Abstract

Amyloid-beta (Aβ)-induced neurotoxicity is a major contributor to the pathologies associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD). The formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), an early response induced by the peptide and oligomeric derivatives of Aβ, plays a significant role in effecting cellular pathogenesis. Here we employ particularly toxic forms of Aβ with cultured primary cortical/hippocampal neurons to elicit ROS and drive cellular dysfunction. To prevent and even reverse such effects, we utilized a cell-penetrating, peroxisome-targeted, protein biologic – called CAT-SKL. We show the recombinant enzyme enters neurons, reverses Aβ-induced oxidative stress, and increases cell viability. Dramatic restorative effects on damaged neuronal processes were also observed. In addition, we used DNA microarrays to determine Aβ's effects on gene expression in neurons, as well as the ability of CAT-SKL to modify such Aβ-induced expression profiles. Our results suggest that CAT-SKL, a targeted antioxidant, may represent a new therapeutic approach for treatment of disorders, like Alzheimer's disease, that are driven through oxidative stress. Preclinical testing is ongoing.

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder caused by multiple conspiring pathologies including misprocessing of the amyloid precursor protein (to Aβ peptide and related higher order structures); tau phosphorylation, relocalization, and deposition; activity of presenilins and the effects of specific ε4 alleles of apolipoprotein E; α synuclein/Lewey body accumulation; and is potentiated by the effects of aging1,2,3. Thus, a barrage of anti-proteostatic effects are brought to bear on neurons, with devastating consequences.

In this report, we concentrate on the neurocompromising effects of Aβ peptides, molecules thought to trigger a cascade of early neuropathogenic activities. In particular, we focus on soluble forms of the toxic Aβ-peptide, called amyloid β-derived diffusible ligands - or ADDLs4. These Aβ-derivatives are thought to interact with specific cell surface receptors to trigger ROS formation and associated downstream cytotoxic effects4. Indeed, ADDLs may initiate a self-perpetuating spiral of toxic Aβ-formation/deposition, and cell pathology5.

To confer neuroprotection in our culture model, we targeted the response arm of Aβ-toxicity; specifically the formation of ROS. This was accomplished in a manner distinct from previously employed (and failed6,7,8,9) approaches of flooding cells with non-targeted antioxidants. It is becoming well understood that cells employ ROS as effectors of signaling, communication and metabolic regulatory networks, and that these molecules cannot be indiscriminately quenched10,11. Our approach is to target a powerful antioxidant, in this case catalase12,13, to the peroxisome where an accumulating literature suggests the enzyme maintains and/or reestablishes oxidative balance without side-effects. To accomplish this, we employed CAT-SKL, a genetically engineered recombinant derivative of catalase containing a cell penetrating peptide at its amino terminus and an altered, more efficient peroxisomal targeting signal at its carboxy terminus. The results with CAT-SKL have been dramatic in a number of cellular and preclinical settings14,15,16,17,18. Here the targeted catalase molecule was able to protect rat primary cortical/hippocampal cultures from ADDL-induced cytotoxicity as manifest by effects on ROS production, gene expression, neurite formation, and overall cell viability.

