Abstract

The oversupply of calories and sedentary lifestyle has resulted in a rapid increase of diabetes prevalence worldwide. During the past two decades, lines of evidence suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a key role in the pathophysiology of diabetes. Mitochondria are vital to most of the eukaryotic cells as they provide energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate by oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, mitochondrial function is an integral part of glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β‐cells. In the present article, we will briefly review the major functions of mitochondria in regard to energy metabolism, and discuss the genetic and environmental factors causing mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes. In addition, the pathophysiological role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance and β‐cell dysfunction are discussed. We argue that mitochondrial dysfunction could be the central defect causing the abnormal glucose metabolism in the diabetic state. A deeper understanding of the role of mitochondria in diabetes will provide us with novel insights in the pathophysiology of diabetes. (J Diabetes Invest, doi: 10.1111/j.2040‐1124.2010.00047.x, 2010)

Keywords: Insulin resistance, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

The global figure of people affected by type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is estimated to be 220 million in 2010 and 350 million in 20251. In Asian countries, where urbanization is rapidly spreading, the incidence of diabetes has reached an epidemic level2. This steep increase in diabetes is associated with an increased prevalence of diabetic complications, such as end‐stage renal disease, cardiovascular disease and stroke. Consequently, the socioeconomic burden of the diabetes epidemic is substantial3. It is of major concern to better understand the pathogenesis of diabetes and develop new curative and preventive strategies.

Mitochondria are important for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, which is vital for all living organisms. Mitochondria are also the key regulator of glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion in the pancreatic β‐cells4. During the past two decades, a growing body of evidence has shown that mitochondrial function is closely related to various facets of diabetes – pancreatic β‐cell dysfunction, insulin resistance, obesity and vascular complications of diabetes. In the present article, we briefly review the mitochondrial metabolism and focus on the etiologies of mitochondrial dysfunction and its impact on T2DM.

Mitochondrial Metabolism: Brief Overview

Genome and Structure of Mitochondria

Mitochondrion is an intracellular organelle present in most of the eukaryotic cells. One eukaryotic cell contains hundreds of mitochondria5. It is assumed that mitochondria were first introduced to proto‐eukaryotic cells by the endosymbiosis of bacteria about 2–3 billion years ago6. As endosymbiosis matured, mitochondria transferred most of their genes to the nucleus. Following are some characteristics of mitochondria that might help to understand their role in the pathophysiology of diabetes.

Mitochondria have their own DNA and several copies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) are present per mitochondrion5. The mtDNA is a circular DNA with 16,569 base pairs7. It encodes 37 genes. Thirteen genes are coding for proteins of the electron transport chains and the rest are coding for the two rRNA and the 22 tRNA. In contrast, the majority of proteins regulating mitochondrial structure, metabolic function and biogenesis are encoded by the nuclear DNA (nDNA). For example, the transcription and replication of mtDNA is regulated by the mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), which is encoded by the nDNA8. There is complex interplay between the nucleus and the mitochondria to ensure proper functioning of the mitochondria.

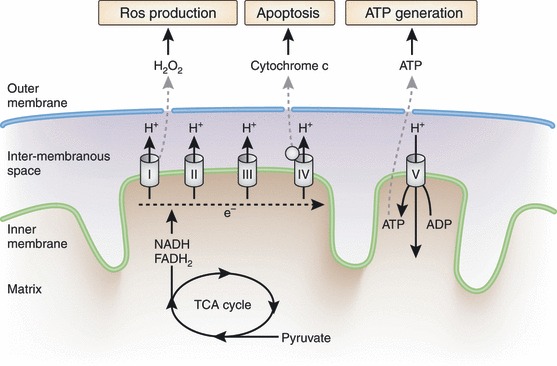

A mitochondrion is structurally divided into four compartments: (i) the outer membrane, which is capable of freely transporting ions and small molecules; (ii) the intermembranous space, where protons are accumulated and generate an electrochemical gradient; (iii) the inner membrane, which allows the transport of otherwise impermeable adenosine diphosphate (ADP), phosphate and ATP, and anchors subunit complexes of the electron transport chains; and (iv) the matrix where oxidation of pyruvate and fatty acids occur (Figure 1). The inner membrane has numerous invaginations called the cristae, which gives mitochondria its characteristic morphology. By increasing the surface area, mitochondria can increase the ATP generating capacity.

Figure 1.

Major functions of mitochondria. The three major functions of mitochondria in regard to energy metabolism include: (i) adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production; (ii) generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS); and (iii) apoptosis. The NADH and FADH2, which are reducing equivalents yielded from the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, transfer the electrons to the electron transport chain through complex I and complex II, respectively. As the electrons are transported to complex III and IV, the protons are accumulated in the intermembranous space generating the electrochemical gradient. Complex V uses the proton gradient as the driving force to generate ATP. During the process of electron transport, some of the electrons can be leaked and transferred to O2, which results in ROS generation. When the cellular ATP is depleted or in excess of ROS, mitochondrial proteins such as cytochrome c, caspases and apoptosis initiating factors are released to cytosol and initiate the process of apoptosis. ADP, adenosine diphosphate. [Figure replaced after online publication date July 21, 2010]

