Abstract

The insects with the longest proboscis in relation to body length are the nectar-feeding Nemestrinidae. These flies represent important pollinators of the South African flora and feature adaptations to particularly long-tubed flowers. The present study examined the morphology of the extremely long and slender mouthparts of Nemestrinidae for the first time. The heavily sclerotized tubular proboscis of flies from the genus Prosoeca is highly variable in length. It measures 20–47 mm in length and may exceed double the body length in some individuals. Proximally, the proboscis consists of the labrum–epipharynx unit, the laciniae, the hypopharynx, and the labium. The distal half is composed of the prementum of the labium, which solely forms the food tube. In adaptation to long-tubed and narrow flowers, the prementum is extremely elongated, bearing the short apical labella that appear only to be able to spread apart slightly during nectar uptake. Moving the proboscis from resting position under the body to a vertical feeding position is accomplished in particular by the movements of the laciniae, which function as a lever arm. Comparisons with the mouthparts of other flower visiting flies provide insights into adaptations to nectar-feeding from long-tubed flowers.

Keywords: co-evolution, Diptera, functional morphology, flower-visiting, pollination

INTRODUCTION

Exceptionally long mouthparts of insects have attracted scientific interest since the time of Darwin. Fascinated over the co-evolutionary ‘arms race’ between an insect pollinator and its host plant, he correctly predicted the existence of an extremely long proboscid sphingid moth as the pollinator of a Madagascan orchid with a 20-cm long nectar spur (Darwin, 1862). Although the longest proboscis is recorded in a neotropical sphingid moth, Diptera from the family Nemestrinidae are the world record holders for the length of proboscides in relation to body length, with some having proboscides that are four-fold longer than their body length (Borrell & Krenn, 2006).

These long-proboscid Diptera are members of an essentially unique pollination system in southern Africa, including several species of Tabanidae and Nemestrinidae, which pollinate flowers within well-defined flower guilds (Goldblatt & Manning, 2000; Johnson, 2010). Linked into a broad network of co-evolution, they have become model organisms for reciprocal adaptation and plant speciation. Investigations during the last 15 years have indicated the role of long-proboscid flies as important pollinators in several floristically rich regions of South Africa, most notably within the winter-rainfall Cape Floristic Kingdom (Goldblatt, Manning & Bernhardt, 1995; Johnson & Steiner, 1997; Goldblatt & Manning, 1999, 2000; Potgieter & Edwards, 2005; Anderson & Johnson, 2008; Pauw, Stofberg & Waterman, 2009). They are considered as keystone species, pollinating more than 170 plant species across various families (including Iridaceae, Geraniaceae, Orchidaceae and Proteaceae). This pollinator–flower system has, extensively, been investigated mainly from a botanical point of view, demonstrating reciprocal adaptations and co-evolutionary relationships between flower depth and proboscis length. Studies indicated that each trait acts as agent and target in directional reciprocal selection, effecting both nectar volume intake and plant fitness (Anderson & Johnson, 2008; Pauw et al., 2009). Furthermore, Anderson & Johnson (2008) suggested that co-evolution might be a major force in shaping morphological traits within a positive feedback system between plant and pollinator.

However, morphological studies on long-proboscid flies are fragmentary, and almost exclusively associated with taxonomic revisions (Barraclough, 2006). In addition, little is known about the physiology (but see Terblanche & Anderson, 2010), biology or life-history requirements of the South African parasitoid Nemestrinidae, such as larval hosts and habitat preferences (Colville, 2006). Such information relating to selective pressures on the fly are essential for fully understanding the possible role that flies play in host plant speciation. Physical and physiological selective constraints on the fly may relate directly to the possible directional dimensions of evolution of floral traits, such as corolla lengths and nectar concentrations.

Flowers visited by long-proboscid flies display similar traits, showing an elongated and narrow, straight or slightly curved floral tube (Goldblatt & Manning, 2000). The composition of flower guilds varies geographically, as does proboscis length and floral tube length between different populations within the same species (e.g. ranges of proboscid lengths from 20–50 mm across different populations of a single nemestrinid species; Anderson & Johnson, 2008, 2009). In an in-depth study, Pauw et al. (2009) highlighted the role of reciprocal selection leading to the eye-catching intraspecific variation of proboscis lengths on certain nemestrinid species. Subsequent to the predictions of the geographical mosaic theory of co-evolution (Thompson, 1994, 2005), the selective pressure of corolla tube length appears to have led to adaptations of proboscis lengths in flies (Anderson & Johnson, 2008; Pauw et al., 2009).

Such co-evolutionary relationships appear to have been long associated with long-proboscid nemestrinid flies. Fossils of Protonemistrus jurassicus (Nemestrinidae) from the Jurassic period found in China show well-developed long proboscides that suggest nectar-feeding from long tubular flowers (Ren, 1998).

However, detailed insights into the co-evolutionary dynamics of elongated plant corolla lengths and fly proboscid lengths are limited as a result of the lack of detailed examinations of long-proboscid mouthpart morphology. A first morphological study indicated a unique structure of the proboscis of Nemestrinidae (Krenn, Plant & Szucsich, 2005); however, detailed examinations of mouthparts and their functional adaptations to their nectar sources are missing so far. The present study aimed to investigate the morphology of the extremely long proboscides of two representatives of the genus Prosoeca, comprising a highly speciose and morphological diverse genus in South Africa (Barraclough, 2006). In addition, comparisons with mouthparts of Bombyliidae and Tabanidae are made aiming to contribute to a better understanding of morphology, function, and evolution of the mouth-parts in these charismatic brachyceran flies.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Specimens

Specimens of Prosoeca ganglbaueri (Lichtwardt, 1910) collected from the summer-rainfall Drakensberg mountains were compared with those of Prosoeca sp. nov. 1 (Diptera: Brachycera, Nemestrinidae) from winter-rainfall Namaqualand, part of the Succulent Karoo global biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al., 2000). Manning & Goldblatt (1996) considered these two species as part of a single pollination guild; however, this is most likely incorrect because the environments associated with the two species are strongly geographically and ecologically disparate.

