Abstract

BACKGROUND

After treatment for prostate cancer, multidisciplinary sexual rehabilitation involving couples appears more promising than traditional urologic treatment for erectile dysfunction (ED). We conducted a randomized trial comparing traditional or internet-based sexual counseling with a waitlist control.

METHODS

Couples were adaptively randomized to a 3-month waitlist (WL), a 3-session face-to-face format (FF), or an internet-based format with email contact with the therapist (WEB1). A second internet-based group (WEB2) was added to further examine the relationship between web site usage and outcomes. At baseline, post-waitlist, post-treatment, and at 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups participants completed the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 to measure emotional distress, and the abbreviated Dyadic Adjustment Scale.

RESULTS

Outcomes did not change during the waitlist period. Of 115 couples entering the randomized trial and 71 entering the WEB2 group, 33% dropped out. However, a linear mixed model analysis including all participants confirmed improvements in IIEF scores that remained significant at 1-year follow-up (P<0.001). Women with abnormal FSFI scores initially also improved significantly (P=0.0255). Finding an effective medical treatment for ED and normal female sexual function at baseline, but not treatment format, were associated with better outcomes. In the WEB groups, only men completing more than 75% of the intervention had significant improvements in IIEF scores.

CONCLUSIONS

An internet-based sexual counseling program for couples is as effective as a brief, traditional sex therapy format in producing enduring improvements in men’s sexual outcomes after prostate cancer.

Keywords: erectile dysfunction, sexual counseling, prostate cancer, couples, internet

Despite the promise of nerve-sparing prostatectomy1 and innovations in radiation therapy, 2 surveys of diverse samples of prostate cancer survivors agree that only a minority are satisfied with their sexual rehabilitation outcomes. 4–8 Not only are rates of erectile dysfunction (ED) higher than estimates from more selected cohorts, 4,5,8 but medical treatments for ED after prostate cancer have had poor success rates and dismal adherence over time. 9–12 Men are far more likely to receive ED treatments after radical prostatectomy than after radiation therapy.3,9–11 In a population-based study of almost 39,000 prostate cancer survivors, only about 26% of men tried oral medication after radical prostatectomy and 11% after radiation therapy.3

Growing evidence suggests that “penile rehabilitation,” i.e. using medical therapies to promote penile blood flow several times a week, protects epithelial cells in the penis and prevents fibrosis in the cavernosal tissues, allowing a more complete recovery of erections after radical prostatectomy13 or maintaining erectile function after radiation.14 Adherence to penile rehabilitation is also poor, however, with the high cost of medication, unrealistic goals for recovery of erections, and female partners who have lost interest in sex cited as barriers.15,16 Partners are rarely included in ED treatment of prostate cancer survivors, although having a partner who enjoys sex is associated with seeking medical help for ED17 and with better sexual rehabilitation outcomes.9

Pilot studies suggested that combining medical management of ED with brief, sexual counseling could improve adherence and increase men’s satisfaction with urologic ED treatment in men unselected for health,18–20 and in prostate cancer survivors.21–23 In contrast, interventions for men with prostate cancer that focus on general coping and include limited material on sexuality have failed to improve sexual function in men with prostate cancer.24–28

We designed a 4-session pilot sexual counseling program for men treated for localized prostate cancer and their partners.29 Goals included enhancing both partners’ sexual satisfaction and helping them integrate effective treatments for ED into their sex lives. Eighty-four heterosexual couples were randomized to have sessions either with both partners present or with the man alone. However, the partner participated in behavioral homework and completed questionnaires in both groups. Fifty-one couples completed all 4 sessions (39% drop-out rate). Men’s usage of ED treatments increased significantly from 31% at baseline to 49% at 6-month follow-up. Total scores on the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)30 for men and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) for women31 improved significantly from baseline to post-treatment. Men’s distress levels decreased significantly (Brief Symptom Inventory-18, i.e. BSI-18).32 By 6-month follow-up however, these gains had regressed toward baseline values.

This report describes a randomized trial comparing face-to-face and internet-based versions of a revised and strengthened intervention, which we titled CAREss: Counseling About Regaining Erections and Sexual Satisfaction. We created an internet-based version because it would be convenient to disseminate and would take less therapist time. Not only do men routinely seek sexual content on the internet,33,34 but prostate cancer patients who desire information about the sexual impact of treatment view the internet as a preferred source.35 Our hypotheses were that the two formats of the intervention would have equal efficacy, and that outcomes would be superior to those after to a 3-month wait-list control condition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the UT MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) and yearly reports were submitted to the Data Monitoring Committee.

