Abstract

Although research has identified a number of qualities and competencies necessary to be an effective exercise leader, the fitness industry itself is largely unregulated and lacks a unified governing body. As such, a plethora of personal trainer certifications exists with varying degrees of validity that fail to ensure qualified trainers and, therefore, protect the consumer. It is argued that the potential consequences of this lack of regulation are poor societal exercise adherence, potential injury to the client, and poor public perception of personal trainers. Additionally, it is not known whether personal trainers are meeting the needs of their clients or what criteria are used in the hiring of personal trainers. Thus, the purpose of this investigation was to examine the current state of personal training in a midsized Southeast city by using focus group methodology. Local personal trainers were recruited for the focus groups (n = 11), and the results from which were transcribed, coded, and analyzed for themes using inductive reasoning by the authors. Qualities and characteristics that identified by participants clustered around 4 main themes. Client selection rationale consisted of qualities that influenced a client’s decision to hire a particular trainer (e.g., physique, gender, race). Client loyalty referred to the particular qualities involved in maintaining clients (e.g., motivation skills, empathy, social skills). Credentials referred to formal training (e.g., college education, certifications). Negative characteristics referred to qualities considered unethical or unprofessional (e.g., sexual comments, misuse of power) as well as the consequences of those behaviors (e.g., loss of clients, potential for litigation). These results are discussed regarding the implications concerning college programs, certification organizations, increasing public awareness of expectations of qualified trainers, and a move towards state licensure.

Keywords: qualifications, certifications, credentials, education, licensure

Introduction

Despite the well-documented physical and psychological health benefits associated with regular physical activity, American adults remain strikingly sedentary. Current estimates suggest that 38% of adults report no physical activity in their leisure time (7). Consequently, the number of overweight people in the United States has increased in recent years, with 65% of adults being overweight (13), Furthermore, a recent study estimated that a lack of physical activity results in $24 billion annually, or 2.4% of U.S. health expenditures, and obesity is responsible for $70 billion in direct costs (8). Of those that do adopt an exercise program, it is estimated that 50% will discontinue it within the first 6 months (11). Thus, it is clear that exercise adherence is a primary health care issue. However, although exercise adherence research has identified a number of determinants as well as several theoretical models to explain the adoption and maintenance of exercise behavior (17), few findings have had an impact in applied exercise settings.

Interestingly, a consistent finding in the exercise adherence literature that may have important implications for applied exercise settings is the influence of the exercise leader. Specifically, McAuley and Courneya (18) argued that the exercise leader can potentially influence each of the 4 sources of self-efficacy (mastery experiences, social modeling, social persuasion, and physiological or emotional states) (3) and potentially increase exercise adherence. However, few studies have systematically investigated exercise leader behaviors or the qualifications required to be an effective fitness leader. One recent study (12) examined the characteristics of motivational leaders of physical activity groups for older adults. Results showed that older adults responded best when leaders exhibited competency to lead exercise, treated the participants as individuals, and demonstrated the ability to foster social interaction between members in the class. Thus, as evidence accumulates documenting the importance of the exercise leader to exercise behavior, it is important to understand the qualities that make effective exercise leaders.

Recognizing the importance of effective exercise leaders, a number of certification programs exist to educate and ensure qualified exercise leaders. Idea Personal Trainer magazine identified 19 different certifications available to the public (15). These range from the highly rigorous American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) Health Fitness Instructor, which is based on extensive scientific data, involves course work pre-requisites to taking the exam as well as a 4-day intensive lecture and practical workshop prior to the exam, to lesser-known agencies, such as the Future Fit certified personal trainer in which there are no pre-requisites and the exam consists of information developed by the “chief executive officer of Future Fit and two advisors” (15).