Captured flies were fixed in a solution of formalin, acetate acid, and alcohol and later stored in 70% alcohol. In addition, several individuals of Prosoeca sp. nov. 1 were captured from two different locations in the surroundings of Nieuwoudtville, Northern Cape Province: Hantam National Botanical Garden (31°24′43″S, 19°09′43″E; N = 30) and Grasberg Road (31°20′54″S, 19°05′30″E; N = 16) in August and September 2010. For all these flies, proboscis lengths were measured with a digital caliper (Helios Digi-Met 1220; 0.01 mm) before being released. Captured individuals were marked with a small dot from an indelible pen on the right forewing to prevent measurements from recaptured individuals.

Serial semithin-sections

Preserved specimens of P. ganglbaueri and Prosoeca sp. nov. 1 were dehydrated and embedded in ERL-4206 epoxy resin and in agar low viscosity resin. Semithin-sections of 1 μm were cut with a Leica EM UC6 microtome using a diamond knife and stained in a mixture of azure II (1%) and methylene blue (1%) in hydrous borax solution (1%) (Pernstich, Krenn & Pass, 2003).

Mouthpart dissections and diagrams

Heads of P. ganglbaueri and Prosoeca sp. nov. 1 were dissected under a stereo microscope to expose the mouthparts. Photos were taken with a digital XLi camera. Using these photos and the semithin sections, line drawings were created with CorelDraw X3.

Scanning electron microscopy

All micrographs were taken with a Philips XL 20 scanning electron microscope using the standard procedures for scanning electron microscopy (Bock, 1987). Proboscides were dehydrated in ethanol and submerged in hexamethyldisilazan. Specimens were mounted on viewing stubs with graphite adhesive tape and sputter-coated with gold.

RESULTS

General features of the Prosoeca proboscis

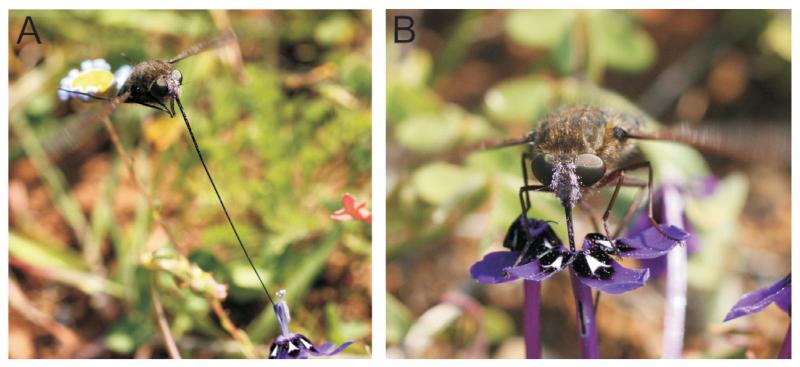

The proboscis of Prosoeca sp. nov. 1 was in the range 28–47 mm (N = 46; mean ± SD length 37.91 ± 4.03 mm), whereas proboscis length in P. ganglbaueri was in the range 20–45 mm (N = 5). In both nemestrinid species, the proboscis was at least twice as long as the body. In the resting position, the proboscis laid ventrally along the mid-line of the body between the fly’s legs and projected beyond the abdomen (Fig. 1A). During feeding from flowers, the proboscis was projected in a slightly forward downward position (Fig. 2). The angle between resting and feeding position reached up to 100°. Apart from proboscis length, the mouthpart morphology of both species shared similar features.

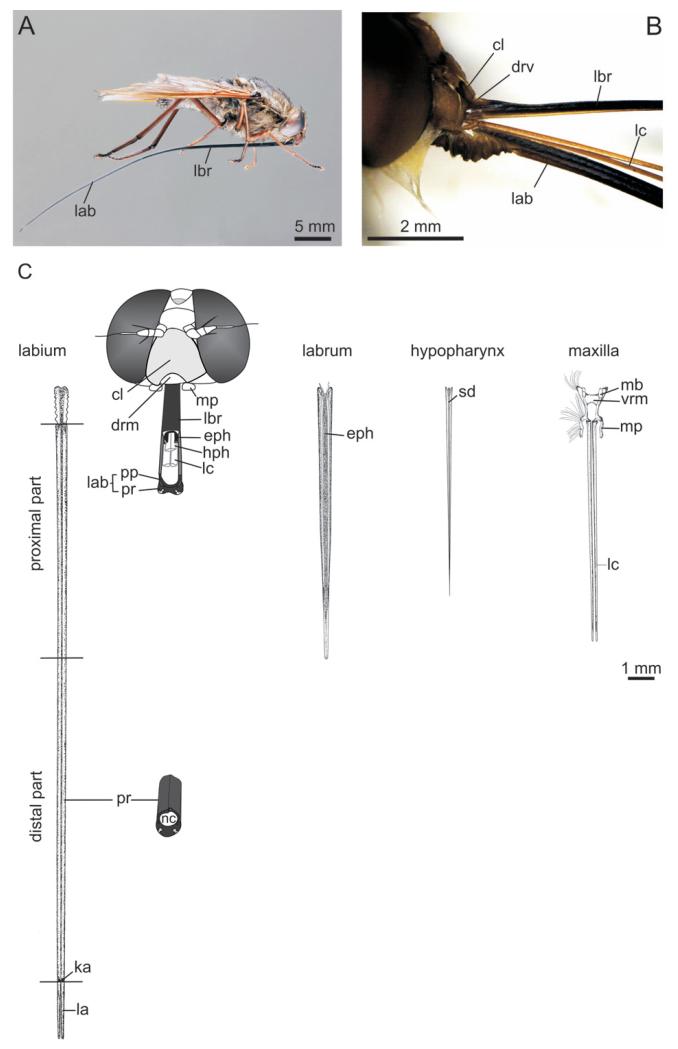

Figure 1. Mouthparts of long-proboscid Prosoeca.

