Abstract

Critics of giving citizens under 18 the right to vote argue that such teenagers lack the ability and motivation to participate effectively in elections. If this argument is true, lowering the voting age would have negative consequences for the quality of democracy. We test the argument using survey data from Austria, the only European country with a voting age of 16 in nation-wide elections. While the turnout levels of young people under 18 are relatively low, their failure to vote cannot be explained by a lower ability or motivation to participate. In addition, the quality of these citizens' choices is similar to that of older voters, so they do cast votes in ways that enable their interests to be represented equally well. These results are encouraging for supporters of a lower voting age.

Keywords: Input legitimacy, Political participation, Teenage vote, Turnout, Voting age

Highlights

► Citizens under 18 may lack the motivation and ability to participate in elections. ► We examine the political motivation and ability and their impact on turnout and vote choice quality for citizens under 18. ► We use a survey from Austria, the only country with a voting age of 16. ► Their reasons for not voting are not based on a lack of political motivation and political ability. ► Their quality of vote choice is no lower than among older voter cohorts.

1. Introduction3

The level of turnout at elections is often seen as an indicator of the health of a democracy (Fieldhouse et al., 2007), yet there is a general trend towards declining rates of electoral participation in Western Europe (e.g. Aarts and Wessels, 2005; Blais and Rubenson, 2007; Franklin et al., 2004). This has led to fears that democratic legitimacy may decline as elections increasingly fail to act as the ‘institutional connection’ (Topf, 1995a) between citizens and the state.

In light of these developments, it has been suggested that the minimum voting age should be lowered to 16 (e.g. Power Commission, 2006; Votes at 16, 2008; Hart and Artkins, 2011). Supporters of such a reform argue that lowering the voting age would have a positive impact on electoral participation. This is because young people under 18 are likely to still be in school and live with their families, two factors that have been shown to encourage turnout through a variety of socialisation mechanisms (Franklin, 2004; Highton and Wolfinger, 2001; Bhatti and Hansen, 2010). In the long term, this higher level of participation at a young age may then facilitate the early development of a habit of voting (e.g. Plutzer, 2002; Franklin, 2004). Of course, lowering the voting age is not only justified as a way to stop the decline in turnout. For example, it is also seen as a way to ensure that the interests of young citizens are represented in the political system (Votes at 16, 2008).4

However, the proposed reform is not without its critics. The main argument made against lowering the voting age is that young people under 18 lack the ability and motivation to participate effectively in the electoral process (Chan and Clayton, 2006). It is suggested that this will lead to low turnout rates, comparable to – if not even lower than – those observed among citizens aged 18–25 (Electoral Commission, 2004). A further consequence would be that citizens under 18 might not make use of their vote as effectively as older voters. While they might vote for the sake of voting, they would not challenge the government to respond to their interests. Thus, their vote choice would be driven more strongly by expressive instead of instrumental considerations (Tóka, 2009), and their policy views would not be well-represented by political actors.

In this paper, we test whether these critics are right. Are young people under 18 less able and motivated to participate effectively in politics? And do these factors influence whether and how they use their right to vote? If the answer to these questions is yes, then lowering the voting age could indeed have negative consequences for the health of democracy. If the answer is no, then critics are arguably left with fewer arguments why we should oppose lowering the voting age. Instead, we might consider potential positive consequences of the reform, such as tying young people to the democratic process, encouraging the development of a habit of voting and ensuring the representation of their interests.

We examine the choices made by young people under 18 using data from Austria, where in 2007 the voting age at national elections was lowered to 16. Specifically, we use a survey carried out in the run-up to the European Parliament (EP) elections 2009 which over-sampled young people under 26. Austria's reform allows us to examine for the first time whether the critics of lowering the minimum voting age are right. Before, the only possible empirical strategies were either to extrapolate about the behaviour of citizens under 18 from that of voters just over 18 or to study the potential electoral behaviour of young people under 18 in a context where they did not have the vote.

Our survey indicates that the intention to turn out was indeed relatively low among citizens under 18 in the 2009 EP election. Using the self-assessed likelihood of voting on a scale of 0–10, under-18s have a low average intention of turning out, with a mean score of 5.91. This is lower than among respondents aged between 18 and 21 (6.24) and between those aged between 22 and 25 (6.98), while respondents over 30 have a mean score of 7.38.

Is this pattern due to the fact that Austrians under 18 are particularly unable or unwilling to participate in politics? Our findings show that this is not the case. First, measures of political interest, knowledge and non-electoral participation indicate that young people under 18 are not particularly unable or unwilling to participate in political life. Second, these factors do not help to explain their lower turnout rates, so we cannot say that young citizens fail to vote for reasons that are particularly troubling for democratic legitimacy. Finally, there is no evidence that the quality of vote choices among citizens under 18 is any worse than that of older voters.

We begin this paper by discussing in greater depth existing arguments regarding the political behaviour of citizens under 18 and the potential effects of lowering the voting age in terms of democratic legitimacy, focussing on turnout and the quality of vote choice. After describing the survey, we provide a brief descriptive account of young people's motivation and ability to engage in politics. We then turn to a multivariate analysis that explores the reasons behind turnout decisions of citizens under 18. Finally, we examine the quality of vote choice among these voters.

2. Citizens under 18 and the democratic process

In the scholarly debate democratic legitimacy includes two dimensions: input and output legitimacy (Scharpf, 1999). This paper focuses on the input dimension of democratic legitimacy. Input legitimacy refers to the idea that “[p]olitical choices are legitimate if they reflect the ‘will of the people’ – that is, if they can be derived from the authentic preferences of the members of a community” (Scharpf, 1999: 6). Input legitimacy requires citizens who are motivated and competent and who engage in reasoned arguments in collective decision-making processes. As a result, input legitimacy may be negatively affected by lowering the voting age if this only serves to extend suffrage to citizens who are not motivated or able to participate in decision-making in this way. Simply put, the central question is whether citizens under 18 have the ability and motivation to participate effectively in elections.

Why might we expect this not to be the case? Chan and Clayton (2006) argue that young people under 18 are simply not politically ‘mature’ enough to take part in the electoral process, and they define this ‘maturity’ precisely as the ability and motivation to participate. They measure the ‘political maturity’ of young people under 18 using political interest, party identification, political knowledge and attitudinal consistency. According to Chan and Clayton (2006), those under 18 fail to score high enough on any of these indicators. They suggest that these differences cannot be explained by the fact that in the UK those under 18 do not yet have the vote and therefore have no incentive to become involved in politics. Instead, citing Dawkins and Cornwell (2003), they argue that the teenage brain may simply not be ready to vote at 16. However, Hart and Artkins (2011) point out that so far no neurological evidence has been put forward to prove this point, while Steinberg et al. (2009) show that teenage citizens possess the same cognitive sophistication as young adults. It is perhaps more likely that these age differences may exist due to a universal life-cycle effect, with younger voters simply not yet having developed the political interest, knowledge and sense of duty that comes with age (Aarts and Wessels, 2005).