However, the vast number of certifying organizations indicates a lack of consensus within the field regarding credentials required to be a professional exercise leader (i.e., personal trainer). Essentially, all one has to do to become a “certified” trainer is to pay a fee, take an exam, and most fitness facilities will hire the individual regardless of the type of certification. As with most commercial industries, the quality of the product is often positively related to the cost. Thus, the lower-cost certification programs often lack the rigor and validity of the more expensive programs, such as ACSM and the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) program. However, because the industry is not regulated, fitness facilities are not obligated to hire staff possessing any specific type of certification or license and will typically hire low-cost personal trainers when possible. The ultimate consequence is the potential for low-quality exercise leaders practicing in fitness facilities and the subsequent potential effects on the consumer: lack of proper instruction, negative physical activity experience, injury, and the negative health effects associated with low adherence (e.g., obesity prevalence).

Most certifying organizations agree that important exercise leader competencies should include, beyond basic scientific anatomy, biomechanics, and exercise physiology knowledge, (a) lifestyle and health, (b) chronic disease (e.g., cardiovascular disease), (c) exercise programming, (d) program management, (e) health behavior modification, and (f) nutritional advice (1,14). All of these services require training and keeping current with new research; otherwise, injury, ineffective programs, and client drop-out can result. However, it is unknown to what degree these qualities are practiced in community fitness facilities. Furthermore, very little research exists investigating the skills/qualities needed to be an effective exercise leader, particularly from the perspective of practicing personal trainers. Thus, this study asked practicing exercise leaders what qualities and credentials they thought were important to be effective, successful personal trainers using a phenomological, grounded theoretical approach and focus group methodology.

Methods

Approach to the Problem

The study consisted of focus groups to examine the overarching question, “What qualities are important to be a successful personal trainer?” The investigators used inductive reasoning and interpretive analysis, meaning that themes were drawn from the data without comparing it to a guided theory (10). Global themes, major themes, and subthemes were selected from the transcriptions. Evidence of credibility, reliability, and trustworthiness was provided in several ways. First, 3 different readers were used, bringing their varying perspectives to the group. Furthermore, the data presented here represents consensus reached via thorough discussions among individuals with expertise in personal training, exercise physiology, health behavior, and qualitative research methods. Additionally, as a member check, the investigators sent a one-page summary to the participants and asked for feedback and any clarifications and/or additions they would like to make.

Subjects

Subjects included 11 personal trainers (M age = 36 years old; range 22 to 50 years old). 54.5% of the participants were Caucasian (n = 6).With respect to gender, 36% (n = 4) of the trainers were women, and the majority had at least a college education (n = 9). In terms of having a certification, all of the trainers had some type including: 27% (n = 3) of the trainers had the Aerobics and Fitness Association of America (AFAA) certification, 27% (n = 2) had the International Fitness Professional’s Association (IFPA) certification, and 27% (n = 2) had both the ACSM and NSCA certifications. With regards to the numbers of years the participants had been personal training, the majority of the trainers had been in the business for 4–9 years (n = 7).

Focus Groups

Focus groups were recorded with the use of a Marantz audio-recording system and videography (60 hz). In addition to the informed consent, participants also signed a confidentiality agreement within the group. The confidentiality statement included the investigator’s agreement not to disclose names, as well as the participants’ agreement not to disclose or discuss what was said in the interviews with other participants or individuals outside the designated focus group time. Furthermore, anonymity was ensured by removing participants’ names on the final transcripts, and by replacing real names with aliases. A moderator’s guide, (24) was used in each of the focus groups. The focus groups lasted approximately 2 hours with an emphasis on each participant getting equal amounts of speaking time (24).

Procedures

The first author recruited all participants through personal invitation. Volunteers were mailed a packet that included (a) a demographic information sheet, including name, address, age, occupation, education, and credentials questions; (b) an informed consent form, explaining that the participants would be video- and audio-taped during the focus groups; and (c) a list of the questions that would be discussed for the participant to reflect on prior to the meeting. Having the questions beforehand allowed the participant to consider the specific questions ahead of time, organize their thoughts, and expedite the focus group discussion.

