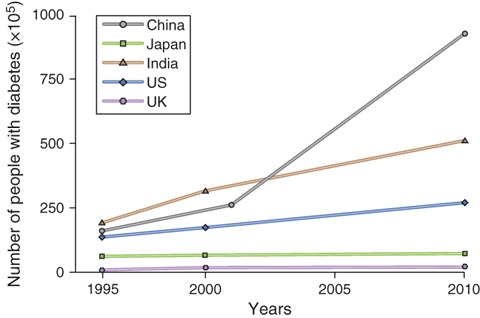

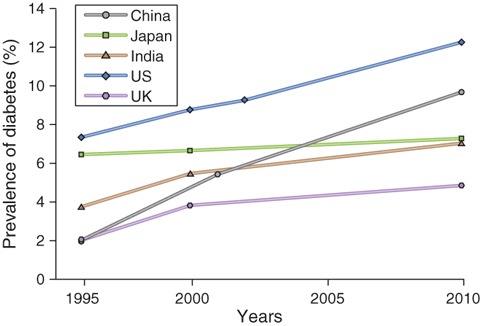

China has made astonishing strides in economic development and has emerged as a strong global partner during the past 30 years. However, the rapid improvement of the standard of living has also exposed the Chinese to new risks that was once thought to be the preserve of the west. New estimates from a population‐based national study carried out in 2008–2009 reported 92.4 million people with diabetes and 148.2 million people with pre‐diabetes1. China, ahead of India now, has become the country with the largest number of people with diabetes in the world (Figure 1). When looking back over the past 15 years, we can see a leap in the prevalence of diabetes in China, in which it increased markedly from 2.0% in 1995 to 5.5% in 2001 and to 9.7% in 2009. The rate of increase is much faster than the USA, India, Japan and the UK (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Number of persons with diabetes in China, Japan, India, the USA and the UK from 1995 to 2010 (Source: Global burden of diabetes, 1995–2025: Prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care 1998, 21: 1414–1431. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2003. Diabetes Care 2004, 27: 1047–1053. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in the Chinese adult population: International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia (InterASIA). Diabetologia 2003, 46: 1190–1198. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010, 87: 4–14).

Figure 2.

The prevalence of persons with diabetes in China, Japan, India, the USA and the UK from 1995 to 2010 (Source: Global burden of diabetes, 1995–2025: Prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care 1998, 21: 1414–1431. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2003. Diabetes Care 2004, 27: 1047–1053. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in the Chinese adult population: International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia (InterASIA). Diabetologia, 2003, 46: 1190–1198. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010, 87: 4–14).

It is, actually, not entirely surprising. The rate of chronic ailments, such as high blood pressure and heart disease – the health problems linked to growing prosperity, has also been steadily climbing in China. Diabetes is a major risk for stroke, heart attack and kidney disease, and the costs incurred by diabetes mobility are far greater than the costs of preventing the disease. It stands that China faces a heavy health care burden and expenditure attributable to diabetes. The estimated national direct medical costs for diabetes and its complications, based on the estimated case numbers of 23.46 million, are reported to be $26 billion a year or 18.2% of China’s total health expenditure in 20072. The latest figures will mean health care expenditure on diabetes in 2010 will increase dramatically. Given the disproportionately high ratio of pre‐diabetes to diabetes, health expenditure will increase substantially in coming decades.

Like many other developing counties, China has experienced dramatic socioeconomic and cultural transitions. The aging of the population, nutritional changes and increasingly sedentary lifestyles, with a consequent epidemic of obesity, have contributed to the national diabetes epidemic. It has something to do with urbanization, but it is also part of a cultural shift away from traditional lifestyles, centered on food rich in fiber and physical activity, to Western modern lifestyles, centered on fatty food and lack of exercise. These have had a particularly large impact in China, but these are modifiable factors. That eating a healthy diet and becoming physically more active can prevent diabetes has been convincingly proven by China’s Daqing Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Diabetes Study3. These findings underline that developing education models calling for the general public to adopt healthy lifestyles is significant for reducing the diabetes epidemic in the future. However, this is a big challenge, because the fast‐food cultural model is now as deeply rooted in Chinese daily life as in Europe and the USA.