Thus, from this critical perspective young citizens under 18 lack the ability and motivation to engage effectively in politics. Since our aim is to test the arguments made by critics of lowering the voting age, our hypotheses are as follows:

-

H1a:

Young citizens under 18 are less able to participate in politics effectively than older voters.

-

H1b:

Young citizens under 18 are less motivated to participate in politics effectively than older voters.

2.1. Citizens under 18 and turnout

Enlarging suffrage to include young people under 18 may have consequences for the level of turnout. On the one hand, some scholars argue that turnout numbers may improve, especially in the longer term, as young people under 18 are more easily and more lastingly mobilised to vote due to socialisation effects (e.g. Franklin, 2004). On the other hand, critics put forward the argument that it could also be that young people under 18 simply mirror the low levels of turnout found among those aged between 18 and 21 (e.g. Electoral Commission, 2004).

However in this paper, we are not concerned with the levels of turnout themselves. For one, to examine the development of a habit of voting requires a longer-term perspective than cannot be achieved just two years after the voting age was lowered. Moreover, looking exclusively at the level of turnout should not be the only way to address whether declining electoral participation is worrying. As pointed out, it is particularly concerning when decisions not to vote are a reflection of disenchantment, indifference or a lack of capabilities (Chan and Clayton, 2006).5

Lower levels of turnout among citizens under 18 do not automatically indicate that this pattern is due to a lower ability and motivation to participate. Other reasons may underlie this decision. First, young voters may privilege new modes of political participation over traditional forms of electoral participation (Topf, 1995b), ‘bypassing the electoral routes’ (Franklin, 2002: 165). Electoral participation is not the only way that a democratic bond between citizens and the political system can be created (e.g. Topf, 1995b; Franklin, 2002; Fuchs and Klingemann, 1995; Dalton, 2009). Young voters may be particularly likely to choose other forms of participation due to longer schooling years, exposure to other forms of informal civic education, higher information levels, new information channels and a decrease in party affiliation (e.g. Thomassen, 2005). Second, young voters may simply see voting itself as less of a civic duty (e.g. Blais, 2000; Dalton, 2009; Wattenberg, 2008). They may have a more individual calculus of the utility of voting and rely more heavily on the assessment of the importance of election outcomes (Thomassen, 2005).6 Thus, analysing only turnout rates per se is not enough to provide a good picture of the status of input legitimacy as we also need to take the underlying motives into account. In other words, we need to know whether citizens under 18 fail to vote because of a lower ability and motivation to participate effectively. If this is the case, then this undermines input legitimacy; if not, then lower turnout is perhaps less worrying.7

In sum, we argue that the quality of the electoral participation of citizens under 18 is particularly unsatisfactory if low turnout can be explained by a low willingness and motivation to engage in politics. We will therefore test the following two hypotheses:

-

H2a:

The lower turnout of young people under 18 can be explained by their lower ability to participate in politics.

-

H2b:

The lower turnout of young people under 18 can be explained by their lower motivation to participate in politics.

2.2. Citizens under 18 and the quality of vote choice

Just because citizens go to the polls does not mean that they will be well-represented by those they elect. As Lau et al. argue: “[V]otes freely given are meaningless unless they accurately reflect a citizen's true preferences” (2008: 396). Citizens should be able to select accurately between political actors and make a choice that is consistent with their own views, attitudes and preferences (e.g. Lau and Redlawsk, 1997). If voters under 18 take choices that do not reflect their interests and attitudes, then this will limit their substantial representation (Pitkin, 1967). The arguments presented earlier that citizens under 18 may lack the requisite ability and motivation to participate (Chan and Clayton, 2006) would also lead them to be less inclined to think carefully about their decision and therefore choose parties that do not reflect their preferences. They may fail to take choices that represent their interests well. Thus, there would also be negative consequences for democracy if the choices made by voters under 18 are less well-linked to their actual preferences than those of older voters. On the other hand, if the decisions of voters under 18 reflect their preferences as well as they do in older age groups, then the critics' arguments have no empirical basis. We would have no reason to believe that the interests and preferences of voters under 18 would be less well-represented.

Our final hypothesis therefore tests this last argument by critics of lowering the voting age and reads as follows:

-

H3:

The quality of vote choice among voters under 18 is lower than among older voters.

3. Data and methods

Until now, empirical research on the effects of lowering the voting age has had to take one of two unsatisfactory approaches. The first method has been to assume that under-18s are little different from those just over 18, justifying the use of evidence from the voting behaviour of young citizens aged 18 and older (e.g. Electoral Commission, 2004).8 The second approach uses data on citizens under 18 before they have the right to vote (e.g. Chan and Clayton, 2006). Studying electoral participation for those who do not have the right to vote has a considerable flaw: without the right to cast a ballot, there is no rational incentive for citizens to increase their interest and knowledge in politics. Simply having voting rights may encourage people to gather information and become politically active in other ways (Rubenson et al., 2004; Hart and Artkins, 2011). To test correctly whether the electoral participation of under-18s matches the quality of that of their older peers, we therefore need a case where such young citizens have the right to vote.

Austria is the only country in Europe that has a voting age of 16 for national elections.9 The reform was passed by the Austrian parliament in 2007, and since then, young people under 18 have cast ballots at a series of elections, including for the national parliament in 2008, the European Parliament in 2009 and the presidential elections in 2010. Austria thus provides the first opportunity to examine the political participation of under-18s in a nation-wide election, at least in a stable advanced industrial democracy. The specific data used in this paper are from a pre-election survey (n = 805) conducted at the end of May and the beginning of June 2009, so in the weeks directly before the European Parliament election (Kritzinger and Heinrich, 2009).10 Voters between 16 and 25 were over-sampled for this survey (n = 263), making this dataset particularly suitable to our research questions. We take advantage of the over-sampled segment of Austrian voters to compare 16- and 17-year olds to voters between 18 and 21, 22 and 25, 26 and 30 and to voters over 31.11

We assess the ability and motivation to participate effectively in politics using three measures.12 The ability to engage in politics is evaluated using political knowledge, which we measure by assessing whether respondents correctly place the Social Democrats (SPÖ) to the left of the two far-right parties (FPÖ and BZÖ) and the People's Party (ÖVP). We measure the motivation to participate effectively in politics using political interest and the willingness to consider various forms of non-electoral participation. The respondents' interest in politics is measured as the average of answers to eight questions tapping attention to politics in general and the EP campaign in particular. The variable was rescaled to range from 0 to 1, and the alpha reliability coefficient of this scale is 0.81. We measured non-electoral political participation by asking respondents to rate on a four-point scale their hypothetical willingness to engage in a series of political activities: contacting a politician, collecting signatures, working for a non-governmental organization, taking part in a legal demonstration and working on a campaign. We also create an overall index for non-electoral political participation using the average answer to the five questions. The scale ranges from 0 to 1 with an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.75.

