Preface

Recent deep sequencing of transcriptomes from worm to human reveals that individual transcripts can be composed of sequence segments that are not collinear — with some mapping great distances apart and others to other chromosomes. Some of these chimeric transcripts are formed by genetic rearrangements but others appear to arise during post-transcriptional events. While in lower eukaryotes, this is accomplished by a well characterized trans-splicing process, in higher eukaryotes the processes leading to their formation remains unclear. While the biological importance of most chimeric RNAs is unclear as yet, the implications of their existence to the potential information content and functional organization of genomes are profound.

Projects like the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) 1, model genome ENCODE (modENCODE)2, FANTOM 3, NIH Roadmap Epigenome 4 as well as efforts from many individual laboratories have contributed to an increasing appreciation of the pervasive transcription occurring in most genomes and the multiple functional roles that RNAs play within cells 5,6. Part of the goals of these consortia has been to map and to characterize comprehensively the transcriptomes found in human and a diverse collection of model organisms. The relatively rapid development of powerful high throughput sequencing 7 and in vivo screening techniques 8 have provided the means to accomplish these goals in a very short time. A consistent finding in all of these studies has been that non-protein coding RNAs comprise most of the transcriptional output of genomes and many of the functional systems operating within cells involve non-coding transcripts 9,10. Additionally, the mapping and sequence characterization of the RNAs involved in many of these cellular processes have resulted in interesting observations concerning the organization of information stored in genomes, the regulation of expression of these RNAs, novel biochemical processes that point to a possible function and fate of new RNA classes and the evolutionary implications highlighted by increased complexity in genome organization. In turn, the involvement of RNAs in each of these areas has prompted a reconsideration of the roles of RNA in inheritance and disease 11,12.

Organization of Information Encoded in Genomes

In eukaryotic cells the central storage units of heritable information are compartmentalized in the nucleus as DNA and as epigenetic marks etched on to the DNA itself and the associated chromatin proteins. RNA’s functional role has been seen to be primarily an intermediary that faithfully transfers information from the genome. Not surprisingly, functional roles like assisting in the synthesis of proteins by acting as a messenger (mRNA) or as a scaffold for protein synthesis (rRNAs) and assisting to gather amino acids (tRNA) for protein synthesis have encouraged the view that information stored in a genome is transferred to RNA in a collinear fashion. This means that the nucleotide sequences found in RNA transcripts are ordered in the same linear fashion as that found in the DNA genome. While the discovery of splicing has provided a more modular and non-contiguous view of this collinear relationship, the order of sequences in both DNA and RNA has been maintained (Figure 1A). This collinear organization seems logical and efficient given the perceived primacy of DNA in the genetic hierarchy. Additionally, underlying this collinear organization of information in the genome and its transfer to RNA is the premise that the sequences that will be joined together in the mature RNAs reside on the same precursor RNA molecule. Indeed this seems to be the primary path of RNA processing from primary to mature transcripts.

Figure 1. Models of possible organization of information contained in DNA and its transfer to RNA.

(A) Collinear alignments can be categorized in two forms. Directly collinear in which information (sequence) is transferred in an un-interrupted fashion to RNA as is seen in most bacterial mRNAs and modular alignments in which the information is transferred to RNA in a collinear but interrupted (by introns) fashion. (B) Non-collinear alignments can be categorized in 4 forms. The production of precursor RNAs is shown only for Form 1 but is made in all forms. Form 1 represents the formation of chimeric RNAs from two different loci in a genome at two different genic regions. The precursor RNAs are processed (e.g. by trans-splicing or RNA recombination 18) into the chimeric RNA. Form 2 exemplifies the formation of a chimeric RNA from the same gene by rearrangement of exons (see Figure 2 for example). Form 3 illustrates the formation of a chimeric RNA which is made from two precursor RNAs that are transcribed from opposite strands. Form 4 describes the formation of a chimeric RNA that is made from transcripts derived from two alleles of the same gene one of which contains a single nucleotide polymorphism.