Results

ADDL characterization and toxicity

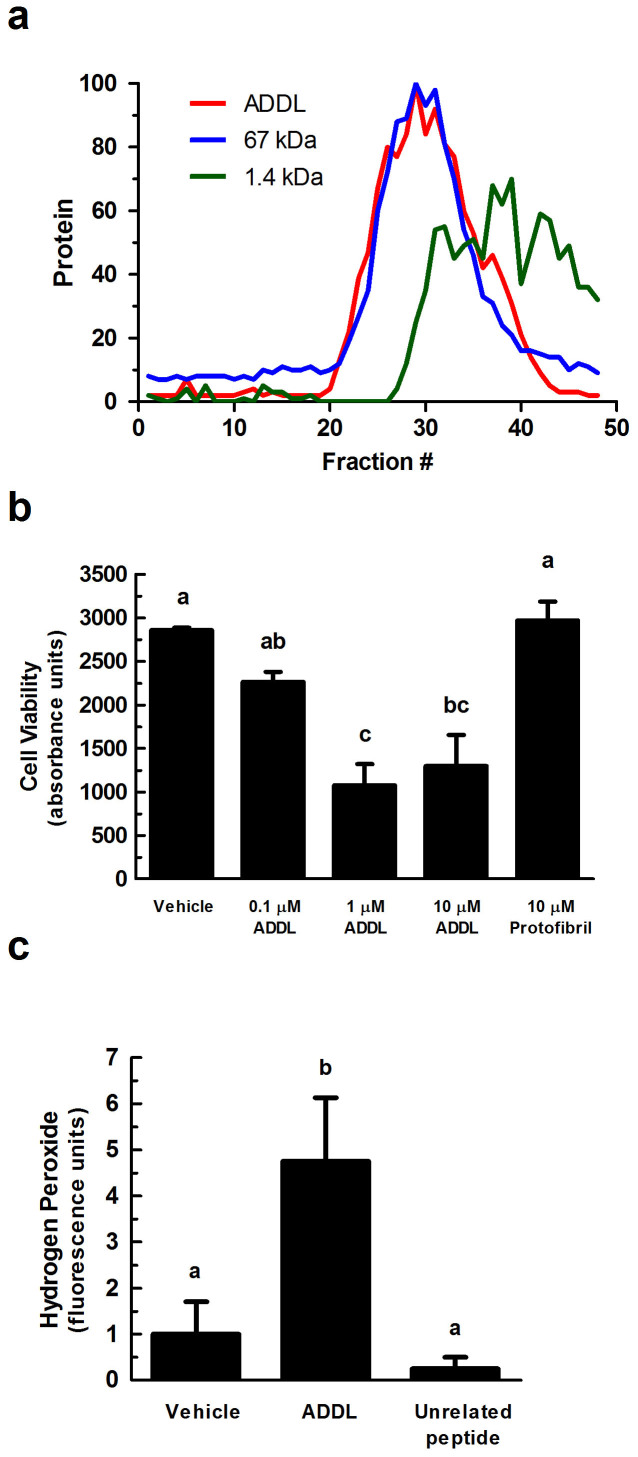

Freshly prepared ADDLs were characterized to document the nature of the oligomeric species created. The Aβ peptide used to generate ADDLs is 42 amino acids (~4.5 kDa). A gel filtration column was prepared with G-50 Sephadex beads, a sizing column that excludes proteins greater than 30 kDa. Sample fractions of ADDLs were collected and compared to the behavior of 67 kDa and 1.4 kDa control polypeptides. The prepared ADDLs were confirmed to be mainly larger oligomeric species, displaying an excluded migration pattern similar to the 67 kDa protein (Fig. 1a). Therefore, in our hands, ADDLs contain largely oligomeric assemblies of Aβ – consistent with the results reported by others4,19,20,21. Soluble forms of Aβ accumulate in the human brain and are thought to cause the functional deficits that precede neuronal death. Indeed, these ADDLs are considered to be a major driver of the early stages and progression of AD. To determine if freshly prepared ADDLs were toxic to primary neuronal cultures, several concentrations of the oligomeric peptide were added to cells. The cells employed were embryonic day 18 Sprague Dawley rat cortical/hippocampal neurons. Cells were harvested from fresh brain tissue, plated, and differentiated as described in the methods. After 7 days of differentiation, the neurons displayed axons and dendrites, and are known to form synapses and conduct action potentials22,23. Our neuronal cultures stained positive for the dendritic marker, MAP-2, (see Fig. 4 below) and the axonal marker, neurofilament-68 (data not shown).

Figure 1. ADDL-induced toxicity in primary cortical/hippocampal neurons.

(a) ADDLs were subjected to gel filtration (using Sephadex G-50 beads) to characterize their sizing behavior. Any molecule greater than 30 kDa is excluded from the column (~fraction 20). Red line = ADDLs, blue line = 67 kDa protein, and green line = 1.4 kDa peptide. Y-axis is normalized protein intensity as quantified by Image J software. (b) Primary rat cortical/hippocampal cultures were treated with ADDLs (0.1, 1, and 10 μM), as indicated, for 24 hours. Cell viability was determined using the water soluble tetrazolium cell proliferation assay (WST-1). Bars represent mean ± SEM for triplicate samples. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test (p > 0.05). (c) Hydrogen peroxide production was measured using the Amplex® Red reagent (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine). ADDLs (1 μM for 24 hours) induced hydrogen peroxide production in primary rat cortical/hippocampal neurons. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When ANOVA indicated significant treatment effects, means were separated using Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test. Bars represent mean ± SEM for quadruplicate samples. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05). Similar results were seen in three additional experiments.

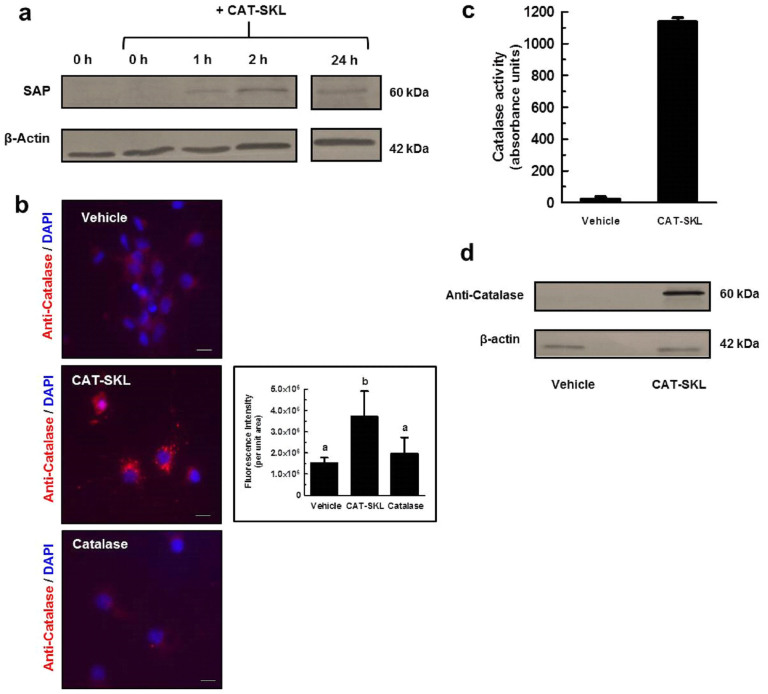

Figure 2. CAT-SKL transduction of primary cortical/hippocampal neurons.

(a) Primary rat cortical/hippocampal neurons were treated with 100 nM biotinylated CAT-SKL for 0, 1, 2, and 24 hours, washed, and harvested in sample buffer. Transduction was demonstrated by probing cell extracts with streptavidin alkaline phosphatase (SAP). β-actin was used as a loading control. Results shown are from same probed blot. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure 2a. (b) Cells were treated with vehicle, 1 μM CAT-SKL, or 1 μM catalase for 24 hours. Cells were then washed, fixed, and immunostained for catalase (red fluorescence) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue fluorescence). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. When ANOVA indicated significant treatment effects, means were separated using Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test. Bars represent mean ± SEM for replicate samples (n = 8). Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05). Scale bar = 20 μm. Catalase enzymatic activity (c) and immunoreactivity (d) was measured after 24 hour treatment with 1 μM CAT-SKL or without (indicated as vehicle). Cells were washed, harvested in PBS, and equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE. Antibodies utilized include anti-catalase and anti-β-actin (n = 3). Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure 2b.

