Abstract

Solitary fibrous tumors are rare mesenchymal spindle cell neoplasms that are usually found in the pleura. The kidneys are an uncommon site and only few cases of renal solitary fibrous tumor exhibit malignant behavior metastasizing to the liver, lung, and bone through the hematogenous pathway.

Purpose

To describe the first case of lymph node metastasis from renal solitary fibrous tumor in order to increase the knowledge about the malignant behavior of these tumors.

Patients and methods

A 19-year-old female patient had intermittent hematuria for several months without flank pain or other symptoms. A chest and abdomen CT scan was performed and showed a multi-lobed bulky solid mass of 170 × 98 × 120 mm in the left kidney. One day before the surgery, the left renal artery was catheterized and the kidney embolization was performed using a Haemostatic Absorbable Gelatin Sponge and polyvinyl alcohol. We then performed a radical nephrectomy with hilar, para-aortic, and inter-aortocaval lymphadenectomy.

Results

Estimated intraoperative blood loss was 200 mL and the operative time was 100 minutes. No postoperative complications occurred. The hospital stay was 7 days long. The histological examination was malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney. Cancerous tissue showed cellular atypia, with an increased mitotic index (up to 7 × 10 hpf). Immunohistochemical analysis showed positive results for CD34, BCL2, partial expression of HBME1, and occasionally of synaptophysin. Histological evaluation confirmed the presence of metastasis in one hilar node. The patient did not receive any other therapy. At 30-month follow-up, the patient was in good health and no local recurrence or metastases had occurred.

Conclusion

This is the first case of lymph node metastasis from a renal solitary fibrous tumor showing unusual malignant behavior; this finding adds new information about the biology and progression of these tumors, which remain unclear.

Keywords: solitary fibrous tumor, sarcoma, kidney, lymph node metastases, lymphadenectomy

Introduction

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), also known as hemangiopericytoma, are rare and heterogeneous mesenchymal spindle cell neoplasms. There are three typical primary locations: pleural, meningeal, and extrathoracic soft tissue.1 The kidneys are an uncommon site and to our knowledge, only 49 cases of renal SFT have been described in the literature; 42 cases had benign behavior and only seven cases were malignant (Tables 1 and 2).2–4 Due to their rarity, little is known about the evolution of these tumors, but most SFTs show slow progression with a favorable prognosis. However, it is estimated that 10%–15% of intrathoracic SFTs and up to 10% of extrathoracic SFTs will recur and/or metastasize.5,6 Only a few cases of renal SFTs exhibit malignant behavior and they usually metastasize to the liver, lung, and bone through the hematogenous pathway.7 Nodal metastases of SFT are reported in up to 7% of the pleural form.8

Table 1.

Review of the 42 cases of benign SFT of the kidney

| Case | Reference | Age | Sex | Size (cm) | Follow-up (months) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fain et al19 | 45 | F | 6 | 8 | Tumor free |

