Abstract

Osterix (Osx) is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation, because mice lacking Osx die within 1 h of birth with a complete absence of intramembranous and endochondral bone formation. Perinatal lethality caused by the disruption of the Osx gene prevents studies of the role of Osx in bones that are growing or already formed. Here, the function of Osx was examined in adult bones using the time‐ and site‐specific Cre/loxP system. Osx was inactivated in all osteoblasts by Col1a1‐Cre with the activity of Cre recombinase under the control of the 2.3‐kb collagen promoter. Even though no bone defects were observed in newborn mice, Osx inactivation with 2.3‐kb Col1a1‐Cre exhibited osteopenia phenotypes in growing mice. BMD and bone‐forming rate were decreased in lumbar vertebra, and the cortical bone of the long bones was thinner and more porous with reduced bone length. The trabecular bones were increased, but they were immature or premature. The expression of early marker genes for osteoblast differentiation such as Runx2, osteopontin, and alkaline phosphatase was markedly increased, but the late marker gene, osteocalcin, was decreased. However, no functional defects were found in osteoclasts. In summary, Osx inactivation in growing bones delayed osteoblast maturation, causing an accumulation of immature osteoblasts and reducing osteoblast function for bone formation, without apparent defects in bone resorption. These findings suggest a significant role of Osx in positively regulating osteoblast differentiation and bone formation in adult bone.

Keywords: Osterix, Col1a1‐Cre, osteopenia, osteoblast differentiation, adult bone formation

INTRODUCTION

Bone is a dynamic, living tissue. The skeleton and its various skeletal elements are composed of two tissues, cartilage and bone, and three cell types, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts. 1 , 2 , 3 The complexity of the bone regulation system involves the coupling between bone‐forming osteoblasts and bone‐resorbing osteoclasts because osteoblasts control the degree of osteoclastic activity. 4 , 5 , 6 Osteoblasts have been widely studied over the past century to improve our understanding of bone remodeling. These cells arise from osteoprogenitor cells in the periosteum and bone marrow. Osteoprogenitor cells differentiate into osteoblasts and, in fact, the mature bone cells are responsible for mineralization of the osteoid matrix, which is composed mainly of type I collagen. Osteoblasts trapped in the bone matrix become osteocytes, and these major mechanosensory cells in bone cease to generate osteoid and mineralized matrix.

Runx2 and Osterix (Osx) are master genes for osteoblast differentiation and function. Runx2 is a well‐characterized transcriptional regulator that is expressed in prehypertrophic chondrocytes and osteoblasts and plays multiple roles during chondrogenesis and osteogenesis. 7 , 8 , 9 Runx2‐deficient mice or C terminus–truncated Runx2 mice show a complete lack of both intramembranous and endochondral ossification caused by the absence of osteoblast differentiation. 7 , 10 , 11 , 12 Osx is a novel zinc finger‐containing transcription factor that is essential for the differentiation of pre‐osteoblasts into functional osteoblasts. (13) Osx homozygous null mutant mice show normal cartilage development but a complete absence of bone formation. Whereas no Osx expression occurs in Runx2‐deficient mice, normal expression of Runx2 is observed in osteoblasts of Osx‐null mutant mice. This indicates that the Osx gene is downstream of Runx2 and is an essential transcription factor for osteoblast differentiation. (13) However, because Osx null mutants die immediately after birth, it has not been possible to address critical questions regarding the possible role of Osx in the physiology of adult bones.

Based on previous mouse genetic studies, we hypothesized that Osx might play a significant role in osteoblast function and bone formation in adult mice. To test this hypothesis, conditional Osx knockout mice were generated to inactivate the Osx gene in osteoblasts under the control of a 2.3‐kb type I collagen promoter (Col1a1), which can drive Cre expression at high levels in osteoblasts and odontoblasts and at a specific time (after embryonic day 14.5). 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 In this study, Osx deficiency in osteoblasts under the control of the Col1a1 promoter (Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre) resulted in osteopenia in the vertebrae and a thinner, more porous cortical bone phenotype in long bones with an arrest of bone turnover. These skeletal phenotypes were caused by the inhibition of osteoblast maturation and the accumulation of immature osteoblasts in the bone of adult mice and not functionally unaltered osteoclasts. Therefore, these results showed that Osx played a significant role in regulating osteoblast differentiation and bone formation in growing bone and during early bone development. Our data provide novel insight into the role of this critical transcription factor in osteoblast function and in bone maintenance after birth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of conditional Osx knockout mice with Col1a1‐Cre

Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre were generated by crossing homozygous Osx floxed mice (Osx flox/flox) (19) and Osx +/−;Col1a1‐Cre mice, which were obtained by crossing two Osx flox/+ mice and by mating Osx heterozygous mice (Osx +/−) (13) with Col1a1‐Cre transgenic mice (unpublished data), respectively. In these mice, one Osx allele contained two loxP sites surrounding exon 2 and the other Osx allele was inactive and replaced by LacZ expressed under the regulatory sequences that normally control the Osx gene; these mice also harbored the Col1a1‐Cre transgene with Cre recombinase, which is active in osteoblasts under the control of the 2.3‐kb Col1a1 promoter. In mice harboring these three alleles, routine mouse genotyping was conducted using tail genomic DNA. The flox allele was amplified to generate a 390‐bp fragment compared with 300 bp for the wildtype allele using the following primers: 5′‐CTTGGGAACACTGAAGCTGT‐3′ and 5′‐CTGTCTTCACCTCAATTCTATT‐3′. The other primers were specific for the targeted allele with LacZ gene (5′‐GCATCGAGCTGGGTAATAAGGGTTGGCAAT‐3′ and 5′‐GACACCAGACCAACTGGTAATGGTAGCGAC‐3′), the Cre transgene (5′‐ATCCG‐AAAAGAAAACGTTGA‐3′ and 5′‐ATCCAGGTTACGGATATAGT‐3′), and the deleted Osx exon 2 (Δex) allele (5′‐CTTGGGAACACTGAAGCTGT‐3′ and 5′‐GCAC‐ACCGGCCTTATTCC‐3′) to amplify 860‐, 700‐, and 544‐bp fragments, respectively. All procedures concerning animal experiments were conducted with the approval of Kyungpook National University.

Histological and histomorphometric analysis

Mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C overnight. Long bones of postnatal mice were decalcified, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 6–8 μm, and stained with H&E and Alcian blue. Von Kossa staining was performed in undecalcified vertebrae that were embedded in destabilized methyl‐methacrylate according to standard protocols. (20) In vivo cell proliferation was assessed by BrdU incorporation (Zymed) and apoptotic cells were visualized by TUNEL analysis, using the TACS 2 TdT‐DAB In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Trevigen). For the assessment of dynamic histomorphometric indices, mice were injected with calcein at a dose of 30 mg/kg body weight at 6 and 2 days before death. Static and dynamic histomorphometric analysis was conducted using TAS image analysis systems (TAS; Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany), Bioquant programs (Bio‐Quant), and the OsteoMeasure histomorphometry system (OsteoMetrics). (21) Statistical differences were assessed by the t‐test.

μCT analysis

For 3D morphological and histomorphometric analysis, the mouse femur was scanned using the eXplore Locus SP scanner (GE Healthcare) at 8‐μm resolution. All morphometric parameters were determined using eXplore MicroView version 2.2 (GE Healthcare). The mineralized tissues were differentially segmented by a global thresholding procedure. In the femora, three preselected regions were analyzed: whole bone, the distal metaphysis extending proximally 1.75 mm from the proximal tip of the primary spongiosa, and a diaphyseal segment extending 0.25 mm proximally and distally from the midpoint between the femoral ends.

TRACP staining and osteoclast activity assays

TRACP staining of osteoclasts was performed on deparaffinized bone sections according to the manufacturer's instructions. After incubation in TRACP reagent, sections were washed in water and counterstained with methyl green. In vivo osteoclast activity was measured in urine samples collected from sex‐ and age‐matched mice. The urinary excretion of deoxypyridinoline (DPD) cross‐links was determined using Metra DPD EIA (Quidel) and QuantiChromC reatinine Assay Kits (Bioassay) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative real‐time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from long bones at 4 wk of age using TRI REAGENT (Sigma‐Aldrich). RNA was subjected to quantitative real‐time PCR using 2× SYBR Green Master mix reagent (Applied Biosystems). The following primers for marker genes of osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation were used: Osx, 5′‐GCAACTGGCTAGGTG‐GTGGTC‐3′ and 5′‐GCAAAGTCAGATGGGTAAGTAGGC‐3′; Runx2, 5′‐AAATGC‐CTCCGCTGTTATGAA‐3′ and 5′‐GCTCCGGCCCACAAATCT‐3′; Bsp, 5′‐ACCCCA‐AGCACAGACTTTTGA‐3′ and 5′‐CTTTCTGCATCTCCAGCCTTCT‐3′; Col1a1, 5′‐CCTGAGTCAGCAGATTGAGAACA‐3′ and 5′‐CCAGTACTCTCCGCTCTTCCA‐3′; osteocalcin (OCN), 5′‐GCGCTCTGTCTCTCTGACCT‐3′ and 5′‐ACCTTATTGCCCT‐CCTGCTT‐3′; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 5′‐AACCCAGACACAAGCATTCC‐3′ and 5′‐GCCTTTGAGGTTTTTGGTCA‐3′; osteopontin (OPN), 5′‐TGCACCCAGATCCTA‐TAGCC‐3′ and 5′‐CTCCATCGTCATCATCATCG‐3′; RANKL, 5′‐GCAGAAGGAAC‐TGCAACACA‐3′ and 5′‐GATGGTGAGGTGTGCAAATG‐3′; osteoprotegerin (OPG), 5′‐AGCTGCTGAAGCTGTGGAA‐3′ and 5′‐GGTTCGAGTGGCCGAGAT‐3′; TRACP, 5′‐CGACCATTGTTAGCCACATACG‐3′ and 5′‐TCGTCCTGAAGATACTGCAGGT‐T‐3′; cathepsin K (CathK), 5′‐ATATGTGGGCCAGGATGAAAGTT‐3′ and 5′‐TCGTT‐CCCCACAGGAATCTCT‐3′; and MMP9, 5′‐GCCCTGGAACTCACACGACA‐3′ and 5′‐TTGGAAACTCACACGCCAGAAG‐3′. Three independent measurements per sample were performed. The quantified individual RNA expression levels were normalized to GAPDH and depicted as relative RNA expression levels with the corresponding heterozygous mice (Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre) set to 1.0.

