Abstract

Researchers have noted increasingly the public health importance of addressing discriminatory policies towards lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations. At present, however, we know little about the mechanisms through which policies affect LGB populations’ psychological well-being; in other words, how do policies get under our skin? Using data from a study of sexual minority young men (N = 1,487; M = 20.80 (SD = 1.93); 65 % White; 92 % gay), we examined whether statewide bans (e.g., same-sex marriage, adoption) moderated the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and psychological well-being. Fatherhood aspirations were associated with lower depressive symptoms and higher self-esteem scores among participants living in states without discriminatory policies. In states with marriage equality bans, fatherhood aspirations were associated with higher depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem scores, respectively. Fatherhood aspirations were associated negatively with self-esteem in states banning same-sex and second parent adoptions, respectively. Our findings underscore the importance of recognizing how anti-equality LGB policies may influence the psychosocial development of sexual minority men.

Keywords: Gay, Discrimination, Resilience

Introduction

By definition, policies that create inequalities for sexual minority populations (e.g., bans against same-sex marriage, joint same-sex adoptions, and/or single-parent adoptions) create social obstacles for sexual minority populations and hinder the potential enactment of their future goals through unequal access to social resources, exposure to minority stressors, and increased vulnerability to psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler 2010; Riggle et al. 2005; Russell and Richards 2003). Using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), Hatzenbuehler et al. (2009) documented how sexual minority individuals living in states that do not extend legal protections to lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) populations were more likely to report psychiatric comorbidity than those who lived in states with fewer restrictions. Similarly, researchers have also documented that the passing of same-sex marriage bans in statewide elections are associated with increased psychological distress among sexual minority populations (Hatzen-buehler et al. 2010; Riggle et al. 2009; Rostosky et al. 2009). Taken together, these findings underscore the public health importance of examining how public policies affect the psychological well-being of LGB populations. At present, however, we know little about the mechanisms through which policies affect LGB populations’ psychological well-being; in other words, how do policies get under our skin? One potential mechanism may be that these policies erode the protective influences that hopeful thinking has on psychological well-being. To test this potential moderating relationship, we examined whether statewide discriminatory policies (e.g., same-sex marriage, adoption bans) influenced negatively the relationship between emerging adult sexual minority men’s fatherhood aspirations (i.e., their future orientation about having children) and psychological well-being.

Parenting Desires Among LGB Populations

Researchers have recognized LGB populations’ parenting desires and intentions (Badgett 2001; Gates 2011; Gates et al. 2007; Goldberg et al. 2012; Mallon 2004). Often stereotyped as not desiring children, prior research has documented that LGB individuals consider parenting as a rewarding milestone in their lives (Badgett 2001; Goldberg et al. 2012). Using data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), for example, Gates and colleagues (Gates et al. 2007) documented that 52 % of gay men and 41 % of lesbians without children reported wanting to have children. In a subsequent study using the 2002 NSFG data, Riskind and Patterson (2010) found that gay men who desired children were less likely than heterosexual men to intend to have them. Riskind and Patterson (2010), however, did not observe this discrepancy among women. This discrepancy may be attributable to the intersections of gender and sexual orientation, as men in same-sex couples may face greater reproductive barriers and/or encounter more structural difficulties when seeking to adopt as the sole caregiver or in a same-sex couple (Berkowitz and Marsiglio 2007; Drumright et al. 2006; Gurmankin et al. 2005; Mallon 2004; Patterson 2009; Riskind et al. 2013). In light of these developmental and gender differences, in this study, we sought to describe sexual minority young men’s fatherhood aspirations.

Developmentally, emerging adulthood, ages 18–25, has been characterized as a period when individuals explore and refine their life aspirations across a range of domains including family, relationships, and work (Arnett 2000). While these aspirations serve to aid emerging adults’ decisions and goal setting as they transition into adulthood, considering them may be particularly onerous for sexual minorities, as they must conceptualize their lives without the aid of traditional cultural scripts (Rabun and Oswald 2009). Compared to studies with adult populations, however, only a handful of studies have examined sexual minority adolescents and emerging adults’ fatherhood aspirations (D’Augelli et al. 2008; Gates 2011; Riskind and Patterson 2010). D’Augelli et al. (2008), for example, noted that 86 % of gay male adolescents living in the greater New York City area reported a desire to become a parent in the future. Riskind and Patterson (2010) also noted that younger gay men in the 2002 NSFG were more likely to endorse a desire to have children than older gay men, as well as more likely to report feeling bothered about the prospect of not being able to have children. Taken together, these studies suggest that younger cohorts of gay men are more likely to conceptualize and desire fatherhood as a milestone in their adult lives than older cohorts of gay men (Berkowitz and Marsiglio 2007; Rabun and Oswald 2009). Consequently, in this study, we sought to examine the importance attributed to fatherhood aspirations among emerging adult sexual minority men and its association to their psychological well-being.

