ABSTRACT

Regulated, programmed cell death is crucial for all multicellular organisms. Cell death is essential in many processes, including tissue sculpting during embryogenesis, development of the immune system and destruction of damaged cells. The best-studied form of programmed cell death is apoptosis, a process that requires activation of caspase proteases. Recently it has been appreciated that various non-apoptotic forms of cell death also exist, such as necroptosis and pyroptosis. These non-apoptotic cell death modalities can be either triggered independently of apoptosis or are engaged should apoptosis fail to execute. In this Commentary, we discuss several regulated non-apoptotic forms of cell death including necroptosis, autophagic cell death, pyroptosis and caspase-independent cell death. We outline what we know about their mechanism, potential roles in vivo and define outstanding questions. Finally, we review data arguing that the means by which a cell dies actually matters, focusing our discussion on inflammatory aspects of cell death.

KEY WORDS: MLKL, RIPK3, Mitochondria, Necroptosis, Pyroptosis

Introduction

In all animals, regulated cell death plays key roles in a variety of biological processes ranging from embryogenesis to immunity. Too much or too little cell death underpins diverse pathologies, including cancer, autoimmunity, neurodegeneration and injury. Generally, the means by which a cell dies can be divided into passive – occurring as a result of overwhelming damage – or active, such that the cell itself contributes to its own demise. In this Commentary, we focus upon active forms of cell death that constitute cellular suicide and utilise specific molecular machinery to kill the cell. Unquestionably, apoptosis is the best-characterised and most evolutionary conserved form of programmed cell death. Apoptosis requires the activation of caspase proteases in order to bring about rapid cell death that displays distinctive morphological and biochemical hallmarks, and has been reviewed extensively (Green, 2011; McIlwain et al., 2013; Parrish et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2008). Increasing interest has recently centred upon cell death programmes other than apoptosis. As we discuss here, non-apoptotic cell death can serve to back up failed apoptosis or occur independently of apoptosis. Importantly, the ability to engage non-apoptotic cell death might provide new opportunities to manipulate cell death in a therapeutic context – for example, to enable the killing of apoptosis-resistant cancer cells. In this Commentary, we discuss major forms of non-apoptotic programmed cell death, how they intersect with one another and their occurrence and roles in vivo, and we outline outstanding questions. Following this, we ask whether it really matter how a cell dies. Specifically, we focus on how the mode of cell death impacts on immunity and inflammation.

Necroptosis

Various stimuli can engage a non-apoptotic form of cell death called necroptosis (Degterev et al., 2005). Although morphologically resembling necrosis, necroptosis differs substantially in that it is a regulated active type of cell death (Galluzzi et al., 2011; Green et al., 2011). As discussed below, several stimuli that trigger apoptosis, under conditions of caspase inhibition, can trigger necroptosis. Indeed, it remains highly debated whether necroptosis ever occurs unless caspases are actively inhibited, for example by virally encoded caspase inhbitors. The recent identification of key molecules in this process has led to an upsurge in interest in the fundamental biology and in vivo roles that necroptosis can play. Our discussion will be restricted to necroptosis that requires the protein kinase receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) (Galluzzi et al., 2012). However, it is important to note that various RIPK3-independent cell death mechanisms have also been termed necroptosis, and those should not be confused with our use of the term here.

Initiating necroptosis

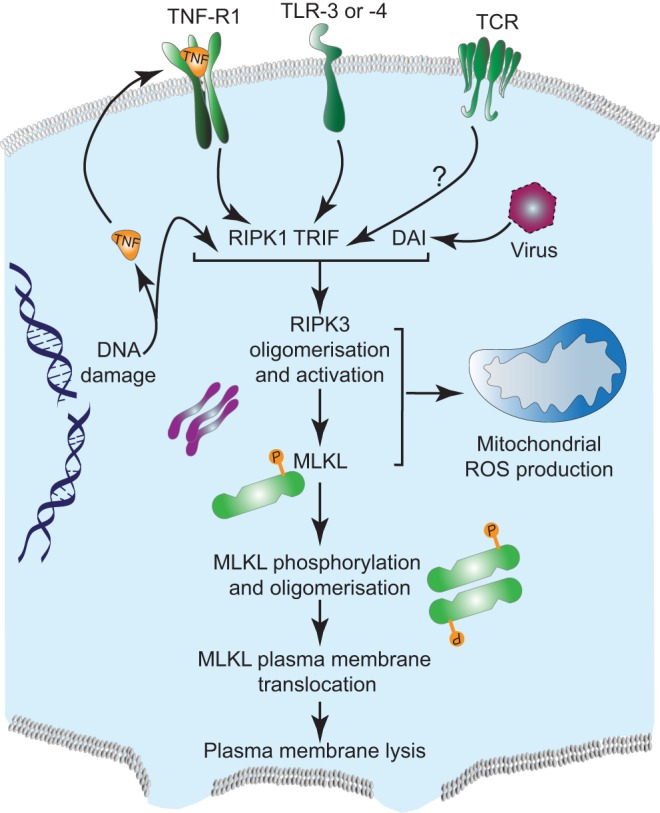

The best-characterised inducers of necroptosis are death receptor ligands, in particular, tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Although named because of its necrosis-inducing properties, most TNF research has instead focused upon its pro-inflammatory and apoptotic functions. It has been known for many years that, in some cell-types, TNF can also induce a non-apoptotic form of cell death (subsequently termed necroptosis) (Laster et al., 1988). It is important to note that, besides TNF, other death-receptor ligands, such as Fas, have also been shown to induce necroptosis under conditions of caspase inhibition (Matsumura et al., 2000). Recently, key molecular components of necroptosis signalling have been identified; these include the two related kinases RIPK1 and RIPK3 (Cho et al., 2009; He et al., 2009; Holler et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2009). RIPK3 is essential for TNF-induced necroptosis, whereas RIPK1 appears dispensable in some settings (Moujalled et al., 2013; Upton et al., 2010). Besides necroptosis, RIPK1 also has a well-established role in mediating both TNF-dependent nuclear factor κB (NFκB) activation and apoptosis (Ofengeim and Yuan, 2013). During the initiation of necroptosis, current data supports a simplified model whereby TNF receptor–ligand binding indirectly, through the recruitment of the adaptor protein TRADD, leads to an interaction between RIPK1 and RIPK3 (Moriwaki and Chan, 2013). RIPK1 and RIPK3 interact through receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic interaction motifs (RHIM) present in both proteins. This leads sequentially to the activation of RIPK1 and RIPK3 and the formation of a complex called the necrosome. The formation of the necrosome is highly regulated by ubiquitylation. In simplistic terms, the ubiquitin ligases cIAP-1 and cIAP-2 negatively affect its formation by ubiquitylating RIPK-1, whereas the deubiquitylase CYLD counteracts this and promotes necrosome formation (Geserick et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2008). In addition to death-receptor ligands, other stimuli can also trigger RIPK3-dependent necroptosis, either directly (through adaptors) or indirectly (e.g. through expression of TNF); these include engagement of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 3 and TLR-4, T-cell receptor (TCR) ligation, DNA damage and viral infection (Ch'en et al., 2008; Feoktistova et al., 2011; He et al., 2011; Tenev et al., 2011) (Fig. 1). In the case of TLRs, the RHIM-domain-containing protein TRIF bridges TLRs to RIPK3 activation, whereas the DNA-binding RHIM-containing protein DAI is required for RIPK3 activation and necroptosis following murine cytomegalovirus infection (He et al., 2011; Upton et al., 2012). RIPK3 can also be activated and trigger necroptosis following DNA damage. In this setting, activation of RIPK3 occurs at a multi-protein complex, called the ripoptosome, and is dependent upon RIPK1 (Feoktistova et al., 2011; Tenev et al., 2011). The engagement of cell death by DNA damage might involve the production of TNF (Biton and Ashkenazi, 2011) or might occur in a TNF-independent manner (Tenev et al., 2011). Likewise, TCR-induced RIPK3 activation also appears to require RIPK1, but how the TCR initiates necroptosis is not known (Ch'en et al., 2008).

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of RIPK3-mediated necroptosis. Various stimuli including DNA damage, viral infection, engagement of receptors, such as TCR, TLR or TNFR, lead to RIPK3 activation. Activation of RIPK3 leads to its oligomerisation and downstream phosphorylation of MLKL. This also results in mitochondria-dependent ROS production. Upon phosphorylation, MLKL oligomerises and translocates to the plasma membrane and causes its lysis.

Executing necroptosis

Following initial activation, the RIPK1–RIPK3 complex propagates a feed-forward mechanism leading to the formation of large filamentous structures that share striking biophysical similarities to β-amyloids (Li et al., 2012) (Fig. 1). Generation of these amyloid structures is dependent upon RHIM-domain interactions between the two proteins. Importantly, by simultaneously increasing RIPK3 activity, propagation of these amyloid structures robustly engages necroptosis. Potentially, modulating the extent of amyloid formation (and RIPK3 activity) could dictate the pro-killing functions of RIPK3 versus its non-lethal roles in inflammation (discussed below). It remains unclear whether similar amyloid structures are formed (and required) for necroptosis that is engaged by other stimuli, such as TLRs. Moreover, given the stability of these proteinaceous structures, they might also contribute to cellular toxicity even in the absence of RIPK3 activity.