Eligibility and Recruitment

Couples were eligible if the male partner was heterosexual, aged 18 or older, and had been treated for localized prostate cancer (T1–3N0M0) with either definitive surgery or radiotherapy, between 3 months and 7 years previously. The couple needed to be married or living together for ≥ one year. Both partners agreed to participate in the assessments and intervention, and had reasonable English fluency. Men were either unable to achieve and maintain an erection sufficient for sexual intercourse on ≥ 50% of attempts in the past 3 months; or had not attempted intercourse for 3 months and also had not noted firm erections on waking from sleep. Men could not be using a satisfactory medical treatment for erectile dysfunction.

Couples were excluded if the man was currently using hormonal therapy for prostate cancer because of the profound impact on desire for sex. Couples entering the randomized trial had to be willing to come to UT MD Anderson Cancer Center three times during the 12-week treatment period.

Recruitment included mailing invitation letters to men in the UT MD Anderson tumor registry who met eligibility criteria. We also relied on physician referral, fliers placed in outpatient clinics, and public service announcements in local media or on web sites of prostate advocacy groups. Special efforts to recruit African-American couples included presentations at local churches, community health fairs, and announcements in newspapers and radio programs targeted to Houston’s African-American community. African-American couples interested in participating were screened and treated by an African-American psychologist.

Study Design

Couples were adaptively randomized to one of three groups using minimization.36 The following variables were used to assign participants, creating the best overall balance for each group: the man’s age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65), white non-Hispanic vs. any minority ethnicity, and radiation vs. surgery as primary therapy. The three arms were a 3-month waitlist group (WL), an immediate intervention group receiving 3 face-to-face sessions over 12 weeks (90 minutes for session 1 and 50–60 minutes for sessions 2 and 3) (FF), and an immediate intervention group using an internet format of the intervention with email contact with their therapist (WEB1). After the 3 months of the waitlist condition and completion of a post-waitlist assessment, WL participants were randomized a second time to one of the two intervention groups. During the course of the trial, we added a third intervention group (WEB2). Couples met all entry criteria except that they lived too far away to enter the randomized trial. They were invited to enter directly into the internet-based intervention. We included the WEB2 group in order to have enough power to examine the association between amount of web site usage and outcomes. In the analyses that follow, we clearly specify whether WEB2 data are included.

Outcome Measures

All participants were mailed assessment questionnaires baseline, after the 12-week treatment period, and at 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up. In addition the waitlist group completed questionnaires at the end of their 3-month waiting period. Primary outcome measures were the total score on the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF),30 a 15-item assessment of sexual function and satisfaction for men, and the total score on the FSFI (Female Sexual Function Inventory)31 a similar questionnaire for women. The BSI-1833 assessed current distress and an abbreviated form of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (A-DAS) 37 measured relationship satisfaction. In the WEB groups, the duration, number and content of visits were recorded electronically. A graphic on each participant’s home page displayed the percent of the intervention completed (pages visited or homework reports submitted).

Intervention: Content and Formats

The FF and WEB formats of CAREss included the same content and cognitive-behavioral homework. FF participants received printed handouts of materials from the web site, except for animations and videos. In the WEB groups, each partner had a unique username and password, and could not access the other’s responses. Homework exercises had standardized report forms completed on-line (WEB) or on paper (FF) and submitted by each partner. Therapists emailed feedback to the couple (WEB) or discussed homework in session (FF). If no homework reports were returned within two weeks of WEB entry, email and then phone reminders were given to one or both partners. WEB participants could also email their therapist at any time. Email to the therapist was programmed within the website, to maintain privacy. The web site was encrypted and maintained on a secure server, with access restricted to research participants and staff. Loaner laptops were provided for a few couples who did not have internet access at home.

On first visiting CAREss, each WEB partner completed an online questionnaire about their sex history, current practices, and beliefs about sexual function and cancer. This information was elicited by interview for FF couples. CAREss included exercises to increase expression of affection, improve sexual communication, increase comfort in initiating sexual activity, and facilitate resuming sex without performance anxiety (using a sensate focus framework). Suggestions were provided to treat postmenopausal vaginal atrophy or cope with male urinary incontinence. Gender-specific exercises helped participants identify negative beliefs about sexuality and use cognitive reframing. Treatments for ED after prostate cancer were described, with suggestions on their efficacy and using them optimally.