A, Prosoeca sp. nov. 1; in the resting position, the proboscis lies beneath the thorax and abdomen, resting between the coxae. B, membranous labial base, which allows movement of the proboscis. C, head and mouthparts of Prosoeca ganglbaueri; the proximal proboscis is composed of a labrum–epipharynx unit, maxillae, and hypopharynx sheathed in the half pipe of the labium. The distal part is formed by the prementum alone, representing the longest part of the proboscis. On the apical part perch the paired labella. cl, clypeus; drm, dorsal rostral membrane; eph, epipharynx; hph, hypopharynx; ka, kappa; la, labella; lab, labium; lbr, labrum; lc, lacinia; mb, maxillar base; mp, maxillary palpus; nc, nutrition canal; pp, paraphyses; pr, prementum; sd, salivary duct; vrm, ventral rostral membrane.

Figure 2. Prosoeca sp. nov. 1 visiting Lapeirousia oreogena.

A, during foraging, the proboscis is swung forward into a vertical position. B, during feeding, the whole proboscis is inserted into the flower and the labium is stretched forward. The front of the head contacts the anthers, pollinating the flower.

Mouthpart morphology

Overall, the proboscis of Prosoeca species consisted of the labrum–epipharynx unit, maxillae, hypopharynx, and labium (Fig. 1B, C); with mandibles missing. The proboscis was divided into a basal joint region, a proximal region and a distal region, with the latter comprising more than half of the proboscis length. The basal region formed the articulation with the head and allowed flexing of the proboscis backwards from feeding into a resting position (Fig. 1B). The proximal region was composed of the interlocked, half pipe-shaped labrum–epipharynx and labial prementum, both of which formed the food tube containing the slender laciniae and the hypopharynx (Fig. 3A). The distal region of the proboscis consisted of the prementum, which only bears the labella apically (Figs 1C, 3C, 4A).

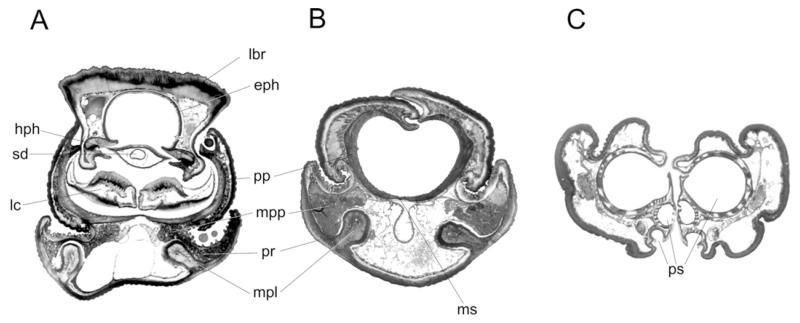

Figure 3. Prosoeca ganglbaueri, proboscis cross sections.

A, proximal part; labium sheath, labrum–epipharynx complex with epipharyngeal food canal, hypopharynx with salivary duct, and laciniae. B, distal part; the labial food canal with lateral prementum walls bend upwards, dorsally interlocking in a tongue and groove. C, labella with paired, nearly closed headers of the pseudotracheae. Ventrally, the labella fold apart to allow nectar uptake. eph, epipharynx; hph, hypopharynx, lc, lacinia; lbr, labrum; mpl, mediolateral prementum ledges; mpp, musculus praemento-paraphysalis; ms, medium stripe pp, paraphyses; pr, prementum; ps, pseudotracheae; sd, salivary duct.

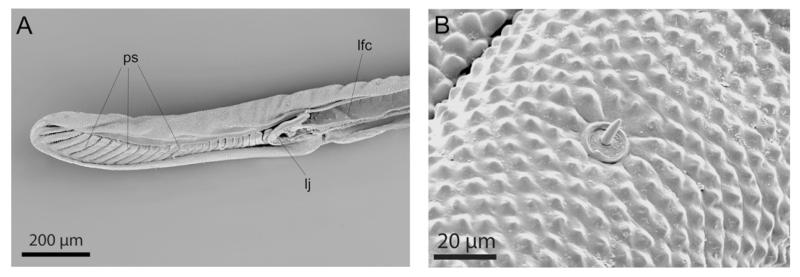

Figure 4. Scanning electron microscope micrographs of the labella of Prosoeca sp. nov. 1.

A, longitudinal section of the labella; pseudotracheae lead into the covered header that is continuous with the labial food canal. B, sensilla basiconica on the labella. Lfc, labial food canal; lj, labella joint; ps, pseudotracheae.

Labium with labella

The lance-shaped prementum of the labium was the longest and most conspicuous part of the proboscis. The labium was divided into: (1) a very short membranous labial base; (2) the proximal part where the food tube was formed in combination with the labrum–epipharynx unit; (3) the distal part where the prementum alone composed the food tube; and (4) the paired and short labella, which formed the tip of the proboscis (Fig. 1C).

The labial base articulated with the head capsule via a rostral membrane on the ventral side and, dorsally, it was connected with the hypopharynx. This articulation and the foldable cuticle of the rostral membrane ensured the movability of the proboscis from the resting to the feeding position (Fig. 1B).

One pair of muscle fibres extended from the posterior head capsule to the prementum base. Originating at the posterior tentorium, the musculus tentoriopreamentalis (mtp) bowed between the maxilla bases to the labium, and attached just after the membranous labial base (Fig. 5).

