Abstract

Objective

Interventions directed at the mental health of family dementia caregivers may have limited impact when focused on caregivers who have provided care for years and report high burden levels. We sought to evaluate the mental health effects of problem-solving therapy (PST), designed for caregivers of individuals with a recent diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or early dementia.

Method

Seventy-three (43 MCI and 30 early dementia) family caregivers were randomly assigned to receive PST or a comparison condition (nutritional education). Depression, anxiety, and problem-solving orientation were assessed at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post intervention.

Results

In general, the PST caregiver intervention was feasible and acceptable to family caregivers of older adults with a new cognitive diagnosis. Relative to nutritional education, PST led to significantly reduced depression symptoms, particularly among early dementia caregivers. PST also lowered caregivers’ anxiety levels, and led to lessening of negative problem orientation.

Discussion

Enhanced problem-solving skills, learned early after a loved one’s cognitive diagnosis (especially dementia), results in positive mental health outcomes among new family caregivers.

Keywords: Problem-solving therapy, early family dementia caregiving, early dementia, mild cognitive impairment

The societal burden associated with dementia is significant now and will become even more so by mid century. Estimates suggest that as many as 5.4 million persons in the United States currently have dementia, a number that is projected to rise to 11 to 16 million by the year 2050.1 In 2011, more than 15 million family members provided an estimated 17.4 billion hours of unpaid care, worth an estimated $210.5 billion, to people with dementia.1 Yet the breadth and magnitude of these costs cannot be reckoned solely in economic terms.

Among the chief costs of providing care to a person with dementia are depression and anxiety among family caregivers.2–5 Such consequences have negative implications for the mental health of our nation, given the rising rates of persons afflicted with dementia and the increasing number of “informal” caregivers.6 Despite the pragmatic, long-term health care policy issues that serve as the impetus for research in this arena,7–9 psychosocial interventions evaluated to date have been only moderately effective at improving mental health outcomes of family caregivers.10–15

One reason for the limited impact of these interventions may lie in their focus on caregivers who have already served in the caregiving role for an extended period of years and who report high levels of caregiving burden. Indeed, the effectiveness of caregiving interventions declines as levels of pre-intervention burden increase,14 particularly in spousal dementia caregivers.15 Although some level of burden must be present in order for caregivers to be motivated to participate in caregiver interventions, an alternative strategy would be to offer family members an intervention designed to prevent the development or worsening of depression and anxiety symptoms while their burden levels are relatively low. Thus, interventions to promote adaptive coping related to the caregiving situation may positively affect the mental health of family members if they are offered relatively early in the caregiving trajectory.

Preventive interventions to stem depression and anxiety and to improve adaptive coping may also be relevant for family members of persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Individuals with MCI have a 10%–12% annual probability of progressing to a dementia disorder16–18 and studies show that co-residing family members of persons with MCI report concerns about anticipated responsibilities as they transition into the caregiving role.19,20 Although caregiver burden and psychiatric morbidity levels were lower than those typically observed in family dementia caregiving samples, preliminary work suggests that MCI caregivers have already begun to experience elevated caregiving burden.19 Thus, family members of persons with MCI and early dementia may both be at an optimal phase (early caregiving) for testing the effects of an intervention designed to prevent depression and anxiety.

We sought to evaluate the mental health effects of a self-management intervention based on problem-solving therapy (PST) principles specifically designed for relatively new family caregivers. Both randomized prevention trials and epidemiological modeling suggest that prevention of depression in later life may be most efficiently accomplished by targeting persons who experience risk factors but are not highly distressed,21 and systematic reviews of the literature22–25 show that PST is effective in preventing depression in high-risk populations (indicated prevention). For new family caregivers, we posit that their key risk factor for depression is the new burden they are beginning to experience in the wake of their loved one’s cognitive impairment. PST, however, has not been adapted and examined for its potential impact on depressive symptoms in the context of caregiving for family members with a new diagnosis of cognitive impairment.

Our decision to utilize PST is based on the stress and coping literature, because one’s appraisal of a stressful event is crucial in determining the outcome of coping reactions, including the quality of the consequent affective response.26 Individuals’ expectations concerning their ability to effectively resolve problems may determine whether they actually do cope successfully with stressful events.27 PST is based on a problem-solving model of stress,28 and may be particularly useful for promoting self-efficacy among family caregivers. PST has the potential to reduce the impact of a variety of caregiving stressors (e.g., bothersome behaviors) through increased awareness and use of effective problem solving, ultimately enhancing family caregivers’ self-efficacy when applying newly learned skills along the caregiving trajectory. We hypothesized that enhanced problem-solving skills, learned early after their loved one’s cognitive diagnosis of MCI or dementia, would result in lower depression and anxiety symptoms in family caregivers.