| 2 | Fain et al19 | 46 | F | 7.2 | 33 | Tumor free |

| 3 | Fain et al19 | 51 | M | 4.5 | 2 | Tumor free |

| 4 | Gelb et al9 | 48 | F | 3 | 1 | Dead from other cause |

| 5 | Fukunaga and Nakaido20 | 33 | F | 3.5 | 90 | Tumor free |

| 6 | Fukunaga and Nakaido20 | 36 | F | 2 | 12 | Tumor free |

| 7 | Hasegawa et al21 | 64 | M | 4.5 | 8 | Tumor free |

| 8 | Leroy et al22 | 66 | F | 9 | 9 | Tumor free |

| 9 | Morimitsu et al23 | 72 | F | 8 | 10 | Tumor free |

| 10 | Yazaki et al24 | 70 | M | 6 | NA | Tumor free |

| 11 | Wang et al25 | 41 | M | 14 | 48 | Tumor free |

| 12 | Wang et al25 | 72 | M | 13 | 5 | Tumor free |

| 13 | Cortes-Gutierrez26 | 28 | F | 15 | 12 | Tumor free |

| 14 | Magro et al27 | 31 | F | 8.6 | 8 | Tumor free |

| 15 | Durand et al28 | 35 | M | 17 | 6 | Tumor free |

| 16–17 | Llarena-Ibarguren29 | 51 | F | 25-2 | NA | Tumor free |

| 18 | Bugel et al30 | 60 | F | 11 | 48 | Tumor free |

| 19 | Gres et al31 | 82 | M | 9 | 13 | Tumor free |

| 20 | Yamada et al32 | 59 | M | 6.8 | NA | Tumor free |

| 21–27 | Pierson et al33 | (29–79) 52.6 | NA | (2.2–10) 5.7 | NA | Tumor free |

| 28 | Kawagoe et al34 | 83 | F | 11 | 20 | Tumor free |

| 29 | Johnson et al35 | 51 | F | 11 | NA | Tumor free |

| 30 | Yamaguchi et al | 51 | F | 10 | NA | Tumor free |

| 31 | Kohl et al37 | 85 | F | 3.5 | NA | Tumor free |

| 32 | Koroku et al38 | 18 | F | 3.2 | 15 | Tumor free |

| 33 | Provance/Ferrari et al39 | 4 | M | 8 | NA | Tumor free |

| 34 | Bozkurt40 | 51 | F | 4 | 10 | Tumor free |

| 35 | Znati et al41 | 70 | M | 15 | 6 | Tumor free |

| 36 | Constantinidis et al42 | 26 | M | 5 | 6 | Tumor free |

| 37 | Hirabayashi et al43 | 44 | F | 5.8 | 28 | Tumor free |

| 38 | Amano et al44 | 67 | M | 7 | 10 | Tumor free |

| 39 | Yoneyama et al45 | 76 | F | 2.2 | 48 | Tumor free |

| 40 | Hirano et al46 | 75 | M | 4.5 | 9 | Tumor free |

| 41 | Taxa et al47 | 39 | F | 2.5 | 12 | Tumor free |

| 42 | Yamaguchi et al | 39 | F | 20 | 6 | Tumor free |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; SFT, solitary fibrous tumor.

Table 2.

Review of the seven cases of malignant SFT of the kidney

| Case | Reference | Age | Sex | Size (cm) | Follow-up (months) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fine et al48 | 76 | M | 12 | 4 | Persistent tumor |

| 2 | Magro et al49 | 34 | F | 9 | 15 | Tumor free |

| 3 | Marzi et al50 | 72 | F | 19 | NA | NA |

| 4 | Hsieh et al51 | 50 | F | 9 | 30 | Tumor free |

| 5 | De Martino et al52 | 68 | F | 7 | 5 | Death by the disease |

| 6 | Cuello and Brugés4 | 49 | F | 9.8 | 23 | Stable disease |

| 7 | Mearini et al | 19 | F | 17 | 32 | Tumor free |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; SFT, solitary fibrous tumor.

To our knowledge, no lymph node metastases from renal SFT were reported.

The aim of this study was to describe the first case of malignant renal SFT metastasizing to lymph node in order to increase the knowledge about the malignant behavior of these tumors.

