Abstract

Structurally complex genomic regions are not yet understood. One such locus, human 17q21.31, contains a megabase-long inversion polymorphism1, many uncharacterized copynumber variations (CNVs), and markers that associate with female fertility1, female meiotic recombination1–3, and neurological disease4,5. Additionally, the inverted H2 form of 17q21.31 appears to be positively selected in Europeans1. We developed a population-genetic approach to reveal complex genome structures and identified nine segregating structural forms of 17q21.31. Both the H1 and H2 forms of the 17q21.31 inversion polymorphism contain independently derived, partial duplications of the KANSL1 (KIAA1267) gene; these duplications, which produce novel KANSL1 transcripts, have both recently risen to high allele frequencies (26% and 19%) in Europeans. An older H2 form, lacking such a duplication, is present at low frequency in Europeans and Central African hunter-gatherer populations. We show that complex genome structures can be analyzed by imputation from SNPs.

Simple, common deletion and duplication polymorphisms have been typed in large cohorts6,7, found to segregate on SNP haplotypes6,7, and associated with many human phenotypes via proxy SNPs7–10. Complex structural mutations have also been described in specific patients and cancers11. By contrast, little is known about genomic loci that show population-level complexity –loci at which germline structural mutations in many different ancestors have given rise to complex patterns of variation. Such loci have not been analyzed in HapMap12,13 or the 1000 Genomes Project14,15, as they are assumed to require reconstruction of each structural form from genomic clones or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

We hypothesized that extensive structural information is present in the statistical relationships among genome structural features in populations. A population-genetic approach to reconstructing structural forms of a complex locus would require two capabilities. First, individual structural features would need to be accurately typed in population cohorts. This is increasingly possible, due to widely available genome sequence data14 and approaches for typing structural polymorphism in such data10. Second, it would be necessary to infer the haplotypes formed by multiple structural features; such relationships might be made visible in haplotype sharing by relatives or statistical phasing in populations. We sought to understand the extent to which such an approach could reveal genome structures at 17q21.31.

We first examined what structural features of 17q21.31 vary in populations. In addition to the known inversion at 17q21.311, we used array and whole-genome sequence (WGS) data to identify several segments of 17q21.31 that exhibit distinct patterns of population-level variation in copy number (Fig. 1a, Methods). We located most of the boundaries of these segments at high resolution by finding read-depth transitions and then (where possible) breakpoint-spanning reads in data from the 1000 Genomes Project pilot14 (Methods, Supplementary Fig. 1 Supplementary Table 1). This analysis defined three common, overlapping duplication polymorphisms: (i) duplication α, a 150-kb duplication (covering the 5’ end of the KANSL1 gene), previously partially characterized on the H2 haplotype of 17q21.3116; (ii) duplication β, a novel, longer (300 kb), duplication, overlapping duplication α, but segregating separately from it; and (iii) duplication γ, a highly multi-allelic 218-kb duplication at the distal end of the 17q21.31 inversion, covering much of the NSF gene.