Statistical Analysis

The focus group audio tapes were transcribed verbatim. The 3 investigators read and re-read each of the 3 transcripts and searched for key phrases emerging from the data. Key phrases were defined as those that occurred at least 5 times within the transcript, as the 3 investigators concurred that this arbitrary number was sufficient to denote a key phrase. After meeting numerous times, the investigators converted the key phrases into codes. The investigators then examined the transcripts line by line, inserting the codes where appropriate. After consensus was reached concerning the coding of each line of transcript, the codes were entered into Ethnograph©, a computer program used for qualitative data analysis.

Results

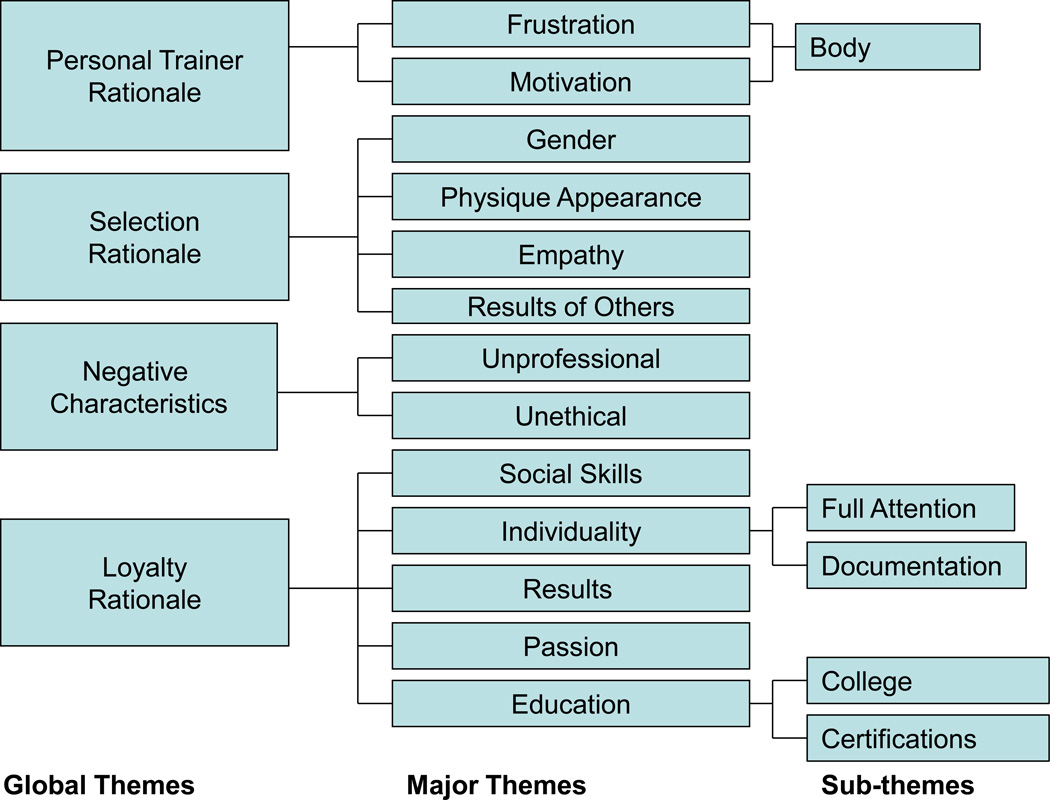

Figure 1 illustrates the hierarchical organization of the data into global, major, and subthemes that were derived from the personal trainers’ responses. The global themes include client selection rationale, client loyalty, credentials, and negative characteristics. The next 2 levels, the major and subthemes, depict the details of the global themes.

Figure 1.

Hierarchy of themes.

Client Selection Rationale

Client selection rationale represents the trainers’ notions of what characteristics clients look for when they want to hire a trainer. These characteristics represent trainers’ perceptions of client knowledge and values regarding the trainer before hiring him/her. The major themes subsumed under this global theme were physique appearance, gender/race, niche, and referral.

