Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a wide spectrum of liver disease ranging from simple fatty liver (steatosis) to non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and cirrhosis (irreversible, advanced scarring of the liver). What all the stages of NAFLD have in common is the accumulation of fat in the hepatocytes. The prevalence of NAFLD is shown to be approximately 30% of adults among the Western population. Approximately 90% of NAFLD patients have at least one characteristic of metabolic syndrome profile (abnormal glucose level, dyslipidemia, hypertension etc.), which makes a significant impact on developing type 2 diabetes1.

We evaluated approximately 8000 non‐diabetic individuals who underwent comprehensive annual medical check‐ups for 5 years. They were categorized into four groups according to the presence of impaired fasting glucose and NAFLD at baseline. The association between NAFLD and incident diabetes was evaluated separately in groups with normal and impaired fasting glucose. For 4 years, the incidence of diabetes in the NAFLD group was 9.9% compared with 3.7% in the non‐NAFLD group, with multivariable‐adjusted hazard ratio of 1.33 (95% CI 1.07–1.66). This study suggested that NAFLD has an independent and additive effect on the development of diabetes2.

Many therapeutic modalities have been proposed to treat hepatic steatosis, such as lifestyle modification including weight loss and drug treatment with insulin sensitizer (biguanides and thiazolidinediones), cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) receptor antagonists and hepatoprotective or antifibrotic agents (ursodeoxycholic acid, betaine, vitamin E etc.)1.

Thiazolidinediones (TZD) are agonists of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), which is a nuclear transcription factor primarily involved in insulin action, lipid and glucose metabolism, and energy homeostasis. TZD‐activated PPARγ improves insulin sensitivity in most tissues, and have shown effects on lipid metabolism in a cell‐ and tissue‐specific manner. Several randomized controlled clinical trials have shown that TZD improved hepatic steatosis in patients with NASH. However, their favorable effects on liver histology and biochemical markers disappeared on their discontinuation.

Several lines of evidence suggest that TZD activate adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) by both PPARγ‐dependent and ‐independent pathways, implying that AMPK should be a key regulator of the beneficial metabolic effects of TZD. Although the molecular mechanism linking TZD effect on hepatic steatosis has become more understandable, the precise underlying mechanism still requires further understanding.

Our group focused on sirtuin as a candidate mechanism for the effect of TZD on hepatic steatosis. Sirtuins are a family of proteins with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)+‐dependent deacetylase and adenosine diphosphate (ADP)‐ribosyltransferase activities. They control key cellular and physiological processes including apoptosis, energy homeostasis, mitochondrial function and longevity. Seven mammalian sirtuins (Sirt1–7) have been characterized according to their distinct localization patterns and biological functions, and have been suggested as potential therapeutic targets for metabolic syndrome. Sirt1 is a well‐studied nuclear sirtuin with beneficial metabolic effects, which was implicated in the improvement of hepatic steatosis. Sirt1 overexpression in high‐fat diet‐fed mice results in improved glucose tolerance, along with protection from hepatic steatosis and inflammation when compared with wild‐type controls. Sirt6 is another sirtuin localized in the nucleus. Liver‐specific deletion of Sirt6 in mice causes profound alterations in gene expression, leading to increased glycolysis, triglyceride synthesis, reduced β‐oxidation and fatty liver formation. In particular, Sirt6 mutant mice had a slightly higher rate of triglyceride (TG) secretion from the liver to the blood compared with wild‐type mice. Human fatty liver samples showed significantly lowered levels of Sirt6 than normal controls. Thus, Sirt6 plays a critical role in fat metabolism, and might serve as a novel therapeutic target for treating fatty liver disease3.

We planned to address the potential role of Sirt6 in the protective effects of TZD on hepatic steatosis. TZD treatment ameliorated hepatic lipid accumulation and increased expression of Sirt6, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivtor‐1‐α (PGC1‐α) and Forkhead box O1 (Foxo1) in rat livers. AMPK phosphorylation was also increased by TZD accompanied by alterations in phosphorylation of liver kinase B1 (LKB1). Interestingly, in free fatty acid‐treated cells, Sirt6 knockdown increased hepatocyte lipid accumulation measured as increased TG contents, suggesting that Sirt6 might be beneficial in reducing hepatic fat accumulation. In addition, Sirt6 knockdown abolished the effects of TZD on hepatocyte fat accumulation, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and protein expression of PGC1‐α and Foxo1, and phosphorylation levels of LKB1 and AMPK, suggesting that Sirt6 is involved in TZD‐mediated metabolic effects. Our results showed that TZD significantly decreased hepatic lipid accumulation, and that this process appeared to be mediated by the activation of the Sirt6‐AMPK pathway. We proposed Sirt6 as a possible therapeutic target for hepatic steatosis4.

However, several clinical and experimental findings were not consistent or hardly explained in view of the beneficial effect of TZD on hepatic steatosis. For example, PPARγ is upregulated in the liver of obese patients with steatosis and steatohepatitis. Also, the adenoviral gene delivery system to overexpress PPARγ1 in PPARα−/− mouse liver triggers the expression of adipocyte‐specific genes and lipid accumulation in hepatocytes. Based on the mechanism, human and experimental animal models show that PPARγ activation aggravates the hepatic lipid accumulation. However, in the clinical settings, treatment of PPARγ agonist improved hepatic steatosis. AMPK has been proposed as the therapeutic effect of TZD for the treatment of diabetes and hepatic steatosis. However, the short‐term overexpression of AMPK, specifically in the liver by adenoviral vector, decreases hepatic glycogen synthesis and circulating lipid levels, consequently leading to fatty liver as a result of the accumulation of lipids released from adipose tissue.

