Abstract

As an integrated prepaid health care system, Kaiser Permanente (KP) is in a unique position to demonstrate that affordability in health care can be achieved by disease prevention. During the past decade, KP has significantly improved the quality care outcomes of its members with preventable diseases. However, because of an increase in the incidence of preventable disease, and the potential long-term and short-term costs associated with the treatment of preventable disease, KP has developed a new strategy called Total Health to meet the current and future needs of its patients. Total Health means healthy people in healthy communities. KP’s strategic vision is to be a leader in Total Health by making lives better. KP hopes to make lives better by 1) measuring vital signs of health, 2) promoting healthy behaviors, 3) monitoring disease incidence, 4) spreading leading practices, and 5) creating healthy environments with our community partners. Best practices, spread to the communities we serve, will make health care more affordable, prevent preventable diseases, and save lives.

Introduction

Since its inception almost 70 years ago, Kaiser Permanente (KP) has reversed the economic incentive in medicine by focusing on prevention. Henry J Kaiser’s workers paid for their medical care in advance, and the healthier that KP’s physician founder, Sidney Garfield, MD, could keep Mr Kaiser’s employees, the more productive they would be on the job. Dr Garfield reportedly even walked through the construction sites pounding down nails so that workers wouldn’t step on them and require medical treatment. Today, KP’s emphasis on health maintenance and disease prevention instead of traditional fee-for-service “sick care” has evolved into the concept of Total Health: a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being for all people.

KP and the Care Management Institute have developed a Total Health strategy geared to supporting members, and communities—including KP’s own employees—where they live, learn, labor, and play.1 KP has adopted innovative approaches to preventive care and wellness programs by involving schools, businesses, governmental agencies, faith-based institutions, clinics, hospitals, and communities in the Total Health framework. Reducing the rate of obesity and preventing preventable disease is a cornerstone of this framework. Total Health means healthy people in healthy communities.

Marshal Ganz, senior lecturer in public policy at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, teaches that values are transformed into action through use of public narrative.2 The public narrative engages the head and the heart; it not only teaches how one ought to act but also inspires one to do so. The public narrative, according to Ganz, is a leadership art composed of three elements: the story of now, the story of self, and the story of us. The public narrative is a great public story designed to help improve society by identifying opportunities for change (the story of now), examples of change (the story of self), and best practices that can be spread to improve society (the story of us).

The Story of Now

Martin Luther King once said: “We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now.”3 For our country, the “story of now” would include a plot featuring skyrocketing health care costs, payers pressuring health care providers to make care more affordable, and businesses struggling to remain profitable in the wake of mounting health care expenditures.2

Preventing disease remains a key strategy to improving quality and lowering cost. In the US, we spend almost $3.5 trillion on health care.4 One third of health care costs goes toward treating preventable disease. By definition, preventable diseases are preventable yet we spend less than 10% of health care dollars on prevention. Preventable diseases include obesity, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. However, obesity threatens the promise of a healthy nation because it can trigger prediabetes, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease, and cancer.

One-third of American adults and 17% of children are obese.5 Obesity is a major cause of death and disability.6 The estimated annual cost of obesity-related illness based on data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey for 2000–2005 is $190 billion, or nearly 21% of annual medical spending in the US.6,7 Obesity predisposes adults and children to type 2 diabetes.8 Unless Americans change current behavior, one-third of children born today will develop type 2 diabetes in their lifetime.9 At current projections, children born today may have a life expectancy that is shorter than that of their parents unless the rate of obesity is abated.10 Winning the war on obesity is critical to having a healthy America (see Sidebar: Lifestyle Management and Diabetes Prevention).

Lifestyle Management and Diabetes Prevention.