The Role of Context in the Relationship Between Fatherhood Desires and Psychological Well-Being

In most of the future orientation literature, researchers have employed individual-level models and found that having hopes and dreams about the future is a protective factor in the lives of adolescent and emerging adults. Goal–oriented thoughts about the future are essential components of learning and stress management (Bandura 1977; Magaletta and Oliver 1999; Snyder 1995). The salience of future goals across different life domains (e.g., education, work, family, relationships) has been associated with increased promotive health behaviors and with decreases in risk outcomes among adolescents and young adults (Bauer-meister et al. 2012; Bauermeister 2012; Burrow and Hill 2011; Elkington et al. 2011; Stoddard and Garcia 2011; Stoddard et al. 2011; Valle et al. 2006; Weis and Ash 2009). Although these findings suggest that future goals may be health promotive (Snyder et al. 2000; te Riele 2010), individuals must possess the ability to achieve these future goals (Snyder 1995). Less is known, however, about the role that social contexts play in the relationship between future goals and health outcomes.

Researchers have noted that individuals who perceive unattainability when thinking about achieving their goals, or encounter roadblocks or impediments, are more likely to experience negative emotions and distress (Snyder et al. 2002). Consequently, in order to understand the relationship between future desires and psychological well-being, it is important to consider future goals (i.e., the will) and the ability to achieve these goals (i.e., the way). Furthermore, although everyone has an intrinsic sense of hope and future orientation (Snyder 1995), it is also important to recognize that domain-specific life goals (e.g., family, work) may be affected by distinct social barriers, which in turn may have various effects on individuals’ psychological well-being. From a Self-Determination Theory perspective (Ryan and Deci 2000), for example, it is vital for individuals to have their intrinsic motivations supported by their social context if they are to achieve optimal well-being; otherwise, unsupported or thwarted motivations may have a detrimental effect on their well-being. Thus, even if sexual minority men were to express a desire to have children in the future, existing policies that counter, ban, or hinder their ability to achieve these goals in the future may influence their well-being. As a contribution to this literature, we sought to examine whether the relationship observed between fatherhood aspirations and psychological well-being varied depending on whether individuals’ lived in states where LGB bans were in place or not.

Study Goals and Objectives

Given the increasing recognition that younger sexual minority cohorts are more likely to envision fatherhood in the future than older counterparts (D’Augelli et al. 2008; Gates 2011; Riskind and Patterson 2010), we sought to examine the salience of fatherhood aspirations among emerging adult sexual minority men across the United States and its association to their psychological well-being. Consistent with prior findings on future orientation, we hypothesized that individuals who placed greater importance on future expectations regarding fatherhood would also report greater psychological well-being. Beyond having big dreams about the future, however, individuals must have the social means to make these goals become a reality. Given the increasing recognition of the relationship between psychological distress and statewide policies banning LGB equality (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2009; Riggle et al. 2009; Rostosky et al. 2009), we tested whether existing statewide policies banning marriage equality and adoptions, respectively, moderated the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms and self-esteem. Consistent with prior findings (Snyder et al. 2002; Ryan and Deci 2000), we hypothesized that the promotive association between fatherhood aspirations on psychological well-being would be eroded among men living in states with restrictive policies.

Methods

Sample

Data for this article come from a cross-sectional observational study examining single sexual minority emerging adults’ sexual health experiences. Data were collected online between July 2012 and January 2013. To be eligible for participation, recruits had to self-identify as male, be between the ages of 18 and 24, report being single, identify as having same-sex attractions, and be a resident of the United States (including Puerto Rico). Participants were recruited primarily through targeted advertisements on two popular social networking sites and participant referrals. Social network advertisements were viewable only to men who fit our age range, reported attraction to other men, and who lived in the United States. Promotional materials displayed a synopsis of eligibility criteria, a mention of a $10 VISA e-card incentive, and the survey’s website.

Using best practices for online data collection (Bauer-meister et al. 2012), we identified 1,963 valid entries. Of these, 325 participants consented but did not commence the survey (i.e., missing all data; 16.6 %), resulting in an analytic sample of N = 1,638 eligible emerging adult sexual minority men. Participants reported living in 51 US states and territories, including Puerto Rico and Washing-ton D.C. None of our participants reported living in South Carolina. Across the US Census Region, 25.7 % of the sample lived in the Midwest, 19.2 % lived in the Northeast, 27.6 % lived in the South, 26.7 % lived in the West, and 0.8 % lived in Puerto Rico). For the purposes of this analysis, we report on the subsample that provided full data on our variables of interest (N = 1,487). We provide a brief description of the sample’s sociodemographic characteristics in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of participants’ and states’ characteristics

| Mean (SD)/N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Individual-level data (N = 1,487) | |

| Age | 20.80 (1.93) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 971 (65.3) |

| Black | 133 (8.9) |

| Latino | 253 (17.0) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 57 (3.8) |

| Other race/ethnicity | 73 (4.9) |

| Sexual identity | |

| Gay | 1,373 (92.3) |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.17 (.64) |

| Self-esteem | 2.87 (.59) |

| Fatherhood aspirations (i.e., How important it would be for you to have children?) | 2.67 (1.13) |

| Not at all important | 314 (21.1) |

| A little important | 328 (22.1) |

| Somewhat important | 376 (25.3) |

| Very important | 469 (31.5) |

| State-level 2011 policy data (N = 51) | |

| Marriage equality ban | |

| Full marriage equality | 10 (19.6) |

| Partial marriage equality | 12 (23.5) |

| Banned/prohibited/unclear | 29 (56.9) |

| Joint parenting adoption ban | |

| Legal | 24 (47.1) |

| Banned/prohibited/unclear | 27 (52.9) |

| Second parent adoption ban | |

| Legal | 27 (52.9) |

| Successfully petitioned | 6 (11.8) |

| Banned/prohibited/unclear | 18 (35.3) |

Procedures

Consented participants answered a 30–45 min online questionnaire that covered assessments regarding their socio-demographic characteristics, Internet use, ideal relationship and partner characteristics, sexual behaviors, psychological well-being, and sexing behaviors. Data were protected with a 128-bit SSL encryption and kept within a firewalled university server. We acquired a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health to protect study data. Our university’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Measures

State Level Characteristics

State level variables were computed using the policies in place during our data collection.