Mitochondria can change their number, size and activity within a cell through dynamic alteration of biogenesis, fusion and fission9. The master switch of mitochondrial biogenesis is the peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ coactivator (PGC)‐1α and PGC‐1β10. These are transcriptional coactivators, which activate a number of oxidative phosphorylation genes and TFAM through nuclear respiratory factor (NRF)‐111. PGC‐1α regulates various aspects of mitochondrial function including biogenesis, adaptive thermogenesis, fatty acid oxidation and peripheral tissue glucose uptake12. Finally, it has been recently suggested that maintenance of mitochondrial function and repair depends on mitochondrial remodeling; that is, fusion, fission and autophagy13. These unique characteristics in structure and genome allow mitochondria to play a complex action in energy metabolism as well as cell fate determination.

Major Functions of Mitochondria

Adenosine triphosphate production through oxidative phosphorylation, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and regulation of apoptosis are the main functions of mitochondria relevant to the pathogenesis of diabetes (Figure 1). Glucose is metabolized by glycolysis to pyruvate and enters mitochondria to undergo a further metabolic pathway of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. In contrast, fatty acids enter the mitochondria through carnitine‐palmitoyltransferase (CPT)‐1 and go through β‐oxidation to make acetyl coenzyme A, which are further metabolized in the TCA cycle. The TCA cycle and β‐oxidation yield reducing equivalents, such as NADH and FADH214. The electrons from NADH and FADH2 enter the electron transport chain through complex I and complex II, respectively. From these two complexes, electrons are transported sequentially to complex III through the coenzyme Q and then to complex IV through cytochrome c. As the electrons are transported, the free energy released is used to pump the protons into the intermembranous space. The proton gradient formed across the inner membrane creates the electrochemical gradient, which acts as the driving force of ATP generation in complex V (ATP synthase)14.

Aside from ATP production, mitochondria are the major source of endogenous ROS. When electron transport is impaired in the electron transport chain, it can be transferred to O2 and generates superoxide. Complex I of the electron transport chain is the predominant site of donating electrons to O2 and producing superoxide (O2–)15,16. Superoxide is processed to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by either superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) or 2 (SOD2). The decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water is carried out by glutathione peroxidase (GPX)‐1. However, in the presence of free irons or copper ions, such as in the case of mitochondria, hydrogen peroxide can be transformed to highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH–)15. When calorie intake is in excess or the capacity of oxidative phosphorylation is limited, the electron transport is impaired in the electron transport chain and has higher chance of being converted to ROS. These ROS can damage proteins, lipids and mtDNA of mitochondria and further increase the production of ROS. The mtDNA has no introns and has a poorly equipped repair mechanism, rendering it susceptible to oxidative damage and mutations. The mtDNA mutations accumulate with age, and these mutations might play an important role in the process of senescence and diabetes6,17.

Mitochondria are also the prime regulators of apoptosis6. When confronted with cellular stress, mitochondria open the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mtPTP)18. Opening of the mtPTP allows the release of mitochondrial proteins, such as cytochrome c, caspases and apoptosis initiating factor (AIF), to induce apoptosis. Oversupply of calories or physical inactivity can impair the transfer of electrons through the electron transport chain, leading to increased production of ROS and consequent apoptosis in various cells and tissues6.

Etiological Factors of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Diabetes

It was only recently that mitochondrial dysfunction was shown to be an etiological factor of diabetes. In the early 1990s, a specific mutation in mtDNA was identified to be causally related to the maternally inherited form of diabetes19,20. A few years later, our group reported that the peripheral mtDNA copy number was decreased in subjects with T2DM even before the onset of disease21. Shulman et al. also have shown that oxidative phosphorylation was decreased in insulin resistant offspring of T2DM patients22. In this section, we will discuss the etiological factors of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes.

Genetic Factors

mtDNA Mutations

There are more than 20 mtDNA mutations that are associated with diabetes. Among these, the most frequently encountered mtDNA mutation is the A to G replacement at position 3243 (A3243G), which encodes the leucyl‐tRNAUUR23. The frequency of this mutation in diabetes patients is approximately 1%24–26. In Koreans, the prevalence of this mutation in diabetes patients was reported to be 0.5%27,28. However, in patients with atypical type 1 diabetes mellitus, who showed insulin deficiency after glucagon stimulation, but had an insulin free period for more than 1 year after diagnosis, the prevalence of this mutation increased to 10%28. This mutation can either present as maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD)29 or mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke‐like episodes (MELAS) syndrome30. A recent investigation in a French population reported that the proportion of the mutant mtDNA (heteroplasmy) is associated with age at diagnosis and increased HbA1c level in MIDD patients31. The mechanism that links this mutation with the pathogenesis of diabetes is not quite evident yet. Most, but not all, of the studies point out that β‐cell dysfunction and impaired insulin secretion is more prominent than the insulin resistance in these patients32. It has been shown that A3243G mutation results in decreased oxygen consumption and ATP generation33 in the cybrid system, where the function of mitochondria carrying mutant mtDNA was studied in a neutral nuclear genomic background34.