In vitro osteoblast culture and differentiation

Primary osteoblasts were isolated from calvaria of neonatal mice. For differentiation, cells were plated into 24‐well culture dishes at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and differentiated in vitro in medium supplemented with 5 mM β‐glycerophosphate and 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid. After 3 wk of culture, bone nodules were identified morphologically by alizarin red and von Kossa staining.

RESULTS

Osteoblast‐specific deletion of Osx with Col1a1‐Cre rescues the perinatal lethality of Osx null mutant mice

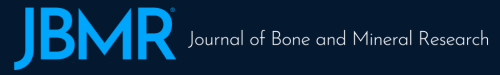

To study the role of Osx in adult bones, mice harboring a conditional floxed allele of Osx (Osx flox) (19) were used. By crossing the Col1a1‐Cre transgenic mice with Osx flox mice, the Osx gene was inactivated in osteoblasts after bone collar formation at mouse embryonic day 14.5. Finally, Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice containing one conditional Osx flox allele and one Osx‐null allele, (13) as well as a Col1a1‐Cre transgene, referred to as homozygote, were generated (Fig. 1A). Osx flox/+ and Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice were also generated for wildtype and heterozygous controls, respectively (Fig. 1A). Mice were genotyped by PCR of tail genomic DNA to identify Osx flox/+, Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre, and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 1B). Unlike perinatal lethality by Osx gene disruption, (13) Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice were viable and analyzed as heterozygous control and null mutant, respectively.

Figure Figure 1.

Generation of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice. (A) Breeding scheme to generate Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice. Col1a1‐Cre transgenic mice were used to excise Osx in osteoblasts. Finally, Osx flox/+, Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre, and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre were generated as wildtype, heterozygous, and null mutant mice, respectively. (B) PCR genotyping by tail genomic DNA. Tail genomic DNA was isolated in Osx flox/+ (Wt), Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre (Het), and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (Null) mice at P10. PCR was performed using four sets of primers, flox, LacZ, Cre, and Δex, for Osx floxed allele, LacZ knock‐in allele, Cre transgene, and Osx exon 2 deletion, respectively. Pos, positive control; Neg, negative control. (C) Analysis of skeletal phenotypes in conditional Osx knockout mice with Col1a1‐Cre. Skeletons of newborn mice were stained with Alcian blue for cartilage followed by alizarin red for bone. Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre showed no bone defects compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre. (D–F) Histological analysis of femur was performed with H&E (D), Alcian blue (E), and von Kossa (F) staining. No difference between Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre newborn mice was observed in differentiating chondrocytes and mineralized bones by Alcian blue and von Kossa staining, respectively. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Osteopenia in Osxflox/–;Col1a1‐Cre adult mice

Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice appeared phenotypically normal when they were born. To study the bone phenotype, skeletons of newborns were stained with Alcian blue for cartilage and alizarin red for calcified tissue (Fig. 1C). No skeletal abnormalities were observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre. There was no significant difference in histological analysis with H&E, Alcian blue, and von Kossa staining (Figs. 1D–1F) between both newborn mice.

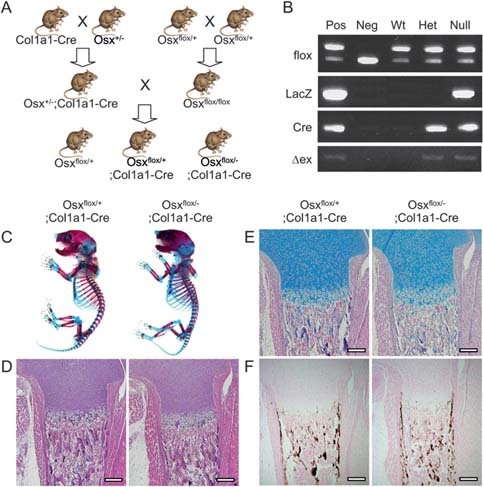

Because no clear differences were observed in newborn mice, the bones of Osx‐inactivated mice with Col1a1‐Cre were analyzed in adult mice at 8 and 16 wk of age when their bones reached peak bone mass. (22) Mineralized trabecular bones stained with von Kossa were remarkably reduced in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre at 8 wk of age (Fig. 2A). Although trabecular bones were slightly increased in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre at 16 wk compared with 8 wk of age, reduced trabecular bone volume was still observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre. Histomorphometric analysis of the fourth lumbar vertebra showed a significant reduction in cancellous bone volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular number (Tb.N), with an increase in trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 2B). As a result, Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre adult mice that lacked the Osx gene in osteoblasts failed to acquire as much bone as their control littermates and showed lower trabecular bone mass in the vertebrae throughout their lifetime.

Figure Figure 2.

