Abstract

The spatial and spectral responses of the plasmonic fields induced in the gap of 3-D Nanoshell Dimers of gold and silver are comprehensively investigated and compared via theory and simulation, using the Multipole Expansion (ME) and the Finite Element Method (FEM) in COMSOL, respectively. The E-field in the dimer gap was evaluated and compared as a function of shell thickness, inter-particle distance, and size. The E-field increased with decreasing shell thickness, decreasing interparticle distance, and increasing size, with the error between the two methods ranging from 1 to 10%, depending on the specific combination of these three variables. This error increases several fold with increasing dimer size, as the quasi-static approximation breaks down. A consistent overestimation of the plasmon’s FWHM and red-shifting of the plasmon peak occurs with FEM, relative to ME, and it increases with decreasing shell thickness and inter-particle distance. The size-effect that arises from surface scattering of electrons is addressed and shown to be especially prominent for thin shells, for which significant damping, broadening and shifting of the plasmon band is observed; the size-effect also affects large nanoshell dimers, depending on their relative shell thickness, but to a lesser extent. This study demonstrates that COMSOL is a promising simulation environment to quantitatively investigate nanoscale electromagnetics for the modeling and designing of Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) substrates.

Keywords: Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS), Plasmonics, Nanoshell, Dimer, Multipole Expansion, Finite Element Method, Gold, Silver

The field of plasmonics, more specifically nanoparticle surface plasmons, has experienced a recent surge in interest following the discovery that surface plasmons are responsible for enhancements of the local E-field in the vicinity of metallic, nanostructured surfaces. Such enormous enhancements, up to 1014,1 have enabled Raman scattering, an intrinsically weak scattering phenomenon, to become an important detection methodology that provides narrow spectral resolution, wealth of molecular information and potential sensitivity for single molecular detection;2,3 this is known as the field of Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS).

Plasmon resonances arise within a metallic nanoparticle from the collective oscillation of free electrons driven by an incident optical field. The plasmonic response of nanoparticles have played a role in a growing number of applications, including SERS, chemical sensing, drug delivery, photothermal cancer therapy and new photonic devices. Our laboratory has been involved in the investigation and application of plasmonics nanosubstrates for SERS detection for over two decades. Since our first report on the practical analytical use of the SERS techniques for the trace analysis of a variety of chemicals including several homocyclic and heterocyclic polyaromatic compounds in 1984,4 our laboratory has been involved in the development of SERS technologies for applications in chemical sensing, biological analysis and medical diagnostics.5–11

The wealth of experimental protocols and data in the literature for synthesizing SERS substrates, both via wet chemistry10,12–15 or on fixed substrates,16–18 necessitates numerical methods that confidently solve nanoscale electromagnetics of 3-D geometries with high spatial and spectral resolution; this is essential for understanding the fundamentals of the already available SERS substrates, as well as for further exploring and optimizing future substrate designs.

The Mie theory provides the exact analytical description of the behavior of the E-field surrounding isolated spherical nanoparticles, but is unfortunately strictly limited to the spherical geometry. It cannot be employed to solve more interesting and realistic problem, consisting of irregularly-shaped structures that are arbitrarily positioned in space. The analysis of such geometries require numerical methods to solve Maxwell’s equation in the computational domain via iterative procedures. The literature details two important computational electrodynamics modeling techniques to this end: the Finite Difference Time Domain (FDTD) and the Finite Element Method (FEM). Due to the nature of its discretizing algorithm, however, FDTD possesses intrinsic limitations for solving the electromagnetics problem at boundaries.19–21 A recent report20 evaluating FDTD as a method for solving the electromagnetic fields around metallic dimer nanoparticles demonstrated only a fair ability to do so, conveying large inconsistencies in field amplitude and plasmon peak position. This would suggest FEM as a more suitable approach when near-field optics are of interest.

COMSOL Multiphysics is numerical simulation package based on FEM that allows accurate resolving of nanoscale electromagnetics in the vicinity of irregular nanostructures. Its accuracy relative to analytical theory is therefore of utmost importance for accurate characterization and design of such geometries. COMSOL has recently been used by several groups for modeling the plasmonics of nanoshells,22–24 as well as other nanoscale geometries,25–27 but these groups have focused exclusively on 2-D geometries. Ehrhold et al.28 only briefly discussed the use of COMSOL for modeling the plasmonic properties of 3-D bimetallic nanoshells. The lack of 3-D modeling in COMSOL is a result of the significant time and computational power required to solve even a trivial problem in 3-D space. Nevertheless, there is significant discrepancy between 2-D and 3-D solutions, so much so that 2-D models are unable to reconcile experimental observation and numerical analysis.

This report comprehensively investigates the behavior of the fields around gold and silver nanoshell dimers in 3-D space, solved using the Multipole Expansion and using FEM within COMSOL. Clusters of nanoparticles under optical illumination have become the subject of recent analytical studies because of the potentially large field enhancements between the particles arising from surface plasmon resonances. Spherical dimers composed of pairs of solid nanospheres as well as linear chains of nanospheres have been analytically derived by several researchers.29,30 The nanoshell dimer, however, represents a more versatile geometry that exhibits stronger field enhancements in its gap, relative to an isolated nanoshell, while boasting plasmon tuning capabilities by variations in shell thickness; both properties are important criteria of a good SERS substrate. Nanoshell dimers have recently been investigated both theoretically, using the plasmon hybridization method,31 and numerically, by employing the FDTD method.21 The plasmon hybridization method expresses the nanoshell dimer plasmon as a linear combination of the primitive plasmons, associated with the individual nanoshells, that electromagnetically interact and effectively ’hybridize’. The second report used the FDTD method to analyze the optical properties of silver nanoshell dimers, and unraveled the FDTD as being prone to inherent numerical staircasing errors when attempting to map a curved surface on a Cartesian grid. Considering that the synthesis and intricate control of the nanoshell dimer configuration has already been achieved,32 it is of interest to identify other promising analytical and numerical methods that are able to accurately model this geometry. This paper extends Norton el al.’s ME analysis of a solid dimer30 to a nanoshell dimer, and complements the two aforementioned reports by comparing the spatial and spectral responses of the E-field between ME and FEM as a function of dimer size, shell thickness and inter-particle separation. The paper concludes with a final section that discusses the effects brought about by the incorporation of the size-effect factor in the dielectric function, which arises when the particle size becomes comparable to the electron scattering mean-free path length. To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first study that comprehensively benchmarks COMSOL’s numerical algorithm based on FEM to the ME analytical method for solving a 3-D nanoshell dimer geometry, providing relative errors between the two for a number of important plasmon resonance band variables as a function of geometry.

Results and Discussion

The versatility of gold and silver nanoshells for use in plasmonics originates from the fact that their plasmon resonance peaks can be controllably tuned throughout the visible region by adjusting the ratio of core to shell radii.33 The dimer configuration results in plasmon coupling between the two nanoparticles, effectively concentrating the local E-field relative to that induced by a single nanoparticle, or monomer. The tunability of dimers is expected to follow a similar trend as for monomers, with possible differences stemming from additional plasmonic coupling behavior due to the particles’ close proximity.