The mechanism by which RIPK3 kinase activity actually executes cell death has been elusive until recently. The pseudokinase mixed-lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) has been identified as a key downstream factor in RIPK3-dependent necroptosis; its importance is underscored by the finding that genetic ablation of MLKL imparts complete resistance to RIPK3-dependent necroptosis (Murphy et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2012). MLKL does not regulate necrosome assembly per se but instead is required for RIPK3 to kill cells, following its binding and phosphorylation by RIPK3. Importantly, a mutant of MLKL that mimics its active (RIPK3-phosphorylated) form directly induces cell death, even in RIPK3-deficient cells – this strongly implies that MLKL is the key RIPK3 substrate in necroptosis (Murphy et al., 2013).

How necroptosis is executed remains controversial. Various studies have proposed a role for either reactive oxygen species (ROS) or rapid depletion of cellular ATP in the execution of necroptosis (Schulze-Osthoff et al., 1992; Zhang et al., 2009). In turn, this has implicated mitochondrial dysfunction as a key event in the necroptotic execution. Supporting this idea, following its formation, the RIPK3- and MLKL-containing necrosome has been found to translocate to mitochondrially associated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes (MAMs), although it remains unclear whether translocation is required for death (Chen et al., 2013). Two mitochondrial proteins, PGAM5 (a mitochondrial phosphatase) and Drp-1 (also known as DNM1L, a protein required for mitochondrial fission) have been suggested as downstream components of necrosome signalling (Wang et al., 2012). Following RIPK3-dependent phosphorylation, the short isoform of PGAM5 (PGAM5s) activates Drp-1, leading to extensive mitochondrial fission, ROS production and necroptosis (Wang et al., 2012). However, the role of ROS in executing necroptosis remains controversial; several studies have failed to find a protective effect of ROS scavengers or found that ROS scavengers can also display off-target protective effects (Festjens et al., 2006). Our recent study has directly investigated the role of mitochondria in necroptosis by generating mitochondria-deficient cells (Tait et al., 2013). Here, we utilised Parkin-mediated mitophagy to effectively deplete mitochondria. Surprisingly, although mitochondria-depletion prevents necroptosis-associated ROS, it has no impact on the kinetics or extent of necroptosis that is induced either by TNF or by direct activation of RIPK3. As such, this strongly argues against mitochondria as key effectors in the execution of necroptosis. Supporting a mitochondria-independent execution mechanism, recent work has found that MLKL can permeabilise the plasma membrane (Cai et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2014). Following RIPK3-mediated phosphorylation, MLKL oligomerises and translocates to the plasma membrane leading to its breakdown. How MLKL permeabilises the plasma membrane is unclear but this process might require functional interaction with cationic channels (such as TRPM7) that allow cation influx (Cai et al., 2014). Collectively, a key remaining question is whether the general mechanism of necroptosis execution is conserved between different cell types and/or following different stimuli. Moreover, although necroptosis-associated ROS might not be required for necroptosis, an unexplored question is whether they impact on how the immune system reacts to a necroptotic cell, as has been observed for apoptotic cells (Kazama et al., 2008) (Box 1).

Box 1. Outstanding questions in non-apoptotic cell death research.

Necroptosis

How is necroptosis executed, is there a canonical pathway or are there cell- or stimulus-type differences?

When does necroptosis occur In vivo and what are its roles?

Does necroptosis ever occur without caspase activity being inhibited?

Can a method be developed to specifically detect necroptosis In vivo?

Why is necroptosis so interconnected with apoptosis?

Autophagic cell death

Does autophagic cell death occur in higher vertebrates?

If so, what are its roles?

What dictates bifurcation between autophagy as a pro-survival versus a pro-death mechanism?

Pyroptosis

How is caspase-1 activity toggled between its pro-inflammatory and its pro-death function?

How is pyroptosis executed and what are the key caspase substrates?

What is the role of pyroptosis?

How much does caspase-11 contribute to pyroptosis independently of caspase-1?

Caspase-independent cell death

Does caspase-independent cell death actually occur In vivo?

Can cells survive mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation and evade CICD?

Survival of some Bax- and Bak-deficient mice to adulthood poses several questions:

Are there Bax- and Bak-independent pathways to MOMP?

Are there alternative (known or otherwise) cell death pathways that can substitute for apoptosis?

Is cell death not always essential for development?

Interconnections between apoptosis and necroptosis

Apoptosis and necroptosis are deeply intertwined; some apoptosis-inducing stimuli can also initiate necroptosis, typically when caspase function is inhibited. The best-known example is TNF, which can engage either apoptosis or necroptosis. Bifurcation of apoptosis and necroptosis is dictated by caspase-8 activity; active caspase-8 suppresses necroptosis by cleaving substrates, including RIPK1, RIPK3 and CYLD (Feng et al., 2007; O'Donnell et al., 2011; Rébé et al., 2007). Under conditions of caspase inhibition (by either chemical or genetic means), TNF can trigger necroptosis in RIPK3-proficient cells. In vivo support of this model comes from the finding that embryonic lethality caused by caspase-8 or FADD loss in vivo can be completely rescued by RIPK3 ablation (Dillon et al., 2012; Kaiser et al., 2011; Oberst et al., 2011). Biochemical and in vivo data support a model whereby the ability of caspase-8 to inhibit necroptosis is dependent upon its heterodimerisation with FLIP – essentially a catalytically inactive form of caspase-8 (Oberst et al., 2011). Caspase-8 homodimers engage apoptosis, whereas caspase-8–FLIP heterodimers suppress necroptosis. It remains unclear what regulates the different outcomes of caspase-8 homodimer versus caspase-8–FLIP heterodimer activity, but possibilities include differences in cleavage specificities, activity or subcellular localisation (Oberst and Green, 2011). In addition to TNF, caspase-8 activity and FLIP levels are key to regulating necroptosis that is engaged by other stimuli, including DNA damage and TLR ligation (Feoktistova et al., 2011; Tenev et al., 2011). Recent data demonstrates that RIPK3 activity dictates whether a cell dies through apoptosis or necroptosis. Interestingly, unlike RIPK3-deficient mice (which are viable and ostensibly normal), expression of a kinase-inactive form of RIPK3 results in embryonic lethality (Newton et al., 2014). This lethality can be rescued by simultaneous knockout of either RIPK1 or caspase-8, arguing that kinase-inactive RIPK3 reverses signals through RIPK1 to activate caspase-8 and apoptosis. Importantly, these data formally demonstrate an in vivo requirement for RIPK3 activity in necroptosis. Exactly how RIPK3 is activated to suppress apoptosis without triggering necroptosis remains unclear, but these findings have important implications for the therapeutic application of RIPK3 inhibitors.

In vivo functions of necroptosis

What are the physiological roles of necroptosis? Mice deficient in RIPK3 or MLKL display no overt phenotype but are protected from chemically induced pancreatitis – an in vivo model of inflammation (He et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2013). Recent data has clearly shown a vital role for RIPK3 during embryogenesis, but this is only revealed in the absence of caspase-8 or FADD. In adult mice, disabling the ability of caspase-8 to inhibit RIPK3 (by either caspase-8 or FLIP deletion) in specific organs also leads to RIPK3-dependent inflammation and necrosis in the intestine and skin (Bonnet et al., 2011; Panayotova-Dimitrova et al., 2013; Weinlich et al., 2013; Welz et al., 2011). Recent studies also argue that RIPK3 can directly induce inflammation even in the absence of cell death, thereby complicating direct implication of RIPK3-dependent necroptosis in any given process (Kang et al., 2013; Vince et al., 2012). In one study, RIPK3 was found to activate inflammasome-dependent interleukin (IL)-1β production and that this required MLKL and PGAM5, downstream mediators implicated in necroptosis (Kang et al., 2013). A variety of pathologies have been linked to necroptosis and RIPK3, especially its role in ischaemic reperfusion injury in various organs (Linkermann et al., 2013).

Perhaps the best evidenced role for necroptosis in vivo is in the regulation of viral infection. In contrast to wild-type mice, infection of RIPK3-null mice with vaccinia virus leads to rapid lethality (Cho et al., 2009). Co-evolution of viruses and immunity has been likened to an ‘arms race’ between viruses and the immune system. Many viruses, in particular large double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, such as vaccinia virus, encode inhibitors of apoptosis (Smith et al., 2013). Pertaining to necroptosis, potent viral inhibitors of caspase-8 exist, such as the coxpox-encoded protein CrmA (Ray et al., 1992) and the herpes-virus-encoded vFLIP proteins (Thome et al., 1997). Consequently, it might be that necroptosis evolved as a host back-up mechanism to trigger cell death in virally infected cells. Alternatively, viral induction of necroptosis might actually serve the virus by helping to shut down the host inflammatory response. Interestingly, CrmA preferentially inhibits caspase-8 homodimers over caspase-8–FLIP heterodimers, thereby allowing the inhibition of both caspase-8-regulated apoptosis and necroptosis (blocked by caspase-8–FLIP) (Oberst et al., 2011). Viral proteins containing RHIM domains, such as murine cytomegalovirus (CMV)-encoded vIRA have also been identified – these directly inhibit necroptosis by competitively disrupting the RHIM–RHIM interactions that are required for necroptosis (Upton et al., 2012).

