Abstract

Background:

Approximately 5-10% of human cancers are thought to be caused by occupational exposure to carcinogens. Compare to other cancers, bladder cancer is most strongly linked to occupational exposure to chemical toxins. This study has been performed to understand which occupations and exposures are related to bladder cancer in Iran.

Materials and Methods:

This study is a case-control study which is conducted on cases with bladder cancer (160 cases) diagnosed in Baharlou hospital in 2007-2009. One hundred sixty cases without any occupational exposure were considered as controls matched for demographic characteristics. Demographic data and characteristics of occupation were compared.

Results:

Mean age of cases and controls were 63.7 and 64 years, respectively (P = 0.841). History of urinary tract stone had significantly difference in two groups (P = 0.039). Occupations such as bus and truck driving, road and asphalt making, mechanics, working in refinery and Petrochemical, plastic, metal manufactory, welding, and pipeline founded a higher risk for bladder cancer rather than controls.

Conclusion:

Our findings on Iranian workers are concurrent and compatible with findings of previous reports about occupational and environmental risk factors of bladder cancer. Although our study population was

Keywords: Bladder cancer, occupation, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Bladder cancer is the most common urinary tract cancer in the world.[11,12] Approximately, 2-6% of total malignant tumors are bladder cancers which make it as the fourth common cancer in males and eighth in females. In US, prevalence of bladder cancer in males is four times of rate in females.[1,2] In Iran, bladder cancer constituted the third prevalent cancer in males and tenth in females in 2005. Incidence of this cancer is 5,000 cases per year and it is fifth most incident cancer in Iran. Compared to other cancers, bladder cancer is strongly linked to occupational exposure to chemicals.[20,21,22] Approximately, 5-10% of human cancers are thought to be caused by occupational exposure to carcinogens. Compare to other cancers, bladder cancer is most strongly linked to occupational exposure to chemical toxins.[14,17,18,19] According to some studies, 21-27% of all bladder cancers in men and 11% of all bladder cancers in women are a result of work exposure.[2,7] This study has been performed to understand which occupations and exposures are related to bladder cancer in Iranian workers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study was a case-control study. Cases were male patients with pathological diagnosis of bladder cancer that were admitted to Baharlou hospital between 2007 and 2009. Controls were male cases without cancers and occupational exposure.[16]

Patients or other cases with no confirmed diagnosis based on pathological findings, unwillingness of patients to cooperate in this study, any other risk factors for cancers were excluded, and any mental and physical disorder that affects speech, memory, orientation, anxiety, and depression were excluded.

Data collection

Data was gathered through patient interview at Baharlou hospital, Tehran, Iran in 2007-2009. Necessary data about cases were asked from bladder cancer patients themselves and recorded on questionnaires specially designed for the study.

Demographic data such as name, family name, age, place of birth, ethnic group, and education were initially gathered. Second, non occupational bladder cancer risk factors including smoking cigarettes or hookah, history of renal stones, chronic urinary tract infections, family history, history of cancer in first-degree relatives, long term drug treatment, utilization of hair dyes, and usual amount of water and liquids use were evaluated. Occupational history topics such as current job title and former ones, duration of each job, exposure to chemicals, cancer in colleagues, etc were also considered in checklists.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 11.5 and possible relationships between variables and bladder cancer analyzed with Pearson Chi-square and confounder variables were controlled by logistic regression.

RESULTS

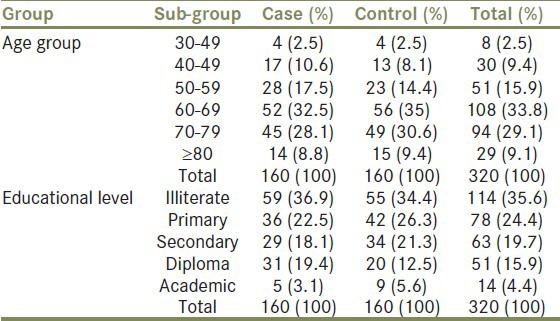

Statistical analysis showed that, mean age of cases and controls were 63.7 and 64 years, respectively. There was no statistically significant mean age difference between case and control groups (P = 0.841) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

Educational level had also no statistically significant difference between case and control groups (PV = 0.341) [Table 1].