Marriage Equality Ban

A state-level marriage equality variable was created based on law data provided by Marriage Equality USA (Marriage Equality USA 2013), who divided laws based on full, partial, and banned equality. Full equality refers to states where the definition and rights of marriage are the same for same-sex and opposite-sex couples. Partial equality consisted of states where civil union and domestic partnerships were in place and banned equality consisted of states where all forms of same-sex couple recognition were banned by law, constitution, or both. The marriage equality variables were created to correspond with the time frame in which participants completed the survey (July 2012–January 2013). We collapsed full and partial marriage equality into one variable due to small cell sizes. For purposes of the analyses, we created a dummy variable to indicate whether participants lived in a state where a marriage ban was in effect (0 = No; 1 = Yes).

Same-Sex Joint Parenting Ban

Joint parent adoption law data were collected from a brief report compiled by the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) (The Human Rights Campaign 2011). The HRC defined joint adoption as involving a couple adopting a child from the child’s biological parent(s) or adopting a child who is in the custody of the state. In the creation of joint parent adoption variables, we created a dummy variable that distinguished states where joint adoption was legal or where couples had petitioned a joint adoption successfully in some jurisdictions from states where joint adoption was prohibited or unclear. States with adoption provisions or where couples had petitioned a joint adoption successfully served as the referent group (0 = No Ban; 1 = Ban in place).

Second Parent Adoption Ban

Second parent adoption law data also came from the HRC Parenting Laws brief (The Human Rights Campaign 2011). They defined second-parent adoption as stepparent adoptions in which a person is able to adopt the child of his or her partner. We delineated between states where second parent adoption was legal or where couples had petitioned for second parent adoption successfully in some jurisdictions from states where second parent adoption was prohibited or unclear. States with second parent adoption provisions served as the referent group (0 = No Ban; 1 = Ban in place).

Individual Level Characteristics

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Respondents were asked to report their age, state of residence, sexual identity, and racial/ethnic group membership. We asked participants to report their sexual identity as gay/homosexual, bisexual, straight/heterosexual, same gender loving, MSM, or Other. Given that the majority of participants self-identified as gay, we created a dichotomous variable for sexual identity, where non-gay participants served as the referent group.

We measured race using the following categories: White/Caucasian, Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, Native American, and Other. Participants who selected more than one race (e.g., White/Caucasian and Black/African American) were grouped in a Multi-Racial category. We combined the Middle Eastern, Native American and Other Race categories given the limited number of observations in each category. For ethnicity, respondents were asked to report if they considered themselves Latino or Hispanic. Non-Hispanic/Latino participants serve as the referent group. We then created dummy variables for each race/ethnicity group, having non-Latino White/Caucasian participants serve as the referent group.

Depressive Symptoms

To ascertain depressive symptoms, participants were asked to report on a 10-item short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (Kohout et al. 1993). We selected this short form in order to limit the number of survey items and reduce participant burden. Items (e.g., “I felt that everything I did was an effort”) were scored on a 4-point scale: 1 = rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day); 4 = most or all of the time (5–7 days). The total score was calculated by reverse scoring positively worded items (e.g., “I felt hopeful about the future”) and creating a mean composite score. High scores indicated high depressive symptoms in the past week (α = .85).

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem was measured using the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg 1979). Participants responded to items (e.g., “I feel I have a number of good qualities”) on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). We created a mean composite self-esteem score, where higher scores indicated higher self-esteem (α = .88).

Fatherhood Aspirations

We presented participants a list of 13 hopes and dreams and asked to rate their importance on a 4-point scale (1 = Not at all important; 4 = Very important). For the purposes of this report, we focus on participants’ desire to have children (i.e., “Thinking about your hopes and dreams, please indicate how important it would be for you to have children”).

Data Analytic Approach

We first examined the study variables using descriptive statistics (see Table 1) and bivariate correlations (see Table 2) in SPSS 20. We then computed individual-level, multivariate regressions to explore the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and our two psychological well-being outcomes (see Table 3). This analysis allowed us to examine the overall association between these constructs, regardless of where participants lived in the country, after accounting for race/ethnicity, age, and sexual identity.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between ordinal study variables among young sexual minority men (N = 1,487)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depressive symptoms | ||||

| 2. Self-esteem | −.641*** | |||

| 3. Fatherhood aspirations | −.025 | .067** | ||

| 4. Age | −.088*** | .121*** | .017 |

p ≤.05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Table 3.