METHODS

Participants

The University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) patient registry was searched for all cases diagnosed with MCI in the 6 months before the start of data collection and new cases of MCI or early dementia (any type) diagnosed at the ADRC during the subsequent 46-month time frame. To be eligible, potential participants had to live with the person with the new ADRC MCI or early dementia diagnosis (clinical dementia rating29 of 0 to 1.5) in a community (non-institutional and non-assisted) setting, live within a 300-mile radius of Pittsburgh, and be able to understand English.

Design

We used a two-group (PST versus comparison condition), pretest–post-test, randomized (1:1) design with assessments at baseline (T1), and at 1 month (T2), 3 months (T3), 6 months (T4), and 12 months (T5) post-intervention by an independent evaluator who was not blind to treatment group assignment. A computer-generated random assignment sequence was developed using permuted blocks. Study personnel did not have any contact with or knowledge of prospective participants prior to random assignment to treatment groups.

Procedures

Overview

After providing written informed consent and baseline data, participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental intervention, based on the principles of PST (PST-MCI/ AD caregiving), or to an attention-control condition, which focused on providing education about nutrition (NT). The interventionists were social workers and separate interventionists administered the PST and NT protocols to prevent cross-contamination. Participants received two phases of treatment; the first phase involved six sessions conducted in the caregiver’s home approximately 2 weeks apart, each lasting approximately 1.5 hours. The second phase included three telephone contacts (approximately 2 weeks apart) to reinforce principles taught during the first phase, each lasting approximately 45 minutes.

Experimental intervention: PST-MCI/AD caregiving

This protocol focuses on training in adaptive problem-solving attitudes and skills.28 It was adapted from the work of Areán and colleagues,30,31 who developed a manualized protocol for PST use in primary care. Our adaptation sought to enhance problem-solving skill levels of family caregivers as they began to face a variety of potential caregiving stressor.

During the first session, participants received written and verbal education about: 1) the structure of sessions; 2) MCI or dementia and the family caregiving role; 3) the link between problems, overwhelming stress, and symptoms of depression or anxiety; 4) the relationship between low mood and reduced pleasurable activities (activity scheduling); and 5) the rationale for problem-solving training. These five topic areas were only discussed in the first session.

In subsequent sessions, participants received written instructions and coaching in the systematic application of PST, which include: 1) writing a clear description of the problem; 2) setting a realistic goal; 3) brainstorming solutions; 4) listing pros and cons of each solution; 5) choosing a solution; 6) developing an action plan; and 7) evaluating progress. Together, the participant and interventionist completed the seven steps to solving at least one problem together before beginning the second phase of the intervention. Participants were asked to keep a record of their problem-solving efforts between sessions and questions they had related to the application of PST. These records were used as a basis for discussion during both phases of the intervention.

PST-MCI/AD caregiving training and treatment fidelity

The PST-MCI/AD interventionist was given a detailed treatment manual, attended a workshop on the principles of PST-MCI/AD, and role-played the intervention with the Principal Investigator before training participants. For purposes of ongoing consultation and treatment fidelity, all training sessions were audio-taped for random review by the Principal Investigator. Adherence to the PST-based protocol was assessed throughout the study using the Problem Solving Treatment Provider Adherence Checklist31 when listening to audio-taped sessions. The PST-interventionist demonstrated 98% adherence (SD: 2.6) across rated sessions to items on the Checklist.

Comparison intervention: nutritional training (NT)

The comparison intervention was based on the United States Department of Health and Human Services “2005 My Pyramid Dietary Guidelines for Americans over Age 50.” We chose a nutrition-based comparison intervention because information about dietary practices is not likely to affect mental health outcomes. The NT intervention was matched to the PST-based intervention in terms of number and duration of sessions.

During the first session, participants received written and verbal education about: 1) the structure of the sessions; 2) MCI or dementia; and 3) an overview of the Dietary Guidelines. Participants also completed a questionnaire about their current eating practices32 and activity level. In the second session, together the participant and interventionist determined which Food Pyramid (based on age and activity level) was right for the participant (e.g., 1,200 calorie) and discussed principles of healthy eating. The second session concluded with a discussion about the Food Portion Guide. In subsequent training sessions, the interventionist provided education related to the major food categories, discretionary calories, and tips and resources for menu planning. Participants were asked to keep a record of menu planning, eating habits between sessions, and any questions they had related to the application of NT. These records were used as a basis for discussion during both phases of the intervention.

NT training and treatment fidelity

The NT interventionist was also given a treatment manual and reviewed the intervention with the Principal Investigator before working with participants. The NT interventionist demonstrated an average of 99% adherence (SD: 4.5) across rated sessions to items in the NT protocol. The NT interventionist avoided conversations about exercise, because changes in the participant’s activity level could impact the outcomes of interest.

Measures

Outcomes

Depression symptom level was the primary study outcome. Anxiety and problem-solving orientation were secondary outcomes.

