Abstract

Faith, Activity and Nutrition (FAN), a community-based participatory research project in African American churches, aimed to increase congregant physical activity and healthy eating. The Health-Promoting Church framework, developed collaboratively with faith-based partners, guided the intervention and a comprehensive process evaluation. The Health-Promoting Church components related to healthy eating and physical activity were getting the message out, opportunities, pastor support, and organizational policy. There was no evidence for sequential mediation for any of the healthy eating components. These results illustrate the complexity of systems change within organizational settings and the importance of conducting process evaluation. The FAN intervention resulted in increased implementation for all physical activity and most healthy eating components. Mediation analyses revealed no direct association between implementation and increased physical activity; rather, sequential mediation analysis showed that implementation of physical activity messages was associated with improved self-efficacy at the church level, which was associated with increased physical activity.

Keywords: Process evaluation, Implementation, Mediation analysis, Faith-based setting

1. Introduction

The Faith, Activity, and Nutrition (FAN) program was a participatory research intervention that aimed to increase physical activity and improve dietary practices in African American churches (Wilcox et al., 2010). Participants in intervention compared to control churches showed modest but significantly larger increases in self-reported leisure-time physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption in a group randomized trial (Wilcox et al., 2013). Unique elements of FAN included a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach in a faith-based setting with extensive stakeholder involvement from prefunding through the dissemination phases of the project; a flexible and adaptive intervention that emphasized integrating healthful eating and physical activity into organizational (church) routines; and a public health focus on changing the church physical and social environment to achieve population behavior change (Wilcox et al., 2010, 2013). Given the complexity of the setting and intervention approach, a comprehensive approach to process evaluation was an integral part of the FAN project. A potentially important, but underused, application of process data is to examine the effects of intervention implementation on primary study outcomes (Baranowski & Stables, 2000; Linnan & Steckler, 2000).

The FAN intervention, described previously (Wilcox et al., 2010), entailed working in partnership with church pastors, FAN committees, and cooks, who were provided training and on-going technical assistance to increase their capacity to assess the church environment and to develop and carry out a plan to promote physical activity and healthful diet based on the Health-Promoting Church framework. Thus, the FAN intervention can be characterized as a standardized process (Hawe, Shiell, & Riley, 2004; Hawe, Shiell, & Riley, 2009) that allowed variation in implementation details from church to church to accommodate specific, local contexts. This type of flexibility is an important consideration when addressing physical, organizational, and social change (Poland, Krupa, & McCall, 2009) and is also associated with sustained change (Scheirer, 2005). Accordingly the FAN intervention may be characterized as both complex (Chen, 2005; Cohen, Scribner, & Farley, 2000; Foster-Fishman, Nowell, & Yang, 2007; Hawe et al., 2004) and structural, targeting change in factors beyond the control of individuals in the setting (Blankenship, Friedman, Dworkin, & Mantell, 2006; Cohen et al., 2000; Matson-Koffman, Brownstein, Neiner, & Greaney, 2005). Consistent with the CBPR approach, church leaders and members were involved in the planning and implementation process for environmental change within the church organization. Facilitating setting-appropriate structural change through a participatory approach has potential for sustainable, population impact in faith-based settings.

2. Background

Complex structural interventions require extensive stakeholder involvement, longer time frames, and are subject to strong contextual influences (Chen, 2005; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Therefore, they pose evaluation design and execution challenges which necessitate a comprehensive approach to program evaluation and implementation monitoring (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Medical Research Council, 2008). Previous reports have described implementation monitoring for complex structural interventions in organizational settings including LEAP in schools (Saunders, Ward, Felton, Dowda, & Pate, 2006; Saunders et al., 2012) and ENRICH in children’s group homes (Saunders et al., 2013). This report applies this approach to a CBPR intervention to promote physical activity and healthy eating in churches, which have some unique features.

A recent review of process evaluation in faith-based settings revealed that few report a comprehensive approach to process evaluation (Yeary, Klos, & Linnan, 2012). An average of about three of seven possible process evaluation components were reported, most commonly recruitment (88%) and reach (81%), followed by context (34%), dose delivered (28%), and dose received (27%); less frequently reported were implementation (21%) and fidelity (9%) (Yeary et al., 2012). The FAN process evaluation was comprehensive and included dose-delivered or completeness, dose-received, reach, fidelity, context, and recruitment. Because FAN was a structural intervention with an emphasis on changing the environment with the presumption that congregants within that environment would be “exposed” to the intervention (versus an emphasis on exposing individuals to intervention components), the process evaluation components are defined differently in FAN. Reach was defined at the organizational level (i.e., church team and leader participation in training). Similarly, implementation fidelity was defined as the extent to which the church committees (serving as organizational change agents) made changes in the church environment (Wilcox et al., 2010), as reported by congregant and key informant perceptions of environmental change. The purposes of this paper are to present the FAN process evaluation methods and implementation fidelity results (Study 1), and to examine the relationship between implementation and study outcomes (Studies 2 and 3).

3. Study I: implementation monitoring

3.1. Implementation monitoring planning

The processes of planning the FAN intervention and process evaluation were based on guidelines for developing a program implementation monitoring plan (Saunders, Evans, & Joshi, 2005) and methods for assessing organizational level implementation (Saunders et al., 2006, 2012, 2013), derived from the frameworks presented by Linnan and Steckler (2000) and Baranowski and Stables (2000). The steps for designing and carrying out process evaluation applied to this study are: describing the setting, context, and program; describing “fidelity and dose” for the program; developing implementation monitoring methods to address process evaluation questions; examining the mean implementation for each intervention component; and using implementation data to understand outcomes (including the use of mediation analyses, which allows researchers to understand how an intervention exerts its effects on program outcomes).

3.1.1. Describe the setting, context, and implementation approach

FAN was a CBPR project, initiated and carried out by a multiorganizational partnership consisting of the University of South Carolina, the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, the Medical University of South Carolina, Clemson University and Allen University, as previously reported (Wilcox et al., 2010). During the first year of the project, a planning committee that included church leaders, lay church members, and university faculty and staff met monthly to plan the intervention and evaluation and met quarterly to oversee study activities in subsequent years. As described in detail elsewhere (Wilcox et al., 2010, 2013), 128 churches from four AME districts in South Carolina were invited to participate in this group randomized trial and 74 of these enrolled. Churches were located in both rural and more populated areas, and 26 were considered small in size (<100 members), 44 medium (100–500 members), and 12 large (>500 members). Churches were randomized to receive the intervention shortly after baseline measurements were taken (early churches, n = 38) or after a 15-month delay (delayed churches, n = 36). Delayed churches thus served as the control group for early churches. However, not all churches were included in this study because some churches did not have complete pre/post data on any participants. This study included 68 churches with participant data (37 intervention, 31 control).