Multivariate Linear Regression examining the association between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms and self-esteem, respectively, after adjusting for age, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity

| Depressive symptoms

|

Self-esteem

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | |

| Intercept | 2.90 (.19)*** | 1.88 (.18)*** | ||

| Age | −.03 (.01)*** | −.09 | .04 (.01)* | .12 |

| Gay identified | −.10 (.06) | −.04 | .14 (.06)* | .06 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | −.14 (.06)* | −.06 | .12 (.05)* | .06 |

| Latino | .10 (.05)* | .06 | −.05 (.04) | −.03 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | −.01 (.09) | −.01 | −.10 (.08) | −.03 |

| Other race/ethnicity | −.11 (.08) | −.04 | .09 (.07) | .03 |

| Fatherhood aspirations | −.01 (.02) | −.03 | .03 (.01)* | .07 |

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Non-gay identified participants served as the referent group in the sexual identity comparisons. White participants served as the referent group in the race/ethnicity comparisons

To explore the influence of state-level policies on these relationships, we used the HLM2 command in HLM 7 (Raudenbush et al. 2011) to design a multilevel regression model. This approach allowed us to compute robust estimates by partitioning each outcome’s variance (i.e., depressive symptoms or self-esteem) by its individual (Level One) and state (Level Two) components concurrently (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). We first added the individual-level predictors into our model (i.e., age, race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and hopes about having children) and then proceeded to add level-2 variables (e.g., marriage ban, same-sex joint adoption ban, second parent adoption ban) to our model. In preliminary models (data not shown), we noted no differences between participants living in states with partial or full equality provisions regarding marriage or adoption, respectively. Consequently, for power considerations, we collapsed these categories and treated them as the referent group in our Level-2 analyses. Furthermore, our power to detect multilevel relationships is somewhat constrained by the fact that we have a fixed number of observations available at level-2 (i.e., 51 states or territories); consequently, we include statistically-significant relationships at the p < .10 in our multilevel models. Furthermore, given concerns of multicollinearity at the state-level (e.g., states that have a marriage ban are also more likely to have adoption bans), we ran each multilevel model separately for each policy. Adding the state-level predictors into our model allowed us to assess whether each policy was associated with the sample’s mean score for each psychological outcome (direct effect), and/or moderated the association between youths’ fatherhood aspirations (group mean-centered) and our two outcomes (moderating effect). As we found no support for random effects in the observed relationships, we treated all variables as fixed covariates using the robust standard error estimation.

Results

Sample Characteristics

As noted in Table 1, our sample had a mean age of 20.8 years (SD = 1.93). The racial/ethnic distribution of our sample was diverse, with two thirds of the sample self-identifying as White/Caucasian (N = 971; 65.3 %), followed by Latino/Hispanic (N = 253; 17.0 %), Black/African American (N = 133; 8.9 %), Asian/Pacific Islander (N = 57; 3.8 %), or Other (N = 73; 4.9 %). Most participants self-identified as gay/homosexual (N = 1,373; 92.3 %). In bivariate analyses (see full correlation matrix in Table 2), we found that depressive symptoms and self-esteem were correlated negatively (r = −.64; p < .001), and age was associated negatively with depressive symptoms (r = −.09, p < .001) and associated positively with self-esteem (r = .12, p < .001). Fatherhood aspirations were associated with self-esteem (r = .07, p < .01), but not with depressive symptoms or age. We observed mean differences across race/ethnicity on depressive symptoms (F(4,1482) = 3.28, p < .01), with Tukey posthoc tests identifying Latino participants as having greater depressive symptoms than Black participants (mean difference = −.23, p < .08). Participants self-identifying as gay reported greater self-esteem scores (M = 2.87, SD = .59) than those who did not identify as gay (M = 2.76, SD = .57; t = 1.19, p < .05). Further, people of color (M = 2.76, SD = 1.12) reported greater fatherhood aspirations than White participants (M = 2.63, SD = 1.13; t = 2.08, p < .05). Participants residing in a state where same-sex adoption is legal (M = 2.73, SD = 1.1) reported greater fatherhood aspirations than those who reside in states where same-sex adoption is banned (M = 2.61, SD = 1.15; t = 1.96, p < .05).

Fatherhood Aspirations and Psychological Well-Being

Depressive Symptoms

In our individual-level regression model for depressive symptoms (F(7,1479) = 3.99, p < .001), we found a negative association between age and depressive symptoms (b = −.03, SD = .01; β = −.09). Among racial groups, we found that Black participants reported less depressive symptoms than White participants (b = −.14, SD = .06; β = −.06). Latino participants reported higher depressive symptoms scores than White counterparts (b = .10, SD = .05; β = .06). Fatherhood aspirations were not associated with depressive symptoms in our individual-level regression model (see Table 3). No other demographic characteristics were associated with depressive symptoms.

Self-Esteem

In our individual-level regression model for self-esteem (F(7,1479) = 6.18, p < .001), we found a positive association between fatherhood aspirations and self-esteem scores (b = .03, SD = .01; β = .07). Age was associated positively with self-esteem scores (b = .04, SD = .01; β = .12). Gay-identified participants reported greater self-esteem scores than non-gay identified counterparts (b = .14, SD = .06; β = .06). Black participants reported greater self-esteem scores than White counterparts(b = .12, SD = .05; β = .06). No other demographic characteristics were associated with self-esteem.