Materials and methods

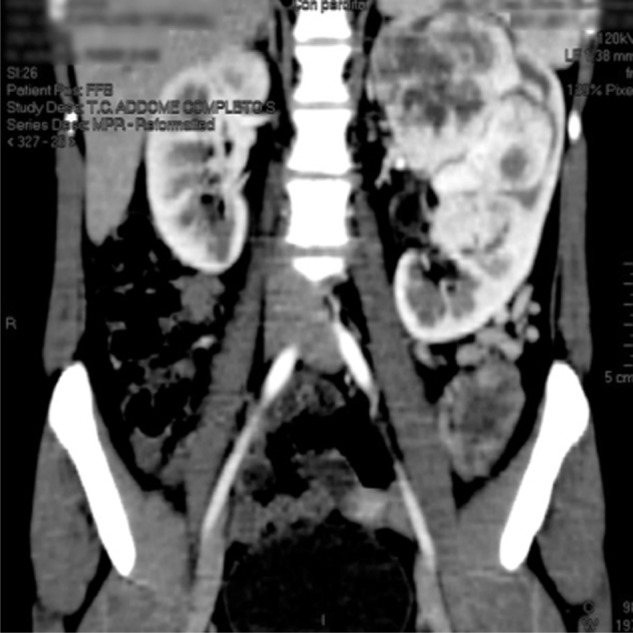

A 19-year-old female patient had intermittent hematuria for several months without flank pain or other symptoms. Laboratory blood analyses were normal, renal function was normal with serum creatinine of 0.96 mg/dL and estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula was 80 mL/minute. There were no glucose concentration abnormalities at blood evaluation. Physical examination revealed a palpable left flank mass. Cystoscopy and urinary cytology were performed because of gross hematuria in order to exclude bladder disease. They showed no pathological findings. The abdominal ultrasound scan detected a huge solid mass of the left kidney. A chest and abdomen CT scan was carried out and confirmed a multi-lobed bulky solid mass of 170 × 98 × 120 mm in the left kidney, which extended over the cortex, with intense contrast enhancement during the arterial phase. The imaging findings were attributable to the combination of variable cellularity with dense collagen content and focal hemangiopericytomatous vascular pattern. Necrosis and hemorrhage were present. Hydronephrosis was present and the lesion did not infiltrate the intestinal loops, the pancreatic tail, the splenic hilum, or parenchyma. The left renal vein caliber was increased, but without endoluminal thrombus. Abdominal lymph node disease was not clinically evident on preoperative staging imaging (Figures 1 and 2). Differential diagnosis was considered for renal cell carcinoma, other non-clear cell renal carcinoma, sarcoma, or adult Wilms tumor, but throughout the radiological imaging, we could not state the histological type of the lesion. After obtaining informed consent, 1 day before the surgery, the left renal artery was catheterized and the kidney embolization was performed using a Haemostatic Absorbable Gelatin Sponge (Spongostan, Ethicon™, Somerville, NJ, USA) and polyvinyl alcohol in order to decrease the intraoperative bleeding risk. We then performed a radical nephrectomy with hilar, para-aortic, and inter-aortocaval lymphadenectomy. Perirenal fat tissue, the ipsilateral adrenal gland, and 25 mm tract of ureter were also removed.

Figure 1.

A computed tomography scan showing the left renal mass.

Figure 2.

A computed tomography scan image showing the left renal mass with no vascular extension.