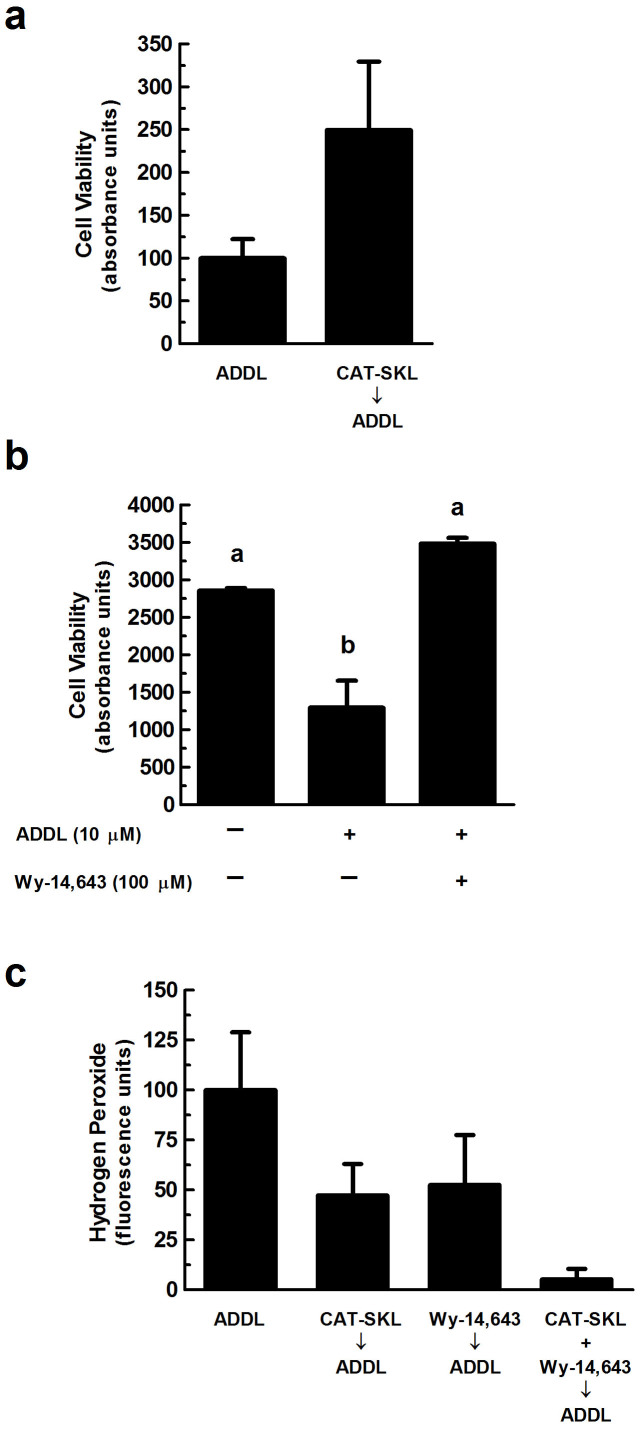

Figure 3. Neuroprotective effects of CAT-SKL against ADDL-induced neurotoxicity.

(a) Primary rat cortical/hippocampal neurons were pretreated with CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours and subsequently challenged with ADDLs (1 μM) for 24 hours. (b) Cells were pretreated with the peroxisomal proliferator Wy-14,643 (100 μM) for 48 hours and then challenged with ADDLs (10 μM) for an additional 24 hours. Cell viability was determined using the water soluble tetrazolium cell proliferation assay (WST-1). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. When ANOVA indicated significant treatment effects, means were separated using Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test. Bars represent mean ± SEM for triplicate samples. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05). (c) Neurons were pretreated with CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours and/or Wy-14,643 (100 μM) for 48 hours. Amount of hydrogen peroxide produced in cells was determined by the Amplex® Red reagent (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxy-phenoxazine) (n = 4). Similar results were seen in three additional experiments.

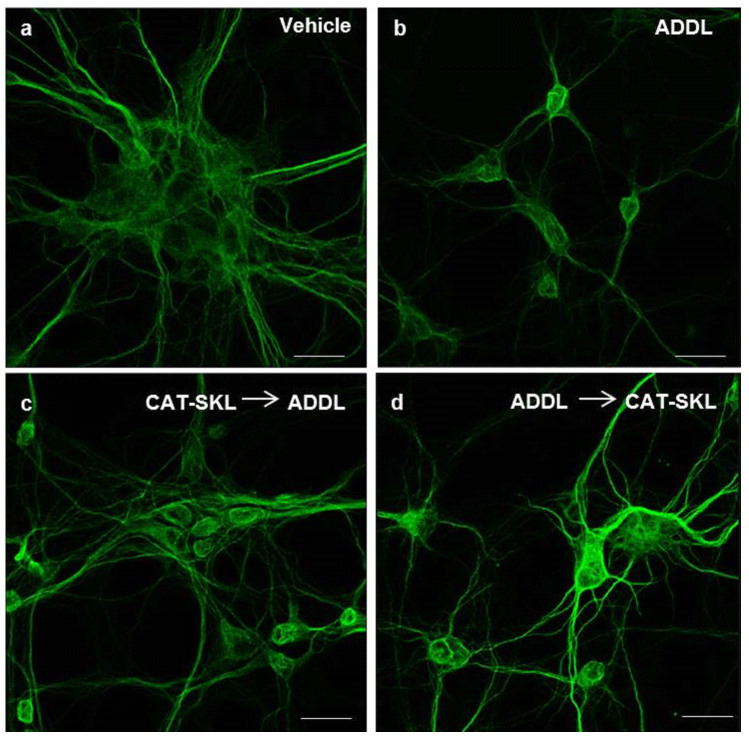

Figure 4. Effects of CAT-SKL on ADDL-induced neurite degeneration in primary rat cortical/hippocampal neurons.

Primary rat cortical/hippocampal neurons were treated as follows: (a) Vehicle control for 24 hours. (b) ADDLs (1 μM) for 24 hours. (c) CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours, followed by ADDLs (1 μM) for 24 hours. (d) ADDLs (1 μM) for 24 hours, followed by CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours. Neurons were immunostained with anti-MAP-2 antibodies (a dendritic marker), and visualized with AlexaFluor 488-goat anti-mouse antibodies (green fluorescence). Scale bar = 20 μm.

Cellular mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity was measured by absorbance spectroscopy to determine cellular viability after treatment with ADDLs at 0.1, 1, and 10 μM for 24 hours (Fig. 1b). Compared to untreated neurons, 1 and 10 μM ADDLs significantly reduced metabolic activity as indicated by the decrease in formazan dye formed (p < 0.05), thus confirming toxicity of the ADDL preparations to neurons as previously reported4. Metastable intermediates of insoluble Aβ fibrils, called protofibrils were also prepared for this study but showed no toxicity compared to a vehicle control (Fig. 1b); further strengthening the notion that soluble oligomers of Aβ are the more harmful state of the peptide.

As introduced above, Aβ induces ROS production in cells of the brain. Here, we specifically measured hydrogen peroxide in primary neuronal cultures and found that addition of 1 μM ADDLs for 24 hours significantly increased levels of ROS (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1c). An unrelated peptide had no such effects (Fig. 1c).