LGB Bans, Fatherhood Aspirations and Psychological Well-Being

Depressive Symptoms

In our Level-1 model, we found a negative association between age and depressive symptoms (b = −.03, SD = .01; β = −.08). Gay-identified participants reported lower depressive symptoms scores than non-gay identified counterparts (b = −.10, SD = .05; β = −.15). Among racial groups, we found that Latino participants reported higher depressive symptoms scores than White counterparts (b = .10, SD = .04; β = .15). We also noted that Black participants reported less depressive symptoms than White participants (b = −.13, SD = .08; β = −.20). No other demographic characteristics were associated with depressive symptoms.

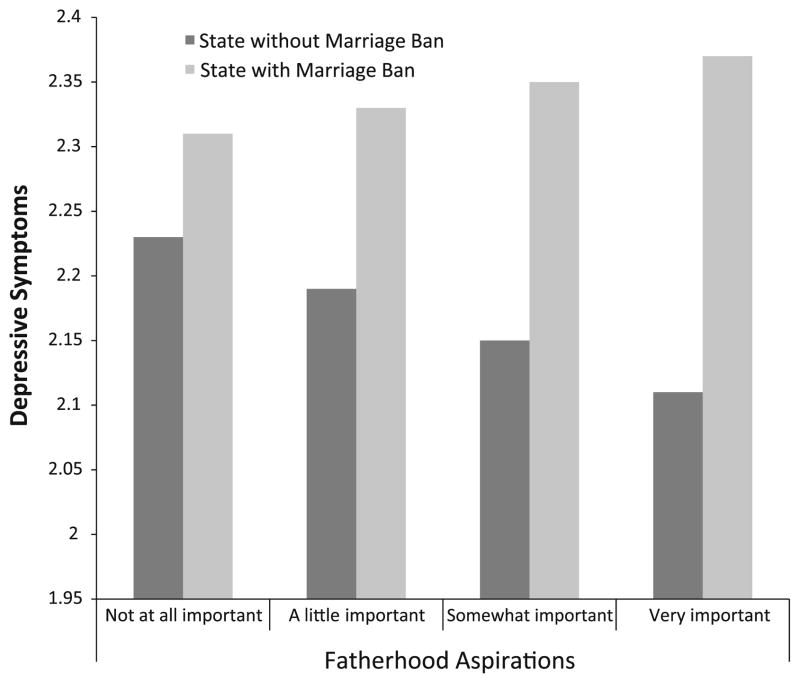

In our Level-2 model, state-level bans were not associated directly with mean depressive symptoms scores. We then sought to examine whether LGB policies influenced the association between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms. We found that living in a state with a same-sex marriage ban moderated the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms. As shown in Fig. 1, fatherhood aspirations were associated negatively with depressive symptoms among participants living in states allowing some type of same-sex marriage (b = −.04, SD = .02; β = −.08), yet were associated positively with depressive symptoms among participants living in states with a marriage ban (b = .06, SD = .02; β = .11). Joint adoption ban did not moderate the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Multilevel interaction of same-sex marriage bans on the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms among young sexual minority men in the United States

When we examined second parent adoption bans’ influence on the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms, we found no association between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms among participants living in states without second parent adoption bans (see Table 4). Conversely, we found a positive association between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms among participants living in states with a second parent adoption ban (b = .06, SD = .03; β = .10).

Table 4.

Multilevel Hierarchical Linear Model examining the association between state-level policies, fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms, respectively, after adjusting for age, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity

| Depressive symptoms | Marriage ban

|

Joint adoption

|

Second parent adoption

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | |

| Intercept | 2.27 (.06)*** | .15 | 2.26 (.06)*** | .13 | 2.25 (.06) | .13 |

| State-level policy | −.02 (.03) | −.03 | .008 (.04) | .01 | .01 (.04) | .83 |

| Age | −.03 (.01)** | −.08 | −.03 (.01)** | −.08 | −.03 (.01)** | −.08 |

| Gay identified | −.10 (.05)† | −.15 | −.10 (.05)† | −.15 | −.10 (.05)† | −.15 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | −.13 (.08)† | −.20 | −.13 (.08)† | −.21 | −.13 (.08)† | −.21 |

| Latino | .10 (.04)* | .15 | .10 (.04)* | .15 | .10 (.04)* | .15 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | −.01 (.07) | −.01 | −.01 (.07) | .01 | −.01 (.07) | .01 |

| Other race/ethnicity | −.10 (.07) | −.16 | −.10 (.07) | −.16 | −.10 (.07) | −.16 |

| Fatherhood aspirations | −.04 (.02)* | −.08 | −.03 (.02) | −.04 | −.03 (.02) | −.05 |

| State-level policy | .06 (.02)* | .11 | .03 (.03) | .05 | .06 (.03)† | .10 |

Non-gay identified participants served as the referent group in the sexual identity comparisons. White participants served as the referent group in the race/ethnicity comparisons

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Self-Esteem

In our Level-1 model, we found a positive association between age and self-esteem scores (b = .04, SD = .01; β = .11). Gay-identified participants reported greater self-esteem scores than non-gay identified counterparts (b = .13, SD = .06; β = .22). participants reporting greater self-esteem scores than White counterparts (b = .11, SD = .07; β = .19). No other demographic characteristics were associated with self-esteem.

