Abstract

Membrane vesicles (MVs) of Porphyromonas gingivalis are regarded as an offensive weapon of the bacterium, leading to tissue deterioration in periodontal disease. Therefore, isolation of highly purified MVs is indispensable to better understand the pathophysiological role of MVs in the progression of periodontitis. MVs are generally isolated by a conventional method based on ultracentrifugation of the bacterial culture supernatant. However, the resulting MVs are often contaminated with co-precipitating bacterial appendages sheared from the live bacteria. Here, we report an intriguing property of P. gingivalis MVs–their ability to bind superparamagnetic beads coated with epoxy groups (SB-Epoxy). Analysis of fractions collected during the purification revealed that all MVs of five tested P. gingivalis stains bound to SB-Epoxy. In contrast, free fimbriae in the crude MV preparation did not bind to the SB-Epoxy. The SB-Epoxy-bound MVs were easily dissociated from the SB-Epoxy using a mild denaturation buffer. These results suggest that the surface chemistry conferred by epoxy on the beads is responsible for the binding, which is mediated by noncovalent bonds. Both the structural integrity and purity of the isolated MVs were confirmed by electron microscopy. The isolated MVs also caused cell detachment from culture dishes at a physiologically relevant concentration. Assays of competitive binding between the SB-Epoxy and mixtures of MVs from five bacterial species demonstrated that only P. gingivalis MVs could be selectively eliminated from the mixtures. We suggest that this novel approach enables efficient purification and selective elimination of P. gingivalis MVs.

Introduction

Among the various Gram-negative anaerobes that reside within the subgingival pockets, Porphyromonas gingivalis is regarded as a keystone pathogen in the development of periodontal diseases, due to its ability to orchestrate inflammation while being a minor constituent in the community of periodontal pockets [1]. Transient bacteremia occurs even after tooth brushing in periodontally healthy individuals [2] and the incidence and magnitude of bacteremia after scaling is significantly higher in periodontitis patients than in gingivitis patients and healthy control individuals [3]. For that reason, periodontitis patients are at risk for a wide range of bacteria-related systemic diseases based on persistent inflammation. Recent reports from epidemiological studies [4], [5] as well as in vitro and animal model experiments [6]–[8] have shown an association between periodontitis and systemic inflammatory diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and atherosclerosis. Therefore, development of a novel remedy against periodontal diseases would have a significant impact on improving general public health.

Both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria produce and release spherical, microstructural bodies called membrane vesicles (MVs) that range in size from 10 to 300 nm in diameter [9]. MVs contribute to a pathogen’s potential through toxin export [10]–[12] and adherence to eukaryotic cells [13]. As with other bacteria, P. gingivalis MVs have also been regarded as offensive weapons leading to tissue deterioration in periodontal disease [14]. MVs carry a wide range of virulence factors such as LPS, gingipains Rgps and Kgp, hemagglutin HagA, carboxypeptidase CPG70, peptidylarginine deiminase PAD, hemin-binding protein HBP35, and fimbrial proteins FimA and FimD; notably, periodontal tissue destruction mediated by gingipain-laden MVs has been suggested [15]. On the other hand, MVs (of Neisseria meningitidis) are also used for vaccination purposes to protect against bacterial pathogens in human [16]. Recently, the crucial role of P. gingivalis MVs in mucosal immunogenicity was shown by an in vivo study [17], suggesting the potential of MVs as non-replicating mucosal immunogens for periodontal disease vaccines.

Several methods have been used for the isolation of bacterial MVs from culture supernatants. Precipitation using ammonium sulfate [18] or ultracentrifugation [19] are the most common procedures. However, these methods do not yield sufficiently pure material for experimental use, because bacterial appendages such as fimbriae and flagella also co-precipitate with MVs of Escherichia coli [20] and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [21] during ultracentrifugation under the commonly used conditions. In general, P. gingivalis MVs are conventionally isolated from culture supernatant using a combination of membrane filtration and ultra-centrifugation [17], [22], [23]. In our previous study, fimbriae liberated from whole cells of P. gingivalis also appeared to co-precipitate with the MVs after ultracentrifugation [15]. Further purification using density-gradient centrifugation is an option, however, the procedure is relatively complicated and time-consuming. Therefore, development of novel methodology that enables purification of highly purified MVs or selective capture of the MVs is highly desired to enable a better understanding of the involvement of MVs in immunopathology and vaccinology of periodontal diseases.

In this article, we describe a simple and efficient approach to obtain highly purified MVs of P. gingivalis by exploiting the specific binding of MVs to superparamagnetic beads coated with epoxy groups (SB-Epoxy). Separation technology using SBs has been widely applied for purifying proteins, nucleic acids, and cells. The main advantages of this magnetic separation technique are due to their superparamagnetic properties, which result in easy handling, negligible sample loss, and superior reproducibility. We present here the technique’s utility for purifying MVs, and the structural and biological integrity of the resulting MVs. We also report that only P. gingivalis MVs are successfully eliminated from mixtures of MVs from different bacterial species. The applicability of this novel approach for both experimental and clinical settings is discussed.

Materials and Methods

1. MV Preparation by the Conventional Method

P. gingivalis strain ATCC 33277 was the primary strain used in this study, as many fimbriae are found in crude MV preparation. Strains FDC 381, W50, YH522, and W83, were also used in some experiments. All strains of P. gingivalis were maintained under anaerobic conditions as described previously [24]. MVs were prepared from a culture of P. gingivalis collected at early stationary phase, described previously [17]. In brief, a two-day bacterial culture was centrifuged at 7,190×g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and filtered through a PVDF membrane with pore size 0.22 µm. The flow-through was collected and further ultra-centrifuged at 100,000×g for 3 h at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) and used as “crude MVs”. We also isolated crude MVs from eleven other strains of two oral bacteria and four non-oral bacteria as follows: two Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans strains Y4 (our collection) and ATCC 29522 (our collection), two Fusobacterium nucleatum strains ATCC 23726 (our collection) and #20 (a gift from Kazuyuki Ishihara at Tokyo Dental College); three strains of Escherichia coli [one K-12 strain KP7600 (NIG collection, Japan) and two uropathogenic E. coli strains P15 and RC4 (our collection)]; one strain of N. meningitidis H44/76 [25]; two strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1-Tokai (our collection) and PAO1-Holloway (our collection); and one Clostridium perfringens strain 13 (our collection). Crude MVs from A. actinomycetemcomitans were isolated by using the same isolation method used for crude P. gingivalis MVs. Crude MVs from species other than P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans were prepared in the manner except for using PVDF membranes with pore size 0.45 µm. PVDF filters with pore size 0.22 µm were used for filtration of MVs of P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans, as the diameter of these cells is smaller than that of the other species used in this study. We used the Bradford assay as a protein-based quantification method to determine the amount of purified MV.