It is always difficult to measure turnout using survey questions due to the problems of over-reporting, sample selectivity, social desirability bias and the stimulus effects of pre-elections interviews (e.g. Aarts and Wessels, 2005; Bernstein et al., 2001; Karp and Brockington, 2005).13 There is evidence that the pre-election turnout intention questions are the best available predictor of whether a person is likely to vote (Bolstein, 1991). Respondents might be more honest regarding their actual intention to turn out when presented with a scale in which people can indicate uncertainty and reluctance without declaring directly that they might abstain. Therefore, we use turnout intention as our dependent variable. We measure propensity to turn out with a question asking respondents to state their certainty of voting in the upcoming EP election on a scale of 0–10. In our sample, 54.1% of respondents gave a vote intention score of 8 or higher and 41% a score of 9 or higher.14 This compares favourably to the 46% who actually voted on 7 June 2009.15

Examining the intention to turn out in an EP election gives us also the advantage of studying an election with lower overall turnout; this could reduce the social desirability bias as people might be less reluctant to declare that they will not vote when abstention is a more common phenomenon. We take into account the specific EU nature of the election by including EU-specific versions of core variables in our regression models and by including a control variable concerning views on European integration.

4. Results

We present our results in three steps. First, we present descriptive findings on the ability and motivation to participate in politics among young people under 18. Next, we examine the causes underlying turnout decisions before finally examining the quality of vote choice.

4.1. The ability and motivation to participate effectively

Critics of lowering the voting age argue that citizens under 18 have a lower motivation and ability to engage in politics than older citizens. We test this by considering three measures widely used in the literature to capture these constructs (e.g. Fieldhouse et al., 2007): interest, knowledge and non-electoral political participation.

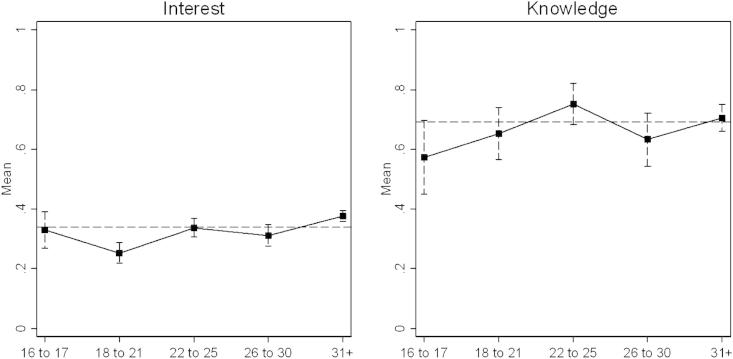

Fig. 1 presents the age group means for political interest and knowledge. We see, first, that interest in politics is by no means particularly low among under-18s; indeed, it is the second-highest average of the four age groups under 30. However, in spite of their apparent interest in politics, political knowledge is somewhat lower among under-18s compared to the other three groups of young voters. However, it is worth noting that this difference is significant in a two-tailed t-test only for the comparison with 22- to 25-year-olds. Moreover, a cautious interpretation of these results is required since we only have one knowledge question. Nevertheless, there is some indication that political knowledge might be lower among under-18s. This may be due to the fact that young citizens do not yet have the experience necessary to place parties correctly on a left–right scale. There is thus some support for H1a, i.e. that citizens under 18 are less able to participate in politics.

Fig. 1.

Interest and knowledge, age group differences. Note: mean values by age group shown; bars indicate 95% confidence intervals around the mean; dashed line indicates overall mean; see Appendix for question details.

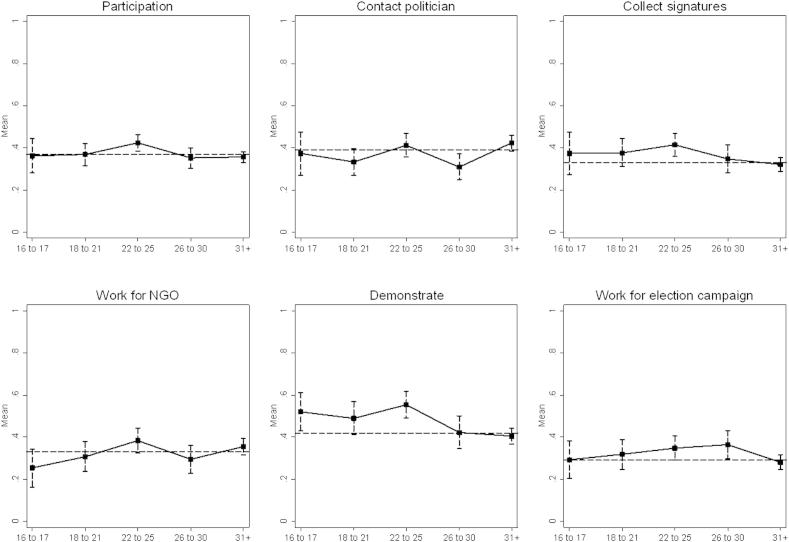

Citizens can also engage in politics outside of elections. In Fig. 2, we present the average scores for each age group across all five activities we asked about, with the top-left panel presenting the results for the overall index. It is clear that the youngest citizens' willingness to participate in non-electoral politics is relatively high and no different from the overall mean. Young citizens are particularly likely to say that they would take part in a demonstration. Overall, citizens under 18 are just as motivated to take part in political life as older age groups. This preliminary result indicates that there is little evidence in favour of H1b.

Fig. 2.

Non-electoral political participation, age group differences. Note: mean values by age group shown; bars indicate 95% confidence intervals around the mean; dashed line indicates overall mean; see Appendix for question details.