Osteopenia in adult vertebra of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (A) Histological analysis of vertebrae from Osx‐inactivated mice with Col1a1‐Cre. The lumbar vertebrae of mice at 8 and 16 wk of age were analyzed with von Kossa staining, showing mineralized bones in black. Reduced mineralized trabecular bones were observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (B) Microarchitecture parameters in Osx‐inactivated mice with Col1a1‐Cre. Decreased cancellous bone volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular number (Tb.N) were measured in lumbar vertebrae of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice using TAS and Bioquant program. *p < 0.05. (C) Reduced BFR in vertebrae of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. Mice at 8 wk of age were labeled with calcein. Calcein double labeling was not obvious, and the distances between the double labeling were clearly reduced in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. Images in the bottom column are the higher‐magnification images corresponding to the top column. Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) Measurements based on fluorescent calcein labeling of mice. Dynamic indices of bone formation were quantitated by OsteoMeasure program. LS/BS, labeling surface; sLS/BS, single labeling surface; dLS/BS, double labeling surface. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

Postnatal defect in osteoblast function in Osxflox/−;Col1a1‐Cre

To determine whether Osx had an effect on osteoblast function in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice, the bone forming rate (BFR) was examined by calcein double labeling, which permitted an assessment of the dynamic and static parameters of bone formation. Double labeling with fluorescence was clearly observed on the surfaces of lumbar bones of Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice but not in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice (Fig. 2C). In the histomorphometric analysis, Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre exhibited a 2‐fold increase in the single labeling surface with a decrease in the double labeling surface (Fig. 2D). BFR, an indicator of osteoblast activity, was significantly reduced in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre, showing a functional defect of osteoblasts in vivo in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre adult mice. The mineral apposition rate (MAR), which indicates the rate of new bone deposition in the radial direction, was also remarkably decreased in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 2D). Consistent with the dominant nature of the osteopenic phenotype, these results supported the postulation that Osx inactivation in osteoblasts after bone collar formation reduced or delayed the function of osteoblasts in bone formation.

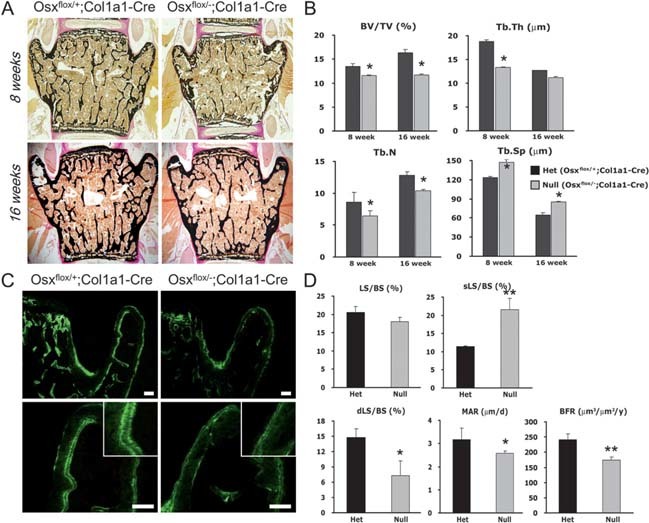

Alterations of cortical and trabecular bone with inhibition of long bone growth in Osxflox/−;Col1a1‐Cre

A more detailed characterization of the skeletal phenotype was obtained by μCT analysis. 3D μCT clearly showed a reduction of the femoral length in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre, reflecting an impaired growth of long bones in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice at 6 wk of age (Fig. 3A). A more porous osteopenic phenotype and reduced thickness of cortical bone was observed in diaphysis of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre by μCT and peripheral QCT analysis, respectively (Fig. 3B). Compared with the histomorphometry of Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice, the respective cortical area, BMD, and thickness were remarkably reduced in diaphysis of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice (Fig. 3C). In addition, the mean cortical outer and inner perimeters (Peri) were increased in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 3C), resulting in reduced cortical bone formation. The midsagittal sections of tibial bones showed an obvious abnormality of cortical bone (Fig. 3D). At 8 wk of age, thinner and more porous cortical bone was observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with the normal concrete cortical bone in Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre. Even though cortical bones were formed and thickened in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre at 16 wk compared with 8 wk of age, the cortical thickness of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre was still less than that of Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 3D).

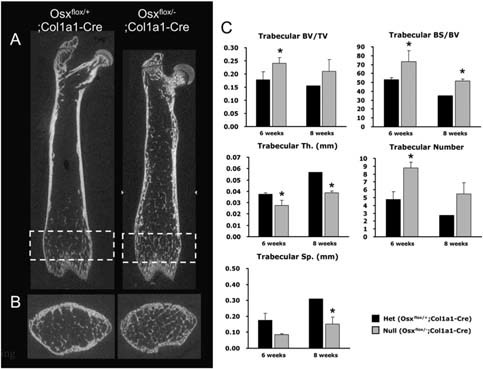

Figure Figure 3.

Analysis of cortical bone architecture in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (A) Qualitative 3D μCT imaging of femoral bone at 6 wk of age. Femoral length was reduced in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre. **p < 0.01. (B) μCT analysis in diaphysial transverse sections of cortical bone from dashed lines in A. More porous osteopenic cortical bone was observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. In analysis of femoral diaphysis by peripheral QCT, colored regions represented the cortical thickness of femoral diaphysis. The reduction in cortical bone thickness was observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (C) Histomorphometrical analysis of cortical bone at 6 and 8 wk of age. Compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice, cortical area, BMD, and thickness (Th) were decreased in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice, whereas cortical outer and inner peri‐ and marrow area were increased. *p < 0.05. (D) Histological examination of tibias stained with H&E in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice had thinner and more porous cortical bone resulting from the reduced bone formation. Each right panel (red box) was magnified in each left panel. BM, bone marrow; CB, cortical bone. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Trabecular bone morphology was confirmed in 2D longitudinal image by μCT analysis. With the osteopenic phenotype in cortical bone, many small pieces of trabecular bones were observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 4A). At the distal femoral metaphysis, trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) was higher in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre than Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre at 6 wk of age (Figs. 4B and 4C). Whereas the trabecular number was increased, trabecular thickness and separation were significantly reduced in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre, indicating that trabecular bones in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre were immature like that observed in normal newborn or young mice or were premature because of unknown alterations in bone formation without Osx (Fig. 4C). However, the growth plate of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre appeared normal compared with that of Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice, indicating that chondrogenesis was not visibly affected (data not shown). These results showed that Osx inactivation in osteoblasts delayed cortical bone formation and rendered trabecular bone formation immature or premature because of osteoblast dysfunction.