2. Further Purification of MVs using SB Technology

We previously observed that MVs prepared by ultracentrifugation of culture supernatants were contaminated with bacterial appendages such as fimbriae, as the bacterial appendages co-precipitate with the MVs [15]. To eliminate the contaminating bacterial appendages, we exploited the binding affinity between MVs and superparamagnetic beads (SBs) to further purify the MVs. Dynabeads M-270 epoxy (SB-Epoxy) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) were mainly used for the purpose. We also used two other SBs of the same bead size (2.8 µm in diameter) but with different surface chemistries, Dynabeads M-270 amine (SB-NH2) (Life Technologies) and Dynabeads M-270 carboxylic acid (SB-COOH) (Life Technologies) to compare the binding properties of MVs of P. gingivalis. Five µg of crude MV preparation from P. gingivalis was resuspended in 100 µl of 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) (final concentration of MVs: 500 ng/ml) and incubated with 20 mg (wet weight) of the SBs for 14 hours at 4°C on a rotator. After incubation, the SB-MV conjugates were collected and washed five times with PBS to remove unbound components. To dissociate the bound components from the SBs, the beads were incubated with mild denaturation buffer containing urea at a concentration of 2 M for 5 min at 15–24°C. Incubation with the urea buffer was repeated once. After the SBs were washed once again with PBS, the components still bound to the SBs even after urea treatment were further treated with PBS containing 4% CHAPS. The volume of all buffers used during the purification was fixed at 100 µl. For the experiments described under section “2.4. SDS-PAGE and Western blot”, 60 µl of each fraction were mixed with same volume of 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 2% SDS and 6% 2-mercaptoethanol. The rest (40 µl) of each fraction were individually dialyzed in a single batch against the same container of 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8) buffer to remove urea or CHAPS. The dialyzed MV samples were concentrated by ultrafiltration and reconstituted with 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8) buffer to a final volume of 40 µl. The reconstituted fractions and the crude MVs samples (500 ng/ml) were diluted 1∶10 with PBS and used for the experiments described in section “2.5. Assays for cell detachment from cell culture wells”.

In some experiments, SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 2% SDS and 6% 2-mercaptoethanol was directly added to SBs to elute the components bound to the SBs. After incubation of the crude MVs with SBs, the beads were also treated with 1 to 4 M NaCl buffer or 50 mM Glycine buffer (pH 2.8), in order to examine whether any of these buffers could dissociate the components bound to the SBs. Only SB-Epoxy was regenerated by washing with PBS containing 2% SDS, followed by five washes with PBS. Further, the binding efficacy of MVs to regenerated SB-Epoxy was unaffected even after reuse at least 10 times (data not shown).

3. Electron Microscopy (EM) Analysis

The MV-SB-Epoxy conjugates were prepared by the same method described in section “2. Further purification of MVs using SB technology”. The resultant MV-SB conjugates were analyzed by scanning EM, S-5200 (HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan). Sample preparation for scanning EM was described previously [17]. The crude MVs and the samples fractionated from the crude MVs were analyzed by transmission EM, H-7650 (HITACHI). Samples for transmission EM were allowed to adhere to carbon-coated grids for 1 min at 15–24°C, then negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate.

4. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot (WB)

Samples fractionated from MV preparations were analyzed by a standard protocol of SDS-PAGE using 12.5% polyacrylamide gels. After SDS-PAGE, some gels were visualized with staining using silver or Bio-Safe Coomassie (CBB, Bio-rad), and others were electroblotted onto PVDF membranes for WB analysis. Rabbit polyclonal antibody against a major fimbrial protein of P. gingivalis (anti-FimA antibody, a gift from Nobushiro Hamada at Kanagawa Dental University), a catalytic domain of arginine-gingipain A (anti-Rgp antibody) [26], and a hemin-binding protein 35 (anti-HBP35 antibody) [27], were used at 1∶1000, 1∶10,000, and 1∶5,000 dilutions, respectively. Mouse monoclonal antibody against an anionic lipopolysaccharide of P. gingivalis (anti-A-LPS antibody) [26] was used at 1∶1000 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and anti-mouse IgG (Life technologies) were used as the secondary antibody at 1∶200,000 and 1∶5,000 dilutions, respectively. Chemiluminescence was developed by ECLplus (GE Healthcare) and visualized by exposure on X-ray film.

5. Assays for Cell Detachment from Cell Culture Wells

An oral squamous epithelial cell carcinoma cell line, Ca9-22 [28], was maintained in RPMI1640 media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (50 µg/ml) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The effect of samples prepared from P. gingivalis on cell detachment was examined on confluent monolayers of Ca9-22 cells in 24-well culture plates. The cell monolayers were washed three times with PBS to wash out the residual fetal bovine serum in the media. Ten-fold diluted samples were prepared as described in section “2. Further purification of MVs using SB technology”. Two hundred µl of the diluted samples were added to the wells. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 1 hour. The wells were gently washed twice with 1 ml of PBS to remove detached cells. Changes in cell appearance were recorded after the two washes with PBS by an inverted-optical microscopy (CKX41, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Eventually, undetached cells were fixed with 200 µl of 70% methanol for 10 min, stained with 200 µl of 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min, and rinsed twice with 1 ml of distilled water. Crystal violet dye associated with cells was eluted with 500 µl of 100% ethanol. Amounts of detached Ca9-22 cells were quantified by absorbance at 595 nm.

6. Time-lapse Observation of Ca9-22 Cells

Ca9-22 cells were grown on a glass-bottom dish (CELLview cell culture dish, Greiner) coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma-aldrich). The assay was performed soon after cells reached confluence. Following replacing the culture medium to Eagle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS) with or without purified MVs (20 µg/ml), phase contrast images of the cells were captured. The optical system consisted of an inverted-epifluorescence microscopy (IX71, Olympus) equipped with a phase objective (UPlanFl 40x, Olympus), a stage-top incubator (Tokai Hit) and an EMCCD camera (iXon DU-897E, Andor). The z-position of the objective was controlled by a piezo-electric actuator with an electrostatic capacity sensor (PI, Germany), which enabled us to obtain three-dimensional images and to overcome the drift in focus position during the long observation time.

7. Assay of Competitive Binding with SB-Epoxy using a Mixture of MV Preparations from Several Strains

We assayed the competitive binding of a mixture of crude MVs from several species with SB-Epoxy. Five µg each of crude MVs from P. gingivalis ATCC 33277, E. coli KP7600, N. meningitidis H44/76, P. aeruginosa PAO1-Tokai, and C. perfringens strain 13 were suspended together in 100 µl of 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) containing 20 mg (wet weight) of the SB-Epoxy and incubated at 4°C for 14 hours on a rotator. After five washes with PBS, SDS-PAGE loading buffer was directly added to elute components bound to the SB-Epoxy. The wash and elution fractions collected during this procedure were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

8. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry and Peptide Mass Fingerprinting (PMF)

After SDS-PAGE, Coomassie brilliant blue stained protein bands were excised from the gels, and in-gel digestion with trypsin (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) was performed. The tryptic peptide samples were analyzed by an AB SCIEX TOF/TOF 5800 System (AB SCIFX, Foster City, CA). The MS data were analyzed by the Mascot Peptide Mass Finger Print search engine (Matrix Science, Inc., Boston, MA). Peptide mass tolerance for Mascot analysis was set at ±100 ppm, and one missed cleavage by trypsin and variable oxidation of methionine were allowed.

