Abstract

Objective

Accumulating evidence suggests that inflammation plays a role in the pathophysiology of major depression. The adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) plays a crucial role in microglial activation caused by inflammation. The dye brilliant blue G (BBG) is a P2X7R antagonist. This study examined whether BBG shows antidepressant effects in an inflammation-induced model of depression.

Methods

We examined the effects of BBG (12.5, 25, or 50 mg/kg) on serum tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels after administering the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 0.5 mg/kg) and the effects of BBG (50 mg/kg) on depression-like behavior in the tail-suspension test (TST) and forced swimming test (FST).

Results

Pretreatment with BBG (12.5, 25, or 50 mg/kg) significantly blocked the increase in serum TNF-α levels after a single dose of LPS (0.5 mg/kg). Furthermore, BBG (50 mg/kg) significantly attenuated the increase in immobility time in the TST and FST after LPS (0.5 mg/kg) administration.

Conclusion

The results suggest that BBG has anti-inflammatory and antidepressant effects in mice after LPS administration. Therefore, P2X7R antagonists are potential therapeutic drugs for inflammation-related major depression.

Keywords: Coomassie Brilliant Blue, Cytokine, Depression, Inflammation, Purinergic P2X7 receptors, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

INTRODUCTION

Several lines of evidence suggest that inflammation plays a role in the pathophysiology of major depression and that anti-inflammatory drugs have antidepressant-like effects.1,2,3,4) The administration of the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces inflammation and subsequent depression-like behavior in rodents.1,5) Furthermore, the depression-like behavior and altered serum pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), induced by LPS are blocked by antidepressants, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).6) A meta-analysis found higher blood TNF-α levels in drug-free depressive patients compared with healthy controls.7) A postmortem brain study showed elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression in the frontal cortex of people with a history of major depression.8) Therefore, it is likely that both peripheral and central inflammation are associated with depressive symptoms and that anti-inflammatory drugs could ameliorate these symptoms in patients with major depression.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) has been implicated in acute and chronic inflammation.9,10) Among the ATP-sensitive purinergic receptors, the P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) has an important role in the post-translational processing of the biologically active pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β).11) P2X7R is abundantly expressed in microglia12) and to a lesser extent in astrocytes,13) oligodendrocytes,14) and the presynaptic terminals of neurons.15) Studies using P2X7R knock-out (KO) mice showed that the absence of P2X7R leads to reduced immobility time in the tail-suspension test (TST) and forced swimming test (FST),16,17) suggesting a role of P2X7R in depression-like behavior. Therefore, P2X7R antagonists are potential therapeutic drugs for major depression.18,19)

The dye brilliant blue G (BBG), also known as Coomassie blue, is the best-known P2X7R antagonist and has nanomolar potency,20) although it also inhibits voltage-gated sodium currents at higher concentrations.21) This study examined whether BBG shows anti-inflammatory and antidepressant effects in mice after LPS administration.

METHODS

Animals

All experiments used 8-week-old male adult C57BL/6N mice (body weight 20-25 g; Japan SLC, Hamamatsu, Japan). The animals were housed in controlled temperatures under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on from 07:00-19:00), with food and water ad libitum. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for Animal Experimentation of Chiba University. The experimental procedure was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chiba University (permission number: 25-270).

Drug Administration

On the day of injection, fresh solutions were prepared by dissolving compounds in sterile endotoxin-free isotonic saline. LPS (0.5 mg/kg; L-4130, serotype 0111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.). BBG was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The dose of BBG was reported previously.17,22)

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Vehicle (10 ml/kg, i.p.) or BBG (12.5, 25, or 50 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered to mice 30 minutes before LPS injection. Under sodium pentobarbital, blood samples were taken via cardiac puncture 90 minutes after LPS administration. Blood was centrifuged at 2,000 g for 20 minutes to generate serum samples, as reported previously.6) The serum samples were diluted 20-fold with ELISA diluent solution (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). The serum TNF-α concentrations were measured using a Ready-SET-Go ELISA kit (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Behavioral Tests