Depressive symptoms were measured with Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D).33 Twenty items are each rated on a four-point scale. Items are summed (higher scores indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms). In the present sample, internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) was 0.91.

Symptoms of anxiety were measured using the State portion of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).34 The STAI is a self-report 20-item questionnaire with items rated on a four-point scale. Items are summed, with higher scores indicating higher anxiety symptom levels. Cronbach’s α was 0.94 in the present sample.

Problem solving was assessed with the Social Problem Solving Inventory – Revised: Short Form,35 which assesses two dimensions of problem-solving orientation and three styles of problem solving. Because the problem orientation dimensions have been found to be important in other samples of relatively new family caregivers36 (e.g., caregivers to persons with recent-onset spinal cord injury) and in the treatment37–39 and prevention of depression,25,39 we focused on them, rather than on problem-solving styles. A positive problem orientation (PPO) is the extent to which an individual appraises a problem as solvable and believes in one’s ability to solve problems successfully. In contrast, a negative problem orientation (NPO) reflects extent to which an individual appraises a problem as unsolvable or doubts one’s ability to solve problems successfully.35 Higher PPO and NPO scores indicate a stronger positive or negative problem orientation. Cronbach’s α was 0.60 for the PPO subscale and 0.73 for the NPO subscale.

Participant characteristics

Additional information was collected to characterize the sample, including caregiver demographics, relationship to the patient, years in the relationship, number of cohabitants in household, number of illnesses that limit activities, and caregiver cognitive status using the Mini Mental State Exam.40

Program acceptability

Program acceptability was evaluated by examining rates of agreement to enroll in the study and responses to three questions asked at the exit interview: 1) understanding the purpose of the intervention (using a visual analog scale; range: 0–10); 2) suggestions for improving the study (open-ended question); and 3) a willingness to participate in future family caregiver studies.

Analysis

The PST-MCI/AD and NT groups were compared on baseline subject characteristics with χ2 tests and independent-sample t-tests. Using an intention-to-treat approach, we performed a repeated-measures linear mixed effects analysis for each of our study outcomes. This analysis included group assignment (PST-MCI/AD caregiving versus NT) and type of caregiver (MCI versus dementia) as between-subjects factors, and time (baseline, 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up) as a within-subjects factor. The depression and anxiety data were log-transformed for analysis and p values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Feasibility/Acceptability

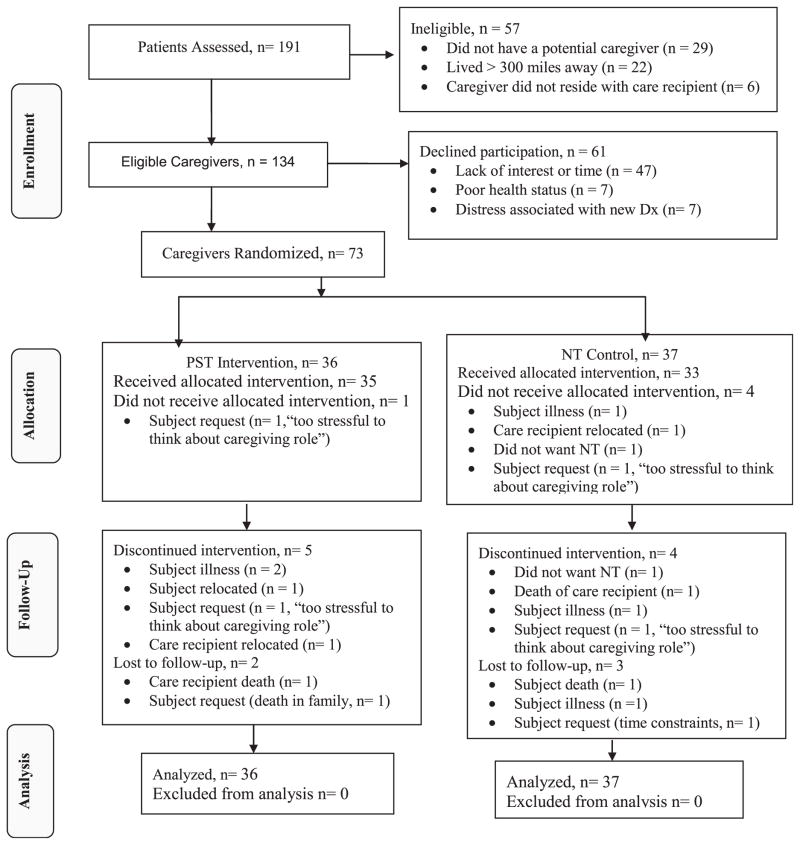

During the recruitment period (February 1, 2007 to December 30, 2010), 191 individuals received a new ADRC diagnosis of MCI or early dementia. Of the 191 ADRC patients identified, 70% had an eligible caregiver. Of these caregivers, 54% enrolled and were randomized. The final sample of 73 participants consisted of 43 new MCI and 30 new family caregivers. Of these, 5 (6.8%) did not receive an intervention, 9 (12.3%) dropped out during the intervention phase of study, and 5 (6.8%) discontinued participation during the follow-up phase. This resulted in a total of 19 participants (26%) being lost to attrition (see Fig. 1 for details). Our recruitment and retention rates are consistent with rates obtained in other intervention studies among dementia family caregivers.41,42

FIGURE 1. Consort flow chart.