3.1.2. Describe the program

The 15-month FAN program consisted of a full-day committee training, a full-day cook training, monthly mailings to churches with information and materials to help support implementation, and technical assistance calls. Each church formed a FAN committee and attended a training that focused on assessing current church activities to promote physical activity and healthy eating and then ways to add, enhance, or expand them. The FAN committee thus served as organizational change agents (Commers, Gottlieb, & Kok, 2007). Churches were asked to implement physical activity and healthy eating activities that targeted each of the four structural factors within the structural ecologic model (Cohen et al., 2000): availability and accessibility, physical structures, social structures, and cultural and media messages. Each church developed a formal plan and budget and received a stipend upon plan approval (up to $1000 depending on church size) to assist them with program implementation. A separate training was held for church cooks or those involved in meal planning at the church (Condrasky, Baruth, Wilcox, Carter & Jordan, 2013). This training focused on the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) (Sacks et al., 1999) diet plan. The training was participatory and helped churches to modify current recipes and offer options that were healthier.

Each church received a monthly mailing that included information about physical activity and healthy eating, health behavior change strategies, incentives, handouts supporting FAN goals (e.g., bulletin inserts), and tools for cooks (e.g., recipes). Pastors received motivational information and an activity to try. Finally, follow-up technical assistance calls were made to pastors, FAN coordinators, and cooks on a rotating basis. The calls focused on program implementation and problem-solving to overcome challenges.

3.1.3. Describe desired “fidelity and dose” for the program

Complete and acceptable delivery for FAN was based on the characteristics of the Health-Promoting Church. The framework for defining the optimal church environment was developed by the planning committee through a facilitated discussion, co-lead by an investigator from the church and from the university, and organized by the components of the structural ecologic model (Wilcox et al., 2010). The planning committee brainstormed quite a few possible activities for promoting physical activity and healthy eating with the expectation that some, but not all, would be applicable across the different churches. The details of the group brainstorming activity are presented in Table 1. This framework emphasized environmental change within the organizational setting of the church; the framework guided intervention activities and defined implementation fidelity for the FAN process evaluation.

Table 1.

Stakeholder group brainstorming activity – the ideal Health-Promoting Church.

| Introduction |

| In order to begin our planning process, we want to spend some time discussing what the ideal church that promotes physical activity and healthy nutrition looks like. At the end of this discussion (which may take more than one meeting), we will agree on the ideal “final product” of a healthy church. This ideal “final product” will be the target that participating churches can shoot for; however, there will be a lot of flexibility as to how each church will go about building a health-promoting environment. |

| To get you thinking about this ideal church, it might help to imagine people from Mars coming to this idea church. How would they know it was a church that promotes physical activity and healthy nutrition? What would they see? What would they hear? How would this ideal healthy church be different from other churches? |

| Keep in mind our project goals when you think about “physical activity” and “healthy eating”: |

| Physical activity = 30+ min per day, 5 or more days per week, of moderate-intensity physical activity (intensity similar to brisk walking) |

| Healthy eating = eating a diet high in fruits and vegetables and grains and low in saturated and trans fats and sodium |

| Probes (use examples if the group does not seem to understand or is not providing related suggestions): |

Opportunities and environment

|

Policies and practices

|

Encouragement and social support

|

Media

|

The product resulting from the brainstorming activity was the previously reported (Wilcox et al., 2010) elements of the Health-Promoting Church organized by the structural ecologic model (Cohen et al., 2000). An assessment and planning tool based on these elements was created for church committees which enabled the planning committee to set priorities and remain consistent with a flexible, adaptable approach. This tool guided church committees to select activities and organizational practices in physical activity and healthy eating that provided opportunities in which congregants could engage; described ways in which these activities could be relevant to the faith setting as well as enjoyable for church members; provided information and materials for everyone; and helped the pastor support the program. This resulted in 9 “core activities” in physical activity and 12 in healthy eating, which define FAN implementation fidelity and are the focus of this report.

3.2. Methods for implementation monitoring

The iterative planning process of defining implementation monitoring methods involved determining process evaluation data sources, instruments, and data collection procedures based on the process evaluation questions. The planning process culminated in developing the final process evaluation plan. The comprehensive process evaluation in FAN was guided by questions that addressed dose delivered or completeness, dose received, reach for training participants, fidelity for implementation and organizational change, context, and recruitment processes, and, as recommended (Cooksy, Gill, & Kelly, 2001), the evaluation plan was organized by the FAN logic model (see Table 2). Fidelity for implementation and organizational change were addressed by the previously reported process evaluation questions (Wilcox et al., 2010): “To what extent was the church organization and environment consistent with ‘Health-Promoting Church’ policies and practices?” and “To what extent did the FAN committee members, cooks, and pastors carry out planned activities based on ‘Health-Promoting Church’ guidelines?”.

Table 2.

FAN process evaluation logic model and overview of variables used in mediation analysis.

| Inputs | Activities | Implementation/organizational outcomes |

Behavioral determinants |

Behavior change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain of events logic model | With the guidance of the planning committee, FAN will provide training, TA and follow up consultation to FAN committees and pastors which will | Facilitate the development of knowledge, confidence, and skills among FAN Committee members and church cooks to create a healthier church environment which, with the pastors and elders active support, will | Result in the FAN committees using healthy church criteria (i.e., core elements for PA and healthy eating) to plan and put in place relevant and enjoyable opportunities for PA and healthy eating, provide health-promoting messages, and enlist pastor support for PA and healthy eating in their churches, which will | Result in changes in learning, attitudes and skills among AME members which will | Result in AME members meeting recommendations for PA and following guidelines for DASH diet |

| Measures |

Process: Dose delivered Documentation of activities; staff records [not reported here] |

Process: Dose received

|

Process: Fidelity

|

Individual Behavior Mediators

|

Individual Behavior Outcomes Self-report Physical activity and Fruit and Vegetable intake measures |

Adapted from Wilcox et al. (2010).

Note: Highlighted measures used in mediation analyses. Shaded portion depicts project elements evaluated with process evaluation.

