Abstract

Background: Vitamin D status may influence a spectrum of health outcomes, including osteoporosis, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Vitamin D–binding protein (DBP) is the primary carrier of vitamin D in the circulation and regulates the bioavailability of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Epidemiologic studies have shown direct DBP-risk relations and modification by DBP of vitamin D–disease associations.

Objective: We aimed to characterize common genetic variants that influence the DBP biochemical phenotype.

Design: We conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of 1380 men through linear regression of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the Illumina HumanHap500/550/610 array on fasting serum DBP, assuming an additive genetic model, with adjustment for age at blood collection.

Results: We identified 2 independent SNPs located in the gene encoding DBP, GC, that were highly associated with serum DBP: rs7041 (P = 1.42 × 10−246) and rs705117 (P = 4.7 × 10−91). For both SNPs, mean serum DBP decreased with increasing copies of the minor allele: mean DBP concentrations (nmol/L) were 7335, 5149, and 3152 for 0, 1, and 2 copies of rs7041 (T), respectively, and 6339, 4280, and 2341, respectively, for rs705117 (G). DBP was also associated with rs12144344 (P = 5.9 × 10−7) in ST6GALNAC3.

Conclusions: In this GWAS analysis, to our knowledge the first to examine this biochemical phenotype, 2 variants in GC—one exonic and one intronic—were associated with serum DBP concentrations at the genome-wide level of significance. Understanding the genetic contributions to circulating DBP may provide greater insights into the vitamin D binding, transport, and other functions of DBP and the effect of vitamin D status on health outcomes. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention clinical trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00342992.

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin D–binding protein (DBP)5, or group-specific component, is a 58-kDa glycoprotein synthesized in the liver. As the primary carrier of the vitamin D compounds 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in the circulation (1, 2), DBP transports them to target tissues, affects their bioavailability, and may modify their effects on disease risk. DBP also has macrophage-activating, actin-scavenging, and fatty acid–binding functions (3). DBP circulates in significant molar excess of vitamin D and, as a result, <5% of DBP has a vitamin D ligand (1, 3). Epidemiologic studies have suggested that DBP polymorphisms affect its binding affinity for vitamin D compounds and may be directly related to disease risk (3–5). The role of vitamin D in the etiology of cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, diabetes, and cancers has been of substantial interest; however, despite the biological plausibility, the human data remain inconclusive (6, 7).

Previous studies, including one from our group (8), have shown that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene encoding DBP, GC (ie, rs7041 and rs4588), are associated with circulating 25(OH)D (5, 8, 9). These variants result in 3 different DBP isotypes (Gc1F, Gc1S, and Gc2) (10, 11), the latter of which relates to concentrations of both DBP (12) and 25(OH)D (13, 14). The 3 forms are identical in amino acid sequence except at positions 416 and 420 (10, 11); Gc1F and Gc1S have aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues, respectively, at position 416; and Gc2 has a lysine at position 420, instead of a threonine found in the Gc1 isoforms. This biological diversity in DBP may play a role in (and modify) vitamin D–disease risk associations.

Although the GC variants associated with circulating 25(OH)D have been well characterized, SNPs in GC and other genes that may influence DBP concentrations and its functionality are not completely understood. We therefore conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of serum DBP in a cohort of middle-aged men.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study subjects

We conducted a GWAS of serum DBP concentrations in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention (ATBC) Study—a randomized controlled cancer prevention trial of α-tocopherol and β-carotene supplementation conducted in southwestern Finland from 1985 to 1993 (15). At study entry, participants were male smokers of white ancestry aged 50–69 y who did not report a history of cancer, have severe illnesses limiting long-term participation, and were not taking vitamin E (>20 mg/d), vitamin A (>20,000 IU/d), or β-carotene (>6 mg/d) supplements. The 1380 subjects in the current analysis represented all those from prior case-control GWAS of lung, pancreatic, bladder, and advanced prostate cancers (280 cancer cases and 1100 cancer-free controls) who also had serum 25(OH)D and DBP measured previously. The ATBC Study was approved by the institutional review boards of both the US National Cancer Institute and the National Public Health Institute of Finland (now National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland). All participants provided written informed consent before randomization.

Measurement of serum DBP

Fasting serum samples were collected at entry into the ATBC Study and stored at −70°C until analyzed. DBP was measured by using the Quantikine Human Vitamin D Binding Protein Immunoassay kit (catalog number DVDBP0; R&D Systems) at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research (Frederick, MD). Blinded, duplicate quality-control samples were included in each batch, and interbatch and intrabatch CVs were 10.8% and 15.2%, respectively (16–18).