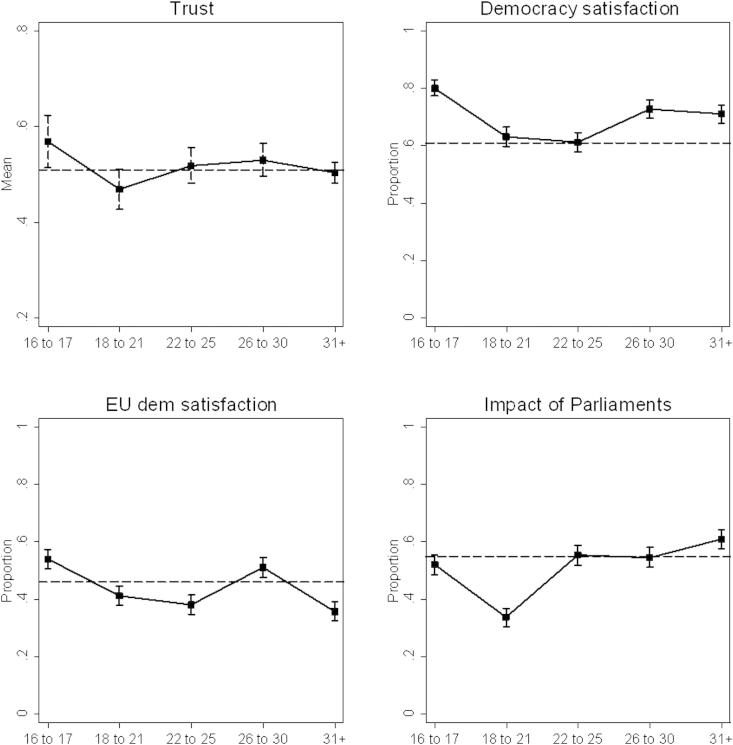

Finally, we further illustrate the attitudes of young people under 18 using measures of democratic disaffection and alienation, specifically the three indicators institutional trust, satisfaction with democracy and the perceived impact of politics on one's life (Fig. 3).16 These are related to measures of the motivation to engage effectively in politics. Surprisingly, our data show that trust in institutions among citizens under 18 is significantly higher than the overall mean among all citizens, so there is no indication at all of disaffection using this classical measure. In addition, satisfaction with national and European democracy among citizens under 18 is actually higher (and often significantly so) than among older citizens. Turning to the bottom-right panel, younger citizens do not differ from older citizens in the proportion who say that either the national parliament or the EP has a ‘strong’ impact on them personally. Given this evidence and their satisfactory level of political interest, there is strong descriptive evidence that the youngest citizens in Austria are not particular ‘turned off’ by electoral politics, democracy and political institutions in general – results which are quite contrary to those reported in the literature (e.g. Chan and Clayton, 2006). There is therefore so far little evidence in favour of H1b, so that there is little indication that citizens under 18 are less motivated to participate effectively in politics.

Fig. 3.

Alienation, indifference and impact of parliaments, age group differences. Note: mean values by age group shown; bars indicate 95% confidence intervals around the mean; dashed line indicates overall mean; see Appendix for question details.

In sum, citizens under 18 do not differ in terms of their democratic disaffection and their motivation to participate in politics from older age groups. However, they do have relatively little knowledge, indicating that they might be less able to participate. In the next section, we will examine whether age group differences in the motivation and ability to participate effectively in politics can help explain lower turnout levels among citizens under 18.

4.2. Turnout motivations of citizens under 18

We now turn to examining the causes of lower turnout by following the approach of Rubenson et al. (2004) and Gidengil et al. (2005). The starting point is a very basic regression model with dummy variables for the four age groups under 31 as well as a series of fundamental socio-demographic controls. In the following steps, a series of independent variables are added to the model. This allows us to test whether different age groups decide not to vote because they lack the ability or motivation to participate effectively in politics; if this is the case for the youngest cohort, the age coefficient for the under-18s should decrease (or even cease to be significant) when the relevant variables are added to the model. Importantly, the cases included in each model are the same, so the most basic model only includes respondents for which all variables in the fullest model are available. Due to a heteroscedastic error distribution robust standard errors are used.

We present six OLS regression models predicting voter turnout (Table 1). Model 1 includes four age dummy variables for those aged 16 and 17, 18–21, 22–25 and 26–30. The reference group are citizens aged 31 and older. The model also includes four socio-demographic controls: education, gender, rural residence and migration background. Previous research indicates that education is an important predictor of the propensity to turn out in almost all democracies (e.g. Wolfinger and Rosenstone, 1980; Blais et al., 2004; Rubenson et al., 2004; Aarts and Wessels, 2005). We also include migration background as this may be related to the level of resources and to the level of connectedness one feels to the political system; we therefore expect having a migration background to have a negative effect on turnout (Fieldhouse et al., 2007). Living in a rural area may increase turnout as social capital and thus the pressure to vote may be higher there (e.g. Putnam, 2000; Nevitte et al., 2009).

Table 1.

OLS regression results.

| Variables | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic model | Basic model + controls | Knowledge | Participation | Interest | Full model | |

| Age (ref: 31+) | ||||||

| 16–17 | −1.005 (0.517) | −1.244** (0.458) | −1.210** (0.467) | −1.272** (0.438) | −1.09* (0.424) | −1.100** (0.419) |

| 18–21 | −1.562*** (0.361) | −1.138** (0.375) | −1.163** (0.366) | −1.201*** (0.353) | −0.429 (0.347) | −0.600 (0.332) |

| 22–25 | −0.690* (0.329) | −0.708* (0.306) | −0.771* (0.306) | −0.936** (0.302) | −0.295 (0.294) | −0.576* (0.293) |

| 26–30 | −1.040** (0.354) | −1.118*** (0.330) | −1.109*** (0.328) | −1.040*** (0.306) | −0.547 (0.293) | −0.565* (0.284) |

| Political knowledge | 0.703* (0.277) | 0.672** (0.253) | ||||

| Non-electoral participation | 3.396*** (0.499) | 2.423*** (0.511) | ||||

| Political interest | 6.815*** (0.689) | 5.841*** (0.709) | ||||

| Education | 1.332*** (0.250) | 1.013*** (0.251) | 1.012*** (0.249) | 0.659* (0.258) | 0.749** (0.242) | 0.533* (0.245) |

| Female | 0.075 (0.228) | 0.063 (0.216) | 0.089 (0.216) | 0.007 (0.208) | 0.154 (0.202) | 0.126 (0.197) |

| Rural residence | 0.156 (0.229) | 0.195 (0.222) | 0.179 (0.221) | 0.233 (0.213) | 0.254 (0.208) | 0.257 (0.202) |

| Migration background | −0.392 (0.306) | −0.513 (0.289) | −0.521 (0.293) | −0.431 (0.285) | −0.432 (0.270) | −0.393 (0.275) |

| EU attitude | −0.0002 (0.474) | 0.063 (0.474) | −0.496 (0.461) | −0.135 (0.429) | −0.409 (0.427) | |

| Trust in institutions | 3.043*** (0.773) | 2.964*** (0.776) | 2.718*** (0.755) | 1.559* (0.748) | 1.464* (0.738) | |

| Dem. satisfaction: National | 0.135 (0.281) | 0.126 (0.282) | 0.255 (0.276) | 0.103 (0.264) | 0.184 (0.263) | |