A decision aid for choosing an ED treatment asked each partner to rate the importance of seven characteristics (i.e. not interfering with spontaneity, naturalness, producing reliable and firm erections, having few side effects, not causing permanent physical harm, not requiring ongoing expenses and doctor visits, and not causing pain or discomfort). An algorithm generated a total score for each ED treatment (PDE5-inhibitors, penile injections, vacuum pump, intraurethral suppository, penile prosthesis surgery, or having sex without firm erections) based on a score of 1 to 3 on each dimension multiplied by a participant’s ratings on 10-point visual analogue scales. Each partner received a numerical ranking of the 3 treatments that best met their expectations. Partners were asked to share their results, choose a first-line treatment, and make a plan for how to begin. Relapse prevention exercises were included near the end of the intervention. Booster phone calls were made to both groups at 1 and 3 months to discuss progress with end-of-treatment goals and ways to overcome remaining barriers. A therapist manual was used to train the therapists, who also had biweekly group supervision.

RESULTS

Participants

Table 1 presents initial recruitment to each treatment group as well as attrition. During the 3-month waitlist period, 9% of couples dropped out. Remaining WL couples were randomized again to FF (N=20) and WEB1 groups (N=22). Thus 115 couples entered the randomized trial and 71 entered the WEB2 additional group. Recruitment was far more rapid for the WEB2 group, offering couples immediate entry into the internet-based intervention.

Table 1.

Attrition in the CAREss Trial

| Time of Attrition | Waitlist N=48 | FF N=60 | WEB1 N=55 | WEB2 N=71 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drop-outs during waitlist period* | 5/48=9% | -- | -- | -- |

| Drop-outs during intervention† | -- | 17/60=28% | 7/55=13% | 12/71=17% |

| Lost to Follow-Up‡ | -- | 3/43=7% | 7/48=17% | 16/59=27% |

| Total | 9% | 33% | 25% | 39% |

Drop-outs during 3-month waitlist period: Completed baseline questionnaires but not post-waitlist questionnaires and thus never began an intervention.

Drop-outs during intervention: Either did not complete all 3 sessions of face-to-face counseling, or both partners completed less than 25% of the internet intervention.

Lost-to Follow-Up: Couples completed an intervention but never completed any questionnaires afterwards.

A chi-square test indicated there were no statistically significant differences between the intervention groups in drop-out rate (p=0.44). Univariate logistic regression analyses indicated two significant associations with dropping out. Drop-outs were less likely if men had more positive baseline scores on the A-DAS (higher relationship satisfaction) (P=0.025). If the woman had a post-graduate degree, the couple was more likely to drop out (P=0.035). Although neither variable retained significance in a multivariate regression analysis, male baseline A-DAS and female education were controlled in other analyses of outcome to eliminate potential bias.

As Table 2 illustrates, the final groups were very similar in medical and demographic variables. Unmarried men all had a sexual partner. No significant differences were found between FF and WEB1. With the WEB2 group included, the FF group has a shorter duration of follow-up since cancer treatment than either WEB1 or WEB2.

Table 2.

Medical and Demographic Characteristics by Treatment Group

| Characteristic | FF (N=40) | WEB1 (N=41) | WEB2 (N=43) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| ▪ Less than High School | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| ▪ High School | 8% | 5% | 9% |

| ▪ Some College | 20% | 15% | 30% |

| ▪ 4-Year College Degree | 43% | 49% | 33% |

| ▪ Postgraduate Degree | 30% | 32% | 28% |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| ▪ Caucasian | 80% | 90% | 91% |

| ▪ African-American | 10% | 5% | 7% |

| ▪ Hispanic | 5% | 5% | 2% |

| ▪ Asian | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| ▪ Other | 0% | 0% | 0% |

|

| |||

| Relationship Status | |||

| ▪ Married | 95% | 100% | 95% |

| ▪ Separated/divorced | 0% | 0% | 2% |

| ▪ Widowed | 5% | 0% | 2% |

| ▪ Never married | 0% | 0% | 0% |

|

| |||

| Primary Prostate Cancer Treatment | |||

| ▪ Radical prostatectomy | 70% | 68% | 84% |

| ▪ Radiation therapy | 30% | 32% | 16% |

|

| |||

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 64 ± 8 | 64 ± 7 | 64 ± 8 |

|

| |||

| Years in Relationship (Mean ± SD) | 31 ± 14 | 35 ± 15 | 32 ± 14 |

|

| |||

| Months since Treatment (Mean± SD)* | 17 ± 14 | 25± 24 | 26 ± 14 |

P-level with all three groups included, 0.0128

Outcomes

None of the outcome measures changed significantly for men or women during the 3-month waiting list period, confirming that at a mean of 1.5 to 2 years post-treatment, sexual dysfunction is unlikely to resolve with time. Table 3 shows the means and SD’s for men’s IIEF total scores by intervention group across time. Repeated measurement analyses across time with random effects were conducted. Different covariance structures, the Akaike Information Criterion, and Schwartz’s Bayesian criterion were used to assess model fit. IIEF total scores improved significantly over time in all intervention groups. In the WEB2 group, IIEF scores were significantly higher at baseline than in the randomized trial groups (P <0.05). IIEF total scores can vary from 0 to 75. In a comparison of 111 men with ED and 109 age-matched controls (average age 55), the mean total IIEF for sexually functional men was 53.4 compared to 31.2 for men with ED.38 Although the present sample is 10 years older, men probably do not attain fully optimal sexual function at follow-up.

