Abstract

Recurrent objective bulimic episodes (OBE) are a defining diagnostic characteristic of binge eating disorder (BED) and bulimia nervosa (BN). OBEs are characterized by experiencing loss of control (LOC) while eating an unusually large quantity of food. Despite nosological importance and complex heterogeneity across patients, measurement of LOC has been assessed dichotomously (present/absent). This study describes the development and initial validation of the Eating Loss of Control Scale (ELOCS), a self-report questionnaire that examines the complexity of the LOC construct. Participants were 168 obese treatment-seeking individuals with BED who completed the Eating Disorder Examination interview and self-report measures. Participants rated their LOC-related feelings or behaviors on continuous Likert-type scales and reported the number of LOC episodes in the past 28 days. Principal component analysis identified a single-factor, 18-item scale, which demonstrated good internal reliability (α=0.90). Frequency of LOC episodes was significantly correlated with frequency of OBEs and subjective bulimic episodes. The ELOCS demonstrated good convergent validity and was significantly correlated with greater eating pathology, greater emotion dysregulation, greater depression, and lower self-control, but not with BMI. The findings suggest that the ELOCS is a valid self-report questionnaire that may provide important clinical information regarding experiences of LOC in obese persons with BED. Future research should examine the ELOCS in other eating disorders and non-clinical samples.

Keywords: eating disorder, loss of control, measurement, scale development, validation

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Kerstin K. Blomquist, Department of Psychology, Furman University, 3300 Poinsett Highway, Greenville, SC 29613. kerstin.blomquist@furman.edu

Recurrent episodes of binge eating are a defining characteristic of both binge eating disorder (BED) and bulimia nervosa (BN) and occur among a significant subgroup of individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Psychiatric Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000, pp. 594, 787) defines a binge-eating episode as (1) “eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g., within any 2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances” and including “(2) a sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g., a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating).” The eating disorders field has defined two types of binge eating episodes: objective bulimic episodes (OBEs; defined as consuming unusually large quantities of food while experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control) and subjective bulimic episodes (SBEs; defined as experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control while consuming a normal or small amount of food). Hence, loss or lack of control (LOC) is one of two hallmark features in determining the presence of binge eating and for establishing a diagnosis of BED, BN, or anorexia nervosa binge eating/purging type (AN-BP).

Despite its clinical importance, the assessment of the LOC construct has largely been limited to the presence or absence of LOC based on assessments of OBEs and SBEs ascertained from tools such as the Eating Disorder Examination interview (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) and questionnaire, (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994), and the self-report Questionnaire for Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised (QEWP-R; Spitzer, Yanovski, Marcus, 1993). Both the EDE and EDE-Q differentiate between OBEs and SBEs, but all three measures, EDE, EDE-Q, and QEWP-R, involve only a dichotomous assessment of LOC. Alternatively, the Binge Eating Scale (BES; Gormally, Black, Daston, & Rardin, 1982) assesses severity of binge eating by asking participants to answer questions about their binge eating based on responses weighted from 0 (no-binge-eating-symptoms) to 3 (severe-binge-eating-symptoms). Although the scale includes items related to LOC, it only generates a score for binge eating, not LOC severity (Gormally et al., 1982), and it is not recommended as a diagnostic tool for BED because of its low specificity (Celio et al., 2004). Both the presence/absence of LOC approach in the EDE, EDE-Q, and QEWP-R as well as the overall binge eating severity score produced by the BES fail to capture what clinically appears to be a very rich and potentially varied experience of LOC.

Numerous studies with diverse adult and pediatric patient and epidemiologic populations support the clinical significance of LOC during eating episodes as assessed by the presence and/or frequency of OBEs and SBEs, regardless of the actual amount consumed (Latner & Clyne, 2008). For example, studies have found that LOC is associated with greater eating disorder and general psychopathology as well as poorer quality of life in epidemiological (Mond et al., 2010) and community samples (Latner, Hildebrandt, Rosewall, Chisholm, & Hayashi, 2007), and among university students (Jenkins, Conley, Rienecke Hoste, Meyer, & Blissett, 2012), diverse obese groups (Elder, Paris, Anez, & Grilo, 2008), and bariatric surgery patients (Colles, Dixon, & O’Brien, 2008). Prospective studies have reported that higher levels of postoperative LOC were related to poorer post bariatric surgery outcomes including greater eating disorder psychopathology, greater depression, and lower quality of life (White, Kalarchian, Masheb, Marcus, & Grilo, 2010). LOC during eating episodes in children and adolescents has also been linked to greater concerns about eating, weight, and shape, higher levels of depression (Goossens et al., 2007), and greater BMI, body fat mass, and psychological distress (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2008). Shomaker and colleagues (2010) found that LOC accompanying the consumption of smaller amounts of food was associated with similar levels of general and eating-specific psychopathology as LOC when eating larger amounts of food in children and adolescents. In a prospective study, Tanofsky-Kraff and colleagues (2011) found that feelings of LOC during children’s eating episodes were associated prospectively with the development of BED, greater eating disorder psychopathology, and anxiety 4-5 years later.

While the significance of LOC overeating has been supported consistently, research has raised questions regarding the utility or importance of the distinction regarding the quantity of food consumed (i.e., unusually large quantities versus not unusually large quantities) across both non-clinical (Latner et al., 2007; Mond et al., 2010) and clinical samples (Niego, Pratt, & Agras, 1997; Pratt, Niego, & Agras, 1998), and across developmental stages (Goossens, Braet, & Decaluwe, 2007; Tanofsky-Kraff, Marcus, Yanovski, & Yanovski, 2008; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2011). The majority of studies on this topic have not assessed feelings of LOC in both OBEs and SBEs, irrespective of amount of food consumed, thus hindering our ability to isolate and understand the LOC construct independent of food amount.

Recognizing this limitation, Mitchell and colleagues (2012) administered a one-item Likert scale assessing the experience of LOC from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) among a sample of patients with BN. The authors found variability in self-reported LOC and reported that greater LOC was associated with a larger amount of kilocalories consumed across different eating episodes as well as a greater likelihood of vomiting after an eating occasion. These findings highlight the clinical utility and need for a more comprehensive measure of the LOC construct. Similarly, in an ecologic momentary assessment study (Goldschmidt et al., 2012) that provided participants with handheld computers to record their mood and eating behaviors in real-time, the LOC construct was isolated and measured (rated on a one item Likert-type scale from 1- “Complete Control” to 5-“Complete LOC”) in obese adults with and without BED, and non-obese adults. The study found that greater LOC was associated with greater pre-meal negative affect and post-meal negative affect for individuals with BED only, regardless of the amount of food consumed during a meal (Goldschmidt et al., 2012). Although these two studies (Mitchell et al., 2012 & Goldschmidt et al., 2012) assessed LOC severity on a Likert-type scale and provided support for the clinical utility of a dimensional measure of LOC, the single item scale does not appear to capture the potential heterogeneity of the LOC construct.