The adoption of sound nutrition and exercise programs can have a dramatic impact on the health—and the wealth—of the nation. This is particularly true when it comes to preventing diabetes. Increasing awareness and risk stratification of individuals with prediabetes may help physicians understand potential interventions that may help decrease the percentage of patients in their panels who develop diabetes. Untreated, 37% of the individuals with prediabetes may develop diabetes in 4 years. Lifestyle intervention may decrease the percentage of prediabetes patients who develop diabetes to 20%.1

In 2012, Health Affairs published an article looking at the economics of screening and treating individuals with prediabetes.2 Using a simulation model, the authors projected the costs and benefits of a nationwide community-based lifestyle intervention program for preventing type 2 diabetes. In the hypothetical intervention program, nearly 100 million Americans ages 18 to 84 years would be screened over the next 25 years and nearly 23 million of those would have prediabetes. The researchers projected that over the 25-year simulation period the hypothetical program would prevent or delay 885,000 new cases of type 2 diabetes and result in a gain of 952,000 life-years. The researchers projected that the return on investment for implementation of such a program would result in $29.8 billion in downstream savings.2

References

- 1.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 7;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhuo X, Zhang P, Gregg EW, et al. A nationwide community-based lifestyle program could delay or prevent type 2 diabetes cases and save $5.7 billion in 25 years. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012 Jan;31(1):50–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1115. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The Story of Self

KP’s mission is to provide high-quality care at an affordable cost. During the past few years, we have realized that most preventable disease can be successfully treated in an integrated health care system. However, most of our resources are still focused on treatment of patients with chronic preventable disease and not prevention. The Total Health strategy is to shift our paradigm from disease treatment to disease prevention. KP’s strategic vision is to be a leader in Total Health by making lives better through disease prevention. We hope to make lives better by

measuring vital signs of health

promoting healthy behaviors

monitoring disease incidence

spreading leading practices

creating healthy environments.

Measuring Vital Signs of Health

For several years, KP has been measuring vital signs of health for everyone who comes into the clinic. Thus far, these measurements include body mass index and physical activity. The measures are placed into the electronic medical record, which is available for members to view on their personal Web site (www.kp.org).

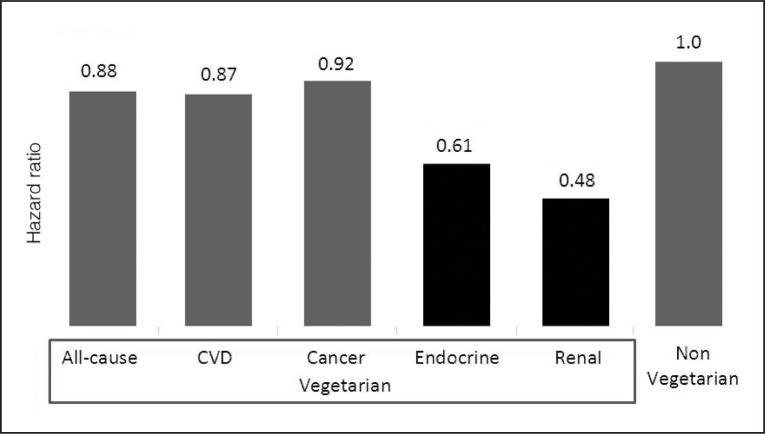

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), healthy eating and active living are 2 potential interventions to slow down the obesity epidemic and prevent disease.11,12 For this reason, KP determined that measures for health should include physical activity and nutrition. The ideal measure for physical activity is set at a minimum of 150 minutes per week as outlined by the National Institute of Health in 2008.13 A proposed vital sign measure to indicate healthy eating is the number of days per week that an individual consumes at least 5 servings of fruits or vegetables. Recent data from the literature suggests that a plant-based diet (more fruits and vegetables per day) can significantly reduce the risk of cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and renal disease (Figure 1).14,15

Figure 1.

Mortality hazard risk ratio of vegetarians versus nonvegetarians, based upon the Adventist Health Study 2.1

CVD = cardiovascular disease.

