disynaptic inhibition via TRN. Furthermore, the decrease in EPSP size caused by L6 was not always entirely compensated by the net depolarization by L6 (Fig. S6C). A given synaptic input thus will cause a smaller absolute depolarization when L6 is active. Together, the reduced probability of response in combination with the reduced burstiness may represent a cortical mechanism for controlling gain in thalamic responses, because L6 lowered sensory-related spike rates for temporally isolated stimuli.

Thalamic Adaptation Is Reduced by L6 Activation.

Behaviorally relevant inputs for mice and rats are sequences of whisker stimuli that occur when a mouse rhythmically moves its whiskers during exploration and when the whiskers are swept along objects with uneven surfaces (32). As in other sensory thalamo–cortical systems, VPM neurons exhibit characteristic rapid adaptation to sensory inputs (6, 33, 34). One cause of this adaptation is the strong depression of synapses between the brainstem and VPM, which results in a successive decrease in EPSP magnitude (6). As a consequence of this rapid adaptation, spiking in response to initial stimuli is highly probable, but later stimuli in a sequence are transmitted less reliably.

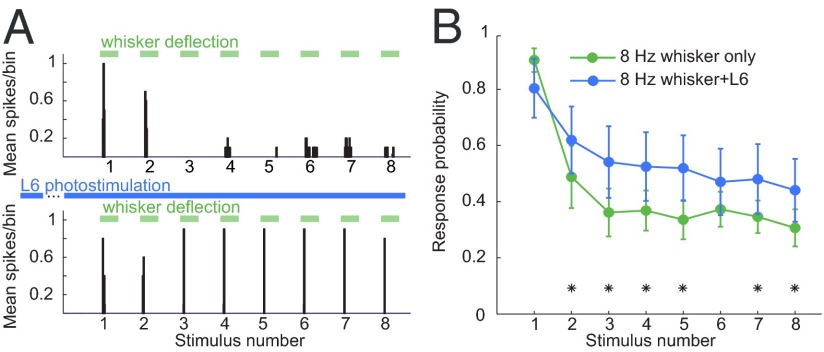

A series of foundational papers has shown that brainstem stimulation effectively reduces sensory adaptation in the VPM via depolarization (6, 7). We hypothesized that the observed depolarization from L6 controls not only the firing mode but also the adaptation in the VPM. To test this possibility, we repeated our stimulation protocol as before but stimulated the whisker repetitively at 8 Hz, a frequency known to evoke adaptation (6, 34). We first measured the corresponding spike responses in the juxtacellular configuration in the control condition and with L6 activation. We observed a spectrum of adaptation in our sample; we categorized neurons as adapting if the proportion of whisker stimuli that elicited a spike response was lower in the last stimulus than in the first stimulus of the train (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.05). Using this conservative criterion, we found that most (n = 14/22) VPM neurons exhibited adaptation in response to repetitive stimuli. The spike responses to 8-Hz whisker deflection in one VPM neuron are shown in the upper panel of Fig. 4A. When the same stimulus was repeated in combination with L6 activation, the probability of response to successive stimuli was increased by a factor of ∼1.4 (Fig. 4A, Lower). Similar results were seen in all adapting neurons (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Activation of L6 alters the relay of high-frequency sensory stimuli. VPM neurons were stimulated with 8-Hz whisker deflection trains (green bars) with and without L6 photoactivation (blue bars). (A, Upper) PSTH of a VPM neuron’s spiking response in control condition. (Lower) Response to the same stimulus during L6 photostimulation (blue bars) starting 200 ms before the whisker deflection train. (B) Population average of the probability of VPM spike responses (n = 10) for control trials (green trace) and during L6 stimulation (blue trace). Asterisks indicate response probabilities that were changed significantly by L6 activation (Methods).

Cellular Mechanism Underlying L6 Control of Thalamic Adaptation.