On day 1, vehicle (10 ml/kg, i.p.) or BBG (50 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered to mice 30 minutes before the i.p. administration of LPS (0.5 mg/kg) or saline (10 ml/kg). On day 2, all behavioral tests were performed in the following order: locomotion at 9:00 h (24 hours after LPS injection), TST at 14:00 h (27 hours after LPS injection), FST at 16:00 h (29 hours after LPS injection). The mice were put in the test room 30 minutes before the behavioral tests. All tests were performed in a quiet room between 9:00 and 17:00 h. After the tests, the mice were returned to their home cages, which were returned to the breeding room.

Locomotion

The mice were placed in 560×560×330-mm cages (length×width×height). The cage was cleaned between testing sessions. The locomotor activity of the mice was counted using a SCANET MV-40 (Melquest, Toyama, Japan), and the cumulative amount of exercise was recorded for 60 minutes.

TST

The mice were taken from their home cage, and a small piece of adhesive tape was placed approximately 2 cm from the tip of the tail. A single hole was punched in the tape and the mice were hung individually on a hook. The immobility time of each mouse was recorded for 10 minute. Mice were considered immobile only when they hung passively and were completely motionless.

FST

The mice were placed individually in a cylinder (diameter 23 cm, height 31 cm) containing 15 cm of water maintained at 23±1℃. The animals were tested in automated forced-swim apparatus using a SCANET MV-40. The immobility time was calculated from the activity time as (total time)-(active time) using software built into the apparatus. The cumulative immobility time was scored for 6 minutes during the test.

Statistical Analysis

The data are shown as the mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). The data were analyzed using PASW Statistics 20 (formerly SPSS statistics; SPSS, Tokyo, Japan). All data, including the locomotion, TST, and FST test results, were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the post hoc Bonferroni/Dunn test. p-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of BBG on Serum TNF-α Levels

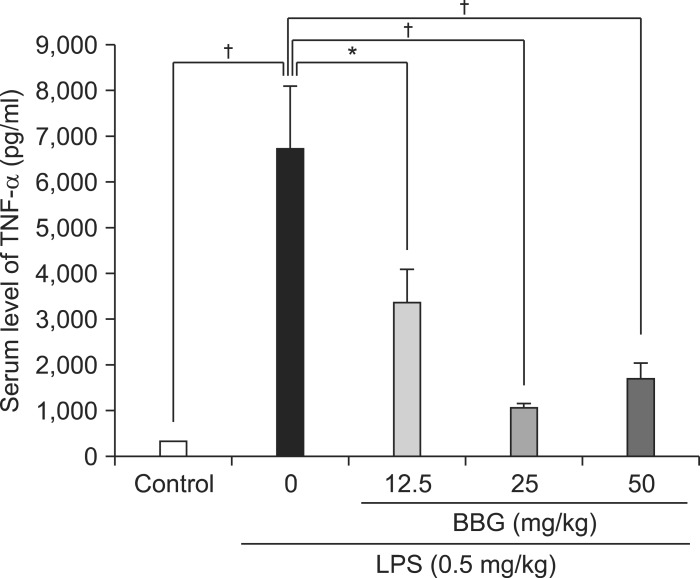

In the vehicle-treated mice, serum TNF-α levels were very low (Fig. 1), consistent with a previous report.6) The serum TNF-α levels were increased significantly after a single dose of LPS (0.5 mg/kg) (Fig. 1). BBG (12.5, 25, or 50 mg/kg) was given 30 minutes before the LPS injection, and blood was collected 90 minutes after the LPS injection. Pretreatment with BBG (12.5, 25, or 50 mg/kg) significantly attenuated the LPS-induced increases in serum TNF-α (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of brilliant blue G (BBG) on the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced increase in serum tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels. Thirty minutes after a single intraperitoneally (i.p.) dose of vehicle (10 ml/kg) or BBG (12.5, 25, or 50 mg/kg), saline (10 ml/kg) or LPS (0.5 mg/kg) was injected i.p. Blood was collected 90 minutes after the LPS (or saline) injection. The serum TNF-α concentration was measured with ELISA. The bars in the figure are shown as the mean±SEM (n=8). *p<0.05, †p<0.001 compared with the LPS-treated group (black column).