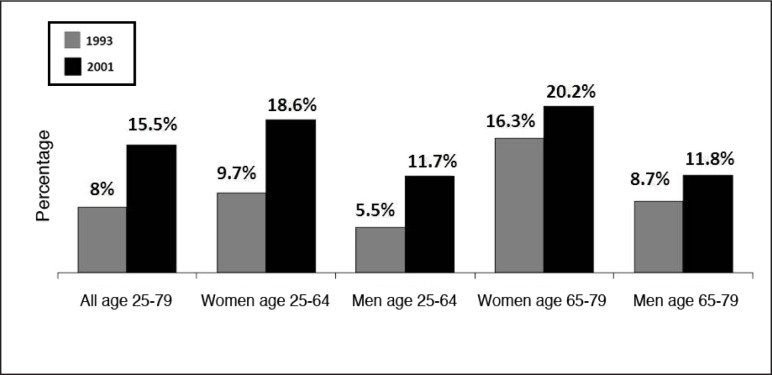

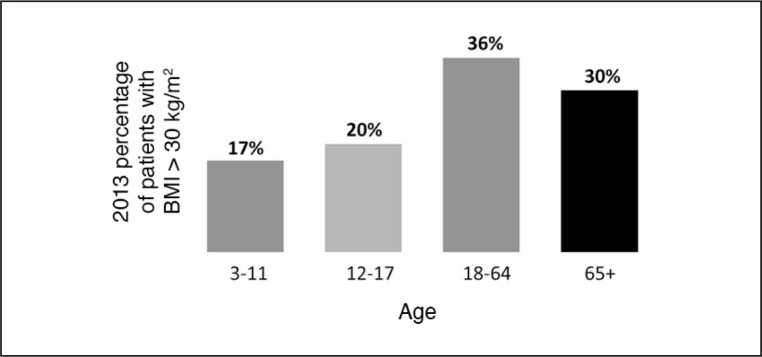

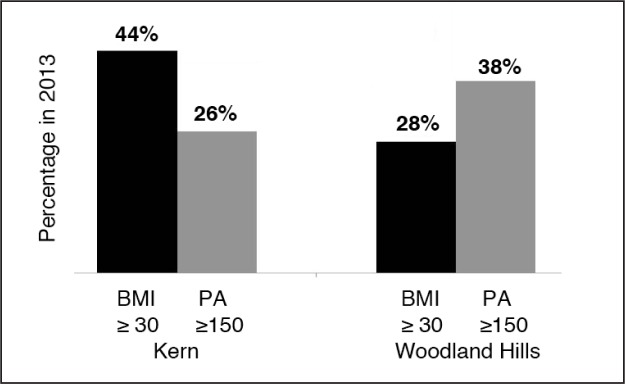

Data from KP Southern California show that about one-third of adult members are obese (Figure 2) and that there is a strong relationship between members’ high obesity rates and lack of exercise (Figure 3). Recent survey data reported from KP Northern California show that less than 20% of members consume at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day (Figure 4). More women consume at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day than men, and the percentage of women and men who consume at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day appears to be increasing over time. The vital signs of health data mentioned above suggests that we have an opportunity to improve the health of our members by increasing the percentage of patients who are physically active and eat a healthy diet.

Figure 2.

Kaiser Permanente Southern California obesity rates for 2013.

Figure 3.

Kaiser Permanente Southern California Percentage of obesity and physical activity rates (y-axis) for Kern and Woodland Hills Service Areas (x-axis).

BMI ≥ 30 = body mass index greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2; PA ≥ 150 = physical activity greater than or equal to 150 minutes per week.

Figure 4.

Percentage of patients who consume at least five servings of fruits and vegetables per day (by survey) in Kaiser Permanente Northern California in 1993 compared with 2011.

Promoting Healthy Behaviors

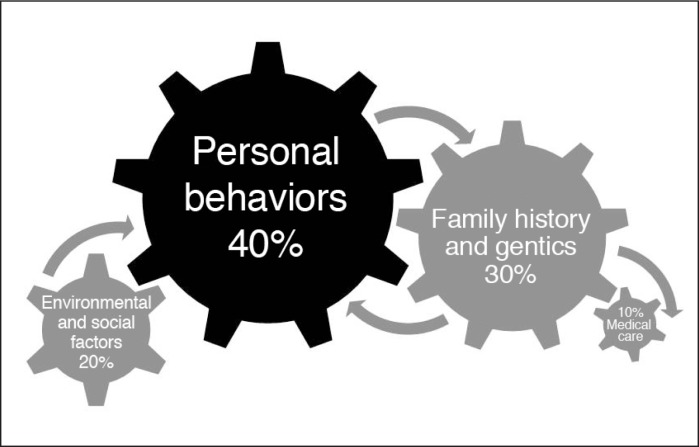

The many factors shaping health are intricately related. Factors that contribute to premature death include behavior, genetics, environment, and medical care.11,16 Of these four determinants, personal behavior has the most influence and medical care the least (Figure 5). Therefore, a focus on personal behavior change offers the best chance of preventing disease and lowering obesity rates.

