Abstract

Unspliced Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) retroviral mRNA undergoes nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) if it has premature termination codons in the gag gene. However, its normal gag termination codon is not subject to NMD despite being 7 kb from the 3’ poly(A) sequence. An RNA stability element (RSE) has been identified immediately downstream of gag in the RSV genome. It appears to determine the proper context for translation termination and protects the RNA from NMD. The viral stability element may prevent Up-frameshift 1 (Upf1) protein from interacting with the terminating ribosome and release factors to initiate NMD.

Introduction

Viruses are obligate parasites with compact genomes that depend on host cells for replication. Retroviruses have compact genomes of less than 10 kilobases (kb), yet they code for 8 or more viral proteins. In contrast, most single cellular genes are much larger than this, due to numerous large introns. Retroviruses use a combination of gene expression mechanisms, including alternative splicing, frame-shifting and polyprotein cleavage to generate multiple gene products from a single primary RNA transcript [1]. The major unspliced retroviral mRNAs have features not commonly found in cellular mRNAs, including long 3’ untranslated regions (3’ UTRs), retained introns, and upstream open reading frames (uORFs). These unusual features predispose the viral RNA towards degradation by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), which is part of the cellular RNA surveillance system. Nevertheless, the unspliced RNA of Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), a well-studied avian retrovirus, is very stable [2], suggesting the virus has evolved a means to overcome degradation by NMD.

NMD was originally proposed to be responsible for degrading aberrant transcripts containing premature termination codons (PTCs), thus protecting cells from the deleterious effects of C-terminal truncated proteins [3]. However, it also seems to provide a mechanism for regulating levels of expression of alternatively spliced mRNAs [4].

Are downstream EJCs necessary for NMD?