The process evaluation methods to address the two implementation fidelity questions are summarized for physical activity and healthy eating in Table 3. The 9 core activities in physical activity and 12 in healthy eating that defined FAN implementation fidelity are depicted in Table 3 as “core activities”. FAN tapped multiple data sources and organizational levels (e.g., pastors, FAN coordinator, congregants), as recommended (Bouffard, Taxman, & Silverman, 2003; Dusenbury, Brannigan, Falco, & Hansen, 2003). Specific tools used to collect implementation fidelity data were the survey administered to congregants at baseline and post-intervention (3 intervention domains, described below) and the organizational assessments administered to the health director or FAN coordinator, pastor, and cook at posttest (one intervention domain, described below).

Table 3.

Congregant and organizational assessment survey items, variable definitions and criteria used to assess FAN implementation fidelity.

| Component | Core activities | No. of items | Sample Item Coding | Variable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition domain | Getting the message out | 1 – Bulletin inserts 2 – Health moments 3 – Handouts |

3 | How often has your church included written information about healthy eating in Sunday Bulletin? Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Often = 3, Most/All of the time = 4 |

Mean score for survey items |

| Providing opportunities | 4 – Healthy food options at church (fruits & vegetables) | 1 | How often are fruits and vegetables served at church events that involve food? Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Often = 3, Most/All of the time = 4 |

Value for survey item | |

| Pastor support | 5 – Pastor talks about healthy eating from the pulpit | 1 | How often has your pastor spoken about healthy eating from the pulpit? Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Often = 3, Most/All of the time = 4 |

Mean score for survey item | |

| Organizational policies, practices and guidelines | 6–12 Five elements: fruit and vegetables, grains, low fat, low sodium, drinks | 6 | Is there a guideline in place in your church that says that fruits will be included in all events where food is served? No = 0, yes = 1 |

Mean score for Health Director, Pastor or Cook items, as available | |

| Physical activity domain | Getting the message out | 1 – Bulletin inserts 2 – Health moments 3 – Handouts |

3 | How often has the health director or someone other than the pastor spoken about PA during worship services? Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Often = 3, Most/All of the time = 4 |

Mean score for survey items |

| Providing opportunities | 4 – Physical activity before, during, after service 5 – Physical activity in meetings, events 6 – Physical activity programs |

3 | How often has physical activity been included before, during or right after worship service? Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Often = 3, Most/All of the time = 4 |

Mean score for survey items | |

| Pastor Support | 7 – Pastors talk about physical activity from pulpit 8 – Pastor wears pedometer as a role model |

2 | How often have you seen your pastor wear a step counter (pedometer)? Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Often = 3, Most/All of the time = 4 |

Mean score for survey items | |

| Organizational policies, practices & guidelines | 9 – One element: PA break | 1 | Is there a guideline in place in your church that says that a 10-minute physical activity break should be

included in church meetings that last 60 minutes or longer? No = 0, yes = 1 |

Mean score for Health Director or Pastor items, as available |

3.2.1. Implementation monitoring measures and statistical analysis

3.2.1.1. Congregant survey: implementation variables for healthy eating and physical activity

Healthy eating and physical activity implementation variable definitions, based on the congregant survey items, are presented in Table 3. For healthy eating “Getting the message out” was assessed by three items; “providing opportunities” by one item; and “pastor support” by one item. For physical activity “Getting the message out” was assessed by three items; “providing opportunities” by three items; and “pastor support” by two items. All items were rated on four-point scales and church-level means were calculated to reflect level of implementation (higher score = greater implementation). Detailed design and methods for administering congregant surveys have previously been reported (Wilcox et al., 2013). In summary, participants were recruited by church liaisons to take part in a measurement session. To be eligible, participants had to report being at least 18 years of age, being free of serious medical conditions or disabilities that would make changes in PA or diet difficult, and attending church at least once a month. Upon providing consent, trained staff took physical assessments and participants completed a comprehensive survey.

3.2.1.2. Organizational assessment: implementation variables for organizational policies, practices and guidelines for healthy eating and physical activity

Health directors, pastors, and cooks were interviewed at posttest to assess implementation of healthy eating “organizational policies, practices and guidelines” in their churches. For each respondent six items (pertaining to fruits, vegetables, grains, low fat, low sodium, and drinks) were coded yes (1) or no (0); the mean score (ranging from 0 to 1) was used as an indicator of organizational guidelines and supports (Table 3). For physical activity, health directors and pastors were interviewed during the program to assess guidelines and supports for physical activity in their church. For each respondent a single item (pertaining to physical activity breaks at church) were coded yes (1) or no (0); the mean score (ranging from 0 to 1) was used as an indicator of organizational guidelines and supports (Table 3). An average score across all respondents completing the organizational assessment was calculated to get a mean score for each church (higher score = greater implementation).

3.3. Results for implementation monitoring

Church-level implementation, based on congregant surveys, for “getting the message out”, “opportunities”, and “pastor support” for both physical activity and healthy eating at pre-test and posttest are shown in Table 4, as are the psychosocial variables, social support and self efficacy. Church-level implementation, based on the organizational assessment, for “policy, practices and guidelines” for physical activity and healthy eating at post-test are also presented in Table 4. As shown, churches typically had higher implementation scores for healthy eating than for physical activity at pre-test and post-test. Also, implementation scores generally increased in intervention but not control churches for both healthy eating and physical activity elements (tested in Study 2).

Table 4.

Mean physical activity and healthy eating implementation scores and means (and standard deviations) for Psychosocial variables from congregants.