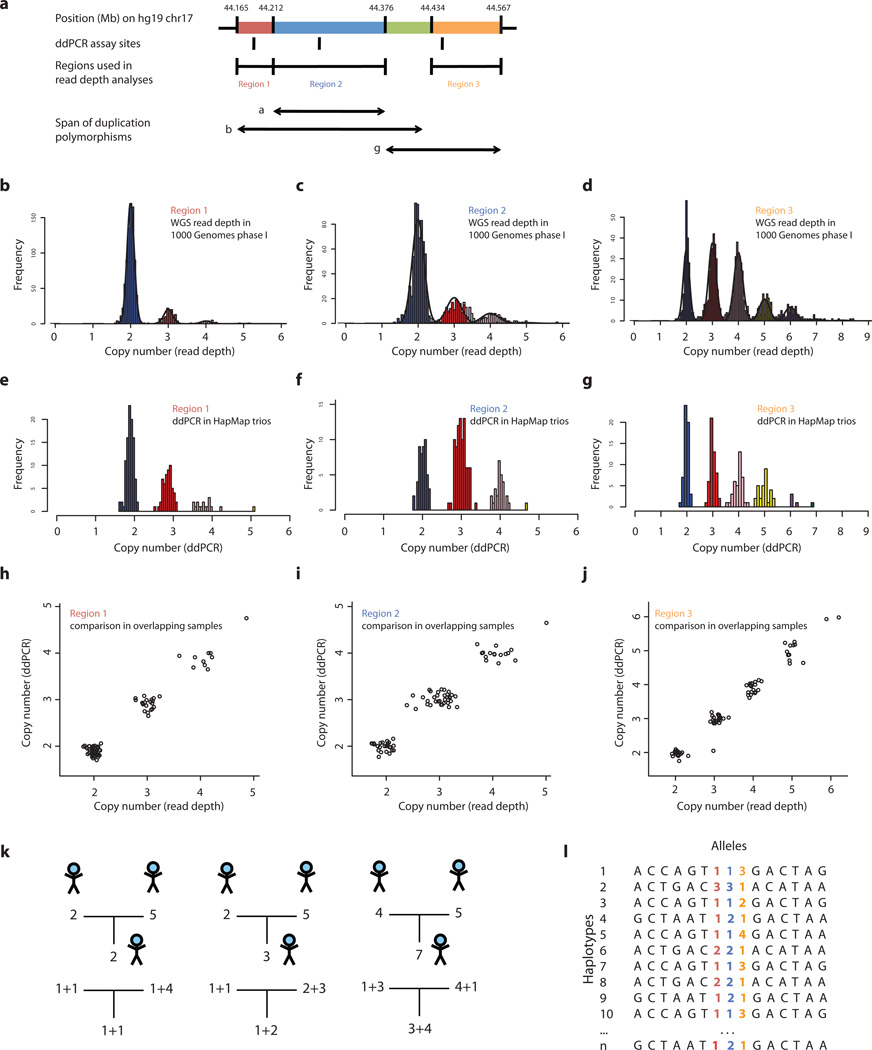

Figure 1.

Inference of complex CNV and SNP haplotypes at the 17q21.31 locus. Copy number of three copy-number-variable segments of 17q21.31 (a) was measured in populations using two approaches: analysis of read depth in whole-genome sequence (WGS) libraries available for 942 individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project phase 1, which we applied to measure copy number of region 1 (b), region 2 (c), and region 3 (d); and a droplet-based digital PCR (ddPCR) approach, which we applied to analyze father-mother-offspring trios from HapMap at specific sites within region 1 (e), region 2 (f), and region 3 (g). (Note that the frequencies of these copy-number classes are not identical in b–d and e–g, as their frequencies stratify by population and the samples surveyed overlap only partially.) These determinations of copy number were concordant for genomes analyzed by both methods in region 1 (h), region 2 (i), and region 3 (j). Analysis of the segregation of copy-number levels in trios allowed the contribution of transmitted and untransmitted chromosomes to diploid copy number to be determined in most trios (k). This in turn allowed CNV alleles to be phased with one another and with SNPs to create reference haplotypes (l).

We next sought to type each of these structural features in populations. To address longstanding challenges in measuring the integer copy number of multi-allelic duplication CNVs17, we deployed two new methods: (i) analysis of read depth by applying the Genome STRiP algorithm10 to whole-genome sequence (WGS) data from 946 unrelated individuals sampled in the 1000 Genomes Project14 (Fig. 1b–d, Methods); and (ii) a droplet-based approach to digital PCR (ddPCR)18, to analyze 120 father-mother-offspring trios from HapMap (Fig. 1e–g, Methods). These measurements of integer copy number, which varied from 2 to 8, were 99.1% concordant across 234 genotypes in overlapping samples, validating both methods (Fig. 1h–j). The integer copy numbers of these segments were then de-convolved into the contributions of the three overlapping duplication polymorphisms (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 2–3, Supplementary Tables 2–9). The state of the inversion polymorphism was inferred from more than 100 tagging SNPs.

We then sought to understand these complex patterns of variation in terms of structural haplotypes – which structural features segregate separately or together. By inferring the number of copies of each CNV segment that segregated on transmitted and untransmitted haplotypes in each trio, we determined the chromosomal phase of each of these segmental copy numbers – with respect to one another, with respect to the inversion polymorphism, and with respect to SNPs across the locus (Fig. 1k,l, Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 10, Methods). All four structural features (three duplications and the inversion) were highly polymorphic, but they segregated as only nine common haplotypes (Fig. 2). Applying a maximum-likelihood model to unphased copy number measurements we derived from 1000 Genomes sequence data (Fig. 1b–d), we inferred frequencies of these haplotypes in twelve populations (Supplementary Table 11).