Table 3.

Mean IIEF Scores for Men across Time by Treatment Group

| Variable | Time | FF | WEB1 | WEB2 | Whole Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | ||

| IIEF | Baseline | 39 | 26.4 (18.2)* | 33 | 27.4 (17.3)† | 40 | 34.8 (17.3)‡ | 112 | 29.7 (17.9) |

| Post-TX | 30 | 34.4 (22.2) | 27 | 31.3 (20.4) | 33 | 41.7 (20.1) | 90 | 36.2 (21.2) | |

| 3-month | 29 | 35.4 (22.0) | 25 | 31.1 (23.2) | 28 | 45.5 (20.3) | 82 | 37.6 (22.4) | |

| 6-month | 26 | 37.0 (22.4) | 22 | 40.1 (23.5) | 30 | 40.0 (22.6) | 78 | 39.0 (22.5) | |

| 1-Year | 26 | 33.6 (23.1) | 25 | 34.5 (22.5) | 26 | 40.2 (22.0) | 77 | 36.2 (22.4) | |

IIEF score improved across time, P<0.0001

IIEF score improved across time, P=0.0040

IIEF score improved across time, P=0.0096

Many researchers have focused on the 6-item EF subscale of the IIEF, measuring the severity of erectile dysfunction. A score of 25 has been used as a cut-off for normal function, but in our work and others, a score of 22 or higher is associated with satisfaction with erections after prostate cancer.9,39 Table 4 presents the percentage of men in each treatment group who attained this criterion over time. Mantel-Haenszel Tests showed significant gains across groups between baseline and 6-month follow-up (P<0.0006) and baseline and 1-year follow-up (P<0.0046).

Table 4.

Percentage of Men Who Achieved Near-Normal Erectile Function across Time (EF Subscale of IIEF ≥ 22)

| Treatment Group | Baseline | 6-month | 1-year |

|---|---|---|---|

| FF | 12% | 36% | 32% |

| WEB1 | 15% | 38% | 31% |

| WEB2 | 21% | 44% | 41% |

| Total | 16% | 39% | 35% |

Neither marital happiness nor overall distress changed significantly across time for men in any subgroup or in the total sample. However, the sample was not distressed initially. The mean (SD) for dyadic adjustment was high at baseline 24.4 (4.7) (possible range 0–36) and remained at 24.6 (4.5) at 1-year follow-up. GSI scores on the BSI-18 were also low: 4.6 (6.2) at baseline and 4.6 (5.6) at 1-year follow-up. A raw score of 5 on the GSI is equivalent to a T-score of 50 in both oncology and community normative samples of men.

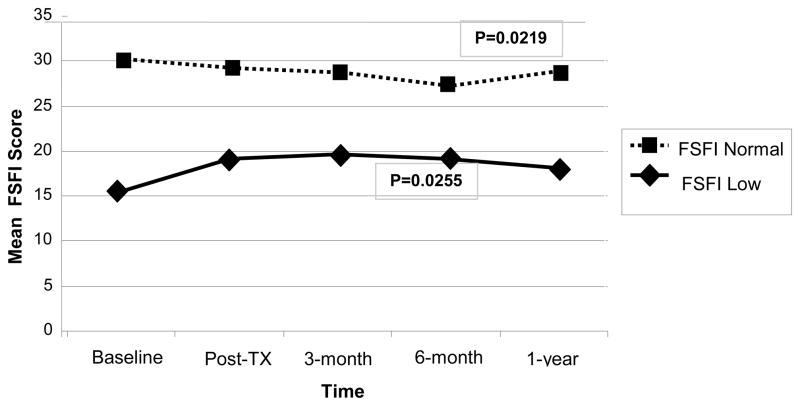

Sexual function/satisfaction (FSFI total score) did not improve significantly for women in any group. The mean (SD) for all women was 19.8 (9.9) at baseline and at 21.0 (10.6) at 1-year follow-up. A score below 26.55 indicates dysfunction, suggesting that at least half of women had sexual problems at 1-year follow-up.31 However, when women were divided into the 26% with normal FSFI scores at baseline vs. those with abnormal scores, women who initially had poor sexual function did have a statistically significant improvement over time (P=0.0255): (Figure 1). Scores declined slightly for women who were initially functional but recovered to baseline by one year (P=0.0219).