Note: *Schulz, Altman & Moher for the CONSORT Group, 2010. Dx = ADRC cognitive diagnosis, PST = Problem Solving Therapy, NT = Nutritional Training

All of the participants completing the study verbalized some type of “appreciation” for the training received and there were no significant differences on exit interview responses between subjects receiving PST or NT. Participants endorsed a relatively high level of understanding the purpose of the intervention received (average score of 8.5 on a 10-point scale), nearly three quarters (71%) had no suggestions for improving the study, and 91% asked to be notified of future family caregiver studies. Suggestions for improving the study (29%) revolved around several themes: 1) wanting a longer intervention (follow-up monthly for one year to indefinitely), shorter follow-up data collection sessions (1.5 hours maximum), and more education related to MCI and dementia.

Study Sample

The sample was an average age of 65 years old (refer to Table 1). At baseline, participants in the PST group were more likely to be spousal caregivers (75%) and to live alone with the care recipient. Other demographic and background characteristics were similar among caregivers in the two intervention conditions. The sample was well educated, with half having a college degree. They were cognitively intact but the majority reported that they themselves had health conditions leading to impairments in daily activities. Although 83% of the sample reported that their income was sufficient to meet their expenses, more than half of the sample continued to work and 17% of the sample was struggling financially.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 73 Family Caregivers, N (%) or M (±SD)

| Caregiver Characteristics | Total Sample (N = 73) | PST Group (N = 36) | NT Group (N = 37) | Statistical Testa | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI family caregiver (vs AD caregiver) | 43 (58.9) | 23 (63.8) | 20 (54.0) | 0.729 | 0.292 |

| Age in years (sample range = 27–84 yrs old) | 64.98 (11.3) | 66.4 (8.0) | 63.4 (13.7) | 1.13 | 0.261 |

| Female sex | 57 (78.1) | 28 (77.7) | 29 (78.3) | 0.004 | 0.951 |

| Caucasian | 72 (98.6) | 35 (97.2) | 37 (100) | 1.04 | 0.307 |

| College degree | 39 (53.4) | 19 (52.7) | 20 (54) | 0.012 | 0.913 |

| Spousal caregiver | 55 (75.3) | 31 (86.1) | 24 (64.8) | 4.43b | 0.035 |

| Years in relationship with care recipient (sample range: 3–60 years) | 34.8 (17.3) | 32.8 (17.4) | 36.7 (17.3) | 0.971 | 0.335 |

| Lives alone with care recipient | 24 (32.8) | 30 (83.3) | 21 (56.7) | 6.12b | 0.013 |

| Income, above $40,000 | 58 (79.4) | 32 (88.8) | 26 (70.2) | 2.53 | 0.112 |

| Income is adequate to meet expenses | 61 (83.5) | 33 (91.6) | 28 (75.6) | 3.39 | 0.065 |

| Caregiver employed | 41 (56.2) | 18 (50.0) | 23 (62.1) | 1.09 | 0.295 |

| MMSE score (sample range: 25–30) | 29.4 (1.2) | 29.7 (.7) | 29.2 (1.5) | 1.80 | 0.074 |

| Have illness that limits activities | 42 (57.5) | 17 (47.2) | 25 (67.5) | 3.09 | 0.079 |

| Depression level (CES-D) | 10.08 (10.0) | 8.7 (9.3) | 11.4 (10.6) | 1.49 | 0.255 |

| Anxiety level (STAI) | 28.84 (10.1) | 28.1 (10.3) | 29.5 (10.1) | 0.57 | 0.567 |

| Positive Problem Solving (PPO) | 102.40 (12.73) | 103.97 (12.31) | 100.86 (13.11) | 1.043 | 0.301 |

| Negative problem orientation (NPO) | 94.14 (10.65) | 94.00 (10.81) | 95.27 (10.60) | 0.507 | 0.614 |

| Care Recipient Characteristics | |||||

| Age in years (sample range: 57–97) | 75.2 (8.8) | 74.1 (9.2) | 76.2 (8.4) | 1.022 | 0.310 |

| Female sex | 26 (35.6) | 12 (33.3) | 14 (37.8) | 0.161 | 0.688 |

| Care recipient employed | 37 (50.6) | 15 (41.6) | 22 (59.4) | 2.31 | 0.128 |

Notes: CES-D and STAI data were log transformed prior analyses in order to reduce skewness in their distributions. Reported here are raw scores in order to facilitate interpretation. MCI: mild cognitive impairment; MMSE: Mini Mental Sate Exam; PST: problem solving training; NT: nutritional training.