CAT-SKL transducibility

We utilized CAT-SKL, which has been shown to robustly metabolize hydrogen peroxide within the peroxisome and other cellular compartments, and restore oxidative equilibrium within cells14,15,16,17,24, to determine the role of hydrogen peroxide and related ROS in ADDL-induced neurotoxicity. Transduction of the targeted antioxidant has been documented in a number of cell types, with entry confirmed within 1 hour of addition14. To demonstrate transduction of CAT-SKL in neurons, we tracked cell entry of a biotinylated form of the recombinant enzyme (Fig. 2a). Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed catalase staining was significantly increased in CAT-SKL treated neurons compared to vehicle or a non-transducible form of the recombinant enzyme (Fig. 2b). Similar transduction results were obtained in live cells with a CAT-SKL molecule covalently conjugated to red fluorescent spheres (Supplementary Fig. S1a), ruling out potential artefactual fixation anomalies. Importantly, CAT-SKL - FluoSpheres® was enzymatically active – confirming no loss of quaternary structure for the obligate tetramer (Supplementary Fig. S1b). As expected, catalase activity and immunoreactivity were increased in CAT-SKL-treated neuronal cultures after a 24 hour incubation (Fig. 2c,d).

Neuroprotective effects of CAT-SKL

We next examined the protective effects of CAT-SKL against ADDL-induced neuronal toxicity. To accomplish this, cellular mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity was measured by absorbance spectroscopy to determine cell viability in neurons pretreated with 1 μM CAT-SKL and subsequently challenged with 1 μM ADDLs. Pretreatment with CAT-SKL exhibited a protective effect against ADDLs as evidenced by an increase in cell viability (Fig. 3a). Likewise the peroxisomal proliferator Wy-14,643, which previously has been shown to increase endogenous catalase levels25,26, also is protective when added prior to ADDL challenge (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, pretreatment with 1 μM CAT-SKL and/or 100 μM Wy-14,643 also reduced ADDL-induced hydrogen peroxide levels (Fig. 3c).

Fluorescence microscopy was employed to extend our quantitative biochemical results. Here, primary neuronal cultures were stained for microtubule associated protein-2 (MAP-2), a dendritic marker. Compared to a vehicle control (Fig. 4a), 1 μM ADDLs triggered a retraction in dendritic arborization (branching of dendrites), which resulted in decreased cell body clustering (Fig. 4b). Importantly, CAT-SKL added before or after ADDL treatment protected against these effects (Fig. 4c,d). Similar effects on dendrites were observed with the peroxisome proliferator Wy-14,643 (data not shown).

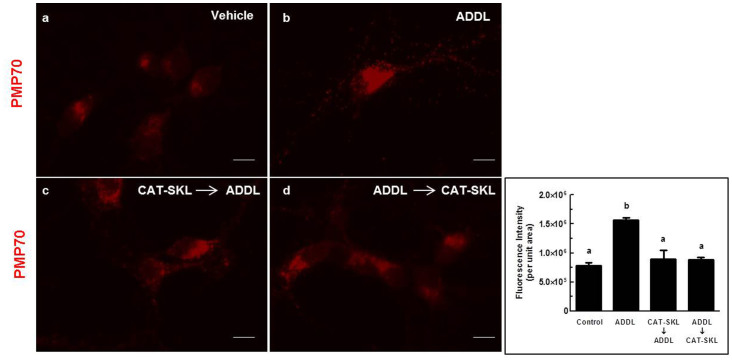

Primary neuronal cultures were also stained for PMP70, a peroxisomal membrane protein. Since CAT-SKL resides in the peroxisome and alters its oxidative environment, we hypothesized that there would be an effect on peroxisome number or morphology between treatments. We have previously reported peroxisomal proliferation in aged, diseased, or xenobiotic-treated cells27,28,29,30. The molecular basis for this induction is unclear; we have speculated that it happens to compensate for compromised peroxisome functioning or to assist mitochondria in metabolizing pathological levels of ROS18. Alternatively, rates of pexophagy may be compromised31. Here, in neurons, we find that ADDLs also triggered significant increases in peroxisomal numbers, evident both within cell processes and cell bodies (Fig. 5a,b) (p < 0.05). Importantly, pre-and post-treatments with CAT-SKL significantly reversed these changes, resulting in peroxisomal staining more akin to that seen in untreated cells (Fig. 5c,d) (p < 0.05).

Figure 5. CAT-SKL thwarts ADDL-induced proliferation of peroxisomes.

Primary rat cortical/hippocampal neurons were treated as follows: (a) Vehicle control for 24 hours. (b) ADDLs (1 μM) for 24 hours. (c) CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours followed by ADDLs (1 μM) for 24 hours. (d) ADDLs (1 μM) for 24 hours followed by CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours. Neurons were immunostained with anti-PMP70 (70 kDa peroxisomal membrane protein) antibodies followed by AlexaFluor 546 goat anti-rabbit antibodies (red fluorescence). Quantification (inset) was accomplished using Image J shareware. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. When ANOVA indicated significant treatment effects, means were separated using Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test. Bars represent mean ± SEM for replicate samples (n = 5). Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05). Scale bar = 20 μm.

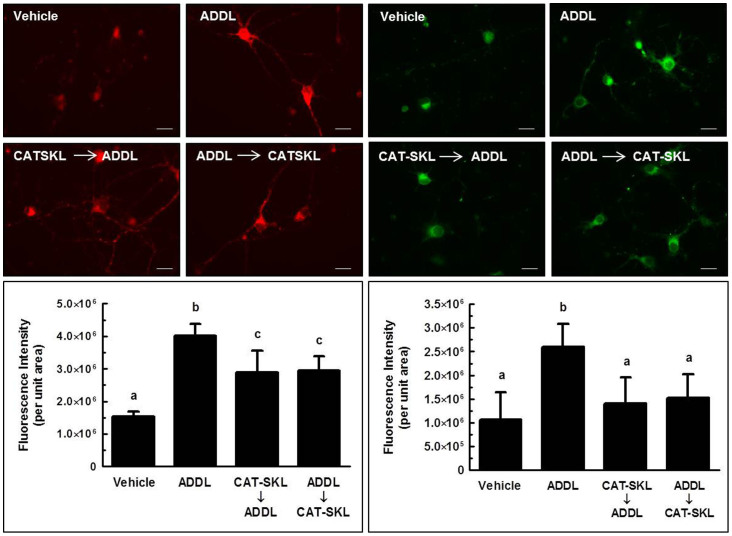

CAT-SKL and ADDL-induced mitochondrial impairment

Mitochondria and peroxisomes may share a redox-based dynamic relationship whereby changes in oxidant handling or overall function of one organelle, impacts the structural and functional integrity of the other24,28,29,32,33. For example, if the ability of peroxisomes to metabolize hydrogen peroxide is abrogated, mitochondria depolarize and begin producing ROS themselves24,28,29,32. In contrast, if peroxisomal antioxidant capacity is enhanced, mitochondria repolarize and reduce oxidant production24.