Nuclear DNA Mutations

Maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a specific subtype of monogenic diabetes that develops as a result of nDNA mutations associated with defects of β‐cell function. It is classified into six subtypes according to the genetic defect it harbors. All the subtypes of MODY show impairment of insulin secretory function with autosomal dominant inheritance, and onset at adolescence or early adulthood35. Among these, MODY1, MODY3 and MODY4 are suggested to be closely related to mitochondrial dysfunction. HNF‐4α, the gene mutated in MODY1, is a transcription factor of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily and plays a role in hepatocyte differentiation36. It has been shown that genetic alteration of HNF‐4α could result in decreased mitochondrial function, such as reduced pyruvate oxidation, decreased ATP generation and blunted glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β‐cells37. HNF‐4α has a close interaction with HNF‐1α, which is involved in MODY338. Mutations in the HNF‐1α gene also showed defective glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion, which was explained by decreased ATP generation and increased uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation39. Mutations in IPF‐1 cause MODY4. Recently, it was reported that a deficiency in IPF‐1 resulted in mitochondrial dysfunction by downregulating the expression of TFAM in β‐cells40. All of these examples highlight the contribution of nDNA mutations to mitochondrial function and pathophysiology of diabetes.

Common Genetic Variations That Alter Mitochondrial Function

T2DM is considered to be a polygenic disorder, meaning that multiple genes and environmental factors are in complex interplay. In an effort to find the relationship between mitochondrial function and diabetes, we recently reported that mtDNA 16189 T>C variant and some mtDNA haplogroups are associated with T2DM41–43. The mtDNA 16189 T>C variation lies in the control region of mtDNA transcription and replication44. We have shown that 16189C variation is associated with an increased risk of T2DM in meta‐analysis of data from five Asian countries, including Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong and China43. However, this association was not replicated in Europeans45. This could be attributed to the difference in the frequency of this variation in Asians (31.0%) and Europeans (9.2%) or ethnic difference in the nuclear or mitochondrial genetic background, such as the mitochondrial haplogroup.

The mtDNA haplogroups are geographic region specific variations thought to originate from adaptation to famine and cold46. We studied the association of 10 major mtDNA haplogroups with T2DM in large samples of Koreans and Japanese41. We noticed that haplogroup N9a was associated with a decreased risk of T2DM in both Korean and Japanese populations. In addition, haplogroup D5 and F were marginally associated with susceptibility to T2DM. Although the functional characteristics of the N9a haplogroup are largely unknown, it is postulated that it might be associated with an uncoupling phenotype, where ATP generated from the electron transport chain is used for increased heat production41.

Aside from the variations of the mtDNA, lines of evidence suggest that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in nuclear genes related to mitochondrial function are associated with T2DM. Among the 18 genes that have been shown to have a robust association with T2DM in recent large scale association studies or genome‐wide association studies47, at least two genes seem to have a close relationship with mitochondrial dysfunction48,49. These are WFS‐1 and HNF‐1β. WFS‐1 is known to be mutated in Wolfram syndrome, which is a rare autosomal recessive disorder exhibiting diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy and deafness50. WFS‐1 encodes a transmembrane protein that is localized to endoplasmic reticulum and might affect mitochondrial function through regulating calcium influx51. HNF‐1β might control mitochondrial function in a similar manner to HNF‐1α. However, it is not clear whether or how these polymorphisms alter mitochondrial function and confer risk of T2DM.

Environmental Factors Altering Mitochondrial Function

Obesity

Industrialization and westernization have dramatically changed the Korean lifestyle. Koreans are constantly deprived of physical activity and oversupplied with calories. These have led to an explosion of the obesity epidemic worldwide. It is now well‐known that chronic aerobic exercise increases mitochondrial content in muscle, thereby increasing the ATP generating capacity52. On the contrary, chronic disuse of muscle decreases mitochondrial content and oxidative capacity leading to impaired glucose utilization53. In regard to energy intake, a chronic high fat diet leads to insulin resistance. In a recent report, it has been shown that a high fat diet leads to insulin resistance in rodents and humans mainly by increasing mitochondrial H2O2 generation54. Blocking H2O2 emission from mitochondria by targeting antioxidants to mitochondria or overexpressing catalase resulted in a marked reduction of insulin resistance in the high fat diet‐fed state54.

Intrauterine Malnutrition

Another environmental factor suggested to be linked with mitochondrial dysfunction is intrauterine malnutrition. Poor nutritional status at the fetal and infant stage can permanently alter glucose‐insulin metabolism and increase susceptibility to T2DM. This ‘thrifty phenotype’ hypothesis was first proposed by Hales and Barker55. Since then, our group has investigated the role of mitochondria dysfunction as the link between protein malnutrition and T2DM56. We reported that liver and skeletal muscle mtDNA content was decreased in fetal and early postnatal malnourished rats, even when proper nutrition was supplied after weaning57. In addition, we found that protein malnutrition during fetal life resulted in decreased pancreatic β‐cell mtDNA content, impaired β‐cell development and impaired insulin secretion58. The mechanism of decreased mtDNA content during fetal malnutrition is not well understood. However, low taurine levels, low levels of methyl‐donors, depletion of the nucleotide pool, and increased ROS might be the contributing factors of poor mitochondrial function56.