However, structural studies of RNAs in several species have revealed that the sequences that are ultimately joined together on the same mature transcript can be encoded in separately transcribed RNAs with multiple distinct genomic origins (Figure 1B). Individual RNAs can be transcribed on separate chromosomes (Figure 1B, Form 1), on the same chromosome but with a different the genomic order from that found in the mature RNA (Figure 1B, Form 2), on the same chromosome but transcribed from different strands (Figure 1B, Form 3), or finally on the same chromosome but from different alleles (Figure 1B, Form 4).

One of the first observations that supported the joining of sequences derived from separate molecules was the discovery of trans-splicing. Discovered first in trypanosomes 13 the process was later shown to occur also in Caenorhabditis elegans and other nematodes 14, in Euglena 15, in flatworms16; 17and higher eukaryotes 18. In the cases of the worm and trypanosomes, short stretches of nucleotides (nt) mapping to separate and distal regions in their genomes are trans-spliced onto the 5′ ends of many protein coding genes. These short sequences are derived from short leader RNA genes (SL genes) that can be positioned thousands of nucleotides away, upstream or downstream (5′ or 3′, respectively) or on different chromosomes from the genes to which their sequences are spliced. Additionally, unlike cis-splicing observed in higher eukaryotic cells this trans-splicing involves the cleavage and joining of two separate transcripts.

Trans-splicing is not limited to worms and trypanosomes. Clear evidence of trans-splicing in mammalian cells is beginning to emerge. One of the most striking examples was reported in human cells by Li et al. 19. Li et al. characterized a developmentally regulated trans-splicing event involving the 5′ exons of the transcripts from the JAZF1 gene on chromosome 7p15 and the 3′exons of JJAZ1 (also known as SUZ12) located on chromosome 17q11. The fate of this chimeric RNA in endometrial stroma cells is to be translated into a chimeric anti-apoptotic protein. Interestingly, neoplastic stroma cells of the endometrium constitutively express the chimeric RNA and protein because of a translocation involving these two chromosomal regions (t(7;17 1p15q11). Thus, by two different non-overlapping mechanisms similar chimeric RNA and proteins are made in normal and genetically rearranged neoplastic cells. The expression level of the chimeric RNA in the cells containing the translocation is elevated and this loss of regulation of the expression of the chimeric gene products is similar to oncogene regulatory mutations associated with neoplastic transformation20. These studies also raise the possibility that the trans-splicing events may be a precondition for chromosomal exchange and further suggest studies to determine if chimeric RNAs, which are often found as result of such structural mutations are present in the same non-transformed cells.

A second example of a clinically important trans-spliced RNA was observed in a study of a novel erythroblast transformation specific (ETS) family fusion transcript SLC45A3-ELK4 (21). In this study, the chimeric SLC45A3-ELK4 transcript was found to be expressed in normal and benign cancer prostate cells. Characterization of the fusion mRNA revealed a major variant in which SLC45A3 exon 1 is fused to ELK4 exon 2 leading to the expression of a novel protein. Based on quantitative PCR analyses of DNA, unlike other ETS fusions described in prostate cancer, the expression of SLC45A3-ELK4 mRNA is not exclusive to the formation of chromosomal rearrangements. Similar to the JJAZ1 and JAZF1 case both the chimeric RNA and protein can be formed by either in vivo trans-splicing or a genetic rearrangement event. The SLC45A3-ELK4 chimeric RNA finding is notable for two clinical reasons. The first is that the SLC45A3-ELK4 chimeric transcript can be detected at high levels in urine samples from men at risk for prostate cancer. Second, treatment of LNCaP cell line with R1881 synthetic androgen indicated that the fusion transcript was differentially regulated, making treatment with androgen antagonists of potential therapeutic value.