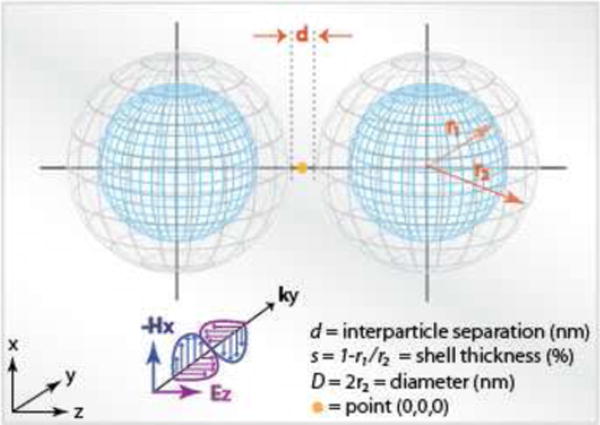

From a simulation perspective, the nanoshell dimer provides several degrees of freedom to test COMSOL’s ability to mesh and solve at nanoscale resolutions: shell thickness s = 1 − r1/r2 in %, inter-particle separation d in nm and particle diameter D = 2r2 in nm. These are depicted in schematic of the 3-D nanoshell dimer model employed throughout the study, Figure 1. For conciseness, unique geometry combinations that define the nanoshell dimer geometry are represented using the “ND[D,d,s]” format, such that “ND[20nm,5nm,∆s]” indicates the study of a Nanoshell Dimer of diameter D = 20nm and inter-particle separation d = 5nm as a function of shell-thickness s. Due to the polarization selectivity of the plasmon excitation, the incident source was polarized with the electric field parallel to the bisphere axis, which effectively excites the dominant ‘longitudinal’ plasmon of the system. This is the optimal polarization for creating the largest field enhancement in the gap between the particles. As such, the incident source was represented by a normalized z-polarized TM wave, propagating in the x-direction.

Figure 1.

3-D Nanoshell Dimer schematic

Although the corresponding SERS enhancement would be approximately proportional to ,34 the E-field magnitude |Ez| is employed in this report for visualization purposes. Since the incident wavelength was set such that |Ez|inc = 1, the computed |Ez| is in fact representative of E-field enhancement: Enhancement = |Ez|/|Ez|inc = |Ez|. In this report, we are particularly interested in computing the maximum E-field enhancement in the gap between the two nanoshells, at point (0,0,0). Throughout the remainder of the report, the variation of |Ez| as a function of wavelength will be represented by the function FE(λ).

The gold and silver dielectric functions were modeled using the Lorentz-Drude dispersion model:35

| (1) |

where ∆εk, ak, bk and ck are constants that provide the best fit for either metal.35 The refractive index of the silica comprising the core of each particle was taken as 1.45 and assumed to be wavelength independent36.37 The surrounding medium was defined as air.

The ME employed in our study is based on the quasi-static approximation for which the particles are assumed much smaller than an optical wavelength, such that the incident electric field may be assumed uniform over the dimensions of the particle. The basic approach can be extended to the full-wave problem in which retardation affects are accounted for. The reduced complexity of the quasi-static approximation greatly simplifies the solution to the nanoshell dimer geometry, compared to that involving a full expansion of the Mie scattering coefficients, while boasting a similar accuracy for small nanoparticles. This size limitation is been claimed to be ∼ λ/20,38 beyond which the approximation progressively breaks down and the ME loses validity. In treating a dimer or cluster of spheres, the ME method is sometimes called the superposition method39 since the scattered field can be expressed as a superposition of the field scattered from each particle in the cluster. An advantage of this approach is that its accuracy can be easily evaluated by checking the convergence of the multipole expansion, undertaken by adding additional higher order terms until convergence is evident. The ME method can be very accurate and is often used as a benchmark against which other algorithms may be evaluated39 and its derivation is detailed in the Supporting Information.

COMSOL Multiphysics is a FEM-based numerical simulation package, which interfaces with MatLab and provides a number of modules for physics and engineering applications. The RF-module was employed to characterize the electromagnetic fields in the computation domain comprising the nanoshell dimer. The Maxwell’s equations are simplified according to the selected application mode, which in this case is TM incidence, and are encompassed in a system of matrices. For 2-D geometries with a small number of Degrees of Freedom (DoF), a direct solver is able to solve the inverse problem, but for 3-D problems, an iterative solver iterates through the system until convergence is reached.

Accuracy of ME relative to Mie Theory

The exact Mie theory solution for an isolated sphere is represented as an expansion of coefficients of the form (a/λ)2n+1 with alternating sign, which converges very rapidly when a ≪ λ where a is the particle radius. Thus, the first term in the Mie expansion is proportional to (a/λ)3 and the second term to (a/λ)5. The magnitude of the first two terms are given by40

| (2) |

| (3) |

The ratio of these terms is

| (4) |

The quasi-static approximation retains only a1, such that the resonance plasmon peak is predicted to occur a frequency determined by the condition Re{ε(ω) + 2ε0} = 0.

As an illustration, the value of the ratio (4) using the Lorentz-Drude dispersion model (1) is computed. Using the parameters for silver, the quasi-static approximation predicts a resonance peak at a wavelength of 370nm. Evaluating Eq. (4) at this wavelength and for a particle radius of 10nm results in a ratio of 0.001. For a solid sphere, the quasi-static approximation is equivalent to assuming a spatially uniform incident electric field (i.e., the limit as λ → ∞), in which case the external field is equivalent to that of a dipole residing at the sphere’s center. The second term, given by Eq. (3), corresponds to a quadrupole response and is maximum when the real part of the denominator of Eq. (3) vanishes. This defines a quadrupole resonance and at this wavelength one might expect that the quasi-static approximation would fare poorly. However, using the above parameters for silver and evaluating Eq. (4) at the wavelength of the quadrupole resonance (λ = 357nm), the ratio evaluates to 0.002, which is still very small. It is also worth noting that the second term in an infinite series with alternating sign, such as the Mie series, provides an upper bound to the error that results from dropping all terms in the series except the first. The above example for a solid sphere illustrates the dominance of the first term of the Mie series for small particles and may be regarded as providing further support for the validity of the quasi-static approximation under these conditions. Although the above results hold for an isolated spherical particle, similar arguments should hold for more complex objects, such as dimers.

The small divergence between the solutions of the ME and the Mie Theory for 20nm nanoparticles suggest that this diameter small enough for the quasi-static approximation to hold; it is therefore employed as the nominal size for comparisons between ME and COMSOL.