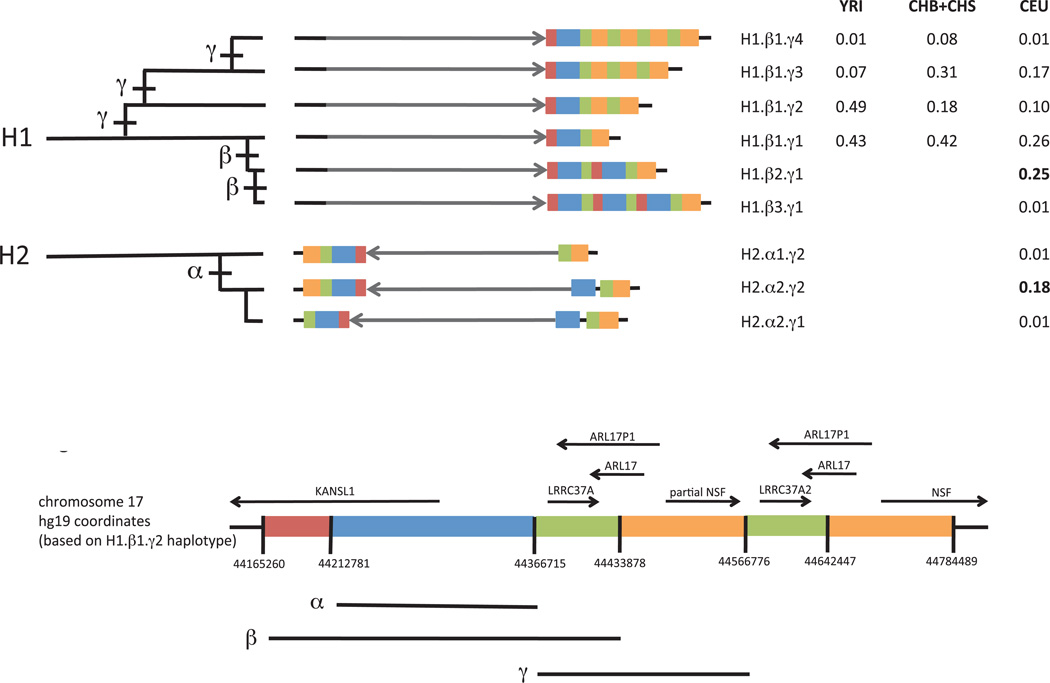

Figure 2.

Structural forms of the human 17q21.31 locus and their frequencies in populations. Each haplotype is represented in a simplified form to highlight major structural differences. The schematic at bottom indicates which genomic segment is represented by each color; detailed schematics with physical coordinates are available in Supplementary Material. The grey arrow indicates orientation of the unique inverted region within 17q21.31. Duplications of a 150-kb genomic segment (blue) containing the 5’ exons of the KANSL1 gene appear to have arisen on both the H1 and H2 forms of the 17q21.31 inversion polymorphism and reached high allele frequency in West Eurasian populations. The H1-polymorphic duplication β (red, blue, green) is longer than the H2-polymorphic duplication α (blue). A third duplication polymorphism γ (orange, green) affecting the NSF gene also varies in copy number. These structural polymorphisms segregate as the nine common haplotypes shown. The H2 inversion form shows structural diversity that was heretofore unappreciated, including a simpler, less common structural form (H2.α1) that may be the ancestral H2 structure. The table to the right lists allele frequencies for the nine structural haplotypes in different populations. CEU: Utah residents with Northern and West European ancestry. CHB: Han Chinese in Beijing. CHS: Han Chinese South. YRI: Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria. Genotype and allele frequencies in 12 populations are available as Supplementary Tables 2–9. Most of these haplotypes correspond one-to-one to haplotypes identified in the contemporaneous work by Steinberg et al.34: H1.β1.γ1 corresponds to H1.1; H1.β1.γ2 to H1.2 ; H1.β1.γ3 to H1.3; H1.β2.γ1 to H1D; H1.β3.γ1 to H1D.3; H2.α1.γ1 to H2.1; H2.α1.γ2 to H2.2; and H2.α2.γ2 to H2D.

The above analyses established the copy-number content of segregating haplotypes but did not establish the genomic locations of structural features. We inferred their locations from both sequence data (breakpoint-spanning reads) and linkage disequilibrium to SNPs. Both forms of evidence indicated that duplications β and γ are tandem duplications (Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, duplication α appears dispersed to a site 600 kb away from the original copy (Fig. 2, haplotype H2.α2), an observation that was reported earlier16 and that we confirmed by reconstructing a clone spanning an earlier gap in the H2 sequence (Supplementary Note).

Knowledge of the structural haplotypes led to a structural phylogeny (Fig. 2) and candidate structural history (Supplementary Note), yielding several insights about the 17q21.31 locus.

Although the H2 inversion form of 17q21.31 is reported to harbor little diversity1,9,10, we found that human populations also possess an older, structurally distinct H2 haplotype at low frequency. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that this rarer H2 structural form (H2.α1) is the ancestral H2 structure. First, H2.α1 resembles the H1 structure more closely than does the previously described H2 structure1,16 (H2.α2) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Note). Second, we identified H2.α1 haplotypes in Central African hunter-gatherer populations (including two Mbuti Pygmies and one Biaka Pygmy, among 13 and 21 individuals sampled from those populations by the Human Genome Diversity Panel16); such populations could have harbored H2.α1 over the long period (estimated at 2–3 million years1,16) during which H2 diverged from H1. The H2.α1 structure provides a potential missing link that would explain how the inversion could have occurred by a simple non-allelic homologous recombination (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Note).