Figure 5.

Factors that shape health. Modifiable factors that contribute to premature death include medical care, family history, genetics, environmental factors, social factors, and personal behavior. The number one modifiable factor is personal behavior.1

KP uses various behavior change methods. One particularly successful behavior change model has been developed by BJ Fogg.17 His model states that three elements must converge at the same moment for a behavior change to occur: motivation, ability, and trigger (see Sidebar: Fogg Behavior Model). When a behavior change does not occur, at least one of those three elements is missing. This persuasive design model is based on the psychology of human behavior. It explains how finding the right motivation, making change simple to do, and employing effective triggers—and doing all three simultaneously—can enact desired behavior change.

Fogg Behavior Model.

How to get people to eat nutritiously, exercise, or stop smoking? As any physician or health educator will tell you, knowledge alone is seldom sufficient to change behavior. One scientist who has been studying human psychology and the art of persuasion is BJ Fogg of the Stanford University Persuasive Technology Lab. The Fogg Behavior Model (FBM) provides a structured way to think about the factors that must be enacted to change behavior.1 The FBM identifies three factors that must be present at the same instant for a target behavior to happen:

Sufficient motivation

Sufficient ability to perform the behavior change (ie, the behavior change must be simple to perform)

Effective triggers to perform the behavior.

There is a relationship between the degree of motivation and the level of ability—they are tradeoffs of a sort, says Fogg.1 So the goal is to move the individual to a higher position in the FBM landscape by increasing either motivation or ability (making behavior simpler). The FBM model has three core motivators that are dualistic in nature: pleasure/pain; hope/fear; and social acceptance/ rejection. Social media such as Facebook, for example, get their motivation from people’s desire to be socially accepted.

Increasing the user’s ability to perform a behavior by making it easy to do is the next key factor. Fogg1 contends that merely teaching and training people are not sufficient because human adults are “fundamentally lazy.” Therefore, simplicity is the key to increasing a user’s ability. A good example is one-click shopping at Amazon.com, Fogg notes. The trigger is the third element to the FBM. The trigger must be the right one and also delivered at the right moment—that is, when both motivation and ability are at a level where the behavior can be activated (the behavior activation threshold). If a person is below the activation threshold, then a trigger will not lead to the target behavior. This explains why online spam and pop-up ads—meant to be persuasive triggers—are often ineffective: The user has insufficient motivation/ability to do what the trigger (pop-up, spam, etc) says, according to Fogg.

Fogg1 believes that his model can create a shared frame of reference for project teams thinking about behavior change. The FBM also can help people channel their energies more efficiently: If teams realize that motivation is the lacking factor, for example, then efforts can be focused on that aspect of the design.

Reference

- 1.Fogg BJ. A behavior model for persuasive design [Internet] Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University; 2013. [cited 2013 Dec 18]. Available from: http://bjfogg.com/fbm_files/page4_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Finding solutions to the epidemic of obesity and other preventable diseases is challenging to physicians and health care systems. For example, a recent study explains why it may be so difficult to treat obesity.18 Research suggests that losing weight may not be a neutral event. It appears the body wants to be at a certain weight and will try to get back to that set point after weight loss.

For this study,18 researchers recruited people who weighed an average of 209 pounds. Investigators measured participants’ hormone levels and assessed their hunger and appetites after eating a standardized meal. The dieters then spent 10 weeks on a very low-calorie diet intended to make them lose 10% of their body weight. After weight loss, hormone levels had changed in a way that increased the participants’ appetites. Participants were then given diets intended to help them maintain their weight loss. A year after the subjects had lost the weight, however, the researchers found that participants were gaining weight—and certain hormone levels, like leptin, still had not returned to normal.18

Leptin, which is a hormone that tells the brain how much body fat is present, fell by two-thirds immediately after the subjects lost weight. When leptin falls, appetite increases and metabolism slows. A slow metabolism makes it harder to lose weight even with exercise. A year after the weight-loss diet, leptin levels were still depressed, but levels had increased in participants who had gained weight on the maintenance diet.18

KP has developed two strategies to reduce obesity rates:

helping children obtain a healthy, nonobese set point and

encouraging obese patients to reset their obesity set point.