How can we explain these discrepancies between clinical effects and potential mechanism of TZD? One of the possibilities is the effect of TZD on circulating free fatty acid (FFA). The well‐established effect of TZD on lowering of plasma FFA has therefore been widely considered to be a major factor responsible for their insulin sensitizing effect.

Our animal study also showed the same results. TZD treatment decreased plasma glucose, FF and TG levels. Furthermore, TZD treatment significantly increased bodyweight by gaining fat, especially in non‐mesenteric depots, but not in the mesenteric fat. The level of mRNA of lipid storage genes increased in non‐mesenteric fat, but gene expression related to energy expenditure increased in only mesenteric fat. Therefore, it seemed that TZD treatment was associated with decreased plasma FFA and TG by depot‐specific effects on fat redistribution in individual adipose tissues5.

The other possibility is the dual effect of TZD on both liver and adipocyte. We hypothesized that TZD should decrease hepatic FFA influx from adipocytes and then only improved hepatic steatosis.

We used the co‐culture system to elucidate the interorgan relationship. Two cell populations that were co‐cultivated in different compartments (insert and well) stayed physically separated, but could communicate with each other via paracrine signaling through the pores of the membrane. We used 3T3‐L1 adipocyte in the main well and AML‐12 hepatocytes in the insert well. Hepatocytes and adipocytes co‐cultured with FFA in the presence or absence of TZD for 48 h. The TZD increased fat accumulation in adipocyte, while they decreased the accumulation in hepatocyte under co‐culture environment at the same time. In an isolated hepatocyte culture model, TZD treatment tended to decrease the hepatic lipid accumulation when FFA was added in culture media, but did not normalize it. So the possibility of a non‐FFA mediated TZD effect could not be ruled out.

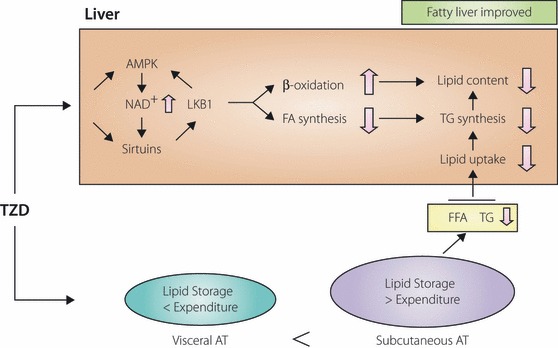

Given the results from the several aforementioned experiments, the beneficial effect of TZD on hepatic steatosis might be indirectly explained by decreasing FFA influx from adipose tissue and directly explained by the effect on the hepatocytes from the molecular mechanisms, such as sirtuin and AMPK (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Suggested mechanism: Thiazolidinediones (TZD) stimulate fatty acid oxidation, and inhibit excessive lipolysis and fatty acid synthesis in the liver, resulting in reduced hepatic fat contents in both rodents and humans. In adipose tissue, TZD‐activated peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) stimulates adipocyte differentiation and induces lipogenic enzymes, thereby increasing fat storage, especially into subcutaneous adipose tissue. This sequestration of lipid into adipose tissue decreases circulating levels of triglyceride and FFA, thus decreasing lipid uptake in the liver. AMPK, adenosine monophosphate‐activated‐activated protein kinase; AT, adipose tissue; FA, fatty acid; FFA, free fatty acid; LKB1, liver kinase B1; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; TG, triglyceride.

In the clinical practices, the beneficial effect of PPARγ activating agents has been well established, but the side‐effects including weight gain, osteoporosis, fluid retention and increased risk of heart failure were identified as serious concerns that limited the clinical use of existing PPARγ agonists. Recently, non‐TZD, such as selective peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma modulator (SPPARM), have been actively under investigation. We hope this kind of agent to be a new and useful one for treating hepatic steatosis, replacing PPARγ agonist.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Samsung Biomedical Research Institute grant, #SBRI C‐B1‐111‐1 and a grant from the Korea Institute of Medicine (http://www.kiom.org). No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Browning JD, Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. J Clin Invest 2004; 114: 147–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae JC, Cho YK, Lee WY, et al. Impact of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on insulin resistance in relation to HbA1c levels in nondiabetic subjects. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 2389–2395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HS, Xiao C, Wang RH, et al. Hepatic‐specific disruption of SIRT6 in mice results in fatty liver formation due to enhanced glycolysis and triglyceride synthesis. Cell Meta 2010; 12: 224–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang SJ, Choi JM, Chae SW, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma by rosiglitazone increases sirt6 expression and ameliorates hepatic steatosis in rats. PLoS One 2011; 23: e17057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang JG, Park CY, Ihm SH, et al. Mechanisms of adipose tissue redistribution with rosiglitazone treatment in various adipose depots. Metabolism 2010; 59: 46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]