Analysis of the E-Field as a Function of Wavelength

Effect of Shell Thickness, ∆s

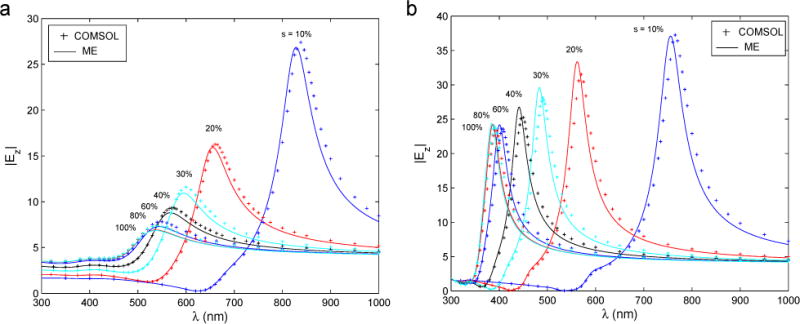

The plasmon resonance tunability was investigated for 20nm nanoshell dimers of gold and silver, by varying the shell thickness s while keeping the inter-particle distance fixed at 5nm (or 25% of the particle diameter) and evaluating |Ez| at the origin (0,0,0) for the wavelength range 300 – 1000nm. This separation was chosen to test COMSOL’s ability to spatially resolve a narrow gap in a medium with a real, positive dielectric constant (free space), while varying the adjacent subdomains (shells) that are modeled by a complex dielectric function with a negative real part. The computed FE(λ) are plotted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

FE(λ) v.s. shell thickness s for ND[20nm,5nm,∆s] of (a) Au (b) Ag

The figures clearly depict a red-shifting of the resonance bands, as well as an increase in |Ez| in the gap, with decreasing shell thickness; both trends become more pronounced in the limit of the shell thickness tending to zero. Interestingly, there exists a wide dynamic range in FE(λ), from ∼ 7 to a maximum of ∼ 27 for gold but only from ∼ 24 to ∼ 37 in the case of silver, implying that a gold nanoshell has a greater impact on improving potential E-field enhancement than for silver. It should also be noted that the FE(λ) curves for gold are generally broader than for silver, for all shell thicknesses.

The COMSOL-generated FE(λ) curves are very slightly offset compared to the ME results, but the correlation between the two methods is qualitatively and quantitatively sound. With regards to the magnitude differences, both methods produce FE(λ) that are nicely superimposed on both sides of the resonance band where the error stabilizes around zero, for both silver and gold, and the greatest differences occur close to the resonance peaks. A possible explanation is that, as a result of the resonance phenomenon, the surface plasmons that are excited around the dimer’s inner and outer surfaces in this wavelength range expose and amplify any differences between the two methods.

Effect of Dimer Separation, ∆d

The effect of the dimer separation on the error between the two methods was investigated by fixing D and s, and solving for |Ez| as a function of separation distance d, Figure 3. The separations were decreased from d = D = 20nm (100% of particle diameter), deemed as sufficiently far, down to d = 1nm, which, even though possibly too small to realistically synthesize, was interesting from a meshing point of view. It should be noted that ∼ 4 mesh elements were fitted along the z-axis in the 1nm gap to ensure an adequate spatial sampling of the inter-particle space. This represents a spatial resolution of ∼ 0.25nm and is the highest resolution necessary throughout this study.

Figure 3.

FE(λ) v.s. dimer separation d for ND[20nm,∆d,20%] of (a) Au (b) Ag

As the dimer separation increases, the FE(λ) resonance bands of both gold and silver blueshift, tending towards the peak position of an isolated nanoshell as plasmon coupling between the dimers tends to zero. As a result of this reduced coupling with increasing separation, the |Ez| magnitudes are also affected and dramatically decrease, requiring the FE(λ) curves to be plotted with a logarithmic y-axis for visualization purposes. The insets represent the original unscaled curves, for reference. Once again, COMSOL generates FE(λ) curves that very closely resemble those of the ME, in that they superimpose about the resonance band, have a closely correlated |Ez| values and are consistently red-shifted by a few nanometers.

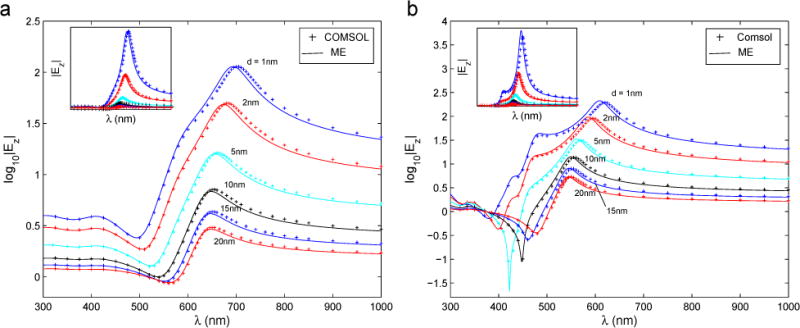

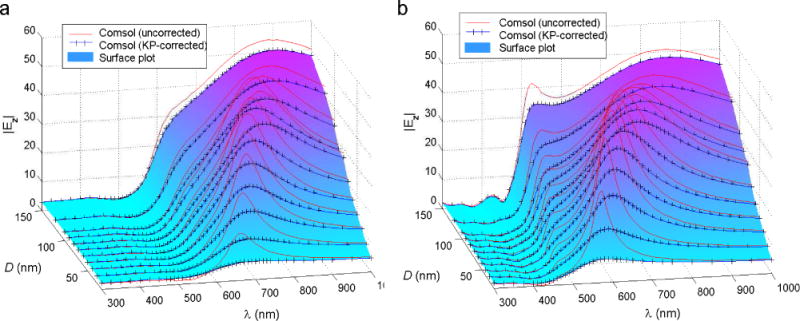

Effect of Dimer Size, ∆D

The following test was performed to investigate the reliability of COMSOL to mesh the space, and solve the electromagnetics problem, in a narrow gap that is surrounded by two increasingly large objects. The dimers were increased from D = 20nm to D = 150nm, representing an experimentally relevant range of sizes, while keeping d = 5nm and s = 20%, Figure 4. The 3-D surface plots, generated by postprocessing in MatLab via a 2-D spline interpolation, highlight the progression of the FE(λ) resonance bands with increasing size. The divergence of the shape and position of FE(λ) between COMSOL and ME is obvious, with COMSOL producing a red-shift over approximately a few hundred nanometers for both gold and silver in the former case, compared to about 50nm for the two metals in the ME case. The rapidly increasing FE(λ)ME diverges from FE(λ)COMSOL, which appears to plateau at ∼ 50 for dimer sizes. The ME seems unable to properly solve for dimer nanoshells that start exceeding 20nm, for which the quasi-static approximation appears to break down, due to the increasing influence of phase retardation effects.

Figure 4.