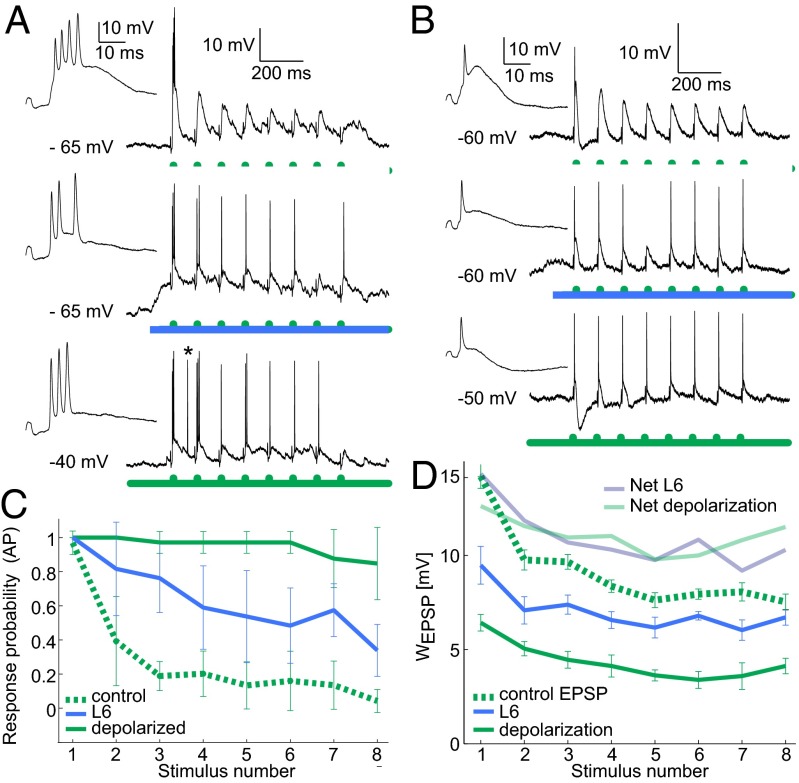

To reconcile the apparently contradictory findings that L6 both decreases thalamic spike output to isolated stimuli (Figs. 2 and 3) and decreases adaptation (Fig. 4), we recorded responses to repetitive stimuli in a whole-cell configuration. Fig. 5 A and B shows examples of sub- and suprathreshold responses to an 8-Hz whisker stimulus train from a bursty and a tonic neuron, respectively and the effect of L6 activation on their adapting responses. Whisker APs in the control condition (Fig. 5 A and B, Top) showed immediate adaptation, paralleled by regularly decreasing EPSPs for successive stimuli. For the same stimulus in combination with L6 activation (Fig. 5 A and B, Middle, blue), the probability of spiking increased for later stimuli. Furthermore, L6 activation both decreased and regularized the EPSP magnitude across successive stimuli. We could mimic these effects of L6 activation by elevating the RMP with current injections via the patch pipette (Fig. 5 A and B, Bottom). Fig. 5C shows the average probabilities of spiking across the population for these three conditions, demonstrating a clear decrease in adaptation with either L6 or direct current-induced depolarization.

Fig. 5.

L6 activity enhances the relay of frequency stimuli by reducing supra- and subthreshold adaptation and decreasing distance to threshold. (A, Top) Intracellular response to 8-Hz whisker deflection (green). (Middle) Response to the same whisker stimulus but with activated L6. (Bottom) Response to the same whisker stimulus from elevated membrane potential (injected current: 350 pA; spontaneous AP marked with asterisk.). Insets show responses to the first whisker deflection at higher time resolution. (B) As in A but for a neuron that fired mostly tonic APs in control conditions. (C) Summary of AP probabilities for the three conditions in A and B from five VPM neurons. Green dashed line: whisker stimulation alone; blue solid line: whisker + L6 stimulation; green solid line: whisker stimulation + injected current (300–450 pA). Error bars indicate SD. (D) EPSP quantification for a sample VPM whole-cell recording with 8-Hz whisker stimulation alone (green dashed line), whisker + L6 stimulation (blue), or injected current sufficient to depolarize the cell to −40 mV (green solid line). L6 activation and depolarization decreased EPSP magnitude and subthreshold adaptation between successive stimuli. Mean magnitudes are shown; error bars show SD. Depolarization compensates for decreased EPSP magnitude: Light blue and light green traces show the net sum of depolarization and mean EPSP magnitude for L6 activation or depolarization, respectively. EPSP magnitude and depolarization were quantified as in Fig. 3D.

To investigate the seemingly counterintuitive decrease in EPSP size and increase in AP probability for later stimuli during L6 activation, we analyzed EPSP magnitudes across successive stimuli as well as the baseline membrane potential in the control, L6 activation, and depolarized conditions (Fig. 5D) for a strongly adapting neuron. This analysis revealed that although EPSP magnitude decreased when the neuron was depolarized by L6 activation or via current injection, EPSP magnitude showed less frequency-dependent adaptation, and, most critically, the sum of EPSP magnitude and baseline depolarization (“net” traces in Fig. 5D) was greater with L6 stimulation (or current injection) compared to control EPSPs. Thus, L6 activation decreases spiking adaptation in two ways: (i) by reducing the voltage distance to the AP threshold, and (ii) by reducing the relative adaptation at the subthreshold level, most likely by decreasing the contribution of IT-mediated adaptation.