Independent sample t-test statistics (df = 71) were computed for continuous data and χ2 tests (df = 1) were computed for dichotomous data, p-values are two-tailed.

p <0.05.

Table 1 also includes information on the care recipients. A majority of care recipients were men and nearly 60% had a diagnosis of MCI. With an average age of 75 years, it is interesting to note that nearly half of the cognitively impaired care recipients were employed. No significant differences were found among care recipients based on the treatment group assignment of their caregiver.

Depression Levels

Because the mixed effects analyses assume that missing data are ignorable, we evaluated the potential for bias related to participant attrition from the study before conducting analyses of intervention effects. We found no differences in baseline characteristics, outcomes, or group assignment between participants with complete follow-up data versus those who discontinued study involvement during the intervention phase of the study (Fig. 1). Thus, we assumed the missing data were ignorable in the present data set. At baseline, depression scores were three points higher among subjects in the NT group. Both groups had depression scores well below cut points for clinical depression (16–23), the difference in scores was not statistically significant, and there is no evidence that a three-point difference in CES-D scores is clinically significant.33

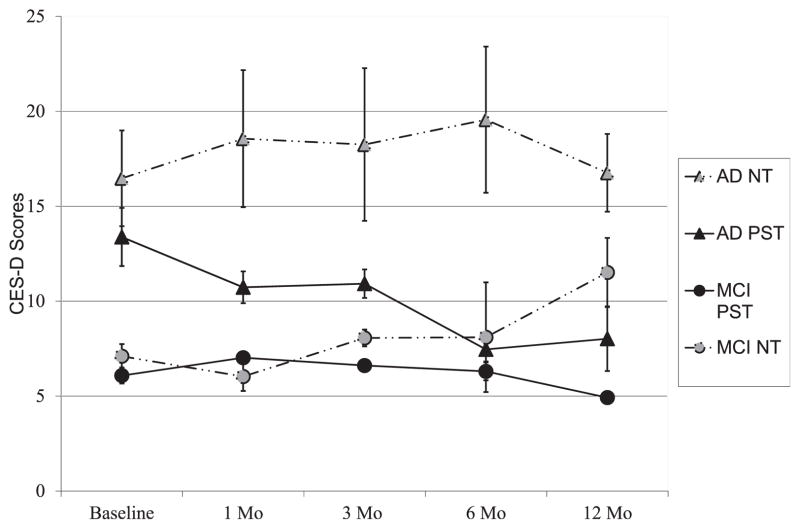

Results of the mixed effects analysis for depressive symptoms show significant main effects for intervention group, with participants in the PST group reporting significantly lower symptom levels (across all follow-up time points) than participants in the NT group (Table 2, Fig. 2). There was also a main effect for type of caregiver, with MCI caregivers endorsing significantly lower depression levels than dementia caregivers.

TABLE 2.

Effects of Treatment Group, Time, and Type of Caregiver on Depression, Anxiety, and Problem Orientation using Linear Mixed Models Analysis

| Depression

|

Anxiety

|

Positive Problem Orientation

|

Negative Problem Orientation

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | df | p | F | df | p | F | df | p | F | df | p | |

| Treatment group (PST vs NT) | 5.508a | 1,64 | 0.022 | 5.82a | 1,56 | 0.019 | 2.718 | 1,65 | 0.100 | 2.927 | 1,68 | 0.092 |

| Type of caregiver (MCI vs AD) | 10.750b | 1,64 | 0.002 | 8.86b | 1,56 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 1,65 | 0.856 | 2.857 | 1,68 | 0.096 |

| Time | 0.189 | 4,52 | 0.943 | 2.38 | 4,51 | 0.063 | 0.732 | 4,4,7 | 0.574 | 0.632 | 4,54 | 0.642 |

| Treatment group by type of caregiver | 1.961 | 1,64 | 0.166 | 4.57a | 1,56 | 0.036 | 0.692 | 1,65 | 0.408 | 0.205 | 1,68 | 0.652 |

| Treatment group by time | 2.716a | 4,52 | 0.040 | 2.44a | 4,51 | 0.058 | 1.078 | 1,47 | 0.376 | 5.632b | 4,54 | 0.001 |

| Time by type of caregiver | 1.218 | 4,52 | 0.314 | .508 | 4,51 | 0.730 | 0.417 | 1,47 | 0.796 | 0.487 | 4,54 | 0.745 |

| Treatment group by time by type of caregiver | 4.394b | 4,52 | 0.004 | 2.25 | 4,51 | 0.076 | 0.535 | 1,47 | 0.205 | 0.372 | 4,54 | 0.827 |

Notes: Depression and anxiety data were transformed for analyses. PST: problem solving training; NT: nutritional training; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; AD: dementia.

p <0.05 (two-tailed).

p <0.01 (two-tailed).