Antidepressant Effects of BBG on LPS-induced Depression-like Behavior in Mice

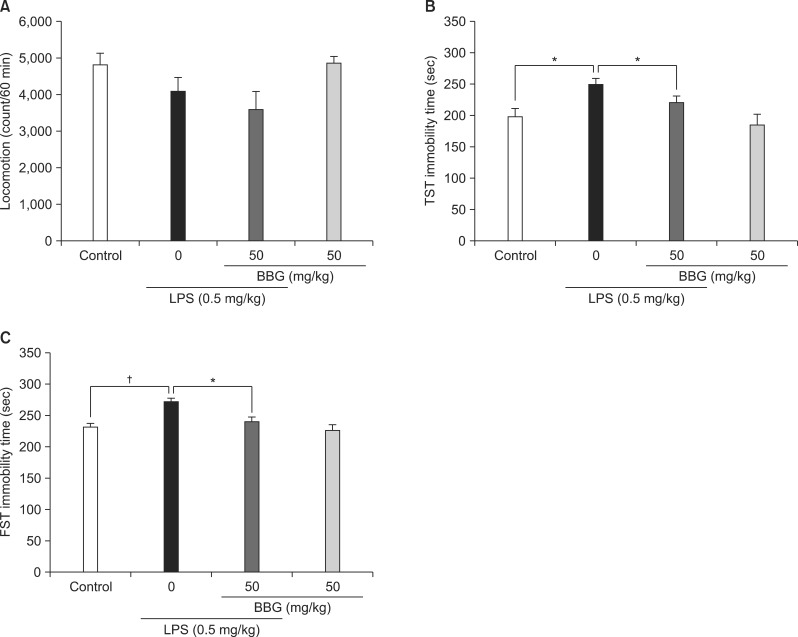

In mice, the FST and TST are the behavioral assays used most widely for detecting potential antidepressant-like activity23,24,25) To examine the antidepressant effects of BBG on LPS-induced depression-like behavior, BBG (50 mg/kg) was given 30 minutes before the LPS injection. Behavioral evaluations were performed 24 hours after the LPS injection.

One-way ANOVA of the locomotion data revealed no significant differences among the four groups (F[3,43]=2.709, p=0.057). Pretreatment with BBG did not affect the spontaneous locomotion in the vehicle- and LPS-treated mice (Fig. 2A). One-way ANOVA on the TST data revealed significant differences among the four groups (F[3, 50]=5.766, p=0.002). The post hoc analysis showed that BBG (50 mg/kg) significantly (p=0.036) attenuated the immobility time compared with the LPS-treated group (Fig. 2B). One-way ANOVA of the FST data revealed significant differences among the four groups (F[3, 50]=6.737, p=0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that BBG (50 mg/kg) significantly (p=0.035) attenuated the immobility time compared with the LPS-treated group (Fig. 2C). However, BBG (50 mg/kg) alone did not affect the immobility time (TST and FST) of control mice (Fig. 2B, 2C).

Fig. 2.

Antidepressant effects of brilliant blue G (BBG) on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced depression-like behavior in mice. BBG (50 mg/kg) or vehicle (10 ml/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 30 minutes before LPS (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) administration. Behavior was evaluated 24 hours after the LPS injection. (A) locomotion, (B) tail-suspension test (TST), (C) forced swimming test (FST). The bars in the figure are the mean±SEM (n=12-14). *p<0.05, †p<0.01 compared with the LPS-treated group (black column).