FE(λ) v.s. nanoshell diameter D for ND[∆D,5nm,20%] of (a) Au (b) Ag

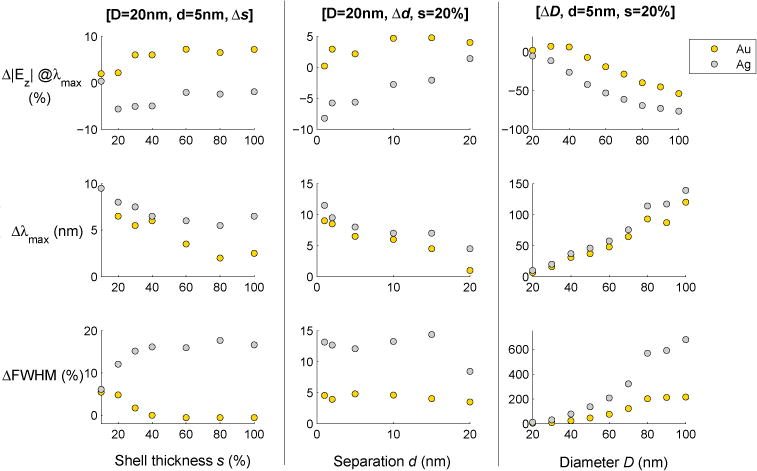

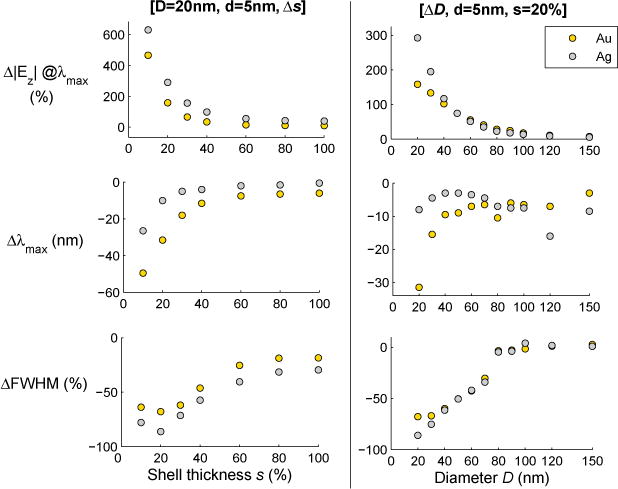

A quantitative comparison between COMSOL and ME for each explored dimer scenario is concisely summarized in Figure 5, which focuses on the error between 3 variables associated with the plasmon peak: |Ez| relative error, ∆|Ez|, resonance λmax shift, ∆λpeak, and FWHM relative error, ∆FWHM. These properties help characterize the plasmon resonance band and are usually the features of greatest importance when developing and tuning nanostructures. The first, second and third column convey scenarios ND[20nm,5nm,∆s], ND[20nm,∆d,20%] and ND[∆D,5nm,20%], respectively In each case, the errors were computed by evaluating |Ez|COMSOL, FWHMCOMSOL and λmax–COMSOLrelative to |Ez|ME, FWHMME and λmax–ME, respectively,

As such, positive values indicate an overestimation by COMSOL and negative values suggest underestimation.

Figure 5.

Matrix of Error plots between COMSOL and ME for 3 scenarios of interest: ND[20nm,5nm,∆s], ND[20nm,∆d,20%] and ND[∆D,5nm,20%]. Error computed as ∆var = varCOMSOL – varME, where var represents variables |Ez|, ∆λmax or FWHM

The shell-thickness analysis is dealt with in the first column, which depicts a fairly stable, slightly-increasing ∆|Ez| with increasing shell thickness, with ∆|Ez| averaging approximately 5% in the range (2%,6%) for gold, and 4% in the range (0.5%,–6%) for silver. It is interesting to note that |Ez| is overestimated for gold but underestimated for silver. The λmax position is overestimated for both metals and decreases with increasing shell thickness in both cases, ∆λpeak ranging (2%,7%) and (6%,9%) for gold and silver, respectively. The third graph of ∆FWHM as a function of shell thickness conveys that gold starts with a ~ 6% error for the smallest shell thickness, and decreases to stabilize around zero, implying that as the nanoshell core shrinks, the plasmon bands become more similar. Interestingly, the opposite occurs for silver, with ∆FWHM starting around ~ 7% and stabilizing close to 16%. It is crucial to remark, however, that this is a relative error, and considering the the narrow widths of the thick-shelled silver dimers (Figure 2), such a high percentage only maps to ∆FWHM of only a few nanometers.

The second column of Figure 5 details this quantitative error analysis as a function of separation distance. Again, a fairly stable, slightly-increasing ∆|Ez| with increasing separation is seen for gold, with an average ∼ 4% in the range (0%,5%), whereas silver starts underestimated around −8% and increases to an overshoot of 2%. Both gold and silver follow a decreasing trend in ∆λpeak with increasing separation, suggesting that accuracy improves as the particles become more isolated from each other. The last graph of the column conveys a stable, overestimated ∆FWHM for both metals, averaging 5% and 12% for gold and silver, respectively. This last result suggests that the plasmon FWHMCOMSOL is not critically affected by coupling between the two particles as the software is able to solve the geometries with a consistent offset from its analytical counterpart.

The third column of Figure 5 demonstrates the diverging behavior of the error variables between both methods, with increasing dimer size. In this case, however, the COMSOL results are used as the trusted baseline against which the ME is compared. In that regard, the ME increasingly overshoots ∆|Ez| for both metals (except for gold dimers D < 50nm), and differences in λmax and FWHM become more prominent as the dimers grow, really emphasizing the ME as suitably accurate for nanoshell dimer sizes D ≤ 20nm.

The discrepancy between an overestimated |Ez| for gold but underestimated |Ez| for silver, as observed across the first row of Figure 5, is intriguing since both silver and gold dimers were solved with identical meshing that yielded sufficiently converged solutions in both cases; further mesh refinement did not improve the obtained results. This effectively disqualifies meshing inconsistencies as the potential source of the observed difference. Interestingly, the discrepancy appears to be consistent across dimer geometry, ND[D,d,s], and is therefore most probably material-specific in nature, arising from differences in the metal dielectric functions. The plasmon resonance peaks of gold and silver, at which |Ez| is measured in each case, are effectively dictated by their corresponding dielectric function and occur at different wavelengths in the optical spectrum; this difference in resonance position could ostensibly affect the accuracy with which the fields in the vicinity of the dimer are solved by Comsol’s FEM algorithm. This would then result in over-, or under-, estimation. Although further investigation into this phenomenon is beyond the scope of this manuscript, it is noteworthy that as long as the overshoot in either direction is consistent and small, as demonstrated here, Comsol’s FEM algorithm can still be trusted to generate reliable solutions.

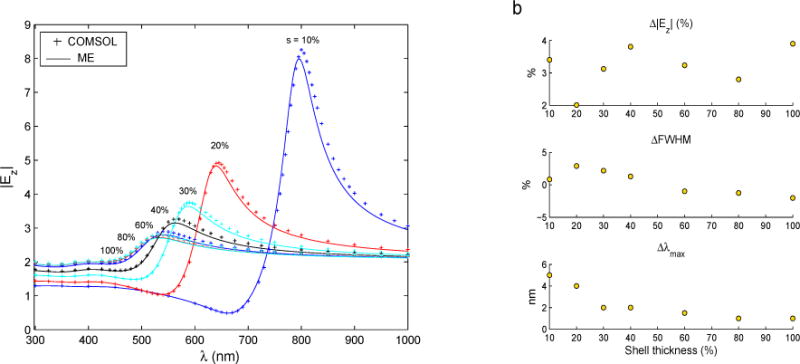

The interesting λpeak offsets of the FE(λ) curves seen in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 between ME and COMSOL was further investigated by comparing the local E-field around a single nanoshell (monomer), to categorize it as a possible discrepancy introduced by the dimer configuration or an intrinsic difference related to the fundamental algorithms of each model. The E-field for the nanoshell monomer geometry was probed at a distance of 2.5nm from the shell surface, effectively co-registering with the interrogation point in the dimer case. In the monomer case, Figure 6(a), the two methods generated FE(λ) curves that are in good agreement with each other, yet an evident offset in resonance peak position and E-field magnitude is still present. The relative error between COMSOL and ME is presented in Figure 6(b).

Figure 6.