FIGURE 2.

Effects of treatment group, time, and type of caregiver on depression levels (mean, SE; CES-D scores).

In support of the study hypotheses, we found not only a significant interaction between intervention group assignment and time (indicating that PST versus NT-groups’ depression levels changed at different rates over time), but a significant interaction between intervention group, type of caregiver, and time. This three-way interaction indicated that there were group differences over time and these differences varied depending on the type of caregiver. Namely, depression levels of MCI caregivers in the PST-group remained relatively stable over time, while depression levels of MCI caregivers in the NT-group rose during the 1-year follow-up period. The opposite was true for new dementia caregivers: Those in the PST-group showed reductions in depression levels over time while dementia caregivers in the NT-group were high and remained stable over time (Fig. 2). This is important because it shows that depression can be prevented or treated relatively early in the caregiving trajectory, when caregiving burden is relatively low.

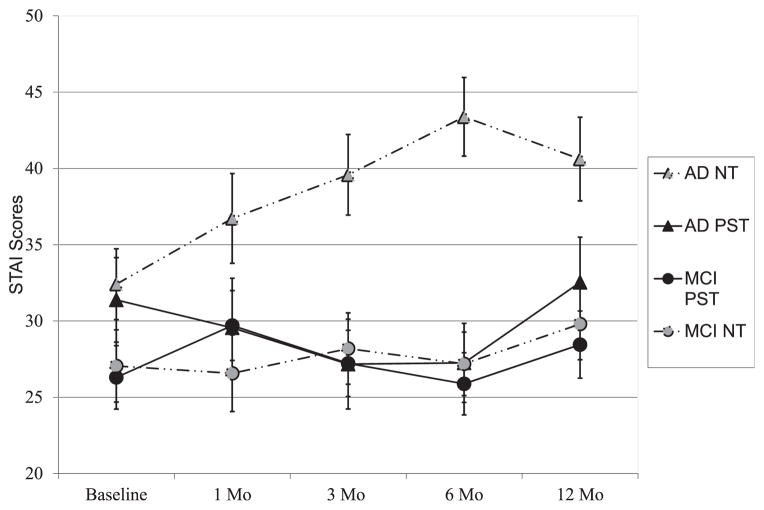

Anxiety Levels

Participants in the PST-group also reported significantly lower mean anxiety levels than participants receiving the NT intervention. There was also a main effect for type of caregiver, with MCI caregivers endorsing significantly lower anxiety levels than dementia caregivers. A significant treatment group by type of caregiver interaction and a treatment group by time interaction also emerged. In general, the PST intervention appeared to have little impact on anxiety levels of MCI caregivers. In contrast, dementia caregivers that received the PST intervention showed relatively stable anxiety levels over time while dementia caregivers in the NT-group showed rising levels of anxiety over time (Table 2, Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of treatment group, time, and type of caregiver on anxiety levels (mean, SE; STAI-state scores).

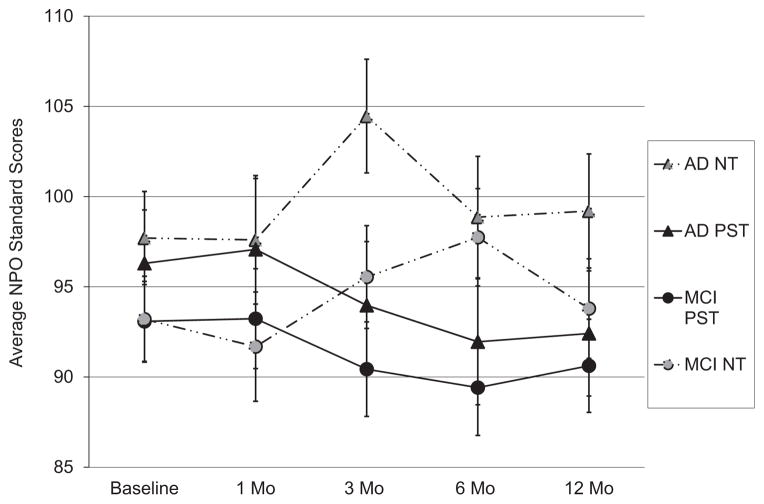

Effects on Problem-solving Orientation

Lastly, we found a significant treatment group by time interaction effect on participants’ NPO scores. Participants assigned to the PST group endorsed lower NPO scores over time, whereas NPO scores of caregivers in the NT group generally increased over time (see Table 2, Fig. 4). We did not find significant main effects for PPO scores or a significant three-way interaction (treatment group by time by type of caregiver) for PPO or NPO scores.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of treatment group, time, and type of caregiver on negative problem orientation scores (mean, SE; SPSI total standardized scores).