Given that LOC is a central diagnostic and clinical feature of BED, BN, and AN, and there is no comprehensive, validated self-report measure of LOC, we created the Eating Loss of Control Scale (ELOCS). The aim of this paper is to describe the development and initial validation of this scale, which is designed to capture the varied experience of LOC among individuals with eating disorders by measuring different aspects of this construct on continuous Likert-type scales.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 168 treatment-seeking obese men and women who met full DSM-IV research diagnostic criteria for BED. The sample comprises individuals enrolled in one of two treatment studies. Individuals in the first study (n=47) were recruited from primary care clinics via physician referrals or flyers posted in primary care clinics recruiting obese persons who wanted to “stop binge eating and lose weight” for treatment at a medical school-based specialty clinic. Participants were eligible if they had a body mass index (BMI) of 30-50 (kg/m2) and reported OBEs at least one time per week. Individuals in the second study (n=121) were recruited from newspaper advertisements seeking obese men and women who eat “out of control” and “want to lose weight” for a treatment study at a medical school-based specialty clinic. Inclusion criteria for the second study were: a BMI of 30-55 (kg/m2) and a DSM-IV-TR research diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED). Exclusion criteria for both studies were: pregnancy or breastfeeding, uncontrolled hypertension, significant cardiovascular disease, coronary arterial disease, significant neurological history, regular use of purging behaviors, severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and substance dependence). Individuals who currently used antidepressants were deemed ineligible due to possible contraindication with the study medication.

Participants (N=168) who met full DSM-IV research diagnostic criteria for BED and who completed the ELOCS were included in the current study. Participants were aged 21 to 65 years (M = 48.33, SD = 10.17) and 71.43% (n=120) were women. Participants were 69.64% (n=117) Caucasian non-Hispanic, 20.23% (n=34) African-American/Black non-Hispanic, 5.95% (n=10) Hispanic, 1.19% Asian (n=2), and 2.98% (n=5) other or of mixed race. Educationally, 4.17% (n=7) reported some high school only, 15.48% (n=26) high school or GED, 30.95% (n=52) some college or associates degree, and 49.40% (n=83) college degree. Participants’ mean BMI was 38.81 kg/m2 (SD=5.70). The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee and all participants provided written informed consent.

Assessment and Measures

Assessment procedures for both studies were performed by trained doctoral-level research-clinicians as follows. BED diagnosis was based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, 1996) and confirmed with the Eating Disorder Examination interview (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). Participants’ height and weight were measured at an intake assessment using a high capacity digital scale. Participants were asked to complete the ELOCS in addition to a battery of self-report measures.

Measures

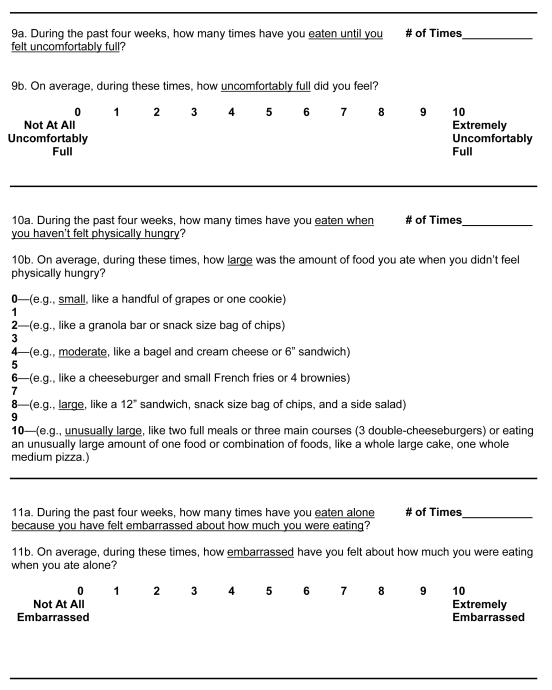

Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). The EDE, a well-established interview, assesses eating disorder psychopathology with established reliability for BED (Grilo, Masheb, Lozano-Blanco, & Barry, 2004). Except for diagnostic items, which are rated according to the appropriate DSM-IV-TR duration stipulations, the EDE focuses on the previous 28 days. The EDE assesses the frequency of different forms of overeating, including OBEs, SBEs, and objective overeating episodes (OOEs; i.e., eating unusually large quantities of food without a subjective sense of loss of control). The EDE comprises four subscales (eating concern, weight concern, shape concern, and restraint) and generates a global eating pathology score. In this sample, internal consistencies for the EDE subscales were α=0.69 for eating concern, α=0.57 for weight concern, α=0.70 for shape concern, and α=0.61 for restraint. These internal consistencies are similar to those reported previously in other BED samples (Grilo et al., 2009b). The EDE also assesses the presence or absence of specific features that are presumed to be characteristic of a binge episode, including “eating more rapidly than usual,” “eating until you felt uncomfortably full,” “eating large amounts of food when you didn’t feel physically hungry,”“eating alone because you were embarrassed by how much you were eating,” and “feeling disgusted, depressed or very guilty after overeating” (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). These dichotomous items were compared with similar items on the ELOCS, which rated the variables on a continuous scale.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item measure comprising six related subscales (i.e., nonacceptance, goals, impulse, awareness, strategies, and clarity) and an overall scale with higher scores reflecting difficulties in regulating emotions. The subscales assess: “nonacceptance of emotional responses” (e.g., “when I’m upset, I become irritated with myself for feeling that way”), “difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior” (e.g., “when I’m upset, I have difficulty getting work done”), “impulse control difficulties” (e.g., “when I’m upset, I lose control over my behaviors”), “lack of emotional awareness” (e.g., “I pay attention to how I feel”), “limited access to emotion regulation strategies” (e.g., “when I’m upset, I believe there is nothing I can do to make myself feel better”), and “lack of emotional clarity” (e.g., “I know exactly how I am feeling”; Gratz & Roemer, 2004, p. 48). This scale has good internal consistency and test-retest reliability, and research indicates that this scale and construct are significantly associated with binge eating behaviors (Whiteside, Chen, Neighbors, Hunter, Lo, & Larimer, 2007). Therefore, the DERS was used to assess for convergent validity. The internal consistency of the DERS overall score in this sample was α=0.94. The internal consistencies for the DERS subscales are α=0.88 for nonacceptance, α=0.89 for goals, α=0.88 for impulse, α=0.82 for awareness, α=0.87 for strategies, and α=0.77 for clarity.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1987) is a 21-item widely used and well-established inventory (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988) assessing symptoms of depression and negative affect. The internal consistency of the BDI in this sample was α=0.89.

The Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004) is a13-item short form measure of self-control and has been found to have both good internal and test-retest reliability. It has also been found to be significantly associated with eating disorder symptoms including the bulimia subscale of the Eating Disorder Inventory (Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). Therefore, this scale was also used to assess for convergent validity. The internal consistency of the BSCS overall score in this sample was α=0.81.