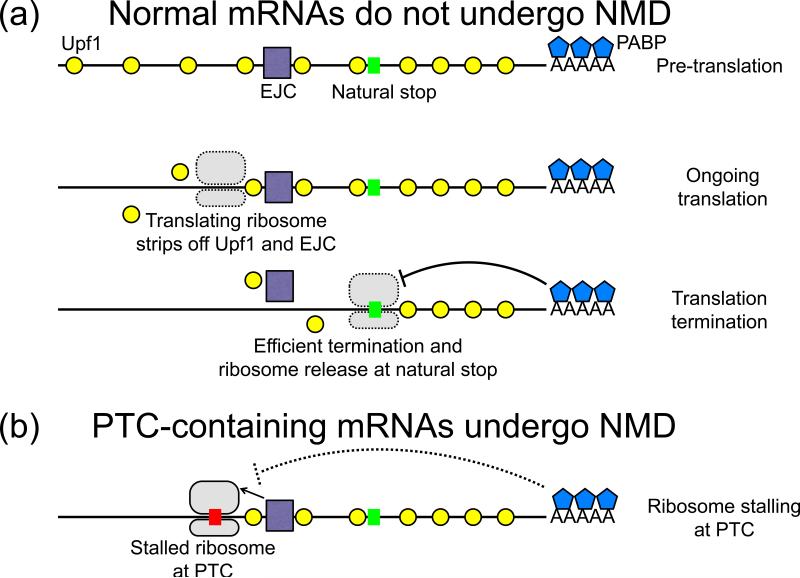

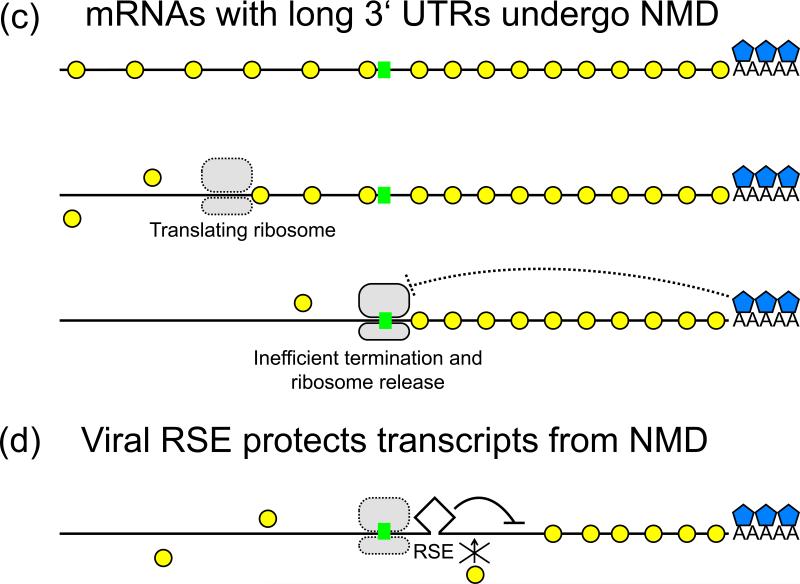

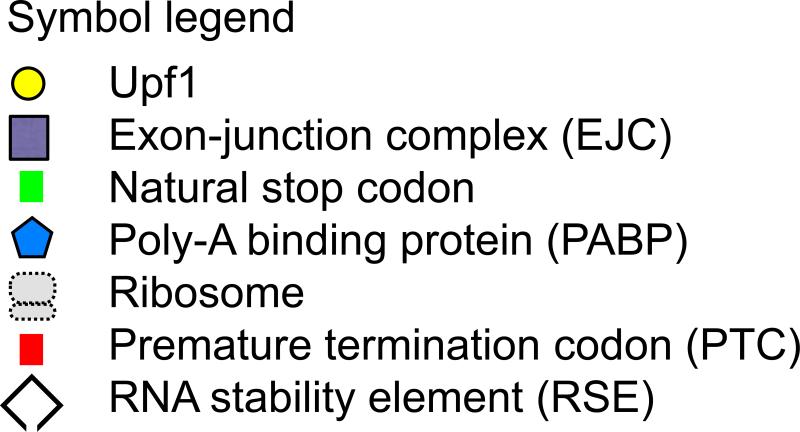

Canonical NMD in mammalian cells posits that the process is mediated by the interaction between the terminating ribosome at a PTC and a downstream exon-junction complex (EJC), the multi-protein complex deposited 20-24 nts upstream of the exon-exon junction during RNA splicing [5]. (See Fig. 1b, compared to 1a.)However, examples of EJC-independent NMD exist in mammals and are the rule in lower organisms. Some, but not all, mRNAs bearing features such as uORFs and long 3’ UTRs are NMD targets, both in mammals and in yeast. Unspliced (thus presumably lacking EJCs) retroviral mRNAs are also targets of NMD [6]. NMD has been shown to play regulatory roles in humans, Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Saccromyces cerevisiae [4], and can affect more than a quarter of all expressed mammalian genes [7,8].

Fig 1. Upf1 binding and NMD of various transcripts.

(a) A normal mRNA is bound by EJCs in the coding region and by Upf1 across the transcript. The translating ribosome strips off Upf1 and EJCs from the coding sequence. At the natural stop codon, translation termination is efficient. Coupled with interactions with the proximal PABPs, ribosome disassembly is rapid and NMD factors are not recruited. The mRNA is stable. (b) At a premature termination codon (PTC), translation termination is inefficient. The distance to the poly(A) tail prevents PABP intervention, and the stalling ribosome interacts with downstream EJCs and Upf1 to signal NMD. The transcript is degraded. (c) For mRNAs with long 3’ UTRs, the terminating ribosome is far from the poly(A) tail and PABP. Additionally, increased Upf1 binding in the 3’ UTR increases chances of interaction with the ribosome. This makes the mRNA susceptible to NMD. (d) Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) RNA Stability Element (RSE) protects the viral mRNA from NMD, possibly by preventing Upf1 protein binding to the viral RNA and circumventing its interactions with the terminating ribosome. The RSE might also promote faster release of the ribosome such that NMD factors are not recruited in time for degradation.

Metze et al [9] compared “EJC-enhanced” and “EJC-independent” NMD in mammalian cells, and showed that they represented two partially redundant degradation pathways, each requiring different NMD factors. Nonetheless, all PTC-containing mRNAs are degraded in a Smg1- and Up-frameshift 1 protein (Upf1)-dependent manner, regardless of the presence or absence of a downstream EJC. The EJC could serve as a non-essential NMD enhancer by increasing translation efficiency, a role that has previously been demonstrated [10].