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed at the National Cancer Institute Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory by using the Illumina HumanHap500/550/610 array. Quality-control assessment of genotypes including sample completion, SNP call rates, concordance rates, deviation from fitness for the Hardy-Weinberg proportions, and final sample selection for analyses are detailed elsewhere (19–22).

Statistical analysis

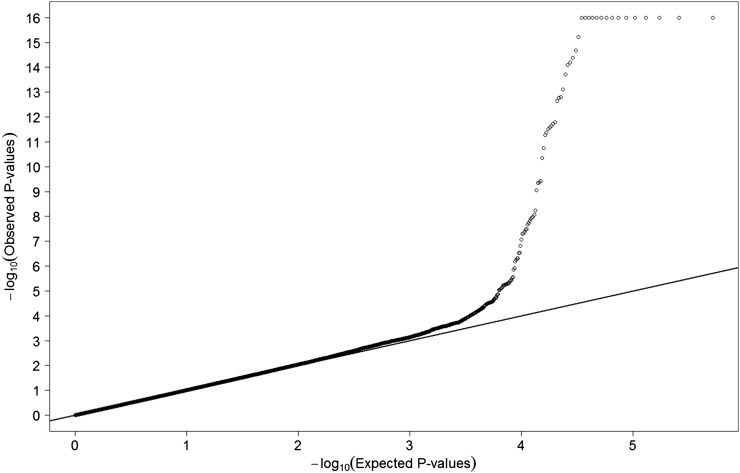

The distribution of serum DBP was close to normal; thus, we did not transform the concentrations to keep the findings more interpretable. To examine the genotype-serum DBP associations, we performed linear regression with DBP as the dependent variable assuming an additive genetic model of the genotype data and adjusted for age at blood collection (continuous). Serum DBP did not differ by case-noncase status, and inclusion of case status in the models did not change the results; it was therefore not included in the final model. The Wald's test was used to test the association between each SNP (n = 591,610) and serum DBP. Results from the quantile-quantile plot (Figure 1) of P values from the GWAS analysis indicate no systematic type I error inflation (λGC = 1.0053).

FIGURE 1.

Quantile-quantile plot of the 591,610 single nucleotide polymorphisms from the genome-wide association study scan (n = 1380; λGC = 1.0053).

To determine independent signals in gene loci containing multiple SNPs significantly associated with circulating DBP at the genome-wide significance level (eg, chromosome 4, GC gene region), we performed a conditional test on all SNPs in the region adjusting by the strongest associated SNP (eg, rs7041). To identify additional independent signals for SNPs located in the region, conditional testing of the remaining SNPs on the chromosome was performed, with adjustment for the top 2 SNPs (eg, rs7041 and rs705117). To determine whether additional SNPs in the GC region not included on the initial Illumina HumanHap500/550/610 array may be associated with serum DBP, we used the software program IMPUTE2 (23) to impute additional SNPs 500 kb upstream and downstream of the GC region.

To test SNPs in biologically relevant genes that did not reach genome-wide significance for association with DBP, we conducted interaction analyses between the nonsignificant SNPs with initial scan P values <5.0 × 10−5 and the 2 genome-wide significant independent signals (ie, rs7041 and rs705117) on chromosome 4. Wald's test with 1 df was used to test the interaction between SNPs. We also examined the joint effect of multiple SNPs within a gene by using a gene-based test (24). To narrow down the list of SNPs to examine in detail with interaction analyses and gene-based tests, a cutoff of P < 5.0 × 10−5 for initial scan values was used. We used Genome-Wide Complex Trait Analysis version 1.13 (25, 26) to perform a heritability analysis to estimate the variance in serum DBP explained by all the SNPs considered in the GWAS.

When combining SNPs from multiple genes to examine the cumulative association between genetic variants and DBP, a polygenic score variable was created that indicated the total number of alleles across SNPs (rs7041, rs705117, rs12144344, and rs6684432) associated with lower DBP (ie, the 4 SNPs were each coded based on 0, 1, or 2 low DBP alleles). To account for the different effect sizes of each SNP (ie, strength of association with serum DBP), each SNP within the polygenic score was multiplied by its corresponding β from a model that contained all 4 SNPs. Linear regression for the polygenic score was performed 2 ways, assuming an additive genetic model: 1) modeling the weighted score variable as a continuous variable and 2) modeling indicator variables for categories of the weighted score, again with adjustment for age at blood collection. All analyses were conducted by using SAS (version 9.2) and R (version 3.0.1).

RESULTS

A total of 591,610 genotyped SNPs in 1380 men from the ATBC Study were examined for association with fasting serum DBP. The mean (±SD) age at the time of study enrollment and blood collection for this sample was 58.3 ± 5.0 y, and the mean BMI (in kg/m2) was 26.2 ± 3.7.