| Dem. satisfaction: EU | 0.311 (0.259) | 0.302 (0.260) | 0.224 (0.258) | 0.479 (0.247) | 0.385 (0.246) | |

| Impact of national parliament | 1.246*** (0.265) | 1.163*** (0.263) | 1.011*** (0.254) | 0.380 (0.253) | 0.256 (0.251) | |

| Impact of European Parliament | 0.998** (0.309) | 1.024** (0.314) | 0.851** (0.296) | 0.419 (0.289) | 0.422 (0.286) | |

| Constant | 7.217*** (0.245) | 3.960*** (0.529) | 3.522*** (0.553) | 3.479*** (0.504) | 3.044*** (0.498) | 2.413*** (0.496) |

| R2 | 0.055 | 0.16 | 0.169 | 0.219 | 0.273 | 0.308 |

| N | 699 | 699 | 699 | 699 | 699 | 699 |

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; robust standard errors in parentheses; see Appendix for variable coding.

We can see that turnout intention is indeed predicted to be lower for all younger age groups. The gap between these groups and the reference group of citizens over 30 is quite large: on average, respondents in the youngest groups assess their intention to vote over 1 unit lower than the reference group. The results also underline that there are only small differences between young people under and just over 18. Concerning the socio-demographic controls, we find that education is significantly associated with higher levels of voting intention. The coefficients of the other controls are in the expected direction but are not significant. Importantly, including basic, mainly socio-demographic controls does not account for the age gap in turnout, so it is not young citizens' place of residence or their migration background that explains lower rates of electoral participation.

Model 2 adds two further groups of controls: first, measures of democratic dissatisfaction and alienation; and second, support for European integration. In general, we expect respondents who trust institutions, believe that they have an important influence and are satisfied with politics to also be more likely to vote. The attitude towards European unification is included as a control as, given that we measure turnout in EP elections, citizens may want to abstain because they disapprove of the EU as a whole. In the model, the only significant effects are for the variables measuring institutional trust and the perceived political impact of the national and European parliaments on the respondent's life. Moreover, these added controls do not substantively affect the interpretation of the key age group dummy for young people under 18.

Next, in Models 3–6 we add our main independent variables measuring the ability and motivation to engage in politics, first separately and then jointly. We start in Model 3 adding our variable measuring political knowledge; we remove this in Model 4 and add non-electoral participation; Model 5 tests only the effect of political interest; and finally Model 6 includes all three controls. In each of these models, our added variables are clearly significant, so they influence people's stated intention to turn out to vote. Yet, the nature of the age gap remains. As pointed out above, if these variables did explain lower levels of turn out among citizens under 18, then they would cause the coefficients of the dummy variables for the youngest age group to shrink or even cease to be significant. However, we find that the coefficient for the 16-to-17 age group decreases only by a very small amount (0.14 units). This means that the lower turnout levels of citizens under 18 cannot satisfactorily be explained by the fact that they are not motivated or able to engage in politics.17 Interestingly, it is if anything the age group of young people aged 18–21 where we can observe a decrease in the size of this group's coefficient. Thus, citizens just over 18 appear to be substantively influenced by their lacking ability and motivation to vote, but not citizens just under 18.

In sum, the results show while turnout among under-18s is indeed lower than among Austrians in general, this is not primarily due to a lack of knowledge or interest nor due to democratic dissatisfaction and alienation. H2a and H2b are both rejected.

4.3. The quality of decision of voters under 18

The quality of electoral participation among citizens under 18 goes beyond the reasons that drive abstention: it is the concern that voters under 18 do not choose the party that best represents their views or interests. Thus, we analyse whether the quality of the vote decisions taken by voters under 18 once they turn out to vote is any different from those of older voters.

We examine vote choice quality directly, though of course this is a concept that is difficult to estimate. We operationalise it as the ideological congruence between voters and the party they want to vote for: the greater the ideological similarity between a voter and the party she chooses, the higher the quality of vote choice. This is a simplified approximation of the conventional operationalisation of ‘correct voting’, which uses measures of voter preferences on a number of different issues by which the competing candidates or parties can be distinguished, as well as on some defensibly objective measure (such as expert judgements) of where the candidates actually stand on those same issues (e.g. Lau and Redlawsk, 1997; Lau et al., 2008).18 Although such detailed measures are not available to us, we believe our simplified approach provides a good indication of whether voters choose a party that is ideologically relatively close to them.

Our main comparison concerns voter-party congruence on the left–right dimension. This dimension can be considered a shortcut or heuristic that voters use in order to simplify ideological competition. The left–right dimension has been found to provide an appropriate measure of citizens' general ideological orientations (Fuchs and Klingemann, 1990; Huber, 1989) and to influence vote choice, also in Austria (Hellwig, 2008). Thus, we use the left–right shortcut device to test our hypothesis.

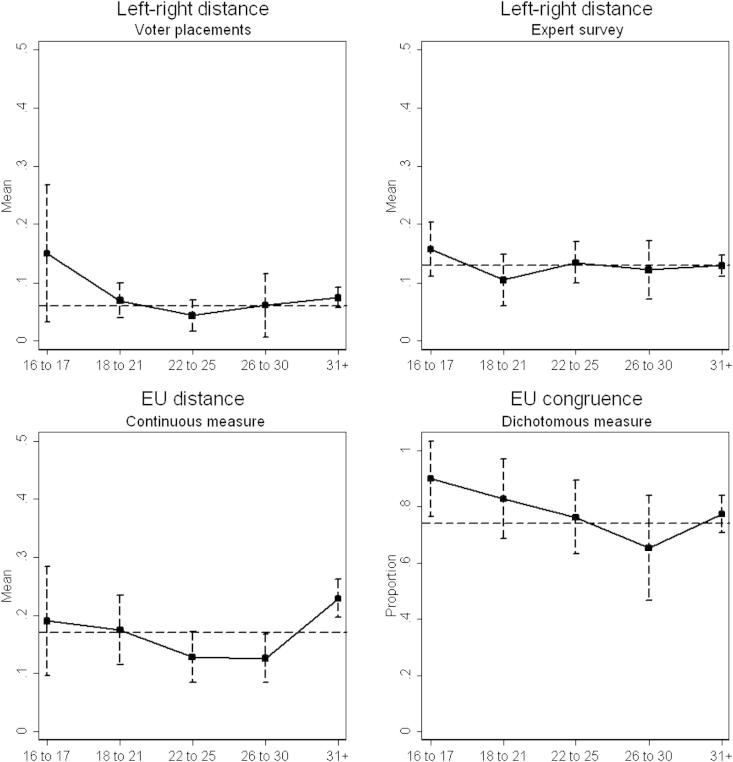

We measure congruence on the left–right dimension as the absolute distance of the voter from the party she voted for. Voter positions are measured using respondent self-assessments on a 0–10 left–right scale. Our first version of the left–right congruence measure compares this self-assessment with the voter's own placement of the party she voted for; the mean absolute left–right distances for our five age groups are shown in the top-left graph of Fig. 4.19 Second, we compared respondent self-placements with expert survey scores from Hooghe et al. (2010), who asked their respondents to place Austrian parties on a general 0–10 left–right scales; these results are shown in the top-right graph. We can see that there are no significant differences between the different groups of voters for either left–right measure. While the mean distance is slightly higher among the younger voters, the difference is minimal.