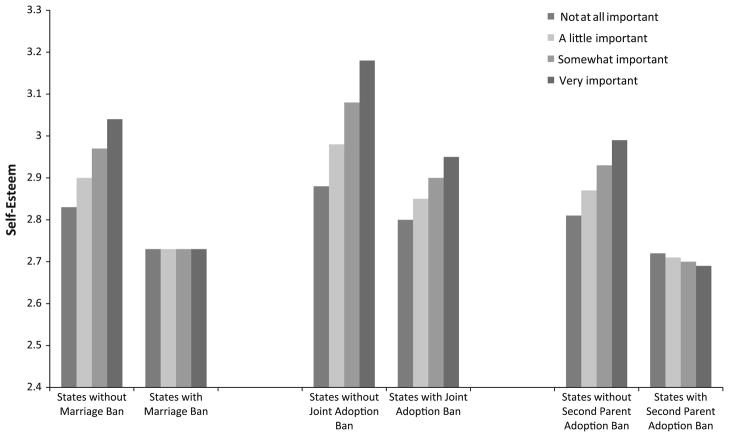

In our Level-2 model, state-level bans were not associated directly with mean self-esteem scores (see Table 5). As hypothesized, however, state-level bans moderated the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and self-esteem. In the model examining the presence of a marriage ban (see Fig. 2), fatherhood aspirations were associated with more self-esteem among participants living in states allowing some type of same-sex marriage (b = .07, SD = .02; β = .14); however, this association was in the opposite direction for young men living in states with a marriage ban (b = −.07, SD = .03; β = −.14).

Table 5.

Multilevel hierarchical linear model examining the association between state-level policies, fatherhood aspirations and self-esteem, respectively, after adjusting for age, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity

| Self-esteem | Marriage ban

|

Joint adoption

|

Second parent adoption

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | |

| Intercept | 2.76 (.06)*** | −.18 | 2.78 (.08)*** | −.19 | 2.75 (.06)*** | −.19 |

| State-level policy | −.03 (.04) | −.05 | −.03 (.04) | −.05 | −.02 (.04) | −.04 |

| Age | .04 (.01)*** | .11 | .04 (.01)*** | .11 | .04 (.01)*** | .11 |

| Gay identified | .13 (.06)* | .22 | .13 (.06)* | .22 | .13 (.06)* | .22 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | .11 (.07)† | .19 | .11 (.07)† | .19 | .11(.07)† | .18 |

| Latino | −.06 (.04) | −.10 | −.06 (.04) | −.09 | −.06 (.04) | −.09 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | −.08 (.07) | −.13 | −.08 (.07) | −.13 | −.08 (.07) | −.13 |

| Other race/ethnicity | .09 (.07) | .15 | .09 (.07) | .16 | .09 (.07) | .15 |

| Fatherhood aspirations | .07 (.02)** | .14 | .10 (.05)* | .11 | .06 (.02)** | .11 |

| State-level policy | −.07 (.03)* | −.14 | −.05 (.03)† | −.09 | −.07 (.03)** | −.14 |

Non-gay identified participants served as the referent group in the sexual identity comparisons. White participants served as the referent group in the race/ethnicity comparisons

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Fig. 2.

Multilevel interaction of same-sex marriage and parenting bans, respectively, on the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and self-esteem among young sexual minority men in the United States

When analyzing the multilevel model of joint adoption (see Fig. 2), fatherhood aspirations were associated with more self-esteem in states allowing joint adoption (b = .10, SD = .05; β = .11), whereas we saw a decrease in the strength of this association in those states that did not allow joint adoption (b = −.05, SD = .03; β = −.09).

Finally, in the model examining bans on second parent adoption (see Fig. 2), we found that fatherhood aspirations were associated with more self-esteem among those in states allowing second parent adoption (b = .06, SD = .02; β = .11). Among participants in states banning second parent adoption, however, we found that fatherhood aspirations were associated negatively with self-esteem (b = −.07, SD = .03; β = −.14).

Discussion

Recent cultural changes have increased the acceptance of same-sex relationships in the United States (Herek 2009) and led to policy shifts regarding LGB rights (e.g., the repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act; DOMA). Alongside these social changes, researchers have noted how sexual minority men’s fatherhood aspirations have also become more common in the United States (Berkowitz and Marsiglio 2007; Goldberg et al. 2012). Consistent with prior findings (D’Augelli et al. 2008), the majority of our participants reported that it would be important to have children in the future; over half of the sample (56.8 %) reported that their fatherhood aspirations were somewhat or very important to them. These findings are particularly salient as prior studies have noted that adolescents and emerging adults who are able to envision their future are more likely to benefit from greater psychological well-being and engage in a greater number of health promotive behaviors (Bauermeister et al. 2012; Bauermeister 2012; Burrow and Hill 2011; Elkington et al. 2011; Stoddard and Garcia 2011; Stoddard et al. 2011; Valle et al. 2006; Weis and Ash 2009). In conceptualizing important life events (e.g., coming out, marriage, children), however, it is important to recognize how structural barriers (e.g., LGB policy bans) may create barriers affecting sexual minority youths’ ability to achieve their future aspirations.