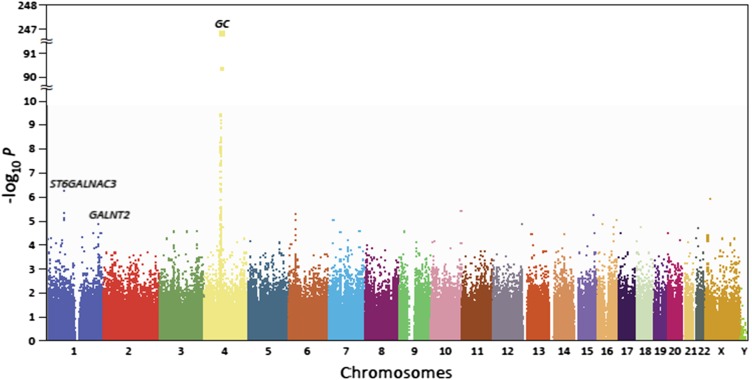

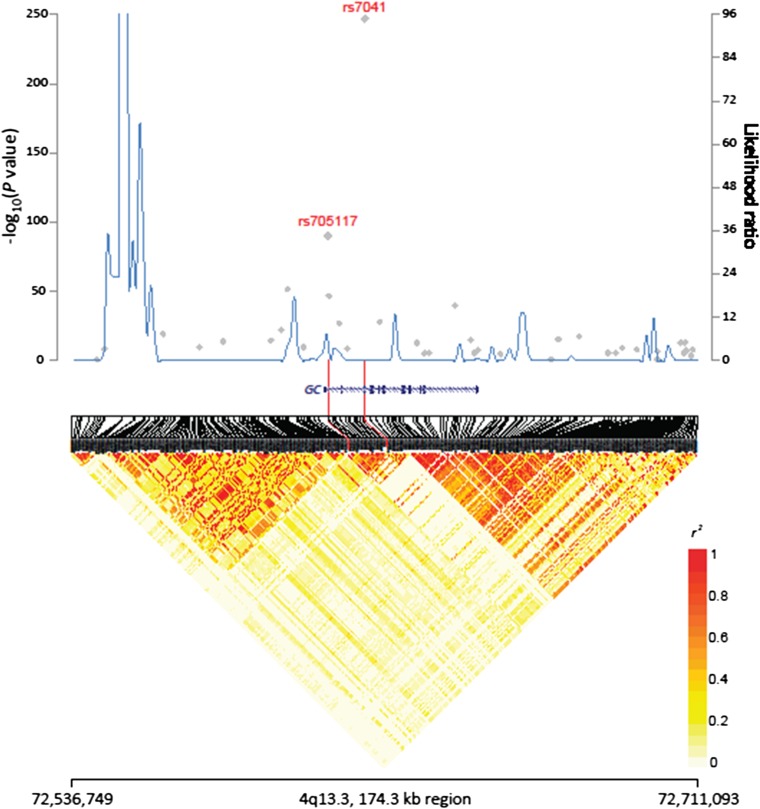

The individual SNP-serum DBP association P values from the GWAS are plotted by chromosome in Figure 2. A total of 59 SNPs on chromosome 4 reached genome-wide significance (P < 5.0 × 10−8) for association with DBP; the strongest signals were in the region harboring the group-specific component gene, GC, which encodes DBP. The most significant association was with rs7041 in exon 11 (P = 1.42 × 10−246; Table 1 and Figure 2). The average difference in mean DBP concentration per copy of the minor allele (T) in rs7041 was −2109 nmol/L (Table 1); ie, individuals with 2 copies of the minor allele had a DBP concentration ∼57% lower than those with no copies of the minor allele. By using the coefficient of determination, we estimated that rs7041 accounts for 45.0% of the variation in circulating DBP. By using regression models conditioned on rs7041, we assessed the independence of the associations between the remaining SNPs on chromosome 4 with initial-scan P values <0.05 (n = 1904) and identified a second SNP associated with serum DBP, rs705117 (initial scan P = 4.7 × 10−91; Table 1), located in an intronic region of GC and in high (but not perfect) linkage disequilibrium (LD) with rs7041 (r2 = 0.28, D’ = 1.00). After adjustment for rs7041, rs705117 remained significantly associated with DBP (P = 5.9 × 10−12). The P value of the joint signals from rs7041 and rs705117 was 2.02 × 10−263, and we estimated that the 2 SNPs accounted for 46.8% of the variation in serum DBP. Results from a heritability analysis estimated that 60% of the variance in serum DBP was explained by all the SNPs considered in the GWAS. All the remaining SNPs on chromosome 4 were nonsignificant after adjustment for rs7041 and rs705117 (P > 5 × 10−3). SNP rs2282679, a proxy for rs4588, which has been associated with DBP and 25(OH)D concentrations (5), was also significantly associated with serum DBP (initial scan P = 3.4 × 10−47) but did not remain significant after adjustment for rs7041. The underlying LD and recombination hot spots for this region of chromosome 4 are shown in Figure 3; rs2282679 and rs7041 are in high LD (r2 = 0.49, D′ = 1.00).