Fig. 4.

Quality of vote choice, age group differences. Note: mean values by age group shown; bars indicate 95% confidence intervals around the mean; dashed line indicates overall mean; see Appendix for question details.

As the survey was carried out in the context of EP elections, it might be that voters at that time cared more about congruence on the dimension of European integration rather than on the general left–right dimension. We present these results in the bottom two graphs in Fig. 4. Since the survey contains no assessments of party positions on this topic, we again use the Hooghe et al. (2010) scores, who asked experts to score parties on their ‘overall orientation towards European integration’ using a 1–7 scale which we rescaled to range from 0 to 10. We carry out two comparisons. First, we compare voter's positions on European unification with rescaled party scores (bottom-left graph). Second, we divide voters into two groups – sceptical and not sceptical of integration – and compare these with Hooghe et al.'s dichotomised measure of party positions (bottom-right graph).20 Both measurement approaches show that there are no significant differences between age groups. To the extent that differences – even if not statistically distinguishable – are present, it is the younger voters whose vote choice is more congruent with party positions on European integration. This is an indication that voters under 18 put some emphasis on the issues that the election, in this case the EP election, is about.

In sum, when considering the precise choices made, we have no convincing evidence that the voting decisions of voters under 18 are in any way of lesser quality, that is, less congruent, than that of older groups of voters. There is thus no evidence in favour of H3.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Critics of lowering the voting age to 16 have argued that such teenage citizens are not able or motivated to participate effectively in politics and that this both drives their turnout decisions and means that their electoral choices are of lower quality. We have tested whether these criticisms have an empirical basis using evidence from Austria, the one European country where the voting age has already been lowered for nation-wide elections.

Our findings prove the critics wrong. First, we do not find that citizens under 18 are particularly unable or unwilling to participate effectively in politics. Second, while turnout among this group is relatively low, we find no evidence that this is driven by a lacking ability or motivation to participate. Instead, 18- to 21-year-olds are if anything the more problematic group. Finally, we do not find that the vote choices of citizens under 18 reflect their preferences less well than those of older voters do. In sum, lowering the voting age does not appear to have a negative impact on input legitimacy and the quality of democratic decisions. This means that the potential positive consequences of this reform merit particular consideration and should also be empirically studied.

Is it possible to generalise from the Austrian experience? We believe so. It is not the case that Austrian teenagers are particularly unusual in a comparative context. If anything, there are two features of the Austrian case that would indicate that young Austrians are not particularly interested or engaged in politics. For one, the general educational test scores of Austrian school-children are relatively low compared to other OECD countries (OECD, 2011). Moreover, there is evidence that it is young voters in Austria who are most likely to turn to protest parties such as those on the radical right (e.g. Wagner and Kritzinger, 2012; Schwarzer and Zeglovits, 2009). Thus, we do not think that Austrians under 18 are likely to be outliers in their political interest and knowledge compared to teenagers in other countries; if anything, Austria would be a country where we might expect citizens under 18 to be particularly unmotivated to participate in politics.

It is also important to note that our study has focused on one point in time. It is therefore impossible for us to distinguish between cohort and age effects. In other words, we cannot say with certainty whether citizens under 18 compare favourably with citizens over 18 because of their age or because of their cohort. However, it is unlikely that there will be strong cohort differences between such small differences in ages, so we believe our findings should reflect general age differences rather than time-specific cohort differences.

Finally, our study leaves many questions for future research. A particularly important question – especially in the light of our results of the 18–21 age group – is the existence of a habit of voting among teenage citizens (Franklin, 2004). Specifically, it may be easier to instil a habit of voting among those who are still in school and live at home. However, observing a habit requires longer-term data, and citizens under 18 have only had the vote in Austria for four years and in one national parliamentary election. We hope that future research will examine whether today's teenage citizens will be more likely to develop a habit of voting than citizens who were first able to vote at an older age.

A further important topic is the nature of participation among young people today. Dalton (2009) has argued that younger generations are engaged in a variety of social and political activities beyond voting, with more direct, action-oriented participation on the increase. Several authors have found supporting evidence for this from the UK (Henn et al., 2005, 2002; O'Toole et al., 2003). Dalton's argument also fits with one our findings, namely that younger people are more likely to say that they would demonstrate in support of their political goals. Younger citizens might see voting as less essential and instead turn to non-electoral forms of participation in order to influence political outcomes. For young citizens, norms of engaged citizenship may be changing. While overall turnout rates would suggest a decrease of the bond between citizens and the democratic political system, new participation forms might mean that citizens are actually just as politically active as before, or possibly even more so. Future research should explore these other forms of political participation and assess the extent to which they are replacing voting as the primary way of engaging with politics, especially for citizens under 18.

To conclude, our findings show that a key criticism of lowering the voting age to 16 does not hold: there is little evidence that these citizens are less able or less motivated to participate effectively in politics. This means that critics of lowering the voting age to 16 need to look again at the arguments they use, and that there are important reasons to consider the potential positive impact of such a reform more closely.

Footnotes

This research is conducted under the auspices of the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES), a National Research Network (NFN) sponsored by the Austrian Research Fund (FWF) (S10903-G11). The authors would like to thank Mark Franklin, Kasper M. Hansen, Wolfgang C. Müller, Kaat Smets, Eva Zeglovits and the anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article, which was also presented at the Colloquium of the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES) and the PSAI-Conference, Dublin.

In Austria the voting age was lowered to 16 for national elections in 2007. Five German Länder have also changed the minimum voting age to 16, and the reform now has official backing of all main British parties apart from the Conservatives (Votes at 16, 2008).

Low turnout is also a concern when the preferences of non-voters are different from those of voters (Lutz and Marsh, 2007). In the case of young people under 18, there are two potential problems. First, those under 18 may have different preferences than those over 18, so low turnout of citizens under 18 may mean that their interests are less well-represented. Second, among young people under 18, there may be a bias in who votes and who does not. This would again result in unequal representation of interests. In both cases, this would have negative consequences for democracy (Verba, 2001). However, examining the problem of unequal representation goes beyond the scope of this paper.