The H2 inversion state is common in West Eurasians and rare in most other populations, which has been attributed to recent positive selection1. We found that other structural variations at 17q21.31 exhibit even greater population differentiation. Two distinct duplications (α and β in Fig. 1a and Fig. 2), each affecting the 5’ coding exons of the KANSL1 gene, have arisen independently on the H1 and H2 backgrounds. Both duplications have reached high allele frequency (19% and 26%) in West Eurasian populations, together comprising almost half of all European chromosomes; but we observed the α and β duplications only 1 and 0 times (respectively) among 502 East Asian chromosomes and 316 African chromosomes analyzed in Phase 1 of the 1000 Genomes Project (Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 4–9, 11), placing both among the human genome’s most population-differentiated polymorphisms (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 5). The α and β duplications have reached these highly differentiated allele frequencies in parallel at the same locus and in the same populations, a pattern similar to that observed at other loci (such as the LCT and APOL1 loci in African populations21,22) that have undergone recent selection.

We estimated two dates for each duplication - a coalescent age of haplotypes sampled today, and the age of the duplication events. The first can be estimated from the divergence of sequences flanking the duplications, the second by comparing the sequences of the duplication copies. To generate these data, we selectively captured and sequenced the 17q21.31 region in H1.β2 and H2.α2 homozygotes. We estimate the coalescence of the sampled beta-duplicated H1 chromosomes at 12 thousand years ago (kya). Divergence of otherwise unique sequences within the beta duplication suggests that the duplication itself occurred 20–27 kya. For the alpha-duplicated H2 chromosomes, we estimate an average coalescence of 17 kya, but the duplication itself appears much older (>1 Mya) than its rise to high frequency in West Eurasia. (See Supplementary Note S8 and Supplementary Table 12 for details of the dating and discussion of uncertainty surrounding the dates.)

The parallel increases in frequency of duplication α (on H2) and duplication β (on H1) in the same populations invite the hypothesis that they could influence a common phenotype. Both duplications involve the 5’ exons of KANSL1 (also called KIAA1267, MSL1v1, and CENP-36.). We found that both α and β give rise to novel KANSL1 transcripts (which we confirmed by rtPCR and sequencing) in which the 5’ exons of KANSL1 fuse to cryptic exons that terminate its coding sequence. The encoded proteins would retain the coiled coil domain of KANSL1 but would lack its PEHE domain (Supplementary Fig. 6). Interestingly, a similar truncation in the Drosophila ortholog of KANSL1, GC4699/E(nos), was identified in a mutagenesis screen for modifiers of Nanos and was found to enhance the effect of a Nanos hypomorph on age-dependent female fertility and germ line stem cell differentiation26. The precise role of KANSL1 in these processes is unknown, though it is found within a chromatin-modifying complex24,25.

It is important to understand how genome structures relate to variation in phenotypes. Complex genome structures are today not typed in sequencing or array-based genome wide association studies. Structurally complex regions are assumed to be poorly captured by LD to SNPs27,28. However, our analysis suggested that the structural diversity at 17q21.31 arose from a definable series of structural mutations (Fig. 2); each mutation likely arose on a specific haplotype and may continue to segregate on that haplotype. Such haplotypes might be made visible by combinations of many SNPs.