Figure 1.

The Impact of Initial FSFI Level on Changes in Women’s Sexual Function across Time

As with men, women’s dyadic adjustment was high and stable across time: mean (SD) 24.7 (5.0) at baseline and 24.7 (5.2) at 1-year follow-up. GSI scores also indicated good overall adjustment: 5.6 (7.4) at baseline and 4.1 (5.9) at one year. However, in the WEB2 group, women’s initial BSI-18 scores were significantly higher than in the FF or WEB1 groups, 7.6 (9.1), and tended to decrease over time, 4.4 (7.2) at one year, P = 0.064.

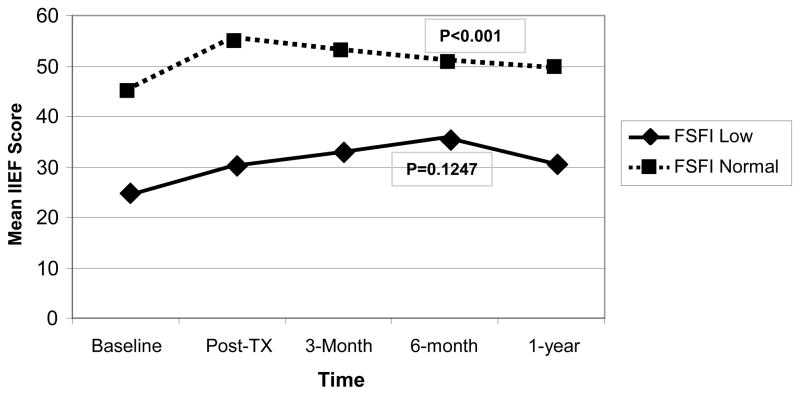

Women’s baseline sexual function also predicted the efficacy of CAREss in improving men’s IIEF scores. As Figure 2 illustrates, baseline IIEF scores were significantly higher when women had FSFI scores above the cutoff (P < 0.001). IIEF scores only improved significantly over time if the partner was sexually functional initially (P <0.001).

Figure 2.

The Impact of Baseline Female Sexual Dysfunction on Men’s Sexual Function over Time

Use of Medical Treatments for Erectile Dysfunction (ED)

At each assessment point, ED treatment usage was categorized as: 1) none; 2) using oral medication only; or 3) using invasive ED treatment (vacuum device, penile injections, penile suppositories, or penile prosthesis surgery), ± supplementary oral medication. Rates of ED treatment usage did not change significantly within any treatment group or for the entire sample. At baseline, 45% of men used no ED treatment, 23% used PDE5-inhibitors, and 32% used an invasive method. By one year, the corresponding rates were 46%, 20%, and 34%. However, at all assessment points, the men using ED treatment (oral or invasive) had significantly higher IIEF scores than those not using ED treatment (P<0.0001). At baseline, mean (SD) IIEF scores were 19.0 (13.1) for men not using an ED treatment, 36.2 (17.7) for men using pills, and 40.3 (15.8) for users of invasive treatments. The corresponding values at 1-year follow-up were 18.4 (16.1), 52.5 (15.5), and 50.0 (15.0). Scores at follow-up for men using ED treatments were similar to norms for healthy men.

Table 5 categorizes men’s usage of ED treatments at baseline and 1-year follow-up as follows: 1) No ED Treatment at either timepoint; 2) Stable Level of ED Treatment: Oral treatment at both timepoints, invasive treatment at both timepoints, or invasive at baseline and oral at one year; and 3) Intensified ED Treatment: None at baseline but oral or invasive at one year; or oral at baseline and invasive at one year. Men who intensified their treatment had large, significant gains in IIEF scores across time, and their partners also had significant improvement on the FSFI. The stable group had a smaller but still meaningful improvement in the IIEF scores but no change for female partners. Neither partner improved on average if men had not tried an ED treatment. Marital satisfaction and emotional distress were not significantly correlated with ED treatment usage.

Table 5.

Relationship of ED Treatment Usage to Changes in Mean (SD) IIEF and FSFI Scores across Time (N=83)

| Change Scores across Time | Change in Usage of ED Treatment from Baseline to 1-year Follow-Up | Overall P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None N=38 | Stable N=34 | Intensified N=11 | ||