We are caring for a huge population with diagnosed diabetes; we are also concerned about the number of people with undiagnosed diabetes. Studies have shown that there is a period of asymptomatic or latent diabetes before clinical recognition; many patients at the time of diagnosis already have diabetic complications. New figures reported that 60.7% of people with diabetes are undiagnosed, among which nearly half of the undiagnosed diabetes met the criteria of elevated 2‐h plasma glucose levels, but not the criteria for fasting glucose levels. A previous study also found that nearly half of inpatients with hyperglycemia had undiagnosed diabetes before admission to a tertiary hospital of Guangdong Province. It is likely to result from public unawareness, but it is also likely to be a result of limited medical resources. Incomplete coverage, uneven access, mixed quality and the escalating cost is China’s main health challenge. Developing early detection and diagnosis strategies by appropriate screening methods, especially in subjects with a high risk for diabetes, is significant. However, as shown by International Diabetes Federation (IDF), this needs to be backed up with sufficient resources to manage and treat larger numbers of people with diabetes. Diagnosing more cases without being able to increase the amount of care available will do little to improve the lives of people with diabetes.

As we know, ethnic differences in insulin sensitivity and β‐cell function in type 2 diabetes exist among ethnically diverse populations. Despite lower body mass index, China has a similar or even higher prevalence of diabetes than Western countries. In the 1980s, Japanese researchers first discovered that early insulin response was an independent predictor to diabetes. Similar to that in Japanese patients, inadequate β‐cell response to increasing insulin resistance results in loss of glycemic control and increased risk of diabetes, even with relatively little weight gain, and seems to be the main defect to the progression of the disease in Chinese patients. Our recent study comparing intensive insulin therapy with oral hypoglycemic agents in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes provided some further evidence4. A greater proportion of patients with intensive insulin therapy, in which treatment was withdrawn after 2 weeks of normoglycemia, achieved glycemic remission compared with oral agents by the end of 1 year. Of note, in the oral agent group, acute insulin response at 1 year declined significantly compared with immediate post‐treatment, but it was maintained in the insulin treatment groups. This suggests that the improvement of β‐cell function is crucial to maintain glycemic control in Chinese type 2 diabetics. Additionally, new drugs including glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) analogs are available in China; whether β‐cell protection could benefit in terms of long‐term glycemic control is currently being clinically trialed. Given that many patients prefer to combine traditional Chinese medicine and Western treatments, more research also needs to investigate the possible interactions or the net effect on the overall efficacy, safety and tolerability.

To the general diabetes population, good glycemic control is known to reduce the risk of long‐term complications. However, a study reported that over 73% of Chinese type 2 diabetics did not reach the target of HbAlc ≤ 6.5% in 2006. The Chinese Diabetes Society developed new diabetes treatment guidelines proposing an early and effectively combination approach. National Health Plan Promotion of Diabetes Management programs targeting providers as well as patients with diabetes have also been promoted. Notwithstanding national and local efforts, widespread implementation of education has remained an elusive goal for many medical centers. A recent investigation, carried out in Jiangsu Province last year, showed that 60% of type 2 diabetics did not reach the target of HbAlc < 6.5%. Fewer patients from secondary and primary hospitals achieved glycemic control compared with those from tertiary hospitals, in which poor education programs might be a major contributor5. We need to develop state‐of‐the‐art education strategies that involve teaching people about preventing and managing disease. The lack of primary health care staff and community health centers throughout the country is also an obstacle to improving the situation.

As IDF pointed out, the prevalence of diabetes in China is a wake‐up call for the government and policy‐makers to take action on diabetes. However, like many countries facing complex health care challenges, multiple institutional and attitudinal obstacles still exist to improving health care, and these barriers have created a substantial and growing gap between what we know and what we actually do. The highest priority is to develop strategies assisting more primary health care providers to recognize and treat diabetes; this is an important basis for national education of disease prevention and treatment. Further, institutional collaborations between Chinese and international scientists are believed to be making an impact by promoting diabetes research and wider educational activities.

References

- 1.Yang WY, Lu JM, Weng JP, et al. , for the China National Diabetes and Metabolic disorders study Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1090–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang W, McGreevey WP, Fu C, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in China: a preventable economic burden. Am J Manag Care 2009; 15: 593–601 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long‐term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20‐year follow‐up study. Lancet 2008; 371: 1783–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weng J, Li Y, Xu W, et al. Effect of intensive insulin therapy on beta‐cell function and glycaemic control in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a multicentre randomised parallel‐group trial. Lancet 2008; 371: 1753–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi Y, Zhu DL, Cheng JL, et al. The Status of glycemic control: a cross‐sectional study of outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus across primary, secondary, and tertiary hospitals in the Jiangsu Province of China. Clin Ther 2010; 32: 973–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]