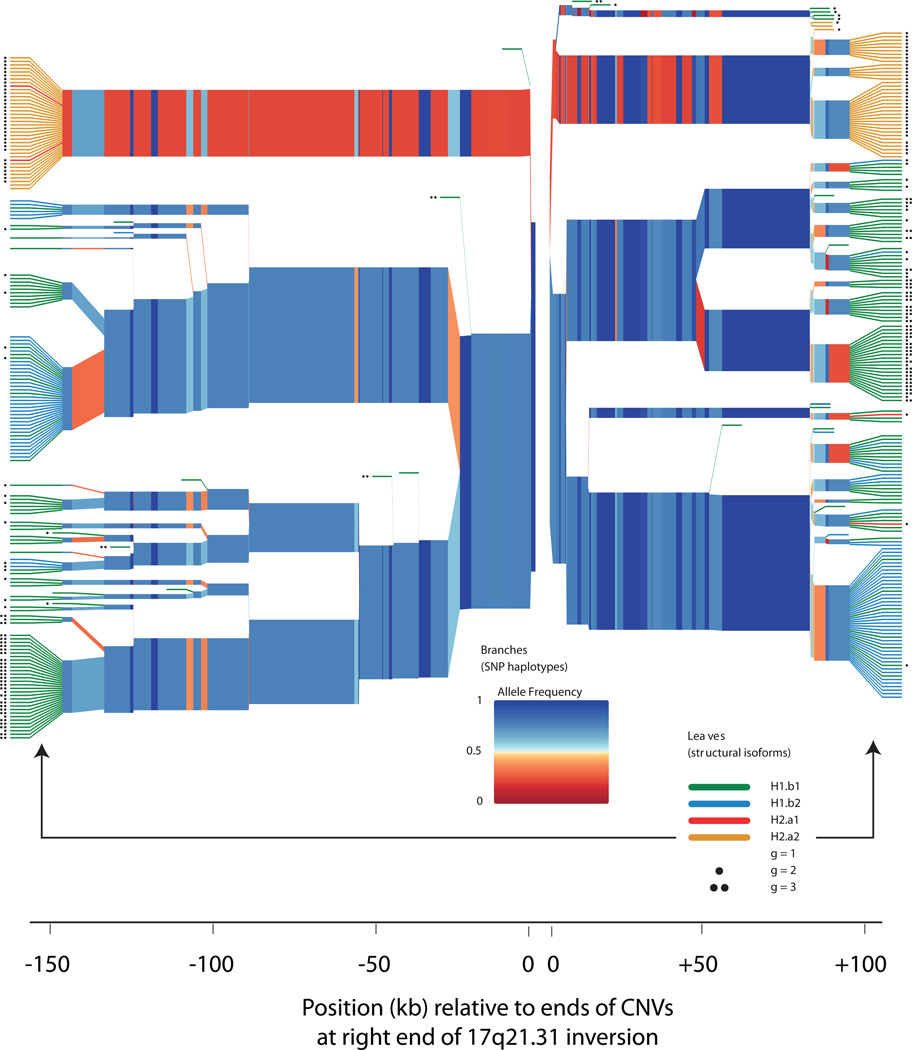

We therefore analyzed the SNP haplotypes on which each 17q21.31 structural form segregates in European populations (Fig. 3). The structural forms of 17q21.31 bore strong relationships to SNP haplotypes on both sides of the distal end of the 17q21.31 inversion, where the polymorphic CNV copies reside (Fig. 3). These results suggested it might be possible to capture 17q21.31 structural diversity through statistical imputation from SNPs30–32.

Figure 3.

Structural forms of 17q21.31 segregate on specific SNP haplotype backgrounds. The plot shows homozygosity and divergence (due to mutation and recombination) of the SNP haplotypes on which each structural form segregates in the European (CEU) trios analyzed in HapMap phase 3. The polymorphic CNV copies at the right end of the 17q21.31 inversion (Fig. 2) reside between the two origins of this plot (at center). SNPs on the left half of the plot therefore reside within the unique inverted region of 17q21.31, while SNPs on the right half of the plot are distal to the 17q21.31 inversion. On the branches, each colored segment represents the state of a SNP, with color representing allele frequency; branch points represent markers at which the depicted haplotypes diverge due to mutation and/or recombination with other haplotypes. The colored leaves and dots indicate the structural forms associated with each SNP haplotype. (Red leaves, H2.α1; orange leaves, H2.α2; green leaves, H1.β1; blue leaves, H1.β2; black dots, extra copies of the γ duplication.) In the plot, the structures are represented on the leaves in order to clarify their relationships to SNP haplotypes, but the variable parts of these CNVs actually reside (in genomic space) within the gap at center between the two origins on the plot. The structural forms segregate on characteristic SNP haplotypes, both inside and outside the inversion region. Statistical imputation of structural alleles utilizes SNPs on both sides of the CNVs together with more-distant markers not shown here.

We therefore constructed and evaluated the first imputation resource for a structurally complex locus. We created reference haplotypes from 94 CEU trio founders and a cosmopolitan cohort of 373 unrelated individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project phase 1 data, phasing structural variation along with 934 reference SNP haplotypes and removing any SNPs that fell within CNVs (Methods).

We evaluated imputation efficacy for each structural feature using leave-one-out tests. In each test, we selected a different test individual from the reference cohort and removed his structural-variation data from the reference genotypes. The test individual was always a CEU trio founder, for whom we had separately determined CNV states by ddPCR (Fig. 1e–g) and trio-based phasing (Fig. 1k,l). In each simulation, we used the rest of the reference genotypes as an unphased panel, together with the backbone SNP data from the test individual, to phase all the data and then impute (using Beagle33) the states of the structural alleles into the test individual. We then compared this prediction to the independently derived experimental data.