Although Table 1 showed that the PST and comparison group differed in the proportion of spouse caregivers and caregivers living alone with the care recipient, the inclusion of these factors in additional mixed model analyses did not affect the findings reported here.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to test a mental health intervention for family caregivers of persons with cognitive deficits who are relatively early in the dementia caregiving trajectory. Our results suggest that depression symptoms can be prevented or reduced when PST is taught to these caregivers, and that impact was stronger for dementia family caregivers than for MCI caregivers. The PST intervention appeared to have a protective effect on MCI caregivers’ depression levels in that it kept them from rising, as compared to MCI caregivers in the NT group. In contrast, the PST intervention appeared to reduce the dementia caregiver depression levels while depression levels of dementia caregivers in the NT group remained relatively elevated.

PST appears to have positive effects on depression levels of new family caregivers to individuals with traumatic brain injury43 and caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation.44 Because the current study showed that PST is useful for decreasing depressive symptoms among family caregivers of a loved one with new diagnosis of MCI or dementia, the timing of the PST intervention may be important for family caregivers. In the current study, symptoms of depression were prevented (in MCI caregivers) or reduced (in dementia caregivers) when PST is taught soon (within 6 months) after receiving an ADRC cognitive diagnosis.

PST also had beneficial effects on caregivers’ anxiety levels. Although we did not find evidence that this effect was stronger in dementia versus MCI caregivers, inspection of the data shows a trend suggesting that PST’s impact was more pronounced in dementia caregivers. The effect for anxiety is an encouraging because community-dwelling older adults who endorse anxiety symptoms often progress to depression or depression with generalized anxiety disorder.45

Caregivers in the PST group showed significant improvements in NPO scores over the course of the study. This effect, however, is largely due to a decline in NPO scores among the dementia caregivers (Fig. 4). It is possible that changes in NPO scores mediate (or predict) changes in depression scores in relatively early family caregivers. To this point, Elliott et al. found that NPO explained significant variation in the rates of change in depression and anxiety levels among family caregivers of persons with recent spinal cord injury.36 Further, a higher NPO is associated with more negative mood and an inability to regulate negative emotions.46 It is possible that family caregivers with a higher negative orientation to problems may have difficulty managing their own emotions while simultaneously managing caregiving demands. When these problems are unresolved over time, pessimistic beliefs about caregiving abilities (lack of self-efficacy) may be reinforced, exacerbating distress (i.e., depression) levels over time.46

Overall, the PST-MCI/AD caregiver intervention was feasible and acceptable to family caregivers of older adults with a new cognitive diagnosis. We were able to recruit a sufficient pool of subjects to conduct an initial evaluation of the PST intervention and the interventions were delivered consistently and practicably to study participants in their home.

Several limitations of the study must be considered. Although our study captured individuals earlier in the illness trajectory than prior dementia caregiving studies, even our sample had already entered the process of coping with cognitive impairment by the time of enrollment and we did not have information on length of caregiving. Other limitations are the relatively small size and racial composition of the sample: We enrolled a predominantly white sample, with only one African American participant. This introduces potential limitations on generalizability to the population of family caregivers of persons with newly diagnosed MCI or dementia. Our use of the Registry enhanced the study’s internal validity because it ensured that all individuals were carefully diagnosed with MCI or dementia. Reliance on the Registry, however, also potentially limits the external validity of the results because such individuals (family caregivers of individuals who have sought a research diagnosis and treatment for their cognitive complaints) may differ from individuals and their family caregivers who have not consulted an ADRC. It is also possible that family members who enrolled in this study were more challenged by their new caregiving role than persons not interested in enrolling. Additionally, the generalizability of our findings are reduced by our focus on family caregivers who reside with the individual with cognitive impairment. We chose to focus on family members residing with the care recipient (compared to caregivers living elsewhere), however, because we felt they would be at greater risk for experiencing burden (and possibly depression) associated with the caregiving role. Lastly, the results may be biased because the study was too small to allow for use of independent evaluators who were blind to treatment group assignment.

In sum, this study showed that the PST-MCI/AD intervention is feasible, acceptable to MCI and relatively early dementia family caregivers, and shows positive effects on their mental health outcomes. Specifically, the PST-based intervention had a protective effect on depression levels of MCI family caregivers (i.e., prevented them from developing depression symptoms) and a positive treatment effect on dementia family caregiver’s depression levels (i.e., lowered their initially high levels of depression). The PST-based training also had a positive overall effect on caregivers’ anxiety levels, and this primarily occurred among dementia caregivers. Because depression and anxiety symptoms are serious consequences of family dementia caregiving,3 and the prevalence of dementia is projected to rise in the near future,1 such interventions show promise for the mental health of the nation’s informal caregivers, as family members provide long-term, home-based care to loved ones with dementia. Exploring the influence of a negative problem orientation on depression outcomes in family dementia caregivers is an important area for future investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (MH070719, P50 AG05133, P30 MH090333, and UL1RR024153) and the UPMC Endowment in Geriatric Medicine.