Figure Figure 4.

Analysis of trabecular bone architecture in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (A) 2D longitudinal image by μCT analysis of femoral bone at 6 wk of age. Osteopenic cortical bone and small pieces of trabecular bones were observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (B) μCT analysis of rectangled metaphysis in A. Increased immature or premature trabecular bones were observed with the osteopenic cortical bone in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (C) Histomorphometrical analysis of trabecular bone at 6 and 8 wk of age. Compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice, trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) and bone surface (BS/BV) were increased in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice, accompanied by increased trabecular numbers. However, trabecular thickness (Th) and separation (Sp) were significantly reduced in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre, indicating immature or premature trabecular bones. *p < 0.05.

No functional defect in bone resorption by osteoclasts in Osxflox/−;Col1a1‐Cre

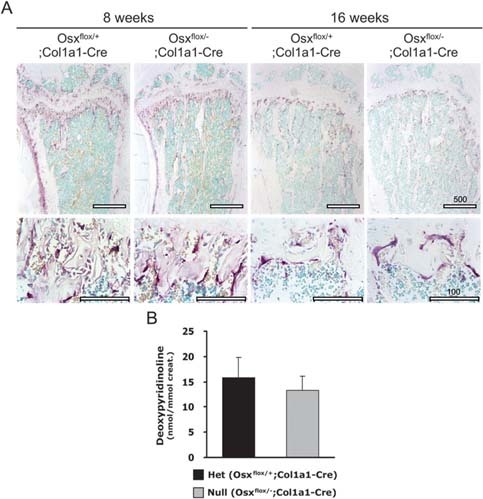

In the process of normal bone ossification, matrix degradation by bone‐resorbing osteoclasts and bone matrix as well as cartilage mineralization by bone‐forming osteoblasts are tightly coordinated. (6) Thus, TRACP+ osteoclasts were comparatively studied in trabecular regions from Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre at 8 and 16 wk of age. TRACP+ osteoclasts were detected in the periosteum, cartilage matrix, and trabecular bone surfaces of Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. Moreover, multinucleated cells representing functional osteoclasts were identical in both mice (Fig. 5A). The bone resorption aspect of bone remodeling was also analyzed by measuring the urinary elimination of DPD cross‐links, a biochemical marker of bone resorption. No difference in osteoclast activity for bone resorption was found in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice (Fig. 5B). These results indicated that Osx deficiency in osteoblasts did not affect osteoclast differentiation and function and that osteopenic phenotype in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre was not caused by bone resorption. Hence, bone resorption is likely not the causative factor for the reduced bone formation in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre.

Figure Figure 5.

No functional defect in osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (A) TRACP staining was performed in tibias to detect mature osteoclasts. TRACP+ osteoclasts (red) were observed on the surface of bone in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre with no difference compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Urinary DPD cross‐links were measured as an osteoclast activity parameter in vivo. No difference in osteoclast activity for bone resorption was observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice. The values were normalized to creatinine concentration excreted in the urine.

Altered expression of osteoblast differentiation marker genes in Osxflox/−;Col1a1‐Cre

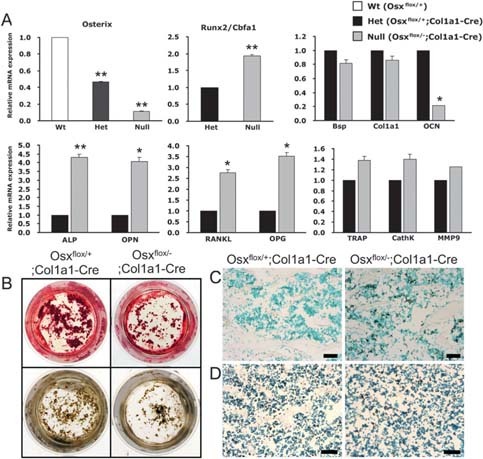

Based on the in vivo results for the reduced function of osteoblasts and the lack of functional defects in osteoclasts, quantitative real‐time PCR analysis was performed to identify the expression of marker genes related to osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation in long bones of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 6A). To verify complete Osx excision in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre, the expression of Osx gene was quantified. Compared with that in wildtype mice, Osx expression was at most 50% in Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre heterozygous mice and <10% in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre null mice, indicating that the activity of Cre recombinase was >90% in Osx‐inactivated mice with the Col1a1‐Cre transgene. Osteocalcin, a marker gene at a late stage of osteoblast differentiation, was decreased by 80% in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre. In contrast, the mRNA expression level of the pre‐osteoblast marker gene, alkaline phosphatase, and of an early marker gene of osteogenic differentiation, osteopontin, in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre was significantly higher than in Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre, whereas bone sialoprotein and Col1a1 were not affected. This indicated that osteoblasts differentiation was drastically reduced and that immature osteoblasts were increased in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. Interestingly, the mRNA expression of Runx2, which is upstream of Osx, was increased in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. Although the exact mechanism for the high level of Runx2 is not clear, it may be partly caused by the lack of Osx‐mediated negative feedback mechanism or a compensation for bone formation lacking Osx.