Apart from depolarization, we also found that L6 input increased the fluctuations in the membrane potential (Fig. S8 and SI Discussion), most likely as a result of increased and asynchronous synaptic activity from many L6 neurons. Increased noise affects thalamo–cortical information transfer (35) by increasing the dynamic range of thalamic input/output curves and thereby increasing the probability of response to small stimuli. Thus, increased membrane potential fluctuations may be an additional mechanism by which L6 gates the relay of high-frequency whisker inputs, despite a decrease in subthreshold EPSP magnitude.

Discussion

The results demonstrate a critical role for L6 in controlling thalamic signal transformations during the processing of tactile stimuli. Upon activation, the L6 pathway reduced thalamic adaptation, thereby gating the relay of high-frequency sensory inputs. Secondly, L6 activation shifted thalamic responses toward tonic firing. Intracellular data suggest that L6 regulates both these thalamic input/output properties via changes in RMP and the concomitant availability of IT and an increase in membrane potential fluctuations.

Cortical L6 Control of Thalamic Firing Modes.

Although the causal links between RMP, IT, and thalamic response mode have been established firmly since the fundamental work of Jahnsen and Llinás (17, 18, 28), we demonstrate here that L6-mediated depolarization (19) acts as an effective regulator of thalamic relay modes and adaptation during sensory processing. IT is a graded conductance which inactivates with depolarization; however, as shown recently, IT not only is available but also is functionally relevant even at depolarized RMPs (29, 30). Our data show that L6 activity does not abolish the IT-mediated calcium spiking but significantly decreases its amplitude, with the result that fewer burst APs are fired. Hence, L6 shifts rather than switches the thalamic target neurons toward the tonic mode. These shifts may be more subtle in the awake animal because of the overall variability of membrane potential and may be spatially more precise because of the topographical alignment of L6, TRN, and the VPM. Optogenetic stimulation evokes a level of synchronized activity which is rarely found in the awake cortex. Thus, the principal actions of L6 on thalamic input/output properties which are described here likely also will apply in awake conditions but in a more refined and spatio-temporally precise manner.

We found a continuum of firing modes across the population of VPM neurons under control conditions rather than a discrete thalamic burst state. Earlier studies suggested that bursts represent an operational state in which thalamic relay of sensory information is suppressed by sensory decoupling (36). However, the coexistence of burst and tonic sensory responses reported here is in line with other studies in anesthetized and awake animals which demonstrate that sensory information is encoded through both tonic and burst spikes (10, 37). Furthermore, bursts have been shown to be part of the sensory response during active tasks (8, 11, 16), and bursts are systematically related to the sensory input (Fig. 2); this relationship would not be expected if sensory relay is suppressed by bursts (38).

The transitions between firing modes are dynamic and are extremely fast in the anesthetized and awake thalamus (15, 16), prompting questions about the regulatory mechanisms for fast control. The data presented here suggest that the L6 cortico–thalamic pathway might be unique in allowing such fast control. Brainstem activation can promote tonic responses and reduce adaptation in the thalamus as well (6, 7, 39). However, the spatially diffuse acetylcholine action of brainstem inputs which activates slow muscarinic receptors in the VPM may represent the overall level of vigilance and modulate the thalamus globally on slow time scales. In contrast, spatially and temporally precise changes in firing mode and adaptation likely are under L6 control because of the topographical precision of cortico–thalamic axons (40, 41). These results somewhat contrast with a study by Olsen et al. (23) in the visual thalamus in which tonic mode shifts by L6 were observed but did not reach significance level (SI Discussion).

Cortical L6 Control of Thalamic Adaptation.

The central result of this study is that L6 gates frequency information through the thalamus by reducing sensory adaptation via depolarization and RMP fluctuations. The depolarization not only increased the chance that depressed EPSPs triggered APs but also removed the contribution of IT to EPSP adaptation. Finally, the L6-induced increase in membrane potential fluctuations (Fig. S8 and SI Discussion) may further tune thalamic burstiness and adaptation (35).

Response adaptation is a key feature of sensory systems (1, 2) including VPM (6, 33, 34) where adaptation prevents the relay of high-frequency tactile information. VPM inputs to the cortex (42) activate L6 during whisker stimulation (25, 43), suggesting that tactile activity itself is important for L6-mediated gating of frequency cues. In this manner, L6 may provide a top-down attentional signal that turns on a fine-detail examination mode critical for behavioral tasks such as texture discrimination.

Functional Implications.