9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett's multiple comparison test. P-values of 0.05 or less were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

1. P. gingivalis MVs Preferentially Bind to SB-Epoxy

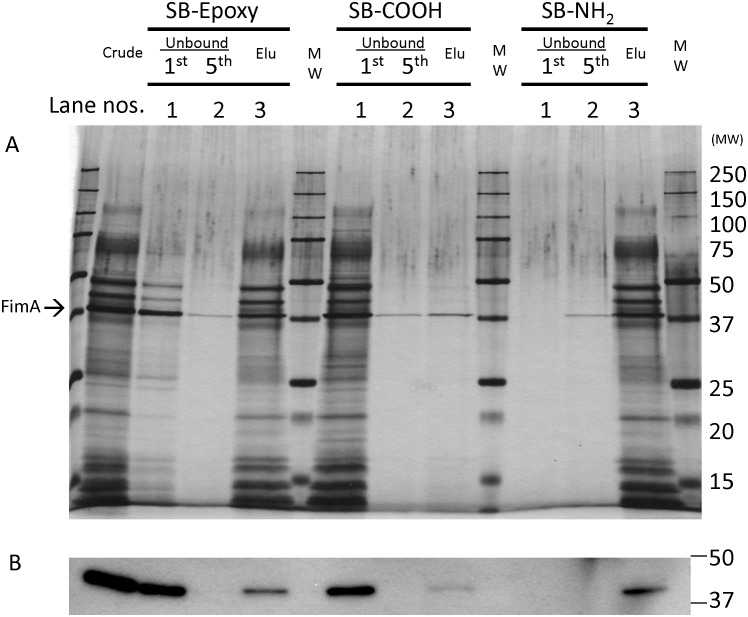

During a course of experiments using SB-Epoxy and P. gingivalis MVs, we unexpectedly found that MVs of P. gingivalis appeared to bind to the beads after a 14-hour incubation at 4°C. In order to assess the binding properties of MVs to SBs, we chose three SBs with the following different surface chemistries–SB-NH2, SB-COOH, and SB-Epoxy–and examined the protein profiles of the fractions collected during purification (Fig. 1A). Physicochemical properties of the three SBs are shown in Table 1. We previously observed that P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 MVs prepared by ultracentrifugation contained many fimbriae [15]. Therefore, we chose strain 33277 for purification of P. gingivalis MVs and the crude MVs were used for the binding assay with the SBs. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed a typical protein profile of the 33277 MVs [15] in the lane of the “Crude” fraction (Fig. 1A). A major band on a silver-stained gel at 40 kDa was identified as the major fimbrial protein FimA by mass spectrometry (shown by the arrow in Fig. 1A) and WB (Fig. 1B). When SB-NH2 was used for this assay, both the MVs and the fimbriae bound to the SB-NH2, as few proteins were observed in the lanes of the unbound fractions (Unbound, 1st and 5th). In contrast, with SB-COOH, both MVs and fimbriae bound minimally to the SB-COOH, as most of the starting materials (Crude) were washed out in the first unbound fraction (Unbound, 1st). Unlike SB-NH2 and SB-COOH, SB-Epoxy could bind MVs while most fimbriae were removed by washing, although a faint FimA signal was detected in the elution fraction even after extensive washing.

Figure 1. Binding of MVs of P. gingivalis to SBs.

Binding of P. gingivalis MVs to SBs was examined by SDS-PAGE (A: silver staining, B: WB of FimA). Five µg of the starting material from conventional purification (Crude) was incubated with same amount (20 mg, wet weight) of three SBs with different surface chemistries (SB-Epoxy, SB-COOH, and SB-NH2). After incubating the crude MVs with SBs, unbound components were washed five times with PBS. The first and fifth unbound fractions are applied to the wells (Unbound, 1st and Unbound, 5th, or lanes 1 and 2). Then bound components were eluted by addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer (Elu or lane 3). “MW” denotes the molecular weight marker. The same volume (10 µl) of samples was applied to each well of the PAGE gel. (B) Identical samples to those used in (A) were used for the WB of FimA. The location of FimA is shown by an arrow.

Table 1. Comparison of three different SBs with different surface chemistries.

| SB-Epoxy | SB-NH2 | SB-COOH | |

| Sizes (diameter) | 2.8 µm | 2.8 µm | 2.8 µm |

| Chemical formula of surfaces | Epoxy group | Amino group | Carboxylic acidgroup |

| Hydrophobicity * | More hydrophobic thanSB-COOH | More hydrophobic thanSB-COOH | Extremelyhydrophilic |

| Charge * | Slightly positive | Positive | Negative |

*The hydrophobicity and surface charge of each SB were determined by a contact angle and zeta potential analysis, respectively. Information about SBs is available upon request from the authors (Dynal Biotech Technical Support, unpublished data).

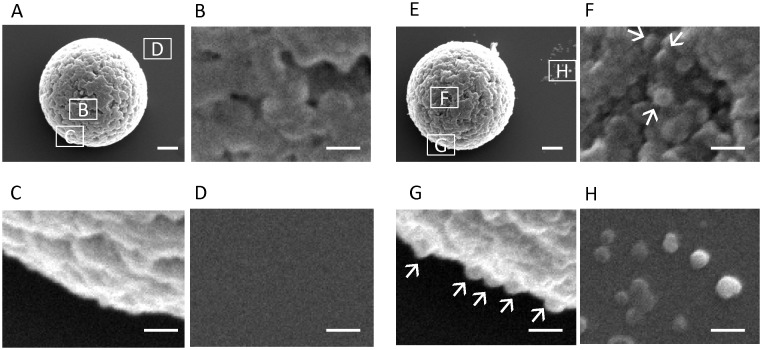

The SB-Epoxy-MV conjugates were analyzed by scanning EM to directly observe binding (Fig. 2A–H). We clearly found MVs on the surface of the SB-Epoxy incubated with MVs but not on the SB-Epoxy incubated with control buffer. The dissociated MVs were also observed on the background behind the SB-Epoxy.

Figure 2. Electron microscopy of SB-Epoxy-MV conjugates.

Electron micrographs of SB-Epoxy incubated with control buffer (A–D) or with the crude MVs (E–H) are shown. Areas of micrographs shown at higher magnification (B–D) and (F–H) are indicated in panels (A) and (E), respectively, by the corresponding boxed letters. MVs are shown by arrows. Bars in (A) and (E): 500 nm. Bars in (B–D) and (F–H): 100 nm.

These data suggest that the binding of MVs with SBs is dependent on different surface chemistries conferred by different functional groups. Of note, the findings of the preferential and specific binding of MVs to SB-Epoxy suggested that these beads could be employed to improve the purification of P. gingivalis MVs. Therefore, in the present study we have focused on investigating the binding between the MVs and SB-Epoxy.