Scale Development

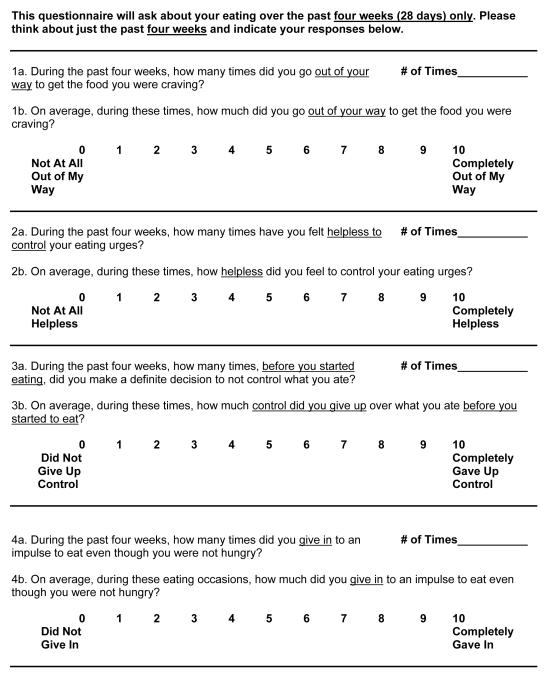

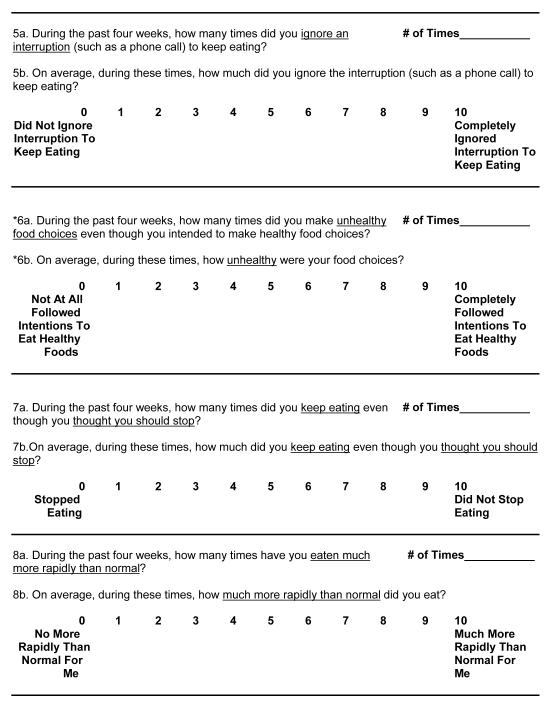

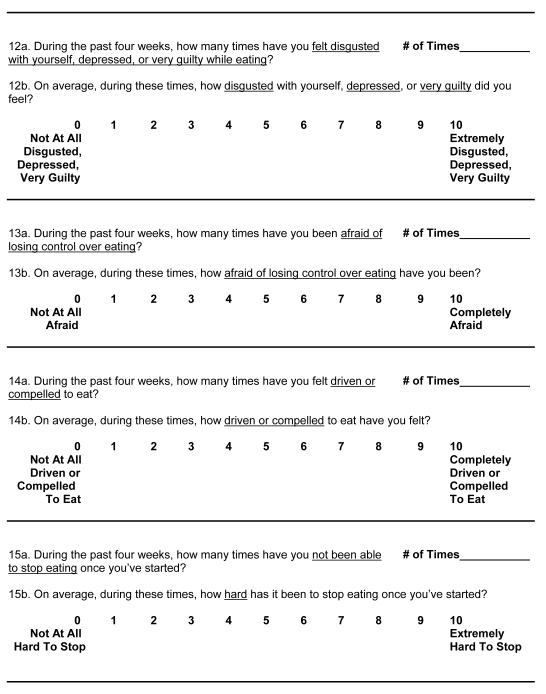

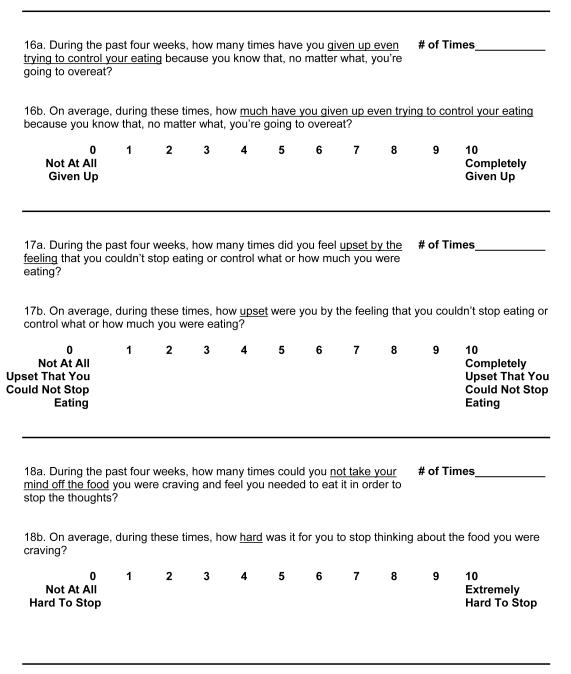

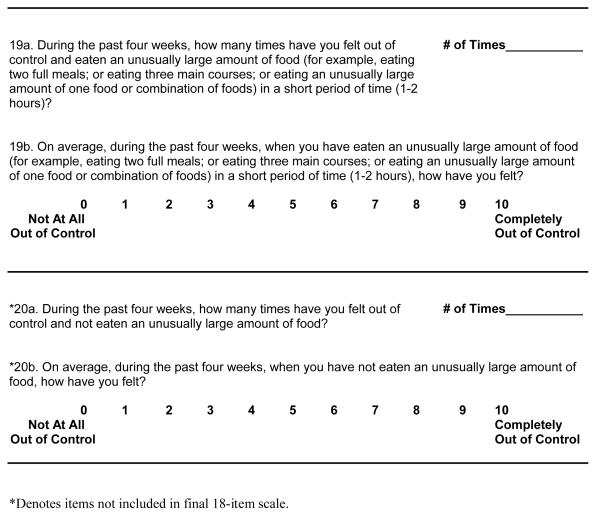

Eating Loss of Control Scale (ELOCS; see Appendix A). Items for the initial ELOCS scale were generated by taking into consideration definitions and items employed in other measures (EDE—Fairburn & Cooper, 1993; EDE-Q—Fairburn & Beglin, 1994; QEWP— Spitzer, Yanovski, & Marcus, 1993; BES—Gormally, Black, Daston, & Rardin, 1982), clinical observations of patients’ reports of LOC-related feelings and behaviors, as well as multiple discussions with researchers and clinicians familiar with eating disorders. The initial scale was composed of 20-items with two parts. The structure of the ELOCS was modeled after the EDE-Q and therefore each question begins by asking respondents, “During the past four weeks, how many times did you...?” Participants were asked to provide an estimate of the number of times in the past 28 days (four weeks) they experienced an eating episode characterized by a LOC-related feeling or behavior. After answering an open-ended frequency question, participants were prompted with the phrase, “On average, during these times, how much did you...?” and then asked to provide a rating on an 11-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 “Not at All” to 10 “Extremely” or “Completely.” These questions enabled participants to indicate the degree to which they experienced different feelings or behaviors related to a LOC. These item scores were averaged to produce a total scale score (item 6b is reverse scored); higher total scale scores reflect greater LOC. Items assessed LOC independent of the amount of food consumed except for items 10, 19, and 20 (see Appendix A). Finally, the ELOCS was designed to read at an 8th grade reading level and its readability was rated at an 8.3 Flesch-Kincaid grade level with 70.3% Flesch reading ease by Microsoft Word version 14.2.4.