Autophagic cell death

Macroautophagy (hereafter called autophagy) is a lysosome-dependent process that degrades various cargoes varying from molecules to whole organelles (Mizushima, 2011). During autophagy, an isolation membrane forms in the cytoplasm, engulfing cytosolic cargo to create an autophagosome. Mature autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes leading to a breakdown of engulfed material, allowing macromolecules to be recycled. Autophagy is a complex process carried out by dedicated proteins (called ATG proteins). At the organismal level, autophagy is crucial to many processes, including development, immunity and aging (Choi et al., 2013). Autophagy has long been linked with a form of cell death, called autophagic or type II cell death (Das et al., 2012). However, with some notable exceptions, in most instances autophagy appears to be associated with, rather than actually causing, such cell death. Most often, autophagy is primarily a pro-survival stress response, for example, it is engaged under starvation conditions. As such, some conditions that kill cells are preceded by extensive autophagy that is visible even in dying cells, leading to the false interpretation that autophagy contributed to the death of the cell (Kroemer and Levine, 2008). These points notwithstanding, various reports have shown that autophagy itself is required for cell death in certain settings.

Autophagic cell death in non-vertebrates

The cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum does not undergo apoptotic cell death and therefore represents an ideal organism in which to study non-apoptotic cell death processes. In nutrient-replete conditions, Dictyostelium exists as a unicellular organism; however, following starvation, thousands of cells aggregate, forming fruiting bodies that support apical spores. Interestingly, the supporting stalk cells undergo cell death that can be prevented by genetically inactivating autophagy, implicating autophagic cell death in this process (Kosta et al., 2004; Otto et al., 2003).

A pro-death role for autophagy has been also been characterised in the fruit-fly Drosophila melanogaster. Towards the end of larval development, various tissues, including the mid-gut and salivary glands, undergo ordered destruction (Jiang et al., 1997). Although Drosophila possess intact apoptotic pathways, cellular destruction in the midgut does not require caspase activity but instead requires autophagy (Denton et al., 2009). In contrast, both autophagy and caspase-dependent apoptosis contribute to salivary gland destruction (Berry and Baehrecke, 2008). Furthermore, upregulation of ATG1 is sufficient to drive cell death in a caspase-independent manner in the Drosophila salivary gland. Interestingly, recent work has also found that autophagy contributes to cell death in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Wang et al., 2013). Deletion of various ATG genes (preventing autophagy) inhibits cell death induced by genotoxic stress in germ cells, and physiological cell death in various tissues when caspase activity is compromised.

Autophagic cell death in higher eukaryotes

Although in vivo evidence is lacking, there are several examples of cell death occurring in vitro in an autophagy-dependent manner in higher eukaryotes. Often autophagic cell death is only revealed in the absence of apoptotic pathways. For example, cells deficient in Bax and Bak (also known as Bak1), which are unable to initiate mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis, can undergo death in a manner dependent upon the key autophagy proteins Beclin-1 and ATG5 (Shimizu et al., 2004). L929 cells have been reported to undergo cell death that is dependent upon Beclin-1 and ATG7 in response to inhibition of caspase-8 (Yu et al., 2004). However, rather than directly executing death, autophagy increases ROS to cytotoxic levels by degrading catalase following caspase inhibition (Yu et al., 2006). Along similar lines, and of possible clinical importance, inhibition of caspase-10 has recently been found to induce autophagy-dependent cell death in multiple myeloma (Lamy et al., 2013). In some instances, even in the presence of intact apoptosis, cell death in vitro has been shown to depend upon autophagy. For example, Beclin-1 overexpression can kill cells in an autophagy-dependent manner because it can be blocked by knockdown of ATG5 (Pattingre et al., 2005). Accordingly, a cell-permeating Beclin-1-derived peptide has recently been found to induce cell death – termed autosis – in an autophagy-dependent but apoptosis- and necroptosis-independent manner (Liu et al., 2013).

Cell death induced by the tumor suppressor p53 can similarly require autophagy and is induced by p53-dependent upregulation of a lysosomal protein called DRAM (Crighton et al., 2006). However, at least in the case of DRAM (and perhaps following Beclin-1 upregulation), the requirement for autophagy in cell death seems to be to initiate apoptosis, rather than execute death itself. Interestingly, in some settings, oncogenic H-RasV12 can induce autophagic cell death that displays no hallmarks of apoptosis nor a requirement for downstream apoptotic signalling components (Elgendy et al., 2011). Because knockdown of various autophagy components blocks this event, allowing clonogenic survival, this type of death might also represent ‘true’ autophagic death.

Interplay between autophagy and other cell death pathways

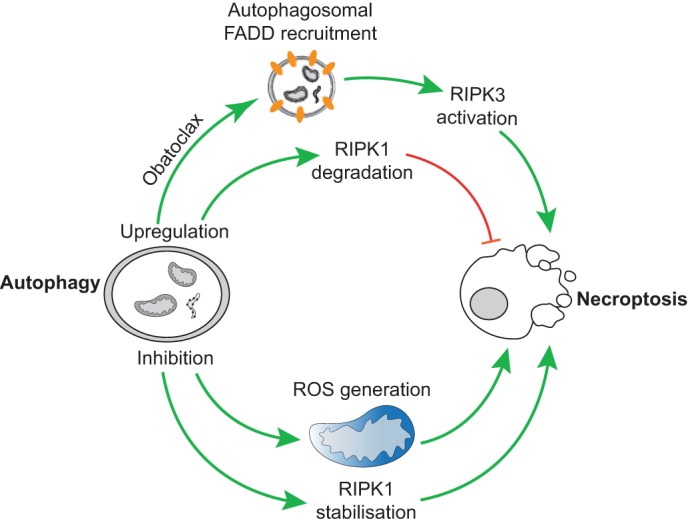

Similar to necroptosis, there are numerous interconnections between autophagy and other cell death processes. As discussed above, caspases can actively suppress necroptosis. Autophagy has also been shown to directly inhibit necroptosis by degrading the kinase RIPK1 (Bray et al., 2012). In that study, chemical initiation of autophagy, while inhibiting its completion, led to robust RIPK1- and RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. In addition to preventing RIPK1 degradation, inhibiting autophagy has been found to generate mitochondrial ROS that appeared to be required for necroptosis in this setting (Fig. 2). Along similar lines, a recent study has found that the BCL-2 inhibitor Obatoclax (also called GX15-070) can induce autophagy that is required for necroptosis (Basit et al., 2013) (Fig. 2). How Obatoclax stimulates autophagy remains unclear; Obatoclax can have off-target effects and its pro-autophagic function does not appear to be through antagonizing BCL-2 function. Obatoclax-induced necroptosis is dependent upon autophagosomal recruitment of FADD with subsequent binding and activation of RIPK1 leading to RIPK3 activation and necroptosis. An untested possibility is that FADD might be recruited to the autophagosomal membrane by ATG5, because both have previously been found to interact with one another (Pyo et al., 2005).

Fig. 2.

Interplay between autophagy and necroptosis. Upregulation of autophagy by Obatoclax can lead to FADD recruitment to autophagosomal membranes and RIPK3 activation resulting in necroptosis (upper part). Conversely, upregulation of autophagy can also lead to RIPK1 degradation and inhibition of necroptosis (lower part). Stimulation of autophagy, but inhibiting its completion, leads to RIPK1 stabilisation and ROS production, both of which contribute to the induction of necroptosis.

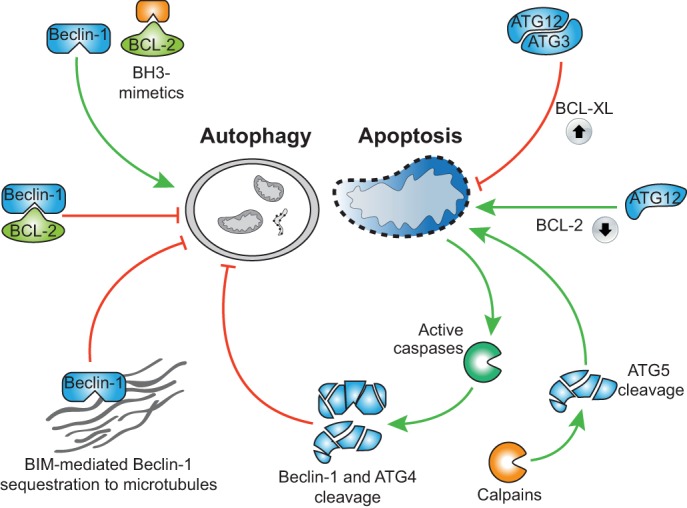

Substantial crosstalk also exists between apoptosis and autophagy (Fig. 3). The archetypal and best-known example is Beclin-1, a key component of the autophagy initiation machinery. Beclin-1 was originally identified as a BCL-2-binding protein (Liang et al., 1998). Accordingly, anti-apoptotic proteins of the BCL-2 family can inhibit autophagy through direct binding of Beclin-1. Beclin-1 possesses a BH3-only domain (present in pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins) that is required for its interaction with anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins (Fig. 3). Rather puzzlingly, although BCL-2 can inhibit autophagy, Beclin-1 does not appear to inhibit the anti-apoptotic function of BCL-2 (Ciechomska et al., 2009). The reasons are unclear but might be due to relatively low affinity of Beclin-1 for BCL-2 relative to other BH3-only proteins. Supporting an anti-autophagic role for BCL-2 proteins, BH3-only proteins or compounds that mimic them (so-called BH3 mimetics) can also induce autophagy by displacing Beclin-1 from BCL-2 (Maiuri et al., 2007). The BH3-only protein Bim has also been found to neutralize Beclin-1 by sequestering it onto microtubules (Luo et al., 2012).