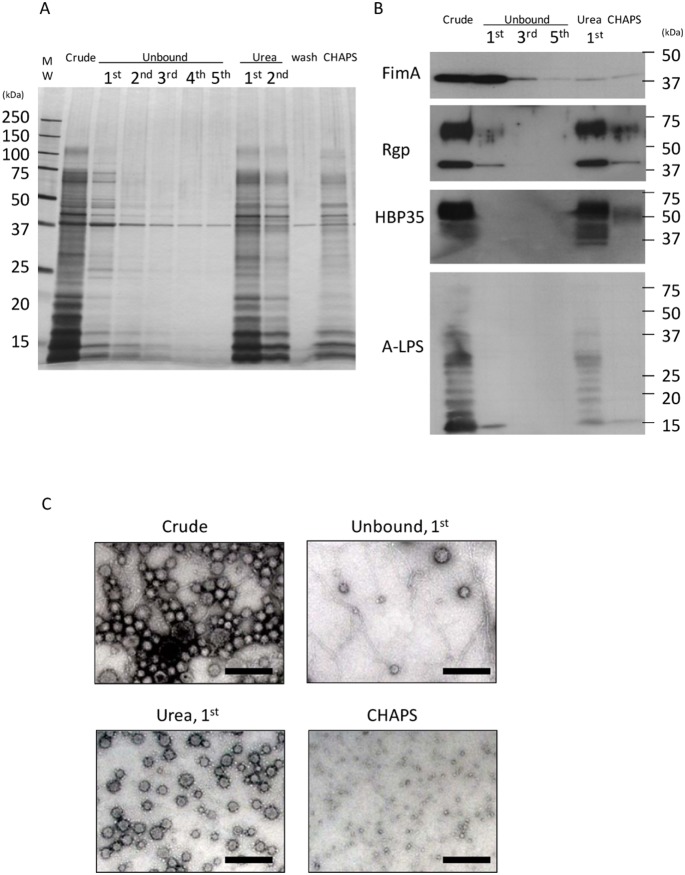

2. Isolation of MVs with High Purity and Structural Integrity using SB Technology

We tried to establish the conditions under which MVs would dissociate from SB-Epoxy (Fig. 3A and B). Similar to the results shown in Fig. 1A and B, most of the fimbriae were eliminated after five washes, with only a small amount of fimbriae remaining. First, the SB-Epoxy-MV conjugates were treated with either low pH buffer or high salt buffer. However, the MVs did not dissociate at all from SB-Epoxy (data not shown). Second, we treated the SB-Epoxy-MV conjugates with buffer containing different concentrations of urea ranging from 1 M to 8 M and found that greater than 2 M urea enables efficient dissociation of binding (data not shown). The fraction eluted by 2 M urea buffer contained major MV proteins such as gingipains and HBP35 as well as A-LPS (Fig. 3A and B) whose structure is characteristic of P. gingivalis [29]. These SDS-PAGE data showed good agreement with the transmission EM data where the fraction eluted with urea buffer (Urea, 1st) contained very little fimbriae, while fimbriae were abundantly detected in the starting materials (Crude) and in the first unbound fraction (Unbound, 1st), but not in the subsequent fractions (Fig. 3C). Consequently, we succeeded in isolating highly purified MVs that maintained their structural integrity. In contrast, there were no morphologically intact MVs in the fraction eluted by a detergent, 4% CHAPS (CHAPS), because the MV lipid bilayer was destroyed by CHAPS.

Figure 3. Isolation of highly purified MVs using SB-Epoxy.

MV purification was performed by incubating SB-Epoxy with the crude MVs. Five µg of the starting material from conventional purification (Crude) was incubated with 20 mg (wet weight) of SB-Epoxy. After incubating the crude MVs with SBs, unbound components were washed five times with PBS (Unbound). Subsequently, bound components were eluted twice with a mild denaturation buffer containing 2 M urea (Urea). After one wash with PBS (Wash), the components still bound to the SB-Epoxy even after urea treatment were treated with 4% CHAPS buffer (CHAPS). “MW” denotes the molecular weight marker. (A) Each fraction was analyzed by silver staining. The same volume (10 µl) of samples was applied to each well of a PAGE gel. (B) The same sample set was used for WBs using anti-FimA, Rgp, HBP35, and A-LPS. In the WB of Rgp, diffuse bands around 60–70 kDa and relatively sharp bands around 40 kDa are observed, probably due to the presence of both glycosylated and non-glycosylated forms of Rgps in the MVs, respectively. HBP35 also appears as diffuse bands because of modification of the HBP35 protein with different-sized glycans. A typical ladder pattern is observed in WB detecting A-LPS. (C) The contents of each fraction was examined by transmission EM. Bars: 200 nm.

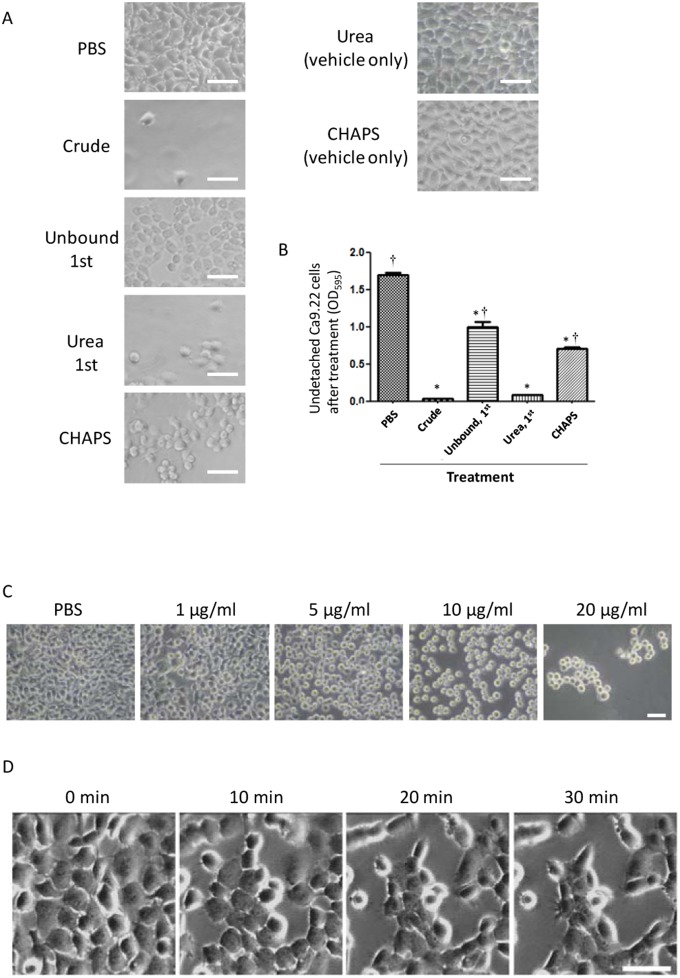

3. Detachment of Epithelial Cells from Cell Culture Wells Induced by the Highly Purified MVs

In a previous study, we found that P. gingivalis MVs caused detachment of epithelial cells in a gingipain-dependent manner [15]. To assess whether the MVs purified using SB-Epoxy are biologically intact, we performed a cell detachment assay using the crude MVs and the fractions from SB-Epoxy purification (Fig. 4). Following treatment with each sample, cell detachment activity was evaluated by staining undetached cells as well as microscopic observation (Fig. 4A and 4B). The strongest activity was in the starting material (Crude) and comparable activity was seen in the first urea-eluted fraction (Urea, 1st). Significantly lower activities were detected in the first unbound fraction (Unbound, 1st) and the CHAPS-eluted fraction (CHAPS) as compared with the starting material (Crude). To assess whether the dialysis was effective for complete removal of urea or CHAPS, the vehicle alone (2 M urea or 4% CHAPS without the MV sample) was dialyzed and used for the detachment assay [Urea (vehicle only) and CHAPS (vehicle only)]. Our findings confirmed that the dialyzed vehicle did not affect cell morphology or detachment (Fig. 4A). These results showed good agreement with the EM findings (Fig. 3C) where we observed a small amount of MVs in the “Unbound, 1st” fraction and the remains of destroyed MVs in the “CHAPS” fraction. We also observed a dose-dependent effect of the purified MVs on cell detachment (Fig. 4C). Time-lapse observation after addition of the purified MVs demonstrated that disruption of cell-cell adhesion and focal adhesion occurred swiftly (Fig. 4D, and Video S1 and S2).