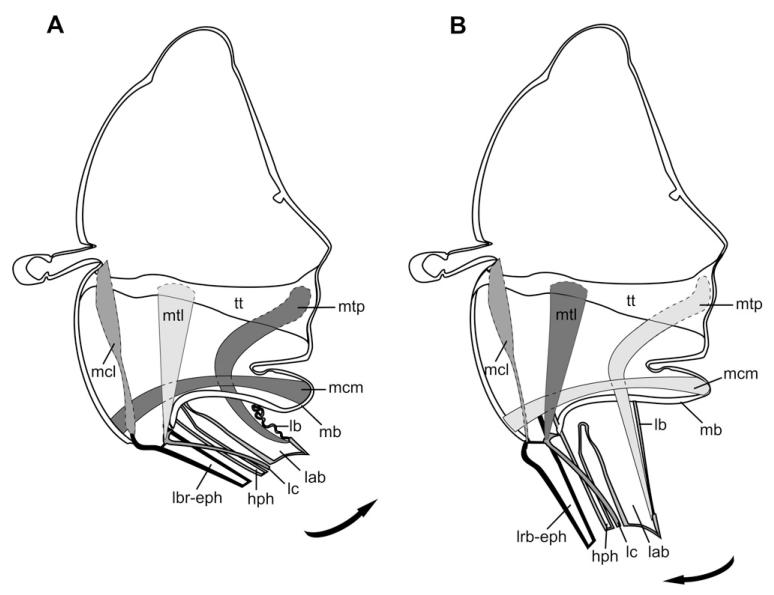

Figure 5. Functional scheme of proboscis movement of Prosoeca ganglbaueri.

Contracting muscles are pictured dark and relaxing muscles light; arrows indicate direction of movement. A, moving into resting position; musculus clypeo-maxillaris (mcm) originates on the lower clypeus and inserts onto the cardo. Mcm constricts the maxillary base, folding the lacinia back. The musculus tentorio-praementalis (mtp) between the tentorium and labium folds the membranous labial base. B, moving into feeding position; originating on the tentorium, musculus tentorio-lacinialis (mtl) inserts near the lacinia base and flaps the lacinia forward. Elevating the laciniae leads to a forward motion of the proboscis. Contraction of musculus clypeo-labralis (mcl) between the clypeus apex and labrum base lifts the labrum forward. hph, hypopharynx; lab, labium; lb, labial base; lc, lacinia; lbr-eph, labrum–epipharynx; mb, maxillary base; tt, tentorium.

In the proximal region, the prementum formed a half pipe that encompassed the labrum–epipharynx unit, the hypopharynx, and the laciniae of the maxillae. The lumen of the prementum contained paired tracheae and a series of bundles of the musculus praemento-paraphysalis. These short muscles originated on the mediolateral ridges of the prementum along the proboscis and extended obliquely to the paraphyses that form the food canal (Fig. 3A, B).

In the distal region, the labial food tube was formed by the longitudinally rolled up prementum (Fig. 3B). The paired paraphyses appeared to strengthen the lateral sides and were separated lengthwise by a weaker sclerotized, median stripe throughout the prementum. Dorsally, a tongue and groove joint of the lateral prementum walls closed the proboscis. Apart from the most basal part, the whole labium was heavily sclerotized and reinforced by mediolateral praemental ledges (Fig. 3A, B).

Distally, the labial food tube led into the paired collecting channels of the labella, which were connected to 25 pseudotracheae on the medial side (Figs 3C, 4A). These canals were the only opening of the otherwise sealed food canal. The labella were laterally separated from the prementum by oblique foldings and articulated with the kappa, a paired sclerit on the most distal part of the prementum (Fig. 1C). Ventrally, the labella were slightly opened, exposing the pseudotracheae to the outside (Fig. 3C). Across the entire surface of the labella and prementum, sensilla basiconica occurred, which were composed of a short socket and a peg-shaped sensory cone (Fig. 4B).

Two small paired muscles originated on the underpart of the proximal prementum and extended, only as elongated tendons, through the distal proboscis. Musculus praemento-labellaris extended to the labella base, whereas musculus praemento-kappalis attached to the kappa (Table 1).

Table 1. Proposed proboscis movement in Nemestrinidae (Prosoeca), Bombyliidae (Bombylius major), and Tabanidae (Tabanus sulicifrons).

| Muscle | Progression | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prosoeca sp. | |||

| 1 | Musculus clypeo-labralis (mcl) | Epistomal sulcus – labral base | Promotor of the labrum |

| 2 | Musculus clypeo-maxillaris (mcm) | Clypeus – cardo | Retractor of the lacinia |

| 3 | Musculus tentorio-lacinialis (mtl) | Central tentorium – lacinial base | Promotor of the lacinia |

| 4 | Musculus tentorio-praementalis (mtp) | Posterior tentorium – praemental base | Retractor of the labium |

| 5 | Musculus preamento-kappalis | Prementum – kappa | Depressor of the labella? |

| 6 | Musculus praemento-labbelaris | Prementum – labellar base | Abductor of the labella? |

| 7 | Musculus praemento-paraphysalis | Lateral prementum – paraphysis | Flexor of the paraphyses? |

| Tabanus sulcifrons (Bonhag, 1951) | |||

| 1 | Musculus clypeo-labralis | Clypeus – labrum | Retractor of the labrum |

| 2 | Musculus geno-maxillaris | Gena – cardo | Promotor of the cardo |

| 3 | Musculus tentorio-stipitalis | Anterior tentorial arm – lacinia | Retractor of the lacinia |

| 3 | Musculus postgeno-stipitalis | Postgena – lacinia | Outer retractor of the lacinia (female only) |

| 4 | Musculus postgeno-labialis | Postgena – labium | Retractor of the labium |

| 5 | Musculus praemento-kappalis | Labial base – kappa | 1. Extensor of the labella |

| 6 | Musculus praemento-epifurcalis | Labial base – epifurca | 2. Extensor of the labella |

| 7 | Musculus praemento-paraphysalis | Lateral prementum – paraphyses | Flexor of the labella |

| Bombylius major (Szucsich & Krenn, 2000) | |||

| 1 | Musculus clypeo-labralis | Clypeus vertex – labral base | Levator of the labrum |

| 2 | Musculus fulcro-stipitalis lateralis | Cibarium bottom – maxillary apodemen | Rotator of the maxillae |

| 2 | Musculus fulcro-stipitalis medialis | Cibarium side – maxillary apodemen | 1. Rotator of the maxillae 2. Depressor of the labium |

| 3 | Musculus tentorio-lacinialis | Posterior tentorium – lacinial base | Retractor of the laciniae |

| 4 | Musculus tergo-labialis | Occiput – prementum | Retractor of the labium |

| 5 | Musculus preamento-kappalis | Lateral prementum – kappa | Extensor of the labella |

| 7 | Musculus preamento-epifurcalis | Median ridge of prementum – epifurca | 1. Adductor of the labella 2. Flexor of the distal labella part |

| 8 | Musculus praemento-paraphysalis | Lateral prementum – paraphysis | Flexor of the labella |