As a metric of imputation efficacy, we evaluated the statistical correlation (r2) of the experimentally determined structural state with the imputation-based, probabilistic dosage of each structural feature (Table 1, Supplementary Table 13). This metric estimates the efficacy of imputation; 1/r2 gives the proportional increase in sample size that would be required (in additive tests of association) to recover the statistical power obtained by explicitly typing each variant. For the four large structural features analyzed (the α, β, γ duplications and the inversion), imputation from low-coverage genome sequence data yielded structural determinations that correlated strongly (r2 = 0.99, 0.93, 0.84, 1.00) with the true diploid copy number (Table 1). This efficacy was only modestly lower using earlier panels of SNPs typed in GWAS (Table 1). Imputation was able to capture the multi-allelic CNVs substantially better than individual SNPs were (Table 1). These results suggest that imputing reference haplotypes into available SNP data will allow structural forms of 17q21.31, and perhaps many other such loci, to be evaluated for relationships to human phenotypes.

Table 1.

Imputation of 17q21.31 structural states from SNP data. Shown is the correlation (r2) of (a) experimental determinations of the state of each structural feature in each genome, with (b) either (i) imputed, probabilistic "dosages" of each structural feature or (ii) the state of the most-correlated single-SNP proxy (tagSNP) from each reference panel. r2 is a measure of imputation efficacy; 1/r2 gives the proportional increase in sample size that would be required (in additive tests of association) to recover the statistical power obtained by explicitly typing each variant. Imputation-based predictions were calculated across 330 leave-one-out simulations (Methods). Imputation requires a panel of reference haplotypes with accurate SNP genotypes and structural alleles; we provide such a resource for 17q21.31 in Supplementary Data.

| Structural feature imputed |

SNP panel used for imputation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 Genomes | HapMap3 | Illumina 1M | SNP 6.0 | |||||

| SNP genotypes from low-coverage GWS |

Array-based SNP genotypes |

Array-based SNP genotypes |

Array-based SNP genotypes |

|||||

| Imputatio n |

tagSNP | Imputation | tagSNP | Imputation | tagSNP | Imputation | tagSNP | |

| Copy number of α duplication | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| Copy number of β duplication | 0.93 | 0.49 | 0.79 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.77 | 0.30 |

| Copy number of γ duplication | 0.84 | 0.27 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.68 | 0.16 |

| Inversion state (H1 vs. H2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

We have described a population-genetic approach for characterizing structurally complex and diverse genome variations. Our approach is complementary to existing methods based on FISH and clone reconstruction. Drawing upon population-level sequence data sets, this approach will yield models of how structurally multi-allelic loci vary in populations. Our results motivate the creation of integrated SNP/structure haplotype maps that will allow complex genome structures to be imputed into many other genomes using available SNP data. Our results and methods offer new ways of analyzing complex genome structures and relating them to human disease.

Methods

Identification of CNV segments

We used a combination of array and sequence data to find the breakpoints of each CNV in the 17q21.31 region. Using array-based data, we identified the approximate span of CNV segments at kilobase resolution. We then refined the boundaries of these segments to 100 bp resolution by comparing read-depth profiles. Ultimately, the precise breakpoints of these rearrangements were identified by searching the 1000 Genomes data. Details of this analysis are provided in the Supplementary Note.

Analysis of CNVs using droplet-based digital PCR

To determine integer copy number of CNV segments (regions 1–3), we used a droplet-based digital PCR method18. We designed a pair of PCR primers and a dual-labeled fluorescence/FRET oligonucleotide probe to both the CNV locus and a two-copy control locus. Genomic DNA, and primers and probes for both assays were compartmentalized into droplets in an oil/aqueous emulsion (QuantaLife). We performed PCR amplification on the emulsion and then counted the number of droplets that were positive and negative for each fluorophore with a droplet reader (QuantaLife). Absolute copy number for the CNV locus was determined by comparing droplet counts of the CNV locus to the two-copy control locus. This method is described in greater detail in the Supplementary Note.

Analysis of CNVs using WGS read depth (Genome STRiP)

WGS read depth was also used to determine copy number in regions 1,2 and 3. We adapted the Genome STRiP genotyping method10 to analyze duplications in low coverage sequencing data from 1000 Genomes Phase 1. Details of this analysis are available in the Supplementary Note.

Inference of inversion state

The ancient, megabase-long inversion polymorphism at 17q21.311,16 has resulted in a large number of fixed differences between the two inversion states, because opposite alleles of the inversion cannot viably recombine with each other within the inverted region. These two inversion states therefore define two long haplotypes, H1 and H2, with hundreds of fixed differences between them. We refined these haplotypes using low-coverage data from Phase I of the 1000 Genomes Project, finding 1886 sites that are in perfect LD (=1) even in the large ascertainment (1,000 individuals) afforded by these data. Although the megabase inversion polymorphism has been reported to “toggle” on the longer timescales of primate evolution16, no study to date has reported any discordance in humans between the cytogenetic orientation of this megabase-long segment and the state of these inversion-proxy SNPs. We therefore used these long SNP haplotypes to diagnose inversion state (Supplementary Tables 2–3). We observed two individuals in 1000 Genomes for whom SNP genotypes in specific segments within the inverted region suggested an H1/H2 type that was discordant from that suggested by the rest of their SNPs at the locus. The clustering of these discordant SNPs suggested that these individuals’ genomes reflect gene-conversion or double-recombination events that occurred within the inverted regions; these individuals were not included in subsequent analyses.