Statistical Analyses

The primary purpose of this study was to create a self-report assessment that examines the construct of LOC via a series of items measured on continuous rather than dichotomous scales. Psychometric analyses were conducted on the original 20 ELOCS Likert-type items (“b” items). All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). No outliers were detected for the Likert-type scale items and no excessive skewness or kurtosis was present for any of the Likert-type scale items. Frequency items, which reflect the number of times an eating episode characterized by a loss of control was experienced in the last four weeks, that were greater than three standard deviations from the mean were identified and removed as outliers. All results were replicated when including outliers. To explore the construct validity, we first performed a principal component analysis with oblique rotation with Kaiser normalization hypothesizing that any identified factors would be correlated. This was followed by a scree plot (Floyd & Widaman, 1995) prior to reliability analyses, as recommended by Clark and Watson (1995). To explore the single factor solution, non-rotated factor loadings were inspected, and items with a factor loading less than 0.40 were removed from the scale. Item-total correlations were also examined for the single factor. Cronbach’s alphas were calculated as indicators of internal consistency. LOC frequency items were averaged to produce a mean frequency score. To assess for convergent and discriminant validity, Pearson bivariate correlations were conducted with continuous variables, and Point Biserial Pearson correlations were performed with dichotomous and continuous variables. To explore demographic differences in ELOCS variables, univariate Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) were conducted. To control for gender and ethnicity partial correlations and Analyses of Covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted.

RESULTS

Construct Validity and Principal Component Analysis

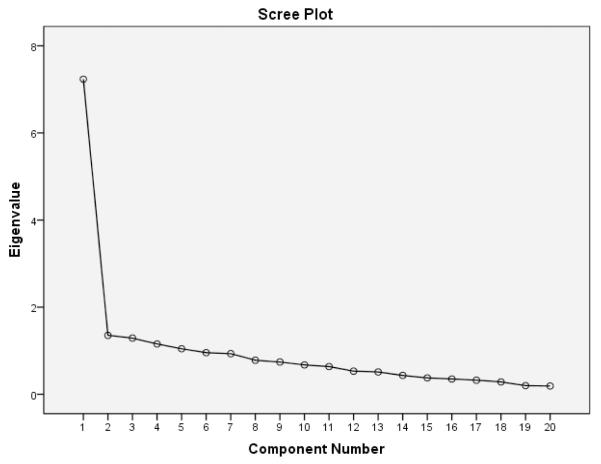

Principal Component Analysis with oblique rotation with the original 20 ELOCS “b” items revealed five eigenvalues above the 1.00 threshold (factor 1=7.23, factor 2=1.35, factor 3=1.29, factor 4=1.16, and factor 5=1.05) accounting for 60.39% of cumulative variance. Inspection of the scree plot (see Figure 1) suggested the retention of one factor accounting for 36.17% of the variance (see also Table 1). Inspection of the single factor solution provided interpretability and utility of the LOC construct.

Figure 1.

Scree Plot of Eigenvalues for Original 20 Items

Table 1.

Original 20-Item Factor Loadings for 2-Factor Solution, Oblique Rotation (Structure Matrix)

| LOC Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| ELOCSlb. Go out of your way to get food you were craving | 0.373 | 0.622 |

| ELOCS2b. Feel helpless to control eating urges | 0.770 | 0.247 |

| ELOCS3b. Give up control over what you ate BEFORE started to eat | 0.359 | 0.530 |

| ELOCS4b. Give in to an impulse to eat even though not hungry | 0.672 | 0.053 |

| ELOCS5b. Ignore an interruption to keep eating | 0.444 | 0.325 |

| ELOCS6b. Ate unhealthy food choices | 0.139 | −0.438 |

| ELOCS7b. Keep eating even though thought should stop | 0.684 | 0.070 |

| ELOCS8b. Eat much more rapidly than normal | 0.405 | 0.704 |

| ELOCS9b. Eat until feel uncomfortably full | 0.458 | 0.109 |

| ELOCS10b. Ate large amount of food when not physically hungry | 0.409 | 0.490 |

| ELOCS11b. Feel embarrassed about how much you were eating | 0.551 | 0.264 |

| ELOCS12b. Feel disgusted, depressed, or very guilty while eating | 0.760 | 0.178 |

| ELOCS13b. Afraid of losing control over eating | 0.676 | 0.245 |

| ELOCS14b. Feel driven or compelled to eat | 0.715 | 0.259 |

| ELOCS15b. Hard to stop eating once started | 0.754 | 0.427 |

| ELOCS16b. Give up even trying to control eating | 0.601 | 0.394 |

| ELOCS17b. Feel upset by the feeling that couldn’t stop eating | 0.758 | 0.396 |

| ELOCS18b. Hard to stop thinking about food you were craving | 0.664 | 0.243 |

| ELOCS19b. Feel out of control when eaten an unusually large amount of food | 0.719 | 0.437 |

| ELOCS20b. Feel out of control when not eaten an unusually large amount of food | 0.330 | 0.438 |

Note. LOC = Loss of Control, ELOCS = Eating Loss of Control Scale.

For the single factor solution, two items (6b and 20b) had factor loadings less than 0.40 (r=0.03, r<0.40, respectively) on the single factor and were removed from the scale (see Table 2a). Table 2b presents the eigenvalues for the remaining 18 items; the single factor solution accounted for 38.94% of the variance. Factor loadings of the final 18 items ranged from r=0.45 to r=0.78.

Table 2a.

20-Item Loss of Control Scale: Means, Standard Deviations, Eigenvalues, % Variance, Factor Loadings, Item-Total Correlations

| LOC Items | N | Mean* | SD | Eigenvalue | % Variance | Factor | Item-Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELOCSlb. Go out of your way to get food you were craving | 167 | 5.39 | 2.74 | 7.233 | 36.166 | 0.479 | 0.428 |

| ELOCS2b. Feel helpless to control eating urges | 168 | 7.01 | 2.59 | 1.353 | 6.767 | 0.752 | 0.667 |

| ELOCS3b. Give up control over what you ate BEFORE started to eat | 164 | 6.62 | 3.33 | 1.290 | 6.450 | 0.445 | 0.398 |

| ELOCS4b. Give in to an impulse to eat even though not hungry | 168 | 8.18 | 1.94 | 1.156 | 5.778 | 0.619 | 0.546 |

| ELOCS5b. Ignore an interruption to keep eating | 165 | 2.99 | 3.88 | 1.045 | 5.224 | 0.475 | 0.424 |

| aELOCS6b. Ate unhealthy food choices | 165 | 5.70 | 3.06 | 0.955 | 4.777 | 0.026 | 0.009 |

| ELOCS7b. Keep eating even though thought should stop | 165 | 7.91 | 1.93 | 0.932 | 4.659 | 0.633 | 0.569 |

| ELOCS8b. Eat much more rapidly than normal | 164 | 5.57 | 3.37 | 0.782 | 3.910 | 0.526 | 0.479 |