In our culture studies, ADDLs cause neuronal mitochondria ROS production and depolarization (Fig. 6). The former is seen as an increase in red fluorescence emitted by a mitochondrial ROS-sensitive dye; the latter by an increase in the monomeric (green fluorescence) form of the JC-1 dye. Importantly, CAT-SKL significantly reversed these effects if supplied after ADDL treatment; or prevented them if provided prophylactically (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. CAT-SKL's effects on mitochondria in ADDL-treated neurons.

Left panel: Mitochondrial ROS was determined using the MitoTracker® Red CM-H2XRos selective probe (red fluorescence). Right panel: Mitochondrial depolarization was visualized using the JC-1 mitochondrial potential sensor (green fluorescence). Quantification (insets) was accomplished using Image J shareware. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. When ANOVA indicated significant treatment effects, means were separated using Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test. For left and right inset graphs, bars represent mean ± SEM for replicate samples (n = 6 and n = 8, respectively). Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05). Scale bar = 20 μm.

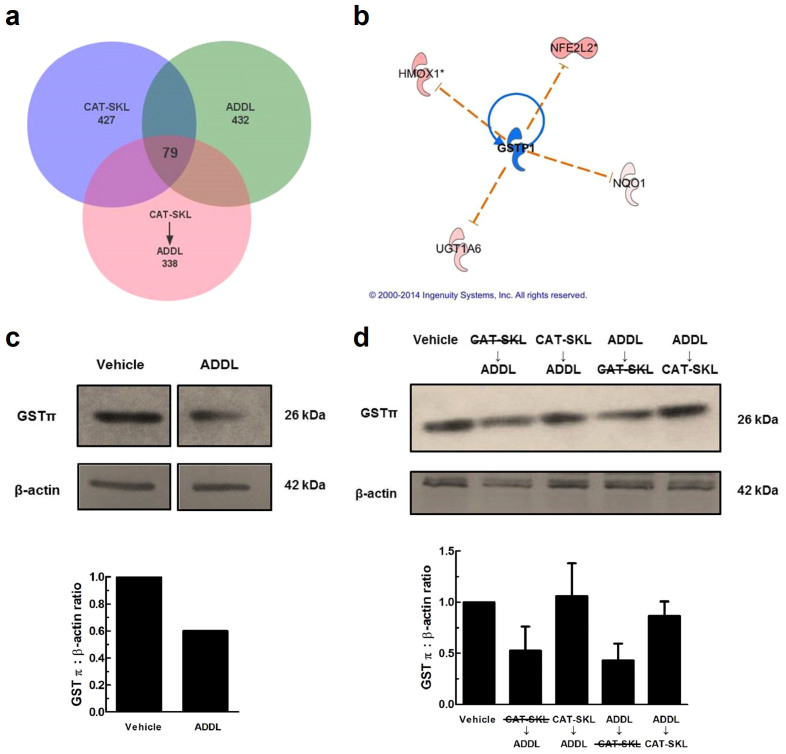

ADDLs, CAT-SKL, and glutathione S-transferase

DNA microarray experiments were performed to determine the gene expression profiles of cells treated with ADDLs, CAT-SKL or CAT-SKL → ADDLs, as compared to untreated (control) cells. Importantly, 79 genes showing significant expression level changes were in common between treatments (see Venn diagram – Fig. 7a). Mining of functional association pathways with Ingenuity Systems' Pathway Analysis software highlighted glutathione S-transferase (GST), a critical cellular detoxifying enzyme, among genes specifically altered by the treatments. Furthermore, upstream regulatory analysis predicted that the specific isoform, GSTπ, was inactivated by ADDLs (Fig. 7b). This analysis, which was implemented using Ingenuity Systems software, can predict transcription factors involved in the gene expression changes observed in the data sets, and whether or not they are activated or inhibited. GST was investigated further because of the dramatically reduced levels in post-mortem brains of AD patients34.

Figure 7. CAT-SKL protects neurons from GSTπ depletion in ADDL treated neurons.

(a) Venn diagram illustrating 79 overlapping genes between treatments. A total of 432 genes were altered in ADDLs, 427 in CAT-SKL, and 338 in CAT-SKL followed by ADDL treatments. Complete lists of genes are available in supplementary Table 1. (b) Upstream regulator analysis was used to identify potential molecules upstream responsible for the observed gene expression changes in the dataset. Blue indicates upstream regulator GSTπ is predicted to be inactivated. Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NFE2L2) is a transcription factor involved in increasing the expression of various antioxidant enzymes including: heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1), UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A6), and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1), among others. (c) Vehicle and ADDL (1 μM) treated neurons for 24 hours. Bands are taken from same western blot. Quantification of western blots normalized to β-actin. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure 2c. (d) Lane assignments left to right: Vehicle control: cells pretreated with enzymatically inactive CAT-SKL (1 μM) - indicated with line through for 24 hours, followed by ADDL (1 μM) for 24 hours; cells pretreated with CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours, followed by ADDL (1 μM) for 24 hours; cells treated with ADDL (1 μM) for 24 hours, followed by enzymatically inactive CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours; cells treated with ADDL (1 μM) for 24 hours, followed by CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours. Quantification of western blots normalized to β-actin (n = 3). Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure 2d.

Western blotting of ADDL-treated neurons revealed GSTπ levels to be reduced (Fig. 7c). However, the effects of ADDL treatment on GSTπ were reversed when CAT-SKL was present, either before or after ADDL treatment (Fig. 7d). A heat inactivated form of CAT-SKL had no such effects on restoring GSTπ levels (Fig. 7d).