Environmental Pollutants

In a certain sense, environmental pollutants, such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are the true environmental factor causing mitochondrial dysfunction leading to T2DM. POPs are organic compounds with characteristics of long‐term persistence in the environment and bioaccumulation through the food chain59. The hypothesis that POPs could be the causative agent of the increasing epidemic of T2DM stemmed from the finding that serum γ‐glutamyltransferase (GGT) activity is associated with T2DM, even within the normal range60. It has been shown that exposure to xenobiotics, including POPs, can increase the activity of GGT61. The most notable finding was derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANEs) dataset. By measuring the serum concentration of POPs, it was shown that there was a strong dose‐response relationship between the prevalence of T2DM and the concentration of POPs62. Because most of the POPs are well known for their ability to inhibit mitochondrial oxidative capacity, it is suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction might be mediating these effects63. In accordance with this hypothesis, we have recently shown in an animal study that chronic exposure to the herbicide, atrazine, causes mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance64. A recent report also showed that dioxin caused depletion of mtDNA along with mitochondrial dysfunction65.

Pathophysiological Roles of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in T2DM

As described above, mitochondria play a key role in skeletal muscle oxidative phosphorylation and β‐cell insulin secretion. In this section, we will discuss the pathophysiological mechanism(s) of how mitochondrial dysfunction is related to insulin resistance and β‐cell dysfunction.

Insulin Resistance

Decreased mtDNA Copy Number

From the late 1990s, our group has claimed that mitochondrial dysfunction is a causative factor of insulin resistance in T2DM. To prove this hypothesis, we studied the association of peripheral blood cell mtDNA copy number with risk of T2DM and various metabolic phenotypes. In a population‐based prospective cohort, we found that mtDNA copy number in peripheral blood leukocytes was significantly decreased in subjects who were converted to T2DM during a 2‐year follow‐up period21. In another cohort, we found that mtDNA copy number was also significantly associated with insulin sensitivity in non‐diabetic offspring of T2DM patients66. Furthermore, we found that the mtDNA copy number was inversely associated with waist‐to‐hip circumference ratio, blood pressure and fasting glucose21. Unfortunately, these findings were not always replicated in different populations67,68. One of the main critiques to our findings was that mtDNA copy number in peripheral blood cells might not reflect the mitochondrial function in insulin target cells.

Decreased Oxidative Phosphorylation

Shulman et al. proved a similar hypothesis using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies22,69. First, they showed that an age‐related decline in insulin sensitivity was associated with a 40% reduction in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, and increased intramyocellular and intrahepatic fat accumulation69. Then, similar methods were used to compare the insulin sensitivity of muscle and liver in the insulin‐resistant offspring of T2DM patients compared with insulin sensitive controls22. There was an approximately 60% decrease in insulin‐stimulated glucose uptake in the muscle of insulin resistant subjects. This was associated with an 80% increase in intramyocellular fat content. Most importantly, there was an approximately 30% decrease in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the insulin resistant subjects22. These data strongly suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction could be an important mechanism of the insulin resistance in these subjects. Their findings were concordant with our previous report showing skeletal muscle lipolysis was decreased in high fat‐fed mouse models70,71. Further supporting evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction is the cause of insulin resistance came from transcriptional profiling studies72,73. By using microarray gene expression chips, it was reported that genes involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation were coordinately down regulated in T2DM as a result of decreased PGC‐1α expression72,73.

Molecules Linking Mitochondrial Dysfunction to Insulin Resistance

Derivatives of fat, such as long‐chain acyl‐CoA (LCAC), diacylglycerols (DAG) and ceramides, mediate mitochondrial dysfunction to insulin resistance. Decreased mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation increases cytosolic LCAC, a potent inhibitor of glycogen synthase and hexokinase, and leads to insulin resistance71. In addition, the increased LCAC is diverted to diacylglycerols and ceramides, which are well‐known for their ability to increase insulin resistance74,75.

In a diabetes‐prone obese rat model, we reported that AMPK was significantly decreased compared with normal controls76. AMPK is a cellular energy gauge that senses the AMP/ATP ratio77. Its activation inhibits acetyl‐CoA carboxylase78, therefore decreasing fatty acid synthesis in the liver and increasing fatty acid oxidation in the muscle. Interestingly, AMPK can increase the expression of PGC‐1α and the consequent pathway of mitochondrial biogenesis79, 80. In contrast to obesity, physical activity and calorie restriction increase AMPK level and PGC‐1α, leading to enhanced insulin sensitivity. Recently, mitofusin protein (MFN)‐2 has been shown to mediate the role of PGC‐1α on mitochondrial biogenesis81. MFN‐2 is a mitochondrial membrane protein involved in mitochondrial membrane fusion and metabolism82. The role of mitochondrial fusion and fission in the genesis of insulin resistance awaits future research.

Finally, it should be pointed out that several recent studies raised a new possibility that mitochondrial dysfunction is a consequence of insulin resistance, rather than a cause83–86. Further research is required to clarify the cause‐and‐effect relationship between insulin resistance and mitochondrial function.