DISCUSSION

This study found that BBG, a potent P2X7R antagonist, showed anti-inflammatory effects on the serum TNF-α levels after LPS injection and antidepressant effects in the TST and FST. The anti-inflammatory effects are consistent with the effects of antidepressants (SSRIs and SNRIs) on serum TNF-α levels.6) Furthermore, pretreatment with BBG significantly attenuated the increase in immobility time in the TST and FST after LPS injection. Recently, Pereira et al.26) reported that two P2XR antagonists (PPADS and iso-PPADS) decreased the immobility time in the FST and that the antidepressant-like effect of iso-PPADS was associated with a decrease in nitric oxide levels in the prefrontal cortex. Therefore, P2X7R antagonists such as BBG are potential therapy for inflammation-induced depression.

The peripheral administration of LPS induces sickness behavior that peaks 2-6 hours later and wanes gradually.1) This behavior requires the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling in the brain in response to peripheral LPS injection, and the depression-like behavior peaks 24 hours post-LPS injection.1) In this study, we measured the serum TNF-α levels in mice 90 minutes after LPS injection and performed the behavioral evaluations 24 hours after LPS injection. BBG showed an anti-inflammatory effect on the serum TNF-α levels after LPS injection and antidepressant effects on LPS-induced depressive behavior in mice. Interestingly, it was reported that genetic deletion of P2X7R leads to an antidepressant-like phenotype in the TST and FST.17) Additionally, BBG did not show antidepressant-effects in P2X7R KO mice.17) These findings suggest that BBG exerts its antidepressant-effects via P2X7R antagonism. A recent study using P2X7R KO mice suggested that P2X7R is involved in the adaptive mechanisms elicited by exposure to repeated environmental stressors that lead to the development of depression-like behavior.27) A study using bone marrow chimeric mice showed that P2X7R expressed on peripheral immune cells is unlikely to mediate the impact of P2X7R on depression-like behaviors in naïve mice,17) showing that the depression-like behavior in P2X7R KO mice was not transferred to wild-type mice recipients of P2X7R KO bone marrow cells. Therefore, P2X7R may play a role in the pathophysiology of major depression associated with inflammation.

Microglial activation is associated with the pathogenesis of major depression.3,28) Although the precise molecular mechanisms underlying microglial activation are largely unknown, P2X7R plays an important role in microglial activation in the brain.29,30) The LPS-induced release of IL-1β was prevented by the P2X7R antagonist A-438079 and was absent in spinal cord slices taken from P2X7R KO mice.31) Furthermore, the TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA levels in the brain were elevated less in P2X7R KO mice than in wild-type mice in response to systemic LPS administration.32) Interestingly, P2X7R was reported to play a role in the altered cytokine levels after LPS injection, whereas it did not play a role in the basal cytokine levels in the brain.32,33) Therefore, P2X7R appears to play a key role in the brain cytokine response to immune stimuli that might be involved in the pathophysiology of major depression.

Recent linkage studies have found a susceptibility locus for mood disorders such as major depression and bipolar disorder on chromosome 12q24.34,35,36) Among the genes on 12q24, a polymorphism (rs2230912) of the gene encoding P2X7R is associated with both major depression and bipolar disorder,37,38,39,40,41) although some studies have reported negative findings.42,43,44) Furthermore, a polymorphism (rs2230912) had a genetic effect on depressive symptom severity in patients with bipolar disorder.44) Therefore, the P2X7R gene may be involved in the pathogenesis of mood disorders, such as major depression and bipolar disorder.

In conclusion, this study showed that the P2X7R antagonist BBG has anti-inflammatory and antidepressant effects in mice after LPS-induced inflammation. Therefore, P2X7R antagonists are potential therapy for inflammation-related depression.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (to K.H.).