Individuals must have the ability to consider their future aspirations as feasible and/or to transform their aspirations into reality; otherwise, they may be more likely to experience hopelessness and report increased psychological distress (Snyder et al. 2002). Consistent with this assertion, we found that individuals who ascribed greater importance to their fatherhood aspirations reported greater psychological well-being if they lived in states without same-sex marriage or adoption bans. If participants lived in states with restrictive LGB policies, however, the protective influence of fatherhood aspirations reversed and became a risk correlate of psychological distress. In other words, participants who lived in states with restrictive LGB policies and who had assigned greater importance to their fatherhood aspirations reported a greater number of symptoms of psychological distress. These findings are consistent with mounting evidence documenting increased psychiatric disorders among LGB populations living in states where policies banning LGB equality (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2010; Riggle et al. 2009; Rostosky et al. 2009), and consistent with prior research arguing that social contexts may hinder or optimize the influence of intrinsic motivation on psychological health (Ryan and Deci 2000).

Each LGB policy ban had a different relationship to fatherhood aspirations and psychological well-being. In our depressive symptoms models, only statewide differences in marriage equality and second parenting adoption policies seemed to influence the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms. On the other hand, all three policies influenced men’s fatherhood aspirations in our self-esteem models. These divergent findings across outcomes may be attributable to the fact that fatherhood aspirations are linked conceptually to individuals’ self-concept, of which self-esteem is a component, whereas the influence of these policies on the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and depressive symptoms may be linked more distally through unexamined mediational pathways including, but not limited to, lower self-esteem and/or greater experiences of sexuality-related stigma and stress. At present, however, these interpretations remain untested and require further empirical scrutiny. Nevertheless, we believe that our findings serve as preliminary evidence to suggest that each policy influences sexual minority young men’s fatherhood aspirations and/or their psychological well-being differently. Future qualitative and quantitative research examining how these different processes emerge across different discriminatory policies is warranted.

We observed no direct association between LGB policies and our psychological indicators. Although this finding may seem to counter nationally representative evidence by (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2009, 2010), it may be attributable to study-specific issues including the types of policies examined (e.g., hate crime and employment protections, marriage, adoption), the temporal differences associated with participant recruitment and evaluation of state-policies (i.e., 2005 vs. 2012), the diverse psychological measures used in our studies (e.g., presence of psychiatric disorders vs. psychological symptoms), and each study’s respective sample composition (i.e., non-institutionalized US adults vs. single sexual minority emerging adults) and representativeness (i.e., nationally representative vs. convenience sample), respectively. As a result, our findings may not necessarily counter those previously observed by Hatzenbueher et al. (2009, 2010) and should not be used as a comparison. Rather, our findings serve to provide supplementary insight regarding how LGB discriminatory policies may moderate the relationship between fatherhood aspirations and psychological well-being among young sexual minority men.

Several additional limitations in our study also deserve mention. First, the majority of our sample identified as gay or bisexual, such that our findings may not be generalizable to sexual minority men who do not claim these identities. Second, although our study includes young men from most states and territories in the United States, it does not necessarily constitute a representative sample of sexual minority emerging adult men within each state nor may it be generalizable due to endogeneity bias (i.e., individuals may not be able to self-select into their communities of choice). Third, our survey focused on single young men. As a result, it is possible that men in other age groups and/or who are in relationships may have different parenting aspirations (Riskind and Patterson 2010) and greater psychological well-being (Riggle et al. 2010). Fourth, we employed a cross-sectional design, limiting our ability to make causal arguments regarding the observed relationships. Furthermore, we rely on self-report data which may be influenced by social desirability. The measurement of fatherhood aspirations as a single-item may also influence our findings; we encourage future research to examine how fatherhood aspirations may vary based on different scenarios and contexts. Finally, additional individual factors (e.g., whether participants’ are openly out and supported by family and peers) and state policies (e.g., surrogacy policies) may influence the observed relationships, warranting future exploration in subsequent studies.

The limitations above notwithstanding, our study has several strengths. First, we include a large, racially/ethnically diverse sample of young sexual minority men living across the United States. Furthermore, we were able to carry out multilevel models to examine the association between statewide policies and psychological well-being of sexual minority young men, while adjusting for the nested nature of these data. This approach is particularly meaningful as it suggests that discriminatory policies may “get under our skin” by “getting into our hearts”, eroding naturally existing resilience in sexual minority populations.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings underscore the importance of recognizing how anti-equality LGB policies may influence the fatherhood aspirations and psychosocial development of young sexual minority men. Statewide same-sex marriage and parenting bans may influence young sexual minority men’s fatherhood aspirations and, in turn, erode the protective influences that hopes have on psychological well-being. Undoubtedly, some sexual minority young men may decide not to pursue their parenting aspirations in the future; other men may decide to enact their fatherhood aspirations yet face roadblocks due to policies that ban same-sex partnerships and/or prohibit surrogacy or adoptive children. Under these constraints, individuals who place greater importance on their future expectations may also report greater psychological distress. Policy and advocacy initiatives to ensure LGB equality and inclusiveness are warranted as public health strategies. These initiatives may influence not only psychological well-being, but also promote the resilience of sexual minority populations.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health Career Development Award to Dr. Bauer-meister (K01-MH087242).