FIGURE 2.

Genome-wide associations of circulating vitamin D–binding protein by chromosome position and –log10 P value from linear regression.

TABLE 1.

Association between SNPs and serum DBP concentration: ATBC Study1

| DBP by genotype5 |

||||||||||

| SNP2 | Minor allele (frequency) | Chromosome | Location3 | Gene neighborhood | P4 | 0 Minor alleles | 1 Minor allele | 2 Minor alleles | β6 | SE6 |

| nmol/L | ||||||||||

| rs7041 | T (0.35) | 4 | 72837198 | GC | 1.42 × 10−246 | 7335 ± 2031 | 5149 ± 1238 | 3152 ± 1035 | −2109.34 | 63.35 |

| rs705117 | G (0.13) | 4 | 72826979 | GC | 4.68 × 10−91 | 6339 ± 2057 | 4280 ± 1204 | 2341 ± 1077 | −2026.78 | 100.91 |

| rs12144344 | T (0.44) | 1 | 76612124 | ST6GALNAC3 | 5.93 × 10−7 | 5408 ± 1970 | 5825 ± 2221 | 6200 ± 2113 | 396.39 | 80.21 |

| rs6684432 | T (0.16) | 1 | 228276413 | GALNT2 | 1.36 × 10−5 | 5625 ± 2051 | 6097 ± 2304 | 6578 ± 2310 | 457.73 | 109.81 |

ATBC, Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention; DBP, vitamin D–binding protein; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

National Center for Biotechnology Information dbSNP identifier.

National Center for Biotechnology Information Human Genome Build 36 location.

1-df test from linear regression assuming an additive model, adjusted for age at blood collection (continuous).

Values are means ± SDs.

Linear regression β and its SE were calculated by using untransformed DBP.

FIGURE 3.

Regional plot of association, recombination hot spots, and linkage disequilibrium for rs7041 and rs705117 on chromosome 4. Association results from a trend test in –log10 (P values) (gray diamonds) of the single nucleotide polymorphisms are shown according to their chromosomal positions. Linkage disequilibrium structure based on the 1000 Genomes Finnish data (n = 93) was visualized by snp.plotter, R software. The line graph shows likelihood ratio statistics for recombination hot spot by SequenceLDhot software based on the background recombination rates inferred by PHASE v2.1 with the use of 1000 Genomes Finnish data. Physical locations are based on National Center for Biotechnology Information human genome build 37. Gene annotation was based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information RefSeq genes from the UCSC Genome Browser.

To further fine-map the GC region of chromosome 4, we performed imputation analysis. Imputation results of this region did not yield any additional SNPs associated with serum DBP (all P values >0.001; data not shown). Examination of rs7041 in relation to serum concentrations of 25(OH)D and “free 25(OH)D” [estimated on the basis of total 25(OH)D and DBP by using the affinity constants of albumin and DBP (27, 28) and assigning a fixed albumin value to every subject as previously described (18)], showed that individuals with 2 copies of the minor allele (T) in rs7041 had a 25(OH)D concentration that was ∼17% lower and 180% more estimated free circulating 25(OH)D than did those with no copies of the minor allele. A higher number of copies of the minor allele of rs705117 was not significantly associated with total serum 25(OH)D, but individuals with 2 copies of the minor allele had 2.25 times the amount of estimated free circulating 25(OH)D than did those with no copies of the minor allele (data not shown).