The increased prevalence of chimeric RNAs in other normal cells is supported by both clinical and empirical observations. Cancer geneticists have puzzled over why chimeric RNAs are detected in normal tissues used as controls for transformed cells. As with JAZF1 and JJAZ1 genes, chimeric RNAs have been observed in spleen tissues of normal individuals involving the immunoglobin heavy chain gene (IGH) and the BCL2 gene. Interestingly a translocation (t14:18) involving the same genes is seen in neoplastic hematopoietic cells such as lymphomas22. Additionally, in other molecular biology studies designed to identify the 5′ termini of genes expressed in many different tissues and cell lines as part of the pilot phase of the ENCODE, approximately 65% of the genes tested were observed to be involved in the formation of chimeric RNAs. These genes had distal unannotated 5′ transcription start site (TSS) that were joined to RNAs from genes positioned hundreds of thousands of nucleotides 3′ to these sites. In such cases, multiple intervening genes and their corresponding transcripts were not involved in the formation of the chimeric RNAs. While these results could be examples of very long distance collinear splicing, this is unlikely since some of the genes that part-take in the formation of the chimeric RNAs are encoded on the opposite strand. However, unlike the studies conducted by Li et al 19, these normal tissues were not tested for the presences of low level rearrangement events. Recently, two studies have suggested that detection of chimeric RNAs by deep sequencing of transcriptomes of individuals could provide early detection of chromosomal rearrangements found in cancer patients 23. While the detection of chimeric RNAs may at times result from a genetic translocation event, the assumption that such rearrangements are present may prove to be misleading given that detection of chimeric RNAs arising from non-chromosomal rearrangements is possible.

These and other studies raise the intriguing question of whether chimeric RNAs that contain sequences from multiple non-collinear positions in the genome are more commonly found in normal tissues than previously appreciated. Evidence from the pilot phase of the ENCODE project 1,24,25 and other independent studies (see for example REF 26) support the prevalence of such chimeric RNA production in both normal tissues and established cell lines 18. The pilot ENCODE studies reported that approximately 65% of the protein coding genes mapping within the boundaries of the ENCODE circumscribed regions contributed to the formation of chimeric RNAs, half of which contained sequences of genes that mapped to the opposite strand of the index gene used in these studies (data not published). It is important to note that the observation of chimeric RNAs involving a large percent of genes does not imply high copy numbers for such RNAs. However, as noted by Denoeud et al. the levels of expression of exons comprising chimeric RNAs are often similar to those of the annotated transcripts24.

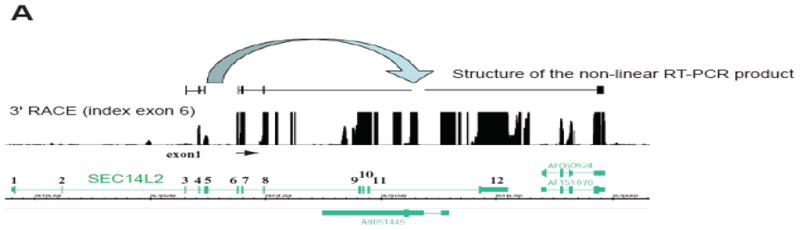

An unusual type of chimeric transcripts has been reported and is represented by chimeric RNAs that contained exon sequences that were out of order compared to the order of the exons found in the human genome. This type of non collinear representation of information in the genome is exemplified by a SEC14L2 isoform in which upstream exons were inserted between downstream exons (Figure 2). Spliced portions of exons 3, 4 and 5 were inserted downstream of exons 6, 7 and 8 and connected to the 3′ UTR of the downstream gene HSPC242 27. This arrangement preserves a large open reading frame while putting amino acids 56–93 of SEC14L2 after amino acid 218 of this protein.

Figure 2. Characterization of a chimeric transcript.

The example shows a RT-PCR product corresponding to a chimeric transcript derived from SEC14L2 gene where a spliced region corresponding to exons 4, 5 and 6 is inserted downstream of exon 8. 27 A product of 3′ RACE/array reaction is shown, with a primer positioned in exon 6; the nonsequential RT-PCR product is shown aligned to the genome. Note the RACE/array signal upstream from the RACE primer corresponding to exons 4 and 5. A portion of exon 3, which consisted of only 7 bp, is too small to hybridize to the array.

The molecular mechanisms controlling the joining of sequences from two individual RNA molecules as described in the cases described previously are still uncertain, although not without leads. Bruzik and Maniatis showed that RNA molecules containing a 3′ splice site and enhancer sequence are efficiently spliced in trans. 28,29 The products are RNA molecules containing normally cis-spliced 5′ splice sites or trans-spliced as seen with the SL-RNAs from lower eukaryotes. Additionally, Li et al 18 computationally identified chimeric RNAs in the RNA and EST databases of yeast, fly, mouse and human and have confirmed approximately 30% of them by RT-PCR reactions. Interestingly, they note that short homologous sequences (SHSs) at the junction sites of the chimeric RNAs are frequently observed and have curiously proposed a transcriptional slippage model rather than the a copy choice 30 or classic trans-splicing model 31, to explain the generation of those chimeric RNAs synthesized from templates with SHSs.