The participants agreed that the appearance of one’s physique was a critical consideration for clients hiring a personal trainer. When asked how much of an influence a trainer’s physique has on a client in choosing his/her trainer, one trainer replied: “I think it’s, unfortunately, it’s huge. I think it’s a very big deal just because I’ve talked to so many people who have, you know—I work out in a gym where there are a lot of trainers. I don’t work there, but there are a lot of different trainers and I had so many people say, ‘I’m going to go to her because she looks great’ or ‘I wouldn’t go to him because he doesn’t look that great’.”

The trainers also reported that gender and race may interact with the trainer’s physique, resulting in various outcomes. One trainer commented, “And I thin—Peter made a point of mentioning dark-skinned, buff gentlemen training people—and I think I was, if I’m not mistaken, the first dark-skinned personal trainer as an independent [contractor]. I’m not sure. It was difficult getting started at first. Some people had some preconceived notions, maybe, of what to expect. After a few months, however, I was able to get some respect in there.” This trainer felt that being a large, fit, muscular, African-American male was intimidating to some people and possibly aversive to business.

However, although trainers agreed that the trainer’s physique, as well as gender and race, largely plays a factor for first impressions, they also agreed that more informed clients look beyond the physical shape and rely on other factors in the decision-making process. More specifically, trainers often believed that their specific niche often attracted clients. “It’s important. It depends on the niche. It depends on the client…Now if somebody’s coming in to make a serious transformation in their bodies, they’re well suited to find a trainer who has transformed his body and others’ [bodies] as well. A lot of times, you may have some of your geriatric, rehab-type clients. It’s important that the trainer look fit, again, but it depends on the client’s specific goals”. Thus, our trainers felt that some participants seek trainers that are uniquely suited to fit their specific needs.

Referral is the last major theme that emerged with client selection rationale and included the trainers’ conviction that word-of-mouth is an important part of their business and that clients use this information when choosing a particular trainer. “They look at your clients more than they look at you, to be quite honest with you. Your clients will definitely talk, and that’s the best thing that can help you right there- your sales. Word of mouth is the A-number one advertisement.” Much like many other professions, the personal trainer industry appears to be a referral business.

Client Loyalty

A second global theme that emerged from the data was client loyalty, which refers to the particular qualities a trainer should have to maintain clients and be successful. Client loyalty consists of the lower level major themes of motivational skills, individuality, empathy, and social skills. Motivational skills were defined as the ability to inspire a client to continue exercising with the trainer, including giving words of encouragement, building self-efficacy, maintaining positive attitudes, and making clients accountable for their sessions. The trainers agreed that one of the main reasons that clients continue to hire a particular personal trainer is because they find the motivation to exercise very difficult to achieve. One participant noted, “I see a lot of times, a lot of people get personal trainers because they’re bored and they can’t motivate themselves. You have to be a motivator, like he said, but you have to have a conversation with them…I’ve been able to share and have them tell me about their family and whatever and they’ll work harder when they get that relationship.”

Individuality represents the degree to which the trainer is able to make the client feel unique and cared for through listening skills and friendship. One trainer stated, “I’d much rather get results. But at the same time, if [the clients] don’t have a husband to listen, they don’t have any kids in the family, basically all they have is their work, then you become their best friend, pretty much. And they look forward to seeing you once or twice a week, or three times a week. So you basically become more than just a trainer to these people.”

Similar to individuality, the trainers believed that successful trainer must be empathetic. Empathy, refers to the ability to put one’s self in the client’s position, to not merely understand the difficulties the client may have as s/he tries to achieve his/her goals, but to actually feel what the client feels. One female client noted, “just appreciating the fact that they’re there comes from a depth of understanding of what the physical things that they’re having to go through in order to get into shape, and have empathy for them because you understand it from a cellular level, and also just to really appreciate that person for being there. I think that people are smart enough to know when you’re just there for the money, if you’re there because you think they’re great for just going through what they’re going through.” As with individuality, empathy can only occur through active listening, attending to the client, and relationship building.