Saulière et al [11] and Singh et al [12] recently monitored EJC binding across the transcriptome in HeLa and HEK293 cells, respectively. These studies showed that canonical EJCs are only detected at 80% of exon junctions and at varying occupancy levels, so that many individual mRNAs lack EJCs at many exon junctions. Surprisingly, almost half of all mapped EJC binding sites were found distributed across the mRNA coding sequence at non-canonical sites rather than at the exon junctions [11,12]. SR proteins are serine/argine-rich RNA binding proteins that recruit splicing factors. Saulière et al [11] observed an enrichment of the SR protein consensus binding motif GAAGA near the mapped EJC binding sites, and showed that SRSF1(ASF/SF2) and SRSF7 physically associate with EJCs [11]. Similarly, Singh et al found that multiple EJCs were often associated with many SR proteins in large complexes [12]. This interaction between EJCs and SR proteins could explain the previously observed promotion of NMD by overexpression of the SR protein ASF/SF2 [13]. These experiments blurs the distinction between the two branches of NMD [9], as transcripts with downstream introns may not have EJCs occupying them and transcripts thought to undergo EJC-independent NMD may in fact possess non-canonical EJCs. Most transcripts carry both canonical EJCs and non-canonical EJCS [11,12]. However, EJCs are rarely seen in the UTRs or in intronless mRNAs.

PABP stabilizes RNA

A different model was put forward to explain how yeast cells discriminate between normal and aberrant termination codons. (See Fig. 1c, compared to 1a.) Long 3’ UTRs were shown early on to be associated with NMD in yeast, leading to the faux UTR model [14]. Since cytoplasmic poly(A) binding proteins (PABPC1) near a terminating ribosome can prevent NMD [15], it was proposed that long 3’ UTRs induce NMD by distancing the PABPs from the terminating ribosome. Studies with recombinant mRNAs in Drosophila also showed the importance of a short distance between a termination codon and poly(A) for stable mRNA [16]. While Drosophila has EJCs, they do not seem important for NMD [16]. Some mammalian mRNAs with long 3’UTRs could be protected from NMD by looping the 3’ UTR via base-pairing to bring the poly(A) tail close to the termination codon [17]. Similarly, tethering PABP near a PTC also stabilizes the mRNA. [17,18].

How does UPF1 recognize target RNAs?

The key component of the NMD pathway is the RNA helicase Upf1, but it is not well known how Upf1 recognizes and binds its targets. Recent work has attempted to answer that question. Hogg and Goff showed that Upf1 directly binds to 3’ UTRs of several mRNAs (HIV-1, Smg5 and GAPDH) in a length-dependent, translation-independent manner [19]. In contrast, Kurosaki and Maquat reported that Upf1 binding to non-PTC-containing β-globin constructs does not correlate with 3’ UTR length [20]; however, their constructs had relatively short 3’ UTRs. Further, transcripts that contain PTCs or downstream EJCs demonstrate augmented Upf1 binding, and this enhanced binding is dependent on translation. They propose that Upf1 is loaded onto 3’ UTRs of PTC-containing mRNAs at the terminating ribosome [20].

Two recent studies interrogated Upf1 binding across the transcriptome in murine embryonic stem cells (mESCs) and HeLa cells [21,22]. Both studies found that Upf1 preferentially binds the 3’ UTR at up to 10 times higher levels than the coding sequence. The binding is relatively uniform across the 3’ UTR; however, both groups observed clustering in specific locations in individual transcripts. In addition, Hurt et al observed a binding preference for G-rich sequences and RNA regions with secondary structure, while Zünd et al noted enrichment at U-rich sequences. Notably, translation inhibition causes a dramatic increase in Upf1 binding to the coding sequence. Upf1 also binds long nonconding RNAs (lncRNAs). Thus, in contrast to current models proposing that Upf1 is specifically recruited to the 3’ UTR by ribosomes, these studies suggest that Upf1 is uniformly bound across transcripts and is displaced by the translocating ribosome. This implies that Upf1 binding happens prior to the selection of NMD targets. Accordingly, Zünd et al do not observe a preference for Upf1 binding to NMD targets [21].

Nonetheless, it is still unclear how 3’ UTR length functions as a determinant of NMD susceptibility in this model and how increased Upf1 binding promotes NMD and increases decay efficiency. One possible model is that Upf2 and Upf3 find and bind the RNA-bound Upf1 through diffusion [4]. This primes the Upf1-Upf2-Upf3 complex for signaling decay upon interaction with the terminating ribosome. Longer 3’UTR's usually bind more Upf1 [23] and have an increased probability of interacting with diffusing Upf2 and Upf3 factors.

Alternative polyadenylation

Cellular mechanisms exist to modulate 3’ UTR length, which may affect mRNA localization and translational efficiency, in addition to its stability. Deletions within the 3’ UTR, as well as point mutations that lead to premature cleavage and polyadenylation, alter 3’ UTR length and sequence [24,25]. Chromosomal translocations have also been shown to result in 3’ UTR swapping between genes [26]. In addition, alternative cleavage and polyadenylation (APA) is a recently studied post-transcriptional regulation mechanism [26-28]. Most genes contain multiple polyadenylation signals, in both the 3’ UTR and the coding sequence. Use of an APA signal in the coding sequence will generate different protein isoforms, whereas use of different APA signals in the 3’ UTR will yield mRNA isoforms with varying 3’ UTR lengths and associated regulatory elements. In humans, APA signals are used in half of all genes [29,30].