| Intervention | Control | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response range | Churches | N | Pre | Post | Churches | N | Pre | Post | |

| Physical activity | |||||||||

| Getting the message out | 1–4 | 37 | 375 | 2.02 (0.53) | 2.34 (0.52) | 31 | 257 | 2.23 (0.51) | 2.26 (0.48) |

| Opportunities | 1–4 | 37 | 375 | 1.44 (0.25) | 1.89 (0.58) | 31 | 257 | 1.44 (0.21) | 1.42 (0.23) |

| Pastor support | 1–4 | 37 | 375 | 1.67 (0.34) | 1.97 (0.47) | 31 | 257 | 1.84 (0.35) | 1.77 (0.30) |

| PA policy | 0–1 | 17 | 191 | NA | 0.31 (0.45) | 12 | 123 | NA | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Social support | 1–4 | 37 | 375 | 2.53 (0.30) | 2.70 (0.31) | 31 | 257 | 2.61 (0.21) | 2.66 (0.32) |

| Self efficacy | 1–4 | 37 | 375 | 2.70 (0.24) | 2.64 (0.28) | 31 | 257 | 2.76 (0.24) | 2.70 (0.24) |

| Healthy eating | |||||||||

| Getting the message out | 1–4 | 37 | 371 | 1.96 (0.51) | 2.28 (0.54) | 31 | 256 | 2.11 (0.49) | 2.15 (0.42) |

| Opportunities | 1–4 | 37 | 371 | 2.87 (0.39) | 3.09 (0.43) | 31 | 256 | 2.94 (0.32) | 3.04 (0.32) |

| Pastor support | 1–4 | 37 | 371 | 2.19 (0.55) | 2.55 (0.60) | 31 | 256 | 2.30 (0.38) | 2.36 (0.39) |

| PA policy | 0–1 | 17 | 188 | NA | 0.80 (0.27) | 14 | 128 | NA | 0.30 (0.30) |

| Social support | 1–4 | 37 | 371 | 2.46 (0.36) | 2.64 (0.37) | 31 | 256 | 2.55 (0.23) | 2.64 (0.32) |

| Self efficacy | 1–4 | 37 | 371 | 3.12 (0.16) | 3.14 (0.24) | 31 | 256 | 3.10 (0.20) | 3.16 (0.21) |

Note: These means are the mean scores of church means. Lower score means less implementation, lower social support, and lower self efficacy.

4. Study II: using implementation data in mediation analysis

Process evaluation data may be used for summative purposes to describe the level of implementation and as a categorical or continuous variable in outcome analyses to better understand study outcomes. In this study we had continuous implementation variables and wanted to examine the relationship between implementation of intervention components and study outcomes. In Study 2 we conducted mediation analyses with implementation variables and primary study outcomes (physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake) in an effort to understand how or why the intervention exerted its effects. Mediation analyses examine whether an intervention X affects mediator M which in turn leads to outcome Y. Non-significant mediation in a straightforward model such as this does not necessarily imply that the mediator is not important (Maric, Wiers, & Prins, 2012). It is possible that the relationships are more complex, for example, whereby two or more mediators intervene between an intervention X and outcome Y (i.e. sequential mediation) (Maric et al., 2012). Therefore, in Study 3 we conducted sequential mediation analyses with implementation, psychosocial variables, and outcome variables. Specifically, we examined the relationships among group assignment to condition, level of implementation of the FAN elements of a Health-Promoting Church (operationalized by the implementation variables), psychosocial variables (self efficacy and social support summarized at church level), and outcome variables

4.1. Methods for mediation analysis

4.1.1. FAN outcome measures

The primary study outcomes, measured at baseline and 15- months later (post-intervention for intervention churches) were congregant self-reported physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption described in more detail below (see Wilcox et al., 2010, 2013).

4.1.1.1. Community Health Activities Model Program for Seniors (CHAMPS)

The 36-item modified version of CHAMPS questionnaire (Stewart, Mills, et al., 2001) was used to measure moderate-to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) “in a typical week during the past 4 weeks.” As previously reported, the measure has strong psychometric properties, including validity (Harada, Chiu, King, & Stewart, 2001) test-retest reliability (Harada et al., 2001) and sensitivity to change (King et al., 2000; Stewart et al., 1997; Stewart, Mills, et al., 2001; Stewart, Verboncoeur, et al., 2001; Stewart, 2001; Wilcox et al., 2008). We calculated hours per week of leisure-time MVPA (i.e., removed household and related activities). Square root transformations corrected skewness in baseline and post-program scores. Leisure-time MVPA at the individual level was used in all analyses.

4.1.1.2. National Cancer Institute (NCI) fruit and vegetable (FV) all-day screener

The NCI FV all-day screener (NCI, 2000) was used to measure cups per day of fruits and vegetables over the past month using 9 of the original 10 items. French fries were excluded due to their high fat content because they are not included as a vegetable in current dietary recommendations (ChooseMyPlate.gov). As previously reported this instrument correlates with 24-h recall measures (men: r = 0.66; women: r = 0.51) (Thompson et al., 2002). Square root transformations corrected skewness in baseline and post-program scores. FV consumption at the individual level was used in all analyses.

4.1.2. Statistical analysis

Church-level means for each implementation (i.e., mediator) variable, reflecting the level of implementation for FAN intervention components, were calculated and used in all mediation analyses. MacKinnon’s product of coefficients test (ab) was used to test for mediation (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002).

Two ANCOVA models, using SAS PROC MIXED, were conducted for each mediator. The first model regressed the implementation (i.e., mediator) variable at posttest on intervention group assignment, controlling for the implementation (i.e., mediator) variable at baseline (a coefficient). The second model regressed the outcome variable on group assignment and the implementation (i.e., mediator) variable, controlling for the outcome and the implementation (i.e., mediator) variables at baseline (b coefficient). The following implementation variables, as operationalized in Table 3, were tested as mediators: getting the message out, opportunities, pastor support, and organizational policy. Separate mediation models were conducted for each mediating variable, and for the physical activity and fruit and vegetable outcomes separately. Organizational policy implementation was assessed at posttest; therefore, baseline values of this variable were not controlled for in analyses including this mediator. All models controlled for gender, age, education (some college or higher verses high school graduate or less), wave, and church size and accounted for church-level clustering. To assess the magnitude of the effect, asymmetric confidence limits based on the distribution of the product were constructed (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011).

4.2. Results for mediation analysis

The mixed model analyses showed no support for the idea that implementation of messages, opportunities, pastor support, and policy were mediators of program outcomes (Table 5). However, the a paths for all variables (except opportunities, which was substantially higher at baseline than the other variables) were significant, indicating that the intervention increased the implementation variable scores corresponding to the intervention components targeted in the intervention. However, none of the b paths were significant, indicating that changes in the implementation mediators were not associated with changes in physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption.

Table 5.