Of course, it is occasionally argued that lower turnout rates are an indication of high satisfaction with democracy (e.g. Lipset, 1959; Dittrich and Johansen, 1983). From this perspective lower turnout rates, particularly amongst young voters, do not endanger the health of democracy.

Instead of the expected long term positive effect, such as encouraging voting as a habit (Franklin et al., 2004), lowering the voting age may thus rather stimulate habitual non-voting (Electoral Commission, 2004).

However, the literature provides a substantial amount of reasons why young citizens under 18 and citizens aged 18 or more are different from each other: for example, young people under 18 are more likely to live at home with their families and to still attend school, leading to potentially different socialisation effects at the time of their first election (e.g. Highton and Wolfinger, 2001).

According to the Electoral Commission (2004), the following other countries have a voting age under 18: Iran (15); Brazil, Cuba, and Nicaragua (16); and East Timor, Indonesia, North Korea, the Seychelles and the Sudan (17).

The data can be downloaded from http://methods.univie.ac.at/.

Those under 25 are commonly seen as young (e.g. European Commission, 2001); we add another group of citizens up to 30 as they would typically still be considered as young in Austria (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft, Familie und Jugend, 2011) and a quarter of Austrian university students are aged between 25 and 29 and only half under 25 (Eurostat, 2011). It may be a concern that turnout will decline in old age, therefore obscuring differences between younger and older voters (Bhatti and Hansen, 2010). We also ran our analysis leaving out voters over 65; our results remain the same.

The texts of the key questions used in these analyses are in the Appendix.

However, there is also evidence that personal traits are not correlated with the tendency to over-report (Rubenson et al., 2004).

We also ran our analyses using three dichotomised versions of this variable, with responses coded as certain to vote if they were (1) at or over 8, (2) at or over 9 or (3) at 10; no noteworthy differences between our results and the results from the models were found.

Turnout information from the Austrian Federal Ministry for the Interior (http://www.bmi.gv.at/cms/bmi_wahlen/europawahl/2009/).

For coding details, see Appendix.

Political interest can be a problematic variable in turnout models. The decision to turn out to vote may increase interest, reversing the causality the model assumes, and it may be that interest and turnout intention are in any case highly related concepts (Rubenson et al., 2004; Denny and Doyle, 2008). The strong effect of the interest variable underlines this possibility. Our results excluding political interest show that the interpretation of the age gap does not depend on this one variable.

Besides, they include additional measures of correct vote decision, e.g. by considering which of those different issues any voter believed to be more or less important (Lau et al., 2008).

Of course, note that these graphs necessarily only include voters who felt able to position parties in the first place and thus have a minimal level of political knowledge.

Voters who oppose integration are those who say that membership of the EU creates mainly disadvantages for Austria; respondents who do not give that answer are coded as not being sceptical of integration.

Contributor Information

Markus Wagner, Email: markus.wagner@univie.ac.at.

David Johann, Email: david.johann@univie.ac.at.

Sylvia Kritzinger, Email: sylvia.kritzinger@univie.ac.at.

Appendix. Variable coding

Trust in institutions

The respondents' trust in institutions was measured as the average of four questions concerning trust in the Austrian parliament and government, the EP and the European Commission. The variable was rescaled to range from 0 to 1. The alpha reliability coefficient of the scale is 0.86.

Satisfaction with national and EU democracy

Satisfaction with national and EU democracy are each measured using a four-point scale, with answers rescaled to range from 0 to 1.

Participation beyond voting

The willingness to engage in each of the five activities was rated on a four-point scale. Overall non-electoral political participation was measured as the average answer to the five questions. The scale ranges from 0 to 1. The alpha reliability coefficient of this scale is 0.75.

Interest in politics

The respondents' interest in politics is measured as the average of answers to eight questions tapping attention to politics in general and the EP campaign in particular. The variable was rescaled to range from 0 to 1. The alpha reliability coefficient of the scale is 0.81.

Political knowledge

Political knowledge is measured by assessing whether respondents correctly place the Social Democrats (SPÖ) to the left of the two far-right parties (FPÖ and BZÖ) and the People's Party (ÖVP).

Attitude towards European integration

The attitude towards European integration is measured using a question asking for opinions on whether the EU had integrated too much already or should integrate more, on a 10-point scale. This was rescaled to range from 0 to 1, with positive values indicating a pro-integration opinion.

Impact of the national parliament

The impact of the national parliament is 1 for respondents who say that the parliament has a ‘strong’ impact on them personally, 0 otherwise.

EP impact

EP impact compares the perceived influence of the national parliament and the EP; it is 1 if the EP is not seen as weaker than the national parliament. Specifically, it is coded 0 if the EP is the EP is seen as having a low or no impact and the national parliament has a strong impact, 1if not.

Education

Education is coded as 1 if the respondent is at or went to university or is at a school leading to a degree that allows university entrance; other respondents coded as 0.

Gender

Gender is coded 1 for women, 0 for men.

Migration background

Migration background is 1 if the respondent or one of his/her parents was born outside of Austria, 0 if not.

Rural residence

Rural residence is coded 1 for those living in a village in a rural area, in a village near a medium-sized or large city, or in a small rural town and coded 0 otherwise.

References

- Aarts K., Wessels B. Electoral turnout. In: Thomassen J., editor. The European Voter. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. pp. 64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein R., Chadha A., Montjoy R. Overreporting voting: why it happens and why it matters. The Public Opinion Quarterly. 2001;65(1):22–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti Y., Hansen K.M. 2010. How Turnout Will Decline as the Western Population Grows Older. Paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, Münster, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Blais A., Rubenson D. 2007. Turnout Decline: Generational Value Change or New Cohorts' Response to Electoral Competition.http://www.politics.ryerson.ca/rubenson/downloads/turnout_generations.pdf Manuscript, Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Blais A., Gidengil E., Nevitte N., Nadeau R. Where does turnout decline come from? European Journal of Political Research. 2004;43:221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Blais A. University of Pittsburgh Press; Pittsburgh: 2000. To Vote or not to Vote: The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Bolstein R. Predicting the likelihood to vote in pre-election polls. The Statistician. 1991;40:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft, Familie und Jugend . 2011. Sechster Bericht zur Lage der Jugend in Österreich.http://www.bmwfj.gv.at/Jugend/Forschung/jugendbericht/Seiten/Jugendbericht%202011.aspx Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Chan T.W., Clayton M. Should the voting age be lowered to sixteen? Normative and empirical considerations. Political Studies. 2006;54:533–558. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton R.J. CQ Press; Washington D.C: 2009. The Good Citizens. How a Younger Generation is Reshaping American Politics. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins R., Cornwell E. The Guardian (13th December) 2003. Dodgy frontal lobes, y'dig? The brain just isn't ready to vote at 16. [Google Scholar]