| IIEF | 0.0 (8.9) | 8.4 (13.0) | 28.1 (17.8) | <0.0001 |

| FSFI | −0.8 (5.9) | −0.8 (6.3) | 7.6 (8.4) | 0.0072 |

Optimal Internet Usage and Outcome

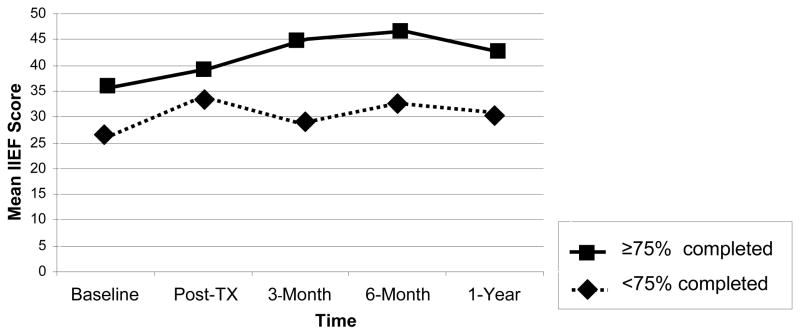

Since a Wilcoxon Test comparing web site usage by WEB1 and WEB2 groups did not reach significance, we combined the WEB groups in analysing the relationship between amount of web site usage and outcomes. We examined two measures of electronically-monitored website usage; number of visits to the website, and percent completion of the intervention. Both indices were significantly correlated within couples, with a range of coefficients from 0.4 to 0.5. However, women made significantly fewer visits than men (P < 0.0001) and tended to complete significantly less of the website (P < 0.0906). Fifty-two percent of men and 44% of completed > 75% of the web site. Figure 3 shows that men meeting this criterion had higher baseline IIEF scores, but also improved more over time. Using a mixed model with repeated measurement, the difference only reached significance for the WEB2 group (p=0.0427).

Figure 3.

Mean IIEF Scores across Time by Men’s Level of Web Site Completion (>75% vs. ≥75%)

Predictors of Good Sexual Outcome

Linear mixed model (LMM) analyses (proc mixed in SAS) including all couples entered into the study were performed to identify factors associated with improvement in sexual outcomes, defined as change across time in the IIEF total scores for men and FSFI total scores for women. LMM handles missing data by giving unbiased estimates of effects, provided that the covariates in the model account for the probability of missing data. In these models, factors associated in univariate analyses with dropping out were included as covariates. The significance of factors was almost identical whether the WEB1 and WEB2 groups were included separately or were combined.

Change in total IIEF score was significant across time (P<0.001). Treatment group was not a significant predictor, although there was a trend (P=0.083) for the WEB2 group to improve more. In the final multivariate analysis, men had more improvement in IIEF scores if their baseline marital satisfaction score was higher (P=0.001), the women’s initial FSFI score was higher (P<0.001), the female partner was younger (P=0.007), and the man was using a treatment for ED at 1-year follow-up (P<0.001).

The final multivariate analysis for FSFI scores at one year indicated that they decreased slightly, but significantly across time (P=0.043). Improvements in FSFI scores were associated, however, with higher female dyadic adjustment at baseline (P=0.015), not being menopausal (P=0.022), the partner having less than a college education (P=0.007), and a greater improvement in the partner’s IIEF score.

DISCUSSION

Traditional face-to-face sexual counseling and an internet-based format of the CAREss intervention program that depended on email for contact with the therapist produced equally significant gains in men’s sexual function and satisfaction. In contrast, none of the outcome measures changed during a 3-month waitlist period. Although there was a slight regression to the mean, improvements remained statistically significant one year after the intervention. The duration of improvements is promising, given the problems of nonadherence and dissatisfaction with ED treatment after prostate cancer.4–8 Men using ED treatments at one year have IIEF scores similar to those of healthy controls in normative samples. Compared to our pilot study,29 the drop-out rate was slightly less (39% vs. 33%) and the benefits were much more enduring.

Men experience a range of sexual problems after prostate cancer treatment, including low desire, difficulties reaching orgasm, and problems with painful sex.40,41 The IIEF total score assesses the full range of sexual function and satisfaction, suggesting that the intervention was broadly effective.30

Although partners did not have significant improvements in FSFI scores as a group, 26% had normal sexual function at baseline. Women who were dysfunctional initially did improve significantly. Womens’ change scores for sexual function/satisfaction were highly correlated with the men’s improvements. CAREss produced the largest gains when the male partner had discovered a successful ED treatment by the 1-year follow-up. As past research suggests, however,9,16,17 the woman’s interest in staying sexually active and satisfaction with the dyadic relationship are important prognostic factors for the success of sexual rehabilitation. CAREss may not be intense enough as an intervention if the woman in the couple has lost interest in sex or has marital dissatisfaction.