Figure 4. Effect on cell detachment of the crude MVs and SB purification fractions.

Cell detachment activity of samples fractionated using SB-Epoxy was investigated using Ca9.22 cell monolayers. (A) The cell monolayers were treated with PBS only (PBS), crude MV preparation (Crude), first unbound fraction (Unbound, 1st), first urea fraction (Urea, 1st), and CHAPS fraction (CHAPS). In order to confirm complete removal of urea and CHAPS, the monolayers were also treated with dialyzed urea buffer [Urea (vehicle only)], and dialyzed CHAPS buffer [CHAPS (vehicle only)]. Bars: 50 nm. (B) The amount of detached cells was determined by crystal violet staining and measuring absorbance at 595 nm (mean ± SD), assayed in triplicate. *P<0.05, compared to PBS-treated cells. †P<0.05, compared to cells treated with the crude MV preparation (Crude). (C) Cell appearances after treatment with PBS control (PBS) and PBS containing MVs at concentrations of 1, 5, 10, and 20 µg/ml are shown. After treatment with different concentrations of MVs, micrographs of the treated cells were taken. Bar: 50 µm. (D) Time-lapse images of Ca9.22 cells in the presence of the SB-purified MVs. Morphological changes of Ca9.22 cells are shown. Loss of focal adhesion and cell-cell adhesion resulted in cell rounding, followed by detachment from the culture wells. The images were acquired at intervals of 30 sec for 30 min immediately after addition of MVs [See Video S1 with S2 (movie of cells in the absence of MVs)]. Bar: 50 µm.

4. Alternative Approach using SBs for Selective Capture of MVs of P. gingivalis

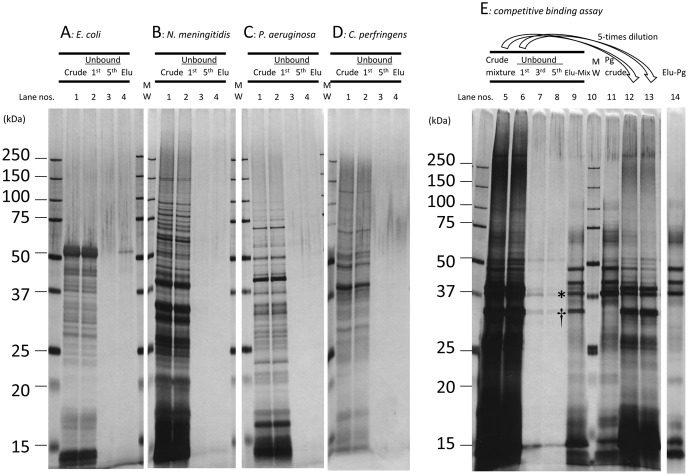

To examine whether P. gingivalis MVs bind to SB-Epoxy in a species-specific manner, we assessed whether MVs of other P. gingivalis strains also could bind to the SB-Epoxy and whether MVs derived from eleven strains of the other six species (including two other periodontopathic species) could bind to the SB-Epoxy. We confirmed that MVs isolated from other 4 strains of P. gingivalis as well as strain 33277 could bind to SB-Epoxy, although the binding capacities of these MVs depend on the individual strains (Fig. S1). On the contrary, SB-Epoxy bound extremely poorly to MVs of all the bacterial species tested except P. gingivalis. Results of one or two representative strain(s) of each species are shown (Fig. 5A–D and Fig. S2). To examine the applicability of this approach for selective capture of P. gingivalis MVs, we performed a competitive binding assay using SB-Epoxy and mixtures of crude MVs from several strains (Fig. 5E). Most of the crude MV preparation proteins (lanes 5 and 12, Crude mixture) were washed out in the first unbound fraction (lanes 6 and 13, Unbound 1st). A comparison of the protein profile of the elution fraction from the MV preparation mixtures (lane 9, Elu-Mix) with that of the P. gingivalis MV preparation preparation input (lane 11, Pg Crude) showed that the protein profile of the elution fraction (lane 9) was similar to that of the P. gingivalis crude MVs (lane 11), except for a decreased FimA band (denoted by asterisk) and unusual 34-kDa band (denoted by dagger). Furthermore, the protein profile in the lane 9 was nearly identical to that of the elution fraction from the P. gingivalis crude MVs (lane 14), except for only the 34-kDa band. The presence of P. gingivalis MVs in the elution fraction was also confirmed by WB using antiserum against P. gingivalis-specific A-LPS (data not shown). These data showed that P. gingivalis MVs could be selectively captured by specific binding to SB-Epoxy. The band at 34 kDa observed in the elution fraction was identified as PorB derived from N. meningitides by Mass spectrometry analysis. In order to focus on the association between P. gingivalis MV and neisserial PorA, we designed another competitive binding assay using MV preparations of two species: P. gingivalis and N. meningitidis (Fig. S3). In this assay, we again observed the decreased FimA band (denoted by an asterisk) and the 34-kDa band (PorB) (denoted by a dagger) in the elution fraction. These data demonstrated that SB-Epoxy selectively bound to P. gingivalis MVs and PorB was associated with the P. gingivalis MVs.

Figure 5. Binding to SB-Epoxy of MVs from different bacterial species.

Shown are results of the assays using crude MV preparations from the following five different species: E. coli KP7600, N. meningitidis H44/76, P. aeruginosa PAO1 Holloway, C. perfringens strain 13, and P. gingivalis ATCC 33277. (A-D) Crude MVs from a single strain was incubated with the SB-Epoxy. Unbound components were collected in five washes and bound components were eventually eluted by SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Lanes denoted “1” are the starting material from conventional purification (Crude). Lanes denoted “2” are the first unbound fractions (Unbound, 1st). Lanes denoted “3” are the fifth unbound fractions (Unbound, 5th). Lanes denoted “4” are the elution fractions (Elu). (A: E. coli KP7600, B: N. meningitidis H44/76, C: P. aeruginosa PAO1-Tokai, D: C. perfringens strain 13). (E) Crude MVs from the five species were mixed with SB-Epoxy. The selective elimination of P. gingivalis MVs from the mixture is shown. Lanes 5 &12: the input of mixtures of crude MVs (Crude mixture). Lanes 6 & 13: the first unbound fractions (Unbound, 1st). Lanes 12 & 13: five-fold diluted samples of lanes 5 & 6, respectively. Lanes 7, 8, & 9: the third unbound fraction (Unbound, 3rd), the fifth unbound fraction (Unbound, 5th), and the elution fraction (Elu-Mix) from the mixture of four different MV preparations, respectively. Lane 10: the molecular weight marker. Lane 11: the crude MVs of P. gingivalis (Pg, Crude). Lane 14: the elution fraction from crude MVs of P. gingivalis only (Elu-Pg). The same volume (10 µl) was applied in each well of each PAGE gel. P. gingivalis FimA is denoted by an asterisk (*). N. meningitidis PorB is denoted by a dagger (†).