The first strategy is to prevent obesity before a baby is even born. Interventions for this strategy focus on helping expectant mothers maintain a healthy weight during pregnancy and then educating new parents to develop home environments that encourage healthy eating and active living for their infants. The second strategy focuses on helping the obese patient lose weight. However, to adjust the set point, weight loss in obese patients involves lifestyle modification that includes healthy eating and active living, not just a quick dietary intervention. The success of these interventions depends on changing the biologic, behavioral, and environmental factors that give rise to obesity. This strategy focuses on lifestyle modification and not a specific diet. Once the long-term behavior is changed we may be able to readjust the set point.18–20

Monitoring Disease Incidence

Disease incidence is the principle measure of impact of a disease. Disease incidence data usually represent only a fraction of cases but are useful to monitor trends. Monitoring the incidence of preventable disease in health care is currently by using existing national data sets like the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) (www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement.aspx). HEDIS is a tool used by most health plans in America to measure performance on important dimensions of care and services. Because so many plans use this data set, it is possible to compare the performance of health plans on an “apples-to-apples” basis. This is a valuable resource for health planners, practitioners, and researchers interested in the occurrence of preventable disease. Monitoring the health status of our communities allows us to study the effects of targeted behavior interventions on improving vital signs of health and disease incidence and to identify best practices.

Spreading Leading Practices

Best practices take time to spread passively, at times contributing to suboptimal results in health care. Managed diffusion, often referred to as “spread,” may hasten broad-scale implementation of best practices. Once we can monitor vital signs of health for all patients we can start to develop interventions to improve vital signs of health. For example, KP Southern California has been measuring vital signs for health for many years. Results have shown that despite encouragement from physicians, exercise rates among members have not increased. Health education classes and social networking have been shown to increase exercise rates in subsets of our patients. Therefore, we may not be able to improve vital signs of health without the help of the people who surround the people we are trying to help. To accomplish our goal, we may need to improve the health behavior of the communities where our patients eat, live, learn, work, and play.

Creating Healthy Environments

The IOM has outlined five community areas essential to lowering obesity rates and preventing disease.12 The key areas include physical activity, food and beverages, marketing, health care and workplace, and schools. Five IOM solutions to help prevent disease and reduce the obesity rate in communities are as follows: integrate physical activity into all aspects of daily life, activate employees and health care professions, market what matters, make healthy foods available everywhere, and strengthen schools as the heart of health. KP has developed programs to address the IOM’s five essential areas of improvement and five solutions. These are outlined in Table 1 and discussed below.

Table 1.

Behavior change and solutions

| Behaviors | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Only 15% of adults eat at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day 40% of children eat fast food daily Only 30% of adults exercise at least 150 minutes per week |

Healthy eating Active living Active people |

| Children spend on average about 7.5 hours per day in front of a screen | Marketing Weight of the Nation Activate communities |

| Of a child’s waking hours, 33% are spent at school | School Activate teachers and students |

| Of an adult’s life, 25% is spent at work | Healthy workforce Healthy work place Activate health care providers |

The Story of Us

The “story of us” involves KP’s engagement with employees, members, the workforce, schools, and the community and nation writ large. KP’s Total Health strategy leverages collaboration and resource sharing to build healthy communities. Employees who have been motivated to adopt healthy lifestyles are encouraged to become “ambassadors,” modeling their own healthy changes to the broader community. In this way, improvements in health behaviors can be sustained over the years.

Healthy Eating Active Living

Healthy Eating Active Living (http://info.kaiserpermanente.org/communitybenefit/html/our_work/global/our_work_3_b.html) focuses on policies and programs that promote healthy eating and active living at home, at work, in schools, and in the community. The thematic focus is to prevent disease and reduce obesity rates through good nutrition and physical activity. As part of the program, KP collaborates with community partners to develop a systematic, population-based approach that addresses the root causes of disease and sustains improvements over time. Key interventions that should help prevent disease include:

Decrease daily calorie consumption (especially of sugar-sweetened beverages)

Increase consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables

Increase physical activity in our communities, schools, and work sites.