Indications with the same number represent homologous muscles. Functions marked with a question mark remain uncertain. Abbreviations are only given for muscles mentioned in the text.

Handling the proboscis during measurements revealed that the labium can be extended over almost the complete length of the labrum by stretching the membranous basal base. The labrum, on the other hand, could not be moved in the lengthwise direction.

Maxillae

The paired maxillae consisted of fused cardo and stipes in the basal proboscis region. The stipes supported the short, two-segmented maxillary palpus and the elongated, angular lacinia, which extended into the proximal region of the proboscis (Fig. 1B, C). The heavy sclerotized basal parts were connected by the ventral rostral membrane that suspended the maxillae to the head capsule, forming a maxillary trough that also harboured the labial base. The needle-shaped laciniae were noted resting between the paraphyses of the labium (Figs 1C, 3A). Although the maxillary base was rather short but also massive, the laciniae were considerably more weakly sclerotized. Nevertheless, they still represented the longest part of the maxillae; they almost attained one-third of the proboscis length.

Two paired muscles were attached to the maxillae. The musculus tentorio-lacinialis (mtl) originated on the central part of the tentorium and was attached between the lacinia joint and the maxillary base. The massive musculus clypeo-maxillaris (mcm) extended between the clypeus and the cardo alongside the stipes (Fig. 5).

Labrum–epipharynx complex

The strongly sclerotized labrum–epipharynx unit measured more or less one third of the proboscis (P. sp. nov. 1: N = 13; mean ± SD length 14.4 ± 1.33 mm). The epipharyngeal cross-section resembled an omega-shaped half pipe, separated from the labium by a membranous stripe (Fig. 3A). Forming the dorsal cover of the food tube in the proximal region, the labrum articulated with the clypeus via the dorsal rostral membrane (Fig. 1B, C). The epipharynx was connected to the cibarium, forming an epipharyngeal nutrition canal that continued into the head (Fig. 3A). The labrum–epipharynx unit tapered distally, with the tip extending into the distal prementum that formed the food canal of the proboscis.

The musculus clypeo-labralis (mcl) extended from the epistomal sulcus at the top of the clypeus to the labral base (Fig. 5).

Hypopharynx

The lance-shaped, weaker sclerotized hypopharynx was dorsally connected to the bottom of the cibarium. Spindle-shaped in cross section, it was traversed by the salivary duct (Fig. 1C, 3A). Similar to the laciniae, it was slightly shorter than the labrum and lay beneath the labrum–epipharynx unit in the proximal region of the proboscis. It was seen to be engaged into a longitudinal fold of the epipharynx in a key and slot joint (Fig. 3A).

DISCUSSION

Elongated mouthparts of nectar-feeding insects

Within the Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, and Diptera, the longest proboscides have evolved in context with nectar-feeding from long tubular flowers whereby nectar is taken up along a pressure gradient (Krenn et al., 2005). These usually tubular sucking mouth-parts are as long as the head or the body; however, in a few taxa of Lepidoptera and Diptera, proboscides have been recorded exceeding body lengths multiple times (Johnson & Steiner, 1997; Nilsson, 1998; Goldblatt & Manning, 2000; Bauder, Lieskonig & Krenn, 2011). Examinations of the morphology of such extremely long proboscides, in particular considering the adaptations to preferred nectar sources, are restricted to butterflies (Bauder et al., 2011).

The present study of the nemestrinid mouthparts in the genus Prosoeca revealed a unique proboscis structure compared to all other nectar-feeding insects. Similar to other Diptera, the proximal proboscis was composed of two interlocked half-pipe shaped components: the labrum–epipharynx unit and the prementum; also enclosing the maxillary structures and the hypopharynx. The greatly elongated distal part of the proboscis, however, was composed of the prementum alone, which bore the labella apically. Distally, the food canal was formed by a single component, making this proboscid structure unique amongst insects.

Adaptations for nectar uptake through elongated proboscides

In anthophilous Diptera, the mouthparts form tubular sucking organs that take up nectar via the pseudotracheal system of the labella. The nectar is then transported through the food canal into the head where the main sucking pump is situated. Compared to elongated mouthparts in other nectar-feeding Diptera [e.g. Bombylius major (Bombyliidae)], with labella measuring approximately one-third of the proboscis (Szucsich & Krenn, 2000, 2002), the Prosoeca species examined featured rather short labella (Fig. 1C). Although the overall proboscis of the Prosoeca species was much longer than in B. major, the labella only represented a small apical portion of the extremely elongated prementum. A similar trend has been found in butterflies, where the nectar uptake region is shorter in species with exceptionally elongated proboscides (Krenn, Zulka & Gatschnegg, 2001). In butterflies that have an extremely elongated proboscis [e.g. Eurybia lycisca (Riodinidae)], this tip region is particularly short (Bauder et al., 2011).