Analysis of 20nm Au Nanoshell Monomer v.s. shell thickness s, interrogated at 2.5nm from shell surface (a) FE(λ) (b) Relative Error between ME and COMSOL

Very briefly, ∆|Ez| and ∆FWHM do not display obvious trends, the former roaming around ∼ 3% and the latter in the range ∼ (2%, 3%). The shift in λmax, however, decreases with increasing shell thickness and stabilizes around 1nm in the limit s → r2. This analysis suggests that the observed FE(λ) offset potentially arises from algorithm-related, rather than dimer geometry-related, differences.

Analysis of the E-Field as a Function of Spatial Coordinate

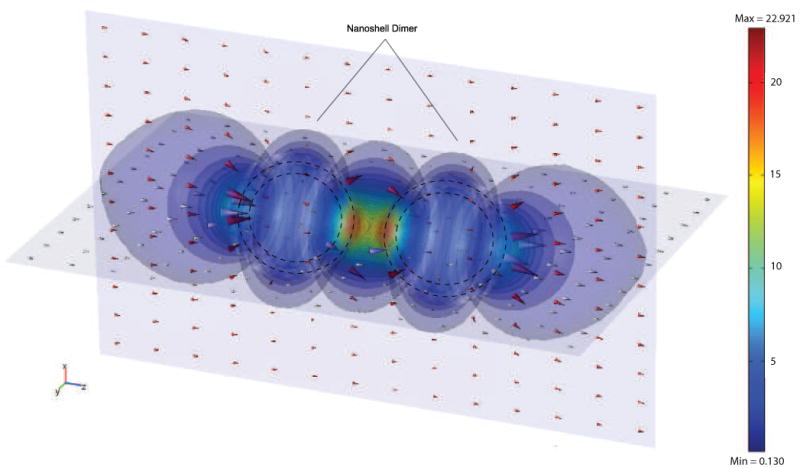

For each selected wavelength, COMSOL solves the electromagnetic problem at every mesh node in 3-D space, which, although computationally intensive, enables 3-D spatial maps of the desired variable to be assembled and conveniently visualized. One such map for ND [20nm, 5nm, 20%] @ λpeak = 660nm is shown in Figure 7. The core and shell boundaries of the nanoshell dimer are delimited with dashed-lines on either side of the separating junction. The 3-D surface contours represent isosurfaces of constant |Ez|, and the red and white arrows indicate the direction of the vector Ez on the x–z and y–z planes, respectively, and are proportional to the E-field strength at their position in 3-D space. This map depicts the concentrating and propagating behavior of the E-field in the vicinity of the dimers, as well as its rate of change away from the same. It is noteworthy that the arrows passing through the gap in between the two nanoshells are purposefully withheld for better visual clarity; they would point from the left nanoshell to the right nanoshell.

Figure 7.

3-D illustration of E-field behavior surrounding Gold Dimer ND[20nm,5nm,20%]@λpeak = 660nm

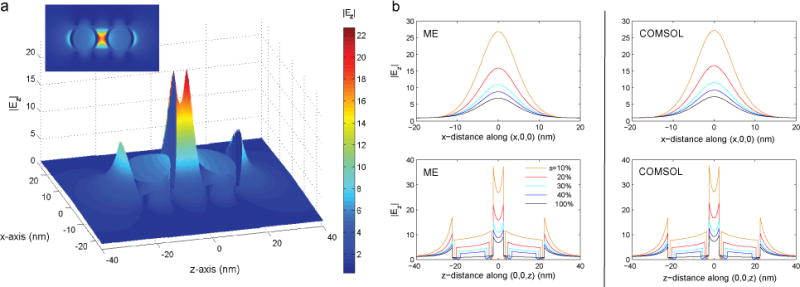

For any method lacking a closed-form solution, spatial resolution is a critical measure and is dictated by the extent to which space is discretized into meshes for numerical solving. Figure 8(a) shows the corresponding x – z slice plot, with |Ez| represented as the third dimension, and effectively conveys COMSOL’s ability to smoothly mesh and solve the E-field around 3-D geometrical edges that bound domains of differing dielectric functions. This plot also conveys that the maximum |Ez| occurs at the metal/air interface, on either side of the gap, along the z-axis. The spatial resolution was investigated for ND[D = 20nm,s = 5nm] as a function of the shell thickness, evaluated at their corresponding plasmon peak wavelength, Figure 8(b). The excellent agreement between the line profiles confirms that the 3-D meshing was dense enough, for all shell thicknesses, to effectively capture the features of interest, especially the abrupt E-field discontinuity at the dielectric boundaries. Unlike FDTD, which exhibits large errors at the nanoshell’s interior or exterior boundaries, 19,20 FEM allows for a more versatile meshing algorithm that employs tetrahedrons to effectively discretize the shell’s curved surface, such that the shell geometry is accurately maintained and solved for.

Figure 8.

Spatial plots for Au ND[20nm,5nm,20%]: (a) Slice plot along x–z plane, represented in 3-D with |Ez| as the third dimension. Inset is 2-D slice plot for reference. (b) Spatial resolution comparison of x- and z-line plots as a function of shell thickness s.

Computational requirements

For completeness, it is appropriate to briefly discuss computational power and time differences between the two methods, as well as between COMSOL models solved in 2-D and 3-D space. This is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Computational comparison

| ME | COMSOL 2-D | COMSOL 3-D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| time | < 1 min | 5 – 10 min | 12 – 24 hours |

| RAM (Gb) | < 1 | ∼ 1 | 4 – 15 |

The results convey a huge range of times and powers that originates mostly from differences in the intrinsic problem-solving algorithms.

Several properties of the ME algorithm in this geometry resulted in exceptionally fast execution. In a calculation with many frequencies, the frequency-independent matrix elements computed only once. For each frequency, the linear system of equations are then solved for the ME coefficients, which takes little time since the system is relatively small. This system comprises 2N equations, where N is the number of multipole terms. In our calculations, we used N = 20 for all but the smallest dimer gaps; in the latter case N was increased to 40. The relatively small number of terms in the multipole expansion is a direct result of the axial symmetry of the problem. Incrementing through 400 frequencies, the entire calculation in MatLab took typically less than a minute.

The generation of 3-D plots using COMSOL, however, are significantly more challenging. The extreme RAM loads for 3-D geometries in COMSOL are strongly dependent on the required meshing density for the particular geometry. The computational time, however, is affected not only by the meshing density, but also more critically by the number of desired wavelength iterations; the sampling resolution of FE(λ) demonstrated in the above graphs, i.e. 25–50 spectral points in the wavelength range 300–1000nm, requires 12 – 24 hours. COMSOL meshes the geometry, obtaining the number of DoF required to solve for, and uses very large matrices in the 3D case to solve the inverse problem for each electromagnetic quantity that appears in the original Maxwell’s equations, whether or not they are desired by the user for the problem at hand. This is repeated for each wavelength of interest. As such, COMSOL effectively generates a 4-D volume of data for each electromagnetic variable ( , etc), consisting of a field distribution in 3-D space with wavelength occupying the fourth dimension; although this routinely utilizes a couple of Gigabytes of hard drive storage, it is particularly convenient for probing electromagnetic quantities at any position in computational domain and at any solved wavelength, once the solution is achieved, allowing plots such as Figure 7 to be built and studied.