Whatever the mechanism(s) that control the formation of chimeric RNAs, their utilization in eukaryotic cells is seen from worms to humans. Nevetheless, with the exception of some well studied cases as cited previously, no function has yet been identified for the large majority of observed chimeric RNAs.

Regulation of Expression of Non-Collinear Information

The organization of information in a genome and its non-collinear transfer into RNA has implications concerning the regulation of such transcriptional processes. If information transferred to RNA can be derived from sequences found in at least two different transcripts, then either the regulation of the synthesis of the individual transcripts that are involved in the trans-splicing must be coordinated or the half-life characteristics of at least some transcripts must allow for temporally uncoordinated regulation of their expression. The coordinated regulation of expression of individual transcripts and the subsequent joining of these individual transcripts raises the possibility that these activities are carried out in close three-dimensional space in the cell.

Studies of nuclear organization in a cell indicate that non-ribosomal RNAs may be transcribed in sub-compartments or foci known as transcription factories 32 and that these factories are stably maintained in the absences of active transcription 33. Transcription factories are sites enriched in RNA polymerase II and may contain other processing factors needed to create messenger RNAs 34,35. Interestingly, for any single cell there appear to be fewer transcriptional factories than the number of expressed genes 36. This suggests that multiple genes share the same transcriptional machinery. Genes located cis and trans to one another may share the same factory, suggesting that very distal genes migrate to preassembled nuclear sites. Osborne et al. used fluorescent in situ hybridization to investigate the genes that were associated with transcription factories during immediate early (IE) gene induction in mouse B lymphocytes.37. They found that the mouse Myc proto-oncogene on chromosome 15 is recruited to the same transcription factory as the highly transcribed immunoglobulin heavy chain (Igh) gene located on chromosome 12. A similar association is seen in human cells 37. Interestingly, human Myc and Igh are the most frequent translocation partners in plasmacytoma and Burkitt lymphoma. These data suggest a direct link between the nonrandom association of two genes in an interchromosomal organization of transcribed genes located within transcription factories and the incidence of specific chromosomal translocation. While chimeric RNAs have not as yet been observed in normal plasmacytes, the 3 dimensional association of these two genes to the same transcriptional factory offers the possibility of the RNAs made from Myc and Igh to participate in a trans-splicing and possibly chromosomal translocation events, as seen with the JAZF1 and JJAZ1 and SLC45A3 and ELK4 genes described earlier. Such transcription factories capable of carrying out transcription and the formation of chimeric RNAs may be normal or specialized factories. Evidence for specialized factories has been described 36 of which the nucleolus provides an excellent example. Figure 3 shows a model for a hypothetical specialized factory. Such a model predicts a non-random correlation among the genomics sites that can be observed in close proximity in 3 dimensional space as detected by Carbon-Copy Chromosome Conformation Capture (5C)38 and genomic regions encoding transcripts that are involved in the formation of chimeric RNAs.

Figure 3. Model of specialized transcription factory in which transcription and formation of chimeric RNAs are carried out.

Based on the observation that there are fewer transcription factories in nuclei than the number of transcribed loci and the existence of specialized transcription factories 36, this model hypothesizes that genes A and B encoded in different regions of the genome are collected in a transcription factory and transcribed into primary transcripts by multiple polymerase II transcriptional complexes (white oval). The primary transcripts are then processed to form mature spliced and chimeric RNAs. In this model most of the primary RNAs are involved in cis-splicing and transported to the cytosol for translation. Consistent with steady state estimates of chimeric RNAs levels, a smaller proportion of the primary RNAs are used to create chimeric RNAs. The model can envision a single or multiple isoforms of chimeric RNAs being made from combinations of primary RNA having been transcribed within the same transcription factory. The occurrences of translocation events involving genomic regions that are transcribed to produce chimeric RNAs raises the interesting possibility that such rearrangements may also be facilitated at these specialized factories.