Determination of haplotypic contributions to diploid copy number, and heuristic phasing in trios

Inferring haplotypic contributions to diploid copy number (Fig. 1j) was addressed with a joint maximum-likelihood analysis of genotypes, allele frequencies, and inheritance patterns in trios. Each population was analyzed separately. We considered all possible combinations of integer copy number (on each of the four haplotypes in a trio – paternal transmitted, paternal untransmitted, maternal transmitted, maternal untransmitted) that were consistent with the diploid copy-number measurements from all three trio members from ddPCR. See the Supplementary note for details of this analysis and a description of the expectation-maximization algorithm.

Inference of frequency of copy-number alleles in populations

For regions 1, 2, and 3, diploid copy number was first measured using read depth from whole genome sequencing by the Genome STRiP algorithm10 in low coverage WGS data from populations of unrelated individuals from 1000 Genomes. Allele frequencies were determined from genotype frequencies with an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm similar to that described in S4 of the Supplementary Note, but without the additional constraints provided by inheritance in trios (Supplementary Tables 2–4).

Statistical phasing of structural and fine-scale variation in populations

We determined phased structural genotypes for 47 CEU trios based on our model of the nine structural haplotypes, the ddPCR diploid copy number estimates for regions 1, 2 and 3, the assayed H1/H2 inversion state in each sample, and by assuming Mendelian inheritance in the trios. Phased haplotypes for the founders in these trios are listed in Supplementary Table 10. In a similar manner, we determined phased structural genotypes for 373 additional unrelated samples (where genotype could be determined without the benefit of trio inheritance constraints) from 1000 Genomes, using diploid copy number estimates from read depth genotyping in the 1000 Genomes Phase 1 low coverage sequence data and determining H1/H2 inversion state based on a tag SNP rs17660065. We used this set of resolved structural haplotypes for 467 individuals (the 373 individuals from 1000 Genomes plus the 94 trio founders) to evaluate imputation of the structural haplotypes from the genotypes of nearby SNPs using Beagle29. We evaluated imputation accuracy through a series of “leave one out” trials in which we withheld information on one individual from the reference panel and then imputed the structural haplotypes for that individual based on their genotypes at surrounding SNPs. Details of allelic encoding, evaluation methodology, and estimation of CNV dosages are available in the Supplementary Note.

Identification of KANSL1 fusion gene RNA transcripts

We designed primers to amplify the KANSL1 fusion gene transcript created by the duplication using information from genomic breakpoints and publicly available RNA sequence data23. The primer design to amplify the KANSL1 fusion gene transcript created by the duplication was informed by genomic breakpoints and mRNA clone BC006271, which is likely a complete fusion transcript resulting from the duplication. These analyses are discussed in detail in the Supplementary Note.

Dating the coalescence of duplication-containing chromosomes

We performed targeted capture and sequencing of the 17q21.31 region for 3 individuals homozygous for duplication and 4 individuals homozygous for duplication. Excluding haplotypes that showed evidence of recombination with other structural forms, we computed the average pairwise diversity among chromosomes with the duplication and separately among chromosomes with the duplication. To estimate a coalescence date, the amount of diversity surrounding each duplication was calibrated with human-chimp divergence over the same region. Human-chimpanzee speciation was assumed to be 6 Mya. Details of the coalescence analysis and direct duplication dating are available in the Supplementary Note.

Analysis of allele frequency differentiation between European and non-European populations

To evaluate the stratification of each duplication, we calculated the fraction of SNPs (from 1000 Genomes phase 1) having similarly high derived allele frequency in the European populations sampled (379 samples from the CEU, FIN, GBR, IBS and TSI population groups) that had similarly low derived allele frequency across the non-European populations sampled (471 samples from the CHB, CHS, JPT, LWK and YRI population groups). Details of this analysis as well as analysis of allele frequency differentiation within Europe are provided in the Supplementary Note.