Biography

Jose A. Bauermeister is the John G. Searle Assistant Professor in Health Behavior and Health Education and Director of the Center for Sexuality and Health Disparities (SexLab) at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health. His primary research interests focus on sexuality and health, and interpersonal prevention and health promotion strategies for high-risk adolescents and young adults. He is Principal Investigator of several projects examining risk and resilience among sexual minority youth, and Co-Investigator of several studies examining adolescent and young adults well-being. Dr. Bauermeister is member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Youth and Adolescence, AIDS and Behavior, Archives of Sexual Behavior, and Health Education & Behavior.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

Author contributions Dr. Bauermeister designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

References

- Arnett J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgett M. Money, myths and change: The economic lives of lesbians and gay men. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA. Romantic ideation, partner-seeking, and HIV risk among young gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41(2):431–440. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9747-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Pingel E, Zimmerman M, Couper M, Carballo-Dieguez A, Strecher VJ. Data quality in HIV/AIDS web-based surveys: Handling invalid and suspicious data. Field Methods. 2012;24(3):272–291. doi: 10.1177/1525822X12443097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz D, Marsiglio W. Gay men: Negotiating procreative, father, and family identities. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(May):366–381. [Google Scholar]

- Burrow AL, Hill PL. Purpose as a form of identity capital for positive youth adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(4):1196–1206. doi: 10.1037/a0023818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli A, Rendina HJ, Sinclair K, Grossman A. Lesbian and gay youth’s aspirations for marriage and raising children. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2008;1(4):77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Drumright LN, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Club drugs as causal risk factors for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men: A review. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41(10–12):1551–1601. doi: 10.1080/10826080600847894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Do parents and peers matter? A prospective socio-ecological examination of substance use and sexual risk among African American youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34(5):1035–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates TG. Why employment discrimination matters: Well-being and the queer employee. Journal of Workplace Rights. 2011;16(1):107–128. doi: 10.2190/WR.16.1.g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ, Badgett MV, Macomber JE, Chambers K. Adoption and foster care by lesbian and gay parents in the United States. CA: Los Angeles: 2007. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE, Downing JB, Moyer AM. Why parenthood, and why now? Gay men’s motivations for pursuing parenthood. Family Relations. 2012;61(1):157–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurmankin AD, Caplan AL, Braverman AM. Screening practices and beliefs of assisted reproductive technology programs. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;83(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(5):707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Social factors as determinants of mental health disparities in LGB populations: Implications for public policy. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2010;4(1):31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: A conceptual framework. Contemporary Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identities. 2009;54:65–111. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09556-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993;5(2):179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaletta PR, Oliver JM. The hope construct, will, and ways: Their relations with self-efficacy, optimism, and general well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55(5):539–551. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199905)55:5<539::aid-jclp2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallon J. Gay men choosing parenthood. New York: Columbia University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marriage Equality USA. Marriage Equality State-by-State. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.marriageequality.org/Marriage Equality State-by-State.

- Patterson CJ. Children of lesbian and gay parents: Psychology, law, and policy. American Psychologist. 2009;64(8):727–736. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.64.8.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabun C, Oswald RF. Upholding and expanding the normal family: Future fatherhood through the eyes of gay male emerging adults. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research and Practice about Men as Fathers. 2009;7(3):269–285. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk A. Advanced quantitative techniques in the social sciences series. 2. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2002. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush A, Bryk A, Congdon R. HLM 7 for Windows. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS, Horne SG. Marriage amendments and lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in the 2006 election. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2009;6(1):80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle ED, Rostosky SS, Horne SG. Psychological distress, well-being, and legal recognition in same-sex couple relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(1):82–86. doi: 10.1037/a0017942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS, Prather RA, Hamrin R. The execution of legal documents by sexual minority individuals. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2005;11(1):138–163. [Google Scholar]

- Riskind RG, Patterson CJ. Parenting intentions and desires among childless lesbian, gay, and heterosexual individuals. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(1):78–81. doi: 10.1037/a0017941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riskind RG, Patterson CJ, Nosek BA. Childless lesbian and gay adults’ self-efficacy about achieving parenthood. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice. 2013;2(3):222–235. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Riggle ED, Horne SG, Miller AD. Marriage amendments and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Russell GM, Richards JA. Stressor and resilience factors for lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals confronting antigay politics. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(3–4):313–328. doi: 10.1023/a:1023919022811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR. Conceptualizing, measuring, and nurturing hope. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1995;73:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Feldman DB, Taylor JD, Schroeder LL. The roles of hopeful thinking in preventing problems and enhancing strengths. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2000;9:249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Rand KL, King EA, Feldman DB, Woodward JT. “False” hope. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58(9):1003–1022. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Garcia CM. Hopefulness among non-U.S.-born Latino youth and young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2011;24:216–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2011.00307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Zimmerman MA, Bauermeister JA. Thinking about the future as a way to succeed in the present: A longitudinal study of future orientation and violent behaviors among African American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(3–4):238–246. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9383-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Te Riele K. Philosophy of hope: Concepts and applications for working with marginalized youth. Journal of Youth Studies. 2010;13(1):35–46. [Google Scholar]

- The Human Rights Campaign. Parenting. Human Rights Campaign; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.hrc.org/issues/parenting. [Google Scholar]

- Valle MF, Huebner ES, Suldo SM. An analysis of hope as a psychological strength. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44(5):393–406. [Google Scholar]

- Weis R, Ash SE. Changes in adolescent and parent hopefulness in psychotherapy: Effects on adolescent outcomes as evaluated by adolescents, parents, and therapists. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009;4(5):356–364. [Google Scholar]