Evolutionary Implications

Both the information content of genomes and the strategies to transfer this information from DNA to RNA has increased over the course of evolution. The transfer of information in eukaryote cells from worm to human has also been accompanied by increased segmentation of genomic information. This segmentation has allowed for permutations of sequences in an RNA context and the development of increasingly complex RNA processing mechanism(s) to produce permuted transcripts, as demonstrated by RNA splicing and trans-splicing. The segmentation of information in a DNA context and mechanisms to permute them in RNA space are potential areas of active selection. The possible use of multiple precursor transcripts and the ability to permute exon combinations found within them to form mature chimeric transcripts would have the advantage of increasing the informational content of genomes dramatically and likely prompt an increase in the complexity of the processing machinery. In cases of a single primary transcript, this increase in complexity can be expressed by the formula in Box 1 and illustrated in Figure 4A. However, in the case of two or more primary transcripts contributing to a mature processed RNA in a non-collinear and permuted fashion, the total number of the number of possible permutated transcripts can be expressed as seen in formula 2 in Box 1, illustrated Figure 4B and extrapolated seen in the plot depicted in Figure 4C

Box 1. Potential diversity as a consequence of non-collinearity transcripts [Au: OK?].

The total number of possible collinear combinations can be expressed as

where L represents the total number of possible exons in the primary transcript, while m is the number of exons that are found in the mature transcript. Thus, from a single primary transcript containing possible 4 exons, (L = 4) the number of mature transcripts that have 2 exons is 6 (Figure 4A). If all possible collinear transcripts were to be made containing 1–4 exons, there would be a total of 15 possible transcripts that could be made, or, generally:

If two or more primary transcripts contribute to a mature processed RNA in a non-collinear and permuted fashion, the total number of the number of possible permutated transcripts can be expressed as [Au: OK?]

where L again represents the total number of exons and m represents the number of exons in the mature transcripts. Thus, if two primary transcripts possessing 2 and 3 exons (L = 5) are used to create a 3-exon mature transcript (m = 3), a total of 60 permuted transcripts can be made (Figure 4B). If all transcripts using from 1–5 exons can be made, a total of 325 permuted transcripts could be observed. The dependence of the total number of mature transcripts on the number of possible exons for the non-collinear permuted case diverges exponentially from the collinear case (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Collinear and non-collinear combinations of information modules of information.

(A) Six possible two-exon combinations derived from a four exon genic region are shown. (B) Five of the possible 350 non-collinear, permuted three-exon transcripts that can be made from two 2 and 3 exon containing transcripts are shown. (C) A semi-log plot comparing the number of transcript isoforms that can be created using 1 to 10 exons considering a non-permuted collinear organization of information (blue) or a permuted non-collinear organization of information (black). The dependence of the total number of mature transcripts on the number of possible exons for the non-collinear permuted case diverges exponentially from the collinear case.

Using DNA as a reference for evolutionary studies

The potential utilization of multiple precursor transcripts to form a single mature chimeric RNA product and possibility of permuting the order of the genomic sequences in chimeric transcripts raises two points with evolutionary implications. The first concerns the identification of a complete set of both functional sequence segments and the evolutionarily constrained sequences. Constrained genomic sequences are often identified by the alignment of orthologous sequences using one of several sequence analyses programs 39,40,41,42,43,44. Based on such alignments functionality is often inferred. However, if functional RNA sequence regions can be made from modules of non-collinear sequences that arise by permutation of genomic sequences that are encoded in the DNA short evolutionary constrained or novel functional regions of genomes may be joined together in RNA space, the product of which is not observable by analysis of genomic sequences. Such novel RNA encoded sequences would likely be missed by programs designed to identify constrained sequences in DNA.

A second point is related to the first. It concerns the use of genomic DNA as the sole reference to identify the sequences that manifest the effects of evolutionary pressures. Using DNA as a reference to study evolutionary pressures on sequences naturally stems from its role in inheritance. However, a focus on DNA as the sole subject to catalogue genetically transmitted functional elements and the only molecule to analyze for evolutionary constraints ignores the growing number of acknowledged functional roles that RNA contributes. It also potentially misses the novel RNA encoded sequence elements that are often used to carry out these functions. While the identification of functional regions encoded in a collinear fashion is relatively straightforward for both DNA and RNA, the same can not be said for those functional regions that are created from non-collinear segments. Unless these sequence regions have been catalogued previously (e.g. SL1 and SL2 transcripts in C. elegans) or the rules of how distal non-collinear sequences are to be joined in a transcript are known, then analyses of the transcriptome in addition to an organism’s genome may be required to catalogue all of the functional regions subject to selection.