Flies with short proboscides [e.g. Hemipenthes morio (Bombyliidae)], spread their labella apart for fluid uptake from surfaces through a sponge-like mechanism (Krenn et al., 2005). Additionally, the movement of the labella is also important for pollen-feeding species such as B. major (Szucsich & Krenn, 2002). However, Prosoeca is strictly nectar-feeding, with mouthparts being adapted to suck nectar out of long and narrow floral tubes (Goldblatt & Manning, 2000; Barraclough, 2006). Such flower traits possibly prevent the labella from spreading apart, and nectar intake is therefore most likely performed with closed labella. Overall, labellar musculature appeared to be strongly reduced and its movements are likely to be limited in long-proboscid Prosoeca. This was further supported by the absence of furca and epifurca, comprising paired sclerites that enhance labella movements in Tabanidae (Bonhag, 1951), Syrphidae (Schiemenz, 1957), and Bombyliidae (Szucsich & Krenn, 2000). However, some movement of the labella has been observed in Prosoeca consuming the last remaining droplets of experimentally fed sugar solutions (S. D. Johnson, pers. comm.). Additionally, one of us (J. F. Colville) has observed Prosoeca flies feeding on atypical host plants with broader and shorter corolla tubes during poor-rainfall years when the flowering abundance of traditional host plants is strongly reduced. The limited movement of the labella may allow Prosoeca flies to obtain small amounts of nectar from plant species that produce low quantities of nectar. However, we propose that such limited movability of the labella, together with a modified tip region, represents a suit of particular adaptations of the sucking mouthparts for nectar uptake from narrow, elongated flower tubes. Other characteristic adaptations of long, nectar sucking proboscides in insects are structures that enable fluid intake at the tip of the proboscis. In Prosoeca, primary nectar uptake appears to be facilitated by both capillary and adhesive forces of the pseudotracheal channels.

In many nectar-feeding insects, the modified tip region is equipped with specialized sensilla (Krenn et al., 2005). From their external morphology, the numerous sensilla basiconica on the external side of the labium of Prosoeca can be interpreted as chemo sensilla, which are associated with food localization and flower-probing. Walters, Albert & Zacharuk (1998) described similar sensillae in butterflies as bimodal contact-chemo-mechano sensillae. A great morphological variety of sensilla have evolved in context with nectar-feeding in Lepidoptera (Krenn & Kristensen, 2002; Krenn, 2010). Such a diversity of sensilla is generally not known from dipteran proboscides and, similarly, the sensilla equipment of the labella in Prosoeca was inconspicuous compared to butterflies.

An elongated food tube also requires adequate sealing structures to ensure that the transport of nectar is achieved via a pressure gradient from the tip to the cibarium. In basal Brachycera (e.g. Tabanidae), the epipharyngeal canal is closed by pressing the labrum against the mandibles and the hypopharynx (Bonhag, 1951). In Bombyliidae, the mechanism is reinforced by sclerotized folds pressed on by the laciniae (Szucsich & Krenn, 2000). In Prosoeca, the complex interlocking between the labrum–epipharynx, hypopharynx and the prementum formed a single functional unit, enclosing the sealed food tube. However, in the distal region, the food canal was simply sealed by a dorsal tongue and groove junction of the lateral rolled up prementum walls. This is in strong contrast to other flies and all other flower-visiting insects displaying elongated proboscides (Krenn et al., 2005).

Adaptations for resting and feeding positions of elongated proboscides

Contrasting proboscid resting positions have evolved in different insect taxa with elongated mouthparts (Krenn et al., 2005). Although butterflies and moths coil their proboscis in a spiral under the head, bees disassemble their proboscis to store it under their bodies. Most Cyclorrhapha, as well as short proboscid Bombyliidae, feature a proboscis that is withdrawn into an oral cavity under the head (Graham-Smith, 1930; Krenn et al., 2005). The long-proboscid Bombyliidae (Szucsich & Krenn, 2000, 2002), Tabanidae (Schremmer, 1961), and Apioceridae (Peterson, 1916) posses a proboscis that is stretched forward, both during resting and feeding. By contrast, the proboscis of Nemestrinidae and Acroceridae (Schlinger, 1981) is flexed backwards under the abdomen when at rest. To obtain the feeding position, the proboscis is flapped to an angle of approximately 100° from the resting position. Because studies of proboscis movements in closely-related fly families are missing, we discuss the functional shift of the mouthpart musculature seen in Prosoeca with the plesiomorphic piercing mouthparts of Tabanidae (Bonhag, 1951). The following proposed functional mechanisms for long-proboscid Prosoeca involve the muscles of the labrum, maxillae, and labium that work in conjunction in moving the sclerotized mouthparts (Fig. 5; Table 1).

Contractions of the massive retractor of the lacinia (mcm) probably depress the maxillar base, folding the lacinia backwards. In addition, the position and development of the retractor of the labium (mtp) suggests that it is involved in the folding of the labial base and retraction of the labium under the abdomen (Fig. 5A). In the process of moving the proboscis forward (Fig. 5B), contraction of the promotor of the lacinia (mtl) pulls the stipes up, moving the laciniae forward, which appears to act as a lever for the elongated prementum. In addition, the promotor of the labrum (mcl) may assist in flapping this part forward. Extension of the labium is probably accomplished by the relaxation of its retractor (mtp) (Fig. 5B) and, with the membranous labial base acting as a spring, moving the labium forward along the fixed labrum (Fig. 3A).

Considering the Tabanidae (Bonhag, 1951) in comparison with Nemestrinidae, a galea retractor and an associated protractor were described in Tabanus. However, according to Chaudonneret (1990), the lacinia represents the piercing structure of the maxilla. The labium retractor in Tabanus, in comparison to the musculus tentorio-praementalis (mtp) in Prosoeca, not only originates on the postgena, but is also responsible for moving the prementum into the resting position. The retractor of the labrum described in Tabanus originates on the clypeus and inserts on the basal process of the labrum. Contractions of this muscle pull the basal processes towards the clypeus and thus the distal labrum is pressed against the other mouthparts. Protraction of the lacinia is accomplished by the promotor of the cardo, which is homologous to the retractor of the lacinia (mcm) in Prosoeca (Table 1).