Discussion

The importance of soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ as a major driving force in the initial stages of AD has been receiving ever wider acceptance2,4,19,20,21. Here, we confirm the toxicity of ADDLs in rat primary neuronal cultures. In addition, we show these effects are prevented or reversed by the peroxisomally targeted antioxidant enzyme, CAT-SKL. How catalase supplementation of peroxisomes exerts such dramatic protective effects on neurons is not completely clear. Indeed, there is only limited understanding of peroxisome involvement in AD, despite the clear importance of the organelle in overall cell physiology. What is known is that peroxisome activity is upregulated in early states of the disease, an apparent initial response to Aβ's effects35,36. At later stages of the disease, changes in peroxisome number, activity, and oxidative balance are observed25,26. Plasmalogens, critical ether-linked phospholipids synthesized initially in peroxisomes, are present at diminished levels in the AD brain. Accompanying this lipid perturbation are elevated levels of very long chain fatty acids, potentially toxic molecules normally metabolized in the organelle. Finally, in the AD brain peroxisome density increases in neuronal cell bodies37.

Despite the uncertainty regarding peroxisomes and their role in neuronal health and Aβ-induced cytotoxicity, the results presented in this work suggest that an oxidatively-balanced peroxisome is a desirable goal. Neuronal cells with peroxisomes made resistant to enhanced oxidative stress by addition of catalase, are robustly protected against the toxic effects of Aβ. ROS are present at reduced levels, the exquisitely complex neuronal architecture is maintained or regenerated, and viability is enhanced.

Effects of CAT-SKL are not restricted to peroxisomes. The targeted antioxidant once again reverses mitochondrial dysfunction, at least at the level of oxidant production and organelle polarity (Fig. 6). Changes in mitochondrial form and function are known to accompany AD pathogenesis38,39,40. The nature of the redox-based interplay between peroxisomes and mitochondria is a fascinating topic for future investigation, both within and without the context of AD.

An important validation of the culture system employed in these studies was the demonstration, by DNA microarray analysis, that expression of the detoxifying enzyme GSTπ was compromised by ADDLs (and reversed by CAT-SKL). GSTπ is a critically important cellular enzyme and there is no clear understanding of why the enzyme is present in greatly diminished concentrations in the AD brain. It is not known to what extent decreased transcription and translation contributes – versus a destabilization or degradation of the fully synthesized molecule. In our culture model, whatever mechanism is responsible for reduced levels of the enzyme, they are sensitive to CAT-SKL's redox-balance-creating effects. The fact that GST is inactivated by the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal, supports the damage by oxidation theory34.

Targeted antioxidant prophylaxis is a relatively new concept, and is gaining momentum in this time of considerable question about the safety and efficacy of more traditional antioxidants6,7,8,9,41. Is it the non-selective quenching of oxidants that is detrimental? Or perhaps the high concentrations required of molecules needed in stoichiometric amounts. Regardless, our work suggests CAT-SKL possess powerful neuroprotective effects against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity; preclinical testing is the next step and has commenced.

Methods

Primary neuronal cultures

E18 Sprague Dawley rat cortex/hippocampus tissue was obtained from BrainBits®. Preparation and cell plating was performed following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cell culture plates were coated overnight using standard cell culture conditions with poly-D-lysine (50 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich). Rat cortex/hippocampus tissue was incubated in 2 mg/mL papain for 10 minutes at 37°C. Cell dispersal was performed using a sterile glass Pasteur pipette. Sample containing the dispersed cells was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 200 × g for 1 minute. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in NbActiv1TM media (BrainBits®). Cells were plated and incubated under normal cell culture conditions for 7 days to allow differentiation. Media was changed every 3 days.

ADDL preparation

Aβ 1–42 peptide was purchased from California Peptide Research, Inc. ADDL preparation was carried out as previously documented4. Briefly, monomerization of amyloid-beta 1–42 was performed by incubating with 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoror-2-propanol (HFIP) (Sigma-Aldrich) to a final concentration of 1 mM and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The amyloid-beta-HFIP solution was then placed on ice for an additional 10 minutes and aliquoted under a fume hood in Eppendorf tubes which allowed for HFIP evaporation overnight. ADDL preps were performed by resuspending the dried peptide in dimethyl sulfoxide to generate a 5 mM stock. The 5 mM solution was additionally diluted into NbtActiv1TM medium for 24 hours at 5°C and then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 14,000 × g. The resultant supernatant was transferred to a new tube to make a 100 μM ADDL preparation to work from. Protofibrils were formed by modifying the above protocol and leaving the peptide in dimethyl sulfoxide for 24 hours at 37°C and then diluting into NbtActiv1TM.

Gel filtration

Sephadex G-50 beads were suspended and gently swirled in dH2O and allowed to swell at room temperature. A Poly-Prep column (BIO-RAD) was filled with the swollen bead suspension and allowed to settle to a ~10 mL bed volume. The column was then re-equilibrated with PBS. Equal volumes/concentrations of polypeptide samples were added to the top of the bed volume and additional PBS was added through the column. A Bio-Dot microfiltration system (BIO-RAD) was readied containing a nitrocellulose membrane. 100 μL fractions were collected directly into the Bio-Dot microfiltration system. After applying vacuum to affix polypeptides on the membrane surface, the membrane was stained with Ponceau S. Quantification of polypeptide levels in fractions was determined using National Institutes of Health's Image J public domain shareware. Additional characterization showed polypeptide staining was linearly responsive to amount loaded (data not shown).

CAT-SKL

The recombinant protein biologic was expressed and purified as previously described16. It was biotinylated as described in42 to track entry into primary rat cortical/hippocampal neurons. Equal numbers of plated neurons were treated or not with 100 nM biotinylated CAT-SKL for 0, 1, 2, and 24 hours, and harvested in PBS. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and biotinylated CAT-SKL was visualized with streptavidin alkaline-phosphatase (1:1000). Anti-β-actin antibodies (1:10000) were used to identify β-actin which served as a loading control. These antibodies were developed by the nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyphosphate p-toluidine salt (NBT/BCIP) 1-Step Solution (Thermo Scientific).

Catalase staining in neurons

Neurons were plated onto poly-D-lysine coated coverslips as described above and fixed for 10 minutes in 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeablized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Sites that non-specifically bind to antibodies were blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 15 minutes. Cells were then incubated with rabbit anti-catalase antibodies (1:100) for 1 hour, washed with 0.01% Tween-20 in phosphate buffered saline, and incubated with goat anti-rabbit Alexafluor 546 antibodies (1:15000) for 1 hour. Neurons were then mounted with ProLong®Gold antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen). Microscopic analysis was performed using the Zeiss ApoTome Imaging system from the Microscopy, Imaging and Cytometry Resources Core Facility (MICR), at the Wayne State University School of Medicine.