Activation of L6 reduced both the number of spikes (Fig. 2C) and the spiking probability (Fig. 2F) in response to whisker input, and in addition increased spontaneous spiking in half of the neurons. Together, these effects may represent a thalamic gain control in which L6 feedback reduces the sensory-evoked thalamocortical spike rate. The resulting decrease in the signal to noise ratio at first may seem to contradict the association of tonic mode with active sensing states. The growing evidence that both bursts and tonic spikes are part of active sensory transmission led to the formulation of the searchlight (14) and wake-up-call (13) hypotheses. In this framework, thalamic bursts represent strong cortical inputs as the thalamo–cortical firing rate transiently peaks and alerts the cortex that something new (e.g., an object) has entered the sensory scenery. However, because of its highly nonlinear input–output properties, the burst relay mode lacks encoding bandwidth to convey information other than the occurrence of a new stimulus. In contrast, tonic firing has a smaller signal-to-noise ratio but enables increased coding bandwidth to relay details of the stimulus (e.g., size, shape, color, and frequency). In line with these hypotheses, we found that L6 increases the transfer of frequency information through the thalamus at the expense of the detectability of novel stimuli.

In summary, cortical L6 controls the processing of sensory signals across the thalamo–cortical system by affecting the depolarization level, membrane potential noise, and conductance of target thalamic neurons. Taking the topographical projections from L6 to the thalamus into account, this activity may represent an attentional signal which toggles the thalamo–cortical systems between detection and sampling mode in a rapid and spatially precise way in order to maintain sensitivity to the dynamics of the sensory environment.