| ELOCS9b. Eat until feel uncomfortably full | 168 | 7.54 | 2.30 | 0.741 | 3.707 | 0.438 | 0.376 |

| ELOCS10b. Ate large amount of food when not physically hungry | 167 | 6.11 | 2.37 | 0.674 | 3.371 | 0.481 | 0.400 |

| ELOCS11b. Feel embarrassed about how much you were eating | 165 | 4.76 | 3.66 | 0.636 | 3.181 | 0.558 | 0.502 |

| ELOCS12b. Feel disgusted, depressed, or very guilty while eating | 167 | 6.68 | 3.10 | 0.530 | 2.652 | 0.726 | 0.662 |

| ELOCS13b. Afraid of losing control over eating | 166 | 5.83 | 3.24 | 0.513 | 2.575 | 0.666 | 0.585 |

| ELOCS14b. Feel driven or compelled to eat | 167 | 7.22 | 2.41 | 0.434 | 2.169 | 0.705 | 0.632 |

| ELOCS15b. Hard to stop eating once started | 167 | 7.67 | 2.34 | 0.377 | 1.883 | 0.778 | 0.717 |

| ELOCS16b. Give up even trying to control eating | 167 | 7.11 | 3.00 | 0.351 | 1.756 | 0.632 | 0.577 |

| ELOCS17b. Feel upset by the feeling that couldn’t stop eating | 168 | 7.04 | 2.73 | 0.323 | 1.617 | 0.774 | 0.707 |

| ELOCS18b. Hard to stop thinking about food you were craving | 168 | 6.72 | 2.97 | 0.284 | 1.442 | 0.654 | 0.601 |

| ELOCS19b. Feel out of control when eaten an unusually large amount of food | 165 | 7.44 | 2.54 | 0.200 | 0.998 | 0.749 | 0.693 |

| aELOCS20b. Feel out of control when not eaten an unusually large amount of | 162 | 4.02 | 3.11 | 0.190 | 0.950 | 0.397 | 0.355 |

|

| |||||||

| Loss of Control Scale α=0.887 | 168 | 6.38 | 1.59 | ||||

Measured with likert-type scales scored from 0-10.

Removed due to factor loading <0.40

Note. LOC = Loss of Control, ELOCS = Eating Loss of Control Scale.

Table 2b.

Final 18-Item Loss of Control Scale: Means, Standard Deviations, Eigenvalues, % Variance, Factor Loadings, Item-Total Correlations

| LOC Items | N | Mean* | SD | Eigenvalue | % Variance | Factor | Item-Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELOCSlb. Go out of your way to get food you were craving | 167 | 5.39 | 2.74 | 7.010 | 38.943 | 0.474 | 0.426 |

| ELOCS2b. Feel helpless to control eating urges | 168 | 7.01 | 2.59 | 1.295 | 7.194 | 0.756 | 0.678 |

| ELOCS3b. Give up control over what you ate BEFORE started to eat | 164 | 6.62 | 3.33 | 1.186 | 6.590 | 0.447 | 0.397 |

| ELOCS4b. Give in to an impulse to eat even though not hungry | 168 | 8.18 | 1.94 | 1.066 | 5.952 | 0.615 | 0.533 |

| ELOCS5b. Ignore an interruption to keep eating | 165 | 2.99 | 3.88 | 0.998 | 5.542 | 0.477 | 0.429 |

| ELOCS7b. Keep eating even though thought should stop | 165 | 7.91 | 1.93 | 0.924 | 5.131 | 0.631 | 0.561 |

| ELOCS8b. Eat much more rapidly than normal | 164 | 5.57 | 3.37 | 0.761 | 4.228 | 0.516 | 0.475 |

| ELOCS9b. Eat until feel uncomfortably full | 168 | 7.54 | 2.30 | 0.752 | 4.175 | 0.453 | 0.391 |

| ELOCS10b. Ate large amount of food when not physically hungry | 167 | 6.11 | 2.37 | 0.660 | 3.664 | 0.471 | 0.407 |

| ELOCS11b. Feel embarrassed about how much you were eating | 165 | 4.76 | 3.66 | 0.595 | 3.307 | 0.563 | 0.509 |

| ELOCS12b. Feel disgusted, depressed, or very guilty while eating | 167 | 6.68 | 3.10 | 0.542 | 3.012 | 0.716 | 0.651 |

| ELOCS13b. Afraid of losing control over eating | 166 | 5.83 | 3.24 | 0.435 | 2.417 | 0.673 | 0.601 |

| ELOCS14b. Feel driven or compelled to eat | 167 | 7.22 | 2.41 | 0.393 | 2.182 | 0.709 | 0.637 |

| ELOCS15b. Hard to stop eating once started | 167 | 7.67 | 2.34 | 0.346 | 1.924 | 0.776 | 0.718 |

| ELOCS16b. Give up even trying to control eating | 167 | 7.11 | 3.00 | 0.316 | 1.755 | 0.629 | 0.576 |

| ELOCS17b. Feel upset by the feeling that couldn’t stop eating | 168 | 7.04 | 2.73 | 0.292 | 1.622 | 0.754 | 0.688 |

| ELOCS18b. Hard to stop thinking about food you were craving | 168 | 6.72 | 2.97 | 0.233 | 1.293 | 0.646 | 0.590 |

| ELOCS19b. Feel out of control when eaten an unusually large amount of food | 165 | 7.44 | 2.54 | 0.197 | 1.096 | 0.741 | 0.679 |

|

| |||||||

| Loss of Control Scale α=0.896 | 168 | 6.55 | 1.68 | ||||

Measured with likert-type scales scored from 0-10.

Note. LOC = Loss of Control, ELOCS = Eating Loss of Control Scale.

Loss of Control Scale

This 18-item scale with one factor was conceptualized as the Loss of Control scale. Table 2b presents the item means, standard deviations, factor loadings, and item-total correlations. Item-total correlations for the 18 items ranged from r=0.39 to r=0.72. The scale comprises items that assess feelings and behaviors traditionally associated with feeling out of control during an eating episode. Sample items include “feel helpless to control eating urges,” “eat until feel uncomfortably full,” “feel driven or compelled to eat,” “hard to stop eating once started,” “give up even trying to control eating,” and “feel out of control when eating an unusually large amount of food.” This scale also contains items that capture feelings and cognitions related to losing control including “feel disgusted, depressed, or very guilty while eating,” “feel upset by the feeling that you couldn’t stop eating,” and “hard to stop thinking about food you were craving.” The overall mean for the Loss of Control scale was 6.55 on a scale from 0-Not at All to 10-Extremely/Completely (SD=1.68). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was α=0.90. The highest mean Loss of Control scale ratings were for items 4b (mean=8.18, SD=1.94) and 7b (mean=7.91, SD=1.93), which ask participants to rate “how much did you give in to an impulse to eat even though you were not hungry?” on a scale from 0-“Did not give in” to 10-“Completely gave in” and “how much did you keep eating even though you thought you should stop?” on a scale from 0-“Stopped eating” to 10-“Did not stop eating,” respectively. The lowest mean Loss of Control scale rating was for item 5b (mean=2.99, SD=3.88), which asks participants to rate, “How much did you ignore the interruption (such as a phone call) to keep eating?” on a scale from 0-“Did not ignore interruption to keep eating” to 10-“Completely ignored interruption to keep eating.”