References

- 1.Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:732–741. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto K. Emerging role of glutamate in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Brain Res Rev. 2009;61:105–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raison CL, Lowry CA, Rook GA. Inflammation, sanitation, and consternation: loss of contact with coevolved, tolerogenic microorganisms and the pathophysiology and treatment of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1211–1224. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Connor JC, Lawson MA, André C, Moreau M, Lestage J, Castanon N, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:511–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohgi Y, Futamura T, Kikuchi T, Hashimoto K. Effects of antidepressants on alternations in serum cytokines and depressive-like behavior in mice after lipopolysaccharide administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;103:853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shelton RC, Claiborne J, Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M, Reddy R, Aschner M, Lewis DA, et al. Altered expression of genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis in frontal cortex in major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:751–762. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature04886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khakh BS, North RA. Neuromodulation by extracellular ATP and P2X receptors in the CNS. Neuron. 2012;76:51–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari D, Pizzirani C, Adinolfi E, Lemoli RM, Curti A, Idzko M, et al. The P2X7 receptor: a key player in IL-1 processing and release. J Immunol. 2006;176:3877–3883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrari D, Villalba M, Chiozzi P, Falzoni S, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Di Virgilio F. Mouse microglial cells express a plasma membrane pore gated by extracellular ATP. J Immunol. 1996;156:1531–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballerini P, Rathbone MP, Di Iorio P, Renzetti A, Giuliani P, D'Alimonte I, et al. Rat astroglial P2Z (P2X7) receptors regulate intracellular calcium and purine release. Neuroreport. 1996;7:2533–2537. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611040-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matute C, Torre I, Pérez-Cerdá F, Pérez-Samartín A, Alberdi E, Etxebarria E, et al. P2X(7) receptor blockade prevents ATP excitotoxicity in oligodendrocytes and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9525–9533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0579-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deuchars SA, Atkinson L, Brooke RE, Musa H, Milligan CJ, Batten TF, et al. Neuronal P2X7 receptors are targeted to presynaptic terminals in the central and peripheral nervous systems. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7143–7152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07143.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basso AM, Bratcher NA, Harris RR, Jarvis MF, Decker MW, Rueter LE. Behavioral profile of P2X7 receptor knockout mice in animal models of depression and anxiety: relevance for neuropsychiatric disorders. Behav Brain Res. 2009;198:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Csölle C, Andó RD, Kittel Á, Gölöncsér F, Baranyi M, Soproni K, et al. The absence of P2X7 receptors (P2rx7) on non-haematopoietic cells leads to selective alteration in mood-related behaviour with dysregulated gene expression and stress reactivity in mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:213–233. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skaper SD, Debetto P, Giusti P. The P2X7 purinergic receptor: from physiology to neurological disorders. FASEB J. 2010;24:337–345. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-138883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furuyashiki T. Roles of dopamine and inflammation-related molecules in behavioral alterations caused by repeated stress. J Pharmacol Sci. 2012;120:63–69. doi: 10.1254/jphs.12r09cp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang LH, Mackenzie AB, North RA, Surprenant A. Brilliant blue G selectively blocks ATP-gated rat P2X(7) receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jo S, Bean BP. Inhibition of neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels by brilliant blue G. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:247–257. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.070276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng W, Cotrina ML, Han X, Yu H, Bekar L, Blum L, et al. Systemic administration of an antagonist of the ATP-sensitive receptor P2X7 improves recovery after spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12489–12493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902531106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cryan JF, Holmes A. The ascent of mouse: advances in modelling human depression and anxiety. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:775–790. doi: 10.1038/nrd1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma XC, Jiang D, Jiang WH, Wang F, Jia M, Wu J, et al. Social isolation-induced aggression potentiates anxiety and depressive-like behavior in male mice subjected to unpredictable chronic mild stress. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma XC, Dang YH, Jia M, Ma R, Wang F, Wu J, et al. Long-lasting antidepressant action of ketamine, but not glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor SB216763, in the chronic mild stress model of mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira VS, Casarotto PC, Hiroaki-Sato VA, Sartim AG, Guimarães FS, Joca SR. Antidepressant- and anticompulsive-like effects of purinergic receptor blockade: Involvement of nitric oxide. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.01.008. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boucher AA, Arnold JC, Hunt GE, Spiro A, Spencer J, Brown C, et al. Resilience and reduced c-Fos expression in P2X7 receptor knockout mice exposed to repeated forced swim test. Neuroscience. 2011;189:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beumer W, Gibney SM, Drexhage RC, Pont-Lezica L, Doorduin J, Klein HC, et al. The immune theory of psychiatric diseases: a key role for activated microglia and circulating monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:959–975. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0212100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi HB, Ryu JK, Kim SU, McLarnon JG. Modulation of the purinergic P2X7 receptor attenuates lipopolysaccharide-mediated microglial activation and neuronal damage in inflamed brain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4957–4968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5417-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monif M, Burnstock G, Williams DA. Microglia: proliferation and activation driven by the P2X7 receptor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1753–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark AK, Staniland AA, Marchand F, Kaan TK, McMahon SB, Malcangio M. P2X7-dependent release of interleukin-1beta and nociception in the spinal cord following lipopolysaccharide. J Neurosci. 2010;30:573–582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3295-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mingam R, De Smedt V, Amédée T, Bluthé RM, Kelley KW, Dantzer R, et al. In vitro and in vivo evidence for a role of the P2X7 receptor in the release of IL-1 beta in the murine brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csölle C, Sperlágh B. Peripheral origin of IL-1beta production in the rodent hippocampus under in vivo systemic bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge and its regulation by P2X(7) receptors. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;219:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serretti A, Mandelli L. The genetics of bipolar disorder: genome 'hot regions,' genes, new potential candidates and future directions. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:742–771. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGuffin P, Knight J, Breen G, Brewster S, Boyd PR, Craddock N, et al. Whole genome linkage scan of recurrent depressive disorder from the depression network study. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3337–3345. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kremeyer B, García J, Müller H, Burley MW, Herzberg I, Parra MV, et al. Genome-wide linkage scan of bipolar disorder in a Colombian population isolate replicates Loci on chromosomes 7p21-22, 1p31, 16p12 and 21q21-22 and identifies a novel locus on chromosome 12q. Hum Hered. 2010;70:255–268. doi: 10.1159/000320914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucae S, Salyakina D, Barden N, Harvey M, Gagné B, Labbé M, et al. P2RX7, a gene coding for a purinergic ligand-gated ion channel, is associated with major depressive disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2438–2445. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barden N, Harvey M, Gagné B, Shink E, Tremblay M, Raymond C, et al. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes in the chromosome 12Q24.31 region points to P2RX7 as a susceptibility gene to bipolar affective disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:374–382. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green EK, Grozeva D, Raybould R, Elvidge G, Macgregor S, Craig I, et al. P2RX7: A bipolar and unipolar disorder candidate susceptibility gene? Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:1063–1069. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hejjas K, Szekely A, Domotor E, Halmai Z, Balogh G, Schilling B, et al. Association between depression and the Gln460Arg polymorphism of P2RX7 gene: a dimensional approach. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:295–299. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McQuillin A, Bass NJ, Choudhury K, Puri V, Kosmin M, Lawrence J, et al. Case-control studies show that a non-conservative amino-acid change from a glutamine to arginine in the P2RX7 purinergic receptor protein is associated with both bipolar- and unipolar-affective disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:614–620. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grigoroiu-Serbanescu M, Herms S, Mühleisen TW, Georgi A, Diaconu CC, Strohmaier J, et al. Variation in P2RX7 candidate gene (rs2230912) is not associated with bipolar I disorder and unipolar major depression in four European samples. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:1017–1021. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lavebratt C, Aberg E, Sjöholm LK, Forsell Y. Variations in FKBP5 and BDNF genes are suggestively associated with depression in a Swedish population-based cohort. J Affect Disord. 2010;125:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halmai Z, Dome P, Vereczkei A, Abdul-Rahman O, Szekely A, Gonda X, et al. Associations between depression severity and purinergic receptor P2RX7 gene polymorphisms. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]