Men with less than a college education experienced greater improvements with CAREss. Perhaps they had less knowledge at baseline about cancer treatment and sexual function. In an Australian study, prostate cancer survivors with less education had more unmet sexuality needs.42 Low socioeconomic status is associated with ED in general even after adjusting for age, co-morbid diseases, health behaviors, and ethnicity.43

We were disappointed with our recruitment of African-American couples. African-American prostate cancer survivors report better sexual function than Caucasian men, yet they perceive themselves as more impaired, reporting more distress about sexual problems and more disappointment with their cancer treatment modality.44–47 African American men are likely to have serial relationships compared to men of other ethnicities.48 Even within committed relationships, African-American men are highly concerned about sexual function but women focus on survival from cancer.49 Recruiting African-American couples for psychosocial research on prostate cancer is difficult. Recently at Duke 40 couples entered a randomized trial of a psychoeducational program to improve quality of life.50 Only 12 couples in the experimental condition provided usable data. African-Americans are less likely to use online cancer support groups and are more comfortable getting support from same-ethnicity family and friends.51 A man-to-man peer counseling model, like one we used with African-American breast cancer survivors, may be appealing than the CAREss program.52

In general, however, we believe that an internet-based version of CAREss has the potential to be more cost-effective than traditional sex therapy. It took far less therapist time to respond to emails than to conduct traditional therapy sessions. Since private insurers rarely reimburse marital or sex therapy, an internet-based intervention could make treatment more affordable as well as accessible. Couples’ preferences can be deduced from the fact that recruitment was three times faster for those invited to enter directly into the internet-based condition, compared to recruiting for the randomized trial. A limitation of internet-based interventions, however, is high drop-out rates.53 Fewer than half of couples in the internet groups completed 75% or more of the program. Further empirical research is needed on methods to engage both partners in making behavioral changes.54

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant TURG-02-189-01-PBP (Schover, PI) from the American Cancer Society, National Office.

Footnotes

None of the authors have financial disclosures to make.