Analysis of tag SNPs

To compare the efficacy of imputation to using a single best tag SNP, we computed the correlation (r2) between the diploid copy number of each CNV (alpha, beta, gamma and the H1/H2 state encoded as 0,1,2) and the dosage of each SNP in each reference panel, encoded as 0,1,2. For the Illumina 1M and Affymetrix 6.0 comparisons, we considered only the subset of SNPs from the HapMap3 panel present on each array. We report the highest r2 across all SNPs in the panel.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Smith Family Award for Excellence in Biomedical Research to SM, by the National Human Genome Research Institute (U01HG005208-01S1), and by startup resources from the Harvard Medical School Department of Genetics. Joshua Korn provided an early version of software for visualizing haplotype diversity. Nadin Rohland and Tom Mullen contributed expertise on laboratory experiments. We thank Nick Patterson, David Reich, David Altshuler, Eric Lander, Brian Browning, Joshua Korn, Jesse Gray, Chris Patil, Giulio Genovese, Aswin Sekar, and Sharon Grossman for helpful conversations and/or comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

Sequence data is available at the Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRA052055.1.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SM, LB, and RH conceived the strategy for population-genetic dissection of structurally complex loci. LB performed all laboratory experiments and multiple computational analyses including the estimation of haplotype frequencies, delineation of CNV regions and alignment of next generation sequence data. RH performed computational analyses of the 1000 Genomes data, including finding breakpoint spanning reads for CNVs, and integrated analyses of SNP/CNV haplotypes. MZ performed analyses of sequence data to determine large-scale structures, to estimate coalescence and mutation dates, and to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the locus. RH and LB developed the imputation strategy. SM, LB, RH, and MZ wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Stefansson H, et al. A common inversion under selection in Europeans. Nat Genet. 2005;37:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowdhury R, Bois PR, Feingold E, Sherman SL, Cheung VG. Genetic analysis of variation in human meiotic recombination. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fledel-Alon A, et al. Variation in human recombination rates and its genetic determinants. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skipper L, et al. Linkage disequilibrium and association of MAPT H1 in Parkinson disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:669–677. doi: 10.1086/424492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon-Sanchez J, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarroll SA, et al. Integrated detection and population-genetic analysis of SNPs and copy number variation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ng.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad DF, et al. Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature. 2009;464:704–712. doi: 10.1038/nature08516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarroll SA, et al. Deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM associated with altered IRGM expression and Crohn's disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1107–1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willer CJ, et al. Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat Genet. 2009;41:25–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handsaker RE, Korn JM, Nemesh J, McCarroll SA. Discovery and genotyping of genome structural polymorphism by sequencing on a population scale. Nat Genet. 2011;43:269–276. doi: 10.1038/ng.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. Characterizing complex structural variation in germline and somatic genomes. Trends Genet. 2012;28:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International_HapMap_Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International_HapMap3_Consortium. An integrated haplotype map of rare and common genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills RE, et al. Mapping copy number variation by population-scale genome sequencing. Nature. 2011;470:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature09708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zody MC, et al. Evolutionary toggling of the MAPT 17q21.31 inversion region. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1076–1083. doi: 10.1038/ng.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarroll SA. Copy-number analysis goes more than skin deep. Nat Genet. 2008;40:5–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hindson BJ, et al. High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8604–8610. doi: 10.1021/ac202028g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hindson BJ. A high-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Analytical Chemistry. 2011 forthcoming; doi: 10.1021/ac202028g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang F, et al. The DNA replication FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism can generate genomic, genic and exonic complex rearrangements in humans. Nat Genet. 2009;41:849–853. doi: 10.1038/ng.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tishkoff SA, et al. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat Genet. 2007;39:31–40. doi: 10.1038/ng1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genovese G, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery SB, et al. Transcriptome genetics using second generation sequencing in a Caucasian population. Nature. 2010;464:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nature08903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith ER, et al. A human protein complex homologous to the Drosophila MSL complex is responsible for the majority of histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9175–9188. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9175-9188.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Wu L, Corsa CA, Kunkel S, Dou Y. Two mammalian MOF complexes regulate transcription activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2009;36:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu L, Song Y, Wharton RP. E(nos)/CG4699 required for nanos function in the female germ line of Drosophila. Genesis. 2010;48:161–170. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharp AJ, et al. Segmental duplications and copy-number variation in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:78–88. doi: 10.1086/431652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redon R, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444:444–454. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernando MM, et al. Assessment of complement C4 gene copy number using the paralog ratio test. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:866–874. doi: 10.1002/humu.21259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Browning SR. Missing data imputation and haplotype phase inference for genome-wide association studies. Hum Genet. 2008;124:439–450. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Willer C, Sanna S, Abecasis G. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:387–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nrg2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Browning BL, Browning SR. A unified approach to genotype imputation and haplotype-phase inference for large data sets of trios and unrelated individuals. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberg K, Antonacci F, et al. Structural diversity and African origin of the 17q21.31 inversion polymorphism. Nat Genet. doi: 10.1038/ng.2335. (This Issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.