Methods Summary

The full methods can be found in SI Methods. Expression of ChR2 was stereotaxically targeted to cortical layer 6 neurons (Ntsr1) using virus mediated gene transfer allowing fast optogenetic activation of the L6 corticothalamic pathway. Single neuron recordings in juxtasomal and whole-cell intracellular configuration were done in the VPM thalamus of anaesthetized adult Ntsr1 mice using an ELC-01X amplifier (NPI Electronics). Single whisker stimulation was done using an electronically controlled piezo wafer. Data was recorded with Spike2 (CED) and analyzed with custom-written Matlab software (MathWorks).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Schmidt and Nathaniel Heintz for providing the Ntsr1 line and László Acsády and Manuel Castro-Alamancos for helpful comments on the manuscript. P.K. was funded by SFB 874 from the German Research Foundation (DFG). A.G. and R.A.M. were funded by the Max-Planck Society and supported by Arthur Konnerth and Bert Sakmann. This project was funded by DFG Grant GR3757/1-1.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1318665111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fairhall AL, Lewen GD, Bialek W, de Ruyter Van Steveninck RR. Efficiency and ambiguity in an adaptive neural code. Nature. 2001;412(6849):787–792. doi: 10.1038/35090500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wark B, Lundstrom BN, Fairhall A. Sensory adaptation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17(4):423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow H. Possible Principles Underlying the Transformation of Sensory Messages. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond ME, Armstrong-James M, Ebner FF. Somatic sensory responses in the rostral sector of the posterior group (POm) and in the ventral posterior medial nucleus (VPM) of the rat thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1992;318(4):462–476. doi: 10.1002/cne.903180410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons DJ, Carvell GE. Thalamocortical response transformation in the rat vibrissa/barrel system. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61(2):311–330. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro-Alamancos MA. Properties of primary sensory (lemniscal) synapses in the ventrobasal thalamus and the relay of high-frequency sensory inputs. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(2):946–953. doi: 10.1152/jn.00426.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro-Alamancos MA. Different temporal processing of sensory inputs in the rat thalamus during quiescent and information processing states in vivo. J Physiol. 2002;539(Pt 2):567–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramcharan EJ, Gnadt JW, Sherman SM. Burst and tonic firing in thalamic cells of unanesthetized, behaving monkeys. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17(1):55–62. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800171056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halassa MM, et al. Selective optical drive of thalamic reticular nucleus generates thalamic bursts and cortical spindles. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(9):1118–1120. doi: 10.1038/nn.2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guido W, Weyand T. Burst responses in thalamic relay cells of the awake behaving cat. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74(4):1782–1786. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.4.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanselow EE, Sameshima K, Baccala LA, Nicolelis MA. Thalamic bursting in rats during different awake behavioral states. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(26):15330–15335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261273898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slezia A, Hangya B, Ulbert I, Acsady L. Phase advancement and nucleus-specific timing of thalamocortical activity during slow cortical oscillation. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):607–617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3375-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman SM. Tonic and burst firing: Dual modes of thalamocortical relay. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24(2):122–126. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crick F. Function of the thalamic reticular complex: The searchlight hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81(14):4586–4590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guido W, Lu SM, Sherman SM. Relative contributions of burst and tonic responses to the receptive field properties of lateral geniculate neurons in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68(6):2199–2211. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.6.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bezdudnaya T, et al. Thalamic burst mode and inattention in the awake LGNd. Neuron. 2006;49(3):421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahnsen H, Llinás R. Electrophysiological properties of guinea-pig thalamic neurones: An in vitro study. J Physiol. 1984;349:205–226. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jahnsen H, Llinás R. Voltage-dependent burst-to-tonic switching of thalamic cell activity: An in vitro study. Arch Ital Biol. 1984;122(1):73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCormick DA, von Krosigk M. Corticothalamic activation modulates thalamic firing through glutamate “metabotropic” receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(7):2774–2778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Connor DH, Huber D, Svoboda K. Reverse engineering the mouse brain. Nature. 2009;461(7266):923–929. doi: 10.1038/nature08539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groh A, et al. Cell-type specific properties of pyramidal neurons in neocortex underlying a layout that is modifiable depending on the cortical area. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(4):826–836. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gong S, et al. Targeting Cre recombinase to specific neuron populations with bacterial artificial chromosome constructs. J Neurosci. 2007;27(37):9817–9823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2707-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen SR, Bortone DS, Adesnik H, Scanziani M. Gain control by layer six in cortical circuits of vision. Nature. 2012;483(7387):47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature10835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee CC, Lam YW, Sherman SM. Intracortical convergence of layer 6 neurons. Neuroreport. 2012;23(12):736–740. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328356c1aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oberlaender M, et al. Cell type-specific three-dimensional structure of thalamocortical circuits in a column of rat vibrissal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(10):2375–2391. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam YW, Sherman SM. Functional organization of the somatosensory cortical layer 6 feedback to the thalamus. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(1):13–24. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landisman CE, Connors BW. VPM and PoM nuclei of the rat somatosensory thalamus: Intrinsic neuronal properties and corticothalamic feedback. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(12):2853–2865. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jahnsen H, Llinás R. Ionic basis for the electro-responsiveness and oscillatory properties of guinea-pig thalamic neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1984;349:227–247. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deleuze C, et al. T-type calcium channels consolidate tonic action potential output of thalamic neurons to neocortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32(35):12228–12236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1362-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tscherter A, et al. Minimal alterations in T-type calcium channel gating markedly modify physiological firing dynamics. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 7):1707–1724. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.203836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J, et al. Sleep spindles are generated in the absence of T-type calcium channel-mediated low-threshold burst firing of thalamocortical neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(50):20266–20271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320572110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe J, et al. Texture coding in the rat whisker system: Slip-stick versus differential resonance. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(8):e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deschênes M, Timofeeva E, Lavallée P. The relay of high-frequency sensory signals in the Whisker-to-barreloid pathway. J Neurosci. 2003;23(17):6778–6787. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06778.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahissar E, Sosnik R, Haidarliu S. Transformation from temporal to rate coding in a somatosensory thalamocortical pathway. Nature. 2000;406(6793):302–306. doi: 10.1038/35018568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolfart J, Debay D, Le Masson G, Destexhe A, Bal T. Synaptic background activity controls spike transfer from thalamus to cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(12):1760–1767. doi: 10.1038/nn1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livingstone MS, Hubel DH. Effects of sleep and arousal on the processing of visual information in the cat. Nature. 1981;291(5816):554–561. doi: 10.1038/291554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weyand TG, Boudreaux M, Guido W. Burst and tonic response modes in thalamic neurons during sleep and wakefulness. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85(3):1107–1118. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinagel P, Godwin D, Sherman SM, Koch C. Encoding of visual information by LGN bursts. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(5):2558–2569. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu SM, Guido W, Sherman SM. The brain-stem parabrachial region controls mode of response to visual stimulation of neurons in the cat’s lateral geniculate nucleus. Vis Neurosci. 1993;10(4):631–642. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800005332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krahe R, Gabbiani F. Burst firing in sensory systems. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(1):13–23. doi: 10.1038/nrn1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Temereanca S, Simons DJ. Functional topography of corticothalamic feedback enhances thalamic spatial response tuning in the somatosensory whisker/barrel system. Neuron. 2004;41(4):639–651. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer HS, et al. Cell type-specific thalamic innervation in a column of rat vibrissal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(10):2287–2303. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Kock CP, Bruno RM, Spors H, Sakmann B. Layer- and cell-type-specific suprathreshold stimulus representation in rat primary somatosensory cortex. J Physiol. 2007;581(Pt 1):139–154. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.