The Healthy Eating Active Living Initiative

Examples include Farmers Markets, KP Walk, Every Body Walk, and Thriving Schools. These are discussed below.

Farmers Markets, Fresh Works, and Wholesome Wave

KP has fostered relationships with farmers to sell their fresh fruit and produce at markets that take place at KP Medical Centers (https://healthy.kaiserpermanente.org/static/health/en-us/landing_pages/farmersmarkets/index.htm). These markets have become popular and are spreading throughout the organization. KP also has collaborated with nutrition programs Fresh Works (www.cafreshworks.com) and Wholesome Wave (http://wholesomewave.org). Fresh Works is a loan fund program that brings healthy food to retail outlets in underserved communities. Wholesome Wave is a coupon program that reimburses farmers markets for allowing recipients of food stamps to double the value for a certain amount of federal food benefits spent on fresh produce sold at the markets. This program encourages the purchase of healthy fruits and vegetables at the markets as opposed to the recipient spending the same dollar on low-nutrient fast food alternatives.

KP Walk and Every Body Walk

In 1996, the US Department of Health and Human Services published Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General.21 This report supports the empowering notion that some exercise is better than none, and any approach to encourage activity will have positive health benefits. On the basis of this report, two programs have been developed to encourage physical activity.

KP Walk—The KP Walk program (www.kpwalk.com) was designed to encourage employees, members, and communities to get their exercise by walking. Medical research shows that walking 30 minutes a day, five days a week, can prevent the onset and can help manage chronic diseases.

Every Body Walk—Every Body Walk (www.everybodywalk.org) provides news and resources on walking, health information, and walking maps. The Web site helps patients find walking groups and provides a forum for sharing stories about individual experiences with walking.

Marketing: The Weight of the Nation

In May 2012, KP and the cable network HBO launched The Weight of the Nation in collaboration with the IOM, the National Institutes of Health, the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This HBO documentary is available at no charge on the HBO Web site (http://theweightofthenation.hbo.com). The documentary features evidence-based data with personal narratives that illustrate the health consequences of obesity and excess weight. In addition, the documentary showcases strategies that work on an individual and community level. The documentary spearheads a public health campaign.

Workforce: Healthy Workplace and HealthWorks

KP’s workforce wellness strategy pursues clear guidelines in the following areas:

Healthy eating, including catered food, food labeling in cafeterias and vending machines, and on-site food retail outlets

Healthy physical environments, such as accessible stairwells for walking and buildings designed to promote mental and physical health

Healthy activity at work, including time and space for physical activities

Activating clinicians to work with employer groups to implement lifestyle management programs into the workplace environment.

Healthy Workplace—Healthy Workplace (https://epf.kp.org/wps/portal/hr/kpme/healthyworkforce) focuses on improving the health and well-being of all KP employees. The program offers more than 250 services aimed at promoting and enhancing the health and well-being of KP’s 190,000 employees and 17,000 physicians. Healthy Workplace leverages the clinical excellence and health-promotion expertise of the Health Plan and Medical Groups to provide both on-site and online services, including a range of programs from cholesterol and blood-pressure screening to cooking, weight-loss, exercise, and smoking-cessation classes and programs.

Offerings encompass six major categories: healthy eating, physical activity, emotional health and wellness, prevention, healthy workplace, and healthy community expertise and resources.

HealthWorks—KP’s HealthWorks program (http://internal.or.kp.org/custserv/pdf_11/healthworks.pdf) is designed to help purchasers develop healthy work environments for their employees. HealthWorks offers on-site and online healthy lifestyle programs that support employees in reaching health goals, including quitting smoking, losing weight, reducing stress, eating healthier, sleeping better, and managing a chronic condition.