Bombyliidae perform a complex movement procedure that involves folding the rostrum out of the oral cavity and a further rotation movement the extends the proboscis maximally in length (Szucsich & Krenn, 2000, 2002). The labrum and labium are moved into the prognath resting position by the homologous musculus clypeo-labralis and musculus tergo-labialis (Table 1). The movement of the maxilla in Bombyliidae is highly complex and has been described in full detail by Szucsich & Krenn (2000, 2002).

Most nectar-feeding Diptera may have originally evolved from blood-sucking ancestors (Labandeira, 1997). Indeed, Wiegmann et al. (2011) revealed 12 origins of blood-feeding within Diptera, although the origin of blood-sucking in Brachycera remains uncertain. However, many families of long-proboscid flies (e.g. Syrphidae and Bombyliidae) still show well developed, lance-shaped maxillae that originally may have worked as piercing structures (Schremmer, 1961). According to their position within the proboscis, it appears that the elongated laciniae of long-proboscid Prosoeca also underwent a functional change from a piercing to a lifting structure.

Considering the movability of the proboscis, another point has to be considered. Similar to other Nemestrinids, Prosoeca species are likely to be invertebrate parasitoids. They possess a retractile ovipositor with relatively short cerci (Barraclough, 2006), which is used to lay eggs in small holes on dry plant stems (A. Ellis, pers. comm.). How an elongated proboscis might influences egg laying, in terms of its ventral resting position extending across the ovipositor, remains to be studied.

Evolution of mouthpart traits

Various studies have focused on the pollinator-mediated selection on flowers, focusing only on proboscis lengths with a limited consideration of the associated adaptations for attaining extreme mouth-part lengths. (Nilsson et al., 1985; Nilsson, 1988; Johnson & Steiner, 1997; Alexandersson & Johnson, 2002; Whittall & Hodges, 2007; Anderson & Johnson, 2008, 2009; Pauw et al., 2009).

The proboscis of Prosoeca, across several characteristic traits, corresponds to the mouthparts of Tabanidae, which are usually assumed to feature plesiomorphic traits, possibly reflecting the starting point for the evolution of brachyceran mouthparts. In other characters, such as the development of the maxillae, Prosoeca corresponds more to the proboscis of Bombyliidae, which feature modifications more comparable to that of cyclorrhaphan mouthparts. According to Szucsich & Krenn (2000), plesiomorphic traits for Brachycera encompass: (1) a well developed prementum; (2) the laciniae, which still articulates with the maxillary base; (3) paired paraphyses; and (4) the presence of the kappa. The reduced hypoglossa and labellar sclerites, the different labellar muscles, and the proboscis movement can be regarded as an apomorphic condition compared to Tabanidae (Bonhag, 1951), Bombyliidae (Szucsich & Krenn, 2000), and Syrphidae (Schiemenz, 1957). In addition, the extremely elongated prementum, forming the food canal alone, can also be considered as an apomorphic trait of long-proboscid Prosoeca.

The extraordinarily elongated mouthparts appear to have evolved by ‘diffuse co-evolution’ (Janzen, 1980) along with a variety of long-tubed, flower guilds (Anderson & Johnson, 2009; Pauw et al., 2009). The modifications of the proboscis can be regarded as reciprocal adaptations that gave exclusive access to nectar-rewarding long-tubed flowers. The selective pressure of the tubular flowers probably resulted in the evolution of a slender distal proboscis and shaped the proboscis tip morphology in a way that allowed nectar uptake with closed labella through the modified pseudotracheal system. The unique ‘one-piece composition’ of the distal proboscis in Nemestrinidae probably was a prerequisite for the evolution of a particularly slender nectar-extracting organ that is easily adaptable to variable tube lengths of nectar-rewarding flowers in different populations.

The present study has shown that attaining an elongated proboscis requires certain structural adaptations to the mouthparts. Additional studies (e.g. of the suction pumps in the head and the associated costs related to physiological constraints with attaining extreme mouthpart lengths) are required to fully understand the morphological adaptations required for long-tubed flower guild pollination in South Africa.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Core Facility of Cell Imaging and Ultrastructure Research at the University of Vienna for providing the scanning electron microspcopy unit. We also thank Bruce Anderson for collecting flies from the Drakensberg Mountains. Eugene Marinus at the Hantam National Botanical Garden kindly assisted with the collection permits and provided information on locating fly populations. We would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for improving the manuscript, and especially Steve Johnson for proposing an alternative title and additional useful comments. We thank Northern Cape Nature Conservation for collecting and export permits (Permit Numbers 471/2010 and 472/2010). The present study was supported by funds from the Austrian Foundation for Scientific Research FWF (P 222 48-B17).

REFERENCES

- Alexandersson R, Johnson SD. Pollinator-mediated selection on flower-tube length in a hawkmoth-pollinated Gladiolus (Iridaceae) Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 2002;269:631–636. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B, Johnson SD. The geographical mosaic of coevolution in a plant–pollinator mutualism. Evolution. 2008;62:220–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B, Johnson SD. Geographical covariation and local convergence of flower depth in a guild of flypollinated plants. New Phytologist. 2009;182:533–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough DA. An overview of the South African tangle-veined flies (Diptera: Nemestrinidae), with an annotated key to the genera and a checklist of species. Zootaxa. 2006;1277:39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bauder JAS, Lieskonig NR, Krenn HW. The extremely long-tongued Neotropical butterfly Eurybia lycisca (Riodinidae): proboscis morphology and flower handling. Arthropod Structure & Development. 2011;40:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock C. A quick and simple method for preparing soft insect tissues for scanning electron microscopy using Carnoy and hexamethyldisilazane. Beiträge zur elektronenmikroskopischen Direktabbildung von Oberflächen. 1987;20:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bonhag PF. The skeleto-muscular mechanism of the head and abdomen of the adult horsefly (Diptera: Tabanidae) Transactions of the American Entomological Society (1890) 1951;77:131–202. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell BJ, Krenn HW. Nectar feeding in long-proboscid insects. 2006. pp. 185–211.