Mediation analysis examining effects of implementation variables on study outcomes of physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake.

| Group assignment → change in implementation variable a path |

Change in implementation variable →change in outcome variable b path |

Asymmetric confidence limits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | p-Value | Estimate (SE) | p-Value | ||

| Physical activity (n = 632) | |||||

| Physical activity messages | .1032 (.04856) | .0374 | −.04158 (.1042) | .690 | −.031, .019 |

| Physical activity opportunities | .305 (.03572) | <.0001 | −.1368 (.1122) | .2232 | −.112, .025 |

| Physical activity pastor support | .1747 (.03221) | <.0001 | −.05434 (.1326) | .6821 | −.057, .037 |

| Physical activity policy (n = 314) | .2836 (.04291) | <.0001 | −.02440 (.2208) | .9121 | −.133, .118 |

| Healthy eating (n = 627) | |||||

| Healthy eating messages | .1261 (.04658) | .0086 | .05158 (.06275) | .4114 | −.009, .026 |

| Healthy eating opportunities | .04332 (.04751) | .3652 | −.01843 (.07647) | .8097 | −.012, .009 |

| Healthy eating pastor support | .1342 (.04278) | .0025 | .01591 (.06441) | .8050 | −.016, .021 |

| Fruit and vegetable policy (n = 316) | .5348 (.04245) | <.0001 | −.1196 (.1367) | .3825 | −.210, .079 |

Note: If the asymmetric confidence limits include 0, there is no evidence of mediation.

As shown in the FAN logic model (Table 1), it is possible that the mechanisms of change were more complex (McNeil, Wyrwich, Brownson, Clark, & Kreuter, 2006). FAN focused on change at the organizational level factors to create Health-Promoting Church environments. In turn, the Health-Promoting Church environment was expected to positively influence psychosocial variables and ultimately health behavior and health outcomes for congregants (Blankenship et al., 2006; Cohen et al., 2000; Matson-Koffman et al., 2005). However, little is known about the mechanisms through which environmental changes mediate change in individual behavior, particularly in organizational settings. The next step was to explore sequential mediation using both the process variables and the psychosocial variables as suggested by the logic model.

5. Study III: using implementation data in sequential mediation analysis

An approach that allows a more fine-grained understanding of mediation processes is sequential mediation analysis (Cury, Elliot, Sarrazin, Da Fonseca, & Rufo, 2002). This approach is applicable when two or more mediators intervene in a series between the independent and dependent variables (Maric et al., 2012).

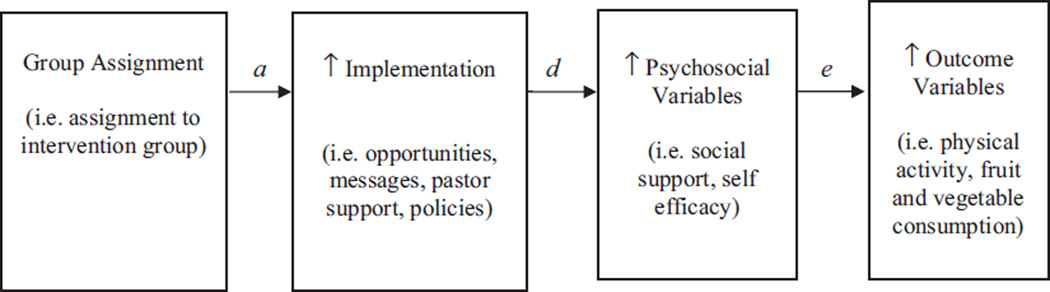

For the sequential mediation analysis, we examined the sequential relationships between assignment to condition (intervention versus control), implementation variables (same as the implementation variables in the previous analysis), psychosocial variables known to be associated with physical activity and dietary behavior (i.e., social support and self efficacy), and FAN behavior outcomes (i.e., physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake). As shown in Fig. 1, we expected assignment to the intervention condition to be associated with greater implementation, and that higher levels of implementation would be related to positive impacts on the psychosocial mediator variables, which would in turn be related to positive changes in individual behavior outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Sequential mediation paths.

5.1. Methods for sequential mediation analysis

5.1.1. Psychosocial measures

Congregant surveys at baseline and post-intervention measured self efficacy and social support. Church-level means for both variables were calculated and used in all analyses. Group level means for the psychosocial variables, self efficacy and social support, are reported in Table 4.

5.1.1.1. Self efficacy for physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption

An adapted 12-item version of Sallis’ scale (Sallis, Pinski, Grossman, Patterson, & Nader, 1988) measured self efficacy for physical activity and a 10-item scale used in two other faithbased projects (Resnicow et al., 2002, 2004, 2005) measured self efficacy for fruit and vegetable consumption. Using a 4-point response scale, participants were asked how confident, in the next 6 months, they were that they could exercise when faced with common barriers and eat fruits and vegetables when faced with common barriers.

5.1.1.2. Social support for physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption

Social support for physical activity (3-items) and fruit and vegetable consumption (3-items) over the past 12 months from family, friends or work colleagues, and people at church were measured on a 4-point response scale. The items used to assess family and friend/colleague support were derived from a study by Eyler et al. (1999) which were adapted from the Sallis and colleagues (Sallis, Grossman, Pinski, Patterson, & Nader, 1987) scale. The items assessing support from church members were similar to those used in another faith-based project (Resnicow et al., 2005).

5.1.2. Statistical analysis

The same statistical approach (i.e. PROC MIXED) and covariates used in the mediation analyses described above were used in the sequential mediation analyses. As depicted in Fig. 1, the test of joint significance tested for sequential mediation (i.e. group assignment → change in implementation variables → change in psychosocial variables → change in outcome) (MacKinnon et al., 2002).

Three ANCOVA models were conducted for each mediation sequence. The first model regressed the implementation variable at post on intervention group assignment (a coefficient). The second model regressed the psychosocial variable at post on the implementation variable at post, controlling for group assignment (d coefficient). The third model regressed the outcome variable at post on the psychosocial variable at post, controlling for the implementation variable at post, and group assignment (e coefficient). Baseline values of the implementation, psychosocial and/or outcome variable(s) were also included in each of the three models. Because organizational policies were only measured at post, baseline values of this variable were not controlled for in analyses including this variable. In line with the test of joint significance, if all three models (i.e. a, d, and e paths) were significant, there was significant mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2002). Separate sequential mediation models were conducted for each combination of implementation and psychosocial variables, for both outcome variables (see Table 5).