Interpreting genetic variation

Genetic variation observed from the single nucleotide to the gross chromosomal rearrangement levels are the basis of evolutionary change. Two biases influence the interpretation of the effects of such genetic variation. The first is that the effect is most often interpreted to be related to the nearest gene annotation. Thus, a variation occurring in an exon of a gene is often interpreted as causing a malfunction of that gene leading to an abnormal phenotype. The second bias is that the effect of the variation is associated in the context of the extended but local genetic locus. If a genetic variation is observed to be proximal but not within an exon of a gene, the effects are most often interpreted to be caused by mis-regulation of a gene located nearby. Such interpretations of genetic variations are common and often well supported. However, current genetic association studies appear to be widening the range of study to include long distance trans effects as is seen with SNPs mapping hundreds of thousands of base pairs associated with urinary bladder and prostate cancers45,46. This is prompted by the recent observation that almost half of all polymorphisms found statistically correlated with complex diseases or traits are located at a non-annotated and distal genomic site (intron or intergenic region) 47. The joining of distal genomic regions by the formation of chimeric RNAs provides additional motivation for this broadening of genetic analyses.

Conclusions

Consideration of the non-collinear organization of genomes raises several questions. The first of these questions is why genomes resort to a non-collinear organizational strategy of stored information. While it is clear that the relatively straightforward collinear organization of functional information in genome is likely to be utilized as the most common strategy (Figure 1A) it is also true that utilization of a non-collinear organization appeared early in eukaryotic genome evolution as exemplified by worms and trypanosomes. The advantages of using such a complex strategy include providing a means of increasing the information content of genomes (Figure 4C) and allowing for the possible new combinations of exons, operating in a relatively redundant fashion (motif sharing) and in turn functioning in more significant roles (e.g. formationof new spliced mRNAs allowing for increased protein diversity). Additionally, the use of non-collinear organization leading to the formation of chimeric RNAs might also allow for the real-time monitoring of transcripts of co-regulated RNAs. Such a function would lead to the prediction, which remains to be tested, that chimeric RNAs would be formed from genes that possessed similar expression profiles observed over development or in response to some external stimuli.

A second question concerns the observed relatively low level expression of chimeric transcripts as illustrated by the infrequent reports from the many cDNA library studies concerning their existence. Is this because chimeric RNAs are rarely used by cells or because they are non-functional transcription and comprise a general RNA processing background? The answer to this question is unclear at the moment. The lack of multiple reports of biologically functional chimeric RNAs in additional organisms other than the worm, trypanosomes and a few examples in higher eukaryotes may stem from either the fact they have often been observed in cDNA studies but discarded because of the prevalent genome organizational models or that they are not observed owing to either the shallow depth of sampling of the transcriptome or the method of analyses (e.g. arrays).

It would seem that the non-collinear organization of information in genomes is used more routinely than previously thought. This strategy is seen in organisms in which trans-splicing is integral (lower eukaryotes) and in higher eukaryotes in which their presence is observed but the importance of which is as yet unclear. While the strategic and evolutionary advantages of this organization of information are interesting there are many questions that remain. As with the ongoing discussions concerning the functional importance of the prevalence of non-protein coding transcription, only additional experiments will lead to answers to these questions.

Acknowledgments

Work in my laboratory is supported by NHGRI (U54 HG004557 and U01 HG004271). Thanks to P. Kapranov for discussions and long term collaboration, H. Sussman for helpful discussions and editing of the manuscript and A. Dobin for assistance in deriving the computational expressions to determine the collinear and non-collinear permutations and the plot depicted in Figure 4C.