References

- 1.Walsh PC. The discovery of the cavernous nerves and development of nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2007;177:1632–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garzotto M, Fair WR. Historical perspective on prostate brachytherapy. J Endourol. 2000;14:315–318. doi: 10.1089/end.2000.14.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad MM, Prasad SM, Hevelone ND, et al. Utilization of pharmacotherapy for erectile dysfunction following treatment for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1062–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2002;95:1773–1785. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;73:1701–1705. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154637.38262.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnett AL, Aus G, Canby-Hagino ED, Cookson MS, et al. American Urological Association Prostate Cancer Guideline Update Panel. Erectile function outcome reporting after clinically localized prostate cancer treatment. J Urol. 2007;178:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulhall JP. Defining and reporting erectile function outcomes after radical prostatectomy: challenges and misconceptions. J Urol. 2009;181:462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker WR, Wang R, He C, Wood DP. Five year Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite-based quality of life outcomes after prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2010;107:585–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, et al. The use of treatments for erectile dysfunction among survivors of prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:2397–2407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller DC, Wei JT, Dunn RL, et al. Use of medications or devices for erectile dysfunction among long-term prostate cancer treatment survivors: Potential influence of sexual motivation and/or indifference. Urology. 2006;68:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergman J, Gore JL, Penson DF, Kwan L, Litwin MS. Erectile aid use by men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2009;182:649–654. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephenson RA, Mori M, Hsieh Y, et al. Treatment of erectile dysfunction following therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: Patient reported use and outcomes from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Urol. 2005;174:646–650. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165342.85300.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatzimouratidis K, Burnett AL, Hatzichristou D, McCullough AR, Montorsi F, Mulhall JP. Phosphodiesterase tye 5 inhibitors in postprostatectomy erectile dysfunction: A critical analysis of the basic science rationale and clinical application. Euro Urol. 2009;55:334–347. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pahlajani G, Raina R, Jones JS, et al. Early intervention with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors after prostate brachytherapy improves subsequent erectile function. BJU Int. 2010;106:1524–1527. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee DJ, Cheetham P, Badani KK. Penile rehabilitation protocol after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: assessment of compliance with phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy and effect on early potency. BJU Int. 2010;105:382–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moskovic DJ, Mohamed O, Sathyamoorthy K, et al. The female factor: Predicting compliance with a post-prostatectomy erectile preservation program. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3659–3665. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher WA, Eardley I, McCabe M, Sand M. Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a shared sexual concern of couples II: Association of female partner characteristics with male partner ED treatment seeking and phosphodiesterase Type 5 inhibitor utilization. J Sex Med. 6:3111–3124. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banner LL, Anderson RU. Integrated sildenafil and cognitive-behavior sex therapy for psychogenic erectile dysfunction: A pilot study. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1117–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruenwald I, Shenfeld O, Chen J, et al. Positive effect of counseling and dose adjustment in patients with erectile dysfunction who failed treatment with sildenafil. Eur Urol. 2006;50:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phelps JS, Jain A, Monga M. The PsychoedPlusMed approach to erectile dysfunction treatment: the impact of combining a psychoeducational intervention with sildenafil. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30:305–314. doi: 10.1080/00926230490463237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davison BJ, Elliott S, Ekland M, Griffin S, Wiens K. Development and evaluation of a prostate sexual rehabilitation clinic: a pilot project. BJU Int. 2005;96:1360–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Titta M, Tavolini IM, Dal Moro F, Cisternino A, Bassi P. Sexual counseling improved erectile rehabilitation after non-nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy or cystectomy—Results of a randomized, prospective study. J Sex Med. 2006;3:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bronner G, Shefi S, Raviv G. Sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: Treatment failure or treatment delay? J Sex Marital Ther. 2010;36:421–429. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2010.510777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, et al. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: Nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 2002;94:1854–1866. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS, Eton DT, Schulz R. Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: A randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol. 2003;22:443–452. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber BA, Roberts BL, Resnick M, et al. The effect of dyadic intervention on self-efficacy, social support, and depression for men with prostate cancer. Psycho-oncol. 2004;13:47–60. doi: 10.1002/pon.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, et al. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma: A randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer. 2005;104:752–762. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110:2809–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2689–2700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Gendrano N. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a state-of-the-science review. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:226–244. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Jacobsen, Curbow B, Piantadosi S, Hooker C, Owens A, Derogatis L. A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:241–246. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper A, Scherer CR, Boies SC, Gordon BL. Sexuality on the internet: From sexual exploration to pathological expression. Profess Psychol: Res and Prac. 1999;30:154–163. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spink A, Cenk Ozmutlu HC, Lorence DP. Web searching for sexual information: An exploratory study. Info Process Management. 2004;40:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davison BJ, Keyes M, Elliott S, Berkowitz J, Goldenberg SL. Preferences for sexual information resources in patients treated for early-stage prostate cancer with either radical prostatectomy or brachytherapy. BJU Int. 2004;93:965–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pocock SJ. Clinical trials: a practical approach. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharpley CF, Rogers HJ. Preliminary validation of the abbreviated Spanier Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Some psychometric data regarding a screening test of marital adjustment. Educ Psychol Measurement. 1984;44:1045–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dinsmore WW, Hodges M, Hargreaves C, Osterloh IH, Smith MD, Rosen RC. Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) in erectile dysfunction: near normalization in men with broad-spectrum erectile dysfunction compared with age-matched healthy control subjects. Urology. 1999;53:800–805. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briganti A, Galina A, Suardi N, et al. What is the definition of a satisfactory erectile function after bilateral nerve sparing radical prostatectomy? J Sex Med. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02179.x. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnas JL, Pierpaoli S, Ladd P, et al. The prevalence and nature of orgasmic dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2004;94:603–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le JD, Cooperberg MR, Sadetsky N, et al. the CaPSURE Investigators. Change in specific domains of sexual function and sexual bother after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2010;106:1022–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith DP, Supramaniam R, King MT, Ward J, Berry M, Armstrong BK. Age, health, and education determine supportive care needs of men younger than 70 years with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2560–2566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kupelian V, Link CL, Rosen RC, McKinlay J. Socioeconomic status, not race/ethnicity, contributes to variation in the prevalence of erectile dysfunction: Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1325–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanda M, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson TK, Gilliland FD, Hoffman RM, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in functional outcomes in the 5 years after diagnosis of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4193–4201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knight SJ, Siston AK, Chmiel JS, et al. Ethnic variation in localized prostate cancer: a pilot study of preferences, optimism, and quality of life among black and white veterans. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;3:31–37. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2004.n.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jenkins R, Schover LR, Fouladi RT, et al. Sexuality and health-related quality of life after prostate cancer in African-American and White men treated for localized disease. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30:79–93. doi: 10.1080/00926230490258884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Romantic Relationships among unmarried African Americans and Caribbean blacks: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Fam Relat. 2008;57:254–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rivers BM, August EM, Gwede CK, et al. Psychosocial issues related to sexual functioning among African-American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses. Psycho-Oncol. 2011;20:106–110. doi: 10.1002/pon.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell SLC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners: A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):414–424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fogel J, Ribisi KM, Morgan PD, Humphreys K, Lyons EJ. The underrepresentation of African Americans in online cancer support groups. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:705–712. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schover LR, Jenkins R, Sui D, Adams JH, Marion MS, Jackson KE. A randomized trial of peer counseling on reproductive health in African-American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1620–1626. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lustria ML, Cortese J, Noar SM, Glueckauf RL. Computer-tailored health interventions delivered over the Web: review and analysis of key components. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:156–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]