- Chaudonneret J. Les pièces buccales des insectes. Thème et Variationes. Imprimerie Berthier & Cie; Dijon: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Colville JF. A profile of the insects of the Kamiesberg Uplands, Namaqualand, South Africa. CEPF Report; Cape Town: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin CR. On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilized by insects. John Murray; London: 1862. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt P, Manning JC. The long-proboscid fly pollination system in Gladiolus (Iridaceae) Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1999;86:758–774. [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt P, Manning JC. The long proboscid flypollination system in southern Africa. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 2000;87:146–170. [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt P, Manning JC, Bernhardt P. Pollination biology of Lapeirousia subgenus Lapeirousia (Iridaceae) in southern Africa; floral divergence and adaptation for long-tongued fly-pollination. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1995;82:517–534. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Smith GS. Further observations on the anatomy and function of the proboscis of the blow-fly, calliphora erythrocephala L. Parasitology. 1930;22:47–115. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen DH. When is it coevolution. Evolution. 1980;34:611–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SD. The pollination niche and its role in the diversification and maintenance of the southern African flora. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Series B, Biological Sciences. 2010;365:499–516. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SD, Steiner KE. Long-tongued fly pollination and evolution of floral spur length in the Disa draconis complex (Orchidaceae) Evolution. 1997;51:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb02387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenn HW. Feeding mechanisms of adult lepidoptera: structure, function, and evolution of the mouthparts. Annual Review of Entomology. 2010;55:307–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenn HW, Kristensen NP. Evolution of proboscis musculature in Lepidoptera. European Journal of Entomology. 2002;101:565–575. [Google Scholar]

- Krenn HW, Plant JD, Szucsich NU. Mouthparts of flower-visiting insects. Arthropod Structure & Development. 2005;34:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Krenn HW, Zulka KP, Gatschnegg T. Proboscis morphology and food preferences in nymphalid butterflies (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Journal of Zoology. 2001;254:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira CC. Insect mouthparts: ascertaining the paleobiology of insect feeding strategies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1997;28:153–193. [Google Scholar]

- Manning JC, Goldblatt P. The Prosoeca peringueyi (Diptera: Nemestrinidae) pollination guild in southern Africa: long-tongued flies and their tubular flowers. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1996;83:67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 2000;403:853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson AL. The evolution of flowers with deep corolla tubes. Nature. 1988;334:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson AL. Deep flowers for long tongues. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1998;13:259–260. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson LA, Jonsson L, Rason L, Randrianjohany E. Monophily and pollination mechanisms in Angraecum arachnites Schltr. (Orchidaceae) in a guild of long-tongued hawk-moths (Sphingidae) in Madagascar. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1985;26:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pauw A, Stofberg J, Waterman RJ. Flies and flowers in Darwin’s race. Evolution. 2009;63:268–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernstich A, Krenn HW, Pass G. Preparation of serial sections of arthropods using 2,2-dimethoxypropane dehydration and epoxy resin embedding under vacuum. Biotechnic & Histochemistry. 2003;78:1–5. doi: 10.1080/10520290312120002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A. The head-capsule and mouth-parts of Diptera. Illinois Biological Monographs. 1916;3:1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Potgieter CJ, Edwards TJ. The Stenobasipteron wiedmanni (Diptera, Nemestrinidae) pollination guild in Eastern Southern Africa. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 2005;92:254–267. [Google Scholar]

- Ren D. Flower-associated brachycera flies as fossil evidence for jurassic angiosperm origins. Science. 1998;280:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiemenz H. Vergleichende funktionell-anatomische Untersuchungen der Kopfmuskulatur von Theobaldia und Eristalis (Dipt. Culicid. und Syrphid.) Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift. 1957;4:268–331. [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger EI. Acroceridae. In: McAlpine JFEA, editor. Manuel of nearctic diptera 1. Research branch agriculture monograph. Canada Communication Group Pub; Ottawa: 1981. pp. 575–584. [Google Scholar]

- Schremmer F. Morphologische Anpassungen von Tieren – insbesondere Insekten – an die Gewinnung von Blumennahrung. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Zoologischen Gesellschaft. 1961;25:375–401. [Google Scholar]

- Szucsich NU, Krenn HW. Morphology and function of the proboscis in Bombyliidae (Diptera, Brachycera) and implications for proboscis evolution in Brachycera. Zoomorphology. 2000;120:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Szucsich NU, Krenn HW. Flies and concealed nectar sources: morphological innovations in the proboscis of Bombyliidae (Diptera) Acta Zoologica. 2002;83:183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Terblanche J, Anderson B. Variation of foraging rate and wing loading, but not resting metabolic rate scaling, of insect pollinators. Die Naturwissenschaften. 2010;97:775–780. doi: 10.1007/s00114-010-0693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JN. The coevolutionary process. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JN. The geographic mosaic of coevolution. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Walters BD, Albert PJ, Zacharuk RY. Morphology and ultrastructure of sensilla on the proboscis of the adult spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem.) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Canadian Journal of Zoology. 1998;76:466–479. [Google Scholar]

- Whittall JB, Hodges SA. Pollinator shifts drive increasingly long nectar spurs in columbine flowers. Nature. 2007;447:706–709. doi: 10.1038/nature05857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegmann BM, Trautwein MD, Winkler IS, Barr NB, Kim J-W, Lambkin C, Bertone MA, Cassel BK, Bayless KM, Heimberg AM, Wheeler BM, Peterson KJ, Pape T, Sinclair BJ, Skevington JH, Blagoderov V, Caravas J, Kutty SN, Schmidt-Ott U, Kampmeier GE, Thompson FC, Grimaldi DA, Beckenbach AT, Courtney GW, Friedrich M, Meier R, Yeates DK. Episodic radiations in the fly tree of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:5690–5695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012675108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]