Given the long processing times and huge RAM utilized for 3-D geometries, there exists a memory limitation on the achievable meshing density (spatial sampling), as well as a compromise between spectral sampling and processing time, both which need consideration when solving complex geometries. Evidently, a numerical solver such as COMSOL would not be used for spherical geometries, where analytical methods such as the ME provide very accurate solutions for small particles, but instead for an arbitrarily-shaped geometry which the Mie scattering theory, and thus any Mie theory-derived approximation, are unable to accommodate.

Investigation of Small size effects

The aforementioned analysis used the Lorentz-Drude model for the dielectric function of both silver and gold, and excluded any correction to account for a more experimentally valid analysis of the electromagnetic behavior of such small particles. Although several factors contribute towards tweaking the shape of the plasmon band,41,42 the most prominent is the size-effect, which results in its damping and broadening. The small-size effect due to electron surface scattering at the particle boundaries becomes prominent as the metal thickness becomes smaller than the electron mean free path of a specific material. The electron mean free path for gold and silver are approximately 50nm,43–45 and the size-limiting effect is encompassed in the “effective mean free path” variable, Leff. Detailed comparison between experimental and calculated colloidal gold spectra have demonstrated that this size-correction need only be applied to the imaginary part of the bulk metal dielectric function;41,46 as such, Leff only appears in ε″ (5) and accounts for any additional loss incurred by the finite thickness of the nanoshell relative to the overall particle size. Here, λp is the wavelength of plasma oscillations, vF and c are the Fermi velocity of electrons and the light velocity in vacuum, respectively. The dimensionless parameter A detailing the electron scattering process is taken as unity.42,47

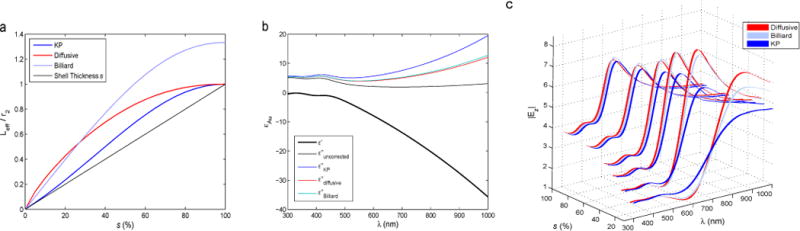

Moroz48 recently employed the nanoshell geometry to revisit a Leff model, (6), proposed by Kachan et al.,49 and further proposed two models that are suggested to be more accurate: (7), derived by considering diffusive scattering, and (8), derived from the billiard scattering model. These three equations are plotted as a function of relative shell thickness in Figure 9. Note that Eqs (6) and (7) differ only by the sign of the (1 – q) term in front of the Lognormal function.

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

Figure 9.

Comparison between the size-correction models , and for Au ND[20nm,5nm,20%]; (a) Leff v.s. shell thickness s, (b) Au Dielectric Function, εAu(λ) and (c) Comparison of three Leff models

The variable Leff is a real positive number that estimates the physical confinement experienced by electrons, and is therefore inversely proportional to the constricting effects of the shell thickness. Its incorporation ultimately broadens the plasmon band and leads to a diminishing of the overall intensity of the local E-field in the vicinity of metal nanoparticles, effects that disappear only in the limit Leff → ∞ (5). This implies that the size-effect is to be accounted for regardless of the particle size, although the effects will rapidly fade away with increasing size as will be demonstrated shortly.

Figure 9 (a) depicts the dependence of Leff/r2 on relative shell thickness, starting at the origin at increasing to 1 for and , but increasing beyond 1 for . This translates to corrections to the dielectric function of Gold displayed in Figure 9 (b), which were evaluated for a shell thickness s = 20%. The real part ε′ is unaffected but ε″ increases with decreasing Leff, for all λ. Figure 9(c) is a comparison between the |Ez| spectra of the 3 models forND[20nm,5nm,∆s] nanoshell dimers, as a function of shell thickness. This plot clearly emphasizes significant difference between them for thin shells, but they converge towards a similar E-field spectral profile in the limit r1 → 0.

In the remainder of the report, size-effects are investigated using the model, firstly because it introduces the greatest loss of the three, enabling the study of the greatest impact size-correction has on nanoparticle electromagnetics, and secondly due to the fact that it has already appeared as a size-correction model in the literature.50 Evidently, since all three boast similar behaviors, the trends depicted by will apply to the other two. The following section presents a quantitative comparison between uncorrected and size-corrected E-field spectra, using , for both silver and gold as a function of shell thickness and size.

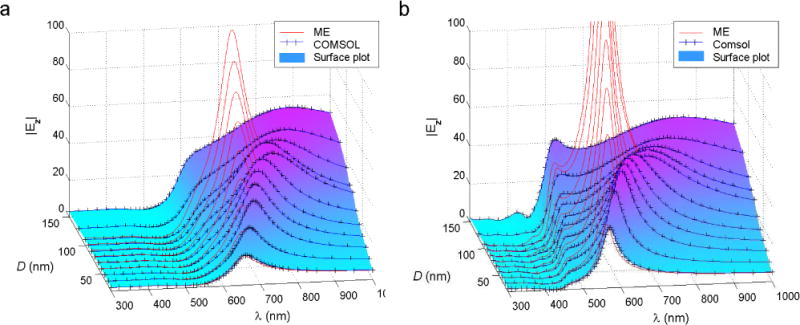

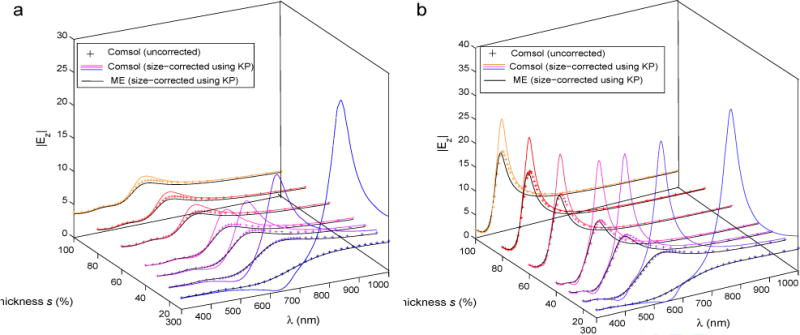

Figure 10 (a) and (b) compare FE(λ) curves of ME (size-corrected) and COMSOL (uncorrected and size-corrected), for gold and silver, respectively. Thus far, it has been established that COMSOL is both qualitatively and quantitatively up to par with ME, for small nanoparticles. The additional loss component in the dielectric function appears not to disrupt their correlation as seen by their good agreement in both graphs.

Figure 10.

FE(λ) using ε(λ)uncorrected and ε(λ)corrected as a function of shell thickness s for ND [20nm,5nm,∆s] of (a) Au and (b) Ag

The most striking feature is the significant FE(λ) damping and broadening experienced by the particles with thin shells, for both gold and silver. For s = 10%, gold experiences a ∼ 5× decrease in |Ez| and a ∼ 65% FWHM broadening, whereas silver conveys ∼ 6× decrease in |Ez| and a ∼ 75% broadening. With increasing shell thickness, both damping and broadening diminish as Leff reaches its maximum value for s = r2.