Fig. 3.

Interplay between autophagy and apoptosis. BCL-2 sequesters Beclin-1, thereby inhibiting autophagy that can be reversed by BH3 mimetics. Furthermore, Bim can sequester Beclin-1 onto microtubules, which also inhibits autophagy (shown on the left). In contrast, ATG12 conjugation to ATG3 enhances BCL-XL expression, thereby inhibiting apoptosis. Unconjugated ATG12 can act in a manner like BH3-only proteins and induce mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis. Calpain-mediated cleavage of ATG5 results in the liberation of a proapoptotic fragment of ATG5 that leads to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation and cell death. In addition, caspase-mediated cleavage of autophagy proteins inhibits autophagy (shown on the right).

Autophagy or autophagy proteins can also influence apoptosis. Non-canonical conjugation of the ubiquitin-like protein ATG12 to ATG3 has been found to inhibit apoptosis by upregulating anti-apoptotic BCL-XL (Radoshevich et al., 2010). Furthermore, the unconjugated form of ATG12 mimics BH3-only proteins and can neutralize anti-apoptotic BCL-2 function (Radoshevich et al., 2010). Moreover, calpain-mediated cleavage of ATG5 leads to the generation of pro-apoptotic cleavage products that display BH3-protein-like properties (Yousefi et al., 2006).

During the degradation phase of apoptosis, various key autophagy, proteins including Beclin-1 and ATG4, are cleaved by caspases (Betin and Lane, 2009; Luo and Rubinsztein, 2010) (Fig. 3). Consequently, autophagy is suppressed as the cell undergoes apoptosis. Although perhaps not determining whether the cell dies or not, shutting down autophagy possibly might influence how the immune system responds to the dying cell (Box 1).

Pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is a caspase-dependent form of programmed cell death that differs in many respects from apoptosis. Unlike apoptosis, it depends on the activation of caspase-1 (Hersh et al., 1999; Miao et al., 2010) or caspase-11 (caspase-5 in humans) (Kayagaki et al., 2011). As the name suggests, pyroptosis is an inflammatory type of cell death. The best-described function for caspase-1 is its key role in the processing of inactive IL-β and IL-18 into mature inflammatory cytokines. Although it is required for cytokine maturation, caspase-1 can also trigger cell death in some circumstances (Bergsbaken et al., 2009). Here, we discuss the molecular basis of pyroptosis, its effects and possible roles in vivo.

Pyroptosis initiation and execution

Execution of pyroptosis markedly differs from apoptosis both at the biochemical and morphological level. Caspase-1 itself is primarily defined as a pro-inflammatory caspase and is not required for apoptosis to occur. Although caspase-1 can in some instances initiate apoptosis, caspase-1-driven pyroptosis does not lead to cleavage of substrates of typical caspases, such as PARP1 or ICAD (also known as DFFA). Furthermore, mitochondrial permeabilisation typically does not occur during pyroptosis. Instead, pyroptosis is associated with cell swelling and rapid plasma membrane lysis. In response to bacterial infection or toxins, plasma membrane pores have been found to form in a caspase-1-dependent manner leading to swelling and osmotic lysis (Fink and Cookson, 2006). Interestingly, similar to apoptosis, nuclear DNA undergoes extensive fragmentation; although the underlying mechanism of DNA fragmentation during pyroptosis remains elusive, it does not appear to involve CAD, the DNase activated by apoptotic caspases (Bergsbaken and Cookson, 2007; Fink et al., 2008; Fink and Cookson, 2006). Irrespective of its pro-inflammatory or pro-death functions, caspase-1 is activated at complexes termed inflammasomes that are formed in response to detection of diverse molecules, including bacterial toxins and viral RNA (Henao-Mejia et al., 2012). Upon assembly, inflammasomes activate caspase-1 by inducing its dimerization. However, how active caspase-1 kills a cell remains a complete mystery – to date no key substrates have been identified that would account for a rapid pyroptotic event.

In vivo functions of pyroptosis

By various strategies, bacterial and viral pathogens can subvert caspase-1-mediated IL-1β and IL-18 processing, thereby dampening the host inflammatory response and facilitating infection (Bergsbaken et al., 2009). Although purely speculative, pyroptosis might represent a host strategy to subversion of caspase-1 activation by re-directing its activity towards killing the cell as opposed to solely generating pro-inflammatory cytokines. Priming of host macrophages by invading microbes or prior activation of macrophages sensitises them to pyroptosis, at least in part, by upregulating components of the caspase-1 activation machinery. This suggests that the level of active caspase-1 might define whether inflammation or death is engaged. Finally, although pyroptosis might indeed be pro-inflammatory, it is unclear what advantage (in terms of inflammation) this would provide over and above the role of caspase-1 in IL-1β and IL-18 maturation. Perhaps the main function of pyroptosis is simply to control infection by killing the host cell. Alternatively, it is possible that pyroptosis is required for the release of the mature, inflammatory cytokines.

Caspase-independent cell death

Pro-apoptotic triggers that cause mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation (MOMP) also engage cell death even in the absence of caspase activity – so called caspase-independent cell death (Tait and Green, 2008). As such, mitochondrial permeabilisation is often viewed as a ‘point-of-no-return’. Caspase-independent cell death (CICD) clearly shares similarities to apoptosis (namely mitochondrial permeabilisation) but is distinct morphologically, biochemically and kinetically. Additionally, it is likely that the mode of CICD varies between cell types, in contrast to canonical mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis. Below, we discuss how mitochondrial permeabilisation causes CICD, how cells might evade CICD and its occurrence and role in vivo.

Executing or evading CICD

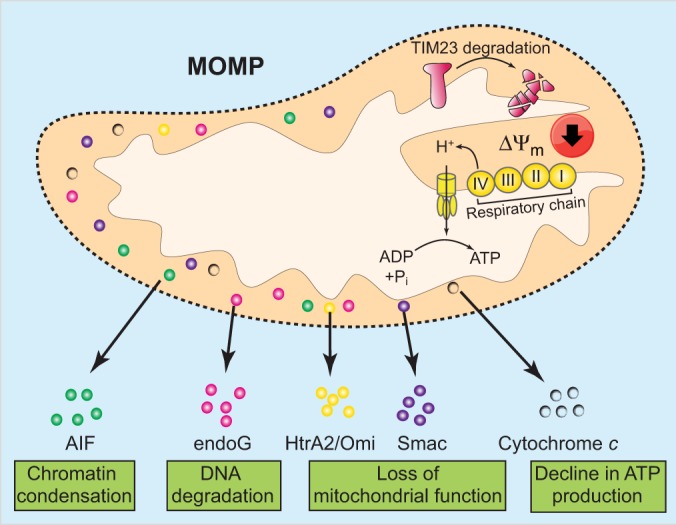

Two opposing models argue that mitochondrial permeabilisation can either actively cause CICD or that cells die owing to loss of mitochondrial function. An active role for mitochondria has been proposed through the release of toxic proteins, such as AIF, endonuclease G (endoG) or HtrA2/Omi from the mitochondrial intermembrane space, leading to death in a caspase-independent manner (Fig. 4). However, definitive proof that these proteins mediate CICD is lacking and cells devoid of these proteins do not display increased resistance towards CICD (Bahi et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2003). Moreover, the release of proteins, such as AIF or endoG, from the mitochondria appears to actually require caspase activity, thereby precluding their role in CICD (Arnoult et al., 2003; Munoz-Pinedo et al., 2006).

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of mitochondrial permeabilisation-mediated caspase-independent cell death. Following mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation, various intermembrane-space proteins such as Smac, HtrA2/Omi and cytochrome c are released into the cytoplasm. Some of these, such as AIF and endoG, might actively kill the cell in a caspase-independent manner. Over time, mitochondrial functions also decline following outer membrane permeabilisation. This dysfunction includes a loss of mitochondrial protein import due to cleavage of TIM23 and degradation of cytochrome c. Collectively, these events lead to progressive loss of respiratory chain function (complex I to IV) and reduced mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). Ultimately, this leads to bioenergetic crisis and cell death.