Pancreatic β‐cell Dysfunction

Mitochondria and Insulin Secretion

Patients with diabetes who have mutations in mtDNA or mitochondria related nuclear DNA, largely show impaired pancreatic β‐cell insulin secretory function. This is because ATP generated from mitochondria is the key factor that couples the blood glucose level with insulin secretion. When blood glucose enters the pancreatic β‐cell, increased ATP/ADP ratio depolarizes the plasma membrane by closing the ATP‐sensitive K channel87. This leads to a calcium influx by the opening of the voltage‐sensitive calcium channel87. Increased calcium concentration stimulates the fusion of insulin containing granules with the plasma membrane and consequently leads to insulin secretion88. A defective mitochondrial function in any of the above processes can lead to impaired insulin secretion and T2DM.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction in β‐cell Failure

Obesity and insulin resistance are well‐known predispositions to T2DM. However, not all obese, insulin resistant subjects progress to T2DM. The decrease in β‐cell mass and function, known as β‐cell failure, is thought to be the triggering factor of this transition. Lines of evidence show that mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with β‐cell failure89. In our previous study, we showed that in obese diabetes‐prone rats, pancreatic β‐cell mass is increased at an early age, but then progressively decreased90. Isolated islets from cadaveric donors with T2DM showed that individual islets were smaller and contained a reduced proportion of β‐cells91. In addition, changes in mitochondrial morphology and function in human islets of T2DM, that is, swelling of mitochondria, decreased ATP level and increased uncoupling protein 2 expression92, suggest the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of β‐cell failure in T2DM.

Mitochondrial Fusion, Fission and Autophagy

A recent line of evidence highlighted the importance of mitochondria remodeling, that is, fusion, fission and autophagy, in β‐cells. Through fusion, intact mitochondria can share solutes, metabolites, mtDNA and electrochemical gradients with damaged mitochondria82. The fission event often yields mitochondria with decreased membrane potential and reduced possibility of fusion93. Fusion and fission cycling is thought to be a process of segregating dysfunctional mitochondrial and rendering it for autophagy93. In mice, β‐cell specific deletion of an autophagy related gene (Atg7) resulted in decreased insulin secretion with mitochondrial abnormalities94. Together, fusion, fission and autophagy seem to be an integral part of maintaining homeostasis of β‐cell mitochondrial function in T2DM.

Mitochondria as a Therapeutic Target for T2DM

Considering the potential role of mitochondrial function in the pathophysiology of diabetes, it would be of prime interest to increase mitochondrial function in order to prevent or treat diabetes. One of the most extensively proven methods is restricting calories. Calorie restriction is well known to reverse and prevent insulin resistance. SIRT, which are a family of NAD+‐dependent deacetylases, play a central role in mediating the effect of calorie restriction on mitochondrial function95. In pancreatic β‐cells, SIRT1 stimulates insulin secretion and provides defense from oxidative stress96,97. SIRT1 activates PGC‐1α in muscle and liver to increase mitochondrial biogenesis98. It has also been reported that small molecules activating SIRT were able to increase insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function, mimicking the effects of calorie restriction99,100.

One of the drugs that improves mitochondrial function is thiazolidinedione (TZD), currently used as an antidiabetic drug. TZD was shown to increase mitochondrial biogenesis101. However, there are debates regarding the effect of TZD on mitochondrial function102. We have recently studied another interesting drug, alpha‐lipoic acid (ALA), which is an essential cofactor of mitochondrial substrates and an anti‐oxidant, in diabetes and related metabolic disorders103. In the diabetes prone obese rat, ALA prevented the development of diabetes103, vascular dysfunction104 and hepatic steatosis by increasing AMPK activity105. In addition, we found that ALA reduces food intake and increases energy expenditure by suppressing hypothalamic AMPK activity106. As more and more interest is being focused on the role of mitochondria in diabetes, it seems likely that new therapeutic agents targeting mitochondrial function will emerge in a timely manner.

Conclusion

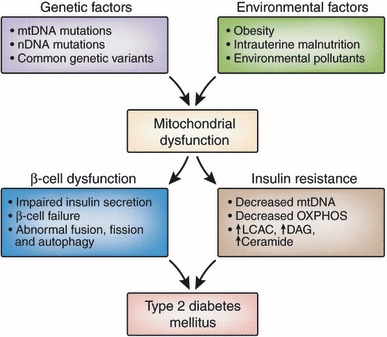

To summarize, we have reviewed the roles of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of diabetes (Figure 2). ATP production, ROS generation and apoptosis are the three main functions of mitochondria. We discussed genetic and environmental factors causing mitochondrial dysfunction and pathophysiological role of mitochondrial dysfunction in T2DM in regard to insulin resistance and β‐cell dysfunction. Although there is a growing body of evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction lies at the center of the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and T2DM, a causal relationship should be clarified by future studies. We hope that unraveling the roles of the mitochondria in diabetes will eventually lead us to discover new strategies to prevent and cure diabetes.

Figure 2.

Relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Various genetic and environmental factors can cause mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a culprit defect that leads to type 2 diabetes by affecting β‐cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. DAG, diacylglycerols; LCAC, long‐chain acyl‐CoA; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation. [Figure replaced after online publication date July 21, 2010]

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by MIC & IITA through the IT Leading R & D Support Project. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature 2001; 414: 782–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoon KH, Lee JH, Kim JW, et al. Epidemic obesity and type 2 diabetes in Asia. Lancet 2006; 368: 1681–1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association . Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 596–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiederkehr A, Wollheim CB. Minireview: implication of mitochondria in insulin secretion and action. Endocrinology 2006; 147: 2643–2649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial diseases in man and mouse. Science 1999; 283: 1482–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet 2005; 39: 359–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 1981; 290: 457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsson NG, Wang J, Wilhelmsson H, et al. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat Genet 1998; 18: 231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman SB, Pineda FJ, Hardwick JM. Mitochondrial fission and fusion dynamics: the long and short of it. Cell Death Differ 2008; 15: 1147–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finck BN, Kelly DP. PGC‐1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J Clin Invest 2006; 116: 615–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly DP, Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Genes Dev 2004; 18: 357–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canto C, Auwerx J. PGC‐1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol 2009; 20: 98–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wikstrom JD, Twig G, Shirihai OS. What can mitochondrial heterogeneity tell us about mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy? Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009; 41: 1914–1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saraste M. Oxidative phosphorylation at the fin de siecle. Science 1999; 283: 1488–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raha S, Robinson BH. Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and ageing. Trends Biochem Sci 2000; 25: 502–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J 2009; 417: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greaves LC, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and ageing. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 1790: 1015–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kokoszka JE, Waymire KG, Levy SE, et al. The ADP/ATP translocator is not essential for the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Nature 2004; 427: 461–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballinger SW, Shoffner JM, Hedaya EV, et al. Maternally transmitted diabetes and deafness associated with a 10.4 kb mitochondrial DNA deletion. Nat Genet 1992; 1: 11–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Den Ouweland JM, Lemkes HH, Ruitenbeek W, et al. Mutation in mitochondrial tRNA(Leu)(UUR) gene in a large pedigree with maternally transmitted type II diabetes mellitus and deafness. Nat Genet 1992; 1: 368–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HK, Song JH, Shin CS, et al. Decreased mitochondrial DNA content in peripheral blood precedes the development of non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1998; 42: 161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, et al. Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin‐resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 664–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maechler P, Wollheim CB. Mitochondrial function in normal and diabetic beta‐cells. Nature 2001; 414: 807–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maassen JA, Jahangir Tafrechi RS, Janssen GM, et al. New insights in the molecular pathogenesis of the maternally inherited diabetes and deafness syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2006; 35: 385–396, x–xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadowaki T, Kadowaki H, Mori Y, et al. A subtype of diabetes mellitus associated with a mutation of mitochondrial DNA. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 962–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy R, Turnbull DM, Walker M, et al. Clinical features, diagnosis and management of maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD) associated with the 3243A>G mitochondrial point mutation. Diabet Med 2008; 25: 383–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SK, Park KS, Shin CS, et al. Mitochondrial DNA point mutations in Korean NIDDM patients. J Korean Diabetes Assoc 1997; 21: 147–155 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee WJ, Lee HW, Palmer JP, et al. Islet cell autoimmunity and mitochondrial DNA mutation in Korean subjects with typical and atypical Type I diabetes. Diabetologia 2001; 44: 2187–2191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Den Ouweland JM, Lemkes HH, Trembath RC, et al. Maternally inherited diabetes and deafness is a distinct subtype of diabetes and associates with a single point mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA(Leu(UUR)) gene. Diabetes 1994; 43: 746–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goto Y, Nonaka I, Horai S. A mutation in the tRNA(Leu)(UUR) gene associated with the MELAS subgroup of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies. Nature 1990; 348: 651–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laloi‐Michelin M, Meas T, Ambonville C, et al. The clinical variability of maternally inherited diabetes and deafness is associated with the degree of heteroplasmy in blood leukocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 3025–3030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maassen JA, Janssen GM, ‘t Hart LM. Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial diabetes (MIDD). Ann Med 2005; 37: 213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Den Ouweland JM, Maechler P, Wollheim CB, et al. Functional and morphological abnormalities of mitochondria harbouring the tRNA(Leu)(UUR) mutation in mitochondrial DNA derived from patients with maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD) and progressive kidney disease. Diabetologia 1999; 42: 485–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King MP, Attardi G. Human cells lacking mtDNA: repopulation with exogenous mitochondria by complementation. Science 1989; 246: 500–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaxillaire M, Froguel P. Genetic basis of maturity‐onset diabetes of the young. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2006; 35: 371–384, x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Ning G, Duncan SA. Mammalian hepatocyte differentiation requires the transcription factor HNF‐4alpha. Genes Dev 2000; 14: 464–474 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Maechler P, Antinozzi PA, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha regulates the expression of pancreatic beta‐cell genes implicated in glucose metabolism and nutrient‐induced insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 35953–35959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boj SF, Parrizas M, Maestro MA, et al. A transcription factor regulatory circuit in differentiated pancreatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 14481–14486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pongratz RL, Kibbey RG, Kirkpatrick CL, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to impaired insulin secretion in INS‐1 cells with dominant‐negative mutations of HNF‐1alpha and in HNF‐1alpha‐deficient islets. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 16808–16821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gauthier BR, Wiederkehr A, Baquie M, et al. PDX1 deficiency causes mitochondrial dysfunction and defective insulin secretion through TFAM suppression. Cell Metab 2009; 10: 110–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuku N, Park KS, Yamada Y, et al. Mitochondrial haplogroup N9a confers resistance against type 2 diabetes in Asians. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 80: 407–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JH, Park KS, Cho YM, et al. The prevalence of the mitochondrial DNA 16189 variant in non‐diabetic Korean adults and its association with higher fasting glucose and body mass index. Diabet Med 2002; 19: 681–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park KS, Chan JC, Chuang LM, et al. A mitochondrial DNA variant at position 16189 is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Asians. Diabetologia 2008; 51: 602–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poulton J, Brown MS, Cooper A, et al. A common mitochondrial DNA variant is associated with insulin resistance in adult life. Diabetologia 1998; 41: 54–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chinnery PF, Elliott HR, Patel S, et al. Role of the mitochondrial DNA 16184‐16193 poly‐C tract in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2005; 366: 1650–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz‐Pesini E, Mishmar D, Brandon M, et al. Effects of purifying and adaptive selection on regional variation in human mtDNA. Science 2004; 303: 223–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prokopenko I, McCarthy MI, Lindgren CM. Type 2 diabetes: new genes, new understanding. Trends Genet 2008; 24: 613–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sandhu MS, Weedon MN, Fawcett KA, et al. Common variants in WFS1 confer risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 951–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winckler W, Weedon MN, Graham RR, et al. Evaluation of common variants in the six known maturity‐onset diabetes of the young (MODY) genes for association with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2007; 56: 685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith CJ, Crock PA, King BR, et al. Phenotype‐genotype correlations in a series of wolfram syndrome families. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 2003–2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeda K, Inoue H, Tanizawa Y, et al. WFS1 (Wolfram syndrome 1) gene product: predominant subcellular localization to endoplasmic reticulum in cultured cells and neuronal expression in rat brain. Hum Mol Genet 2001; 10: 477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hood DA. Mechanisms of exercise‐induced mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2009; 34: 465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wicks KL, Hood DA. Mitochondrial adaptations in denervated muscle: relationship to muscle performance. Am J Physiol 1991; 260: C841–C850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, et al. Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 573–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hales CN, Barker DJ. Type 2 (non‐insulin‐dependent) diabetes mellitus: the thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Diabetologia 1992; 35: 595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee YY, Park KS, Pak YK, et al. The role of mitochondrial DNA in the development of type 2 diabetes caused by fetal malnutrition. J Nutr Biochem 2005; 16: 195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park KS, Kim SK, Kim MS, et al. Fetal and early postnatal protein malnutrition cause long‐term changes in rat liver and muscle mitochondria. J Nutr 2003; 133: 3085–3090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park HK, Jin CJ, Cho YM, et al. Changes of mitochondrial DNA content in the male offspring of protein‐malnourished rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004; 1011: 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher BE. Most unwanted. Environ Health Perspect 1999; 107: A18–A23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee DH, Ha MH, Kim JH, et al. Gamma‐glutamyltransferase and diabetes – a 4 year follow‐up study. Diabetologia 2003; 46: 359–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strange RC, Spiteri MA, Ramachandran S, et al. Glutathione‐S‐transferase family of enzymes. Mutat Res 2001; 482: 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee DH, Jacobs DR Jr. Association between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and gamma glutamyltransferase: results from the National Health and Examination Survey 1999‐2002. Clin Chem 2006; 52: 1825–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pardini RS, Heidker JC, Baker TA, et al. Toxicology of various pesticides and their decomposition products on mitochondrial electron transport. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 1980; 9: 87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lim S, Ahn SY, Song IC, et al. Chronic exposure to the herbicide, atrazine, causes mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e5186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen SC, Liao TL, Wei YH, et al. Endocrine disruptor, dioxin (TCDD)‐induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in human trophoblast‐like JAR cells. Mol Hum Reprod 2010; 16: 361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Song J, Oh JY, Sung YA, et al. Peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA content is related to insulin sensitivity in offspring of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 865–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh R, Hattersley AT, Harries LW. Reduced peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA content is not a risk factor for Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2007; 24: 784–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weng SW, Lin TK, Liou CW, et al. Peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA content and dysregulation of glucose metabolism. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009; 83: 94–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science 2003; 300: 1140–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim CH, Kim MS, Youn JY, et al. Lipolysis in skeletal muscle is decreased in high‐fat‐fed rats. Metabolism 2003; 52: 1586–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koh EH, Lee WJ, Kim MS, et al. Intracellular fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscle and insulin resistance. Curr Diabetes Rev 2005; 1: 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC‐1alpha‐responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 2003; 34: 267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 8466–8471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holland WL, Brozinick JT, Wang LP, et al. Inhibition of ceramide synthesis ameliorates glucocorticoid‐, saturated‐fat‐, and obesity‐induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab 2007; 5: 167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu L, Zhang Y, Chen N, et al. Upregulation of myocellular DGAT1 augments triglyceride synthesis in skeletal muscle and protects against fat‐induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2007; 117: 1679–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee WJ, Song KH, Koh EH, et al. Alpha‐lipoic acid increases insulin sensitivity by activating AMPK in skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 332: 885–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, et al. AMP‐activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab 2005; 1: 15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Peroni OD, et al. Leptin stimulates fatty‐acid oxidation by activating AMP‐activated protein kinase. Nature 2002; 415: 339–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reznick RM, Zong H, Li J, et al. Aging‐associated reductions in AMP‐activated protein kinase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab 2007; 5: 151–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee WJ, Kim M, Park HS, et al. AMPK activation increases fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle by activating PPARalpha and PGC‐1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 340: 291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Soriano FX, Liesa M, Bach D, et al. Evidence for a mitochondrial regulatory pathway defined by peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐gamma coactivator‐1 alpha, estrogen‐related receptor‐alpha, and mitofusin 2. Diabetes 2006; 55: 1783–1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2006; 22: 79–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wredenberg A, Freyer C, Sandstrom ME, et al. Respiratory chain dysfunction in skeletal muscle does not cause insulin resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 350: 202–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pospisilik JA, Knauf C, Joza N, et al. Targeted deletion of AIF decreases mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and protects from obesity and diabetes. Cell 2007; 131: 476–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nair KS, Bigelow ML, Asmann YW, et al. Asian Indians have enhanced skeletal muscle mitochondrial capacity to produce ATP in association with severe insulin resistance. Diabetes 2008; 57: 1166–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu S, Okada T, Assmann A, et al. Insulin signaling regulates mitochondrial function in pancreatic beta‐cells. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e7983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ashcroft FM, Proks P, Smith PA, et al. Stimulus‐secretion coupling in pancreatic beta cells. J Cell Biochem 1994; 55(Suppl.): 54–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lang J. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of insulin exocytosis as a paradigm of endocrine secretion. Eur J Biochem 1999; 259: 3–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu H, Koshkin V, Allister EM, et al. Molecular and metabolic evidence for mitochondrial defects associated with beta‐cell dysfunction in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2010; 59: 448–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koh EH, Kim MS, Park JY, et al. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor (PPAR)‐alpha activation prevents diabetes in OLETF rats: comparison with PPAR‐gamma activation. Diabetes 2003; 52: 2331–2337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Deng S, Vatamaniuk M, Huang X, et al. Structural and functional abnormalities in the islets isolated from type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes 2004; 53: 624–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anello M, Lupi R, Spampinato D, et al. Functional and morphological alterations of mitochondria in pancreatic beta cells from type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2005; 48: 282–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Twig G, Elorza A, Molina AJ, et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J 2008; 27: 433–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jung HS, Chung KW, Won Kim J, et al. Loss of autophagy diminishes pancreatic beta cell mass and function with resultant hyperglycemia. Cell Metab 2008; 8: 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, et al. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD‐dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 2000; 403: 795–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moynihan KA, Grimm AA, Plueger MM, et al. Increased dosage of mammalian Sir2 in pancreatic beta cells enhances glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion in mice. Cell Metab 2005; 2: 105–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kitamura YI, Kitamura T, Kruse JP, et al. FoxO1 protects against pancreatic beta cell failure through NeuroD and MafA induction. Cell Metab 2005; 2: 153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, et al. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC‐1alpha and SIRT1. Nature 2005; 434: 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart‐Hines Z, et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC‐1alpha. Cell 2006; 127: 1109–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Milne JC, Lambert PD, Schenk S, et al. Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature 2007; 450: 712–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Coletta DK, Sriwijitkamol A, Wajcberg E, et al. Pioglitazone stimulates AMP‐activated protein kinase signalling and increases the expression of genes involved in adiponectin signalling, mitochondrial function and fat oxidation in human skeletal muscle in vivo: a randomised trial. Diabetologia 2009; 52: 723–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schrauwen‐Hinderling VB, Mensink M, Hesselink MK, et al. The insulin‐sensitizing effect of rosiglitazone in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients does not require improved in vivo muscle mitochondrial function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 2917–2921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Song KH, Lee WJ, Koh JM, et al. Alpha‐Lipoic acid prevents diabetes mellitus in diabetes‐prone obese rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 326: 197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee WJ, Lee IK, Kim HS, et al. Alpha‐lipoic acid prevents endothelial dysfunction in obese rats via activation of AMP‐activated protein kinase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005; 25: 2488–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Park KG, Min AK, Koh EH, et al. Alpha‐lipoic acid decreases hepatic lipogenesis through adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase (AMPK)‐dependent and AMPK‐independent pathways. Hepatology 2008; 48: 1477–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim MS, Park JY, Namkoong C, et al. Anti‐obesity effects of alpha‐lipoic acid mediated by suppression of hypothalamic AMP‐activated protein kinase. Nat Med 2004; 10: 727–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]