Figure Figure 6.

Bone cell differentiation in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (A) Expression of marker genes related to bone cell differentiation by quantitative real‐time PCR analysis. The expression of Osx was decreased by up to 90% in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with Osx flox/+ mice. In Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice, the expression of OCN, a marker gene at a late stage of osteoblast differentiation, was obviously reduced, whereas the expression of the preosteoblast marker genes, ALP and OPN, was significantly increased. The expression of OPG and RANKL was high, and the expression of osteoclast differentiation markers including TRACP, CathK, and MMP9 was not significantly changed. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001. (B) Reduced differentiation in primary calvarial osteoblasts. Differentiated osteoblasts were justified by alizarin red (top) and von Kossa (bottom) staining. The number of mineralized bone nodules was remarkably reduced in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. (C and D) Increased proliferating cells and unaltered apoptotic cells were observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre at 8 wk of age with BrdU and TUNEL staining (positive cells in black), respectively. Scale bar = 50 μm.

To confirm the change in osteoblast differentiation, the in vitro differentiation was studied in primary calvarial osteoblasts of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. The number of mineralized bone nodules was remarkably reduced in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre as shown by alizarin red and von Kossa staining (Fig. 6B). Because of the altered osteoblast differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis of osteoblastic cells were analyzed by BrdU incorporation and TUNEL staining in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre, respectively. Highly increased cells with BrdU incorporation were observed in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 6C). Even though TUNEL+ cells were slightly increased, no significant difference was statistically examined in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre (Fig. 6D and data not shown). Therefore, these results indicated that proliferation of the immature osteoblasts, which accumulated because of reduced differentiation, was increased in the long bones of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre.

With the increase of immature osteoblasts, RANKL and OPG, which are important for osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast activity, (23) were also shown to be increased (Fig. 6A). The increased level of RANKL may reflect the relative increase in immature pre‐osteoblast cells because Osx inactivation seemed to decelerate osteoblast differentiation and an increased OPG may be a compensatory mechanism to prevent bone loss in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. No significant changes were observed in the expression of the osteoclast differentiation markers, TRACP, CathK, and MMP9 (Fig. 6A). In conclusion, we observed osteopenia with decreased bone formation and irregular cortical bone structure in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre caused by increased immature osteoblasts and reduced osteoblast differentiation, without apparent defects in bone resorption.

DISCUSSION

The transcription factor Osx is essential for osteoblast differentiation during embryonic development, because mice lacking Osx show a complete absence of intramembranous and endochondral bone formation. (13) However, perinatal lethality by Osx gene disruption prevents studies of the role of Osx in adult bones. In this study, we provide evidence indicating that Osx positively regulates bone formation and maintenance after birth. To study the possible role of Osx in adult bones, we generated Osx‐inactivated mice with Col1a1‐Cre (Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre), in which the Osx gene was inactivated in all osteoblasts after bone collar formation during development. Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre newborn mice showed no significant abnormality compared with Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre mice. However, adult mice at 8 and 16 wk of age showed an osteopenic phenotype consisting of morphological changes in trabecular and cortical bone phenotypes in long bones. Furthermore, reduced BMD and BFR were reported in the lumbar vertebrae. The cortical bone of the diaphysis of long bones was thinner and more porous in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre, developing osteopenia with a subsequent loss of bone mass. These results indicated that abnormal bone formation in adults was caused by remodeling errors.

We observed an unexpected increase in the trabecular bone phenotype of the tibia and a decrease in the length of all long bones. These phenotypes of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice were similar to existing findings showing that abnormal trabecular and cortical bone regulatory mechanisms were responsible for longitudinal growth of the cortex as well as coalescence processes of endochondral trabecular bone. 24 , 25 , 26 Previous studies have reported that the trabecular bone at the periphery of the growth plate coalesces into cortical bones, whereas the central trabecular bone under the growth plate is resorbed to create the bone marrow cavity. In histomorphometrical analysis, they observed that the former was especially caused by increased bone formation by osteoblasts and not by decreased bone resorption by osteoclasts. 24 , 26 Thus, longitudinal growth of bone is affected to the coalescence of metaphyseal trabecular bone into cortical bone with increased osteoblast function for bone formation. This also means that the reduced bone growth results from the delayed coalescence of trabecular bone caused by decreased osteoblast function. Consistent with their reports, our results indicate that reduced longitudinal growth in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice was caused by delayed peripheral trabecular bone development by decreased osteoblast function without dysfunction of chondrogenesis. Moreover, even though there was no significant difference in the cortical bone formation in newborn mice, slight differences at postnatal day 3 (P3) and obvious differences at P7 were observed between Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre and Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice (data not shown). This was also confirmed by histological and μCT analysis; trabecular and cortical bones of young Osx flox/+;Col1a1‐Cre and adult Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre showed a similar phenotype (data not shown). The early‐stage and immature osteoblasts were highly increased in adult Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre, as indicated by the accumulation of osteopontin‐positive cells and a decrease of osteocalcin expression in the analysis of quantitative real‐time PCR. This observation suggested that delayed trabecular bone and osteopenic cortical bone formation resulted from the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation and the accumulation of immature osteoblasts in adult mice without Osx.