5.2. Results for sequential mediation analysis

For all physical activity intervention components, assignment to the intervention condition was significantly associated with higher levels of implementation, indicating that the intervention increased the implementation variable scores corresponding to the intervention components targeted in the intervention (a path). When examining the d path, results showed that increases in the number of physical activity messages were associated with increases in self efficacy and social support, whereas increases in opportunities for physical activity and pastor support for physical activity were associated with increases in social support only. Unexpectedly, increases in opportunities for physical activity were negatively associated with changes in self efficacy; and a higher number of physical activity policies, practices and guidelines at posttest were negatively associated with changes in self efficacy and social support. When examining the e path, associations between increases in social support and self efficacy and increases in physical activity were all in the expected direction and were significant for messages and self efficacy, pastor support and self efficacy, and policy and social support models and approached significance for the other models (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Sequential mediation analyses examining association between group assignment, change in implementation variables, change in psychosocial variables, and change in outcomes.

| Group assignment → change in implementation variable a path |

Change in implementation variable → change in psychosocial variable d path |

Change in psychosocial variable → change in outcome e path |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | p-Value | Estimate (SE) | p-Value | Estimate (SE) | p-Value | |

| Physical activity (n = 632) | ||||||

| Messages and self efficacy | .10 (.05) | .04 | .06 (.02) | .01 | .45 (.22) | .04 |

| Messages and social support | .10 (.05) | .04 | .28 (.03) | <.0001 | .33 (.18) | .07 |

| Opportunities and self efficacy | .30 (.04) | <.0001 | −.08 (.03) | .01 | .39 (.21) | .07 |

| Opportunities and social support | .30 (.04) | <.0001 | .33 (.04) | <.0001 | .32 (.17) | .06 |

| Pastor support and self efficacy | .17 (.03) | <.0001 | .03 (.03) | .38 | .47 (.22) | .03 |

| Pastor support and social support | .17 (.03) | <.0001 | .33 (.04) | <.0001 | .32 (.17) | .06 |

| Policy and self efficacy (n = 314) | .28 (.04) | <.0001 | −.21 (.05) | <.0001 | .75 (.39) | .06 |

| Policy and social support (n = 314) | .28 (.04) | <.0001 | −.13 (.05) | .01 | .62 (.28) | .03 |

| Healthy eating (n = 627) | ||||||

| Messages and self efficacy | .13 (.05) | .01 | .18 (.02) | <.0001 | .03 (.15) | .85 |

| Messages and social support | .13 (.05) | .01 | .32 (.03) | <.0001 | .11 (.11) | .33 |

| Opportunities and self efficacy | .04 (.05) | .37 | .26 (.02) | <.0001 | .07 (.15) | .62 |

| Opportunities and social support | .04 (.05) | .37 | .22 (.03) | <.0001 | .13 (.09) | .16 |

| Pastor support and self efficacy | .13 (.04) | .003 | .14 (.03) | <.0001 | .04 (.14) | .77 |

| Pastor support and social support | .13 (.04) | .003 | .33 (.03) | <.0001 | .12 (.10) | .21 |

| Policy and self efficacy (n = 316) | .53 (.04) | <.0001 | .03 (.05) | .59 | .38 (.28) | .17 |

| Policy and social support (n = 316) | .53 (.04) | <.0001 | −.03 (.06) | .60 | .15 (.15) | .33 |

Note: If all three models (i.e. a, d, and e paths) were significant, there was significant mediation; p < .05 considered significant.

For the healthy eating intervention components, assignment to intervention condition was significantly related to higher implementation scores for messages, opportunities and pastor support but not for opportunities for healthy eating (a path). Increases in all of the implementation variables, with the exception of policy, were associated with increases in both psychosocial variables (i.e., social support and self-efficacy; d path). However, changes in the psychosocial variables were not associated with changes in fruit and vegetable intake in any of the models (e path).

As shown in Table 6 there was evidence of significant sequential mediation in one model. Assignment to the intervention condition was associated with increases in getting the message out about physical activity, which was associated with increases in self efficacy for physical activity, which was associated with increases in physical activity. A similar pattern was evident for messages, social support, and physical activity; opportunities, social support, and physical activity; and pastor support, social support, and physical activity, although the paths did not reach statistical significance.

6. Discussion

This paper reported the process evaluation methods, implementation fidelity, and relationship between implementation and study outcomes in a large faith-based intervention and may be a useful model to others who are developing a comprehensive process evaluation framework and approach in faith-based settings. Due to the structural nature of the FAN intervention, level of implementation of the Health-Promoting Church components reflects changes in the church environment. In turn, changes in the church environment were expected to influence congregant behavior. Our findings underscore the complexity of organizational change interventions. We found that although the intervention led to increased implementation and therefore environmental change, increased implementation did not directly result in increased physical activity. A sequential mediation analysis helped us to understand that implementation was associated with congregant self-efficacy and social support, which thereby was associated with physical activity. As depicted in the FAN logic model, these relationships along the “causal chain” between implementation and outcomes are sequential and complex. These results illustrate the complexity of systems change within organizational settings (Foster-Fishman et al., 2007).

We observed some associations in unexpected directions for physical activity; specifically, increases in opportunities for physical activity were negatively associated with changes in self efficacy. It is difficult to interpret these results; it is interesting to note that the self efficacy scale addresses confidence to overcome common barriers, which may also be addressed by increasing convenient physical activity opportunities at church. Also unexpectedly a higher number of physical activity policies, practices and guidelines at posttest were negatively associated with changes in self efficacy and social support. It is possible that different data sources (i.e., organizational key informants versus congregants) and different methodologies (post test only versus change scores) were a factor in these findings; additional study may clarify the influence of methods versus policies, practices, and guidelines. It is also possible that increased emphasis on and participation in PA resulted in increased awareness of barriers to PA, which could result in decreased self efficacy based on realistic experience.

For healthy eating, assignment to condition was associated with higher implementation scores for messages, opportunities and pastor support, but not for opportunities for healthy eating, and these increases were associated with increases in both psychosocial variables (i.e., social support and self-efficacy). However, changes in social support and self efficacy were not associated with changes in fruit and vegetable intake. Therefore for healthy eating we found no evidence for sequential mediation nor was implementation of the FAN healthy eating intervention components, “getting the message out”, “opportunities”, “pastor support”, and “policy, practices and guidelines” associated with healthy eating behavior of congregants. Churches did report higher implementation of healthy eating at baseline, which may have been a limiting factor. The church setting is very conducive to making healthy changes for eating, as most have kitchens and food is commonly served at church events. Because there were more opportunities for providing food and for implementing dietary changes, it may have been easier to implement dietary compared to physical activity changes within the church. There is less preexisting infrastructure for physical activity in this setting; therefore, without support, it is unlikely churches would integrate PA into their normal routine.