In addition to the SNPs that reached genome-wide significance, we found several with initial scan P values <5.0 × 10−5 in genes that have biologically plausible associations with DBP (ie, ST6GALNAC3, GALNT2, LRP2, and CUBN). There were 4 SNPs on chromosome 1 in the gene region of ST6GALNAC3 that in the initial scan had P values <10−5. The gene ST6GALNAC3 encodes ST6(alpha-N-acetyl-neuraminyl-2,3-β-galactosyl-1,3)-N-acetylgalactosaminide alpha-2,6-sialyltransferase 3—a sialyltransferase that catalyzes the transfer of sialic acid to terminal positions of carbohydrate groups in glycoproteins, including possibly DBP itself, with consequent effects on its synthesis, circulating concentrations, and possibly function. The SNP in this region with the strongest signal was rs12144344 (P value = 5.93 × 10−7; Table 1). In conditional regression models including rs12144344, the associations for the other 3 SNPs in this region with initial-scan P values <10−5 (rs2209458, P value = 4.90 × 10−6; rs9437435, P value = 7.99 × 10−6; rs2392030, P value = 9.94 × 10−6) showed marked attenuation, which indicated that the signals for these variants originate from a common locus. Consistent with this, the SNPs were highly correlated with rs12144344; the r2 values for rs2209458, rs9437435, and rs2392030 were 0.93, 0.91, and 0.69, respectively, and the corresponding D′ values were 0.98, 0.98, and 0.88. The underlying LD and recombination hot spots for this region are shown elsewhere (see Supplemental Figure 1 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue). Given the potential biological relevance, we also performed a gene-based test to assess the association between variants in ST6GALNAC3 and circulating DBP, which gave an overall P value of 2.4 × 10−4.

Also associated with DBP at the P < 5.0 × 10−5 level were 3 SNPs on chromosome 1 in the gene region of GALNT2, encoding UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2 (GalNAc-T2)—a glycotransferase that catalyzes the transfer of N-acetyl galactosamine to the hydroxyl group of a serine or threonine residue in the first step of O-linked oligosaccharide biosynthesis. Given that glycosylation of DBP involves O-linkage at either threonine or serine residues (Ser/Thr418, Thr420) in domain III of the protein (29, 30), variants in GALNT2 could in theory affect DBP concentrations. The SNP with the strongest association in this region was rs6684432 (P = 1.36 × 10−5; Table 1). Conditional regression models with rs66884432 showed attenuation of the associations of the other 2 SNPs in this region: rs632557 (initial P = 4.73 × 10−5) and rs678050 (initial P = 9.32 × 10−5). Recombination hot spots and underlying LD for this region are shown elsewhere (see Supplemental Figure 2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue). The gene-based test for GALNT2 gave an overall P value of 9.7 × 10−4.

Even though reabsorption of DBP and vitamin D in the renal proximal tubules is known to be mediated by the plasma membrane receptor proteins megalin and cubilin (31–34), we did not find evidence to support associations between DBP and variants in the genes encoding them (LRP2 and CUBN, respectively). For example, rs2247506 in the region of LRP2 on chromosome 2 had a P value of 0.03 for association with DBP, and rs10904855 in the region of CUBN on chromosome 10 had a P = 0.035.

To examine the collective association between alleles identified in this GWAS and DBP, we created a weighted score variable by multiplying the β values for the individual SNPs from the GWAS and adding them. The difference in serum DBP for those in the fourth quartile of the weighted score compared with the first quartile was 3652 nmol/L, or a decrease of ∼54% (P < 0.0001; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Associations between 4-SNP score and serum DBP concentration: ATBC Study1

| Weighted score | No. of subjects | DBP2 | β3 | SE3 | 4 |

| nmol/L | |||||

| Continuous | 1378 | −1.00 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | |

| Quartiles | |||||

| ≤−143.68 | 459 | 7452.02 ± 2074.13 | — | — | — |

| >−143.68 to ≤1516.42 | 266 | 6003.78 ± 1681.61 | −1453.54 | 125.88 | <0.0001 |

| >1516.42 to ≤2211.59 | 342 | 5145.14 ± 1091.29 | −2307.18 | 116.42 | <0.0001 |

| >2211.59 | 311 | 3802.14 ± 1318.47 | −3651.62 | 119.72 | <0.0001 |

ATBC, Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention; DBP, vitamin D–binding protein; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Values are means ± SDs.

The regression β and its SE were calculated by using untransformed DBP with linear regression, adjusted for age at blood collection (continuous).

For continuous variables, this is a 1-df test from linear regression. For categorical variables, this is a 1-df Wald test.

DISCUSSION

In this GWAS analysis, we identified 2 independent SNPs located in the gene encoding DBP, GC, that influence circulating DBP concentrations. Previous studies have found exonic variants in GC to be associated with DBP concentrations, but the intronic SNP identified here is a novel finding. Although the variants in ST6GALNAC3 and GALNT2 did not reach genome-wide significance, they are biologically relevant and plausible because their protein transcripts (ie, enzymes) may be involved in posttranslational modification of DBP, which may in turn affect vitamin D binding, transport, or metabolism. Further studies are needed to confirm these preliminary associations with biologically plausible genes; however, our findings may provide insight into the role that vitamin D and DBP play in the etiology of various diseases.