Runx2 is a well‐characterized bone transcription factor that is requisite for the maturation of hypertrophic chondrocytes and osteoblasts, whereas Osx is a downstream gene of Runx2. 9 , 10 , 27 , 28 Interestingly, in Osx‐inactivated adult mice, Runx2 expression was significantly increased. Although the exact mechanism is not yet clear at this moment, increased Runx2 expression may be partly caused by the lack of Osx‐mediated negative feedback mechanism and its expression may be controlled by the activation of the Osx‐mediated gene. Affymetrix Genechip analysis showed increases of bone factors including Runx2 in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre (unpublished data). Various factors for bone formation were significantly increased to compensate for the loss of Osx in adult bone formation, whereas matrix proteins for cartilage formation were remarkably decreased. This may also explain the increased immature or premature trabecular bones in long bones of Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice. Furthermore, Osx inactivation affected osteogenic cell proliferation. A recent report also showed that BrdU+ cells were increased in calvaria of conventional Osx‐null embryos, indicating that Osx regulates osteoblast proliferation. (29) A significant increase of proliferating osteoblastic cells in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre was indeed considered to be caused by impaired osteoblast maturation and accumulated immature osteoblasts.

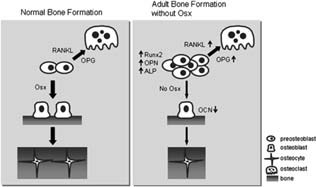

In the tightly coupled processes of osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis, failure of osteoblast differentiation affects osteoclast maturation and function. 4 , 6 Whereas delayed osteoblast differentiation was observed, there was no abnormality of osteoclast differentiation and activity in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre. It has been shown that bone transcription factors are involved in the regulation of RANKL and OPG expression, which stimulates and inhibits osteoclast differentiation and activity, respectively. 23 , 30 , 31 , 32 In our study, the expression levels of both RANKL and OPG mRNA were considerably increased in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice. The relative ratio of RANKL/OPG was not significantly changed, and hence, there was no abnormality of bone resorption in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre mice. Eventually, increased OPG may compensate for osteoclast maturation and bone resorption by increased RANKL from accumulated immature osteoblasts, after restoration of bone homeostasis. Also, the mRNA expression of osteoclast marker genes including TRACP, CathK, and MMP9 was unaltered, confirming that defects of endochondral ossifications in Osx flox/–;Col1a1‐Cre were not caused by the abnormality of osteoclasts function. Therefore, as depicted in Fig. 7, we concluded that, in the Osx‐deficient bone of adults, differentiation of pre‐osteoblasts into mature osteoblasts was delayed with subsequent accumulation of immature osteoblasts. In addition, to compensate for the lack of Osx in bone formation, Osx inactivation in adult mice resulted in accelerated osteogenic cell proliferation and subsequently in premature trabecular bone formation in long bones. Even though the expression of RANKL and OPG was increased, no functional defects were observed in osteoclast differentiation because there was no change in the relative ratio of RANKL/OPG.

Figure Figure 7.

Proposed model of bone formation governed by Osx in adult bone. With the lack of Osx during the animal's growth, differentiation of pre‐osteoblasts into mature osteoblasts is delayed and immature osteoblasts accumulate, accompanied by the increased expression of early marker genes for osteoblast differentiation. Although bones are formed, BFR and bone mass are significantly reduced. However, Osx‐inactivated adult mice have no obvious defect in osteoclast differentiation because the relative ratio of RANKL/OPG is not remarkably changed, even though the expression of RANKL and OPG is highly increased. Thus, Osx is a positive regulator in adult bone formation.

In summary, this study suggests that Osx is required for the regulation of osteoblast differentiation in vivo and for bone formation and maintenance in growing or already formed bones. Osx also has a key role in longitudinal bone growth by osteoblasts. Understanding the regulatory function of Osx in adult bone may shed light on the complex mechanisms of bone diseases and help address appropriate therapies for bone diseases such as osteoporosis and osteogenesis imperfecta.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korea Government (MOEHRD, Basic Research Promotion Fund) (KRF‐2007‐313‐E00314), the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (MOST) (R01‐2007‐000‐20005‐0), and the Brain Korea 21 Project in 2008.

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Published online on December 29, 2008

