Abstract

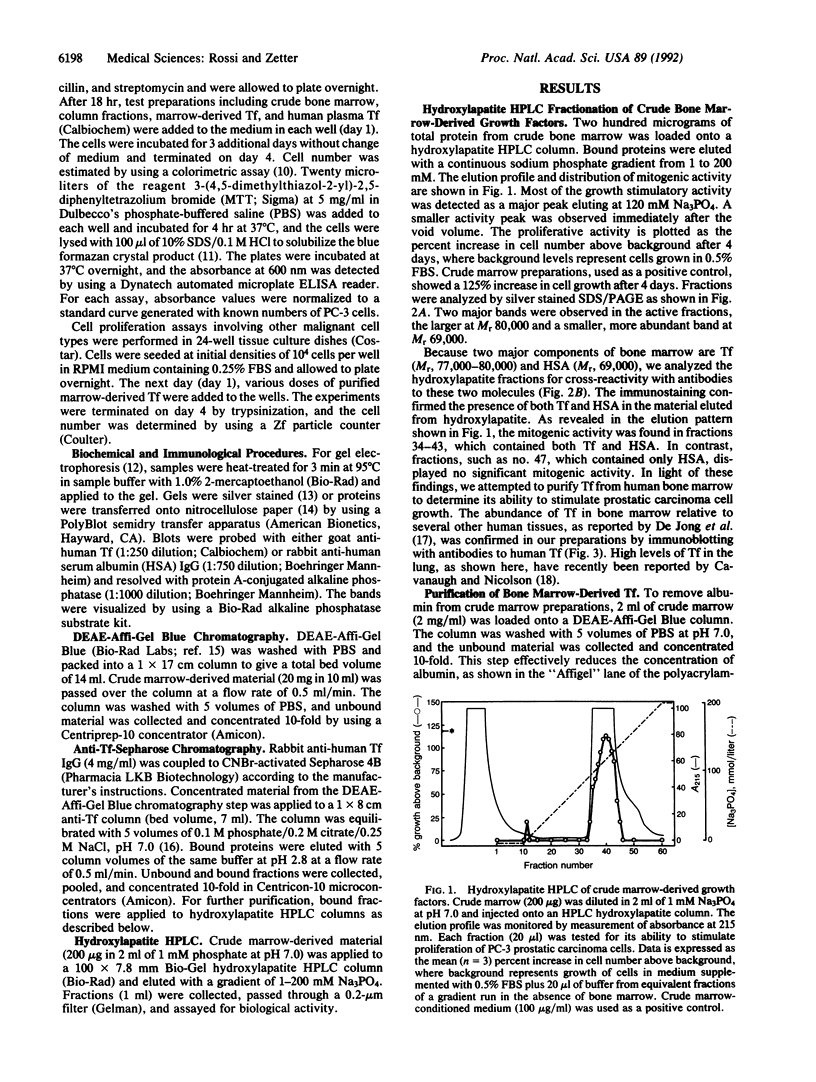

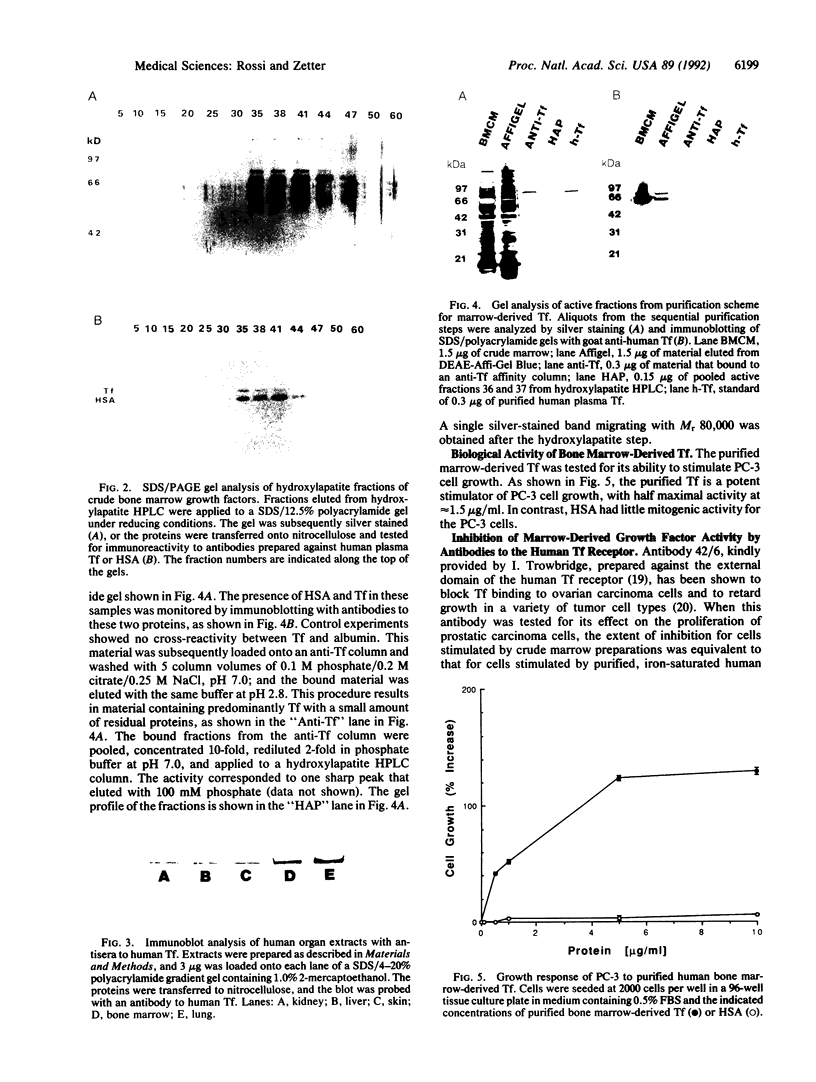

Aggressive prostatic carcinomas most frequently metastasize to the skeletal system. We have previously shown that cultured human prostatic carcinoma cells are highly responsive to growth factors found in human bone marrow. To identify the factor(s) responsible for the increased prostatic carcinoma cell proliferation, we fractionated crude bone marrow preparations by using hydroxylapatite HPLC. The major activity peak contained two high molecular weight bands (M(r) = 80,000 and 69,000) that cross-reacted with antibodies to human transferrin and serum albumin, respectively. Bone marrow transferrin, purified to apparent homogeneity by using DEAE-Affi-Gel Blue chromatography, anti-transferrin affinity chromatography, and hydroxylapatite HPLC, markedly stimulated prostatic carcinoma cell proliferation, whereas human serum albumin showed no significant growth factor activity. Marrow preparations, depleted of transferrin by passage over an anti-transferrin affinity column, lost greater than 90% of their proliferative activity. In contrast to the response observed with the prostatic carcinoma cell lines, a variety of human malignant cell lines, derived from other primary sites and metastatic to sites other than bone marrow, showed a reduced response to purified marrow-derived transferrin. These results suggest that rapid growth of human prostatic carcinoma metastases in spinal bone may result from a combination of conditions that include (i) drainage of prostatic carcinoma cells into the paravertebral circulation, (ii) high concentrations of available transferrin in bone marrow, and (iii) increased sensitivity of prostatic carcinoma cells to the mitogenic activity of transferrin.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barnes D., Sato G. Serum-free cell culture: a unifying approach. Cell. 1980 Dec;22(3):649–655. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra J. K., Fitzgerald D. J., Chaudhary V. K., Pastan I. Single-chain immunotoxins directed at the human transferrin receptor containing Pseudomonas exotoxin A or diphtheria toxin: anti-TFR(Fv)-PE40 and DT388-anti-TFR(Fv). Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Apr;11(4):2200–2205. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson O. V. THE FUNCTION OF THE VERTEBRAL VEINS AND THEIR ROLE IN THE SPREAD OF METASTASES. Ann Surg. 1940 Jul;112(1):138–149. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194007000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrettoni B. A., Carter J. R. Mechanisms of cancer metastasis to bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986 Feb;68(2):308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael J., DeGraff W. G., Gazdar A. F., Minna J. D., Mitchell J. B. Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res. 1987 Feb 15;47(4):936–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter H. B., Coffey D. S. The prostate: an increasing medical problem. Prostate. 