Although the current study was, to our knowledge, the first GWAS of circulating DBP, Lauridsen et al (12) previously identified rs7041 and rs4588 as the GC variants responsible for the 3 most common DBP/GC isotypes that result in differing serum DBP concentrations. The results of the current study are consistent with this because we noted significantly lower circulating DBP concentrations with an increasing number of minor alleles of rs7041. Although the genotyping platform used in the current study did not include rs4588, it included rs2282679—an accepted proxy of rs4588—and we observed lower serum DBP in men with a higher number of minor alleles of rs2282679 (although the association was not significant after adjustment for rs7041). Our results differ from those of previous candidate gene studies because we also identified an intronic SNP, rs705117, as independently associated with DBP. Although rs705117 remained significantly associated with DBP after conditioning on rs7041, we noted that rs705117 and rs7041 are in relatively high LD (r2 = 0.28, D’ = 1.00). Given the close proximity of rs7041 and rs705117 (10,219 kb apart) and their high LD, it is plausible that intronic rs705117 may be involved in the regulation of GC transcription, and functional studies to examine this potential role are warranted. The association between rs705117 and serum DBP also requires replication in other studies.

We identified a novel SNP, rs12144344, in the gene ST6GALNAC3 that approached genome-wide significance (P = 5.56 × 10−7) for association with DBP concentrations. The sialyltransferase encoded by ST6GALNAC3 is expressed in human spleen, kidney, lung, and brain and catalyzes the synthesis of branched-type disialyl structures by transfer of a sialic acid onto a GalNAc residue (35, 36). Others have shown that GC isoforms differ with respect to the degree of glycosylation (4, 37). Gc1F and Gc1S are glycosylated at residues 418 and 420, whereas Gc2 shows only a positively charged lysine at position 420 (4, 37). It is possible that variants in ST6GALNAC3 could influence the absolute or proportional amounts of the DBP isotypes.

We also identified an association between DBP and a SNP in GALNT2, which encodes the protein GalNac-T2. This association did not achieve genome-wide significance (P = 1.33 × 10−5). GalNac-T2 is a glycotransferase catalyzing the transfer of GalNAc to the polypeptide hydroxyl groups of serine and threonine residues, which would include Ser/Thr418 and Thr420 in the actin binding domain III of DBP (29, 30, 38). Variation in such posttranslational modification of DBP could affect DBP synthesis and functionality, including both actin scavenging and vitamin D binding (as a result of the proximity of domains I and III in the tertiary conformational structure).

Our findings indicate that circulating DBP concentrations are associated with variants in several genes, although the phenotypic gradient and statistical significance were strongest for SNPs in GC. Examination of DBP in relation to a polygenic risk score consisting of the variant alleles in GC, ST6GALNAC3, and GALNT2 that were associated with DBP in the GWAS showed that men with a greater number of low DBP alleles had a significantly lower circulating DBP concentration than did men with fewer low DBP alleles. Additional studies in other populations should examine this. Our findings highlight the need to account for serum DBP in vitamin D association studies. For example, Powe et al (39) examined the distribution of the 3 DBP isotypes in homozygous participants and, consistent with previous reports (1, 4), found Gc1F to be the most prevalent isotype in blacks and Gc1S to be the most prevalent isotype in whites. Circulating DBP was lowest in Gc1F homozygous subjects and highest in Gc1S homozygous subjects, resulting in similar estimated bioavailable 25(OH)D in blacks and whites (39). Given that bioavailable 25(OH)D appears to be influenced by isotype and concentration of DBP (14, 39), assessment of DBP in studies of vitamin D in health outcomes should help clarify the associations.

To our knowledge, the current study was the first GWAS to examine the DBP serologic phenotype. The genetic variants identified may alter the primary or secondary structures of DBP and result in altered affinity for specific vitamin D metabolites, or changes in actin scavenger, macrophage-activating factor and fatty acid-binding functions, and the one intronic SNP signal identified would be consistent with a regulatory function. Strengths of our study include the relatively large sample size with complete genotype information and serum measurement of DBP and the high quality control in both our genotyping and serologic laboratories. Potential limitations include the use of serum from a single time point and the lack of replication in another population. It is possible that a larger sample size would have helped better elucidate the associations between the biologically plausible rs12144344 and rs6684432 and serum DBP, because these associations were just outside of genome-wide significance. Whereas measuring DBP at multiple time points would be useful, DBP concentrations are stable throughout life and show little variation by season (2). In addition, our study was only able to include men of European ancestry. It is possible that the homogeneous study population limited our ability to discriminate the effects of rs7041 and rs2282679, an accepted proxy for rs4588, an SNP that has been associated with circulating DBP (14). Variants in rs7041 and rs4588 determine which of the 3 GC isotypes an individual carries; among individuals with European ancestry such as the current study population, Gc1S is the most common isotype—50–60% of the population has the Gc1S-allele (2), followed by Gc2, and Gc1F, which is the least prevalent (<20%) (1, 2). Gc1F and Gc2 share the T allele at rs7041 but differ at rs4588; given the low prevalence of Gc1F among individuals with European ancestry, it is possible that we did not observe a significant association between the rs4588 proxy, rs2282679, and serum DBP after adjusting for rs7041 because of the small proportion of Gc1F individuals. Inclusion of individuals of African ancestry (ie, those with the highest prevalence of Gc1F) in future studies is warranted. Even though our study population was limited to those of European ancestry, we did identify statistically significant independent associations between DBP status and both rs7041 and rs705117 in the sample.