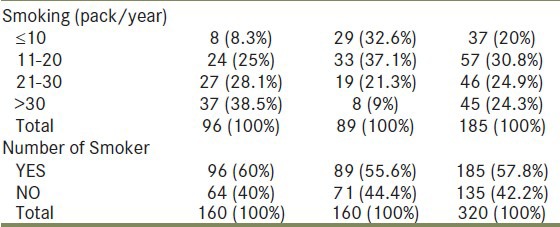

Although, the number of smokers in case group were more than in control group, but data analysis showed that there was no statistically significant difference between case and control group in smoking (P = 0.428) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Cigarette smoking data

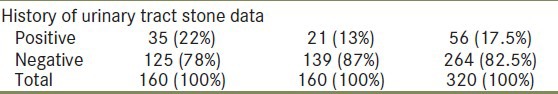

Smoking <20 pack/year in control group was more prevalent than in case group, but smoking >20 pack/year in case group was more prevalent than in control group (P = 0.001) [Table 2]. History of urinary tract stone had statistically significant difference in two groups and was lower in control group (PV = 0.039) [Table 3].

Table 3.

History of urinary tract stone data

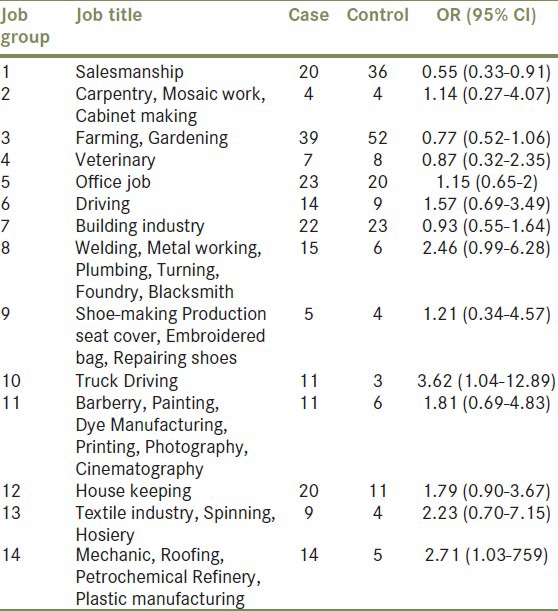

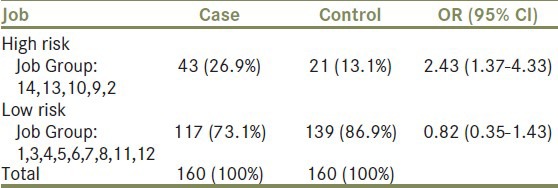

Members of the two groups had more than 80 different jobs. For this reason, jobs were categorized to 14 groups to assess the relationship between individual's job and bladder cancer [Table 4].

Table 4.

Job classification

DISCUSSION

Mean age of male patients with cancer of bladder was 63.7 which is 5 years less than what Linch et al.,[3] reported and 9 years less than what National Informatics Center (NIC)[4] reported. Our bladder cancer patients mostly fell in 60-69 years age group which comprised 32.5% of all. Patients above 65 years old constituted 51%, which is almost 15% less than what Yu et al.,[5] reported. It seems that in Iran bladder cancer develops in men at a lower age than America men. It might be due to an early exposure at lower age to carcinogenic factors such as cigarette and occupational factors. Most of the patients (37%) and control group (34%) were illiterate. It seems there is an inverse relationship between education and bladder cancer; however, correct conclusion should be relative to our knowledge about educational level distribution in general population. There was no statistically significant difference between case and control group about smoking. It seems that this is probably due to cultural, social, and habitual similarity between family members or between two brothers.

Smoking was not more prevalent among cases than in control group. However, heavy smokers were more in case group than in control group. In our study, 40% patients had smoking >20 pack/year; however, 17% of control group had smoking >20 pack/year. This is compatible with many studies that cigarette smoking is the most important risk factor for bladder cancer and there is a dose-response relationship between smoking and increase of bladder cancer risk.[9,10] According to some studies, first degree relatives have increased risk of bladder cancer; however, in our study, none of patients had history of urinary tract cancer in first degree relatives.[6,7,8]

Although in different studies, more than 50 jobs were mentioned to be related to increased risk of bladder cancer,[13] few jobs were high risk for bladder cancer, such as dye manufacturing, leather industry, painting, rubber industry, water-proofing with pitch, mechanics, textile industry, petrochemical refinery, metal working, truck driving, asphalt work, cable production, aluminum industry, production and use of Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH).[15,18,19,20,21] In our study, the proportion of persons with history of high risk occupations in case group was significantly more than control group with OR = 2.43 (1.37-4.33) [Table 5], this is comparable to other studies.