The approach depicted in this paper provides another example of using implementation fidelity constructs within statistical models to examine the effects of implementation fidelity on study outcomes (Zvoch, 2012). The physical activity results are similar to those found in a community setting, in which both social and physical environmental effects on physical activity of adults were mediated through self efficacy and social support (McNeil et al., 2006).

Limitations of the study include the use of self-reported data for study outcomes, as well as implementation and psychosocial variables. The outcome and psychosocial measures have established reliability and validity; however, the process measures do not as they were developed specifically based on the FAN framework for a Health-Promoting Church. There was a suboptimal response from key informants (pastors, FAN committee contact, cooks), resulting in missing data for some churches on the implementation variable “policies, practices and guidelines”. This is consistent with previously reported challenges regarding survey response from key informants and implementers in faith-based settings (Campbell et al., 2000). As reflected on the logic model (bottom row, Table 2), we attempted to implement a more comprehensive and “triangulated” approach but poor response, particularly from FAN coordinators, made this challenging. Finally, assessment of “policies, practices and guidelines” implemented was based on post-test assessments only.

The study has several strengths, including a group randomized evaluation design that was longitudinal in nature. We collected pre-and post-test assessments of congregant perceptions of implementation variables reflecting the church social environment pertaining to physical activity and healthy eating, “getting the message out”, “opportunities”, and “pastor support”. This enabled us to examine change in these perceptions over time. As previously mentioned, the psychosocial and outcome measures were well-established tools for use in this population. As appropriate in CBPR, there was extensive stakeholder involvement in planning and carrying out the project, including developing the “Health-Promoting Church” framework. Finally, we used a proactive and comprehensive approach to process evaluation planning that enabled us to collect relevant data throughout project implementation and then to use the implementation data in understanding program outcomes within the church organizational setting.

7. Lessons learned

The results of this study illustrate the importance of examining relationships among implementation, psychosocial and outcome variables in complex interventions in field-based settings. We documented that assignment to the intervention (compared to control) condition was associated with higher levels of implementation of elements of the Health-Promoting Church for both physical activity and healthy eating. However, better implementation was not directly related to better behavioral outcomes for physical activity or fruit and vegetable consumption. Rather, higher implementation of selected intervention components was associated with positive impacts on selected psychosocial variables (i.e., social support and self efficacy), and changes in psychosocial variables were related to physical activity but not fruit and vegetable consumption. A better understanding of the mechanisms through which implementation of specific intervention components create change in outcome variables will enable us to develop approaches with the potential to maximize the public health impact of structural interventions.

FAN benefited from participatory development of the Health-Promoting Church environment framework that was subsequently used to guide both the process evaluation and intervention. The process of defining the Health-Promoting Church environments that was applicable across multiple churches, though time consuming, resulted in a shared understanding of the project among the diverse members of the planning committee. It also facilitated clear communication with church stakeholders about the focus of the project, which enabled all partners to agree on and to work toward the same goal. Finally, the ability to examine sequential mediation in this study was facilitated by a logic model (Scheirer, Shediac, & Cassady, 1995; Linnan and Steckler, 2000) that depicted the expected mechanisms through which FAN was expected to achieve its outcomes.

7.1. Conclusions

The results presented here underscore the importance of clearly defining what constitutes implementation by operationalizing the program elements necessary to produce change (Bartholomew, Parcel, Kok, & Gottlieb, 2006; Harachi, Abbott, Catalano, Haggerty, & Fleming, 1999; Lillehoj, Griffin, & Spoth, 2004; Scheirer et al., 1995). This may be particularly important when the intervention components are defined at the organizational level (i.e., the Health-Promoting Church) and are implemented by existing church personnel who receive staff development and on-going consultation, as recommended for environmental change (Commers et al., 2007). Due to the complexity of the FAN intervention and settings, it was essential that we monitor implementation and examine the chain of events or causal pathway from implementation to outcomes guided by the FAN logic model.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant R01HL083858 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the NIH.

The authors thank the leaders of the 7th Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal church, especially the Bishop, participating Presiding Elders, and participating pastors for their support of FAN. The authors also thank the following individuals for their valuable contributions to the process evaluation: Deborah Kinnard, Kara Goodrich, and Tatiana Warren.

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00379925).

Biographies

Ruth P. Saunders is an Associate Professor in the Arnold School of Public Health at the University of South Carolina. She has conducted process evaluation in seven large-scale intervention trials and oversaw process evaluation in the FAN trial.

Sara Wilcox is a Professor in the Arnold School of Public Health and Prevention Research Center at the University of South Carolina and has served a principal investigator on numerous studies. She was the Principal Investigator on the FAN project.

Meghan Baruth received her PhD from the Arnold School of Public Health at the University of South Carolina and conducted the mediation analysis for this study.

Marsha Dowda is a Biostatistician in the Arnold School of Public Health at the University of South Carolina and conducted statistical analysis for the FAN project.

Contributor Information

Ruth P. Saunders, Email: rsaunders@sc.edu.

Sara Wilcox, Email: Wilcoxs@mailbox.sc.edu.

Meghan Baruth, Email: Stritesk@mailbox.sc.edu.

Marsha Dowda, Email: Mdowda@mailbox.sc.edu.