Alternatively, CICD might occur as a result of progressive loss of mitochondrial function. In agreement with this model, following mitochondrial permeabilisation, there is a rapid loss in the activity of respiratory complexes I and IV (Lartigue et al., 2009). Exactly why these complexes lose function is unclear but it might be due to degradation of one or several subunits of these multi-protein complexes. Post-mitochondrial permeabilisation-dependent cleavage of TIM23, a crucial subunit of the mitochondrial inner membrane translocase complex, and degradation of cytochrome c also contributes to breakdown of mitochondrial function (Goemans et al., 2008; Ferraro et al., 2008) (Fig. 4).

A third possibility encompasses both active and loss-of-function roles for mitochondria in promoting CICD. Reversal of mitochondrial FoF1 ATPase function, leading to ATP hydrolysis, as occurs following MOMP, actually consumes ATP in order to maintain mitochondrial membrane potential. Mitochondria might therefore act as an ATP sink, contributing to ATP depletion and therefore accelerating CICD. In support of an active role for mitochondria, cells depleted of mitochondria can survive for at least 4 days, which typically is longer than the normal kinetics of CICD (Narendra et al., 2008; Tait et al., 2013).

Although often a death sentence, cells can sometimes survive mitochondrial permeabilisation in the absence of caspase activity. Survival under these conditions might have physiological functions, for example, by promoting the life-long survival of post-mitotic cells. Indeed, certain types of neurons and cardiomyocytes do not effectively engage caspase activity following MOMP and can survive mitochondrial permeabilisation (Deshmukh and Johnson, 1998; Martinou et al., 1999; Vaughn and Deshmukh, 2008; Wright et al., 2007).

In some circumstances, cells can undergo MOMP and even proliferate, provided caspase activity is inhibited (Colell et al., 2007). This has potentially important consequences for cancer cells that display defects in the activation of caspases. How can a cell survive the catastrophic consequences of engaging MOMP? Various hurdles must be passed; perhaps most importantly, cells must generate a healthy population of mitochondria. Recently, we have found that mitochondrial permeabilisation can be incomplete, in that some mitochondria remain intact (Tait et al., 2010). These mitochondria repopulate the cell thereby enabling cell survival. The outcome of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis can also be promoted by autophagy, although the underlying reasons for this are unclear. In the absence of caspase activity, apoptotic mitochondrial permeabilisation is associated with enhanced autophagy through upregulation of ATG12 (Colell et al., 2007). In this context, autophagy acts as a pro-survival mechanism, allowing cells to overcome the bioenergetic crisis that mitochondrial permeabilisation enforces (Colell et al., 2007). The cytoprotective role of autophagy is probably multifaceted, but likely one additional key function is to remove permeabilised mitochondria. Finally, compensatory mechanisms for the failing bioenergetic function of mitochondria must exist. In line with this, GAPDH has been found to protect cells from CICD in a manner that is, in part, dependent upon its glycolytic function (Colell et al., 2007).

In vivo occurrence and roles of CICD

Similar to other forms of non-apoptotic cell death, effective means to detect CICD in vivo is lacking. Comparative morphological analysis of interdigital cell death between wild-type and mice that lack Apaf1 (and are therefore unable to activate caspases and trigger apoptosis) suggests that up 10% of cells in wild-type mice undergo CICD, implying that CICD might be a significant mode of cell death in vivo (Chautan et al., 1999). Bax and Bak are required for MOMP and their combined deletion often leads to early embryonic lethality at embryonic day (E)7 (Wei et al., 2001). In contrast, deletion of Apaf1 leads to postnatal lethality, arguing that CICD can substitute for mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis, at least during embryonic development (Cecconi et al., 1998; Yoshida et al., 1998). In higher vertebrates, CICD might also form an effective tumour suppressor mechanism by killing cells that have disabled caspase function. Consequently, inhibition of apoptosis and CICD might be expected to promote tumorigenesis. Indeed, in some settings, disabling caspase activation downstream of MOMP can promote cancer; presumably these cells can also subvert CICD (Schmitt et al., 2002). Moreover, inhibition of CICD has been found to impart chemotherapeutic resistance to malignant cells in vitro and therefore provides a possible site of therapeutic intervention.

Mice that are deficient in activating caspases downstream of MOMP sometimes display forebrain outgrowth (Miura, 2012). This has often been taken as evidence that loss of caspase activation post-MOMP results in neuronal survival during development. However, a recent study has demonstrated that, during brain development, apoptosis serves to cull cells that produce the morphogen FGF. In the absence of caspase activity, these cells survive, at least temporarily, and continuously produce FGF leading to forebrain outgrowth (Nonomura et al., 2013). Whether this represents an effect of cell survival or the outcome of delayed cell death (through CICD) remains unclear.

Does it matter how a cell dies?

We would answer a resounding ‘yes’ to this question for many reasons. For reasons of brevity, we will focus our discussion upon how the type of cell death impacts upon inflammation.

Various molecules in our cells are pro-inflammatory if they are released from cells. Collectively referred to as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) or alarmins, they serve to activate neighbouring macrophages and dendritic cells through TLR signalling and other mechanisms (Kono and Rock, 2008). Importantly, DAMP release and recognition might help alert the immune system to a cell-death-inducing pathogen, but if triggered inappropriately it can also have deleterious effects, including autoimmunity. Importantly, both the extent and type of cell death represent major means of regulating DAMP release. Apoptosis is generally considered non- or even anti-inflammatory, and minimises DAMP release by various mechanisms, although this is not always the case (Green et al., 2009). Firstly, as a cell undergoes apoptosis, components of the dying cell are packaged into plasma-membrane-bound vesicles called apoptotic bodies, thereby minimising DAMP release. In an apoptotic cell, caspase-dependent processes also generate ‘find-me’ signals to attract phagocytic cells and ‘eat-me’ signals to facilitate recognition and engulfment of the apoptotic cell by phagocytes (Ravichandran, 2011). Consequently, apoptotic cells are efficiently cleared in vivo. In the absence of being phagocytosed, apoptotic cells undergo secondary necrosis and lyse; however, even in this situation they might fail to stimulate an inflammatory response. This has led to the proposal that rather than being required for cell death, caspases serve to inactivate DAMPs (Martin et al., 2012). Various data support this idea, in that caspases – either by direct cleavage or indirectly – have been shown to inactivate various DAMPs, including HMGB1 and IL-33 (Kazama et al., 2008; Lüthi et al., 2009). However, contrasting with this viewpoint, recent data has shown that apoptotic cells can indeed be inflammatory if they are not phagocytosed in a timely manner (Juncadella et al., 2013). Other studies have found that during apoptosis, exposure of calreticulin or autophagy-dependent release of ATP leads to an immunogenic response to apoptotic cells (Michaud et al., 2011; Obeid et al., 2007).

In contrast, necrotic cells are generally pro-inflammatory. As discussed above, pyroptosis is a pro-inflammatory form of cell death and necroptosis might be as well. In both cases, cell death coincides with cell swelling and plasma membrane rupture. The predicted effect of CICD is less clear; mice deficient in Apaf1 (and therefore unable to activate mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis) that survive to adulthood do not display overt signs of inflammatory disease, which is at odds with the anti-inflammatory action of caspases (Honarpour et al., 2000). Possibly, the lack of such a phenotype is due to anti-inflammatory compensatory mechanisms that are elicited during embryonic development, such as Apaf1-independent caspase activation and/or phagocytosis of cells undergoing CICD prior to lysis.

Conclusion and future directions

We have highlighted four non-apoptotic mechanisms of programmed cell death, discussed their mechanisms and possible roles in vivo. Clearly, one of the biggest challenges is to develop definitive approaches to detect non-apoptotic cell death in vivo. Moreover, the study of processes such as RIPK3-dependent necroptosis is hampered by additional non-cytotoxic effects of key factors involved in the process. Further understanding of the basic mechanisms of execution should allow differing effects to be dissected. Non-apoptotic forms of programmed cell death might be major contributors to physiological cell death in both apoptosis-proficient and -deficient settings. As such, beyond being solely of academic interest, understanding how cells kill themselves in a caspase-independent manner might allow us to therapeutically manipulate it in various processes including cancer and autoimmune disease.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