Frequency Items

Table 3 depicts the means and standard deviations for the frequency items. On average, participants experienced an eating episode characterized by LOC-related feelings and/or behaviors 12.63 times (SD=6.31, range=0–56) in the last 28 days. Cronbach’s alpha for the frequency items was α=0.93. The highest mean frequency of LOC episodes in the past 28 days was reported in response to item 7a (mean=17.32, SD=9.19), which asks participants to indicate “During the past four weeks, how many times did you keep eating even though you thought you should stop?” In contrast, the lowest mean frequency of LOC episodes in the last 28 days was reported in response to item 5a (mean=3.43, SD=5.96), which asks participants to indicate “During the past four weeks, how many times did you ignore an interruption (such as a phone call) to keep eating?”

Table 3.

Frequency Items: Ns, Means and Standard Deviations

| Frequency Items | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELOCS 1a. Go out of your way to get food you were craving | 164 | 7.39 | 6.37 |

| ELOCS 2a. Feel helpless to control eating urges | 162 | 14.46 | 9.60 |

| ELOCS 3a. Give up control over what you ate BEFORE started to eat | 160 | 8.03 | 9.26 |

| ELOCS 4a. Give in to an impulse to eat even though not hungry | 162 | 15.62 | 8.67 |

| ELOCS 5a. Ignore an interruption to keep eating | 166 | 3.43 | 5.96 |

| ELOCS 7a. Keep eating even though thought should stop | 163 | 17.32 | 9.19 |

| ELOCS 8a. Eat much more rapidly than normal | 163 | 11.77 | 10.69 |

| ELOCS 9a. Eat until feel uncomfortably full | 167 | 13.40 | 9.57 |

| ELOCS10a. Ate large amount of food when not physically hungry | 163 | 17.21 | 9.39 |

| ELOCS 11a. Feel embarrassed about how much you were eating | 164 | 8.43 | 9.38 |

| ELOCS 12a. Feel disgusted, depressed, or very guilty while eating | 161 | 14.59 | 10.56 |

| ELOCS 13a. Afraid of losing control over eating | 162 | 13.02 | 12.26 |

| ELOCS 14a. Feel driven or compelled to eat | 165 | 15.66 | 9.72 |

| ELOCS 15a. Hard to stop eating once started | 165 | 13.15 | 9.48 |

| ELOCS 16a. Give up even trying to control eating | 165 | 13.95 | 11.19 |

| ELOCS 17a. Feel upset by the feeling that couldn’t stop eating | 163 | 14.61 | 10.38 |

| ELOCS 18a. Hard to stop thinking about food you were craving | 164 | 11.10 | 9.00 |

| ELOCS 19a. Feel out of control when eaten an unusually large amount | 162 | 12.78 | 9.08 |

|

| |||

| Frequency Scale α=0.930 | 167 | 12.63 | 6.31 |

Note. ELOCS = Eating Loss of Control Scale.

Scale Correlations

The mean Loss of Control scale and frequency scores were significantly and positively correlated with each other (r=0.67, p<0.0001).

Demographic Variables

The mean Loss of Control scale and frequency scores were not significantly correlated with age, education, or BMI. The mean Loss of Control scale score did not differ by gender or ethnicity. The mean frequency score significantly differed by gender with women (M=13.41, SD=6.32) reporting more LOC episodes than men (M=10.65, SD=5.87; F(166)=6.69, p=0.01). An exploratory analysis examining mean frequency score across racial and ethnic groups revealed significant differences (F(164)=3.03, p=0.03) with Caucasians reporting the greatest number of LOC episodes (M=13.38, SD=6.33) and Hispanics reporting the fewest (M=8.24, SD=3.96).

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Dichotomous versus Continuous Binge Variables

Table 4 depicts the point-biserial Pearson correlations between the continuous Loss of Control scale items assessing binge characteristics and their corresponding dichotomous EDE items (0=absent, 1=present). All items on the Loss of Control Scale were significantly correlated with their corresponding dichotomous items on the EDE. These results provide additional support for the convergent validity of the Loss of Control scale score.

Table 4.

Point-Biserial Pearson Correlations between ELOCS (continuous) and corresponding EDE (dichotomous) binge eating variables

| EDE Items | ELOCS8b | ELOCS9b | ELOCS10b | ELOCS11b | ELOCS12b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating much more rapidly than usual? |

0.409 *** | −0.012 | 0.124 | 0.141 | 0.170* |

| Eating until you felt uncomfortably full? |

−0.099 | 0.367 *** | −0.007 | 0.062 | −0.082 |

| Eating large amounts of food when you didn’t feel physically hungry? |

0.127 | 0.147 | 0.236 ** | 0.136 | 0.178* |

| Eating alone because you were embarrassed by how much you were eating? |

0.100 | 0.122 | 0.108 | 0.627 *** | 0.344*** |

| Feeling disgusted with yourself, depressed or feeling very guilty after overeating? |

−0.055 | −0.075 | 0.114 | 0.262** | 0.293 *** |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Note. EDE = Eating Disorder Examination, ELOCS = Eating Loss of Control Scale.

Clinical Variables

As summarized in Table 5, the Loss of Control scale and mean frequency scores demonstrated a similar pattern of results and were both significantly and positively correlated with all EDE subscales and global score except for the Restraint scale as well as significantly and positively correlated with all DERS subscales and overall score except for the Awareness scale. Patients who reported greater severity of LOC and more frequent LOC episodes were significantly more likely to report more emotion dysregulation, more symptoms of depression, and less self-control. These results provide additional evidence for convergent validity and discriminant validity (e.g., DERS-Awareness scale). Using partial correlations to control for gender and ethnicity, the pattern of correlations between mean frequency scores and the clinical variables remains the same.

Table 5.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between ELOCS, Frequency and BMI, EDE subscales, DERS, BDI, and BSCS

| Mean | SD | ELOCS | Frequency | Frequencya | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 38.81 | 5.70 | 0.051 | −0.011 | 0.041 |

| EDE-Restraint | 1.63 | 1.25 | 0.149 | 0.100 | 0.073 |

| EDE-Eating Concern | 2.07 | 1.38 | 0.545*** | 0.562*** | 0.539*** |

| EDE-Shape Concern | 3.53 | 1.19 | 0.505*** | 0.424*** | 0.390*** |

| EDE-Weight Concern | 3.10 | 1.10 | 0.426*** | 0.365*** | 0.325*** |

| EDE-Global Score | 2.58 | 0.92 | 0.549*** | 0.493*** | 0.461*** |

| DERS-Overall | 78.66 | 23.21 | 0.433*** | 0.372*** | 0.314*** |

| DERS-Nonacceptance | 11.44 | 4.93 | 0.384*** | 0.323*** | 0.309*** |

| DERS-Goals | 12.79 | 4.88 | 0.386*** | 0.351*** | 0.297*** |

| DERS-Impulse | 12.38 | 5.46 | 0.441*** | 0.349*** | 0.309*** |

| DERS-Awareness | 16.75 | 5.37 | 0.037 | 0.043 | −0.029 |

| DERS-Strategies | 15.30 | 6.20 | 0.414*** | 0.370*** | 0.318*** |

| DERS-Clarity | 10.35 | 3.53 | 0.236** | 0.226** | 0.172* |

| BDI | 14.96 | 8.80 | 0.474*** | 0.394*** | 0.345*** |

| BSCS | 38.92 | 8.37 | −0.389*** | −0.204* | −0.166* |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Partial Correlations controlling for gender and ethnicity.