References

- Baranowski T, Stables G. Process evaluations of the 5-a-day projects. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27:157–166. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Intervention mapping. Designing theory- and evidence-based health promotion programs. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: Concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouffard JA, Taxman FS, Silverman R. Improving process evaluations of correctional programs by using a comprehensive evaluation methodology. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2003;6:149–161. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Motsinger BM, Ingram A, Jewell D, Makarushk C, Beatty B, et al. The North Carolina Black Churches United for Better Health Project: Intervention and process evaluation. Health Education and Behavior. 2000;27(2):241–253. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H-T. Practical program evaluation. Assessing and improving planning, implementation, and effectiveness. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, Scribner RA, Farley TA. A structural model of health behavior: A pragmatic approach to explain and influence health behaviors at the population level. Preventive Medicine. 2000;30:146–154. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commers M, Gottlieb N, Kok G. How to change environmental conditions for health. Health Promotion International. 2007;22:80–87. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dal038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condrasky MD, Baruth M, Wilcox S, Carter C, Jordan JF. Cooks training for faith, activity, and nutrition project with AME churches in SC. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2013;37:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooksy LJ, Gill P, Kelly A. The program logic model as an integrative framework for a multimethod evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2001;24:19–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cury F, Elliot A, Sarrazin D, Da Fonseca D, Rufo M. The trichotomous achievement goal model and intrinsic motivation: A sequential mediational analysis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2002;38:473–548. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research. 2003;18:237–256. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler AA, Brownson RC, Donatelle RJ, King AC, Brown D, Sallis JF. Physical activity social support and middle- and older-aged minority women: Results from a US survey. Social Science Medicine. 1999;49:781–789. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Fishman PG, Nowell B, Yang H. Putting the system back into systems change: A framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Amercian Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39:197–215. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harachi TW, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Fleming CB. Opening the black box: Using process evaluation measures to assess implementation and theory building. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(5):711–731. doi: 10.1023/A:1022194005511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada ND, Chiu V, King AC, Stewart AL. An evaluation of three self-report physical activity instruments for older adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2001;33:962–970. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: How “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? British Medical Journal. 2004;328:1561–1563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorizing interventions as events in systems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Pruitt LA, Phillips W, Oka R, Rodenburg A, Haskell WL. Comparative effects of two physical activity programs on measured and perceived physical functioning and other health-related quality of life outcomes in older adults. Journals of Gerontology A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2000;55:M74–M83. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.m74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj CJ, Griffin KW, Spoth R. Program provider and observer ratings of school-based preventive intervention implementation: Agreement and relation to youth outcomes. Health Education and Behavior. 2004;31(2):242–257. doi: 10.1177/1090198103260514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan L, Steckler A. Process evaluation and public health interventions: An overview. In: Steckler A, Linnan L, editors. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maric M, Wiers RW, Prins PJM. Ten ways to improve the use of statistical mediation analysis in the practice of child and adolescent treatment research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;1:177–191. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson-Koffman DM, Brownstein JN, Neiner JA, Greaney ML. A site-specific literature review of policy and environmental interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition for cardiovascular health: What works? American Journal of Health Promotion. 2005;19:167–193. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil LH, Wyrwich KW, Brownson RC, Clark EM, Kreuter MW. Individual, social environmental, and physical environmental influences on physical activity among Black and white adults: A structural equation analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;31(1):35–44. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Research Council. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: New guidance. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.mrc.ac.uk/Utilities/Documentrecord/index.htm?d=MRC004871. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Fruit & vegetable screeners: Validity results. 2000 Retrieved from http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/screeners/fruitveg/validity.html.

- Poland B, Krupa G, McCall D. Settings for health promotion: An analytic framework to guide intervention design and implementation. Health Promotion Practice. 2009;10:505–516. doi: 10.1177/1524839909341025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Jackson A, Braithwaite R, DiIorio C, Blisset D, Rahotep S, et al. Healthy body/healthy spirit: A church-based nutrition and physical activity intervention. Health Education Research. 2002;17:562–573. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, Periasamy S, et al. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Jackson A, Blissett D, Wang T, McCarty F, Rahotep S, et al. Results of the healthy body healthy spirit trial. Health Psychology. 2005;24:39–348. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks FM, Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, et al. A dietary approach to prevent hypertension: A review of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Study. Clinical Cardiology. 1999;22(III):6–10. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Preventive Medicine. 1987;16:825–836. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Pinski RB, Grossman RM, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of self-efficacy scales for health-related diet and exercise behaviors. Health Education Research. 1988;3:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: A “how-to” guide. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6:134–147. doi: 10.1177/1524839904273387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders RP, Ward DS, Felton GM, Dowda M, Pate RR. Examining the link between program implementation and behavior outcomes in the Lifestyle Education for Activity Program (LEAP) Evaluation and Program Planning. 2006;29:352–364. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders RP, Pate RR, Dowda M, Ward DS, Epping JN, Dishman RK. Assessing sustainability of Lifestyle Education for Activity Program (LEAP) Health Education Research. 2012;27(2):319–330. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/cyr111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders RP, Evans AE, Kenison K, Workman L, Dowda M, Chu YH. Conceptualizing, implementing, and monitoring a structural health promotion intervention in an organizational setting. Health Promotion Practice. 2013;4(3):343–353. doi: 10.1177/1524839912454286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. American Journal of Evaluation. 2005;29(3):320–437. [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer MA, Shediac MC, Cassady CE. Measuring the implementation of health promotion programs – The case of the breast and cervical-cancer program in Maryland. Health Education Research. 1995;10(1):11–25. doi: 10.1093/her/10.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL. Community-based physical activity programs for adults age 50 and older. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2001;9(Suppl.):S71–S91. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Mills KM, Sepsis PG, King AC, McLellan BY, Roitz K, et al. Evaluation of CHAMPS, a physical activity promotion program for older adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;19(4):353–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02895154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: Outcomes for interventions. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001;33(7):1126–1141. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Verboncoeur CJ, McLellan BY, Gillis DE, Rush S, Mills KM, et al. Physical activity outcomes of CHAMPS II: A physical activity promotion program for older adults. Journals of Gerontology A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2001;56(8):M465–M470. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.8.m465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE, Subar AF, Smith AF, Midthune D, Radimer KL, Kahle LL, et al. Fruit and vegetable assessment: Performance of 2 new short instruments and a food frequency questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetics Association. 2002;102:1764–1772. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DPR. Mediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavioral Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Dowda M, Leviton LC, Bartlett-Prescott J, Bazzarre T, Campbell-Voytal K, et al. Final results from the translation of two physical activity programs. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2008;35(4):340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Laken M, Parrott AW, Condrasky M, Saunders R, Addy CA, et al. Faith, activity, and nutrition (FAN) program: Design of a participatory research intervention to increase physical activity and improve dietary habits in African American churches. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2010;31:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Parrott A, Baruth M, Laken M, Condrasky M, Saunders R, et al. The faith, activity, and nutrition program: A randomized controlled trial in African-American Churches. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(2):122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeary KHK, Klos LA, Linnan L. The examination of process evaluation use in church-based health interventions: A systematic review. Health Promotion Practice. 2012;13(4):524–534. doi: 10.1177/1524839910390358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvoch K. How does fidelity of implementation matter? Using multilevel models to detect relationships between participant outcomes and delivery and receipt of treatment. American Journal of Evaluation. 2012;33(4):547–565. [Google Scholar]