Discussion

In the present study, SDS-PAGE and EM analysis revealed the preferential binding of P. gingivalis MVs to SB-Epoxy. The SB-Epoxy-bound MVs were efficiently dissociated from the SBs by treatment with a buffer containing 2 M urea. However, neither low pH buffer nor high salt buffer affected binding. In EM analysis, we clearly observed MVs on the surface of the SB-Epoxy. We also observed dissociated MVs on the background behind the SB-Epoxy, probably because the electrostatic force driven by the cationic poly-L-lysine, pre-coated on the glass surface, attracted the MVs to the beads. These data suggest that the major force holding these macromolecules together is dependent on noncovalent bonds, but not merely electrostatic attractions. In general, hydrophobic groups in a protein tend to cluster in the interior of the molecule and are buried on the inside of the protein in the absence of urea. It is widely accepted that conformational change of a protein occurs in the presence of urea and that urea preferentially interacts with the hydrophobic groups. For SB-Epoxy, the epoxy coating treatment on the SBs might confer surface hydrophobicity on the SBs, due to the intrinsic hydrophobicity of the epoxy group (Table1). We therefore speculate that the binding between MVs and SB-Epoxy might be via hydrophobic interactions; urea’s action on hydrophobic interactions triggers a conformational change in proteins on the surface of MVs, eventually leading to dissociation of MVs from SB-Epoxy. However, a definitive conclusion regarding the interaction mechanisms between SBs and MVs or fimbriae requires further investigation. On the other hand, P. gingivalis fimbriae preferentially bound to SB-NH2 but not to SB-COOH or SB-Epoxy. Both MVs and fimbriae bound to SB-NH2 were eluted by addition of low pH buffer or high salt buffer (data not shown), suggesting that the binding of both fimbriae and MVs to SB-NH2 might be through electrostatic attraction.

For the competitive binding assays, we chose four Gram-negative bacterial species with different LPS structures. The structure of E. coli LPS, which has been most extensively studied, is composed of a hydrophobic domain known as lipid A, a core oligosaccharide, and a long O- polysaccharide [30]. P. gingivalis possesses two different types of LPS. One type, the anionic polysaccharide-LPS termed A-LPS, is a unique LPS containing a phosphorylated branched mannan [31]. N. meningitidis LPS has a shorter carbohydrate chain called lipooligosaccharide, which is antigenically and structurally similar to carbohydrates present in human glycosphingolipids [32]. P. aeruginosa has two different LPS moieties called A-band (a short chain and neutral in charge) and B-band (a longer chain and negatively charged) [33]. We also used the MVs from C. perfringens, as a representative species of Gram-positive bacteria that do not have an outer membrane. Consequently, MVs prepared from all species tested except P. gingivalis did not bind to SB-Epoxy at all (Fig. 5A–D and Fig. S2), suggesting that the preferential binding depends on a cell-surface property conserved among P. gingivalis strains. It is therefore interesting to compare the surface chemistries of MVs isolated from different species. In conclusion, the novel approach described here using SB-Epoxy provides more selective and time-saving purification of P. gingivalis MVs compared to other conventional methods, such as density gradient centrifugation. These findings also suggest that the SB-Epoxy-based technique may be clinically applicable for eliminating P. gingivalis MVs that are released into the extracellular milieu, such as in periodontal pockets or the circulatory system.

We confirmed that cell detachment was strongly induced by highly purified MVs (Fig. 4 and Video 1 and 2). On the other hand, cell detachment activity was still somewhat high in the fraction eluted using CHAPS, suggesting that the MVs might have enhanced the stability of gingipains and protected their activity from CHAPS treatment, in consistent with previous reports [34], [35]. Purified MVs at concentrations of greater than 5 µg/ml clearly caused cell detachment. In our previous studies, we estimated that recovery of MVs from two-day culture supernatant of ATCC 33277 was approximately 10 µg per 1 ml of culture supernatant, according to our calculation by the Bradford method [15]. Taken together, these data suggest that a physiologically relevant concentration of MVs may cause destruction of periodontal tissues.

Results from both SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1) and EM (Fig. 2) demonstrated that most of the fimbriae in the crude MVs were not associated with SB-Epoxy, as they were eventually detected in the unbound fractions. However, we still detected a FimA signal in the elution fraction even after extensive washing of the beads. Similar to this result, a FimA signal was also detected in the MVs purified by using a combination of ultracentrifugation and density gradient separation (data not shown). We therefore suggest that fimbriae tightly bind to MVs or that fimbriae is one of the major components of MVs.

In the binding assay using SB-NH2, the WB of FimA showed that free fimbriae in the starting materials were not collected in unbound fractions, unlike the case of SB-Epoxy. Furthermore, the amount of FimA protein in the elution fraction was much lower than that in the crude MV starting material. These findings suggest that fimbriae did not dissociate from SB-NH2 even after addition of elution buffer containing 2% SDS.

Several vaccine projects targeting P. gingivalis infection are on-going in different research groups. In the future, we expect P. gingivalis infection to be controlled by vaccine protection. P. gingivalis MVs are a feasible immunogen for use as a periodontal disease vaccine, because a range of virulence factors are enriched in the MVs [15], which have been shown to elicit strong mucosal immune responses in a mouse model [17]. However, MVs used in these mouse experiments were isolated by the conventional purification method, that is, free fimbriae in the MV preparation were not removed. In the present article, the novel purification method using SB-Epoxy could improve the purity of MVs thanks to removing fimbriae sheared from the bacterial surface. The fimA gene is heterogeneous, with at least six different fimbrial types of FimA (type I to V and Ib) known [36]–[38] and the antigenic molecular determinants of various types cross-react poorly or not at all [39], [40]. Therefore, whether fimbriae are good immunogens for a vaccine antigen is controversial; it may be appropriate to use “fimbriae-free” MVs as a vaccine immunogen. Further immunological studies using highly purified materials are needed to identify suitable vaccine immunogens to protect against P. gingivalis infection.

In the course of the competitive binding assay using mixtures of MV preparations from different species, we unexpectedly identified the neisserial PorB protein among the typical protein bands of P. gingivalis MVs in the elution fraction (Fig. 5A and S3). However, PorB was completely unable to bind to the SBs in the absence of P. gingivalis MVs (Fig. 5B and 3). Neisserial PorB is a unique porin protein in that it is capable of translocating vectorially into host cell membranes [41], [42] and mitochondria [43]. It is therefore expected that the neisserial PorB derived from the MVs can translocate to the MVs of P. gingivalis in a similar manner to the reported translocation into mitochondria or host cell membranes. However, it is notable that the binding of PorB to MVs occurred in 20 mM Tris-Cl buffer alone, i.e., in the absence of any energy sources such as ATP. It is unknown whether PorB can also translocate to MVs of other species besides P. gingivalis or to the outer membrane of live P. gingivalis. The physiological significance and the mechanism driving this phenomenon are also unknown. Further investigation is needed and the novel approach using SB-Epoxy to obtain ultrapurified P. gingivalis MVs may provide clues into as yet undiscovered molecular crosstalk among different bacterial species mediated by MVs.

Supporting Information

Binding to SB-Epoxy of MVs from different P. gingivalis strains. Shown are results of assays using crude MV preparations from the following four different P. gingivalis strains: FDC381, W50, YH522, and W83. Crude MVs from a single strain were incubated with the SB-Epoxy (Crude). Unbound components were collected in five washes (Unbound). For MVs of FDC381, W50, and YH522, the bound components were eventually eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer (Elu). For MVs of W83, the bound components were eluted twice with a mild denaturation buffer containing 2 M urea (Urea). After one wash with PBS, the components still bound to the SB-Epoxy (even after urea treatment) were treated with 4% CHAPS buffer (CHAPS). “MW” denotes the molecular weight marker. The same volume (10 µl) was applied to each well of each PAGE gel.