Results

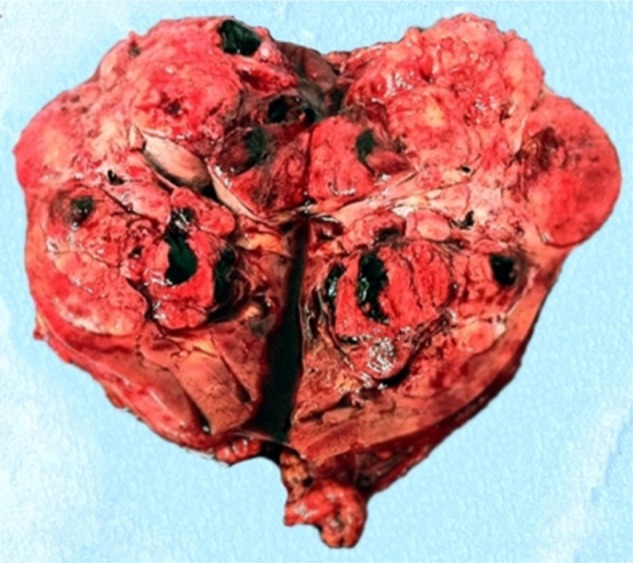

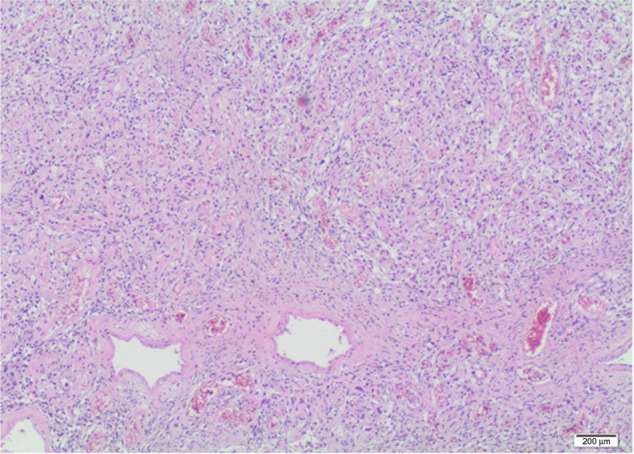

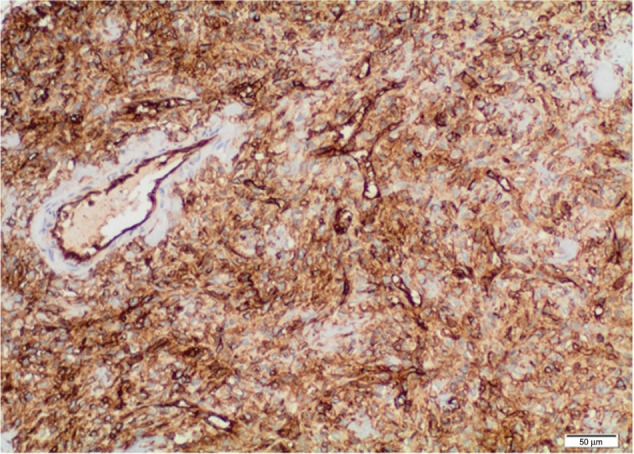

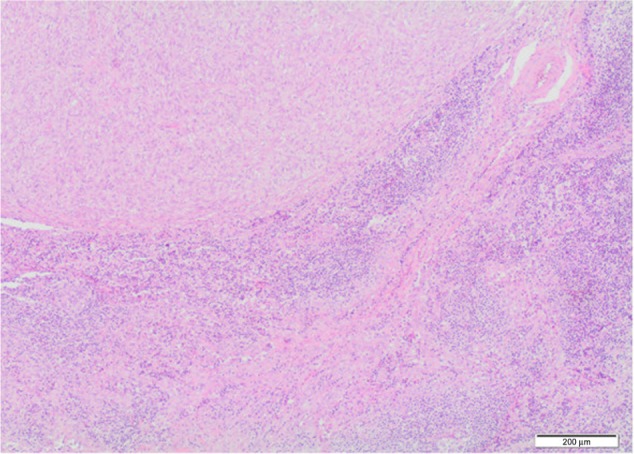

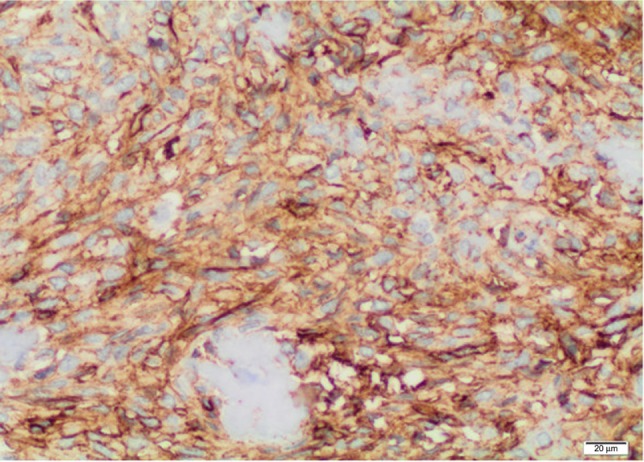

Estimated intraoperative blood loss was 200 mL and the operative time was 100 minutes. The hospital stay was 7 days long. Seven days after surgery, serum creatinine and eGFR were 0.98 mg/dL and 81 mL/minute, respectively; after 30 months, serum creatinine and eGFR remained the same. No postoperative complications occurred. Tumor size was 145 × 90 × 85 mm. The specimen was a yellowish-gray solid mass, well circumscribed with some areas of hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 3). There was no evidence of any perirenal structures or vessel infiltration, but hilar lymph nodes seemed to be involved. The histological examination was malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney. Cancerous tissue showed cellular atypia, with an increased mitotic index (up to 7 × 10 hpf; Figure 4). Immunohistochemical analysis showed positive results for CD34, BCL2, partial expression of HBME1, and occasionally of synaptophysin. Immunohistochemistry was negative for CD99, calretinin, CD117/CKIT, DOG1, desmin, smooth muscle actin, muscle specific actin, myogenin, myoglobin, EMA, AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 14, cytokeratin 19, chromogranin-A, CD56, CD31, S100, Melan A/MART1, HMB45, and PGM1. The Ki67/MiB1 was equal to 10% in the areas with increased cellular proliferation (Figure 5). Twelve lymph nodes were removed and histological evaluation confirmed the presence of metastasis in one hilar node (Figure 6). The size of the involved node was 0.8 cm and showed the same histological aspects of the renal lesion; also, the immunohistochemical analysis confirmed the presence of SFT metastasis (Figure 7). This diagnosis was confirmed by a review carried out by the Italian Rare Tumor Network. The patient did not receive any other therapy. At the 30-month follow-up, the patient was in good health and no local recurrence or metastases had occurred.

Figure 3.

Operatory specimen showing a multilobulate tumor mass of size 170 × 98 × 120 mm with multiple necrotic areas.

Figure 4.

Microscopic evaluation of the tumor specimen.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the renal SFT.

Abbreviation: SFT, solitary fibrous tumor.

Figure 6.

Microscopic findings of lymph node metastasis.

Figure 7.

Lymph node immunohistochemical analysis.

Discussion