Retroviral mechanisms to avoid NMD

Unlike mammalian mRNAs, retroviral mRNAs cannot modulate their stability via APA because they must maintain full-length genomic RNA. The full-length, unspliced transcript serves as the RNA genome for progeny virions as well as the mRNA for structural (gag) and enzymatic (pol) viral proteins [1]. RSV is a simple avian retrovirus with three viral RNAs, generated from the primary transcript by alternative splicing. The full-length RSV mRNA contains several NMD-triggering features, including uORFs and a long 3‘ UTR. However, the RNA is stable in chicken cells and has a long half-life of about 20 hours [2], suggesting it has evolved a mechanism to avoid degradation by NMD.

Studies of mouse HSP70 and human histone H4 unspliced mRNAs found that they were resistant to NMD [31], leading to the proposal that all unspliced mammalian mRNAs are resistant. On the other hand, most S. cerevisiae mRNAs are not spliced, yet they are subject to NMD [32]. Additionally, RSV unspliced RNA with frameshift mutations or PTCs in the gag gene is rapidly degraded in a Upf1- and translation-dependent manner, showing that the transcript is recognized as an NMD substrate, albeit in chicken cells [2,33].

Neither the EJC model from mammalian cells or the long 3’ UTR model from yeast/drosophila seemed adequate to explain the mechanism of NMD of RSV mRNA. Since the mRNA does not have introns and is unspliced, it was not thought to have EJCs. In addition, the normal gag termination codon is 7 kb away from the poly(A) tail, generating a very long 3’ UTR but a stable RNA. In contrast, insertion of a PTC 100 nts or more upstream of the normal termination codon results in degraded mRNA [2]. Thus, the distance from poly(A) did not seem to be a key determinant here.

The finding that PTCs within 100 nts upstream of the normal gag termination codon showed partial RNA stability [2] suggested that the sequences downstream of the termination codon could be significant in creating a proper context for translation termination. Deletion experiments led to the identification of a 400 nt cis-acting RNA element in RSV located immediately downstream of gag, termed the RSV RNA stability element (RSE) [34]. The RSE, which contains redundant sub-elements and a minimal 155 nt core, stabilizes the full-length mRNA and protects it from NMD [34,35]. Deletion or inversion of this sequence destabilizes the RNA; stability can be rescued by expression of a trans-dominant Upf1 mutant to inactivate the NMD pathway [34]. Insertion of the RSE after a PTC in gag also rescues the RNA from decay [34], showing that the RSE can convert an aberrant termination codon to one recognized as correct by altering the downstream RNA context.

Alignment of the genomes 20 different avian retrovirus strains shows that the sequence and secondary structure of the RSE is well conserved [36]. This suggests that the RSE may be a mechanism that certain viruses have evolved to evade host cell RNA surveillance and to stabilize their genome. Work is currently underway to determine if other retroviruses possess RSEs. In addition, the RSE may be present among the repertoire of RNA regulation methods in a cell. RNAs with long 3’ UTRs that escape NMD occur naturally in the cell, for instance Cript1 and Tram1 [18]. It is possible that they may also have stability elements downstream of their termination codons.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the RSV RSE confers a novel mode of protection from NMD. The exact mechanism of protection is currently being studied. In light of all current information in the field, we propose a model (see Fig. 1d) whereby the RSE inhibits NMD by providing an umbrella of protection that prevents Upf1 binding within its protected zone, either through structural features that prevent Upf1 binding or by recruiting other competing factors to the site. This would buffer the terminating ribosome from downstream Upf1 molecules and prevent formation of the decay complex. Alternatively, the RSE could recruit factors to increase translation termination efficiency and speed up ribosome disassembly to achieve the same effect. Thus, the sequence immediately downstream of the correct viral termination codon, and its associated ribonucleoproteins, is important in validating that termination codon and preventing NMD. We think it is likely that stable cellular mRNAs with long 3’UTRs have evolved similar mechanisms.

Highlights.