S.T. is supported by the grants from the Royal Society, European Union and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Counci, and is a Royal Society University Research Fellow. G.I. is the recipient of an EMBO long-term fellowship. D.G. is supported by ALSAC (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital), and grants from the National Institutes of Health. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Arnoult D., Gaume B., Karbowski M., Sharpe J. C., Cecconi F., Youle R. J. (2003). Mitochondrial release of AIF and EndoG requires caspase activation downstream of Bax/Bak-mediated permeabilization. EMBO J. 22, 4385–4399 10.1093/emboj/cdg423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahi N., Zhang J., Llovera M., Ballester M., Comella J. X., Sanchis D. (2006). Switch from caspase-dependent to caspase-independent death during heart development: essential role of endonuclease G in ischemia-induced DNA processing of differentiated cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22943–22952 10.1074/jbc.M601025200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basit F., Cristofanon S., Fulda S. (2013). Obatoclax (GX15-070) triggers necroptosis by promoting the assembly of the necrosome on autophagosomal membranes. Cell Death Differ. 20, 1161–1173 10.1038/cdd.2013.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T., Cookson B. T. (2007). Macrophage activation redirects yersinia-infected host cell death from apoptosis to caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis. PLoS Pathog. 3, e161 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T., Fink S. L., Cookson B. T. (2009). Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 99–109 10.1038/nrmicro2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D. L., Baehrecke E. H. (2008). Autophagy functions in programmed cell death. Autophagy 4, 359–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betin V. M., Lane J. D. (2009). Caspase cleavage of Atg4D stimulates GABARAP-L1 processing and triggers mitochondrial targeting and apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2554–2566 10.1242/jcs.046250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biton S., Ashkenazi A. (2011). NEMO and RIP1 control cell fate in response to extensive DNA damage via TNF-α feedforward signaling. Cell 145, 92–103 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet M. C., Preukschat D., Welz P. S., van Loo G., Ermolaeva M. A., Bloch W., Haase I., Pasparakis M. (2011). The adaptor protein FADD protects epidermal keratinocytes from necroptosis in vivo and prevents skin inflammation. Immunity 35, 572–582 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray K., Mathew R., Lau A., Kamphorst J. J., Fan J., Chen J., Chen H. Y., Ghavami A., Stein M., DiPaola R. S. et al. (2012). Autophagy suppresses RIP kinase-dependent necrosis enabling survival to mTOR inhibition. PLoS ONE 7, e41831 10.1371/journal.pone.0041831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Jitkaew S., Zhao J., Chiang H. C., Choksi S., Liu J., Ward Y., Wu L. G., Liu Z. G. (2014). Plasma membrane translocation of trimerized MLKL protein is required for TNF-induced necroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 55–65 10.1038/ncb2883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi F., Alvarez-Bolado G., Meyer B. I., Roth K. A., Gruss P. (1998). Apaf1 (CED-4 homolog) regulates programmed cell death in mammalian development. Cell 94, 727–737 10.1016/S0092--8674(00)81732--8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch'en I. L., Beisner D. R., Degterev A., Lynch C., Yuan J., Hoffmann A., Hedrick S. M. (2008). Antigen-mediated T cell expansion regulated by parallel pathways of death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 17463–17468 10.1073/pnas.0808043105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chautan M., Chazal G., Cecconi F., Gruss P., Golstein P. (1999). Interdigital cell death can occur through a necrotic and caspase-independent pathway. Curr. Biol. 9, 967–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Zhou Z., Li L., Zhong C. Q., Zheng X., Wu X., Zhang Y., Ma H., Huang D., Li W. et al. (2013). Diverse sequence determinants control human and mouse receptor interacting protein 3 (RIP3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) interaction in necroptotic signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 16247–16261 10.1074/jbc.M112.435545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Li W., Ren J., Huang D., He W. T., Song Y., Yang C., Li W., Zheng X., Chen P. et al. (2014). Translocation of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein to plasma membrane leads to necrotic cell death. Cell Res. 24, 105–121 10.1038/cr.2013.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. S., Challa S., Moquin D., Genga R., Ray T. D., Guildford M., Chan F. K. (2009). Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137, 1112–1123 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi A. M., Ryter S. W., Levine B. (2013). Autophagy in human health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1845–1846 10.1056/NEJMra1205406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechomska I. A., Goemans G. C., Skepper J. N., Tolkovsky A. M. (2009). Bcl-2 complexed with Beclin-1 maintains full anti-apoptotic function. Oncogene 28, 2128–2141 10.1038/onc.2009.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colell A., Ricci J. E., Tait S., Milasta S., Maurer U., Bouchier-Hayes L., Fitzgerald P., Guio-Carrion A., Waterhouse N. J., Li C. W. et al. (2007). GAPDH and autophagy preserve survival after apoptotic cytochrome c release in the absence of caspase activation. Cell 129, 983–997 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crighton D., Wilkinson S., O'Prey J., Syed N., Smith P., Harrison P. R., Gasco M., Garrone O., Crook T., Ryan K. M. (2006). DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell 126, 121–134 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das G., Shravage B. V., Baehrecke E. H. (2012). Regulation and function of autophagy during cell survival and cell death. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a008813 10.1101/cshperspect.a008813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degterev A., Huang Z., Boyce M., Li Y., Jagtap P., Mizushima N., Cuny G. D., Mitchison T. J., Moskowitz M. A., Yuan J. (2005). Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 112–119 10.1038/nchembio711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton D., Shravage B., Simin R., Mills K., Berry D. L., Baehrecke E. H., Kumar S. (2009). Autophagy, not apoptosis, is essential for midgut cell death in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 19, 1741–1746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh M., Johnson E. M., Jr (1998). Evidence of a novel event during neuronal death: development of competence-to-die in response to cytoplasmic cytochrome c. Neuron 21, 695–705 10.1016/S0896--6273(00)80587--5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon C. P., Oberst A., Weinlich R., Janke L. J., Kang T. B., Ben-Moshe T., Mak T. W., Wallach D., Green D. R. (2012). Survival function of the FADD-CASPASE-8-cFLIP(L) complex. Cell Reports 1, 401–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgendy M., Sheridan C., Brumatti G., Martin S. J. (2011). Oncogenic Ras-induced expression of Noxa and Beclin-1 promotes autophagic cell death and limits clonogenic survival. Mol. Cell 42, 23–35 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Yang Y., Mei Y., Ma L., Zhu D. E., Hoti N., Castanares M., Wu M. (2007). Cleavage of RIP3 inactivates its caspase-independent apoptosis pathway by removal of kinase domain. Cell. Signal. 19, 2056–2067 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistova M., Geserick P., Kellert B., Dimitrova D. P., Langlais C., Hupe M., Cain K., MacFarlane M., Häcker G., Leverkus M. (2011). cIAPs block Ripoptosome formation, a RIP1/caspase-8 containing intracellular cell death complex differentially regulated by cFLIP isoforms. Mol. Cell 43, 449–463 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro W., Pulicati A., Cencioni M., Cozzolino M., Navoni F., di Martino S., Nardacci R., Carri M., Cecconi F. (2008). Apoptosome-deficient cells lose cytochrome c through proteasomal degradation but survive by autophagy-dependent glycolysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3576–3588 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festjens N., Kalai M., Smet J., Meeus A., Van Coster R., Saelens X., Vandenabeele P. (2006). Butylated hydroxyanisole is more than a reactive oxygen species scavenger. Cell Death Differ. 13, 166–169 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink S. L., Cookson B. T. (2006). Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 1812–1825 10.1111/j.1462--5822.2006.00751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink S. L., Bergsbaken T., Cookson B. T. (2008). Anthrax lethal toxin and Salmonella elicit the common cell death pathway of caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis via distinct mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 4312–4317 10.1073/pnas.0707370105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L., Vanden Berghe T., Vanlangenakker N., Buettner S., Eisenberg T., Vandenabeele P., Madeo F., Kroemer G. (2011). Programmed necrosis from molecules to health and disease. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 289, 1–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L., Vitale I., Abrams J. M., Alnemri E. S., Baehrecke E. H., Blagosklonny M. V., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L., El-Deiry W. S., Fulda S. et al. (2012). Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ. 19, 107–120 10.1038/cdd.2011.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geserick P., Hupe M., Moulin M., Wong W. W., Feoktistova M., Kellert B., Gollnick H., Silke J., Leverkus M. (2009). Cellular IAPs inhibit a cryptic CD95-induced cell death by limiting RIP1 kinase recruitment. J. Cell Biol. 187, 1037–1054 10.1083/jcb.200904158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goemans C. G., Boya P., Skirrow C. J., Tolkovsky A. M. (2008). Intra-mitochondrial degradation of Tim23 curtails the survival of cells rescued from apoptosis by caspase inhibitors. Cell Death Differ. 15, 545–554 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. R. (2011). Means to an End: Apoptosis and Other Cell Death Mechanisms Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- Green D. R., Ferguson T., Zitvogel L., Kroemer G. (2009). Immunogenic and tolerogenic cell death. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 353–363 10.1038/nri2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. R., Oberst A., Dillon C. P., Weinlich R., Salvesen G. S. (2011). RIPK-dependent necrosis and its regulation by caspases: a mystery in five acts. Mol. Cell 44, 9–16 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Wang L., Miao L., Wang T., Du F., Zhao L., Wang X. (2009). Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell 137, 1100–1111 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Liang Y., Shao F., Wang X. (2011). Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20054–20059 10.1073/pnas.1116302108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henao-Mejia J., Elinav E., Strowig T., Flavell R. A. (2012). Inflammasomes: far beyond inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 13, 321–324 10.1038/ni.2257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh D., Monack D. M., Smith M. R., Ghori N., Falkow S., Zychlinsky A. (1999). The Salmonella invasin SipB induces macrophage apoptosis by binding to caspase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2396–2401 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler N., Zaru R., Micheau O., Thome M., Attinger A., Valitutti S., Bodmer J. L., Schneider P., Seed B., Tschopp J. (2000). Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat. Immunol. 1, 489–495 10.1038/82732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honarpour N., Du C., Richardson J. A., Hammer R. E., Wang X., Herz J. (2000). Adult Apaf-1-deficient mice exhibit male infertility. Dev. Biol. 218, 248–258 10.1006/dbio.1999.9585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Baehrecke E. H., Thummel C. S. (1997). Steroid regulated programmed cell death during Drosophila metamorphosis. Development 124, 4673–4683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. M., Datta P., Srinivasula S. M., Ji W., Gupta S., Zhang Z., Davies E., Hajnóczky G., Saunders T. L., Van Keuren M. L. et al. (2003). Loss of Omi mitochondrial protease activity causes the neuromuscular disorder of mnd2 mutant mice. Nature 425, 721–727 10.1038/nature02052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juncadella I. J., Kadl A., Sharma A. K., Shim Y. M., Hochreiter-Hufford A., Borish L., Ravichandran K. S. (2013). Apoptotic cell clearance by bronchial epithelial cells critically influences airway inflammation. Nature 493, 547–551 10.1038/nature11714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser W. J., Upton J. W., Long A. B., Livingston-Rosanoff D., Daley-Bauer L. P., Hakem R., Caspary T., Mocarski E. S. (2011). RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature 471, 368–372 10.1038/nature09857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T. B., Yang S. H., Toth B., Kovalenko A., Wallach D. (2013). Caspase-8 blocks kinase RIPK3-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity 38, 27–40 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N., Warming S., Lamkanfi M., Vande Walle L., Louie S., Dong J., Newton K., Qu Y., Liu J., Heldens S. et al. (2011). Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479, 117–121 10.1038/nature10558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazama H., Ricci J. E., Herndon J. M., Hoppe G., Green D. R., Ferguson T. A. (2008). Induction of immunological tolerance by apoptotic cells requires caspase-dependent oxidation of high-mobility group box-1 protein. Immunity 29, 21–32 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono H., Rock K. L. (2008). How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 279–289 10.1038/nri2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosta A., Roisin-Bouffay C., Luciani M. F., Otto G. P., Kessin R. H., Golstein P. (2004). Autophagy gene disruption reveals a non-vacuolar cell death pathway in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48404–48409 10.1074/jbc.M408924200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G., Levine B. (2008). Autophagic cell death: the story of a misnomer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 1004–1010 10.1038/nrm2529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamy L., Ngo V. N., Emre N. C., Shaffer A. L., 3rd, Yang Y., Tian E., Nair V., Kruhlak M. J., Zingone A., Landgren O. et al. (2013). Control of autophagic cell death by caspase-10 in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell 23, 435–449 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartigue L., Kushnareva Y., Seong Y., Lin H., Faustin B., Newmeyer D. D. (2009). Caspase-independent mitochondrial cell death results from loss of respiration, not cytotoxic protein release. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4871–4884 10.1091/mbc.E09--07--0649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laster S. M., Wood J. G., Gooding L. R. (1988). Tumor necrosis factor can induce both apoptic and necrotic forms of cell lysis. J. Immunol. 141, 2629–2634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., McQuade T., Siemer A. B., Napetschnig J., Moriwaki K., Hsiao Y. S., Damko E., Moquin D., Walz T., McDermott A. et al. (2012). The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell 150, 339–350 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. H., Kleeman L. K., Jiang H. H., Gordon G., Goldman J. E., Berry G., Herman B., Levine B. (1998). Protection against fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis by beclin, a novel Bcl-2-interacting protein. J. Virol. 72, 8586–8596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkermann A., Hackl M. J., Kunzendorf U., Walczak H., Krautwald S., Jevnikar A. M. (2013). Necroptosis in immunity and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Transplant. 13, 2797–2804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Shoji-Kawata S., Sumpter R. M., Jr, Wei Y., Ginet V., Zhang L., Posner B., Tran K. A., Green D. R., Xavier R. J. et al. (2013). Autosis is a Na+,K+-ATPase-regulated form of cell death triggered by autophagy-inducing peptides, starvation, and hypoxia-ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20364–20371 10.1073/pnas.1319661110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S., Rubinsztein D. C. (2010). Apoptosis blocks Beclin 1-dependent autophagosome synthesis: an effect rescued by Bcl-xL. Cell Death Differ. 17, 268–277 10.1038/cdd.2009.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S., Garcia-Arencibia M., Zhao R., Puri C., Toh P. P., Sadiq O., Rubinsztein D. C. (2012). Bim inhibits autophagy by recruiting Beclin 1 to microtubules. Mol. Cell 47, 359–370 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthi A. U., Cullen S. P., McNeela E. A., Duriez P. J., Afonina I. S., Sheridan C., Brumatti G., Taylor R. C., Kersse K., Vandenabeele P. et al. (2009). Suppression of interleukin-33 bioactivity through proteolysis by apoptotic caspases. Immunity 31, 84–98 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri M. C., Le Toumelin G., Criollo A., Rain J. C., Gautier F., Juin P., Tasdemir E., Pierron G., Troulinaki K., Tavernarakis N. et al. (2007). Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-X(L) and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J. 26, 2527–2539 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. J., Henry C. M., Cullen S. P. (2012). A perspective on mammalian caspases as positive and negative regulators of inflammation. Mol. Cell 46, 387–397 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou I., Desagher S., Eskes R., Antonsson B., André E., Fakan S., Martinou J. C. (1999). The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria during apoptosis of NGF-deprived sympathetic neurons is a reversible event. J. Cell Biol. 144, 883–889 10.1083/jcb.144.5.883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura H., Shimizu Y., Ohsawa Y., Kawahara A., Uchiyama Y., Nagata S. (2000). Necrotic death pathway in Fas receptor signaling. J. Cell Biol. 151, 1247–1256 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwain D. R., Berger T., Mak T. W. (2013). Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a008656 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao E. A., Leaf I. A., Treuting P. M., Mao D. P., Dors M., Sarkar A., Warren S. E., Wewers M. D., Aderem A. (2010). Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 11, 1136–1142 10.1038/ni.1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud M., Martins I., Sukkurwala A. Q., Adjemian S., Ma Y., Pellegatti P., Shen S., Kepp O., Scoazec M., Mignot G. et al. (2011). Autophagy-dependent anticancer immune responses induced by chemotherapeutic agents in mice. Science 334, 1573–1577 10.1126/science.1208347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura M. (2012). Apoptotic and nonapoptotic caspase functions in animal development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a008664 10.1101/cshperspect.a008664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. (2011). Autophagy in protein and organelle turnover. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 76, 397–402 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.011023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriwaki K., Chan F. K. (2013). RIP3: a molecular switch for necrosis and inflammation. Genes Dev. 27, 1640–1649 10.1101/gad.223321.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moujalled D. M., Cook W. D., Okamoto T., Murphy J., Lawlor K. E., Vince J. E., Vaux D. L. (2013). TNF can activate RIPK3 and cause programmed necrosis in the absence of RIPK1. Cell Death Dis. 4, e465 10.1038/cddis.2012.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Pinedo C., Guio-Carrion A., Goldstein J. C., Fitzgerald P., Newmeyer D. D., Green D. R. (2006). Different mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins are released during apoptosis in a manner that is coordinately initiated but can vary in duration. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 11573–11578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. M., Czabotar P. E., Hildebrand J. M., Lucet I. S., Zhang J. G., Alvarez-Diaz S., Lewis R., Lalaoui N., Metcalf D., Webb A. I. et al. (2013). The pseudokinase MLKL mediates necroptosis via a molecular switch mechanism. Immunity 39, 443–453 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendra D., Tanaka A., Suen D. F., Youle R. J. (2008). Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 183, 795–803 10.1083/jcb.200809125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K., Dugger D. L., Wickliffe K. E., Kapoor N., Cristina de-Almagro M., Vucic D., Komuves L., Ferrando R. E., French D. M., Webster J. et al. (2014). Activity of protein kinase RIPK3 Determines whether cells die by necroptosis or apoptosis. Science 343, 1357–1360 10.1126/science.1249361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura K., Yamaguchi Y., Hamachi M., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Nakazato K., Mochizuki A., Sakaue-Sawano A., Miyawaki A., Yoshida H. et al. (2013). Local apoptosis modulates early mammalian brain development through the elimination of morphogen-producing cells. Dev. Cell 27, 621–634 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell M. A., Perez-Jimenez E., Oberst A., Ng A., Massoumi R., Xavier R., Green D. R., Ting A. T. (2011). Caspase 8 inhibits programmed necrosis by processing CYLD. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1437–1442 10.1038/ncb2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid M., Tesniere A., Ghiringhelli F., Fimia G. M., Apetoh L., Perfettini J. L., Castedo M., Mignot G., Panaretakis T., Casares N. et al. (2007). Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat. Med. 13, 54–61 10.1038/nm1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberst A., Green D. R. (2011). It cuts both ways: reconciling the dual roles of caspase 8 in cell death and survival. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 757–763 10.1038/nrm3214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberst A., Dillon C. P., Weinlich R., McCormick L. L., Fitzgerald P., Pop C., Hakem R., Salvesen G. S., Green D. R. (2011). Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature 471, 363–367 10.1038/nature09852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofengeim D., Yuan J. (2013). Regulation of RIP1 kinase signalling at the crossroads of inflammation and cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 727–736 10.1038/nrm3683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto G. P., Wu M. Y., Kazgan N., Anderson O. R., Kessin R. H. (2003). Macroautophagy is required for multicellular development of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 17636–17645 10.1074/jbc.M212467200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayotova-Dimitrova D., Feoktistova M., Ploesser M., Kellert B., Hupe M., Horn S., Makarov R., Jensen F., Porubsky S., Schmieder A. et al. (2013). cFLIP regulates skin homeostasis and protects against TNF-induced keratinocyte apoptosis. Cell Reports 5, 397–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish A. B., Freel C. D., Kornbluth S. (2013). Cellular mechanisms controlling caspase activation and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a008672 10.1101/cshperspect.a008672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S., Tassa A., Qu X., Garuti R., Liang X. H., Mizushima N., Packer M., Schneider M. D., Levine B. (2005). Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 122, 927–939 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyo J. O., Jang M. H., Kwon Y. K., Lee H. J., Jun J. I., Woo H. N., Cho D. H., Choi B., Lee H., Kim J. H. et al. (2005). Essential roles of Atg5 and FADD in autophagic cell death: dissection of autophagic cell death into vacuole formation and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20722–20729 10.1074/jbc.M413934200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radoshevich L., Murrow L., Chen N., Fernandez E., Roy S., Fung C., Debnath J. (2010). ATG12 conjugation to ATG3 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and cell death. Cell 142, 590–600 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran K. S. (2011). Beginnings of a good apoptotic meal: the find-me and eat-me signaling pathways. Immunity 35, 445–455 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray C. A., Black R. A., Kronheim S. R., Greenstreet T. A., Sleath P. R., Salvesen G. S., Pickup D. J. (1992). Viral inhibition of inflammation: cowpox virus encodes an inhibitor of the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Cell 69, 597–604 10.1016/0092--8674(92)90223--Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rébé C., Cathelin S., Launay S., Filomenko R., Prévotat L., L'Ollivier C., Gyan E., Micheau O., Grant S., Dubart-Kupperschmitt A. et al. (2007). Caspase-8 prevents sustained activation of NF-kappaB in monocytes undergoing macrophagic differentiation. Blood 109, 1442–1450 10.1182/blood--2006--03--011585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt C. A., Fridman J. S., Yang M., Baranov E., Hoffman R. M., Lowe S. W. (2002). Dissecting p53 tumor suppressor functions in vivo. Cancer Cell 1, 289–298 10.1016/S1535--6108(02)00047--8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Osthoff K., Bakker A. C., Vanhaesebroeck B., Beyaert R., Jacob W. A., Fiers W. (1992). Cytotoxic activity of tumor necrosis factor is mediated by early damage of mitochondrial functions. Evidence for the involvement of mitochondrial radical generation. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 5317–5323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S., Kanaseki T., Mizushima N., Mizuta T., Arakawa-Kobayashi S., Thompson C. B., Tsujimoto Y. (2004). Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1221–1228 10.1038/ncb1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. L., Benfield C. T., Maluquer de Motes C., Mazzon M., Ember S. W., Ferguson B. J., Sumner R. P. (2013). Vaccinia virus immune evasion: mechanisms, virulence and immunogenicity. J. Gen. Virol. 94, 2367–2392 10.1099/vir.0.055921--0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Wang H., Wang Z., He S., Chen S., Liao D., Wang L., Yan J., Liu W., Lei X. et al. (2012). Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148, 213–227 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait S. W., Green D. R. (2008). Caspase-independent cell death: leaving the set without the final cut. Oncogene 27, 6452–6461 10.1038/onc.2008.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait S. W., Parsons M. J., Llambi F., Bouchier-Hayes L., Connell S., Muñoz-Pinedo C., Green D. R. (2010). Resistance to caspase-independent cell death requires persistence of intact mitochondria. Dev. Cell 18, 802–813 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait S. W., Oberst A., Quarato G., Milasta S., Haller M., Wang R., Karvela M., Ichim G., Yatim N., Albert M. L. et al. (2013). Widespread mitochondrial depletion via mitophagy does not compromise necroptosis. Cell Reports 5, 878–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. C., Cullen S. P., Martin S. J. (2008). Apoptosis: controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 231–241 10.1038/nrm2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenev T., Bianchi K., Darding M., Broemer M., Langlais C., Wallberg F., Zachariou A., Lopez J., MacFarlane M., Cain K. et al. (2011). The Ripoptosome, a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Mol. Cell 43, 432–448 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thome M., Schneider P., Hofmann K., Fickenscher H., Meinl E., Neipel F., Mattmann C., Burns K., Bodmer J. L., Schröter M. et al. (1997). Viral FLICE-inhibitory proteins (FLIPs) prevent apoptosis induced by death receptors. Nature 386, 517–521 10.1038/386517a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton J. W., Kaiser W. J., Mocarski E. S. (2010). Virus inhibition of RIP3-dependent necrosis. Cell Host Microbe 7, 302–313 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton J. W., Kaiser W. J., Mocarski E. S. (2012). DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe 11, 290–297 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn A. E., Deshmukh M. (2008). Glucose metabolism inhibits apoptosis in neurons and cancer cells by redox inactivation of cytochrome c. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1477–1483 10.1038/ncb1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince J. E., Wong W. W., Gentle I., Lawlor K. E., Allam R., O'Reilly L., Mason K., Gross O., Ma S., Guarda G. et al. (2012). Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins limit RIP3 kinase-dependent interleukin-1 activation. Immunity 36, 215–227 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Du F., Wang X. (2008). TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell 133, 693–703 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Jiang H., Chen S., Du F., Wang X. (2012). The mitochondrial phosphatase PGAM5 functions at the convergence point of multiple necrotic death pathways. Cell 148, 228–243 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Lu Q., Cheng S., Wang X., Zhang H. (2013). Autophagy activity contributes to programmed cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Autophagy 9, 1975–1982 10.4161/auto.26152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M. C., Zong W. X., Cheng E. H., Lindsten T., Panoutsakopoulou V., Ross A. J., Roth K. A., MacGregor G. R., Thompson C. B., Korsmeyer S. J. (2001). Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science 292, 727–730 10.1126/science.1059108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinlich R., Oberst A., Dillon C. P., Janke L. J., Milasta S., Lukens J. R., Rodriguez D. A., Gurung P., Savage C., Kanneganti T. D. et al. (2013). Protective roles for caspase-8 and cFLIP in adult homeostasis. Cell Reports 5, 340–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welz P. S., Wullaert A., Vlantis K., Kondylis V., Fernández-Majada V., Ermolaeva M., Kirsch P., Sterner-Kock A., van Loo G., Pasparakis M. (2011). FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature 477, 330–334 10.1038/nature10273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright K. M., Smith M. I., Farrag L., Deshmukh M. (2007). Chromatin modification of Apaf-1 restricts the apoptotic pathway in mature neurons. J. Cell Biol. 179, 825–832 10.1083/jcb.200708086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Huang Z., Ren J., Zhang Z., He P., Li Y., Ma J., Chen W., Zhang Y., Zhou X. et al. (2013). Mlkl knockout mice demonstrate the indispensable role of Mlkl in necroptosis. Cell Res. 23, 994–1006 10.1038/cr.2013.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Kong Y. Y., Yoshida R., Elia A. J., Hakem A., Hakem R., Penninger J. M., Mak T. W. (1998). Apaf1 is required for mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis and brain development. Cell 94, 739–750 10.1016/S0092--8674(00)81733--X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi S., Perozzo R., Schmid I., Ziemiecki A., Schaffner T., Scapozza L., Brunner T., Simon H. U. (2006). Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1124–1132 10.1038/ncb1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Alva A., Su H., Dutt P., Freundt E., Welsh S., Baehrecke E. H., Lenardo M. J. (2004). Regulation of an ATG7-beclin 1 program of autophagic cell death by caspase-8. Science 304, 1500–1502 10.1126/science.1096645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Wan F., Dutta S., Welsh S., Liu Z., Freundt E., Baehrecke E. H., Lenardo M. (2006). Autophagic programmed cell death by selective catalase degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 4952–4957 10.1073/pnas.0511288103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. W., Shao J., Lin J., Zhang N., Lu B. J., Lin S. C., Dong M. Q., Han J. (2009). RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science 325, 332–336 10.1126/science.1172308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Jitkaew S., Cai Z., Choksi S., Li Q., Luo J., Liu Z. G. (2012). Mixed lineage kinase domain-like is a key receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of TNF-induced necrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 5322–5327 10.1073/pnas.1200012109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]