Note. ELOCS = Eating Loss of Control Scale, BMI = Body Mass Index, EDE = Eating Disorder Examination, DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BSCS = Brief Self-Control Scale.

Frequency of LOC Episodes

Pearson correlations were conducted to assess associations between the ELOCS mean frequency score and the EDE items assessing frequency of OBEs, SBEs, and objective overeating episodes (OOEs) in the past 28 days as well as mean OBEs per month in the past six months. The ELOCS mean frequency score demonstrated good convergent validity and was significantly and positively correlated with the frequency of OBEs in the 28 days prior to intake assessment (r=0.40, p<0.001) and the mean frequency of OBEs per month in the past 6 months (r=0.43, p<0.001). The mean frequency score was also significantly and positively correlated with the frequency of SBEs in the 28 days prior to intake assessment (r=0.22, p=0.005). The ELOCS mean frequency score demonstrated good discriminant validity and was not significantly correlated with the frequency of OOEs (eating episodes with no LOC) in the 28 days prior to intake assessment (r=-0.07, p=0.35). Using partial correlations to control for gender and ethnicity, the pattern of correlations between mean frequency scores and EDE LOC episodes remains the same: frequency of OBEs in the past 28 days (r=0.44, p<0.0001), mean OBEs per month in the past six months (r=0.47, p<0.0001), SBEs in the past 28 days (r=0.21, p<0.01), and OOEs in the past 28 days (r=-0.04, p=0.61).

All analyses were repeated including outliers and results were replicated (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study describes the development and validation of the Eating Loss of Control Scale. Although LOC is a defining feature of binge eating across the spectrum of eating disorders and required for a diagnosis of BED, bulimia nervosa (BN), and anorexia nervosa-binge eating/purging type (AN-BP), this construct has historically been evaluated as a dichotomous variable (present/absent) and examined as a function of OBE and SBE frequency. Such a definition might fail to capture significant variability in the experience of losing control over eating as well as the severity of LOC. Therefore, the goal of ELOCS is to measure multiple aspects of loss of control over eating using continuous, Likert-type questions. The ELOCS was also designed to assess frequency of LOC episodes independent of food amount consumed. In the current sample, participants reported experiencing eating episodes characterized by LOC-related feelings and behaviors on average 13 times in the last month. Overall, findings indicate that the Loss of Control scale score has excellent internal reliability as well as high factor loadings for the LOC construct and item-total correlations. In addition, the mean Loss of Control scale and frequency scores were significantly, positively and moderately correlated with eating pathology, demonstrating good convergent validity.

The Loss of Control scale score was also moderately and positively associated with emotion dysregulation and depression and negatively correlated with self-control, but was not related to OOEs or BMI, providing further evidence for its discriminant validity. These findings extend prior research revealing a relationship between LOC and increased eating disorder and general psychopathology (Colles, Dixon, & O’Brien, 2008; Goossens, et al., 2007; Jenkins et al., 2012; Mond et al., 2006; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2008). Although one might expect there to be a relationship between LOC and restraint (either inversely correlated because the constructs reflect opposing behaviors—restraining one’s eating versus feeling out of control of one’s eating—or positively correlated because of the link between severe restraint and subsequent binge eating), we did not observe a significant relationship between the two in this sample. This finding might be explained by limitations in the measurement of restraint, which has not been found to correlate with actual restrained eating behavior (Stice, Sysko, Roberto, & Allison, 2010), or perhaps to the fact that BED, unlike BN, is generally characterized by very low levels of extreme restraint reflected in the EDE restraint scale (Grilo et al., 2009a). Furthermore, there were also low-to-moderate significant correlations between the ELOCS items that mapped onto EDE items assessing the same binge characteristics in a dichotomous manner, providing further evidence for convergent validity.

Findings for the frequency items also suggest good convergent and discriminant validity. The mean frequency score was significantly associated with OBE frequency, but not with OOE frequency, which are eating occasions involving the consumption of an unusually large amount of food that are not characterized by a LOC. This is consistent with a study by Mitchell et al. (2012) that found that increased LOC, as measured on a 0-4 Likert-type scale, was associated with greater kilocalories ingested across a range of problematic eating episodes characterized by feelings of LOC. In addition, increased LOC was near significantly associated with a higher frequency of OBEs (defined as eating episodes of greater than 1,000 calories) among individuals with BN (Mitchel et al, 2012). As expected, the ELOCS frequency scale was also correlated with SBEs. This is consistent with research showing that both SBEs and OBEs are associated with general and eating psychopathology (Keel, Mayer, & Harnden-Fischer, 2001; Latner, Hildebrandt, Rosewall, Chishold, & Hayashi, 2007; Niego et al., 1997; Picot & Lilenfeld, 2003; Pratt et al., 1998; Latner & Clyne, 2008),

However, the relation between ELOCS frequency and OBEs was stronger than for SBEs. Research suggests that there might be important clinical distinctions between OBEs and SBEs. For example, in a CBT treatment study of female patients with BED, Niego and colleagues (1997) found that SBEs took longer to respond to treatment than OBEs. In addition, some research suggests that although women with either BN or BED experienced reductions in OBEs after a brief, self-monitoring intervention, they had an increase in SBEs (Hildebrandt & Latner, 2006). Furthermore, Latner and colleagues (2007) observed only a small, marginally significant correlation between OBEs and SBEs (r=0.22, p=0.05) in a sample of women with eating disorders, but both types of eating occasions correlated similarly with eating and general psychopathology. In contrast, in a community sample of women with variants of BN and BED, no differences in eating and general psychopathology were observed among those reporting SBEs only versus those reporting OBEs only (Mond et al., 2010).

Taken together, these findings suggest that SBEs are clinically significant eating occasions but also might differ from OBEs in important ways. It is therefore possible that the experience and degree of LOC during an SBE versus an OBE differs for patients with BED. More research is needed to understand the antecedents and function of these two kinds of eating episodes among patients with a range of eating disorders. It is also important to note that this sample comprises men and women with BED who were also obese (BMI 30-55). It is possible that this sample is used to eating larger amounts of food in general (with or without LOC) such that consumption of a ‘small or regular’ amount is retrospectively evaluated as exhibiting less LOC.