The last major theme under client loyalty is social skills. Social skills are the ability to effectively interact and communicate with a diverse clientele. Such interaction may be the result of personality traits, such as extraversion, being friendly and outgoing; a “people person.” “Personality is huge. I mean, I’ve seen [clients] stay with [trainers] with, you know, they’re caring, considerate. They have them do the worst exercises! They’re wasting their time, talking about the movie they saw last night while [the clients are] doing their triceps press-downs, but they love working with them because-they’re not really interesting in having a trainer and getting results—but they know they’re going to see their friend for $35 an hour.”

Credentials

The third global theme that emerged from the personal trainers’ focus group was Credentials. Credentials included 2 major themes: a formal college education and certifications. Education refers to any discussion of degrees or formal classes obtained from an institution of higher education. The consensus seemed to be that a college education, especially one with a science focus, is needed to acquire the requisite base knowledge for successful personal training. One male participant provided an example of this belief: “I agree with education having an important role in the success of a personal trainer. I would like to think that a 4-year biology degree, or definitely a 4-year science degree would definitely expose you to anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, etc. And of course, from there, that’s a good foundation from which to build upon and study more into kinesiology, exercise physiology, etc…‥Not to say that a guy with an accounting degree [can’t be successful], ‘cause I know some successful trainers with a business or accounting degree who’ve been able to…but I think it’s important that a trainer have a 4-year degree, with an emphasis in science especially.”

However, although the consensus was that formal higher education is critical, the participants were also dissatisfied with current programs. The trainers acknowledged the value of practical knowledge, critically examined typical undergraduate fitness leadership curricula, and offered several suggestions to improve undergraduate programs. “I think in the degree field, we missed it. We have all this background on anatomy and physiology, but we didn’t have anything on basic gym management. How to run a gym, how to open up a gym, how to start with groundwork, how to go get your business license, how to balance your books, how to do all of these things—because these are things I think a lot of [trainers] are missing. I got my management experience from leaving the field and going to work for my father in construction for a year…I didn’t get that in school.”

The discussion of education led to fitness leader certification. Certifications concerned references to any organization that offered some sort of fitness education, an exam, and “official recognition.” As with college programs, the trainers had reservations regarding the various organizations that offer such recognition. “I personally don’t believe everyone must have a certification from this or that organization. And I have certifications from ACSM and NSCA, and if I never took those exams, I don’t think I’d be any better or any worse of a trainer just because I have that piece of paper saying that I’m certified.” Participants noted that no organization offers a complete certification examination that assures that a potential trainer knows how to design programs for a diverse population of clients. “One of the things that I see that a lot of the certifications don’t go into, and a lot of these trainers don’t know, is how to design a program, how to design a nutrition program’there’s a lot people that are skilled in telling you how to do this exercise. That’s great, and every trainer should know how to do that, how to execute an exercise properly, what muscles it’s working…but a good trainer, and your more successful trainers, know how to design a program. That’s an art. That’s not covered in any certification that I’ve seen…that is overlooked, the importance of that ability.”

Not surprisingly, the discussion of college and certifications led to a subtheme entitled licensure, which refers to the trainers’ contention that there should be one standard required of all personal trainers to be eligible to practice, and that this standard should be modeled after professionals such athletic trainers and massage therapists. “If the state of training could lead towards developing a certification similar to a licensure to practice PT (physical therapy), or nursing, or a registered dietician exam…I can call myself that only because I have a “degree” and then, not necessarily just a degree, but I passed the licensure exam so I have that certificate. So there’s one standard by which everyone had to go by. And it could be a very involving examination, involving not just written, but also practical information, practical knowledge, etc. that really needs to be known if a person want to practice personal training at that type of level.”