The effect of the size-correction on FE (λ) as a function of dimer size is presented in Figure 11, for which ND[∆D, 5nm, 20%] were employed. As observed throughout this analysis, the correction term affects the plasmon characteristics, rather than the off-resonance behavior of the particles. Indeed, in the range 300 – 500nm for gold, and 300 – 400nm for silver, the uncorrected and corrected versions as a function of shell thickness and dimer size are practically identical. They also converge in the long-wavelength limit. In addition, it is noteworthy than there still exists substantial error for the 150nm nanoshells, which suggests that that the correction term cannot be ignored even at these sizes and relative shell thicknesses.

Figure 11.

FE(λ) using ε(λ)corrected v.s. nanoshell diameter D, for ND[∆D,5nm,20%] of (a) Au and (b) Ag

Finally, these results are summarized in Figure 12. The first column unanimously shows that the difference between uncorrected and size-corrected FE(λ) tends towards zero as shell thickness increases. In addition to significant damping and broadening for thin shells, a substantial red-shift of the size-corrected curves also takes place, which is more pronounced for gold (λmax = 50nm) than for silver (λmax = 27nm). The ∆|Ez| and ∆FWHM variables show greater deviation for silver than for gold; however, the error seems to plateau for thicknesses greater than 40% in all three cases.

Figure 12.

Error between models employing ε(λ)uncorrected and ε(λ)corrected. The error is evaluated as follows: ∆var = varCOMSOL–uncorrected – varCOMSOL–corrected, where var represents variables |Ez|, ∆λmax or FWHM

The second column reiterate the trends observed with the data in Figure 10, with resonance damping, broadening and red-shifting all being greatest for small particles and reducing with increasing particle size. Interestingly, both metals appear to be more consistent with each other.

As a final note, it is of experimental interest to mention the impact of variations in the nanoshell dimer geometry on the SERS enhancement factor, SERSef, which is aforementioned to be approximately proportional to |Ez|4. The maximum SERS enhancement factors achieved in the dimer gap using ε(λ)uncorrected are extracted from Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. The thinnest shell of 10% yielded SERSef ∼ 274 = 53E5 and ∼ 374 = 1.9E6 for Au and Ag, respectively. The smallest interparticle distance of 1nm produced SERSef ∼ 1184 = 1.9E8 and ∼ 2004 = 1.6E9 for Au and Ag, respectively. With respect to dimer size, the 90nm and 50nm dimers were the strongest for Au and Ag, respectively, both interestingly generate SERSEF ∼ 564 = 9.8E6. These are very large SERSEF and would suggest that synthesizing extremely thin-shelled dimers that are very close to each other would yield even stronger enhancements. This is not the case, unfortunately, since the SERSEF are dramatically reduced with the incorporation of the size-effect, reflected in Figure 10 and Figure 11. For the same shell thickness, the SERSEF of both Au and Ag are reduced to a mere ∼ 54 = 625! The dramatic changes brought about by the forth power factor, used to estimate the SERS enhancement, emphasizes the importance of considering the size-effect to yield accurate models, especially for the design and characterization of small particles for use in SERS applications.

The numerical simulation package COMSOL Multiphysics is a versatile tool that can be confidently used for nanoscale electromagnetics of 3-D geometries. Although it is memory-intensive, the obtained result is accurate, as a function of both wavelength and space, to within a few percent of its theoretical counterpart; it additionally provides the ability to truly investigate the plasmonic behavior within and without a nanostructure of interest, which can then be reconciled with experimental analysis. In order to achieve this, however, it is noteworthy to emphasize that the size-dependence is of crucial importance, especially when dealing with the nanoshell geometry, for which electron mean free path models have been derived. COMSOL’s agile meshing algorithm and resulting solution accuracy would suggest it to be a more promising computational electrodynamics modeling tool than FDTD-based packages for use in the plasmonics arena.

Methods

The numerical simulations were performed with the commercial software package COMSOL Multiphysics (Version 3.4 with incorporated RF Module, installed on a dual-Quad Core 32GB RAM Workstation), which comprises electromagnetic code based on the Finite Element Method (FEM) http://www.comsol.com.

The computational domain containing the nanoparticle system of interest was delimited by Perfectly Matched Layers (PMLs) that efficiently absorb any scattering off the particles, thereby preventing any unwanted reflections in the domain. Adequate meshing of the geometry of interest is a critical step in a FEM simulation, since the spatial resolution in the computational domain needs to be high enough to capture fast changing geometries, which directly translates to solution accuracy. A new spatial mesh was interactively constructed for each unique variable combination ND[D,d,s] to ensure that the E-field was properly solved at the position (0,0,0). The meshing was considered sufficiently dense when little variation in the 2nd decimal place of the solved |Ez| was observed. In 3-D space, meshes usually consisted of between 180k to 350k points, representing between 1M to 2.7M DoF. This number decreased significantly in 2D to between 10–20k, corresponding to tens of thousands of DoF.

The spectral domain was sampled finely enough to ensure any rapid change in the spectrum would be captured with sufficient resolution to accurately compare both computational methods. This was especially critical around the plasmon resonance peak in all cases, and finer sampling was also required in regions where the trend was uncertain, such as the 400–500nm wavelength range for the silver dimers. The ME produced FE(λ) sampled at 2.5nm wavelength intervals, whereas the spectral resolution in COMSOL was dynamically selected according to the important features observed in FE(λ), thus varying between 5nm and 50nm wavelength intervals.