References

- 1.Consortium EP, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. Summary of ENCODE analyses to identify fucntional regions in 1% of the human genome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celniker SE, et al. Unlocking the secrets of the genome. Nature. 2009;459:927–930. doi: 10.1038/459927a. 459927a [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carninci P, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 2005;309:1559–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1112014. 309/5740/1559 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones PA, Archer TK, Baylin SB, Beck S, Berger S, Bernstein BE, Carpten JD, Clark SJ, Costello JF, Doerg RE, Esteller ME, Feinberg AP, Gingeras TR, Greally JM, Henikoff S, Herman JG, Jackson-Grusby L, Jenuwein T, Jirtle RL, Kim Y-J, Laird PW, Lim B, Martienssen R, Polyak K, Stunnenberg H, Tlsty TD, Tycko B, Ushijima T, Zhu J, Pirrotta V, Allis CD, Elgin S, Jones PA, Rine J, Wu C. Moving AHEAD with an international human epigenome project. Nature. 2008;454:711–715. doi: 10.1038/454711a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. nrg2521 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.006. S0092-8674(09)00142-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hert DG, Fredlake CP, Barron AE. Advantages and limitations of next-generation sequencing technologies: a comparison of electrophoresis and non-electrophoresis methods. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:4618–4626. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramadan N, Flockhart I, Booker M, Perrimon N, Mathey-Prevot B. Design and implementation of high-throughput RNAi screens in cultured Drosophila cells. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2245–2264. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.250. nprot.2007.250 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amaral PP, Mattick JS. Noncoding RNA in development. Mamm Genome. 2008;19:454–492. doi: 10.1007/s00335-008-9136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR, Mehler MF. RNA regulation of epigenetic processes. Bioessays. 2009;31:51–59. doi: 10.1002/bies.080099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper TA, Wan L, Dreyfuss G. RNA and disease. Cell. 2009;136:777–793. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.011. S0092-8674(09)00148-2 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashe A, Whitelaw E. Another role for RNA: a messenger across generations. Trends Genet. 2007;23:8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.11.008. S0168-9525(06)00378-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton RE, Boothroyd JC. Evidence for trans splicing in trypanosomes. Cell. 1986;47:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90617-3. 0092-8674(86)90617-3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause M, Hirsh D. A trans-spliced leader sequence on actin mRNA in C. elegans. Cell. 1987;49:753–761. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90613-1. 0092-8674(87)90613-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tessier LH, et al. Short leader sequences may be transferred from small RNAs to pre-mature mRNAs by trans-splicing in Euglena. EMBO J. 1991;10:2621–2625. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07804.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajkovic A, Davis RE, Simonsen JN, Rottman FM. A spliced leader is present on a subset of mRNAs from the human parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:8879–8883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis RE, et al. RNA trans-splicing in Fasciola hepatica. Identification of a spliced leader (SL) RNA and SL sequences on mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20026–20030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Zhao L, Jiang H, Wang W. Short homologous sequences are strongly associated with the generation of chimeric RNAs in eukaryotes. J Mol Evol. 2009;68:56–65. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9187-0. Computational analyses of human, mouse and fly RNA databases to identify the presence of chimeric RNAs and the identification of short repeat sequences located a the junction sites forming the chimeric transcripts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Wang J, Mor G, Sklar J. A neoplastic gene fusion mimics trans-splicing of RNAs in normal human cells. Science. 2008;321:1357–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1156725. 321/5894/1357 [pii] Identification of chimeric RNA and protein made from JAZF1 and JJAZ1 genes in normal and transformed endometiral cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eychene A, Rocques N, Pouponnot C. A new MAFia in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:683–693. doi: 10.1038/nrc2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rickman DS, et al. SLC45A3-ELK4 is a novel and frequent erythroblast transformation-specific fusion transcript in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2734–2738. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4926. 0008-5472.CAN-08-4926 [pii] Identification of chimeric RNA made from SLC45A3-ELK4 genes in normal and transformed prostate cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janz S, Potter M, Rabkin CS. Lymphoma- and leukemia-associated chromosomal translocations in healthy individuals. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;36:211–223. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maher CA, et al. Transcriptome sequencing to detect gene fusions in cancer. Nature. 2009;458:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07638. nature07638 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denoeud F, et al. Prominent use of distal 5′ transcription start sites and discovery of a large number of additional exons in ENCODE regions. Genome Res. 2007;17:746–759. doi: 10.1101/gr.5660607. 