Negative Characteristics

The final global theme for personal trainers was labeled negative characteristics. Negative characteristics included the major themes of unethical and unprofessional. Unethical behavior included sexual comments and inappropriate touching, as well as misused power (e.g. selling nutritional items solely for extra income). One trainer was adamant about not touching clients: “Male trainers, especially, need to conduct themselves respectfully around women—no flirting. I don’t touch my clients. There’s a lot of trainers who do…I mean, I’ve seen some trainers who do excessive touching, male trainers to female trainers. I don’t think its necessary and I think it sends the wrong message to onlookers.”

The trainers also mentioned that they have witnessed many unprofessional trainers, which included characteristics such as punctuality, attitudes, respect, and attention to clients. “I see it a lot. A [trainer] may not be attentive to their client, as simple as that. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen trainers who are watching TV instead of paying attention to their clients. But that’s beyond ethics. That’s completely just unprofessional.” In addition, the trainers saw “fly-by-nighters,” or those who are not truly dedicated to the personal training profession, yet want to earn “quick money,” as unprofessional.

Consequences, a subtheme under negative characteristics, refer to the potential outcomes that may result from of incompetent personal trainers, which are, according to the trainers in this study, injury and bad reputation. Injury was discussed in terms of incompetent trainers doing incorrect exercises or allowing a client to use incorrect form that led to an injury. One trainer took injury a step further and stated that lawsuits could result from injuries caused by a trainer not watching correct form on an exercise: “Lawsuits. If you have a poor trainer and they don’t know how to do correct spotting techniques and you get an injury, well, it’s the trainer’s fault, or whoever they’re working for. That’s a lawsuit. Just like in any other business. Doing surgery, you mess up, that’s it. There’s more than just saying ‘Oh, I feel bad, I’m sorry.’ It’s just a whole liability issue.” Moreover, possibly an even larger issue with the personal trainers was getting a bad reputation due to these incompetent trainers. The trainers were concerned that these incompetent trainers would cause the public to view all trainers as incompetent, thereby resulting in an overall loss of business.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine personal trainers’ perceptions of the qualities needed to be successful in the personal trainer industry using focus group methodology. Four global themes emerged from the data indicating that important personal trainer qualities reflect client selection rationale, client loyalty, education, and negative characteristics. Additionally, these global themes were divided into major and sub-themes.

Participants distinguished between the characteristics that attracted clients to trainers prior to hiring (client selection rationale) and characteristics that kept a client with a trainer (client loyalty). In light of the importance of physical appearance in the fitness industry (16,21), it is not surprising that selection rationale characteristics included superficial variables such as physique appearance, gender, and race. However, participants also mentioned referral and niche, indicating more informed choices on the part of clients. Interestingly, characteristics representing client loyalty were unique from client selection rationale and included skills involving interpersonal, motivational, and social skills. Clearly, the ability to fully attend to the client, empathize, and make them feel unique was important to our participants.

Ironically, the characteristics representing client loyalty are not taught in exercise science curricula or certification programs. Exceptions include the ACSM Resource Manual (1), which provides basic instruction on motivational skills, and the ACE certification exam, which contains items on interpersonal/social skills. The knowledge and skills that are gained from formal education were not mentioned as being important for either selection rationale or client loyalty. This may be because the participants take that basic knowledge and skills for granted and did not think it was necessary to discuss in that context. Furthermore, although participants agreed that education and certification was important and necessary, they indicated that current programs lack training in weight training program design and business management. Participants also expressed a desire for some unified standard within the industry and a movement towards licensure modeling other professions, such as physical therapy.

Participants also identified a number of negative behaviors that they have observed that should be avoided. They noted that some trainers engage in inappropriate touching or flirting, double book clients and do not provide the necessary attention, have poor attitudes, abuse their power, and dispense misinformation (particularly uninformed diet advice). Participants were clearly concerned that the immediate impact of such behavior is injury to the client; however, the long term impact is poor reputation and public perception of their industry.