(TIF)

Binding to SB-Epoxy of MVs from two additional periodontopathic bacteria. Shown are results of assays using crude MV preparations from the following two species of periodontopathic bacteria: A. actinomycetemcomitans, strains Y4 and ATCC29522; and F. nucleatum, strains ATCC 23726 and #20. Crude MVs from a single strain was incubated with the SB-Epoxy (Crude). Unbound components were collected in five washes (Unbound). The bound components were eventually eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer (Elu). “MW” denotes the molecular weight marker. The sample volume (10 µl) was applied to each well of each PAGE gel.

(TIF)

Competitive binding assay using MVs of P. gingivalis and N. meningitidis . Shown are results of competitive binding assays of crude MVs of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 and N. meningitidis H44/76. (A–C) Crude MVs from a single strain of P. gingivalis (A) or N. meningitidis (B), and a mixture of P. gingivalis and N. meningitidis (C) were incubated with SB-Epoxy. Unbound components were collected in five washes with PBS and bound components were eventually eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Lanes denoted “1” are the starting material of crude MVs from conventional purification (Crude). Lanes denoted “2” are the first unbound fractions (Unbound, 1st). Lanes denoted “3” are the fifth unbound fractions (Unbound, 5th). Lanes denoted “4” are the elution fractions (Elu). The same sample volume (10 µl) was applied to each well of the PAGE gel. P. gingivalis FimA is denoted by an asterisk (*). N. meningitidis PorB is denoted by a dagger (†).

(TIF)

Morphological changes and movement of cells in the presence of MVs. Time-lapse observation of a monolayer of Ca9.22 cells was monitored by an optical microscope (Olympus) equipped with a CCD camera (Andor) in the presence of highly purified MVs isolated by the SB technique. The protein concentration of MVs used in the assay was 20 µg/ml. Images were taken at 30 sec/frame for 30 min immediately after addition of MVs suspended in Eagle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS). The constructed time-lapse images are shown at 100 msec/frame (300 times the original speed). The width of the image is 170 µm.

(AVI)

Morphological changes and movement of cells in the absence of MVs (a negative control). Time-lapse observation of a monolayer of Ca9.22 cells was monitored in EBSS in the absence of MVs. Images were taken at 30 sec/frame for 30 min. The constructed time-lapse images are shown at 100 msec/frame (300 times the original speed). The width of the image is 170 µm.

(AVI)

Acknowledgments

RN thanks Michiyo Kataoka and Noriko Saito for their technical assistance of electron microscopy analysis. RN also thanks Yoshimitsu Abiko, Yasuko Shibata, Nobushiro Hamada, Michael A. Curtis, Kazuyuki Ishihara and Hideyuki Takahashi for kindly providing precious materials.