- Denny K., Doyle O. Political interest, cognitive ability and personality: determinants of voter turnout in Britain. British Journal of Political Science. 2008;38(2):291–310. [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich K., Johansen L.N. Voting turnout in Europe, 1945–1978: myths and realities. In: Daalder H., Mair P., editors. Western European Party Systems: Continuity and Change. Sage; London: 1983. pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Electoral Commission . 2004. Age of Electoral Majority: Report and Recommendations.http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/data/assets/pdf_file/0011/63749/Age-of-electoral-majority.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . 2001. White Paper: A New Impetus for European Youth.http://ec.europa.eu/youth/archive/whitepaper/download/whitepaper_en.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat . 2011. Eurostat Database.http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Fieldhouse E., Trammer M., Russel A. Something about young people or something about elections? Electoral participation of young people in Europe: evidence from a multilevel analysis of the European Social Survey. European Journal of Political Research. 2007;46(86):797–822. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin M., Marsh M., Lyons P. The generational basis of turnout decline in established democracies. Acta Politica. 2004;39(2):115–151. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin M. The dynamics of electoral participation. In: LeDuc L., Niemi R.G., Norris P., editors. Comparing Democracies 2. New Challenges in the Study of Elections and Voting. Sage Publications; London/Thousand Oaks: 2002. pp. 148–168. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin M. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies Since 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D., Klingemann H.-D. The left–right schema. In: Jennings M.K., Van Deth J.W., editors. Continuities in Political Action. Walter de Gruyter; Berlin: 1990. pp. 203–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D., Klingemann H.-D. Citizens and the state: a changing relationship? In: Klingemann H.-D., Fuchs D., editors. Citizens and the State. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1995. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gidengil E., Hennigar M., Blais A., Nevitte N. Explaining the gender gap in support for the new right: the case of Canada. Comparative Political Studies. 2005;38(10):1171–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Hart D., Artkins R. American sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds are ready to vote. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences. 2011;633:201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig T. Explaining the salience of left-right ideology in postindustrial democracies: the role of structural economic change. European Journal of Political Research. 2008;47(6):687–709. [Google Scholar]

- Henn M., Weinstein M., Wring D. A generation apart? Youth and political participation in Britain. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations. 2002;4:167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Henn M., Weinstein M., Forrest S. Uninterested youth? Young people's attitudes towards party politics in Britain. Political Studies. 2005;53:556–578. [Google Scholar]

- Highton B., Wolfinger R.E. The first seven years of the political life cycle. American Journal of Political Science. 2001;45(1):202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe L., Bakker R., Brigevich A., de Vries C., Edwards E., Marks G., Rovny J., Steenbergen M. Reliability and validity of measuring party positions: the chapel hill expert surveys of 2002 and 2006. European Journal of Political Research. 2010;49(5):575–704. [Google Scholar]

- Huber J.D. Values and partisanship in left–right orientations: measuring ideology. European Journal of Political Research. 1989;17(5):599–621. [Google Scholar]

- Karp J.A., Brockington D. Social desirability and response validity: a comparative analysis of overreporting voter turnout in five countries. The Journal of Politics. 2005;67(3):825–840. [Google Scholar]

- Kritzinger S., Heinrich H.-G. University of Vienna; Vienna: 2009. European Parliament Election 2009 – Pre-Elction Study.http://methods.univie.ac.at/data/ Availalbe at: [Google Scholar]

- Lau R.R., Redlawsk D.P. Voting correctly. American Political Science Review. 1997;91(3):585–599. [Google Scholar]

- Lau R.R., Andersen D.J., Redlawsk D.P. An exploration of correct voting in recent U.S. presidential elections. American Journal of Political Science. 2008;52(2):395–411. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset S.M. Bobbs-Merrill; 1959. Economic Development and Political Legitimacy. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz G., Marsh M. Introduction: consequences of low turnout. Electoral Studies. 2007;26(3):539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Nevitte N., Blais A., Gidengil E., Nadau R. Socioeconomic status and nonvoting: a cross-national comparative analysis. In: Klingemann H.D., editor. The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2009. pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2011. Education at a Glance.http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/61/2/48631582.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole T., Lister M., Marsh D., Jones S., McDonagh A. Tuning out or left out? Participation and nonparticipation among young people. Contemporary Politics. 2003;9(1):45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkin H. University of California Press; Los Angeles: 1967. The Concept of Representation. [Google Scholar]

- Plutzer E. Becoming a habitual voter: inertia, resources, and growth in young adulthood. American Political Science Review. 2002;96(1):41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Power Commission . 2006. Power to the People: The Report of Power: an Independent Inquiry into Britain's Democracy.http://www.powerinquiry.org/report/documents/PowertothePeople_002.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R. Simon and Schuster; New York: 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenson D., Blais A., Fournier P., Gidengil E., Nevitte N. Accounting for the age gap in turnout. Acta Politica. 2004;39(4):407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf F. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer S., Zeglovits E. Wissensvermittlung, Politische Erfahrungen und Politisches Bewusstsein als Aspekte Politischer Bildung sowie deren Bedeutung für Politische Partizipation. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft. 2009;38(3):325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L., Cauffman E., Woolard J., Graham S., Banich M. Are adolescents less mature than adults? Minors' access to abortion, the juvenile death penalty, and the alleged APA “flip-flop”. American Psychologist. 2009;64(7):583–594. doi: 10.1037/a0014763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomassen J. Introduction. In: Thomassen J., editor. The European Voter: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tóka G. Expressive versus instrumental motivation of turnout, partisanship, and political learning. In: Klingemann H.-D., editor. The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2009. pp. 269–307. [Google Scholar]

- Topf R. Electoral participation. In: Klingemann H.-D., Fuchs D., editors. Citizens and the State. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1995. pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Topf R. Beyond electoral participation. In: Klingemann H.-D., Fuchs D., editors. Citizens and the State. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1995. pp. 52–91,. [Google Scholar]

- Verba S. Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. Political Equality. What Is It? Why Do We Want It?http://www.russellsage.org/sites/all/files/u4/Verba.pdf Working Paper Series, Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Votes at 16 . 2008. 16 for 16: 16 Reasons for Votes at 16.http://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/downloads/16for16.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M., Kritzinger S. Age group differences in issue voting: the case of Austria. Electoral Studies. 2012;31(2) doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2012.01.007. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattenberg M.P. Pearson Longman; New York: 2008. Is Voting For Young People? [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger R.E., Rosenstone S.J. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1980. Who Votes? [Google Scholar]