Catalase enzymatic activity and immunoreactivity

Equal numbers of plated neurons were treated or not with 1 μM CAT-SKL for 24 hours. Cells were then washed 3 times and harvested in PBS. Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford Reagent (ThermoScientific). Catalase enzymatic activity was determined by its ability to decompose hydrogen peroxide as previously described15,29. Here, equal protein concentrations of neuronal cultured lysates were added to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 0.02 M imidazole, 0.2% Triton-X, and 0.06% hydrogen peroxide in phosphate buffered saline. Samples were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature and a titanium oxysulfate stop solution was applied. Absorbance units at 405 nm were measured on a microplate reader. For western blots, equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, blocked and probed with anti-catalase antibodies (1:4000) and anti-β-actin antibodies (1:10000).

Cell viability measurements

Rat cortical/hippocampal neurons were plated on a 96-well plate in equal numbers (~100,000 cells) per well. Cells were then pretreated with CAT-SKL (1 μM) for 24 hours or the peroxisome proliferator Wy-14,643 (100 μM) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 hours and then challenged with ADDLs (0.1, 1, and 10 μM) for 24 hours. Cellular viability was determined by measuring metabolic activity using the water soluble tetrazolium dye (WST-1); ELISA based assay kit (Millipore). Absorbance of samples was measured in a microplate reader at 420 nm, with a reference wavelength of 600 nm.

Hydrogen peroxide measurements

Hydrogen peroxide was measured using the Amplex® Red (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine) Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit (Molecular Probes®, Inc.). Rat cortical/hippocampal neurons were plated on to 96-well plates in equal numbers and pretreated with an unrelated control peptide (1 μM), CAT-SKL (1 μM), and/or Wy-14,643 (100 μM) for 24 hours following ADDL treatment (1 μM) for an additional 24 hours. Neurons were washed two times with Hank's balanced salt solution and treated with the Amplex reagent following the manufacturer's protocol. Fluorescence units were analyzed by a microplate reader using excitation and emission wavelengths of 530 and 590 nm, respectively.

Fluorescence microscopy

Primary rat cortical/hippocampal neurons were plated on coated 2 cm2 glass coverslips following the manufacturer's protocol (BrainBits®). All drug applications were performed blindly. After 7 days of differentiation, neurons were treated with the following concentrations: ADDL (1 μM), CAT-SKL (1 μM), Wy-14,643 (100 μM). Slides were washed three times with Hank's balanced salt solution between treatments, and then fixed and stained with the appropriate antibodies. Primary and secondary antibodies employed include: anti-MAP-2 (1:800) (Millipore) coupled with AlexaFluor 488 goat anti-mouse (1:500) (Life Technologies); and anti-PMP70 (1:500) (abcam®) coupled with AlexaFluor 546 goat anti-rabbit (1:15000) (Invitrogen). Microscopic analysis was performed using the Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope located in the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology's microscope facility at the Wayne State University School of Medicine, and Zeiss ApoTome Imaging System from MICR, also at the Wayne State University.

Mitochondrial assays

For mitochondrial ROS and membrane potential assays, neurons were grown and maintained as described above except that coverslips were pre-coated with 100 μg/mL poly-D-lysine. Neurons were 1) pretreated with 1 μM CAT-SKL for 24 hours, and post-treated with 1 μM ADDL for an additional 24 hours, or 2) pretreated with 1 μM ADDL for 24 hours and then post-treated with 1 μM CAT-SKL for an additional 24 hours. Mitochondrial ROS production was determined by using MitoTracker® Red CM-H2XRos (Invitrogen). Medium containing 200 nM of the Mitotracker probe was incubated with neurons for 20 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2, and washed with Hank's balanced salt solution. Mitochondrial membrane potential was determined using the JC-1 mitochondrial potential sensor (Invitrogen). Depolarized mitochondria appear as diffuse green structures. Medium containing 2 μg/mL of the JC-1 dye was incubated with the neurons for 20 minutes, and washed with Hank's balanced salt solution. Cells from both treatment protocols were imaged using the Zeiss ApoTome Imaging system from the MICR.

DNA microarray analysis

Cells were maintained and treated as described above, washed twice and harvested in PBS (2 plates per condition). Total RNA was isolated from cell pellets using an RNeasy Midi Kit from Qiagen. Quantity and quality of all mRNA samples was determined by analysis with the NanoDrop 1000, Agilent Bioanalyzer and the Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent Technologies). Whole-genome expression was measured by a 2-color microarray approach using Agilent SurePrint G3 Rat GE 8X60K arrays (Agilent Technologies) at the Applied Genomics Technology Center Core, Wayne State University. Feature analysis and data extraction was performed using Agilent Feature Extraction software version 11.5.1.1, where for matched biological replicates the log10 expression ratios are CAT-SKL-treated (cy5-labeled) relative to control vehicle-treated sample (cy3-labeled). P values and ratios of detection for Agilent probes (background subtracted and lowess normalized) were averaged for sample replicates. A threshold of significance for ADDL, ADDL → CATSKL and CAT-SKL was set at p < = .01 and a threshold of significance for CATSKL → ADDL was set at p < = .001. The two filters were used to yield relatively similarly sized sets of significant annotated transcripts for each treatment that would be applicable to downstream pathway analysis. Duplicate significant probes were gene-averaged. Systems and pathway-level analysis for enrichment and biological meaning from resulting data was accomplished using Ingenuity Systems software (Redwood City, CA). MIAME compliant data sets were uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) website, and are available through accession number GSE55369.

GST quantification

GSTπ expression was quantified by western blot analysis using Image J software. Cells were washed with Hank's balanced salt solution and harvested into cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling). Protein quantification was made using the Bradford reagent (ThermoScientific). For western blots, equal amounts of protein were loaded to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and blocked with 5% non-fat milk. Antibodies utilized included anti-GSTπ (MBL International Corporation) (1:1000) coupled with goat anti-rabbit-HRP antibodies (1:5000); and anti-β-actin antibodies (1:10000) coupled with goat anti-mouse-AP antibodies (1:5000).

Statistical analysis

Where appropriate, statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism version 5.0 using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When ANOVA indicated significant treatment effects, means were separated using Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test.