The presented data was assembled using MatLab and COMSOL’s in-house postprocessing environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants RO1 EB006201, RO1 ES014774. The authors thank Q. Liu, A. Degiron and S. Sajuyigbe, all from the department of ECE at Duke University, for insightful discussions of Computational Electromagnetic theory.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Derivation of Multipole Expansion for Nanoshell Dimer is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Kneipp K, Kneipp H, Manoharan R, Hanlon EB, Itzkan I, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Extremely Large Enhancement Factors in Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering for Molecules on Colloidal Gold Clusters. Applied Spectroscopy. 1998;52:1493–1497. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kneipp K, Kneipp H, Itzkan I, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering and biophysics. J Phys: Condens Matter. 2002;14:597–624. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nie S, Emory SR. Probing Single Molecules and Single Nanoparticles by Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Science. 1997;275:1102–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vo-Dinh T, Hiromoto M, Begun GM, Moody RL. Surface-Enhanced Raman spectroscopy for trace organic analysis. Anal Chem. 1984;56:1667. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vo-Dinh T, Houck K, Stokes DL. Surface-enhanced Raman Gene Probes. Anal Chem. 1995;66:3379. doi: 10.1021/ac00092a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vo-Dinh T. Surface-Enhanced Raman spectroscopy using metallic nanostructures. Trends in Anal Chem. 1998;17:557. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vo-Dinh T, Stokes DL. Surface-enhanced Raman detection of chemical vapors and aerosols using personal dosimeters. Field Anal Chem and Technol. 1999;3:346. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vo-Dinh T, Allain LR, Stokes DL. Cancer gene detection using surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) J Raman Spectrosc. 2002;33:511. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wabuyele M, Vo-Dinh T. Detection of HIV type 1 DNA sequence using plasmonics nanoprobes. Anal Chem. 2005;77:7810–7815. doi: 10.1021/ac0514671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoury CG, Vo-Dinh T. Gold Nanostars For Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering: Synthesis, Characterization and Optimization. J Phys Chem. 2008;112:18849–18859. doi: 10.1021/jp8054747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H-N, Vo-Dinh T. Multiplex detection of breast cancer biomarkers using plasmonic molecular sentinel nanoprobes. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:065101–065107. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/6/065101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang X-L, Jiang P, Ge G-L, Tsuji M, Xie S-S, Guo Y-J. Poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) (PVP)-Capped Dendritic Gold Nanoparticles by a ONe-step Hydrothermal Route and Their High SERS Effect. Langmuir. 2008;24:1763–1768. doi: 10.1021/la703495s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orendorff CJ, Gearheart L, Jana NR, Murphy CJ. Aspect ratio dependence on surface enhanced Raman scattering using silver and gold nanorod substrates. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8:165–170. doi: 10.1039/b512573a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLellan JM, Siekkinen A, Chen J, Xia Y. Comparison of the surface-enhanced Raman scattering on sharp and truncated silver nanocubes. Chem Phys Lett. 2006;427:122–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Driskell JD, Lipert RJ, Porter MD. Labeled Gold Nanoparticles Immobilized at Smooth Metallic Substrates: Systematic Investigation of Surface Plasmon Resonance and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:17444–17451. doi: 10.1021/jp0636930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hicks EM, Lyandres O, Hall WP, Zou S, Glucksberg MR, Duyne RPV. Plasmonic Properties of Anchored Nanoparticles Fabricated by Reactive Ion Etching and Nanosphere Lithography. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:4116–4124. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min Q, Santos MJL, Girotto EM, Brolo AG, Gordon R. Localized Raman Enhancement from a Double-Hole Nanostructure in a Metal Film. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:15098–15101. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grand J, Kostcheev S, Bijeon J-L, de la Chapelle ML, Adam P-M, Rumyantseva A, Lerondel G, Royer P. Optimization of SERS-active substrates for near-field Raman spectroscopy. Synthesis Metals. 2003;139:621–624. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oubre C, Nordlander P. Finite difference time domain studies of optical properties of nanoshell structures. Proceedings of SPIE. 2003;5221:133–143. doi: 10.1021/jp044382x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhawan A, Norton SJ, Gerhold MD, Vo-Dinh T. Comparison of FDTD numerical computations and analytical multipole expansion method for plasmonics-active nanosphere dimers. Optics Express. 2009;17:9688–9703. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.009688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oubre C, Nordlander P. Finite-Difference Time-Domain Studies of the Optical Properties of Nanoshell Dimers. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:10042–10051. doi: 10.1021/jp044382x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chau Y-F, Yeh H-H, Tsai DP. Near-field optical properties and surface plasmon effects generated by a dielectric hole in a silver-shell nanocylinder pair. Applied Optics. 2008;47(30):5557–5567. doi: 10.1364/ao.47.005557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui X, Erni D. Enhanced propagation in a plasmonic chain waveguide with nanoshell structures based on low- and high-order mode coupling. J Opt Soc Am A. 2008;25(7):1783–1789. doi: 10.1364/josaa.25.001783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chau Y-F, Yeh HH, Tsai DP. Surface plasmon effects excitation from three-pair arrays of silver-shell nanocylinders. Physics of Plasmas. 2009;16:022303. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Issa NA, Guckenberger R. Optical Nanofocusing on Tapered Metallic Waveguides. Plasmonics. 2007;2:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown RJC, Wang JT, Milton MJ. Electromagnetic Modelling of Raman Enhancement from Nanoscale Structures as a Means to Predict the Efficacy of SERS Substrates. Journal of Nanomaterials. 2007;2007:12086–12096. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knorr I, Christou K, Meinertz J, Selle A, Ihlemann J, Marowsky G. Prediction and optimization of Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering geometries using Comsol Multiphysics. Excerpt from the Proceedings of the COMSOL conference Hannover. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrhold K, Christiansen S, Gosele U. Plasmonic Properties of Bimetal Nanoshell Cylinders and Spheres. Excerpt from the Proceedings of the COMSOL Conference Hannover. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerardy JM, Ausloos M. Absoprtion spectrum of clusters of spheres from the general solution of Maxwell’s equations. The long-wavelength limit. Phys Rev B. 1980;22:4950–4959. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norton SJ, Vo-Dinh T. Optical response of linear chains of metal nanopsheres and nanospheroids. J Opt Soc Amer. 2008;25:2767–2775. doi: 10.1364/josaa.25.002767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandl DW, Oubre C, Nordlander P. Plasmon hybridization in nanoshell dimers. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2005;123:024701–1–024701–11. doi: 10.1063/1.1949169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lassiter JB, Aizpurua J, Hernandez LI, Brandl DW, Romero I, Lal S, Hafner JH, Nordlander P, Halas NJ. Close Encounters between Two Nanoshells. Nano Letters. 2008;8:1212–1218. doi: 10.1021/nl080271o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Averitt RD, Sarkar D, Halas NJ. Plasmon resonance shifts of Au-coated Au2S nanoshells: Insight into multicomponent nanoparticle growth. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;78:4217–4220. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ru ECL, Etchegoin PG. Rigorous justification of the |E|4 enhancement factor in Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Chemical Physics Letters. 2006;423:63–66. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palik ED. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liz-Marzan LM, Giersig M, Mulvaney P. Synthesis of Nanosized Gold-Silica Core-Shell Particles. Langmuir. 1996;12:4329–4335. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergna HE, Roberts WO. Colloidal Silica: fundamentals and applications. CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerker M. Electromagnetic model for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) on metal colloids. Acc Chem Res. 1984;17:271–277. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishchenko MI, Hovenier JW, Travis LD. Light Scattering by Nonspherical Particles. Academic Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerker M. Scattering of Light and Other Electromagnetic Radiation. Academic Press; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khlebtsov NG, Bogatyrev VA, Dykman LA, Melnikov AG. Spectral Extinction of Colloidal Gold and Its Biospecific Conjugates. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 1996;180:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westcott SL, Jackson JB, Radloff C, Halas NJ. Relative contributions to the plasmon line shape of metal nanoshells. Physical Review. 2002;66:155431, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashcroft NW, Mermin ND. Solid State Physics. Saunders College; Philadelphia: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kittel C. Introduction to Solid State Physics. Wiley; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreibig U, Fragstein CV. The Limitation of Electron Mean Free Path in Small Silver Particles. Z Physik. 1969;224:307–323. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scaffardi LN, Pellegri N, de Sacntis O, Tocho JO. Sizing gold nanoparticles by optical extinction spectroscopy. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:158–163. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coronado EA, Schatz GC. Surface plasmon broadening for arbitrary shape nanoparticles: A geometrical probability approach. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2003;119(7):3926–3934. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moroz A. Electron Mean Free Path in a Spherical Shell Geometry. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2008;112(29):10641–10652. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kachan SM, Ponyavina AN. Resonance absorption spectra of composites containing metal-coated nanoparticles. Mol Struct. 2001;267:563–564. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khlebtsov B, Khlebtsov N. Ultrasharp light-scattering resonances of structured nanospheres: effects of size-dependent dielectric functions. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2006;11(4):044002, 1–5. doi: 10.1117/1.2337526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.