The kidney is an unusual site of solitary fibrous tumor, and it was described for the first time by Gelb et al in 1996.9 Although in most cases it cannot be clearly defined which renal tissue the solitary fibrous tumor arose from, renal parenchyma, the urinary tract, the capsule, or the peri-hilar fat may be involved. At diagnosis, age ranges from 3–82 years.3,7 The male-to-female ratio appears to be almost equal (1:1.5).10 The symptoms do not differ from those of renal clear cell carcinoma and the diagnosis is generally occasional. Contrary to the renal SFT, the most common pleural forms are symptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Pleurodynia, cough, and dyspnea due to compression appear as symptoms. In pleural SFTs two paraneoplastic syndromes could occur: Pierre Marie– Bamberger syndrome, also called pulmonary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, has been reported in 20% of cases and it seems to be due to a higher production of hyaluronic acid or hepatocyte growth factors by the tumor.11 Doege–Potter syndrome is a paraneoplastic hypoglycemia often associated with massive SFT; about 40% of pleural SFTs with hypoglycemia are malignant. This hypoglycemia seems to be related to the tumor-producing non-suppressible insulin-like active factor and insulin-like growth factors.12

Median overall survival (OS) of benign pleural forms is about 280 months, whereas the median OS of malignant forms is about 50–60 months.1 Because lymph node metastases constitute up to 7% of pleural forms, mediastinal node dissection is not indicated.8 Metastases through the hematogenous pathway mainly involve the liver, lungs, and bones. Local recurrences are more frequent in malignant cases. Fifteen to 35% of pleural SFT are considered malignant at the time of diagnosis.1 The prognosis of extrapleural SFTs is more unpredictable than that of pleural tumors due to a lack of large-scale studies. The diagnosis of malignancy in renal forms as well as in pleural ones follows England’s criteria that include increased cellularity, cellular pleomorphism and anaplasia, a mitotic count greater than 4–10 fields of magnification, the presence of necrotic areas and/or bleeding, size exceeding 10 cm, and abnormal presentation sites.13 For renal SFTs, the differential diagnosis includes the sarcomatoid form of renal cancer, angiomyolipoma, fibroma, and fibrosarcoma, which includes all tumors showing a hemangiopericytoma-like pattern. The renal solitary fibrous tumor size ranges 2–25 cm and is rarely a multifocal lesion.11,12 To our knowledge, the malignancy of SFTs can be present ab initio or can occur as sarcomatoid differentiation of a benign one. Histologically, these tumors are characterized by a pattern of growth consistent in hypercellular plump of spindle cells haphazardly intermixed in a dense hypocellular collagenous stroma with variable vascularity. Sometimes the vessels have a hemangiopericytoma-like appearance (branching vessels). The tumor cells have a faint eosinophilic cytoplasm, inconspicuous nucleoli, and evenly distributed fine nuclear chromatin. The cells are haphazardly arranged within a dense collagenous, sometimes keloid-like, stroma. Due to the broad differential diagnosis associated with their clinical presentation and histopathologic features, a panel of immunohistochemical markers has become paramount in accurately diagnosing SFTs.