Table 5.

High risk and low risk jobs

Finally, we recommend studies with larger sample size for job analysis specifically, more precise exposure assessment or finding of agent or carcinogenic factor in high risk jobs and to assess other non-occupational bladder cancer risk factor with more accuracy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This project was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran as a specialist thesis

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rugo HS. Occupational cancer. In: Ladou J, editor. Current Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies Inc; 2004. pp. 229–268. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruder AM, Carreon T, Ward EM. Bladder cancer. In: Rosenstock L, Cullen MR, editors. Clinical Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 757–66.0. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch CF, Cohen MB. Urinary system. Cancer. 1995;75:316–29. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<316::aid-cncr2820751314>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rom W.N, Markowitz S.B. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams; 2007. Environmental and Occupational medicine; pp. 813–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu MC, Skipper PL, Tannenbaum SR, Chan KK, Ross RK. Arylamine exposures and bladder cancer risk. Mutat Res. 2002;506-7:21–8. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan P, Bogillot O, Cordier S, Greiser E, Schill W, Vineis P, et al. Cigarette smoking and bladder cancer in men: A pooled analysis of 11 case-control studies. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:289–94. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000415)86:2<289::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan P, Bogillot O, Greiser E, Chang-Claude J, Wahrendorf J, Cordier S, et al. The contribution of cigarette smoking to bladder cancer in women (pooled European data) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:411–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1011214222810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alberg AJ, Kouzis A, Genkinger JM, Gallicchio L, Burke AE, Hoffman SC, et al. A prospective cohort study of bladder cancer risk in relation to active cigarette smoking and household exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:660–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeegers MP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. A prospective study on active and environmental tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk (The Netherlands) Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:83–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1013954932343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjerregaard BK, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Sorensen M, Frederiksen K, Christensen J, Tjønneland A, et al. Tobacco smoke and bladder cancer - in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2412–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverman DT, Hartge P, Morrison AS, Devesa SS. Epidemiology of bladder canser. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1992;6:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pashos CL, Botteman MF, Laskin BL, Redaelli A. Bladder cancer: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:311–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.106011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groah SL, Weitzenkamp DA, Lammertse DP, Whiteneck GG, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF. Excess risk of bladder cancer in spinal cord injury: Evidence for an association between indwelling catheter use and bladder cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:346–51. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.29653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golka K, Bandel T, Schlaefke S, Reich SE, Reckwitz T, Urfer W, et al. Urothelial cancer of the bladder in an area of former coal, iron, and steel industries in Germany: A case-control study. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998;4:79–84. doi: 10.1179/oeh.1998.4.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng T, Cantor KP, Zhang Y, Lynch CF. Occupation and bladder cancer: A population-based, case-control study in iowa. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:685–92. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200207000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kogevinas M, Mannetje A, Cordier S, Ranft U, González CA, Vineis P, et al. Occupation and bladder cancer among men in Western Europe. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:907–14. doi: 10.1023/b:caco.0000007962.19066.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colt JS, Baris D, Stewart P, Schned AR, Heaney JA, Mott LA, et al. Occupation and bladder cancer risk in a population-based case-control study in New Hampshire. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:759–69. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000043426.28741.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dryson E, Walls C, McLean D, Pearce N. Occupational bladder cancer in New Zealand. A 1-year review of cases notified to the New Zealand Cancer Registry. Intern Med J. 2005;35:343–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Band PR, Le ND, MacArthur AC, Fang R, Gallagher RP. Identification of occupational cancer risks in British Columbia: A population-based case-control study of 1129 cases of bladder cancer. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:854–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000169094.77036.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samanic CM, Kogevinas M, Silverman DT, Tardón A, Serra C, Malats N, et al. Occupation and bladder cancer in a hospital-based case-control study in Spain. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:347–53. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.035816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carel R, Levitas-Langman A, Kordysh E, Goldsmith J, Friger M. Case-referent study on occupational risk factors for bladder cancer in southern Israel. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1999;72:304–8. doi: 10.1007/s004200050379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dryson E, ’t Mannetje A, Walls C, McLean D, McKenzie F, Maule M, et al. case-control study of high risk occupations for bladder cancer in New Zealand. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1340–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]