We must acknowledge several limitations of the present study. First, we used qualitative methods and, therefore, our results cannot be generalized to other populations. Second, although we used focus groups, our sample size was eleven, which is quite small. Third, all qualitative research is dependent on the biases of the authors that analyze the data. Although we took measures to eliminate bias (the lead author completed a bracketing interview, we had 3 authors analyze the data through consensus agreement), it is possible that preconceived beliefs regarding the qualities of personal trainers may have influenced our analysis. However, despite these limitations, we feel that the results of the present offer some important practical implications.

Practical Applications

First, we believe that undergraduate and certification programs should include formal training in interpersonal skills such as active listening, empathic communication, and behavioral strategies to enhance motivation. The findings of the present study are consistent with research has shown that using such techniques will positively influence exercise adherence (6,22,23), and participants in the current study believed clients stayed with trainers who exhibited the attributes of empathy, listening skills, and motivation skills. Indeed, Cress and colleagues (9) have recently developed best practices regarding behavioral counseling and physical activity in older adults. It is time these practices are formally incorporated into undergraduate programs.

We believe that undergraduate college curricula in fitness leadership should include practical components with internship, as well as courses in management, behavioral, and interpersonal skills directed specifically to personal trainers. The trainers in the present study with a health-related degree felt that college had prepared them with theory, but not with enough applicable knowledge. As many of the trainers in this study noted, most of their practical skills were learned on-the-job. Practical experience in interpersonally relating to clients, designing programs, and business and facility management would greatly enhance the preparedness of new personal trainers. Additionally, at least one trainer lamented that he had to learn management skills from his father because he was not required to take a class in his exercise and sport science curriculum that prepared him in such necessities as charging clients, paying taxes from a self-employed status, budgeting for equipment, and advertising. A management course specifically geared toward personal training would be beneficial to trainers beginning their careers.

Finally, the participants in the present study echo a recurrent theme within the industry regarding multiple certifications and licensure. Currently, there are at least 19 different personal trainer certification organizations available (15), and a purported 200 organizations offering fitness certifications (2). With so many organizations having their own criteria for membership and status as a personal trainer, there is no regulation or assurance that personal trainers working in the field are qualified. Other fields have recognized the problems associated with multiple standards, and have moved to one certification organization and state licensure to ensure that only those qualified may practice. For example, as of 1989, in order to practice as a certified athletic trainer (ATC), one must pass the National Athletic Trainer’s Association Board of Certification (NATABOC) exam (4). Additionally, the NATABOC has strict guidelines concerning acceptable coursework and experience hours, and supervision. Because of these strict guidelines, certified athletic training is recognized by the American Medical Association as an allied health care profession (5). Because of this distinction, the public is assured that only qualified and knowledgeable persons are able to call themselves certified athletic trainers, that there is a body of knowledge that is specific to this profession, and they enjoy the public respect associated with recognition as a profession. One non-profit organization, the National Board of Fitness Examiners, founded in 2003, has a mission to “ensure to the public that qualified fitness professionals who have successfully passed the National Board examination have achieved the approved level of competency in the health and fitness industry” (19).

According to the NSCA’s Scope of Practice for the NSCA-CPT, “Personal trainers are health/fitness professionals who, using an individualized approach, assess, motivate, educate and train clients regarding their health and fitness needs. They design safe and effective exercise programs, provide the guidance to help clients achieve their personal health/fitness goals and respond appropriately in emergency situations. Recognizing their own area of expertise, personal trainers refer clients to other health care professionals when appropriate.” (20). Because there is no regulation or assurance that personal trainers working in the field are qualified, it would be prudent for the potential client to know how to identify a competent trainer. Characteristics regarding an optimal trainer may be found in Table 1. Asking questions regarding academic background, years of practical experience, and training style, as well as getting referrals and knowing about the trainer’s personality before hiring one is strongly suggested.

Table 1.