In terms of immunohistochemistry, the SFT is positive for CD34 (in 90%–95% of cases), BCL2 (50%), EMA (30%), and actin and vimentin (20%); positivity can sometimes also be expressed for protein S-100, desmin, and different cytokeratins.9,10 The most useful marker is CD34, which is very sensitive for SFTs but is not entirely specific for SFTs because it is expressed in a variety of spindle-cell neoplasms, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans or neural tumors. Surgical treatment is the first therapeutic option and the radical exeresis of the tumor is the gold standard therapy. Chemotherapy alone or combined with radiotherapy is reserved for multi-metastatic disease or for ones that cannot be surgically removed. A new therapeutic possibility with imatinib mesylate has recently been reported for metastatic intrapleural SFT characterized by wild type PDGFR-β expression.14,15

Clinically, a differential diagnosis between a locally advanced renal cell carcinoma or renal sarcoma is not possible; therefore, renal solitary fibrous tumor should be surgically treated as a poorly differentiated or as a locally advanced renal cell cancer due to its large size. For this reason, we performed radical nephrectomy, including the removal of the kidney, perinephric fat, Gerota’s fascia, and the adrenal gland. The lymphadenectomy should be performed when lymph nodes are increased at imaging or when there is a palpable report during surgery. Enlarged hilar or retroperitoneal nodes ≥2 cm in diameter on CT are often malignant, but histological validation is necessary because the false positive rate is as high as 60%, mainly due to reactive inflammation.16 Moreover, in adolescent patients with a renal mass, in which the differential diagnosis includes translocation renal cell carcinoma, adolescent Wilms tumor, sarcomas, or angiomyolipoma, the lymph node involvement incidence is higher in the adolescent from than in the adult form; it has been reported between 25%–33% compared to 10%–15%, respectively.17 Lymph node infiltration has been reported even in relatively small renal tumors in adolescents contrary to in the adult form, where nodal disease is rare.18 In our case, we performed lymphadenectomy because we considered the tumor to be high-risk disease due to its large size and the patient’s age. By finding micrometastatic lymph node disease, we could increase the chances of upstaging the tumor and decrease the risk of local recurrence.

Since metastases from SFTs are reported even after 15–20 years after the primary diagnosis,11 the patient will be followed up in the long term. In renal malignant SFTs, there were not any international guidelines about follow-up schedule: we recommend a strategy based on clinical evaluation and chest and abdominal CT every 4 months for the first 2 years. In the third year, the chest and abdominal CT scan will be repeated only once due to the morbidity risk associated with radiation exposure; the close follow-up is based on an ultrasound scan of the abdomen and a chest radiography every 6 months. From the 4th year to a further 10 years of follow-up, a CT scan of the chest and the abdomen will be performed once a year.