1990;16(1):39–48. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990160105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh P. G., Nicolson G. L. Purification and some properties of a lung-derived growth factor that differentially stimulates the growth of tumor cells metastatic to the lung. Cancer Res. 1989 Jul 15;49(14):3928–3933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chackal-Roy M., Niemeyer C., Moore M., Zetter B. R. Stimulation of human prostatic carcinoma cell growth by factors present in human bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 1989 Jul;84(1):43–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI114167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulk W. P., Hsi B. L., Stevens P. J. Transferrin and transferrin receptors in carcinoma of the breast. Lancet. 1980 Aug 23;2(8191):390–392. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatter K. C., Brown G., Trowbridge I. S., Woolston R. E., Mason D. Y. Transferrin receptors in human tissues: their distribution and possible clinical relevance. J Clin Pathol. 1983 May;36(5):539–545. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.5.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayhack J. T., Lee C., Oliver L., Schaeffer A. J., Wendel E. F. Biochemical profiles of prostatic fluid from normal and diseased prostate glands. Prostate. 1980;1(2):227–237. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990010208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi O., Noguchi S., Oyasu R. Transferrin as a growth factor for rat bladder carcinoma cells in culture. Cancer Res. 1987 Sep 1;47(17):4560–4564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebers H. A., Finch C. A. The physiology of transferrin and transferrin receptors. Physiol Rev. 1987 Apr;67(2):520–582. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.2.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imschenetzky M., Puchi M., Pimentel C., Bustos A., Gonzales M. Immunobiochemical evidence for the loss of sperm specific histones during male pronucleus formation in monospermic zygotes of sea urchins. J Cell Biochem. 1991 Sep;47(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240470102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs S. C. Spread of prostatic cancer to bone. Urology. 1983 Apr;21(4):337–344. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(83)90147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaighn M. E., Narayan K. S., Ohnuki Y., Lechner J. F., Jones L. W. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3). Invest Urol. 1979 Jul;17(1):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keer H. N., Kozlowski J. M., Tsai Y. C., Lee C., McEwan R. N., Grayhack J. T. Elevated transferrin receptor content in human prostate cancer cell lines assessed in vitro and in vivo. J Urol. 1990 Feb;143(2):381–385. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39970-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May W. S., Jr, Cuatrecasas P. Transferrin receptor: its biological significance. J Membr Biol. 1985;88(3):205–215. doi: 10.1007/BF01871086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983 Dec 16;65(1-2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riss T. L., Sirbasku D. A. Purification and identification of transferrin as a major pituitary-derived mitogen for MTW9/PL2 rat mammary tumor cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1987 Dec;23(12):841–849. doi: 10.1007/BF02620963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg E., Boring C. C., Squires T. S. Cancer statistics, 1990. CA Cancer J Clin. 1990 Jan-Feb;40(1):9–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone K. R., Mickey D. D., Wunderli H., Mickey G. H., Paulson D. F. Isolation of a human prostate carcinoma cell line (DU 145). Int J Cancer. 1978 Mar 15;21(3):274–281. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910210305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taetle R., Honeysett J. M. Effects of monoclonal anti-transferrin receptor antibodies on in vitro growth of human solid tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1987 Apr 15;47(8):2040–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taetle R. The role of transferrin receptors in hemopoietic cell growth. Exp Hematol. 1990 May;18(4):360–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Sep;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge I. S., Lopez F. Monoclonal antibody to transferrin receptor blocks transferrin binding and inhibits human tumor cell growth in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Feb;79(4):1175–1179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.4.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eijk H. G., Van Noort W. L. Isolation of rat transferrin using CNBr-activated sepharose 4B. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1976 Oct;14(10):475–478. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1976.14.1-12.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner P. A., Galbraith R. M., Arnaud P. DEAE-Affi-Gel Blue chromatography of human serum: use for purification of native transferrin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983 Oct 1;226(1):393–398. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinari K., Yuasa K., Iga F., Mimura A. A growth-promoting factor for human myeloid leukemia cells from horse serum identified as horse serum transferrin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989 Jan 17;1010(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(89)90180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetter B. R. The cellular basis of site-specific tumor metastasis. N Engl J Med. 1990 Mar 1;322(9):605–612. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003013220907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong G., van Dijk J. P., van Eijk H. G. The biology of transferrin. Clin Chim Acta. 1990 Sep;190(1-2):1–46. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(90)90278-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]