Optimal vs. suboptimal trainers.

| Optimal trainers | Suboptimal trainers |

|---|---|

| 4-year degree in exercise science-related field | Flirts with clients |

| Certification from a nationally recognized organization | Frequently cancels appointments |

| Knowledge in basic sciences and nutrition | Not punctual |

| Able to work with a diverse group of clientele | Discusses management with clients |

| Uses behavioral strategies | Fails to dedicate full attention to client |

| Positive/supportive leadership style | |

| Strong communication skills |

We believe that results of the present study and the suggestions presented for undergraduate curricula and licensure have the potential to enhance the personal training industry. Ultimately, improving the industry has the potential to improve public perception, job security, salaries, exercise adherence, and, perhaps, public health.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the focus group participants, whose time, thoughts, and enthusiasm were invaluable to this study.

References

- 1.Kaminsky LA, Bonzheim KA, Garber CE, Glass SC. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archer S. Navigating PFT certifications. Idea Fitness J. 2004:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Board of Certification. [Accessed July 17, 2006]; Available at: http://www.bocatc.org/becomeatc/Cert/. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Board of Certification. [Accessed July 17, 2006]; Available at: http://www.bocatc.org/athtrainer/Define/. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckworth J. Exercise determinants and interventions. Int J Sport Psychol. 2000;31:305–320. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control. Prevalence of no leisure-time physical activity-35 States and the District of Columbia, 1988–2002. MMWR. 2004;53:82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colditz G. Economic costs of obesity and inactivity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:S663–S667. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cress ME, Buchner DM, Prohaska T, Rimmer J, Brown M, Macera C, Depietro L, Chodzko-Zojko W. Best practices for physical activity programs and behavior counseling in older adult populations. J Aging and Phys Act. 2005;13:61–74. doi: 10.1123/japa.13.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dishman RK. Determinants of participation in physical activity. In: Bouchard C, Shepard RJ, Stephens R, Sutton JR, McPherson BD, editors. Exercise, Fitness and Health: A Consensus of Current Knowledge. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics; 1990. pp. 78–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estabrooks PA, Munroe KJ, Fox EH, Gyurcsik NC, Hill JL, Lyon R, Rosenkranz S, Shannon VR. Leadership in physical activity groups for older adults: A qualitative analysis. J Aging Physical Activity. 2004;12:232–245. doi: 10.1123/japa.12.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flegal KM, Caroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell J, Minor SL. Health and Fitness Professions. In: Hoffman SJ, Harris JC, editors. Introduction to Kinesiology: Studying Physical Activity. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics; 2000. p. 462. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Idea Personal Trainer. 2000. Nov-Dec. Evaluating personal trainer certifications; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobi L, Cash TF. In pursuit of the perfect appearance: Discrepancies among self ideal percepts of multiple physical attributes. J Appl Social Psychol. 1994;24:379–396. [Google Scholar]

- 17.King AC, Stokols D, Talen E, Brassington GS, Killingsworth R. Theoretical approaches to the promotion of physical activity: forging a transdisciplinary paradigm. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(Suppl 2):15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mcauley E, Courneya KS. Adherence to exercise and physical activity as health-promoting behaviors: Attitudinal and self-efficacy influences. Appl Prev Psychol. 1993;2:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Board of Fitness Examiners. [Accessed July 10, 2006]; Available at: http://www.nbfe.org/about/. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Strength and Conditioning Association. [Accessed March 5, 2007]; Available at: http://www.nsca-cc.org/nsca-cpt/about.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips JM, Drummond MJN. An investigation into the body image perception, body satisfaction and exercise expectations of male fitness leaders: implications for professional practice. Leisure Studies (Lond.) 2001;20:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallis JF, Hovell MF, Hofstetter CR, Faucher P, Spry VM, Barrington E, Hackney M. Lifetime history of relapse from exercise. Addictive Behav. 1990;15:573–579. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner RD, Polly S, Sherman AR. A behavioral approach to individualized exercise programming. In: Krumboltz JD, Thoresen CE, editors. Counseling Methods. New York: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaughn S, Schumm JS, Sinagub J. Focus Group Interviews in Education and Psychology. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]