Footnotes

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00321971.

The authors have no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association: Report. 2012 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(2):131–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergman-Evans B. A health profile of spousal Alzheimer’s caregivers: depression and physical health characteristics. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1994;32:25–30. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19940901-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, et al. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causes. Gerontologist. 1995;35:771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz R, Visintainer P, Williamson GM. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of caregiving. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1990;45:P181–P191. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.5.p181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijeratne C. Review: pathways to morbidity in carers of dementia sufferers. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9:69–79. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Advisory Panel on Alzheimer’s Disease. Progress Report on Alzheimer’s Disease: Taking the Next Steps. Silver Springs, MD: Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral (ADEAR) Center; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ. Reducing Risks For Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventative Intervention Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Mental Health. NIMH: Envisioning A World In Which Mental illnesses Are Prevented and Cured. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer BH, Ryff CD. New Horizons in Health: An Integrative Approach. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acton GJ, Kang J. Interventions to reduce the burden of caregiving for an adult with dementia: a meta-analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24:349–360. doi: 10.1002/nur.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourgeois MS, Schulz R, Burgio L. Interventions for caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a review and analysis of content, process, and outcomes. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1996;43:35–92. doi: 10.2190/AN6L-6QBQ-76G0-0N9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooke DD, McNally L, Mulligan KT, et al. Psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5:120–135. doi: 10.1080/713650019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knight BG, Lutzy SM, Macofsky-Urban F. A meta-analytic review of interventions for caregiver distress: recommendations for future research. Gerontologist. 1993;33:240–248. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein H, et al. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42:356–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58B:P112–P128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.p112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luck T, Luppa M, Briel S, et al. Incidence of mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29(2):164–175. doi: 10.1159/000272424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopmen DS, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: ten years later. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(12):1447–1455. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yesavage JA, O’Hara R, Kraemer H, et al. Modeling the prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:281–286. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garand L, Dew MA, Eazor LR, et al. Caregiving burden and psychiatric morbidity in spouses of persons with mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:512–522. doi: 10.1002/gps.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIlvane JM, Popa MA, Robinson B, et al. Perceptions of illness, coping, and well-being in persons with mild cognitive impairment and their care partners. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(3):284–292. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318169d714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds CF, III, Cuijpers P, Patel V, et al. Early intervention to reduce the global health and economic burden of major depression in older adults. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:123–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cole MG. Brief interventions to prevent depression in older subjects: a systematic review of feasibility and effectiveness. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:435–443. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318162f174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Problem solving therapies for depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Smit F, et al. Preventing the onset of depressive disorders: A meta-analytic review of psychological interventions. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(10):1272–1280. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07091422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sriwattanakomen R, Ford AF, Thomas SB, et al. Preventing depression in later life: translation from concept to experimental design and implementation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:460–468. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318165db95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nezu AM, Perri MG. Social problem-solving therapy for unipolar depression: an initial dismantling investigation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(3):408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;40:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arean PA, Perri MG, Nezu AM, et al. Comparitive effectiveness of social problem-solving therapy and reminiscence therapy as treatments for depression in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:1003–1010. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hegel MT, Dietrich AJ, Seville JL, et al. Training residents in problem-solving treatment of depression: a pilot feasibility and impact study. Fam Med. 2004;36:204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millen BE, Brown LS, Levine E. Continuum of nutrition services for older Americans, in Geriatric Nutrition: The Health Professionals Handbook. In: Millen BE, Brown LS, Levine E, Burlington MA, editors. Jones Bartlett Learning. 3. 2006. pp. 4777–518. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R) North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elliott TR, Shewchuk RM, Richards JS. Family caregiver social problem solving abilities and adjustment during the initial year of the caregiving role. J Couns Psychol. 2001;48:223–232. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell AC, D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Schutte NS. The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Jongsma J, et al. Online cognitive behavioral therapy and problem-solving therapy for depressive symptoms: exploring mechanisms of change. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2010;41:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallagher-Thompson D, Lovett S, Rose J, et al. Impact of psychoeducational interventions on distressed family caregivers. J Clin Geropsychol. 2000;6:91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Hays JC, et al. Identifying, recruiting, and retaining seriously ill patients and their caregivers in longitudinal research. Palliat Med. 2006;20:745–754. doi: 10.1177/0269216306073112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivera PA, Elliott RT, Berry JW, et al. Problem-solving training for family caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grant JS, Elliott TR, Weaver M, et al. Telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation. Stroke. 2002;33:2060–2065. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020711.38824.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schoevers RA, Deeg DJ, van Tilburg W, et al. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: co-occurrence and longitudinal patterns in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:31–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nezu AM, D’Zurilla TJ. Social problem solving and negative affect. In: Kendall P, Watson D, editors. Anxiety and Depression: Distinctive and Overlapping Features. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 285–315. [Google Scholar]