Retroviral mRNAs are potential nonsense mediated mRNA decay (NMD) targets, but they are stable in cells

Exon-junction complexes bind coding sequences of transcripts, in addition to exon-exon junctions

Upf1 binds uniformly across transcripts and is stripped from the coding sequence by the translating ribosome

Alternative polyadenylation alters 3’ untranslated region length and distance to poly(A) tail

Avian retroviruses have evolved a novel mechanism of protection from NMD, involving an RNA stablility element downstream of the termination codon

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH RO1 CA048746 and P50 GM103297.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.LeBlanc JJ, Weil JE, Beemon K. Posttranscriptional regulation of retroviral gene expression: primary RNA transcripts play three roles as pre-mRNA, mRNA, and genomic RNA. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2013;4:567–80. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker GF, Beemon K. Rous sarcoma virus RNA stability requires an open reading frame in the gag gene and sequences downstream of the gag-pol junction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:1986–96. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoenberg DR, Maquat LE. Regulation of cytoplasmic mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012;13:246–59. doi: 10.1038/nrg3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schweingruber C, Rufener SC, Zünd D, Yamashita A, Mühlemann O. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay - mechanisms of substrate mRNA recognition and degradation in mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1829:612–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Hir H, Izaurralde E, Maquat LE, Moore MJ. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20-24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon-exon junctions. EMBO J. 2000;19:6860–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6*.Withers JB, Beemon KL. The structure and function of the Rous sarcoma virus RNA stability element. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jcb.23272. doi:10.1002/jcb.23272. [This review introduces the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) and provides a historical look at prior work done on the RSV RNA Stability Element (RSE).] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weischenfeldt J, Waage J, Tian G, Zhao J, Damgaard I, Jakobsen JS, Kristiansen K, Krogh A, Wang J, Porse BT. Mammalian tissues defective in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay display highly aberrant splicing patterns. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R35. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-5-r35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McIlwain DR, Pan Q, Reilly PT, Elia AJ, McCracken S, Wakeham AC, Itie-Youten A, Blencowe BJ, Mak TW. Smg1 is required for embryogenesis and regulates diverse genes via alternative splicing coupled to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:12186–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007336107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9*.Metze S, Herzog V a, Ruepp M-D, Mühlemann O. Comparison of EJC-enhanced and EJC-independent NMD in human cells reveals two partially redundant degradation pathways. RNA. 2013;19:1432–48. doi: 10.1261/rna.038893.113. [Using two sets of NMD reporter constructs with and without introns 3’ of their premature termination codons, the authors compared EJC-enhanced and EJC-independent NMD in HeLa cells under a battery of NMD factor depletion experiments via RNA-interference.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy B, Jacobson A. The intimate relationships of mRNA decay and translation. Trends Genet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.09.002. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11**.Saulière J, Murigneux V, Wang Z, Marquenet E, Barbosa I, Le Tonquèze O, Audic Y, Paillard L, Roest Crollius H, Le Hir H. CLIP-seq of eIF4AIII reveals transcriptome-wide mapping of the human exon junction complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:1124–31. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2420. [The authors mapped transcriptome-wide EJC binding sites in HeLa cells by performing crosslinking/immunoprecipitation-sequencing (CLIP-seq) on its core component eIF4AIII. This is one of two studies published concurrently that comprehensively investigates in vivo EJC binding profile. The study demonstrates the heterogeneity of EJC binding positions and occupancy level, and identifies an SR protein consensus binding motif near EJC binding sites.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12**.Singh G, Kucukural A, Cenik C, Leszyk JD, Shaffer S a, Weng Z, Moore MJ. The cellular EJC interactome reveals higher-order mRNP structure and an EJC-SR protein nexus. Cell. 2012;151:750–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.007. [Using RNA:immunoprecipitation in tandem (RIPiT) on EJC core proteins eIF4AIII and Magoh, the authors analyzed the EJC interactome in HEK293 cells. This is one of two studies published concurrently that comprehensively investigates in vivo EJC binding profile. In addition to EJC binding positions and occupancy level, the study shows that EJCs multimerize with one another and with SR proteins to form large complexes.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Krainer AR. Involvement of SR Proteins in mRNA Surveillance. 2004;16:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muhlrad D, Parker R. Aberrant mRNAs with extended 3’ UTRs are substrates for rapid degradation by mRNA surveillance. RNA. 1999;5:1299–307. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amrani N, Ganesan R, Kervestin S, Mangus D a, Ghosh S, Jacobson A. A faux 3’-UTR promotes aberrant termination and triggers nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature. 2004;432:112–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behm-Ansmant I, Gatfield D, Rehwinkel J, Hilgers V, Izaurralde E. A conserved role for cytoplasmic poly(A)-binding protein 1 (PABPC1) in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. EMBO J. 2007;26:1591–601. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eberle AB, Stalder L, Mathys H, Orozco RZ, Mühlemann O. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by spatial rearrangement of the 3’ untranslated region. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh G, Rebbapragada I. Lykke-Andersen J: A competition between stimulators and antagonists of Upf complex recruitment governs human nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19*.Hogg JR, Goff SP. Upf1 senses 3’UTR length to potentiate mRNA decay. Cell. 2010;143:379–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.005. [Using affinity purification of RNA constructs tagged with hairpin-based Pseudomonas phage 7 coat protein (PP7CP) binding site to isolate and characterize endogenously assembled mRNP complexes, the authors were the first to observe length-dependent, translation-independent Upf1 binding to RNA 3’ untranslated regions.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurosaki T, Maquat LE. Rules that govern UPF1 binding to mRNA 3’ UTRs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:3357–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219908110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Zünd D, Gruber AR, Zavolan M, Mühlemann O. Translation-dependent displacement of UPF1 from coding sequences causes its enrichment in 3’ UTRs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:936–43. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2635. [This is one of two transcriptome-wide studies that show Upf1 binding homogeneously across RNAs and that ribosomes strip Upf1 off coding regions during translation. The authors used individual-nucleotide-resolution UV cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (iCLIP) in HeLa cells and do not see a binding preference for nonsense-mediated RNA decay targets or a correlation with EJC binding sites.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Hurt J a, Robertson AD, Burge CB. Global analyses of UPF1 binding and function reveal expanded scope of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genome Res. 2013 doi: 10.1101/gr.157354.113. doi:10.1101/gr.157354.113. [This is one of two transcriptome-wide studies that show Upf1 binding homogeneously across RNAs and that ribosomes strip Upf1 off coding regions during translation. The study was done in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) using CLIP-seq. The authors find that Upf1 binding in 3’ UTRs can in itself contribute directly to NMD regardless of 3’ UTR length. They also find that the effects of EJC-enhanced NMD is strongest in transcripts with short 3’ UTRs, and that NMD only affects uORFs that are translated.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogg JR. This message was inspected by Upf1: 3’UTR length sensing in mRNA quality control. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:372–373. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.3.14735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiestner A, Tehrani M, Chiorazzi M, Wright G, Gibellini F, Nakayama K, Liu H, Rosenwald A, Muller-Hermelink HK, Ott G, et al. Point mutations and genomic deletions in CCND1 create stable truncated cyclin D1 mRNAs that are associated with increased proliferation rate and shorter survival. Blood. 2007;109:4599–606. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majoros WH, Ohler U. Spatial preferences of microRNA targets in 3’ untranslated regions. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayr C, Bartel DP. Widespread shortening of 3’UTRs by alternative cleavage and polyadenylation activates oncogenes in cancer cells. Cell. 2009;138:673–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji Z, Tian B. Reprogramming of 3’ untranslated regions of mRNAs by alternative polyadenylation in generation of pluripotent stem cells from different cell types. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandberg R, Neilson JR, Sarma A, Sharp PA, Burge CB. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3′ untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science. 2008;320:1643–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1155390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozsolak F, Kapranov P, Foissac S, Kim SW, Fishilevich E, Monaghan a P, John B, Milos PM. Comprehensive polyadenylation site maps in yeast and human reveal pervasive alternative polyadenylation. Cell. 2010;143:1018–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian B, Hu J, Zhang H, Lutz CS. A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:201–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maquat LE, Li X. Mammalian heat shock p70 and histone H4 transcripts, which derive from naturally intronless genes, are immune to nonsense-mediated decay. RNA. 2001;7:445–56. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kervestin S, Jacobson A. NMD: a multifaceted response to premature translational termination. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:700–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeBlanc JJ, Beemon KL. Unspliced Rous sarcoma virus genomic RNAs are translated and subjected to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay before packaging. J. Virol. 2004;78:5139–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5139-5146.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weil JE, Beemon KL. A 3’ UTR sequence stabilizes termination codons in the unspliced RNA of Rous sarcoma virus. RNA. 2006;12:102–10. doi: 10.1261/rna.2129806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Withers JB, Beemon KL. Structural features in the Rous sarcoma virus RNA stability element are necessary for sensing the correct termination codon. Retrovirology. 2010;7:65. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weil JE, Hadjithomas M, Beemon KL. Structural characterization of the Rous sarcoma virus RNA stability element. J. Virol. 2009;83:2119–29. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02113-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]