Conclusion

We reported the first case of lymph node metastasis from renal SFT showing unusual malignant behavior; this finding adds new information about the biology and progression of these tumors, which remain unclear.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Penel N, Amela EY, Decanter G, Robin YM, Marec-Berard P. Solitary fibrous tumors and so-called hemangiopericytoma. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:690251. doi: 10.1155/2012/690251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katabathina VS, Vikram R, Nagar AM, Tamboli P, Menias CO, Prasad SR. Mesenchymal neoplasms of the kidney in adults: imaging spectrum with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30:1525–1540. doi: 10.1148/rg.306105517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu WW, Chu JT, Romansky SG, Shane L. Pediatric renal solitary fibrous tumor: report of a rare case and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2013 Jul 1; doi: 10.1177/1066896913492847. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuello J, Brugés R. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: report of the first case managed with interferon. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:564980. doi: 10.1155/2013/564980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Soft tissue tumors of intermediate malignancy of uncertain type. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Soft Tissue Tumor. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. pp. 1093–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vallat-Decouvelaere AV, Dry SM, Fletcher CD. Atypical and malignant solitary fibrous tumors in extrathoracic locations: evidence of their comparability to intra-thoracic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1501–1511. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, et al. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2002;94(4):1057–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milano MT, Singh DP, Zhang H. Thoracic malignant solitary fibrous tumors: a population-based study of survival. J Thorac Dis. 2011;3(2):99–104. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.01.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelb A, Simmons M, Weidner N. Solitary fibrous tumor involving the renal capsule. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1288–1295. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine SW, McCarthy DM, Chan TY, Epstein JI, Argani P. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: report of a case and comprehensive review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(6):857–861. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-857-MSFTOT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thakkar RG, Shah S, Dumbre A, Ramadwar MA, Mistry RC, Pramesh CS. Giant solitary fibrous tumour of pleura – an uncommon intrathoracic entity – a case report and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(4):400–403. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.10.01589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalebi AY, Hale MJ, Wong ML, Hoffman T, Murray J. Surgically cured hypoglycemia secondary to pleural solitry fibrous tumour: case report and update review on the Doege-Potter syndrome. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:45. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.England D, Hochholzer L, McCarthy M. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura: a clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640–658. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prunotto M, Bosco M, Daniele L, et al. Imatinib inhibits in vitro proliferation of cells derived from a pleural solitary fibrous tumor expressing platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:244–246. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Pas T, Toffalorio F, Colombo P, et al. Brief report: activity of imatinib in a patient with platelet-derived-growth-factor receptor positive malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:938–941. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181803f08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Studer UE, Scherz S, Scheidegger J, et al. Enlargement of regional lymph nodes in renal cell carcinoma is often not due to metastases. J Urol. 1990;144:243–245. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cost NG, Cost CR, Geller JI, Defoor WR., Jr Adolescent urologic oncology: current issues and future directions. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(2):59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jewett MA, Mattar K, Basiuk J, et al. Active surveillance of small renal masses: progression patterns of early stage kidney cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;60:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fain JS, Eble J, Nascimento AG, Farrow GM, Bostwick DG. Solitary fibrous tumors of the kidney: report of three cases. J Urol Pathol. 1996;4:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukunaga M, Nikaido T. Solitary fibrous tumor of the renal peripelvis. Histopathology. 1997;30:451–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.5570775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, Hasegawa F, Sano T, Hirohashi S. Extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors: their histological variability and potentially aggressive behavior. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1464–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leroy X, Copin MC, Coindre JM, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the kidney. Urol Int. 2000;65:49–52. doi: 10.1159/000064835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morimitsu Y, Nakajima M, Hisoka M, Hashimoto H. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: clinicopathologic study of 17 cases and molecular analysis of the p53 pathway. APMIS. 2000;108:617–625. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yazaki T, Satoh S, Iizumi T, Umeda T, Yamaguchi Y. Solitary fibrous tumor of renal pelvis. Int J Urol. 2001;8:504–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Arber DA, Frankel K, Weiss LM. Large solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1194–1199. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortes-Gutierrez E, Arista-Nasr J, Mondragon M, Mijangos-Parada M, Lerma-Mijangos H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney. J Urol. 2001;166:602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magro G, Cavallaro V, Torrisi A, Lopes M, Dell’Albani M, Lanzafame S. Intrarenal solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: report of a case with emphasis on the differential diagnosis in the wide spectrum of monomorphous spindle cell tumors of the kidney. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:37–43. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durand X, Deligne E, Camparo P, Riviere P, Best O, Houlgatte A. Solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney. Prog Urol. 2003;13:491–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llarena Ibarguren R, Eizaguirre Zarzai B, Lecumberri Castanos D, et al. Bilateral renal solitary fibrous tumor. Arch Esp Urol. 2003;56:835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bugel H, Gobet F, Baron M, Pfister C, Sibert L, Grise P. Solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney and other sites in the urogenital tract: morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics. Prog Urol. 2003;13:1397–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gres P, Avances C, Ben Naoum K, Chapuis H, Costa P. Solitary fibrous tumors of the kidney. Prog Urol. 2004;14:65–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada H, Tsuzuki T, Yokoi K, Kobayashi H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney originating from the renal capsule and fed by the renal capsular artery. Pathol Int. 2004 Dec;54(12):914–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierson DM, Dimashkieh HH, Isotalo PA, Nascimento AG, Sanderson SO, Cheville JC. Solitary fibrous tumors of the kidney: a clinicopathologic study of seven cases. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(suppl 1):159A. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawagoe Mari, et al. Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Kidney: A Case Report. Nishinihon Journal of Urology. 2005;67.9:568. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson TR, Pedrosa I, Goldsmith J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29:481–483. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000166637.24037.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaguchi T, Takimoto T, Yamashita T, et al. Fat-containing variant of solitary fibrous tumor (lipomatous hemangiopericytoma) arising on surface of kidney. Urology. 2005;65:175. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohl SK, Mathews K, Baker J. Renal hilar mass in an 85-year-old woman. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(1):117–119. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-117-RHMIAY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koroku Mikio, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of a kidney: a case report. Hinyokika kiyo. Acta urologica Japonica. 2006;52.9:705–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrari ND, Nield LS. Final diagnosis: solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2006;45(9):871–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bozkurt SU, Ahiskali R, Kaya H, Demir A, Ilker Y. Solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney. Apmis. 2007;115(3):259–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Znati K, Chbani L, El Fatemi H, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: a case report and review of the literature. Reviews in urology. 2007;9(1):36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Constantinidis C, Koutalellis G, Liapis G, Stravodimos C, Alexandrou P, Adamakis I. A solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney in a 26-year-old man. The Canadian journal of urology. 2007;14(3):3583–3587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirabayashi A, Ogura Y, Wakita T, Hayashi N. Solitary fibrous tumor of a kidney: a case report. Hinyokika kiyo. Acta urologica Japonica. 2008;54(5):357–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amano T, Imao T, Takemae K, Tsuruta T, Watanabe M, Hata S. Renal solitary fibrous tumor with emangiopericytoma-like pattern—a case report. Hinyokika kiyo. Acta urologica Japonica. 2008;54(12):765–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoneyama T, Koie T, Yamamoto H, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: a case report. Hinyokika kiyo. Acta urologica Japonica. 2009;55(8):479–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirano, et al. A case of solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study with a review of the literature. Medical molecular morphology. 2009;42(4):239–244. doi: 10.1007/s00795-009-0456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taxa L, Huanca L, Meza L, Pow Sang M. Solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney (a case report) Actas Urológicas Españolas. 2010;34(6):568–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fine SW, McCarthy DM, Chan TY, Epstein JI, Argani P. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: report of a case and comprehensive review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(6):857–861. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-857-MSFTOT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magro G, Emmanuele C, Lopes M, Vallone G, Greco P. Solitary fibrous tumour of the kidney with sarcomatous overgrowth. Apmis. 2008;116(11):1020–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marzi M, Piras P, D’Alpaos M, et al. The solitary fibrous malignant tumour of the kidney: clinical and pathological considerations on a case revisiting the literature. Minerva urologica e nefrologica. 2011;63(1):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsieh TY, ChangChien YC, Chen WH, et al. De novo malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney. Diagnostic pathology. 2011;6(1):96. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Martino M, Böhm M, Klatte T. Malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the kidney: report of a case and cumulative analysis of the literature. Aktuelle Urologie. 2012;43(1):59–62. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1283853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]