Author Contributions

C.R.G. and S.R.T. wrote the manuscript. C.R.G., L.J.T. and S.R.T. designed and performed the experiments. A.B. contributed to microarray data generation analysis, and interpretation. P.A.W. provided biochemical and cell biological expertise, provided experimental insights, and edited the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Figures 1 and 2

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Ken Reese and Kevin Hascup for their expertise at BrainBits®, LLC involving the blinded application of treatments for the microscopy images. Thank you also to Drs. Nick Davis, Marc Fransen, and Ray Mattingly for providing critical insights.

This work was supported by an Albert and Goldye J. Nelson Alzheimer's Endowment Fund Award to SRT. CRG is a recipient of a Thomas C. Rumble University graduate fellowship from Wayne State University.

Footnotes

S.R.T. and P.A.W. are cofounders of EXT Life Sciences, Inc., a Michigan-based biotechnology company that, in conjunction with Wayne State University, endeavors to develop and commercialize transducible catalase-SKL (CAT-SKL).

References

- Holtzman D. M., Mandelkow E. & Selkoe D. J. Alzheimer disease in 2020. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, 1–5 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. Alzheimer's disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3, 1–16 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. & Mucke L. Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell 148, 1204–22 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein W. L. Aβ toxicity in Alzheimer's disease: globular oligomers (ADDLs) as new vaccine and drug targets. Neurochemistry International 41, 345–352 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva M. J., Magalhaes J., Ferreira N. & Almeida M. R. Transthyretin deposition in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Curr Med Chem 19, 2304–11 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polidori M. C. & Nelles G. Antioxidant Clinical Trials in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease - Challenges and Perspectives. Curr Pharm Des 20, (Epub ahead of print) (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R. C. et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 352, 2379–88 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson T., Popescu B. O. & Cedazo-Minguez A. Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer's Disease: Why Did Antioxidant Therapy Fail? Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2014, 1–11 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G. J. Why vitamin E therapy fails for treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 19, 27–30 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev 82, 47–95 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.-L. & Yang C.-M. Role of Redox Signaling in Neuroinflammation and Neurodegenerative Diseases. BioMed Research International 2013, 1–18 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B. The enzyme-substrate compounds of catalase and peroxides. Nature 161, 914–7 (1948). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainshtein B. K., Melik-Adamyan W. R., Barynin V. V., Vagin A. A. & Grebenko A. I. Three-dimensional structure of the enzyme catalase. Nature 293, 411–2 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano C. R. et al. A targeted enzyme approach to sensitization of tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant breast cancer cells. Experimental Cell Research 318, 2014–2021 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M., Terlecky S. R. & Kessel D. A role for hydrogen peroxide in the pro-apoptotic effects of photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol 85, 1491–6 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young C. N. et al. Reactive oxygen species in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-activated primary human keratinocytes: implications for psoriasis and inflammatory skin disease. J Invest Dermatol 128, 2606–14 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undyala V., Terlecky S. R. & Vander Heide R. S. Targeted intracellular catalase delivery protects neonatal rat myocytes from hypoxia-reoxygenation and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Pathol 20, 272–80 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano C. R. & Terlecky S. R. Peroxisomes, cell senescence, and rates of aging. Biochim Biophys Acta 1822, 1358–62 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue L. F. et al. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol 155, 853–62 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean C. A. et al. Soluble pool of Abeta amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 46, 860–6 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Dickson D. W., Trojanowski J. Q. & Lee V. M. The levels of soluble versus insoluble brain Abeta distinguish Alzheimer's disease from normal and pathologic aging. Exp Neurol 158, 328–37 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G. J. & Price P. J. Viable cultured neurons in ambient carbon dioxide and hibernation storage for a month. Neuroreport 7, 1509–12 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G. J., Torricelli J. R., Evege E. K. & Price P. J. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J Neurosci Res 35, 567–76 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepke J. I. et al. Restoration of peroxisomal catalase import in a model of human cellular aging. Traffic 8, 1590–600 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inestrosa N. C. et al. Peroxisome proliferators reduce spatial memory impairment, synaptic failure, and neurodegeneration in brains of a double transgenic mice model of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 33, 941–59 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M. J. et al. Peroxisomal proliferation protects from beta-amyloid neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem 280, 41057–68 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legakis J. E. et al. Peroxisome senescence in human fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell 13, 4243–55 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivashchenko O. et al. Intraperoxisomal redox balance in mammalian cells: oxidative stress and interorganellar cross-talk. Mol Biol Cell 22, 1440–51 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepke J. I., Wood C. S., Terlecky L. J., Walton P. A. & Terlecky S. R. Progeric effects of catalase inactivation in human cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 232, 99–108 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood C. S. et al. Hypocatalasemic fibroblasts accumulate hydrogen peroxide and display age-associated pathologies. Traffic 7, 97–107 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huybrechts S. J. et al. Peroxisome dynamics in cultured mammalian cells. Traffic 10, 1722–33 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton P. A. & Pizzitelli M. Effects of peroxisomal catalase inhibition on mitochondrial function. Front Physiol 3, 108, 1–10 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B. et al. Mitochondria are targets for peroxisome-derived oxidative stress in cultured mammalian cells. Free Radic Biol Med 65, 882–94 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell M. A., Xie C. & Markesbery W. R. Decreased glutathione transferase activity in brain and ventricular fluid in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 51, 1562–6 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli F. et al. Age-dependent roles of peroxisomes in the hippocampus of a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener 8, 8, 1–19 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimini A. et al. Neuronal response of peroxisomal and peroxisome-related proteins to chronic and acute Abeta injury. Curr Alzheimer Res 6, 238–51 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou J. et al. Peroxisomal alterations in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 122, 271–83 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garc et al. Deconstructing Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer Disease. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2013, 1–13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H. et al. Mitochondrial alterations near amyloid plaques in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. J Neurosci 33, 17042–51 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai K. et al. Mitochondrial Abnormalities in Alzheimer's Disease. The Journal of Neuroscience 21, 3017–3023 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Oxidants, antioxidants and the current incurability of metastatic cancers. Open Biol 3, 120144, 1–9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlecky S. R. In vitro analysis of peroxisomal protein import. Curr Protoc Cell Biol Chapter 11, Unit 11.15.1–11.15.10 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Figures 1 and 2