REFERENCES

- 1. Olsen BR, Reginato AM, Wang W 2000. Bone development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16: 191–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mundlos S, Olsen BR 1997. Heritable diseases of the skeleton. Part I: Molecular insights into skeletal development‐transcription factors and signaling pathways. FASEB J 11: 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karsenty G 2003. The complexities of skeletal biology. Nature 423: 316–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blair HC, Zaidi M, Schlesinger PH 2002. Mechanisms balancing skeletal matrix synthesis and degradation. Biochem J 364: 329–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karsenty G, Wagner EF 2002. Reaching a genetic and molecular understanding of skeletal development. Dev Cell 2: 389–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lemaire V, Tobin FL, Greller LD, Cho CR, Suva LJ 2004. Modeling the interactions between osteoblast and osteoclast activities in bone remodeling. J Theor Biol 229: 293–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, Karsenty G 1997. Osf2/Cbfa1: A transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell 89: 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wheeler JC, Shigesada K, Gergen JP, Ito Y 2000. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by Runt domain proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol 11: 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoshida CA, Yamamoto H, Fujita T, Furuichi T, Ito K, Inoue K, Yamana K, Zanma A, Takada K, Ito Y, Komori T 2004. Runx2 and Runx3 are essential for chondrocyte maturation, and Runx2 regulates limb growth through induction of Indian hedgehog. Genes Dev 18: 952–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choi JY, Pratap J, Javed A, Zaidi SK, Xing L, Balint E, Dalamangas S, Boyce B, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein JL, Jones SN, Stein GS 2001. Subnuclear targeting of Runx/Cbfa/AML factors is essential for tissue‐specific differentiation during embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 8650–8655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, Sato M, Okamoto R, Kitamura Y, Yoshiki S, Kishimoto T 1997. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell 89: 755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Otto F, Thornell AP, Crompton T, Denzel A, Gilmour KC, Rosewell IR, Stamp GW, Beddington RS, Mundlos S, Olsen BR, Selby PB, Owen MJ 1997. Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell 89: 765–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B 2002. The novel zinc finger‐containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 108: 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dacquin R, Starbuck M, Schinke T, Karsenty G 2002. Mouse alpha1(I)‐collagen promoter is the best known promoter to drive efficient Cre recombinase expression in osteoblast. Dev Dyn 224: 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rossert J, Eberspaecher H, de Crombrugghe B 1995. Separate cis‐acting DNA elements of the mouse pro‐alpha 1(I) collagen promoter direct expression of reporter genes to different type I collagen‐producing cells in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol 129: 1421–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braut A, Kalajzic I, Kalajzic Z, Rowe DW, Kollar EJ, Mina M 2002. Col1a1‐GFP transgene expression in developing incisors. Connect Tissue Res 43: 216–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rossert JA, Chen SS, Eberspaecher H, Smith CN, de Crombrugghe B 1996. Identification of a minimal sequence of the mouse pro‐alpha 1(I) collagen promoter that confers high‐level osteoblast expression in transgenic mice and that binds a protein selectively present in osteoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 1027–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marijanovic I, Jiang X, Kronenberg MS, Stover ML, Erceg I, Lichtler AC, Rowe DW 2003. Dual reporter transgene driven by 2.3Col1a1 promoter is active in differentiated osteoblasts. Croat Med J 44: 412–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akiyama H, Kim JE, Nakashima K, Balmes G, Iwai N, Deng JM, Zhang Z, Martin JF, Behringer RR, Nakamura T, de Crombrugghe B 2005. Osteo‐chondroprogenitor cells are derived from Sox9 expressing precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14665–14670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Erben RG 1997. Embedding of bone samples in methylmethacrylate: An improved method suitable for bone histomorphometry, histochemistry, and immunohistochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem 45: 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR 1987. Bone histomorphometry: Standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 2: 595–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Somerville JM, Aspden RM, Armour KE, Armour KJ, Reid DM 2004. Growth of C57BL/6 mice and the material and mechanical properties of cortical bone from the tibia. Calcif Tissue Int 74: 469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, Shimamoto G, DeRose M, Elliott R, Colombero A, Tan HL, Trail G, Sullivan J, Davy E, Bucay N, Renshaw‐Gegg L, Hughes TM, Hill D, Pattison W, Campbell P, Sander S, Van G, Tarpley J, Derby P, Lee R, Boyle WJ 1997. Osteoprotegerin: A novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell 89: 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cadet ER, Gafni RI, McCarthy EF, McCray DR, Bacher JD, Barnes KM, Baron J 2003. Mechanisms responsible for longitudinal growth of the cortex: Coalescence of trabecular bone into cortical bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85: 1739–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Forriol F, Shapiro F 2005. Bone development: Interaction of molecular components and biophysical forces. Clin Orthop Relat Res 432: 14–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tanck E, Hannink G, Ruimerman R, Buma P, Burger EH, Huiskes R 2006. Cortical bone development under the growth plate is regulated by mechanical load transfer. J Anat 208: 73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aubin JE, Bonnelye E 2000. Osteoprotegerin and its ligand: A new paradigm for regulation of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Osteoporos Int 11: 905–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Komori T 2005. Regulation of skeletal development by the Runx family of transcription factors. J Cell Biochem 95: 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang C, Cho K, Huang Y, Lyons JP, Zhou X, Sinha K, McCrea PD, de Crombrugghe B 2008. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by the osteoblast‐specific transcription factor Osterix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 6936–6941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Khosla S 2001. Minireview: The OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology 142: 5050–5055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Subramaniam M, Gorny G, Johnsen SA, Monroe DG, Evans GL, Fraser DG, Rickard DJ, Rasmussen K, van Deursen JM, Turner RT, Oursler MJ, Spelsberg TC 2005. TIEG1 null mouse‐derived osteoblasts are defective in mineralization and in support of osteoclast differentiation in vitro. Mol Cell Biol 25: 1191–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thirunavukkarasu K, Halladay DL, Miles RR, Yang X, Galvin RJ, Chandrasekhar S, Martin TJ, Onyia JE 2000. The osteoblast‐specific transcription factor Cbfa1 contributes to the expression of osteoprotegerin, a potent inhibitor of osteoclast differentiation and function. J Biol Chem 275: 25163–25172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]