The current study makes an important and novel contribution to the field of eating disorder assessment. The paper describes the development and preliminary validation of a scale that examines multiple aspects of LOC eating on continuous measurement scales in a sample of obese men and women with BED. This is the only scale, to our knowledge, that investigates the severity and complexity of the LOC construct, which is a defining characteristic of a binge episode and essential for a diagnosis of BED, BN, and AN-BP. The current study has a number of strengths, including the use of a moderately large sample of treatment-seeking individuals with BED. The assessments included multiple self-report and interview-based assessments, which were administered by trained doctoral-level clinicians, and allowed for the examination of psychometric and clinical validity.

The present study also has several limitations. First, the sample is limited to obese treatment-seeking individuals with BED, but the experience of LOC might be quite variable across ED diagnoses. This paper provides preliminary support for the validity of the ELOCS only in a sample of patients with BED. Future research should examine the validity of the scale with a larger sample size, diverse populations of individuals with different eating disorder diagnoses, as well as clinical and community samples. Although depressive symptoms (BDI, r=0.47) and emotion dysregulation (DERS-overall, r=0.43) were only moderately correlated with LOC, suggesting good discriminant validity, future research should further examine LOC as a construct distinct from negative affect. Findings from the present study also indicated that women reported more LOC episodes than men, although the genders did not differ on the LOC scale scores. Exploring these gender differences in frequency of LOC eating occasions might be a useful area for future research. It will be important to understand whether these are true gender differences in the experience of LOC eating or if men are more reticent than women to endorse the notion that their eating is “out of control.” In addition, our exploratory analyses, based on small sample sizes across racial/ethnic groups, revealed differences in the endorsement of LOC, such that Caucasians reported more LOC episodes, while Hispanic patients had the fewest LOC episodes. These results need to be replicated in future samples and reasons for these potential differences should be explored. To further assess the ELOCS reliability and validity, future research should examine differences in ELOCS scores among eating disorder diagnostic groups (e.g., non-obese BED, BN, and AN). In addition, the test-retest reliability of the scale score has not yet been established and it will be important to examine the ELOCS’ predictive validity in treatment outcome studies and in different demographic groups. In sum, future research with the ELOCS will shed important light on the LOC construct and has the potential to provide important nosological and clinical information for the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of individuals with eating pathology.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by grants to Carlos M. Grilo from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK49587 and K24 DK070052) as well as a grant to Rachel D. Barnes from the National Institutes of Health (K23 DK092279). No additional funding was received for the completion of this work.

Appendix A: ELOCS

Footnotes

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest or competing interests.

Contributor Information

Kerstin K. Blomquist, Department of Psychology, Furman University and Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine

Christina A. Roberto, School of Public Health, Harvard University and Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine.

Rachel D. Barnes, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine

Marney A. White, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine and School of Public Health, Yale University

Robin M. Masheb, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine

Carlos M. Grilo, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine and Department of Psychology, Yale University.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - Text Revision. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R. Manual for revised Beck Depression Inventory. Psychological Corporation; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: 25 years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Celio AA, Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Mitchell J, Walsh BT. A comparison of the binge eating scale, questionnaire for eating and weight patterns-revised, and eating disorder examination questionnaire with instructions with the eating disorder examination in the assessment of binge eating disorder and its symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36:434–44. doi: 10.1002/eat.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment. 1995;5:309–319. doi: 10.1037/pas0000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Loss of Control Is Central to Psychological Disturbance Associated With Binge Eating Disorder. Obesity. 2008;16:608–614. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th ed. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(4):363–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:286–299. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Le Grange D, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Cao L, Mitchell JE. Momentary Affect Surrounding Loss of Control and Overeating in Obese Adults With and Without Binge Eating Disorder. Obesity. 2012;20:1206–1211. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens L, Braet C, Decaluwè V. Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Masheb RM, White MA, Peterson CB, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and sub-threshold bulimia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009a;47(8):692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Masheb RM, White MA, Crow SJ, Mitchell JE. Factor structure of the eating disorder examination interview in patients with binge-eating disorder. Obesity. 2009b;18(5):977–981. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:80–85. doi: 10.1002/eat.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: A replication. Obesity Research. 2001;9:418–422. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001a;69:317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayton JC, Allen DG, Scarpello V. Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods. 2004;7:191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt T, Latner J. Effect of self-monitoring on binge eating: Treatment response or ‘binge drift? European Eating Disorders Review. 2006;14:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins PE, Conley CS, Rienecke Hoste R, Meyer C, Blissett JM. Perception of Control During Episodes of Eating: Relationships with Quality of Life and Eating Psychopathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45:115–119. doi: 10.1002/eat.20913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Mayer SA, Harnden-Fischer JH. Importance of size in defining binge eating episodes in bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29(3):294–301. doi: 10.1002/eat.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latner JD, Hildebrandt T, Rosewall JK, Chisholm AM, Hayashi K. Loss of control over eating reflects eating disturbances and general psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2203–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latner JD, Clyne C. The diagnostic validity of the criteria for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:1–14. doi: 10.1002/eat.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Karr TM, Peat C, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel S, Simonich H. A Fine-Grained Analysis of Eating Behavior in Women with Bulimia Nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45:400–406. doi: 10.1002/eat.20961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Latner JD, Hay PH, Owen C, Rodgers B. Objective and subjective bulimic episodes in the classification of bulimic-type eating disorders: another nail in the coffin of a problematic distinction. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(7):661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niego SH, Pratt EM, Agras WS. Subjective or objective binge: Is the distinction valid? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22(3):291–298. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199711)22:3<291::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picot AK, Lilenfeld LR. The relationship among binge severity, personality psychopathology, and body mass index. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;34(1):98–107. doi: 10.1002/eat.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt EM, Niego SH, Agras WS. Does the size of a binge matter? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24(3):307–312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199811)24:3<307::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire in patients with binge eating disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2006;44:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Elliot C, Wolkoff LE, Columbo KM, Ranzenhofer LM, Roza CA, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Salience of Loss of Control for Pediatric Binge Episodes: Does Size Really Matter? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:707–716. doi: 10.1002/eat.20767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Yanovski SZ, Marcus MD. The questionnaire on eating and weight patterns-revised (QEWP-R) New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Sysko R, Roberto CA, Allison S. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of dietary restriction? Additional objective behavioral and biological data suggest not. Appetite. 2010;54:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Marcus MD, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Loss of control eating disorder in children age 12 years and younger: Proposed research criteria. Eating Behaviors. 2008;9(3):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, Roza CA, Wolkoff LE, Columbo KM, Yanovski JA. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(1):108. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MA, Grilo CM. Diagnostic efficiency of DSM-IV indicators for binge eating episodes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:75–83. doi: 10.1037/a0022210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MA, Kalarchian MA, Masheb RM, Marcus MD, Grilo CM. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery: a prospective 24-month follow-up study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(2):175–184. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04328blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside U, Chen E, Neighbors C, Hunter D, Lo T, Larimer M. Difficulties regulation emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eating Behaviors. 2007;8:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DA, Martin CK, York-Crowe E, Anton SD, Redman LM, Han H, Ravussin E, et al. Measurement of dietary restraint: Validity tests of four questionnaires. Appetite. 2007;48:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski S. Binge eating disorder: current knowledge and future directions. Obesity Research. 1993;1:306–324. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]