In conclusion, in this cohort of Finnish men, variants in the gene encoding DBP and in genes encoding enzymes that may be involved in its posttranslational modification were associated with circulating DBP concentrations. Understanding the genetic contributions to DBP status may provide greater insights into vitamin D binding, transport, and functionality of DBP and the role of DBP in vitamin D–health outcome relations. Replication of the current findings in other populations, particularly women and other races and ethnicities, is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—KAM and DA: designed the research; CCC and SM: provided the essential materials; KAM, HZ, WW, and KY: analyzed the data or performed the statistical analysis; KAM, AMM, HZ, SJW, SM, KY, SJC, and DA: wrote the manuscript; and KAM and AMM: had responsibility for the final content. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: ATBC, Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention; DBP, vitamin D–binding protein; GalNAc-T2, UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2; GWAS, genome-wide association study; LD, linkage disequilibrium; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chun RF. New perspectives on the vitamin D binding protein. Cell Biochem Funct 2012;30:445–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speeckaert M, Huang G, Delanghe JR, Taes YE. Biological and clinical aspects of the vitamin D binding protein (Gc-globulin) and its polymorphism. Clin Chim Acta . 2006;372:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomme PT, Bertolini J. Therapeutic potential of vitamin D-binding protein. Trends Biotechnol 2004;22:340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik S, Fu L, Juras DJ, Karmali M, Wong BY, Gozdzik A, Cole DE. Common variants of the vitamin D binding protein gene and adverse health outcomes. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2013;50:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrath JJ, Saha S, Burne TH, Eyles DW. A systematic review of the association between common single nucleotide polymorphisms and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;121:471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung M, Balk EM, Brendel M, Ip S, Lau J, Lee J, Lichtenstein A, Patel K, Raman G, Tatsioni A, et al. Vitamin D and calcium: a systematic review of health outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2009;183:1–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross AC Taylor CL Yaktine AL Del Valle HB eds. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn J, Yu K, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Simon KC, McCullough ML, Gallicchio L, Jacobs EJ, Ascherio A, Helzlsouer K, Jacobs KB, et al. Genome-wide association study of circulating vitamin D levels. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:2739–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang TJ, Zhang F, Richards JB, Kestenbaum B, van Meurs JB, Berry D, Kiel DP, Streeten EA, Ohlsson C, Koller DL, et al. Common genetic determinants of vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide association study. Lancet 2010;376:180–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooke NE, David EV. Serum vitamin D-binding protein is a third member of the albumin and alpha fetoprotein gene family. J Clin Invest 1985;76:2420–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang F, Brune JL, Naylor SL, Cupples RL, Naberhaus KH, Bowman BH. Human group-specific component (Gc) is a member of the albumin family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1985;82:7994–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauridsen AL, Vestergaard P, Nexo E. Mean serum concentration of vitamin D-binding protein (Gc globulin) is related to the Gc phenotype in women. Clin Chem 2001;47:753–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnaud J, Constans J. Affinity differences for vitamin D metabolites associated with the genetic isoforms of the human serum carrier protein (DBP). Hum Genet 1993;92:183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauridsen AL, Vestergaard P, Hermann AP, Brot C, Heickendorff L, Mosekilde L, Nexo E. Plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D are related to the phenotype of Gc (vitamin D-binding protein): a cross-sectional study on 595 early postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 2005;77:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The ATBC Cancer Prevention Study Group. The alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene lung cancer prevention study: design, methods, participant characteristics, and compliance. Ann Epidemiol 1994;4:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mondul AM, Weinstein SJ, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Influence of vitamin D binding protein on the association between circulating vitamin D and risk of bladder cancer. Br J Cancer 2012;107:1589–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein SJ, Mondul AM, Kopp W, Rager H, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin D-binding protein and risk of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer . 2013;132:2940–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein SJ, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Kopp W, Rager H, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Impact of circulating vitamin D binding protein levels on the association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and pancreatic cancer risk: a nested case-control study. Cancer Res 2012;72:1190–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amundadottir L, Kraft P, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Fuchs CS, Petersen GM, Arslan AA, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Gross M, Helzlsouer K, Jacobs EJ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the ABO locus associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Nat Genet 2009;41:986–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter DJ, Kraft P, Jacobs KB, Cox DG, Yeager M, Hankinson SE, Wacholder S, Wang Z, Welch R, Hutchinson A, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies alleles in FGFR2 associated with risk of sporadic postmenopausal breast cancer. Nat Genet 2007;39:870–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landi MT, Chatterjee N, Yu K, Goldin LR, Goldstein AM, Rotunno M, Mirabello L, Jacobs K, Wheeler W, Yeager M, et al. A genome-wide association study of lung cancer identifies a region of chromosome 5p15 associated with risk for adenocarcinoma. Am J Hum Genet 2009;85:679–91 Am J Hum Genet 2011;88:861.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas G, Jacobs KB, Yeager M, Kraft P, Wacholder S, Orr N, Yu K, Chatterjee N, Welch R, Hutchinson A, et al. Multiple loci identified in a genome-wide association study of prostate cancer. Nat Genet 2008;40:310–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu K, Li Q, Bergen AW, Pfeiffer RM, Rosenberg PS, Caporaso N, Kraft P, Chatterjee N. Pathway analysis by adaptive combination of P-values. Genet Epidemiol 2009;33:700–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Benyamin B, McEvoy BP, Gordon S, Henders AK, Nyholt DR, Madden PA, Heath AC, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat Genet 2010;42:565–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet 2011;88:76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-oanzi ZH, Tuck SP, Raj N, Harrop JS, Summers GD, Cook DB, Francis RM, Datta HK. Assessment of vitamin D status in male osteoporosis. Clin Chem 2006;52:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bikle DD, Gee E, Halloran B, Kowalski MA, Ryzen E, Haddad JG. Assessment of the free fraction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in serum and its regulation by albumin and the vitamin D-binding protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986;63:954–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viau M, Constans J, Debray H, Montreuil J. Isolation and characterization of the O-glycan chain of the human vitamin-D binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1983;117:324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto N. Macrophage activating factor from vitamin D binding protein.US patent No. 5,326,749, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaseda R, Hosojima M, Sato H, Saito A. Role of megalin and cubilin in the metabolism of vitamin D(3). Ther Apher Dial 2011;15(suppl 1):14–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nykjaer A, Dragun D, Walther D, Vorum H, Jacobsen C, Herz J, Melsen F, Christensen EI, Willnow TE. An endocytic pathway essential for renal uptake and activation of the steroid 25-(OH) vitamin D3. Cell 1999;96:507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nykjaer A, Fyfe JC, Kozyraki R, Leheste JR, Jacobsen C, Nielsen MS, Verroust PJ, Aminoff M, de la Chapelle A, Moestrup SK, et al. Cubilin dysfunction causes abnormal metabolism of the steroid hormone 25(OH) vitamin D(3). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:13895–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willnow TE, Nykjaer A. Cellular uptake of steroid carrier proteins–mechanisms and implications. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010;316:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee YC, Kaufmann M, Kitazume-Kawaguchi S, Kono M, Takashima S, Kurosawa N, Liu H, Pircher H, Tsuji S. Molecular cloning and functional expression of two members of mouse NeuAcalpha2,3Galbeta1,3GalNAc GalNAcalpha2,6-sialyltransferase family, ST6GalNAc III and IV. J Biol Chem 1999;274:11958–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuchida A, Ogiso M, Nakamura Y, Kiso M, Furukawa K. Molecular cloning and expression of human ST6GalNAc III: restricted tissue distribution and substrate specificity. J Biochem 2005;138:237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gozdzik A, Zhu J, Wong BY, Fu L, Cole DE, Parra EJ. Association of vitamin D binding protein (VDBP) polymorphisms and serum 25(OH)D concentrations in a sample of young Canadian adults of different ancestry. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2011;127:405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borges CR, Jarvis JW, Oran PE, Nelson RW. Population studies of vitamin D binding protein microheterogeneity by mass spectrometry lead to characterization of its genotype-dependent O-glycosylation patterns. J Proteome Res 2008;7:4143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, Zonderman AB, Berg AH, Nalls M, Tamez H, Zhang D, Bhan I, Karumanchi SA, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1991–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.