Schools as the “Heart of Health”: Thriving Schools Web Site and Fire Up Your Feet Program

Research has shown that school interventions can have population-level impacts on the future health of communities. The IOM recently identified the need to strengthen schools as the “heart of health.”12 Better health through changes such as increased physical activity and a decreased availability of unhealthy foods and beverages can help students and school employees perform better. Regular physical activity also can reduce the risk of developing obesity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes as an adult.12

Thriving Schools Web Site—The Thriving Schools Web site (http://thrivingschools.kaiserpermanente.org) serves as a starting point toward healthier schools, offering free, ready-to-use tools and resources. It provides a place to share ideas and success stories and to spark creative innovation and change that can strengthen the health and well-being of schools.

The Fire Up Your Feet Program—This innovative program (http://fireupyourfeet.org) helps teachers, parents, and administrators get students moving before, during, and after the school day. The program also helps schools conduct healthy fundraisers that promote walking, biking, and other types of physical activity.

Conclusion

KP is leveraging the organization’s intellectual, technical, financial, and human assets—and working through an expanding network of public and private partnerships—to help its members, employees, and communities achieve their Total Health potential. Healthy eating and active living programs geared to battling obesity and preventing disease are an integral component of this multipronged initiative. Marshal Ganz teaches that the key to a successful social movement is a good public story that includes three elements: a story of now, a story of self, and a story of us.2

Total Health is a great public story. The story of now is a story of our health care in crisis. The story of self is a story of the innovative work being done within KP that allows us to measure and evaluate vital signs of health. Finally, the story of us is a story of our ability to spread leading practice to our patients and our communities. Best practices will make health care more affordable, prevent preventable diseases, and save lives.

Acknowledgments

Mary Corrado, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabaté J, et al. Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Jul 8;173(13):1230–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473.

Schroeder SA. We can do better—improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007 Sep 20;357(12):1221–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073350. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa073350.

References

- 1.Wallace P. The Care Management Institute: making the right thing easier to do. Perm J. 2005;9(2):56–7. doi: 10.7812/tpp/05-026. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7812/TPP/05-025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganz M. Building strategic capacity or how David sometimes can win [Internet] Cambridge, MA: Progressive Strategy Studies Project; 2006. May 1, [cited 2013 Dec 18]. Available from: http://progressive-strategy2.blogspot.com/2006/05/marshall-ganz-seminar-summary.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.King ML., Jr . I have a dream [speech] [Internet] Atlanta, GA: The King Center; 1963. Aug 28, [cited 2014 Feb 17]. Available from: www.thekingcenter.org/archive/document/i-have-dream-2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keehan S, Sisko A, Truffler C, et al. National Health Expenditure Accounts Projections Team. Health spending projections through 2017: the baby-boom generation is coming to Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008 Mar-Apr;27(2):w145–55. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w145. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013 Jan 2;309(1):71–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.113905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):219–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diabetes public health resource [Internet] Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; updated 2013 Sep 25[cited 2013 Apr 19]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/diabetes/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of pre-diabetes and its association with clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors and hyperinsulinemia among US adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009 Feb;32(2):342–7. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1128. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc08-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003 Oct 8;290(14):1884–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. New Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 17;352(11):1138–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr043743. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr043743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroeder SA. Shattuck Lecture. We can do better—improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007 Sep 20;357(12):1221–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073350. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa073350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: solving the weight of the nation [Internet] Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2012. May 8, [2013 Apr 19]. Available from: www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/Accelerating-Progress-in-Obesity-Prevention.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Recommendation for physical activity [Internet] Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2011. Sep 26, [cited 2014 Jan 18]. Available from: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/phys/recommend.html. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabaté J, et al. Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Jul 8;173(13):1230–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, Bartolotto C. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013 Spring;17(2):61–6. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-085. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993 Nov 10;270(18):2207–12. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.270.18.2207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fogg BJ. A behavior model for persuasive design [Internet] Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University; 2013. [cited 2013 Dec 18]. Available from: http://bjfogg.com/fbm_files/page4_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct 27;365(17):1597–1604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105816. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels SR, Arnett DK, Eckel RH, et al. Overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation. 2005 Apr 19;111(15):1999–2012. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161369.71722.10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000161369.71722.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 7;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CDC Prevention Guidelines Database (Archive) [Internet] Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. Jul 13, [cited 2014 Jan 18]. Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/prevguid/m0042984/m0042984.asp. [Google Scholar]