17/6/746 [pii] Identification and characterization of chimeric RNAs found in normal tissues and transformed cell lines mapping in the 1% of human genome analyzed by the ENCODE studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djebali S, et al. Efficient targeted transcript discovery via array-based normalization of RACE libraries. Nat Methods. 2008;5:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1216. nmeth.1216 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parra G, et al. Tandem chimerism as a means to increase protein complexity in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:37–44. doi: 10.1101/gr.4145906. gr.4145906 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapranov P, et al. Examples of the complex architecture of the human transcriptome revealed by RACE and high-density tiling arrays. Genome Res. 2005;15:987–997. doi: 10.1101/gr.3455305. 15/7/987 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruzik JP, Maniatis T. Spliced leader RNAs from lower eukaryotes are trans-spliced in mammalian cells. Nature. 1992;360:692–695. doi: 10.1038/360692a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruzik JP, Maniatis T. Enhancer-dependent interaction between 5′ and 3′ splice sites in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7056–7059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coffin JM. Structure, replication, and recombination of retrovirus genomes: some unifying hypotheses. J Gen Virol. 1979;42:1–26. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-42-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hastings KE. SL trans-splicing: easy come or easy go? Trends Genet. 2005;21:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.02.005. S0168-9525(05)00045-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson DA, Hassan AB, Errington RJ, Cook PR. Visualization of focal sites of transcription within human nuclei. EMBO J. 1993;12:1059–1065. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05747.x. First description of nuclear sub-compartments in which RNA transcription occurs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell JA, Fraser P. Transcription factories are nuclear subcompartments that remain in the absence of transcription. Genes Dev. 2008;22:20–25. doi: 10.1101/gad.454008. 22/1/20 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pombo A, Cook PR. The localization of sites containing nascent RNA and splicing factors. Exp Cell Res. 1996;229:201–203. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0360. S0014-4827(96)90360-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pombo A, et al. Regional and temporal specialization in the nucleus: a transcriptionally-active nuclear domain rich in PTF, Oct1 and PIKA antigens associates with specific chromosomes early in the cell cycle. EMBO J. 1998;17:1768–1778. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carter DR, Eskiw C, Cook PR. Transcription factories. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:585–589. doi: 10.1042/BST0360585. BST0360585 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osborne CS, et al. Myc dynamically and preferentially relocates to a transcription factory occupied by Igh. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050192. 06-PLBI-RA-2184 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dostie J, Zhan Y, Dekker J. Chromosome conformation capture carbon copy technology. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2007;Chapter 21(Unit 21):14. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2114s80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Margulies EH, Program NCS, Green ED. Detecting highly conserved regions of the human genome by multispecies sequence comparisons. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2003;68:255–263. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2003.68.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Margulies EH, et al. An initial strategy for the systematic identification of functional elements in the human genome by low-redundancy comparative sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4795–4800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409882102. 0409882102 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Margulies EH, et al. Analyses of deep mammalian sequence alignments and constraint predictions for 1% of the human genome. Genome Res. 2007;17:760–774. doi: 10.1101/gr.6034307. 17/6/760 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brudno M, et al. LAGAN and Multi-LAGAN: efficient tools for large-scale multiple alignment of genomic DNA. Genome Res. 2003;13:721–731. doi: 10.1101/gr.926603. doi:10.1101/gr.926603 GR-9266R [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper GM, et al. Characterization of evolutionary rates and constraints in three Mammalian genomes. Genome Res. 2004;14:539–548. doi: 10.1101/gr.2034704. doi:10.1101/gr.203470414/4/539 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siepel A, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. gr.3715005 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiemeney LA, et al. Sequence variant on 8q24 confers susceptibility to urinary bladder cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1307–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.229. ng.229 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeager M, et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies a second risk locus at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39:645–649. doi: 10.1038/ng2022. ng2022 [pii. Identificaiton of SNP containing loci mapping to intergenic regions hundreds of thousands of nucleotides upstream from MYC gene with statistically strong association in uriniary bladder cancer cases. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008;322:881–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1156409. 322/5903/881 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]