Funding Statement

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Scientific Research of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (22791822 and 24659821); the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (H22 Iryo-Ippan-026); and The Naito Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA (2012) The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 10: 717–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schlein RA, Kudlick EM, Reindorf CA, Gregory J, Royal GC (1991) Toothbrushing and transient bacteremia in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 99: 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forner L, Larsen T, Kilian M, Holmstrup P (2006) Incidence of bacteremia after chewing, tooth brushing and scaling in individuals with periodontal inflammation. J Clin Periodontol 33: 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Rundek T, Boden-Albala B, Jacobs DR Jr, et al. (2005) Periodontal microbiota and carotid intima-media thickness: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST). Circulation 111: 576–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ishihara K, Nabuchi A, Ito R, Miyachi K, Kuramitsu HK, et al. (2004) Correlation between detection rates of periodontopathic bacterial DNA in coronary stenotic artery plaque [corrected] and in dental plaque samples. J Clin Microbiol 42: 1313–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dorn BR, Dunn WA Jr, Progulske-Fox A (1999) Invasion of human coronary artery cells by periodontal pathogens. Infect Immun 67: 5792–5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lalla E, Lamster IB, Feit M, Huang L, Spessot A, et al. (2000) Blockade of RAGE suppresses periodontitis-associated bone loss in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest 105: 1117–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li L, Messas E, Batista EL Jr, Levine RA, Amar S (2002) Porphyromonas gingivalis infection accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in a heterozygous apolipoprotein E-deficient murine model. Circulation 105: 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. MacDonald IA, Kuehn MJ (2012) Offense and defense: microbial membrane vesicles play both ways. Res Microbiol 163: 607–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wai SN, Lindmark B, Soderblom T, Takade A, Westermark M, et al. (2003) Vesicle-mediated export and assembly of pore-forming oligomers of the enterobacterial ClyA cytotoxin. Cell 115: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Balsalobre C, Silvan JM, Berglund S, Mizunoe Y, Uhlin BE, et al. (2006) Release of the type I secreted alpha-haemolysin via outer membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli . Mol Microbiol 59: 99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kouokam JC, Wai SN, Fallman M, Dobrindt U, Hacker J, et al. (2006) Active cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 associated with outer membrane vesicles from uropathogenic Escherichia coli . Infect Immun 74: 2022–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kesty NC, Mason KM, Reedy M, Miller SE, Kuehn MJ (2004) Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vesicles target toxin delivery into mammalian cells. EMBO J 23: 4538–4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amano A, Takeuchi H, Furuta N (2010) Outer membrane vesicles function as offensive weapons in host-parasite interactions. Microbes Infect 12: 791–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakao R, Takashiba S, Kosono S, Yoshida M, Watanabe H, et al. (2014) Effect of Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles on gingipain-mediated detachment of cultured oral epithelial cells and immune responses. Microbes Infect 16: 6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holst J, Martin D, Arnold R, Huergo CC, Oster P, et al. (2009) Properties and clinical performance of vaccines containing outer membrane vesicles from Neisseria meningitidis . Vaccine 27 Suppl 2B3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakao R, Hasegawa H, Ochiai K, Takashiba S, Ainai A, et al. (2011) Outer membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis elicit a mucosal immune response. PLoS One 6: e26163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grenier D, Mayrand D (1987) Functional characterization of extracellular vesicles produced by Bacteroides gingivalis . Infect Immun 55: 111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Devoe IW, Gilchrist JE (1973) Release of endotoxin in the form of cell wall blebs during in vitro growth of Neisseria meningitidis . J Exp Med 138: 1156–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horstman AL, Kuehn MJ (2000) Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli secretes active heat-labile enterotoxin via outer membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem 275: 12489–12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bauman SJ, Kuehn MJ (2006) Purification of outer membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their activation of an IL-8 response. Microbes Infect 8: 2400–2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen YY, Peng B, Yang Q, Glew MD, Veith PD, et al. (2011) The outer membrane protein LptO is essential for the O-deacylation of LPS and the co-ordinated secretion and attachment of A-LPS and CTD proteins in Porphyromonas gingivalis . Mol Microbiol 79: 1380–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haurat MF, Aduse-Opoku J, Rangarajan M, Dorobantu L, Gray MR, et al. (2011) Selective sorting of cargo proteins into bacterial membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem 286: 1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nakao R, Senpuku H, Watanabe H (2006) Porphyromonas gingivalis galE is involved in lipopolysaccharide O-antigen synthesis and biofilm formation. Infect Immun 74: 6145–6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holten E (1979) Serotypes of Neisseria meningitidis isolated from patients in Norway during the first six months of 1978. J Clin Microbiol 9: 186–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Curtis MA, Thickett A, Slaney JM, Rangarajan M, Aduse-Opoku J, et al. (1999) Variable carbohydrate modifications to the catalytic chains of the RgpA and RgpB proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. Infect Immun 67: 3816–3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abiko Y, Hayakawa M, Aoki H, Kikuchi T, Shimatake H, et al. (1990) Cloning of a Bacteroides gingivalis outer membrane protein gene in Escherichia coli. Arch Oral Biol 35: 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kimura Y (1978) [Studies on lactate dehydrogenase isoenzymes in a cell line (Ca 9-22) derived from carcinoma of the gingiva (author's transl)]. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi 45: 20–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rangarajan M, Aduse-Opoku J, Paramonov N, Hashim A, Bostanci N, et al. (2008) Identification of a second lipopolysaccharide in Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. J Bacteriol 190: 2920–2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raetz CR, Whitfield C (2002) Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem 71: 635–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paramonov N, Rangarajan M, Hashim A, Gallagher A, Aduse-Opoku J, et al. (2005) Structural analysis of a novel anionic polysaccharide from Porphyromonas gingivalis strain W50 related to Arg-gingipain glycans. Mol Microbiol 58: 847–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mandrell RE, Griffiss JM, Macher BA (1988) Lipooligosaccharides (LOS) of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis have components that are immunochemically similar to precursors of human blood group antigens. Carbohydrate sequence specificity of the mouse monoclonal antibodies that recognize crossreacting antigens on LOS and human erythrocytes. J Exp Med 168: 107–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rivera M, Bryan LE, Hancock RE, McGroarty EJ (1988) Heterogeneity of lipopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: analysis of lipopolysaccharide chain length. J Bacteriol 170: 512–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aldick T, Bielaszewska M, Uhlin BE, Humpf HU, Wai SN, et al. (2009) Vesicular stabilization and activity augmentation of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli haemolysin. Mol Microbiol 71: 1496–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van de Waterbeemd B, Zomer G, Kaaijk P, Ruiterkamp N, Wijffels RH, et al. (2013) Improved production process for native outer membrane vesicle vaccine against Neisseria meningitidis . PLoS One 8: e65157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakagawa I, Amano A, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Endoh N, Morisaki I, et al. (2002) Identification of a new variant of fimA gene of Porphyromonas gingivalis and its distribution in adults and disabled populations with periodontitis. J Periodontal Res 37: 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakagawa I, Amano A, Kimura RK, Nakamura T, Kawabata S, et al. (2000) Distribution and molecular characterization of Porphyromonas gingivalis carrying a new type of fimA gene. J Clin Microbiol 38: 1909–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Amano A, Nakagawa I, Kataoka K, Morisaki I, Hamada S (1999) Distribution of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains with fimA genotypes in periodontitis patients. J Clin Microbiol 37: 1426–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fan Q, Sims TJ, Nakagawa T, Page RC (2000) Antigenic cross-reactivity among Porphyromonas gingivalis serotypes. Oral Microbiol Immunol 15: 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fan Q, Sims T, Sojar H, Genco R, Page RC (2001) Fimbriae of Porphyromonas gingivalis induce opsonic antibodies that significantly enhance phagocytosis and killing by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Oral Microbiol Immunol 16: 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rudel T, Schmid A, Benz R, Kolb HA, Lang F, et al. (1996) Modulation of Neisseria porin (PorB) by cytosolic ATP/GTP of target cells: parallels between pathogen accommodation and mitochondrial endosymbiosis. Cell 85: 391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weel JF, Hopman CT, van Putten JP (1991) Bacterial entry and intracellular processing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in epithelial cells: immunomorphological evidence for alterations in the major outer membrane protein P.IB. J Exp Med 174: 705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Massari P, Ho Y, Wetzler LM (2000) Neisseria meningitidis porin PorB interacts with mitochondria and protects cells from apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 9070–9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Binding to SB-Epoxy of MVs from different P. gingivalis strains. Shown are results of assays using crude MV preparations from the following four different P. gingivalis strains: FDC381, W50, YH522, and W83. Crude MVs from a single strain were incubated with the SB-Epoxy (Crude). Unbound components were collected in five washes (Unbound). For MVs of FDC381, W50, and YH522, the bound components were eventually eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer (Elu). For MVs of W83, the bound components were eluted twice with a mild denaturation buffer containing 2 M urea (Urea). After one wash with PBS, the components still bound to the SB-Epoxy (even after urea treatment) were treated with 4% CHAPS buffer (CHAPS). “MW” denotes the molecular weight marker. The same volume (10 µl) was applied to each well of each PAGE gel.

(TIF)

Binding to SB-Epoxy of MVs from two additional periodontopathic bacteria. Shown are results of assays using crude MV preparations from the following two species of periodontopathic bacteria: A. actinomycetemcomitans, strains Y4 and ATCC29522; and F. nucleatum, strains ATCC 23726 and #20. Crude MVs from a single strain was incubated with the SB-Epoxy (Crude). Unbound components were collected in five washes (Unbound). The bound components were eventually eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer (Elu). “MW” denotes the molecular weight marker. The sample volume (10 µl) was applied to each well of each PAGE gel.

(TIF)

Competitive binding assay using MVs of P. gingivalis and N. meningitidis . Shown are results of competitive binding assays of crude MVs of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 and N. meningitidis H44/76. (A–C) Crude MVs from a single strain of P. gingivalis (A) or N. meningitidis (B), and a mixture of P. gingivalis and N. meningitidis (C) were incubated with SB-Epoxy. Unbound components were collected in five washes with PBS and bound components were eventually eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Lanes denoted “1” are the starting material of crude MVs from conventional purification (Crude). Lanes denoted “2” are the first unbound fractions (Unbound, 1st). Lanes denoted “3” are the fifth unbound fractions (Unbound, 5th). Lanes denoted “4” are the elution fractions (Elu). The same sample volume (10 µl) was applied to each well of the PAGE gel. P. gingivalis FimA is denoted by an asterisk (*). N. meningitidis PorB is denoted by a dagger (†).

(TIF)

Morphological changes and movement of cells in the presence of MVs. Time-lapse observation of a monolayer of Ca9.22 cells was monitored by an optical microscope (Olympus) equipped with a CCD camera (Andor) in the presence of highly purified MVs isolated by the SB technique. The protein concentration of MVs used in the assay was 20 µg/ml. Images were taken at 30 sec/frame for 30 min immediately after addition of MVs suspended in Eagle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS). The constructed time-lapse images are shown at 100 msec/frame (300 times the original speed). The width of the image is 170 µm.

(AVI)

Morphological changes and movement of cells in the absence of MVs (a negative control). Time-lapse observation of a monolayer of Ca9.22 cells was monitored in EBSS in the absence of MVs. Images were taken at 30 sec/frame for 30 min. The constructed time-lapse images are shown at 100 msec/frame (300 times the original speed). The width of the image is 170 µm.

(AVI)